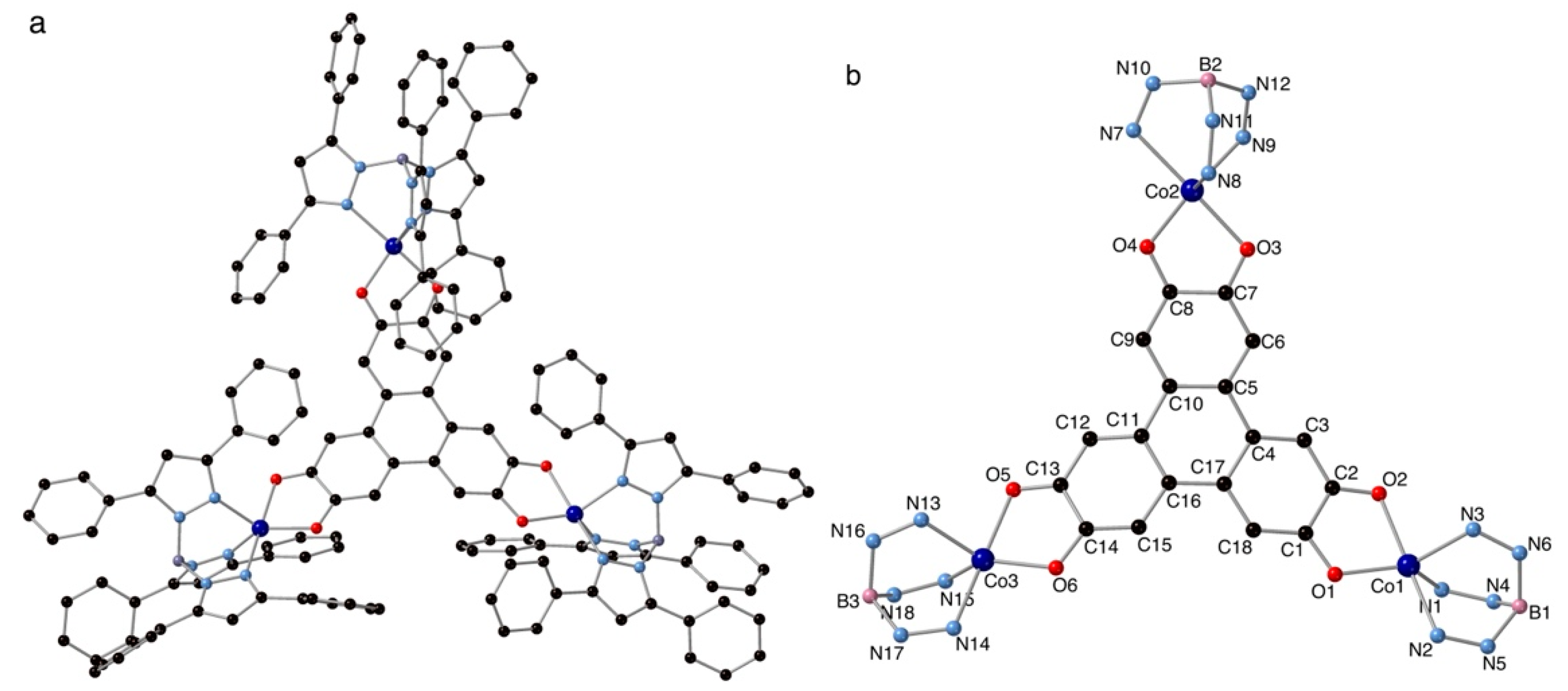

3.1. Crystal Structure

The crystal data collection and refinement parameters for

1 are given in

Table S1.

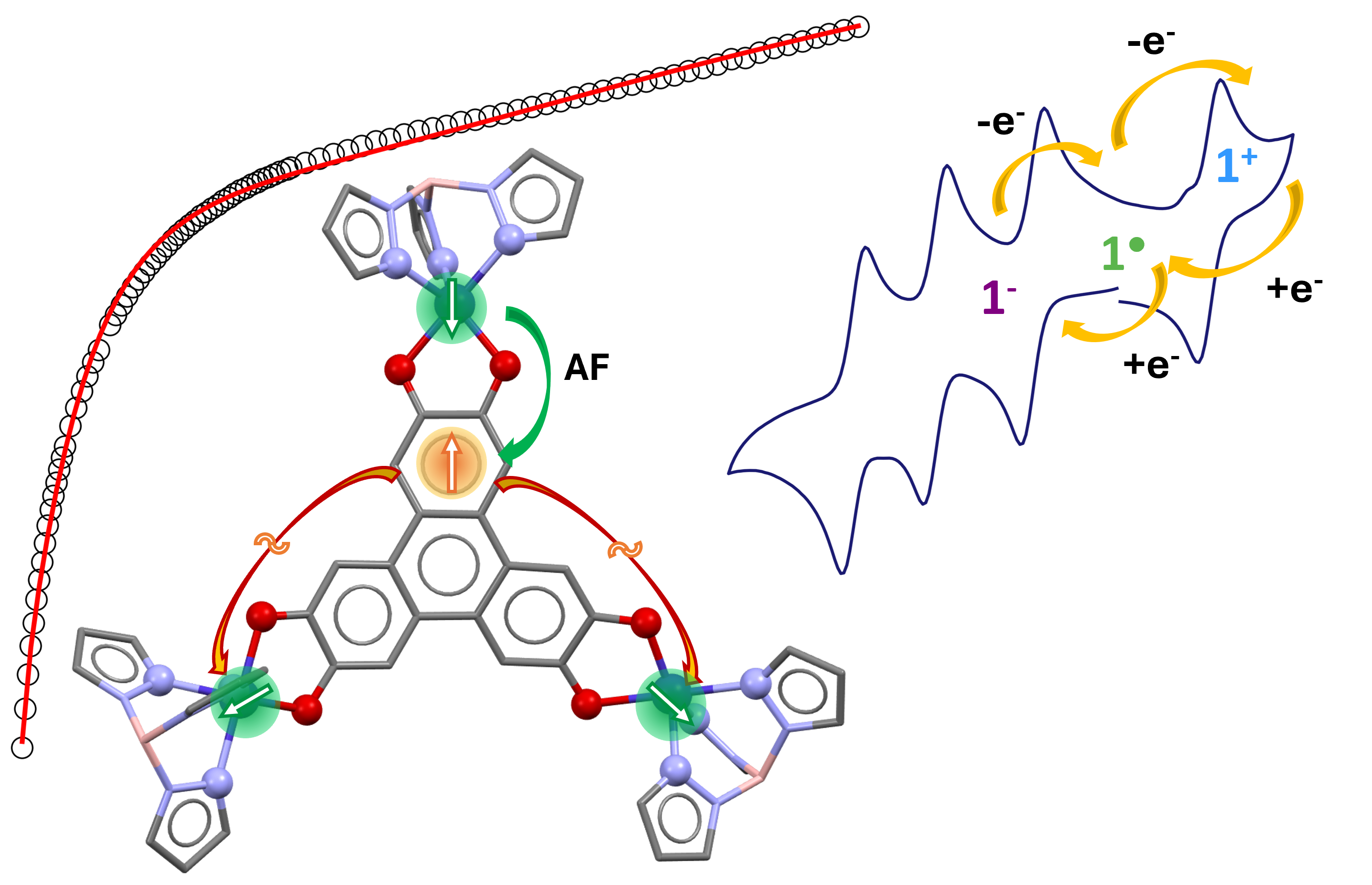

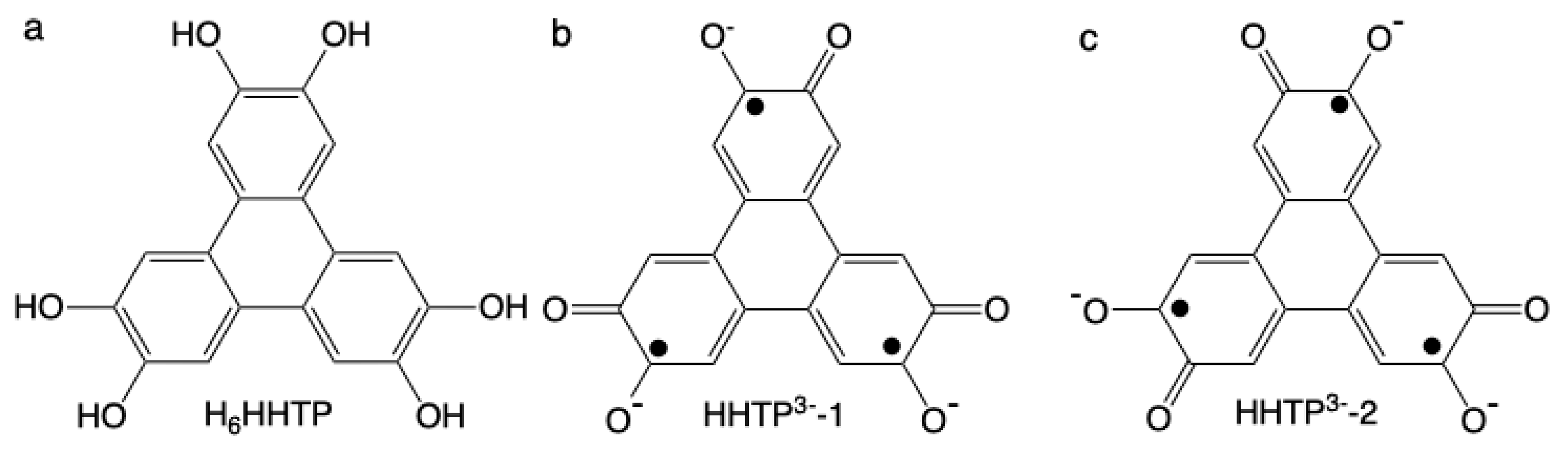

1 is a trinuclear complex made from the assembly of a central HHTP ligand bridging three [Co(BH(Tp

Ph,Ph)

3)] complexes through the three dioxolene groups (

Figure 2,

Figure S1).

The Co atoms are pentacoordinate with a geometry close to trigonal bipyramidal (tbp; Addison parameter[

15] τ close to 0.65). The pseudo three-fold symmetry axes of the three Co(II) complexes lie within the plane of the molecule and correspond to the N2-O2, N7-O3 and N14-O5 directions for Co1, Co2 and Co3, respectively. The bond distances in the coordination sphere of the Co atoms are shorter in the tbp plane than along the pseudo three-fold axes (

Table 1). The difference in the C-O bond lengths for the OCCO dioxolene moieties (

Table 2) indicates that the unpaired sq electrons close to Co1 and Co3 are located on C1 and C14 (Figure2b). For the OCCO moiety close to Co2, the difference in the C-O bond lengths is much smaller indicating a relative delocalization of the sq unpaired electron over the OCCO moiety. The Co-O bond lengths are correlated with the C-O distances. The short Co-O bond distances are those with the oxygen atoms that have the longer C-O bonds (i.e. O1, O4 and O6 for Co1, Co2 and Co3, respectively), those that are formally negatively charged.

These structural characteristics are consistent with the electronic structure of the central HHTP ligand depicted in

Figure 1b, where the sq unpaired electrons of the OCCO moieties close to Co1 and Co3 are separated by 5 C-C bonds. The interaction between the three s = ½ spins of the three sq unpaired electrons leads to two doublet and one quadruplet states. The electronic structure that emerges from the crystallographic analysis should, therefore, lead to a ground doublet spin state (

s = ½) well separated in energy from the other doublet and the quadruplet states, because of a large antiferromagnetic exchange coupling between the two sq electrons separated by 5 C-C bonds. Theoretical calculations were, thus, carried out in order to confirm the electronic structure that emerges from the crystallographic structural analysis and to evaluate the exchange coupling between the central spin and those of the Co(II) metal ions.

3.2. Theoretical Calculations

Ab initio wave function-based calculations were first carried out on a model complex labelled Zn

3HHTP where Co(II) were replaced by diamagnetic Zn(II) in order to examine the electronic structure of the HHTP bridging ligand. The orbitals were optimized at the Complete Active Space Self Consistent Field CAS(3,3)SCF level with an active space containing 3 electrons in 3 HHTP orbitals. Then calculations on a CAS(12,12) active space (12 electrons, 3 from the HHTP and 9 from the three Co(II) in 12 orbitals) were performed on the whole complex. Finally, we carried out calculations on one-electron oxidized model complexes Zn

2Co1, Zn

2Co2 and Zn

2Co3 with the CAS(7,5) active space involving the 7 valence electrons of each Co(II) in their 5 3d orbitals in order to determine the axial (

D) and rhombic (

E) zero-field splitting (ZFS) parameters of the three Co fragments corresponding to the spin Hamiltonian:

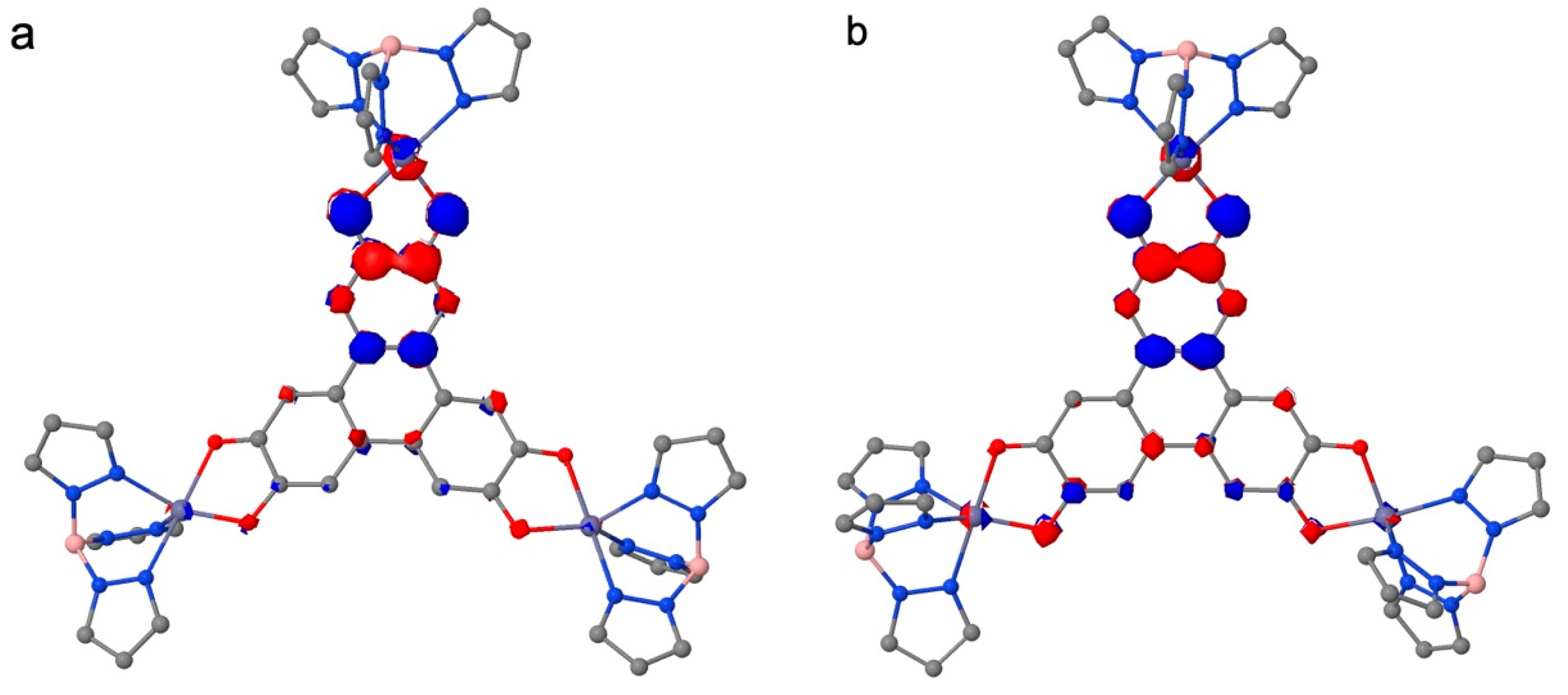

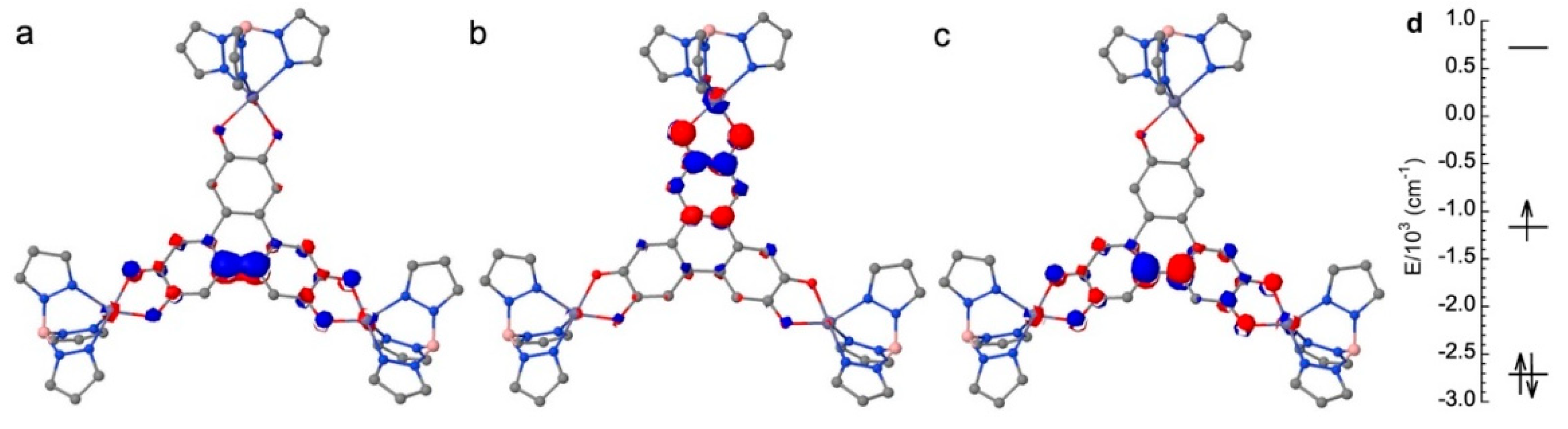

The molecular orbitals of the model complex Zn

3HHTP optimized for the doublet ground state at the CAS(3,3)SCF level show one bonding (HOMO), one non-bonding (SOMO) and one antibonding (LUMO) orbitals depicted in

Figure 3. The SOMO (

Figure 3b) is mainly localized on the OCCO moiety close to Co2 and has almost no contribution on the two other OCCO groups.

The low energy spectrum was calculated using state average CAS(3/3)SCF+NEVPT2 calculations for the 2 lowest s = ½ and the lowest s = 3/2 spin states. It shows a doublet ground state (s = ½), an excited doublet (s = ½) at 5144 cm-1 and a quadruplet (s = 3/2) at 5468 cm-1. Enlarging the active space does not change qualitatively the spectrum: the energy of excited s = ½ and the s = 3/2 states with respect to the ground state are 4705 cm-1 and 6566 cm-1, respectively, for CAS(7,7)SCF+NEVPT2 calculations. The central ligand can thus be described as having one unpaired electron (= ½) expected to interact mainly with the unpaired electrons of Co2.

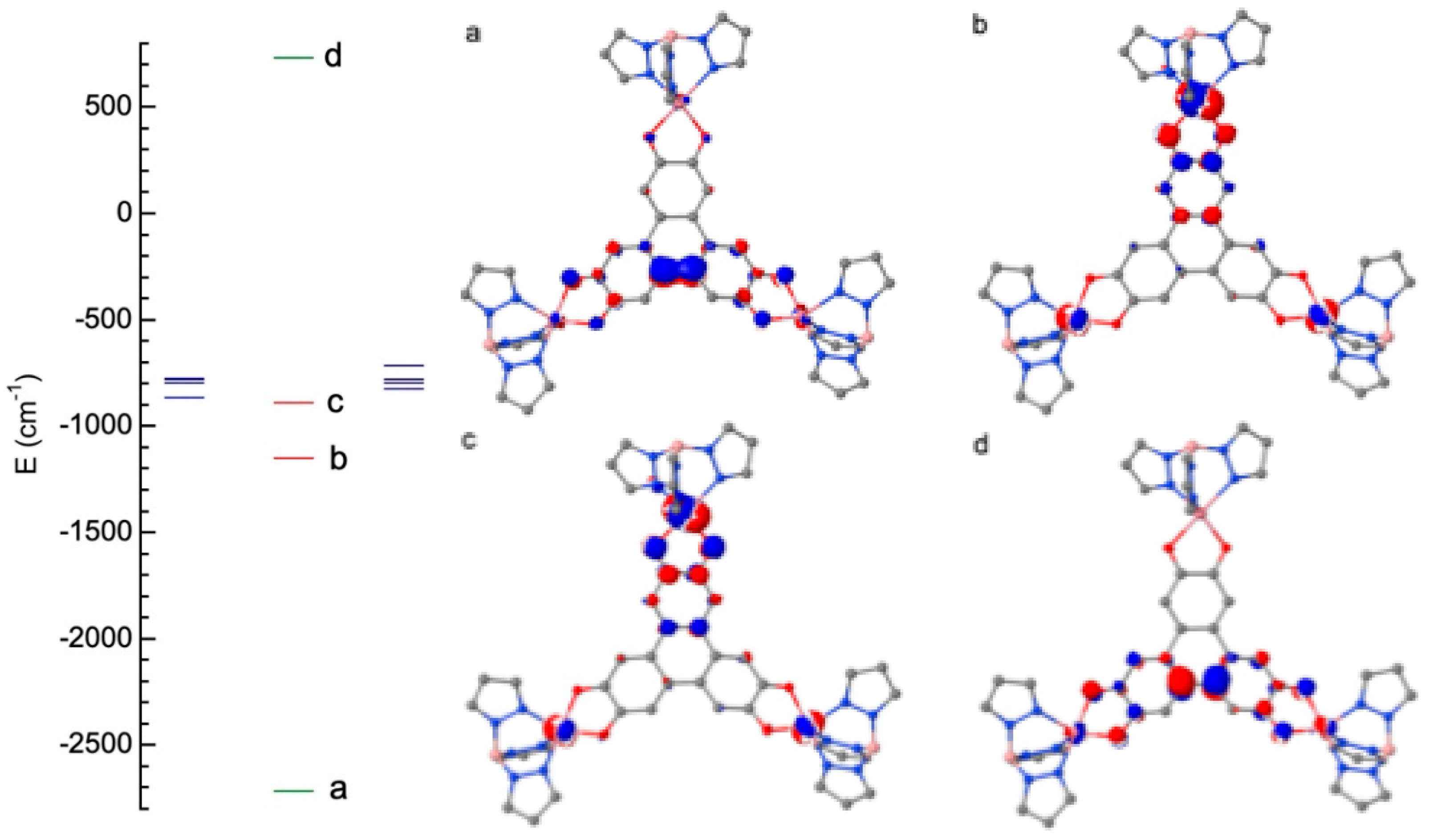

We then studied Co

3HHTP using a state average CAS(12,12)SCF calculation for all states generated by the interaction of three s=3/2 on the Co

2+ ions and one

=1/2 on the bridging ligand (

i.e. one S=5, three S=4, five S=3, seven S=2, six S=1 and two S=0 states). The obtained molecular orbital energy diagram for Co

3HHTP (

Figure 4) shows three sets of orbitals: one set where the orbitals are localized only on Co(II) with no contribution on HHTP (

Figure 4, blue lines and

Figure S2 for orbitals representation); one set with one bonding and one antibonding MOs localized on HHTP (

Figure 4, green lines) that are almost the same as those computed for Zn

3HHTP (

Figure 3a and

Figure 3c); and one set with a bonding and an antibonding MOs involving the SOMO of HHTP and one d orbital of Co2 (

Figure 4, red lines). This orbital energy diagram indicates that the electronic structure of Co

3HHTP is mainly governed by the interaction between the SOMO of HHTP and one d orbital of one of the three Co(II) metal ions, namely Co2. We, therefore, expect that the magnetic behavior of the trinuclear complex will be mainly governed by the exchange coupling between the spins of these two moieties, and by the local anisotropy of Co(II) ions that also needs to be evaluated.

The corresponding model Hamiltonian involves the exchange coupling parameters

between the ligand doublet spin momentum

and

the one of Co2 and the local anisotropies of the three Co(II) ions:

CAS(12,12)SCF+NEVPT2 energy spectrum (

Table S2) confirms a strong antiferromagnetic coupling

between the ligand and Co2 spins of the order of 65cm

-1 (see SI). It results in an effective local metal-ligand ground triplet state (

) and an excited quintet state (

). Indeed, the analysis of the spectrum shows a low energy first set of 10 quasi-degenerate states (spectrum width ~7cm

-1) corresponding to small couplings (few cm

-1) between

and

and

and a second set (14 states) higher in energy (

=130cm

-1, bandwidth ~20cm

-1) corresponding as well to small couplings (few cm

-1) between

and

and

.

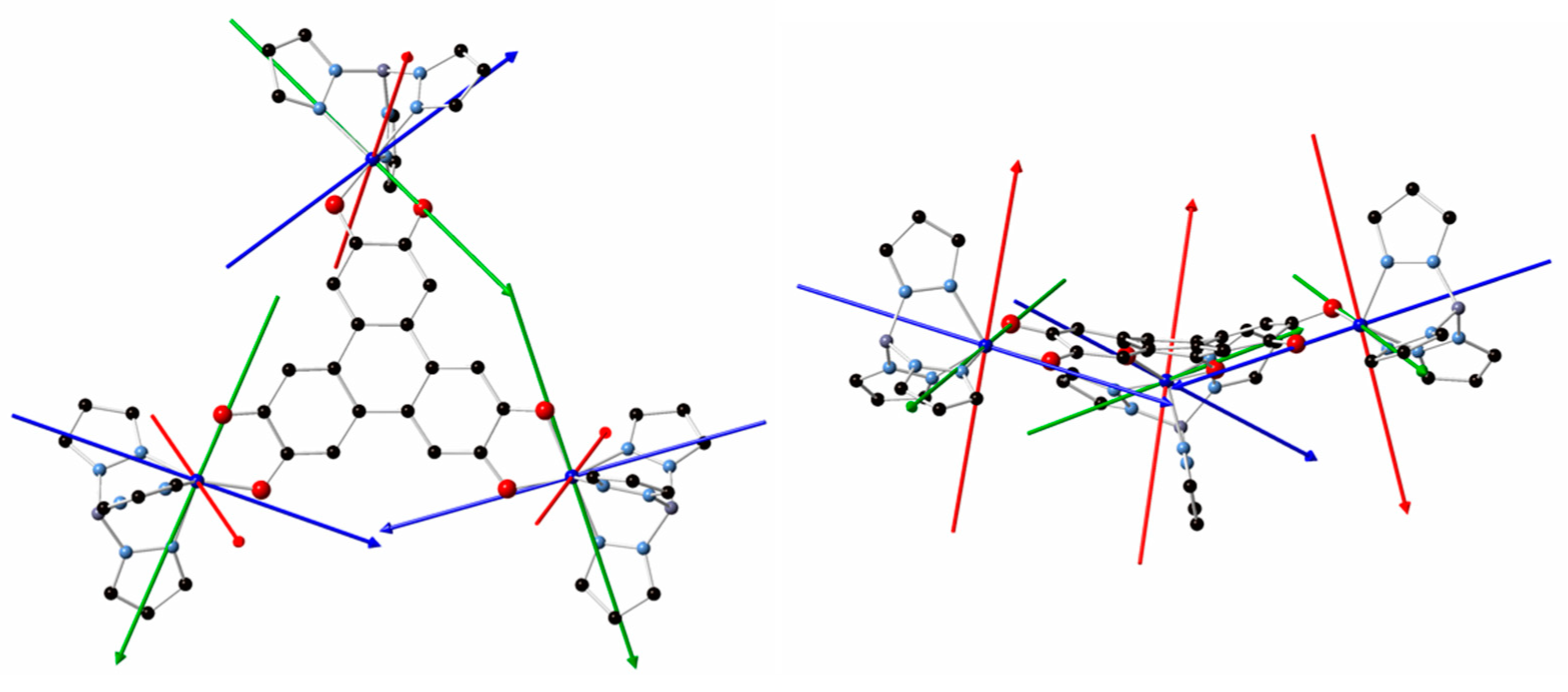

The ZFS parameters (

Table 3) were extracted using an already reported method.[

16] We find relatively large negative

D values for the three Co(II) metal ions with a large rhombicity (we recall that the maximum rhombicity corresponds to

E/|D| = 0.33). As ZFS values are particularly large, we have checked that the first-order SOC contributions were negligible. The easy axis of magnetization for the three Co(II) (

Figure 5) is aligned along the Co-O short bonds and not along the pseudo three-fold axis of the tbp. In order to analyze the origin of the negative

D values, we focus on one Co(II) species (Co2), as the interpretation of the results are the same for the three metal ions (see

Table S3 and

Table S4 for the composition of the wave function of the ground and excited

s = 3/2 states obtained from calculations on Zn

2Co1 and Zn

2Co2 complexes). The calculation also provides the contribution at the second order of perturbation of each excited state to the overall

D value. The first excited state is mainly responsible of the large negative

D values for the Co(II) species (

Table S3 and

Table S4). If we consider the Co2 fragment, the contribution of the first excited state is found equal to -53 cm

-1 (

Table S3) and corresponds to an excitation between

and

orbitals that are linear combinations of the

l = 2,

ml = ±2 spherical harmonics and therefore it is the

part of the spin-orbit operator that couples this state to the ground state. When SO couples through

states of the same spin, it stabilizes the largest |

ms| values (±3/2) of the ground state and therefore contributes negatively to

D.[

17,

18] The third excited state is obtained by an excitation between the

and

orbitals (linear combinations of

ml = ±1) and has, for the same reasons, a negative contribution to

D but weaker in magnitude (-15.6 cm

-1 instead of -53.1 cm

-1) because of the weaker |

ml| values and to the larger energy separation with the ground state (5451 cm

-1 instead of 1138 cm

-1). The second and the fourth excited states have positive contributions (

Table S3), but of much weaker magnitude so that the overall

D value remains negative and large. For Co1, the same analysis justifies its negative

D value (

Table S4).

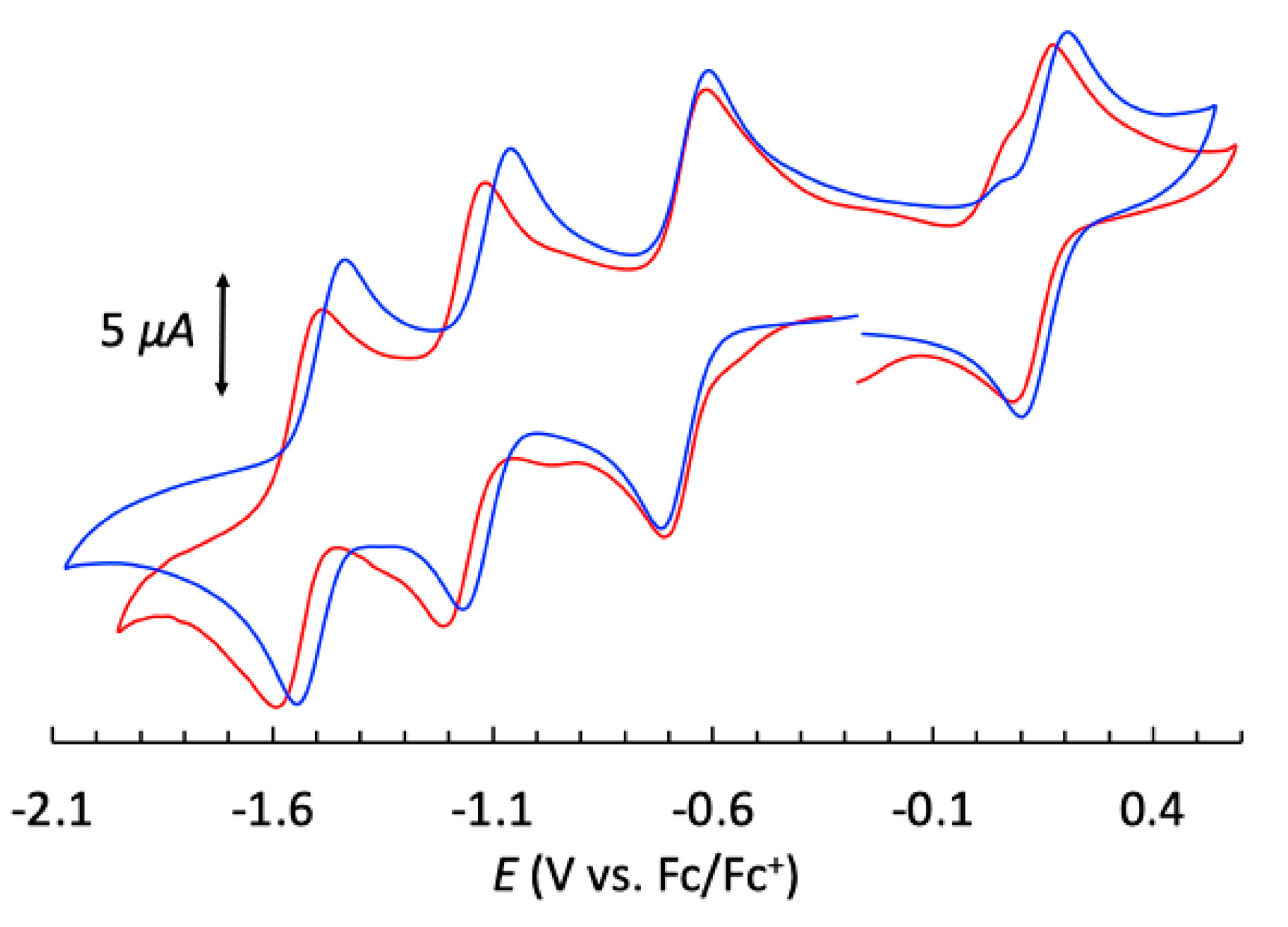

3.3. Redox and Optical Properties

In order to investigate the redox and optical behavior of

1, we performed cyclovoltammetry (CV) and spectro-electrochemistry studies to evaluate the stability of the different species. Those data were compared with the previously reported Ni(II) containing compound that possesses a similar structure with the same capping ligand (noted Ni

3HHTP in the following) and where HHTP is also in the [sq-sq-sq] state.[

4] The CV of

1 shows four reversible redox waves similar to those observed for the Ni(II) complex; three one-electron reduction waves and one one-electron oxidation wave (

Figure 6,

Table S5). The first reduction wave has the same redox potential as that of Ni

3HHTP, while the other waves are slightly shifted anodically, indicating a higher energy requirement for the oxidation process and a more energetically accessible second and third reduction processes for

1 compared to Ni

3HHTP. In the latter, the redox processes are mainly located on HHTP because Ni(II) is redox-inactive in the observed potential window. The very close redox potential values for

1 indicates that the redox processes are also not metal-centered in

1 as for Ni

3HHTP and that they, therefore, mainly involve the bridging ligand HHTP.

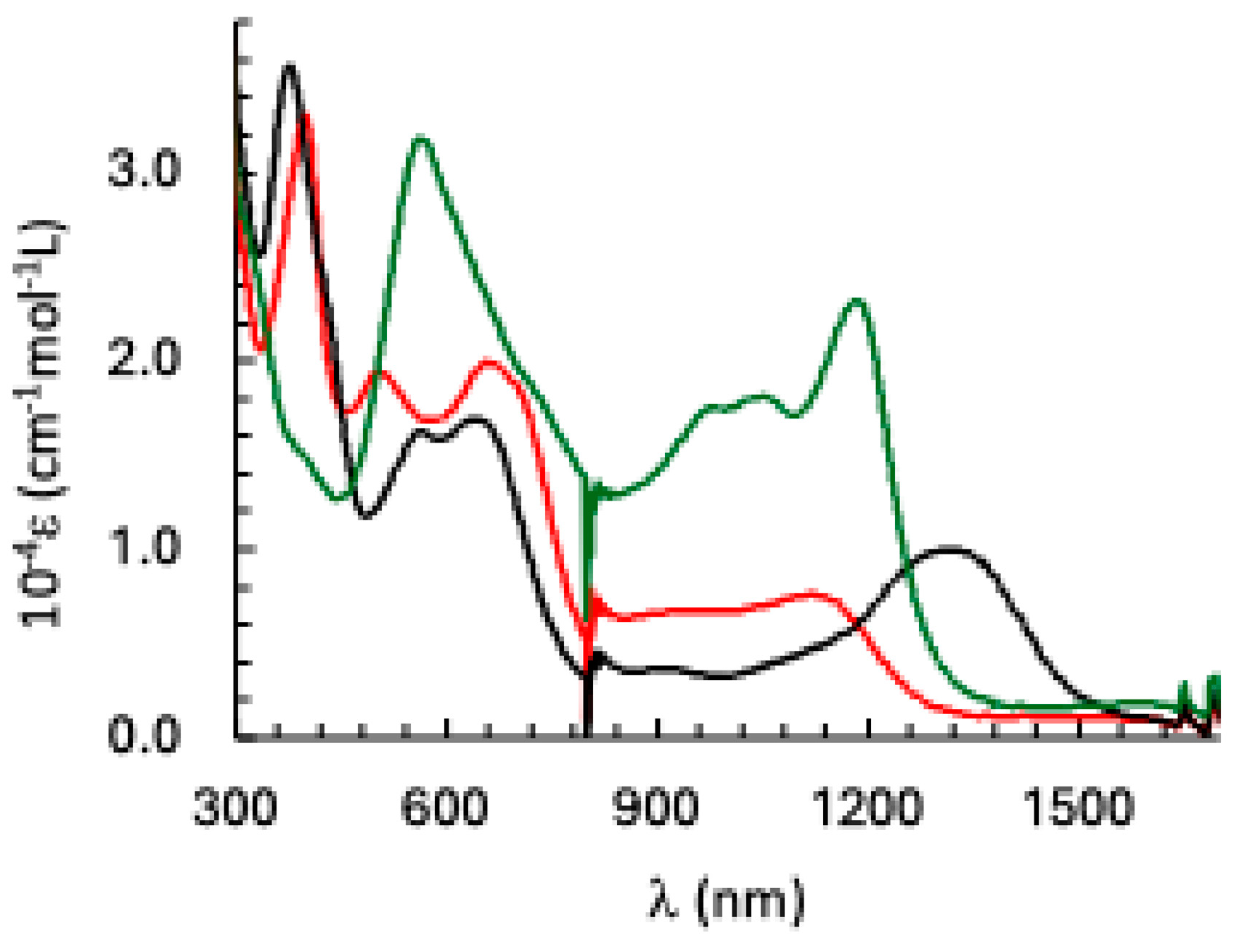

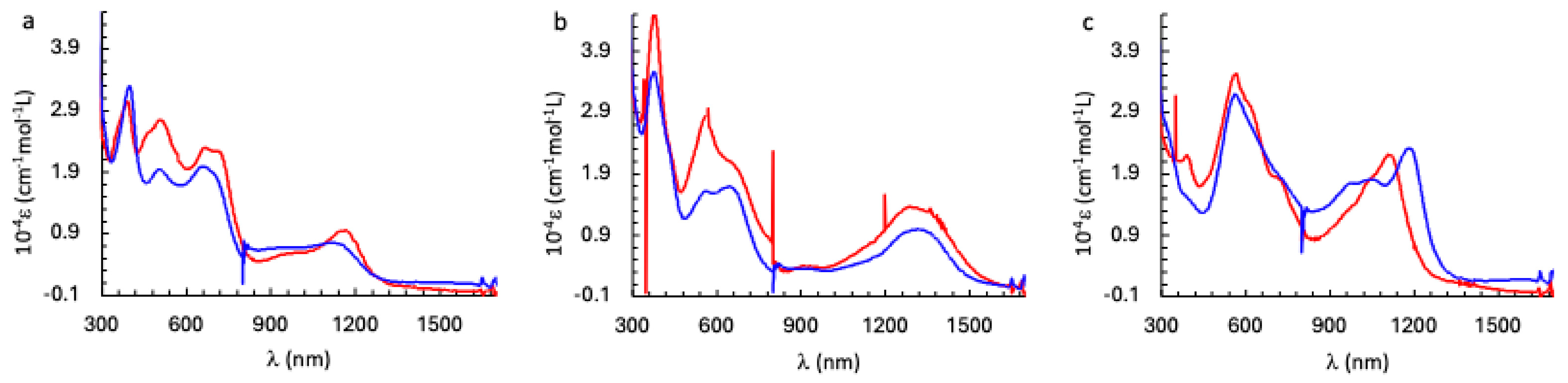

The electronic spectra of

1 as well as its one-electron reduced and one-electron oxidized analogues were recorded using UV-Vis-NIR spectro-electrochemistry. The three species show two sets of absorption bands: in the near infra-red (NIR) and in the visible region (

Figure 7). We focus in the following on the NIR region.

1 displays an absorption band at 1140 nm that is red-shifted to 1315 nm (this band is probably due to two transitions at 1292 and 1370 nm) upon a one-electron reduction and blue-shifted to 1183 nm for the one-electron oxidized species. In order to propose a qualitative assignment for these bands, we compared the electronic spectra to those of Ni

3HHTP (

Figure 8).

The absorption bands in the NIR region of

1 and Ni

3HHTP (

Figure 8a) are almost identical leading to the conclusion that the nature of the metal ions has almost no effect on the electronic transitions and that, therefore, these bands are due to transition(s) within the HHTP when it is in the [sq-sq-sq] state. In fact, within this hypothesis one can expect three absorption bands for the [sq-sq-sq] HHTP based on the MOs energy diagram of Zn

3HHTP (

Figure 3d), corresponding to the promotion of an electron between the three couple of MOs: HOMO

SOMO, SOMO

LUMO and HOMO

LUMO. The first two transitions are expected at lower energy than the latter.

Figure 8a displays two absorption bands at 1139 and 952 nm that may be due to the transition expected at higher energy.

The spectra of the one-electron reduced species (

Figure 8b) are also very similar in the NIR region, confirming that these transitions are mainly centered on the bridging ligand that is in the [sq-sq-cat] state and that the nature of the metal ions does not have a significant effect on the electronic structure of the bridging ligand. The situation is different for the one-electron oxidized species (

Figure 8c), where a blue-shift of 60 nm (468 cm

-1) is observed for the most intense band when going from the Co to the Ni-containing complexes. The analysis performed here is only qualitative. A better understanding of the impact of the metal ions on the optical properties of the trinuclear species and their redox behavior requires an assignment of the different absorption bands that can be eventually done with the help of time-dependent Density Functional calculations that are underway.

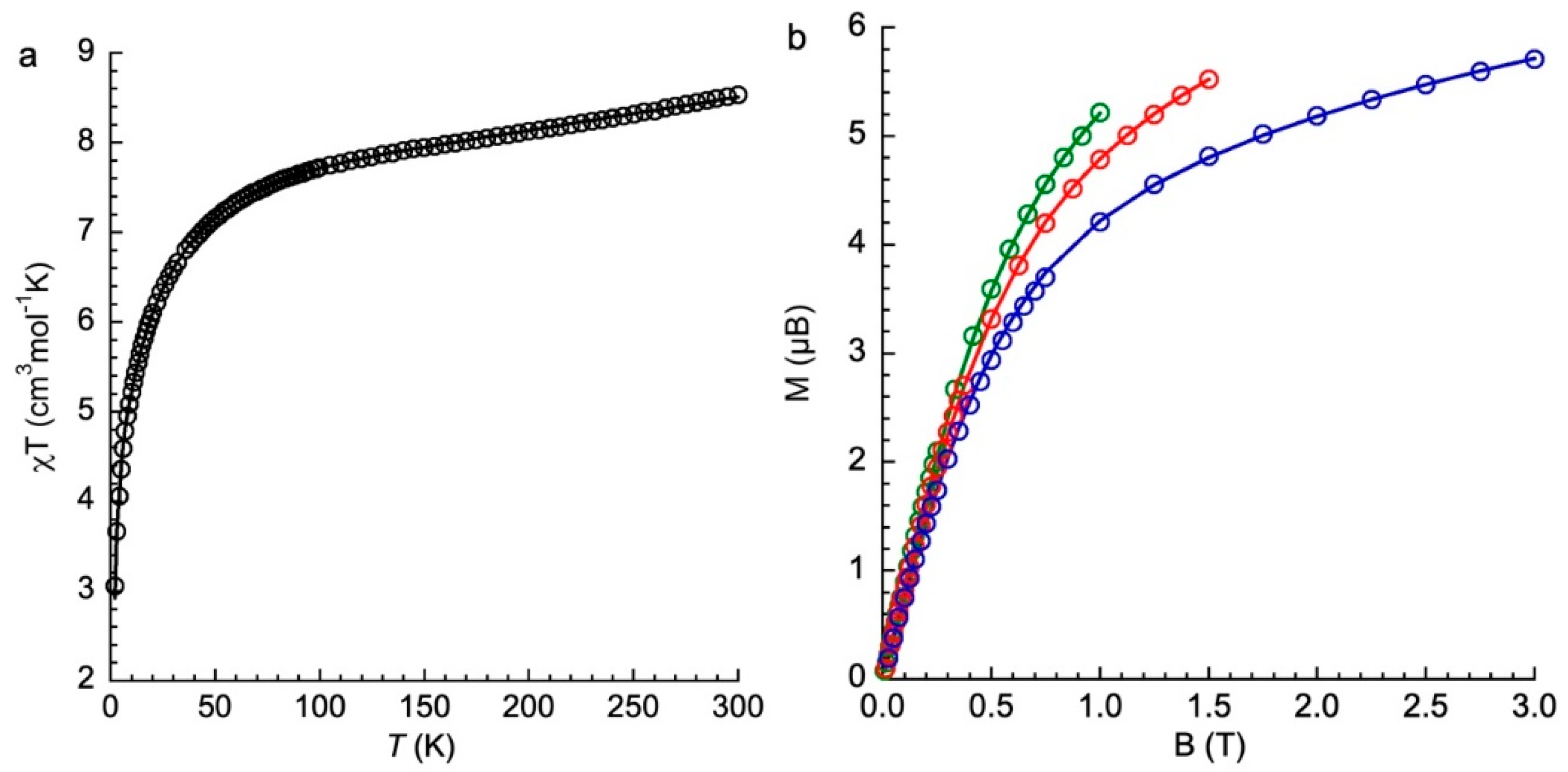

3.4. Magnetic Properties

The magnetic properties of

1 were investigated by measuring the thermal dependence of the χT product (

Figure 9a) and the magnetization vs. the magnetic field at T = 2, 4, 6 K (

Figure 9b). The value of the χT product at T = 300 K (8.51 cm

3mol

-1K) may correspond to one

s = ½ with

g = 2 and three

s = 3/2 with

g = 2.4 non interacting species. Such

g value for Co(II) is not unreasonable. Upon cooling, χT decreases monotonically until a value of 7.5 cm

3mol

-1K at T = 75 K and then more abruptly. It reaches a value of 3 cm

3mol

-1K at 2 K. The relatively large χT value at low temperature indicates a magnetic ground state and the decrease an antiferromagnetic coupling with certainly magnetic anisotropy as indicated from theoretical calculations. The M= f(B/T) curves are not superimposable, which confirms the presence of magnetic anisotropy within the complex.

The data were fitted using PHI,[

19] assuming a model with a central

s = ½ and three peripheral

s = 3/2 spins introducing TIP in the fit procedure. The number of parameters is large (3

g values, 6 ZFS parameters and three exchange coupling parameters). We therefore proceeded in several steps in order to delimit the values of the different parameters and relied on theoretical calculation by considering one large antiferromagnetic exchange coupling and two very weak, on one hand, and on the other hand, we assumed first the same or very close ZFS parameters for the three Co(II) ions. Considering this last assumption, it was not possible to reach a satisfactory solution. We, therefore, used different ZFS parameters but still negative ones because distorted pentacoordinate Co(II) complexes were found to have negative

D in many cases.[

17,

20,

21,

22] The best fit parameters are given in

Table 4.

Overall, the parameters that best fit the magnetic data are qualitatively in agreement with those extracted from calculations, even though the figures may differ when we examine those corresponding to each Co(II) species. There is a large antiferromagnetic exchange coupling between the unpaired electron of HHTP and one of the Co(II) species and two weak couplings with the two other Co(II), as calculations predict. The axial ZFS D values are all negative, but we find weaker values (in absolute value) for two Co(II), while for the third Co(II) the D value is almost the same as that extracted from calculations. The rhombic ZFS parameters E found from the fit are weaker than those evaluated from calculations.