Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem Statement

3. Solution of the Linear Problem

3.1. Auxiliary Sturm – Liouville Problem

3.2. Solution of the Linear Boundary-Value Problem

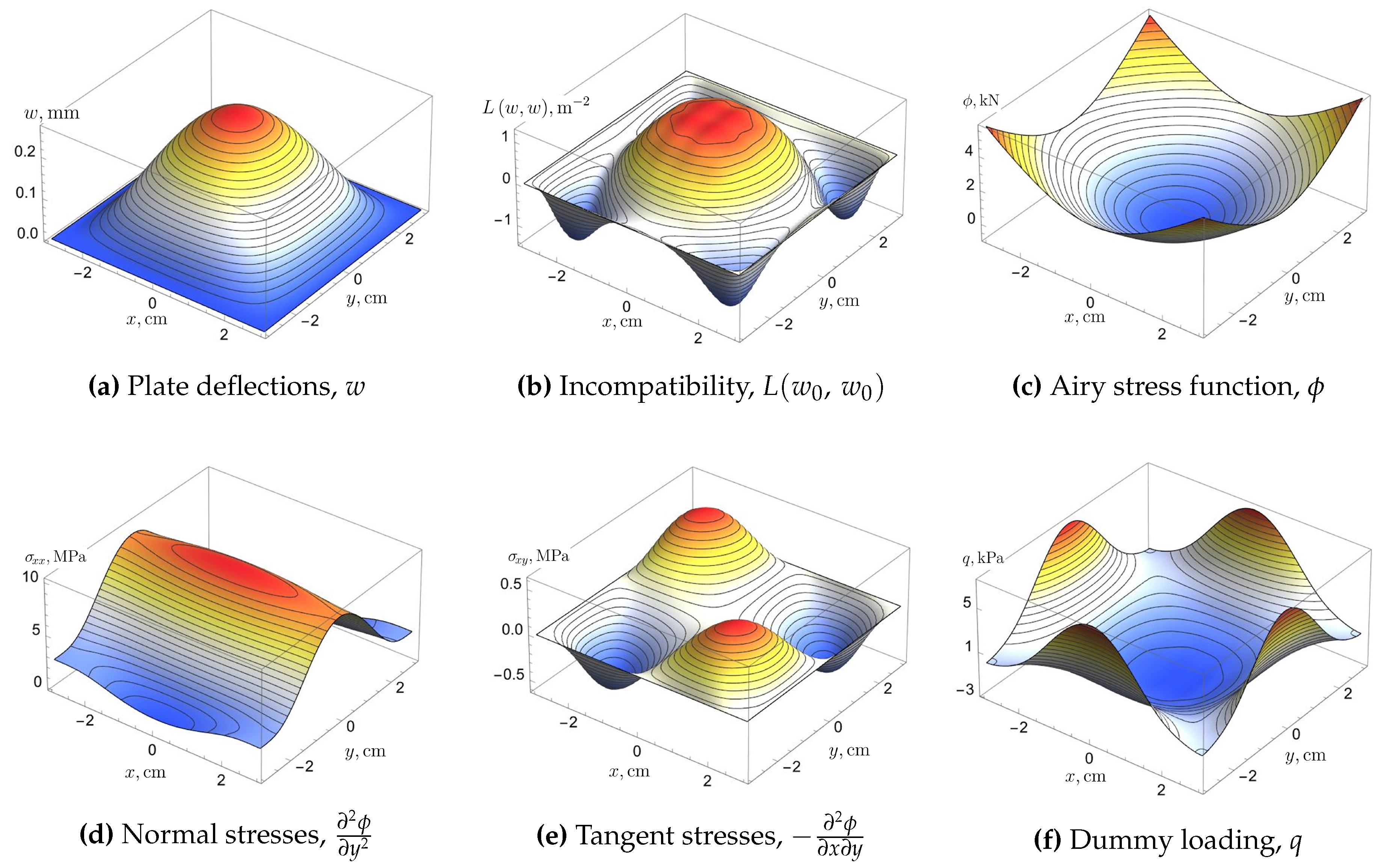

4. Solution of the Föppl-von Kármán System

4.1. Auxiliary Boundary Problem

4.2. Plate with Movable Edges

4.3. Plate with Immovable Edges

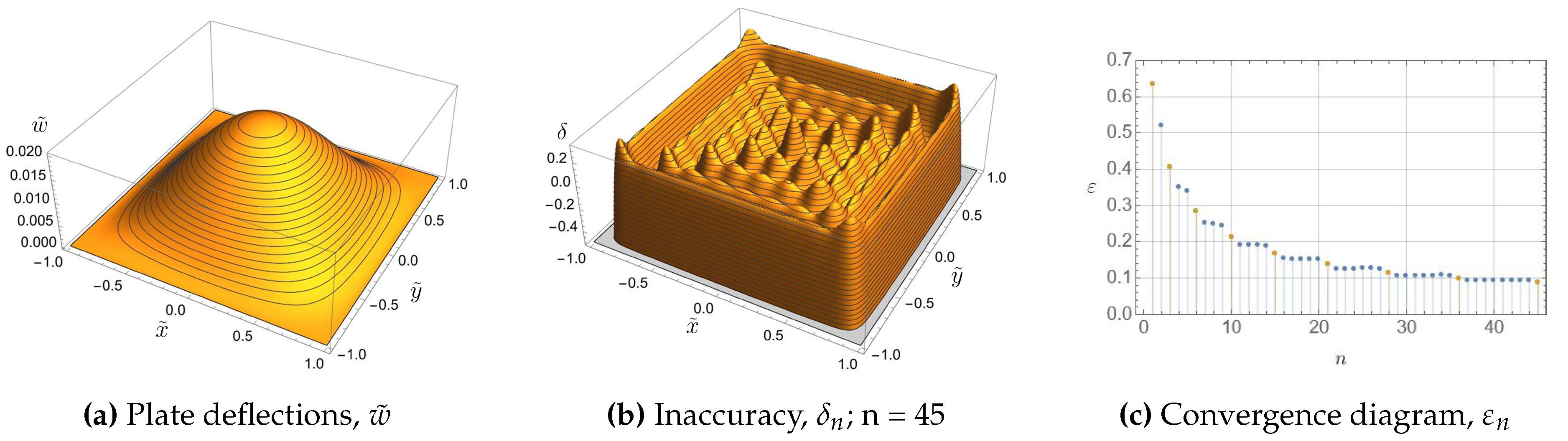

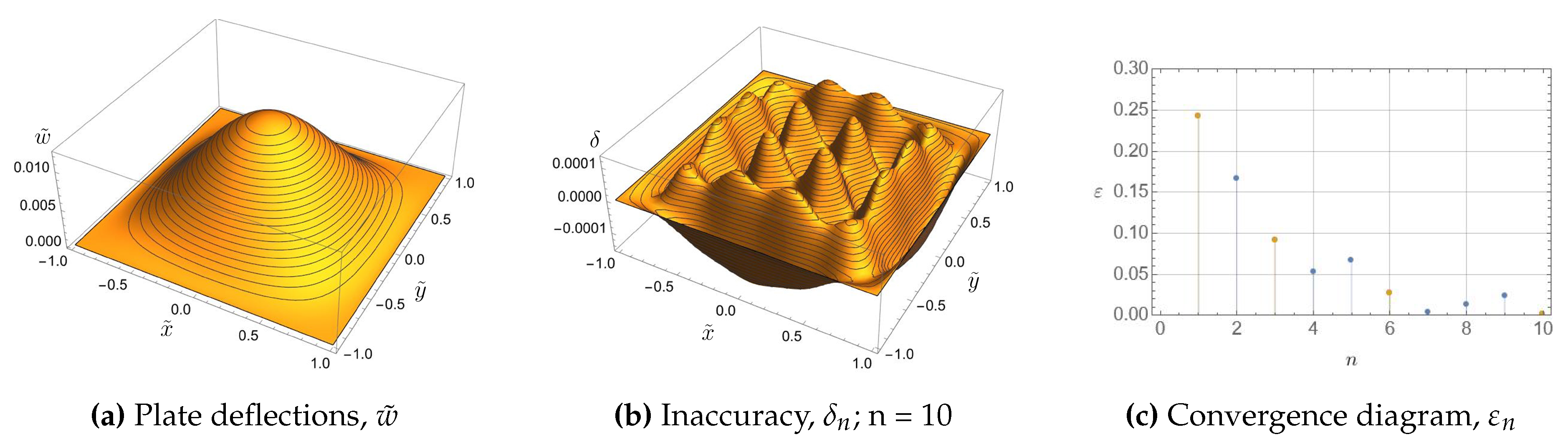

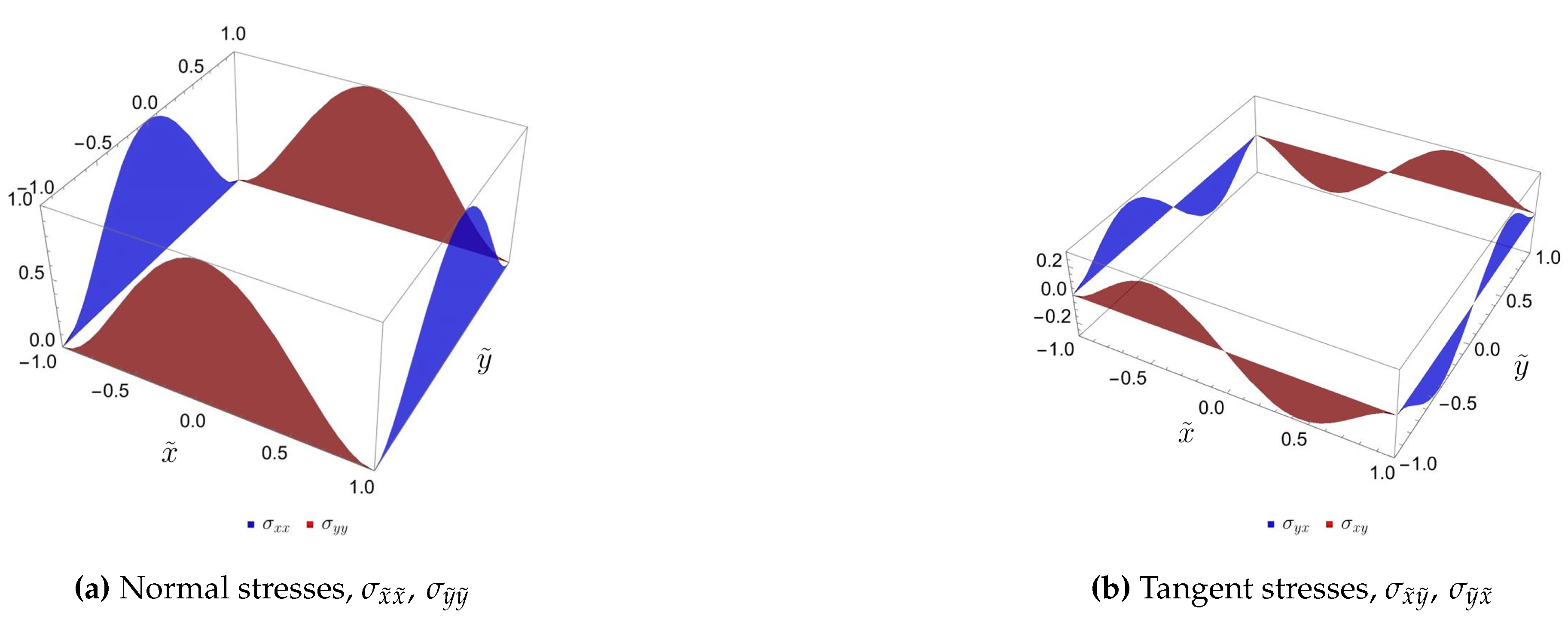

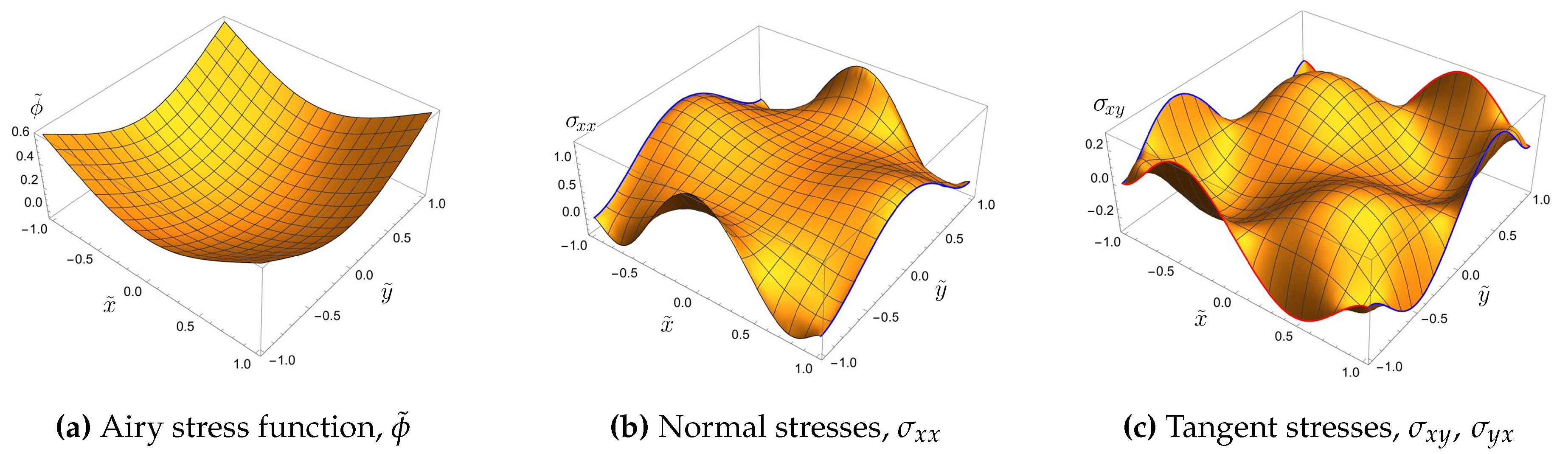

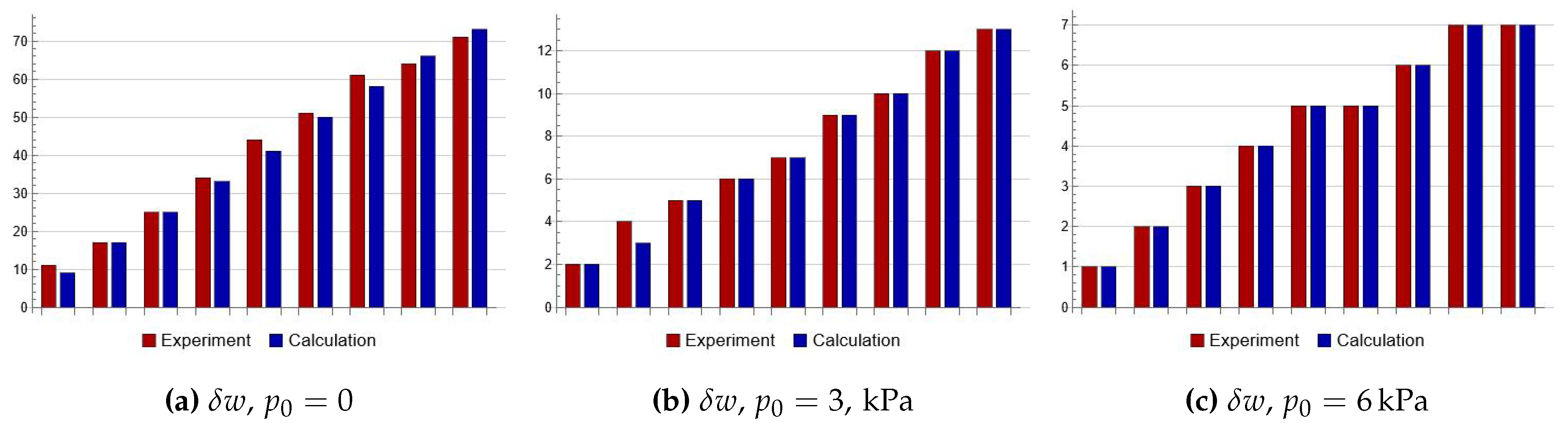

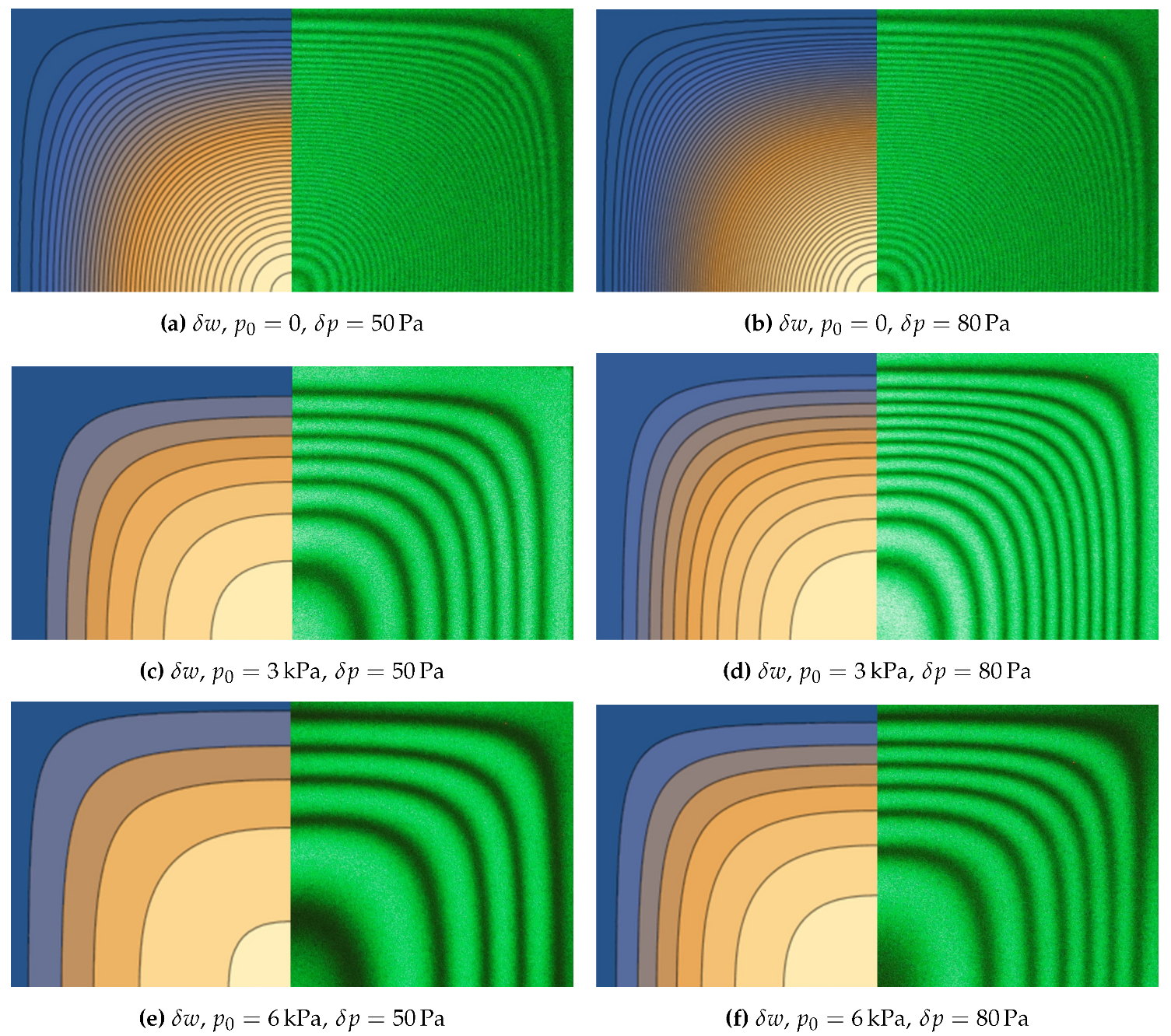

5. Numerical Results and Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FEM | finite element method |

| LHS | left hand side |

| RHS | right hand side |

Appendix A

References

- Föppl, A. Vorlesungen über technische Mechanik. Volume 5; B. G. Teubner Verlag, Leipzig, 1907.

- Ciarlet, P.G. A justification of the von Kármán equations. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis 1980, 73, 349–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kármán, T. Festigkeitsprobleme im Maschinenbau; B. G. Teubner Verlag, Leipzig, 1910.

- Vol’mir, A.S. Flexible plates and shells; Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory, Research and Technology Division, Air …, 1967.

- Lychev, S.; Digilov, A.; Demin, G.; Gusev, E.; Kushnarev, I.; Djuzhev, N.; Bespalov, V. Deformations of Single-Crystal Silicon Circular Plate: Theory and Experiment. Symmetry 2024, 16, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lychev, S.; Digilov, A.; Bespalov, V.; Djuzhev, N. Incompatible Deformations in Hyperelastic Plates. Mathematics 2024, 12, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nádai, A. Die elastischen Platten; Springer, 1925.

- Timoshenko, S. Vibration Problems in Engineering; D. Van Nostrand Co., 1928.

- Way, S. Bending of circular plates with large deflection. Transactions of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers 1934, 56, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, K.O.; Stoker, J.J. The non-linear boundary value problem of the buckled plate. American Journal of Mathematics 1941, 63, 839–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichs, K.O.; Stoker, J.J. The non-linear boundary value problem of the buckled plate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1939, 25, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Large deflection of clamped circular plate and accuracy of its approximate analytical solutions. Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 2016, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, R. Rechnerische und experimentelle Ermittlung der Durchbiegungen und Spannungen von quadratischen Platten bei freier Auflagerung an den Rändern, gleichmäßig verteilter Last und großen Ausbiegungen. ZAMM-Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics/Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik 1936, 16, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, S. Uniformly loaded, clamped, rectangular plates with large deflection. Proc. 5th Int. Congr. on Applied Mechanics.

- Panov, D.I. Application of acad. B.G. Galerkin’s method to certain nonlinear problems of the theory of elasticity. Prikl. Matem. i Mech 1939, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S. Bending of rectangular plates with large deflections; NACA Technical notes No. 846, 1942.

- Levy, S. Square plate with clamped edges under normal pressure producing large deflections; NACA Technical notes No. 847, 1942.

- Levy, S. Bending with large deflection of a clamped rectangular plate with length-width ratio of 1.5 under normal pressure; NACA Technical notes No. 853, 1942.

- Woolley, R.M.; Corrick, J.N.; Levy, S. Clamped long rectangular plate under combined axial load and normal pressure; NACA Technical note No. 1047, 1946.

- Levy, S.; Goldenberg, D.; Zibritosky, G. Simply supported long rectangular plate under combined axial load and normal pressure; NACA Technical notes No. 949, 1944.

- Wang, C.T. Nonlinear large-deflection boundary-value problems of rectangular plates; NACA Technical note No. 1425, 1948.

- Wang, C.T. Bending of rectangular plates with large deflections; NACA Technical note No. 1462, 1948.

- Southwell, R.V.; Green, J.R. Relaxation Methods Applied to Engineering Problems, VIII A. Problems Relating to Large Transverse Displacements of Thin Elastic Plates. Phil. Tran. Roy. Soc. 1944, 1, 137–176. [Google Scholar]

- Timoshenko, S.; Woinowsky-krieger, S. Theory of plates and shells; McGraw-Hill, 1959.

- Bauer, F.; Bauer, L.; Becker, W.; Reiss, E.L. Bending of Rectangular Plates With Finite Deflections1; Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, 1964.

- Bauer, F.; Bauer, L.; Becker, W.; Reiss, E.L. Bending of Rectangular Plates With Finite Deflections1. Journal of Applied Mechanics.

- Hooke, R. Approximate analysis of the large deflection elastic behaviour of clamped, uniformly loaded, rectangular plates. Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 1969, 11, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-zhou, P.; Shu, W. A perturbation-variational solution of the large deflection of rectangular plates under uniform load. Applied Mathematics and Mechanics 1986, 7, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-zhou, P.; Wei-zhong, C. The solution of rectangular plates with large deflection by spline functions. Applied Mathematics and Mechanics 1990, 11, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.T.; Cao, L.; Wang, Y.Z.; Sun, J.Y.; Zheng, Z.L. A biparametric perturbation method for the Föppl–von Kármán equations of bimodular thin plates. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 2017, 455, 1688–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isanbaeva, F.S.; Kornishin, M.S. Large deflections of plates with freely moved edges. Issledovaniia po teorii plastin i obolochek 1965, 3, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, K.R. Simply supported plates with corners free to lift. Journal of Strain Analysis 1969, 4, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, A.; Bernstein, E.L. Bending of normally loaded simply supported rectangular plates in the large-deflection range. Journal of Strain Analysis 1969, 4, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, P.H. A Numerical Solution to the General Large Deflection Plate Equations. SAE Transactions.

- Brown, J.C.; Harvey, J.M. Large deflections of rectangular plates subjected to uniform lateral pressure and compressive edge loading. Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science 1969, 11, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T. A mixed finite element method for the solution of the von Kármán equations. Numerische Mathematik 1976, 26, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezzi, F. Finite element approximations of the von Kármán equations. RAIRO. Analyse numérique 1978, 12, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T. Some aspects of a mixed finite element method applied to fourth order partial differential equations. Computing Methods in Applied Sciences: Second International Symposium –19, 1975. Springer, 2008, pp. 237–256. 15 December.

- Bartels, S. Numerical solution of a Föppl–von Kármán model. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 2017, 55, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, N.; Sawaki, Y. An integral equation approach to finite deflection of elastic plates. International journal of non-linear mechanics 1982, 17, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.Q.; Liu, Y. Finite deflection analysis of elastic plate by the boundary element method. Applied mathematical modelling 1985, 9, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Zheng, Z.D. Incremental analysis of finite deflection of elastic plates via boundary-domain-element method. Engineering analysis with boundary elements 1996, 17, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ji, X.; Tanaka, M. A dual reciprocity boundary element approach for the problems of large deflection of thin elastic plates. Computational mechanics 2000, 26, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waidemam, L.; Venturini, W.S. BEM formulation for von Kármán plates. Engineering analysis with boundary elements 2009, 33, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boresi, A.P.; Turner, J.P. Large deflections of rectangular plates. International journal of non-linear mechanics 1983, 18, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shugaa, M.A.; Al-Gahtani, H.J.; Musa, A.E.S. Automated Ritz method for large deflection of plates with mixed boundary conditions. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2020, 45, 8159–8170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shugaa, M.A.; Al-Gahtani, H.J.; Musa, A.E.S. Ritz method for large deflection of orthotropic thin plates with mixed boundary conditions. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computational Mechanics 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shugaa, M.A.; Musa, A.E.S.; Al-Gahtani, H.J. Ritz Method-Based Formulation for Analysis of FGM Thin Plates Undergoing Large Deflection with Mixed Boundary Conditions. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering.

- Enem, J.I. Nonlinear analysis of isotropic rectangular thin plates using Ritz method. Saudi J Eng Technol 2022, 7, 502–512. [Google Scholar]

- Gorder, R.A.V. Analytical method for the construction of solutions to the Föppl–von Kármán equations governing deflections of a thin flat plate. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 2012, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.X.; Liao, S.J. Analytic Solutions of Von Kármán Plate under Arbitrary Uniform Pressure—Equations in Differential Form. Studies in Applied Mathematics 2017, 138, 371–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.X.; Liao, S.J. Analytic approximations of Von Kármán plate under arbitrary uniform pressure—equations in integral form. Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 2018, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Xu, H.; Liao, S. Coiflets solutions for Föppl-von Kármán equations governing large deflection of a thin flat plate by a novel wavelet-homotopy approach. Numerical Algorithms 2018, 79, 993–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhotyaev, V.V.; Sachenkov, A.V. Large deflections of thin elastic plates. Issledovaniia po teorii plastin i obolochek 1973, 10, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyamoorthy, M. Nonlinear Analysis of Structure; CRC Press, 2017.

- Khoa, D.N. Calculation of flexible rectangular plates using the method of successive approximation. PhD thesis, Moscow state university of civil engineering, 2023.

- Berger, H.M. A New Approach to the Analysis of Large Deflections of Plates. PhD thesis, California Institute of Technology, 1954.

- Nowinski, J. Note on an analysis of large deflections of rectangular plates. Applied Scientific Research, Section A 1963, 11, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S. Large deflection of a circular plate on elastic foundation under a concentrated load at the center. J. Appl. Mech. 1975, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S. Large deflection of a semi-circular plate on elastic foundation under a uniform load. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences-Section A. Springer, 1976, Vol. 83, pp. 21–32.

- Karmakar, B.M. Non-linear dynamic behaviour of plates on elastic foundations. Journal of Sound and Vibration 1977, 54, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, P.S.; Lychev, S.A.; Bout, D.K. Experimental technique for determining the evolution of the bending shape of thin substrate by the copper electrocrystallization in areas of complex shapes. Vestnik Samarskogo Universiteta. Estestvenno-Nauchnaya Seriya 2019, 25, 48–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bout, D.K.; Bychkov, P.S.; Lychev, S.A. The theoretical and experimental study of the bending of a thin substrate during electrolytic deposition. PNRPU Mechanics Bulletin 2020, 1, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lychev, S.A.; Digilov, A.V.; Pivovaroff, N.A. Bending of a circular disk: from cylinder to ultrathin membrane. Vestnik Samarskogo Universiteta. Estestvenno-Nauchnaya Seriya 2023, 29, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, B.; Datta, S. A new approach to an analysis of large deflections of thin elastic plates. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 1981, 16, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaki, N. Influence of large amplitudes on flexural vibrations of elastic plates. ZAMM-Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics/Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik 1961, 41, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, K.T.S.R.; Naqvi, M.M. Large deflections of rectangular plates. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 1966, 1, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.H.; Paik, J.K.; Atluri, S.N. The global nonlinear galerkin method for the analysis of elastic large deflections of plates under combined loads: A scalar homotopy method for the direct solution of nonlinear algebraic equations. Computers Materials and Continua 2011, 23, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.H.; Paik, J.K.; Atluri, S.N. The Global Nonlinear Galerkin Method for the Solution of von Karman Nonlinear Plate Equations: An Optimal & Faster Iterative Method for the Direct Solution of Nonlinear Algebraic Equations F (x)= 0, using x= λ [αF+(1-α) BTF]. Computers Materials and Continua 2011, 23, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.H.; Yue, X.; Atluri, S.N. Solutions of the von Kármán plate equations by a Galerkin method, without inverting the tangent stiffness matrix. Journal of Mechanics of Materials and Structures 2014, 9, 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhoue, Y. A wavelet method for bending of circular plate with large deflection. Acta Mechanica Solida Sinica 2015, 28, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.H. Wavelet solution for large deflection bending problems of thin rectangular plates. Archive of Applied Mechanics 2015, 85, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarlet, P.G. Mathematical Elasticity: Theory of Plates; Elsevier, 1997.

- Lychev, S.A. Incompatible Deformations of Elastic Plates. Uchenye Zapiski Kazanskogo Universiteta. Seriya Fiziko-Matematicheskie Nauki 2023, 165, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, N.F. On the non-linear theory of thin plates. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1957, 5, 968–971. [Google Scholar]

- Leray, J.; Schauder, J. Topologie et équations fonctionnelles. Annales scientifiques de l’École normale supérieure 1934, 13, 45–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.S.; Fife, P.C. On von Kármán’s equations and the buckling of a thin elastic plate. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 1966, 72, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knightly, G.H. An existence theorem for the von Kármán equations. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis 1967, 27, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knightly, G.H.; Sather, D. On nonuniqueness of solutions of the von Kármán equations. Archive for Rational Mechanics and Analysis 1970, 36, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlaváček, I.; Naumann, J. Inhomogeneous boundary value problems for the von Kármán equations. I. Applications of Mathematics 1974, 19, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlaváček, I.; Naumann, J. Inhomogeneous boundary value problems for the von Kármán equations. II. Applications of Mathematics 1975, 20, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, A.I. Theory of elasticity; Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- Ciarlet, P.G. Mathematical Elasticity: Three-dimensional elasticity; Elsevier, 1988.

- Muskhelishvili, N.I. Some basic problems of the mathematical theory of elasticity; Noordhoff Groningen, 1953.

- Kalandiya, A.I. Mathematical methods of two-dimensional elasticity; Mir Publishers, 1975.

- Kolmogorov, A.N.; Fomin, S.V. Introductory real analysis; Courier Corporation, 1975.

- Cantor, G. Ein beitrag zur mannigfaltigkeitslehre. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (Crelles Journal) 1878, 1878, 242–258. [Google Scholar]

- Koyalovich, B.M. A study of infinite systems of linear algebraic equations. Izv. Fiz.-Mat. Inst 1930, 3, 41–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kantorovich, L.V.; Krylov, V.I. Approximate methods of higher analysis; Dover Publications, 2018.

- Vest, C.M. Holographic interferometry; Wiley, 1979.

| Eigenvalue number | Numerical solution | Approximation formula | Relative error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.36502 | 2.35619 | 0.00372 |

| 2 | 5.49780 | 5.49779 | |

| 3 | 8.63938 | 8.63938 | |

| 4 | 11.7810 | 11.7810 | |

| 5 | 14.9226 | 14.9226 |

| Eigenvalue number | Numerical solution | Approximation formula | Relative error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.92660 | 3.92699 | 0.00010 |

| 2 | 7.06858 | 7.06858 | |

| 3 | 10.2102 | 10.2102 | |

| 4 | 13.3518 | 13.3518 | |

| 5 | 16.4934 | 16.4934 |

| Structure | Components expression |

|---|---|

| matrix | |

| matrix | |

| matrix | |

| matrix | |

| cubic matrix | |

| cubic matrix | |

| cubic matrix | |

| cubic matrix |

| Structure | Components Expression |

|---|---|

| vectors | |

| vector | |

| vector | |

| vector | |

| matrix | |

| matrix | |

| matrix | |

| matrix | |

| matrix | |

| cubic matrix | |

| cubic matrix |

| Length, cm | Thickness, m | Young Modulus, GPa | Poisson’s ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 184 | 128 | 0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).