Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

A novel hierarchical porous biomorphic ZnO/SnO has been facilely synthesized in one step using bagasse as bio-template. The structural features of the ZnO/SnO2 n–n heterostructures were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscope (SEM), transmission electron microscope (TEM), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The results revealed that the as-prepared ZnO/SnO2 retained the original pore morphology of the bagasse material, and the ZnO/SnO2 was demonstrated with higher sensing performance as compared with the pure SnO2. Particularly, when molar ratio SnO2:ZnO=1:1, the sensor displayed the highest response, showing an excellent response value of 37 under 100 ppm methanol at 340℃. Meanwhile, ZnO/SnO2 composite exhibit good gas selectivity and stability to methanol, which can mainly be attributed to the formation of n-n junctions between SnO2 and ZnO, high capability of absorbed oxygen species of the ZnO/SnO2 composite.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of ZnO/SnO2

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Measurement of Gas Sensing Properties

3. Results

3.1. Characterization

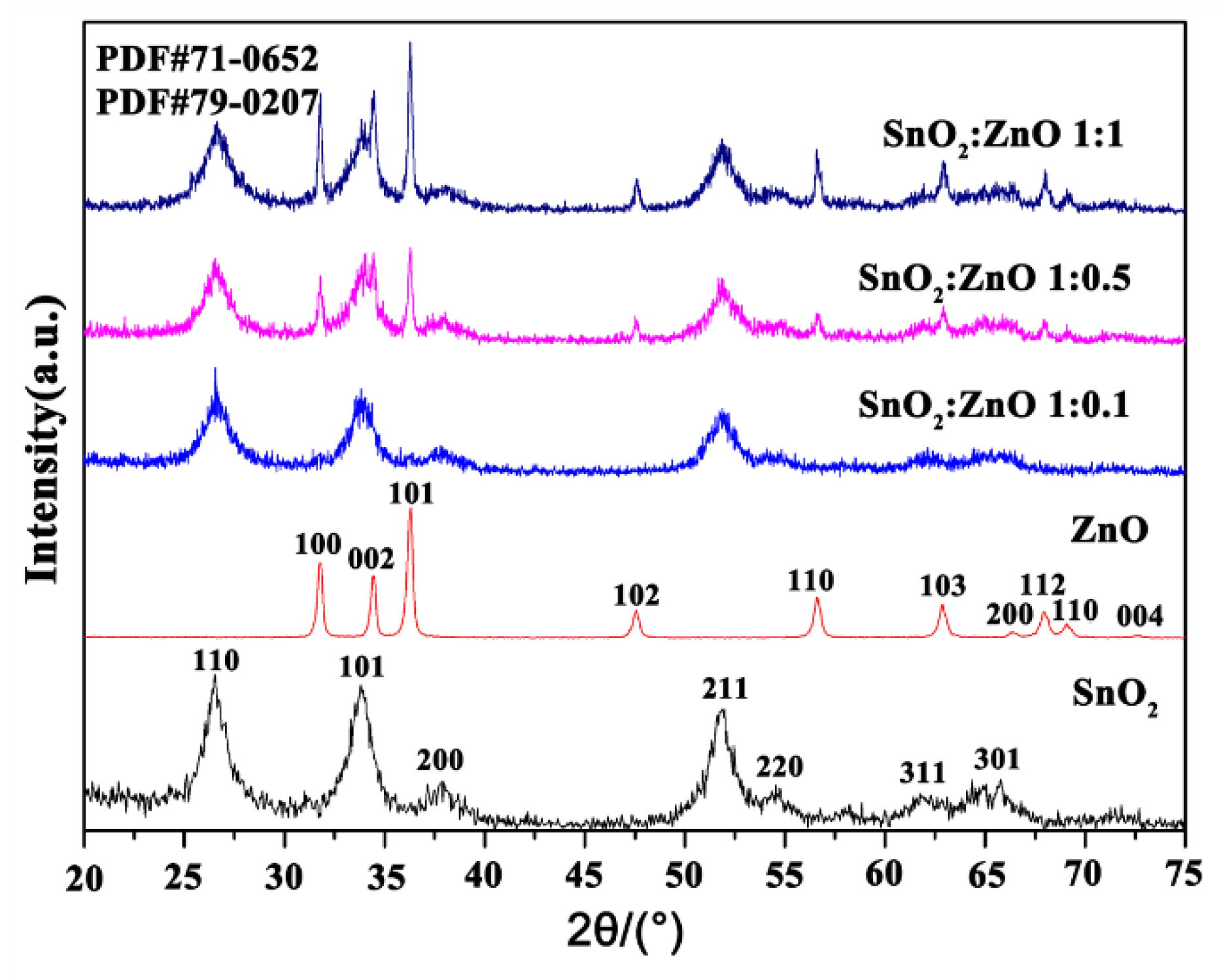

3.3.1. Structural Analysis

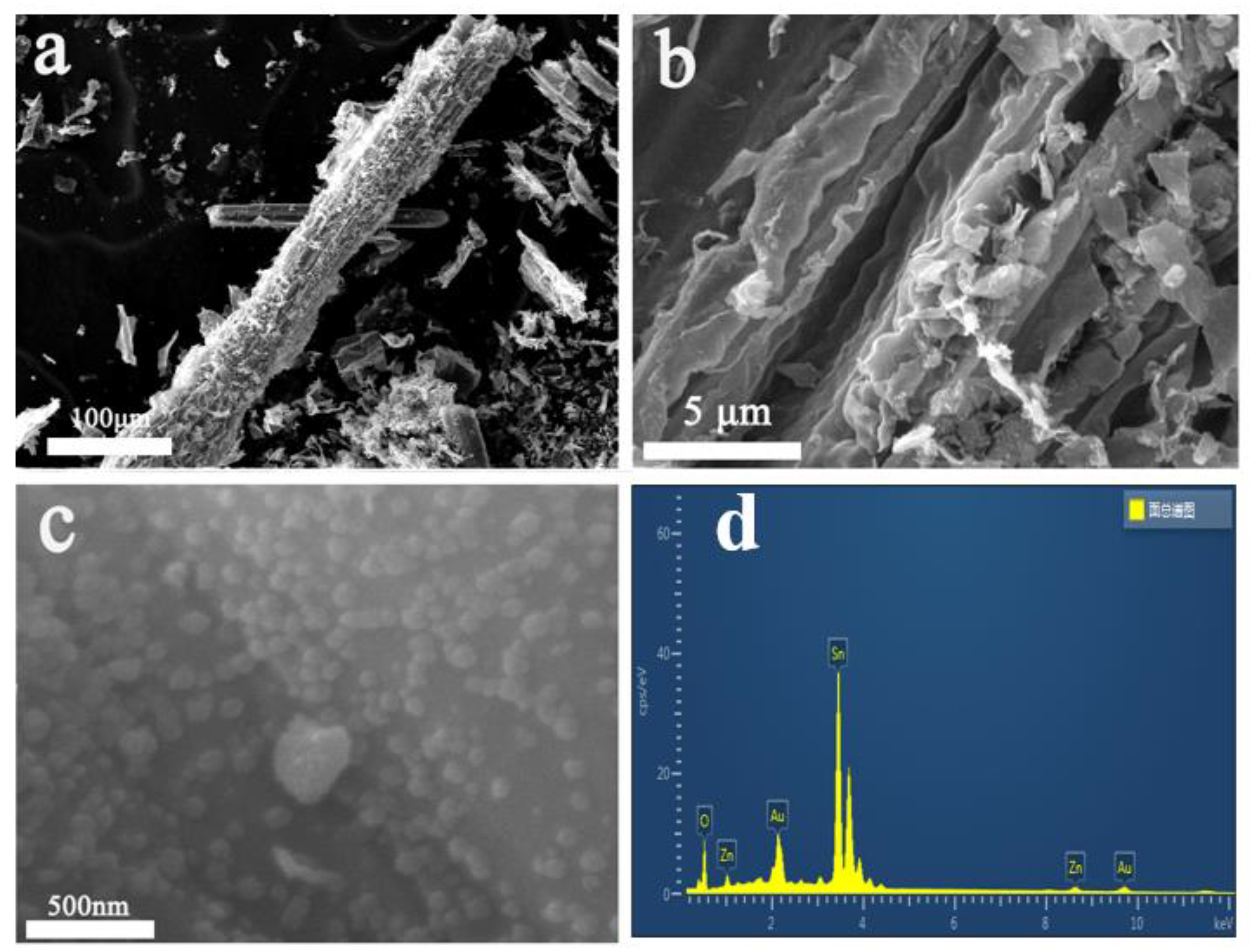

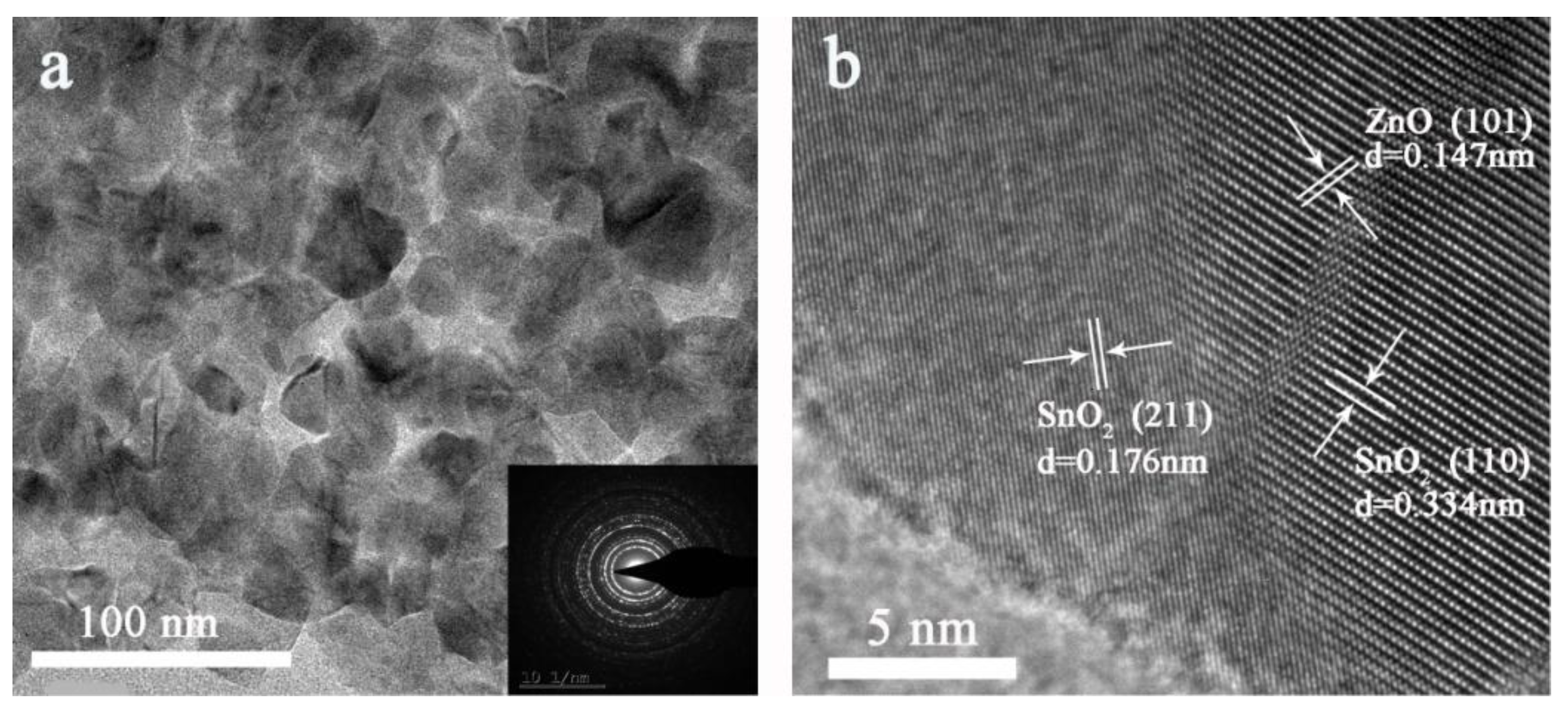

3.3.2. Morphological Analysis

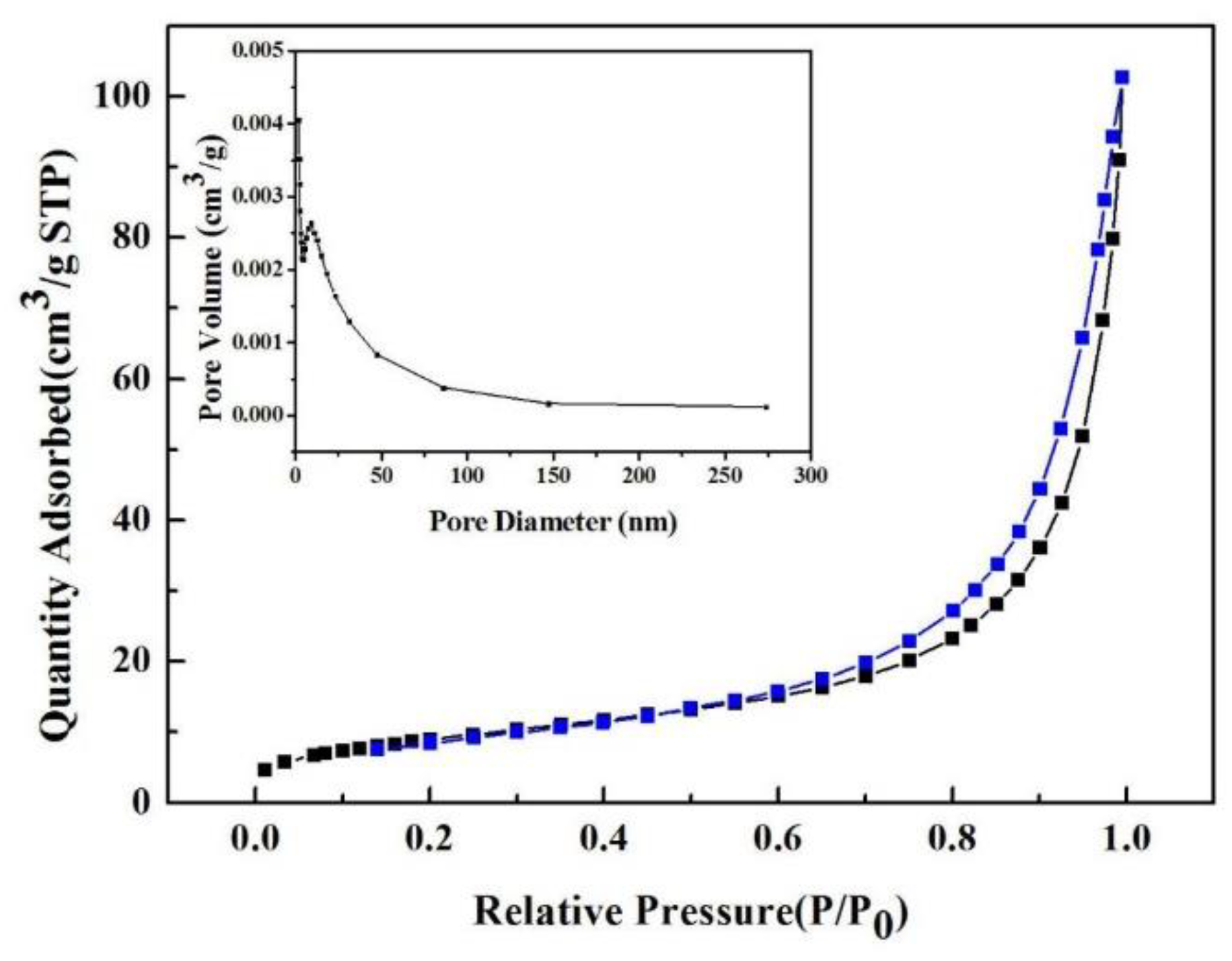

3.3.3. BET Analysis

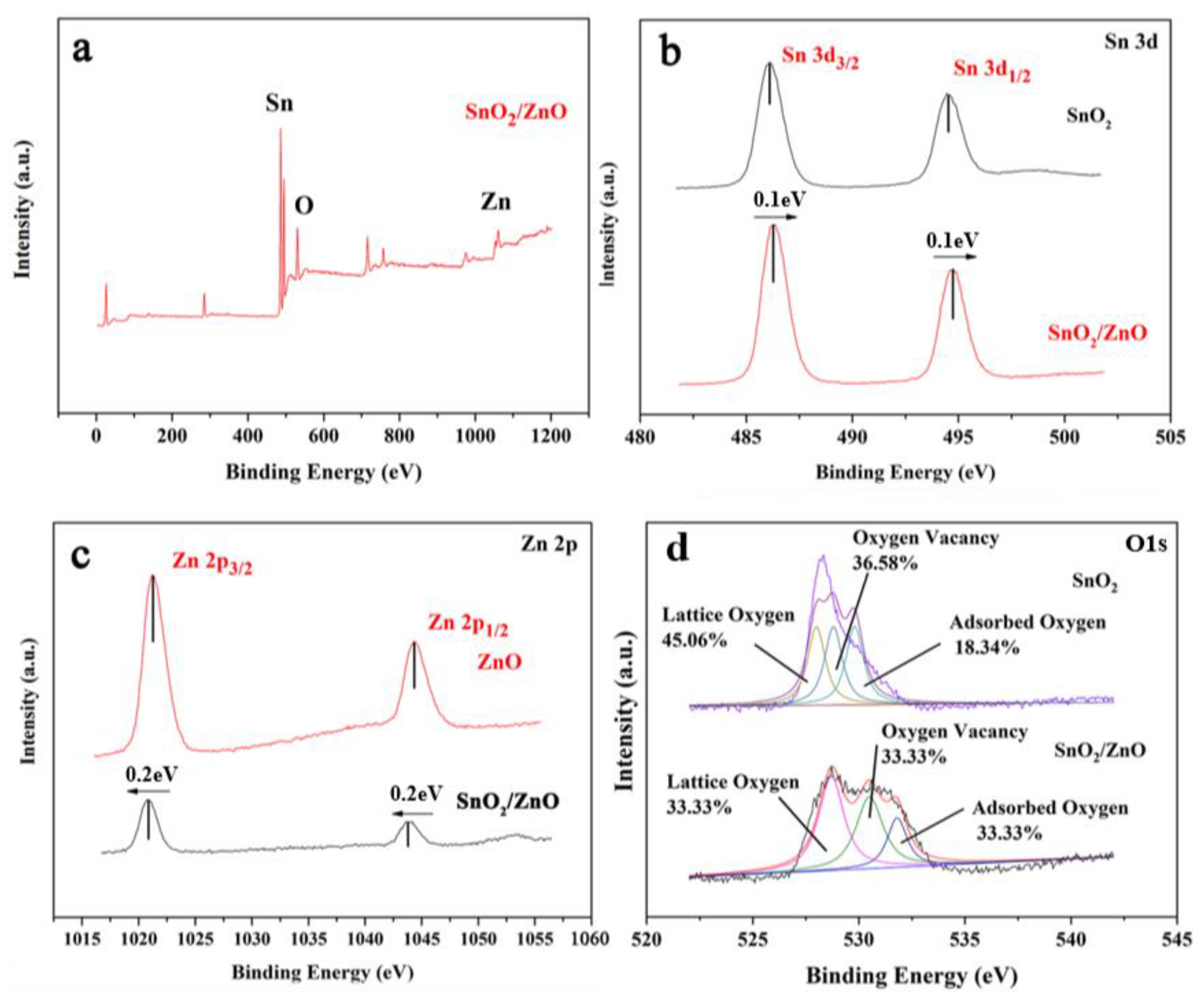

3.3.4. Composition Analysis

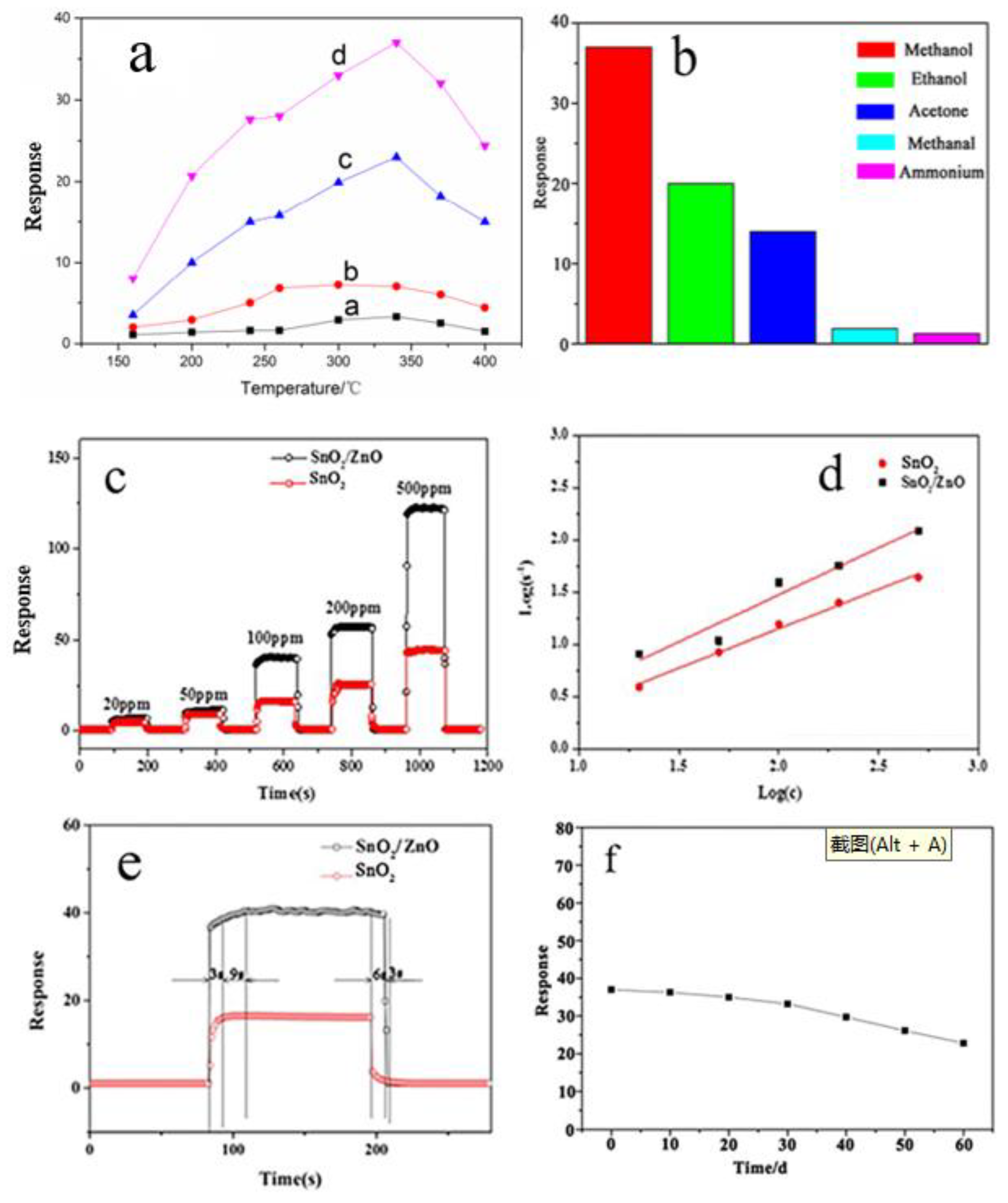

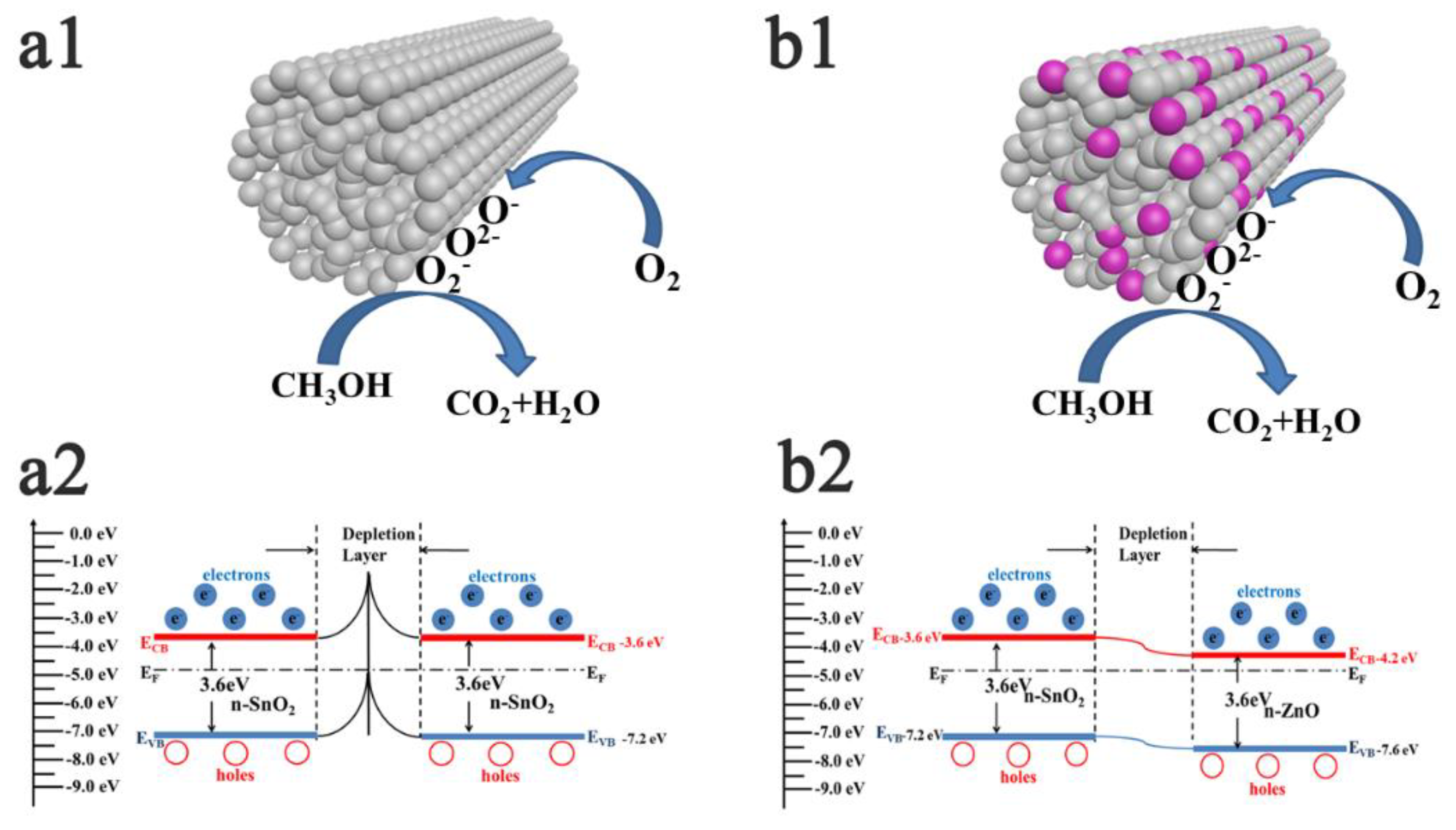

3.2. Gas Sensing Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majhi, S.M.; Mirzaei, A.; Navale, S.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Boosting the sensing properties of resistive-based gas sensors by irradiation techniques: A review. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 4728–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Zeng, W.; Li, Y. Gas sensing mechanisms of metal oxide semiconductors: A focus review. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 22664–22684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genner, A.; Martín-Mateos, P.; Moser, H.; Lendl, B. A Quantum Cascade Laser-Based Multi-Gas Sensor for Ambient Air Monitoring. Sensors 2020, 20, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftyurek, E.; Li, Z.; Schierbaum, K. Adsorbed Oxygen Ions and Oxygen Vacancies: Their Concentration and Distribution in Metal Oxide Chemical Sensors and Influencing Role in Sensitivity and Sensing Mechanisms. Sensors 2022, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuoc, P.H.; Hung, C.M.; Van Toan, N.; Van Duy, N.; Hoa, N.D.; Van Hieu, N. One-step fabrication of SnO2 porous nanofiber gas sensors for sub-ppm H2S detection. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2020, 303, 111722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Zeng, W.; Li, Y. Gas sensing mechanisms of metal oxide semiconductors: A focus review. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 22664–22684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhao, R.; Sun, B.; Nie, G.; Ji, H.; Lei, J.; Wang, C. Highly sensitive acetone sensor based on Eu-doped SnO2 electrospun nanoffbers. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 15881–15888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Feng, G.; Sun, T.; Xiao, J.; Guo, W.; Song, C. Excellent gas-sensitive properties towards acetone of In2O3 nanowires prepared by electrospinning. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 45, 100508. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.; Srivastava, A.K.; Basavaraja, B.M.; Sharma, A. “Nano-on-Micro” approach enables synthesis of ZnO nano-cactus for gas sensing applications. Sens. Int. 2021, 2, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.-S.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Z. Chemiresistive sensor based on hollow Fe2O3 octahedrons incorporated into porous In2O3 nanofibers for enhanced sensing performance and recognition toward triethylamine. Sens.Actuators B Chem. 2023, 393, 134129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, J. Advancements in improving selectivity of metal oxide semiconductor gas sensors opening new perspectives for their application in food industry. Sensors 2023, 23, 9548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. , Qua Y., Chen H., Lin Z., Dai K. Highly selective n-butanol gas sensor based on mesoporous SnO2 prepared with hydrothermal treatment. Sensors and Actuators B 2014, 201, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, J.-Y.; Mirzaei, A.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Enhancement of CO and NO2 sensing in n-SnO2-p-Cu2O core-shell nanoffbers by shell optimization. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 376, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oztel, S.; Kaya, S.; Budak, E.; Yilmaz, E. Influences of Platinum Doping Concentrations and Operation Temperatures on Oxygen Sensitivity of Pt/SnO2/Pt Resistive Gas Sensors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 14813–14821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulemo, P.M.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, I.-D. Controlled synthesis of electrospun hollow Pt-loaded SnO2 microbelts for acetone sensing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 344, 130208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Luo, L.; Zhu, X.; Xi, Y.; Yang, Z.; Han, N.; Wang, F.; et al. One-step electrospun SnO2/MOx heterostructured nanomaterials for highly selective gas sensor array integration. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 283, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.P. , Wang Y.Z., Wang L.Q., Tian H.W., Zeng Y., Controllable assembly of sandwich-structured SnO2/Fe2O3 multilayer nanosheets for high sensitive acetone detection, Mater. Lett. 2018, 221, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Yu, F.; Zhang, L.; Wang,W. ; Chen, L.; Li, Y. Review of ZnO-Based Nanomaterials in Gas Sensors. Solid State Ion. 2021, 360, 115544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chu, S.; Ma, Q.; Li, H.; Che, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Yang, P. Multilevel Effective Heterojunctions Based on SnO2/ZnO 1D Fibrous Hierarchical Structure with Unique Interface Electronic Effects. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 31551–31561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, K.; Xiao, C.; Jia, L. Electrospun Bi-doped SnO2 porous nanosheets for highly sensitive nitric oxide detection. J.Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Wang, Y.J.; Ying, M.X.; Xu, J.Q.; Xu, L.Q.; Zhang, H.J. Copolymer-assisted fabrication of rambutan-like SnO2 hierarchical nanostructure with enhanced sensitivity for n-butanol, Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 172, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnukumara, P.; Vivekanandhana, S. ; MisraM.; Mohanty A.K. Recent advances and emerging opportunities in phytochemical synthesis of ZnO nanostructures. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 80 (2018) 143–161.

- Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, L.; Lou, Z.; Qiao, L.; Tian, H.; Zheng, W. Ultrathin nanorod-assembled SnO2 hollow cubes for high sensitive n-butanol detection. Sensors & Actuators: B. Chemical 283 (2019) 693–704.

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, F.; Liang, H.; Wang, K.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, K.; Yang, L.; Lou, X. From the surface reaction control to gas-diffusion control: the synthesis of hierarchical porous SnO2 microspheres and their gas-sensing mechanism. J. Phys.Chem. C 2015, 119, 15963–15976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, G.; Dai, H.; Chen, H.; Fu, H. Gas sensor preparation based on green biological template: A review. Sensors & Actuators: A. Physical 2024, 366, 115051. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Hu, R.; Qiao, Q.; Li, X. Synthesis and gas sensing properties of porous hierarchical SnO2 by grapefruit exocarp bio-template, Sens. Actuators B 2016, 222, 1134–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.J.; Trinh, L.T.P.; Song, Y.; Lee, Y.G.; Bae, H.J. Bioconversion of biomass waste into high value chemicals, Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 122386. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, P.; Qi, L.; You, K.; Shi, Q. Hydrothermal synthesis of hierarchical SnO2 nanostructures for improved formaldehyde gas sensing, Nanomaterials 2022,12 (2), 228.

- Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, J. A gas sensor based on Ag-modified ZnO flower-like microspheres: temperature-modulated dual selectivity to CO and CH4, Surf. Interfaces 2021, 24, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazoe, N.; Shimanoe, K. Theory of power laws for semiconductor gas sensors, Sens. Actuators, B. 2008,128 (2),566–573.

- Wei, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, J.; Lu, Z.; Xu, L.; Zeng, W. Hydrothermal Synthesis of SnO2 Nanoneedle-Anchored NiO Microsphere and its Gas Sensing Performances. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, M.; Tsubone, D.; Yanagida, H. Dependence of electrical conductivity of ZnO on degree of sintering, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1976, 59, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SnO2 | SnO2/ ZnO 1:0.1 | SnO2/ ZnO 1:0.5 | SnO2/ ZnO 1:1 | |

| BET(m2/g) | 30.51 | 33.67 | 40.44 | 70.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).