1. Introduction

In evolution, studying the heritable characteristics of the biological population is helpful to understand the diversity between species on our planet Earth [

1]. Macroevolution is expected to occur when selection acts on a trait that has a heritable basis of phenotypic variation. During the evolutionary process, speciation results in new species, and the comparison of traits (e.g. height, weight, size, ⋯ etc.) among a group of related species can be made by studying the speed of changes in their characteristics over successive generations [

2].

Although one subgroup of species evolved at a faster rate and resulted in a larger variation in the trait, the other subgroup of species evolved at a relatively lower rate and produced a moderate variation of the trait. When evolutionary processes such as natural selection (including sexual selection) and genetic drift act on this variation, certain characteristics become more common or rare within a population [

3]. For example, Darwin finches are a group of about 18 species of dull-colored passerine birds on the Galápagos islands [

4]. They are well known for their remarkable diversity in form, size, and function of the beak, which is highly adapted to different food sources [

5]. Another example is angiosperms, which survive and thrive successfully on our planet. The evolution of fruits is one of the most important characteristics, as fruits not only provide a food source for other species, but also protect seeds and contribute to seed dispersal [

6]. The survival and success of fruits require adaptation to their environment. For example, while dragon fruit (

Selenicereus) endures temperatures up to 40°C (104°F) for survival, watermelon (

Citrullus lanatus) needs temperatures higher than about 25°C (77°F) to thrive. Studying the reproducible properties by the rate of evolution to the resistance of temperature would help us shed light on the evolution of angiosperms themselves and understand their ecological implications.

The rate of evolution is a measurement of the change in an evolutionary lineage over time and can be defined as the ratio of the character displacement over a certain time interval. [

7] defined the rate of change between two samples using three quantities: the proportional difference between the sample means, the pooled standard deviation of the samples, and the time interval between the samples. For example, suppose that a character has been measured twice,

and

, where

and

are expressed as the time before the present in millions of years. The time interval between the two samples can be written as

, which is 1 million years if

and

. The average value of the character is defined as

in the previous sample and

in the later sample. Let

be the natural logarithm taking into account

and

. Then the evolutionary rate (

) can be defined as in Eq. (

1)

Next, multiplying the time difference

on both sides of Eq. (

1) produces the character difference within a time unit

Conceptually consider that the character change occurred in infinitesimal time and denote the character displacement by

, then we have the differential equation

. Given

, the solution is

which shows that

increased with time

t. Unfortunately, this may not be an appropriate model for describing character change in the evolutionary perspective. Instead, one may consider that the variation of the character change adopts a certain dynamic. For example, if one considers that the variation of the character change is proportional to time, then a stochastic variable

can be introduced, where

is a Wiener process with independent Gaussian distributed increment and

is a normal distributed random variable with mean 0 and variance

(i.e.

). Thus, the displacement of the continuous trait variable

(

) solves stochastic differential equation shown in Eq. (

2)

Given

, integrate both sides of Eq. (

2), one has

where

, and

.

Given the initial value

, Eq. (

3) describes the dynamic of the trait variable

at time

t pending the rate parameter

.

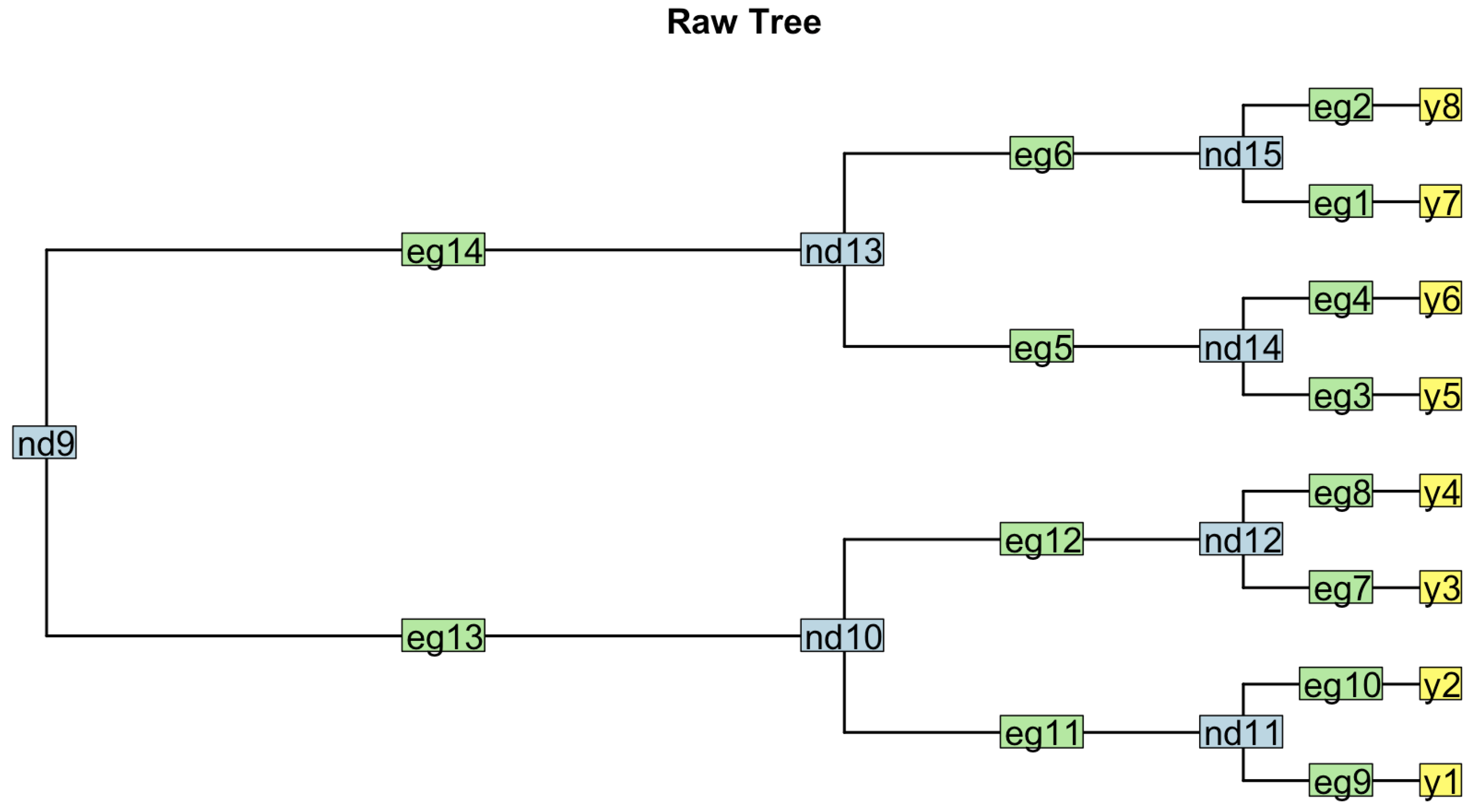

Figure 1 presents one hundred trajectories generated using rates

(bottom left) and

(bottom right), respectively. It can be seen straightforwardly that while a smaller rate (

) yields a narrower range of character value, the larger rate (

) yields a wider range of character value.

For a group of

n related species, denote

as the trait variable for the

ith species. Then we can apply the Brownian motion with the rate parameter to explore the dynamic of the trait along the evolutionary history using a phylgoenetic tree

that represents the relatedness between species. In particular, the estimation of the evolution rate

can be performed using comparative phylogenetic methods (PCM) [

8,

9,

10].

There are models created on the basis of Eq. (

3) via considering the constant-rates BM model may not be well addressed for the evolution in many scenarios [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Those models come with the assumption that the evolution of a species changes over time, the rates of evolution can be modeled as either constants or stochastic variables along times (branch lengths). The trait variable

adopts the following dynamics.

where

can be constant (i.e.

) [

16], piecewise constant (i.e.

where

and

are the successive time regimes) [

11] or a random variable modeled by another pertinent process (i.e.

where

is a distribution function for the stochastic variable) [

17,

18].

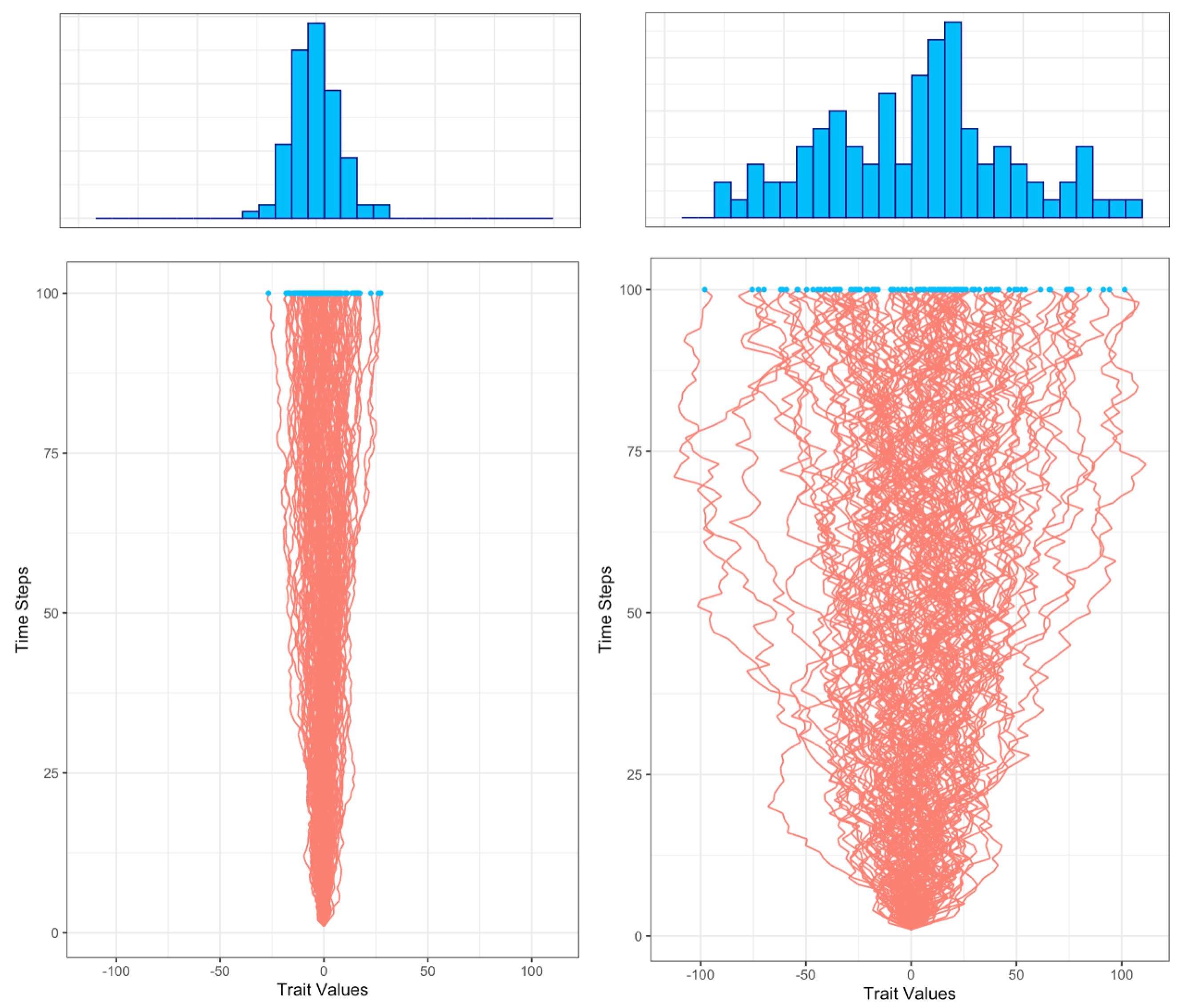

A hypothetical tree of four species

and the corresponding simulation of the trajectories

s using Brownian motion along a rooted phylogenetic tree under two different rates is shown in

Figure 2.

Those models have been broadly applied in many studies. For example, in the evolution of the morphology of the world’s largest flowers (

Raffkesianeae: up to 1 meters in diameter), [

19] found that the enormous flowers evolved from ancestors with tiny flowers. In the study of the evolution of the size of the plant genome, [

20] found that the woody lineages had a stochastic motion rate that was nearly five times slower than the rate of the herbaceous lineages. Although the existing framework has produced rate models, none consider a scenario in which the rate is treated as a time-correlated stochastic variable, which could potentially enhance the study of rate evolution. This highlights the need for our work to apply a time series model [

21,

22]. Specifically, this approach aims to answer key questions: Are the evolutionary rates of biological traits statistically independent, or are they believed to be phylogenetically serially autocorrelated ?

Note that in modeling the rate of evolution, it is essential to consider its dynamic nature, as the rate can fluctuate, increase, or decrease over time [

18,

23], rather than a constant. Consider that the implementation of the time-correlated rate evolution

could possibly provide an alternative to reveal embedded information about species evolution, in this work we intend to expand the model

in Eq. (

4) within the framework of correlated rate evolution (

for

where

is a parameter vector) to model the trait evolution for phylogenetic comparative analysis. In particular, we use the autoregressive moving average (ARMA) time series model that has been widely applied in econometrics to model the rate parameter [

24,

25]. The description of the methods can be found in

Section 2. The simulations are detailed in

Section 3. Empirical analyzes are presented in

Section 4. The discussions and conclusions are covered in

Section 5.

3. Simulation

We assess the performance of the model using simulation. Four types of trees are used for the assessment: star tree, balanced tree, left tree, coalescent tree, and birth-and-death tree, each of size . The initial samples are drawn from an independent normal distribution. The initial estimate for by applying the formula in Eq. (16) at the root is estimated by the Brownian motion model using the R package geiger. For each type of tree, for each data set and for each prior set, a million replicates of the sample will be generated to assess the posterior sample distribution.

Let the tree have m branches, with each branch representing a transition between an ancestral node and a descendant node . The tree is traversed in postorder (from root to tips), and the trait values for each node are computed based on the following AR(1) process.

For each branch, the evolutionary rate at the descendant node

is determined by the rate at its ancestor

, with some noise (innovation) added. The autoregressive equation is shown in Eq. (19)

Initially, the rate value at the root node is set to zero: .

After simulating the rates using Eq. (19) for all nodes in the tree, the final trait values at the tree tips (taxa) are computed by accumulating the rates along the path from the root to each tip.

Let

denote the set of nodes from the root to tip

j, and

denote the branch length leading to node

. The trait value at each tip

j is:

where

is the final accumulated trait value at tip

j.

The final output consists of two arrays: (1) the array of simulated evolutionary rates for each node,

, and (2) the trait values at the tree tips,

summarized by the following equations Eq. (21)

This simulation captures the evolutionary rate changes along a phylogeny under an AR(1) model, accounting for both ancestral states and random innovation at each branch. We create a function

simulate_trait_data_given_phi which simulates the trait evolution process along a phylogenetic tree using an autoregressive process (AR(1)) for the rates of evolution. The simulation setup is shown in Algorithm 2

|

Algorithm 2: Estimating Type I Error and Power with Phylogenetic AR(1) rate Model |

- 1:

Input: tree type {balanced, coalescent, pure birth, birth death }, taxa size , simulations 1000, , , , . - 2:

Output: Type I error and power for each taxon size. - 3:

for each tree type do

- 4:

Generate tree with branch length set

- 5:

for each taxa do

- 6:

-

Initialize Type I Error

▹Estimate Type I Error

- 7:

for do

- 8:

Use Eq. (21) with to simulate trait data y

- 9:

Use Eq. ( 10) to obtain rate estimates

- 10:

Optimize the neg log likelihood in Eq. ( 15) to obtain MLE parameters . - 11:

Use Eq. (17) to test using MLE parameter, and its standard error and p value. - 12:

if then

- 13:

- 14:

end if

- 15:

end for

- 16:

-

Store for this tree and taxa size

▹Estimate Power

- 17:

for each do

- 18:

Initialize power pow

- 19:

for do

- 20:

Use Eq. (21) with to simulate trait data y

- 21:

Use Eq. ( 10) to obtain rate estimates

- 22:

Optimize the neg log likelihood in Eq. ( 15) to obtain the MLE parameters . - 23:

Use Eq. (17) to test using the MLE parameter and its standard error and p value. - 24:

if then

- 25:

pow= pow

- 26:

end if

- 27:

end for

- 28:

Store pow for this tree and taxa size - 29:

end for

- 30:

end for

- 31:

end for - 32:

Return

|

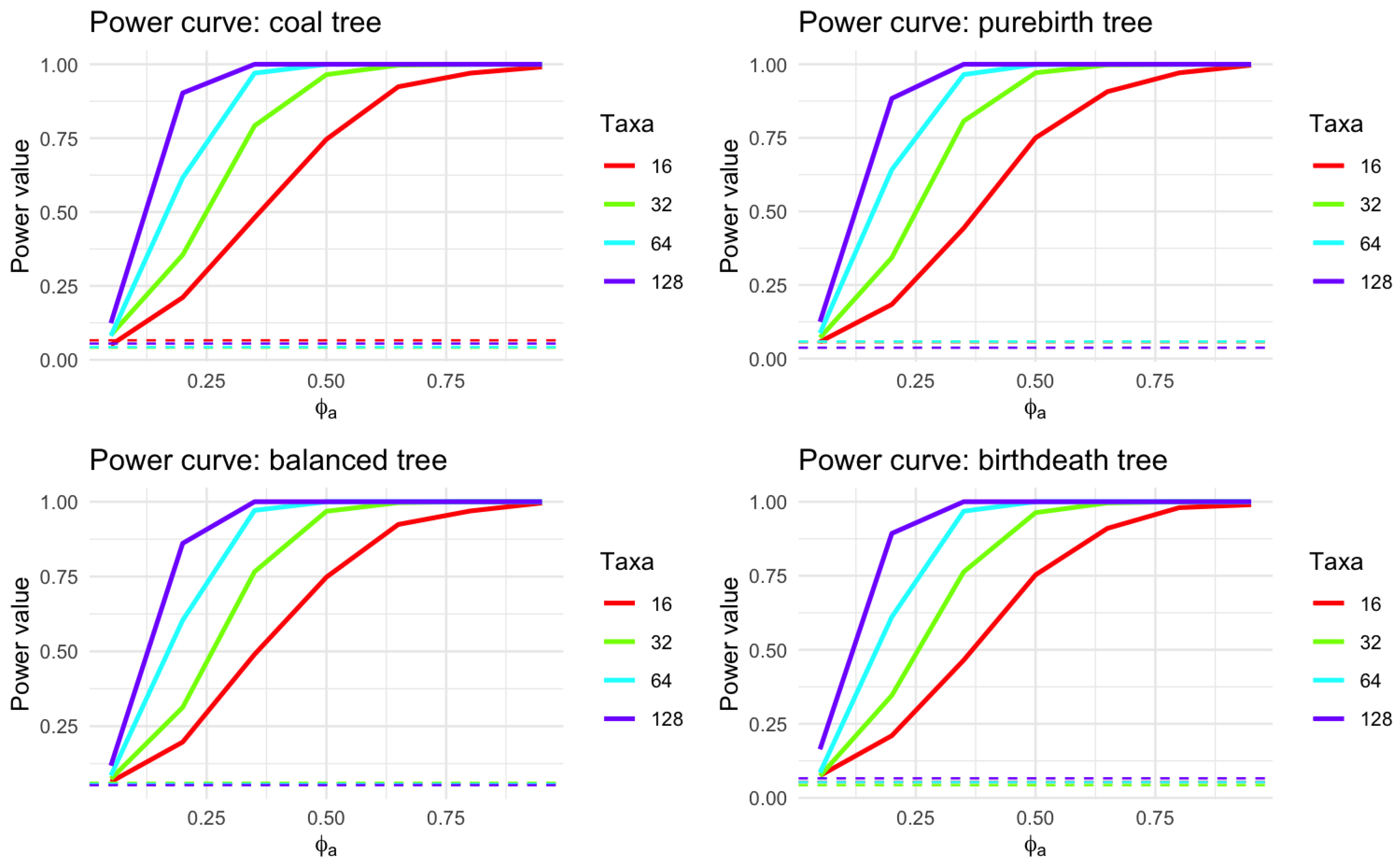

Figure 6 and

Table 1 show how the statistical power to detect an effect changes with different values of

and different taxa levels.

From

Figure 6 and

Table 1, one can envision that the power of the test changes depending on the number of taxa. Generally, as the number of taxa increases, the power also increases. Next, for all taxa levels, as

increases, the power of the test also increases. This could mean that as the parameter

increases, the ability to detect an effect or a difference becomes stronger. Third, all curves converge or come closer together at higher values of

, indicating that the power could be more consistent across different levels of taxa at these higher values. This simulation provide the evidence that our methods fit the statistical properties as expect in the performance of evaluating the statistical power and type I error.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we first assumed that species evolve along a phylogenetic tree, with time length, evolutionary rate, and trait values expressed as a linear combination. Using the given trait values and branch lengths of the phylogenetic tree, we applied ridge regression and used the R package RRphylo to estimate the evolutionary rate. Next, we modeled the evolutionary rate using the ARMA(p,q) models, fitting these models to ancestral trait values, and then applied these models to estimate present-day trait values.

In the empirical analysis, we tested whether the trait evolution of diurnal and nocturnal populations exhibited time-series correlation. In the dataset, which combined male and female primates body mass, the results showed an autoregressive effect in the separate analysis of diurnal and nocturnal populations, indicating a time-series relationship. To observe the evolutionary dynamics, the branches might have different autoregressive coefficients (). These branches can be analyzed to understand how differences between them affect the overall model. Further analysis could deepen the exploration of the effects of this statistical model in the biological context, providing a more comprehensive scientific explanation to more precisely understand and interpret evolutionary processes and phylogenetic patterns in biological systems.

Several methods exist for estimating autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) model parameters. Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) maximizes a likelihood function, assuming normally distributed errors, while Least Squares Estimation minimizes squared residuals for AR parameters but is less suited for MA parameters. The Yule-Walker Equations use sample autocorrelations to estimate AR parameters but not MA ones, whereas the Innovations Algorithm estimates both AR and MA parameters using residuals. Burg’s Method improves AR estimates by minimizing forecast errors, and Bayesian Estimation employs prior distributions and observed data, often via MCMC. The Bootstrapping Method starts by estimating the AR(1) parameters and for both time series. Then, bootstrapping is used to resample with replacement from each series multiple times. For each bootstrapped sample, calculate . Next, obtain the empirical distribution of . If 0 falls outside the 95% confidence interval, there is evidence that the two series have different AR(1) parameters. Each method has advantages depending on the time series characteristics, analysis goals, and available resources.

The proposed research on Covid evolution could be extended by investigating how regional factors such as vaccination rates, public health interventions, and population density contribute to the mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2, or by exploring correlations between mutations and viral traits like transmissibility or immune escape. For land mammals, an extension could examine how adaptability in diet breadth, climate niche, and range size has changed over evolutionary periods or incorporate phylogenetic data to study how related species respond to environmental pressures. Lastly, the study on latitude’s influence on elevation could explore how this relationship differs across biomes or is affected by human activities like deforestation and urbanization, providing a more comprehensive understanding of climate-related changes. These extensions would enhance the versatility and application of the phylogenetic autoregressive moving average regression model across various domains.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of Brownian motion using two different rates (left: , right: ). The time space is set to 100. The histograms are plotted using the endpoints of the trajectories.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of Brownian motion using two different rates (left: , right: ). The time space is set to 100. The histograms are plotted using the endpoints of the trajectories.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of trait evolution for 4 species along a rooted phylogenetic tree. Middle panel: four taxa rooted tree of 4 tips . Left panel: a set of four dependent trajectories along the tree using a single rate ( on all branches). Right panel: a set of four dependent trajectories along the tree using two rates ( on the blue branches, and on the red branches). is the root status denoted as a parameter of interest (analogous to ).

Figure 2.

Trajectories of trait evolution for 4 species along a rooted phylogenetic tree. Middle panel: four taxa rooted tree of 4 tips . Left panel: a set of four dependent trajectories along the tree using a single rate ( on all branches). Right panel: a set of four dependent trajectories along the tree using two rates ( on the blue branches, and on the red branches). is the root status denoted as a parameter of interest (analogous to ).

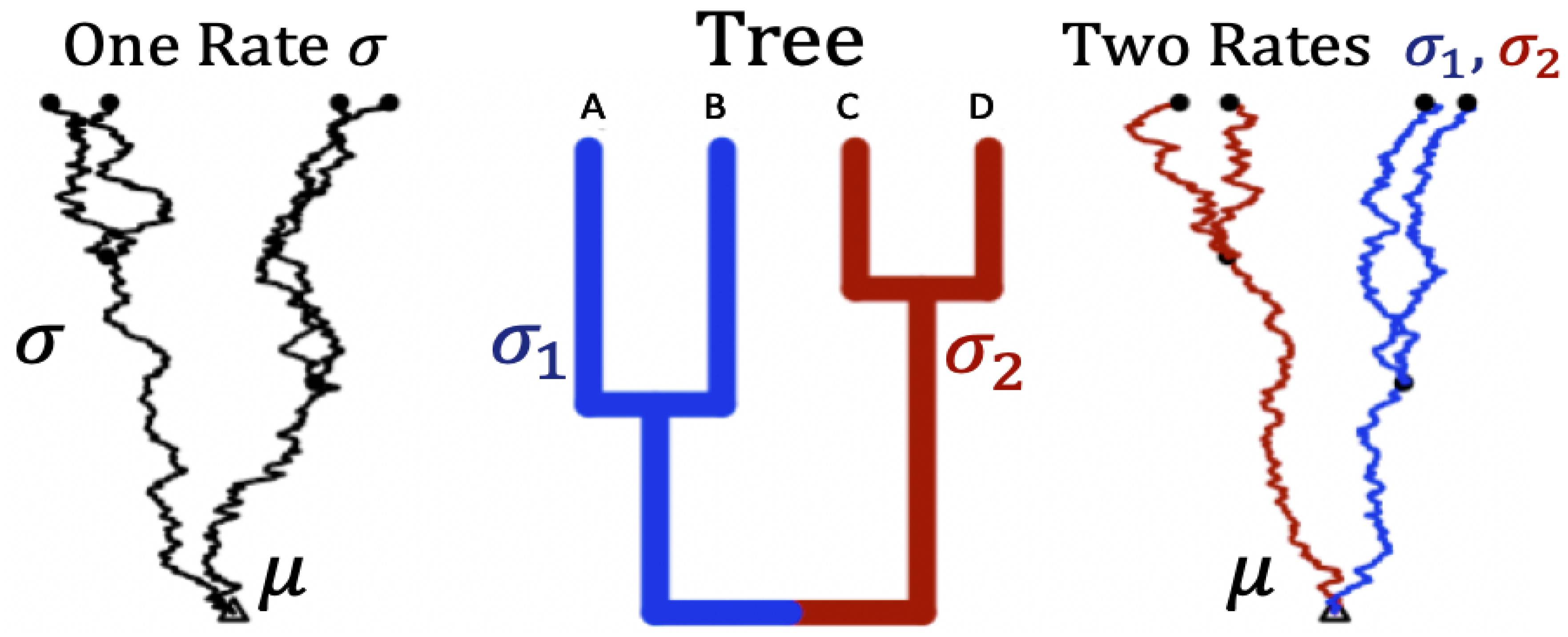

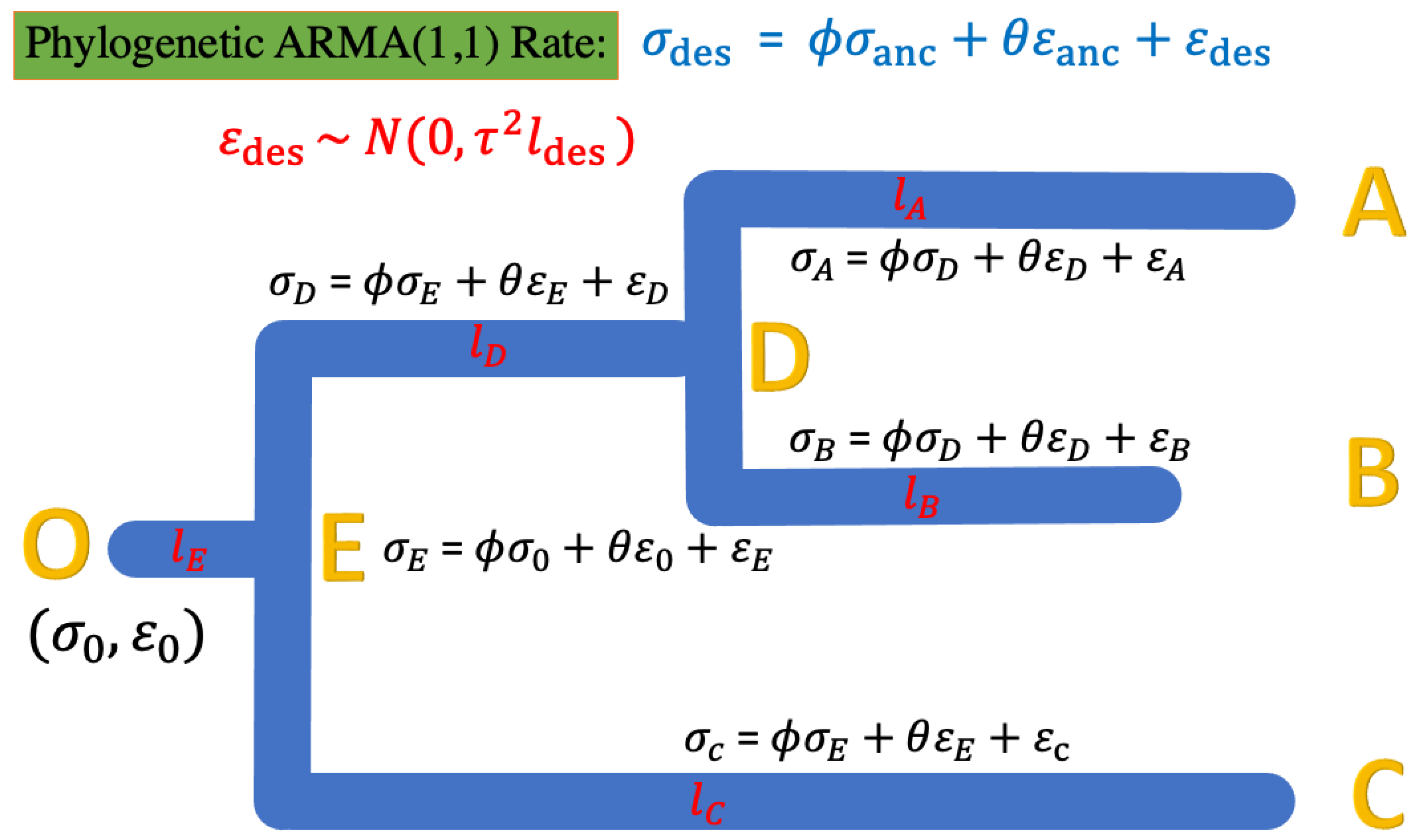

Figure 3.

A rooted phylogenetic tree of three taxa with tip nodes A, B, and C, internal nodes D and E, and root node O, where the branch lengths are , , , , and , and the rate variables are , , , , and .

Figure 3.

A rooted phylogenetic tree of three taxa with tip nodes A, B, and C, internal nodes D and E, and root node O, where the branch lengths are , , , , and , and the rate variables are , , , , and .

Figure 4.

The phylogenetic ARMA rate model for the rate of evolution along the tree. The root status O starts with , along the tree the error of the rate estimate. The ARMA rates are bond to the tree toplogy’s ancestral-descendant relationship. For instance, the rate at tip node A has the relationship with the ancestor node D of where while the rate at internal node D has the relationship with the ancestor node E of where .

Figure 4.

The phylogenetic ARMA rate model for the rate of evolution along the tree. The root status O starts with , along the tree the error of the rate estimate. The ARMA rates are bond to the tree toplogy’s ancestral-descendant relationship. For instance, the rate at tip node A has the relationship with the ancestor node D of where while the rate at internal node D has the relationship with the ancestor node E of where .

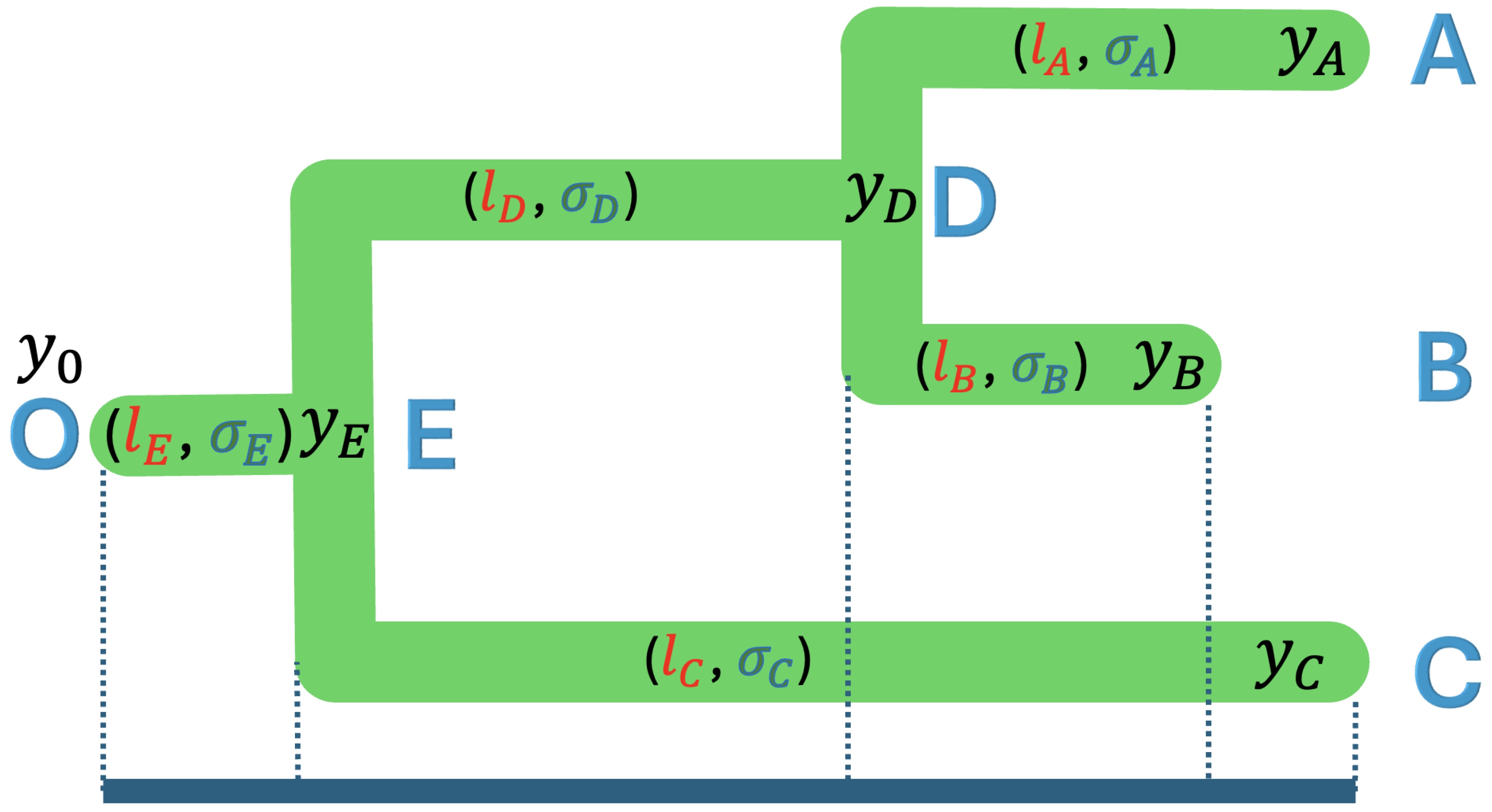

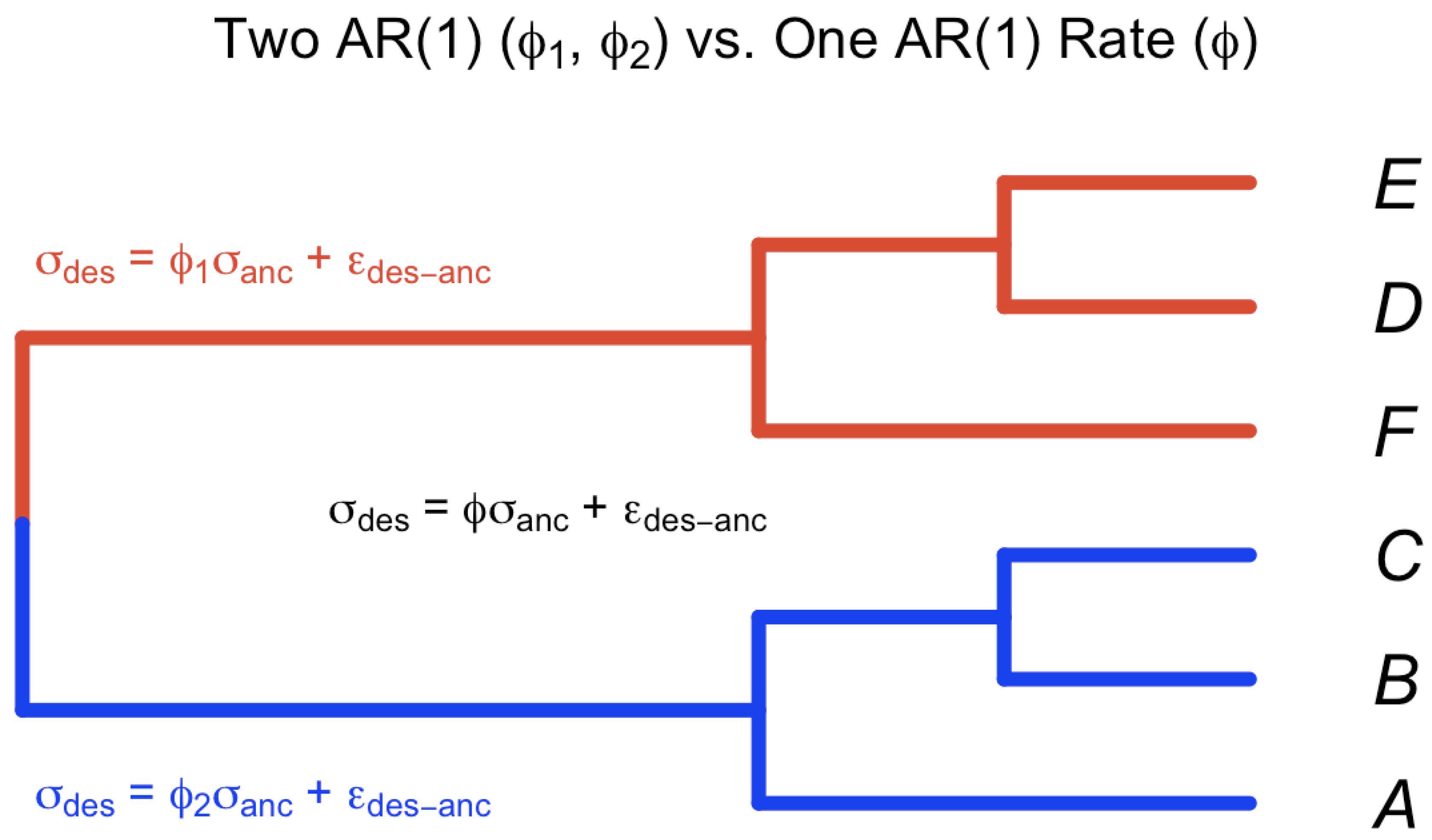

Figure 5.

Test heterogeneity rates for the trait evolution on the two sub clade of the tree. Test for two ’s () vs. one .

Figure 5.

Test heterogeneity rates for the trait evolution on the two sub clade of the tree. Test for two ’s () vs. one .

Figure 6.

Power Curve for varying Taxa levels. The horizontal axis represents an adjusted value of a parameter called , ranging from 0 to near 1. The vertical axis depicts the statistical power, indicating the probability of rejecting a null hypothesis when an alternative is true; a range from 0 suggests no detection ability, while 1 signifies certain detection. The four curves represent different Taxa counts , which could indicate distinct sample sizes or biological classifications. The horizontal lines present the type I error rate using level .

Figure 6.

Power Curve for varying Taxa levels. The horizontal axis represents an adjusted value of a parameter called , ranging from 0 to near 1. The vertical axis depicts the statistical power, indicating the probability of rejecting a null hypothesis when an alternative is true; a range from 0 suggests no detection ability, while 1 signifies certain detection. The four curves represent different Taxa counts , which could indicate distinct sample sizes or biological classifications. The horizontal lines present the type I error rate using level .

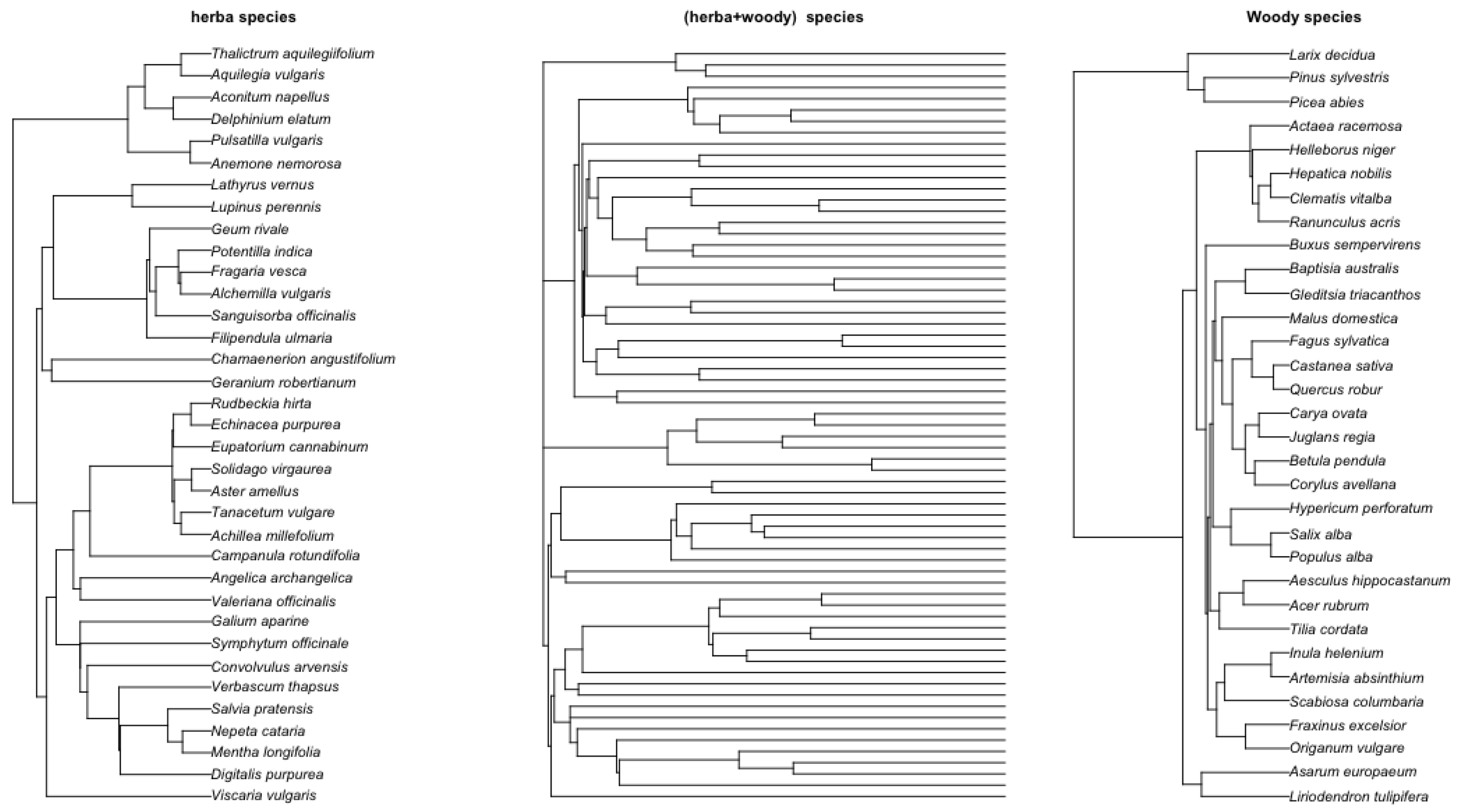

Figure 7.

Left: herbaticus tree. Right: woody specie midddle: combined herbaticus and woody species. The herbaticus and woody trees are obtained by TimeTree [

31] where species names are entered and the system generate the tree in Newick format, and the combined tree is obtained by using R

ape package function

bind.tree with applying the molecular dating with penalized likelihood approach [

32] for branch length estimation. This is done by using the R function

chronopl for taking the herbaticus tree and woody tree as input.

Figure 7.

Left: herbaticus tree. Right: woody specie midddle: combined herbaticus and woody species. The herbaticus and woody trees are obtained by TimeTree [

31] where species names are entered and the system generate the tree in Newick format, and the combined tree is obtained by using R

ape package function

bind.tree with applying the molecular dating with penalized likelihood approach [

32] for branch length estimation. This is done by using the R function

chronopl for taking the herbaticus tree and woody tree as input.

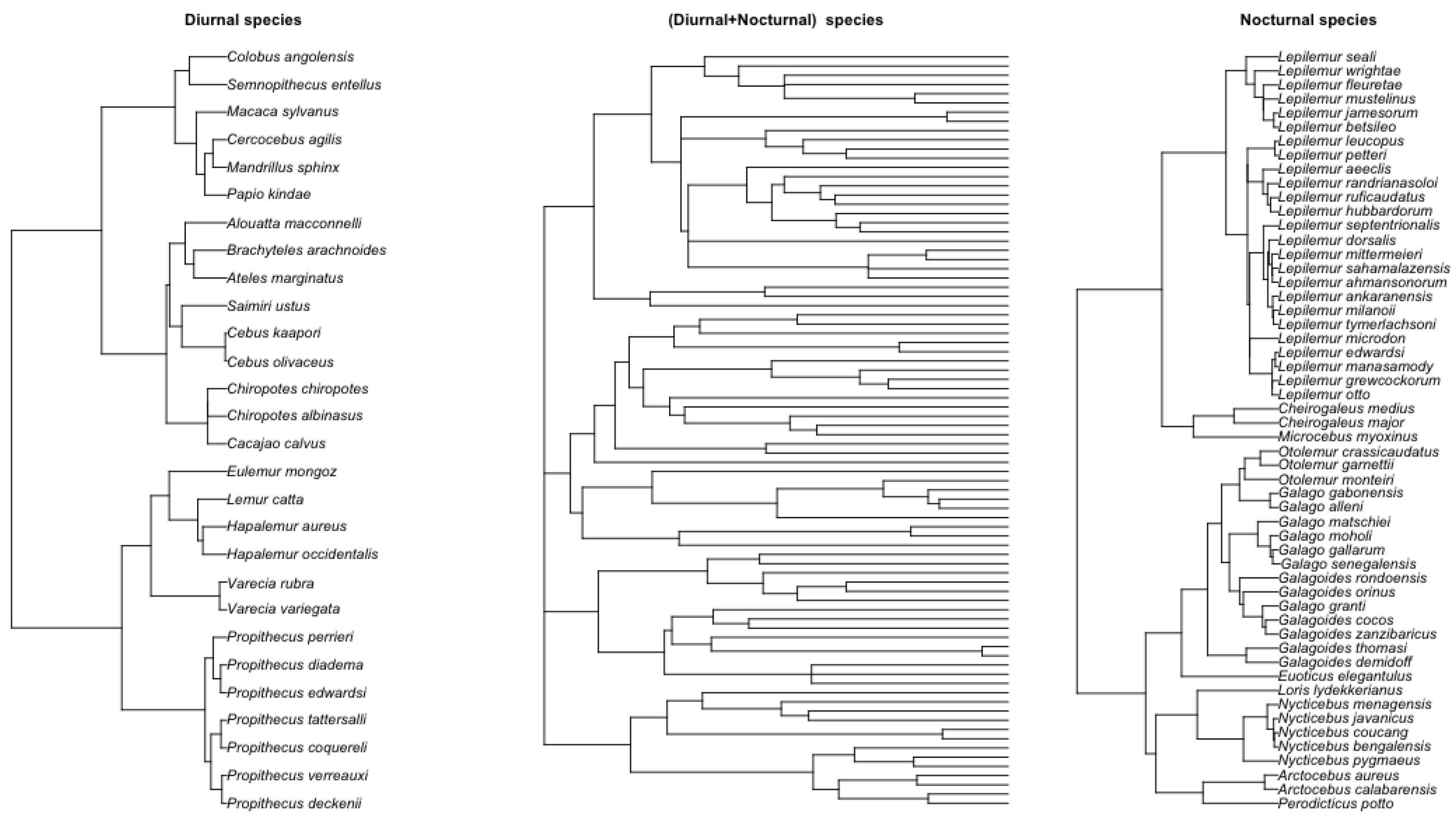

Figure 8.

Left: tree with 54 nocturnal primate. Right: tree with 28 diurnal primate. Middle: combined phylogenetic tree of 88 primate species [

33,

35].

Figure 8.

Left: tree with 54 nocturnal primate. Right: tree with 28 diurnal primate. Middle: combined phylogenetic tree of 88 primate species [

33,

35].

Table 1.

The type I error (T1 err) rate and the power of tree AR(1) rate on the null using 4 type of tree and 4 taxa size. The alternative are set to values , respectively. 1000 replicates are used and the significance level is set to .

Table 1.

The type I error (T1 err) rate and the power of tree AR(1) rate on the null using 4 type of tree and 4 taxa size. The alternative are set to values , respectively. 1000 replicates are used and the significance level is set to .

| Tree type |

Taxa |

T1 err |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Balanced |

16 |

0.066 |

0.050 |

0.211 |

0.481 |

0.746 |

0.924 |

0.970 |

0.991 |

| |

32 |

0.041 |

0.084 |

0.355 |

0.792 |

0.965 |

0.997 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| |

64 |

0.043 |

0.081 |

0.616 |

0.970 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| |

128 |

0.055 |

0.124 |

0.903 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Pure Birth |

16 |

0.056 |

0.057 |

0.184 |

0.443 |

0.750 |

0.907 |

0.971 |

0.997 |

| |

32 |

0.057 |

0.071 |

0.343 |

0.807 |

0.971 |

0.998 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| |

64 |

0.058 |

0.086 |

0.642 |

0.965 |

0.999 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| |

128 |

0.037 |

0.125 |

0.884 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Birth Death |

16 |

0.058 |

0.064 |

0.197 |

0.490 |

0.748 |

0.924 |

0.969 |

0.996 |

| |

32 |

0.061 |

0.074 |

0.313 |

0.766 |

0.968 |

0.997 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| |

64 |

0.057 |

0.085 |

0.604 |

0.971 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| |

128 |

0.053 |

0.118 |

0.861 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| Balanced |

16 |

0.054 |

0.075 |

0.210 |

0.465 |

0.753 |

0.910 |

0.980 |

0.990 |

| |

32 |

0.043 |

0.074 |

0.346 |

0.763 |

0.963 |

0.996 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| |

64 |

0.053 |

0.085 |

0.611 |

0.968 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| |

128 |

0.066 |

0.164 |

0.893 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

Table 2.

MLE parameter estimated for the combined hebaticus (35) and woody (33) 68 species.

Table 2.

MLE parameter estimated for the combined hebaticus (35) and woody (33) 68 species.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Weighted Estimate |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

Model information for the combined herbaticus and woody 88 primate species.

Table 3.

Model information for the combined herbaticus and woody 88 primate species.

| Model |

k |

|

|

w |

Rank |

| AR(2) |

3 |

|

|

|

1st

|

| AR(1) |

2 |

|

|

|

2nd

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

3 |

|

|

|

3rd

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

4 |

|

|

|

4th

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

5 |

|

|

|

5th

|

Table 4.

Herbaticus species model parameter estimates.

Table 4.

Herbaticus species model parameter estimates.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Weighted Estimate |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5.

Herbaticus species model results.

Table 5.

Herbaticus species model results.

| Model |

k |

|

|

w |

Rank |

| AR(1) |

2 |

|

|

|

1st

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

3 |

|

|

|

2nd

|

| AR(2) |

3 |

|

|

|

4th

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

4 |

|

|

|

3rd

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

5 |

|

|

|

5th

|

Table 6.

Woody species model parameter estimates.

Table 6.

Woody species model parameter estimates.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Weighted Estimate |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 7.

Woody species model results.

Table 7.

Woody species model results.

| Model |

k |

|

|

w |

Rank |

| AR(1) |

2 |

|

|

|

1st

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

3 |

|

|

|

2nd

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

5 |

|

|

|

3rd

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

4 |

|

|

|

4th

|

| AR(2) |

3 |

|

|

|

5th

|

Table 8.

, .

Table 8.

, .

| Tree case |

z-val |

p-val |

significant ? |

| combined tree |

|

|

N |

| herbaticus tree |

|

|

Y |

| woody tree |

|

|

N |

Table 9.

Testing heterogeneity rates on subclades. : , : .

Table 9.

Testing heterogeneity rates on subclades. : , : .

| Model |

_di |

_no |

_dino |

|

p-val |

Significant? |

| AR(1) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

| AR(2) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

| ARMA(1,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

| ARMA(2,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

| ARMA(2,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

Table 10.

MLE parameter estimated for the combined dirunal and nocturnal 88 primate species.

Table 10.

MLE parameter estimated for the combined dirunal and nocturnal 88 primate species.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Weighted Estimate |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 11.

Model information for the combined dirunal and nocturnal 88 primate species.

Table 11.

Model information for the combined dirunal and nocturnal 88 primate species.

| Model |

k |

|

|

w |

Rank |

| ARMA(1) |

3 |

|

|

|

1st

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

4 |

|

|

|

2nd

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

5 |

|

|

|

3rd

|

| AR(2) |

3 |

|

|

|

4th

|

| AR(1) |

2 |

|

|

|

5th

|

Table 12.

Diurnal species model parameter estimates.

Table 12.

Diurnal species model parameter estimates.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Weighted Estimate |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 13.

Diurnal species model results.

Table 13.

Diurnal species model results.

| Model |

k |

|

|

w |

Rank |

| AR(1) |

2 |

|

|

|

1st

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

3 |

|

|

|

2nd

|

| AR(2) |

3 |

|

|

|

3rd

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

4 |

|

|

|

4th

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

5 |

|

|

|

5th

|

Table 14.

Nocturnal species model parameter estimates.

Table 14.

Nocturnal species model parameter estimates.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| AR(2) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

|

|

|

|

0.004 |

| Weighted Estimate |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 15.

Nocturnal species model results.

Table 15.

Nocturnal species model results.

| Model |

k |

|

|

w |

Rank |

| AR(1) |

2 |

|

|

|

1st

|

| AR(2) |

3 |

|

|

|

2nd

|

| ARMA(1,1) |

3 |

|

|

|

3th

|

| ARMA(2,1) |

4 |

|

|

|

4th

|

| ARMA(2,2) |

5 |

|

|

|

5th

|

Table 16.

, .

Table 16.

, .

| Tree case |

z-val |

p-val |

significant ? |

| Diurnal tree |

|

|

Y |

| Nocturnal tree |

|

|

Y |

| Combined tree |

|

|

Y |

Table 17.

Testing Heterogeity Rates on subclade. : one , : .

Table 17.

Testing Heterogeity Rates on subclade. : one , : .

| Model |

_di |

_no |

_dino |

|

p-val |

Significant? |

| AR(1) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

| AR(2) |

-

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

| ARMA(1,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

| ARMA(2,1) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |

| ARMA(2,2) |

|

|

|

|

|

Y |