Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

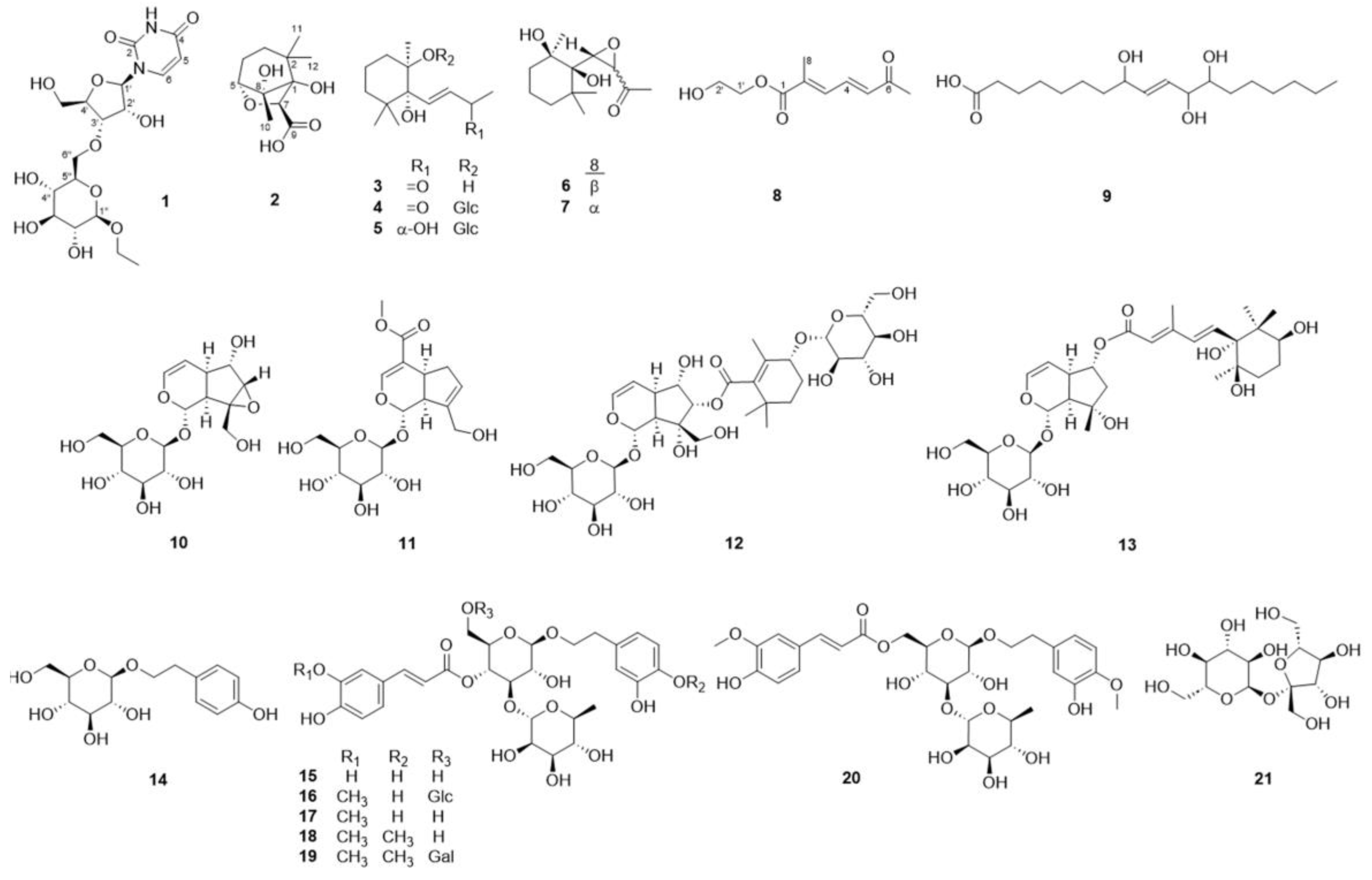

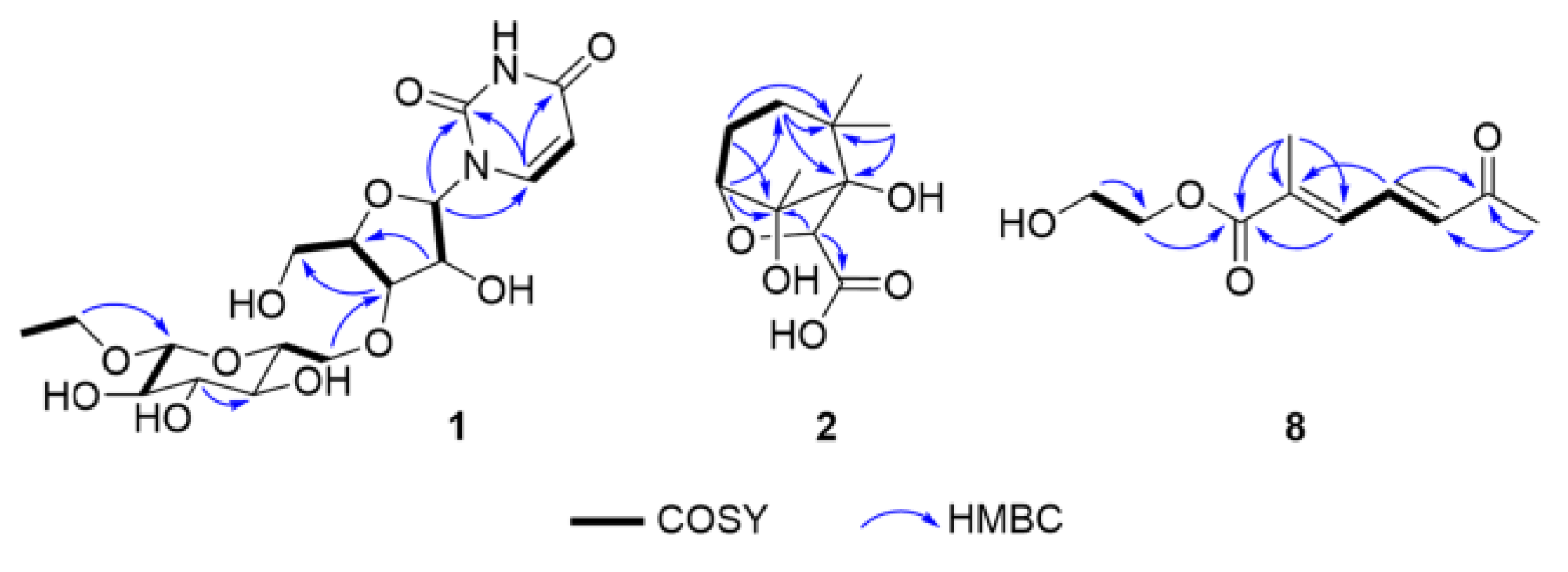

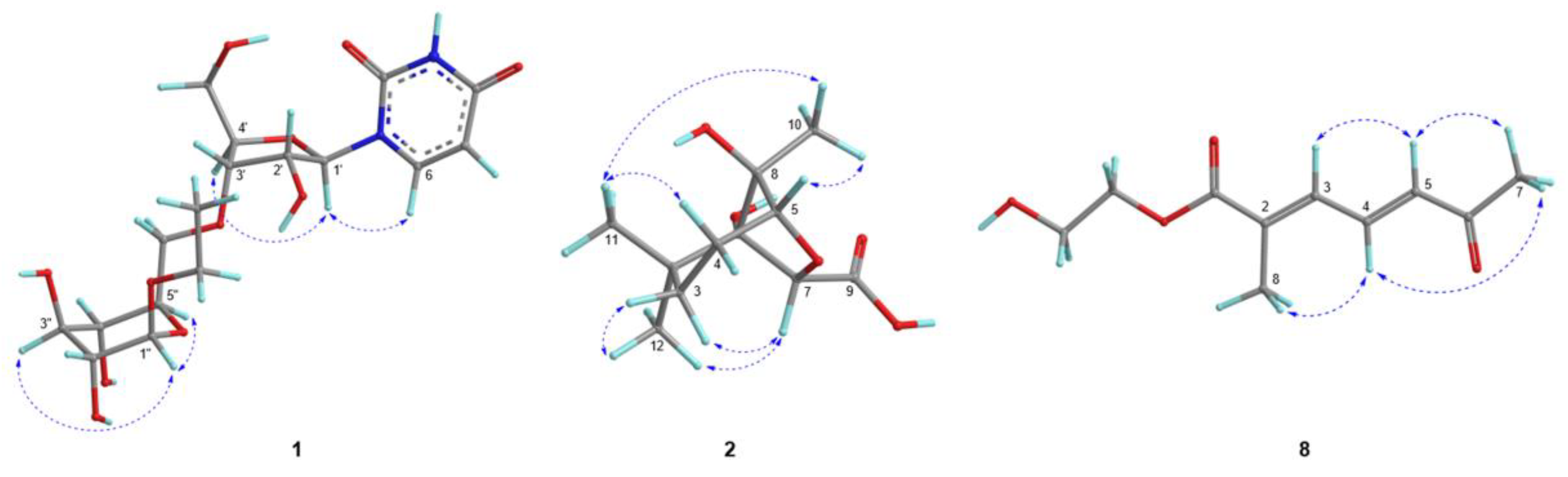

2.1. Structure Elucidation

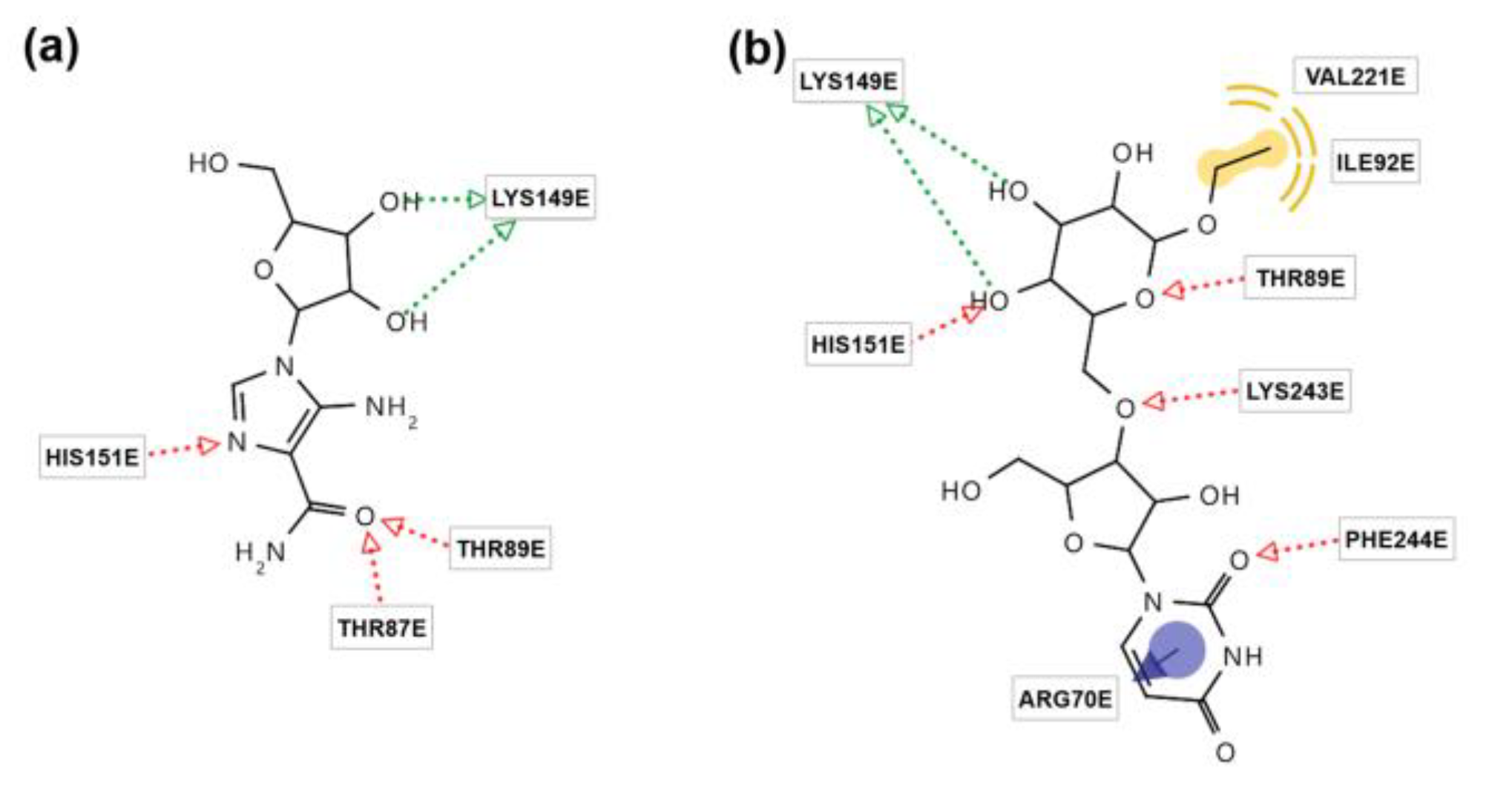

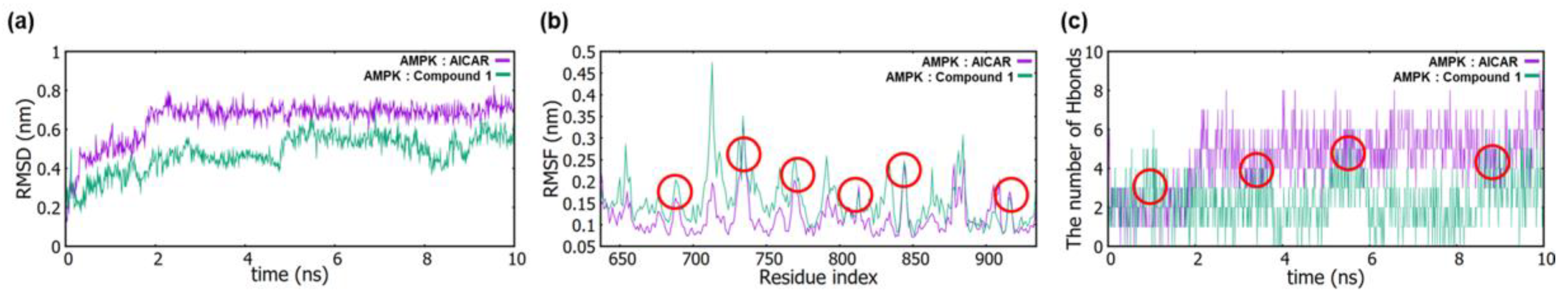

2.2. In Silico Simulation

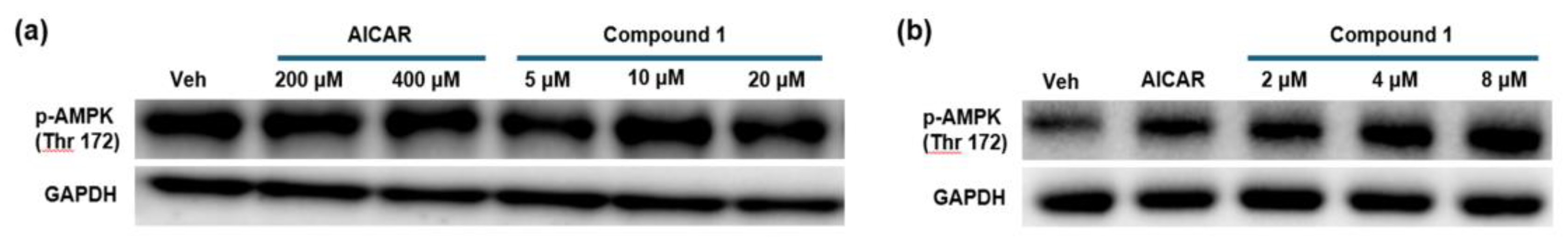

2.3. In Vitro Assay

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Experimental Procedures

4.2. Plant Material

4.3. Extraction and Isolation

4.4. In Silico Simulation

4.4.1. Molecular Docking

4.4.2. Molecular Dynamics

4.4.3. ADMET Prediction

4.5. In Vitro Assay

4.5.1. Cell Treatment Experiments

4.5.2. Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction

4.5.3. Reagents

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.-J.; Jiang, C.; Xu, N.; Li, J.-X.; Meng, F.-Y.; Zhai, H.-Q. Sorting and identification of Rehmannia glutinosa germplasm resources based on EST-SSR, scanning electron microscopy micromorphology, and quantitative taxonomy. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 123, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Dong, C. Rehmannia glutinosa polysaccharides: A review on structure-activity relationship and biological activity. Med. Chem. Res. 2024, 33, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-X.; Li, M.-X.; Jia, Z.-P. Rehmannia glutinosa: Review of botany, chemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 117, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, T.Y.C.; Ong, K.L.; Cheung, B.M.Y. Review of the effects of the traditional Chinese medicine Rehmannia Six Formula on diabetes mellitus and its complications. J. Diabetes 2011, 3, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Bose, S.; Kim, Y.-M.; Chin, Y.-W.; Kim, B.-S.; Wang, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, H. Rehmannia glutinosa reduced waist circumferences of Korean obese women possibly through modulation of gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 2684–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Yook, T.-H.; Kim, J.-U. Rehmanniae Radix, an effective treatment for patients with various inflammatory and metabolic diseases: Results from a review of Korean publications. J. Pharmacopunct. 2017, 20, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, N.-X.; Mo, W.; Wan, R.; Ma, C.-G.; Li, X.; Gu, Y.-L.; Yang, X.-Y.; Tang, Q.-Q.; Song, H.-Y. Rehmannia inhibits adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 371, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-Y.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, D.H.; Kang, B.-J.; Choi, S.; Park, Y.S. Oral administration of Rehmannia glutinosa extract for obesity treatment via adiposity and fatty acid binding protein expression in obese rats. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2017, 9, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yang, G.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Ha, J. AMPK activators: Mechanisms of action and physiological activities. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e224–e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, C.D.; Ngan, T.B.; Huong, D.T.M.; Quyen, V.T.; Murphy, B.; Van Minh, C.; Van Cuong, P. Secondary metabolites from Micromonospora sp.(G044). J.Sci. Technol. 2017, 55, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, D.; Sikorski, A.; Grzywacz, D.; Nowacki, A.; Liberek, B. Characteristic 1H NMR spectra of β-D-ribofuranosides and ribonucleosides: Factors driving furanose ring conformations. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 29223–29239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saimaru, H.; Orihara, Y. Biosynthesis of acteoside in cultured cells of Olea europaea. J. Nat. Med. 2010, 64, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyahara, T.; Nakatsuji, H.; Wada, T. Circular dichroism spectra of uridine derivatives: ChiraSac study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 2931–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenkert, E.; Guo, M.; Lavilla, R.; Porter, B.; Ramachandran, K.; Sheu, J.H. Polyene synthesis. Ready construction of retinol-carotene fragments,(±)-6(E)-LTB3 leukotrienes, and corticrocin. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 6203–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T.; Taguchi, H.; Sasaki, H.; Yosioka, I. Studies on the constituents of Aeginetia indica L. var. gracilis Nakai. Structures of three glycosides isolated from the whole plant. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1979, 27, 2807–2814. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Fukuda, Y.; Taniyama, T.; Kitagawa, I. Chemical studies on crude drug processing IX. On the constituents of Rehmanniae Radix (3) Absolute stereostructures of rehmaionosides A, B, and C, and rehmapicroside, biologically active ionone glucosides and a monoterpene glucoside isolated from Chinese Rehmanniae Radix. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Cao, Y.-G.; Ren, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.-L.; Fan, X.-L.; He, C.; Ma, X.-Y.; Zheng, X.-K.; Feng, W.-S. Ionones and lignans from the fresh roots of Rehmannia glutinosa. Phytochemistry 2022, 203, 113423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.; Lao, A.; Wang, Y.; Chin, C.-K.; Rosen, R.T.; Ho, C.-T. Antifungal constituents from the seeds of Allium fistulosum L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6318–6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, T.T.P.; Bui, T.Q.; Quy, P.T.; Bao, N.C.; Van Loc, T.; Van Chien, T.; Chi, N.L.; Van Tuan, N.; Van Sung, T.; Nhung, N.T.A. Isolation, semi-synthesis, docking-based prediction, and bioassay-based activity of Dolichandrone spathacea iridoids: New catalpol derivatives as glucosidase inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 11959–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Ueno, M.; Masuoka, C.; Ikeda, T.; Nohara, T. Iridoid glucosides from the fruit of Genipa americana. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53, 1342–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.-S.; Li, M.; Zheng, X.-K.; Zhang, N.; Song, K.; Wang, J.-C.; Kuang, H.-X. Two new ionone glycosides from the roots of Rehmannia glutinosa Libosch. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, H.; Nishimura, H.; Morota, T.; Katsuhara, T.; Chin, M.; Mitsuhashi, H. Norcarotenoid glycosides of Rehmannia glutinosa var. purpurea. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 1639–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Yean, M.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kang, S.-S. Phytochemical studies on Rehmanniae Radix. Korean J. Pharmacogn. 2011, 42, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, H.; Nishimura, H.; Chin, M.; Mitsuhashi, H. Hydroxycinnamic acid esters of phenethylalcohol glycosides from Rehmannia glutinosa var. purpurea. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyase, T.; Koizumi, A.; Ueno, A.; Noro, T.; Kuroyanagi, M.; Fukushima, S.; Akiyama, Y.; Takemoto, T. Studies on the acyl glycosides from Leucoseptrum japonicum (Miq.) Kitamura et Murata. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1982, 30, 2732–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Taguchi, H.; Endo, T.; Yosioka, I.; Higashiyama, K.; Otomasu, H. The glycosides of Martynia louisiana Mill. A new phenylpropanoid glycoside, martynoside. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1978, 26, 2111–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calis, I.; Lahloub, M.F.; Rogenmoser, E.; Sticher, O. Isomartynoside, a phenylpropanoid glycoside from Galeopsis pubescens. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 2313–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, N.; Yusup, S.; Yiin, C.; Ratri, P.; Halim, A.; Razak, N. Prediction of solvation properties of low transition temperature mixtures (LTTMs) using COSMO-RS and NMR approach. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1195, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, K.; Grauffel, C.; Lim, C. How molecular size impacts RMSD applications in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremanian, S.; Rashidi, M.M.; Raeisi, K.; Toghraie, D. Molecular dynamics simulation approach for discovering potential inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2: A structural review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 354, 118901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattamisra, S.K.; Yap, K.H.; Rao, V.; Choudhury, H. Multiple biological effects of an iridoid glucoside, catalpol, and its underlying molecular mechanisms. Biomolecules 2019, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Hu, Q.; Xiao, X.; Ou, L.; Chen, Y.; Luo, S.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, X. The emerging possibility of the use of geniposide in the treatment of cerebral diseases: A review. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Kasim, V. Therapeutic potential and molecular mechanisms of salidroside in ischemic diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 974775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Ren, Q.; Wu, L. The pharmacokinetic property and pharmacological activity of acteoside: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Cheng, X.; Li, X.F.; Kong, Y.; Jiang, S.; Dong, C.; Wang, G. Design, microwave synthesis, and molecular docking studies of catalpol crotonates as potential neuroprotective agent of diabetic encephalopathy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhai, B.; Wang, M.; Fan, Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Zou, J.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Guo, D. The influence of rhein on the absorption of rehmaionoside D: In vivo, in situ, in vitro, and in silico studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 282, 114650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Meng, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Liu, K.; Sun, H. Catalpol ameliorates hepatic insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes through acting on AMPK/NOX4/PI3K/AKT pathway. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 130, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, H.-J.; Zhang, J.-H.; Liu, X. The active ingredient catalpol in Rehmannia glutinosa reduces blood glucose in diabetic rats via the AMPK pathway. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Autodock Vina | Autodock4 | Dock6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AICAR * | -6.4 | -6.9 | -37.3 |

| 1 | -6 | -8.2 | -58.4 |

| 2 | -4.7 | -4.8 | -25.5 |

| 3 | -4.8 | -5.2 | -27.6 |

| 4 | -4.6 | -6.8 | -43.7 |

| 5 | -5.5 | -7.9 | -44.6 |

| 6 | -5.1 | -6.2 | -29.0 |

| 7 | -4.4 | -6.6 | -26.2 |

| 8 | -5.3 | -5.5 | -29.8 |

| 9 | -6.5 | -8.4 | -44.0 |

| 10 | -6.8 | -9.3 | -48.3 |

| 11 | -6.3 | -9.7 | -50.1 |

| 12 | -5.9 | -1.4 | -57.8 |

| 13 | -4.1 | -10.5 | -53.7 |

| 14 | -6.9 | -7.9 | -39.4 |

| 15 | -5.5 | -6.6 | -66.8 |

| 16 | -4.6 | 3.6 | -71.0 |

| 17 | -5.3 | -8.7 | -64.4 |

| 18 | -4.7 | -2.1 | -65.2 |

| 19 | -2.6 | 13.2 | -68.8 |

| 20 | -6.2 | -10.0 | -67.9 |

| 21 | -6.1 | -11.5 | -38.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).