Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Equations

2.2. Model Input Parameters

2.3. Vessel Responses to Transmural Pressure Variations

3. Results

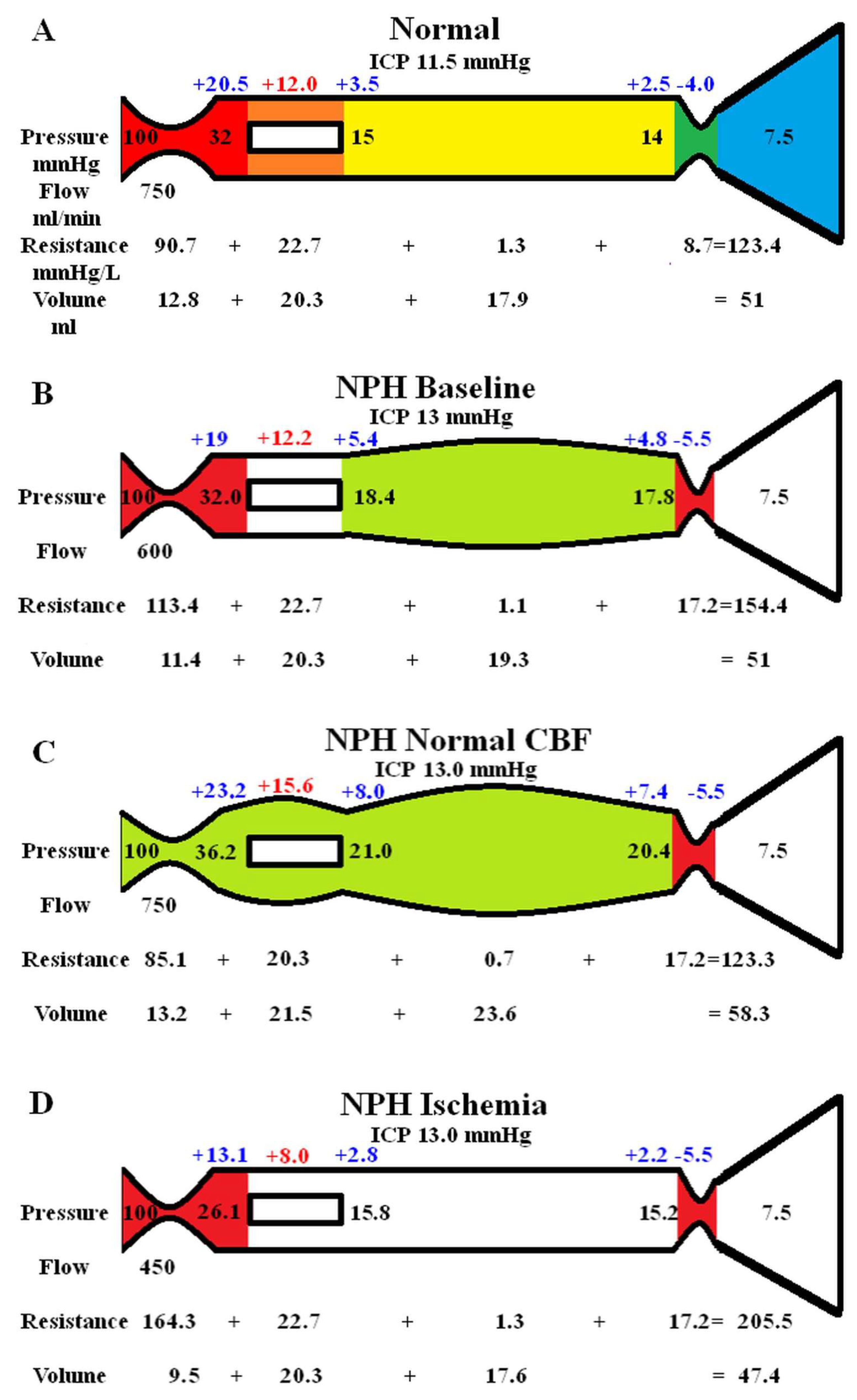

3.1. Varying Blood Flow in NPH

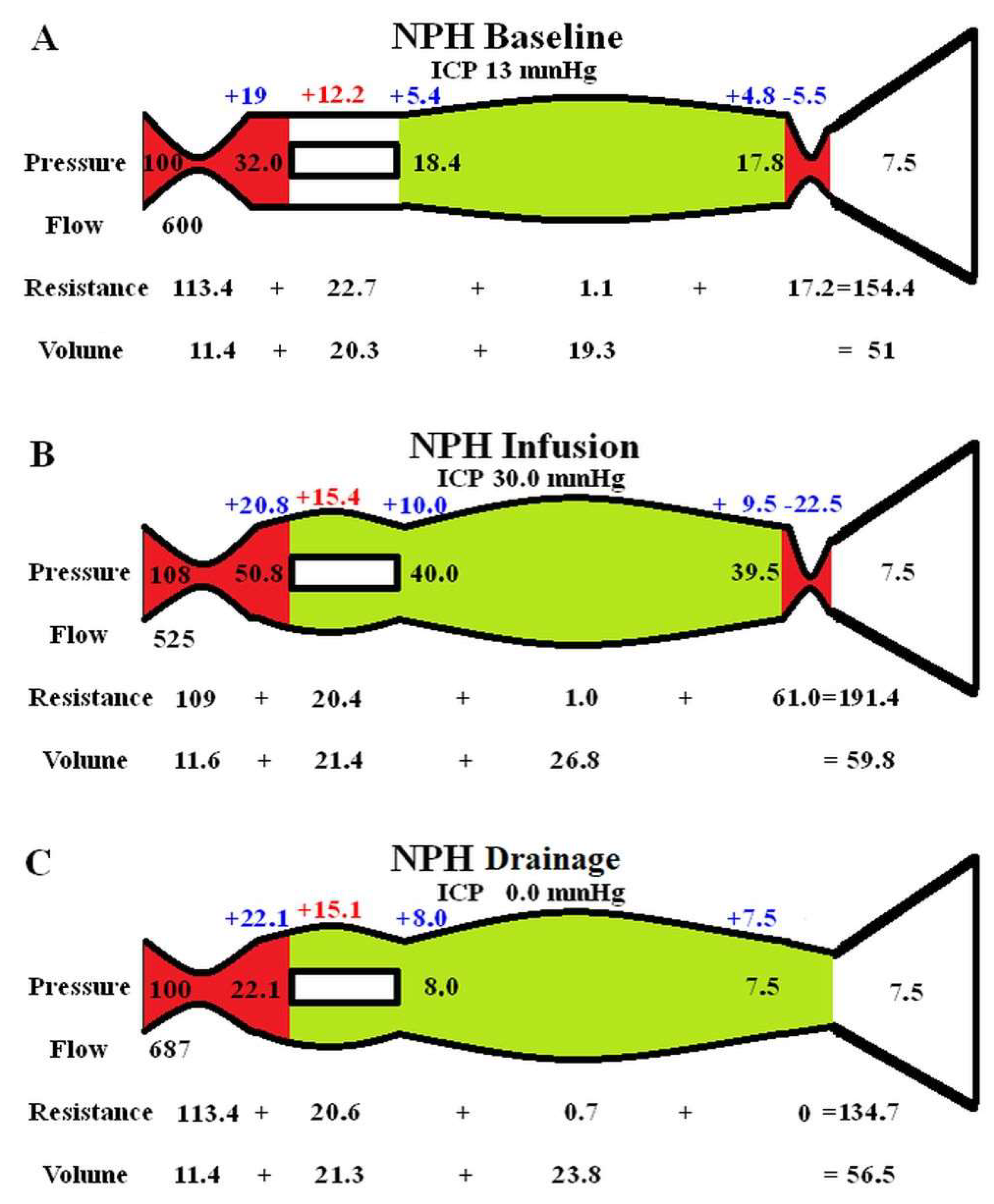

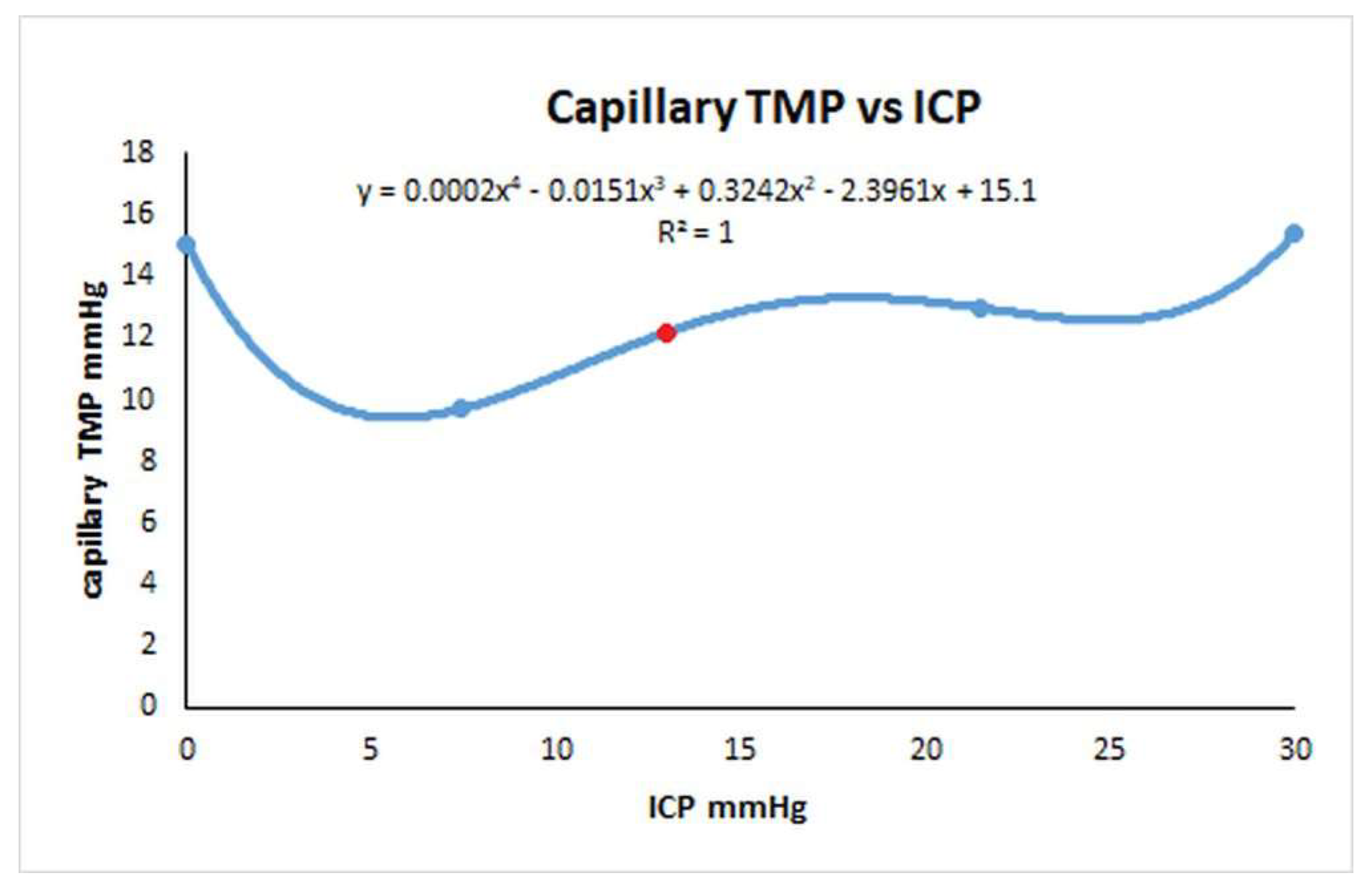

3.2. Varying the ICP in NPH

4. Discussion

4.1. Variation in Rout in NPH

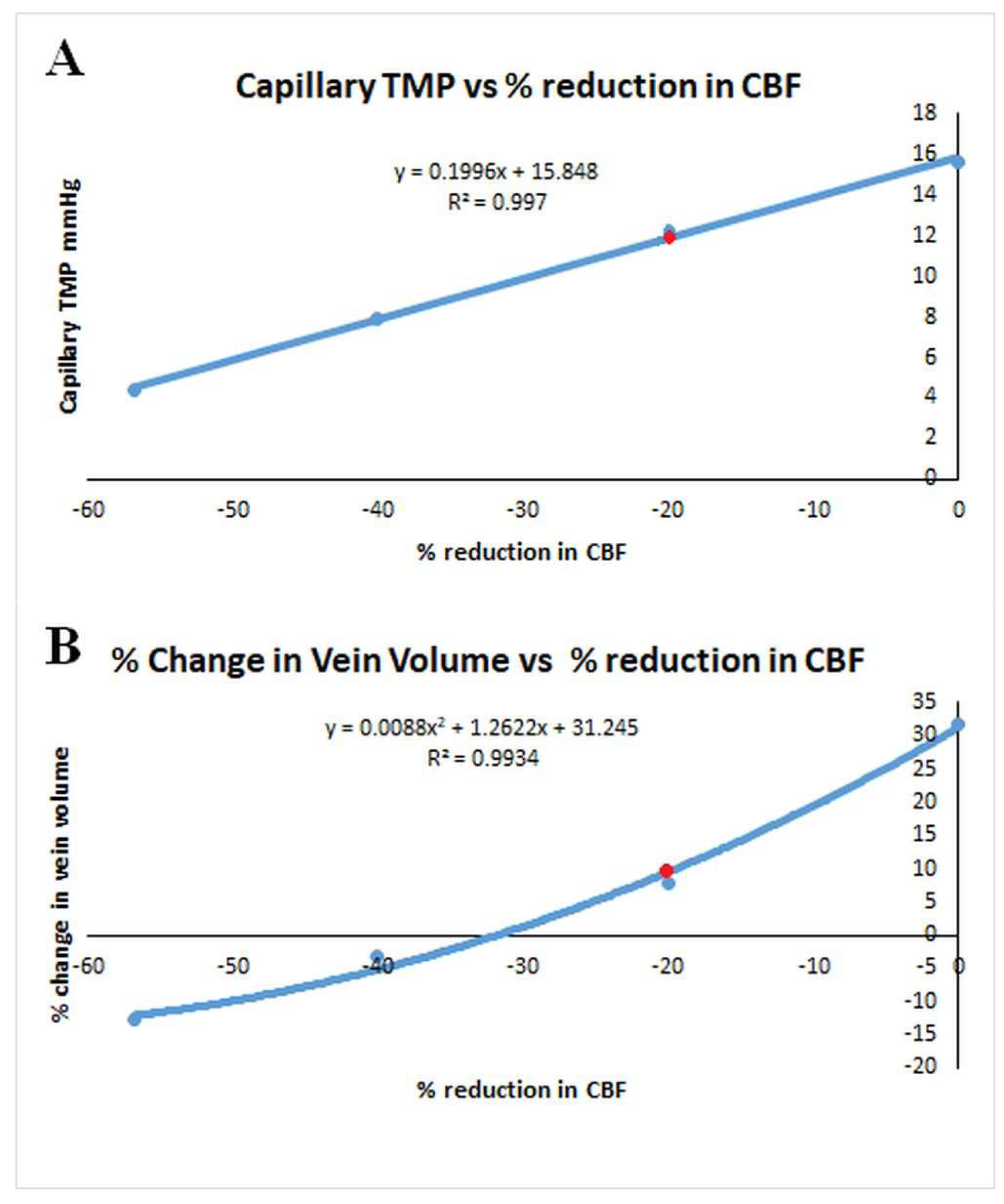

4.2. Variation in CSFfr with Capillary TMP

4.3. Differences Between Cortex and Periventricular White Matter in NPH

4.4. Which Test for ROUT in NPH is Most Accurate?

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, R.D.; Fisher, C.M.; Hakim, S.; Ojemann, R.G.; Sweet, W.H. Symptomatic Occult Hydrocephalus with "Normal" Cerebrospinal-Fluid Pressure. A Treatable Syndrome. N Engl J Med 1965, 273, 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Davson, H.; Welch, K.; Segal, M.B. Physiology and Pathophysiology of the Cerebrospinal Fluid; Churchill Livingstone: 1987.

- Chabros, J.; Placek, M.M.; Chu, K.H.; Beqiri, E.; Hutchinson, P.J.; Czosnyka, Z.; Czosnyka, M.; Joannides, A.; Smielewski, P. Embracing uncertainty in cerebrospinal fluid dynamics: A Bayesian approach to analysing infusion studies. Brain Spine 2024, 4, 102837. [CrossRef]

- Jannelli, G.; Calvanese, F.; Pirina, A.; Gergele, L.; Vallet, A.; Palandri, G.; Czosnyka, M.; Czosnyka, Z.; Manet, R. Assessment of CSF Dynamics Using Infusion Study: Tips and Tricks. World Neurosurg 2024, 189, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, G.D.; Huhn, S.; Jaffe, R.A.; Chang, S.D.; Saul, T.; Heit, G.; Von Essen, A.; Rubenstein, E. Downregulation of cerebrospinal fluid production in patients with chronic hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg 2002, 97, 1271–1275. [CrossRef]

- MASSERMAN, J.H. CEREBROSPINAL HYDRODYNAMICS: IV. CLINICAL EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES. Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry 1934, 32, 523–553. [CrossRef]

- Qvarlander, S.; Sundstrom, N.; Malm, J.; Eklund, A. CSF formation rate-a potential glymphatic flow parameter in hydrocephalus? Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 55. [CrossRef]

- Tariq, K.; Toma, A.; Khawari, S.; Amarouche, M.; Elborady, M.A.; Thorne, L.; Watkins, L. Cerebrospinal fluid production rate in various pathological conditions: a preliminary study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2023, 165, 2309–2319. [CrossRef]

- Fleischman, D.; Berdahl, J.P.; Zaydlarova, J.; Stinnett, S.; Fautsch, M.P.; Allingham, R.R. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure decreases with older age. PLoS One 2012, 7, e52664. [CrossRef]

- Benabid, A.L.; De Rougemont, J.; Barge, M. [Cerebral venous pressure, sinus pressure and intracranial pressure]. Neurochirurgie 1974, 20, 623–632.

- Bateman, G.A.; Siddique, S.H. Cerebrospinal fluid absorption block at the vertex in chronic hydrocephalus: obstructed arachnoid granulations or elevated venous pressure? Fluids Barriers CNS 2014, 11, 11. [CrossRef]

- Czosnyka, M.; Czosnyka, Z.H.; Whitfield, P.C.; Donovan, T.; Pickard, J.D. Age dependence of cerebrospinal pressure-volume compensation in patients with hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg 2001, 94, 482–486. [CrossRef]

- Boon, A.J.; Tans, J.T.; Delwel, E.J.; Egeler-Peerdeman, S.M.; Hanlo, P.W.; Wurzer, H.A.; Avezaat, C.J.; de Jong, D.A.; Gooskens, R.H.; Hermans, J. Dutch normal-pressure hydrocephalus study: prediction of outcome after shunting by resistance to outflow of cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurosurg 1997, 87, 687–693. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. A lumped parameter modelling study of cerebral autoregulation in normal pressure hydrocephalus suggests the brain chooses to be ischemic. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 24373. [CrossRef]

- Zislin, V.; Rosenfeld, M. Impedance Pumping and Resonance in a Multi-Vessel System. Bioengineering (Basel) 2018, 5. [CrossRef]

- del Zoppo, G.J.; Sharp, F.R.; Heiss, W.D.; Albers, G.W. Heterogeneity in the penumbra. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011, 31, 1836–1851. [CrossRef]

- Ursino, M. A mathematical study of human intracranial hydrodynamics. Part 1--The cerebrospinal fluid pulse pressure. Ann Biomed Eng 1988, 16, 379–401. [CrossRef]

- Salmon, J.H.; Timperman, A.L. Effect of intracranial hypotension on cerebral blood flow. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1971, 34, 687–692. [CrossRef]

- Cirovic, S.; Walsh, C.; Fraser, W.D. Mathematical study of the role of non-linear venous compliance in the cranial volume-pressure test. Med Biol Eng Comput 2003, 41, 579–588. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, I.H.; Rowan, J.O. Raised intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow. 3. Venous outflow tract pressures and vascular resistances in experimental intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1974, 37, 392–402. [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Liu, P.; Kim, T.; Donahue, M.; Rane, S.; Chen, J.J.; Qin, Q.; Kim, S.G. MRI techniques to measure arterial and venous cerebral blood volume. Neuroimage 2019, 187, 17–31. [CrossRef]

- Menéndez González, M. CNS Compartments: The Anatomy and Physiology of the Cerebrospinal Fluid. In Liquorpheresis: Cerebrospinal Fluid Filtration to Treat CNS Conditions, Menéndez González, M., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 1–19.

- Albeck, M.J.; Skak, C.; Nielsen, P.R.; Olsen, K.S.; Borgesen, S.E.; Gjerris, F. Age dependency of resistance to cerebrospinal fluid outflow. J Neurosurg 1998, 89, 275–278. [CrossRef]

- Ekstedt, J. CSF hydrodynamic studies in man. 2 . Normal hydrodynamic variables related to CSF pressure and flow. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1978, 41, 345–353. [CrossRef]

- Claassen, J.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Panerai, R.B.; Faraci, F.M. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol Rev 2021, 101, 1487–1559. [CrossRef]

- Duelli, R.; Kuschinsky, W. Changes in brain capillary diameter during hypocapnia and hypercapnia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1993, 13, 1025–1028. [CrossRef]

- R, D.E.S.; Ranieri, A.; Bonavita, V. Starling resistors, autoregulation of cerebral perfusion and the pathogenesis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Panminerva Med 2017, 59, 76–89. [CrossRef]

- Momjian, S.; Owler, B.K.; Czosnyka, Z.; Czosnyka, M.; Pena, A.; Pickard, J.D. Pattern of white matter regional cerebral blood flow and autoregulation in normal pressure hydrocephalus. Brain 2004, 127, 965–972. [CrossRef]

- Owler, B.K.; Pickard, J.D. Normal pressure hydrocephalus and cerebral blood flow: a review. Acta Neurol Scand 2001, 104, 325–342. [CrossRef]

- Tuniz, F.; Vescovi, M.C.; Bagatto, D.; Drigo, D.; De Colle, M.C.; Maieron, M.; Skrap, M. The role of perfusion and diffusion MRI in the assessment of patients affected by probable idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. A cohort-prospective preliminary study. Fluids Barriers CNS 2017, 14, 24. [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, N.; Andersson, K.; Marmarou, A.; Malm, J.; Eklund, A. Comparison between 3 infusion methods to measure cerebrospinal fluid outflow conductance. J Neurosurg 2010, 113, 1294–1303. [CrossRef]

- Griffith, B.; Capobres, T.; Patel, S.C.; Marin, H.; Katramados, A.; Poisson, L.M. CSF Pressure Change in Relation to Opening Pressure and CSF Volume Removed. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018, 39, 1185–1190. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.H.; Wertman, N. Modulation of CSF production by alterations in cerebral perfusion pressure. Arch Neurol 1978, 35, 527–529. [CrossRef]

- Cserr, H.F. Physiology of the choroid plexus. Physiol Rev 1971, 51, 273–311. [CrossRef]

- Kimelberg, H.K. Water homeostasis in the brain: basic concepts. Neuroscience 2004, 129, 851–860. [CrossRef]

- Brean, A.; Eide, P.K.; Stubhaug, A. Comparison of intracranial pressure measured simultaneously within the brain parenchyma and cerebral ventricles. J Clin Monit Comput 2006, 20, 411–414. [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, L.O.; Olivecrona, M. Clinical experience with the intraparenchymal intracranial pressure monitoring Codman MicroSensor system. Neurosurgery 2005, 56, 693–698; discussion 693-698. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Hua, Y.; Xi, G.; Keep, R.F. Mechanisms of cerebrospinal fluid and brain interstitial fluid production. Neurobiol Dis 2023, 183, 106159. [CrossRef]

- Castejon, O.J. Submicroscopic pathology of human and experimental hydrocephalic cerebral cortex. Folia Neuropathol 2010, 48, 159–174.

- Eide, P.K.; Hansson, H.A. Blood-brain barrier leakage of blood proteins in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Brain Res 2020, 1727, 146547. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.J.; Kolecka, M.; Kirberger, R.; Hartmann, A. Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast Perfusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging Demonstrates Reduced Periventricular Cerebral Blood Flow in Dogs with Ventriculomegaly. Front Vet Sci 2017, 4, 137. [CrossRef]

- Good, C.D.; Johnsrude, I.; Ashburner, J.; Henson, R.N.; Friston, K.J.; Frackowiak, R.S. Cerebral asymmetry and the effects of sex and handedness on brain structure: a voxel-based morphometric analysis of 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage 2001, 14, 685–700. [CrossRef]

- Muer, J.D.; Didier, K.D.; Wannebo, B.M.; Sanchez, S.; Khademi Motlagh, H.; Haley, T.L.; Carter, K.J.; Banks, N.F.; Eldridge, M.W.; Serlin, R.C.; et al. Sex differences in gray matter, white matter, and regional brain perfusion in young, healthy adults. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2024, 327, H847–H858. [CrossRef]

- Ohmichi, T.; Kondo, M.; Itsukage, M.; Koizumi, H.; Matsushima, S.; Kuriyama, N.; Ishii, K.; Mori, E.; Yamada, K.; Mizuno, T.; et al. Usefulness of the convexity apparent hyperperfusion sign in 123I-iodoamphetamine brain perfusion SPECT for the diagnosis of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg 2019, 130, 398–405. [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, E.K.; Ringstad, G.; Mardal, K.A.; Eide, P.K. Cerebrospinal fluid volumetric net flow rate and direction in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neuroimage Clin 2018, 20, 731–741. [CrossRef]

- Rau, A.; Reisert, M.; Kellner, E.; Hosp, J.A.; Urbach, H.; Demerath, T. Increased interstitial fluid in periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensities in patients with suspected idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 19552. [CrossRef]

- Shoesmith, C.L.; Buist, R.; Del Bigio, M.R. Magnetic resonance imaging study of extracellular fluid tracer movement in brains of immature rats with hydrocephalus. Neurol Res 2000, 22, 111–116. [CrossRef]

- Nedergaard, M. Neuroscience. Garbage truck of the brain. Science 2013, 340, 1529–1530. [CrossRef]

- Eide, P.K.; Pripp, A.H.; Ringstad, G. Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers of cerebrospinal fluid tracer dynamics in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Brain Commun 2020, 2, fcaa187. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. Syringomyelia Is Associated with a Reduction in Spinal Canal Compliance, Venous Outflow Dilatation and Glymphatic Fluid Obstruction. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. The dilated cortical veins found in multiple sclerosis can explain the reduction in glymphatic flow. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2024, 81, 105136. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, G.A.; Bateman, A.R. The dilated veins surrounding the cord in multiple sclerosis suggest elevated pressure and obstruction of the glymphatic system. Neuroimage 2024, 286, 120517. [CrossRef]

- Bonney, P.A.; Briggs, R.G.; Wu, K.; Choi, W.; Khahera, A.; Ojogho, B.; Shao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Borzage, M.; Wang, D.J.J.; et al. Pathophysiological Mechanisms Underlying Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus: A Review of Recent Insights. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 866313. [CrossRef]

- Tariq, K.; Toma, A.; Khawari, S.; Amarouche, M.; Elborady, M.A.; Thorne, L. Normal cerebrospinal fluid production rate in normal pressure hydrocephalus patients post lumbar infusion test. In Proceedings of the Hydrocephalus 2024, Nagoya, Japan, 13-16 September, 2024.

- Kalani, M.Y.; Filippidis, A.S.; Rekate, H.L. Hydrocephalus and aquaporins: the role of aquaporin-1. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2012, 113, 51–54. [CrossRef]

- Ozu, M.; Dorr, R.A.; Gutierrez, F.; Politi, M.T.; Toriano, R. Human AQP1 is a constitutively open channel that closes by a membrane-tension-mediated mechanism. Biophys J 2013, 104, 85–95. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).