1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a metabolic disorder characterized by elevated blood glucose levels, primarily due to a deficiency in insulin production and/or action [

1,

2]. Along with its multiple causes, there are modifiable risk factors that directly affect its evolution, control goals, and prognosis. Therefore, its management from the primary care level requires a risk-based approach that allows for comprehensive assessment to improve the identification of at-risk groups, treatment decisions, and thus impact better quality of life in the short and long term.

Globally, T2DM has emerged as an expanding health problem [

3]. In Mexico alone, it has been reported that about 15.6% of adults live with the disease, with substantial increases in recent decades [

4,

5] reporting more than 476,000 new cases in the country in 2022, with over 76.5% of cases in patients under 65 years of age, of which about 7,000 were diagnosed in the State of Michoacán [

6].

Given the significance and burden it represents for public health systems, the role of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) has been highly useful not only as an auxiliary diagnostic tool [

7] but also for evaluating treatment response oriented towards goals [

8]. The American Diabetes Association defines glycemic control goals as HbA1c levels < 7% in most cases [

2] which, although varying based on individual contexts [

9], follow a common principle that includes appropriate pharmacological intervention and the practice of favorable lifestyles.

In the comprehensive approach to T2DM patients, lifestyles are of great importance [

10]. These are defined as behavioral patterns that influence the state of the disease [

11] and have the potential to be modified [

12,

13]. Additionally, they can be viewed in terms of the presence or absence of "unhealthy" behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol intake, diet type, sedentary lifestyle, among others [

14,

15,

16], where the individual is responsible and protagonist of their own health decisions [

17]. Therefore, various tools have been designed for their study, one of these being the

Instrument to Measure Lifestyle in Diabetics (IMEVID), a self-administered questionnaire developed by the Mexican Social Security Institute (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, IMSS), which is a standardized and validated tool in Mexico. Its design allows determining whether a diabetic lifestyle is favorable or not [

18], and has been highly useful in identifying lifestyle as a risk factor in Mexican patients with T2DM in different settings [

19,

20].

More recently, in the context of primary care in IMSS family medicine clinics, a significant association has been highlighted between HbA1c levels < 7% and favorable lifestyles such as increased physical exercise, lower tobacco consumption, and better eating habits [

21]. Other authors conclude that unfavorable lifestyle is associated with the presence of metabolic uncontrol [

22]. These studies highlight the importance of considering lifestyle factors in diabetes treatment and their impact on daily activities, therefore, the present work sought to determine the relationship between lifestyles, obtained through the IMEVID score, with glycemic control goals in T2DM patients through HbA1c levels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a descriptive, observational, retrospective, and cross-sectional cohort study conducted from November 2021 to February 2022.

2.2. Study Population and Setting

The study included 385 participants under 65 years of age with T2DM who received medical care at the Family Medicine Service of Hospital Clínica Uruapan – Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado, ISSSTE) in Michoacán, Mexico. Participants were required to have HbA1c reports less than 6 months old and agree to complete the IMEVID questionnaire.

We excluded patients who did not complete the questionnaire, those diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, and those who were pregnant during the study period.

2.3. Data Collection

Following institutional authorization, we implemented the IMEVID questionnaire, wich .consists of 25 closed questions across seven dimensions: nutrition, physical activity, tobacco consumption, alcohol consumption, diabetes information, emotions, and therapeutic adherence. Each item offered three response options scored as 0, 2, or 4 points, with 4 representing the most desirable response. The total possible score ranged from 0 to 100, with no odd values permitted.

Following López-Carmona et al. (2004), we categorized participants into three groups based on quartile distribution: (i) unfavorable lifestyle (scores < 25th percentile), (ii) moderately favorable lifestyle (scores between 25th-75th percentile), and (iii) favorable lifestyle (scores ≥ 75th percentile) [

23].

Sociodemographic data included age, occupation, education level, marital status, and BMI (kg/m²). Disease-specific variables comprised years since diagnosis and HbA1c percentage. Based on NOM 015-SSA2-2010 and American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2023 guidelines, we defined good glycemic control as HbA1c < 7% and poor control as HbA1c ≥ 7% [

2,

24].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We conducted statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism version 10.1.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Descriptive statistics included absolute values (n), percentages (%), measures of central tendency (mean ± standard deviation, median), and range (minimum-maximum). After confirming normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, we employed Student's t-test for comparing means and chi-square test for proportions. We calculated odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

To ensure participant anonymity, data collection instruments excluded personal identifiers. All participants provided informed consent after receiving information about the study objectives. The research protocol received institutional approval (Registration Number: O2/001.1).

3. Resultados

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

The study included 385 participants with a mean age of 47.7 ± 13.1 years. Women constituted the majority of participants (54.5%, 211 cases), with most subjects being ≥ 41 years old (71.4%, 275 cases). Regarding marital status, married individuals represented the largest group (56.1%, 216 cases). In terms of educational attainment, participants with bachelor's degrees comprised 26% (100 cases) of the sample, followed by those with high school education (22.9%, 88 cases).

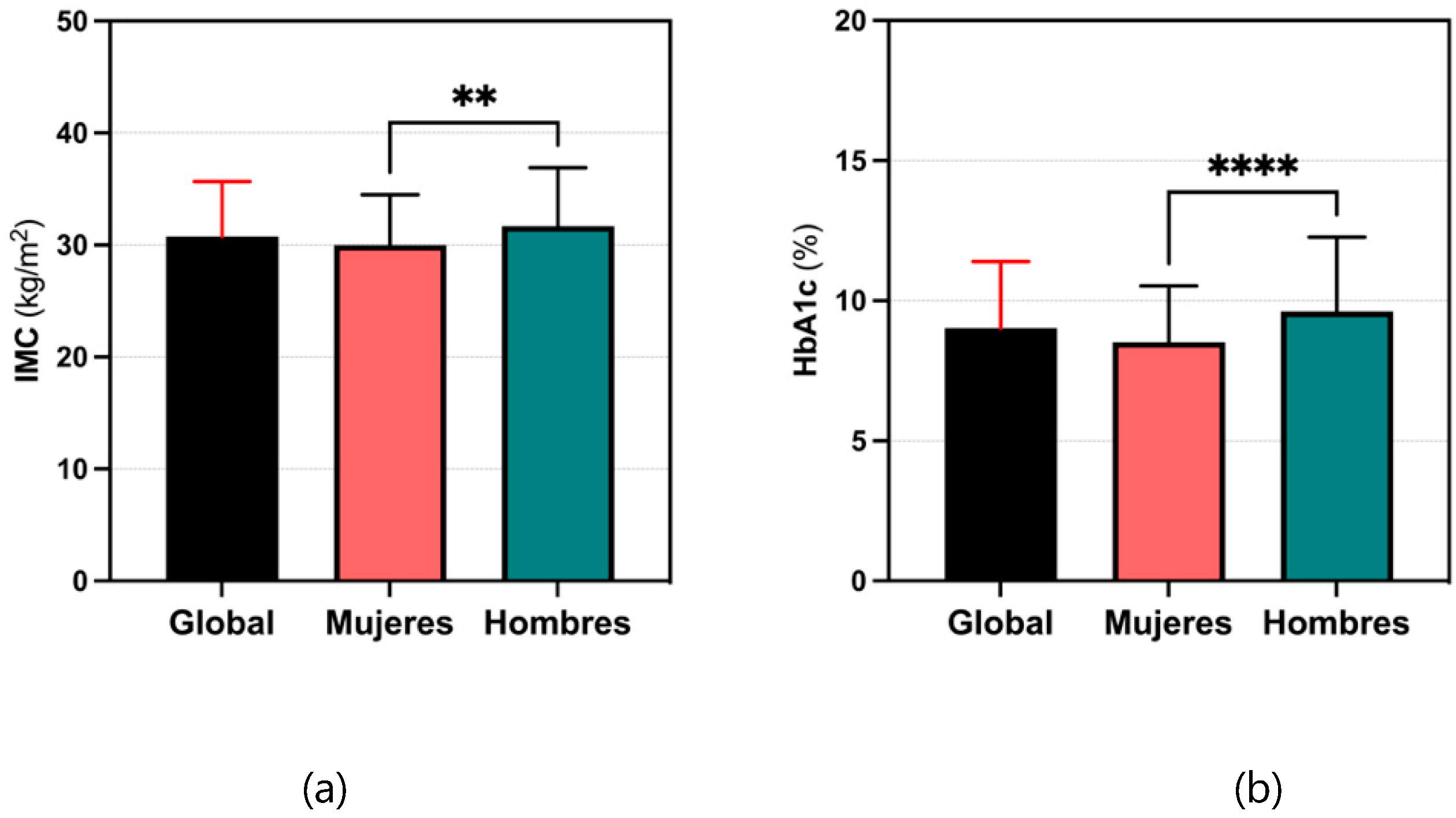

The mean BMI of participants was 30.8 ± 4.9 kg/m², with a predominance of cases showing some degree of obesity (55.1%, 212 cases). The mean HbA1c was 9.0 ± 2.4% (range: 6-15%, median: 8%, IQR: 7-11%), with 81.8% of cases (315/385) showing HbA1c levels ≥ 7%. When comparing means by sex, male participants demonstrated significantly higher BMI than females (p = 0.0094), as well as higher HbA1c levels (9.6% vs 8.5%; 95% CI 0.6256-1.563, p < 0.0001) (

Figure 1).

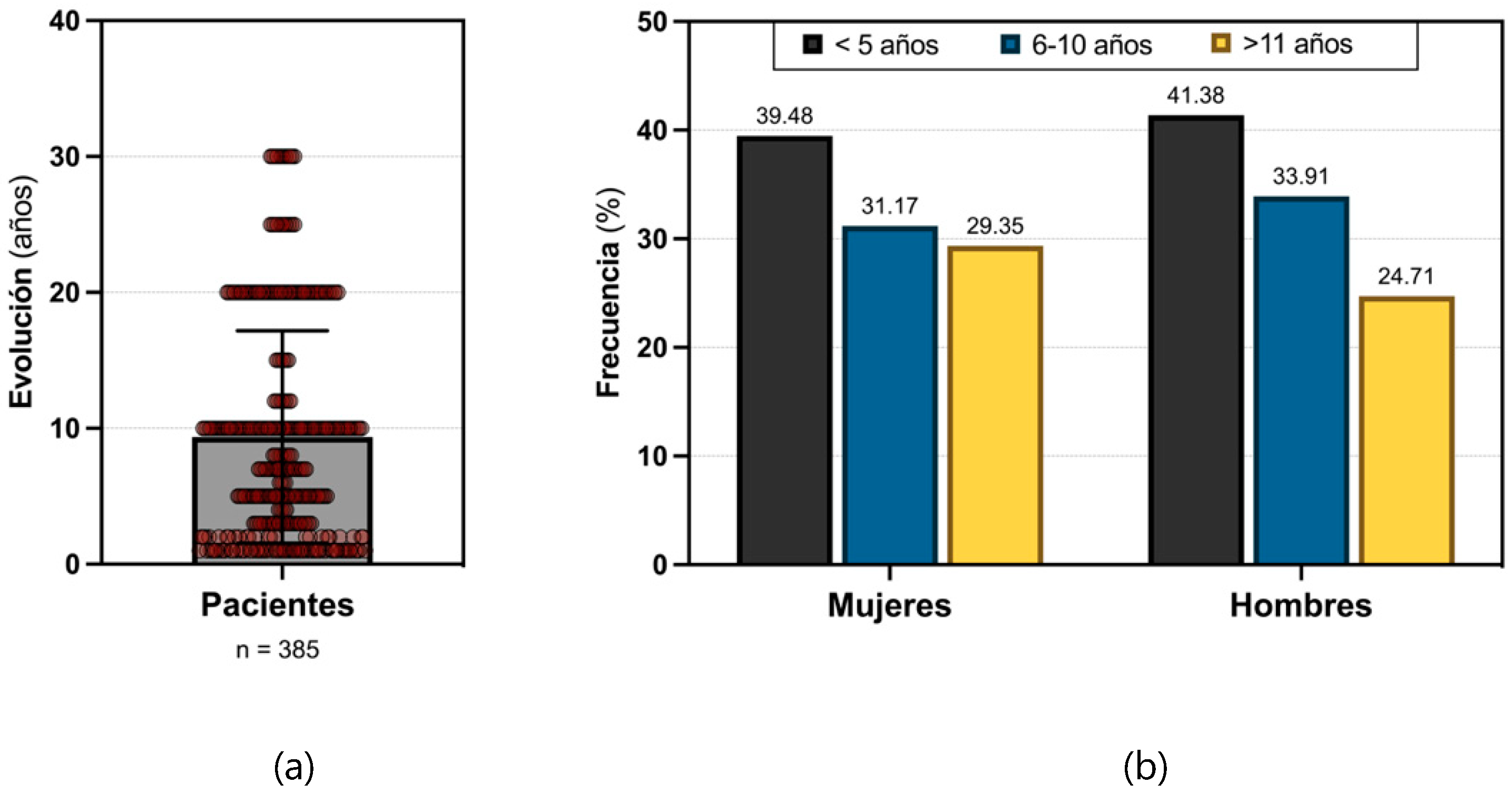

The mean disease duration for T2DM was 9.4 ± 7.8 years (range: 1-30 years), with the highest number of cases observed in patients with less than 5 years since diagnosis in both sexes, followed by those with 6 to 10 years of disease evolution (

Figure 2).

3.2. Glycemic Control Associated with General Population Characteristics

The presence of glycemic dyscontrol showed significant associations with higher mean age (48.4 vs 44.9 years; 95% CI 0.1162-6.897; p = 0.0427), longer disease duration (9.8 vs 7.6 years; 95% CI 0.1005-4.147; p = 0.0397), and higher BMI (31.8 vs 26 kg/m²; 95% CI 4.672-6.932; p < 0.0001). Furthermore, patients at higher risk of glycemic dyscontrol were those aged ≥ 41 years (p < 0.0001), those with 6-10 years of disease duration (p = 0.0257), and those with obesity (p < 0.0001) (

Table 1).

3.3. Lifestyle Patterns Associated with General Population Characteristics

The overall IMEVID score averaged 45.67 ± 12.38 points (range: 26-74 points, median: 42 points, IQR: 34-56 points) out of a possible 100 points. Analysis of lifestyle categories revealed that most participants demonstrated a moderately unfavorable lifestyle (42.6%, 164 cases), followed by 114 participants (29.6%) with favorable lifestyle patterns and 107 (27.8%) with unfavorable patterns. Among participants categorized with unfavorable lifestyle patterns, women represented a significant majority (63.6%), with most being ≥ 41 years old (76.6%, 82/107) and having less than 5 years since disease diagnosis. Notably, obesity emerged as the only variable showing statistical significance when compared across lifestyle groups (

Table 2).

The previous table presents a comprehensive breakdown of demographic and clinical characteristics across the three lifestyle categories. The data demonstrates notable patterns, particularly the high prevalence of obesity among those with unfavorable lifestyle patterns, which reached statistical significance. The table also illustrates the predominance of female participants and those aged ≥ 41 years in the unfavorable lifestyle category, though these differences did not reach statistical significance across groups.

3.4. Glycemic Control Associated with Lifestyle Patterns

Analysis revealed significantly higher HbA1c levels among participants with unfavorable lifestyle patterns (9.6%) when compared to those with moderately unfavorable and favorable lifestyle patterns (8.9% and 8.9%, respectively) (

Table 3). Notably, poor glycemic control was observed in 98.1% of cases with unfavorable lifestyle patterns (105/385).

4. Discussion

This investigation of 385 participants revealed important patterns in lifestyle factors and glycemic control among T2DM patients. The predominant female representation (>50%) aligns with both national[

25] and international epidemiological data [

25,

26], providing external validity to our findings. The demographic profile of participants—predominantly aged ≥ 41 years, with T2DM duration averaging 9.4 years—reflects a typical adult-onset diabetes population.

A key finding was the high prevalence of obesity, with a mean BMI of 30.8 kg/m². This finding, consistent with national [

5] and international trends [

27], underscores the close relationship between obesity and T2DM[

29]. The observed association between higher BMI and reduced weight management success [

28] suggests a potential cycle that may complicate diabetes management.

Glycemic control analysis revealed concerning patterns. The mean HbA1c of 9.0 ± 2.4% exceeded typical levels reported in type 1 diabetes (8.4%) [

29], with male participants showing significantly poorer control. The association between glycemic dyscontrol and factors such as advanced age, longer disease duration, and higher BMI identifies specific risk groups requiring targeted intervention strategies.

The IMEVID lifestyle assessment yielded particularly notable results. The mean score of 45.67 ± 12.38 points, with no participant reaching the 'healthy lifestyle' threshold of 75 points [

23], indicates a systemic challenge in lifestyle management. While women aged ≥ 41 years with recent diagnosis (<5 years) comprised the majority of those with unfavorable lifestyle patterns, obesity emerged as the sole statistically significant predictor of poor lifestyle habits, supporting previous findings in Mexican populations [

27].

Domain-specific analysis revealed multiple factors contributing to poor glycemic control. Nutritional deficiencies [

30], and insufficient physical activity [

31] emerged as primary behavioral factors. The psychological domain highlighted concerning patterns of emotional reactivity and pessimistic thinking among poorly controlled patients. Treatment adherence analysis revealed that motivation and consistent effort significantly influence glycemic control, manifesting through dietary compliance and medication adherence.

Study limitations warrant consideration. The requirement for recent HbA1c data necessarily reduced our sample size. Additionally, while the IMEVID questionnaire provides valuable insight into lifestyle patterns, it cannot capture all variables affecting metabolic control. Future research should consider incorporating additional metabolic markers and a broader range of lifestyle factors.

5. Conclusions

This investigation establishes a clear and significant relationship between lifestyle patterns and glycemic control in T2DM patients. The findings demonstrate that individuals with unfavorable lifestyle patterns exhibited markedly elevated HbA1c levels compared to their counterparts with more favorable lifestyle habits. This relationship persisted across multiple demographic and clinical variables, highlighting the crucial role of lifestyle management in diabetes care.

The study's results carry important implications for clinical practice, suggesting that comprehensive diabetes management should prioritize lifestyle modification strategies alongside traditional medical interventions. The identified associations between specific lifestyle domains and glycemic control provide valuable insights for developing targeted interventions and patient education programs.

These findings underscore the importance of regular lifestyle assessment and modification as integral components of diabetes management protocols. Future research should focus on developing and evaluating targeted interventions that address the specific lifestyle factors identified as most significantly impacting glycemic control.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through the dedicated support and collaboration of numerous individuals and institutions. We express our profound appreciation to the healthcare professionals and administrative staff of Hospital Clínica Uruapan – ISSSTE for their invaluable assistance throughout this study. Their commitment to patient care and research excellence significantly contributed to the success of this investigation. We also acknowledge the productive interinstitutional collaboration between ISSSTE and IMSS facilities in Uruapan and Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico. This partnership exemplifies the power of institutional cooperation in advancing medical research and improving patient care in our region. Special recognition is due to the clinical staff who facilitated patient interactions and data collection, as well as to the administrative personnel who provided essential logistical support. Their collective efforts were instrumental in the completion of this research project.

References

- Dong, W.; Tse, E.T.Y.; Mak, L.I.; Wong, C.K.H.; Wan, Y.F.; Tang, E.H.M.; et al. Non-laboratory-based Risk Assessment Model for Case Detection of Diabetes Mellitus and Pre-diabetes in Primary Care. J Diab Inv. 2022, 13, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; et al. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46 (Suppl. S1), S19–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Ferrannini, E.; Groop, L.; Henry, R.R.; Herman, W.H.; Holst, J.J.; et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1, 15019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Martínez, R.; Basto-Abreu, A.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Zárate-Rojas, E.; Villalpando, S.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T. Prevalencia De Diabetes Por Diagnóstico Médico Previo en México. Salud Pública De México 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Romero-Martínez, M.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; Colchero, M.A.; et al. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2020 sobre Covid-19. Resultados nacionales; Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública: Cuernavaca, México, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Salud, DGE. Anuario de Morbilidad 1984 - 2022 México: Secretaría de Salud; 2023 [Disponible en. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/anuarios-de-morbilidad-1984-a-2022.

- International Expert, C. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect of intensive diabetes management on macrovascular events and risk factors in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Am J Cardiol. 1995, 75, 894–903. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber, A.J.; Abrahamson, M.J.; Barzilay, J.I.; Blonde, L.; Bloomgarden, Z.T.; Bush, M.A.; et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the Comprehensive Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm - 2019 Executive Summary. Endocr Pract. 2019, 25, 69–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckman, J.A.; Creager, M.A. Vascular Complications of Diabetes. Circ Res. 2016, 118, 1771–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, K.L.; Corin, E.; Potvin, L. A theoretical proposal for the relationship between context and disease. Sociol of Health & Illness 2001, 23, 776–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, J. Social capital and health: Implications for public health and epidemiology. Soc Sci & Med. 1998, 47, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brivio, F.; Viganò, A.; Paterna, A.; Palena, N.; Greco, A. Narrative Review and Analysis of the Use of “Lifestyle” in Health Psychology. Int J Env Res & Pub Health 2023, 20, 4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerham, W.C.D.; Wolfe, J.; Bauldry, S. Health Lifestyles in Late Middle Age. Research on Aging 2020, 42, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daw, J.; Margolis, R.; Wright, L. Emerging Adulthood, Emergent Health Lifestyles: Sociodemographic Determinants of Trajectories of Smoking, Binge Drinking, Obesity, and Sedentary Behavior. J Health & Soc Behav. 2017, 58, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, T.D. Profiles in health: Multiple roles and health lifestyles in early adulthood. Soc Sci & Med. 2017, 178, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrocks, C.; Johnson, S. A socially situated approach to inform ways to improve health and wellbeing. Sociol of Health & Illness 2014, 36, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barranco-Cuevas, I.A.; Zavaleta-García, B.H.; Rodríguez-Chávez, M.D.C.; García-Galicia, A.; Gutiérrez-Gabriel, I.; González-López, A.M.; et al. Lifestyle Impact on Glycemic Control in Patients Diagnosed With Type 2 Diabetes. Lifestyle Impact on Glycemic Control in Patients Diagnosed With Type 2 Diabetes 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Rocha, S.A.; Galicia-Rodriguez, L.; Vargas-Daza, E.R.; Martinez-Gonzalez, L.; Villarreal-Rios, E. [To face up the disease strategy as a risk factor for the life style in type 2 diabetics]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2010, 48, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Figueroa-Suarez, M.E.; Cruz-Toledo, J.E.; Ortiz-Aguirre, A.R.; Lagunes-Espinosa, A.L.; Jimenez-Luna, J.; Rodriguez-Moctezuma, J.R. [Life style and metabolic control in DiabetIMSS program]. Gac Med Mex. 2014, 150, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Velazquez-Lopez, L.; Segura Cid Del Prado, P.; Colin-Ramirez, E.; Munoz-Torres, A.V.; Escobedo-de la Pena, J. Adherence to non-pharmacological treatment is associated with the goals of cardiovascular control and better eating habits in Mexican patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2022, 34, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgers-Félix, R.; García-Torres, O.; Álvarez-Villaseñor, A.S. Estilo de vida y descontrol metabólico en pacientes inscritos en el módulo DiabetIMSS. Medicina General y de Familia 2022, 11, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carmona, J.M.; Rodríguez-Moctezuma, J.R.; Ariza-Andraca, C.R.; Martínez-Bermúdez, M. Estilo de vida y control metabólico en pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Validación por constructo del IMEVID. Atención Primaria 2004, 33, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-015-SSA2-2010, Para la prevención, tratamiento y control de la diabetes mellitus. México: Diario Oficial de la Federación: Secretaría de Salud; 2010.

- Joseph, J.J.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Talegawkar, S.A.; Effoe, V.S.; Okhomina, V.; Carnethon, M.R.; et al. Modifiable Lifestyle Risk Factors and Incident Diabetes in African Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2017, 53, e165–e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeh, A.E.; Nkombua, L. A study of the knowledge and practice of lifestyle modification in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Middelburg sub-district of Mpumalanga. South African Family Practice 2018, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgers Félix, R.; García Torres, O.; Álvarez Villaseñor, A.S. Estilo de vida y descontrol metabólico en pacientes inscritos en el módulo DiabetIMSS. Medicina General y de Familia 2022, 11, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobe, K.; Maegawa, H.; Tabuchi, H.; Nakamura, I.; Uno, S. Impact of body mass index on the efficacy and safety of ipragliflozin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A subgroup analysis of 3-month interim results from the Specified Drug Use Results Survey of Ipragliflozin Treatment in Type 2 Diabetic Patients: Long-term Use study. J Diabetes Investig. 2019, 10, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, W.H.; Braffett, B.H.; Kuo, S.; Lee, J.M.; Brandle, M.; Jacobson, A.M.; et al. What are the clinical, quality-of-life, and cost consequences of 30 years of excellent vs. poor glycemic control in type 1 diabetes? J Diabetes Complications 2018, 32, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurohmi, S. Perbedaan Konsumsi Sayur Dan Buah Pada Subjek Normal Dan Penyandang Diabetes Mellitus Tipe 2. Darussalam Nutrition Journal 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, C.; Correia, C.; Oliveira Albuquerque, S. Adherence to physical activity in people with type 2 diabetes. Revista INFAD de Psicología International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology 2021, 1, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).