Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Type 1 Diabetes in Adolescents and Teens

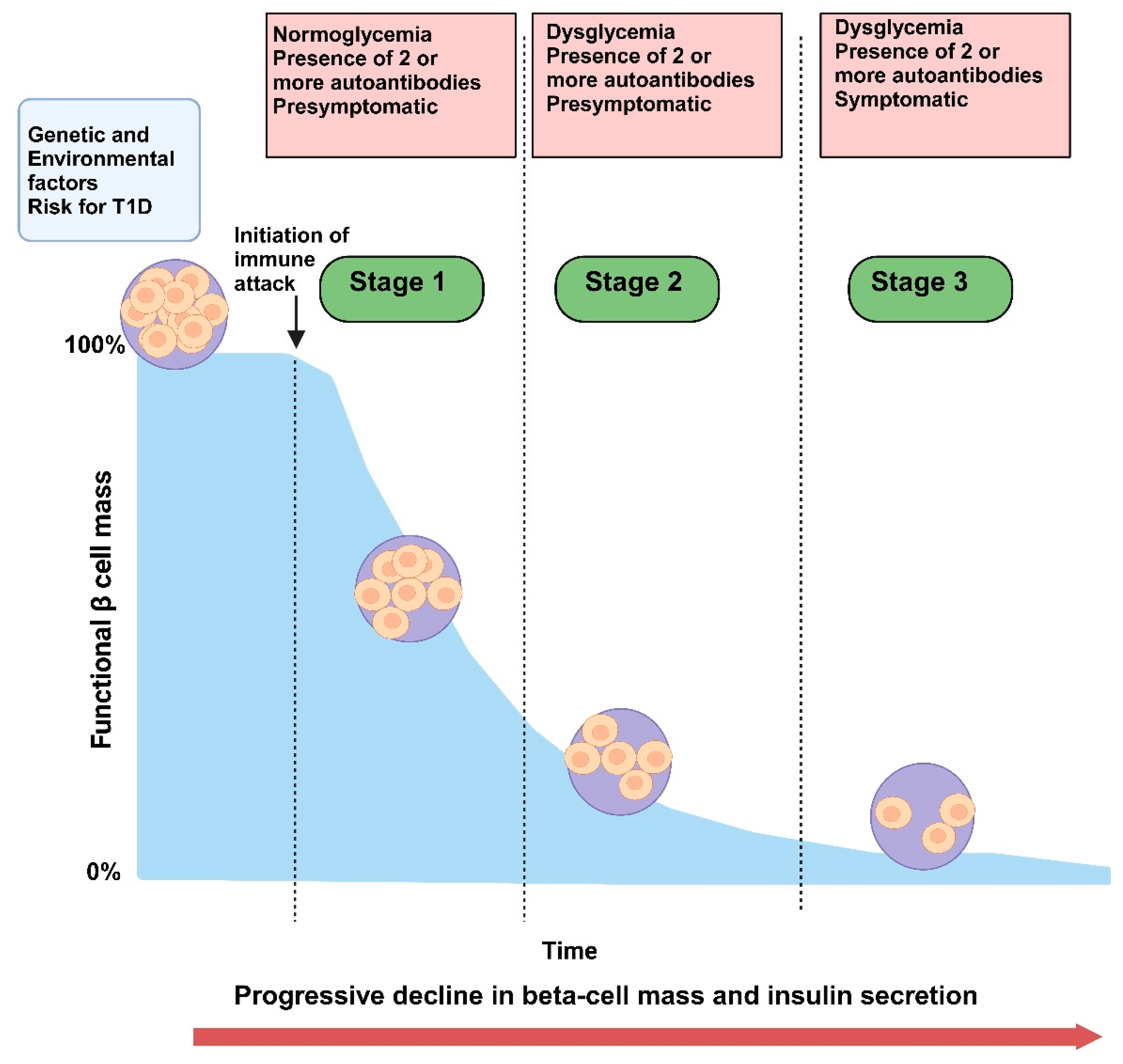

1.2. Pre-Diabetes as an Intermediary Stage Characterized by Insulin Resistance, Autoantibody Presence, and Subclinical Beta Cell Dysfunction

1.3. Importance of Early Identification and Intervention, Particularly in High-Risk Populations

2. Screening and Early Detection of Autoantibodies in Adolescents and Teens

2.1. Prevalence and Importance of Screening

2.1.1. Rising Prevalence of Pre-Diabetes and T1D Risk in Youth Populations

2.1.2. Utility of Autoantibody Screening in Identifying At-Risk Individuals

2.2. Screening Strategies and Recommendations

2.2.1. Current Guidelines and Recommendations for Screening

2.2.2. Community Screening Programs

2.3. Advances in Screening Tools

2.3.1. Emerging Biomarkers Beyond Autoantibodies

2.3.2. Evaluating Sensitivity, Specificity, and Predictive Value of Novel Biomarkers

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.4.1. Ethical Implications of Screening for T1D in Light of Emerging Therapeutic Interventions

2.4.2. Family Counseling and Implications for Early Lifestyle Adjustments

3. Role of Nutrition in Pre-Diabetes Progression

3.1. Nutritional Interventions and Lifestyle Modification

3.1.1. Impact of Dietary Patterns on Insulin Resistance and Inflammation

3.1.2. Evidence-Based Dietary Guidelines

3.2. Specific Nutrients and Dietary Supplements

3.2.1. Role of Specific Nutrients in Insulin Sensitivity and Inflammation Reduction

3.2.2. Potential Benefits of Vitamin D, Zinc, and Magnesium

3.3. Impact of Exercise and Physical Activity

3.3.1. Relationship Between Physical Activity, Metabolic Health, and Beta Cell Preservation

3.3.2. Specific Exercise Recommendations for Adolescents and Teens

3.4. Case Studies and Trials

3.4.1. Clinical Trials and Observational Studies on Nutrition and Lifestyle Changes

3.4.2. Instacart Health Initiatives and Business Partnerships for Nutritional Guidance

4. Section 4

4.1. Pharmacological Interventions

4.1.1. Overview of Immune-Modulating Drugs

4.1.2. Current Trials and Outcomes of Agents Targeting Inflammation and Beta Cell Preservation

4.2. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

4.3. Experimental and Novel Approaches

4.3.1. Advances in Regenerative Medicine and Cell-Based Therapies

4.3.2. Role of the Microbiome in Beta Cell Health and Implications for Pre-Diabetes Interventions

5. Social, Emotional, and Psychological Impacts of Pre-Diabetes and T1D Risk

5.1. Psychological Burden of Screening and Diagnosis

5.1.1. Mental Health Implications of an At-Risk or Pre-Diabetes Diagnosis

5.1.2. Impact of Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) or Self-Monitoring Requirements on Quality of Life

5.2. Family and Peer Dynamics

5.2.1. Influence of Family Dynamics and Peer Relationships on Dietary Adherence and Lifestyle Changes

5.2.2. Importance of Supportive Family Environments and Community Resources

5.3. Interventions to Support Mental Health and Coping Skills

5.3.1. Counseling, Group Support, and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Youth with Pre-Diabetes and Their Families

5.3.2. Integrating Mental Health Services into T1D Prevention Programs

6. Future Directions and Recommendations

6.1. Integrating Screening with Preventative Care

6.1.1. Need for Universal or Targeted Screening Programs in Schools or Primary Care

6.1.2. Combining Screening with Family Education and Resources for Early Intervention

6.2. Further Research on Nutrition, Beta Cell Preservation, and Psychosocial Support

6.2.1. Areas of Potential Research: Large-Scale Longitudinal Studies on Diet and Psychosocial Interventions

6.2.2. Expanding Access to Mental Health Support and Nutrition Education in At-Risk Populations

6.3. Policy Implications and Advocacy

6.3.1. Role of Public Health Policies in Supporting Preventive Care, Nutrition, and Mental Health Resources for At-Risk Youth

6.3.2. Advocacy for Insurance Coverage of Early Screening, Nutritional Counseling, and Psychosocial Support

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DiMeglio, L.A.; Evans-Molina, C.; Oram, R.A. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2018, 391, 2449–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S.; Rawshani, A.; Dabelea, D.; Bonifacio, E.; Anderson, B.J.; Jacobsen, L.M.; Schatz, D.A.; Lernmark, Å. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, R.; Camick, N.; Lemos, J.R.N.; Hirani, K. Gene-environment interaction in the pathophysiology of type 1 diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1335435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2018, 391, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanBuecken, D.; Lord, S.; Greenbaum, C.J. Changing the Course of Disease in Type 1 Diabetes. In Endotext, Feingold, K.R., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., Hofland, J.; MDText.com, Inc. Copyright © 2000-2024, MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, S.; Khan, F.; Hirsch, I.B. New advances in type 1 diabetes. Bmj 2024, 384, e075681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajec, A.; Trebušak Podkrajšek, K.; Tesovnik, T.; Šket, R.; Čugalj Kern, B.; Jenko Bizjan, B.; Šmigoc Schweiger, D.; Battelino, T.; Kovač, J. Pathogenesis of Type 1 Diabetes: Established Facts and New Insights. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchberger, B.; Huppertz, H.; Krabbe, L.; Lux, B.; Mattivi, J.T.; Siafarikas, A. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 70, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadhly, A.F.; Mohammed, A.; Almalki, B.; Alfaez, S.; Mubarak, A.; Alotaibi, E.; Alomran, G.; Almathami, J.; Bazhair, N.; AlShamrani, N.; et al. Moderating effect for illness uncertainty on the relationship of depressive and anxiety symptoms among patients with type 1 diabetes in Taif region, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care 2024, 13, 3576–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, M.; Willaing, I.; Holt, R.I.G. Emerging adulthood and Type 1 diabetes: Insights from the DAWN2 Study. Diabet Med 2018, 35, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombaci, B.; Torre, A.; Longo, A.; Pecoraro, M.; Papa, M.; Sorrenti, L.; La Rocca, M.; Lombardo, F.; Salzano, G. Psychological and Clinical Challenges in the Management of Type 1 Diabetes during Adolescence: A Narrative Review. Children (Basel) 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Yang, W.; Xing, Y.; Lai, Y.; Shan, Z. Global, regional, and national burden of type 1 diabetes in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Res 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Dabelea, D.; Lawrence, J.M. Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002-2012. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, M.A.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Michels, A.W. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2014, 383, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucier, J.; Mathias, P.M. Type 1 Diabetes. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, J.A.; Valdes, A.M. Genetics of the HLA region in the prediction of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2011, 11, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insel, R.A.; Dunne, J.L.; Atkinson, M.A.; Chiang, J.L.; Dabelea, D.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Herold, K.C.; Krischer, J.P.; Lernmark, Å.; et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: A scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1964–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siljander, H.T.; Hermann, R.; Hekkala, A.; Lähde, J.; Tanner, L.; Keskinen, P.; Ilonen, J.; Simell, O.; Veijola, R.; Knip, M. Insulin secretion and sensitivity in the prediction of type 1 diabetes in children with advanced β-cell autoimmunity. Eur J Endocrinol 2013, 169, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.G.; Rewers, M.; Simell, O.; Simell, T.; Lempainen, J.; Steck, A.; Winkler, C.; Ilonen, J.; Veijola, R.; Knip, M.; et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA 2013, 309, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöllänen, P.M.; Ryhänen, S.J.; Toppari, J.; Ilonen, J.; Vähäsalo, P.; Veijola, R.; Siljander, H.; Knip, M. Dynamics of Islet Autoantibodies During Prospective Follow-Up From Birth to Age 15 Years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105, e4638–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyler, J.S.; Bakris, G.L.; Bonifacio, E.; Darsow, T.; Eckel, R.H.; Groop, L.; Groop, P.H.; Handelsman, Y.; Insel, R.A.; Mathieu, C.; et al. Differentiation of Diabetes by Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Prognosis. Diabetes 2017, 66, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, S.K.; Mowery, M.L.; Jialal, I. Biochemistry, C Peptide. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Leighton, E.; Sainsbury, C.A.; Jones, G.C. A Practical Review of C-Peptide Testing in Diabetes. Diabetes Ther 2017, 8, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamiołkowska-Sztabkowska, M.; Głowińska-Olszewska, B.; Bossowski, A. C-peptide and residual β-cell function in pediatric diabetes - state of the art. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2021, 27, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.N.; Collins, K.S.; Lam, A.; Karpen, S.R.; Greeno, B.; Walker, F.; Lozano, A.; Atabakhsh, E.; Ahmed, S.T.; Marinac, M.; et al. C-peptide and metabolic outcomes in trials of disease modifying therapy in new-onset type 1 diabetes: An individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2023, 11, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latres, E.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Oyaski, M.L.; Dayan, C.M.; Colhoun, H.M.; Lachin, J.M.; Skyler, J.S.; Rickels, M.R.; Ahmed, S.T.; Dutta, S.; et al. Evidence for C-Peptide as a Validated Surrogate to Predict Clinical Benefits in Trials of Disease-Modifying Therapies for Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2024, 73, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, E.K.; Cuthbertson, D.; Felton, J.L.; Ismail, H.M.; Nathan, B.M.; Jacobsen, L.M.; Paprocki, E.; Pugliese, A.; Palmer, J.; Atkinson, M.; et al. Persistence of β-Cell Responsiveness for Over Two Years in Autoantibody-Positive Children With Marked Metabolic Impairment at Screening. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2982–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, H.M.; Cuthbertson, D.; Gitelman, S.E.; Skyler, J.S.; Steck, A.K.; Rodriguez, H.; Atkinson, M.; Nathan, B.M.; Redondo, M.J.; Herold, K.C.; et al. The Transition From a Compensatory Increase to a Decrease in C-peptide During the Progression to Type 1 Diabetes and Its Relation to Risk. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2264–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Koutras, N.; Maya, J.; Lemos, J.R.N.; Hirani, K. Blood glucose monitoring devices for type 1 diabetes: A journey from the food and drug administration approval to market availability. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1352302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffel, L.M.; Kanapka, L.G.; Beck, R.W.; Bergamo, K.; Clements, M.A.; Criego, A.; DeSalvo, D.J.; Goland, R.; Hood, K.; Liljenquist, D.; et al. Effect of Continuous Glucose Monitoring on Glycemic Control in Adolescents and Young Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2020, 323, 2388–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffel, L.M.; Bailey, T.S.; Christiansen, M.P.; Reid, J.L.; Beck, S.E. Accuracy of a Seventh-Generation Continuous Glucose Monitoring System in Children and Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2023, 17, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.B.; de Bock, M.; Smith, G.J.; Dart, J.; Fairchild, J.M.; King, B.R.; Ambler, G.R.; Cameron, F.J.; McAuley, S.A.; Keech, A.C.; et al. Effect of a Hybrid Closed-Loop System on Glycemic and Psychosocial Outcomes in Children and Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr 2021, 175, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helminen, O.; Pokka, T.; Tossavainen, P.; Ilonen, J.; Knip, M.; Veijola, R. Continuous glucose monitoring and HbA1c in the evaluation of glucose metabolism in children at high risk for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2016, 120, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steck, A.K.; Dong, F.; Taki, I.; Hoffman, M.; Klingensmith, G.J.; Rewers, M.J. Early hyperglycemia detected by continuous glucose monitoring in children at risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2031–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steck, A.K.; Dong, F.; Taki, I.; Hoffman, M.; Simmons, K.; Frohnert, B.I.; Rewers, M.J. Continuous Glucose Monitoring Predicts Progression to Diabetes in Autoantibody Positive Children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 104, 3337–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steck, A.K.; Dong, F.; Geno Rasmussen, C.; Bautista, K.; Sepulveda, F.; Baxter, J.; Yu, L.; Frohnert, B.I.; Rewers, M.J. CGM Metrics Predict Imminent Progression to Type 1 Diabetes: Autoimmunity Screening for Kids (ASK) Study. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöllänen, P.M.; Lempainen, J.; Laine, A.P.; Toppari, J.; Veijola, R.; Vähäsalo, P.; Ilonen, J.; Siljander, H.; Knip, M. Characterisation of rapid progressors to type 1 diabetes among children with HLA-conferred disease susceptibility. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougnères, P.; Le Fur, S.; Kamatani, Y.; Mai, T.N.; Belot, M.P.; Perge, K.; Shao, X.; Lathrop, M.; Valleron, A.J. Genomic variants associated with age at diagnosis of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes. J Hum Genet 2024, 69, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, K.C.; Bundy, B.N.; Long, S.A.; Bluestone, J.A.; DiMeglio, L.A.; Dufort, M.J.; Gitelman, S.E.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Krischer, J.P.; Linsley, P.S.; et al. An Anti-CD3 Antibody, Teplizumab, in Relatives at Risk for Type 1 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, E.K.; Bundy, B.N.; Stier, K.; Serti, E.; Lim, N.; Long, S.A.; Geyer, S.M.; Moran, A.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Evans-Molina, C.; Herold, K.C. Teplizumab improves and stabilizes beta cell function in antibody-positive high-risk individuals. Sci Transl Med 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.E.; Bundy, B.N.; Anderson, M.S.; Cooney, L.A.; Gitelman, S.E.; Goland, R.S.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Haller, M.J.; Krischer, J.P.; et al. Abatacept for Delay of Type 1 Diabetes Progression in Stage 1 Relatives at Risk: A Randomized, Double-Masked, Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; Kroger, C.J.; Clark, M.; Tisch, R.M. Evolving Antibody Therapies for the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 624568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, K.C.; Gitelman, S.E.; Ehlers, M.R.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Hagopian, W.; Boyle, K.D.; Keyes-Elstein, L.; Aggarwal, S.; Phippard, D.; et al. Teplizumab (anti-CD3 mAb) treatment preserves C-peptide responses in patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial: Metabolic and immunologic features at baseline identify a subgroup of responders. Diabetes 2013, 62, 3766–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steck, A.K.; Vehik, K.; Bonifacio, E.; Lernmark, A.; Ziegler, A.G.; Hagopian, W.A.; She, J.; Simell, O.; Akolkar, B.; Krischer, J.; et al. Predictors of Progression From the Appearance of Islet Autoantibodies to Early Childhood Diabetes: The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY). Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilliard, M.E.; De Wit, M.; Wasserman, R.M.; Butler, A.M.; Evans, M.; Weissberg-Benchell, J.; Anderson, B.J. Screening and support for emotional burdens of youth with type 1 diabetes: Strategies for diabetes care providers. Pediatr Diabetes 2018, 19, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stene, L.C.; Norris, J.M.; Rewers, M.J. Risk Factors for Type 1 Diabetes. In Diabetes in America; Lawrence, J.M., Casagrande, S.S., Herman, W.H., Wexler, D.J., Cefalu, W.T., Eds.; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): Bethesda (MD), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Insel, R.; Dutta, S.; Hedrick, J. Type 1 Diabetes: Disease Stratification. Biomed Hub 2017, 2, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.J.; Leibel, N.I.; Polonsky, W.; Rodriguez, H. Recommendations for Screening and Monitoring the Stages of Type 1 Diabetes in the Immune Therapy Era. Int J Gen Med 2024, 17, 3003–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, T.A.; Ide, A.; Humphrey, K.; Barker, J.M.; Steck, A.; Erlich, H.A.; Yu, L.; Miao, D.; Redondo, M.J.; McFann, K.; et al. Genetic prediction of autoimmunity: Initial oligogenic prediction of anti-islet autoimmunity amongst DR3/DR4-DQ8 relatives of patients with type 1A diabetes. J Autoimmun 2005, 25 Suppl, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, T.A.; Ide, A.; Jahromi, M.M.; Barker, J.M.; Fernando, M.S.; Babu, S.R.; Yu, L.; Miao, D.; Erlich, H.A.; Fain, P.R.; et al. Extreme genetic risk for type 1A diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 14074–14079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlich, H.; Valdes, A.M.; Noble, J.; Carlson, J.A.; Varney, M.; Concannon, P.; Mychaleckyj, J.C.; Todd, J.A.; Bonella, P.; Fear, A.L.; et al. HLA DR-DQ haplotypes and genotypes and type 1 diabetes risk: Analysis of the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium families. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, J.A. Fifty years of HLA-associated type 1 diabetes risk: History, current knowledge, and future directions. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1457213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.P.; Papadopoulos, G.K.; Skyler, J.S.; Pugliese, A.; Parikh, H.M.; Kwok, W.W.; Lybrand, T.P.; Bondinas, G.P.; Moustakas, A.K.; Wang, R.; et al. HLA Class II (DR, DQ, DP) Genes Were Separately Associated With the Progression From Seroconversion to Onset of Type 1 Diabetes Among Participants in Two Diabetes Prevention Trials (DPT-1 and TN07). Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, C.J. A Key to T1D Prevention: Screening and Monitoring Relatives as Part of Clinical Care. Diabetes 2021, 70, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, M.; Achenbach, P.; Addala, A.; Albanese-O'Neill, A.; Battelino, T.; Bell, K.J.; Besser, R.E.J.; Bonifacio, E.; Colhoun, H.M.; Couper, J.J.; et al. Consensus Guidance for Monitoring Individuals With Islet Autoantibody-Positive Pre-Stage 3 Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1276–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, E.K.; Besser, R.E.J.; Dayan, C.; Geno Rasmussen, C.; Greenbaum, C.; Griffin, K.J.; Hagopian, W.; Knip, M.; Long, A.E.; Martin, F.; et al. Screening for Type 1 Diabetes in the General Population: A Status Report and Perspective. Diabetes 2022, 71, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, S.; Ahonen, L.; Dyrlund, T.S.; Kemppainen, E.; Siljander, H.; Hyöty, H.; Ilonen, J.; Toppari, J.; Veijola, R.; Hyötyläinen, T.; et al. Dynamics of Plasma Lipidome in Progression to Islet Autoimmunity and Type 1 Diabetes - Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention Study (DIPP). Sci Rep 2018, 8, 10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, S.; Ahonen, L.; Dyrlund, T.S.; Dickens, A.M.; Siljander, H.; Hyöty, H.; Ilonen, J.; Toppari, J.; Veijola, R.; Hyötyläinen, T.; et al. Cord-Blood Lipidome in Progression to Islet Autoimmunity and Type 1 Diabetes. Biomolecules 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Dickens, A.M.; López-Bascón, M.A.; Lindeman, T.; Kemppainen, E.; Lamichhane, S.; Rönkkö, T.; Ilonen, J.; Toppari, J.; Veijola, R.; et al. Metabolic alterations in immune cells associate with progression to type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaard, A.J.; Weir, J.M.; Jayawardana, K.; Mortensen, H.B.; Pociot, F.; Meikle, P.J. Plasma lipid species at type 1 diabetes onset predict residual beta-cell function after 6 months. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gootjes, C.; Zwaginga, J.J.; Roep, B.O.; Nikolic, T. Functional Impact of Risk Gene Variants on the Autoimmune Responses in Type 1 Diabetes. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 886736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.M.; Ma, Y.; Yin, Z.; Xia, Y.; Du, J.; Huang, J.Y.; Huang, J.J.; Zou, L.; Ye, Z.; Huang, Z. Current understanding of CTLA-4: From mechanism to autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1198365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohnert, B.I.; Webb-Robertson, B.J.; Bramer, L.M.; Reehl, S.M.; Waugh, K.; Steck, A.K.; Norris, J.M.; Rewers, M. Predictive Modeling of Type 1 Diabetes Stages Using Disparate Data Sources. Diabetes 2020, 69, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R.A.; Evans-Molina, C.; Blum, J.S.; DiMeglio, L.A. Established and emerging biomarkers for the prediction of type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Transl Res 2014, 164, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semova, I.; Levenson, A.E.; Krawczyk, J.; Bullock, K.; Williams, K.A.; Wadwa, R.P.; Shah, A.S.; Khoury, P.R.; Kimball, T.R.; Urbina, E.M.; et al. Type 1 diabetes is associated with an increase in cholesterol absorption markers but a decrease in cholesterol synthesis markers in a young adult population. J Clin Lipidol 2019, 13, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oresic, M.; Simell, S.; Sysi-Aho, M.; Näntö-Salonen, K.; Seppänen-Laakso, T.; Parikka, V.; Katajamaa, M.; Hekkala, A.; Mattila, I.; Keskinen, P.; et al. Dysregulation of lipid and amino acid metabolism precedes islet autoimmunity in children who later progress to type 1 diabetes. J Exp Med 2008, 205, 2975–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Qi, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Su, H. Lipid profile alterations and biomarker identification in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients under glycemic control. BMC Endocr Disord 2024, 24, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantle, J.P.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Albright, A.L.; Apovian, C.M.; Clark, N.G.; Franz, M.J.; Hoogwerf, B.J.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Mayer-Davis, E.; Mooradian, A.D.; Wheeler, M.L. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2008, 31 (Suppl 1), S61–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, A.; Mitri, J. Dietary Advice For Individuals with Diabetes. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., Hofland, J., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc. Copyright © 2000-2024, MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsou, S.; Athanasaki, C.; Dimitriadis, G.; Papakonstantinou, E. Acute Effects of Dietary Fiber in Starchy Foods on Glycemic and Insulinemic Responses: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Crossover Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, C.E.; Annan, F.; Higgins, L.A.; Jelleryd, E.; Lopez, M.; Acerini, C.L. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: Nutritional management in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2018, 19 Suppl 27, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, M.A.; Sato, M.N.; Finazzo, C.; Duarte, A.J.; Dib, S.A. Effect of cholecalciferol as adjunctive therapy with insulin on protective immunologic profile and decline of residual β-cell function in new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012, 166, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanou, D.; Penna-Martinez, M.; Filmann, N.; Chung, T.L.; Moran-Auth, Y.; Wehrle, J.; Cappel, C.; Huenecke, S.; Herrmann, E.; Koehl, U.; Badenhoop, K. T-lymphocyte and glycemic status after vitamin D treatment in type 1 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial with sequential crossover. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2017, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Dayal, D.; Sachdeva, N.; Attri, S.V. Effect of 6-months' vitamin D supplementation on residual beta cell function in children with type 1 diabetes: A case control interventional study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2016, 29, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, D.; Pintus, D.; Burnside, G.; Ghatak, A.; Mehta, F.; Paul, P.; Senniappan, S. Treating vitamin D deficiency in children with type I diabetes could improve their glycaemic control. BMC Res Notes 2017, 10, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, E.M.; Mittelman, S.; Pitukcheewanont, P.; Azen, C.G.; Monzavi, R. Effects of vitamin D repletion on glycemic control and inflammatory cytokines in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2016, 17, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Biswal, N.; Bethou, A.; Rajappa, M.; Kumar, S.; Vinayagam, V. Does Vitamin D Supplementation Improve Glycaemic Control In Children With Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus? - A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Diagn Res 2017, 11, Sc15–sc17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahindru, A.; Patil, P.; Agrawal, V. Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e33475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.; Palta, M.; Chewning, B.; Wysocki, T.; Wetterneck, T.; Fiallo-Scharer, R. PCORI Final Research Reports. In Tailoring Resources to Help Children and Parents Manage Type 1 Diabetes; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Copyright © 2019. University of Wisconsin-Madison. All Rights Reserved.: Washington (DC), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, M.I.; Mills, K.E.; Zheng, J.; Regmi, A.; Hu, S.Q.; Gou, L.; Chen, L.L. Low-glycemic index diets as an intervention for diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2019, 110, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromba, V.; Silvestri, F. Vegetarianism and type 1 diabetes in children. Metabol Open 2021, 11, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggioli, R.; Hirani, K.; Jogani, V.G.; Ricordi, C. Modulation of inflammation and immunity by omega-3 fatty acids: A possible role for prevention and to halt disease progression in autoimmune, viral, and age-related disorders. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2023, 27, 7380–7400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Janmeda, P.; Docea, A.O.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Modu, B.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Oxidative stress, free radicals and antioxidants: Potential crosstalk in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Front Chem 2023, 11, 1158198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, J.M.; Lee, H.S.; Frederiksen, B.; Erlund, I.; Uusitalo, U.; Yang, J.; Lernmark, Å.; Simell, O.; Toppari, J.; Rewers, M.; et al. Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration and Risk of Islet Autoimmunity. Diabetes 2018, 67, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Shin, S.; Han, S.N. Multifaceted Roles of Vitamin D for Diabetes: From Immunomodulatory Functions to Metabolic Regulations. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argano, C.; Mirarchi, L.; Amodeo, S.; Orlando, V.; Torres, A.; Corrao, S. The Role of Vitamin D and Its Molecular Bases in Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Disease: State of the Art. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Yoshihara, E.; He, N.; Hah, N.; Fan, W.; Pinto, A.F.M.; Huddy, T.; Wang, Y.; Ross, B.; Estepa, G.; et al. Vitamin D Switches BAF Complexes to Protect β Cells. Cell 2018, 173, 1135–1149.e1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savastio, S.; Cadario, F.; D'Alfonso, S.; Stracuzzi, M.; Pozzi, E.; Raviolo, S.; Rizzollo, S.; Gigliotti, L.; Boggio, E.; Bellomo, G.; et al. Vitamin D Supplementation Modulates ICOS+ and ICOS- Regulatory T Cell in Siblings of Children With Type 1 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadario, F. Vitamin D and ω-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids towards a Personalized Nutrition of Youth Diabetes: A Narrative Lecture. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infante, M.; Ricordi, C.; Sanchez, J.; Clare-Salzler, M.J.; Padilla, N.; Fuenmayor, V.; Chavez, C.; Alvarez, A.; Baidal, D.; Alejandro, R.; et al. Influence of Vitamin D on Islet Autoimmunity and Beta-Cell Function in Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.Y.; Zhang, W.G.; Chen, J.J.; Zhang, Z.L.; Han, S.F.; Qin, L.Q. Vitamin D intake and risk of type 1 diabetes: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3551–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimbekov, N.S.; Coban, S.O.; Atfi, A.; Razzaque, M.S. The role of magnesium in pancreatic beta-cell function and homeostasis. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1458700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Watutantrige-Fernando, S.; Luchini, C.; Solmi, M.; Sartore, G.; Sergi, G.; Manzato, E.; Barbagallo, M.; Maggi, S.; Stubbs, B. Effect of magnesium supplementation on glucose metabolism in people with or at risk of diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Nutr 2016, 70, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, K.E.; Thurmond, D.C. Role of Skeletal Muscle in Insulin Resistance and Glucose Uptake. Compr Physiol 2020, 10, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Cai, X.; Schumann, U.; Velders, M.; Sun, Z.; Steinacker, J.M. Impact of walking on glycemic control and other cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.N.; Mann, J.I.; Williams, S.; Venn, B.J. Advice to walk after meals is more effective for lowering postprandial glycaemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus than advice that does not specify timing: A randomised crossover study. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 2572–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacMillan, F.; Kirk, A.; Mutrie, N.; Matthews, L.; Robertson, K.; Saunders, D.H. A systematic review of physical activity and sedentary behavior intervention studies in youth with type 1 diabetes: Study characteristics, intervention design, and efficacy. Pediatr Diabetes 2014, 15, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta-Uribe, N.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Izquierdo, M.; García-Hermoso, A. Association Between Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior and Physical Fitness and Glycated Hemoglobin in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med 2023, 53, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakola, L.; Vuorinen, A.L.; Takkinen, H.M.; Niinistö, S.; Ahonen, S.; Rautanen, J.; Peltonen, E.J.; Nevalainen, J.; Ilonen, J.; Toppari, J.; et al. Dietary fatty acid intake in childhood and the risk of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: The DIPP birth cohort study. Eur J Nutr 2023, 62, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatovic, D.; Marwaha, A.; Taylor, P.; Hanna, S.J.; Carter, K.; Cheung, W.Y.; Luzio, S.; Dunseath, G.; Hutchings, H.A.; Holland, G.; et al. Ustekinumab for type 1 diabetes in adolescents: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med 2024, 30, 2657–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.L.; Dayan, C.M.; Chatenoud, L.; Sumnik, Z.; Simmons, K.M.; Szypowska, A.; Gitelman, S.E.; Knecht, L.A.; Niemoeller, E.; Tian, W.; Herold, K.C. Teplizumab and β-Cell Function in Newly Diagnosed Type 1 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2023, 389, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, N.; Hagopian, W.; Ludvigsson, J.; Jain, S.M.; Wahlen, J.; Ferry, R.J., Jr.; Bode, B.; Aronoff, S.; Holland, C.; Carlin, D.; et al. Teplizumab for treatment of type 1 diabetes (Protégé study): 1-year results from a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokori, E.; Olatunji, G.; Ogieuhi, I.J.; Aboje, J.E.; Olatunji, D.; Aremu, S.A.; Igwe, S.C.; Moradeyo, A.; Ajayi, Y.I.; Aderinto, N. Teplizumab's immunomodulatory effects on pancreatic β-cell function in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 2024, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Ge, D.; Hu, X.J. Evaluation of teplizumab's efficacy and safety in treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Diabetes 2024, 15, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, S.; Chopra, A.; Nagendra, L.; Kalra, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Teplizumab in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: An Updated Review. touchREV Endocrinol 2023, 19, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanaropoulou, N.M.; Tsatsani, G.C.; Koufakis, T.; Kotsa, K. Teplizumab: Promises and challenges of a recently approved monoclonal antibody for the prevention of type 1 diabetes or preservation of residual beta cell function. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2024, 20, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagopian, W.; Ferry, R.J., Jr.; Sherry, N.; Carlin, D.; Bonvini, E.; Johnson, S.; Stein, K.E.; Koenig, S.; Daifotis, A.G.; Herold, K.C.; Ludvigsson, J. Teplizumab preserves C-peptide in recent-onset type 1 diabetes: Two-year results from the randomized, placebo-controlled Protégé trial. Diabetes 2013, 62, 3901–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilly, E. Treatment with tirzepatide in adults with pre-diabetes and obesity or overweight resulted in sustained weight loss and nearly 99% remained diabetes-free at 176 weeks. Available online: https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/treatment-tirzepatide-adults-pre-diabetes-and-obesity-or (accessed on).

- Herold, K.C.; Pescovitz, M.D.; McGee, P.; Krause-Steinrauf, H.; Spain, L.M.; Bourcier, K.; Asare, A.; Liu, Z.; Lachin, J.M.; Dosch, H.M. Increased T cell proliferative responses to islet antigens identify clinical responders to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) therapy in type 1 diabetes. J Immunol 2011, 187, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescovitz, M.D.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Krause-Steinrauf, H.; Becker, D.J.; Gitelman, S.E.; Goland, R.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Marks, J.B.; McGee, P.F.; Moran, A.M.; et al. Rituximab, B-lymphocyte depletion, and preservation of beta-cell function. N Engl J Med 2009, 361, 2143–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescovitz, M.D.; Greenbaum, C.J.; Bundy, B.; Becker, D.J.; Gitelman, S.E.; Goland, R.; Gottlieb, P.A.; Marks, J.B.; Moran, A.; Raskin, P.; et al. B-lymphocyte depletion with rituximab and β-cell function: Two-year results. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzwajg, M.; Salet, R.; Lorenzon, R.; Tchitchek, N.; Roux, A.; Bernard, C.; Carel, J.C.; Storey, C.; Polak, M.; Beltrand, J.; et al. Low-dose IL-2 in children with recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes: A Phase I/II randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding study. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1808–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.K.; Kant, S. Targeting inflammation in diabetes: Newer therapeutic options. World J Diabetes 2014, 5, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Verma, H.K.; Pande, B.; Costanzo, V.; Ye, W.; Cai, Y.; Bhaskar, L. Physical Activity and Nutritional Influence on Immune Function: An Important Strategy to Improve Immunity and Health Status. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 751374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, F.W.; Roberts, C.K.; Thyfault, J.P.; Ruegsegger, G.N.; Toedebusch, R.G. Role of Inactivity in Chronic Diseases: Evolutionary Insight and Pathophysiological Mechanisms. Physiol Rev 2017, 97, 1351–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, J.M. Infant and childhood diet and type 1 diabetes risk: Recent advances and prospects. Curr Diab Rep 2010, 10, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, M.A.; Laffel, L.M. Current Management of Glycemia in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Akre, S.; Chakole, S.; Wanjari, M.B. Stress-Induced Diabetes: A Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e29142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirotsu, C.; Tufik, S.; Andersen, M.L. Interactions between sleep, stress, and metabolism: From physiological to pathological conditions. Sleep Sci 2015, 8, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiouli, E.; Alexopoulos, E.C.; Stefanaki, C.; Darviri, C.; Chrousos, G.P. Effects of diabetes-related family stress on glycemic control in young patients with type 1 diabetes: Systematic review. Can Fam Physician 2013, 59, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard, M.E.; Harris, M.A.; Weissberg-Benchell, J. Diabetes resilience: A model of risk and protection in type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2012, 12, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Hilliard, M.E.; O'Donnell, M.B.; Zhou, C.; Ellisor, B.M.; Garcia Perez, S.; Duran, B.; Rojas, Y.; Malik, F.S.; DeSalvo, D.J.; et al. Promoting Resilience in Stress Management for Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2428287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.D.; Lindsay, E.K.; Villalba, D.K.; Chin, B. Mindfulness Training and Physical Health: Mechanisms and Outcomes. Psychosom Med 2019, 81, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupini, F.; Basch, M.; Cooke, F.; Vagadori, J.; Gutierrez-Colina, A.; Kelly, K.P.; Streisand, R.; Shomaker, L.; Mackey, E.R. BREATHE-T1D: Using iterative mixed methods to adapt a mindfulness-based intervention for adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Design and development. Contemp Clin Trials 2024, 142, 107551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattoni, A.; Korbutt, G.; Tomei, A.A.; García, A.J.; Pepper, A.R.; Stabler, C.; Brehm, M.; Papas, K.; Citro, A.; Shirwan, H.; et al. Harnessing cellular therapeutics for type 1 diabetes mellitus: Progress, challenges, and the road ahead. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primavera, R.; Regmi, S.; Yarani, R.; Levitte, S.; Wang, J.; Ganguly, A.; Chetty, S.; Guindani, M.; Ricordi, C.; Meyer, E.; Thakor, A.S. Precision Delivery of Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Into the Pancreas Via Intra-arterial Injection Prevents the Onset of Diabetes. Stem Cells Transl Med 2024, 13, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berishvili, E.; Peloso, A.; Tomei, A.A.; Pepper, A.R. The Future of Beta Cells Replacement in the Era of Regenerative Medicine and Organ Bioengineering. Transpl Int 2024, 37, 12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomei, A.A.; Manzoli, V.; Fraker, C.A.; Giraldo, J.; Velluto, D.; Najjar, M.; Pileggi, A.; Molano, R.D.; Ricordi, C.; Stabler, C.L.; Hubbell, J.A. Device design and materials optimization of conformal coating for islets of Langerhans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 10514–10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, X.; Cai, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, L.; Wu, W.; Pugliese, A.; Li, S.; Ricordi, C.; Tan, J. Prevention of chronic diabetic complications in type 1 diabetes by co-transplantation of umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells and autologous bone marrow: A pilot randomized controlled open-label clinical study with 8-year follow-up. Cytotherapy 2022, 24, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, N.I.; Perota, A.; Xhema, D.; Duchi, R.; Lagutina, I.; Galli, C.; Gianello, P. Double transgenic neonatal porcine islets as an alternative source for beta cell replacement therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2409138121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Gong, Z.; Yin, W.; Li, H.; Douroumis, D.; Huang, L.; Li, H. Islet cell spheroids produced by a thermally sensitive scaffold: A new diabetes treatment. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Du, Y.; Zhang, B.; Meng, G.; Liu, Z.; Liew, S.Y.; Liang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, X.; Wu, S.; et al. Transplantation of chemically induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived islets under abdominal anterior rectus sheath in a type 1 diabetes patient. Cell 2024, 187, 6152–6164.e6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, P.O.; Espes, D.; Sisay, S.; Davies, L.C.; Smith, C.I.E.; Svahn, M.G. Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells preserve endogenous insulin production in type 1 diabetes: A Phase I/II randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keymeulen, B.; De Groot, K.; Jacobs-Tulleneers-Thevissen, D.; Thompson, D.M.; Bellin, M.D.; Kroon, E.J.; Daniels, M.; Wang, R.; Jaiman, M.; Kieffer, T.J.; et al. Encapsulated stem cell-derived β cells exert glucose control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, P.O.; Schwarcz, E.; Korsgren, O.; Le Blanc, K. Preserved β-cell function in type 1 diabetes by mesenchymal stromal cells. Diabetes 2015, 64, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, G.G.; Liu, J.S.; Russ, H.A.; Tran, S.; Saxton, M.S.; Chen, R.; Juang, C.; Li, M.L.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Giacometti, S.; et al. Recapitulating endocrine cell clustering in culture promotes maturation of human stem-cell-derived β cells. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 21, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Ko, U.H.; Oh, Y.; Lim, A.; Sohn, J.W.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, H.; Han, Y.M. Islet-like organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells efficiently function in the glucose responsiveness in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 35145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molakandov, K.; Berti, D.A.; Beck, A.; Elhanani, O.; Walker, M.D.; Soen, Y.; Yavriyants, K.; Zimerman, M.; Volman, E.; Toledo, I.; et al. Selection for CD26(-) and CD49A(+) Cells From Pluripotent Stem Cells-Derived Islet-Like Clusters Improves Therapeutic Activity in Diabetic Mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 635405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilleh, A.H.; Beard, S.; Russ, H.A. Enrichment of stem cell-derived pancreatic beta-like cells and controlled graft size through pharmacological removal of proliferating cells. Stem Cell Reports 2023, 18, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, A.A.; Gonzalez, G.C.; Pete, S.I.; De Toni, T.; Berman, D.M.; Rabassa, A.; Diaz, W.; Geary, J.C., Jr.; Willman, M.; Jackson, J.M.; et al. Performance of islets of Langerhans conformally coated via an emulsion cross-linking method in diabetic rodents and nonhuman primates. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabm3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, T.; Stock, A.A.; Devaux, F.; Gonzalez, G.C.; Nunez, K.; Rubanich, J.C.; Safley, S.A.; Weber, C.J.; Ziebarth, N.M.; Buchwald, P.; Tomei, A.A. Parallel Evaluation of Polyethylene Glycol Conformal Coating and Alginate Microencapsulation as Immunoisolation Strategies for Pancreatic Islet Transplantation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 886483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safley, S.A.; Kenyon, N.S.; Berman, D.M.; Barber, G.F.; Cui, H.; Duncanson, S.; De Toni, T.; Willman, M.; De Vos, P.; Tomei, A.A.; et al. Microencapsulated islet allografts in diabetic NOD mice and nonhuman primates. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24, 8551–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, A.A.; Manzoli, V.; De Toni, T.; Abreu, M.M.; Poh, Y.C.; Ye, L.; Roose, A.; Pagliuca, F.W.; Thanos, C.; Ricordi, C.; Tomei, A.A. Conformal Coating of Stem Cell-Derived Islets for β Cell Replacement in Type 1 Diabetes. Stem Cell Reports 2020, 14, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Manzoli, V.; Abreu, M.M.; Verheyen, C.A.; Seskin, M.; Najjar, M.; Molano, R.D.; Torrente, Y.; Ricordi, C.; Tomei, A.A. Effects of Composition of Alginate-Polyethylene Glycol Microcapsules and Transplant Site on Encapsulated Islet Graft Outcomes in Mice. Transplantation 2017, 101, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar, M.; Manzoli, V.; Abreu, M.; Villa, C.; Martino, M.M.; Molano, R.D.; Torrente, Y.; Pileggi, A.; Inverardi, L.; Ricordi, C.; et al. Fibrin gels engineered with pro-angiogenic growth factors promote engraftment of pancreatic islets in extrahepatic sites in mice. Biotechnol Bioeng 2015, 112, 1916–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellappan, D.K.; Sivam, N.S.; Teoh, K.X.; Leong, W.P.; Fui, T.Z.; Chooi, K.; Khoo, N.; Yi, F.J.; Chellian, J.; Cheng, L.L.; et al. Gene therapy and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 108, 1188–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, M. The promise of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in diabetes mellitus therapy: How gene editing is revolutionizing diabetes research and treatment. J Diabetes Complications 2023, 37, 108524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nahas, R.; Al-Aghbar, M.A.; Herrero, L.; van Panhuys, N.; Espino-Guarch, M. Applications of Genome-Editing Technologies for Type 1 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millette, K.; Georgia, S. Gene Editing and Human Pluripotent Stem Cells: Tools for Advancing Diabetes Disease Modeling and Beta-Cell Development. Curr Diab Rep 2017, 17, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, E.P.; Ishikawa, Y.; Zhang, W.; Leite, N.C.; Li, J.; Hou, S.; Kiaf, B.; Hollister-Lock, J.; Yilmaz, N.K.; Schiffer, C.A.; et al. Genome-scale in vivo CRISPR screen identifies RNLS as a target for beta cell protection in type 1 diabetes. Nat Metab 2020, 2, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, M.; Butler, A.E.; Sukhorukov, V.N.; Sahebkar, A. Application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology in diabetes research. Diabet Med 2024, 41, e15240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gutierrez, E.; O'Mahony, A.K.; Dos Santos, R.S.; Marroquí, L.; Cotter, P.D. Gut microbial metabolic signatures in diabetes mellitus and potential preventive and therapeutic applications. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2401654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, R.; Han, B.; Sun, C.; Chen, R.; Wei, H.; Chen, L.; Du, H.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; et al. Functional and metabolic alterations of gut microbiota in children with new-onset type 1 diabetes. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Goffau, M.C.; Luopajärvi, K.; Knip, M.; Ilonen, J.; Ruohtula, T.; Härkönen, T.; Orivuori, L.; Hakala, S.; Welling, G.W.; Harmsen, H.J.; Vaarala, O. Fecal microbiota composition differs between children with β-cell autoimmunity and those without. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giongo, A.; Gano, K.A.; Crabb, D.B.; Mukherjee, N.; Novelo, L.L.; Casella, G.; Drew, J.C.; Ilonen, J.; Knip, M.; Hyöty, H.; et al. Toward defining the autoimmune microbiome for type 1 diabetes. Isme j 2011, 5, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Goffau, M.C.; Fuentes, S.; van den Bogert, B.; Honkanen, H.; de Vos, W.M.; Welling, G.W.; Hyöty, H.; Harmsen, H.J. Aberrant gut microbiota composition at the onset of type 1 diabetes in young children. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murri, M.; Leiva, I.; Gomez-Zumaquero, J.M.; Tinahones, F.J.; Cardona, F.; Soriguer, F.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I. Gut microbiota in children with type 1 diabetes differs from that in healthy children: A case-control study. BMC Med 2013, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanen, T.; Franzosa, E.A.; Schwager, R.; Tripathi, S.; Arthur, T.D.; Vehik, K.; Lernmark, Å.; Hagopian, W.A.; Rewers, M.J.; She, J.X.; et al. The human gut microbiome in early-onset type 1 diabetes from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018, 562, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiner, E.; Willie, E.; Vijaykumar, B.; Chowdhary, K.; Schmutz, H.; Chandler, J.; Schnell, A.; Thakore, P.I.; LeGros, G.; Mostafavi, S.; et al. Gut CD4(+) T cell phenotypes are a continuum molded by microbes, not by T(H) archetypes. Nat Immunol 2021, 22, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowosad, C.R.; Mesin, L.; Castro, T.B.R.; Wichmann, C.; Donaldson, G.P.; Araki, T.; Schiepers, A.; Lockhart, A.A.K.; Bilate, A.M.; Mucida, D.; Victora, G.D. Tunable dynamics of B cell selection in gut germinal centres. Nature 2020, 588, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhang, C.; Xing, Y.; Xue, G.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, F.; Wu, G.; Hu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Lu, A.; et al. Remodelling of the gut microbiota by hyperactive NLRP3 induces regulatory T cells to maintain homeostasis. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, P.; Nikolic, T.; Pellegrini, S.; Sordi, V.; Imangaliyev, S.; Rampanelli, E.; Hanssen, N.; Attaye, I.; Bakker, G.; Duinkerken, G.; et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation halts progression of human new-onset type 1 diabetes in a randomised controlled trial. Gut 2021, 70, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Nicolucci, A.C.; Virtanen, H.; Schick, A.; Meddings, J.; Reimer, R.A.; Huang, C. Effect of Prebiotic on Microbiota, Intestinal Permeability, and Glycemic Control in Children With Type 1 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019, 104, 4427–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.; Reimer, R.A.; Doulla, M.; Huang, C. Effect of prebiotic intake on gut microbiota, intestinal permeability and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, V.; Hendrieckx, C.; Sturt, J.; Skinner, T.C.; Speight, J. Diabetes Distress Among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Curr Diab Rep 2016, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Picón-César, M.J.; Tinahones, F.J.; Martínez-Montoro, J.I. Type 1 diabetes-related distress: Current implications in care. Eur J Intern Med 2024, 125, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rechenberg, K.; Whittemore, R.; Holland, M.; Grey, M. General and diabetes-specific stress in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017, 130, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iturralde, E.; Rausch, J.R.; Weissberg-Benchell, J.; Hood, K.K. Diabetes-Related Emotional Distress Over Time. Pediatrics 2019, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaser, S.S.; Linsky, R.; Grey, M. Coping and psychological distress in mothers of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Matern Child Health J 2014, 18, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheraghi, F.; Shamsaei, F.; Mortazavi, S.Z.; Moghimbeigi, A. The Effect of Family-centered Care on Management of Blood Glucose Levels in Adolescents with Diabetes. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2015, 3, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostaminasab, S.; Nematollahi, M.; Jahani, Y.; Mehdipour-Rabori, R. The effect of family-centered empowerment model on burden of care in parents and blood glucose level of children with type I diabetes family empowerment on burden of care and HbA1C. BMC Nurs 2023, 22, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispriantari, A.; Agustina, R.; Konlan, K.D.; Lee, H. Family-centered interventions for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: An integrative review. Child Health Nurs Res 2023, 29, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siminerio, L.M.; Albanese-O'Neill, A.; Chiang, J.L.; Hathaway, K.; Jackson, C.C.; Weissberg-Benchell, J.; Wright, J.L.; Yatvin, A.L.; Deeb, L.C. Care of young children with diabetes in the child care setting: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2834–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Ersig, A.L.; McCarthy, A.M. The Influence of Peers on Diet and Exercise Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr Nurs 2017, 36, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.A.; Bélanger, M.F.; Donovan, D.; Carrier, N. Relationship between eating behaviors and physical activity of preschoolers and their peers: A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.J.; Steck, A.K.; Pugliese, A. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2018, 19, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, K.; Marfella, R.; Ciotola, M.; Di Palo, C.; Giugliano, F.; Giugliano, G.; D'Armiento, M.; D'Andrea, F.; Giugliano, D. Effect of a mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: A randomized trial. Jama 2004, 292, 1440–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovalle, F.; Grimes, T.; Xu, G.; Patel, A.J.; Grayson, T.B.; Thielen, L.A.; Li, P.; Shalev, A. Verapamil and beta cell function in adults with recent-onset type 1 diabetes. Nat Med 2018, 24, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejgaard, T.F.; von Scholten, B.J.; Christiansen, E.; Kreiner, F.F.; Bardtrum, L.; von Herrath, M.; Mathieu, C.; Madsbad, S. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide in type 1 diabetes by baseline characteristics in the ADJUNCT ONE and ADJUNCT TWO randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021, 23, 2752–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluestone, J.A.; Buckner, J.H.; Fitch, M.; Gitelman, S.E.; Gupta, S.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Herold, K.C.; Lares, A.; Lee, M.R.; Li, K.; et al. Type 1 diabetes immunotherapy using polyclonal regulatory T cells. Sci Transl Med 2015, 7, 315ra189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Cai, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J. The role of peer social relationships in psychological distress and quality of life among adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: A longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Screening Parameter | Description | Target Population | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoantibody Screening | Detection of islet autoantibodies (such as GAD65, IA-2, ZnT8) indicating autoimmune activity | Adolescents with a family history of T1D or other autoimmune diseases | [17,18,19] |

| Genetic Screening | Identification of HLA genotypes associated with increased T1D risk | High-risk individuals, especially those with a first-degree relative with T1D | [16,49,50,51,52,53] |

| Metabolic Markers | Measurement of C-peptide levels and oral glucose tolerance tests to assess beta-cell function | Adolescents with positive autoantibodies or genetic predisposition | [22,23,24,25,26,27,28] |

| Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) | Use of CGM devices to detect dysglycemia in at-risk adolescents | Adolescents with positive autoantibodies or early signs of glucose intolerance | [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] |

| Intervention | Description | Expected Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Glycemic Index Diet | Emphasis on consuming foods with a low glycemic index to stabilize blood sugar levels | Improved glycemic control and reduced insulin resistance | [80] |

| Mediterranean Diet | Diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats | Reduction in inflammation and improvement in insulin sensitivity | [179] |

| Physical Activity | Regular aerobic and resistance training exercises | Enhanced glucose uptake and improved cardiovascular health | [94,95,96] |

| Behavioral Counseling | Structured programs focusing on lifestyle modification | Increased adherence to healthy behaviors and weight management | [125] |

| Drug Class | Example Agent | Mechanism of Action | Current Research Status | Expected Outcomes | Side Effects/Considerations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Modulators | Teplizumab | Anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody modulating T-cell activity to reduce autoimmune beta cell attack | Phase III trials; shown to delay T1D onset | Delay in progression to clinical T1D, preservation of beta cell function | Possible immunosuppression; monitoring required | [39] |

| Abatacept | Interferes with T-cell costimulation to reduce immune response against beta cells | Early clinical trials | Slower beta cell decline, potential delay in T1D onset | Mild to moderate injection site reactions | [41] | |

| Anti-CD20 (e.g., Rituximab) | Depletes B-cells to modulate autoimmune activity | Phase II trials; varied efficacy | Reduction in autoimmune activity, partial beta cell preservation | Risk of infection due to B-cell depletion | [39,43] | |

| Anti-Inflammatory Agents | Interleukin-2 (IL-2) | Low-dose IL-2 therapy aimed at enhancing regulatory T-cell function | Ongoing clinical studies | Improved immune tolerance, reduced beta cell stress | Requires dosage optimization; risk of fever | [114] |

| Beta Cell Modulators | Verapamil | Calcium channel blocker potentially inhibiting beta cell apoptosis | Phase II trials; promising in T1D | Beta cell survival enhancement, improved glucose control | Dizziness, low blood pressure | [180] |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists | Enhance beta cell proliferation and insulin secretion in response to glucose | Phase III for T2D, exploratory for T1D | Increased beta cell function and insulin sensitivity | Nausea, potential risk of pancreatitis | [181] | |

| Other Novel Agents | Treg-enhancing agents | Agents aiming to boost regulatory T-cell numbers and function | Preclinical and early clinical trials | Enhanced immune tolerance, delayed beta cell decline | Long-term safety under investigation | [182] |

| Intervention | Description | Expected Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Techniques to manage anxiety and stress related to health monitoring and disease risk | Reduced anxiety levels and improved coping mechanisms | [123,124,125,126] |

| Family Therapy | Counseling sessions involving family members to improve communication and support | Enhanced family cohesion and better adherence to lifestyle interventions | [45] |

| Peer Support Groups | Group sessions with peers facing similar health challenges | Increased emotional support and shared coping strategies | [183] |

| Stress Management Programs | Programs teaching stress reduction techniques such as mindfulness and relaxation exercises | Lowered stress levels and improved overall well-being | [45,123] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).