Submitted:

24 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overview on Overtopping Research

3. Methodology

4. Results

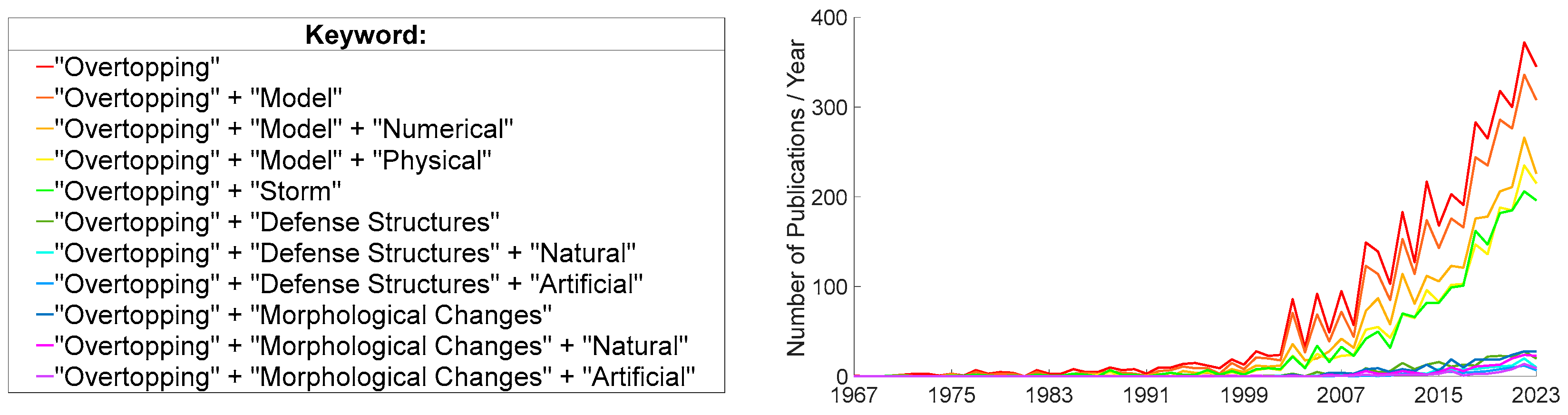

4.1. Evolution on Overtopping Research

4.2. Models

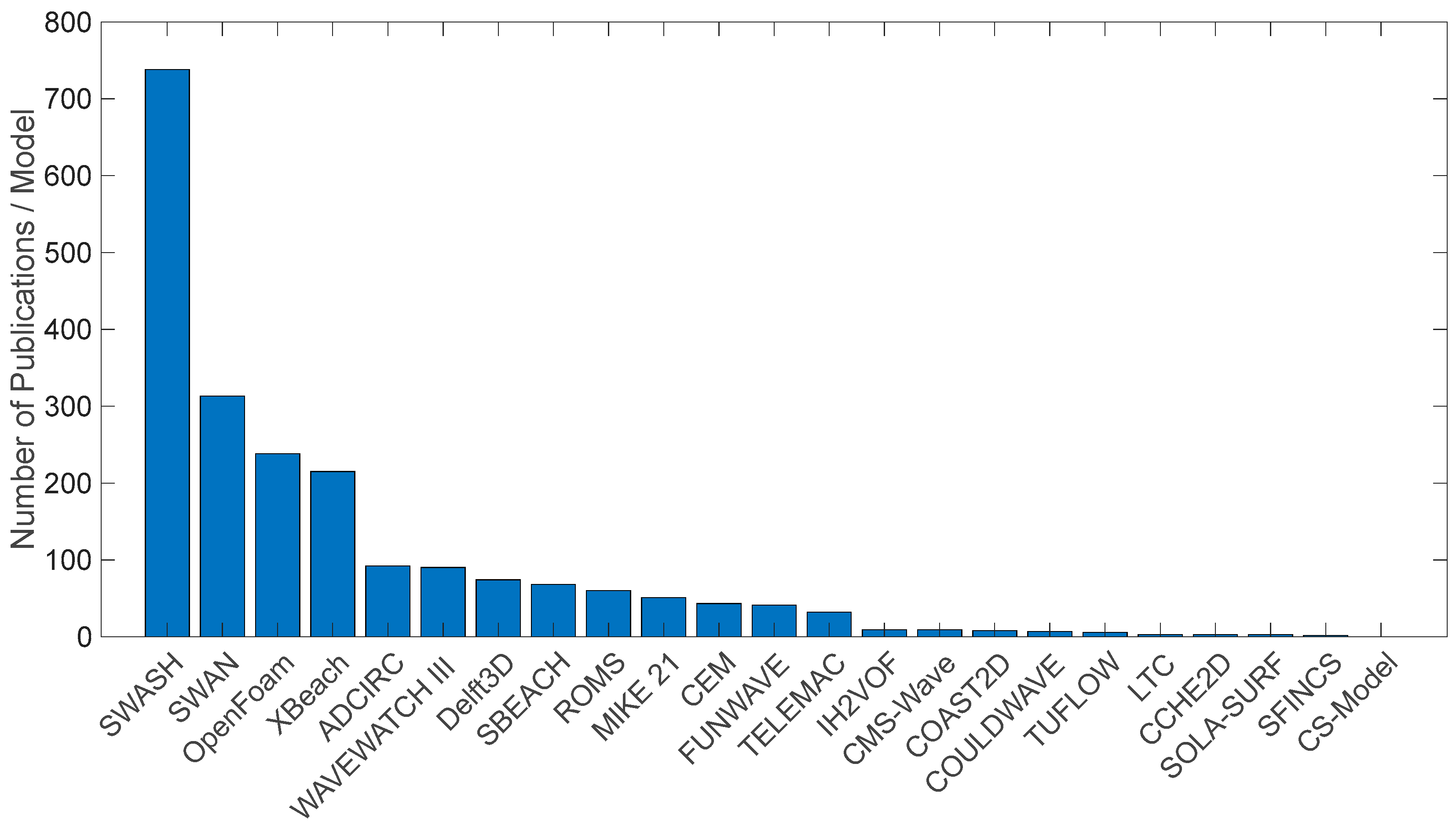

4.2.1. Numerical Models

4.2.2. Physical Models

4.3. Storms

4.4. Defence Structures

4.4.1. Natural

4.4.2. Artificial

4.5. Morphological Changes

4.5.1. Natural

4.5.2. Artificial

5. Discussion

5.1. Overtopping and Models

5.2. Overtopping and Storms

5.3. Overtopping and Defense Structures

5.4. Overtopping and Morphological Changes

6. Conclusions

References

- Dada, O.A.; Almar, R.; Morand, P. Coastal vulnerability assessment of the West African coast to flooding and erosion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, B.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Zimmermann, J.; Nicholls, R.J. Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding-a global assessment. PloS ONE 2015, 10, e0118571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobeto, H.; Semedo, A.; Lemos, G.; Dastgheib, A.; Menendez, M.; Ranasinghe, R.; Bidlot, J.-R. Global coastal wave storminess. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radfar, S.; Mahmoudi, S.; Moftakhari, H.; Meckley, T.; Bilskie, M.V.; Collini, R.; Alizad, K.; Cherry, J.A.; Moradkhani, H. Nature-based solutions as buffers against coastal compound flooding: Exploring potential framework for process-based modeling of hazard mitigation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 938, 173529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, W., Simon, S., Dusek, G., Marcy, D., Brooks, W., Pendleton, M., & Marra, J. (2021). 2021 State of High Tide Flooding and Annual Outlook. NOAA.

- Helderop, E.; Grubesic, T.H. Social, geomorphic, and climatic factors driving U.S. coastal city vulnerability to storm surge flooding. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H. Climate change impact on flood and extreme precipitation increases with water availability. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, M.; Farfán, J.F.; Willems, P.; Cea, L. Assessing the Effects of Climate Change on Compound Flooding in Coastal River Areas. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Lincke, D.; Hinkel, J.; Brown, S.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Meyssignac, B.; Hanson, S.E.; Merkens, J.-L.; Fang, J. A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, J.L.; Ferreira, .; Reis, M.T.; Ferreira, A.; Fortes, C.J.E.M.; Zózimo, A.C. Conceptual and quantitative categorization of wave-induced flooding impacts for pedestrians and assets in urban beaches. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Zou, Q.-P.; Mignone, A.; MacRae, J.D. Coastal flooding from wave overtopping and sea level rise adaptation in the northeastern USA. Coast. Eng. 2019, 150, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.N.C.; Oliveira, F.S.B.F.; Neves, M.G.; Clavero, M.; Trigo-Teixeira, A.A. Modeling Wave Overtopping on a Seawall with XBeach, IH2VOF, and Mase Formulas. Water 2020, 12, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rees, C.B.; Hernández-Abrams, D.D.; Shudtz, M.; Lammers, R.; Byers, J.; Bledsoe, B.P.; Bilskie, M.V.; Calabria, J.; Chambers, M.; Dolatowski, E.; et al. Reimagining infrastructure for a biodiverse future. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, A.; Roy, D.; Filatova, T. Capitalized value of evolving flood risks discount and nature-based solution premiums on property prices. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, G.; Liu, S.; Qiao, L.; Yu, Y.; Liu, X. Field observations of seabed scour dynamics in front of a seawall during winter gales. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatchez, P.; Fraser, C. Evolution of Coastal Defence Structures and Consequences for Beach Width Trends, Québec, Canada. J. Coast. Res. 2012, 285, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.C.; Cardona, F.S.; Santos, C.J.; Tenedório, J.A. Hazards, Vulnerability, and Risk Analysis on Wave Overtopping and Coastal Flooding in Low-Lying Coastal Areas: The Case of Costa da Caparica, Portugal. Water 2021, 13, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, A.; Masselink, G.; Castelle, B.; Blenkinsopp, C.E.; Kroon, A. Measurements of morphodynamic and hydrodynamic overwash processes in a large-scale wave flume. Coast. Eng. 2016, 113, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.W.; Liu, B.; Pepper, D.A.; Wang, P. The importance of extratropical and tropical cyclones on the short-term evolution of barrier islands along the northern Gulf of Mexico, USA. Mar. Geol. 2004, 210, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.W., Webb, R.M.T., Bush, D.M. (1994). Another look at the impact of Hurricane Hugo on the shelf and coastal resources of Puerto Rico, U.S.A. Journal of Coastal Research, 10(2), 278–296.

- Tominaga, Y., Hashimoto, H. & Sakuma, N. (1967). Wave rum-up and overtopping on coastal dikes. Proceedings of the Coastal Engineering Conference, 364–38.

- Shankar, N.; Jayaratne, M. Wave run-up and overtopping on smooth and rough slopes of coastal structures. Ocean Eng. 2003, 30, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindar, R.; Sriram, V.; Salauddin, M. Numerical modelling of breaking wave impact loads on a vertical seawall retrofitted with different geometrical configurations of recurve parapets. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2022, 13, 3644–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.A.; O’sullivan, J.J.; Abolfathi, S.; Salauddin, M. Enhanced wave overtopping simulation at vertical breakwaters using machine learning algorithms. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0289318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EurOtop, 2018. In: Van der Meer, J.W., Allsop, N.W.H., Bruce, T., De Rouck, J., Kortenhaus, A., Pullen, T., Schüttrumpf, H., Troch, P., Zanuttigh, B. (Eds.), Manual on Wave Overtopping of Sea Defenses and Related Structures. An Overtopping Manual Largely Based on European Research, but for Worldwide Application, p. 320. www.overtopping-manual.com.

- Jin, Y.; Wang, W.; Kamath, A.; Bihs, H. Numerical Investigation on Wave-Overtopping at a Double-Dike Defence Structure in Response to Climate Change-Induced Sea Level Rise. Fluids 2022, 7, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.; Coelho, C.; Jesus, F. Wave Overtopping and Flooding Costs in the Pre-Design of Longitudinal Revetments. Water 2023, 15, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Wang, X.; Qu, K.; Zhang, L.B. Hydrodynamic Loads and Overtopping Processes of a Coastal Seawall under the Coupled Impact of Extreme Waves and Wind. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenkinsopp, C.E.; Baldock, T.E.; Bayle, P.M.; Foss, O.; Almeida, L.P.; Schimmels, S. Remote Sensing of Wave Overtopping on Dynamic Coastal Structures. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnitti, M.; Lara, J.; Musumeci, R.; Foti, E. Numerical modeling of wave overtopping of damaged and upgraded rubble-mound breakwaters. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnitti, M.; Lara, J.L.; Musumeci, R.E.; Foti, E. Assessment of the variation of failure probability of upgraded rubble-mound breakwaters due to climate change. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lauro, E.; Maza, M.; Lara, J.L.; Losada, I.J.; Contestabile, P.; Vicinanza, D. Advantages of an innovative vertical breakwater with an overtopping wave energy converter. 2020, 159, 103713. [CrossRef]

- Lara, J.L.; Lucio, D.; Tomas, A.; Di Paolo, B.; Losada, I.J. High-resolution time-dependent probabilistic assessment of the hydraulic performance for historic coastal structures: application to Luarca Breakwater. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2019, 377, 20190016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SWASH (2024). User manual. Delft University of Technology Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences Environmental Fluid Mechanics, The Netherlands. Available online: http://www.tudelft.nl/swash (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- SWAN (2024). User manual. Delft University of Technology Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences Environmental Fluid Mechanics, The Netherlands. Available online: http://www.swan.tudelft.nl (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- OpenFoam (2024). User Guide. ESI Group. Available online: https://www.openfoam.com/documentation/user-guide (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- XBeach (2024). User manual. Available online: https://xbeach.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Luettich, R.; Westerink, J. (2024). ADCIRC user manual. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA. Available online: https://adcirc.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- WAVEWATCH III (2016). User manual and system documentation of WAVEWATCH III version 5.16. Tech. Note 329, NOAA/NWS/NCEP/MMAB, College Park, MD, USA, 326 pp. + Appendices. Available online: https://polar.ncep.noaa.gov/waves/wavewatch/manual.v5.16.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Delft3D (2024). User manual: 3D/2D modelling suite for integral water solutions; Deltares; The Netherlands. Hydro-Morphodynamics. Available online: https://oss.deltares.nl/web/delft3d/manuals (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Sommerfeld, B. G., Kraus, N. C. & Larson, M. (1996). SBEACH-32 interface user’s manual, Final Report. U.S. Army Corps of Engineerings, Jacksonville, Florida.

- Hedström, K. S. (2018). ROMS user manual: Technical Manual for a Coupled Sea-Ice/Ocean Circulation Model (Version 5). College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences University of Alaska Fairbanks. Available online: https://github.com/kshedstrom/roms_manual/blob/master/roms_manual.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- MIKE 21 (2024). User manual. Available online: https://manuals.mikepoweredbydhi.help/latest/MIKE_21.htm (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- CEM (2024). User manual. Available online: https://csdms.colorado.edu/wiki/Model:CEM (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Kirby, J. T., Wei, G., Chen, Q., Kennedy, A. B. & Dalrymple, R. A. (1998). FUNWAVE 1.0 Fully Nonlinear Boussinesq Wave Model – Documentation and user manual. Center for Applied Coastal Research, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Delaware, Newark, DE; Research report.

- ATA, R., Goeury, C. & Hervouet, J. M. (2014). TELEMAC MODELLING SYSTEM, 2D hydrodynamics. USER MANUAL.

- IH2VOF (2024). User guide. University of Cantabria. Available online: https://ih2vof.ihcantabria.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Sánchez, A., Beck, T., Lin, L., Demirbilek, Z., Brown, M. & Li, H. (2012). CMS-Wave: Coastal Modeling System Draft User Manual.

- COAST2D (2024). Available online: https://coast2d.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Lynett, P. J., & Liu, P. L. F. (2008). Modeling Wave Generation, Evolution, and Interaction with Depth-Integrated, Dispersive Wave Equations: COULWAVE Code Manual. Cornell University Long and Intermediate Wave Modeling Package v. 2.0 Originally.

- TUFLOW (2024). TUFLOW Classic, HPC User Manual. Build 2018-03-AD. BMT.

- Coelho, C. Riscos de Exposição de Frentes Urbanas para Diferentes Intervenções de Defesa Costeira. PhD Thesis, (in portuguese). University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2005; p. 404. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. & Wang S. S. Y. (2001). CCHE2D: Two-dimensional Hydrodynamic and Sediment Transport Model for Unsteady Open Channel Flows Over Loose Bed, Technical Report No. NCCHE-TR-2001-1. School of Engineering, The University of Mississippi.

- SOLA-SURF (2024). User Manual. Available online: https://www.oecd-nea.org/tools/abstract/detail/nesc0651/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- SFINCS (2024). User Manual. Available online: https://sfincs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Larson, M.; Palalane, J.; Fredriksson, C.; Hanson, H. Simulating cross-shore material exchange at decadal scale. Theory and model component validation. Coast. Eng. 2016, 116, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Pan, S.; Chen, Y. Modelling the effect of wave overtopping on nearshore hydrodynamics and morphodynamics around shore-parallel breakwaters. Coast. Eng. 2010, 57, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Kirby, J.T.; Harris, J.C.; Geiman, J.D.; Grilli, S.T. A high-order adaptive time-stepping TVD solver for Boussinesq modeling of breaking waves and coastal inundation. Ocean Model. 2012, 43-44, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Malej, M.; Smith, J.M.; Kirby, J.T. Breaking of ship bores in a Boussinesq-type ship-wake model. Coast. Eng. 2018, 132, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, I.; Kirby, J.; Shi, F.; Grilli, S. ESTIMATING METEO-TSUNAMI OCCURRENCES FOR THE US EAST COAST. Coast. Eng. Proc. 2018, 1, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranirad, B., Kirby, J. T. & Shi, F. (2016). Does Morphological Adjustment During Tsunami Inundation Increase Levels of Hazard? Research Report No. CACR-16-02. Center for Applied Coastal Research. Ocean Engineering Laboratory, University of Delaware, Newark.

- Chen, X.; Hofland, B.; Altomare, C.; Suzuki, T.; Uijttewaal, W. Forces on a vertical wall on a dike crest due to overtopping flow. Coast. Eng. 2015, 95, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, R.; Musumeci, R.E.; van der Meer, J.; Romano, A.; Stancanelli, L.M.; Kudella, M.; Akbar, R.; Mukhdiar, R.; Altomare, C.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Wave overtopping at near-vertical seawalls: Influence of foreshore evolution during storms. Ocean Eng. 2022, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruwez, V.; Altomare, C.; Suzuki, T.; Streicher, M.; Cappietti, L.; Kortenhaus, A.; Troch, P. Validation of RANS Modelling for Wave Interactions with Sea Dikes on Shallow Foreshores Using a Large-Scale Experimental Dataset. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomare, C.; Gironella, X.; Crespo, A.J. Simulation of random wave overtopping by a WCSPH model. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 116, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Altomare, C.; Willems, M.; Dan, S. Non-Hydrostatic Modelling of Coastal Flooding in Port Environments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, H.; Pender, D.; Ranasinghe, R.; Short, A.D.; Reeve, D.E. The effects of storm clustering on beach profile variability. Mar. Geol. 2014, 348, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. P.; Losada, I. J.; Gattuso, J. P.; Hinkel, J; Khattabi, A.; McInnes, K. L.; Saito, Y.; Sallenger, A.; Nicholls, R. J.; Santos, F.; Amez, S. Coastal Systems and Low-Lying Areas. In Climate Change 2014 Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability: Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 361–410.

- Harley, M. (2017). Coastal storm definition. Coastal Storms: Processes and Impacts, pp. 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Martzikos, N.T.; Prinos, P.E.; Memos, C.D.; Tsoukala, V.K. Key research issues of coastal storm analysis. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 199, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glossary of Meteorology of American Meteorological Society (2024). Available online: https://www.ametsoc.org/index.cfm/ams/publications/glossary-of-meteorology/. (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Boccotti, P. (2000). Wave Mechanics for Ocean Engineering. Elsevier Science B.V., Amesterdam, The Netherlands. ISBN: 978-0-080-54372-7.

- Lira-Loarca, A.; Cobos, M.; Losada, M. .; Baquerizo, A. Storm characterization and simulation for damage evolution models of maritime structures. Coast. Eng. 2019, 156, 103620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. C. & Pirrello, M. A. (2001). Applying joint probabilities and cumulative effects to estimate storm induced erosion and shoreline recession. Shore & Beach, 69(2), 5-7.

- Zou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Cluckie, I.; Hewston, R.; Pan, S.; Peng, Z.; Reeve, D. Ensemble prediction of coastal flood risk arising from overtopping by linking meteorological, ocean, coastal and surf zone models. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2013, 139, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouakou, M.; Tiémélé, J.A.; Djagoua, .; Gnandi, K. Assessing potential coastal flood exposure along the Port-Bouët Bay in Côte d’Ivoire using the enhanced bathtub model. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 105001. [CrossRef]

- Geeraerts, J.; Troch, P.; De Rouck, J.; Verhaeghe, H.; Bouma, J. Wave overtopping at coastal structures: prediction tools and related hazard analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomaritis, T.A.; Ferreira, .; Costas, S. Regional assessment of storm related overwash and breaching hazards on coastal barriers. Coast. Eng. 2018, 134, 124–133. [CrossRef]

- Sallenger, A. H. (2000). Storm impact scale for barrier islands. Journal of Coastal Research, 16(3), pp. 890–895.

- EurOtop, 2007. In: Pullen, T., Allsop, N.W.H., Kortenhaus, A., Schüttrumpf, H., Van der Meer, J.W. (Eds.), Wave Overtopping of Sea Defenses and Related Structures: Assessment Manual, p. 178. www.overtopping-manual.com.

- Gallien, T.; Sanders, B.; Flick, R. Urban coastal flood prediction: Integrating wave overtopping, flood defenses and drainage. Coast. Eng. 2014, 91, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis, J. W. (2020). Introduction to Coastal Engineering and Management: Third Edition. Advanced Series on Ocean Engineering, 48, pp. 1–542. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.W., Bush, D.M., Neal, W.J. (2012). Documenting beach loss in front of seawalls in Puerto Rico: pitfalls of engineering a small island nation shore. Coastal Research Library, 3, pp. 53–71. [CrossRef]

- Rubinato, M.; Heyworth, J.; Hart, J. Protecting Coastlines from Flooding in a Changing Climate: A Preliminary Experimental Study to Investigate a Sustainable Approach. Water 2020, 12, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, M.; Mendoza, E.; Silva, R. Micro Sand Engine Beach Stabilization Strategy at Puerto Morelos, Mexico. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odériz, I.; Knöchelmann, N.; Silva, R.; Feagin, R.A.; Martínez, M.L.; Mendoza, E. Reinforcement of vegetated and unvegetated dunes by a rocky core: A viable alternative for dissipating waves and providing protection? Coast. Eng. 2020, 158, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal of Integrated Coastal Management (2024). Glossary online: https://www.aprh.pt/rgci/glossario/index.html. (Accessed on 12th October 2024).

- Senturk, B.U.; Guler, H.G.; Baykal, C. Numerical simulation of scour at the rear side of a coastal revetment. Ocean Eng. 2023, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, C.; Gracia, V.; Cáceres, I.; Sierra, J.P.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Beach profile changes induced by surrogate Posidonia Oceanica: Laboratory experiments. Coast. Eng. 2022, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’alessandro, F.; Tomasicchio, G.R.; Frega, F.; Leone, E.; Francone, A.; Pantusa, D.; Barbaro, G.; Foti, G. Beach–Dune System Morphodynamics. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayaka, K.D.C.R.; Tanaka, N.; Hasan, K. Effect of Orientation and Vegetation over the Embankment Crest for Energy Reduction at Downstream. Geosciences 2022, 12, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, S. Experiments and Numerical Simulations of Dike Erosion due to a Wave Impact. Water 2015, 7, 5831–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C., Ferreira, A. M. & Lima, M. (2024). Numerical Modeling of Artificial Nourishments on the Beach Profile: Effects on Reducing Dune Overtopping. Journal of Coastal Research, 113, 599-603. [CrossRef]

- Formentin, S.M.; Zanuttigh, B. A Genetic Programming based formula for wave overtopping by crown walls and bullnoses. Coast. Eng. 2019, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanitwong-Na-Ayutthaya, S.; Saengsupavanich, C.; Ariffin, E.H.; Ratnayake, A.S.; Yun, L.S. Environmental impacts of shore revetment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengsupavanich, C.; Ariffin, E.H.; Yun, L.S.; Pereira, D.A. Environmental impact of submerged and emerged breakwaters. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Qu, Z.; Lee, D.Y.; Zhang, X. Laboratory Investigation of Hydrodynamic and Sand Dune Morphology Changes Under Wave Overwash. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2023, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Z.; Ji, C.; Zhang, Q.-H.; Chen, T.-Q. Numerical Simulations of Coastal Overwash Using A Phase-Averaged Wave—Current—Sediment Transport Model. China Ocean Eng. 2022, 36, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsma, E.W.; Blenkinsopp, C.E.; Martins, K.; Almar, R.; de Almeida, L.P.M. Bore collapse and wave run-up on a sandy beach. Cont. Shelf Res. 2019, 174, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzkin, M.; Moore, L.J.; Ruggiero, P.; Hacker, S.D.; Biel, R.G. The relative influence of dune aspect ratio and beach width on dune erosion as a function of storm duration and surge level. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2021, 9, 1223–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayle, P.M.; Blenkinsopp, C.E.; Martins, K.; Kaminsky, G.M.; Weiner, H.M.; Cottrell, D. Swash-by-swash morphology change on a dynamic cobble berm revetment: High-resolution cross-shore measurements. Coast. Eng. 2023, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Do, K.; Kim, I.; Chang, S. Field Observation and Quasi-3D Numerical Modeling of Coastal Hydrodynamic Response to Submerged Structures. J. Ocean Eng. Technol. 2023, 37, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristodemo, F.; Loarca, A.L.; Besio, G.; Caloiero, T. Detection and quantification of wave trends in the Mediterranean basin. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 2024, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Huang, W.; Jung, S.; Oslon, C.; Yin, K.; Xu, S. Evaluating Vegetation Effects on Wave Attenuation and Dune Erosion during Hurricane. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Salauddin, M.; Abolfathi, S.; Pearson, J. Improved prediction of wave overtopping rates at vertical seawalls with recurve retrofitting. Ocean Eng. 2024, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, S.; Pan, X. Experimental study on wave attenuation and stability of ecological dike system composed of submerged breakwater, mangrove, and dike under storm surge. Appl. Ocean Res. 2024, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Sheng, J.; Zheng, J.; Tao, A. Convergence and divergence of storm waves induced by multi-scale currents: Observations and coupled wave-current modeling. Coast. Eng. 2024, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, B.; Pinho, J.; Barros, J.; Carmo, J.A.D. Optimizing coastal protection: Nature-based engineering for longitudinal drift reversal and erosion reduction. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Huang, W.; Jung, S.; Xu, S.; Vijayan, L. Modeling hurricane wave propagation and attenuation after overtopping sand dunes during storm surge. Ocean Eng. 2024, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keyword | Number of Documents |

Highly Cited Author | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal + Overtopping | --- | --- | 4044 | Kortenhaus, A. |

| + Model | --- | 3432 | Oumeraci, H. | |

| + Numerical | 2394 | Lara, J.L. | ||

| + Physical | 1958 | Altomare, C. | ||

| + Storm | ||||

| 1919 | Kobayashi, N. | |||

| + Defense Structures | --- | 241 | Zanuttigh, B. | |

| + Natural | 118 | Bernatchez, P.; Oumeraci, H.; Sierra, J.P. | ||

| + Artificial | 74 | Zanuttigh, B. | ||

| + Morphological Changes | --- | 237 | Masselink, G. | |

| + Natural | 156 | Masselink, G. | ||

| + Artificial | 67 | Hacker, S.D.; Itzkin, M.; Masselink, G.; Ruggiero, P. | ||

| Numerical Model | N | Applications/References |

|---|---|---|

| SWASH (Simulating WAves till SHore) | 122 | Simulates unsteady, non-hydrostatic coastal flow and transport driven by waves, tides, buoyancy, and wind, including wave transformations, complex flow changes, and density-driven flows in coastal seas, estuaries, lakes, and rivers (https://swash.sourceforge.io/). |

| XBeach (eXtreme Beach behavior) | 64 | Solves short- and long-wave transformations, wave-induced setup, unsteady currents, overwash, inundation, and morphodynamic processes like sediment transport and dune avalanching, incorporating effects of vegetation and hard structures [37]. |

| MIKE 21 | 9 | The model analyzes water flow, currents, wave conditions, and marine processes, accurately predicting water levels, currents, temperature changes, and floods. It excels in managing complex bathymetry and external forces such as wind effects in marine and coastal environments (https://www.dhigroup.com/technologies/mikepoweredbydhi/mike-21-3). |

| COAST2D | 7 | Used to predict hydrodynamics and morphodynamics in nearshore areas. Particularly effective for analyzing coastal defense structures in both laboratory and field studies (https://coast2d.wordpress.com/). |

| FUNWAVE | 4 | The modeling includes surfzone-scale optical properties within a Boussinesq model framework and tsunami wave prediction for coastal inundation on a global/coastal scale and wave propagation on a basin scale (https://fengyanshi.github.io/build/html/index.html). |

| Coastal Intervention | Brief Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial Nourishments (S) | Replacing sand material on beach profile that has been removed by erosion [85]. | Beaches dissipate the wave energy. Easy to monitor impact of longshore drift. | Not solving the problem and more material will be required to replace. |

| Dune Reinforcement (S) | Reinforcement of dune system to maintain the natural function. Solutions include planting vegetation, construction of fences and dikes [86]. | Dissipate the wave energy. Fixed the dune system. |

Need for maintenance if the dune is eroded by overtopping. |

| Attached Structures (H) | Rigid coastal engineering structures, typically adhering longitudinally along the coastline, used to protect against coastal erosion. Solutions include seawalls and rocky revetments [87]. | Dissipates wave energy from high impact waves. Long life span. | It prevents the movement of beach material along the coast and the beach may be lost without replenishment. Costs for construction and maintenance. |

| Detached Structures (H) | Rigid coastal engineering structures used for coastal protection, constructed parallel to the coastline, shielding the inner area from direct wave impact [88]. Detached breakwaters are a typically detached structure. | Dissipates the wave energy. |

Prevents the movement of beach material along the coast and beach may be lost without replenishment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).