4.1. Effect of S Fertilisation on Yield, Ingredients and Other Characteristics of the Plant Species

In the lucerne-clover-grass trials, the S fertilisation treatments in many regions in Germany increased both the S concentrations and the yields of the forage crops [

20,

22,

34,

35]. The S concentration and thus also the S removal increased in both parts of the legume-grass mixtures [

28]. According to the previous evaluations of the individual grain legume trials, including the pea-cereal mixtures, hardly any significant yield effects were observed as a result of the S fertilisation measures. Minor increases were only achieved in the S concentrations of the harvested materials [

36,

37,

38,

39].

Field bean and pea accumulated S mainly in the grain, lupine in the straw. The S concentration in young plants depended on the demand. The calculated S efficiency of the fertilisation was between 3–9% for field beans. In the lupine trials, S efficiencies of 4–7% and for peas between 5–8% were determined. According to the compiled fertilisation trials by Gruber et al. [

22], only minor to no yield effects on grain and straw of grain legumes were recorded, although the S concentrations also increased. Winter forms of grain legumes could be characterised by a higher S demand, as isolated trials with peas, for example, have shown. The cereals tested, especially winter wheat, also showed only minor yield effects as a result of S fertilisation. Direct fertilisation of cereals can then often be omitted [

20,

22,

40]. In durum wheat, S soil fertilisation increased the DM yield particularly when coupled with organic fertilisation. In contrast, the quality of the grains was not changed [

41].

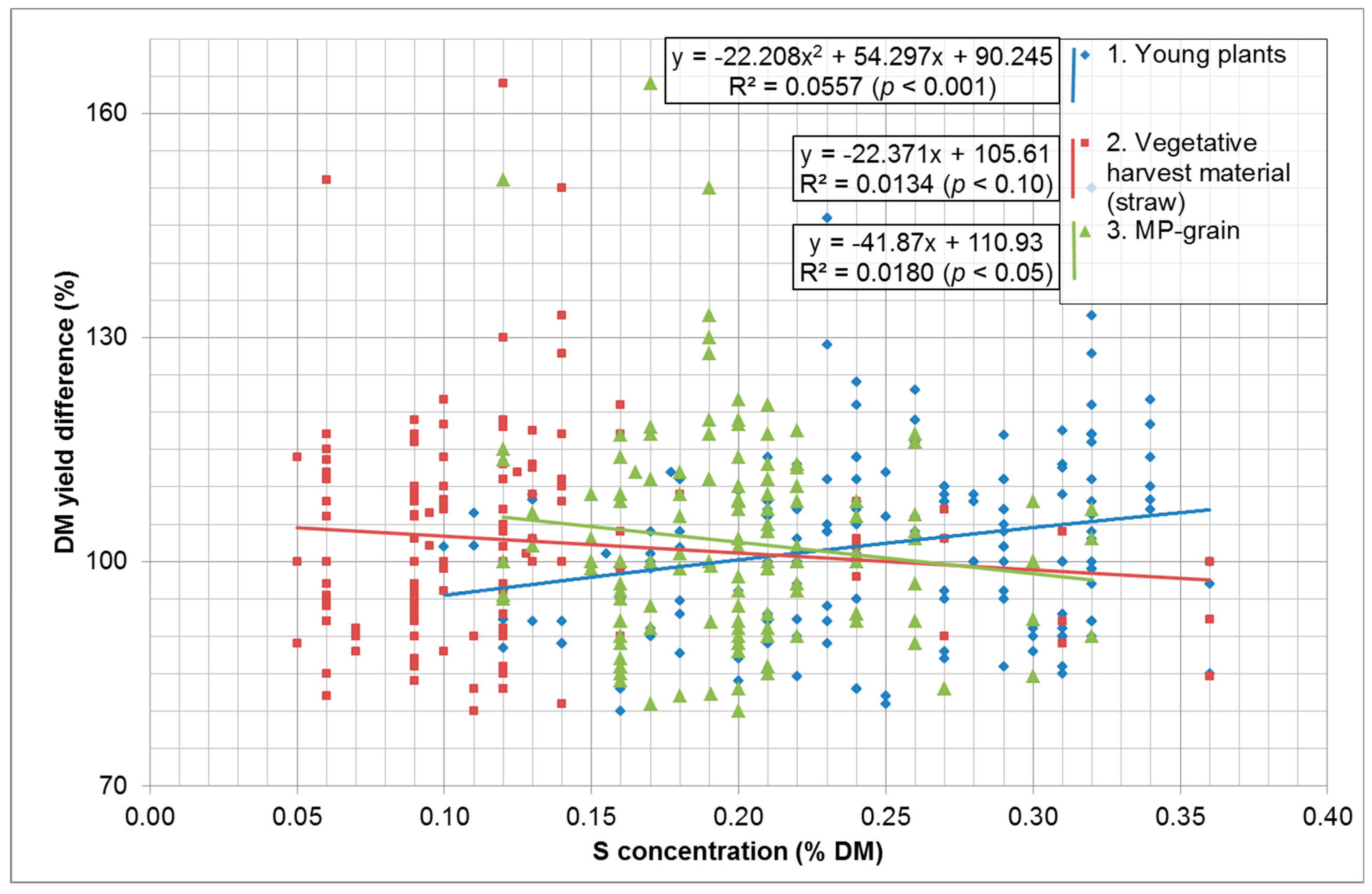

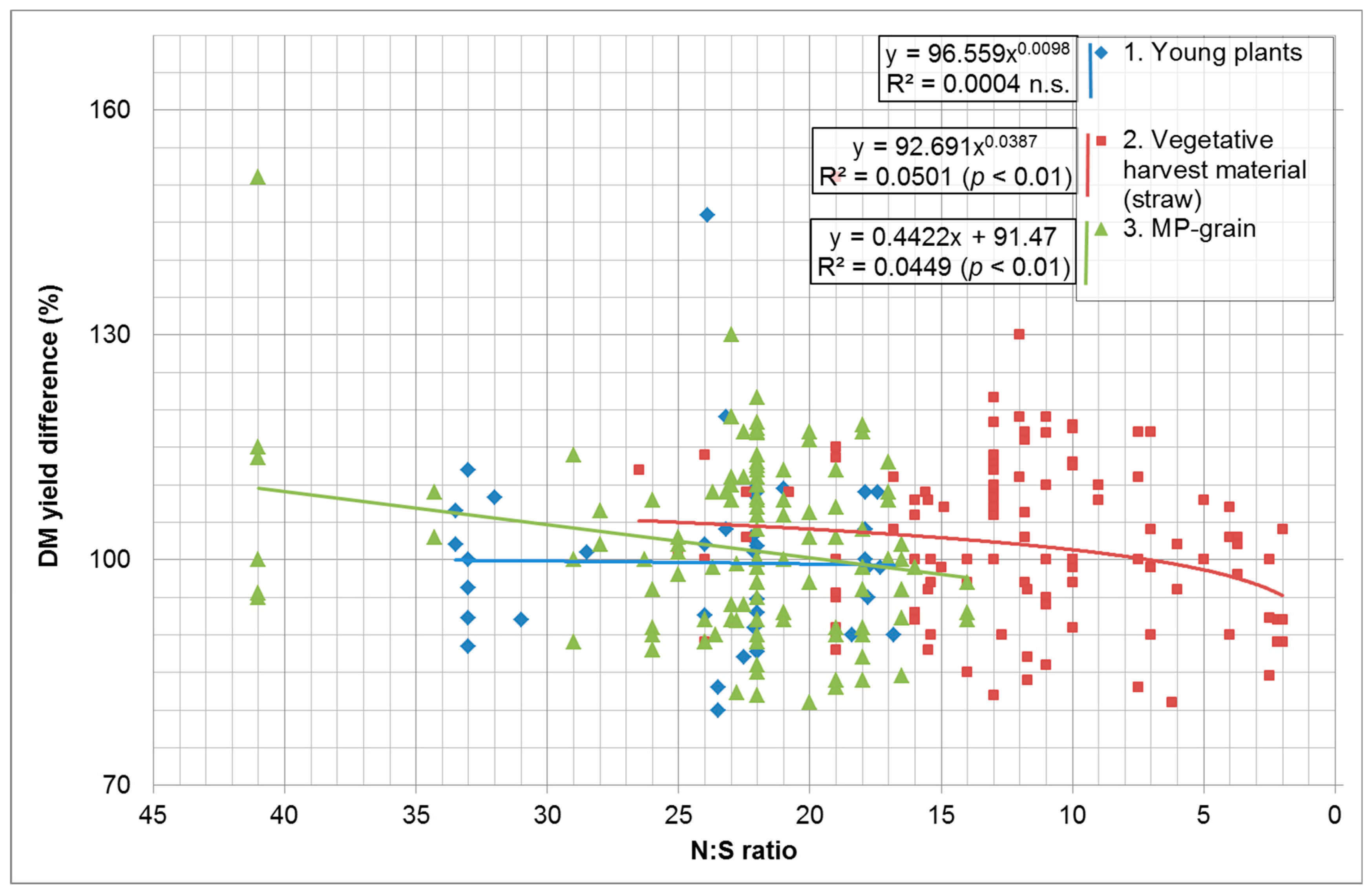

According to the results summarised in this study, which is generally much more extensive, the following course of increased yields after additional S fertilisation could be recognised for all trials examined, depending of the crop species and the S concentration of the plants:

- -

With very low S concentrations or wide N:S ratios, there were generally marked increases in yields with a wide range of variation, the additional yields generally increase exponentially as the S supply continues to decrease (extent strongly dependent on the crop species);

- -

In a transition range of S concentrations, there were hardly any yield effects (nutrient supply range for achieving optimum yields);

- -

From certain S concentrations upwards and N:S maximum ratios downwards, no more additional yields were recorded with relatively low variability (maximum yield levels).

In the extensive S fertilisation trials on arable forage crops in organic farming, in addition to the S concentrations, a rise in the N concentrations of perennial legume grasses and an increase in the proportion of legumes in the mixtures were also determined [

22,

28,

42]. In the mixtures, it was primarily the DM yields and the N concentration of the legume fraction that were increased and only slightly that of the non-legume fraction. The fertilised crops appeared more voluminous with larger leaf blades and had a darker green colour, probably due to increased chlorophyll levels, which was often still visible in the following year.

In the trials with grain legumes, however, S fertilisation treatments apparently hardly led to an increase in the N concentrations [

36]. This also appeared in the cereal trials. However, S foliar fertilisation increased the quality of durum wheat (N concentration, sedimentation test), but not the yield [

41]. According to the extensive evaluations presented here, the great importance of S fertilisation of arable forage for increasing the N concentrations in the growing crops and for shifting the legume-grass ratio in favour of the legume proportion could also be emphasised. This also occurred to a lesser extent in the mixtures between pea and oat cultivation. For further results, see Part 1 [

25].

4.2. Mean Nutrient Concentrations of Sulphur, Nitrogen and N:S Ratios of the Plant Species

First of all, evaluations showed that with r = 0.26 (

p < 0.001, n = 502) there are highly significant relationships between the S

min content (SO

4-S) of the soil at the start of vegetation (0–60 cm depth) and the S concentrations in various organs of the tested plant species of the standard variants (variants without S fertilisation). The results showed lower statistical significance in young plant material than in older plant material, as Link [

43] also found in the leaves of winter oilseed rape. At the same time, he was able to demonstrate that the relationships improved when the available sulphur was taken into account not only in the topsoil (0–30 cm depth) but also in deeper soil layers. Overall, however, it should be noted that these relationships are present, but not particularly close.

After the implementation of air pollution control measures, it was shown that not only the S

min content of the soil but also the S concentration in the plant species had decreased, in some cases quite markedly (see examples from Heyn, 2011, cited in [

44]). As a result, initial proposals for representative S concentrations of plant species in organic farming were made by combining data from the recent past without taking older work into account [

44,

45]. As the comparison of this data with the mean S and N concentrations of the crop species presented here shows, there is quite a good agreement in most cases (

Table 7). However, there are clearly large differences to the listed results from conventional literature sources. Some of these values are at a much higher level and have probably not yet been updated.

The S concentration of permanent grassland and arable forage in conventional farming was described in more detail by Elsäßer et al. [

46]: Grassland 0.14–0.29% S, pasture 0.20–0.29% S, mown pasture 0.20–0.28% S, field forage arable grass 3–4 cuts 0.26% S, LCG with 30% legumes 0.28% S, with 50% legumes 0.29% S, with 70% legumes 0.31% S, lucerne, red clover 0.33% S in DM. In this study, some data, such as on the permanent grassland or the lucerne-rich LCG stands, show slightly higher mean S concentrations in the trial data than previously assumed in the table values presented for organic farming (

Table 7). In contrast, the S concentrations in the red clover-favoured growths are at a lower level and there is a better agreement with the table values. Ref. [

22] also state an average S content of approx. 0.15% and a range of 0.08–0.30% S in DM in clover-grass growths. The crop data compiled here can therefore be used for the further revision of representative nutrient contents in organic farming.

4.3. Determination of Optimal Value Ranges for the S Concentrations and N:S Ratios of Plant Species for Organic and Conventional Cultivation Methods and Suggestions for Practical Use

There are quantitative correlations between the nutrient concentration in certain parts of the plant and times of development during the vegetation period and the yield formation of the crops. As a rule, young, just-formed plant organs such as leaves or stems up to the beginning of flowering are particularly suitable. In the case of young cereals, the entire above-ground plant is often used. In order to determine and fix sufficient nutrient levels that lead to undisturbed yield formation, extensive experimental studies have been carried out for each nutrient in the past. Their results have been described in detail and summarised in tables for practical use in various countries (Germany: Bergmann [

10], Australia: Reuter et al. [

11], USA: Mills & Jones [

49], Campbell [

50], Plucknett [

12]).

Due to a lack of own values, it was previously assumed that the nutrient concentrations determined under conventional conditions were also considered to be reliable in organic farming and were applied without critical examination. However, as the nutrient supply level in organic farming is usually clearly lower, these indicator values should also be at a correspondingly differentiated level [

19]. It is known that especially the N concentrations of non-legumes are up to 20% lower in organic farming [

44]. Furthermore, it is already clear that lower optimal content classes should be aimed for in the basic nutrients of the soil [

51]. As a result of this study, it also includes the S

min content of the soil (see Part I: [

25]). With regard to the nutrient sulphur, Haneklaus et al. [

52], for example, point out that higher S concentrations should be aimed for to achieve maximum yields than to ensure an optimum yield level.

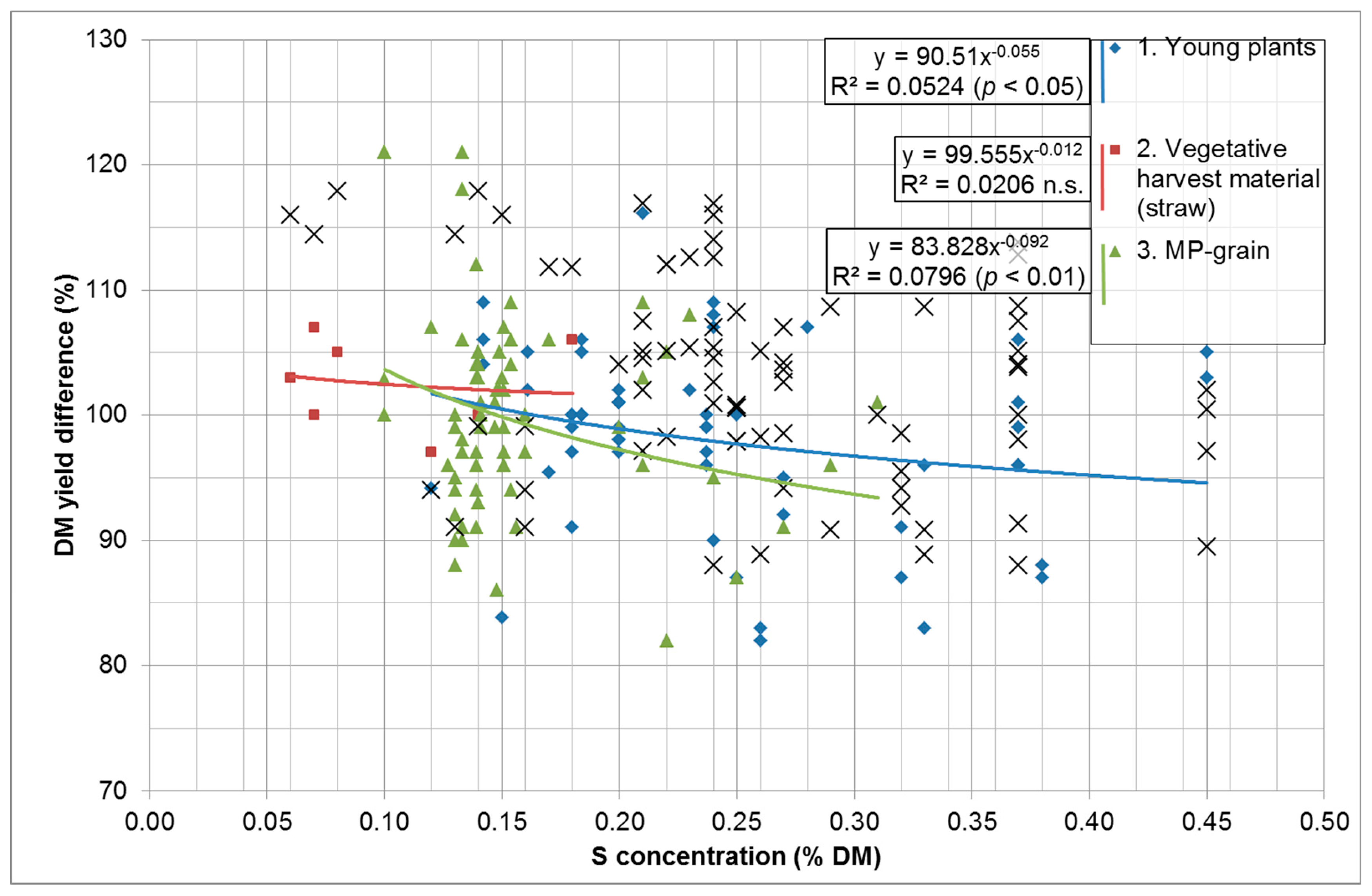

In principle, pot and field trials are suitable for plant analyses of the nutrient sulphur in order to determine sufficient S concentrations of the various plant species for undisturbed plant growth [

53]. In the field trials presented here, plant samples from three fractions were analysed as young plant material, by-products such as straw and main products such as grains for the nutrients sulphur and nitrogen. The extensive results were then initially used to define nutrient ranges for sulphur and for the N:S ratios using special forms of statistical analysis, which appear to be particularly suitable for the conditions in organic farming in order to guarantee optimum DM yields for the analysed plant species.

First of all, these studies have shown that it was obviously easier to determine optimal ranges for the S

min content of the soil and the expected yield. The effort required to crystallise optimal nutrient concentrations and N:S ratios, on the other hand, was much more complicated, partly because the plant data material originated from different vegetation stages and plant species. Initial comparisons of these determined values with published tables by Mills & Jones [

49] and Dick et al. [

54] in USA as well as Koch et al. [

55] and Olfs et al. [

56] in Germany for use in conventional practice have also produced unsatisfactory results (not shown). Subsequently, a more extensive collection of corresponding literature data from conventional agriculture was compiled for each plant species. For a more precise definition of value ranges for the Sulphur supply, an extended evaluation was then carried out with the use of boxplot analyses in order to finally achieve a better differentiation of the results obtained between the cultivation systems.

In the case of lucerne-clover-grasses (LCG), with over 10 individual values in most cases, a sufficiently high number of values were generally available for these analyses (

Table 8). The S concentrations in organic farming are on average at a somewhat lower level, which is particularly true for the A variants (mean 0.24%, median 0.25% S). Neither the maximum values nor the span range and standard deviation of the values in conventional farming were achieved. Nevertheless, including all calculation variants (A, B), only slightly different S concentrations for optimal yield formation were determined for both farming systems (mean and median between 0.24–0.28% S). This also applies in particular to the pure legume crops (LCG-legumes) listed separately in organic farming, which were selected from LCG-mixtures.

In contrast, the N:S ratios in the organic LCG, particularly in the A variant with 13.1–13.2 are at a slightly higher level than the values from conventional cultivation with values between 11.0–11.6. Compared to the N concentrations, only slightly lower S concentrations are therefore found in organic farming. The minimum values are in some cases clearly exceeded, while the range and the standard deviation are characterised by lower N:S values compared to conventional farming. Overall, however, the average values (mean, median) are again at a comparably high level in both systems with N:S ratios between 11.0–13.0. In the pre-sorted LCG-legume stands, slightly lower N:S ratios were even calculated with values around 10.6. The proportion of legumes in the organically grown LCG crops was approx. 62% (±20%).

Only a few surveys are available for the analyses of pure arable grass cultivation (

Table 9). In addition, the limited values for organic farming come from correspondingly selected LCG-mixture growths, as no trials with pure arable grass cultivation have been carried out to date. The S concentrations with values around 0.28–0.31% are approx. 0.10% S higher than those of conventional farming, while the average N:S ratios with values around 7.0 are only half as high. The analyses show that arable grasses in LCG mixtures have both relatively high S concentrations and relatively low N concentrations. In principle, these findings also apply to the growth from permanent grassland. There are therefore clear differences in the minimum sulphur concentration and the maximum N:S ratios in the growths of both types of grass (see

Table 9,

Table 10).

There are also only a few nutrient values from permanent grassland grown organically, which are characterised by a much smaller range and standard deviation (

Table 10). The mean minimum required S concentrations of 0.28 (0.26–0.29)% S are approx. 0.03–0.05% S higher than those from conventional production, while the maximum required N:S ratios of 9.1 (8.4–9.9) are at least 2.9–4.1 units lower than in conventional cultivation (mean, median). Permanent grassland stands from organic production were generally characterised by legume proportions of around 16% (±14%). No literature was available on the legume components from conventional cultivation. However, the values are generally at a very low level.

Even for the analyses of the grain legumes on average, the number of evaluable results was relatively low (

Table 11). In some cases, results from organic cultivation were even taken into account on the conventional side. In addition, particular evaluation difficulties were encountered with the data series of the young plants. The evaluations of the boxplot analyses of the young plants of grain legumes have shown that the minimum values of the S concentrations are higher, but the maximum values, the range and the standard deviation are at a much lower level than in the conventional comparative analyses. Using the calculated mean and median values, minimum values of between 0.23–0.27% S were determined in the young plants in organic crops, while values of between 0.29–0.39% S are considered necessary for optimum yield formation in conventional farming.

The reported maximum values of the N:S ratios showed significantly higher values with an average of over 4.0–5.0 units, but the range and the standard deviation were in some cases at a considerably lower level than in conventional farming. While maximum values in the N:S ratios between 19.0–20.0 can be considered sufficient in conventional farming (mean, median), according to these analyses N:S ratios between 23.0–25.0 can be sufficient to achieve an optimum yield level under organic farming conditions (

Table 11).

No reliable data from the conventional literature was found for the boxplot analyses of the straw and grain variants of grain legumes. From the few own data series, minimum required S concentrations for grain legume straw between 0.21–0.25% S and 0.22–0.24% S in grain materials of this plant group were determined. The widest N:S ratios of 9.3–12.1 in straw and 20.8–23.4 in the grains should not be exceeded, as otherwise a latent S deficiency and reduced yields are to be expected (

Table 12,

Table 13).

The number of S concentrations and N:S ratios found in the literature for assessing the parameters required to achieve optimum yields can be described as sufficient for the young plants of the cereal species (

Table 14). The ranges and the standard deviations achieved in the organic trials were again relatively low. For the S concentrations, the values in the lower supply range were still relatively consistent between the cultivation systems. However, the 75% quartiles or the maximum values were at a much higher level in conventional cultivation. For these reasons, the minimum required S concentrations in organic farming with values between 0.11–0.15% S in the young plants are more than 50% lower than the values in conventional farming (around 0.25% S, mean value, median).

The range and standard deviation of the conventional values of the N:S ratios were also at a clearly higher level than for the organically grown young plants. The organic N:S ratios are more concentrated in the middle range. Therefore, the calculated mean and median values with N:S ratios between 14.5–15.2 show a relatively high agreement between the two systems. This result is even remarkable as the N concentrations in the plant materials are usually higher in conventional cultivation due to the higher N fertilisation.

To characterise the required S supply of cereal straw, only a small number of values for the S concentrations were found in the literature (

Table 15). The mean and median values obtained correspond quite well with 0.11–0.15% S between the cultivation systems. For the N:S ratios, some data are only available from this study. N:S ratios around 7.0 seem to be sufficient as maximum values. Only a few values could also be determined for the assessment of the S supply of cereal grains (

Table 16). According to these results, the minimum concentrations of 0.11–0.13% S in organic farming are at a slightly lower level than those in conventional farming. In contrast, somewhat higher maximum values were found with N:S ratios of 13.0–14.0.

A sufficient number of values from conventional cultivation are available for evaluating the young plants of winter rape. Minimum values of 0.52–0.53% S and maximum values of between 8.4–8.5 in the N:S ratios can be considered to indicate optimum yield formation. In contrast, the S values from organic farming presented here are far from sufficient for a reliable assessment (

Table 17). The available data for both cropping systems is obviously not yet sufficient for an adequate assessment of the S supply of winter rape straw and grains and for maize in general. Therefore, no assessments are made in this regard.

At the end of the long evaluation process and discussion, the reliable values obtained were summarised in

Table 18 for use in agricultural practice. For the analysed crop groups lucerne-clover-grass, grain legumes and cereals (especially winter wheat), S and N:S values were determined with sufficient certainty due to the relatively high individual values. On the basis of the specified variation ranges, the following qualitative statements can be made about the necessary S concentrations of the individual grain legume species:

- -

Young plants: high: pea, field bean; medium to high: soya bean, field bean, lupine;

- -

Vegetative crop material (straw): high: lupine; medium: pea; low to medium: field bean;

- -

MP grain: high: lupine; medium: field bean; low to medium: pea.

The species of grain legumes also differ in their N:S ratios. The following levels can be documented on the basis of the specified value ranges (no data is available for soya bean):

- -

Young plants: low: pea; low to medium: field bean;

- -

Vegetative crop material (straw): low: lupine; low to medium: pea; medium: field bean;

- -

MP grain: low: pea, lupine; medium: field bean.

Only in the case of permanent grassland are the values determined not yet sufficient for a reliable assessment. The minimum required S concentrations of these crops to produce an optimum yield level are generally lower than in conventional farming. The difference between the cultivation systems is approx. 22%. In contrast, somewhat higher values can be tolerated for the maximum N:S ratios for lucerne-clover-grass, grain legumes and cereals (especially winter wheat). The difference between the two cultivation systems here is approx. 13% (

Table 18). For other crops such as oilseed rape, maize and permanent grassland, no exact values can yet be given. There is still a need for research, in some cases for both cultivation systems.