1. Introduction

The increasing demand for sustainable and high-performance materials in engineering has led to extensive research into polymer-based composites, particularly those utilizing epoxy resins due to their adaptability across aerospace, automotive, and defense sectors [

1,

2]. With a focus on environmental sustainability, natural fiber reinforcements such as jute provide a cost-effective means to enhance mechanical properties while reducing environmental impact [

2]. A significant avenue of development is in Multilayer Armor Systems (MAS), where a multi-material approache contributes to ballistic resistance, with potential functionalization for electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding, especially pertinent in the design of ballistic vests and MAS [

3,

4].

Recent advances in defense technology underscore the relevance of such materials, particularly in countering threats posed by directed energy weapons (DEWs). Military technologies such as the such as active denial system (ADS), which rely on concentrated electromagnetic energy to produce disabling heat sensations upon targets highlight the need for composites with strong electromagnetic attenuation properties to protect personnel from both kinetic and non-kinetic threats [

5]. These "future soldiers" will likely require multifunctional protective gear that integrates ballistic resistance with EMI shielding, a combination that provides protection against both physical projectiles and DEW's sources [

6].

Carbon black (CB) emerges as a potent functionalization agent in these contexts, as its inclusion in composites enhances both conductivity and mechanical strength, key factors in achieving superior EMI shielding effectiveness (SE). Due to its electrical conductivity property, 5 vol % of CB loading can reach the percolation threshold, enabling a conductive network that acts as a barrier to electromagnetic waves [

7]. According to Leão et al. [

8], clean polyvinylidene fluoride scrap (rPVDF) composites with 2.7 vol% CB achieved similar AC conductivity to those with 8.3 vol% expanded graphite, underscoring carbon black’s superior efficiency as a conductive filler. Research demonstrates that incorporating CB into various polymer matrices substantially enhances SE. For instance, in an epoxy matrix, absorbance increased from 28% at a 5 wt% CB loading to 67% at 20 wt%, reaching the percolation threshold, after which it decreased to 58% at 25 wt%. Across the 0.1–0.13 GHz frequency range, higher CB concentrations improved conductivity, which in turn boosted absorbance, decreased transmittance, and increased reflectance, achieving up to 22% SE in the C and X bands (4–10 GHz) and 47% absorbance in the same frequency range [

9].

Recent studies underscore the effectiveness of functionalized natural fiber composites in enhancing electromagnetic shielding, particularly when combined with conductive coatings. In one study, hemp fiber coated with electroless Nickel-phosphorus was integrated into carbon fiber epoxy composites, yielding significant EMI shielding improvements across the X-band (8–12 GHz). With one layer of coated hemp fiber, the SE increased from 61.17 dB to 83.16 dB, and a second layer further elevated the SE to 92.77 dB—an increase of 51.66% over the uncoated composite [

11]. Additionally, research on kenaf fiber-reinforced high-density polyethylene composites with and without multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) demonstrated SE values above 30 dB in the X-band at 16% fiber content and 5 wt% MWCNTs, with enhancements in mechanical properties, making them suitable for applications like electronic casings [

12]. Moreover, ramie fiber coated with electroless Nickel-phosphorus and graphene achieved an SE increase from 47.12 dB to 51 dB in the X-band and a 74% rise in conductivity, emphasizing its viability for EMI shielding and energy storage [

13].

This study seeks to expand on these findings by examining the impact of CB within a jute-reinforced epoxy matrix, a composite anticipated to perform well in both ballistic and electromagnetic protection. ANOVA is applied to evaluate variations in tensile strength, absorbed energy, ballistic limit velocity, and SE between functionalized and non-functionalized samples, providing insight into carbon black's role in enhancing multifunctional protective properties. This research underscores the potential of CB-enhanced composites as a sustainable, effective solution for advanced protective applications, particularly relevant for personal protective equipment designed for military and law enforcement use.

3. Results

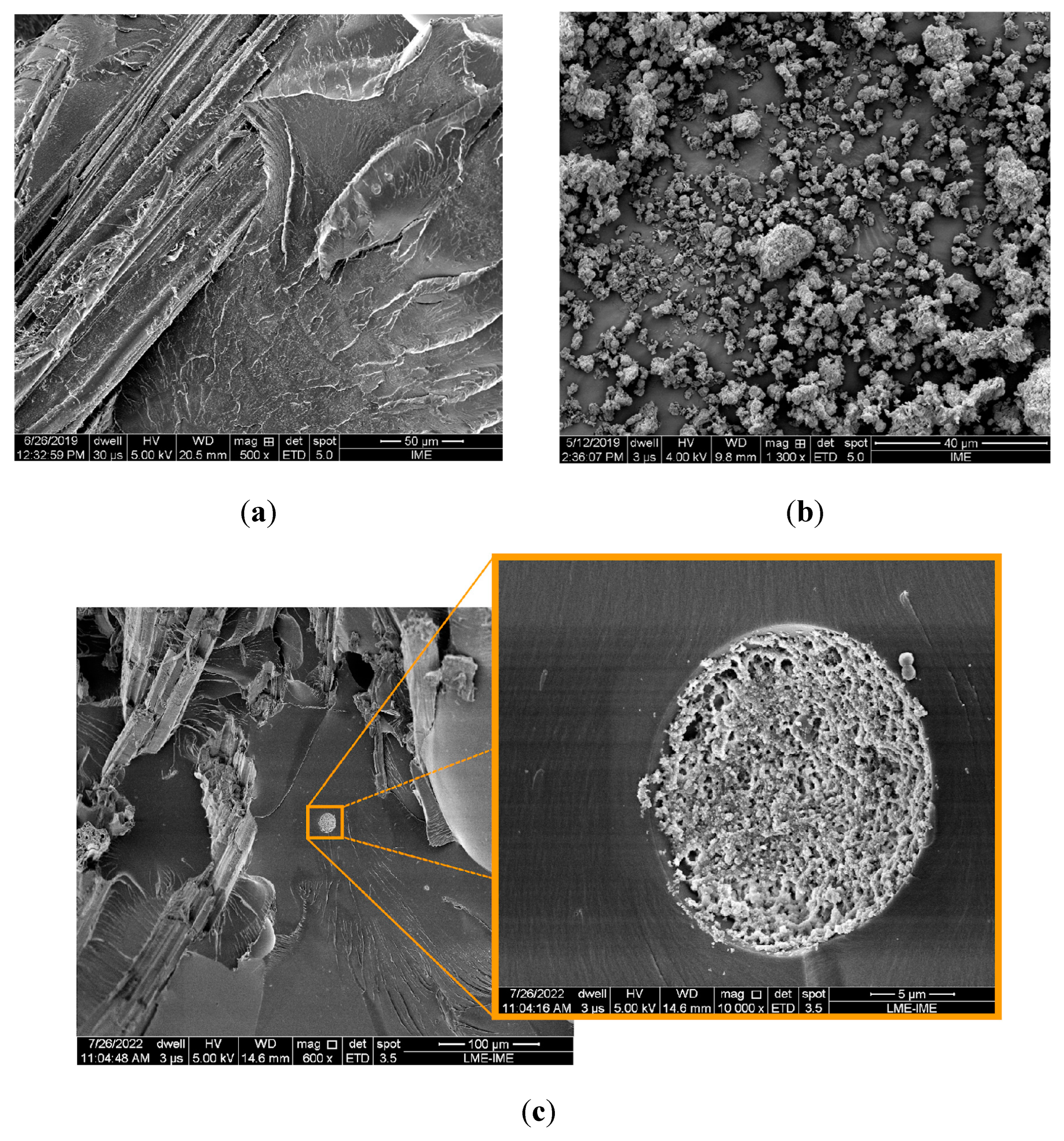

The morphological analysis of epoxy composites reinforced with jute fabric and functionalized with CB revealed significant structural features that may directly impact the material's mechanical and SE properties. EJ30 samples exhibited a surface morphology in the matrix and fibers typical of natural fiber-reinforced composites

Figure 1(a), with expected adhesion between fiber and matrix.

Figure 1(c) shows spheroidal structures distributed throughout the epoxy matrix, resembling the CB particle clusters observed in

Figure 1(b), indicating a morphological similarity. These structures may be associated with the formation of conductive networks due to the presence of CB within the polymer matrix, which creates pathways for electrical conduction [

18].

The morphological characteristics found in

Figure 1(c) are consistent with other micrographs of CB dispersed in a polymer matrix [

18,

19,

20]. The model of electrical conduction by tunneling between CB particles, as described by Balberg [

21], suggests that the proximity between particles generates variable resistance within the material, which depends on the distribution of interparticle distances. This behavior is reflected in the observed structure, where CB-concentrated regions alternate with areas of matrix without CB, resulting in a non-homogeneous conduction system.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the mechanical properties of epoxy resin can be significantly enhanced through reinforcement with natural fibers. According to Zolfakkar et al. [

22], natural fibers contribute to a notable improvement in both tensile strength and modulus of elasticity. As seen by Sathiyamoorthy et al. [

23], CB exhibited a comparable effect in enhancing the mechanical properties of the jute-reinforced composites investigated in this study. The incorporation of 5 vol% CB in the epoxy matrix led to a notable improvement in the mechanical properties of the composites. As shown in

Table 1, the tensile strength and modulus of elasticity increased by 15% for the functionalized composite (EJ30/CB5) compared to the non-functionalized version (EJ30).

The mechanical properties, including tensile strength, elastic modulus, and elongation, were subjected to Weibull analysis and ANOVA. The parameters derived from the Weibull analysis are presented in

Table 2. Based on an initial evaluation, the coefficient of determination (R²) demonstrates a good fit to the data, with values exceeding 0.9. The scale parameter (θ) indicates that, in 63.2% of the cases, the elastic modulus and tensile strength are expected to exceed their mean values. Finally, the shape parameter (β) for all evaluated properties and samples was greater than 1, indicating that the θ values in

Table 2 correspond to an increasing failure rate as the number of tested samples increases [

24,

25].

ANOVA was performed to determine any statistically significant differences in tensile strength and elastic modulus between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5.

Table 3 displays the ANOVA parameters for tensile strength, where an F-test yielded a P-value of 0.179 (greater than 0.05), indicating no significant difference in tensile strength between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 [

24,

25].

Similarly, ANOVA results for elastic modulus in

Table 4 showed a P-value of 0.058, also greater than 0.05, suggesting no significant difference in elastic modulus between functionalized and non-functionalized samples [

24,

25].

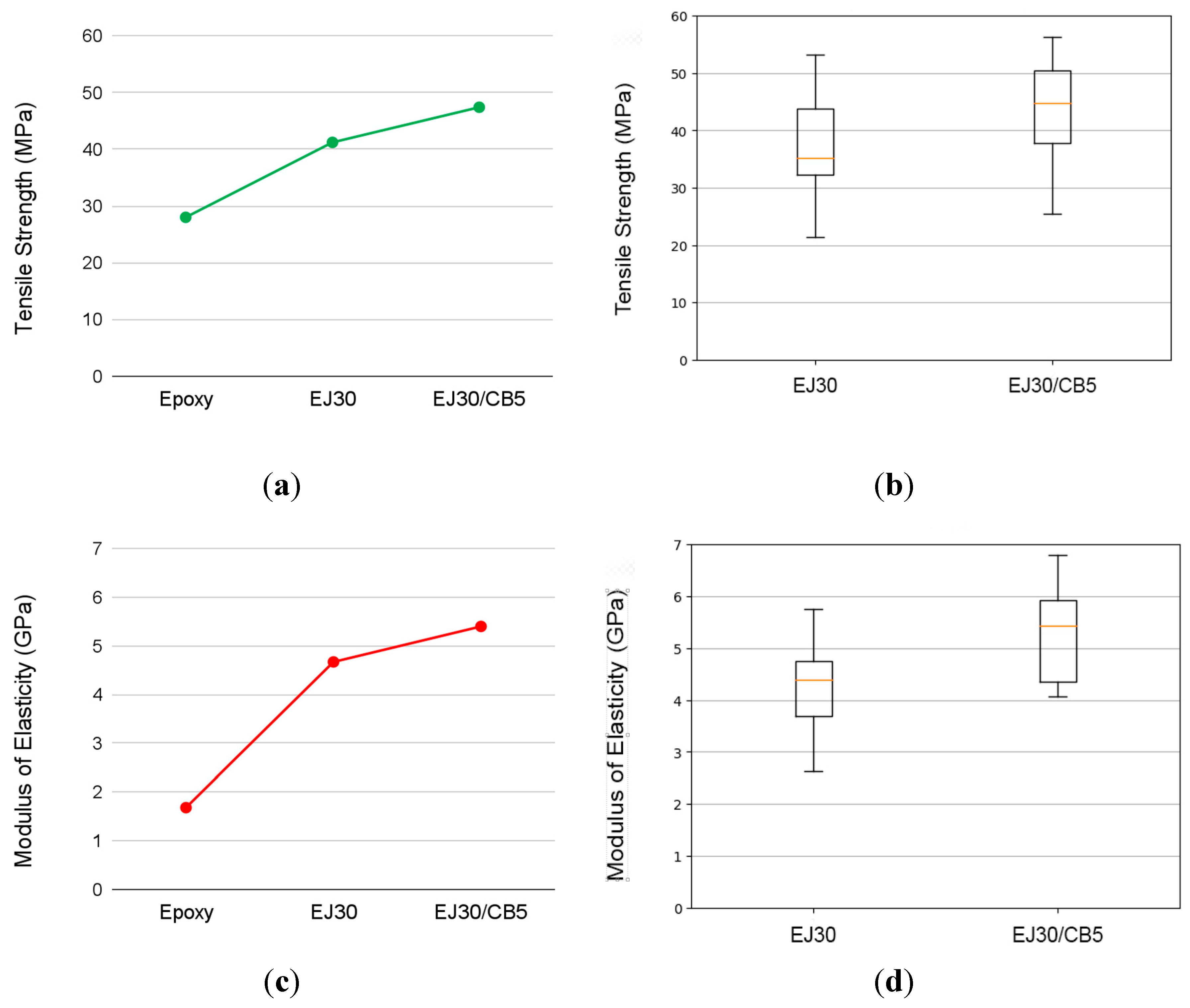

Figure 2 visually represents these statistical results.

Figure 2a,c show mean tensile strength and elastic modulus for neat epoxy compared with EJ30 and EJ30/CB5, while

Figure 2b,d present box-and-whisker plots for these properties. The addition of jute fabric reinforcement (EJ30) enhanced both tensile strength and elastic modulus compared to neat epoxy, as shown in

Figure 2a,c. The addition of CB (EJ30/CB5) slightly improved these properties compared to EJ30 alone. Box-and-whisker plots in

Figure 2b,d show a wide yet similar data distribution between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5, supporting the ANOVA conclusions, particularly for tensile strength (P-value = 0.179). A more dispersed data distribution in elastic modulus for EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 (

Figure 2d) corresponds to the P-value of 0.058.

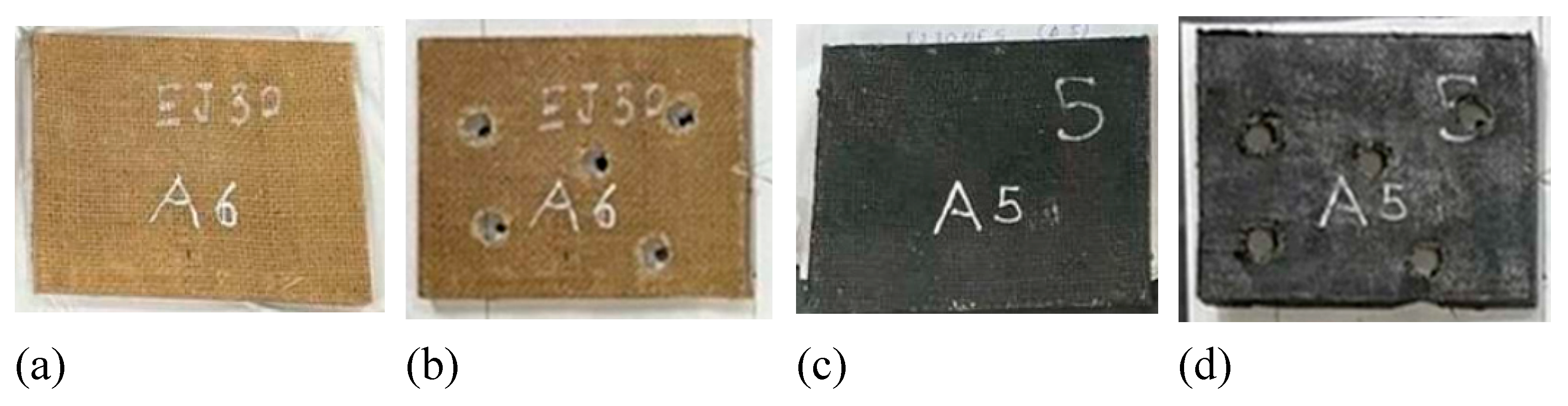

Figure 3 shows the EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples before and after ballistic tests:

Figure 3a,b for EJ30 and

Figure 3c,d for EJ30/CB5. The samples showed adequate spacing between impact sites, and the functionalization with CB produced a color change from beige (EJ30) to black (EJ30/CB5).

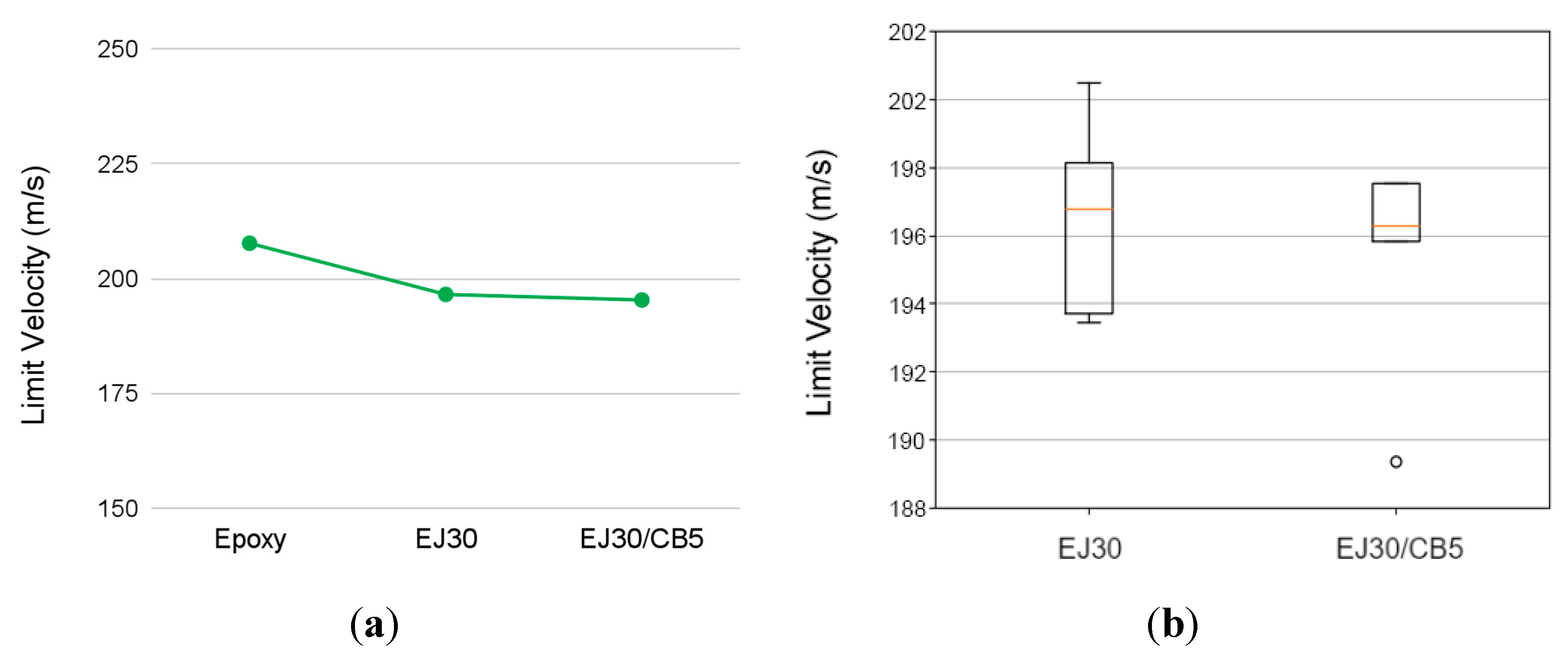

Each reinforcement increment reduced the material’s limit velocity (

) and absorbed energy (

),

Table 5, with a 5.4% reduction in limit velocity and a 10.9% reduction in absorbed energy for EJ30 compared to neat epoxy. Functionalizing EJ30 with 5 vol% CB (EJ30/CB5) led to less than a 1.2% reduction in both limit velocity and absorbed energy.

Table 6 presents Weibull parameters for

and

for EJ30 and EJ30/CB5. Both samples showed β values greater than 1, but only EJ30 had R² values over 0.9, indicating that the Weibull model explains 81% of

variation and 76% of

variation for EJ30/CB5. This suggests that inconsistent CB particle distribution may have impacted the ballistic properties of EJ30/CB5 composites.

The ANOVA results in

Table 7 and

Table 8 indicate no statistically significant differences between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 for

(p = 0.57) and

(p = 0.56), with F-values below 1 in both analyses. This lack of significance suggests that reinforcement with jute fabric and CB did not substantially alter the ballistic parameters measured [

26]. However, it is important to interpret these findings in the context of the mechanisms governing ballistic behavior in polymer composites, as both jute and CB possess characteristics that could influence

and

.

The comparison between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 (

Figure 4) reveals that combining jute and CB creates a hybrid matrix that, while mechanically stronger, does not lead to significant improvements in

and

[

26]. This behavior aligns with the literature on polymer composites, where natural fiber reinforcements and conductive particles impact mechanical and thermal properties but do not necessarily enhance energy dissipation capacity [

27].

Natural fiber composites with conductive fillers are known for their rigidity and impact resistance compared to pure polymer matrices like epoxy. However, the

of reinforced composites depends on the deformation ability of both fibers and matrix, as well as their interface. In this case, interfacial cohesion may have been insufficient to form a high-energy-absorbing matrix, as would be observed in composites reinforced with synthetic fibers like Kevlar, which have optimized structures and interfaces for high-speed impact absorption [

28]

In polymer materials reinforced with carbon fillers, similar to CB, ballistic impact tends to cause less significant matrix deformation, which increases rigidity but limits energy absorption [

29]. This may explain the low F-value for

in

Table 8, even with CB addition, indicating that conductive particles did not significantly improve energy dissipation in this context.

In EJ30/CB5, this CB filler primarily acts as a conductive and reinforcing agent, improving the composite’s mechanical strength and rigidity. CB as an additive that enhances impact resistance and stiffness in composites, though its impact on energy absorption is limited, as its primary function is to increase resistance rather than dissipate energy [

29]. CB in the epoxy matrix promotes slight structural integrity improvement but not enough to cause a significant increase in absorbed energy, as shown by statistical analysis and visually evident in the plots of

Figure 5.

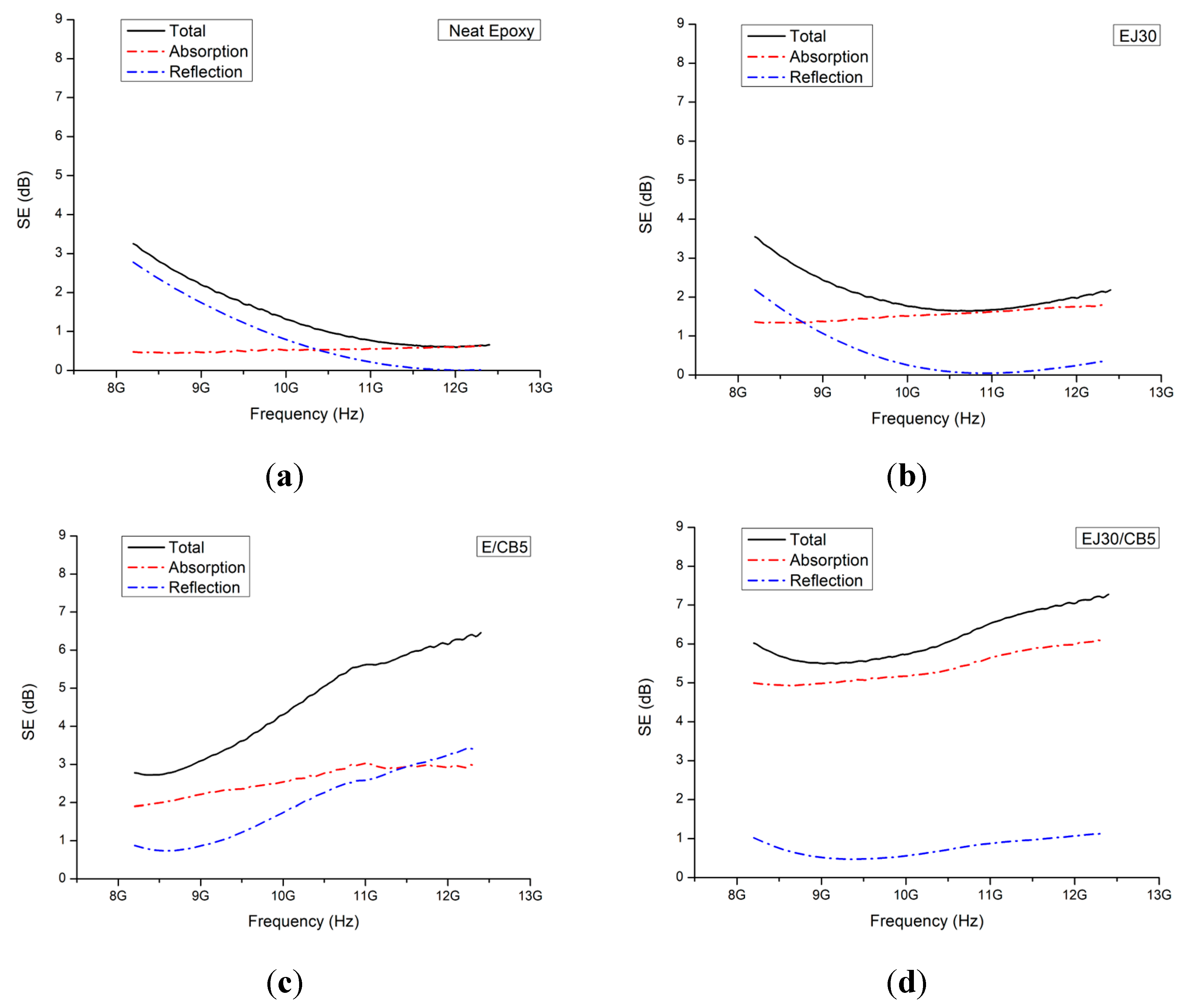

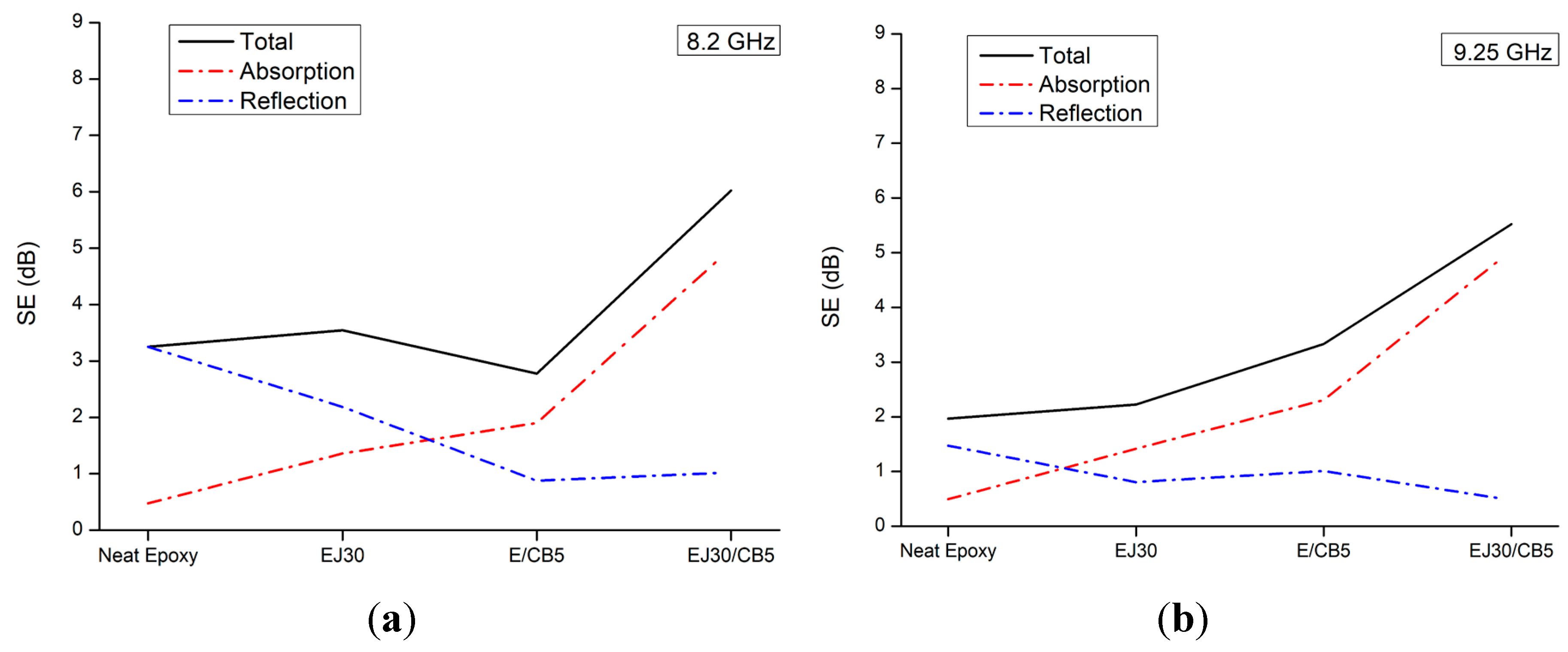

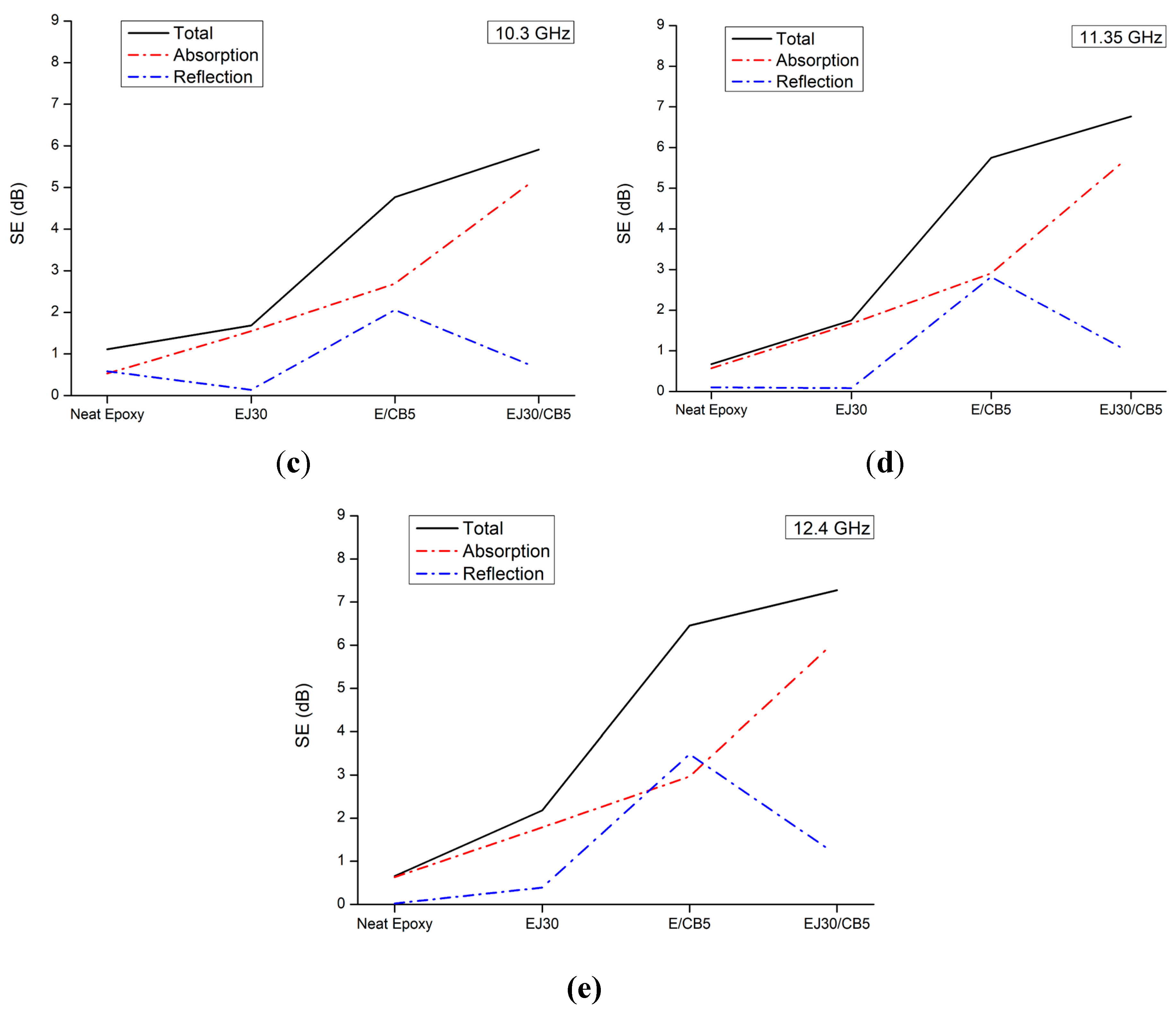

The SE analysis in

Figure 6 for samples reinforced with jute fabric and CB highlights the significant impact of these reinforcements on the composite’s electromagnetic behavior. SE improves with the addition of CB, and the predominant shielding mechanism shifts from reflection to absorption. Furthermore, jute reinforcement, especially in combination with CB, stabilizes SE across the frequency range analyzed, suggesting a possible better shielding effectiveness.

The comparison shows that neat epoxy exhibits low shielding effectiveness SE ~1–2 dB across the frequency range, indicating a predominantly dielectric behavior with minimal absorption. The EJ30 sample shows a slight SE increase ~2–3 dB, suggesting jute fabric alone contributes little to electromagnetic shielding but enhances wave dispersion. In the E/CB5 and EJ30/CB5 samples, SE reaches 5–8 dB, demonstrating that combining jute fabric with CB significantly improves SE.

The SE increase in E/CB5 and EJ30/CB5 due to CB addition aligns with studies showing the role of conductive particles in creating current pathways within the polymer matrix, dissipating electromagnetic energy through absorption mechanisms. According to Bertolini et al. [

30], composites containing CB fillers exhibit higher electrical conductivity and better electromagnetic wave absorption, resulting in higher SE. Similarly, Mondal et al. [

31] demonstrated that adding conductive fillers to a dielectric matrix enhances absorption, as incident waves are converted to heat through current dissipation.

The SE stabilization with jute fabric addition in EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 can be attributed to the structural and dielectric properties of natural fibers, which disperse electromagnetic radiation across a broad frequency range. Natural fibers like jute have a fibrous structure that aids electromagnetic wave dispersion and increases composite mechanical strength, preventing the conductive CB structure from collapsing at high frequencies. Studies by Hou et al. [

32], suggest that combining natural fibers with conductive fillers creates a hybrid structure that provides both mechanical stability and homogeneous conductive particle distribution, enhancing absorption and minimizing SE variations with frequency.

This combination of jute fabric and CB creates a synergistic effect, maintaining high SE across the X-band frequency range. The jute fabric, as a dielectric, supports CB particles, forming a semi-conductive structure. Larguech et al. [

33] study investigated the dielectric properties of a green composite made of Poly(lactic acid) PLA/ Poly(butylene succinate) PBS polymer matrix reinforced with jute fibers, showing that while PBS enhances crystallinity, the addition of jute increases the glass transition temperature and introduces new dielectric relaxations associated with water dipoles and interfacial polarization.

The SE dependence on frequency reveals distinct behavior between neat and CB-containing samples. At higher frequencies (above 10 GHz), CB-containing samples maintain relatively stable SE, while neat epoxy and EJ30 samples exhibit decreasing SE with increasing frequency, characteristic of dielectric materials. This phenomenon is consistent with the dielectric relaxation model, where insufficient polarization at high frequencies reduces shielding capacity [

33].

Figure 7 shows that, for neat epoxy and EJ30, SE shifts from reflection to absorption with increasing frequency. This behavior aligns with polymer composite literature, where reflection is the dominant mechanism at low frequencies due to the base material’s lack of significant conductivity. As frequency increases, the material’s polarization capacity decreases, leading to greater absorption [

32]. At high frequencies, the energy of incident waves is partially dissipated within the polymer matrix, especially in dielectric materials like epoxy.

The E/CB5 sample exhibits an unusual behavior, with its shielding efficiency through reflection increasing with frequency, surpassing absorption at 12.4 GHz. This deviation from typical behavior may be attributed to the structure and distribution of CB particles within the composite. At higher frequencies, the formation of conductive pathways within the composite may enhance the reflection of incident waves instead of allowing full absorption. According to Hou et al. [

32], this phenomenon occurs when the concentration of conductive particles is sufficient to create reflective interfaces but not high enough to form a complete conductive network that would maximize absorption.

Figure 1.

Shows SEM images of (a) the EJ30 sample, (b) the EJ30/CB5 sample, and (c) carbon black as received.

Figure 1.

Shows SEM images of (a) the EJ30 sample, (b) the EJ30/CB5 sample, and (c) carbon black as received.

Figure 2.

Comparative visualization of the average values, with (a) showing tensile strength and (c) elastic modulus for neat epoxy and EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples, alongside box-and-whisker plots for (b) tensile strength and (d) elastic modulus for EJ30 and EJ30/CB5.

Figure 2.

Comparative visualization of the average values, with (a) showing tensile strength and (c) elastic modulus for neat epoxy and EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples, alongside box-and-whisker plots for (b) tensile strength and (d) elastic modulus for EJ30 and EJ30/CB5.

Figure 3.

Images of EJ30 before (a) and after (b) impact and EJ30/CB5 before (c) and after (d) impact.

Figure 3.

Images of EJ30 before (a) and after (b) impact and EJ30/CB5 before (c) and after (d) impact.

Figure 4.

Comparison plots showing (a) the mean limit velocity values for neat epoxy, EJ30, and EJ30/CB5, and (b) box-and-whisker plots for the limit velocity values of EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples.

Figure 4.

Comparison plots showing (a) the mean limit velocity values for neat epoxy, EJ30, and EJ30/CB5, and (b) box-and-whisker plots for the limit velocity values of EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples.

Figure 5.

Comparison plots showing (a) the mean absorbed energy values for neat epoxy, EJ30, and EJ30/CB5, and (b) box-and-whisker plots for the absorbed energy values of EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples.

Figure 5.

Comparison plots showing (a) the mean absorbed energy values for neat epoxy, EJ30, and EJ30/CB5, and (b) box-and-whisker plots for the absorbed energy values of EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples.

Figure 6.

Shielding effectiveness (SE) for (a) Neat Epoxy, (b) EJ30, (c) E/CB5, and (d) EJ30/CB5.

Figure 6.

Shielding effectiveness (SE) for (a) Neat Epoxy, (b) EJ30, (c) E/CB5, and (d) EJ30/CB5.

Figure 7.

Shielding effectiveness (SE) of the samples at specific frequencies: (a) 8.2 GHz, (b) 9.25 GHz, (c) 10.3 GHz, (d) 11.35 GHz, and (e) 12.4 GHz.

Figure 7.

Shielding effectiveness (SE) of the samples at specific frequencies: (a) 8.2 GHz, (b) 9.25 GHz, (c) 10.3 GHz, (d) 11.35 GHz, and (e) 12.4 GHz.

Table 1.

The tensile strength and elastic modulus for different natural fiber-reinforced epoxy composites.

Table 1.

The tensile strength and elastic modulus for different natural fiber-reinforced epoxy composites.

| Material Description |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Modulus of Elasticity (MPa) |

| Epoxy + Jute (EJ30) |

37.51 |

4262.69 |

| Epoxy + Jute + Carbon Black (EJ30/CB5) |

43.18 |

4927.33 |

Table 2.

Weibull parameters for the mechanical properties of EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 composites.

Table 2.

Weibull parameters for the mechanical properties of EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 composites.

| |

EJ30 |

E30J/CB5 |

| |

β |

θ |

R2

|

β |

θ |

R2 |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) |

4.25 |

41.21 |

0.97 |

4.38 |

47.40 |

0.97 |

| Extension (%) |

4.66 |

1.17 |

0.94 |

3.82 |

1.17 |

0.98 |

| Modulus of elasticity (MPa) |

4.49 |

4667.15 |

0.97 |

4.50 |

5397.10 |

0.91 |

Table 3.

Tensile strength for EJ30 e EJ30/CB5 composites.

Table 3.

Tensile strength for EJ30 e EJ30/CB5 composites.

Causes of

Variation |

Degrees of

Freedom |

Sum of

Squares |

Mean

Square |

F-Value |

P-Value |

| Treatments |

1.0 |

177.102 |

177.102 |

1.939 |

0.179 |

| Residual |

20.0 |

1826.753 |

91.337 |

|

|

| Total |

21 |

2003.855 |

|

|

|

Table 4.

Elastic modulus for EJ30 e EJ30/CB5 composites.

Table 4.

Elastic modulus for EJ30 e EJ30/CB5 composites.

Causes of

Variation |

Degrees of

Freedom |

Sum of

Squares |

Mean

Square |

F-Value |

P-Value |

| Treatments |

1 |

4.118 |

4.118 |

4.252 |

0.058 |

| Residual |

14 |

13.559 |

0.9685 |

|

|

| Total |

15 |

17.677 |

|

|

|

Table 5.

Mean limit velocity and absorbed energy for neat epoxy and EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples.

Table 5.

Mean limit velocity and absorbed energy for neat epoxy and EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples.

| Materials |

(m/s) |

(J) |

Reference |

| Epoxy |

207.67 ± 2.02 |

316.63 ± 6.78 |

PW* |

| EJ30 |

196.52 ± 2.99 |

282.14 ± 9.07 |

PW* |

| EJ30/CB5 |

195.31 ± 3.42 |

278.59 ± 9.21 |

PW* |

Table 6.

Weibull parameters for the EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples in terms of their ballistic performance regarding Limit Velocity and Absorbed Energy.

Table 6.

Weibull parameters for the EJ30 and EJ30/CB5 samples in terms of their ballistic performance regarding Limit Velocity and Absorbed Energy.

| |

EJ30 |

E30J/CB5 |

|

| |

β |

θ |

R2

|

β |

θ |

R2 |

|

| Limit Velocity (m/s) |

64.70 |

198.00 |

0.90 |

|

52.89 |

197.1 |

0.81 |

| Absorbed Energy (J) |

31.82 |

286.40 |

0.98 |

|

26.75 |

283.62 |

0.76 |

Table 7.

ANOVA results for Limit Velocity between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5.

Table 7.

ANOVA results for Limit Velocity between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5.

Causes of

Variation |

Degrees of

Freedom |

Sum of

Squares |

Mean

Square |

F-Value |

P-Value |

| Treatments |

1 |

3.66 |

3.66 |

0.35 |

0.57 |

| Residual |

8 |

82.53 |

10.32 |

|

|

| Total |

9 |

86.19 |

|

|

|

Table 8.

ANOVA results for Absorbed Energy between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5.

Table 8.

ANOVA results for Absorbed Energy between EJ30 and EJ30/CB5.

Causes of

Variation |

Degrees of

Freedom |

Sum of

Squares |

Mean

Square |

F-Value |

P-Value |

| Treatments |

1 |

3.66 |

3.66 |

0.35 |

0.57 |

| Residual |

8 |

82.53 |

10.32 |

|

|

| Total |

9 |

86.19 |

|

|

|