1. Introduction

3D Mechatronic Integrated Devices (3D-MID) can effectively integrate mechanical, thermal, optical, and electrical functions due to their geometric design flexibility and the combination of selective structuring and metallization. This renders them widely utilized in various applications, such as automotive, medical technology, IT and telecommunications, and industrial automation [

1]. Due to the unique three-dimensional structure and small batch production characteristics of 3D-MID components, the traditional injection molding process for manufacturing circuit carriers faces challenges such as high costs, limited design flexibility, long production cycles, and difficulty in handling complex geometries, all of which have become bottlenecks in the development of 3D-MID technology [

2]. An innovative and rapid method for producing 3D-MID is to use additive manufacturing technology (AM) that requires no molding tools. Additive manufacturing for 3D-MID not only compensates for the high initial cost of injection molds, but also offers greater design flexibility and faster production cycles [

3]. Currently, extensive work is primarily focused on 3D-MID based on Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) additive manufacturing technologies [

2,

4,

5]. In order to further expand the application fields of 3D-MID, SLA technology, which offers higher precision and better material properties, can be utilized. High-performance resins used in SLA, such as heat-resistant and high-strength resins, can enhance the performance of 3D-MID components, making them more suitable for demanding environments. The use of these resins extends the stability and reliability of 3D-MID components under high temperature or mechanical loads [

6,

7,

8].

In this work, circuit carriers are manufactured by mixing LDS additives with heat-resistant resin and utilizing SLA 3D printing technology. Taking Temperature Measurement Systems as an example, after the LDS process and metallization, the circuit layout on the circuit carrier is successfully achieved. The introduction of vias and the use of smaller packaged components effectively realize circuit miniaturization.

To verify the feasibility of SLA-3D-MID components in practical applications, the relationship between laser structuring parameters and the resistance of circuits and vias is analyzed using the Response Surface Methodology (RSM). For soldering, Vapor Phase Soldering (VPS) and Reflow Soldering are employed to solder the populated SLA-3D-MID components, ultimately producing SLA-3D-MID parts free of cracks.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this study explores the miniaturization of 3D-MID components facilitated by SLA 3D printing technology. The focus on circuit miniaturization includes the introduction of vias, reduction of trace spacing, and implementation of chips with smaller packaging, such as BGA and QFN. RSM experimental design and screening experiments optimize laser parameters, revealing that excessive operating power leads to over-metalization. Pre-treatment with Enplate LDS Cleaner 300 solution effectively reduces these over-metalization effects. Notably, the width of the circuit lines is not a primary target for miniaturization; instead, the arrangement of electronic components, adoption of smaller chip packages, and strategic circuit configurations are crucial in determining the overall size of the circuit carriers. Furthermore, a minimum spacing of 150 µm between circuits is established. Consequently, the components based on SLA 3D printing technology for 3D-MID show immense potential for advancing miniaturization, which not only supports the integration of complex circuits and precise wiring but also significantly enhances the development of miniature electronic devices and systems.

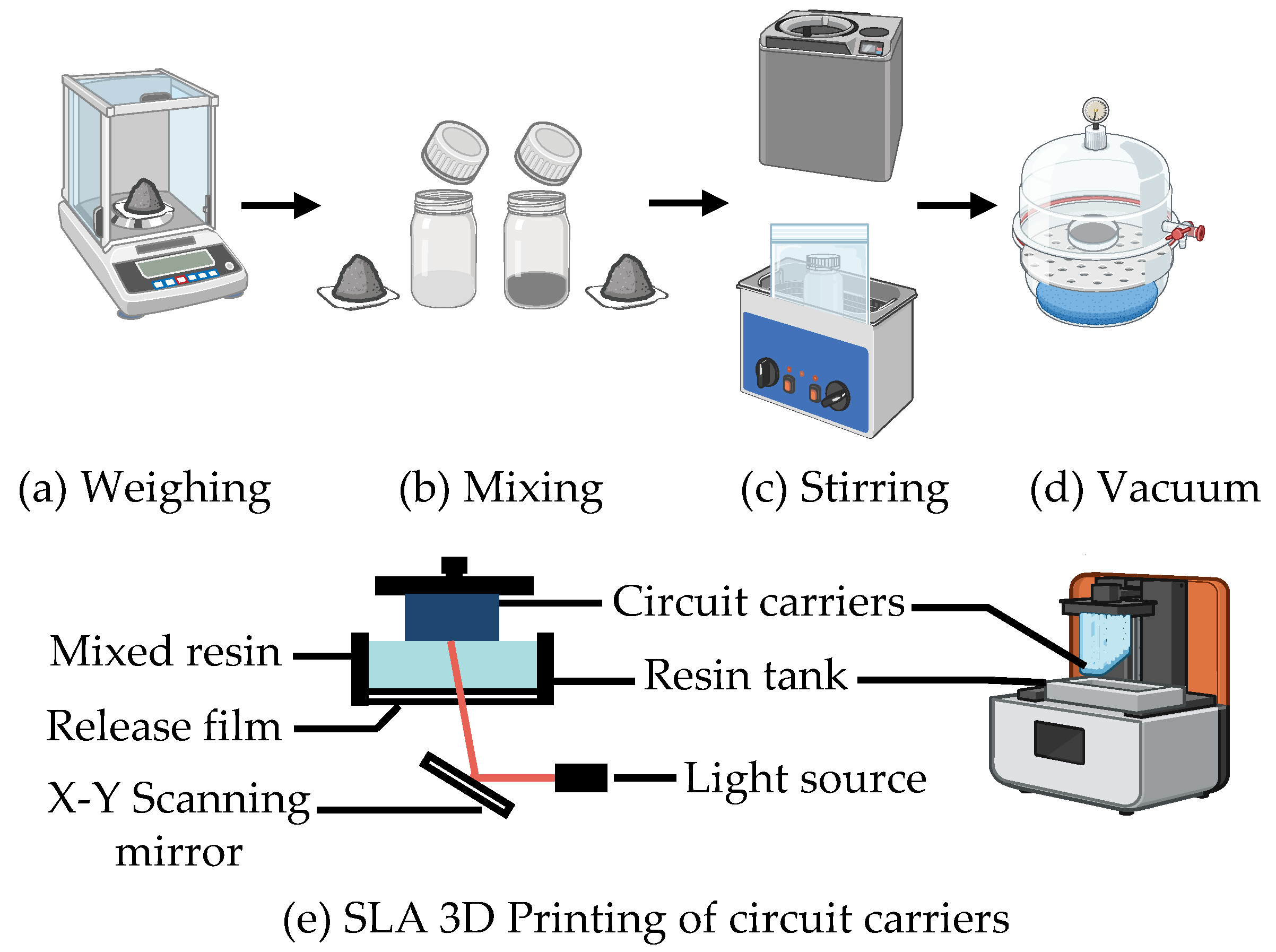

Figure 1.

Resin Mixing and Circuit Carrier Printing.

Figure 1.

Resin Mixing and Circuit Carrier Printing.

Figure 2.

The circuit board with U2 in a (a) QFN package and (b) BGA package. (c) Schematic diagram of the circuit board area.

Figure 2.

The circuit board with U2 in a (a) QFN package and (b) BGA package. (c) Schematic diagram of the circuit board area.

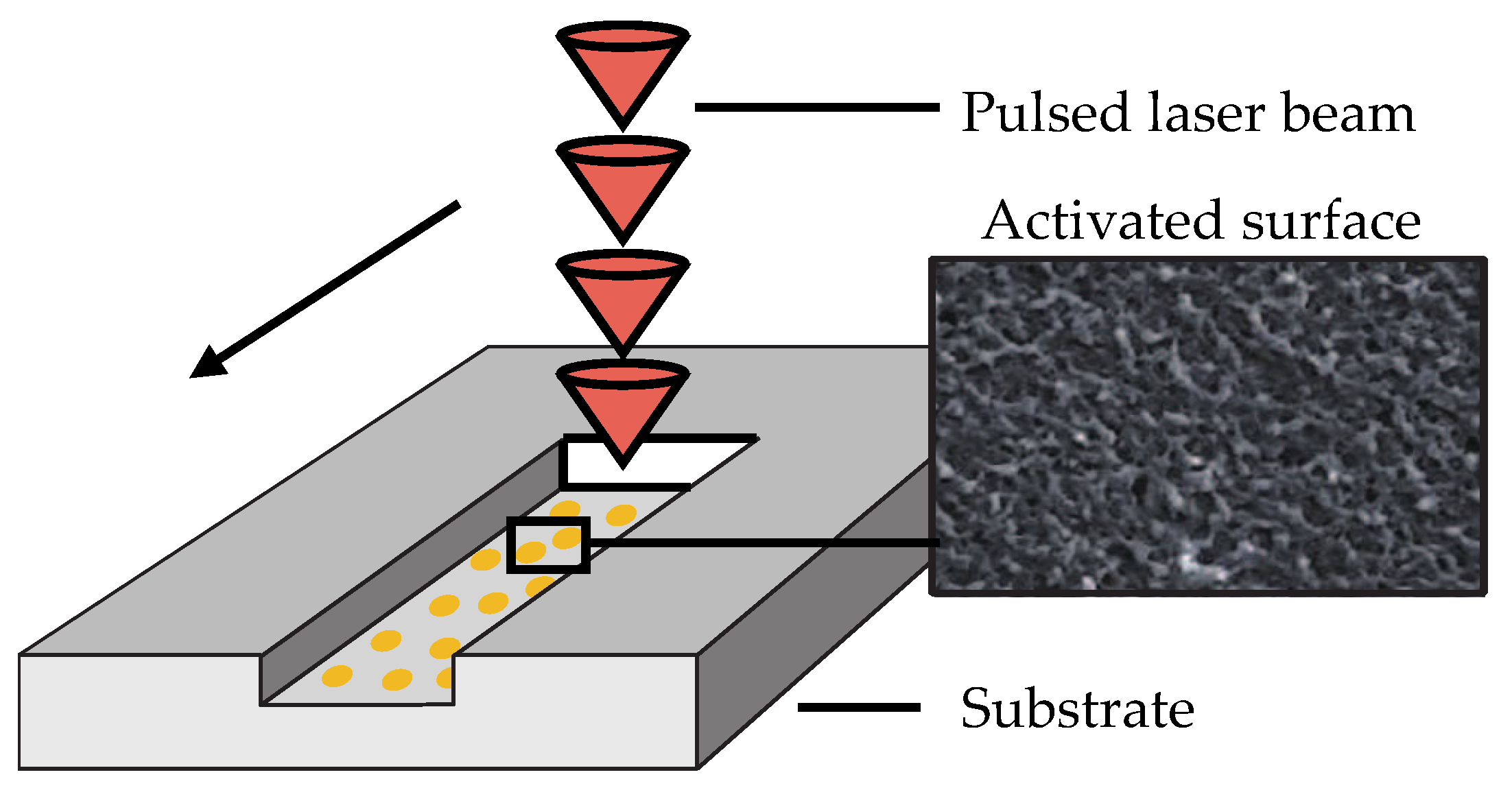

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of laser activation. [

11]

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of laser activation. [

11]

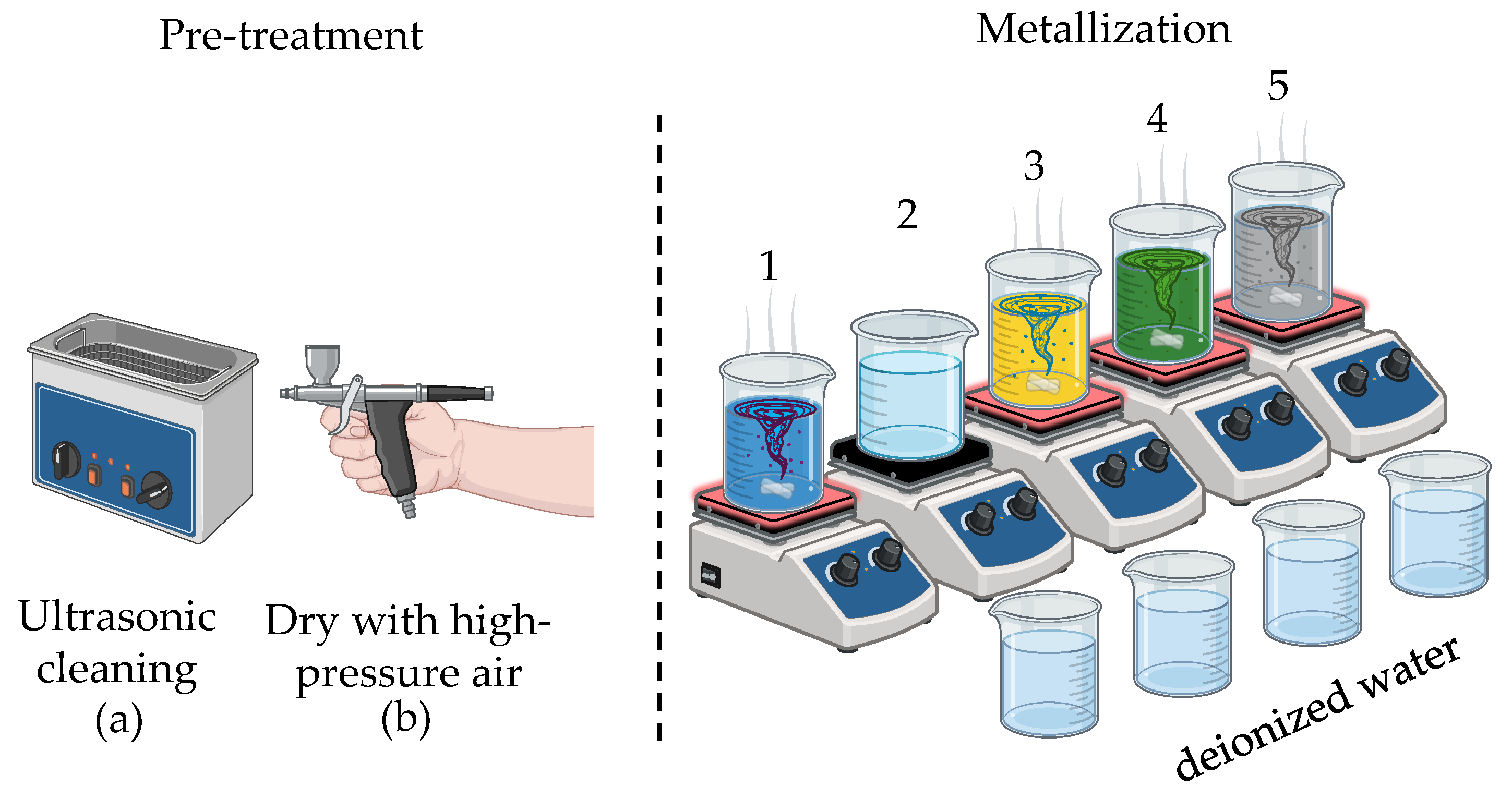

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the metallization process.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the metallization process.

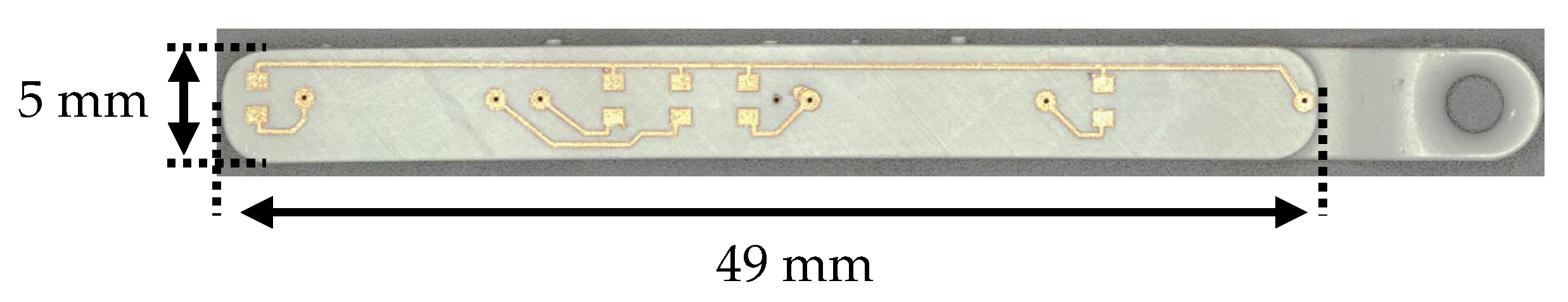

Figure 5.

Schematic Diagram of Sensor Circuit Carrier Dimensions.

Figure 5.

Schematic Diagram of Sensor Circuit Carrier Dimensions.

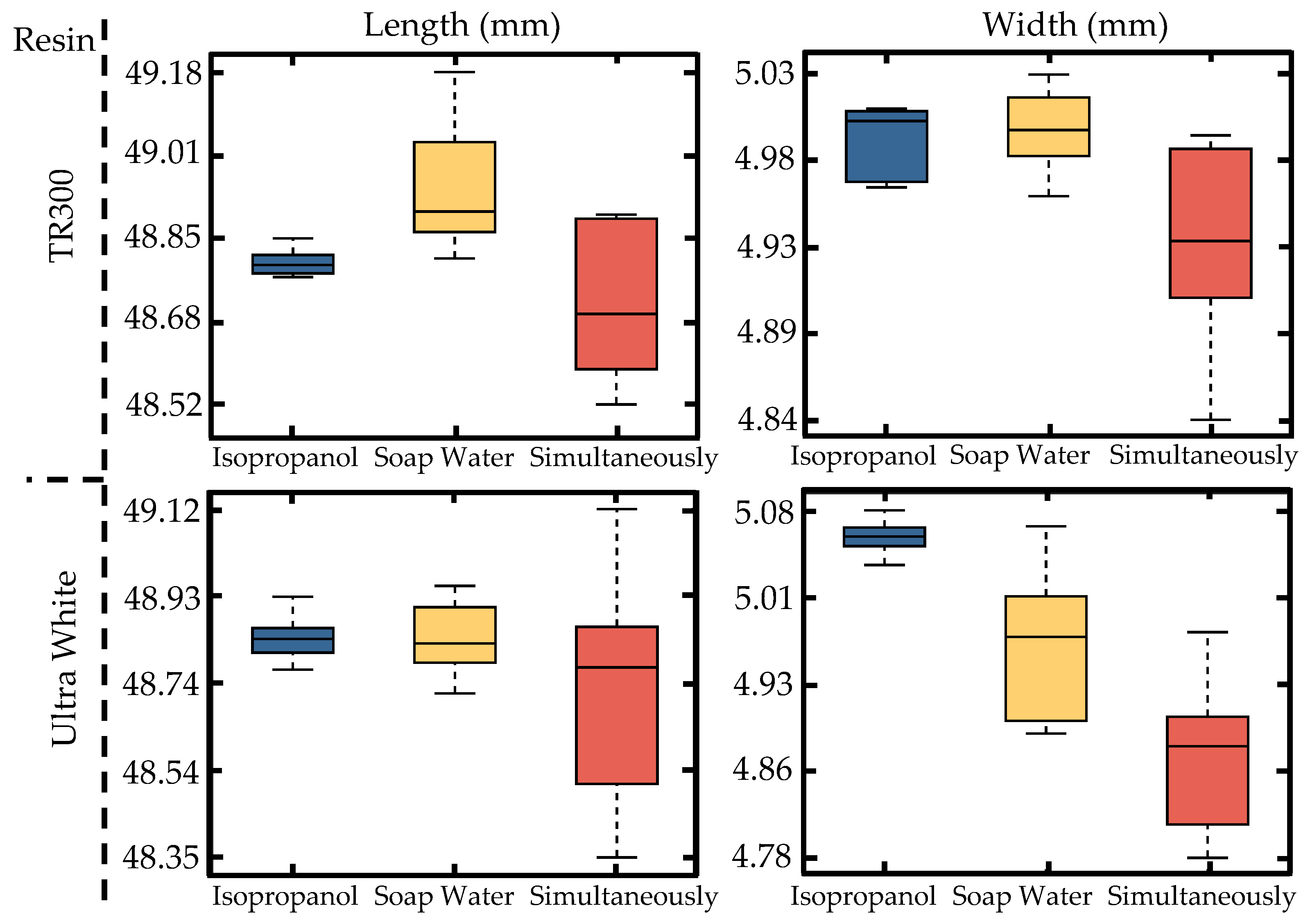

Figure 6.

Box Plot of the Impact of Different Post-Processing Methods on Circuit Carrier Dimensions.

Figure 6.

Box Plot of the Impact of Different Post-Processing Methods on Circuit Carrier Dimensions.

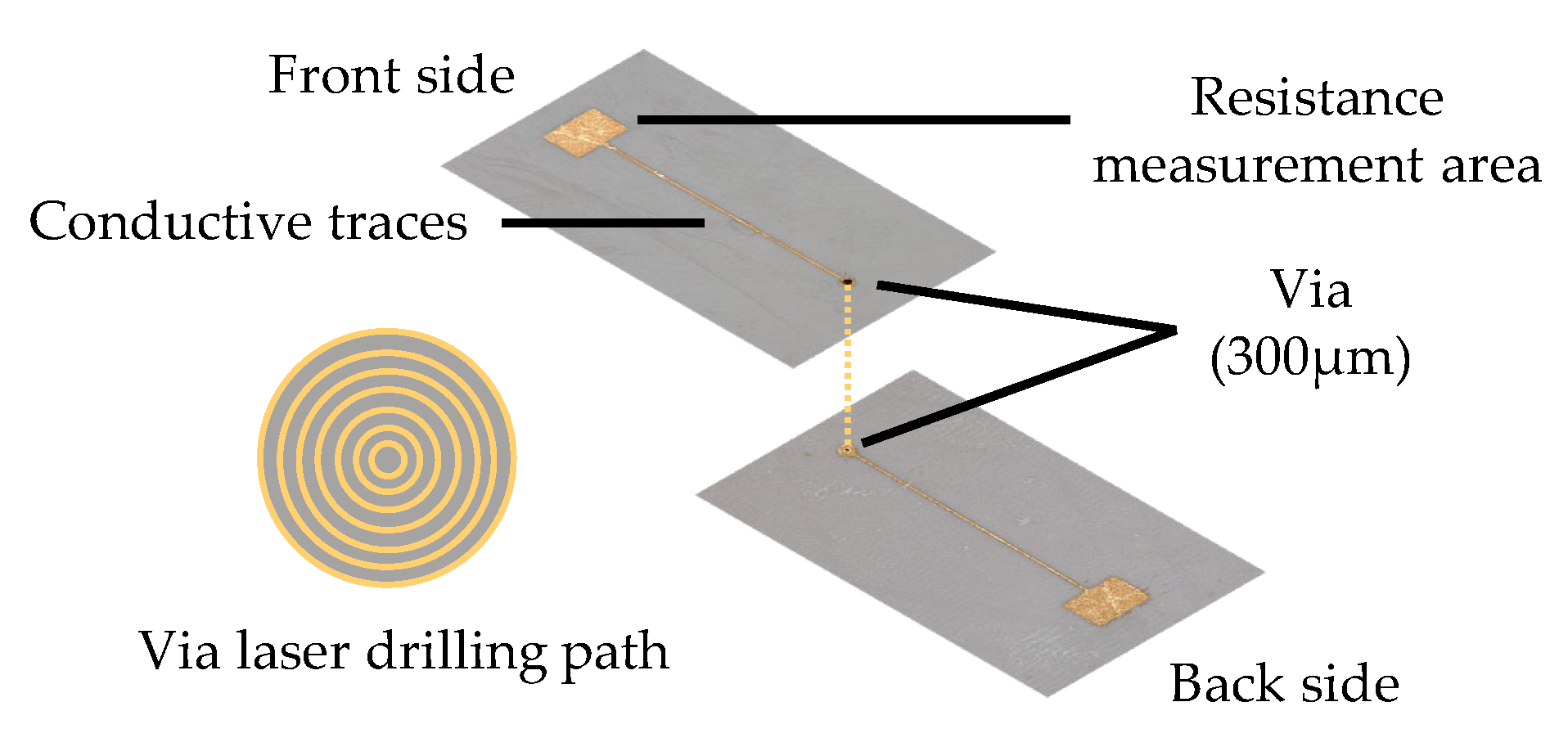

Figure 7.

Schematic Diagram of Via Hole in the Circuit Carrier.

Figure 7.

Schematic Diagram of Via Hole in the Circuit Carrier.

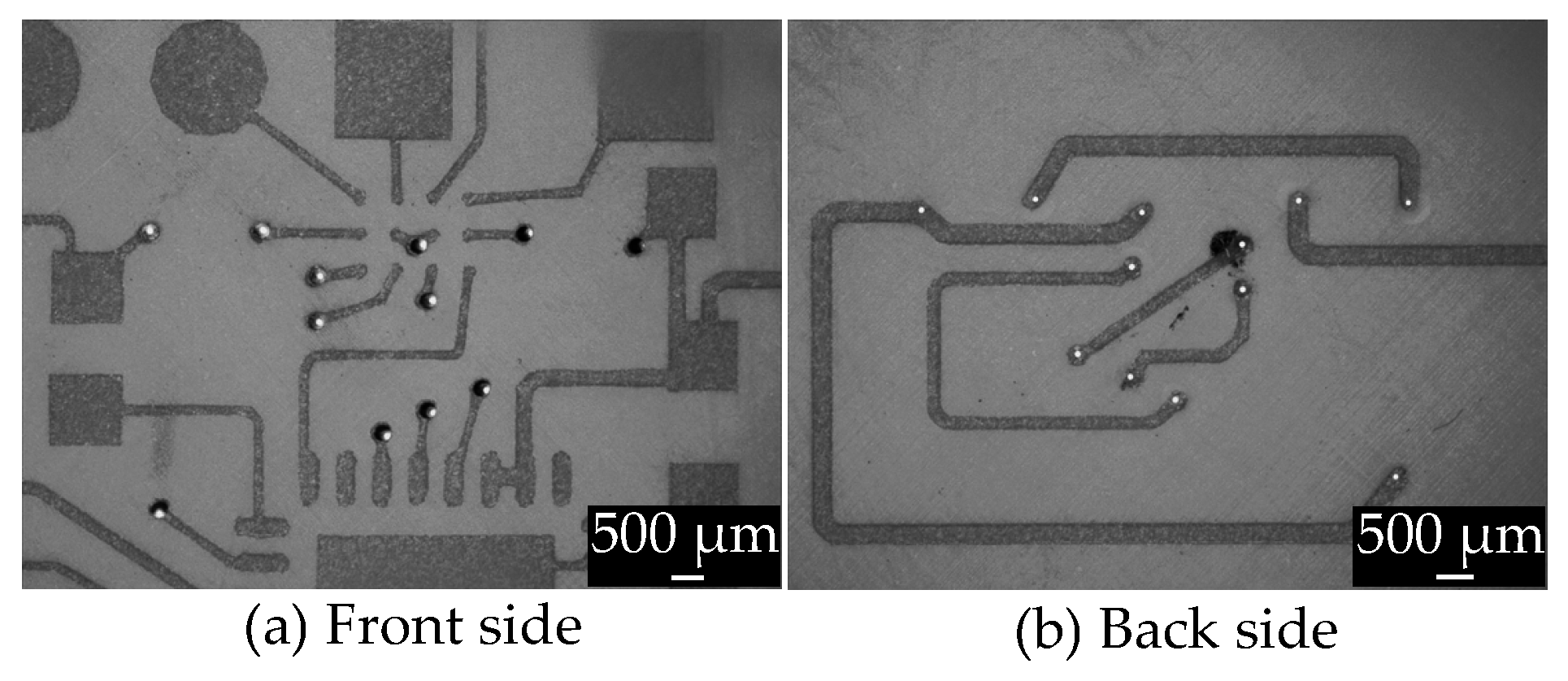

Figure 8.

Microscopic Close-Up of Via Holes in the Circuit.

Figure 8.

Microscopic Close-Up of Via Holes in the Circuit.

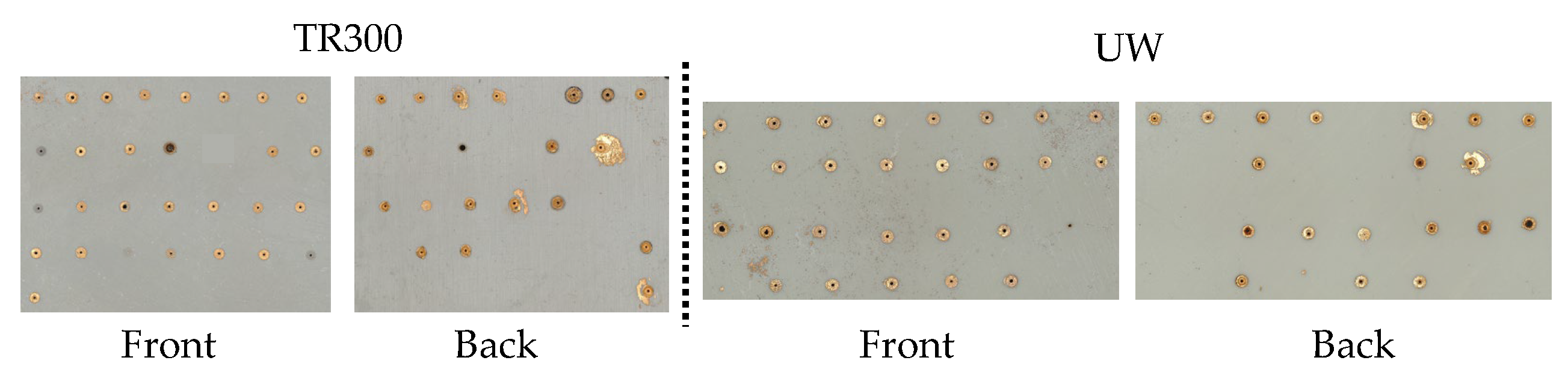

Figure 9.

Experimental Substrate with Via Holes for TR300 and UW.

Figure 9.

Experimental Substrate with Via Holes for TR300 and UW.

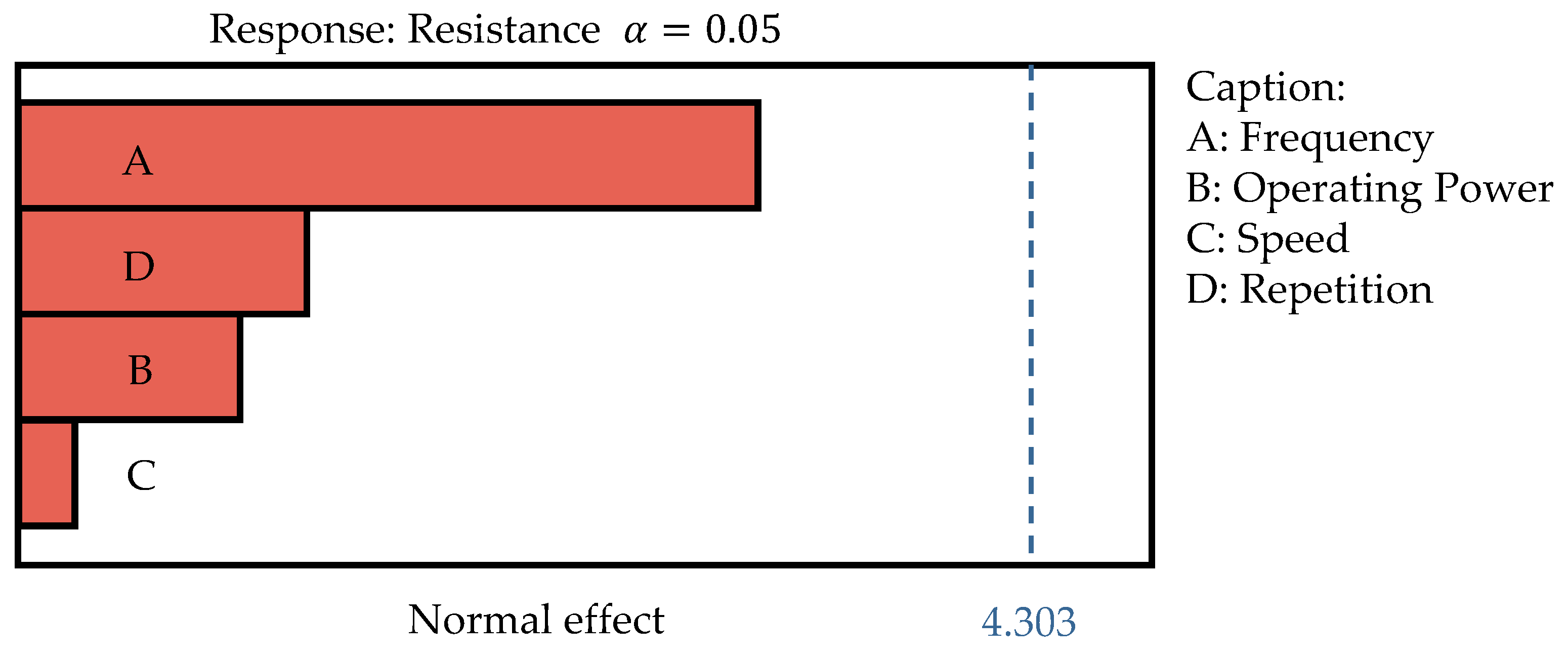

Figure 10.

Pareto Chart Analysis of Via Holes’ Resistances on TR300 Substrate.

Figure 10.

Pareto Chart Analysis of Via Holes’ Resistances on TR300 Substrate.

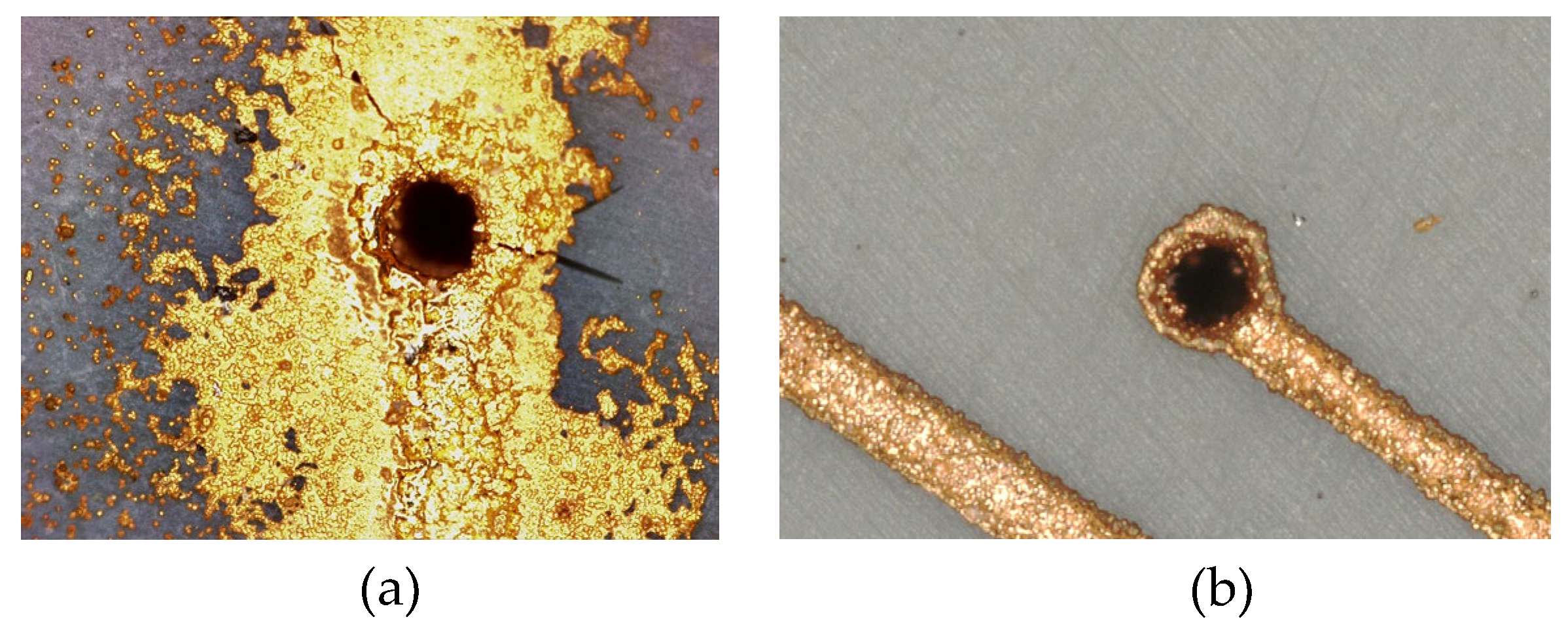

Figure 11.

(a) Via hole showing excessive metallization around the surrounding area; (b) Via hole showing no excessive metallization around the surrounding area.

Figure 11.

(a) Via hole showing excessive metallization around the surrounding area; (b) Via hole showing no excessive metallization around the surrounding area.

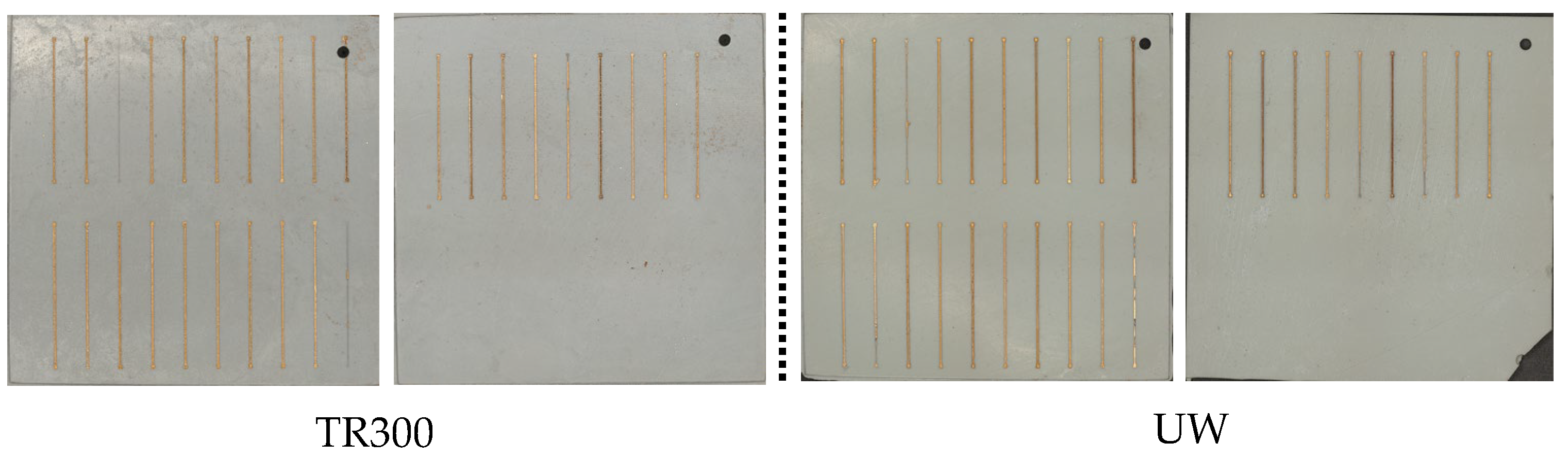

Figure 12.

Experimental Substrate with traces for TR300 and UW.

Figure 12.

Experimental Substrate with traces for TR300 and UW.

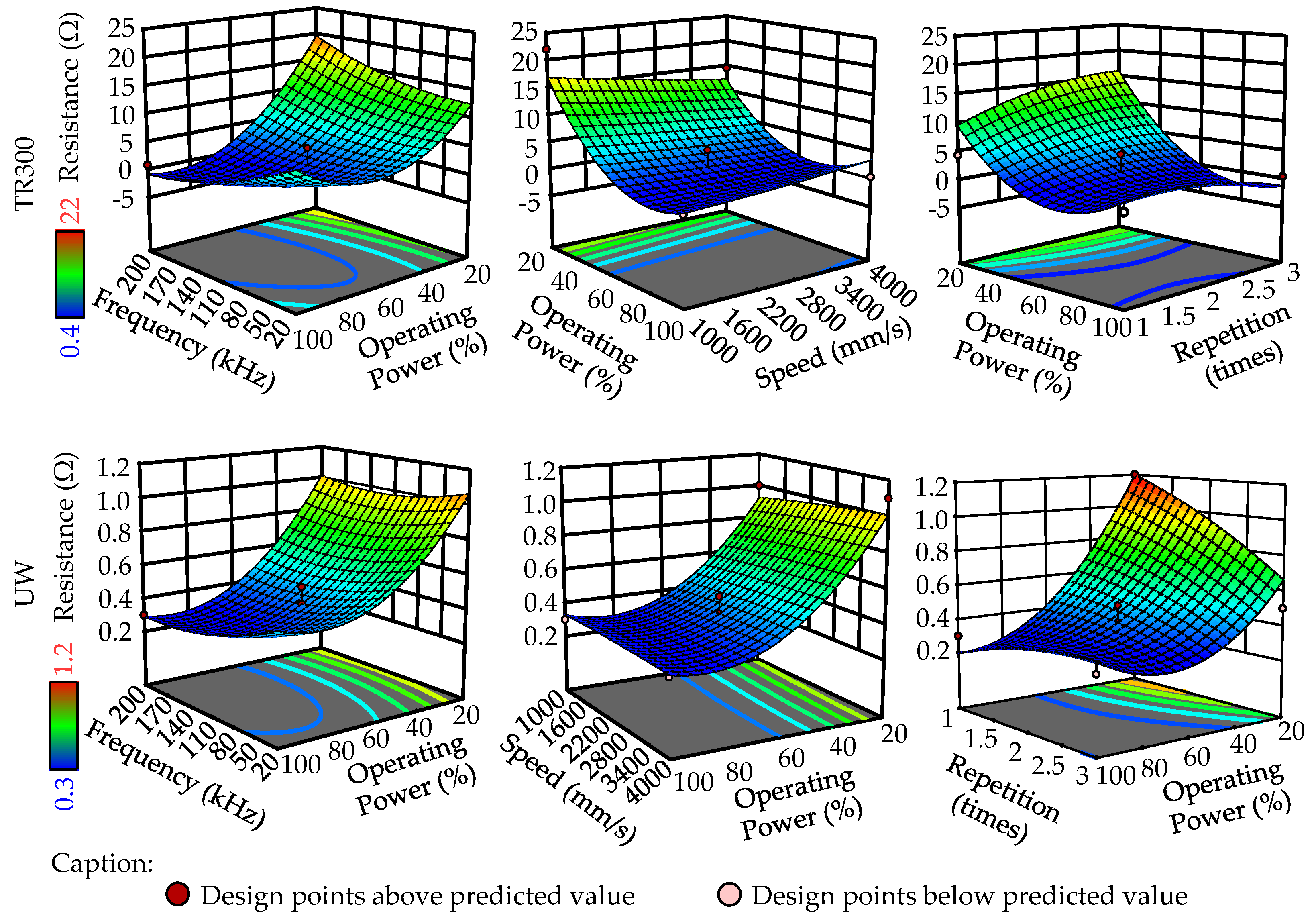

Figure 13.

3D Response Surface Plot of Resistance for Different Factors between TR300 and UW.

Figure 13.

3D Response Surface Plot of Resistance for Different Factors between TR300 and UW.

Figure 14.

(a) Perfect Circuit and (b) Over-metallized Circuit.

Figure 14.

(a) Perfect Circuit and (b) Over-metallized Circuit.

Figure 15.

Design of experimental structure for minimum circuit spacing.

Figure 15.

Design of experimental structure for minimum circuit spacing.

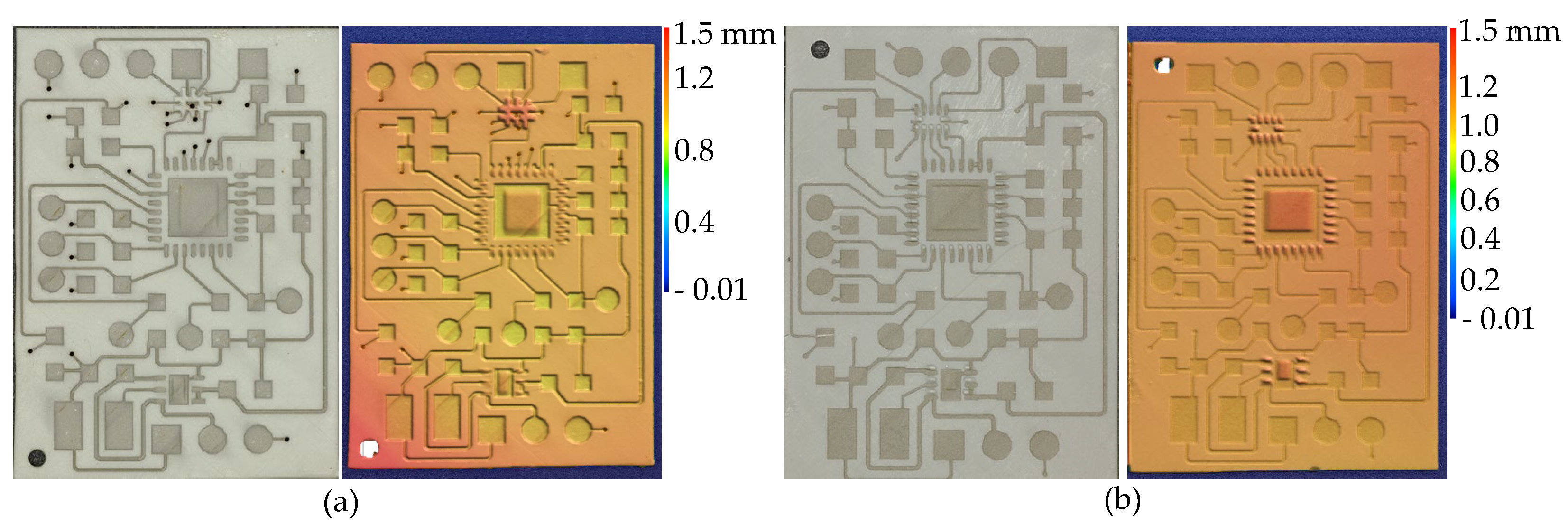

Figure 16.

The circuit on the (a) traditional circuit board and (b) SLA-printed Circuit Carrier.

Figure 16.

The circuit on the (a) traditional circuit board and (b) SLA-printed Circuit Carrier.

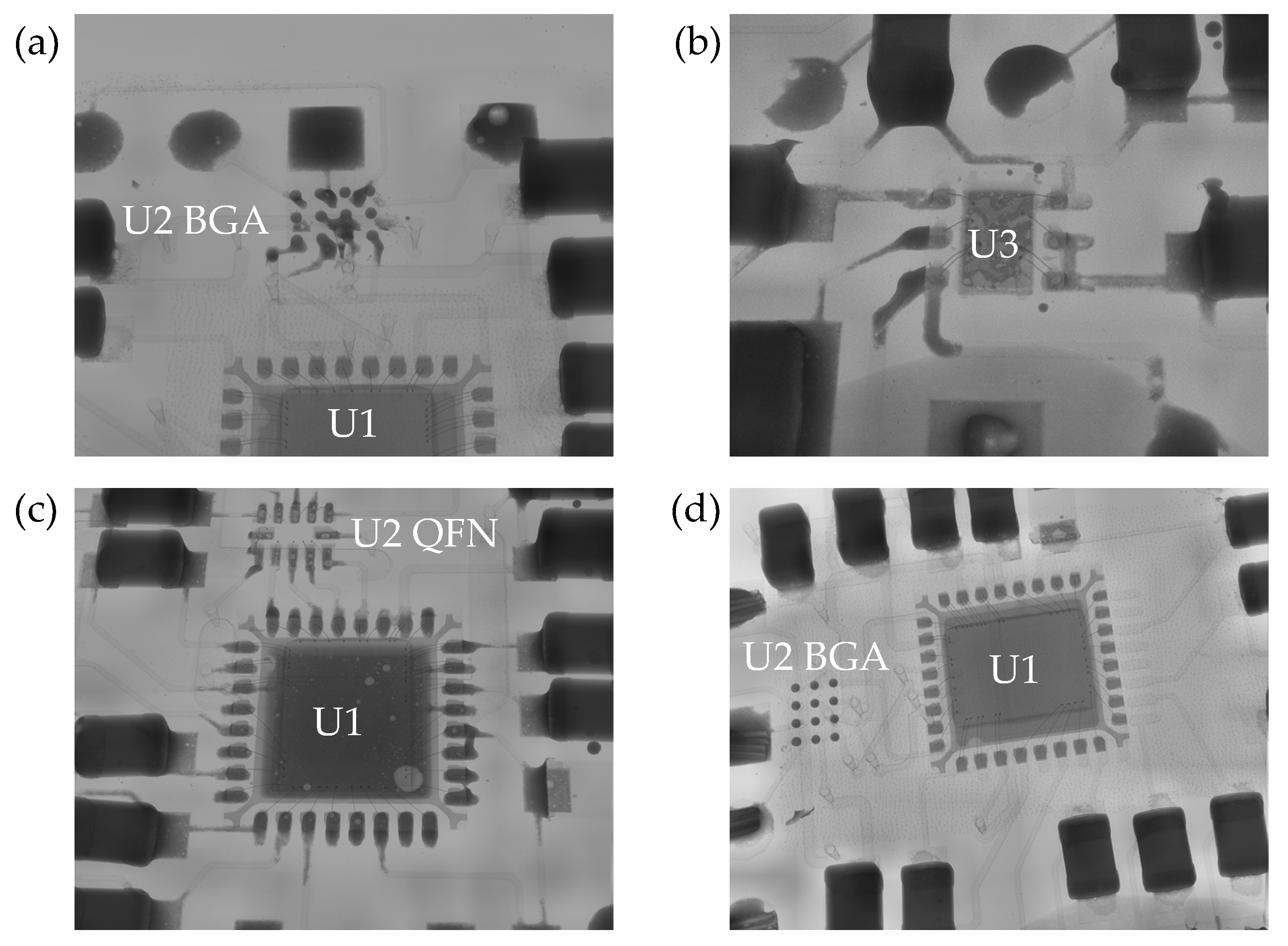

Figure 17.

The front (a) and back (b) views of the miniaturized circuit using a QFN package (UW), and the front (c) and back (d) views of the miniaturized circuit using a BGA package (TR300).

Figure 17.

The front (a) and back (b) views of the miniaturized circuit using a QFN package (UW), and the front (c) and back (d) views of the miniaturized circuit using a BGA package (TR300).

Figure 18.

Chip packages used in the original circuit and the miniaturized circuit.

Figure 18.

Chip packages used in the original circuit and the miniaturized circuit.

Figure 19.

(a) Solder paste stencil, (b) Circuit board with applied solder paste.

Figure 19.

(a) Solder paste stencil, (b) Circuit board with applied solder paste.

Figure 20.

(a) Cracks on the circuit board (Material: UW), (b) Flow of solder along the circuit.

Figure 20.

(a) Cracks on the circuit board (Material: UW), (b) Flow of solder along the circuit.

Figure 21.

The complete circuit board.

Figure 21.

The complete circuit board.

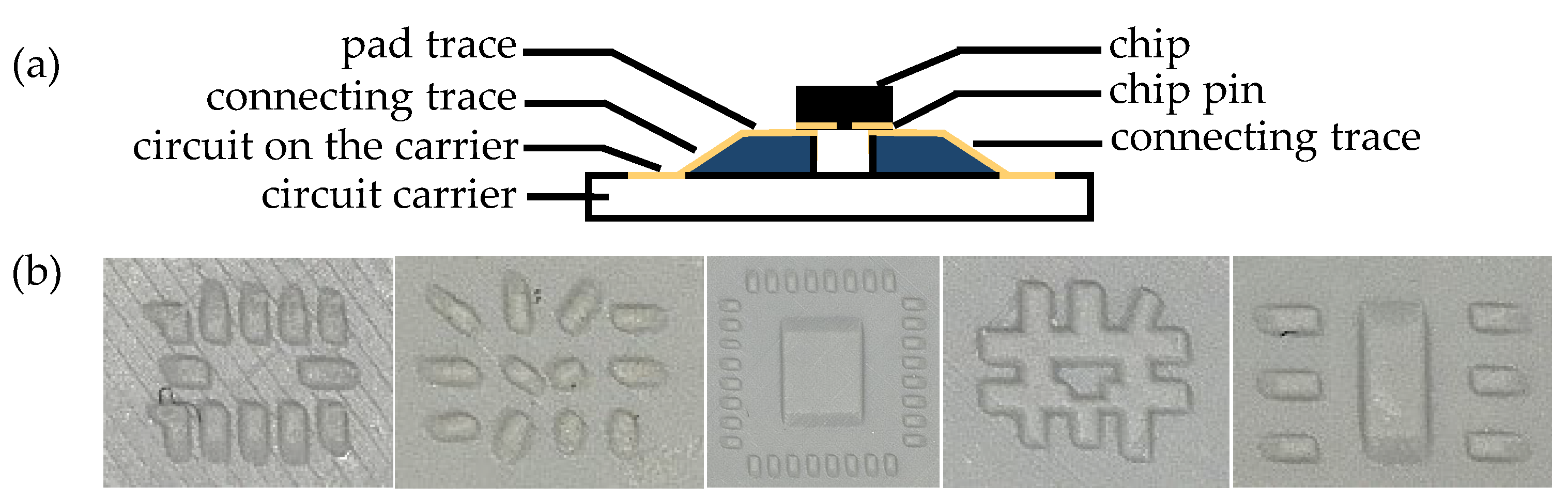

Figure 22.

(a) Schematic Diagram of 3D Pads, (b) Real-life Images of 3D Pads for Different Chips.

Figure 22.

(a) Schematic Diagram of 3D Pads, (b) Real-life Images of 3D Pads for Different Chips.

Figure 23.

Using 3D pads on circuits with (a) BGA /(b) QFN packaged chips.

Figure 23.

Using 3D pads on circuits with (a) BGA /(b) QFN packaged chips.

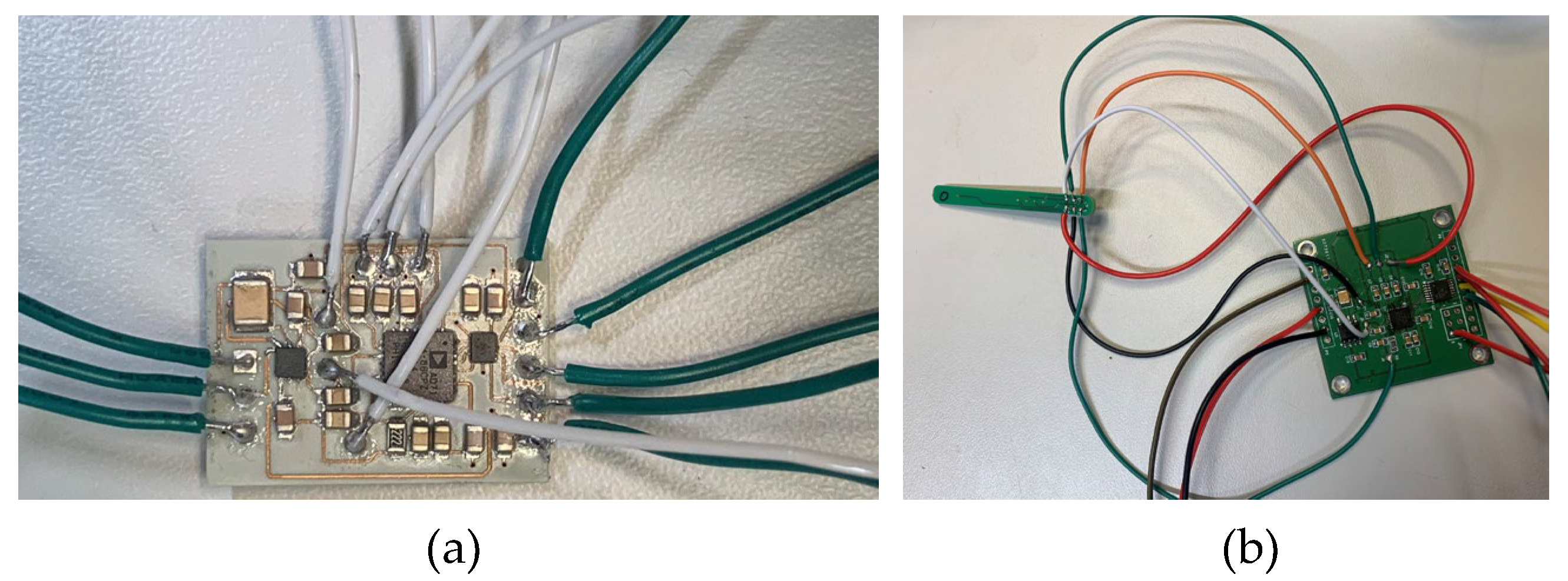

Figure 24.

(a) Wire connections on the SLA-MID circuit board, (b) Validation circuit (standard PCB board).

Figure 24.

(a) Wire connections on the SLA-MID circuit board, (b) Validation circuit (standard PCB board).

Figure 25.

X-ray scan of the resin circuit board.

Figure 25.

X-ray scan of the resin circuit board.

Table 1.

The Mixing Ratio and Stirring Method of the Resin.

Table 1.

The Mixing Ratio and Stirring Method of the Resin.

| Resin |

LDS Additives |

Stirring Method |

| Phrozen TR300 (TR300) |

3% |

Planetary Mixer and Ultrasonic Water Bath |

| Siraya Tech Ultra White (UW) |

3% |

Planetary Mixer and Ultrasonic Water Bath |

Table 2.

First-Layer and Normal Layer Exposure Times for Mixed Resin.

Table 2.

First-Layer and Normal Layer Exposure Times for Mixed Resin.

| Resin |

First-Layer (s) |

Normal Layer (s) |

| TR300 |

75 |

1.2 |

| UW |

55 |

2.5 |

Table 3.

The names and areas of the electronic components.

Table 3.

The names and areas of the electronic components.

| No. |

Name |

Area (mm2) |

| C1, C5 - C14, C16 - C19 |

Capacitance |

3 |

| C15 |

Capacitance |

11.9 |

| J1 - J6 |

Measurement Point |

2.7 |

| R5 |

Resistance |

3 |

| JP1 |

- |

2.7 |

| P5 |

Pin header |

11 |

| P8 |

Pin header |

16 |

| U1 |

Chip |

31.3 |

| U2 BGA/U2 QFN |

Chip |

2/3.42 |

| U3 |

Chip |

5 |

Table 4.

Summary of Metallization Process Operating Steps.

Table 4.

Summary of Metallization Process Operating Steps.

| Number in Fig. 8 |

Solution |

Temperature (∘C) |

Time |

| 1 |

Copper |

55 |

60 min |

| 2 |

Acid |

- |

30 s |

| 3 |

Palladium |

- |

1 min |

| 4 |

Nickel |

62 |

60 min |

| 5 |

Gold |

90 |

30 min |

Table 5.

Factors and Levels in the RSM Method (Via).

Table 5.

Factors and Levels in the RSM Method (Via).

| Factor |

Level |

| Frequency |

20, 110, 200 (kHz) |

| Operating Power |

20, 60, 100 (%) |

| Speed |

1000, 2500, 4000 (mm/s) |

| Repetition |

750, 825, 900 (times) |

Table 6.

ANOVA Analysis of Resistance Values of Via Holes on TR300 Substrate (Excerpt).

Table 6.

ANOVA Analysis of Resistance Values of Via Holes on TR300 Substrate (Excerpt).

| Factor |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

| Model |

99.72 |

10 |

9.97 |

794.19 |

<0.0001 |

significant |

| Frequency |

0.0023 |

1 |

0.0023 |

0.1820 |

0.6845 |

|

| Operating Power |

0.0310 |

1 |

0.0310 |

2.47 |

0.1670 |

|

| Speed |

0.0023 |

1 |

0.0023 |

0.1820 |

0.6845 |

|

| Repetition |

38.48 |

1 |

38.48 |

3064.79 |

<0.0001 |

|

| ... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

| Lack of Fit |

0.0633 |

2 |

0.0317 |

10.56 |

0.0254 |

significant |

Table 7.

Laser Parameters for Via Holes on Both Resin Types.

Table 7.

Laser Parameters for Via Holes on Both Resin Types.

| Frequency (kHz) |

Operating Power (W) |

Speed (mm/s) |

Repetition (times) |

| 20 |

3.47 (100%) |

1500 |

900 |

Table 8.

Factors and Levels in the RSM Method (Circuit).

Table 8.

Factors and Levels in the RSM Method (Circuit).

| Factor |

Level |

| Frequency |

20, 110, 200 (kHz) |

| Operating Power |

20, 60, 100 (%) |

| Speed |

1000, 2500, 4000 (mm/s) |

| Repetition |

1, 2, 3 (times) |

Table 9.

ANOVA Analysis of Resistance Values of Circuits on TR300/UW (Excerpt).

Table 9.

ANOVA Analysis of Resistance Values of Circuits on TR300/UW (Excerpt).

| Factor |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

| Model |

627.22 |

14 |

44.8 |

3.93 |

0.0113 |

significant |

| Model |

1.43 |

14 |

0.1019 |

11.08 |

<0.0001 |

significant |

| Frequency |

1.62 |

1 |

1.62 |

0.1423 |

0.7126 |

|

| Frequency |

0.0313 |

1 |

0.0313 |

3.40 |

0.0901 |

| Operating Power |

347.98 |

1 |

347.98 |

30.56 |

0.0001 |

significant |

| Operating Power |

0.9425 |

1 |

0.9425 |

102.50 |

<0.0001 |

significant |

| Speed |

2.80 |

1 |

2.80 |

0.2462 |

0.6288 |

|

| Speed |

0.0033 |

1 |

0.0033 |

0.3625 |

0.5583 |

| Repetition |

8.17 |

1 |

8.17 |

0.7172 |

0.4136 |

|

| Repetition |

0.1008 |

1 |

0.1008 |

10.97 |

0.0062 |

| ... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

| Lack of Fit |

124.77 |

8 |

15.6 |

5.25 |

0.0633 |

not significant |

| Lack of Fit |

0.0903 |

8 |

0.0113 |

2.26 |

0.2248 |

not significant |

Table 10.

Laser Parameters for TR300 und UW.

Table 10.

Laser Parameters for TR300 und UW.

| Frequency (kHz) |

Operating Power (W) |

Speed (mm/s) |

Repetition (times) |

| 110 |

9.67 (60%) |

2500 |

1 |

| 110 |

9.67 (60%) |

2500 |

1 |

Table 11.

Model and Package Type of U2 and U3 in the Original Circuit.

Table 11.

Model and Package Type of U2 and U3 in the Original Circuit.

| Chip |

Model |

Package Type |

| U2 |

TXB0104PWR |

TSSOP |

| U3 |

ADP7156ARDZ-3.0-R7 |

SOIC |

Table 12.

Soldering Methods and Principles.

Table 12.

Soldering Methods and Principles.

| Machine |

Principle |

Material |

| IBL LC 280 |

Condensation Soldering |

TR300 |

| ERSA Hotflow 2/14 |

Convection Soldering |

TR300 and UW |