Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Treatments

2.2. Dynamic Simulation of Crop Water Use and Yield Responses Through CropWat Modeling

2.3. Evaluation of Water Footprint and Its Key Components

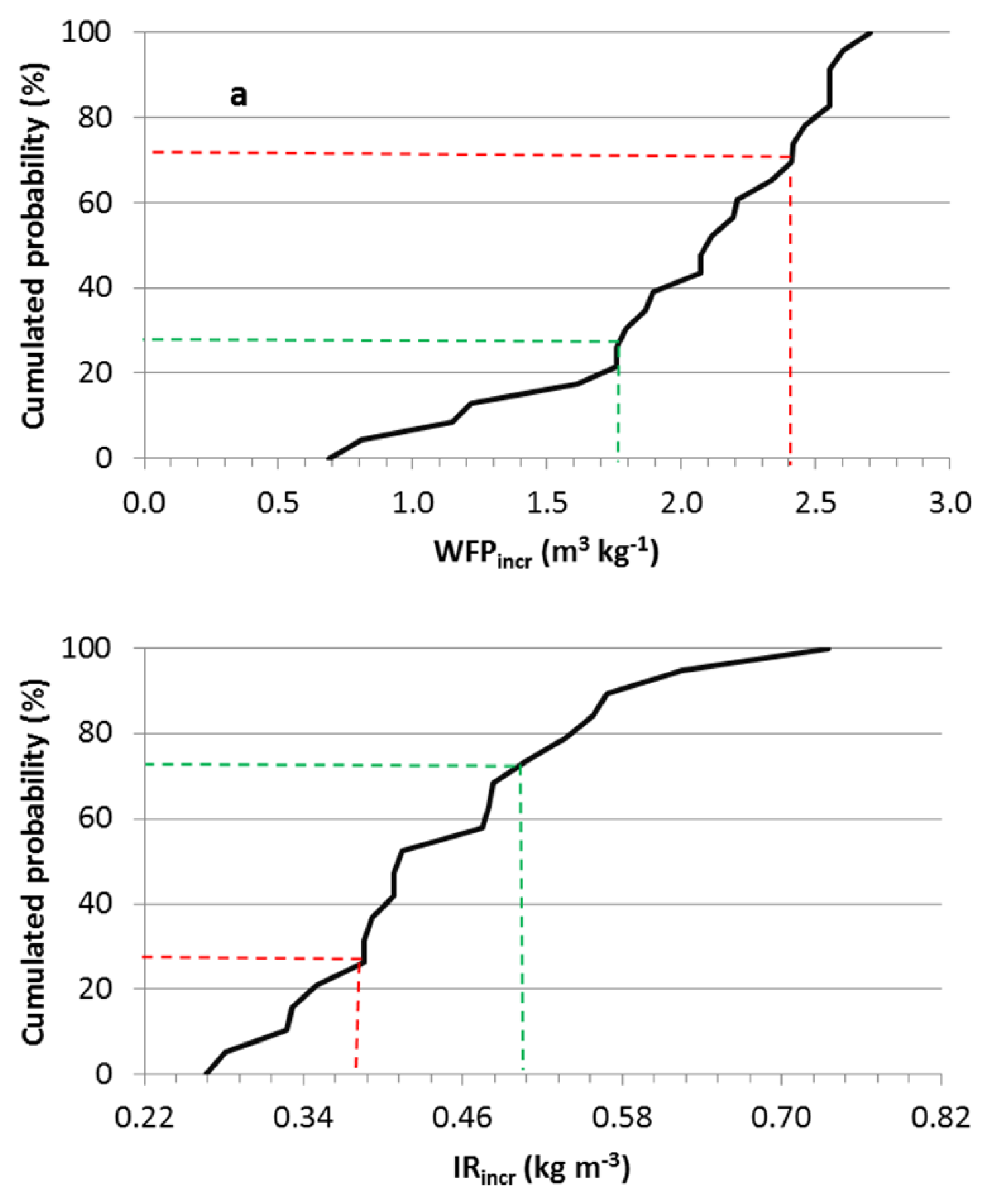

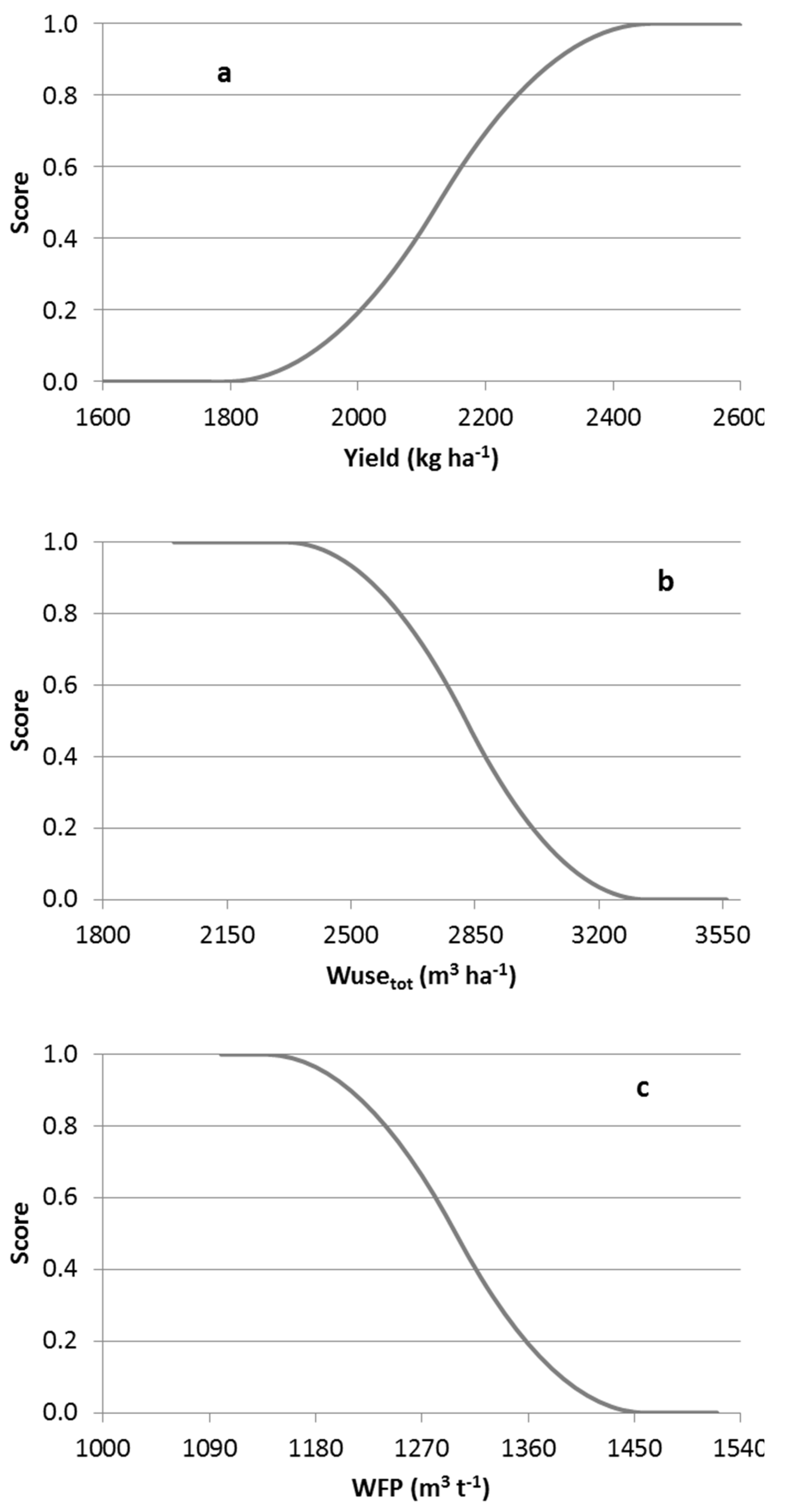

2.4. Screening and Ranking of Olive Cropping Systems Through an Aggregative Framework

3. Results

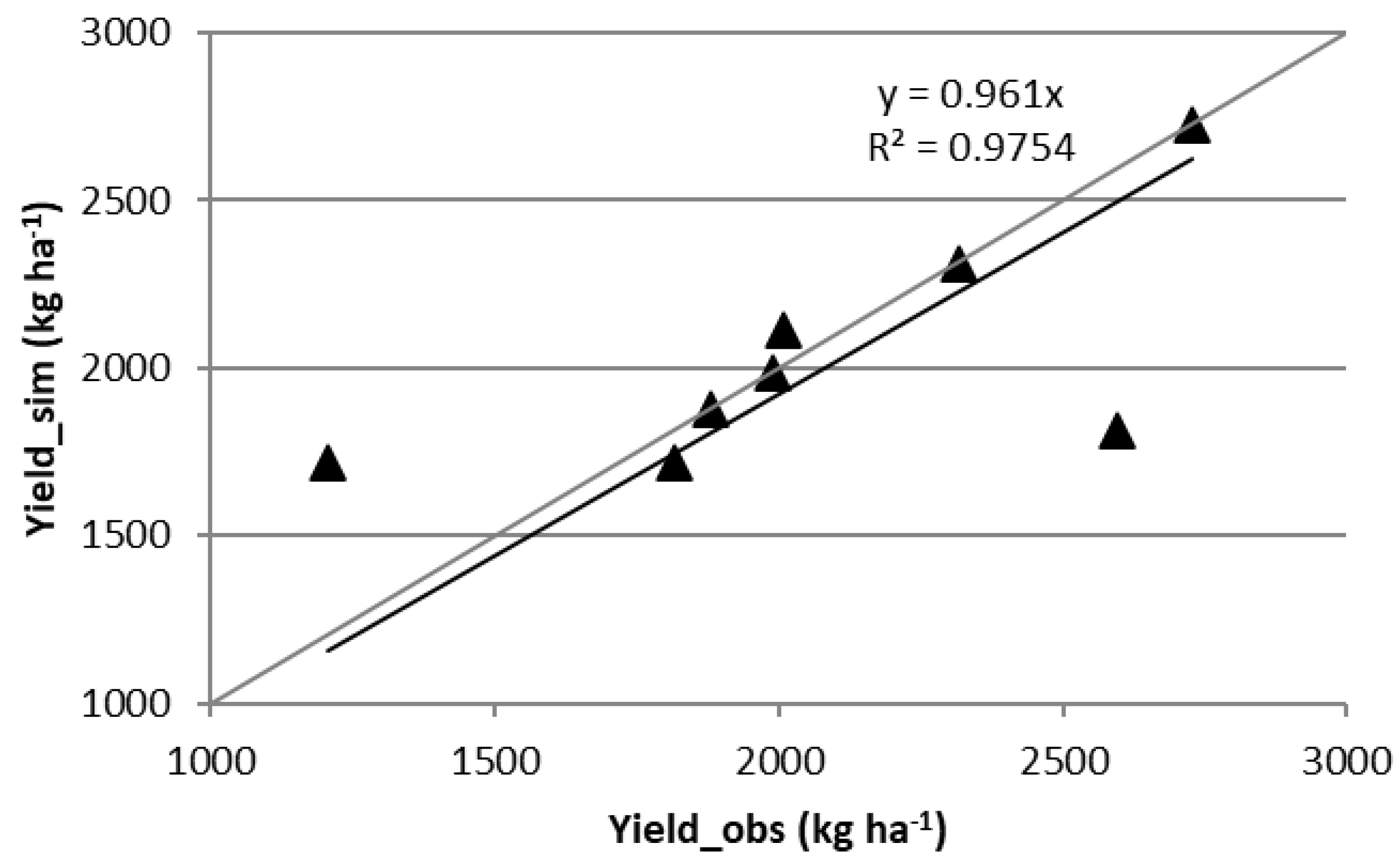

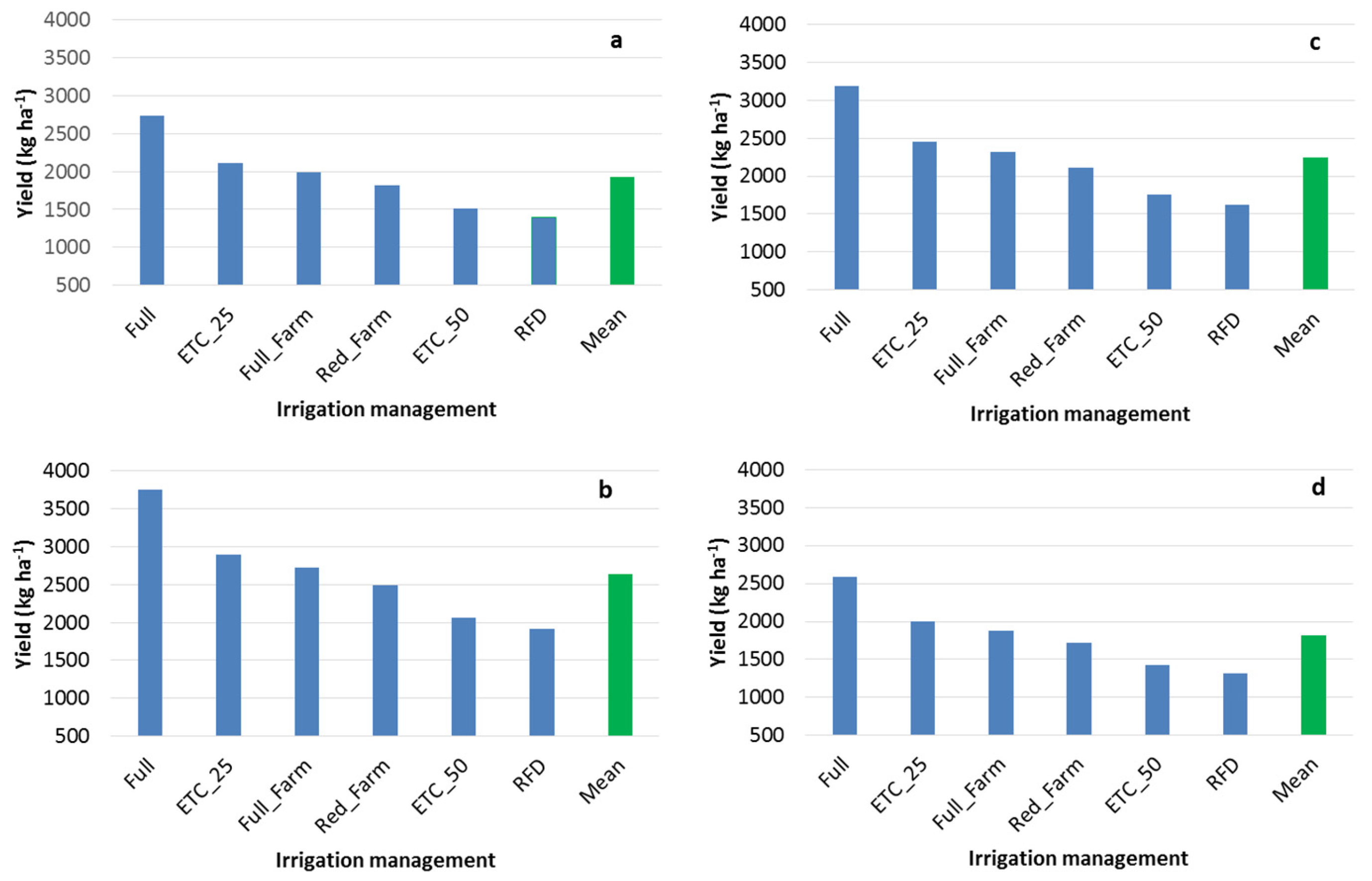

3.1. The Performance of the Olive Cropping System

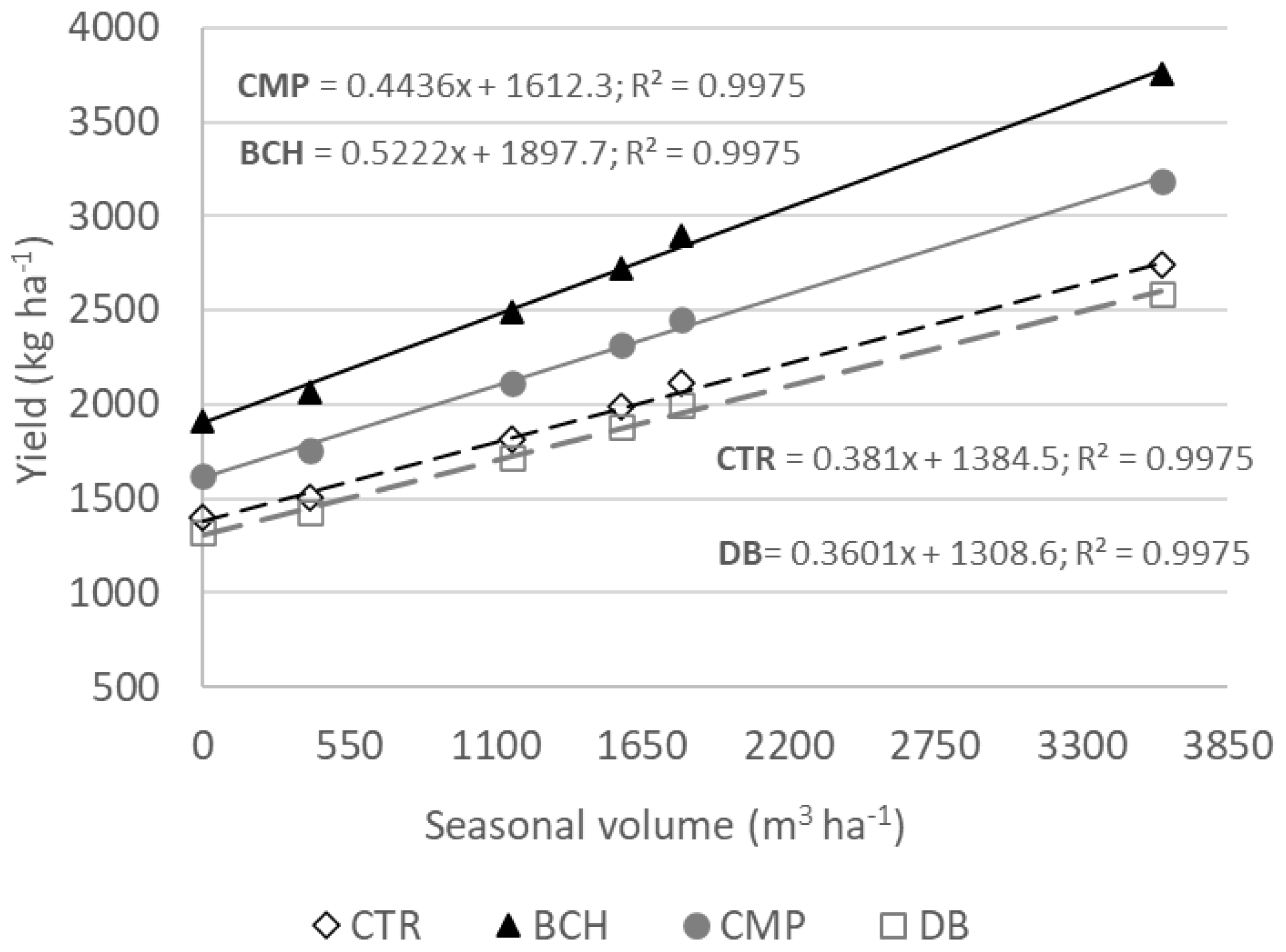

3.2. The Water Dynamics of the Olive Cropping System

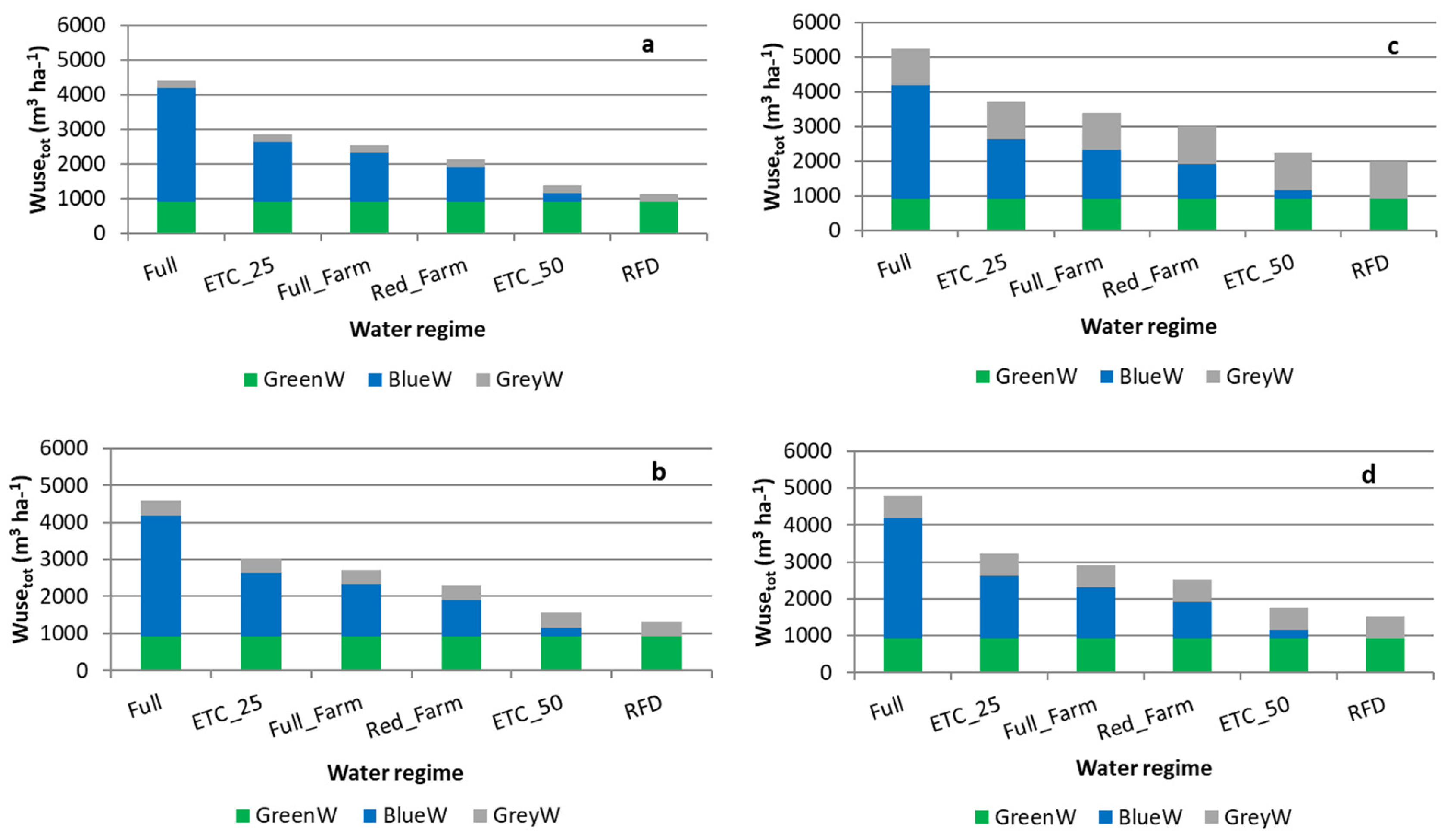

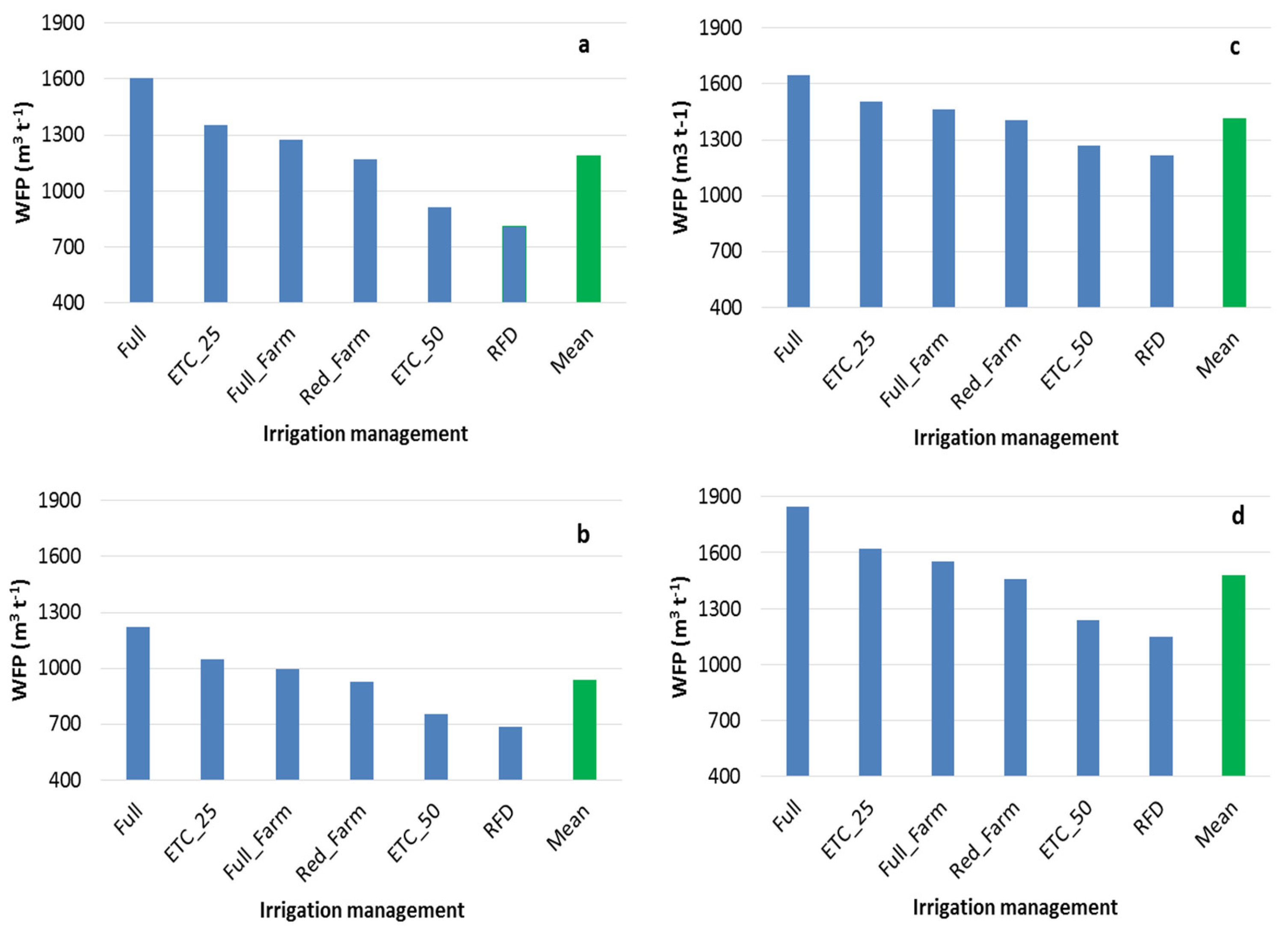

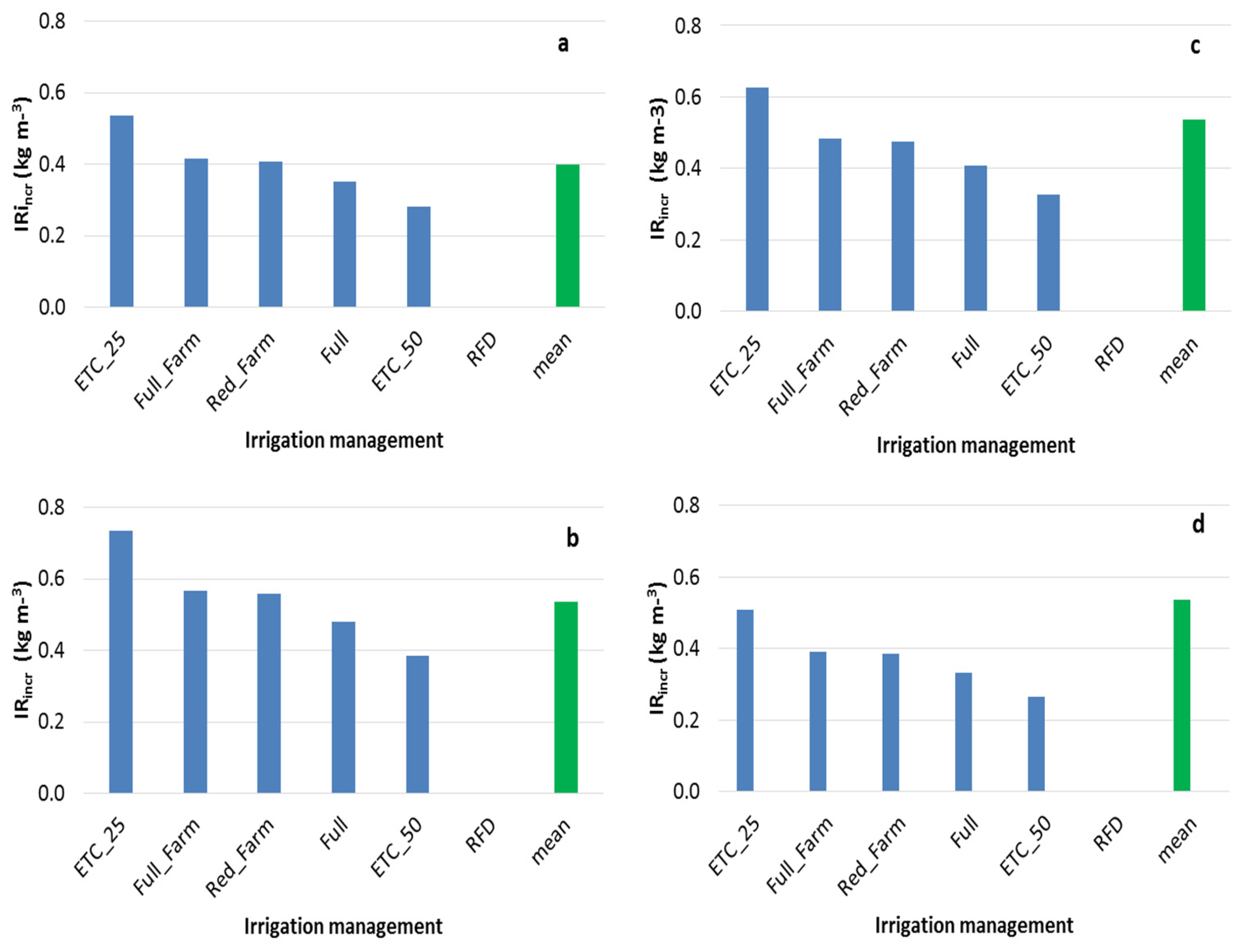

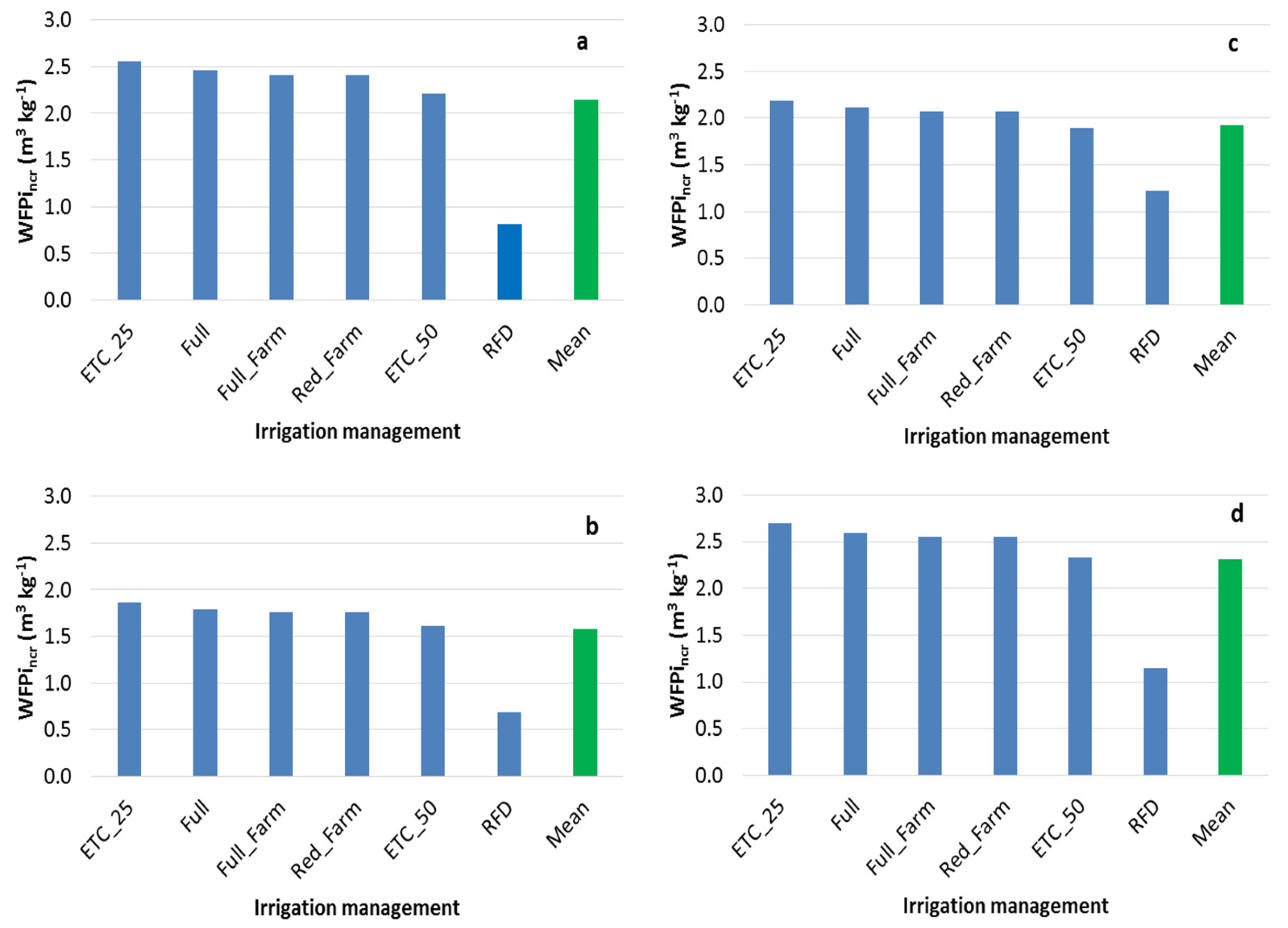

3.3. The Water Use and the Water Footprint

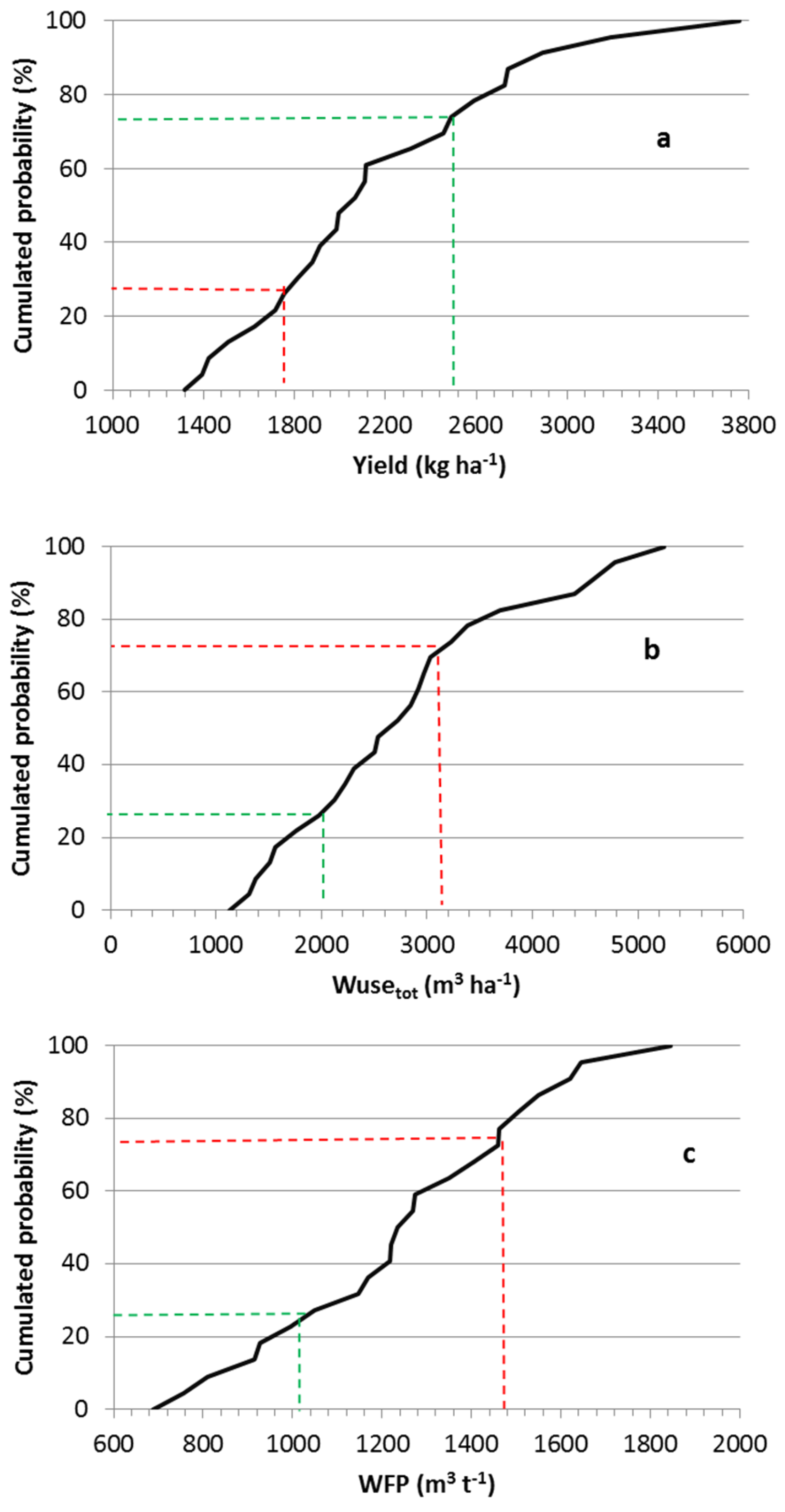

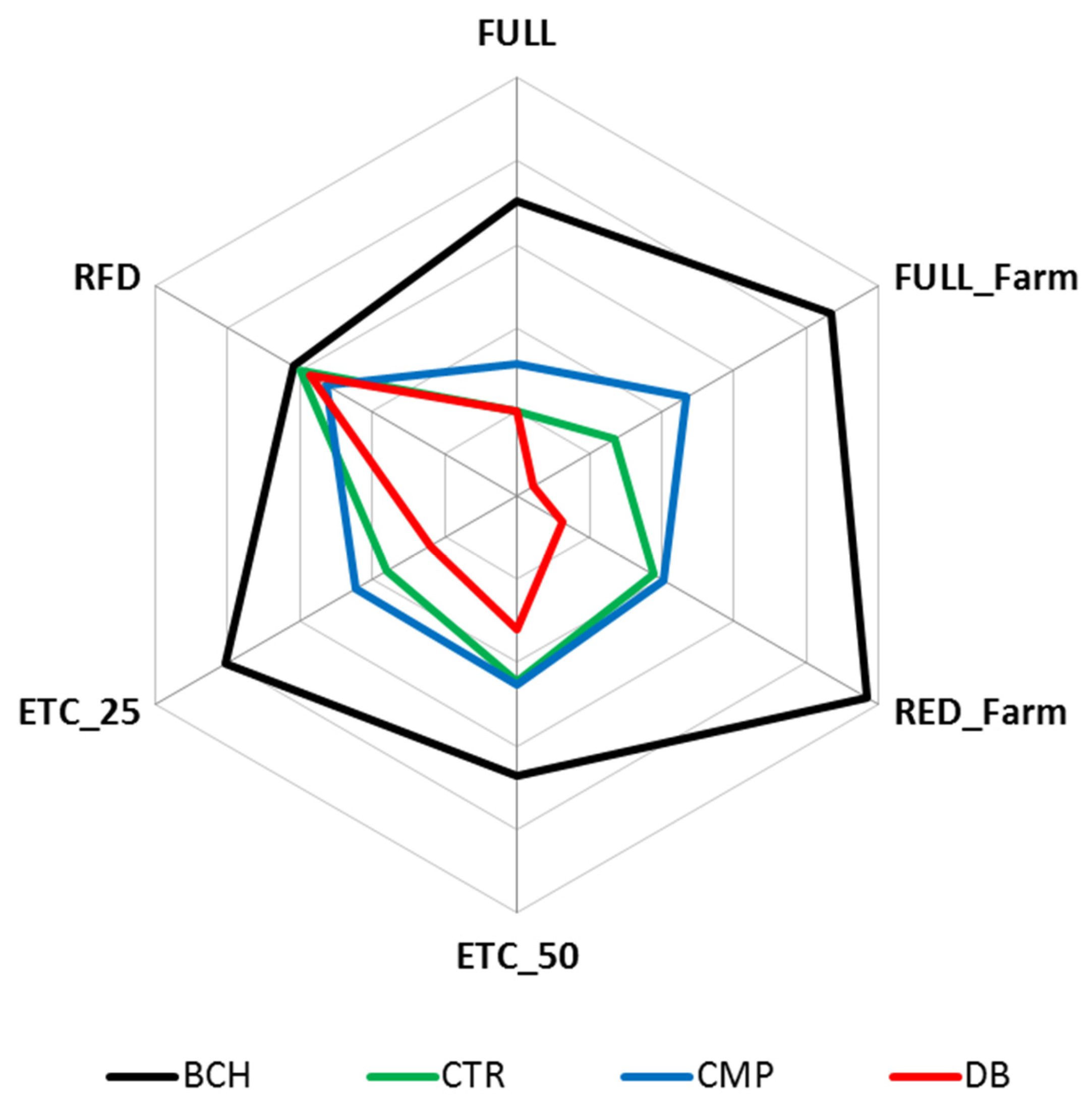

3.4. The Assessment, Screening, and Ranking of Olive Cropping Systems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Molden, D. Water for Food, Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture, 1st ed; Earthscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UN. United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Ingrao, C.; Matarazzo, A.; Tricase, C.; Clasadonte, M.T.; Huisingh, D. Life Cycle Assessment for highlighting environmental hotspots in Sicilian peach production systems. J Clean Prod, 2015, 92, 109e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Cañas, J.; Moreno-Pérez, M. F. Water and irrigation management in arid and semiarid zones. Water, 2021, 13, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovella, T.; Paiano, A.; Lagioia, G. A meso-level water use assessment in the Mediterranean agriculture. Multiple applications of water footprint for some traditional crops. J Clean Prod, 2022, 330, 129886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Water Scarcity and Droughts in the European Union. 31 October. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/water/water-scarcity-and-droughts_en (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Daccache, A.; Ciurana, J.S.; Diaz, J.R.; Knox, J. W. Water and energy footprint of irrigated agriculture in the Mediterranean region. Environ Res Lett, 2014, 9, 124014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, F.N.; Iwra, M.; Tecnico, I.S. Water resources in the Mediterranean region. Int Water Resour Assoc, 2009, 24, 22e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanjra, M.; Qureshi, M.E. Global water crisis and future food security in an era of climate change. Food Policy, 2010, 35, 365e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AQUASTAT, F.A.O. Database aquastat. Available online: http://www.fao.org/aquastat/statistics/query/results.html (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- EUROSTAT. Agri-environmental indicator—irrigation. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agri-environmental_indicator_-_irrigation#Analysis_at_regional_level (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- FAO-Aquastat. AQUASTAT—FAO’s Global Information System on Water and Agriculture. Available online: https://www.fao.org/aquastat/en/countries-and-basins/country-profiles/country/ITA (Accessed October 2024).

- IPCC, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Riscaldamento Globale di 1,5◦C, 29. WMO—UNEP. 31 October. Available online: https://ipccitalia.cmcc.it/ipcc-special-report-global-warming-of-1-5-c/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Chapagain, A.K.; Aldaya, M.M.; Mekonnen, M.M. The Water Footprint Assessment Manual: Setting the Global Standard; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ridoutt, B.G.; Eady, S.J.; Sellahewa, J.; Simons, L.; Bektash, R. Water footprinting at the product brand level: case study and future challenges. J Clean Prod, 2009, 17, 1228e1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Regni, L.; Rinaldi, S.; Sdringola, P.; Calisti, R.; Brunori, A.; et al. Long-term water footprint assessment in a rainfed olive tree grove in the Umbria region, Italy. Agriculture, 2019, 0, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, G.; Ingrao, C.; Camposeo, S.; Tricase, C.; Conto, F.; Huisingh, D. Application of ater footprint to olive growing systems in the Apulia region: a comparative assessment. J Clean Prod, 2016, 112, 2407–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci, 2011, 15, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamastra, L.; Suciu, N.A.; Novelli, E.; Trevisan, M. A new approach to assessing the water footprint of wine: an Italian case study. Sci Total Environ, 2014, 490, 748e756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmoral Portillo, G.; Aldaya, M.M.; Chico Zamanillo, D.; Garrido Colmenero, A.; Llamas Madurga, R. The water footprint of olives and olive oil in Spain. Span J Agric Res, 2011, 9, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichio, B.; Palese, A.M.; Montanaro, G.; Xylogiannis, E.; Sofo, A. A preliminary assessment of water footprint components in a Mediterranean olive grove. Acta Hortic, 2014, 1038, 671e676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. 31 October. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?lang=en&SubSessionId=1c572416-dfdd-4407-a71b-2b4d276d78da (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Ibba, K.; Kassout, J.; Boselli, V.; Er-Raki, S.; Oulbi, S.; Mansouri, L.E.; et al. Assessing the impact of deficit irrigation strategies on agronomic and productive parameters of Menara olive cultivar: implications for operational water management. Front Environ Sci, 2023, 11, 1100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, R.M.; Bruno, M.R.; Campi, P.; Camposeo, S.; De Carolis, G.; Gaeta, L.; Martinelli, N.; Mastrorilli, M.; Modugno, A.F.; Mongelli, T.; et al. Water Use of a Super High-Density Olive Orchard Submitted to Regulated Deficit Irrigation in Mediterranean Environment over Three Contrasted Years. Irrig Sci 2024, 42, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, B.M.; Manzoni, S.; Morillas, L.; Garcia, M.; Johnson, M.S.; Lyon, S. W. Improving agricultural water use efficiency with biochar–A synthesis of biochar effects on water storage and fluxes across scales. Sci Total Environ, 2019, 657, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, G.; Bass, A.M.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Benefits of biochar, compost and biochar–compost for soil quality, maize yield and greenhouse gas emissions in a tropical agricultural soil. Sci Total Environ, 2016, 543, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leogrande, R.; Vitti, C.; Castellini, M.; Garofalo, P.; Samarelli, I.; Lacolla, G.; Montesano, F.F.; Spagnuolo, M.; Mastrangelo, M.; Stellacci, A.M. Residual Effect of Compost and Biochar Amendment on Soil Chemical, Biological, and Physical Properties and Durum Wheat Response. Agronomy, 2024, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Sánchez-García, M.; Vandecasteele, B.; D’Hose, T.; López, G.; et al. Agronomic evaluation of biochar, compost and biochar-blended compost across different cropping systems: Perspective from the European project FERTIPLUS. Agronomy, 2019, 9, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration—Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements—FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56; FAO: Rome, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, G.H.; Samani, Z.A. Reference Crop Evapotranspiration from Temperature. Appl Eng Agric, 1985, 1, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. CROPWAT: A computer program for irrigation planning and management (No. 46). Food and Agriculture Org. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R. G.; Pereira, L.S. Estimating crop coefficients from fraction of ground cover and height. Irrig Sci, 2009, 28, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATTM—Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare. Decreto Legislativo 3 Aprile 2006 n. 152 “Norma in materia ambientale” (ME—Ministry of the Environment, 2006. Law Decree April 3, 2006 n. 152 “Environmental Standard”) (in Italian).

- Ozturk, M.; Altay, V.; Gönenç, T.M.; Unal, B.T.; Efe, R.; Akçiçek, E.; Bukhari, A. An Overview of Olive Cultivation in Turkey: Botanical Features, Eco-Physiology and Phytochemical Aspects. Agronomy 2021, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, M.; Benítez, C. Effects of different organic wastes on soil biochemical properties and yield in an olive grove. Appl Soil Ecol, 2020, 146, 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, P. : De Rosa, L.; Salluzzo, A.; De Gisi, S. Combining GIS and FAO’s crop water productivity model for the estimation of water footprinting in a temporary river catchment. Sustain Prod Consum, 2019, 17, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, P.; Campi, P.; Vonella, A.V.; Mastrorilli, M. Application of multi-metric analysis for the evaluation of energy performance and energy use efficiency of sweet sorghum in the bioethanol supply-chain: A fuzzy-based expert system approach. Appl Energy, 2018, 220, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, P.; Mastrorilli, M.; Ventrella, D.; Vonella, A.V.; Campi, P. Modelling the suitability of energy crops through a fuzzy-based system approach: The case of sugar beet in the bioethanol supply chain. Energy, 2020, 196, 117160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H. Integrated multi-objective stochastic fuzzy programming and AHP method for agricultural water and land optimization allocation under multiple uncertainties. J Clean Prod, 2019, 210, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Bi, L.; Wang, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; et al. Multi-objective optimization of water and fertilizer management for potato production in sandy areas of northern China based on TOPSIS. Field Crop Res, 2019, 240, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi-Eshkaftaki, M.; Rafiee, M.R. Optimization of irrigation management: A multi-objective approach based on crop yield, growth, evapotranspiration, water use efficiency and soil salinity. J Clean Prod 2020, 252, 119901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compost | Biochar | |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture (g 100g-1) | 50 | 77 |

| pH | 8.00 | 9.60 |

| Electrical conductivity (dS m-1) | 2.20 | 0.46 |

| Total Organic Carbon (g kg-1 d.m.) | 200 | 882 |

| Nitrogen (g kg-1 d.m.) | 8.00 | 3.00 |

| Stage | *Kc | Days | Rootind depth | *Critical depletion (p) | *Yield response factor (f) | Crop height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | m | |||||

| Initial | 0.65 | 30 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Development | - | 80 | - | - | 1.00 | - |

| Mid-season | 0.70 | 55 | 1.50 | 0.65 | 1.00 | - |

| Late season | 0.60 | 80 | - | 0.65 | 1.00 | - |

| Source | gdl | Sum of Square | Mean Square | F statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 1 | 3.31*10^7 | 3.31*10^7 | 277.07 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 7 | 8.34*10^5 | 11.94*10^4 | ||

| Total | 8 | 3.39*10^7 |

| Management | *ETp | Seasonal volume | Irrigation | *ETc_act | ETC_act/ETp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mm | n° | mm | ||

| Full | 601 | 360 | 18 | 601 | 1 |

| ETC_25 | 601 | 180 | 9 | 463 | 0.77 |

| Full_Farm | 601 | 157 | 8 | 436 | 0.73 |

| RED_Farm | 601 | 116 | 7 | 398 | 0.66 |

| ETC_50 | 601 | 40 | 2 | 331 | 0.55 |

| RFD | 601 | 0 | 0 | 309 | 0.51 |

| Fertilizer | Irrigation | Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | Wusetot | WFP | WFPincr | IRincr | ||

| CTR | Full | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Full_Farm | 0.20 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.15 | |

| RED_Farm | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.00 | 0.10 | |

| ETC_50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.22 | 0.00 | |

| ETC_25 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| RFD | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| BCH | Full | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.88 |

| Full_Farm | 1.00 | 0.34 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| RED_Farm | 1.00 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| ETC_50 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.01 | |

| ETC_25 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 | |

| RFD | 0.09 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| CMP | Full | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.47 | 0.10 |

| Full_Farm | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 0.90 | |

| RED_Farm | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.83 | |

| ETC_50 | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.43 | 0.94 | 0.00 | |

| ETC_25 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 1.00 | |

| RFD | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.65 | 1.00 | ||

| DB | Full | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Full_Farm | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| RED_Farm | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| ETC_50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.00 | |

| ETC_25 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.99 | |

| RFD | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 1.00 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).