Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Data Quality Control

- (a)

- To improve the statistical confidence of the results, weather stations containing at least 50 years of available data were chosen.

- (b)

- The missing days were filled in (it was verified that all series recorded 18,262 days); that is, 38 normal years and 12 leap years.

- (c)

- It was verified that Tmax > Tmin and that Eva ≥ 0.

- (d)

- Missing daily data were imputed using the method of interpolation of standardized neighboring series [32].

- (e)

2.3. Reference Evapotranspiration (ETo)

2.3.1. Alternative Methods ()

2.3.1.1. Romanenko (EToRo)

2.3.1.2. Priestley–Taylor (EToPT)

2.3.1.3. McGuinness Bordne (EToMB)

2.3.1.4. Hargreaves (EToH75)

2.3.1.5. Pan-Evaporation (EToTE)

2.3.1.6. Hargreaves (EToH85)

2.3.1.7. Oudin (EToOu)

2.3.2. Standard Method

2.3.2.1. Penman–Monteith

2.4. Performance Metrics Between the Seven Alternative Methods () and the Penman–Monteith Method with Limited Data (EToPM)

2.4.1. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

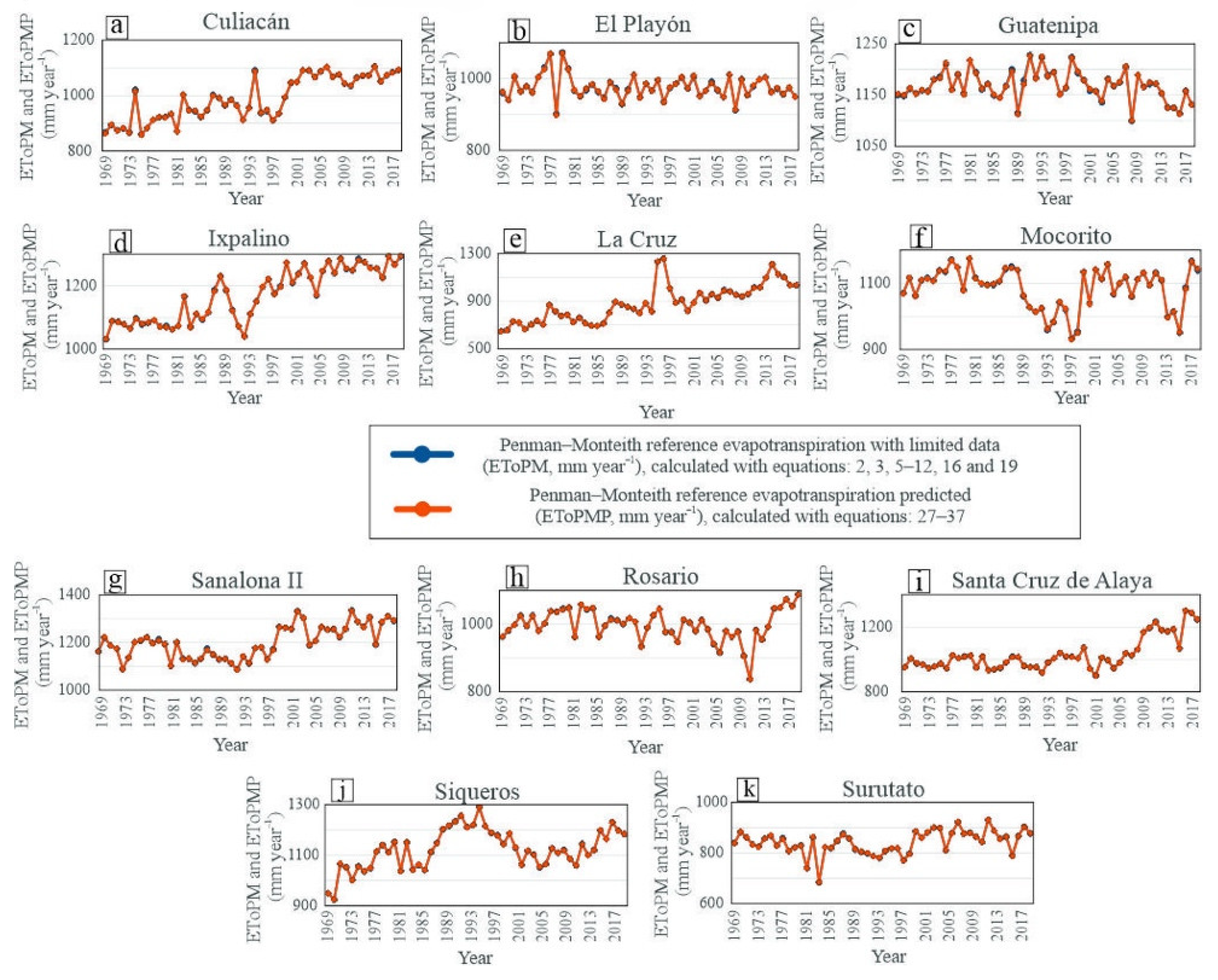

2.5. Predictive models of Penman–Monteith Annual Cumulative Reference Evapotranspiration with Limited Data (EToPMP)

2.6. Validation

2.6.1. Predictive Models of Penman–Monteith Annual Cumulative Reference Evapotranspiration with Limited Data (EToPMP)

- (a)

- Normality: the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to the residuals of the linear regressions.

- (b)

- If the residuals of the linear regressions were normal, the model was considered validated, otherwise, a non-linear regression (square polynomial) was applied.

- (c)

- Homogeneity: the nullity of the averages of the residuals of all regressions (linear and non-linear) was verified.

- (d)

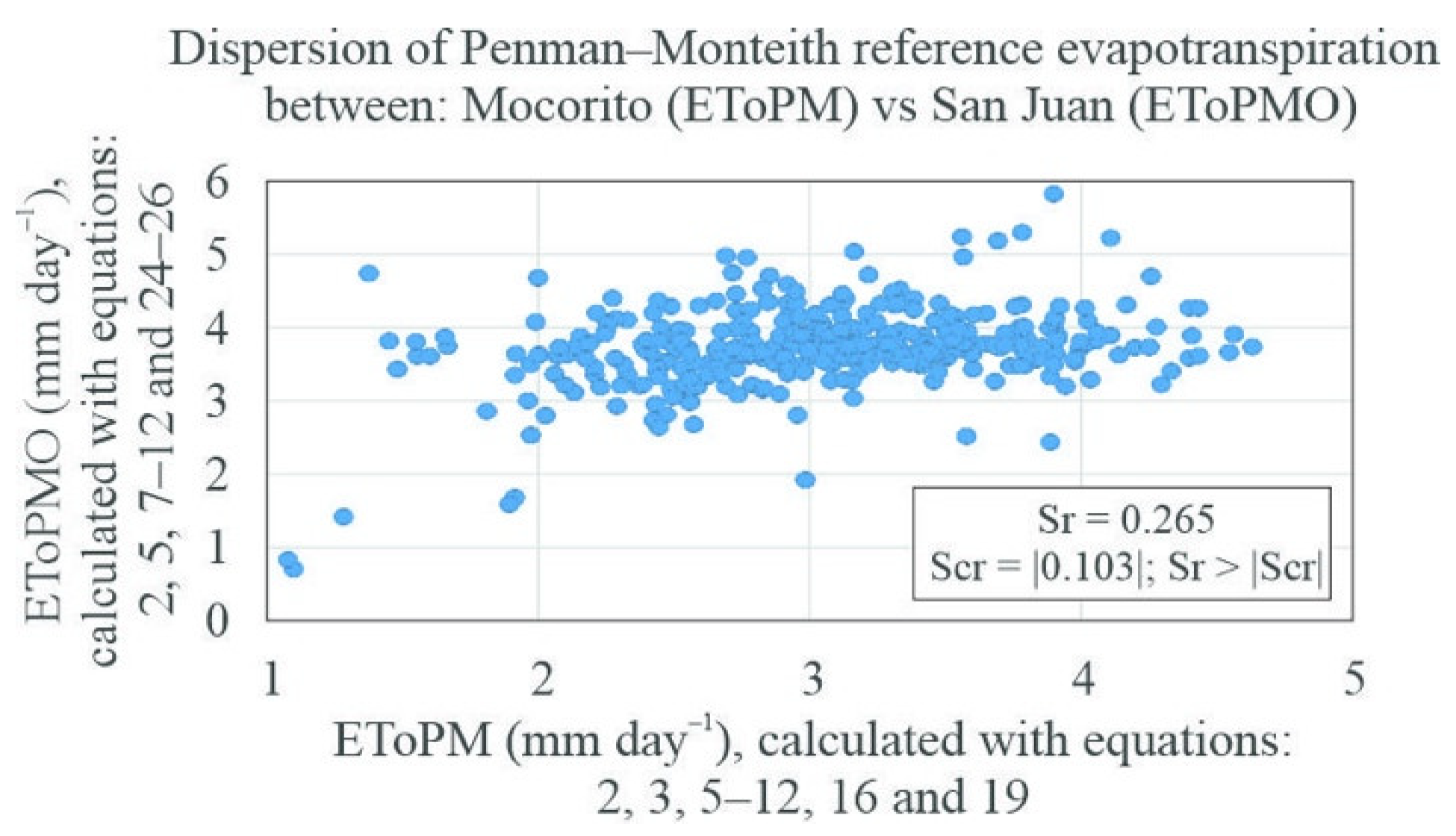

- Linearity and fit: a correlation hypothesis test was designed (Equations 22 and 23), where the goodness of fit of the models was evaluated. All linear regressions showed linearity: Pearson correlation (Pr) ≥ Pearson critical correlation (|Pcr|) [(|Pcr| = 0.279; n = 50)]. All non–linear regressions showed good fit: Spearman correlation (Sr) ≥ Spearman critical correlation (|Scr|) [(|Scr| = 0.280; n = 50)]. In all models, Pr and Sr were obtained using √R2.

2.6.2. Penman–Monteith Daily Reference Evapotranspiration with Limited Data (EToPM)

2.7. Software Used and Significance of Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Variation of the Temperatures Maximum (Tmax), Minimum (Tmin) and Mean (Tmean), and the Evaporation (Eva)

3.2. Average Daily Reference Evapotranspiration (ETo) Estimated Using Seven Alternative Methods () and the Penman–Monteith Method with Limited Data (EToPM)

3.3. Performance Metrics Comparing the Seven Alternative Methods () with the Penman–Monteith Method with Limited Data (EToPM)

3.4. Predictive Models of Penman–Monteith Annual Cumulative Reference Evapotranspiration with Limited Data (EToPMP)

3.5. Validation

3.5.1. Predictive Models of Penman–Monteith Annual Cumulative Reference Evapotranspiration with Limited Data (EToPMP)

3.5.1.1. Normality of Residuals

3.5.1.2. Linearity and Fit

3.5.1.3. Homogeneity of Residuals

3.5.2. Spearman Correlation (Sr) Between Daily Penman–Monteith Reference Evapotranspiration and Limited Data In Mocorito (EToPM), and Observed Data in San Juan (EToPMO)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matsui, H.; Osawa, K. Alternative net longwave radiation equation for the FAO Penman–Monteith evapotranspiration equation and the Penman evaporation equation. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 153, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.G.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.E.; Chung, I.M. Calibration and Evaluation of Alternative Methods for Reliable Estimation of Reference Evapotranspiration in South Korea. Water 2024, 16, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagi, A.; Nagy, A.; Mohammed, S.; Pande, C.B.; Kumar, M.; Bhat, S.A.; Zsembeli, J.; Huzsvai, L.; Tamás, J.; Kovács, E.; Harsányi, E.; Juhász, C. Combination of Limited Meteorological Data for Predicting Reference Crop Evapotranspiration Using Artificial Neural Network Method. Agronomy 2022, 12, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.L.; Lin, Y.S.; Chang, S.C.; Chang, Y.L.; Ysai, B.Y.; Kuo, B.J. Using Artificial Intelligence Algorithms to Estimate and Short-Term Forecast the Daily Reference Evapotranspiration with Limited Meteorological Variables. Agriculture 2024, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matimolane, S.; Strydom, S.; Mathivha, F.I.; Chikoore, H. Evaluating the spatiotemporal patterns of drought characteristics in a semi-arid region of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, S.J.; Zarzoza, M.S.B.; Supit, I.; Wang, M. Compound and cascading droughts and heatwaves decrease maize yields by nearly half in Sinaloa, Mexico. npj Nat. Hazards 2024, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skhiri, A.; Ferhi, A.; Bousselmi, A.; Khlifi, S.; Mattar, M.A. Artificial Neural Network for Forecasting Reference Evapotranspiration in Semi-Arid Bioclimatic Regions. Water 2024, 16, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, P.; Sona, F.; Surendran, U.; Srinivas, C.V.; Kannan, K.; Madhu, M.; Mahesh, P.; Annepu, S.K.; Ahmed, M.; Chandrasekar, K.; Suguna, A.R.; Kumar, V.; Jagadesh, M. Performance evaluation of different empirical models for reference evapotranspiration estimation over Udhagamandalm, The Nilgiris, India. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Lu, F.; Xiao, W.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, Z. Performance of 12 reference evapotranspiration estimation methods compared with the Penman–Monteith method and the potential influences in northeast China. Meteorol. Appl. 2018, 26, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestin, S.; Qi, F.; Li, R.; Yu, T.; Cheng, W. Evaluation of 32 Simple Equations against the Penman–Monteith Method to Estimate the Reference Evapotranspiration in the Hexi Corridor, Northwest China. Water 2020, 12, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunlar, A.; Dis, M.O. Novel Approaches for the Empirical Assessment of Evapotranspiration over the Mediterranean Region. Water 2024, 16, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanenko, V.A. Computation of the autumn soil moisture using a universal relationship for a large area, Proc. Ukrainian Hydrometeorological Research Institute, 1961. Kiev. No. 3.

- 13. Vásquez, M.R.; Ventura, R.E.J.; Acosta, G.J.A. Habilidad de estimación de los métodos de evapotransporación para una zona semiárida del centro de México. Rev. Mexicana cienc. agric. 2011, 2, 399–415. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-09342011000300008.

- Gao, F.; Feng, G.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, H.; Fisher, D.; Adeli, A.; Jenkins, J. Evaluation of Reference Evapotranspiration Methods in Arid, Semiarid, and Humid Regions. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2017, 53, 791–808. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/ja/2017/ja_2017_ouyang_008.pdf.

- Priestley, C.H.B.; Taylor, R.J. On the assessment of surface heat-flux and evaporation using large-scale parameters. MWR 1972, 100, 81–92. https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/mwre/100/2/1520-0493_1972_100_0081_otaosh_2_3_co_2.xml.

- McGuinness, J.L.; Bordne, E.F. A comparison of lysimeter-derived potential evapotranspiration with computed values. TB1452. U. S. Department of Agricultural. Tech. Bull. 1972, 1452. 71. https://www.google.es/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/171893/files/tb1452.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwik7NXD-cyJAxUSJ0QIHeztMeQQFnoECBAQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2Fqxo_hE0RQt6TL4JM5yfJ.

- Oudin, L.; Hervieu, F.; Michel, C.; Perrin, C.; Andréassian, V.; Anctil, F.; Loumagne, C. Which potential evapotranspiration input for a lumped rainfall-runoff model? Part 2-Towards a simple and efficient potential evapotranspiration model for rainfall-runoff modeling. J. Hydrol. 2005, 303:290-306. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, R.; Han, C.; Liu, Z. Evaluation of 18 models for calculating potential evapotranspiration in different climatic zones of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 244, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Jia, G.; Chen, P.; Zheng, P.; Wang, Y.; Ding, B. Applicability and improvement of different potential evapotranspiration models in different climate zones of China. Ecol. Process. 2024, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, G.H. Moisture availability and crop production. Trans. ASAE 1975, 18, 980–984. https://elibrary.asabe.org/abstract.asp?aid=36722&t=2&redir=&redirType=.

- 21. Hargreaves, G.H.; Samani, Z.A. Reference crop evapotranspiration from ambient air temperature. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1985, 1, 96–99. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247373660_Reference_Crop_Evapotranspiration_From_Temperature.

- Hargreaves, G.H.; ASCE, F.; Allen, R.G. History and evaluation of Hargreaves evapotranspiration equation. J. Irrig. Drain Eng. 2003, 129, 53–63. https://uon.sdsu.edu/onlinehargreaves.pdf.

- Usta, S. Estimation of reference evapotranspiration using some class-A pan evaporimeter pan coefficient estimation models in Mediterranean–Southeastern Anatolian transitional zone conditions of Turkey. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, C.O.; Norzagaray, C.M.; Gaxiola, A.; Pérez, G.E.; Montiel, M.J.; Troyo, D.E. Sensitivity of Four Indices of Meteorological Drought for Rainfed Maize Yield Prediction in the State of Sinaloa, Mexico. Agriculture 2022, 12, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional del Agua–Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (CONAGUA–SMN). Base de datos meteorológicos de México. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/informacion-climatologica/informacion-estadistica-climatologica (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration: guidelines for computing crop water requirements. 1998, No. 56, Ed. FAO. Rome, 327 p. https://www.fao.org/4/x0490e/x0490e00.htm.

- Satpathi, A.; Danodia, A.; Abed, S.A.; Nain, A.S.; Al–Ansari, N.; Ranjan, R.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Gacem, A.; Mansour, L.; Yadav, K.K. Estimation of the crop evapotranspiration for Udham Singh Nagar district using modified Priestley-Taylor model and Landsat imagery. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14:21463. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72299-x. [CrossRef]

- Consejo para el Desarrollo Económico de Sinaloa (CODESIN). Sinaloa en números: agricultura en Sinaloa al 2022. 2023, 10. https://sinaloaennumeros.codesin.mx/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Reporte-24-del-2023-de-Agricultura-en-sinaloa-2022.pdf.

- Galindo, R.J.G.; Alegría, H. Toxic effects of exposure to pesticides in farm workers in Navolato, Sinaloa (Mexico). Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2018, 34, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, C.L.M.; Arzola, G.J.F.; Ramírez, S.M.; Osorio, P.A. Global climate change impacts in the Sinaloa state, Mexico. Cuad. Geogr. 2012, 21, 115–129. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0121-215X2012000100009.

- Comisión Nacional del Agua–Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (CONAGUA–SMN). Base de datos meteorológicos de México. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/tools/GUI/sivea_v3/sivea.php (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Kennedy, S.R.; Chen, C.D.; Guijarro, J.A.; Chen, Y. Quantifying the evolving role of intense precipitation runoff when calculating soil moisture trends in east Texas. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2023, 135, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandersson, H. A homogeneity test applied to precipitation data. J. Climatol. 1986, 6, 661−675. [CrossRef]

- Perčec, T.M.; Pasarić, Z.; Guijarro, J.A. Croatian high-resolution monthly gridded dataset of homogenized surface air temperature. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 15, 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, J.A. Package ‘climatol’ version 4.1.0: climate tools (series homogenization and derived products). Repository CRAN, 2024, 41 p. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/climatol/climatol.pdf.

- Rubin, DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. 2004, 81. New York: Wiley. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Multiple+Imputation+for+Nonresponse+in+Surveys-p-9780471655749.

- Remiro, A.A.; Heath, A.; Baio, G. Model–based standardization using multiple imputation. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penman, H. L. Natural evaporation from open water, bare soil and grass. Proc. R. Soc. 1948, 193, 120-145. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/epdf/10.1098/rspa.1948.0037.

- Sentelhas, P.C.; Gillespie, T.J.; Santos, E.A. Evaluation of FAO Penman–Monteith and alternative methods for estimating reference evapotranspiration with missing data in Southern Ontario, Canada. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, R.E.; González, C.G.; González, B.J.L.; Dzul, L.E.; Sánchez, C.I.; López, S.A.; Chávez, S.J.A. Uso de estaciones climatológicas automáticas y modelos matemáticos para determinar la evapotranspiración. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2013, 4, 115–126. https://www.revistatyca.org.mx/index.php/tyca/article/view/381.

- Doorenbos, J.; Pruitt, W. Guidelines for predicting crop water requirements. Rome: FAO. 1977. https://www.fao.org/4/f2430e/f2430e.pdf.

- Córdova M., Carrillo R.G., Crespo P., Wilcox B., Célleri R. Evaluation of the Penman–Monteith (FAO 56 PM) Method for Calculating Reference Evapotranspiration Using Limited Data. Mt. Res. Dev. 2015, 35, 230–239. [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.J.; Feng, H.Y.; Sheng, Y.S.L.; Wen, T.J. Comparative assessment of reference crop evapotranspiration models and its sensitivity to meteorological variables in Peninsular Malaysia. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2022, 36, 3557–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, H.Z.; Szalka, É.; Szakál, T. Determination of Reference Evapotranspiration Using Penman-Monteith Method in Case of Missing Wind Speed Data under Subhumid Climatic Condition in Hungary. Atmos. Clim. Sci. 2022, 12, 235-245. https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=115214.

- Yonaba, R.; Tazen, F.; Cissé, M.; Adjadi, M.L.; Belemtougri, A.; Alligouamé, O.V.; Koïta, M.; Niang, D.; Karambiri, H.; Yacouba, H. Trends, sensitivity and estimation of daily reference evapotranspiration ETo using limited climate data: regional focus on Burkina Faso in the West African Sahel. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 153, 947–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, I.; Pimentel, E. Zonificación agroclimática de Papadakis aplicada al estado de Sinaloa, México. Inv. Geog. 2010, 73, 86–102. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-46112010000300007.

- Galindo, I.; Castro, S.; Valdes, M. Satellite derived solar irradiance over Mexico. Atmósfera 1991, 189–201. http://www.ejournal.unam.mx/atm/Vol04-3/ATM04306.pdf.

- López, A.J.E.; López, I.H.J.; Tirado, R.M.A.; Estrada, A.M.D.; Martínez, G.J.A. Requerimiento hídrico, coeficiente de cultivo y productividad de pasto híbrido Convert 330 (Brachiaria sp) en un clima semiárido cálido de México. Terra Latinoam. 2024, 42, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, C.O. Predictive association between meteorological drought and climate indices in the state of Sinaloa, northwestern Mexico. Arab. J. Geosci. 2023, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.J.M.; Cervantes, O.R.; Ojeda, B.W.; López, C.I. Predicción de la evapotranspiración de referencia mediante redes neuronales artificiales. Ing. Hidraul. Mex. 2008, 13, 127–138. http://repositorio.imta.mx/handle/20.500.12013/852.

- Valdes, B.M.; Riveros, R.D.; Arancibia, B.C.A.; Bonifaz, R. The solar resource assessment in Mexico: state of the art. Energy Proc. 2013, 57, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndule, E.; Ranjan, S.R. Performance of the FAO Penman-Monteith equation under limiting conditions and fourteen reference evapotranspiration models in southern Manitoba. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 143, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, R.S.; Arteaga, R.R.; Sangerman, J.D.M.; Cervantes, O.R.; Navarro, B.A. Reference evapotranspiration estimated by Penman-Monteith-Fao, Priestley-Taylor, Hargreaves and ANN. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2012, 3, 1535–1549. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-09342012000800005.

- Azua, B.M.; Arteaga, R.R.; Vázquez, P.M.A.; Quevedo, N.A. Calibración y evaluación de modelos matemáticos para calcular evapotranspiración de referencia en invernaderos. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2020, 11, 125–137. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/remexca/v11n1/2007-0934-remexca-11-01-125.pdf.

- Morantes, Q.G.R.; Rincón, P.G.; Pérez, S.N.A. Modelo de Regresión Lineal Múltiple Para Estimar Concentración de PM1. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambie. 2019, 35, 179–194. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S0188-49992019000100179&script=sci_abstract.

- Llanes, C.O.; Estrella, G.R.D.; Parra, G.R.E.; Gutiérrez, R.O.G.; Ávila, D.J.A.; Troyo, D.E. Modeling Yield of Irrigated and Rainfed Bean in Central and Southern Sinaloa State, Mexico, Based on Essential Climate Variables. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasquilla, B.A.; Chacón, R.A.; Núñez, M.K.; Gómez, E.O.; Valverde, J.; Guerrero, B.M. Regresión Lineal Simple y Múltiple: Aplicación en la Predicción de Variables Naturales Relacionadas con el Crecimiento Microalgal. Tecnología en Marcha. Encuentro de Investigación y Extensión; 2016, 33–45. https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?pid=S0379-39822016000900033&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es.

- Oxford Cambridge and RSA (OCR). Formulae and Statistical Tables (ST1). 1–8: Database of Critical Values. https://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/174103-unit-h869-02-statistical-problem-solving-statistical-tables-st1-.pdf. (accessed on 20 June 2024).

| Weather station | Statistical inference | Tmax (°C) | Tmin (°C) | Tmean (°C) | Eva (mm) |

| Culiacán | Average | 32.921 | 19.545 | 26.230 | 5.769 |

| maximum | 46.000 | 30.000 | 36.700 | 17.900 | |

| Minimum | 15.500 | 2.000 | 11.000 | 0.000 | |

| El Playón | Average | 31.361 | 16.863 | 24.112 | 6.648 |

| maximum | 45.500 | 37.000 | 38.000 | 17.800 | |

| Minimum | 13.000 | –6.000 | 8.750 | 0.100 | |

| Guatenipa | Average | 34.633 | 17.789 | 26.211 | 4.890 |

| maximum | 47.000 | 30.000 | 36.500 | 14.700 | |

| Minimum | 15.000 | 0.500 | 11.500 | 0.000 | |

| Ixpalino | Average | 34.229 | 17.318 | 25.774 | 4.878 |

| maximum | 46.000 | 28.500 | 34.250 | 17.400 | |

| Minimum | 18.000 | –1.200 | 11.400 | 0.100 | |

| La Cruz | Average | 30.299 | 17.447 | 23.872 | 4.409 |

| maximum | 42.000 | 33.000 | 34.500 | 18.000 | |

| Minimum | 12.000 | 0.000 | 9.100 | 0.000 | |

| Mocorito | Average | 32.971 | 17.318 | 25.144 | No value |

| maximum | 45.000 | 32.000 | 37.500 | No value | |

| Minimum | 9.000 | 0.000 | 6.250 | No value | |

| Sanalona II | Average | 33.872 | 15.847 | 24.860 | 5.464 |

| maximum | 44.000 | 28.500 | 35.000 | 17.800 | |

| Minimum | 17.000 | –5.000 | 8.250 | 0.000 | |

| Rosario | Average | 32.659 | 18.735 | 25.697 | 4.810 |

| maximum | 41.000 | 31.000 | 35.000 | 16.600 | |

| Minimum | 17.000 | 1.400 | 12.750 | 0.000 | |

| Santa Cruz de Alaya | Average | 32.476 | 17.763 | 25.118 | 5.543 |

| maximum | 43.000 | 34.000 | 37.000 | 15.400 | |

| Minimum | 13.400 | 1.000 | 11.800 | 0.000 | |

| Siqueros | Average | 33.907 | 17.958 | 25.932 | 4.746 |

| maximum | 43.000 | 28.500 | 34.500 | 14.600 | |

| Minimum | 17.000 | –0.500 | 11.000 | 0.000 | |

| Surutato | Average | 24.995 | 7.257 | 16.126 | 3.976 |

| maximum | 37.500 | 20.500 | 27.500 | 12.500 | |

| Minimum | 9.000 | –6.000 | 2.300 | 0.000 |

| Weather station | Average reference evapotranspiration (mm day–1) 1969–2018 (mm day–1) |

||||||||

| Month | EToPM | EToH85 | EToH75 | EToPT | EToTE | EToMB | EToRo | EToOu | |

| Culiacán | Jan | 2.196 | 3.245 | 3.047 | 2.317 | 2.190 | 3.668 | 6.363 | 2.494 |

| Feb | 2.467 | 4.040 | 3.794 | 3.180 | 2.895 | 4.491 | 6.792 | 3.054 | |

| Mar | 2.854 | 5.064 | 4.756 | 4.246 | 3.990 | 5.545 | 7.484 | 3.771 | |

| Apr | 3.219 | 6.031 | 5.664 | 5.264 | 4.935 | 6.719 | 8.088 | 4.569 | |

| May | 3.413 | 6.564 | 6.164 | 5.889 | 5.647 | 7.781 | 8.317 | 5.291 | |

| Jun | 3.078 | 6.108 | 5.736 | 5.717 | 5.835 | 8.501 | 7.085 | 5.781 | |

| Jul | 2.923 | 5.885 | 5.527 | 5.553 | 4.775 | 8.497 | 6.642 | 5.778 | |

| Aug | 2.724 | 5.483 | 5.149 | 5.156 | 4.224 | 8.063 | 6.298 | 5.483 | |

| Sep | 2.488 | 4.843 | 4.548 | 4.482 | 3.751 | 7.248 | 6.038 | 4.928 | |

| Oct | 2.601 | 4.497 | 4.223 | 3.843 | 3.529 | 5.975 | 7.097 | 4.063 | |

| Nov | 2.397 | 3.682 | 3.458 | 2.776 | 2.680 | 4.429 | 7.066 | 3.011 | |

| Dec | 2.112 | 3.047 | 2.861 | 2.109 | 1.996 | 3.537 | 6.283 | 2.405 | |

| El Playón | Jan | 2.298 | 3.199 | 3.004 | 2.094 | 2.614 | 3.197 | 6.428 | 2.174 |

| Feb | 2.553 | 3.981 | 3.739 | 2.957 | 3.304 | 3.946 | 6.819 | 2.683 | |

| Mar | 2.866 | 4.939 | 4.638 | 4.007 | 4.413 | 4.931 | 7.341 | 3.353 | |

| Apr | 3.070 | 5.747 | 5.397 | 4.961 | 5.425 | 6.088 | 7.593 | 4.140 | |

| May | 3.273 | 6.326 | 5.941 | 5.606 | 6.211 | 7.074 | 7.932 | 4.810 | |

| Jun | 2.847 | 5.813 | 5.460 | 5.429 | 6.554 | 8.021 | 6.564 | 5.454 | |

| Jul | 2.722 | 5.625 | 5.283 | 5.346 | 5.527 | 8.304 | 6.125 | 5.647 | |

| Aug | 2.621 | 5.349 | 5.023 | 5.060 | 4.979 | 7.943 | 6.027 | 5.402 | |

| Sep | 2.470 | 4.819 | 4.526 | 4.464 | 4.411 | 7.110 | 6.020 | 4.835 | |

| Oct | 2.585 | 4.440 | 4.170 | 3.736 | 4.142 | 5.664 | 7.075 | 3.851 | |

| Nov | 2.524 | 3.692 | 3.467 | 2.612 | 3.192 | 4.032 | 7.320 | 2.742 | |

| Dec | 2.263 | 3.053 | 2.867 | 1.920 | 2.483 | 3.131 | 6.523 | 2.129 | |

| Guatenipa | Jan | 2.596 | 3.578 | 3.360 | 2.331 | 1.785 | 3.618 | 7.677 | 2.460 |

| Feb | 2.999 | 4.589 | 4.309 | 3.379 | 2.476 | 4.584 | 8.479 | 3.117 | |

| Mar | 3.544 | 5.877 | 5.520 | 4.682 | 3.498 | 5.819 | 9.570 | 3.957 | |

| Apr | 4.040 | 7.102 | 6.670 | 5.971 | 4.530 | 7.200 | 10.506 | 4.896 | |

| May | 4.321 | 7.798 | 7.323 | 6.767 | 5.260 | 8.275 | 10.972 | 5.627 | |

| Jun | 3.906 | 7.299 | 6.855 | 6.604 | 4.891 | 8.710 | 9.640 | 5.923 | |

| Jul | 3.141 | 6.304 | 5.921 | 5.861 | 3.516 | 8.149 | 7.611 | 5.541 | |

| Aug | 2.898 | 5.834 | 5.479 | 5.417 | 3.050 | 7.680 | 7.144 | 5.223 | |

| Sep | 2.724 | 5.222 | 4.904 | 4.733 | 2.715 | 6.897 | 7.065 | 4.690 | |

| Oct | 2.955 | 4.898 | 4.600 | 3.986 | 2.527 | 5.661 | 8.442 | 3.850 | |

| Nov | 2.815 | 4.032 | 3.786 | 2.801 | 2.055 | 4.244 | 8.482 | 2.886 | |

| Dec | 2.462 | 3.316 | 3.115 | 2.096 | 1.599 | 3.451 | 7.460 | 2.346 | |

| Ixpalino | Jan | 2.906 | 3.859 | 3.624 | 2.449 | 1.862 | 3.721 | 8.171 | 2.530 |

| Feb | 3.257 | 4.787 | 4.495 | 3.418 | 2.445 | 4.526 | 8.739 | 3.077 | |

| Mar | 3.676 | 5.894 | 5.535 | 4.569 | 3.271 | 5.513 | 9.430 | 3.749 | |

| Apr | 3.993 | 6.876 | 6.458 | 5.653 | 4.062 | 6.629 | 9.966 | 4.508 | |

| May | 4.058 | 7.323 | 6.877 | 6.274 | 4.801 | 7.623 | 10.032 | 5.184 | |

| Jun | 3.479 | 6.648 | 6.243 | 6.047 | 4.715 | 8.354 | 8.329 | 5.681 | |

| Jul | 3.109 | 6.157 | 5.782 | 5.716 | 3.657 | 8.284 | 7.291 | 5.633 | |

| Aug | 2.855 | 5.690 | 5.344 | 5.289 | 3.160 | 7.862 | 6.775 | 5.346 | |

| Sep | 2.616 | 5.049 | 4.742 | 4.627 | 2.884 | 7.105 | 6.475 | 4.831 | |

| Oct | 2.842 | 4.794 | 4.502 | 4.013 | 2.767 | 5.938 | 7.803 | 4.038 | |

| Nov | 2.933 | 4.191 | 3.936 | 2.958 | 2.221 | 4.469 | 8.546 | 3.039 | |

| Dec | 2.755 | 3.609 | 3.389 | 2.252 | 1.715 | 3.631 | 8.015 | 2.469 | |

| La Cruz | Jan | 2.143 | 3.162 | 2.969 | 2.206 | 1.625 | 3.382 | 5.990 | 2.300 |

| Feb | 2.365 | 3.878 | 3.642 | 3.003 | 2.114 | 4.062 | 6.305 | 2.762 | |

| Mar | 2.624 | 4.732 | 4.444 | 3.956 | 2.93 | 4.987 | 6.715 | 3.391 | |

| Apr | 2.862 | 5.516 | 5.181 | 4.837 | 3.658 | 6.015 | 7.073 | 4.090 | |

| May | 2.909 | 5.863 | 5.506 | 5.318 | 4.264 | 7.001 | 7.019 | 4.761 | |

| Jun | 2.504 | 5.312 | 4.988 | 5.054 | 4.583 | 7.833 | 5.669 | 5.327 | |

| Jul | 2.415 | 5.154 | 4.840 | 4.951 | 3.884 | 7.996 | 5.358 | 5.437 | |

| Aug | 2.368 | 4.991 | 4.688 | 4.763 | 3.393 | 7.667 | 5.386 | 5.213 | |

| Sep | 2.221 | 4.50 | 4.226 | 4.224 | 3.036 | 6.949 | 5.307 | 4.726 | |

| Oct | 2.276 | 4.135 | 3.883 | 3.615 | 2.734 | 5.727 | 6.062 | 3.894 | |

| Nov | 2.252 | 3.539 | 3.324 | 2.695 | 2.089 | 4.258 | 6.490 | 2.895 | |

| Dec | 2.071 | 2.987 | 2.806 | 2.041 | 1.521 | 3.339 | 5.959 | 2.271 | |

| Weather station | Average reference evapotranspiration (mm day–1) 1969–2018 (mm day–1) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | EToPM | EToH85 | EToH75 | EToPT | EToTE | EToMB | EToRo | EToOu | |

| Mocorito | Jan | 2.350 | 3.263 | 3.064 | 2.135 | No value value | 3.319 | 6.675 | 2.257 |

| Feb | 2.694 | 4.142 | 3.890 | 3.050 | No value | 4.137 | 7.285 | 2.813 | |

| Mar | 3.228 | 5.366 | 5.039 | 4.261 | No value | 5.261 | 8.366 | 3.577 | |

| Apr | 3.698 | 6.525 | 6.128 | 5.450 | No value | 6.509 | 9.258 | 4.426 | |

| May | 3.969 | 7.223 | 6.783 | 6.238 | No value | 7.69 | 9.756 | 5.229 | |

| Jun | 3.594 | 6.806 | 6.391 | 6.190 | No value | 8.553 | 8.551 | 5.816 | |

| Jul | 3.107 | 6.160 | 5.785 | 5.747 | No value | 8.422 | 7.213 | 5.727 | |

| Aug | 2.832 | 5.642 | 5.299 | 5.256 | No value | 7.888 | 6.673 | 5.364 | |

| Sep | 2.687 | 5.098 | 4.788 | 4.640 | No value | 7.066 | 6.705 | 4.805 | |

| Oct | 2.700 | 4.554 | 4.277 | 3.796 | No value | 5.685 | 7.440 | 3.866 | |

| Nov | 2.532 | 3.703 | 3.477 | 2.639 | No value | 4.123 | 7.407 | 2.804 | |

| Dec | 2.242 | 3.039 | 2.854 | 1.932 | No value | 3.214 | 6.537 | 2.186 | |

| Sanalona II | Jan | 2.925 | 3.728 | 3.501 | 2.246 | 1.928 | 3.417 | 7.996 | 2.323 |

| Feb | 3.273 | 4.665 | 4.381 | 3.233 | 2.598 | 4.219 | 8.590 | 2.869 | |

| Mar | 3.706 | 5.816 | 5.462 | 4.433 | 3.570 | 5.251 | 9.354 | 3.571 | |

| Apr | 4.103 | 6.934 | 6.512 | 5.622 | 4.542 | 6.455 | 10.136 | 4.389 | |

| May | 4.221 | 7.494 | 7.038 | 6.338 | 5.396 | 7.530 | 10.390 | 5.120 | |

| Jun | 3.64 | 6.872 | 6.453 | 6.185 | 5.339 | 8.329 | 8.786 | 5.663 | |

| Jul | 3.187 | 6.279 | 5.897 | 5.794 | 4.027 | 8.234 | 7.534 | 5.599 | |

| Aug | 2.925 | 5.790 | 5.437 | 5.345 | 3.629 | 7.790 | 7.011 | 5.297 | |

| Sep | 2.711 | 5.156 | 4.842 | 4.667 | 3.233 | 6.998 | 6.810 | 4.759 | |

| Oct | 2.967 | 4.863 | 4.567 | 3.942 | 2.945 | 5.686 | 8.210 | 3.866 | |

| Nov | 3.022 | 4.136 | 3.884 | 2.755 | 2.298 | 4.144 | 8.654 | 2.818 | |

| Dec | 2.796 | 3.49 | 3.277 | 2.034 | 1.767 | 3.312 | 7.892 | 2.252 | |

| Rosario | Jan | 2.442 | 3.601 | 3.382 | 2.546 | 1.924 | 3.904 | 7.030 | 2.655 |

| Feb | 2.796 | 4.468 | 4.196 | 3.421 | 2.439 | 4.669 | 7.635 | 3.175 | |

| Mar | 3.181 | 5.467 | 5.134 | 4.451 | 3.328 | 5.577 | 8.267 | 3.793 | |

| Apr | 3.465 | 6.320 | 5.935 | 5.391 | 4.058 | 6.602 | 8.687 | 4.490 | |

| May | 3.469 | 6.617 | 6.214 | 5.867 | 4.685 | 7.534 | 8.516 | 5.123 | |

| Jun | 2.987 | 5.978 | 5.614 | 5.566 | 4.676 | 8.137 | 6.973 | 5.533 | |

| Jul | 2.695 | 5.575 | 5.236 | 5.276 | 3.864 | 8.075 | 6.159 | 5.491 | |

| Aug | 2.497 | 5.200 | 4.884 | 4.927 | 3.525 | 7.703 | 5.755 | 5.238 | |

| Sep | 2.235 | 4.559 | 4.282 | 4.287 | 3.199 | 7.000 | 5.322 | 4.760 | |

| Oct | 2.339 | 4.273 | 4.013 | 3.776 | 2.870 | 5.991 | 6.189 | 4.074 | |

| Nov | 2.412 | 3.812 | 3.580 | 2.968 | 2.308 | 4.659 | 6.998 | 3.168 | |

| Dec | 2.300 | 3.362 | 3.157 | 2.372 | 1.816 | 3.847 | 6.809 | 2.616 | |

| Santa Cruz de Alaya | Jan | 2.374 | 3.403 | 3.196 | 2.329 | 2.394 | 3.645 | 6.847 | 2.479 |

| Feb | 2.638 | 4.205 | 3.949 | 3.201 | 3.031 | 4.433 | 7.239 | 3.014 | |

| Mar | 3.034 | 5.246 | 4.926 | 4.285 | 3.932 | 5.452 | 7.932 | 3.707 | |

| Apr | 3.425 | 6.253 | 5.872 | 5.335 | 4.789 | 6.551 | 8.615 | 4.455 | |

| May | 3.600 | 6.787 | 6.374 | 5.963 | 5.366 | 7.492 | 8.869 | 5.095 | |

| Jun | 3.242 | 6.35 | 5.963 | 5.819 | 5.185 | 8.146 | 7.714 | 5.539 | |

| Jul | 2.886 | 5.861 | 5.504 | 5.472 | 4.073 | 8.021 | 6.733 | 5.454 | |

| Aug | 2.619 | 5.367 | 5.040 | 5.024 | 3.634 | 7.587 | 6.170 | 5.159 | |

| Sep | 2.413 | 4.762 | 4.472 | 4.384 | 3.296 | 6.843 | 5.944 | 4.653 | |

| Oct | 2.660 | 4.555 | 4.278 | 3.825 | 3.205 | 5.732 | 7.295 | 3.898 | |

| Nov | 2.603 | 3.859 | 3.624 | 2.806 | 2.801 | 4.339 | 7.629 | 2.950 | |

| Dec | 2.324 | 3.229 | 3.032 | 2.144 | 2.259 | 3.537 | 6.874 | 2.405 | |

| Siqueros | Jan | 2.752 | 3.828 | 3.595 | 2.557 | 2.056 | 3.870 | 7.867 | 2.632 |

| Feb | 3.081 | 4.703 | 4.417 | 3.470 | 2.513 | 4.637 | 8.365 | 3.153 | |

| Mar | 3.463 | 5.728 | 5.380 | 4.541 | 3.232 | 5.557 | 8.950 | 3.779 | |

| Apr | 3.795 | 6.672 | 6.265 | 5.557 | 3.887 | 6.597 | 9.490 | 4.486 | |

| May | 3.829 | 7.048 | 6.619 | 6.108 | 4.450 | 7.531 | 9.462 | 5.121 | |

| Jun | 3.307 | 6.424 | 6.033 | 5.891 | 4.353 | 8.263 | 7.876 | 5.619 | |

| Jul | 3.044 | 6.066 | 5.697 | 5.649 | 3.500 | 8.243 | 7.124 | 5.605 | |

| Aug | 2.863 | 5.707 | 5.359 | 5.305 | 3.093 | 7.868 | 6.794 | 5.351 | |

| Sep | 2.631 | 5.087 | 4.777 | 4.664 | 2.883 | 7.131 | 6.504 | 4.849 | |

| Oct | 2.750 | 4.739 | 4.451 | 4.040 | 2.749 | 6.042 | 7.496 | 4.109 | |

| Nov | 2.788 | 4.143 | 3.890 | 3.053 | 2.313 | 4.632 | 8.163 | 3.150 | |

| Dec | 2.601 | 3.579 | 3.362 | 2.373 | 1.953 | 3.795 | 7.681 | 2.581 | |

| Surutato | Jan | 1.941 | 2.651 | 2.490 | 1.750 | 1.356 | 2.086 | 5.081 | 1.418 |

| Feb | 2.177 | 3.376 | 3.171 | 2.614 | 1.883 | 2.669 | 5.529 | 1.815 | |

| Mar | 2.472 | 4.303 | 4.041 | 3.688 | 2.613 | 3.462 | 6.137 | 2.354 | |

| Apr | 2.85 | 5.372 | 5.045 | 4.828 | 3.342 | 4.485 | 7.018 | 3.050 | |

| May | 3.035 | 6.066 | 5.697 | 5.565 | 3.982 | 5.471 | 7.620 | 3.721 | |

| Jun | 2.640 | 5.753 | 5.403 | 5.471 | 3.866 | 6.345 | 6.803 | 4.315 | |

| Jul | 2.137 | 5.022 | 4.716 | 4.972 | 2.802 | 6.227 | 5.403 | 4.234 | |

| Aug | 2.103 | 4.83 | 4.536 | 4.716 | 2.569 | 5.938 | 5.455 | 4.038 | |

| Sep | 2.050 | 4.392 | 4.125 | 4.113 | 2.269 | 5.246 | 5.587 | 3.567 | |

| Oct | 2.168 | 3.899 | 3.661 | 3.238 | 2.107 | 3.982 | 6.162 | 2.708 | |

| Nov | 2.149 | 3.131 | 2.940 | 2.151 | 1.610 | 2.722 | 5.992 | 1.851 | |

| Dec | 1.929 | 2.533 | 2.379 | 1.553 | 1.217 | 2.049 | 5.179 | 1.393 | |

| Weather station | Shapiro–Wilk (W) | P(normal) |

|---|---|---|

| Culiacán | 0.969 | 0.207 |

| EL Playón | 0.976 | 0.411 |

| Guatenipa | 0.975 | 0.371 |

| Ixpalino | 0.891 | 0.001 |

| La Cruz | 0.905 | 0.001 |

| Mocorito | 0.983 | 0.662 |

| Sanalona II | 0.903 | 0.001 |

| Rosario | 0.940 | 0.013 |

| Santa Cruz de Alaya | 0.940 | 0.013 |

| Siqueros | 0.981 | 0.593 |

| Surutato | 0.952 | 0.042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).