Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Genomes Assemblies Are High-Quality and Contiguous

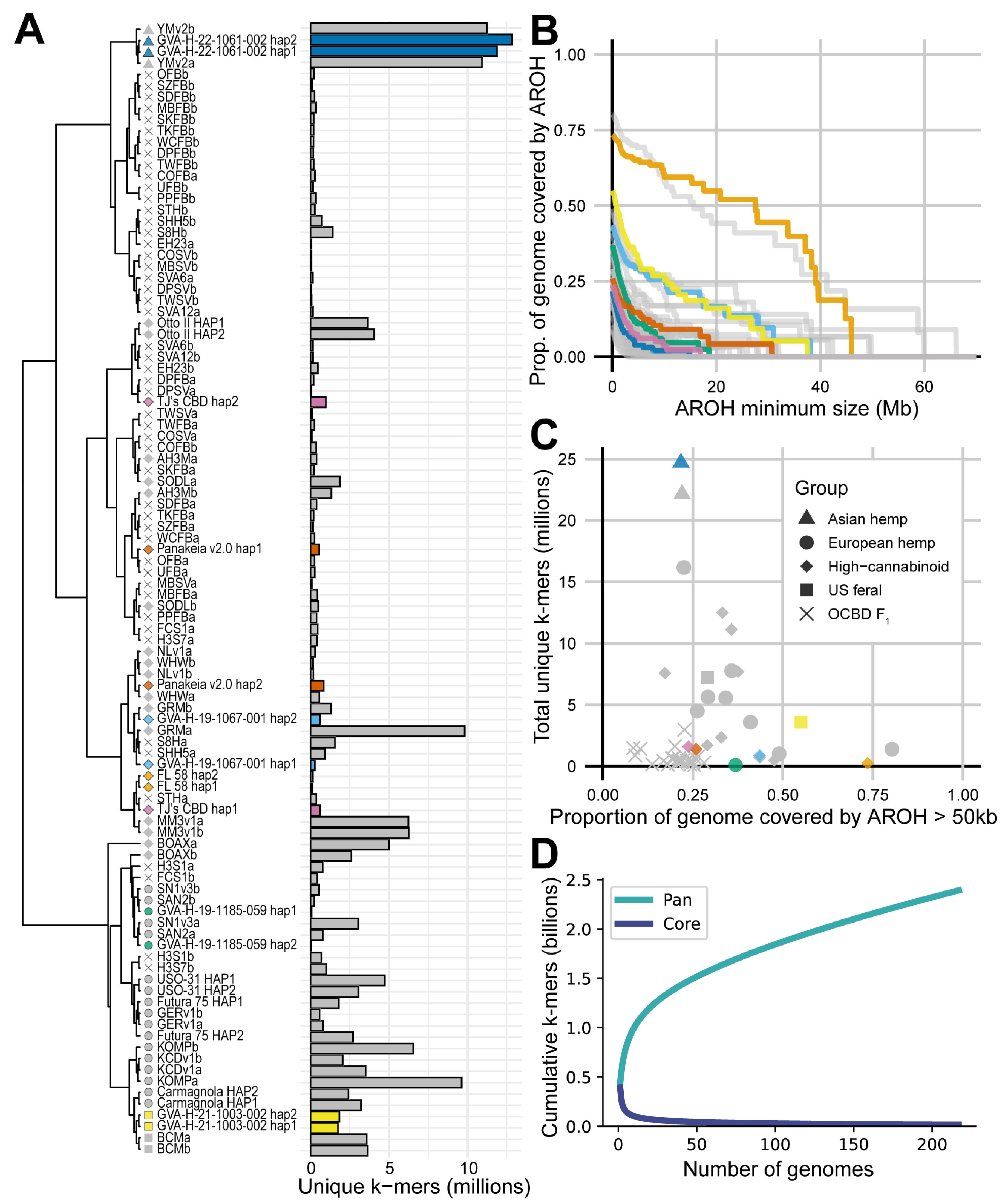

2.2. Phased Chromosome-Level Assemblies Cluster in Agreement with Established Population Structure

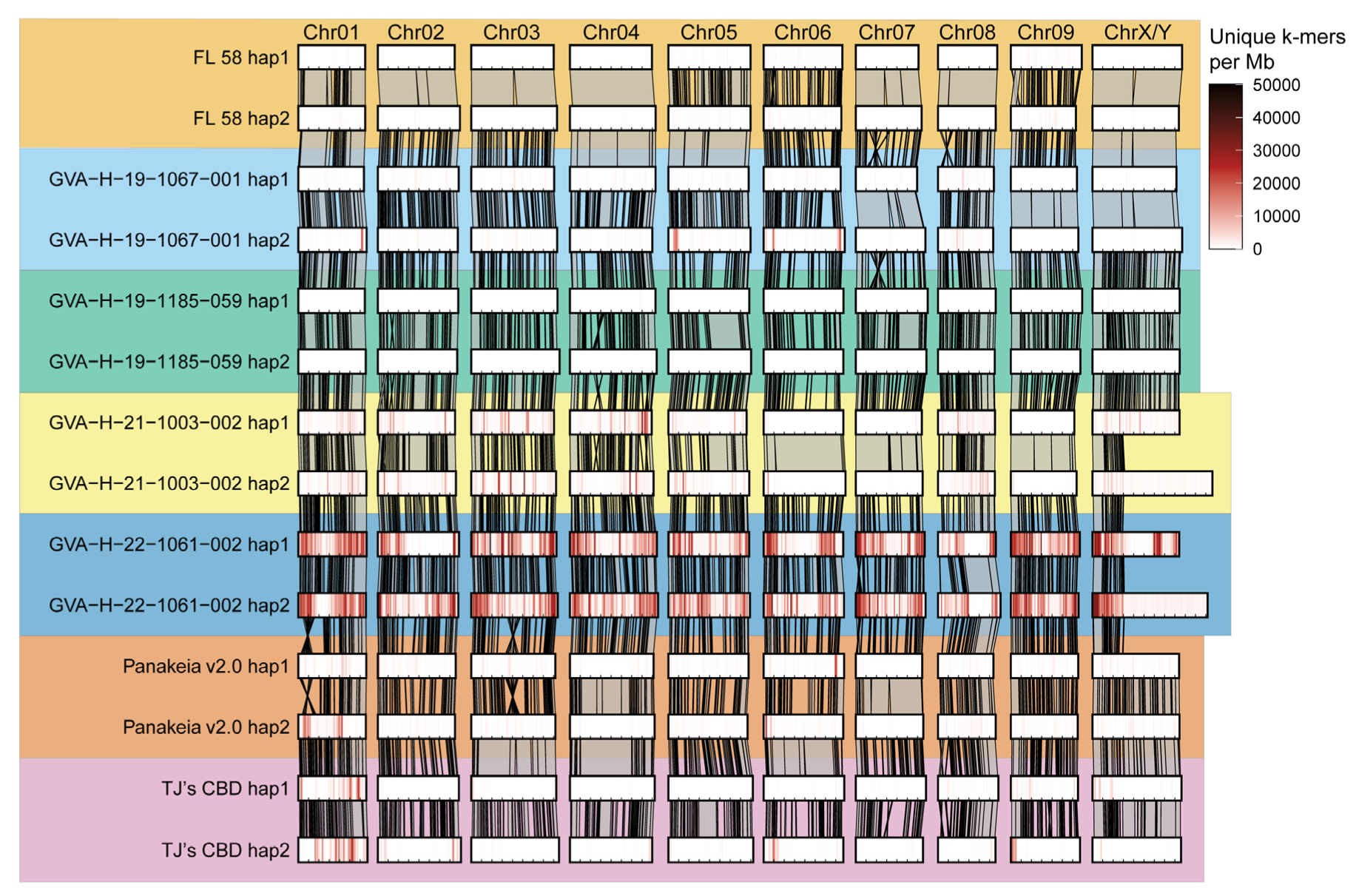

2.3. Assemblies Vary in Number and Position of Unique k-mers

| Genotype | Sex | Chemotype | Source | U.S. NPGS Accession | PacBio HiFi Data (Gb / Reads) | Omni-C® Data (Gb / Reads*) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘FL 58’ | P/XX | III | Sunrise Genetics | G 33236 | 17.9 / 1.25M | 126.8 / 43.0M | [10,18,41,42,43,44] |

| ‘Panakeia v2.0’ | P/XX | IV | Bazelet | - | 16.9 / 1.09M | 107.8 / 37.0M | [10] |

| ‘TJ’s CBD’ | P/XX | III | Stem Holdings Agri | G 33580 | 29.5 / 2.62M | 128.2 / 43.7M | [10,18,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] |

| GVA-H-19-1067-001 | P/XX | III | Cornell Hemp Breeding Prog. | - | 19.3 / 1.18M | 111.8 / 38.3M | [10,44] |

| GVA-H-19-1185-059 | Mo/XX | IV | Cornell Hemp Breeding Prog. | - | 33.9 / 2.17M | 86.2 / 29.3M | [10] |

| GVA-H-21-1003-002 | S/XY | III | Cornell Hemp Breeding Prog. | Derived from G 33199 | 21.9 / 2.66M | 92.3 / 31.6M | [10] |

| GVA-H-22-1061-002 | S/XY | III | Cornell Hemp Breeding Prog. | Derived from G 33545 | 24.3 / 1.50M | 81.9 / 28.0M | [10] |

2.4. Pairwise Haplotype Alignment Can Be Used as a Metric for Homozygosity

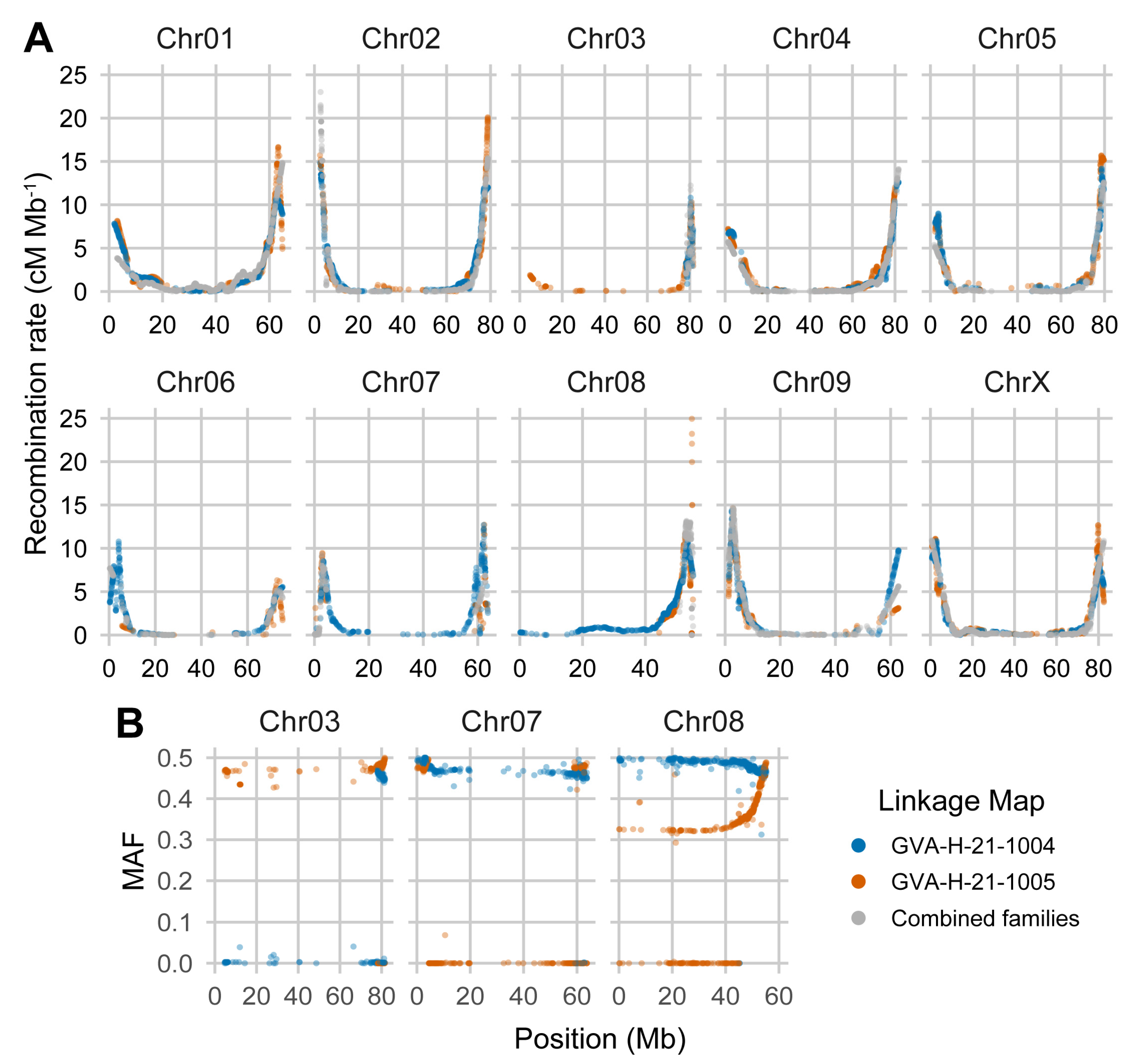

2.5. Chromosomes Show Strong Periphery-Bias in Recombination Rate

2.6. Segregation Distortion and Runs of Monomorphic Markers Restrict Linkage Map Coverage

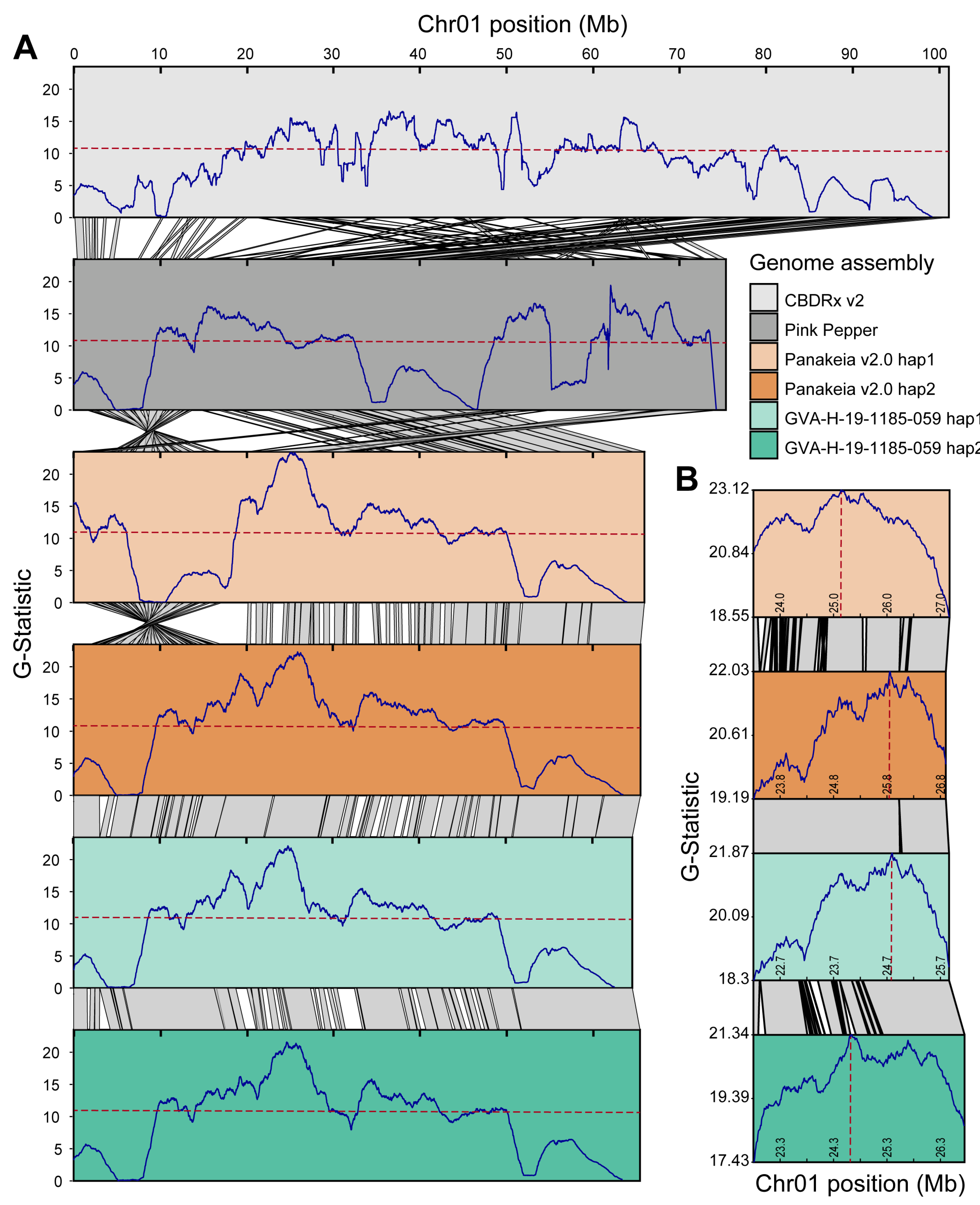

2.7. Bulk Segregant Analysis Mapping of Early1

3. Discussion

3.1. Priorities for Future C. sativa Genome Sequencing

3.2. Characterizing Homozygosity

3.3. Recombination Rates

3.4. Marker Segregation Impacts Linkage Map Construction

3.5. Reference Bias Impacts Trait Mapping Using BSA

3.6. Associated Phenotypes and Loci of Interest

3.7. Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. DNA Isolation and Sequencing

4.2. Genome Assembly and Annotation

4.3. Generation of a PanKmer Index and Identification of Unique k-mers

4.4. Pairwise Alignment of Haplotypes

4.5. Recombination Frequency Estimation

4.6. Early1 BSA Aligning to Various Genome Assemblies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovalchuk, I.; Pellino, M.; Rigault, P.; van Velzen, R.; Ebersbach, J.; Ashnest, J.R.; Mau, M.; Schranz, M.E.; Alcorn, J.; Laprairie, R.B.; et al. The Genomics of Cannabis and Its Close Relatives. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 713–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Ridout, K.; Serrano-Serrano, M.L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, A.; Ravikanth, G.; Nawaz, M.A.; Mumtaz, A.S.; et al. Large-Scale Whole-Genome Resequencing Unravels the Domestication History of Cannabis sativa. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bakel, H.; Stout, J.M.; Cote, A.G.; Tallon, C.M.; Sharpe, A.G.; Hughes, T.R.; Page, J.E. The Draft Genome and Transcriptome of Cannabis sativa. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laverty, K.U.; Stout, J.M.; Sullivan, M.J.; Shah, H.; Gill, N.; Holbrook, L.; Deikus, G.; Sebra, R.; Hughes, T.R.; Page, J.E.; et al. A Physical and Genetic Map of Cannabis sativa Identifies Extensive Rearrangements at the THC/CBD Acid Synthase Loci. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, B.; Xie, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Pei, L.; Yu, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y. A High-Quality Reference Genome of Wild Cannabis sativa. Hortic Res 2020, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassa, C.J.; Weiblen, G.D.; Wenger, J.P.; Dabney, C.; Poplawski, S.G.; Timothy Motley, S.; Michael, T.P.; Schwartz, C.J. A New Cannabis Genome Assembly Associates Elevated Cannabidiol (CBD) with Hemp Introgressed into Marijuana. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalyov, P.D.; Garfinkel, A.R. Discovery and Genetic Mapping of PM1, a Powdery Mildew Resistance Gene in Cannabis sativa L. Frontiers in Agronomy 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.; Campbell, B.J.; Nicodemus, T.J.; Cahoon, E.B.; Mullen, J.L.; McKay, J.K. Quantitative Trait Loci Controlling Agronomic and Biochemical Traits in Cannabis sativa. Genetics 2021, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, J.A.; Stack, G.M.; Carlson, C.H.; Smart, L.B. Identification and Mapping of Major-Effect Flowering Time Loci Autoflower1 and Early1 in Cannabis sativa L. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 991680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, G.M.; Cala, A.R.; Quade, M.A.; Toth, J.A.; Monserrate, L.A.; Wilkerson, D.G.; Carlson, C.H.; Mamerto, A.; Michael, T.P.; Crawford, S.; et al. Genetic Mapping, Identification, and Characterization of a Candidate Susceptibility Gene for Powdery Mildew in Cannabis sativa L. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, L.; Welling, M.; Ristevski, N.; Johnson, K.; Gendall, A. Comparative Genomics of Flowering Behavior in Cannabis sativa. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1227898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, C.A.; Shi, J.; Toth, J.A.; Quade, M.A.; Smart, L.B.; McCabe, P.F.; Schilling, S.; Melzer, R. A FLOWERING LOCUS T Ortholog Is Associated with Photoperiod-Insensitive Flowering in Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Plant J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J.; Salentijn, E.M.J.; Paulo, M.-J.; Denneboom, C.; van Loo, E.N.; Trindade, L.M. Elucidating the Genetic Architecture of Fiber Quality in Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Using a Genome-Wide Association Study. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 566314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, J.; Salentijn, E.M.J.; Paulo, M.-J.; Denneboom, C.; Trindade, L.M. Genetic Architecture of Flowering Time and Sex Determination in Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): A Genome-Wide Association Study. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 569958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welling, M.T.; Liu, L.; Kretzschmar, T.; Mauleon, R. An Extreme-Phenotype Genome-wide Association Study Identifies Candidate Cannabinoid Pathway Genes in Cannabis. Sci. Rep. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ronne, M.; Lapierre, É.; Torkamaneh, D. Genetic Insights into Agronomic and Morphological Traits of Drug-Type Cannabis Revealed by Genome-Wide Association Studies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawler, J.; Stout, J.M.; Gardner, K.M.; Hudson, D.; Vidmar, J.; Butler, L.; Page, J.E.; Myles, S. The Genetic Structure of Marijuana and Hemp. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0133292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, C.H.; Stack, G.M.; Jiang, Y.; Taşkıran, B.; Cala, A.R.; Toth, J.A.; Philippe, G.; Rose, J.K.C.; Smart, C.D.; Smart, L.B. Morphometric Relationships and Their Contribution to Biomass and Cannabinoid Yield in Hybrids of Hemp (Cannabis sativa). J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 7694–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.; Price, N.; Matthews, P.; McKay, J.K. Genome-Wide Polymorphism and Genic Selection in Feral and Domesticated Lineages of Cannabis sativa. G3 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.D.; McKernan, K.; Pauli, C.; Roe, J.; Torres, A.; Gaudino, R. Genomic Characterization of the Complete Terpene Synthase Gene Family from Cannabis sativa. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0222363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pépin, N.; Hebert, F.O.; Joly, D.L. Genome-Wide Characterization of the MLO Gene Family in Cannabis sativa Reveals Two Genes as Strong Candidates for Powdery Mildew Susceptibility. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 729261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, E.J.; Robertson, M.; Taylor, J.; Schultzhaus, Z.; Espinoza, E.M. Oxylipin Biosynthetic Gene Families of Cannabis sativa. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0272893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurgobin, B.; Edwards, D. SNP Discovery Using a Pangenome: Has the Single Reference Approach Become Obsolete? Biology 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, P.J.; Casstevens, T.; Jensen, S.E.; Johnson, L.C.; Miller, Z.R.; Monier, B.; Romay, M.C.; Song, B.; Buckler, E.S. The Practical Haplotype Graph, a Platform for Storing and Using Pangenomes for Imputation. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 3698–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, R.C.; Padgitt-Cobb, L.K.; Garfinkel, A.R.; Knaus, B.J.; Hartwick, N.T.; Allsing, N.; Aylward, A.; Mamerto, A.; Kitony, J.K.; Colt, K.; et al. Domesticated Cannabinoid Synthases amid a Wild Mosaic Cannabis Pangenome. bioRxiv, 2024; 2024.05.21.595196. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, S.B.; Havill, J.S.; Bentz, P.C.; Akozbek, L.M.; Lovell, J.T.; Pagitt-Cobb, L.; Lynch, R.; Allsing, N.; Osmanski, A.; Easterling, K.; Orozco, L.; Hale, H.; Mueller, H.; Meharg, Z.; McKay, J.; Grimwood, J.; Guerrero, R.; Vergara, D.; Kane, N.; Michael, T.P.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Harkess, A. The Evolution of Heteromorphic Sex Chromosomes in Plants. in prep.

- Hirata, K. Sex Determination in Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). J. Genet. 1927, 19, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.; Cronquist, A. A Practical and Natural Taxonomy for Cannabis. Taxon 1976, 25, 405–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPartland, J.M.; Small, E. A Classification of Endangered High-THC Cannabis (Cannabis sativa Subsp. Indica) Domesticates and Their Wild Relatives. PhytoKeys 2020, 144, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soorni, A.; Fatahi, R.; Haak, D.C.; Salami, S.A.; Bombarely, A. Assessment of Genetic Diversity and Population Structure in Iranian Cannabis Germplasm. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, R.C.; Vergara, D.; Tittes, S.; White, K.; Schwartz, C.J.; Gibbs, M.J.; Ruthenburg, T.C.; deCesare, K.; Land, D.P.; Kane, N.C. Genomic and Chemical Diversity in Cannabis. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2016, 35, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, D.Y.C.; Aguiar, V.R.C.; Bitarello, B.D.; Nunes, K.; Goudet, J.; Meyer, D. Mapping Bias Overestimates Reference Allele Frequencies at the HLA Genes in the 1000 Genomes Project Phase I Data. G3 2015, 5, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, T.; Nettelblad, C. The Presence and Impact of Reference Bias on Population Genomic Studies of Prehistoric Human Populations. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, G.; Monlong, J.; Ebler, J.; Novak, A.M.; Eizenga, J.M.; Gao, Y.; Human Pangenome Reference Consortium; Marschall, T. ; Li, H.; Paten, B. Pangenome Graph Construction from Genome Alignments with Minigraph-Cactus. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiente-Mullor, C.; Beamud, B.; Ansari, I.; Francés-Cuesta, C.; García-González, N.; Mejía, L.; Ruiz-Hueso, P.; González-Candelas, F. One Is Not Enough: On the Effects of Reference Genome for the Mapping and Subsequent Analyses of Short-Reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, R.; Sajai, N.; Zelkowski, M.; Zhou, A.; Robbins, K.R.; Pawlowski, W.P. Exploring Impact of Recombination Landscapes on Breeding Outcomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2205785119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taagen, E.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Sorrells, M.E. Counting on Crossovers: Controlled Recombination for Plant Breeding. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, F.; Bolger, A.; Günther, C.; Maß, J.; Triesch, S.; Kindel, F.; Kiel, N.; Saadat, N.; Ebenhöh, O.; Usadel, B.; et al. Helixer–de Novo Prediction of Primary Eukaryotic Gene Models Combining Deep Learning and a Hidden Markov Model. bioRxiv, 2023; 2023.02.06.527280. [Google Scholar]

- Aylward, A.J.; Petrus, S.; Mamerto, A.; Hartwick, N.T.; Michael, T.P. PanKmer: K-Mer-Based and Reference-Free Pangenome Analysis. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandolino, G.; Carboni, A. Potential of Marker-Assisted Selection in Hemp Genetic Improvement. Euphytica 2004, 140, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Young, S.; Linder, E.; Whipker, B.; Suchoff, D. Hyperspectral Imaging With Machine Learning to Differentiate Cultivars, Growth Stages, Flowers, and Leaves of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 810113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, G.M.; Toth, J.A.; Carlson, C.H.; Cala, A.R.; Marrero-González, M.I.; Wilk, R.L.; Gentner, D.R.; Crawford, J.L.; Philippe, G.; Rose, J.K.C.; et al. Season-long Characterization of High-cannabinoid Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Reveals Variation in Cannabinoid Accumulation, Flowering Time, and Disease Resistance. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2021, 13, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, L.B.; Toth, J.A.; Stack, G.M.; Monserrate, L.A.; Smart, C.D. Breeding of Hemp (Cannabis sativa). In Plant Breeding Reviews; Goldman, I., Ed.; Wiley, 2022; Vol. 46, pp. 239–288 ISBN 9781119874126.

- Stack, G.M.; Carlson, C.H.; Toth, J.A.; Philippe, G.; Crawford, J.L.; Hansen, J.L.; Viands, D.R.; Rose, J.K.C.; Smart, L.B. Correlations among Morphological and Biochemical Traits in High-Cannabidiol Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Plant Direct 2023, 7, e503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, W.A.; Ullrich, M.R.; Smart, L.B.; Smart, C.D.; Gadoury, D.M. Cross-Infectivity of Powdery Mildew Isolates Originating from Hemp (Cannabis sativa) and Japanese Hop (Humulus japonicus) in New York. Plant Health Prog. 2020, 21, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; Smart, L.B.; Hijri, M. Microbiome of Field Grown Hemp Reveals Potential Microbial Interactions With Root and Rhizosphere Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 741597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, J.A.; Smart, L.B.; Smart, C.D.; Stack, G.M.; Carlson, C.H.; Philippe, G.; Rose, J.K.C. Limited Effect of Environmental Stress on Cannabinoid Profiles in High-cannabidiol Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, C.; Zayas, V.A.; Galic, A.; Bridgen, M.P. Micropropagation of Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). HortScience 2023, 58, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise Alignment for Nucleotide Sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, G.; Beherec, O.; Bertucelli, S. Santhica 23 et 27: deux variétés de chanvre (Cannabis sativa L.) sans Δ-9-THC. Ann. Toxicol. Anal. 2004, 16, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bócsa, I. Interview Professor Dr. Iván Bócsa, the Breeder of Kompolti Hemp. J. Int. Hemp Assoc. 1994, 1, 61–62. [Google Scholar]

- de Meijer, E. Fibre Hemp Cultivars: A Survey of Origin, Ancestry, Availability and Brief Agronomic Characteristics. J. Int. Hemp Assoc. 1995, 2, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ranalli, P. Current Status and Future Scenarios of Hemp Breeding. Euphytica 2004, 140, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salentijn, E.M.J.; Zhang, Q.; Amaducci, S.; Yang, M.; Trindade, L.M. New Developments in Fiber Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Breeding. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 68, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.C.; Merlin, M.D. Cannabis Domestication, Breeding History, Present-Day Genetic Diversity, and Future Prospects. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2016, 35, 293–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, L. Hemp Varieties of Improved Type Are Result of Selection. In What ’s new in agriculture. Yearbook of the United States Department of Agriculture—1927; Government Printing Office: Washington, D.C, 1928; pp. 358–361. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, D.; Willis, J.H. The Genetics of Inbreeding Depression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 783–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crnokrak, P.; Barrett, S.C.H. Perspective: Purging the Genetic Load: A Review of the Experimental Evidence. Evolution 2002, 56, 2347–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, S.; Fay, J.C. Evidence for Hitchhiking of Deleterious Mutations within the Human Genome. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haenel, Q.; Laurentino, T.G.; Roesti, M.; Berner, D. Meta-Analysis of Chromosome-Scale Crossover Rate Variation in Eukaryotes and Its Significance to Evolutionary Genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 2477–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazier, T.; Glémin, S. Diversity and Determinants of Recombination Landscapes in Flowering Plants. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Jin, W.; Nagaki, K.; Tian, S.; Ouyang, S.; Buell, C.R.; Talbert, P.B.; Henikoff, S.; Jiang, J. Transcription and Histone Modifications in the Recombination-Free Region Spanning a Rice Centromere. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3227–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, D.K. Cannabis Plant with Increased Cannabichromenic Acid. World Patent 2022.

- Schalamun, M.; Schwessinger, B. High Molecular Weight GDNA Extraction after Mayjonade et al. Optimised for Eucalyptus for Nanopore Sequencing. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Concepcion, G.T.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, H. Haplotype-Resolved de Novo Assembly Using Phased Assembly Graphs with Hifiasm. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astashyn, A.; Tvedte, E.S.; Sweeney, D.; Sapojnikov, V.; Bouk, N.; Joukov, V.; Mozes, E.; Strope, P.K.; Sylla, P.M.; Wagner, L.; et al. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Genome Contamination at Scale with FCS-GX. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovetail Genomics Dovetail Omni-C 0.1 Documentation. Available online: https://omni-c.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Zhou, C.; McCarthy, S.A.; Durbin, R. YaHS: Yet Another Hi-C Scaffolding Tool. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, N.C.; Shamim, M.S.; Machol, I.; Rao, S.S.P.; Huntley, M.H.; Lander, E.S.; Aiden, E.L. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst 2016, 3, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanettes, F.; Klopp, C. D-GENIES: Dot Plot Large Genomes in an Interactive, Efficient and Simple Way. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, G.; Pertea, M. GFF Utilities: GffRead and GffCompare. F1000Res. 2020, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. EggNOG-Mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Simão, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv [q-bio.GN], 2013. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Taylor, J.; Butler, D. R Package ASMap: Efficient Genetic Linkage Map Construction and Diagnosis. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 79, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broman, K.W.; Wu, H.; Sen, S.; Churchill, G.A. R/Qtl: QTL Mapping in Experimental Crosses. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 889–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; Del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From FastQ Data to High Confidence Variant Calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit Best Practices Pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 2013, 43, 11.10.1–11.10.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The Variant Call Format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Panthee, D.R. PyBSASeq: A Simple and Effective Algorithm for Bulked Segregant Analysis with Whole-Genome Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2020, 21, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persephone Software, L.L.C. Persephone® Genome Browser. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer, 2016; ISBN 9783319242774.

| Publication | N samples | N groups | High-cannabinoid group(s) | European hemp group(s) | Asian hemp group | Other group(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sawler et al. [17] | 124 | 2 | Marijuana | Hemp | n/a | n/a |

| Soorni et al. [30] | 209 | 4 | Marijuana | Hemp CGN/IPK |

n/a | Iran |

| Lynch et al. [31] | 340 | 3 | BLDT NLDT |

Hemp | n/a | n/a |

| Grassa et al. [6] | 367 | 3 | Marijuana | Hemp | n/a | Naturalized |

| Carlson et al. [18] | 190 | 7 | T1/R4; Cherry West Coast BaOx/Otto II |

Grain/Dual Fiber/Feral |

Chinese | n/a |

| Ren et al. [2] | 110 | 4 | Drug-type Drug-type Feral |

Hemp-type | n/a | Basal Cannabis |

| Woods et al. [19] | 190 | 4 | Marijuana | European | Asian | U.S. Feral |

| Lynch et al. [25] | 193 | 5 | Drug-type ERB & EH23b Drug-type HO40 & EH23a |

European Hemp and Feral | Asian Hemp | Wild Tibet |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).