1. Introduction

Amidst the ongoing global climate change, protected horticulture is essential to ensure food security and promote sustainable agriculture. While long-term climate change affects the cultivated land area and cropping systems, short-term abiotic stresses faced by horticultural crops during their fruiting period frequently result in seasonal yield reductions or total crop failure, a leading cause of global horticultural crop loss.[

1,

2].

Cucumber (

Cucumis sativus L.) is one of the most widely cultivated and economically significant vegetables worldwide[

3]. High temperatures harm cucumber production in greenhouses, where optimal photosynthesis occurs between 25-33 °C[

4]. Open field temperatures can exceed 38 °C during summer, while greenhouse temperatures can exceed 45 °C. Prolonged heat stress adversely affects cucumber transpiration, respiration, and photosynthesis, reducing growth and yield and negatively impacting the content of organic acids, vitamin C, soluble protein, and soluble sugars in cucumber fruits[

5]. Additionally, the enclosed structure of greenhouses restricts internal and external gas exchange. Although atmospheric CO

2 levels increase annually, they remain at 380 μmol/mol, only 30% of the optimal level for plant photosynthesis[

6]. This CO

2 deficiency directly impedes photosynthesis and the accumulation of nutrients in leaves. According to the model proposed by Schapendonk et al.[

7], greenhouse CO

2 deficiency could decrease cucumber net assimilation by 15% and long-term yields by 11%. Our previous studies have demonstrated that under high temperature conditions (45 °C), increasing CO

2 levels can significantly enhance the net photosynthetic rate of cucumber during the photosynthetic 'noon break' period, expand the suitable temperature range for photosynthesis, promote leaf growth, delay plant senescence, and increase biomass production, as well as the sugar and organic acid content in cucumber fruits[

8]. Furthermore, elevated CO

2 levels help regulate the expression of differential proteins associated with various biological processes[

9]. While considerable knowledge exists about the role of elevated CO

2 in alleviating the detrimental effects of high-temperature stress on plants, there is an urgent need for research to elucidate the impact of elevated CO

2 in conjunction with high-temperature stress on horticultural plant metabolites. This understanding is critical in light of the pressing challenges of climate change and food security.

Recently, metabolomics technology has been extensively used to analyze metabolic networks associated with plant growth, development, and responses to abiotic stress[

10]. Increased soluble sugars and amino acid concentrations are recognized as generalized heat response mechanisms in various plant species. The accumulation of primary metabolites, such as carbohydrates, enhances the stability of proteins and the bilayer structure of the cell membrane[

11]. Elevated levels of pipecolic acid, oleic acid, and raffinose may signify that these metabolites serve as first-line defense mechanisms for cucumbers against heat stress[

12,

13]. The ascorbic acid (ASA) accumulation in tomato fruits has improved fruit quality and alleviated abiotic stress[

14]. Ecometabolomic studies indicate that the metabolites that increase most significantly in plants under elevated atmospheric CO

2 levels are terpenes and soluble sugars, particularly the monosaccharides galactose, glucose, and fructose. This suggests that increases in newly photosynthesized carbon trigger the immediate accumulation of photosynthetic products[

15]. Furthermore, elevated CO

2 levels facilitate the accumulation of carbohydrates, 1,2,3-trihydroxy benzene, pyrocatechol, glutamate, and L-gluconolactone, enabling cucumber seedlings to adapt to severe drought conditions[

16].

The commercial value of cucumbers is closely linked to the quality of the fruit, which is directly influenced by the growth environment. Currently, most studies utilizing artificial climate chambers, pot experiments, and controlled indoor environments have focused on the individual effects of carbon dioxide and elevated temperatures on various crops' phenology, physiology, and biochemistry [

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, there have been no prior reports on metabolomics investigations of cucumber fruit subjected to elevated CO

2 and high-temperature stress. This study aimed to elucidate the response mechanisms of cucumber fruit metabolomics under elevated CO

2 and high-temperature stress and explore the potential benefits of elevated CO

2 in mitigating the adverse effects of high temperatures. This study included physiological analysis, assessing factors such as fruit size, number of fruits per plant, weight of individual fruits, yield per plant, total number of fruits, total weight of fruits, ascorbic acid content, nitrite content, soluble sugar content, and starch content, alongside metabolomics analysis utilizing ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-TOF MS). Special attention was given to the changes in differential metabolites and metabolic pathways under varying treatment conditions and how these alterations impact the quality of cucumber fruits. The findings of this research contribute valuable insights into the environmental adaptability of protected horticultural crops and the application of carbon dioxide fertilization technology, providing a theoretical foundation for utilizing exogenous metabolites to enhance the heat resistance of cucumbers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, Growth Conditions, and Experimental Design

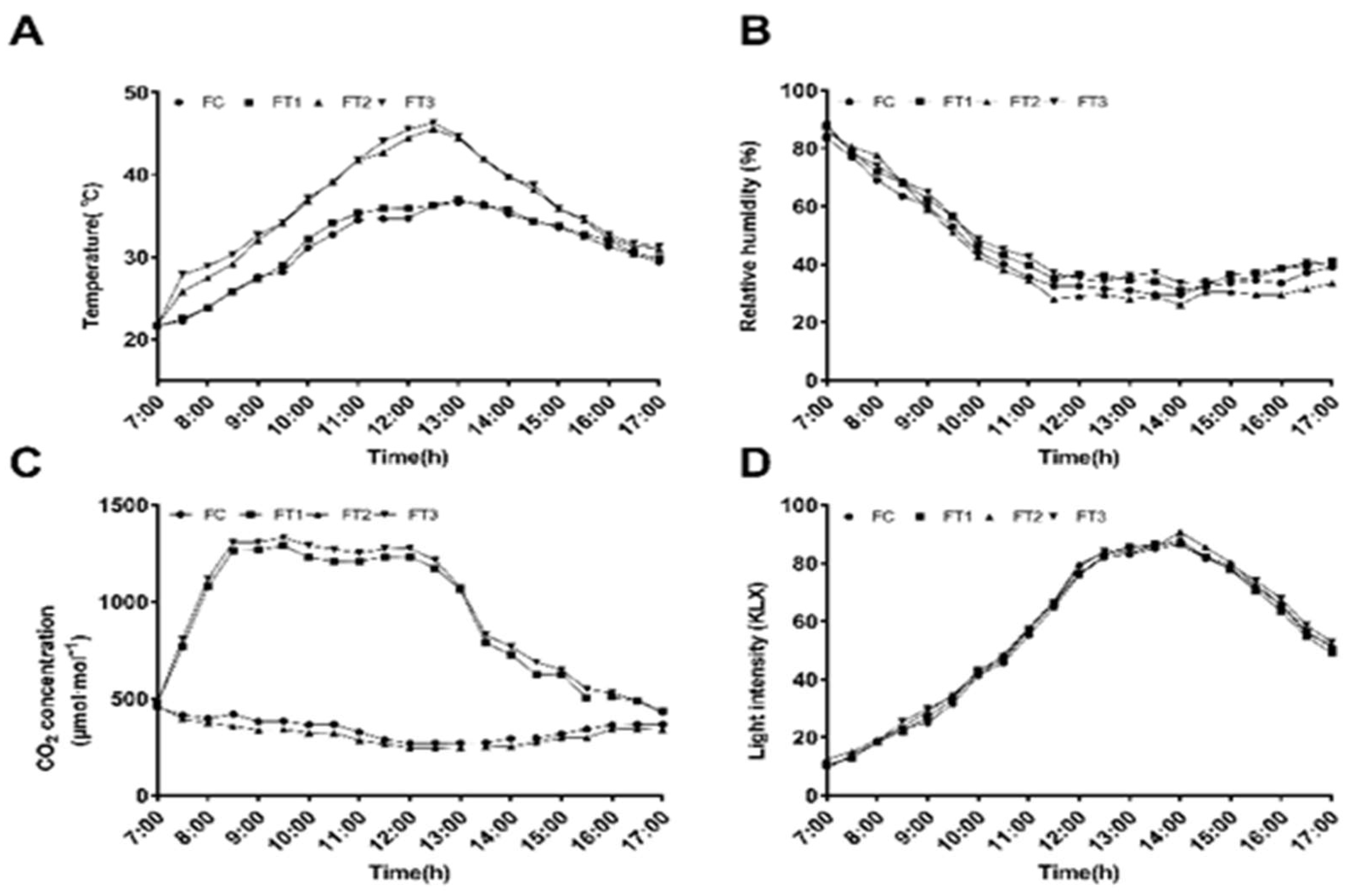

The experiment was conducted at the Free Air Temperature Elevation Facility (FATE) of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, located in the Saihan District of Hohhot, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China (111°41′E, 40°48′N). The greenhouse measures 45 m in length, 7.5 m in width, and 4.2 m in height at the ridge. The test material was cucumber (Cucumis sativus L., ‘Jinyou No. 35’) obtained from the Tianjin Kernel Cucumber Research Institute in Tianjin. This variety is classified as a North China-type cucumber characterized by its robust parthenocarpy, rapid fruit growth rate, and resistance to downy mildew, powdery mildew, and fusarium wilt. It has exhibited exceptional performance in protected cultivation across northern China. Uniformly germinated seeds were chosen and sown in black plastic seedling pots (10 cm in diameter and 9 cm in height) filled with a mixture of peat, vermiculite, and perlite in a volume ratio of 3:1:1. They were subsequently placed in a nursery garden. Following the emergence of four to five true leaves, seedlings exhibiting robust main stems, well-developed root systems, and consistent growth were selected for transplantation into the greenhouse for soil cultivation. Before transplantation, uniform measurements of the greenhouse soil indices were taken: alkali hydrolyzable nitrogen content was 41.3 mg/kg, available phosphorus content was 13.5 mg/kg, available potassium content was 123.7 mg/kg, organic matter content was 11.9 g/kg, conductivity was 516.7 ms/cm, and pH was 7.42. The experiment was designed as a randomized complete block design, comprising control and three treatments: the control treatment maintained a normal temperature of 25 to 35 °C with an ambient CO2 concentration of 400±20 µmol/mol (FC); the second treatment maintained high temperatures of 35 to 45 °C with an ambient CO2 concentration of 400±20 µmol/mol (FT1); the third treatment involved a normal temperature of 25 to 35 °C with an elevated CO2 concentration of 1200±20 µmol/mol (FT2); and the fourth treatment involved high temperatures of 35 to 45 °C with an elevated CO2 concentration of 1200±20 µmol/mol (FT3).

Three replicates were established, each containing 12 cucumber seedlings, resulting in 36 biological replicates per treatment (12 seedlings × 3 replicates). Each treatment area measured 16.5 m², and cultivation was conducted in a ridge double-row strip mode, with row spacing of 50 cm and plant spacing of 30 cm. The treatments were closed and independent of one another. A drip irrigation belt was employed for uniform irrigation. Throughout the experiment, the soil water content for each treatment was maintained at 70 to 80% of the maximum water holding capacity in the field. The greenhouse experiment was conducted from May to July during the summer (based on the local standard for seasonal division in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, defined as an average temperature exceeding 20 °C for 5 consecutive days). After the initial flowering stage of the cucumber, throughout the fruiting period ( 35 days ), the FT2 and FT3 treatments were enriched with CO2 at a concentration of 1200 ± 20 μmol/mol, while the FC and FT1 treatments were maintained at an ambient CO2 level of approximately 400 μmol/mol. CO2 enrichment occurred daily from 7:00 to 12:00 a.m. for a duration of 5 hours. CO2 was supplied from a compressed gas cylinder, controlled by a solenoid valve, and was automatically injected into the greenhouse to sustain the target concentration. The concentration was monitored using a CO2 measuring instrument (TESTO 535; Germany). The CO2-enriched treatment group was ensured to maintain a uniform CO2 concentration throughout the experiment. Other environmental parameters and agronomic management practices were consistent, except for temperature and CO2 concentration variations.

2.2. Measurements of Environmental Factors, Morphological and Physiological Parameters

Every day, from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., the RC-4HC temperature and humidity recorder (Jingchuang Electric Company, Jiangsu) and the illuminance meter (Luge Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou) continuously measured temperature, humidity, and light intensity in the greenhouse. The CO

2 measurement instrument (TESTO 535, Germany) detected CO

2 concentration in each treatment during the test period. Diurnal variations in greenhouse environmental factors were analyzed under different treatments. The quality identification period for fruit and vegetable products is contingent upon their optimal edible or processing maturity, with cucumbers being suitable for harvest at the tender stage of fruit development. The sampling method adhered to the Chinese National Standard Sample for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables (GB 88555-88). Following the commencement of the test, the total number and weight of cucumber fruits were recorded according to the commercial standard throughout the fruiting period ( 35 days ). Measurements of the length and diameter of the cucumber fruits were taken, and calculations were made for the number of fruits per plant, the weight of each fruit, and the yield per plant. At 21 days after the initiation of treatment (full fruit period), eight cucumber plants were randomly selected from each treatment group at 10 a.m. The premarked cucumber fruits developed for 14 days following flowering were harvested from the area near the third layer of functional leaves. Consistent attention was paid to the fruit's position, size, and maturity during sampling. The contents of soluble sugar, starch, ascorbic acid, and nitrite were subsequently determined. The soluble sugar content of the fruits was measured using anthrone sulfuric acid colorimetry[

21], while the starch content was assessed through perchloric acid hydrolysis and anthrone colorimetry[

22]. The ascorbic acid (vitamin C) content was determined using the method specified in China's national standard for analyzing vitamin C in fruits and vegetables (GB6195-86), which employs the colorimetric method. Using the colorimetric method, nitrite levels were assessed according to China's national standard for determining nitrite and nitrate content in fruits, vegetables, and related products (GB/T15401-1994). The test kit was purchased from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China).

Morphological and physiological parameter data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0, USA), including one-way and two-way ANOVA. Before variance analysis, the processed data's normal distribution and homogeneity of variance were evaluated. In cases where the data did not meet the criteria for normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, the Scheirer-Ray-Hare rank-based test was employed. For significant results from variance analysis, the Tukey test was utilized to compare significant differences between treatments at a significance level of P < 0.05. Graphical representations were created using GraphPad Prism 9.0.

2.3. Preparation of Samples for UHPLC-Q-TOF MS and Data Processing

At 21 days after the initiation of treatment (full fruit period), eight cucumber plants were randomly selected from each treatment group at 10 a.m. The premarked cucumber fruits developed for 14 days following flowering were harvested from the area near the third layer of functional leaves. Careful attention was given to the fruit's position, size, and maturity during sampling for metabolomic analysis. Following independent sampling, the fruits were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. After 20 minutes, they were transferred to an ultralow-temperature refrigerator for preservation.

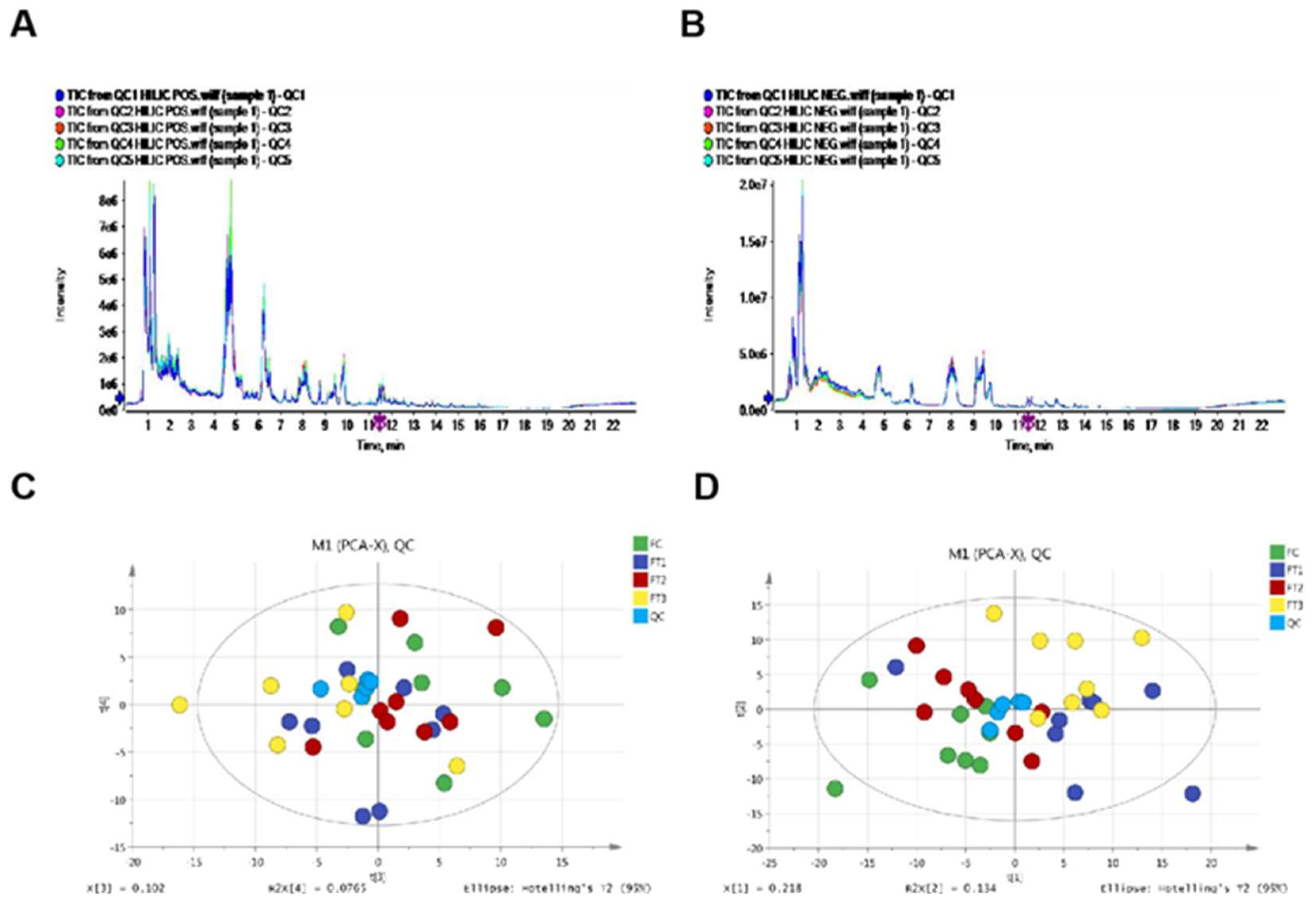

Each biological replicate sample was ground in liquid nitrogen. Approximately 80 mg of each sample was weighed, and 1 ml of a methanol/acetonitrile/water solution (2:2:1, v/v) was added. The samples were vortex mixed and subjected to ultrasonic crushing at low temperature for 30 minutes, repeated twice. They were then incubated at -20 °C for 1 hour to precipitate proteins, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 minutes. The supernatant was lyophilized and stored at -80 °C for metabolomic analysis of cucumber fruits. Samples were mixed in equal amounts to prepare quality control (QC) samples. These QC samples were utilized to assess instrument status before injection, ensure equilibrium in the chromatography mass spectrometry system, and evaluate system stability throughout the experiment.

The UHPLC-Q-TOF MS analysis was conducted using a UHPLC system (1290 Infinity LC, Agilent Technologies, USA) equipped with a UPLC BEH amide column (1.7 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters, USA) coupled to a Triple TOF 5600 (Q-TOF, AB Sciex, USA).

Chromatographic conditions for HILIC separation involved analyzing the samples with a 2.1 mm × 100 mm ACQUIY UPLC BEH 1.7 µm column (Waters, Ireland) at a column temperature of 25 °C and a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. The injection volume was set at 2 µL. In both positive and negative modes of ESI, the mobile phase consisted of A = 25 mM ammonium acetate, 25 mM ammonium hydroxide in water and B = acetonitrile. The gradient elution procedure was as follows: the gradient commenced at 95% B for 1 min, then linearly decreased to 65% over 13 min, subsequently reduced to 40% over 2 min and maintained for 2 min before increasing back to 95% in 0.1 min. A 5-minute re-equilibration period was employed at 95%. During the analysis, the samples were placed in an automatic sampler at 4 °C. Continuous sampling was conducted randomly to mitigate the effects of fluctuations in the instrument’s detection signal. Quality control (QC) samples were incorporated into the sample queue to monitor and assess the stability and reliability of the experimental data generated by the system.

Q-TOF mass spectrometry conditions: Analytes were detected using electrospray ionization (ESI) in both positive and negative ion modes. The samples were separated by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) and analyzed with a triple TOF 5600 mass spectrometer (Q-TOF, AB SCIEX, USA). The ESI source conditions were optimized as follows: ion source gas 1 (Gas1) set to 60, ion source gas 2 (Gas2) set to 60, curtain gas (CUR) set to 30, source temperature at 600 °C, and IonSpray Voltage Floating (ISVF) at ±5500 V. The TOF MS scan m/z range was 60-1000 Da, while the product ion scan m/z range was 25-1000 Da. The TOF MS scan accumulation time was 0.20 s/spectrum, and the product ion scan accumulation time was 0.05 s/spectrum. The product ion scan was conducted using information-dependent acquisition (IDA) with high sensitivity mode selected. The declustering potential (DP) was set to ±60 V for both positive and negative modes, and the collision energy was set to 35 ± 15 eV. The IDA parameters included the exclusion of isotopes within 4 Da and the monitoring of 6 candidate ions per cycle. The raw MS data (wiff. scan files) were converted to MzXML files using ProteoWizard MSConvert and processed with XCMS for feature detection, retention time correction, and alignment. Metabolites were identified based on precision mass (<25 ppm) and MS/MS data that matched the standard database. For the data extracted by XCMS, only variables with more than 50% non-zero measurement values were retained in at least one group. Pattern recognition was performed using SIMCA-P14.1 software (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden).

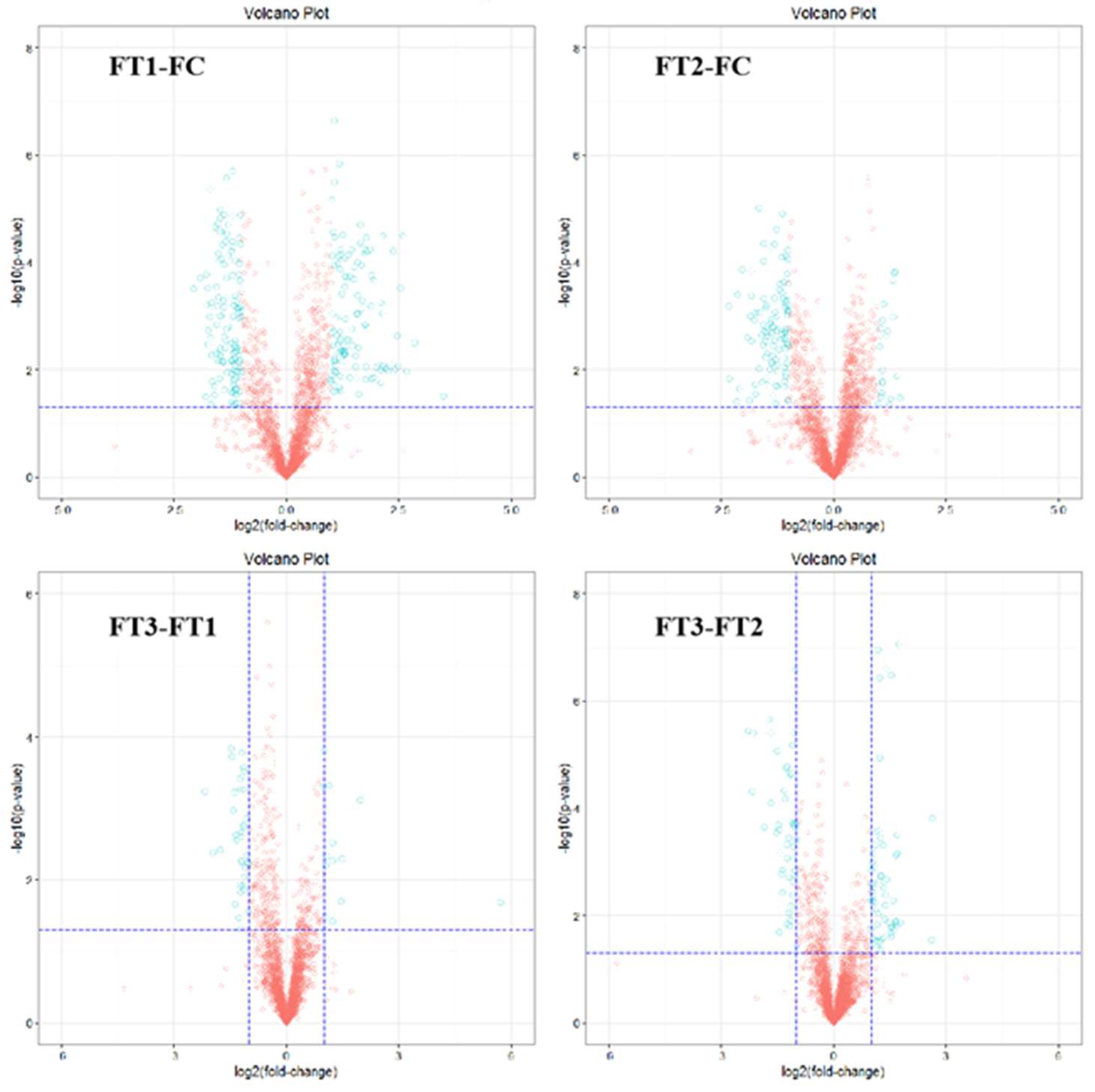

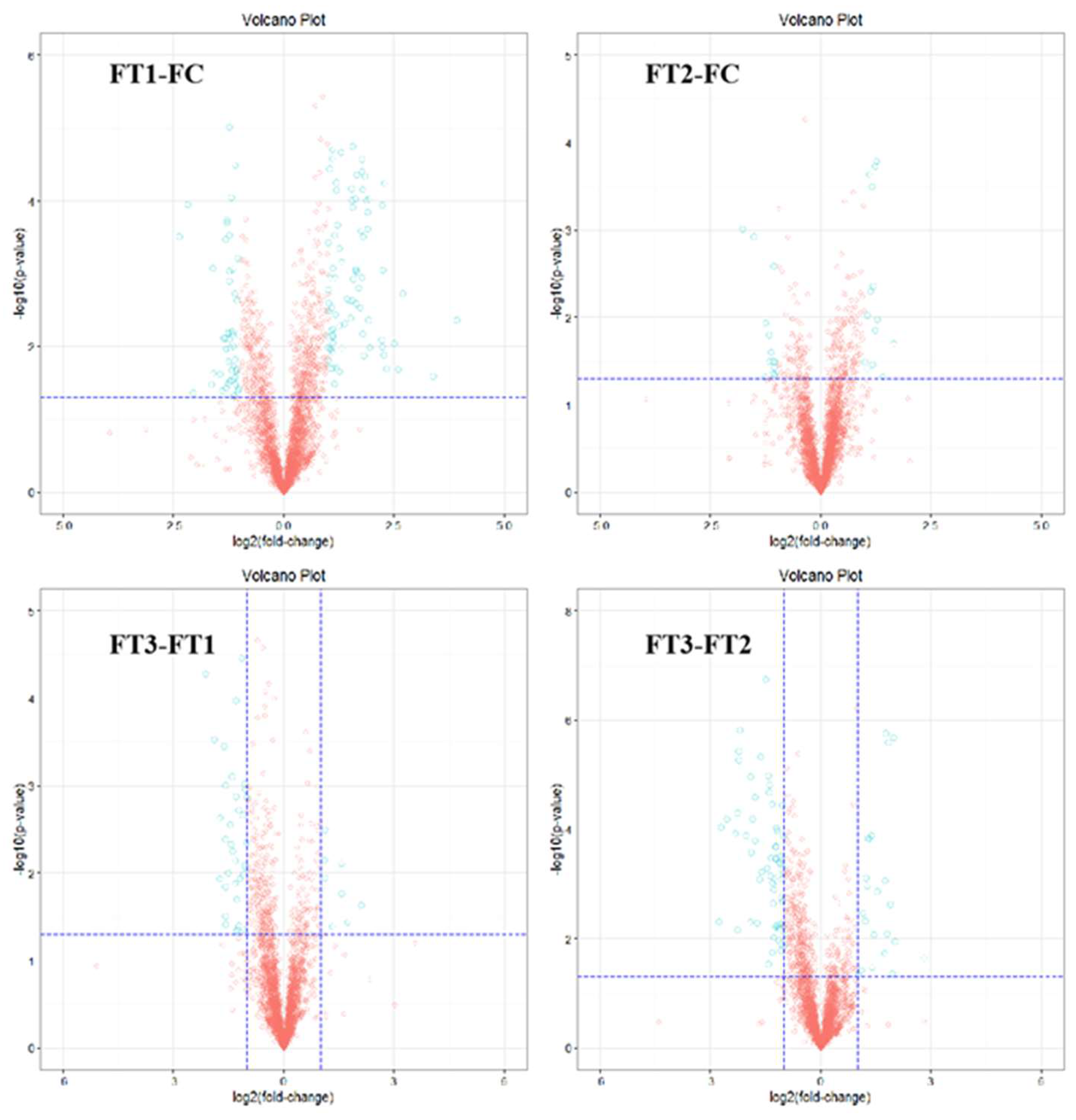

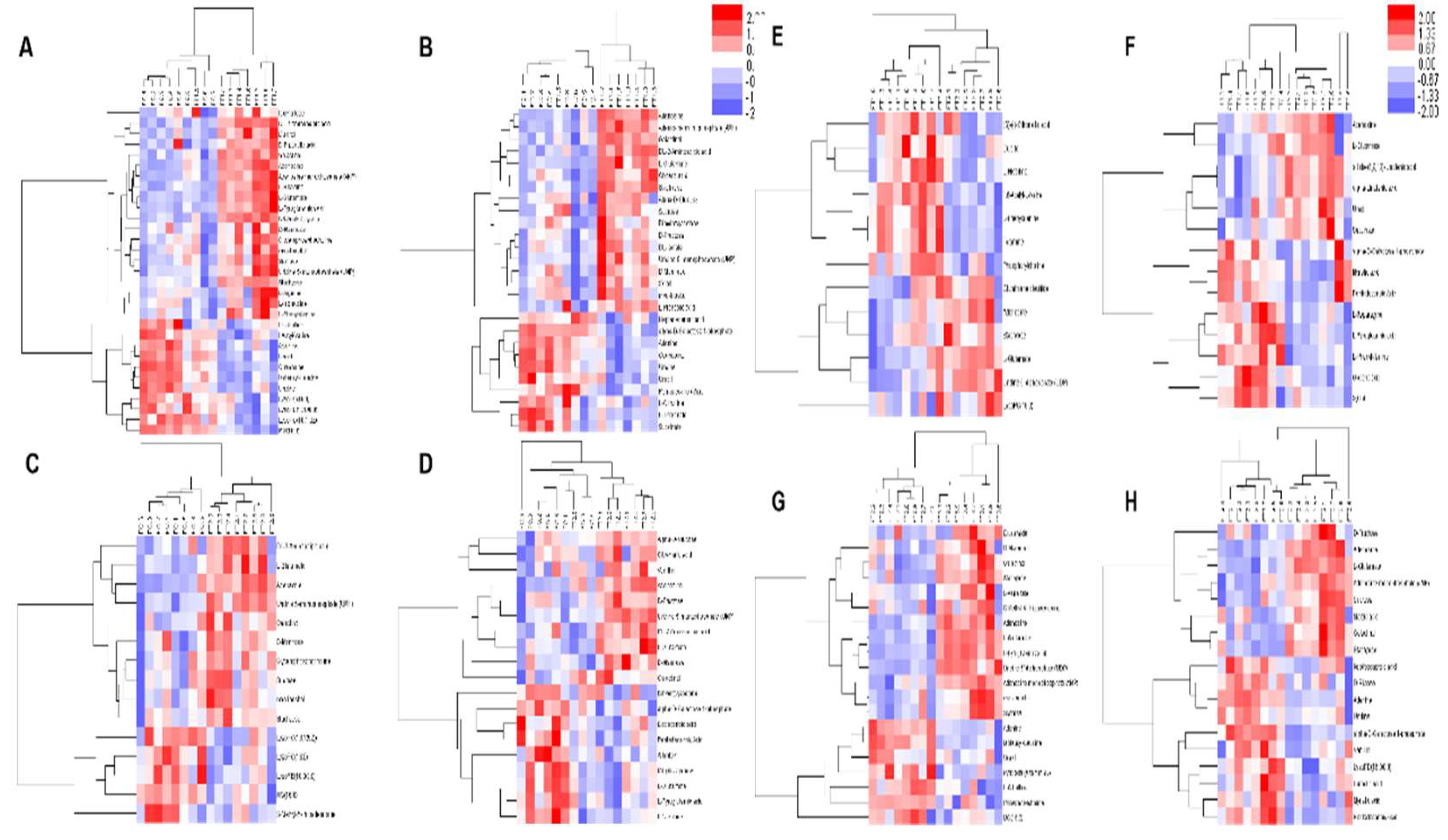

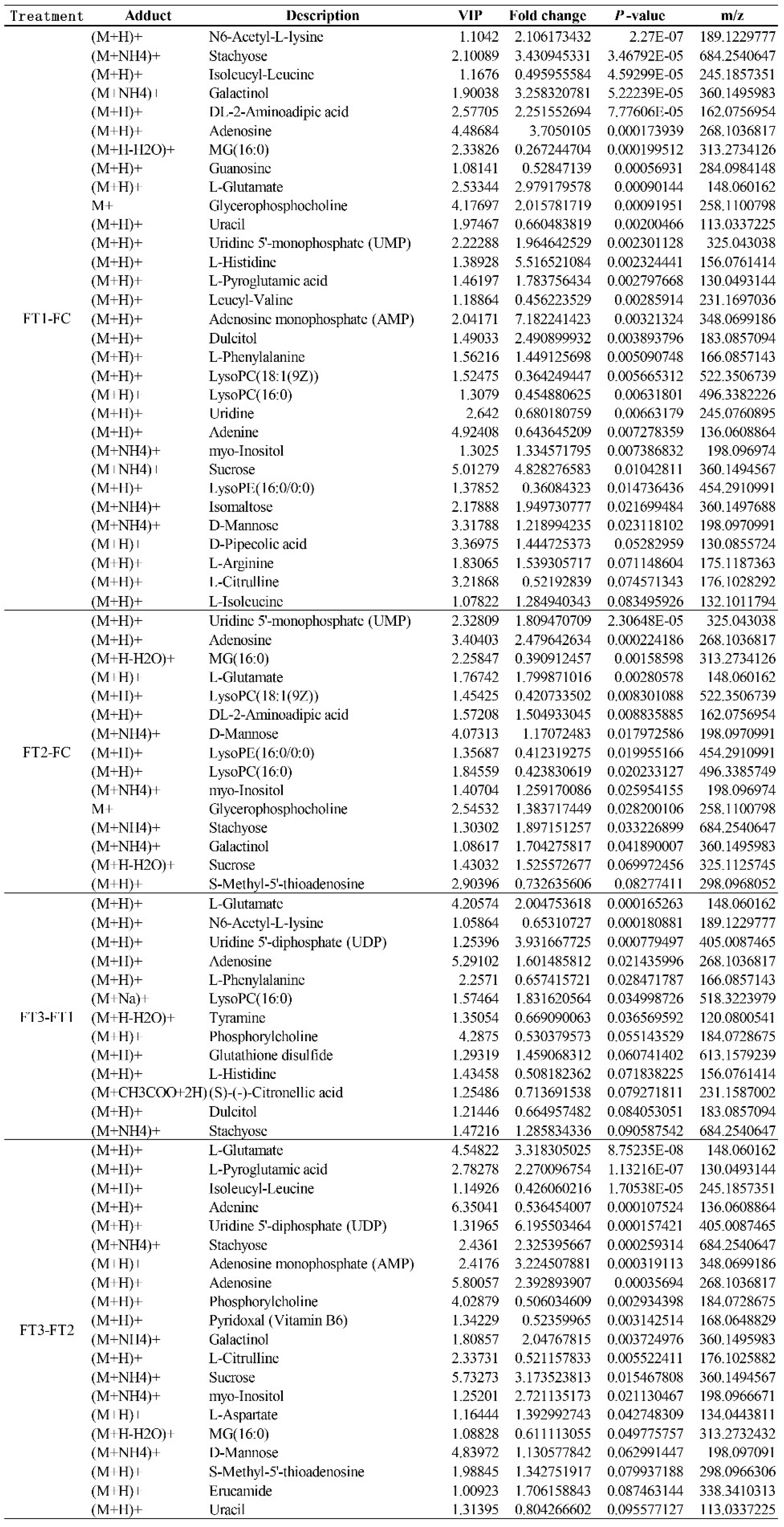

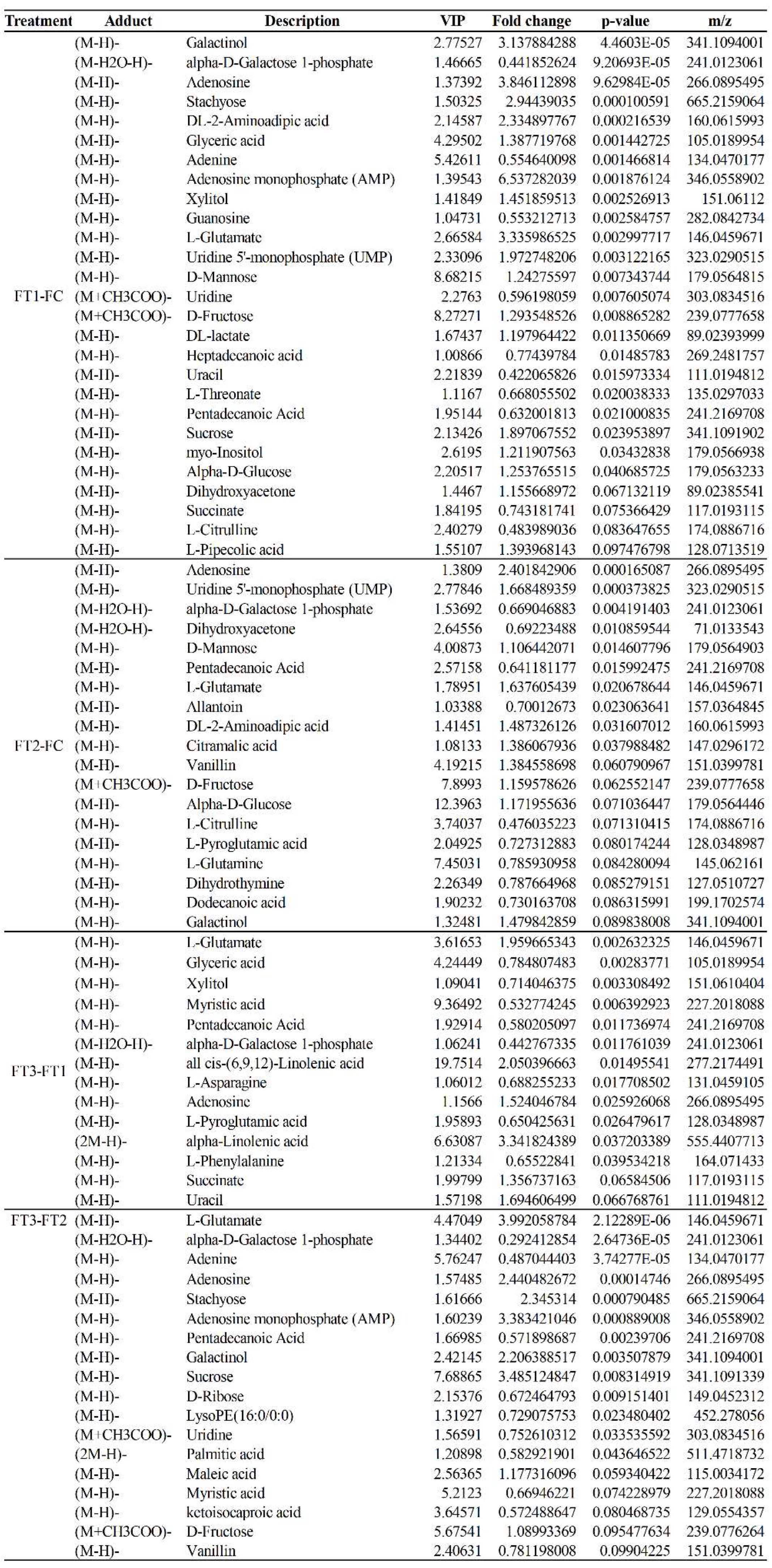

After Pareto scaling preprocessing, multidimensional statistical analyses were conducted, including unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA), supervised partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). Cross-validation and response permutation were employed for leave-one-out and re-validation to assess the robustness of the model. Significantly different metabolites were identified based on a combination of a statistically significant threshold for variable influence on projection values (VIP) derived from the PLS-DA model and the results of a two-tailed Student's t-test on the raw data. Metabolites with VIP values greater than 1.0 and

P-values less than 0.1 were deemed significant. Additionally, commercial databases, including KEGG (

http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and MetaboAnalyst (

http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/), were utilized to explore metabolite pathways.

4. Discussion

Climate change is leading to a significant increase in global average temperatures, threatening crop yields and food security. Various strategies have been adopted to enhance the heat tolerance of vegetables and address the dynamic factors that affect modern agricultural production. These strategies include cultivating heat-tolerant varieties, modifying cultivation practices, and increasing CO

2 levels. The crops predominantly grown in greenhouses are C3 plants, such as tomatoes and cucumbers, which generally respond more positively to increased CO

2 concentrations.[

6]. At CO

2 levels of 550 to 650 μmol/mol, the yield of C3 crops can increase on average by 18%[

23]. Furthermore, at approximately 1000 μmol/mol CO

2 concentration, the soluble sugars and certain nutrients in leafy vegetables, fruits and root vegetables can increase from 10% to 60%[

24]. Elevated CO

2 levels facilitate various physiological activities in C3 crops, including photosynthesis, signaling pathways, and organ development, thereby improving yield, quality, and the resilience of vegetables to abiotic stress[

25,

26,

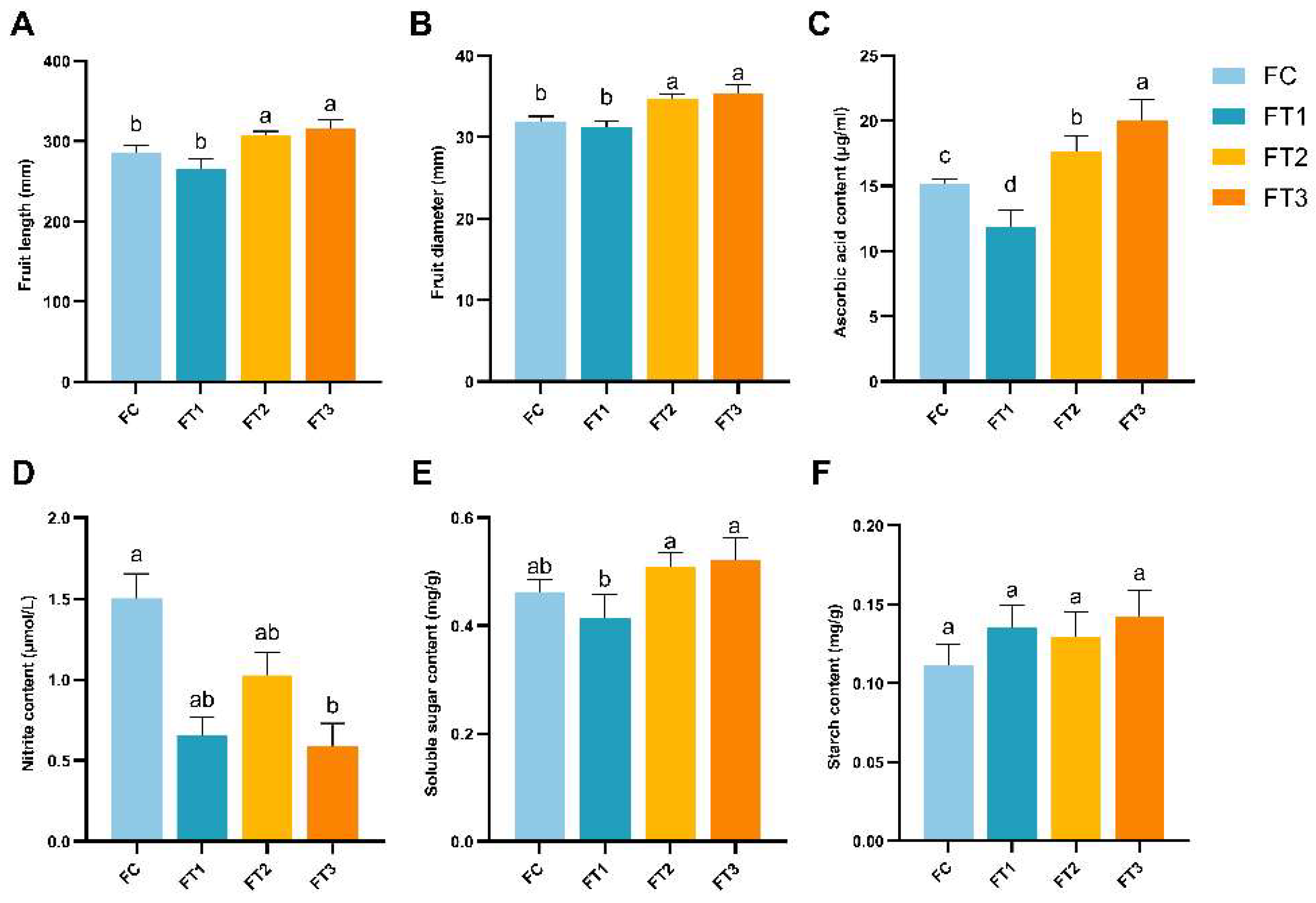

27]. This study demonstrates that high temperature conditions inhibit the growth of cucumber fruits while elevated CO

2 levels significantly enhance their growth. Specifically, elevated CO

2 increases the length and diameter of cucumber fruits under normal and high temperature conditions while also boosting the contents of soluble sugars and vitamin C and notably reducing nitrite levels in the fruits. When comparing a high CO

2 environment at normal temperature, the combination of elevated temperature and CO

2 concentration markedly improves the number of cucumbers per plant, the weight of each cucumber, and the overall yield per plant, ultimately resulting in the highest harvest volume achieved within the same picking cycle of 35 days. The quality of the fruit aligns more closely with commercial picking standards.

When plants encounter growth-detrimental factors, they rapidly adjust at multiple levels to ensure survival. These responses constitute a complex process that produces mass metabolic intermediates and end products. High-throughput metabolomics elucidates structurally diverse, nutrition-rich metabolites and their intricate interactions within vegetable plants [

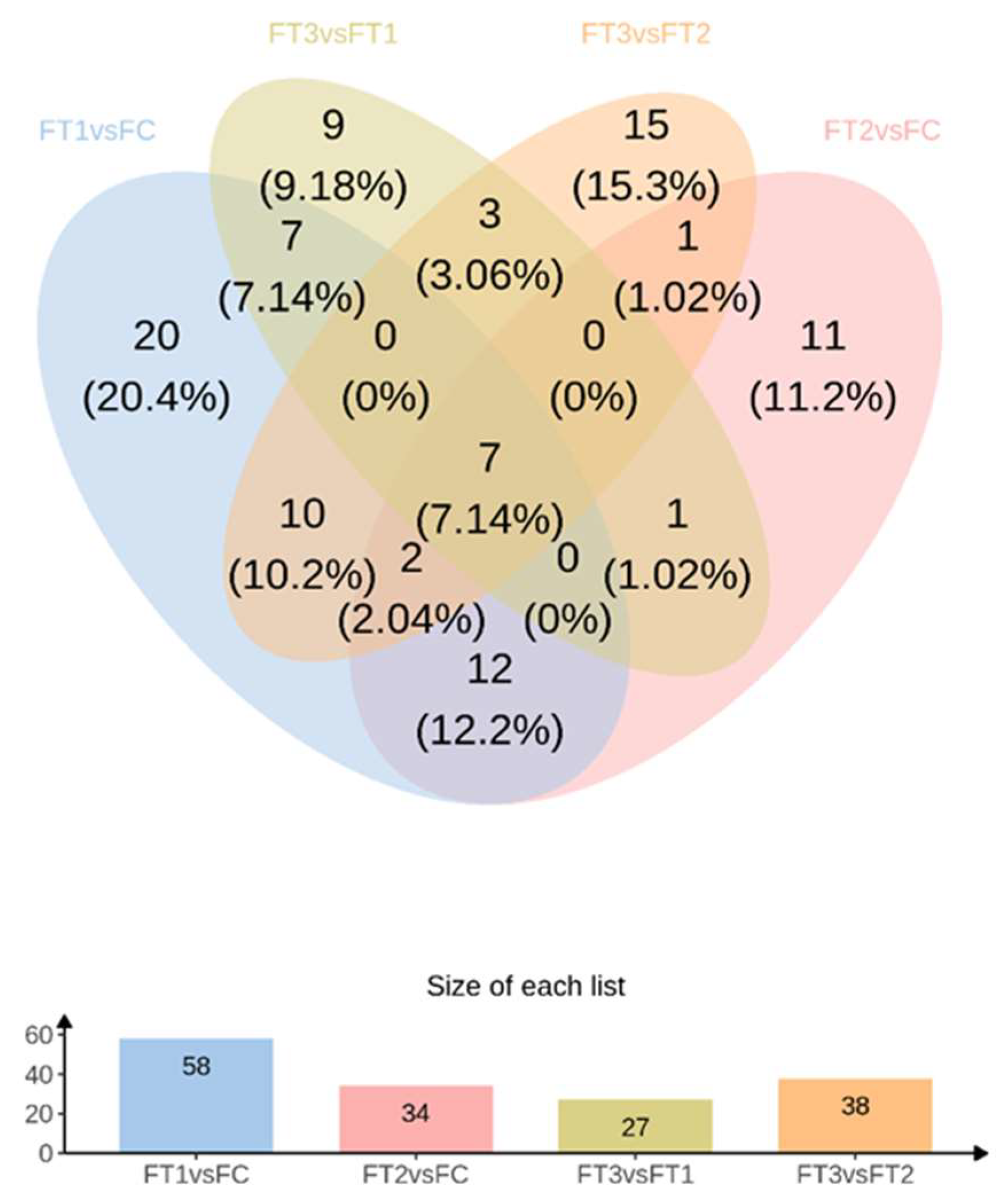

13]. This approach has facilitated the connection between identified phytometabolites and unique phenotypic traits, nutri-functional characteristics, defense mechanisms, and crop productivity, thus improving our understanding of the principles governing plant life activities at the molecular level. In this study, metabolomics analysis utilizing ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-TOF MS) revealed significant differences in differential metabolites of greenhouse cucumber fruits under varying temperature and CO

2 concentration conditions. In general, the effect of temperature on the metabolites of the cucumber fruit was more pronounced. In positive and negative ion modes, 58 differential metabolites were identified under FT1-FC, with 20 metabolites unique to FT1-FC. Significantly different metabolites included guanosine, leucylvaline, uridine, isomaltose, xylitol, D-mannose, DL-lactate, heptadecanoic acid, L-threonate, sucrose, myo-inositol, and alpha-D-glucose. Plants utilize various metabolic strategies to cope with heat stress. A study comparing tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.) exposed to temperatures of 45°C and 50°C for one hour daily over seven days against those grown at 25°C revealed a significant positive correlation between heat stress and total phenolic content[

28]. Scarano et al. [

29]measured β-carotene concentrations in tomato fruits subjected to heat stress conditions in the field, specifically at temperatures exceeding 32°C. The results demonstrated a significant increase in β-carotene concentration in the heat-stressed plants compared to the control group. In this study, cucumber fruits exposed to high-temperature conditions accumulated higher levels of amino acid compounds, such as L-threonate, L-citrulline, and Valine, than those grown under normal conditions. These findings suggest that heat stress may influence the concentration of potentially beneficial nutrients, particularly in fruits.

In the FT2-FC group, 34 differential metabolites were identified, of which 11 were unique to FT2-FC. Significantly different metabolites included dihydroxyacetone, D-mannose, allantoin, and citric acid. Polyols, such as myoinositol, sorbitol, mannitol, and galactitol, are derivatives of sugars. The accumulation of these low molecular weight, uncharged molecules facilitates osmotic adaptation, thereby protecting membrane and cellular proteins from stress. The plant-protective metabolite citric acid, also known as citrate (CA), has emerged as an effective means to enhance plant adaptability to environmental stress, thus maintaining growth and development[

30,

31]. Alternating oxidase (AOX) can reduce reactive oxygen species levels by enhancing mitochondrial electron transport capacity and inhibiting O

2¯ production. Notably, citric acid is the most significant reported inducer of alternating oxidase expression. An increased endogenous citric acid content, whether through in vivo metabolism or exogenous administration, may decrease reactive oxygen species by elevating the activity of alternative oxidases. Foliar spraying of calcium (CA) at a concentration of 200 ppm can effectively mitigate salt stress in eggplant by enhancing plant biomass, pigment levels, primary and secondary metabolites and modulating antioxidant defense systems[

32]. Additionally, some studies have indicated that high temperatures influence citrate synthase. Plants can withstand thermal stress by alleviating the denaturation of citrate synthase and promoting the renaturation of the denatured enzyme. Under elevated temperatures, plants enhance mitochondria's heat resistance and improve overall plant heat tolerance by effectively protecting citrate synthase. A related study reported that citric acid accumulates in plants during high-temperature stress, primarily functioning as an antioxidant and an intermediate product of respiratory metabolism, thereby aiding in thermal stress management[

33]. Furthermore, spraying of 20 mM CA on leaves of Lolium arundicaceum significantly improved photosynthetic efficiency, Chl biosynthesis, and activity of antioxidant enzymes[

34]. This study found cucumber fruits cultivated under normal temperature conditions to scavenge reactive oxygen species by accumulating citrate and related metabolites. However, these metabolites did not exhibit upregulation with increasing CO₂ concentrations. This observation suggests that even under normal temperature conditions, enhanced CO₂ application can help mitigate stress-induced reactive oxygen damage and improve the stress tolerance of cucumber fruits.

In the FT3-FT1 group, 27 differential metabolites were identified, of which 9 were unique to FT3-FT1. Significant metabolites in this group included tyramine, xylitol, linolenic acid, L-asparagine, alpha-linolenic acid, and L-phenylalanine. In our study, the application of elevated CO₂ levels under high-temperature stress resulted in the up-regulation of L-phenylalanine in cucumber fruits. Phenylalanine is a critical substrate in the phenylpropanoid pathway, responsible for synthesizing various compounds, including phenylpropanoids, flavonoids, isoflavones, and anthocyanins [

35]. Li et al. demonstrated that the phenylalanine content in cucumber leaves increased significantly under moderate and severe drought stress, suggesting a potential link between drought sensitivity and elevated phenylalanine levels in plant tissues[

16,

33]. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) catalyzes the deamination of L-phenylalanine into trans-cinnamic acid[

34,

35]. This pathway generates a range of aromatic metabolites, such as flavonoids, isoflavones, and lignin [

36]. Consequently, PAL plays a vital role in the biosynthesis of multiple secondary metabolites essential for plant growth and development. Beyond its importance in these processes, PAL is also a crucial enzyme in plant stress responses. Its expression is influenced by various factors, including drought [

36], pathogen attack, tissue damage, extreme temperatures, ultraviolet radiation, nutrient deficiency[

37], and plant signaling molecules such as jasmonic acid (JA) [

38], salicylic acid (SA)[

39], and abscisic acid (ABA)[

40]. After stimulation by different stresses, the expression of the PAL gene is rapidly induced at the transcriptional level [

42]. During HT3h (3 hours of heat stress), CsPAL9 was significantly upregulated, while during HT6h (6 hours of heat stress), both CsPAL9 and CsPAL7 exhibited increased expression, indicating their potential involvement in cucumber's tolerance to heat stress[

41]. In the future, enhancing the expression of PAL genes may provide a viable strategy to improve plant resistance to various stresses.

In the FT3-FT2 group, 38 differential metabolites were identified, of which 15 were unique to FT3-FT2. Significantly different metabolites included pyridoxal (vitamin B6), L-citrulline, myo-inositol, L-aspartate, MG (16:0), sucrose, D-ribose, and palmitic acid. High temperatures induced alterations in the levels of amino acids, sugars, and organic acid metabolites in cucumber fruits. Amino acids and sugar play a crucial role in the response of higher plants to abiotic stresses. Their derivatives are essential for maintaining intracellular protein structural integrity and osmotic regulation [

28,

29]. Under heat stress, Arabidopsis and rice accumulate various amino acids, including threonine, isoleucine, leucine, asparagine, malic acid, valine and alanine[

30,

31]. These findings suggest that the accumulation of metabolites, such as amino acids, sugars, and organic acids, in response to high temperature stress may be vital to adapt cucumber fruits to elevated temperatures.

In response to increased CO₂ concentrations under varying temperature conditions, two common differential metabolites were identified in the FT2-FC, FT3-FT1, and FT3-FT2 treatments: L-glutamic acid and stachyose. L-glutamic acid serves as a precursor for chlorophyll a, while the glutamate pathway is the primary source of proline synthesis under osmotic stress[

42]. In both normal and high-temperature environments, increased CO₂ concentration reduces L-glutamic acid content. This decrease may be attributed to a lowered level of α-ketoglutarate, the precursor of glutamate, or to the rise in CO₂ concentration that mitigates high-temperature stress, thereby downregulating the typical metabolic response to such stress. Stachyose, a soluble oligosaccharide, is a fuel for growth and development and acts as a precursor and signaling molecule in metabolism. Furthermore, it provides osmotic protection under stress conditions and is integral to the reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging system. Stachyose is associated with trehalose metabolism, galactose metabolism, and starch and sucrose metabolism. The accumulation of these carbohydrates in the FC, FT1, and FT2 treatments plays a crucial role in osmotic regulation and protecting cell membranes in cucumber fruits under the corresponding environmental conditions [

43].

The enrichment analysis of the KEGG annotation for differential metabolites in cucumber fruit revealed that 11 metabolic pathways were significantly enriched in the FT1-FC group, 11 in the FT2-FC group and 15 in the FT3-FT1 group. In comparison, 14 metabolic pathways were significantly enriched in the FT3-FT2 group. In particular, the galactose metabolism pathway emerged as the most significantly affected pathway in this enrichment analysis. In experiments evaluating the effects of high temperature and elevated CO

2 concentration on cucumber fruit quality in greenhouses, the impacts of high temperature and elevated CO

2 levels on the soluble sugar and starch content of cucumber fruits were found to be insignificant. However, elevated CO

2 concentrations significantly increased the ascorbic acid content in the treatment groups FT2 (17.66±0.68 μg/ml) and FT3 (20.04±0.89 μg/ml) treatment groups. Ascorbic acid (AsA) is an essential redox compound in plant leaves and fruits, playing a critical role in various physiological processes, including the regulation of plant aging [

44], protection of photosynthetic structures[

45], sugar metabolism[

46], and responses to stress. AsA is synthesized primarily in source leaves and transported to storage tissues via the phloem. Plants have an efficient AsA transmembrane and long-distance transport system [

47]. Garchery et al. demonstrated that increasing the ascorbic acid (AsA) content in tomato leaves while reducing the activity of ascorbic acid oxidase in tomato fruits can enhance the transport of sucrose from source leaves to sink tissues, thereby increasing the diameter and yield of transformed tomato fruits [

48]. The positive correlation between ascorbic acid (AsA) content and fruit yield can be attributed to the role of AsA in maintaining photosynthesis and respiration [

49]. The galactose pathway is the primary pathway for plants to synthesize AsA. High temperature stress significantly alters the response patterns of antioxidant transcription and enzyme activity in cucumber fruits. Following acute oxidative stress, the differential metabolites produced primarily function to maintain or enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes and mitigate cell membrane lipid peroxidation. Consequently, the galactose metabolism pathway observes a greater abundance of differential metabolites (map00052). The accumulation of cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine is crucial for synthesizing the antioxidant glutathione. Cucumber fruits in the FT3 group, which maintain a higher amino acid content, exhibit a greater potential to withstand significant high temperature stress. Increased CO

2 application complicates metabolic pathways by enriching the changes in differential metabolites of cucumber fruits. Under high-temperature stress, cucumber fruits increase their resistance to stress by accumulating metabolites associated with sugar, organic acids and amino acids, particularly within the galactose metabolism pathway, arginine biosynthesis pathway, and glutamate synthesis pathway.