1. Introduction

To support Penrose’s conformal cyclic cosmology (CCC, Penrose 2010, 2020), Gurzadyan and Penrose presented a map of temperature low-variance circles (LVCs) based on the cosmic microwave background (CMB) data (Gurzadyan & Penrose 2013, 2016; Penrose 2020). From the WMAP data, they found a large, higher-temperature LVC region X concentrated around

, and a small, lower-temperature region Y around

(Gurzadyan & Penrose 2013). When updating their search on the Planck data, they found two other large LVC regions. Since they did not name them, we assign names accordingly (

Figure 1): the lower-temperature region Z concentrated at

, and moderate-temperature region W at

(Gurzadyan & Penrose 2016; Penrose 2020).

The LVCs have been interpreted to arise from previous-aeon supermassive black-hole encounters, but CCC does not predict the location of the LVCs (Gurzadyan & Penrose 2013, 2016; Penrose 2020). In this work, we postulate a new crossover between aeons, with which the anisotropic distribution of the LVC regions and many other astronomical observations can be explained.

2. Postulated Mechanism

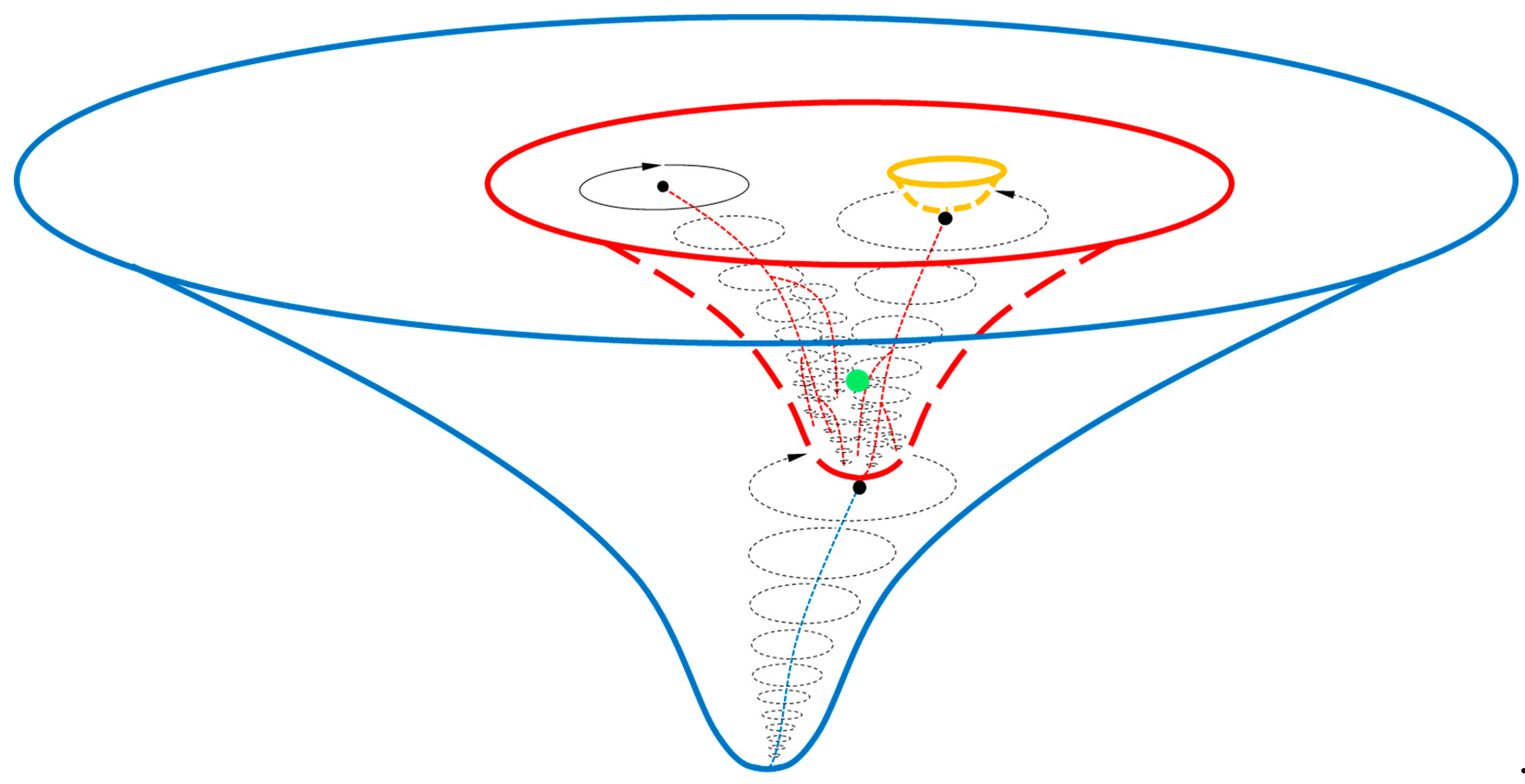

In CCC, the crossover between aeons is future null infinity (Penrose 2010, 2020). This work, instead, assumes that the crossover is the collapse of the densest object (DO), an idea similar to those suspected by former researchers, such as King (1974), Smolin (1999), and Penrose (2010) (see Appendix C). The DO would be incubated in the previous aeon: all the falling objects would be in a process of being immobilized as the densest matter, making the DO constantly grow. Once its mass exceeded a limit, the DO would collapse (see Appendices C and D for detailed analysis). Because it had already been the most dense, the only possible product of the collapse would be an infinitesimal pure energy point, i.e. the Big Bang singularity, from which this Universe was created. The DO or Big Bang singularity would be the Center of the Universe.

The densest objects that can be directly observed are neutron stars. For a spinning neutron star, there is an equatorial plane, perpendicular to its axis of spin. Objects fall towards the spinning star in spirals. The star emits twin emission beams (along its magnetic axis) symmetric about the star. If the emission beams misalign the axis of spin, then it is a pulsar. We further assume that the surroundings of the DO were analogous to those of a pulsar

4 (

Figure S1).

Right after the collapse, the powerful isotropic (Zel’dovich 1974; Penrose 1979) Big Bang expansion wave VU from the Big Bang singularity would collide with highly anisotropic (Belinskii, Khalatnikov & Lifshitz 1970; King 1974; Zel’dovich 1974) surroundings of the DO (see Appendix C). Because the emission beams Vb of the DO had the same direction as VU, compared to the curved spacetime (including dark matter) surrounding the DO, less collisions would occur, leading to twin lower-temperature trajectories symmetric about the Center. If the Center is within our observable universe, the trajectories intersecting with the surface of last scattering (SLS) would result in a pair of cold spots in the CMB sky. Simultaneously, since the falling spiral flows Vs of the DO had obtuse angles with VU, their collisions would lead to higher-temperature spirals. The spirals intersecting with the SLS would lead to hot regions.

All the collisions, including those between Vb and VU, would result in overdense clumps or debris in the primordial plasma. These clumps, comprised of dark matter, photons, and baryonic particles, as local centers, would produce outward pressure. The outward pressure and inward gravity would create oscillations or spherical waves. By enhancing local mass and heat transfer, the oscillations, like smoothers, would lower temperature variance, leaving behind LVCs. Therefore, the LVCs would be arisen completely in this aeon (different from CCC, Gurzadyan & Penrose 2013, 2016; Penrose 2020); the generation process would be very similar to baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO). As it was a dynamic process, the window to observe the LVC regions would be narrow: if formed too early, then LVCs would have dissipated; if too late, then LVCs would not have formed by the time of photon decoupling.

3. Center of the Universe

Since the ancient collision signals from the baby Universe have become vague: large in scale, small and noisy in intensity, in this work we focus on large-scale signals. As region Z is the only large region with lower temperatures, Vb cannot be determined solely by the LVC signals. We therefore check the cold spots with maximum temperature depressions. Bennett et al. (2001) were the first to find two cold spots in the CMB: Cold Spot I and Cold Spot II. By studying large-scale extrema, the Planck Collaboration (Akrami et al. 2020) confirmed both spots: (the maximum depression at ) at Peak 1 and at Peak 5 (another minimum, Peak 2, is not a typical cold spot, with merely -25 μK depression at , but with larger depressions off-center: , Figure 30 in Akrami et al. 2020). We label the cold spot at as the north cold spot (NC), corresponding to Cold Spot I and Peak 1, and the one at as the south cold spot (SC), corresponding to Cold Spot II and Peak 5.

To evaluate the symmetry of the cold spots about the Center, we define a synchronous ratio:

, where

R is the distance to the Center. If the cold spots are distributed at equal distances about the Center (

), by linking NC and SC with a line (line NC-SC), its intersection with the

Vs plane would be the location of the Center (

Figure S1).

Region X has higher temperatures, and region W has moderate temperatures (more obvious in Figure 31 in Penrose’s Nobel Lecture, Penrose 2020), both corresponding to Vs. For region X, although part of it is within the excluded galactic disk , it is obvious that the center is at its central void: (Gurzadyan & Penrose 2016; Penrose 2020). The center of region W: is obtained by taking an average of the xyz-coordinates of its LVC points from figures in Gurzadyan & Penrose (2016) and Penrose (2020).

Line XW almost intersects line NC-SC (the shortest distance between the lines is only 0.07

), so the closest point on line NC-SC can be approximated to be the Center at

and a distance

away, where

is the radius of the SLS: at photon decoupling,

; at present,

(Gott III et al. 2005). More accurately, the

Vs plane can be determined by adding a region with maximum temperature elevation: the Planck Collaboration’s Peak 3 (

, Akrami et al. 2020) concentrated at

(from figures in Marcos-Caballero 2017). The obtained

Vs plane (

Figure 2) would be:

Therefore, the intersection (

Figure 2) of line NC-SC and the

Vs plane, or the Center, would be at

and at a distance

(currently 9.3 Gpc or 30 billion light years away).

It is vital to note that region X has a small cold part near

(

Figure 1 and

Figure 3), facing the cold end of region W (Gurzadyan & Penrose 2016; Penrose 2020). These lower-temperature (rotating away from us) signals, versus the higher-temperature (rotating towards us) signals on the opposite half of the

Vs disk (more details below), indicate that the DO and consequently the baby Universe must spin. If we look from where we are, i.e. the Local Supercluster (LS), to the Center, the Universe would spin clockwise (note that this is a way to describe the direction of spin only, see

Section 6). The axis of spin would be:

The coordinates of the Center and the direction of spin obtained in this work are virtually the same as those purely from the temperature anisotropy of the CMB (Bao & Bao 2021).

4. Support for the Postulated Mechanism

For convenience, we define a

Universal Coordinate System: the Center is chosen as the origin, the

Vs plane as the Universal equatorial plane, the LS at zero degrees longitude, the direction of spin as the direction of longitude increase, and the radius of the SLS as the unit length. For example, the angle between the equatorial plane and the line through the LS and the Center is ca.

, so our Universal longitude, latitude, and radius:

(

Figure 4).

The synchronous ratio for the calculation:

, indicating that the cold spots happened to locate roughly symmetrically about the Center (

Figure 2). However, because it is not absolutely symmetrical:

, it is required to consider another important factor, the speed of spin. As shown in the Mollweide projection (

Figure 4.1 in Marcos-Caballero 2017), the cold spots (Peaks 1 and 5) are ellipses (see Appendix A for detailed analysis), indicating that, compared to the emission speed of the beams (

), the DO spun at a small speed (otherwise long arcs or even loops would have resulted). This property ensures that the small deviation from the symmetry:

is insignificant for the calculation of the coordinates of the Center; the Center is at the intersection between line NC-SC and the

Vs plane. The larger temperature depression of SC than NC (Akrami et al. 2020) also indicates that the obtained Center is reasonable, though the depression is often explained using the Integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect (e.g. Kovács et al. 2021). As it was closer to the Center, the

Vb beam at SC had a higher mass-energy density and outgoing speed, and consequently a larger depression (interestingly,

).

Whereas one third of the Universal equator is within the excluded region, region X concentrated at

and region W at

on the visible equator (

Figure 1) are on the opposite sides of the Center (

Figure 2). Incredibly, the hot part (rotating towards us) of region X (

Figure 3a) and the cold part (rotating away from us,

Figure 3b) are clearly divided by the plane:

. This alignment among the dividing plane, the axis of spin, and the LS (the observer) directly proves our mechanism (

Figure 3). It is remarkable to note that region Z concentrated at

has the same Universal latitude

as does NC at

, and that the main body of region Z has lower-temperature LVCs (

Figure 5). Our mechanism thus has another crucial piece of evidence: region Z would be generated by the northern

Vb.

Considering that the Universe is generally believed to have no center, we will provide more independent support. First, we will show why our mechanism is not against the Second Law of thermodynamics when we compare our mechanism with the CCC in the next section. Second, we will further reveal why the Universe created by our mechanism is nearly isotropic and homogeneous, just like what we are familiar with (

Section 6). Third, all the other details of Gurzadyan and Penrose’s LVC map (Gurzadyan & Penrose 2013, 2016; Penrose 2020) and the Planck Collaboration’s large-scale extrema (Marcos-Caballero 2017; Akrami et al. 2020) will be interpreted by our mechanism (Appendix A). Fourth, various astronomical observations support our mechanism. Among them, many researchers have observed that the Universe does have small anisotropies (e.g. Hudson et al. 1999; Kashlinsky et al. 2009; Feldman et al. 2010; Turnbull et al. 2012; King et al. 2012; Mariano & Perivolaropoulos 2012; Chang & Lin 2015; Migkas et al. 2021; Abdalla et al. 2022; Perivolaropoulos & Skara 2022; Aluri et al. 2023). The observed anisotropic direction (Table S1) does point towards the axis of spin (equation 2, Figures 4 and S3), as our mechanism predicted. The transition from decelerated to accelerated expansion (Riess et al. 1998; Perlmutter et al. 1999) of the Universe occurred at the disintegration of its

cradle (a previous-aeon black hole) about 4.1 billion years ago. The Hubble tension (Aghanim et al. 2020; Riess et al. 2022) may be caused by the invisible spinning of the baby Universe. The unexpected first galaxies observed by the JWST (Witze 2022; Clery 2023; Labbé et al. 2023; Boylan-Kolchin 2023) may originate from overdense collision clumps as

primordial nucleation centers, thus they grew much faster than predicted by structure formation theories. More evidence from astronomical observations is given in Appendix B. Fifth, by further providing what the DO before the collapse and the counterpart created after the collapse may be, our mechanism is more convincing (Appendices C and D).

5. Comparison to CCC

Because of its enormously large mass (considering the observable universe, , where is the mass of the sun), the DO, and all the flows and beams discussed above, must be within a previous-aeon black hole (more specifically, within its inner horizon, see Appendix C). As we know, black holes have maximum entropy (e.g. for a black hole with mass , its entropy: , where kB is the Boltzmann constant), while the Big Bang singularity has minimum entropy (, where is the Planck temperature). It seems obvious that an evolution from a black hole to the Big Bang singularity immensely violates the Second Law of thermodynamics. Penrose therefore chose the ultimate hypersurface to be the crossover in CCC (Penrose 2010, 2020).

In our mechanism, the precursor DO, excluding all the flows and beams, did collapse into the Big Bang singularity with minimum entropy. However, the DO was

absolutely not an isolated system, as the mass-energy flows and beams would continuously be falling into and emitting from it. On the other hand, the collapse and the resulting Big Bang occurred completely within the host black hole. From the exterior (i.e. the previous aeon,

Figure 6) point of view, it was a

normal black hole; its entropy kept increasing as the mass increased:

. Therefore, even if the host black hole is considered as an isolated system, the Second Law is still sustained.

6. Nearly Isotropic and Homogeneous Universe

According to Zel’dovich (1974) and Penrose (1979), the new-born Universe was isotropic and homogeneous. Based on our mechanism, after the collapse of the DO, the Big Bang would first create a counterpart of the DO (Appendix C). The expansion velocity for any part of this rebounded object would be proportional to the distance to the Center: , where the Hubble parameter can be calculated using the first Friedmann equation. It is generally believed that from to sec after the Big Bang, if not earlier, there was an inflation (Guth 1981, 2013; Linde 1982), a process opposite to the collapse. The inflation is generally assumed in the context of the Grand Unified Theory (GUT, Guth 1981, 2013; Linde 1982): , , and . Furthermore, the whole counterpart would spin at an angular speed . Therefore, the created counterpart, except its edge, was isotropic and homogeneous.

For the baby Universe (a flat universe in the matter dominated era), the expansion speed:

where

are the radius, density and mass of the Universe, respectively. As the radius of the Universe was smaller than its Schwarzschild radius:

, the expansion speed of the Universe would be larger than the speed of light:

. The Universe would gain rotational energy from the host black hole, but the speed of spin would be impossible to catch that of expansion:

.

As the Universe expanded, the rotation speed (or energy):

would be converted into that in the rotationally radial direction:

, making the Universe expand slightly faster in the direction parallel to the equator (

) than in the direction parallel to the axis of spin (

,

Figure 4). It is often believed that in the macroscale, the Universe was viscous (Brevik et al. 2017), thus the relatively slower expansion of the higher-

W Universe would pull back the relatively faster expansion of the lower-

W Universe, which is equivalent to a

drift of spacetime from the lower-

W Universe to the higher-

W Universe. In any case, the Universe would be veering into a slightly ellipsoidal shape (

Figure 4).

The centrifugal velocity

(centered at the axis of spin) can be considered as a contribution to the expansion in the radial direction (centered at the Center):

, where

is the Hubble parameter contributed by the spin. With the dominating isotropic expansion velocity

or Hubble parameter

caused by isotropic densities, including radiation, matter, vacuum energy, and possibly spatial curvature densities, we have an overall expansion velocity:

Therefore, the Universe created by our mechanism would be

nearly isotropic and homogeneous.

Another important question one might ask is how the Universe that has been expanding away from the Center looks nearly isotropic and homogeneous, even though it is. To answer this question, we need to first study how light travels. It is generally believed that light travels without a medium. However, as we know, the light emitted from the early Universe (such as the CMB light) travelled first backward (because the spacetime expanded faster than the speed of light: ), then forward, and eventually arrived at us. Of course from our point of view, light would never travel backward. This phenomenon is assumed to be observed from the exterior Universe (i.e. the previous aeon). Similarly, the light emitted by the objects beyond the observable universe will never be seen, because the spacetime there recedes faster than c. Another example is about gravitational lensing. Light bends near a massive object, because the spacetime bends. Therefore, spacetime can be regarded as the medium for light.

Therefore, should we observe the Universe from the exterior (i.e. the previous aeon, using an infinitely large speed of light to observe), the Universe created by our mechanism would expand from the Center (equation 4). However, as we are living within the spacetime of the Universe, we do not notice that we have been moving away from the Center (note that our mechanism does not provide any characteristics at the Center after the Big Bang). From our point of view, the Universe is composed of an infinite number of spheres concentric to us, each of which has its own distance (radius), age (the larger the distance, the older the age), and recessional velocity (Hubble’s law). If we do not consider small anisotropies and consequent inhomogeneities due to the spin (see Appendix B), the observed Universe is isotropic and homogeneous. Identically, the spin of the Universe would only be observed from the exterior Universe. From our point of view, spacetime does not spin or rotate; light always travels straight forward in the Universe.

7. Conclusions

The Universe would emerge from the collapse of the densest object in a previous-aeon black hole. Nature would exist before the Big Bang (in time) and outside this Universe (in space) (

Figure 6).

Acknowledgments

J.B.B. would like to thank Profs. Z. Shen, K. Yao, X. Jiang, F. Bo, Y. Cheng, S. Han, G. Chen, and Q. Yu at Zhejiang University for their inspiration. N.P.B. would like to dedicate this work to his grandparents in China. This work has been pursued upon interest without external financial support.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Data Availability Statement

All results in this paper are obtained using publicly available data.

References

- Aab, A., et al. (Pierre Auger Collaboration) 2017, Scien, 357, 1266.

- Aaronson, M., et al. 1986, ApJ, 302, 536.

- Abada, A., et al. 2006, J. High Eng. Phys., 09, 010.

- Abdalla, E., et al. 2022, J. High Energy Astrophys., 34, 49.

- Ade, P. A. R., et al. (Planck Collaboration) 2016, A&A, 594, A16Aghanim, N., et al. (Planck Collaboration) 2020, A&A, 641, A6.

- Ahlers, M. 2016, PhRvL, 117, 151103.

- Akrami, Y., et al. (Planck Collaboration) 2020, A&A, 641, A7.

- Aluri, P. K., et al. 2023, Class. Quantum Grav., 40, 094001.

- Bao, J.-B., & Bao, N. P. 2021, Prepr, 2020120703 (doi: 10.20944/preprints202012.0703.v2).

- Barbieri, R., et al. 2000, Nucl. Phys. B, 575, 61.

- Battye, R. A., Charnock, T., & Moss, A. 2015, PhRvD, 91, 103508.

- Belinskii, V. A., Khalatnikov, I. M., & Lifshitz, E. M. 1970, Adv. Phys., 19, 525.

- Bennett, C. L., et al. 2001, ApJS, 192, 17.

- Bodnia, E., et al. 2024, JCAP, 2024 (05), 009.

- Boylan-Kolchin, M. 2023, NatAs, 7, 731.

- Brevik, I., et al. 2017, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, 26, 1730024.

- Campanelli, L., Cea, P., & Tedesco, L. 2006, PhRvL, 97, 131302.

- Carlip, S., & Vaidya, S. 2003, Natur, 421, 498.

- Chang, Z., & Lin, H.-N. 2015, MNRAS, 446, 2952.

- Clery, D. 2023, Scien, 379, 1280.

- Davies, P. C. W., Davis, T. M., & Lineweaver, C. H. 2003, Natur, 418, 602.

- Feldman, H. A., Watkins, R., & Hudson, M. J. 2010, MNRAS, 407, 2328.

- Formaggio, J. A., & Zeller, G. P. 2012, Rev. Mod. Phys., 84, 1307.

- Gott III, J. R., et al. 2005, ApJ, 624, 463.

- Gurzadyan, V. G., & Penrose, R. 2013, Eur. Phys. J. Plus, 128, 22.

- Gurzadyan, V. G., & Penrose, R. 2016, Eur. Phys. J. Plus, 131, 11.

- Guth, A. H. 1981, PhRvD, 23, 347.

- Guth, A. H. 2013, Lecture 23: inflation, MIT Open Course Ware.

- Hudson, M. J., et al. 1999, ApJ, 512, L79.

- IceCube Collaboration, 2017, Natur, 551, 596.

- Kashlinsky, A., et al. 2009, ApJ, 691, 1479.

- King, A. R. 1974, Commun. Math. Phys., 38, 157.

- King, J. A., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 422, 3370.

- Kogut, A., et al. 1993, ApJ, 419, 1.

- Kovács, A., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 510, 216.

- Labbé, I., et al. 2023, Natur, 616, 266.

- Linde, A. D. 1982, Phys. Lett., 108B, 389.

- Lynden-Bell, D., et al. 1988, ApJ, 326, 1.

- Marcos-Caballero, A. 2017, The Cosmic Microwave Background radiation at large scales and the peak theory, Univ. Cantabria Thesis.

- Mariano, A., & Perivolaropoulos, L. 2012, PhRvD, 86, 083517.

- Migkas, K., et al. 2021, A&A, 649, A151.

- Penrose, R. 1979, In Hawking, S. W., & Israel, W. (eds), General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey, Cambridge Univ Press, Cambridge, 581.

- Penrose, R. 2010, Cycles of time: an extraordinary new view of the universe, Bodley Head, London.

- Penrose, R. 2020, Black holes, cosmology and space-time singularities. Nobel Lecture. https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2024/02/penrose-lecture.pdf.

- Perivolaropoulos, L., & Skara, F. 2022, New Astron. Rev., 95, 101659.

- Perkins, D. 2003, Particle Astrophysics. 2nd ed., Oxford Univ. Press, New York.

- Perlmutter, S., et al. 1999, ApJ, 517, 565.

- Prakash, N. 2013, Dark matter, neutrinos, and our solar system, World Sci., Singapore.

- Ramond, P. 1983, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci., 33, 31.

- Riess, A. G., et al. 1998, AJ, 116, 1009.

- Riess, A. G., et al. 2022, ApJL, 934, L7.

- Ryden, B. 2017, Introduction to Cosmology. 2nd. ed., Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

- Scheel, M. A., & Thorne, K. S. 2014, Physics-Uspekhi, 57, 342.

- Smolin, L. 1999, The life of the Cosmos, Oxford Univ. Press, New York.

- Tully, R. B., Howlett, C., & Pomarède, D. 2023, ApJ, 954, 169.

- Turnbull, S. J., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 420, 447.

- Wilczek, F. 2001, in Meyers, R. (ed), The Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, 3rd. ed., Academic Press, 339.

- Witze, A. 2022, Natur, 608, 18.

- Zel’dovich, Ya. B. 1974, In Longair, M. S. (ed), Confrontation of cosmological theories with observational data, D. Reidel Pub., Dordrecht, 329.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).