2. Preliminaries

SR is based on two postulates:

The principle of relativity. The laws of physics take the same form in all inertial frames of reference.

The invariance of . The speed of light in vacuum is the same for all observers, regardless of the motion of light source or observer.

These principles are not based on equal footing. The relativity principle, first formulated by Galileo and absorbed by Newtonian mechanics, is a theoretical requirement. The invariance principle was derived empirically as one of the universal constants of Nature. Both are commonly accepted in science. However, there arises an obvious tension between them. The first postulate implies that all inertial frames are equivalent, whereas the second postulate admits that light itself can be associated with its own inertial frame which will be preferred (privileged) in contrast to the relativity principle. The Lorentz ether theory (LET) was proposed as a possible candidate for this inertial frame in the form of immobile ether. Although both theories are empirically indistinguishable under Lorentz transformations, SR was preferred as a more parsimonious and aesthetic theory than does not resort to an undetectable ether of LET.

Another modification of SR is Doubly Special Relativity (DSR). DSR is inspired by the same tension between the postulates by remarking that SR indeed deserves to be qualified as “special”, where the relativity principle coexists with an observer-independent velocity scale [

5]. DSR argues that the relativity principle can coexist with observer-independent scales of both velocity (

) and Lorentz invariant minimum (Planck) length [

6]. This is viewed as a way to reconcile general relativity with quantum gravity, where spacetime might have a discrete structure different from a continuous and differentiable manifold by involving the Planck energy with crucial properties of QM such as the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. DSR can also be understood as a non-linear realization of the Lorentz group in momentum space [

7,

8].

Although both LET and DSR are alternatives to SR, the relationship between them has not been explored. Meanwhile, within DSR it was noted [

5]:

My results show that there are at least two ways for Nature to make use of the Planck length in spacetime physis: the scenario in which SR is not modified, but the Planck length is introduced together with an accompanying background (“medium”) and an accompanying class of preferred inertial observers, and the new scenario here proposed in which the Planck length is introduced without an accompanying background, but at the cost of a revision of Special Relativity in which the Planck length acquires the status of an observer-independent property of spacetime.

The former scenario, mentioned in the quotation, is now known as Einstein–aether theory. The theory extends SR by introducing a preferred reference frame coupled to a unit timelike vector field that breaks local Lorentz symmetry at very short distance scales. The preferred frame of reference combines the concept of ether from LET, and the idea of a unit timelike vector describing the ether from Dirac’s model. The theory proposes an alternative theory of gravity, and is aimed to account for dark energy in the ΛCDM model [

10]. The latter scenario, adopted by DSR, also includes de Sitter invariant SR, with an event horizon, which restricts the causal region of each observer [

9]. For large values of

, the region would be of the order of the Planck length.

This paper will demonstrate that an extended SR can mirror many features of both scenarios. Given that the invariant speed of light can be associated with a preferred inertial frame, a breaking of Lorentz symmetry at the Planck length would be inevitable for preserving consistency. The SRE can be inferred from the fundamental properties of the continuum in nonstandard mathematical analysis.

Since its inception, SR has entailed some counterintuitive peculiarities that are directly related to the speed of light:

- (i)

While the speed of light is finite, it possesses the properties of infinity. Massive objects cannot reach this speed because it would take an infinite amount of energy to accelerate an object to the speed of light by the Lorentz factor

- (ii)

There is no absolute “now’ in the universe.

- (iii)

The faster the relative velocity between two inertial fames, the greater the time dilation between their clocks. Time slows to a stop as one clock approaches the speed of light.

- (iv)

The duration of the actual present is zero as depicted by a lightlike point in Minkowski space.

The following conjecture is proposed to clarify the tension between the two postulates of SR and their four consequences.

Conjecture. The speed of light provides the reference frame at rest that is privileged in the universe.

(i) In SR, is a spacetime constant that can be inferred independently of any supplementary assumption and whose identification with light is derived from optics. According to the conjecture, the speed of light is absolute in this sense, making superluminal interactions impossible by the same reason that nothing can be less than zero. Note that the conjecture has no impact on the synchronizing clocks at different places by means of signal exchanges.

(ii) In SR, the relativity of simultaneity follows from the spacetime diffeomorphism allowing a slicing of the universe into an infinite number of local present moments depending on the velocities of inertial frames in relation to each other. The sum of these instantaneous (spacelike in Minkowski space) slices of “now” is known as the block universe, where all past and future times are equally present, and there is nothing special about the present [

11]. Thus, discarding the absolute rest via the relativity of simultaneity renders the flow of time illusory as well. There arises, however, an obvious ambiguity in saying that different presents exist at the same time. What is this “same time”? Accordingly, when we say that light, emitted by a distant star at a time

, reached us at a time

over a billion years, just now, what is this now for the star?

The picture becomes more consistent if we admit that it is not light that travels through space but rather objects (including observers and stars) moving over the lightlike background at different velocities relative to its state at absolute rest. This is reminiscent of the old argument that while uniform velocities in different inertial fames can be relative, the transition between frames, i.e., acceleration must have an absolute meaning [

12]. This means that inertial frames could be well-ordered by equivalence classes in respect to the speed of light. This lightlike (null) background at rest brings us back to Lorentz’s or, rather, to Dirac’s [

13] ether in quantum electrodynamics, about which Einstein noted that it would be more correct to emphasize only the non-existence of an ether velocity, instead of arguing for the total non-existence of the ether as such.

(iii) When combined with the principle of relativity, the constant speed of light should also be independent of the speed of the observer. Given the definition of velocity as a distance passed per unit of time, one of the implications of SR is length contraction and time dilation so that the very passage of time should be relative to an external observer. Accordingly, as an object approaches the speed of light, time dilates ad infinitum from the perspective of that observer as if the object’s velocity was moving towards absolute rest. Since the relativity of motion must be universally applicable everywhere, the lightlike or null background should appear “frozen” in time for all observers, moving at different velocities relative to it and each other.

(iv) In SR, the actual local present is a lightlike point in Minkowski space to which absolute rest and instantaneous rest converge. Taking now into account the relativity of simultaneity, one can come to the conjecture that Minkowski space as a whole can indeed be considered consisting of lightlike points. This takes the form of a null background over which spatiotemporal dynamics and causal processes unfold. Unfortunately, the concept of instantaneous rest leads to Zeno's arrow paradox (and Quantum Zeno effect of observation by decoupling a system of interest from its coherent environment in “frozen” formalism) that states that motion is impossible despite experimental evidence.

Thus, we need to resolve the problem of instantaneous rest for the actual local present. A simple answer is to suppose that the present is not a single instant, but a set of instants. In Smolin’s view, the present is thick, made of those events that are in the process of realizing themselves [

14]. But how much thick should the present be?

3. Time Continuum and Actual Present

The nature of time has been a topic of debate since ancient times. Is time real or illusory? If it is real, is it absolute or relational? If it is absolute, does time flow as the actual present or does it exist eternally? If the present is actual, what is its duration? Zeno paradoxes of motion, hinged on the concept of instantaneous rest, are, probably, the most famous examples of this discussion. A similar argument against the extended present was proposed by St. Augustine who argued: “For if it is extended, it is then divided into past and future. But the present has no extension whatever” [

15]. So, how can we resolve these issues?

3.1. Mathematical Foundations

In SR, time is presented geometrically by the temporal axis in Minkowski space, with is associated with the real line ℝ. This line is a linear continuum with corresponding topological properties. Accordingly, the actual present, presented as a point of intersection between the past and the future lightcones in Minkowski space, should be analyzed topologically not only geometrically. For simplicity, I will restrict the analysis of the continuum as a compact connected metric space to the archetypal real line ℝ which is a densely ordered set, i.e., between any two distinct elements there is another (and, hence, infinitely many others), and complete, i.e., which lacks gaps or missing points within itself.

More informally, by associating the real line with the temporal axis, , we have that any point divides the temporal continuum into an open and a closed set, where the point belongs either to , closed from above, or to , closed from below, or is an isolated point , nearest points of which cannot be known to us (i.e., be effectively fixed). In other words, at any moment of time , we are either still in the past light cone, or we have already entered the future light cone, and the actual present does not exist. Otherwise, this present moment is indeed an isolated lightlike point in Minkowski space at instantaneous rest with no duration.

Of course, it can be pointed out that the concept of instantaneous rest was successfully disproven by the inventors of infinitesimal calculus, based on the (ε, δ)-definition of limit, where velocity as the ratio of the instantaneous change in the systems evolution is formally defined can by the derivative of a differentiable function at a point . However, in the light of Cantor’s proof, discussed below, it can be said that mathematical analysis, based on the epsilon–delta definition of continuity, does not attain the “genuine” continuum, restricted here to ℝ, but deals only with its least coarse-grained (countable) cover.

Cantor showed with the help of his famous diagonal argument that the set of real numbers ℝ cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence with the infinite (discrete and countable) set of natural numbers ℕ. The diagonalization provided proof of the uncountability of ℝ, typically viewed as rigorous evidence that ℝ is “bigger” than ℕ. This led Cantor to formulate the continuum hypothesis, the assumption that , where and are their cardinalities.

Under this assumption, however, it may happen that even a unit interval or any part of its partition is “bigger” than ℕ. But is it so? In fact, what Cantor diagonalization proved was that there is no effective procedure to make ℝ a totally ordered set despite our intuition that the real line is exactly that. Note that this tells us nothing about the size (cardinality) of ℝ but only this: we cannot be certain that the continuum is totally ordered. This makes the continuum uncountable as well. Indeed, the only way to learn that an arbitrary set is countable is to put its elements in total order. But countability and total order are not equivalent. If a finite set cannot be totally ordered for some reason, it happens uncountable regardless of its size.

To bolster intuition, consider two axioms: the axiom of choice (AC) and the separation axiom (SA). The AC is defined in set-theoretical formalism which is not relevant here. Informally, it asserts that one can choose an arbitrary element from a given set and repeat this process infinitely many times. This in turn leads to Zermelo’s theorem which asserts that every set, including ℝ, can be well-ordered by merely depleting all elements of the set and putting them in total order based on the random order of selection. The theorem, however, could not be proven without implicitly relying on one more assumption, namely the notion of the actual infinity, because in reality one might never deplete the continuum ℝ to put it into total order.

Another axiom, the SA is defined in topological terms. In the context of ℝ, we are mostly interested here, the axiom states (in Hausdorff version) that any two distinct points and in ℝ can be separated if there are neighborhoods and so that . Hence, two randomly chosen points can be distinguishable if and only if there are infinitely many points between them.

The AC was criticized by mathematicians as proving the existence of objects that cannot be explicitly constructed. In context of physics, however, AC acquires a quite practical sense related to free will of observers. An experimenter can freely choose the time for setting up his experiment and making measurements, which, however, will always occur at his actual present. In this sense, free will is evidently bounded since nobody can change something in the past. In theory, we can (with the help of AC) choose two arbitrary points and on ℝ, distinguishable by their disjoint neighborhoods (according to SA) and show that either or . But we are unable to effectively point out the nearest points of on each its side in ℝ.

3.2. Physical Implications

In terms of physics, one can say that the temporal continuum (the arrow of time) is well ordered by the mathematical (

ε,

δ)-definition of continuity at a ‘macroscopic’ scale of classical observations, but this order cannot be effectively detectable in ‘microscopic’ observations, related contextually to the quantum scale. This is not of great importance in respect to the past where the temporal and causal order has been well preserved, but this becomes problematic when one deals with the actual local present, where quantum phenomena take place such as wave-particle duality, superposition, entanglement, with the dominance of the uncertainty principle, which in Heisenberg words is applicable exclusively to the present and not to the past [

16].

But why should the present have a special status, given that spacetime is isotropic and homogeneous, and there is no fundamental difference between the past and present? The anthropocentric argument that every present in the past is trivial for us, conscious observers, and only the actual present matters does not provide a physically and/or mathematically satisfactory explanation [

17]. From the perspective of physics, the only difference we can find between them is that the past is extended in time, whereas the actual present is transient. We are literally constrained to look at the present with a (quantum) microscope, whereas the past is better visible through a telescope.

This implication from the AC and SA in regard to the temporal continuum can be reformulated as follows.

The principle of indiscernibility of the nearest past and future. For any given present moment in the linear continuum of time it is impossible to detect its closets points on each side.

Note that the indiscernibility principle (IP) does not depend on the resolution of the measuring devices used in observation. An immediate consequence of the IP is that while the evolution of a classical system is described in terms of coarse-grained variables with well-defined values at any time and at any point of space, in quantum theory it is impossible to assign a definite value to a variable without observations that occur only at the actual present moment. Thus, the IP underlies the measurement problem in QM, and the uncertainty principle can be inferred from it.

3.3. Causal Order in the Actual Present

Because the notion of causality is inferred by us from observations of regularities in the world, where a cause always precedes an effect, causal order cannot be discussed meaningfully without involving temporal order. Therefore, preserving the fundamental causal order in both SR and GR, where no event can be a cause of itself, while discarding absolute time, is inconsistent. Time should be more than an “internal clock” associated with an arbitrary and relational observer.

The causal set approach to quantum gravity should start with this point. The approach was inspired by Malament theorem that the class of continuous timelike curves determines the topology of spacetime [

18]. A causal set is defined as a particularly ordered set

, where ≺ is transitive and irreflexive, thereby forbidding causal loops [

19]. The set

is the union of all causal chains where the link between two elements

and

is represented by either a timelike or null vector in Minkowski space. The theory takes the Lorentzian character of Minkowski space

and the causal structure of the set

as a starting point for the quantization of spacetime [

20]. In this view, spacetime is nothing but the causal ordering of discrete events, encapsulated in the slogan: Causal Structure + Volume Element = Lorentzian Geometry.

However, according to the IP, it is not correct to say that spacetime is fundamentally discrete, where the causal order of instantaneous and transient events is a partial order, determined by lightcone geometry [

21], but that this will be so in our observation where the nearest past and future of a particular micro-event cannot be effectively detectable. As a result, many micro-events happen glued together in every causal chain. As stated, the IP is crucial only for the actual present moment

on the arrow of time. In practice, this means that any observer, conducting a fine-tuned quantum experiment, faces what can be called the

epistemological problem of the identity of indistinguishable micro-events that are, however, ontologically different. A measurement, always made in the actual present moment, pulls a particular micro-event out of the (effectively non-orderable and uncountable) continuum of such events.

A similar view that the distinction between the past and the present can be inferred from the difference between indefinite and definite in QM was proposed by Smolin and Verde [

22]. They describe this “fundamental” difference as follows:

- (i)

if a process is indefinite, the amplitudes for the different possibilities are summed over in the path integral, before the absolute values squared are taken to give probabilities;

- (ii)

in contrast, the amplitudes for definite processes are not summed over - rather we form the probability for each definite process by directly taking the absolute value squared.

The distinction between the present and past is then regarded in terms of the transition from the indefinite (present) to the definite (past).

A more formalized approach to this distinction between the (macro)past and the (micro)present was proposed by Hardy, based on the difference between the discrete and the continuous [

23]. Hardy proposes a set of five axioms for quantum theory which have a striking property: if the fifth axiom about a continuous reversible transformation on a system between any two pure states (or even just the word “continuous”) is removed from the set, then we obtain classical probability theory, typically applicable to our ordinary observations of definite processes. Because classical probability theory, axiomatized by Kolmogorov, resembles Boolean algebra, the IP also has relevance to quantum logic. Of course, this does not mean that Nature admits two types of physical processes: definite and indefinite. Definite processes are simply coarse-grained over spacetime at a macroscopic scale, well applicable to the extended past, while indefinite processes are fine-grained at a microscopic scale when taken in respect to the transient present. The devil is not in the state of matter but in the details of observation. i.e., in measurement procedures.

Thus, the “fundamental difference” Smolin and Verde argue for is a consequence of the IP. But saying this does not imply that definite classical processes are genuinely ontological, whereas indefinite quantum processes are epistemological so that QM is indeed statistical (or even probabilistic in a Bayesian sense) and needs hidden local variables. It is true that QM does represent the state of our knowledge, but our incomplete knowledge is constrained by the state of matter itself. In other words, indefinite processes are still ontological, and QM provides the best knowledge we can obtain about the “genuine” physical continuum.

4. Extension of SR

An extended theory, SRE, will be based on four postulates. This preserves the principle of relativity unchanged, and reinterprets the second postulate about the constancy of as the conjecture discussed above. The fourth postulate about the actual present is added together with the principle of indiscernibility. This can be formulated in two forms.

Actuality Postulate. The universe exists only in the actual present (strong version).

Any measurement can only be made in the actual present moment (weak version).

The strong version is known as philosophical presentism, while the weak version refers to our everyday practice. Whenever an experimenter makes a measurement, the measurement will always occur at their actual local present, nowhere else. Clearly, the weak version follows immediately from its strong form.

Thus, SRE will be derived from four postulates:

Relativity postulate (RP).

Absolute rest postulate (ARP).

Indiscernibility postulate (IP).

Actuality postulate (AP).

On the one hand, the actual local present, represented in Minkowski space by a lightlike point and associated with a particular event

, should be at instantaneous rest as if no motion were possible in the universe despite our daily experiences. On the other hand, the IP tells us that these dynamics, represented by discrete events

, are causally uncertain around the actual present at a microscale. We are constrained to study this actual present moment topologically, not only geometrically. In other words, the lightlike point of Minkowski space should be placed within its neighborhood or halo in nonstandard analysis of surreal (hyperreal) numbers. Nonstandard analysis, invented by John Conway as the largest non-Archimedean extension of the field of reals [

24], was particularly inspired by the ideas discussed above concerning the classical (

ε,

δ)-definition of continuity. This is concerned with both infinite numbers (ordinals)

and infinitesimals

defined as elements

such that

for all positive reals

, where

is a subset of

. Accordingly, two elements

and

are said to be infinitely close in

,

, if

is infinitesimal [

25]. The halo of

is the set

Intuitively, the nearest points of

(when

is chosen by us with the help of AC) are effectively indiscernible from

and from each other. Henceforth, I prefer to use the word “halo” (not neighborhood) to emphasize the nature of the “genuine” continuum, underlying Minkowski space.

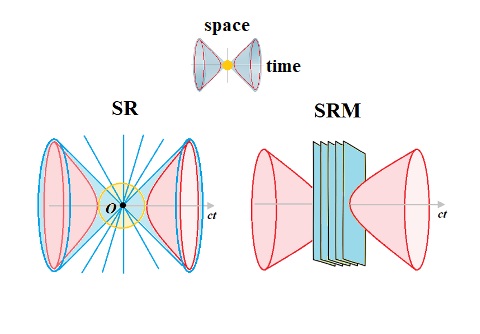

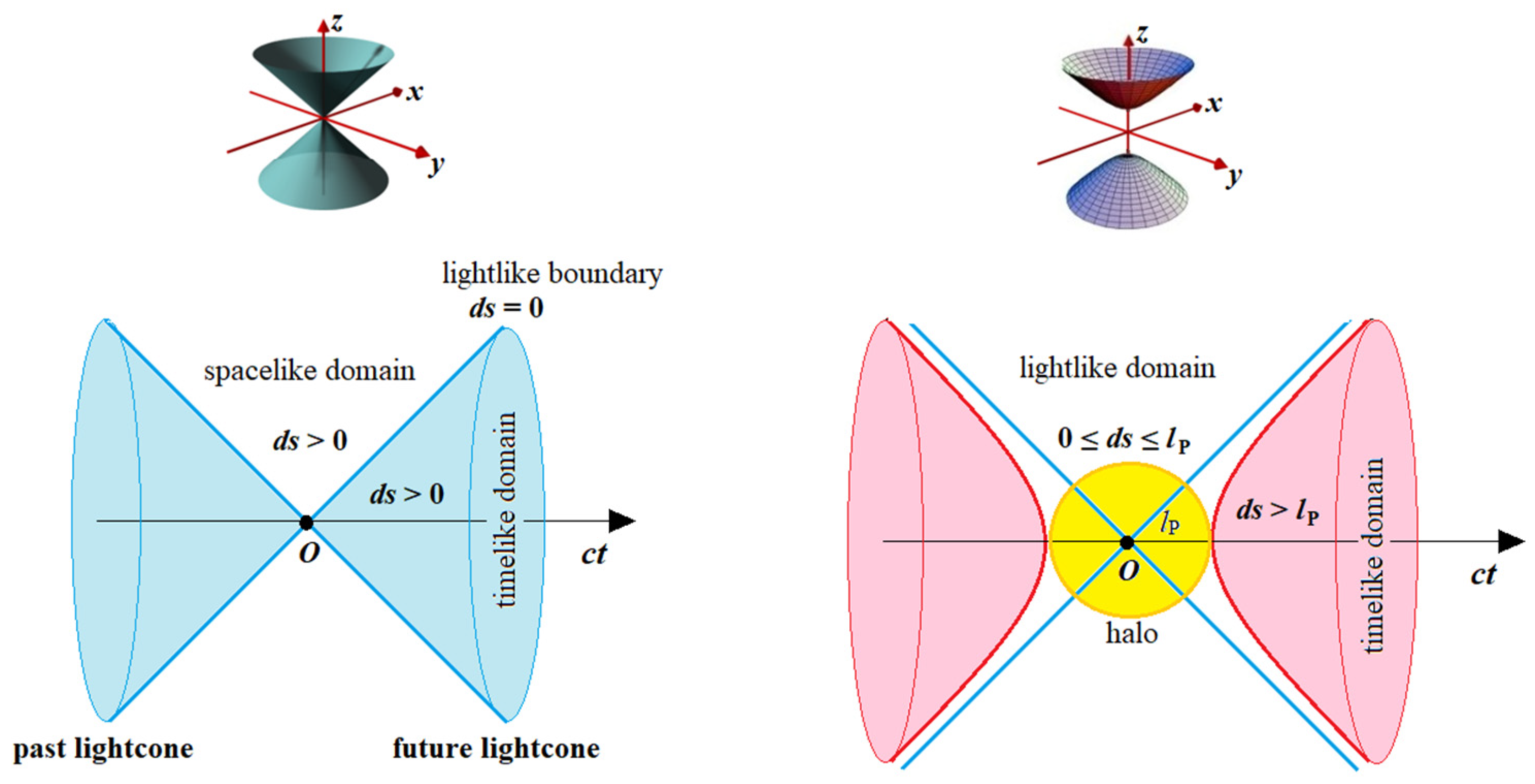

1 In SR, the spacetime interval (4-vector) is Lorentz-invariant under the Minkowski metric:

The line element is not positive-definite as a necessary feature that introduces the notion of causality in SR with respect to the constant c, related to the speed of light. The lightcone is induced by the null spacetime interval, which divides spacetime into two domains by the lightlike boundary between them, consisting of all points with :

- (i)

timelike domain with ;

- (ii)

spacelike domain with .

Only timelike and lightlike 4-vectors are causal since causal relations between spacelike-separated events would be superluminal. The past and future lightcones intersect at a point

, associated with a local present. These both contain all points of spacetime which can affect

or be affected by

via signals propagating at the speed

. A natural way to integrate the halo

around the lightlike point

of actual local present into Minkowski space is transformation of the Minkowski metric into a hyperbolic one. We start with cone equation in the Euclidian 3D space:

The only difference between the cone and the two-sheet (elliptic) hyperboloid is some nonzero constant

with dimension of length:

Geometrically, the hyperboloid is asymptotic to the cone. Yet, by changing the sign of in Eq.4, the two-sheet hyperboloid turns into the one-sheet hyperboloid known as de Sitter space we are not interested here. Intuitively, might be associated with the Planck length .

Then the hyperbolic metric in Minkowski space takes a form:

This modification entails three fundamental consequences.

First, since , the constant can now be defined not as the speed of light, inferred from optics, but rather as an inner invariant property of the halo . Given the relativistic effects at the speed of light, where time dilates ad infinitum, , while length contracts to zero, , as defined by the Lorenz factor , time and space might vanish within (at least, for massless particles), attached then to the ARP. Thus, in SRE, the absolute rest does not refer to Newtonian absolute time and space but to the null background at a vacuum state where time and space lose their physical meaning.

Second, this also spontaneously involves the fundamental constants

and

in Minkowski space that are generally outside the scope of SR. A similar approach was proposed in Doubly Special Relativity mentioned above. DSR is directly inspired by a heuristic argument from quantum gravity that, besides the speed of light, there should also be an invariant (observer-independent) scale. It assumes that at the Planck scale the world may be non-relativistic, with a structure distinct from a differentiable manifold [

5,

26], and constructed in momentum space by requiring the existence of an invariant momentum and/or energy scale [

7,

8]. This is viewed as a way to quantization of spacetime in quantum gravity. In the case of SRE, however, the Planck length is involved not from the assumption that there should be a Lorentz invariant energy scale but from a purely mathematical viewpoint as being related to the “genuine” continuum.

Third, unlike the conical metric (2), the metric (5) is positive-definite. Accordingly, instead of dividing Minkowski space into timelike and spacelike domains by the lightlike boundary with

, only timelike and extended lightlike domains are valid by eliminating the spacelike domain with the negative line element,

(

Figure 1).

To make sense of it, return to the causal set approach mentioned above [

19,

20,

21]. In Minkowski space, the future lightcone of a lightlike point

, as representing an instantaneous and transient event

in the actual local present, consists of all points that are causally accessible from

, and the past lightcone contains all points for which

is causally accessible, whereas the spacelike domain consists of the points that are causally irrelevant to

. Now, instead of discussing a causal (discrete) subset

, induced by

in Minkowski space

, consider the notion of filter in topology, namely, the neighborhood filter

in

, which is the family of sets consisting of all neighborhoods of

such that

x. does not contain the empty set and is closed under finite intersections and taking supersets. The future lightcone can be viewed as a topological sector of the filter, consisting of points with non-negative spacetime intervals.

However, in SRE, we have a filter of within the halo ℍ. Its causally accessible sector embraces both the future lightcone and spacelike domain, i.e., theoretically the whole Minkowski space, except for the dual past-oriented hyperboloid. Thus, all points inside each hyperboloid are timelike with causal 4-vectors, all points outside hyperboloids are lightlike and causally connectable, with the boundary between them that is asymptotic to the lightcone and uncertain according to the IP. Yet, by eliminating the spacelike domain from Minkowski space according to the ARP, superluminal signaling becomes impossible in principle.

Another crucial difference is this: the conical metric admits a decomposition of Minkowski space into a countable and well-ordered union of disjoint hypersurfaces so that the worldline of a particle, passing through them, is represented by a differentiable (future oriented causal) curve. In contrast, the hyperbolic metric decomposes Minkowski space into a foliation of 3D-slices where the nearest slices are non-separable within a halo. The worldline of a particle, passing through , is, thus, affected by the IP as if its points were “glued” together, making the causal order difficult to detect effectively.

Here, one can easily draw an analogy between a halo around the lightlike point of the actual local present at the Planck scale and the event horizon of a black hole, determined by the Schwarzschild radius

at the cosmological scale, associated then to each localized quantum particle in observation as a minimum black hole [

27]. By taking

, the halo can indeed be seen as the event horizon of a lightlike point in Minkowski space with a radius of Compton wavelength

The halo is not a “quantum” of spacetime. Rather, it should be interpreted as “infinitesimal confinement” in terms of topological censorship [

50], imposed by Nature on observation, i.e., on our knowledge of her physical vacuum continuum state. This censorship offers a coherent alternative to the idea that matter could be divided an infinitum. According to the AP, observers in their actual present, while moving inevitably in time, can see spacetime as a spontaneously generated quantum foam of virtual black holes that evaporate immediately by passing into the past [

28].

The Compton wavelength of a particle of mass determines its event horizon, generated by its mass-dependent halo . According to the uncertainty principle, within , the causal order cannot be effectively detectable, and the uncertainty in the position of a particle is . For a massless photon, the lightlike halo can thus extend across Minkowski space entirely, , making the photon a timeless particle in the context of relativistic time dilation.

5. Corollaries of SRE

SRE entails four (at least) corollaries.

Corollary 1. The relativity of simultaneity.

The SRE preserves the relativity of simultaneity but in a more specific form. According to the AP, only the actual present exists. There is no point in saying that two events in the past are simultaneous. Simultaneity makes sense only with respect to the actual local present we are at just now.

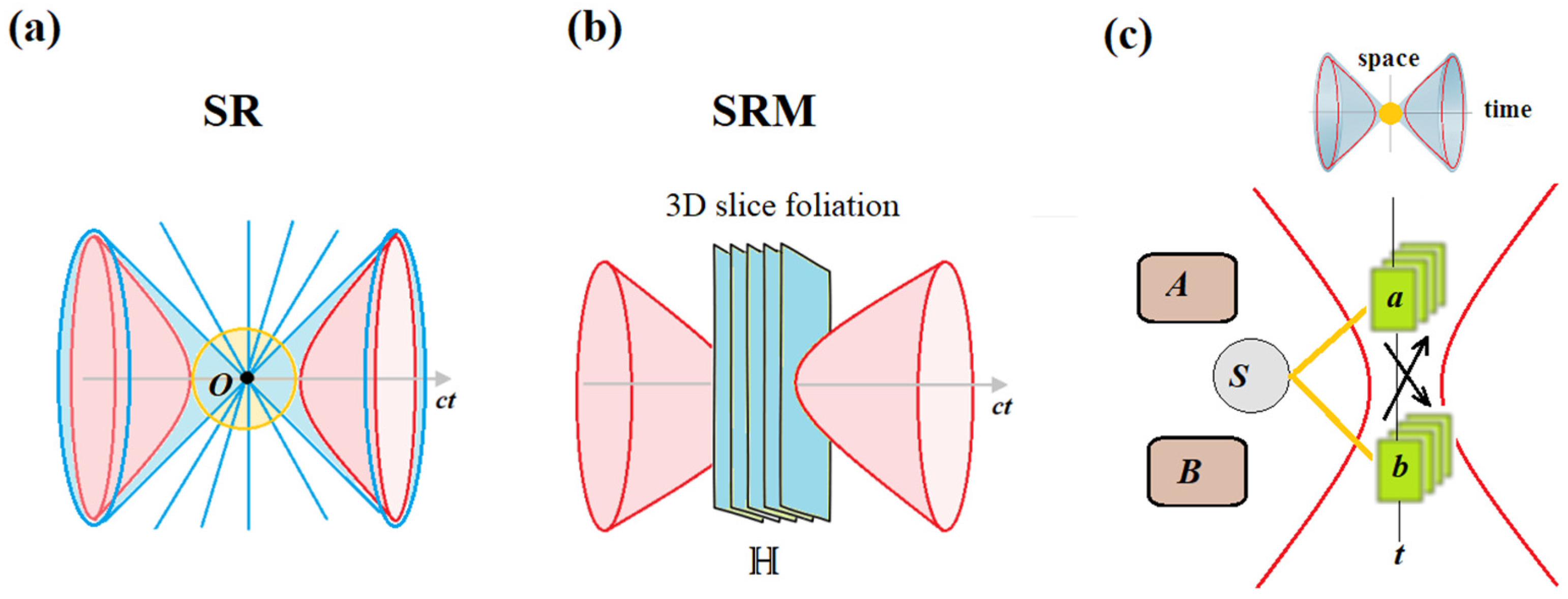

In SR, two observers in different inertial frames, commonly named Alice and Bob, will disagree on the simultaneity of two events and : while Alice detects those at the same time , the Bob can detect at a moment and at a moment , all related to different slices in the foliation of spacetime. This makes simultaneity relative in SR. Nonetheless, there still appears a privileged frame, associated with the speed of light at a lightlike point of the actual local present in Minkowski space. This point is at instantaneous rest, e.g., at a moment when Alice makes her simultaneous observation of events and . It follows then immediately from the conical metric that an infinite number of simultaneous hyperplanes can be drawn over the same point on the temporal axis of Minkowski space in SR (Fig.2a). These will all be simultaneous with .

Intuitively, we have a “snapshot” of the universe at a moment , made by Alice in her actual local present. But this snapshot is also made in the lightlike frame. Obviously, we can find Bob in this snapshot in his own actual present, no matter whether or not he does detect the events and . Likewise, we can find Alice in Bob’s snapshots at moments and no matter that Alice has detected or will detect and as simultaneous. What matters is that every time they both share the same actual present. In other words, we are all relative observers with no privileged one, but we converge to a privileged observer in our actual now, presented by the lightlike point in Minkowski space that eventually enables us to make objective science.

At this point, it may seem that SRE returns simultaneity to its absolute status in Newtonian mechanics. But then SRE extends simultaneity to a halo

over many instantaneous

slices within the lightlike domain of Minkowski space that are indiscernible and where causal order cannot be effectively detectable according to the IP. (

Figure 2b). It happens that many points from different slices can be taken as simultaneous despite our macroscopic experience. This makes the relativity of simultaneity valid again but with the consequences that are not inferable from SR.

Corollary 1 has a direct relevance to the quantum experiments on wave-particle duality such as delayed choice experiments, which inspired Wheeler to propose his Participatory Anthropic Principle, challenging scientific realism: “Observers are necessary to bring the universe into being” [

29]. SRE suggest a straightforward explanation here as that follows immediately from the AP and IP. Of course, observers do not create our classical world from nothing. The universe exists independently of observers. In their actual present, however, the universe is temporally blurred so that the state of an object is causally smeared over a halo at the quantum scale, where the uncertainty principle takes place, but once a measurement is made at a moment

, that moment becomes part of the past. More precisely, the halo within the lightlike domain “collapses” under observation (measurement) to a single point

so that this moment (and, hence, the state of the universe and all its systems) passes immediately into the classical past lightcone of Minkowski space, while observers happen in the same halo between two hyperboloids, slightly shifted along the temporal axis into the future.

Therefore, it is not entirely accurate to say, in Wheeler’s words, that “the past has no existence except as it is recorded in the present,” but rather that the actual local present does not exist until it is recorded to become the past. In dynamics, observers erase the quantum superposition within a halo every time they record the state of matter in the present, which spontaneously passes into their immediate past. Thus, the wavefunction collapse in the measurement problem can be called observer-dependent in the same sense as the axiom of choice allows us to choose a particular point in the real line, . We do not create out of nothing as if it did not exist before our intervention, we only isolate the point from the real line that exists as a whole independently of observation.

In a physical context, the free choice function

can then be represented by the Dirac delta function. The function is generally regarded as a spike of indeterminate magnitude at

,

, but having an integral equal to unity

. Accordingly, for all continuous functions

on ℝ, the delta function picks out the value of

at

, physically related to the actual local present,

The function

can be reformulated as

where .

Observers are endowed with free will, allowing them to choose time

for making measurement, but whenever they do, this moment will always appear at their actual present within

. In this context, SRE not only preserves scientific realism but also makes the flow of time objective.

2 Importantly, SRE should not be seen as an alternative to SR but rather as its counterpart. There is a complementarity in Bohr’s sense between classical SR and quantum-sensitive SRE. One can introduce the formalism of QM by ascribing the properties of a complex Hilbert space

to the halo via a map:

so that

is the state of a closed system for every choice made always in the actual present

, and the time evolution of the system is described by the unitary operator:

Since , there are infinitely many points within ℍ that are missing in . This means that the time evolution of wavefunction and causal order in spacetime are physically inaccessible for observation within the halo.

In practice, the hyperbolic metric is only valid around any actual local present but dissolves in the past where the conical metric becomes valid. Thus, the principled boundary between the classical and quantum domains of physics lies at the lightlike point of the actual local present where all observers become privileged at instantaneous rest. Complementarity here also symbolizes the scale transition from a macroscopic world to a microscopic world so that a classical observer would never agree with a quantum-oriented observer, e.g., on phenomena such as superposition, randomness, and nonlocality. As a result, the macro-scale (coarse-grained) past we see behind us is always classical, while the micro-scale (fine-grained) present we experience “just now” is inevitably quantum. In other words, SRE represents a fine-grained extension of SR.

3

Corollary 2. Bell temporal non-separability

The famous EPR-experiment was proposed by Einstein and his coauthors to disprove the uncertainty principle by suggesting “elements of reality” that should be observer-independent. They argued that both the positions and momenta of two entangled particles at a distance could be measured and mutually predicted due to conservation laws, thus, making QM incomplete. They contended that no action taken on one particle could instantaneously affect the other, since this would involve superluminal signaling, which is forbidden by SR.

Bell’s inequalities were suggested to show that the EPR-experiment would not succeed [

30]. The theorem is based on three assumptions: realism, locality, and free will, also known as (i) outcome independence or statistical completeness, (ii) parameter independence, and (iii) measurement independence. These assumptions yield the joint probabilities of distantly-performed measurements

and

, given the inputs

and

, conditioned by the hidden local variables

:

Realism here is seen as a requirement that physical systems possess ontologically definite properties prior to and independent of measurements, while locality is given by a spacelike domain between a pair of entangled particles being measured. Interpretations may vary among researchers, but the underlying statistical probabilities remain consistent. The significance of Bell theorem is in demonstrating that neither Nature nor QM obey all three assumptions above. The violation of Bell inequalities is usually regarded as a failure of locality, or of realism, or of determinism [

31,

32]. A prevailing opinion among physicists emphasizes the fundamental role of nonlocality in QM but see [

33,

34].

The SRE immediately dismisses superluminal signaling by removing the spacelike domain from Minkowski space. On the other hand, the assertion that no causal relations are possible between spacelike separated events is illegitimate in the language of SRE, involving ℍ in measurement. SRE does not prohibit the existence of hidden variables , but argues that these variables would remain hidden within the halo forever due to topological censorship, which imposes a natural limit on the spatiotemporal resolution of observations.

Instead of nonlocality, non-separability takes place between entangled particles. Separability here refers to the outcome independence in the right-hand side of Eq.10 and means that all events, associated to the union of some set of disjoint spatial regions, are combinations of events associated to each region taken separately [

35]. However, we encounter the problem of the identity of indistinguishable micro-events when consider the spatial regions in time through a foliation of Minkowski space by slices Σ. According to the IP, micro-causality cannot be a verifiable concept since temporal order cannot be effectively detected at the microscale. In other words, our notions of before and after become blurred not due to the relativity of simultaneity in SR, where observers in different inertial frames can disagree on the order of events though causal order is fundamentally preserved, but rather due to the IP at the quantum scale. The entangled particles happen non-separable in the null background (Fig.2b).

Although the indistinguishability of identical particles is said to be a characterizing feature of quantum systems that has no counterpart in the classical realm [

36], the question about the quantum-classical border is still hotly discussed [

37,

38]. Nothing in SRE seems to prevent us from assuming that Bell non-separability might also holds for classical objects, given the elusive difference between Kolmogorov’s axiomatization of classical probability and Hardy’s axioms for quantum theory [

23]. In general, wave-particle duality is an effect of topological censorship imposed upon observation rather than an inherent property of matter at the quantum scale. The blurring, however, might be negligibly small for classical bodies, given a huge difference between a halo and their size, or this might be averaged by mutual blurring of the particles a body consists of.

Corollary 3. Time vanishes at the cosmological horizon of the universe.

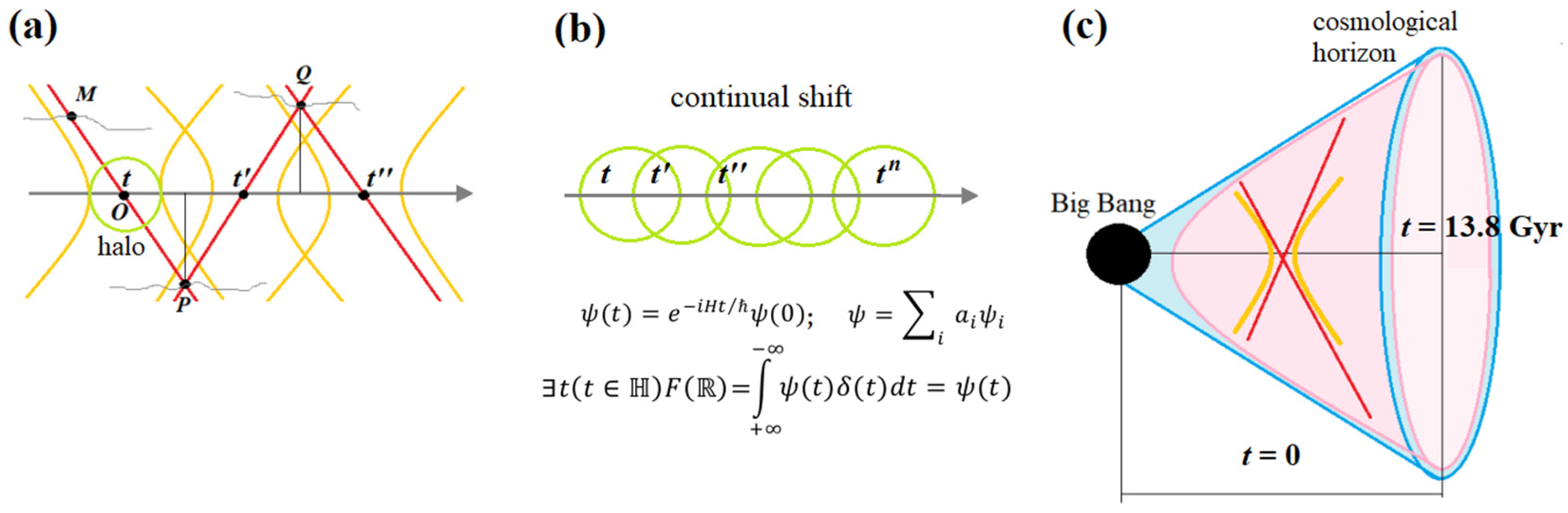

According to Corollary 1, many points in the lightlike domain around a point

in Minkowski space can be connected by instantaneous hyperplanes. Meanwhile, the worldline of a particle, associated with

, evolves through a continual shifting of its halo along the temporal axis. Now consider three lightlike domains around

at freely-chosen moments

,

, and

such that

. They can be connected by simultaneous hyperplanes with the worldlines of three other independent particles at points

,

, and

. This makes the three different moments of

on temporal axis simultaneous as if

at the null background (

Figure 3a).

The result is reminiscent of both the Zeno paradox, where motion is impossible, and the block universe picture, where past, present, and future co-exist equally. However, SRE proposes another explanation. We arrive at a situation opposite to that in Corollary 1 when observers disagree on the simultaneity of events

and

. In this case, observers might instead agree that three different positions of

are simultaneous. SR says (though it is problematic since the positions of

are causally connected): it does not matter whether observers agree or disagree because all observers are relational to each other. SRE responds: yes, all observers are relational, except for a privileged one at instantaneous rest in the lightlike point of the actual local present, attached to the null background (Lorentz-Dirac’s ether) at absolute rest (

Figure 3b).

In conclusion, the passage of time apparently persists within the universe in accordance with our experience that macro-events are temporally and causally separable, but time and causality vanish at the cosmological horizon of the universe, where all events in the past and future are simultaneous (

Figure 3c).

4

Corollary 4. The universe is closed from the inside.

According to Corollary 3, it is in principle impossible for any hypothetical observer abandon the universe or even to attain its cosmological horizon because their proper time would dilate ad infinitum there. This time dilation should not be relative as it is in SR but absolute in SRE. On the other hand, this effect would be indiscernible from gravitational time dilation. In other words, such a hypothetical observer would move toward absolute rest (at the speed of light) as if the universe was the interior of a black hole, with the cosmological (event) horizon, excreting a negative pressure on it and/or possessing its own gravity responsible for the observable redshift in Hubble law taken as evidence of the accelerated expansion of the universe.

The hypothesis of the universe inside a black hole is not new [

39,

40]. This was motivated by the mathematical similarity between a closed, homogeneous, and isotropic universe, described by the Friedmann–Lemaitre–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) metric, and the Schwarzschild metric, yielding a spherically symmetric vacuum solution of the Einstein field equations. The black hole universe (BHU) models are typically hinged on the idea of comparing the Hubble radius of the observable universe with its Schwarzschild radius [

41,

42,

43,

44]. Equipping

with Hubble time gives a temporal coordinate a determined direction and duration, and make the universe homogenous but anisotropic [

45,

46,

47]. For example, Gaztanaga [

48] proposes the BHU model with the radius

such that

, where

is a Hubble radius, and where a Schwarzschild radius

exerts negative pressure as an effective

term, with

. He argues that the BHU solution has the same observed background as the ΛCDM universe but does not require the cosmological constant or dark energy to explain cosmic acceleration.

SRE is sympathetic to BHU models, but saying this is not the whole story. The reference to the cosmological horizon with negative pressure implies that the passage of time is also impossible in the null background, permeating space as the “genuine” continuum at the vacuum state of zero-point energy, viewed then in the context of dark energy and the cosmological constant . In the context of big bang cosmology, it makes no sense to say that there exists empty space, occupied by matter, which itself expands into another outer empty space that, however, does not exist. The notion of expansion can be applicable only to something that has physical properties that differ it from emptiness having no properties. In SRE, space takes a form of vacuum state at the Planck scale which, according to the IP, is resistant (impervious) to observation. Its energy is thought to be the main candidate responsible for the expansion of the universe.

6. Concluding remarks

As stated in Introduction, there are three distinctive strategies in quantum gravity to the problem of time, which I would like to reformulate here in a more general manner as (i) time before matter, (ii) time after matter, and (iii) time is nothing. So, what is time ultimately?

SRE disagrees with assumption (iii), advocated by proponents of the block universe that the arrow of time is a cognitive artifact of observers, engaged in predictive processing by updating their Bayesian priors. Rovelli points out that the second law of thermodynamics is the only fundamental law in physics that respects time-irreversible processes, and argues that entropy growth is a perspectival and spatially bounded phenomenon, resulting from a coarse-graining, imposed upon matter by observers which are unable to detect all the microscopic details of the world at the quantum scale [

17]. He concludes: “Time asymmetry, and therefore ‘time flow’, might be a feature of a subsystem to which we belong, features needed for information-gathering creatures like us to exist, not a feature of the universe at large.”

SRE is even more radical about the microscopic details of the world by introducing topological censorship on observations. Nonetheless, SRE rejects the conclusion, drawn from it. Obviously, there are no information-gathering creatures at the quantum scale; they all emerge at larger scales. Therefore, it can be said that life is a macroscopic perspectival phenomenon, emerging from coarse-grained matter. It should then follow that not only is the flow of time experienced by observers illusory, but the existence of these (conscious) observers could be illusory as well. Do we objectively exist, not only by our subjective self-evidence?

5 In contrast, SRE implies that although time can indeed vanish at the cosmological horizon of the universe, its passage persists within it. For the existence of internal observers, the universe must necessarily be temporally evolving. Accordingly, scientific realism, i.e., the postulate that the universe we are a real part of exists independently of our observation, and the arrow of time we experience as a real phenomenon, become interdependent in the sense that if a hypothetical observer, unlike us and non-interacting with the universe, were able to look at it “from the outside”, they would not see a block universe, but rather that there was no universe at all from the outside.

SRE can be more consistent with version (i). Assuming that time precedes matter, how reasonable is it to suppose that what we call time in everyday language and what astronomers identify as dark energy are the same thing? In this case, the statement inferred from observations that the universe expands with time would turn out to be a hidden tautology in the sense that time is just what makes the universe expand. Space itself could be “made” of time, merged together in a halo in the form of quantum foam that evaporates immediately by passing into the past, and is responsible for the accelerating expansion of the universe. This is a modification of general relativity in which the cosmological constant is considered as a dynamical variable, with ‘cosmological’ time conjugate to . This could also explain why time is zero at the cosmological horizon.