1. Introduction

In recent years, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology has developed rapidly and extensively in the civilian and research sectors [

1]. Object detection in aerial images, especially in remote sensing images (RSI) collected by UAVs, poses significant obstacles for the visual sensor systems of the UAVs. Unlike natural images, aerial images often feature objects embedded within complex environments characterized by substantial scale variations, differing resolutions, and objects with various orientations [

2]. Many excellent detectors employ the horizontal bounding box (HBB) for target localization, including YOLO series [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], and RCNN-series [

8,

9]. Nonetheless, because of the dense object distribution in RSI, HBB introduces more noise and covers unnecessary regions around the target, leading to worse localization performance. To solve these problems, the oriented bounding box (OBB) adopts the direction for regression in addition to the HBB, resulting in a more accurate capture of the object’s shape and better localization. Therefore, oriented object detection of remote sensing images from UAV aims to enhance detection accuracy and efficiency by leveraging advanced convolutional neural networks that can precisely localize and classify objects at various orientations and scales.

Multi-scale feature extraction and fusion are crucial for enhancing the performance of object detectors. Remote sensing datasets often contain complex features at various scales, making it difficult for single-scale methods to capture all pertinent details. The considerable scale disparities among objects in remote sensing images reflect the varied sizes across categories. Consequently, despite the inherent difficulties of these images, developing and configuring a general and effective multi-scale deep learning module can greatly enhance object detection in UAV-based remote sensing imagery. The Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [

10] enhances feature representation by up-sampling semantically strong high-level features and merging them with original CNN outputs through lateral connections. For example, most existing oriented object detection networks utilize the FPN or FPN-alike structure [

5,

9,

11]. These networks demonstrate the efficiency of applying Feature Pyramids to extract and fuse multi-scale features for object detection. Pyramid Convolution [

12] applies efficient pyramidal convolution for merging multi-scale features. Additionally, InceptionNets [

13] demonstrated that incorporating residual connection significantly enhances the multi-scale feature fusion efficiency. PANet [

14] introduces another bottom-up path aggregation after the original top-down path of FPN to further enhance the feature hierarchy. Although these algorithms serve as the milestone of object detection in deep learning and increase the object detection of natural images, they can still be further improved and customized for oriented object detection in remote sensing images for UAVs.

The detector head for oriented object detection in remote sensing images plays a significant role in making decisions based on all previously learned feature representations. Remote sensing images include many tiny objects and objects with various scales, so the detection head should be spatially sensitive and robust enough to regress the whole object. A detector’s head structure generally has two purposes: classification and localization. Two commonly used head structures are convolutional heads and fully connected heads, where convolutional heads mainly comprise convolution layers and fully connected heads comprise fully connected layers. Additionally, based on the number of branches, the head structure can be divided into two categories: single-branch head and multi-branch head. Double-branch head [

15] was proposed to demonstrate that fully connected layers are more suitable for object detection and the convolutional layers have more capability for bounding box detection. Although different structures of the detection heads enhance the detection accuracy to a certain extent, a single structure of the detector head is deterministic and could be enhanced by adaptive ensemble techniques.

In this research, we proposed a novel framework for multi-scale feature aggregation and decision aggregation in remote-sensing images. Our framework mainly comprises a multi-scale feature enhancement module, an efficient atrous channel-wise attention mechanism, and a sparsely gated mixture of heterogeneous detection heads module to boost performance. Our framework is evaluated on two popular public datasets and illustrates that it achieves state-of-the-art performance on both datasets.

The contributions of our work can be summarized as follows:

We introduce a novel consolidated multi-scale feature enhancement (CMFEM) module, paired with PAFPN, for advanced feature fusion, refinement, and enrichment. This enhancement scheme boosts traditional feature pyramids by improving feature representation and scale invariance, which is essential for enhancing detection accuracy and reducing erroneous detections.

We propose a novel inter-scale efficient atrous channel attention (EACA) mechanism, which selectively enhances crucial channels of the fused features from our proposed CMFEM. EACA expands the receptive field without losing resolution by utilizing atrous convolution, enriching feature representation, and improving detection accuracy across varying scales.

We introduce an innovative approach featuring a sparsely gated mixture of heterogeneous expert head (MOHEH) modules designed to dynamically aggregate predictions from various detection head architectures. This mechanism enhances detector head performance and efficiency through adaptive gating, dynamically allocating weights for each prediction at a minimal computational cost.

2. Related Work

2.1. Oriented Object Detection of Remote Sensing Images

Recent research in object detection across varying orientations provides critical insights for object detection in remote sensing imagery. Techniques like the RRPN [

16] generate rotated proposals by deploying angled anchors, enhancing detection accuracy but adding computational complexity. To mitigate this, the ROI Transformer [

17] transforms horizontal ROIs to rotated ones, which improves detection accuracy but at a cost to speed. Innovations such as the Gliding Vertex [

18] refine detection by adjusting vertex positions, improving the fit around object orientations. Additionally, the Circular Smooth Label [

19] converts the bounding box regression tasks into a classification framework, effectively handling the periodicity of angles. Techniques like Oriented Reppoints replace traditional bounding boxes and anchors with adaptive points that better capture spatial details crucial for precise detection. Despite these advancements, the high variability of object sizes and orientations in remote sensing still poses significant challenges, highlighting the need for more sophisticated spatial reasoning and robust, scale-invariant features to boost detection performance.

2.2. Attention Mechanism

The attention mechanism in deep learning introduces a form of selectivity that can substantially increase model performance. The Squeeze-and-Excitation Network (SENet) [

20] employs a channel-wise attention mechanism, which weights each channel in the input feature map to emphasize the significant channels while minimizing less important ones, thereby more efficiently grasping the contextual attributes. Later, the convolutional block attention module (CBAM) [

21] sequentially organizes the channel attention and spatial attention, and it introduces the global pooling to capture the global spatial information. Using 1D convolution for efficient, local cross-channel interactions without dimensionality reduction, ECANet [

22] improves convolutional networks and maximizes performance by concentrating on informative features. Attention mechanisms like SENet, CBAM, and ECANet have greatly improved feature extraction methods, allowing for more accurate and contextually aware object detection.

2.3. Multi-Scale Feature Fusion

Typically, the Multi-scale Feature Fusion scheme comprises inputs from the CNN backbone and a pyramid architecture for feature fusion. The deeper level of a neural network contains more semantic information than the shallow layers, and the shallow level contains mainly shape features. This scheme typically integrates the high-level semantic information into the low-level shallow features. FPN [

10] utilizes the top-down feature pyramid structure to combine high-level semantic information with the low-level primitive features. Beyond the top-down path of FPN, PANet [

14] uses an additional bottom-up path to a further stage of feature fusion. NAS-FPN [

23] utilizes neural architecture search to configure the topology of the feature network autonomously. Bi-FPN [

24] is a novel architecture used within the EfficientDet. It employs a weighted bi-directional FPN architecture for effective and quick fusion of multi-scale features. By appending extra feedback links from the feature pyramid to the backbone’s bottom-up layers, Recursive-FPN [

25] facilitates more thorough feature integration and enhancement. However, while these multi-scale fusion techniques are widely applicable, customizing additional modules to suit remote sensing scenarios better could significantly enhance detection performance.

2.4. Mixture of Experts

The Mixture of Experts (MoE) methodology significantly advances ensemble machine learning, particularly impacting large-scale language models through its principle of conditional computation. This approach divides the network into specialized "experts," each handling specific input types, activating only relevant ones based on the input’s characteristics to enhance computational efficiency. Shazier et al. [

26] demonstrated a sparsely gated network that handles extensive weights with minimal computation during testing. MoE has been successfully integrated into machine translation, managing over 600 billion parameters effectively [

26], and employed in frameworks like Glam [

27]. By integrating MoE into its architecture, the Switch Transformer [

28] reduces training costs and simplifies architecture while accelerating pre-training and boosting performance across NLP tasks. The "divide and conquer" strategy of MoE enhances model efficiency and effectiveness by focusing expertise where most needed, optimizing resources, and improving accuracy across diverse applications.

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Pipeline

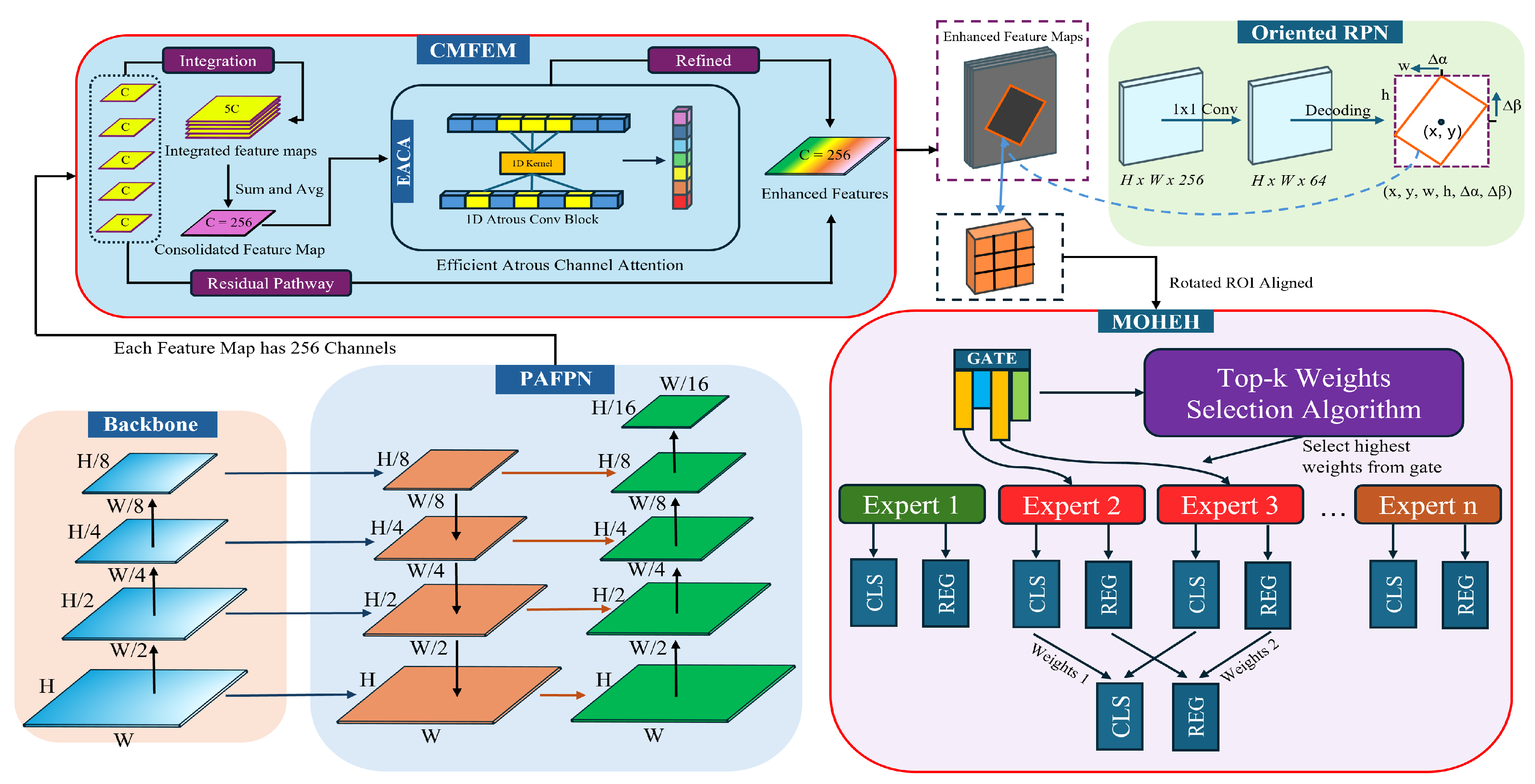

Figure 1 illustrates the innovative architecture of our proposed system tailored for the amalgamation of multi-scale features and the augmentation of decision-making capabilities. This framework builds upon the baseline model Oriented R-CNN, integrating our innovative contributions: the consolidated multi-scale feature enhancement module (CMFEM), the efficient atrous channel-wise attention (EACA), and the sparsely gated mixture of heterogeneous experts head (MOHEH) module. The CMFEM is paired with the Pyramid Attention Feature Pyramid Network (PAFPN), and it is composed of multi-scale feature integration, inter-stage channel-wise attention, and a residual aggregation with the original features. This module plays an essential role in the multi-scale refinement and fusion of hierarchical feature representations. Meanwhile, the MOHEH module advances the decision aggregation process by deploying diverse expert head structures for nuanced class-specific and regression predictions, embodying the essence of a sparsely gated mixture of experts approaches.

The architecture utilizes the ResNet backbone, and we identify feature maps at different hierarchical levels from C2 to C5 in a bottom-up sequence. The output from the backbone feeds into the PAFPN, which will scale the channel number for each feature map to 256. The output from PAFPN will be the input of CMFEM, which harmonizes all levels of feature maps to a uniform scale through either downsampling or upsampling. Resizing to intermediate scales preserves most of the original features during resizing. Once the features are fused, we introduce the EACA channel-wise attention module to enhance the model by adaptively refining the multi-level fused features originating from PAFPN’s outputs. The EACA module strategically accentuates critical aspects of the features, thus improving feature representation. For decision-making, the MOHEH module uses a top-k gating mechanism to aggregate results from various detection head structures selectively. This innovative and intuitive design integrates class and regression predictions through a mixture of experts’ approaches, markedly boosting the model’s prediction accuracy.

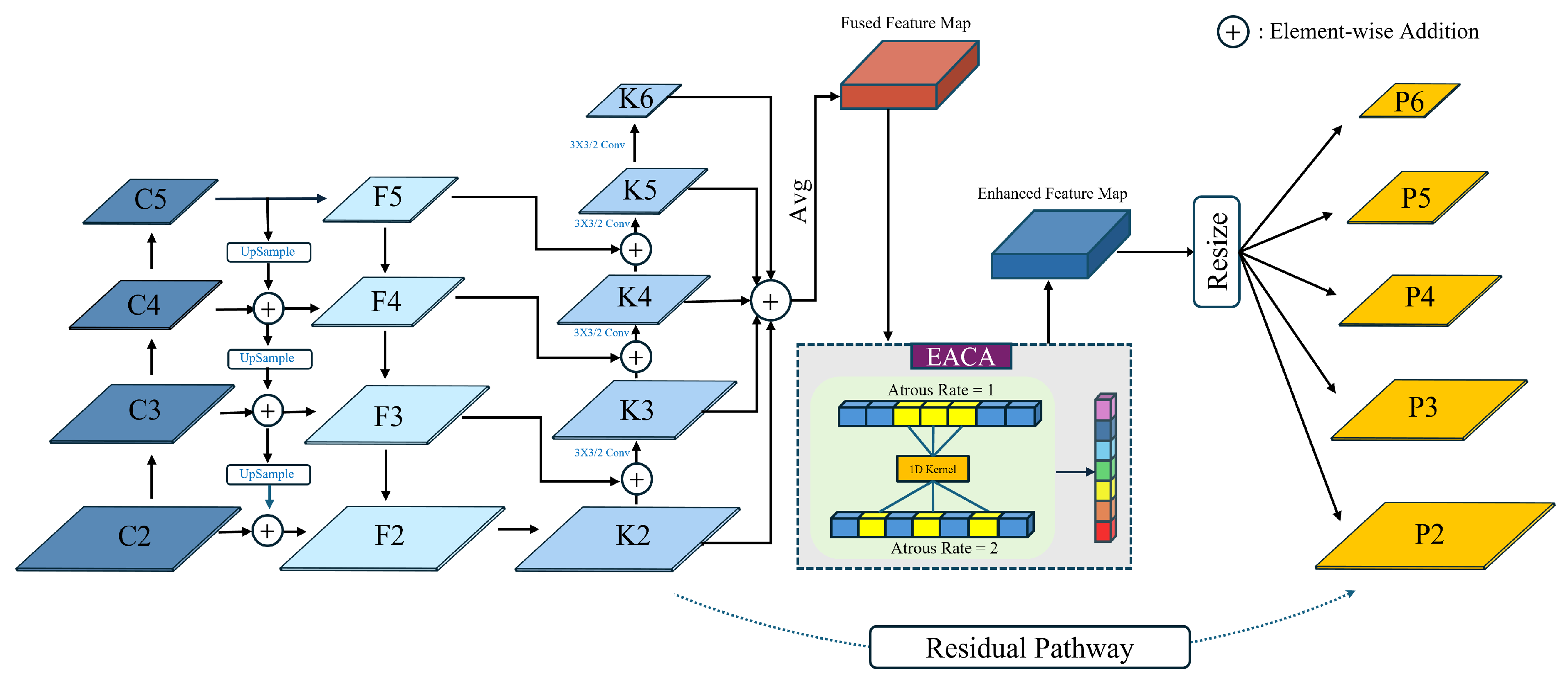

3.2. Consolidated Multi-scale Feature Enhancement Module

The FPN was adopted in the baseline model to enhance and fuse the multi-scale feature representation. Because remote sensing images contain objects of various scales, we conjecture that the single top-down pathway will not adequately capture such data’s diverse and complex spatial hierarchies. As FPN, PAFPN also has a similar top-down pathway to aggregate feature representation learned by the CNN backbone, and it includes another bottom-up feature aggregation pathway in addition to the top-down fusion pathway to augment the feature representation further. Therefore, we replace the original FPN structure with PAFPN in the baseline model and observe an mAP gain immediately after the replacement.

Although the replacement of PAFPN with the FPN enhances the detection performance in Oriented RCNN detector, it still has the following limitations and can be further improved:

(1) The fusion strategy of PAFPN is not that customized for remote sensing images. There are lots of objects with various scales and shape in remote-sensing images, so it is necessary to further augment the fusion process of each feature level to capture finer details and semantic details.

(2) The fusion process does not fully exploit each scale, which hinders the model’s ability to improve the multi-scale information intrinsic to remote-sensing images.

(3) Inadequate exploration of feature correlations across multiple scales.

Therefore, we propose a novel CMFEM to aggregate and augment the multi-scale features from the PAFPN’s output, and

Figure 2 presents the comprehensive architecture of CMFEM, which has the following three major improvements:

(1): Following top-down and bottom-up feature aggregation, we incorporate a feature fusion step to fuse feature maps from all scales.

(2): We introduce an efficient and computational-friendly channel attention module, adept at extracting inter-scale correlations and effectively harnessing multi-scale contextual information.

(3): To preserve the original feature representation acquired by PAFPN, we integrate a residual pathway, maintaining the valuable feature representation learned throughout the network.

For feature maps

(for

), we define resizing operations

that use nearest neighbor interpolation (NNI) or adaptive max pooling (AMP) to match the scale of

and then convolution to modify channel dimensions. Specifically,

Here, NNI denotes nearest neighbor interpolation and AMP denotes adaptive max pooling. The factor

represents the scaling parameter necessary to match the spatial dimensions of

. Each transformation is designed to align the feature map sizes with

while maintaining crucial spatial and feature details. The transformed maps

are then aggregated to form

which undergoes further processing in the EACA module to enhance essential channels. The output

Q from the EACA is adjusted for spatial dimensions to match

through upscaling or downscaling as

and the final feature maps are computed as

ensuring coherent feature integration and enhancement across scales.

3.2.1. Efficient Atrous Channel-Wise Attention

Our proposed approach leverages a novel channel-wise attention module inspired by the Efficient Channel Attention Network (ECANet) to streamline multi-scale feature fusion and reduce redundancy, improving our detection framework’s efficacy. The efficient atrous channel-wise attention (EACA) module selects features by generating the channel-wise feature descriptors and focusing on essential channels, as shown in

Figure 3.

Suppose X is the input feature map, which is denoted as

. The feature descriptors

p and

q are obtained using global average and max pooling operations. They can be expressed mathematically as follows:

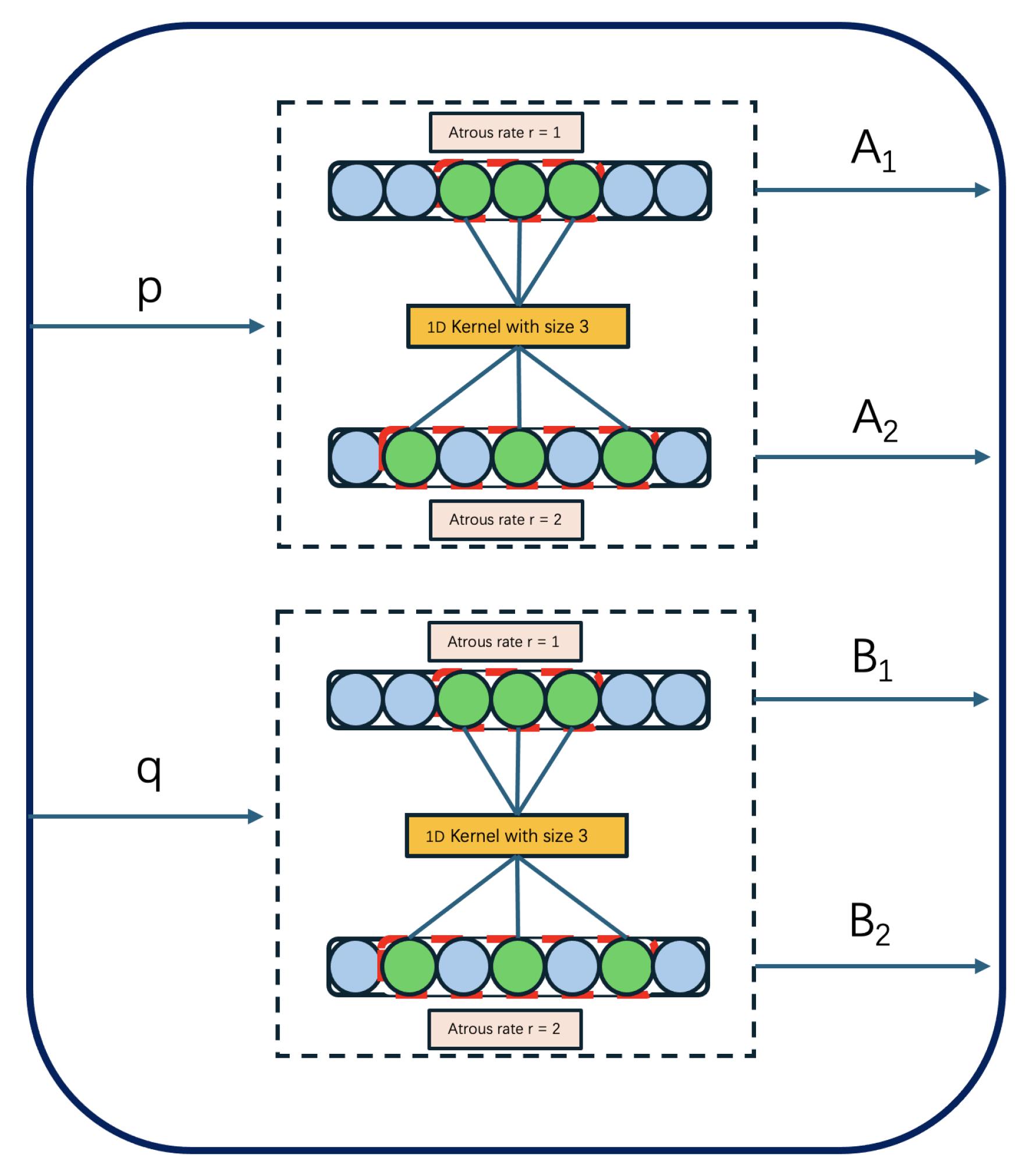

The inter-enhancement module is show in

Figure 4. Each descriptor is then processed through a set of 1D atrous convolutions, each specified by a unique atrous rate:

where

D is the total number of atrous rates used and

is the specific atrous rate for the

k-th convolution.

The outputs from these convolutions,

and

, are then summed to form the enhanced feature sets

and

:

The combined features are processed through a sigmoid activation function to compute the attention weights

:

Finally, these attention weights modulate the input feature map

X to produce the enhanced output feature map

:

In the schematic of the Inter-Enhancement Module, the average-pooled and max-pooled feature vectors

p and

q derived from the input feature map will be fed into a specialized sequence of atrous convolutions module to generate the sets

and

.

Figure 4 presents a visualization of the inter-enhancement module, utilizing atours convolution with atrous rate 1 and 2. To create the feature vectors

and

, respectively,

p is passed through two one dimensional convolutional layers, each has a kernel size of 3. The atrous rate of one layer is 1, while the atrous rate of the other layer is 2. A comparable pair of atrous convolutions are applied to

q to provide

and

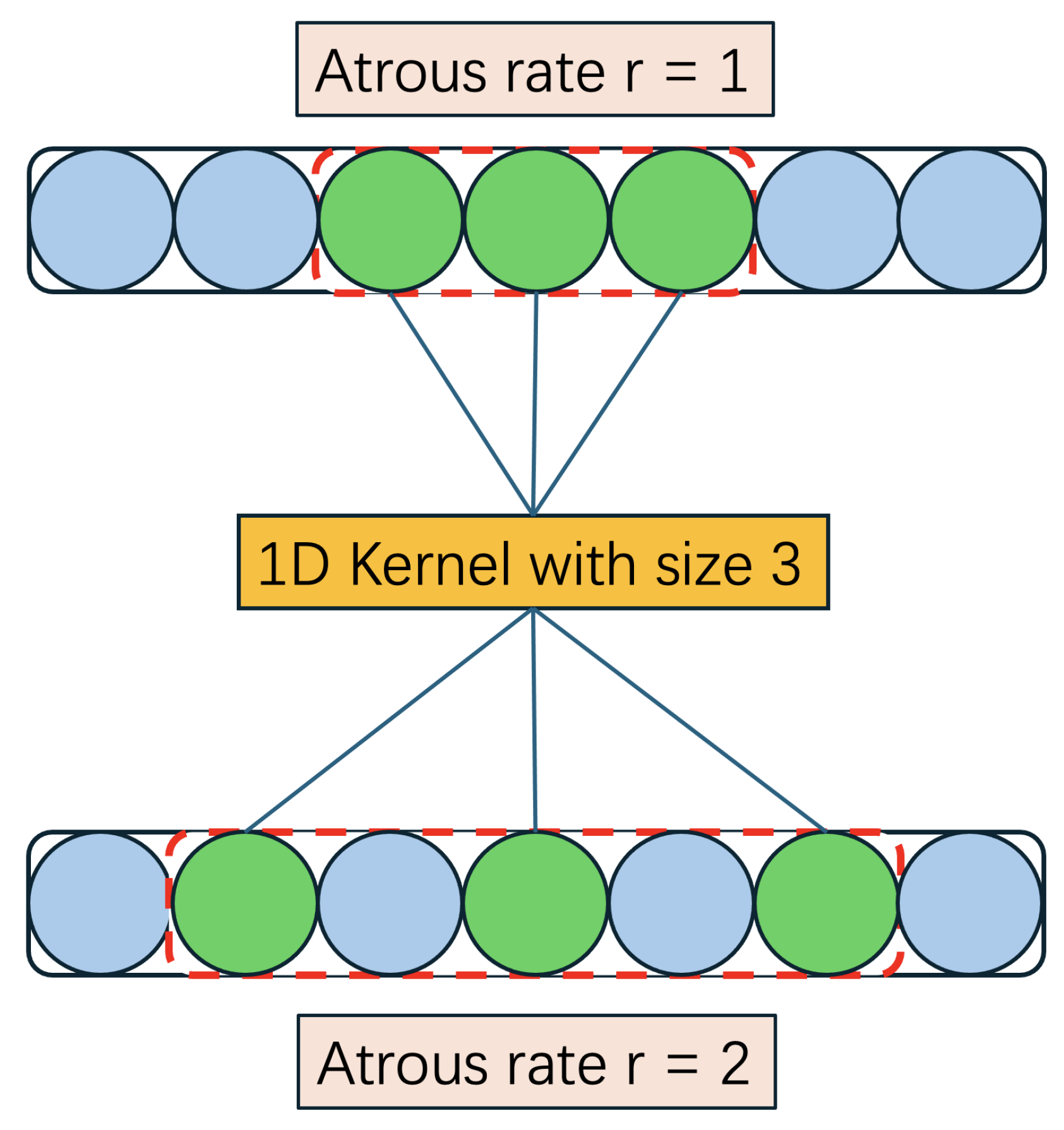

. When the atrous rate equals to 1, it is equivalent to an ordinary convolution, and this is for maintaining the original fine-grained feature representation. The atrous convolution layers allow the module to capture information at multiple scales, and they will effectively expand the receptive field without introducing extra computational costs.

Figure 5 presents a visualization of the one-dimensional atrous convolution. One-dimensional atrous convolution is an adaptation of the conventional convolutional operation that aims to increase the receptive field in sequential data without introducing computational overheads. These convolutions effectively capture long-range relationships while preserving the length of the sequence by adding gaps between the standard convolutions. Such capabilities make atrous convolutions essential for improving feature extraction in sequence modeling tasks, enabling more effective learning from data with complex dynamics. The input to the inter-enhancement module will be one-dimensional average-pooled and max-pooled features, which can be considered as a form of sequential feature representation. Therefore, we can utilize the one-dimensional atrous convolution to expand our model’s capability to integrate contextual information across various scales. Because the average-pooled and max-pooled features are from fused feature maps, we can efficiently leverage the one-dimensional convolution to differentiate the salient and non-salient signals across these fused feature descriptors. The spaced kernels of atrous convolution provide a broader view of the input features, and this is crucial for processing fused feature maps, as it helps to preserve and highlight pivotal features that might be diluted during the feature fusion process. Consequently, one-dimensional atrous convolution can not only maintain the integrity of the significant features but also augment the model’s capability to interpret sophisticated patterns and anomalies within the data, and that is why we choose to use the atrous convolution in the Inter-enhancement module.

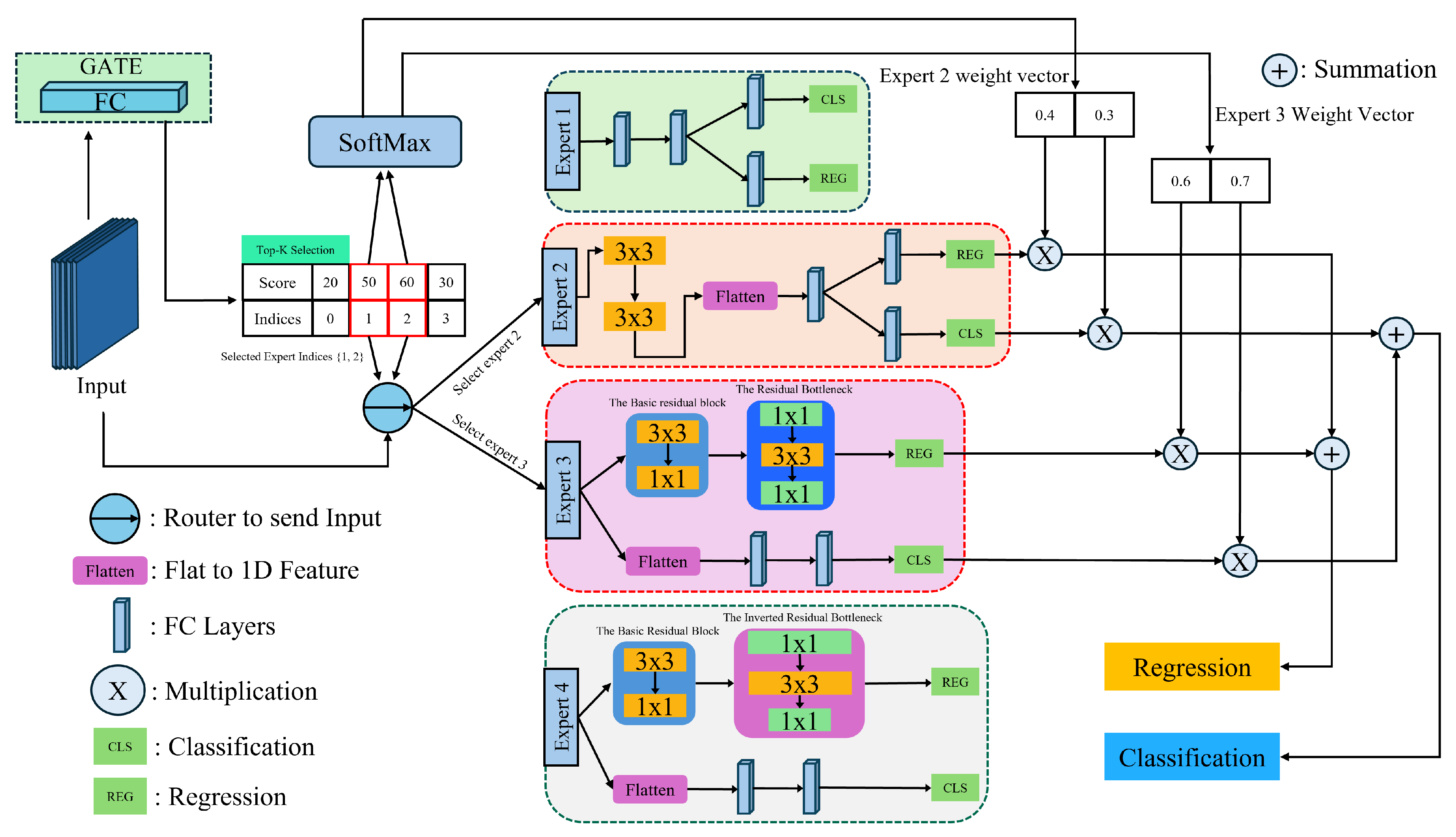

3.3. Sparsely-Gated Mixture of Heterogeneous Head

In object detection of the remote sensing images, the detector head is one of the most pivotal modules of a model, because it directly conducts evaluations on the learned feature representation from the previous block of the network. This assessment is of great importance as it determines the overall accuracy and efficiency of detecting objects across various scales in remote sensing images. Taking account of the diverse scale and orientation of objects in remote sensing images, the detector head should be highly flexible and accurate in classification and localization, and this will guarantee that the learned spatial feature representation and semantic information are efficiently employed. Besides that, the intricacy of the remote sensing images, which includes changes of lightning or background with severe noises, requires the detector head to be adaptive to such variabilities. To overcome such variabilities, we take advantage of not only the regular single-branch head structures but also customized double-branch structures, while using the Mixture of Experts (MoE) methodology to adaptively and selectively choose the best-performing head structures. The incorporation of the MoE selections mechanism significantly enhances the robustness and performance of our proposed detector.

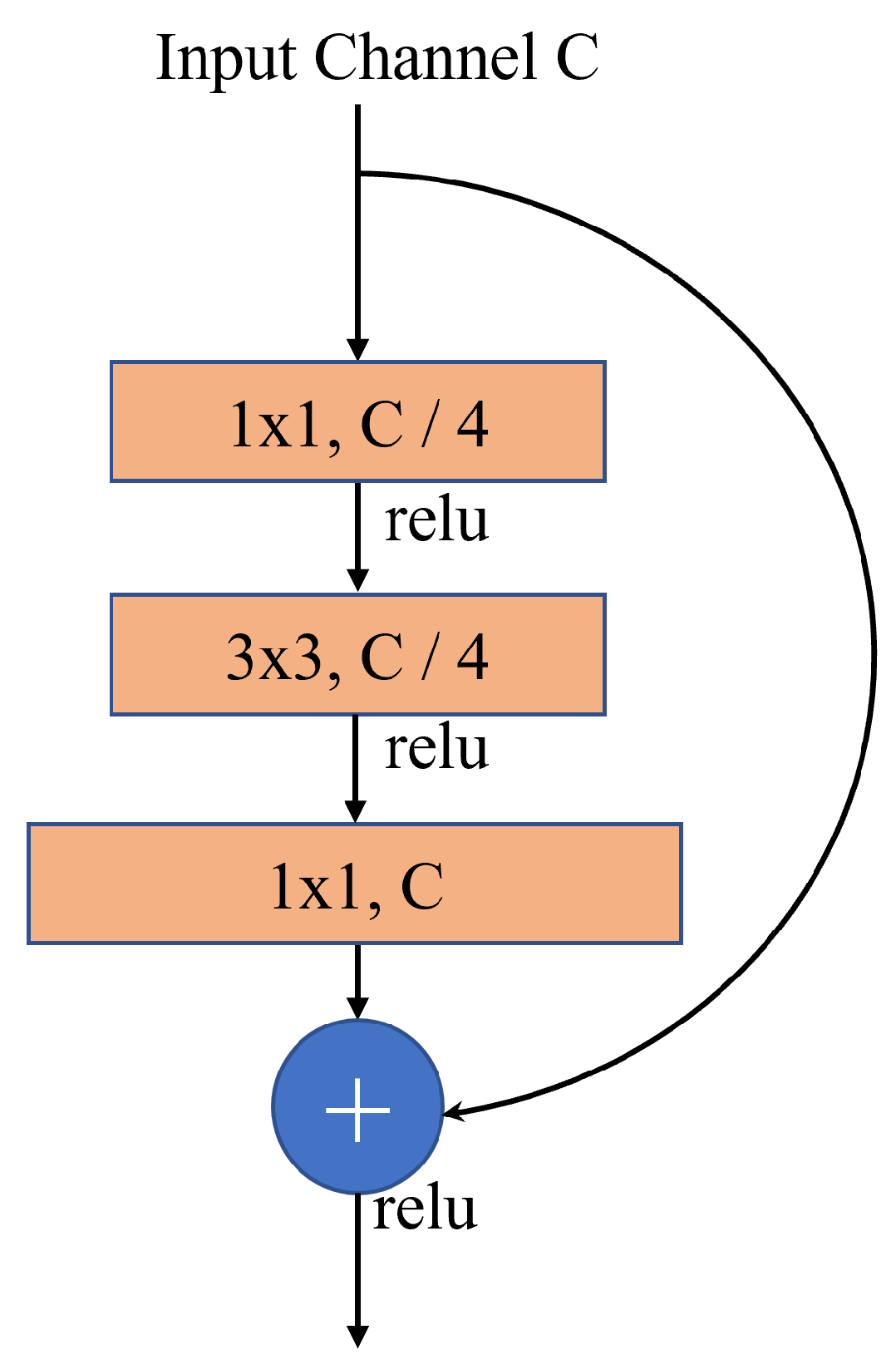

3.3.1. Residual Double Head Structure

Double-Head R-CNN [

15] has emerged as a trending detector head module that has achieved a notable improvement in object detection tasks, gaining +3.5% and +2.8% AP on MS COCO dataset[

29] from Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) baselines. RCNN-based detectors commonly employ two types of head structures for classification and localization tasks: head with mainly fully-connected layers and head with mainly convolutional layers. In double-Head R-CNN architectures, a detector head that comprises two branches, where one branch mostly includes fully connected layers and the other branch primarily includes convolutional layers, demonstrates better performance than the single-branch head structure. This improved architecture demonstrates that the convolutional branch is more appropriate for the localization requirement, and the fully connected branch is more capable of classification tasks. Labeled as "Expert 1" in

Figure 6, the original detector head in the Oriented RCNN consists of a single branch with two fully connected layers; this arrangement does not consider the classification and the localization advantage. We propose a mixed convolution and linear layer structure for the single-branch enhancement, labeled "Expert 2" in

Figure 6, consisting of two 3x3 convolutions and one fully connected layer on a single branch. Additionally, our customized Double-head RCNN structure is depicted in

Figure 6 as "Expert 3" and "Expert 4". It comprises a branch of FC layers for classification and a branch with convolutional blocks for bounding box regression. The double head’s convolutional module comprises a basic residual block, and a residual bottleneck in

Figure 7 or a inverted residual bottleneck in

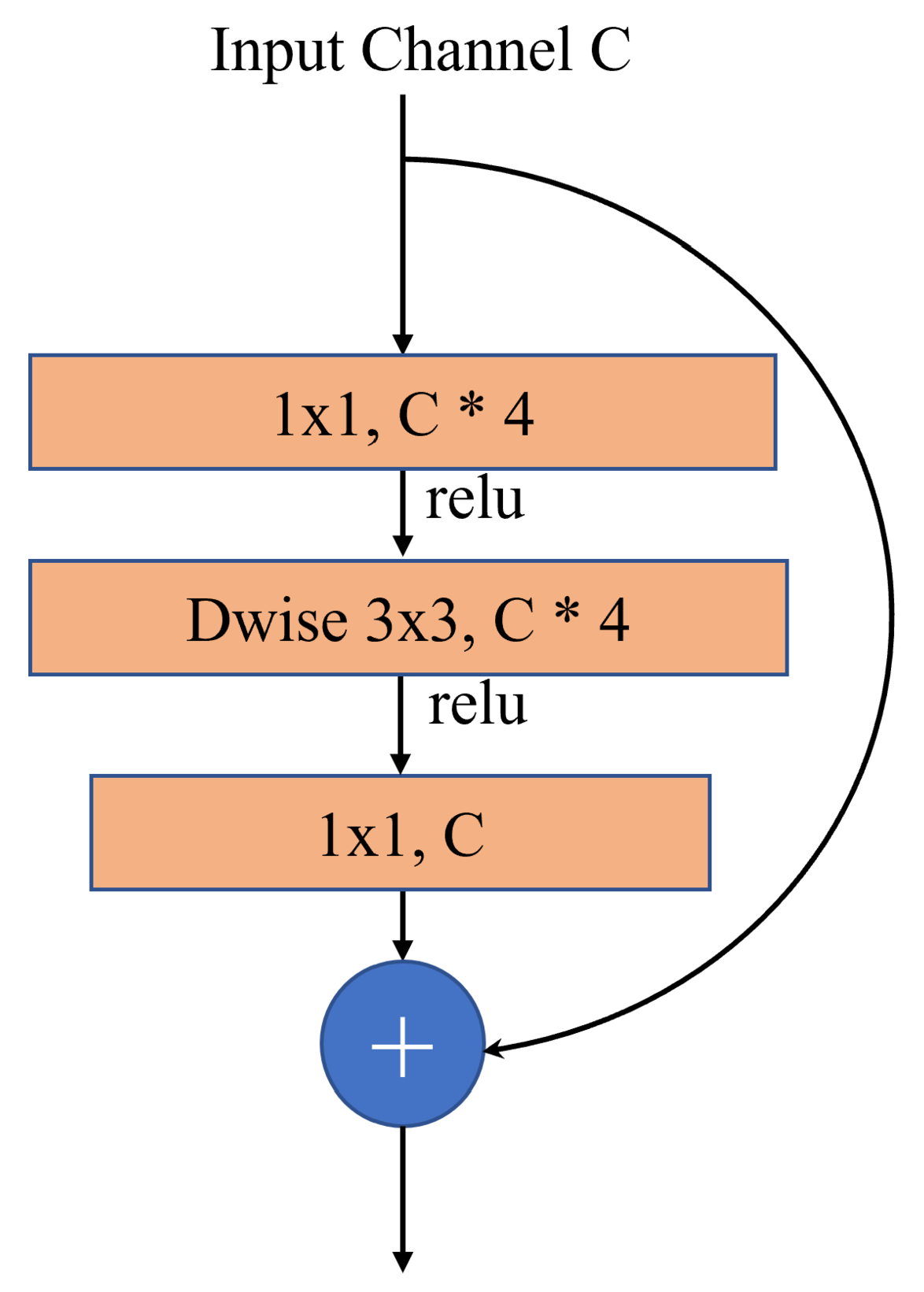

Figure 8. A basic residual block comprises a 3x3 conv layer and a 1x1 conv layer. The detection performance demonstrates that the FC branch is more adept at classification due to its higher spatial sensitivity, which is crucial for distinguishing between whole and partial objects in remote sensing images. On the other hand, the conv branch adds a stack of residual blocks to improve feature learning capabilities significantly without incurring too much computational overhead.

3.3.2. Sparsely-Gated Mixture of Expert Heads

In our study, we introduce a novel architecture called the Sparsely-gated Mixture of Detector Heads. As depicted in

Figure 6, the workflow begins with an ROI-aligned Input Feature Map with 256 channels and a spatial dimension of 7x7. This input is first flattened, resulting in a vector of 12,544 dimensions, which is then processed through a gating network. The gate’s role is to dynamically select and activate the relevant detector heads based on the input, optimizing both the processing efficiency and the task-specific performance of the model. This strategy embodies the MoE’s fundamental objective of enhancing model flexibility and computational efficiency through targeted activation of neural network segments.

Our proposed Mixture of Experts(MoE) Layer is composed of n "expert networks," denoted

,...,

, and a "Gating network" g that outputs an n-dimensional vector. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the experts are of different structures mentioned in the previous section, and each of them outputs the same: the class prediction and the regression prediction. For a given input x, let

(x) and G(x) represents the output of the i-th expert and the output of the gating network. Initially, the gating network computes a set of scores that determine the relevance of each expert for a given input. The scores for each expert

i are computed as:

where

represents the weight vector,

the bias, and

the input feature vector. Based on these scores, we use a top-k selection mechanism to choose the experts. The top-

k gating mechanism activates only the top

k experts based on their scores. The indices of the top-

k experts are chosen, and the gating outputs for these experts are normalized by SoftMax, as show in equation

18 below:

where

denotes the indices of the top-

k selected experts.

Finally, each expert network

provides two outputs: a classification (

) and a regression (

) prediction. The final aggregated outputs for the classification and regression are computed as weighted sums of the respective outputs from the selected experts, using the gating outputs as weights::

4. Results

4.1. Datasets

DOTA-v1.0 [

30] dataset: The DOTA is a large dataset for oriented object detection, comprised of 2806 aerial images. 1411 images are employed for training, 937 images for validation, and the remaining 458 images at the time within testing. The resolution value of the DOTA dataset ranges from 800 * 800 to 4000 * 4000 pixels, with an average size of 2000 * 2000 pixels. For training, we utilize both the training set and the validation set, and we use the remaining images for testing set. Image annotations are provided in the XML and text format. The following are the categories and their respective abbreviations: Ground track field (GTF), Soccer-ball field (SBF), Plane (PL), Tennis court (TC), Harbor (HA), Small vehicle (SV), Baseball diamond (BD), Swimming pool (SP), Helicopter (HC), Ship (SH), Basketball court (BC), Roundabout (RA), Large vehicle (LV), Bridge (BR), and Storage tank (ST).

HRSC2016 [

31] is a dataset designed for ship detection tasks, featuring high-definition imagery sourced from six harbors around the globe. It encompasses a total of 1061 images, whose dimensions vary from 300 by 300 to 1500 by 900 pixels. The dataset is divided into three sets: 436 images for training purposes, 181 for validation, and 444 for testing. Each ship object within the dataset is annotated using Oriented Bounding Boxes (OBB), and the considerable diversity in the sizes of the ships presents a notable difficulty for precise object detection.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

In this study, we employ two principal metrics to assess the model’s performance: mean Average Precision (mAP) and Frames Per Second (FPS). FPS measures the detection speed of the model, indicating the number of images processed per second. A greater FPS value demonstrates better detection capabilities. mAP is used to gauge the accuracy of object detection models across various object classes and is defined as the mean of Average Precision (AP) scores across all categories:

where

C represents the total number of object categories, and

is the average precision for the

cth category. AP summarizes the precision-recall curve as the weighted mean of precisions achieved at each threshold, with the increase in recall from the previous threshold used as the weight:

Precision (P) and Recall (R) are key components in evaluating detection tasks:

Here, , , and stand for true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. These metrics effectively measure the model’s accuracy and ability to detect objects accurately across different scenarios.

4.3. Implementation Detail

The experiments were conducted on a server with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070Ti GPUs, running Ubuntu 22.04, Python 3.8, and Pytorch 1.7. Our models, developed using the MMDetection framework, utilized a Resnet backbone pre-trained on ImageNet and fine-tuned on cropped 1024x1024 pixel patches from the high-resolution DOTA dataset, with horizontal and vertical flipping for data augmentation. We merged the training and validation sets for DOTA, used a batch size of 2, optimized with SGD (momentum: 0.9, weight decay: 0.0001), and an initial learning rate of 0.005, decreasing linearly after the seventh epoch of twelve total. For HRSC2016 dataset, a total of 36 epochs are used for training. The starting learning rate is 0.005.

4.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Detectors

In this section, we conduct a series of experiments on DOTA and HRSC2016 to demonstrate the effectiveness of our detector. Our baseline and proposed models adopt the same parameter configuration mentioned in the previous section to ensure a fair comparison. In addition, since the training of baseline model utilizes both the training set and the testing set, we apply the same training procedure to ensure fairness. The complete comparison results for DOTA are shown in

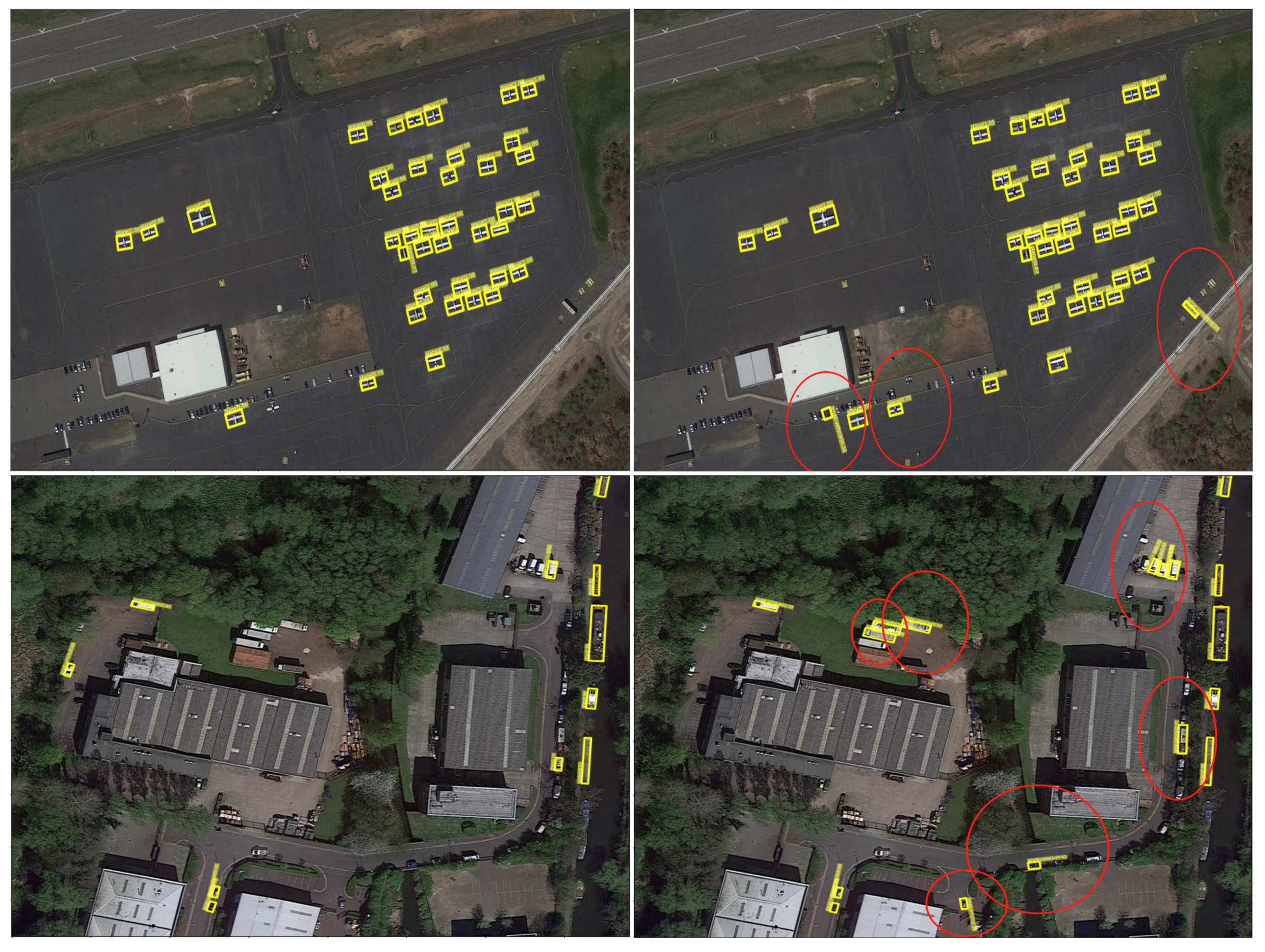

Table 1. All models were trained and tested under uniform conditions using the same parameter configurations. We first demonstrate the overall performance of the FAMHE-Net and showcase the enhancement of our proposed framework. We achieved the best and second-best results for most categories compared to other detectors, and our detector improved mAP on DOTA by 0.9%. Then, in the next few sections, we append each proposed module to our baseline model to perform the ablation study and demonstrate that each of our proposed modules is crucial for augmenting the overall detection performance, thereby illustrating the advantage of our FAMHE-Net.

Table 2 shows the results of different state-of-the-art object detection methods on the HRSC2016 dataset, with the mAP07 and mAP12 as the evaluation metrics. According to the mAP07 and mAP12 results, we demonstrate that our proposed framework achieves higher detection accuracy. The "backbone" column indicates the name of the feature extraction network and its corresponding number of layers. Results from

Table 2 illustrate that our proposed framework with only an R-50 backbone network achieves a mAP07 of 90.70 and mAP12 of 97.70, which are +0.34% and +1.30% higher than the baseline model.

4.5. Ablation Study

4.5.1. Effectiveness of the CMFEM

Our baseline detection framework utilizes the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) as the neck architecture for multi-scale feature fusion. Experimental results are comprehensively summarized in

Table 3. For the HRSC2016 dataset, the evaluation metrics employed are mAP07 and mAP12, while for the DOTA dataset, mAP is used. As demonstrated in

Table 3, we initially substitute FPN with PAFPN, which results in improvements on both datasets. Subsequently, we integrated our proposed CMFEM atop PAFPN to assess its efficacy. The CMFEM encompasses several components, including multi-scale feature fusion, a residual pathway, and an efficient atrous channel-wise attention (EACA) module.

Figure 9.

Visualization of the CMFEM on the DOTA dataset. The columns from left to right are the original images, the feature map before CMFEM and the feature map after CMFEM, respectively.

Figure 9.

Visualization of the CMFEM on the DOTA dataset. The columns from left to right are the original images, the feature map before CMFEM and the feature map after CMFEM, respectively.

In

Table 3, we conduct an ablation study examining various combinations of neck structures integrated into the overall detector architecture. Specifically, employing only the feature fusion component of the CMFEM—merely fusing the multi-scale outputs from PAFPN and then scaling back the fused feature to the detector head—yielded a modest increase in detection accuracy across both datasets. Including the residual pathway further augmented detection performance, underscoring the significance of retaining original feature representations for enhanced accuracy. The addition of the EACA, our proposed channel-wise attention module, led to significant performance gains. The replacement of FPN with PAFPN and addition of CMFEM achieves an overall increase of 0.22% in mAP07, an increase of 0.8% in mAP12 for the HRSC2016 dataset, and an increase of 0.58% in mAP for the DOTA dataset. The performance improvement for the channel-wise refinement demonstrates that focusing on selective feature enhancement through channel-wise attention mechanisms can substantially amplify the detection model’s ability to discriminate and recognize the crucial context of the fused features. To determine the optimal atrous rate for the inter-enhancement block within the EACA module, we conduct experiments to assess the impact of different numbers of atrous convolutions on feature representation across various receptive fields. We used an atrous rate of one as our baseline for comparison, where the convolution operation mimics a standard convolution. Specifically, for the DOTA dataset, incorporating the EACA module with multi-scale feature fusion and the residual pathway led to a significant enhancement in mAP, detailed further in

Table 4. Our experimental findings indicate that an atrous rate configuration of (1, 2) improves the mAP significantly, while a configuration of (1, 2, 3) yields an even greater increase in mAP. Similarly, for the HRSC2016 dataset, employing different sets of atrous rates improved the baseline performance. The configuration of (1, 2) led to mAP improvement, and extending this to (1, 2, 3) gains a greater amount than the (1, 2) setup. For (1, 2, 3, 4) setup, the performance decreases, and we conjecture that this is caused by a light extent of over-fitting. Therefore, we choose the (1, 2, 3) setup after considering the performance on two datasets.

As demonstrated by our experiments, the optimal configuration of atrous rates for the inter-enhancement block was (1, 2, 3). This configuration involves average-pooled and max-pooled features being processed through three distinct convolutions at atrous rates of 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This approach significantly enhances the extraction and integration of contextual information, optimizing the overall feature enrichment facilitated by the CMFEM. These findings are essential in the refinement stage of multi-scale feature fusion and enhancement, ensuring our model achieves robust and high-performing detection capabilities across diverse imaging scenarios.

4.5.2. Effectiveness of Mixture of Heterogeneous Head

In

Table 5, we initially evaluate and compare various head structures, focusing on their detection accuracies. The results indicate that the double-head structure outperforms the single-head setup. This finding supports our hypothesis that convolution layers are more adept at regression tasks, while linear layers excel in classification tasks.

Further detailed in

Table 5, we observe a notable improvement in mAP with the implementation of advanced head structures: the double-branch residual head structure shows an +0.27% improvement in mAP, and the double-branch inverted-residual head structure exhibits an 0.22% increase in mAP. To balance performance enhancements with computational efficiency, both the residual and the inverted residual head structures incorporate one basic residual block and one bottleneck block in the convolutional branch, slightly increasing the computational cost but considerably boosting the detection performance.

Our novel MOHEH module introduces two critical hyper-parameters: the number of experts, k, and the number of selected experts, n. After evaluating each head structure individually, we implement gating for each structure with n = 4, k = 1 to k = 4.

Table 6 presents the experimental result of MOHEH modules with different hyper-parameters. After applying the MoE, we can see that the parameters are doubled compared to the baseline models, significantly enlarging the model size and enhancing the capacity for specialized learning and adaptability across classification and regression tasks. We can see that the Parameters are the optimal performance is obtained when n = 4 and k = 2, which enhanced the mAP by 0.79%. For k = 3 and k = 4, we can see that although the model performance remains better than the baseline, there is a noticeable decrease in FPS due to the increased number of experts required for each input. Specifically, when k=4, the input feature will pass through all 4 experts, which means the results of all experts will be combined. Due to the inclusion of residual convolutional blocks in the double-branch experts, activating all 4 experts in each iteration introduces additional computational cost, which in turn lowers the FPS. Additionally, considering the complex input feature representation and model simplicity, we employ a fully connected layer designed to adaptively select experts based on the top-k selection algorithm for the gating mechanism, thereby enhancing the module’s effectiveness in various detection scenarios.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the baseline and the improved detector on DOTA. The left column includes the baseline detection results, and the right column includes our proposed FAMHE-NET detection results. All newly detected areas have been circled in red.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the baseline and the improved detector on DOTA. The left column includes the baseline detection results, and the right column includes our proposed FAMHE-NET detection results. All newly detected areas have been circled in red.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the baseline and the improved detector on HRSC2016. The left column includes the baseline detection result, and the right column includes our proposed FAMHE-NET detection result.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the baseline and the improved detector on HRSC2016. The left column includes the baseline detection result, and the right column includes our proposed FAMHE-NET detection result.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we introduced FAMHE-Net, an innovative framework specifically designed for detecting oriented objects in aerial images, particularly within the context of remote sensing. Our framework addresses challenges such as low resolution, diverse scale variations, noisy backgrounds, and arbitrary object orientations. Not only does it outperform the baseline model, but it also provides robust solutions to these complex issues. FAMHE-Net integrates several novelties, including a multi-scale feature augmentation module (CMFEM), an Efficient Atrous Channel-wise Attention (EACA) Module within CMFEM, and a sparsely-gated mixture of heterogeneous experts detection head (MOHEH). The CMFEM enhances feature representation across different feature hierarchies, the EACA module accentuates critical regions of the fused features, and the MOHEH module leverages these enriched features for adaptive, precise predictions. We validate our framework on multiple remote sensing datasets and scenarios, demonstrating that our approach significantly improves the accuracy of oriented object detection in aerial images while maintaining efficiency and minimal computational cost. This conclusion affirms the effectiveness of integrating multi-scale feature augmentation with attention mechanisms and decision aggregation for analyzing images captured by UAV optical sensors, setting a new benchmark for future research in aerial object detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yixin Chen; Formal analysis, Yixin Chen; Funding acquisition, Weilai Jiang; Investigation, Yixin Chen; Methodology, Yixin Chen; Project administration, Yaonan Wang; Resources, Yaonan Wang; Software, Yixin Chen; Supervision, Weilai Jiang; Validation, Yixin Chen; Visualization, Yixin Chen; Writing – original draft, Yixin Chen; Writing – review & editing, Yixin Chen.

Funding

This research was supported by the General Project of Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province under Grant 2022JJ30162, the Project of Natural Science Foundation Youth Enhancement Program of Guangdong Province under Grant 2024A1515030184, and the Project of Guangzhou city Zengcheng District Key Research and Development under Grant 2024ZCKJ01.

Data Availability Statement

For all source data and code, please contact us: yixinchen@hnu.edu.cn

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the constructive comments and suggestions of the anonymous reviewers, which have greatly helped to improve this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Yao, H.; Qin, R.; Chen, X. Unmanned aerial vehicle for remote sensing applications—A review. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Niu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, T.; Mei, S.; Jubair, A. Global to local: A scale-aware network for remote sensing object detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 779–788.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 7263–7271.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.10934 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. Yolox: Exceeding yolo series in 2021. 2021, arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.08430 arXiv:2107.08430.

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2961–2969.

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 2117–2125.

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2980–2988.

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhang, W. Scale-equalizing pyramid convolution for object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020, pp. 13359–13368.

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2017, Vol. 31.

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 8759–8768.

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Fu, Y. Rethinking classification and localization for object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 10186–10195.

- Ma, J.; Shao, W.; Ye, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Xue, X. Arbitrary-oriented scene text detection via rotation proposals. IEEE transactions on multimedia 2018, 20, 3111–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Long, Y.; Xia, G.S.; Lu, Q. Learning RoI transformer for oriented object detection in aerial images. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 2849–2858.

- Xu, Y.; Fu, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Xia, G.S.; Bai, X. Gliding vertex on the horizontal bounding box for multi-oriented object detection. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2020, 43, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J. Arbitrary-oriented object detection with circular smooth label. Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part VIII 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 677–694.

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 7132–7141.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 3–19.

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 11534–11542.

- Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.Y.; Le, Q.V. Nas-fpn: Learning scalable feature pyramid architecture for object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 7036–7045.

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 10781–10790.

- Qiao, S.; Chen, L.C.; Yuille, A. Detectors: Detecting objects with recursive feature pyramid and switchable atrous convolution. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 10213–10224.

- Shazeer, N.; Mirhoseini, A.; Maziarz, K.; Davis, A.; Le, Q.; Hinton, G.; Dean, J. Outrageously large neural networks: The sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer. arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.06538 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Du, N.; Huang, Y.; Dai, A.M.; Tong, S.; Lepikhin, D.; Xu, Y.; Krikun, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, A.W.; Firat, O. ; others. Glam: Efficient scaling of language models with mixture-of-experts. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022, pp. 5547–5569.

- Fedus, W.; Zoph, B.; Shazeer, N. Switch transformers: Scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 23, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13. Springer, 2014, pp. 740–755.

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 3974–3983.

- Liu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Weng, L.; Yang, Y. A high resolution optical satellite image dataset for ship recognition and some new baselines. International conference on pattern recognition applications and methods. SciTePress, 2017, Vol. 2, pp. 324–331.

- Zhang, G.; Lu, S.; Zhang, W. CAD-Net: A context-aware detection network for objects in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 10015–10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Ren, Y.; Sheng, K.; Dong, W.; Yuan, H.; Guo, X.; Ma, C.; Xu, C. Dynamic refinement network for oriented and densely packed object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 11207–11216.

- Wei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, X. Oriented objects as pairs of middle lines. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 169, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Guo, Z.; Sun, X.; Fu, K. Scrdet: Towards more robust detection for small, cluttered and rotated objects. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 8232–8241.

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Feng, Z.; He, T. R3det: Refined single-stage detector with feature refinement for rotating object. Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2021, Vol. 35, pp. 3163–3171.

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Xia, G.S. Align deep features for oriented object detection. IEEE transactions on geoscience and remote sensing 2021, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, W.; Ren, Q. R4 Det: Refined single-stage detector with feature recursion and refinement for rotating object detection in aerial images. Image and Vision Computing 2020, 103, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Oriented R-CNN for object detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 3520–3529.

- Jiang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Fu, P.; Luo, Z. R2CNN: Rotational region CNN for orientation robust scene text detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.09579 2017. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of FAMHE-Net. FAMHE-Net is composed of a backbone, a fine-grained feature pyramid network, a feature fusion and enhancement module, a novel channel-wise attention mechanism, and a sparsely-gated mixture of heterogeneous detection head module.

Figure 1.

The overall architecture of FAMHE-Net. FAMHE-Net is composed of a backbone, a fine-grained feature pyramid network, a feature fusion and enhancement module, a novel channel-wise attention mechanism, and a sparsely-gated mixture of heterogeneous detection head module.

Figure 2.

Structure of CMFEM. 3x3/2 Conv refers to 3x3 convolution with a stride set to 2. UpSample denotes up-scaling the feature map with a factor of 2. EACA refers to efficient atrous channel-wise attention module.

Figure 2.

Structure of CMFEM. 3x3/2 Conv refers to 3x3 convolution with a stride set to 2. UpSample denotes up-scaling the feature map with a factor of 2. EACA refers to efficient atrous channel-wise attention module.

Figure 3.

The Overall structure of our proposed Efficient Atrous Channel-wise Attention module. The Inter-Enhancement block is composed of atrous convolution with different atrous rate.

Figure 3.

The Overall structure of our proposed Efficient Atrous Channel-wise Attention module. The Inter-Enhancement block is composed of atrous convolution with different atrous rate.

Figure 4.

Inter-enhancement Block.

Figure 4.

Inter-enhancement Block.

Figure 5.

The structure of Atrous Convolution.

Figure 5.

The structure of Atrous Convolution.

Figure 6.

Our Proposed Mixture of Heterogeneous Experts Head (MOHEH) Module. This graph visualizes the structure of each expert. This example shows the number of experts = 4 and the number of selected experts = 2. The activated experts are highlighted in red in this figure.

Figure 6.

Our Proposed Mixture of Heterogeneous Experts Head (MOHEH) Module. This graph visualizes the structure of each expert. This example shows the number of experts = 4 and the number of selected experts = 2. The activated experts are highlighted in red in this figure.

Figure 7.

The Residual Bottleneck

Figure 7.

The Residual Bottleneck

Figure 8.

The Inverted Residual Bottleneck

Figure 8.

The Inverted Residual Bottleneck

Table 1.

Comparison of our proposed method with other state-of-art techniques on the DOTA dataset.

Table 1.

Comparison of our proposed method with other state-of-art techniques on the DOTA dataset.

| Method |

Backbone |

PL |

BD |

BR |

GTF |

SV |

LV |

SH |

TC |

BC |

ST |

SBF |

RA |

HA |

SP |

HC |

mAP |

| RoI Trans [17] |

R-101 |

88.64 |

78.52 |

43.44 |

75.92 |

68.81 |

73.68 |

83.59 |

90.74 |

77.27 |

81.46 |

58.39 |

53.54 |

62.83 |

58.93 |

47.67 |

69.56 |

| CAD-Net [32] |

R-101 |

87.80 |

82.40 |

49.40 |

73.50 |

71.10 |

63.50 |

76.70 |

90.90 |

79.20 |

73.30 |

48.40 |

60.90 |

62.00 |

67.00 |

62.20 |

69.90 |

| DRN [33]

|

H-104 |

88.91 |

80.22 |

43.52 |

63.35 |

73.48 |

70.69 |

84.94 |

90.14 |

83.85 |

84.11 |

50.12 |

58.41 |

67.62 |

68.60 |

52.50 |

70.70 |

|

O2DNet [34]

|

H-104 |

89.31 |

82.14 |

47.33 |

61.21 |

71.32 |

74.03 |

78.62 |

90.76 |

82.23 |

81.36 |

60.93 |

60.17 |

58.21 |

66.98 |

61.03 |

71.04 |

|

SCRDet [35]

|

R-101 |

89.98 |

80.65 |

52.09 |

68.36 |

68.36 |

60.32 |

72.41 |

90.85 |

87.94 |

86.86 |

65.02 |

66.68 |

66.25 |

68.24 |

65.21 |

72.61 |

| R3Det [36] |

R-152 |

89.49 |

81.17 |

50.53 |

66.10 |

70.92 |

78.66 |

78.21 |

90.81 |

85.26 |

84.23 |

61.81 |

63.77 |

68.16 |

69.83 |

67.17 |

73.74 |

| S2A-Net [37] |

R-50 |

89.11 |

82.84 |

48.37 |

71.11 |

78.11 |

78.39 |

87.25 |

90.83 |

84.90 |

85.64 |

60.36 |

62.60 |

65.26 |

69.13 |

57.94 |

74.12 |

| R4Det [38] |

R-152 |

88.96 |

85.42 |

52.91 |

73.84 |

74.86 |

81.52 |

80.29 |

90.79 |

86.95 |

85.25 |

64.05 |

60.93 |

69.00 |

70.55 |

67.76 |

75.84 |

|

O-RCNN [39]

|

R-50 |

89.54 |

82.35 |

54.95 |

70.27 |

78.96 |

82.81 |

88.15 |

90.90 |

86.53 |

84.88 |

62.24 |

65.95 |

75.16 |

69.25 |

55.38 |

75.82 |

| Ours |

R-50 |

89.62 |

83.74 |

53.84 |

73.47 |

78.85 |

83.42 |

88.19 |

90.91 |

87.55 |

85.75 |

63.59 |

67.23 |

75.65 |

70.48 |

58.59 |

76.72 |

Table 2.

Comparison of our proposed method with other state-of-art techniques on the HRSC2016 dataset. R-101 denotes 101 layers used in backbone model. R-50 denotes 50 layers used in backbone model

Table 2.

Comparison of our proposed method with other state-of-art techniques on the HRSC2016 dataset. R-101 denotes 101 layers used in backbone model. R-50 denotes 50 layers used in backbone model

| Method |

Backbone |

mAP07 |

mAP12 |

| R2CNN [40] |

R-101 |

73.07 |

- |

| ROI Trans. [17] |

R-101 |

86.20 |

- |

| Rotated RPN [16] |

R-101 |

79.08 |

85.64 |

| S2A-Net [37] |

R-101 |

90.17 |

95.01 |

| R3Det [36] |

R-101 |

89.26 |

96.01 |

| Oriented RCNN [39] |

R-50 |

90.36 |

96.40 |

| Ours |

R-50 |

90.70 |

97.70 |

Table 3.

Ablation Study of Each Proposed Module. "Fusion Only" means multi-scale fusion and resize back to the original scale

Table 3.

Ablation Study of Each Proposed Module. "Fusion Only" means multi-scale fusion and resize back to the original scale

| Neck |

HRSC2016 |

DOTA |

| FPN |

PAFPN |

Fusion Only |

Residual Pathway |

EACA |

mAP07 |

mAP12 |

mAP |

| ✓ |

|

|

|

|

90.36 |

96.40 |

75.82 |

| |

✓ |

|

|

|

90.39 |

96.52 |

75.90 |

| |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

90.42 |

96.63 |

75.97 |

| |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

90.44 |

96.70 |

76.07 |

| |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

90.58 |

97.20 |

76.40 |

Table 4.

Ablation study results on atrous convolutions of HRSC2016 and DOTA dataset

Table 4.

Ablation study results on atrous convolutions of HRSC2016 and DOTA dataset

| Method |

atrous Rate |

Backbone |

HRSC2016 |

DOTA |

| |

|

|

mAP07 |

mAP12 |

mAP |

| Oriented-RCNN [39] |

- |

R-50 |

90.36 |

96.40 |

75.82 |

| Ours |

(1) |

R-50 |

90.46 |

96.75 |

76.10 |

| Ours |

(1, 2) |

R-50 |

90.50 |

96.90 |

76.22 |

| Ours |

(1, 2, 3) |

R-50 |

90.58 |

97.20 |

76.40 |

| Ours |

(1, 2, 3, 4) |

R-50 |

90.38 |

96.45 |

75.80 |

Table 5.

Ablation Study of Non-MOE heads and MOE heads on DOTA. Mixed head means a single-branch detection head that includes both convolutional layers and FCs layers

Table 5.

Ablation Study of Non-MOE heads and MOE heads on DOTA. Mixed head means a single-branch detection head that includes both convolutional layers and FCs layers

| Head Structure |

Params |

FPS |

mAP |

| Single-branch FCs-only head |

41.13 M |

20.6 |

75.82 |

| Single-branch mixed head (Proposed) |

41.27 M |

20.2 |

75.85 |

| Double-branch residual head |

43.52 M |

17.1 |

76.09 |

| Double-branch inverted-residual head (Proposed) |

42.76 M |

17.9 |

76.04 |

Table 6.

Ablation Study on different top-k and number of experts n. The best mAP result is colored in red

Table 6.

Ablation Study on different top-k and number of experts n. The best mAP result is colored in red

| n |

k |

Params (M) |

FPS |

mAP |

| 4 |

1 |

89.62 |

19.8 |

76.18 |

| 4 |

2 |

89.62 |

18.4 |

76.61 |

| 4 |

3 |

89.62 |

15.7 |

76.50 |

| 4 |

4 |

89.62 |

12.3 |

76.22 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).