Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

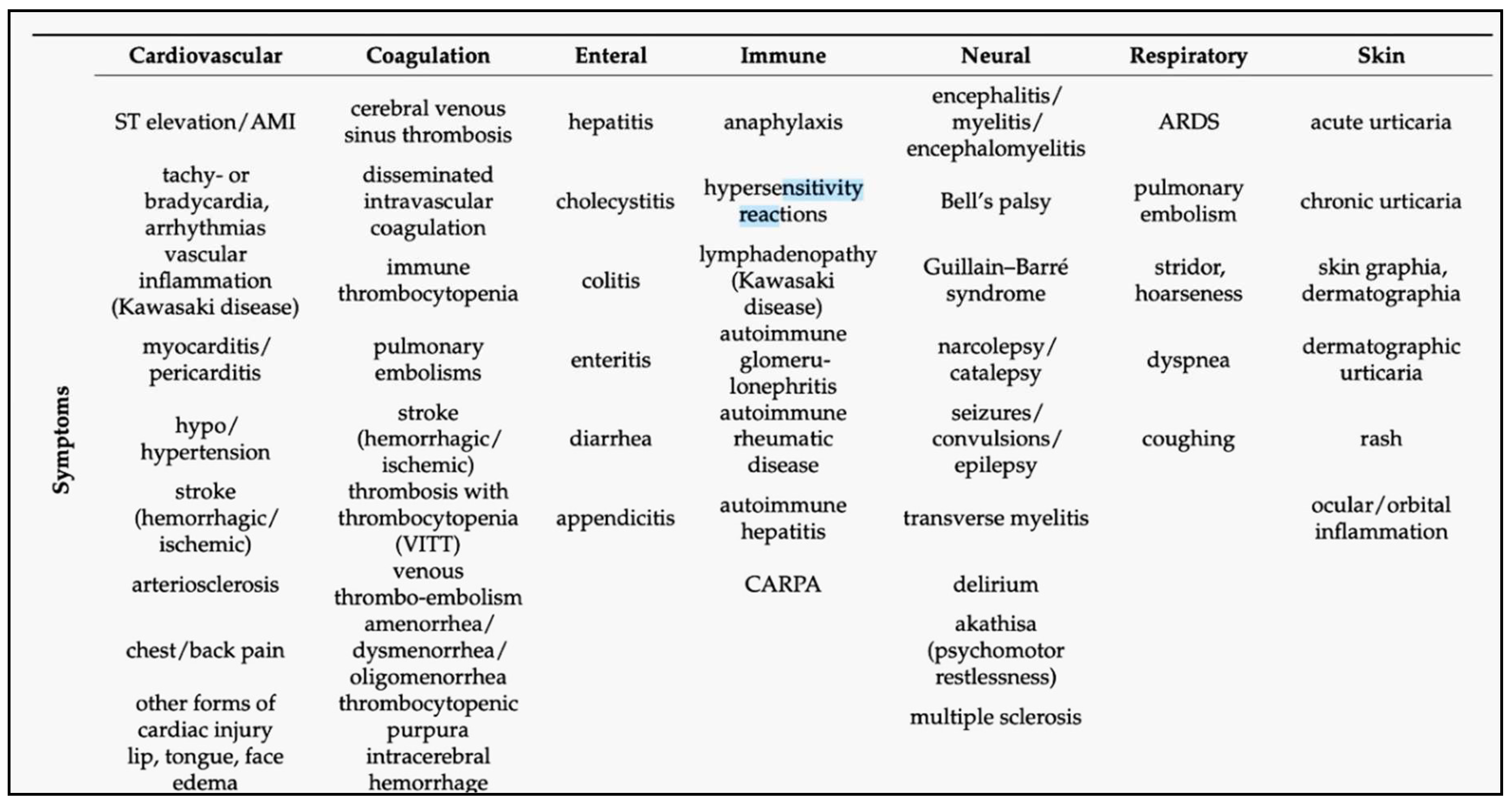

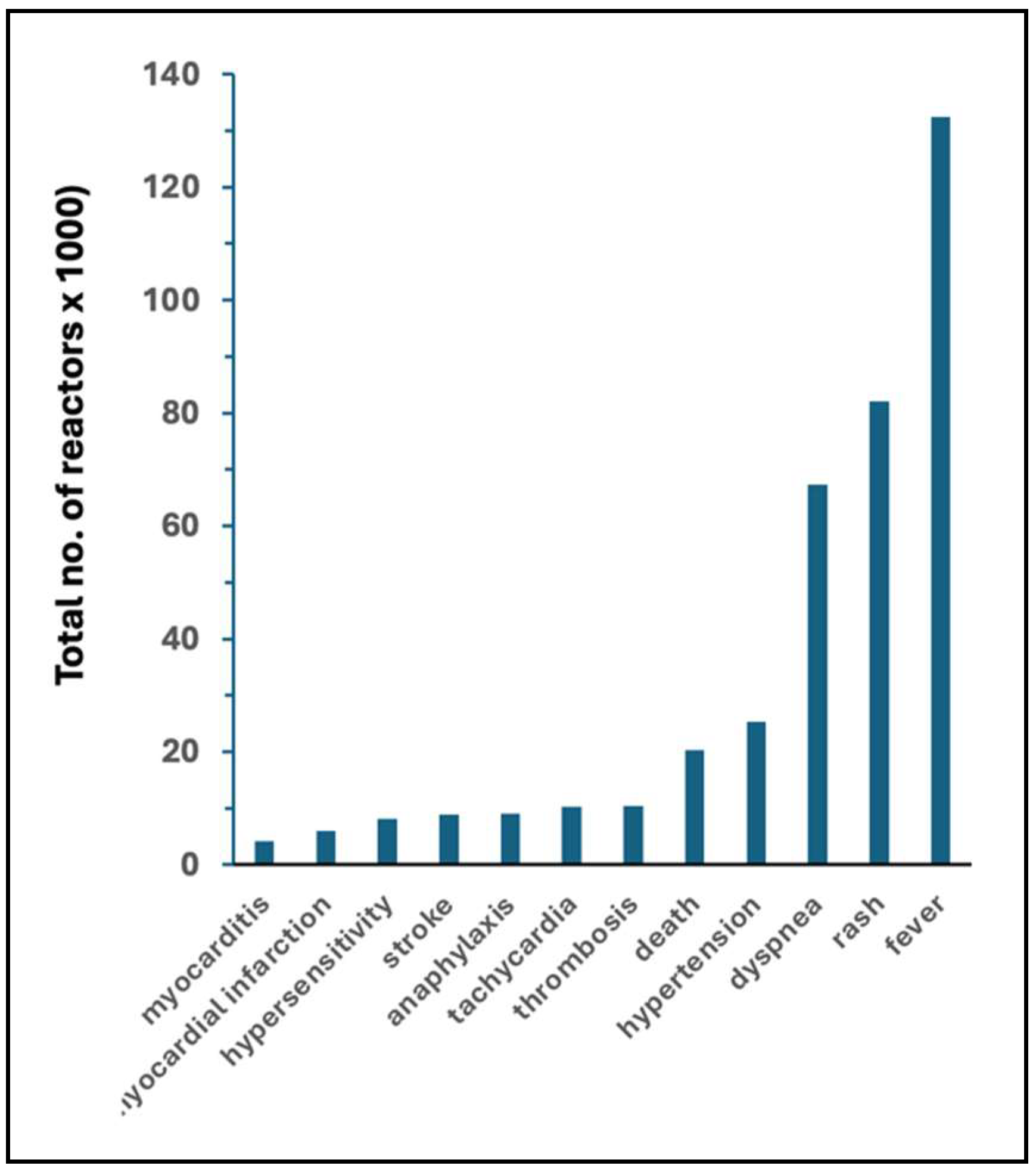

The mRNA- and DNA-based “genetic” COVID-19 vaccines can induce a broad range of adverse events (AEs), with statistics showing significant variation depending on timing and data analysis methods. Focusing only on lipid nanoparticle-enclosed mRNA (mRNA-LNP) vaccines, this review traces the evolution of statistical conclusions on AE prevalence and incidence associated with these vaccines, from initial underestimation of atypical, severe toxicities to recent claims suggesting the possible contribution of Covid-19 vaccinations to the excess deaths observed in many countries over the past few years. Among hundreds of different AEs listed in Pfizer’s pharmacovigilance survey, the present analysis categorizes the main symptoms according to organ systems, nearly all being affected. Using data from the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and a global vaccination dataset, a comparison of the prevalence and incidence rates of AEs induced by genetic versus flu vaccines revealed an average 26-fold increase in AEs with genetic vaccines. The difference is especially pronounced in the case of severe 'Brighton-listed' AEs, which are also observed in COVID-19 and post-COVID conditions. Among these, the increases of incidence rates (AE+/ AE++AE-) relative to flu vaccines, given as x-fold rises, were 1,152x, 455x, 226x, 218x, 162x, 152x; and 131x, for myocarditis, thrombosis, death, myocardial infarction, tachycardia, dyspnea, and hypertension, respectively. The review delineates the concepts that genetic vaccines can be regarded as prophylactic immuno-gene therapies, and that the chronic disabling AEs might be categorized as iatrogenic orphan diseases. A better understanding of the mechanisms of these AEs and diseases is urgently needed to come to consensus regarding the current risk/benefit ratio of genetic COVID-19 vaccines and to ensure the safety of future products based on gene-delivery-based technologies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Essence of mRNA Vaccines and Uniqueness of Their AEs

|

3. Epidemiology of Genetic Vaccine Side Effects: Inconsistent Statistics

| AEs* | Jabs given | AE/M** | % | AE-/AE+*** | Covid/Flu‡ | |

| Comirnaty | 434,821 | 401,685,954 | 1,082 | 0.11 | 924 | 20 |

| Spikevax | 426,714 | 251,852,502 | 1,694 | 0.17 | 590 | 32 |

| Combined mRNA | 861,535 | 653,538,456 | 1,318 | 0.13 | 759 | 25 |

| Jcovden | 54,728 | 18,991,177 | 2,882 | 0.29 | 347 | 54 |

| All genetic | 934,959 | 672,529,633 | 1,390 | 0.14 | 719 | 26 |

| Flu | 18,696 | 352,670,000 | 53 | 0.01 | 18,863 | 1 |

4. Discussion

5. Outlook

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Radmer, A.; Bodurtha, J. Prospects, realities, and safety concerns of gene therapy. Va Med Q 1992, 119(2), 98–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krumholz, H. M.; Wu, Y.; Sawano, M.; Shah, R.; Zhou, T.; Arun, A. S.; Khosla, P.; Kaleem, S.; Vashist, A.; Bhattacharjee, B.; et al. Post-Vaccination Syndrome: A Descriptive Analysis of Reported Symptoms and Patient Experiences After Covid-19 Immunization. medRxiv posted November 10, 10 November. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, Y.; Venkataraman, R. The prevalence of post-COVID-19 vaccination syndrome and quality of life among COVID-19-vaccinated individuals. Vacunas 2024, 25(1), 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokumasu, K.; Fujita-Yamashita, M.; Sunada, N.; Sakurada, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakano, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Otsuka, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Hagiya, H.; et al. Characteristics of Persistent Symptoms Manifested after SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: An Observational Retrospective Study in a Specialized Clinic for Vaccination-Related Adverse Events. Vaccines (Basel), 2023; 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, N.; Tordesillas, L.; Cabanillas, B. Adverse rare events to vaccines for COVID-19: From hypersensitivity reactions to thrombosis and thrombocytopenia. Int Rev Immunol 2022, 41(4), 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, B. Law, B. Priority List of COVID-19 Adverse events of special interest: Quarterly update December 2020. Safety Platform for Emergency Vaccines (SPEAC) 2021, https://brightoncollaboration.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/SO2_D2.1.2_V1.2_COVID-19_AESI-update_V1.3-1.pdf.

- Fraiman, J.; Erviti, J.; Jones, M.; Greenland, S.; Whelan, P.; Kaplan, R. M.; Doshi, P. Serious adverse events of special interest following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in randomized trials in adults. Vaccine 2022, 40(40), 5798–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faksova, K.; Walsh, D.; Jiang, Y.; Griffin, J.; Phillips, A.; Gentile, A.; Kwong, J. C.; Macartney, K.; Naus, M.; Grange, Z.; et al. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine 2024, 42(9), 2200–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, K. M.; Buttery, J. P.; Crawford, N. W.; Cheng, D. R. Letter to the Editor: A comparison of post-COVID vaccine myocarditis classification using the Brighton Collaboration criteria versus (United States) Centers for Disease Control criteria: an update. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2024, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitan, B.; Hadler, S. C.; Hurst, W.; Izurieta, H. S.; Smith, E. R.; Baker, N. L.; Bauchau, V.; Chandler, R.; Chen, R. T.; Craig, D.; et al. The Brighton collaboration standardized module for vaccine benefit-risk assessment. Vaccine 2024, 42(4), 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostert, S.; Hoogland, M.; Huibers, M.; Kaspers, G. Mostert, S.; Hoogland, M.; Huibers, M.; Kaspers, G. Excess mortality across countries in the Western World since the COVID-19 pandemic: ‘Our World in Data’ estimates of January 2020 to December 2022. . BMJ Public Health 2024, 2:e000282. [CrossRef]

- Rancourt, D. G.; Hickey, J.; Linard, C. Rancourt, D. G.; Hickey, J.; Linard, C. Spatiotemporal variation of excess all-cause mortality in the world (125 countries) during the Covid period 2020-2023 regarding socio-economic factors and public-health and medical interventions. https://correlation-canada.org/covid-excess-mortality-125-countries/ 2024, (Report I 19 July 2024).

- Oueijan, R. I.; Hill, O. R.; Ahiawodzi, P. D.; Fasinu, P. S.; Thompson, D. K. Oueijan, R. I.; Hill, O. R.; Ahiawodzi, P. D.; Fasinu, P. S.; Thompson, D. K. Rare Heterogeneous Adverse Events Associated with mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review. Medicines (Basel) 2022, 9 (8). [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Li, N.; Tang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Zeng, S.; Chen, J. Development and evaluation of vaccination strategies for addressing the continuous evolution SARS-CoV-2 based on recombinant trimeric protein technology: Potential for cross-neutralizing activity and broad coronavirus response. Heliyon 2024, 10(14), e34492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F. P.; Thomas, S. J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J. L.; Perez Marc, G.; Moreira, E. D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020, 383(27), 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Safety-Pfizer. Cumulative Analysis of post-authorization adverse event reports of PF-07302048 (BNT162B2) received through 28-Feb-2021. https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/html-attachments/h_bus_2022a_03032022_013716_pm_committee_summary/Attachment%20C.pdf FDA-CBER-2021-5683-0000057 (accessed Nov 27, 2024).

- Autoimmune Registry Inc, https://diseases.autoimmuneregistry.org/. 2024.

- Thomas, S. J.; Moreira, E. D., Jr.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J. L.; Perez Marc, G.; Polack, F. P.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine through 6 Months. N Engl J Med 2021, 385(19), 1761–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VAERS data https://vaers.hhs.gov/docs/VAERSDataUseGuide_en_September2021.pdf 2021.

- VAERS IDs. https://vaers.hhs.gov/data/datasets.html 2023.

- Lazarus, R.; Klompas, M. Lazarus, R.; Klompas, M. Electronic Support for Public Health–Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (ESP:VAERS). https://digital.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/docs/publication/r18hs017045-lazarus-final-report-2011.pdf: https://digital.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/docs/publication/r18hs017045-lazarus-final-report-2011.pdf, 2010; Vol.https://digital.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/docs/publication/r18hs017045-lazarus-final-report-2011.pdf, pp 1367-1393.

- Wang, S.; Zhang, K.; Du, J. PubMed captures more fine-grained bibliographic data on scientific commentary than Web of Science: a comparative analysis. BMJ Health Care Inform, 2024; 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domen, J.; Abrams, S.; Digregorio, M.; Van Ngoc, P.; Duysburgh, E.; Scholtes, B.; Coenen, S. Predictors of moderate-to-severe side-effects following COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccination: a prospective cohort study among primary health care providers in Belgium. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24(1), 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Shoaibi, A.; Feng, Y.; Lloyd, P. C.; Wong, H. L.; Smith, E. R.; Amend, K. L.; Kline, A.; Beachler, D. C.; Gruber, J. F.; et al. Safety of Ancestral Monovalent BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and NVX-CoV2373 COVID-19 Vaccines in US Children Aged 6 Months to 17 Years. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7(4), e248192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soe, P.; Wong, H.; Naus, M.; Muller, M. P.; Vanderkooi, O. G.; Kellner, J. D.; Top, K. A.; Sadarangani, M.; Isenor, J. E.; Marty, K.; et al. mRNA COVID-19 vaccine safety among older adults from the Canadian National Vaccine Safety Network. Vaccine 2024, 42(18), 3819–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, N.; Ratzon, R.; Hazan, I.; Zimmerman, D. R.; Singer, S. R.; Wasser, J.; Dweck, T.; Alroy-Preis, S. Multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children and the BNT162b2 vaccine: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Pediatr 2024, 183(8), 3319–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemaitelly, H.; Akhtar, N.; Jerdi, S. A.; Kamran, S.; Joseph, S.; Morgan, D.; Uy, R.; Abid, F. B.; Al-Khal, A.; Bertollini, R.; et al. Association between COVID-19 vaccination and stroke: a nationwide case-control study in Qatar. Int J Infect Dis 2024, 145, 107095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, M. N.; Seneff, S.; Wolfinger, R.; Rose, J.; Denhaerynck, K.; Kirsch, S.; McCullough, P. A. COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines: Lessons Learned from the Registrational Trials and Global Vaccination Campaign. Cureus 2024, 16(1), e52876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. H.; Chen, T. A.; Chiang, P. H.; Hsieh, A. R.; Wu, B. J.; Chen, P. Y.; Lin, K. C.; Tsai, Z. S.; Lin, M. H.; Chen, T. J.; et al. Incidence and Nature of Short-Term Adverse Events following COVID-19 Second Boosters: Insights from Taiwan’s Universal Vaccination Strategy. Vaccines (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Kamat, I.; Hotez, P. J. Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. Circulation 2021, 144(6), 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B. Shedding Light on Mechanisms of Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. Circulation 2023, 147(11), 877–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patone, M.; Mei, X. W.; Handunnetthi, L.; Dixon, S.; Zaccardi, F.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Watkinson, P.; Khunti, K.; Harnden, A.; Coupland, C. A. C.; et al. Risk of Myocarditis After Sequential Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine and SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Age and Sex. Circulation 2022, 146(10), 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Hur, K.; Salone, C.; Huang, N.; Burk, M.; Pandey, L.; Thakkar, B.; Donahue, M.; Cunningham, F. Incidence Rates and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Confirmed Myocarditis or Pericarditis Following COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination: Experience of the Veterans Health Administration Through 9 October 2022. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10(7), ofad268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungmunpuntipantip, R.; Wiwanitkit, V. Mungmunpuntipantip, R.; Wiwanitkit, V. Cardiac inflammation associated with COVID-19 mRNA vaccination and previous myocarditis. Minerva Cardiol Angiol 2023, 2023 Aug 2. [CrossRef]

- Schroth, D.; Garg, R.; Bocova, X.; Hansmann, J.; Haass, M.; Yan, A.; Fernando, C.; Chacko, B.; Oikonomou, A.; White, J.; et al. Predictors of persistent symptoms after mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-related myocarditis (myovacc registry). Front Cardiovasc Med 2023, 10, 1204232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes-Vazquez, J. G.; Rubio-Infante, N.; Lopez-de la Garza, H.; Brunck, M. E. G.; Guajardo-Lozano, J. A.; Ramos, M. R.; Vazquez-Garza, E.; Torre-Amione, G.; Garcia-Rivas, G.; Jerjes-Sanchez, C. Soluble factors in COVID-19 mRNA vaccine-induced myocarditis causes cardiomyoblast hypertrophy and cell injury: a case report. Virol J 2023, 20(1), 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakahara, T.; Iwabuchi, Y.; Miyazawa, R.; Tonda, K.; Shiga, T.; Strauss, H. W.; Antoniades, C.; Narula, J.; Jinzaki, M. Assessment of Myocardial (18)F-FDG Uptake at PET/CT in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-vaccinated and Nonvaccinated Patients. Radiology 2023, 308(3), e230743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeni, M. COVID-19 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine induced myocarditis with left ventricular thrombus in a young male. Acta Cardiol 2023, 78(4), 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Vu, S.; Bertrand, M.; Botton, J.; Jabagi, M. J.; Drouin, J.; Semenzato, L.; Weill, A.; Dray-Spira, R.; Zureik, M. Risk of Guillain-Barre Syndrome Following COVID-19 Vaccines: A Nationwide Self-Controlled Case Series Study. Neurology 2023, 101(21), e2094–e2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kwon, D.; Park, S.; Park, S. R.; Chung, D.; Ha, J. Temporal association between the age-specific incidence of Guillain-Barre syndrome and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in Republic of Korea: a nationwide time-series correlation study. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 2023, 14(3), 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, Y. M.; Murthy, J. M.; Osman, S.; Jaiswal, S. K.; Gattu, A. K.; Pidaparthi, L.; Boorgu, S. K.; Chavan, R.; Ramakrishnan, B.; Yeduguri, S. R. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: how is it different? a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Clin Exp Vaccine Res 2023, 12(2), 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, H. A.; Shirah, B. H.; Albeladi, Y. K.; Albeladi, R. K. Guillain-Barre Syndrome Following the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2023, 32(2), 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunjimi, O. B.; Tsalamandris, G.; Paladini, A.; Varrassi, G.; Zis, P. Guillain-Barre Syndrome Induced by Vaccination Against COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2023, 15(4), e37578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Park, S.; Kang, H.; Kyung, T.; Kim, N.; Kim, D. K.; Kim, H.; Bae, K.; Song, M. C.; Lee, K. J.; et al. Real-world data on the incidence and risk of Guillain-Barre syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a prospective surveillance study. Sci Rep 2023, 13(1), 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abara, W. E.; Gee, J.; Marquez, P.; Woo, J.; Myers, T. R.; DeSantis, A.; Baumblatt, J. A. G.; Woo, E. J.; Thompson, D.; Nair, N.; et al. Reports of Guillain-Barre Syndrome After COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6(2), e2253845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, A.; Kraemer, M. A neurologist’s rhombencephalitis after comirnaty vaccination. A change of perspective. A change of perspective. Neurol Res Pract 2021, 3(1), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, R.; Askari, N. A review of neurological side effects of COVID-19 vaccination. Eur J Med Res 2023, 28(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R. K.; Paliwal, V. K. Spectrum of neurological complications following COVID-19 vaccination. Neurol Sci 2022, 43(1), 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J. L.; Schultze, A.; Tazare, J.; Tamborska, A.; Singh, B.; Donegan, K.; Stowe, J.; Morton, C. E.; Hulme, W. J.; Curtis, H. J.; et al. Safety of COVID-19 vaccination and acute neurological events: A self-controlled case series in England using the OpenSAFELY platform. Vaccine 2022, 40(32), 4479–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopatynsky-Reyes, E. Z.; Acosta-Lazo, H.; Ulloa-Gutierrez, R.; Avila-Aguero, M. L.; Chacon-Cruz, E. BCG Scar Local Skin Inflammation as a Novel Reaction Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Two International Healthcare Workers. Cureus 2021, 13(4), e14453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Fredj, N.; Chahed, F.; Ben-Fadhel, N.; Mansour, K.; Ben-Romdhane, H.; Mabrouk, R. S. E.; Chadli, Z.; Ghedira, D.; Belhadjali, H.; Chaabane, A.; et al. Case series of chronic spontaneous urticaria following COVID-19 vaccines: an unusual skin manifestation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2022, 78(12), 1959–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieco, T.; Ambrosio, L.; Trovato, F.; Vitiello, M.; Demofonte, I.; Fanto, M.; Paolino, G.; Pellacani, G. Effects of Vaccination against COVID-19 in Chronic Spontaneous and Inducible Urticaria (CSU/CIU) Patients: A Monocentric Study. J Clin Med. [CrossRef]

- Magen, E.; Yakov, A.; Green, I.; Israel, A.; Vinker, S.; Merzon, E. Chronic spontaneous urticaria after BNT162b2 mRNA (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Allergy Asthma Proc 2022, 43(1), 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root-Bernstein, R. COVID-19 coagulopathies: Human blood proteins mimic SARS-CoV-2 virus, vaccine proteins and bacterial co-infections inducing autoimmunity: Combinations of bacteria and SARS-CoV-2 synergize to induce autoantibodies targeting cardiolipin, cardiolipin-binding proteins, platelet factor 4, prothrombin, and coagulation factors. Bioessays 2021, 43(12), e2100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, M.; Canzano, P.; Valle, P. D.; Becchetti, A.; Conti, M.; Alberti, M.; Galotta, A.; Biondi, M. L.; Lonati, P. A.; Veglia, F.; et al. Head-to-head comparison of four COVID-19 vaccines on platelet activation, coagulation and inflammation. The TREASURE study. Thromb Res 2023, 223, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, S. R.; Sogaard, O. S.; Tolstrup, M.; Staerke, N. B.; Lundgren, J.; Ostergaard, L.; Hvas, A. M. Inflammation and Platelet Activation After COVID-19 Vaccines - Possible Mechanisms Behind Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 779453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorente, E. Idiopathic Ipsilateral External Jugular Vein Thrombophlebitis After Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Vaccination. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021, 217(3), 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, T.; Tong, J. Y.; Patel, S.; Khong, J. J.; Selva, D. Orbital inflammation following COVID-19 vaccination: A case series and literature review. Int Ophthalmol 2023, 43(9), 3391–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ho, M.; Mak, A.; Lai, F.; Brelen, M.; Chong, K.; Young, A. Intraocular inflammation following COVID-19 vaccination: the clinical presentations. Int Ophthalmol 2023, 43(8), 2971–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasaka, Y.; Hasegawa, E.; Keino, H.; Usui, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kaburaki, T.; Iwata, D.; Takeuchi, M.; Kusuhara, S.; et al. A multicenter study of ocular inflammation after COVID-19 vaccination. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2023, 67(1), 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Raventos, B.; Roel, E.; Pistillo, A.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; Delmestri, A.; Reyes, C.; Strauss, V.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Burn, E.; et al. Association between covid-19 vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 infection, and risk of immune mediated neurological events: population based cohort and self-controlled case series analysis. BMJ 2022, 376, e068373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebeni, J.; Storm, G.; Ljubimova, J. Y.; Castells, M.; Phillips, E. J.; Turjeman, K.; Barenholz, Y.; Crommelin, D. J. A.; Dobrovolskaia, M. A. Applying lessons learned from nanomedicines to understand rare hypersensitivity reactions to mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Nat Nanotechnol 2022, 17(4), 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dezsi, L.; Meszaros, T.; Kozma, G.; M, H. V.; Olah, C. Z.; Szabo, M.; Patko, Z.; Fulop, T.; Hennies, M.; Szebeni, M.; et al. A naturally hypersensitive porcine model may help understand the mechanism of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine-induced rare (pseudo) allergic reactions: complement activation as a possible contributing factor. Geroscience 2022, 44(2), 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozma, G. T.; Meszaros, T.; Berenyi, P.; Facsko, R.; Patko, Z.; Olah, C. Z.; Nagy, A.; Fulop, T. G.; Glatter, K. A.; Radovits, T.; Merkely, B.; Szebeni, J. Role of anti-polyethylene glycol (PEG) antibodies in the allergic reactions to PEG-containing Covid-19 vaccines: Evidence for immunogenicity of PEG. Vaccine 2023, 41(31), 4561–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barta, B. A.; Radovits, T.; Dobos, A. B.; Tibor Kozma, G.; Meszaros, T.; Berenyi, P.; Facsko, R.; Fulop, T.; Merkely, B.; Szebeni, J. Comirnaty-induced cardiopulmonary distress and other symptoms of complement-mediated pseudo-anaphylaxis in a hyperimmune pig model: Causal role of anti-PEG antibodies. Vaccine X 2024, 19, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M. ; X., L.; Chen, X.; Li, Q. Insights into new-onset autoimmune diseases after COVID-19 vaccination Autoimmunity Reviews 2023, 22 (7), 103340.

- Vojdani, A.; Kharrazian, D. Potential antigenic cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and human tissue with a possible link to an increase in autoimmune diseases. Clin Immunol 2020, 217, 108480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M.; Hasell, J.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Rodes-Guirao, L. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat Hum Behav 2021, 5(7), 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covid-vaccine-doses-by-manufacturer. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-vaccine-doses-by-manufacturer?time=2021-01-12..latest&country=European+Union~USA 2024.

- Paul Erlich Institute, Safety report. https://www.pei.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/newsroom-en/dossiers/safety-reports/safety-report-27-december-2020-31-march-2022.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=8 2022.

- Hugli, T. E.; Stimler, N. P.; Gerard, C.; Moon, K. E. Possible role of serum anaphylatoxins in hypersensitivity reactions. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol 1981, 66 Suppl 1, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimler-Gerard, N. P. Stimler-Gerard, N. P. Role of the complement anaphylatoxins in inflammation and hypersensitivity reactions in the lung. Surv Synth Pathol Res 1985, 4 (5-6), 423-442.

- Vogt, W. Anaphylatoxins: possible roles in disease. Complement 1986, 3(3), 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E. L. Modulation of the immune response by anaphylatoxins. Complement 1986, 3(3), 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marceau, F.; Lundberg, C.; Hugli, T. E. Effects of anaphylatoxins on circulation. Immunopharmacol 1987, 14, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebeni, J.; Baranyi, L.; Savay, S.; Bodo, M.; Milosevits, J.; Alving, C. R.; Bunger, R. Complement activation-related cardiac anaphylaxis in pigs: role of C5a anaphylatoxin and adenosine in liposome-induced abnormalities in ECG and heart function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006, 290(3), H1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebeni, J.; Bawa, R. Human Clinical Relevance of the Porcine Model of Pseudoallergic Infusion Reactions. Biomedicines. [CrossRef]

- Bakos, T.; Meszaros, T.; Kozma, G. T.; Berenyi, P.; Facsko, R.; Farkas, H.; Dezsi, L.; Heirman, C.; de Koker, S.; Schiffelers, R.; et al. mRNA-LNP COVID-19 Vaccine Lipids Induce Complement Activation and Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines: Mechanisms, Effects of Complement Inhibitors, and Relevance to Adverse Reactions. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Alosaimi, B.; Mubarak, A.; Hamed, M. E.; Almutairi, A. Z.; Alrashed, A. A.; AlJuryyan, A.; Enani, M.; Alenzi, F. Q.; Alturaiki, W. Complement Anaphylatoxins and Inflammatory Cytokines as Prognostic Markers for COVID-19 Severity and In-Hospital Mortality. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 668725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E. H. T.; van Amstel, R. B. E.; de Boer, V. V.; van Vught, L. A.; de Bruin, S.; Brouwer, M. C.; Vlaar, A. P. J.; van de Beek, D. Complement activation in COVID-19 and targeted therapeutic options: A scoping review. Blood Rev 2023, 57, 100995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siggins, M. K.; Davies, K.; Fellows, R.; Thwaites, R. S.; Baillie, J. K.; Semple, M. G.; Openshaw, P. J. M.; Zelek, W. M.; Harris, C. L.; Morgan, B. P.; et al. Alternative pathway dysregulation in tissues drives sustained complement activation and predicts outcome across the disease course in COVID-19. Immunology 2023, 168(3), 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, P. L.; Croci, S.; Lonati, P. A.; Pregnolato, F.; Spaggiari, L.; Besutti, G.; Bonacini, M.; Ferrigno, I.; Rossi, A.; Hetland, G.; et al. Complement activation predicts negative outcomes in COVID-19: The experience from Northen Italian patients. Autoimmun Rev 2023, 22(1), 103232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbari, E. P.; Jakobs, K.; Puccini, M.; Reinshagen, L.; Friebel, J.; Haghikia, A.; Krankel, N.; Landmesser, U.; Rauch-Krohnert, U. The Role of NETosis and Complement Activation in COVID-19-Associated Coagulopathies. Biomedicines. [CrossRef]

- Ardalan, M.; Moslemi, M.; Pakmehr, A.; Vahed, S. Z.; Khalaji, A.; Moslemi, H.; Vahedi, A. TTP-like syndrome and its relationship with complement activation in critically ill patients with COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon 2023, 9(6), e17370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggeri, T.; De Wit, Y.; Scharz, N.; van Mierlo, G.; Angelillo-Scherrer, A.; Brodard, J.; Schefold, J.; Hirzel, C.; Jongerius, I.; Zeerleder, S. Immunothrombosis and complement activation contribute to disease severity and adverse outcome in COVID-19. J Innate Immun 2023. [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A. EI Briefing Note 2020:4 Selected Government Definitions of Orphan or Rare Diseases Selected Government Definitions of Orphan or Rare Diseases”. Knowledge Ecology International. R, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fermaglich, L. J.; Miller, K. L. A comprehensive study of the rare diseases and conditions targeted by orphan drug designations and approvals over the forty years of the Orphan Drug Act. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2023, 18(1), 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, M. The Orphan Drug Act: An Appropriate Approval Pathway for Treatments of Rare Diseases? Hosp Pharm 2019, 54(5), 283–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M. G.; Pawlik, T. M.; Fader, A. N.; Esnaola, N. F.; Makary, M. A. The Orphan Drug Act: Restoring the Mission to Rare Diseases. Am J Clin Oncol 2016, 39(2), 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, T. I. The Orphan Drug Act. Prog Clin Biol Res 1983, 127, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, PEI. https://www.pei.de/DE/home/home-node.html 2024.

- Ryan, F. J.; Norton, T. S.; McCafferty, C.; Blake, S. J.; Stevens, N. E.; James, J.; Eden, G. L.; Tee, Y. C.; Benson, S. C.; Masavuli, M. G.; et al. A systems immunology study comparing innate and adaptive immune responses in adults to COVID-19 mRNA and adenovirus vectored vaccines. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4(3), 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Xu, Z.; Smith, J. S.; Hofherr, S. E.; Barry, M. A.; Byrnes, A. P. Adenovirus activates complement by distinctly different mechanisms in vitro and in vivo: indirect complement activation by virions in vivo. J Virol 2009, 83(11), 5648–5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Vaisanen, E.; Kolehmainen, P.; Huttunen, M.; Yla-Herttuala, S.; Meri, S.; Osterlund, P.; Julkunen, I. COVID-19 adenovirus vector vaccine induces higher interferon and pro-inflammatory responses than mRNA vaccines in human PBMCs, macrophages and moDCs. Vaccine 2023, 41(26), 3813–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineberg, H. V. Swine flu of 1976: lessons from the past. An interview with Dr Harvey V Fineberg. An interview with Dr Harvey V Fineberg. Bull World Health Organ 2009, 87(6), 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Tuyishime, S.; Muramatsu, H.; Kariko, K.; Mui, B. L.; Tam, Y. K.; Madden, T. D.; Hope, M. J.; Weissman, D. Expression kinetics of nucleoside-modified mRNA delivered in lipid nanoparticles to mice by various routes. J Control Release 2015, 217, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonclinical Evaluation Report: BNT162b2 [mRNA] COVID-19 vaccine (COMIRNATYTM). https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/foi-2389-06.pdf 2021.

- Pateev, I.; Seregina, K.; Ivanov, R.; Reshetnikov, V. Biodistribution of RNA Vaccines and of Their Products: Evidence from Human and Animal Studies. Biomedicines. [CrossRef]

- Kyte, J. A.; Gaudernack, G. Immuno-gene therapy of cancer with tumour-mRNA transfected dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2006, 55(11), 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfizer; Biontech. COMIRNATY ORIGINAL/OMICRON BA.4-5 DISPERSION FOR INJECTION. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=19823 2023.

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M. J.; Naradikian, M. S.; Parkhouse, K.; Cain, D. W.; Jones, L.; Moody, M. A.; Verkerke, H. P.; Myles, A.; Willis, E.; et al. Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines induce potent T follicular helper and germinal center B cell responses. J Exp Med 2018, 215(6), 1571–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, K.; Castano, D.; Gomez Atria, D.; Oguin, T. H., 3rd; Wang, S.; Manzoni, T. B.; Muramatsu, H.; Hogan, M. J.; Amanat, F.; Cherubin, P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccines Foster Potent Antigen-Specific Germinal Center Responses Associated with Neutralizing Antibody Generation. Immunity, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y. M.; Ferrari, M.; Lynch, N. J.; Yaseen, S.; Dudler, T.; Gragerov, S.; Demopulos, G.; Heeney, J. L.; Schwaeble, W. J. Lectin Pathway Mediates Complement Activation by SARS-CoV-2 Proteins. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 714511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alameh, M. G.; Tombacz, I.; Bettini, E.; Lederer, K.; Sittplangkoon, C.; Wilmore, J. R.; Gaudette, B. T.; Soliman, O. Y.; Pine, M.; Hicks, P.; et al. Lipid nanoparticles enhance the efficacy of mRNA and protein subunit vaccines by inducing robust T follicular helper cell and humoral responses. Immunity, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perico, L.; Morigi, M.; Galbusera, M.; Pezzotta, A.; Gastoldi, S.; Imberti, B.; Perna, A.; Ruggenenti, P.; Donadelli, R.; Benigni, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein 1 Activates Microvascular Endothelial Cells and Complement System Leading to Platelet Aggregation. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 827146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanzenbacher, J.; Kohl, J.; Karsten, C. M. Anaphylatoxins spark the flame in early autoimmunity. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 958392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alameh, M. G.; Semon, A.; Bayard, N. U.; Pan, Y. G.; Dwivedi, G.; Knox, J.; Glover, R. C.; Rangel, P. C.; Tanes, C.; Bittinger, K.; et al. A multivalent mRNA-LNP vaccine protects against Clostridioides difficile infection. Science 2024, 386(6717), 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Hoorn, D.; Aitha, A.; Breier, D.; Peer, D. The immunostimulatory nature of mRNA lipid nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2024, 205, 115175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, X.; Cao, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, B.; et al. Management of cytokine release syndrome related to CAR-T cell therapy. Front Med 2019, 13(5), 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalabi, H.; Gust, J.; Taraseviciute, A.; Wolters, P. L.; Leahy, A. B.; Sandi, C.; Laetsch, T. W.; Wiener, L.; Gardner, R. A.; Nussenblatt, V.; et al. Beyond the storm - subacute toxicities and late effects in children receiving CAR T cells. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18(6), 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, M.; Usmani, N.; Krajinovic, M.; Bittencourt, H. Cytokine release syndrome after CAR T-cell therapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children and young adolescents: storms make trees take deeper roots. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2024, 25(11), 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vessillier, S.; Eastwood, D.; Fox, B.; Sathish, J.; Sethu, S.; Dougall, T.; Thorpe, S. J.; Thorpe, R.; Stebbings, R. Cytokine release assays for the prediction of therapeutic mAb safety in first-in man trials--Whole blood cytokine release assays are poorly predictive for TGN1412 cytokine storm. J Immunol Methods 2015, 424, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitsidou, M.; Kueberuwa, G.; Schutt, A.; Gilham, D. E. CAR T-cell therapy: toxicity and the relevance of preclinical models. Immunotherapy 2015, 7(5), 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrsin, D.; Chuvpilo, S.; Matskevich, A.; Nemenov, D.; Romer, P. S.; Tabares, P.; Hunig, T. From TGN1412 to TAB08: the return of CD28 superagonist therapy to clinical development for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016, 34 (4 Suppl 98), 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hunig, T. The rise and fall of the CD28 superagonist TGN1412 and its return as TAB08: a personal account. FEBS J 2016, 283(18), 3325–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebeni, J. Side effects of mRNA-containing genetic Covid vaccines from an immunologist’s perspective: Theories from causes of anaphylactic reactions to multicausal PAN toxicity In The future is in our hand (in Hungarian), Noll-Szatmari, E. Ed.; Prometheus Kiado, 2024. ISBN978-615-82412-9-8.

- Barbier, A. J.; Jiang, A. Y.; Zhang, P.; Wooster, R.; Anderson, D. G. The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40(6), 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.; Goswami, J.; Baqui, A. H.; Doreski, P. A.; Perez-Marc, G.; Zaman, K.; Monroy, J.; Duncan, C. J. A.; Ujiie, M.; Ramet, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of an mRNA-Based RSV PreF Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med 2023, 389(24), 2233–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Flu vaccines | mRNA vaccines | Fold increase | ||||

| AE | AE/M | AE | AE/M | AE | AE/M | |

| fever | 4294 | 7.9 | 132,447 | 201.70 | 31 | 26 |

| rash | 1118 | 2.06 | 82,113 | 125.05 | 73 | 61 |

| dyspnea | 622 | 1.14 | 67355 | 102.57 | 204 | 152 |

| hypertension | 160 | 0.29 | 25,292 | 38.52 | 158 | 131 |

| death | 74 | 0.14 | 20,227 | 30.8 | 273 | 226 |

| thrombosis | 19 | 0.03 | 10,439 | 15.9 | 549 | 455 |

| tachycardia | 52 | 0.1 | 10,205 | 15.54 | 196 | 162 |

| anaphylaxis | 117 | 0.22 | 9,094 | 13.85 | 78 | 64 |

| stroke | 280 | 0.52 | 8,939 | 13.61 | 32 | 26 |

| hypersensitivity | 122 | 0.22 | 8,153 | 12.42 | 67 | 55 |

| myocardial infarction | 23 | 0.04 | 6,067 | 9.24 | 264 | 218 |

| myocarditis | 3 | 0.01 | 4,176 | 6.36 | 1392 | 1,152 |

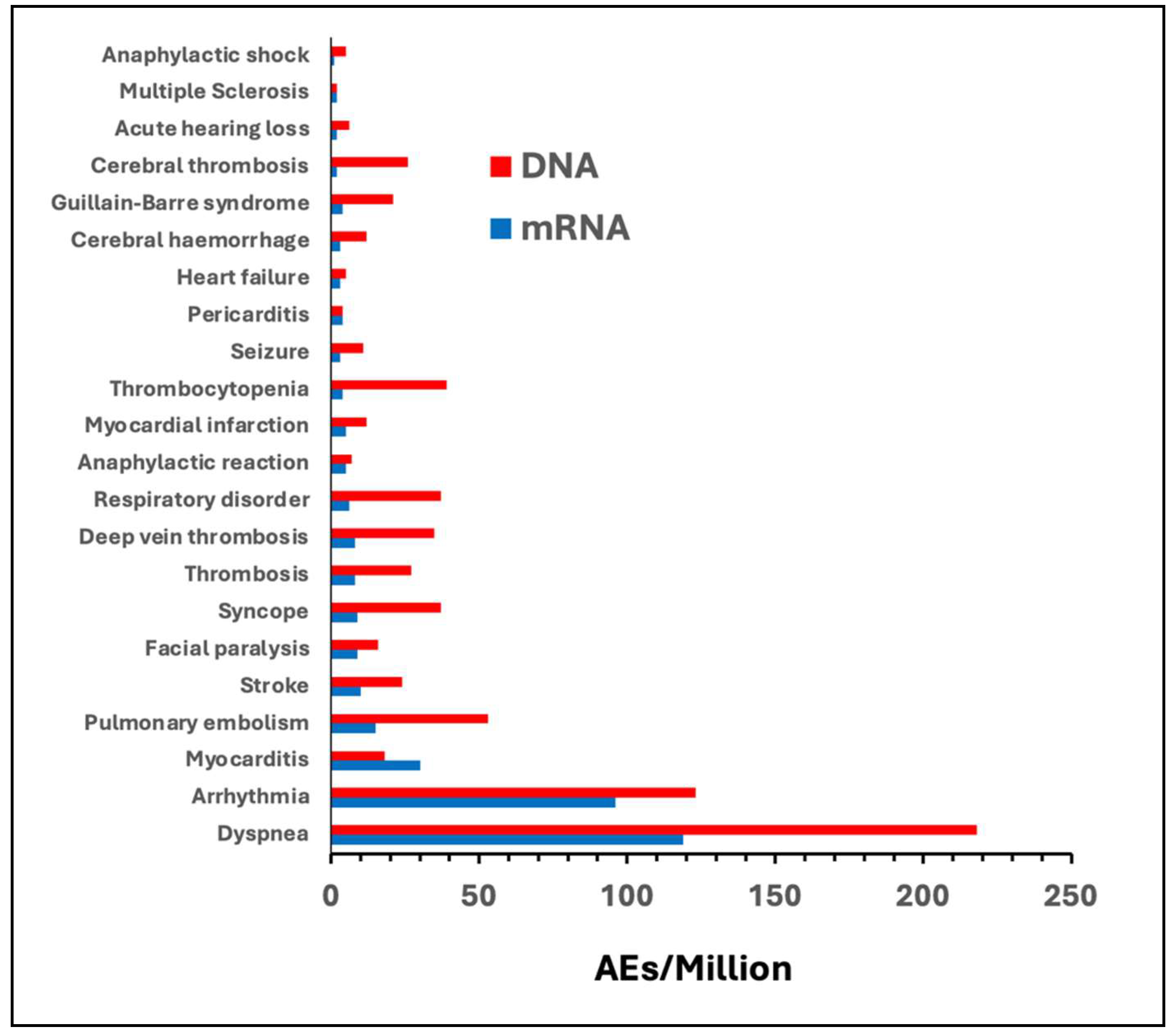

| AE of special interest | AEs/Million | |||||

| Comirnaty | Spikevax | all mRNA | Vaxzevria | Jcovden | all DNA | |

| Dyspnea | 55 | 64 | 119 | 110 | 108 | 218 |

| Arrhythmia | 46 | 50 | 96 | 57 | 66 | 123 |

| Myocarditis | 14 | 16 | 30 | 6 | 12 | 18 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 8 | 7 | 15 | 33 | 20 | 53 |

| Stroke | 6 | 4 | 10 | 15 | 9 | 24 |

| Facial paralysis | 5 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| Syncope | 5 | 4 | 9 | 25 | 12 | 37 |

| Thrombosis | 4 | 4 | 8 | 19 | 8 | 27 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 4 | 4 | 8 | 27 | 8 | 35 |

| Respiratory disorder | 3 | 3 | 6 | 33 | 4 | 37 |

| Anaphylactic reaction | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 | 1 | 4 | 32 | 7 | 39 |

| Seizure | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Pericarditis | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Heart failure | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Cerebral thrombosis | 1 | 1 | 2 | 20 | 6 | 26 |

| Acute hearing loss | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Anaphylactic shock | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).