Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The modulation of the magneto-optic signal is a crucial research focus in the field of magneto-optics. Micron array of varying shapes were fabricated using the UV exposure technique, and test their effects on the magneto-optical Kerr response of CoFeB thin films. The influence of the organic-inorganic interface on the magneto-optical Kerr effect was investigated by utilizing organic materials to fabricate arrays. The results indicate that the micron-scale metal array exhibits a limited enhancement of the magneto-optical Kerr signal, but it can change the ferromagnetic strength and the magnetization speed of the magnetic layer. Because the electron orbit coupling at the organic inorganic interface enhances the performance of the magnetic film. When the photoresist is used as the array material, the longitudinal magneto-optical Kerr signal of the CoFeB film increases by at least 2 times. The enhancement effect of different shapes of arrays is different because of the different contact area with CoFeB.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

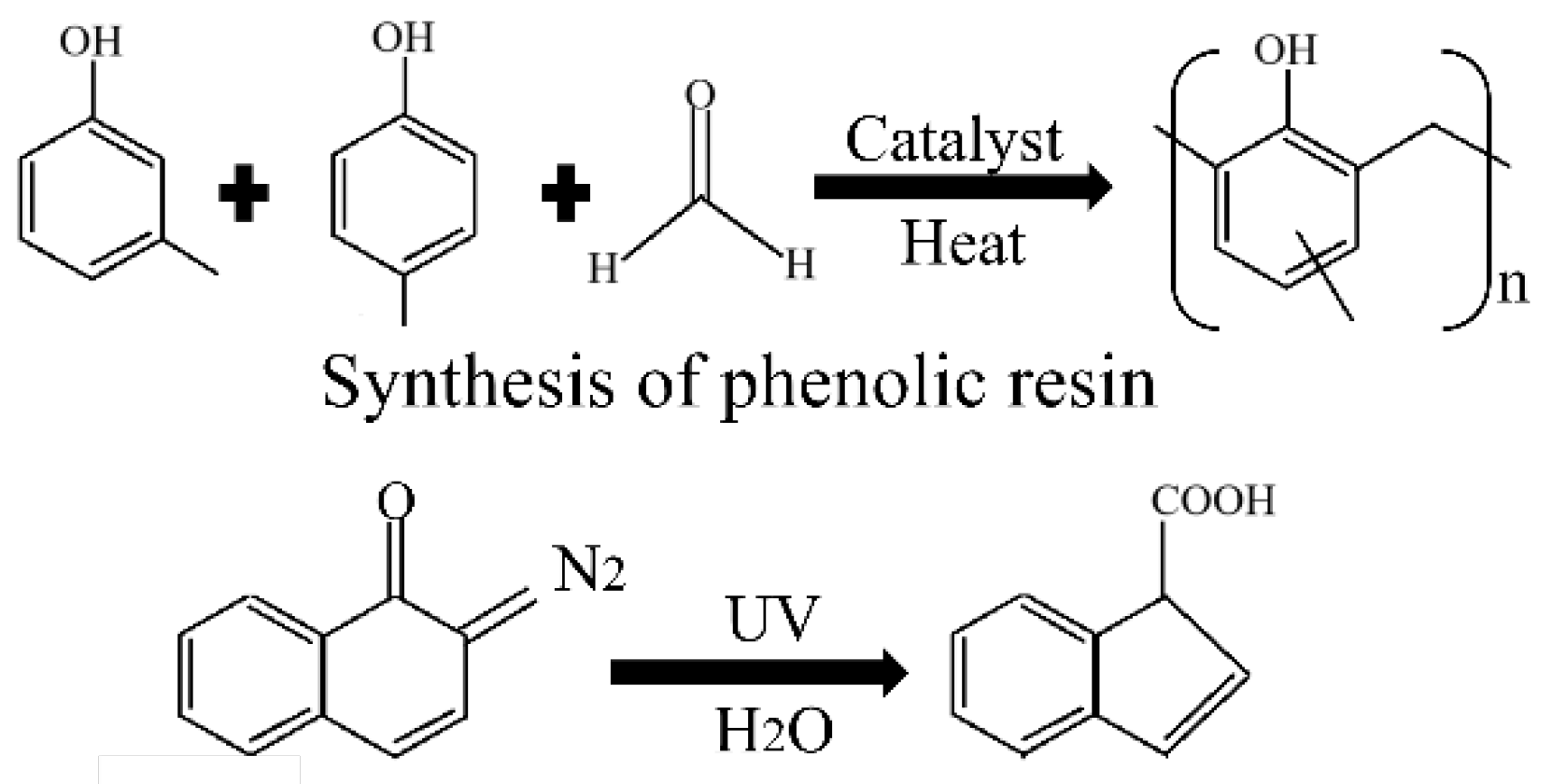

2.1. Preparation of Micrometer Arrays

2.2. Magneto-Optical Kerr Test System

3. Results and Discussion

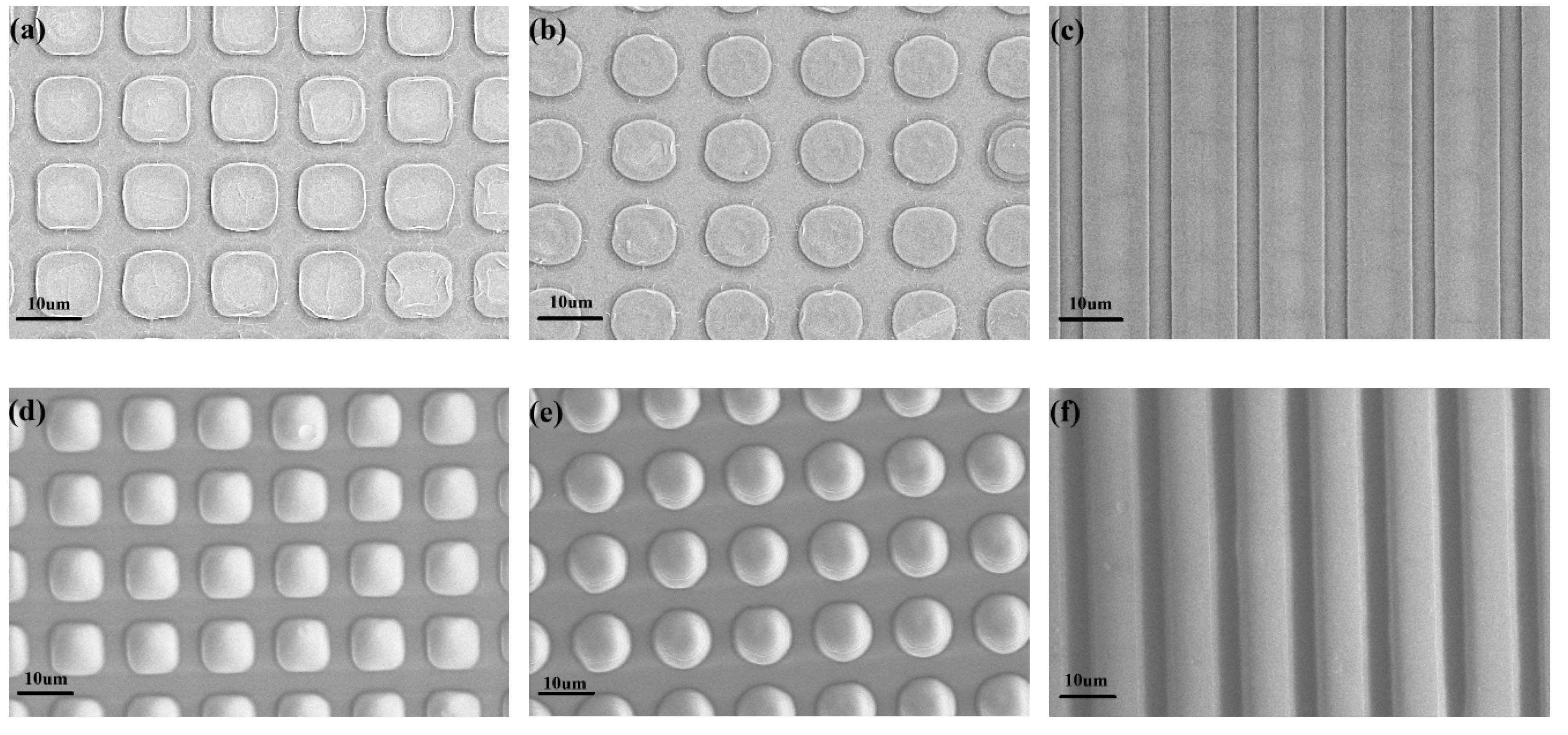

3.1. Characterization of Micron Structure

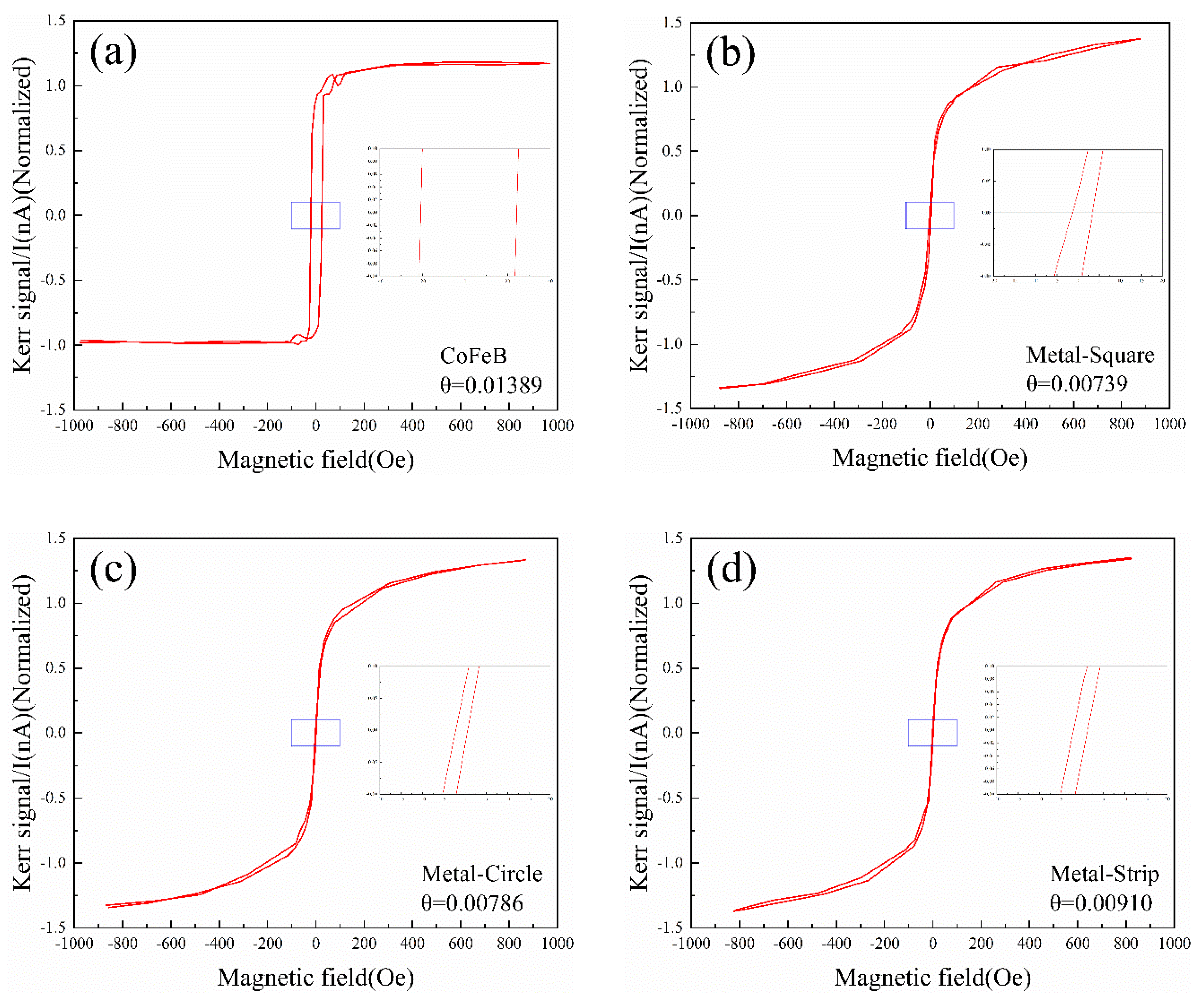

3.2. Longitudinal Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect Test for the Metal Array

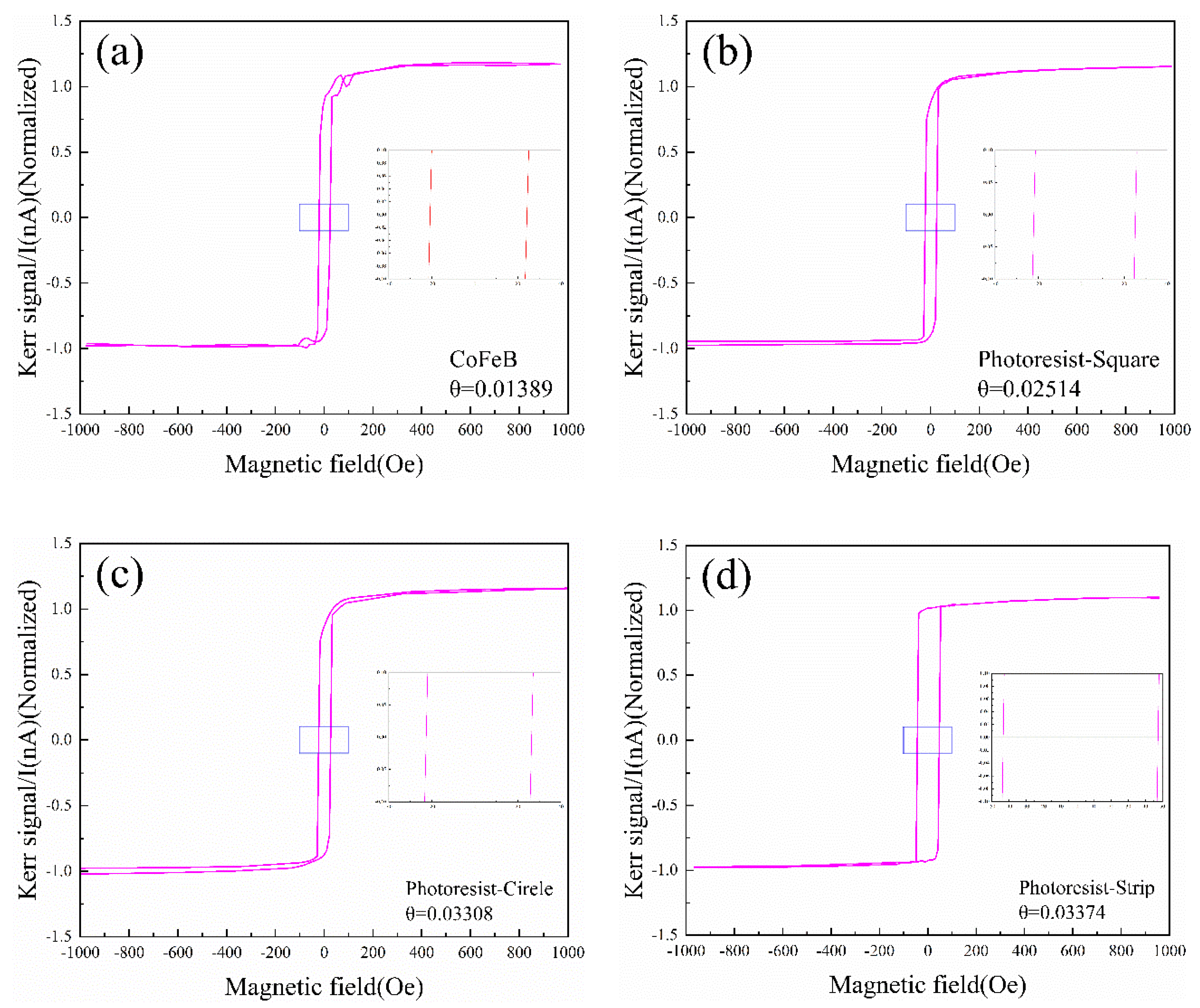

3.3. Longitudinal Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect Test for the photoresist Array

4. Conclusion

References

- Lambert, C.-H.; Mangin, S.; Varaprasad, B.S.D.C.S.; Takahashi, Y.K.; Hehn, M.; Cinchetti, M.; Malinowski, G.; Hono, K.; Fainman, Y.; Aeschlimann, M.; et al. All-Optical Control of Ferromagnetic Thin Films and Nanostructures. SCIENCE 2014, 345, 1337–1340. [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Yu, Z.; Liu, V.; Fan, S. Ultracompact Nonreciprocal Optical Isolator Based on Guided Resonance in a Magneto-Optical Photonic Crystal Slab.

- Irvine, S.E.; Elezzabi, A.Y. A Miniature Broadband Bismuth-Substituted Yttrium Iron Garnet Magneto-Optic Modulator. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2003, 36, 2218. [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, A.; Manera, M.G.; Borovkov, V.; Giancane, G.; Valli, L.; Rella, R. Enhanced Sensing Properties of Cobalt Bis-Porphyrin Derivative Thin Films by a Magneto-Plasmonic-Opto-Chemical Sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 246, 1039–1048. [CrossRef]

- Belyaev, V.K.; Rodionova, V.V.; Grunin, A.A.; Inoue, M.; Fedyanin, A.A. Magnetic Field Sensor Based on Magnetoplasmonic Crystal. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7133. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, C.; Song, Y. The Optical Cavity Enhanced Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect Signals of AAO/Al-Based CoFeB Nanostructure Arrays. Opt. Commun. 2019, 437, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Ding, X.; Pernod, P.; Tiercelin, N.; Song, Y. Tunable Magneto-Optical Kerr Effects of Nanoporous Thin Films. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2888. [CrossRef]

- Lou, P.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Song, Y. Enhanced Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect via the Synergistic Effect of Surface Plasmon Resonance and Spin–Orbit Coupling in Au@Pt Nanohybrid Layers. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2023, 56, 375001. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cui, X.; Zhu, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Song, Y. Hybrid Magneto-Plasmonic Structure Consisting of Hexagonal Periodic Nanodisks Array with Giant Transverse Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect for Sensing Application. J. Phys. -Appl. Phys. 2024, 57, 355004. [CrossRef]

- Ostroverkhova, O. Organic Optoelectronic Materials: Mechanisms and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 13279–13412. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Mehboob, M.Y.; Khan, M.U.; Khalid, M.; Irshad, Z.; Fatima, R.; Anwar, A.; Nawab, S.; Adnan, M. Efficient Designing of Triphenylamine-Based Hole Transport Materials with Outstanding Photovoltaic Characteristics for Organic Solar Cells. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 5113–5131. [CrossRef]

- Bodaghifard, M.A.; Hamidinasab, M.; Ahadi, N. Recent Advances in the Preparation and Application of Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Magnetic Nanocatalysts on Multicomponent Reactions. Curr. Org. Chem. 2018, 22, 234–267. [CrossRef]

- Najahi Mohammadizadeh, Z.; Hamidinasab, M.; Ahadi, N.; Bodaghifard, M.A. A Novel Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Nanomaterial: Preparation, Characterization and Application in Synthesis of Diverse Heterocycles. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022, 42, 1282–1301. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; He, Q.; Jiang, C. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Surface Functionalization Strategies. NANOSCALE Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 397–415. [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, F.D.; Balan, V.; Tanase, C.-E.; Popa, I.M.; Butnaru, M.; Bredetean, O.; Mares, M.; Nastasa, V.; Pasca, S.; Verestiuc, L. Development and Characterisation of Microporous Biomimetic Scaffolds Loaded with Magnetic Nanoparticles as Bone Repairing Material. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 11209–11219. [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.H.; Nagahara, L.A.; Thundat, T.; Mokarian-Tabari, P.; Furukawa, H.; Khosla, A. Review-Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Functional Materials: An Integrated Platform for Applied Technologies. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, B3137–B3156. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-S.; Tsai, S.C.; Kuo, C.C.; Chan, W.L.; Lin, W.H.; Wu, Y.S.; Lin, Y.S.; Li, M.H.; Kuo, M.-Y.; Chen, H. Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Nanostructures of Polycrystalline Perylene Diimide Decorated ZnO Nanorods Highly Enhanced Dual Sensing Performance of UV Light/CO Gas Sensors. RESULTS Phys. 2021, 24, 104173. [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Wang, S.; Xu, T.; Tang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wan, M.; Ai, Q.; Si, J.; Yao, X.; Cao, Y.; et al. Mn4+ Doped Zero-Dimensional Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Material with Narrow-Red Emission. J. Lumin. 2020, 228, 117661. [CrossRef]

- Bergenti, I.; Dediu, V. Spinterface: A New Platform for Spintronics. Nano Mater. Sci. 2019, 1, 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Barraud, C.; Seneor, P.; Mattana, R.; Fusil, S.; Bouzehouane, K.; Deranlot, C.; Graziosi, P.; Hueso, L.; Bergenti, I.; Dediu, V.; et al. Unravelling the Role of the Interface for Spin Injection into Organic Semiconductors. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6, 615–620. [CrossRef]

- Argyres, P.N. Theory of the Faraday and Kerr Effects in Ferromagnetics. Phys. Rev. 1955, 97, 334–345. [CrossRef]

- Normani, S.; Bertolotti, P.; Bisio, F.; Magnozzi, M.; Carboni, F.F.; Filattiera, S.; Perotto, S.; Marangi, F.; Lanzani, G.; Scotognella, F.; et al. Tamm Plasmon Resonance as Optical Fingerprint of Silver/Bacteria Interaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 27750–27758. [CrossRef]

- Auguié, B.; Fuertes, M.C.; Angelomé, P.C.; Abdala, N.L.; Soler Illia, G.J.A.A.; Fainstein, A. Tamm Plasmon Resonance in Mesoporous Multilayers: Toward a Sensing Application. ACS Photonics 2014, 1, 775–780. [CrossRef]

- Sreekanth, K.V.; Sreejith, S.; Han, S.; Mishra, A.; Chen, X.; Sun, H.; Lim, C.T.; Singh, R. Biosensing with the Singular Phase of an Ultrathin Metal-Dielectric Nanophotonic Cavity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 369. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Kang, T.; Lu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, P.; Wang, X.; et al. Ultrahigh Figure-of-Merit in Metal–Insulator–Metal Magnetoplasmonic Sensors Using Low Loss Magneto-Optical Oxide Thin Films. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 1403–1412. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Feng, G.N.; Xu, X.L.; Yang, C.; Jia, Y.L.; Yu, G.H. Tunable Damping-like and Field-like Spin-Orbit-Torque in Pt/Co/HfO2 Films via Interfacial Charge Transfer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 115, 172403. [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Yun, J.; Yang, K.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, D.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xi, L.; et al. Current Induced Magnetization Switching in Pt/Co/Cr Structures with Enhanced Perpendicular Magnetic Anisotropy and Spin Hall Effect. Appl. Phys. Express 2019, 12, 043001. [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. Measurement of Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect Using Piezo-Birefringent Modulator. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 20, 2403. [CrossRef]

- Azzam, R.M.A.; Bashara, N.M. Ellipsometry and Polarised Light.

- Polisetty, S.; Scheffler, J.; Sahoo, S.; Wang, Y.; Mukherjee, T.; He, X.; Binek, Ch. Optimization of Magneto-Optical Kerr Setup: Analyzing Experimental Assemblies Using Jones Matrix Formalism. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2008, 79, 055107. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Sánchez, R.; García-Martín, J.M.; Briones, F.; Costa-Krämer, J.L. Domain Structure and Reversal Mechanisms through Diffracted Magneto-Optics in Fe80B20 Microsquare Arrays. Magnetochemistry 2020, 6, 50. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Krämer, J.L.; Alvarez-Sánchez, R.; Bengoechea, A.; Torres, F.; García-Mochales, P.; Briones, F. Diffractive Magneto-Optics, Magnetic Interactions, and Reversal Mechanisms in Co Microsquare Arrays. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 104420. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, G.; Molenkamp, L.W. Spin Injection into Semiconductors, Physics and Experiments. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2002, 17, 310. [CrossRef]

- Kunitski, M.; Eicke, N.; Huber, P.; Köhler, J.; Zeller, S.; Voigtsberger, J.; Schlott, N.; Henrichs, K.; Sann, H.; Trinter, F.; et al. Double-Slit Photoelectron Interference in Strong-Field Ionization of the Neon Dimer. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.J.; Coleman, L.B.; Garito, A.F.; Heeger, A.J. Electrical Conductivity of Tetrathiofulvalinium Tetracyanoquinodimethan (TTF) (TCNQ). Phys. Rev. B 1974, 10, 1298–1307. [CrossRef]

- Perrin, M.L.; Verzijl, C.J.O.; Martin, C.A.; Shaikh, A.J.; Eelkema, R.; Van Esch, J.H.; Van Ruitenbeek, J.M.; Thijssen, J.M.; Van Der Zant, H.S.J.; Dulić, D. Large Tunable Image-Charge Effects in Single-Molecule Junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 282–287. [CrossRef]

- Galbiati, M.; Tatay, S.; Barraud, C.; Dediu, A.V.; Petroff, F.; Mattana, R.; Seneor, P. Spinterface: Crafting Spintronics at the Molecular Scale. MRS Bull. 2014, 39, 602–607. [CrossRef]

- Ceresoli, D.; Gerstmann, U.; Seitsonen, A.P.; Mauri, F. First-Principles Theory of Orbital Magnetization. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 060409. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Cline, R.P.; Schwan, J.; Strain, J.M.; Roberts, S.T.; Mangolini, L.; Eaves, J.D.; Tang, M.L. Efficient Photon Upconversion Enabled by Strong Coupling between Silicon Quantum Dots and Anthracene. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 1172–1178. [CrossRef]

- Bao G.; Deng R.; Jin D.; Liu X. Hidden triplet states at hybrid organic–inorganic interfaces. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bie, Q.S.; Lu, M.; Du, J.; Zhao, H.W.; Xia, K.; Zhai, H.R.; Zhou, S.M.; Jin, Q.Y.; Chen, L.Y. Complex Optical Constants and Magneto-Optic Kerr Effect of Co/Al/Co Sandwiches. Phys. Lett. A 1996, 210, 341–346. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, K.; Hattori, S.; Kitagawa, Y. Recent Advances in Studies on the Magneto-Chiral Dichroism of Organic Compounds. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 9–19. [CrossRef]

- Moone, L.; Donners, M.P.J.; Van Durme, K.; Okhrimenko, D.V.; Van Benthem, R.A.T.M.; Tuinier, R.; Esteves, A.C.C. Surface Characteristics of Phenolic Resin Coatings. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 45, 103840. [CrossRef]

- Schuster, C.; Rennhofer, H.; Amenitsch, H.; Lichtenegger, H.C.; Jungbauer, A.; Tscheliessing, R. Metal–Insulator Transition of Ultrathin Sputtered Metals on Phenolic Resin Thin Films: Growth Morphology and Relations to Surface Free Energy and Reactivity. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 589. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).