Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

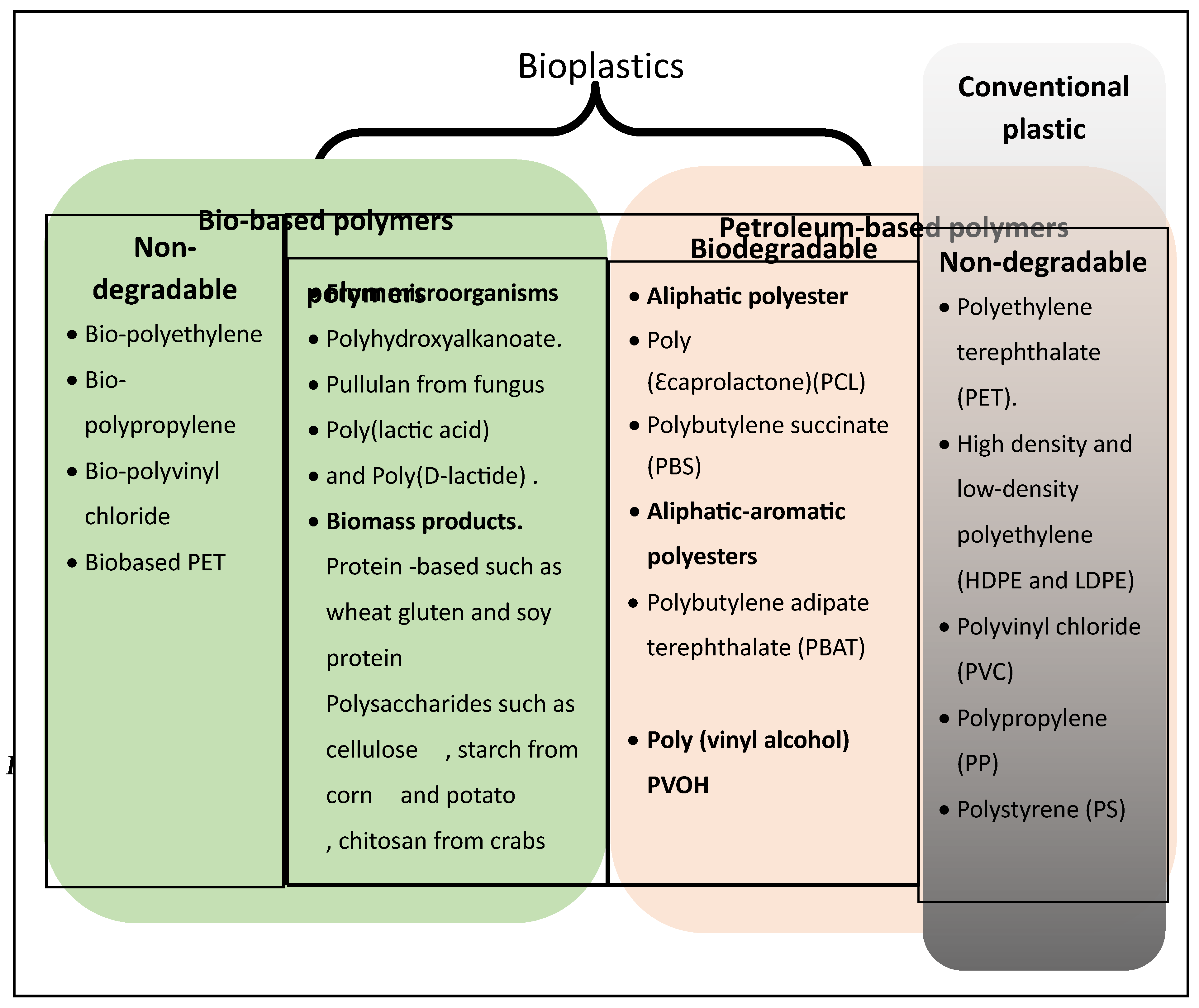

Bioplastics

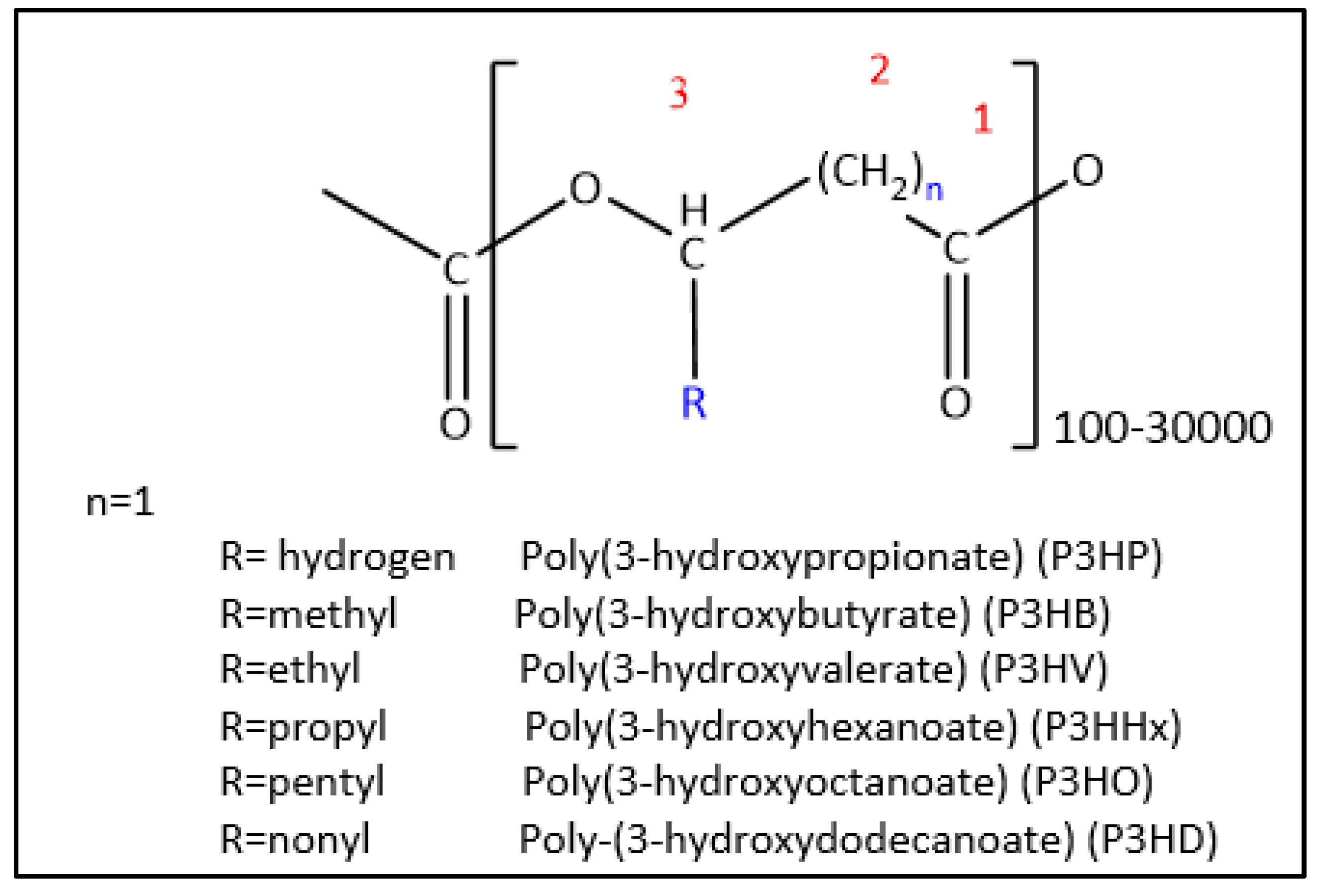

Classification, Thermophysical Characteristics and Advantages of PHAs

- Less CO2 emissions and sustainability [18].

- The industrial production has a low safety risk compared to petroleum-based plastic production which includes flammable and toxic by-products [18].

- Waste water is non-toxic [18].

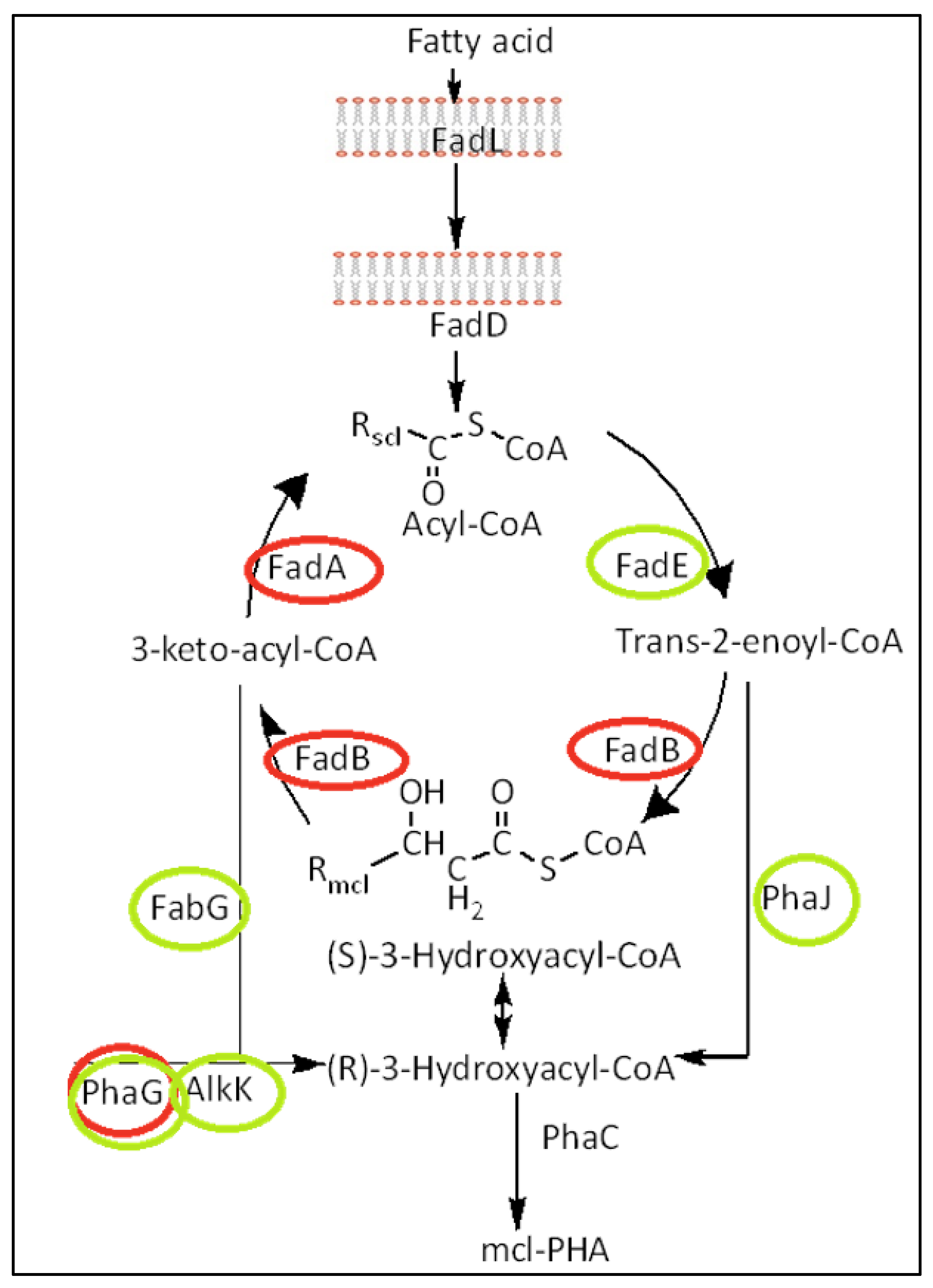

Metabolic Pathways and Metabolic Engineering to Optimize Medium-Chain-Length (mcl) PHAs Cell Production

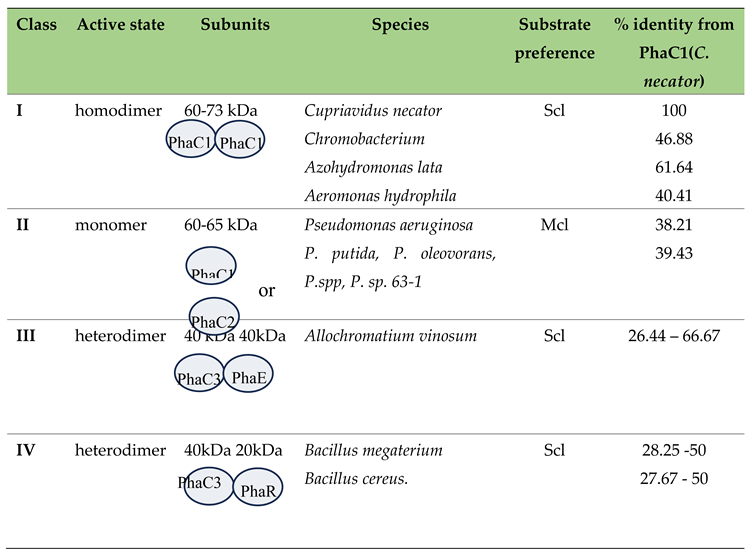

PHA synthase (PhaC)

Classification

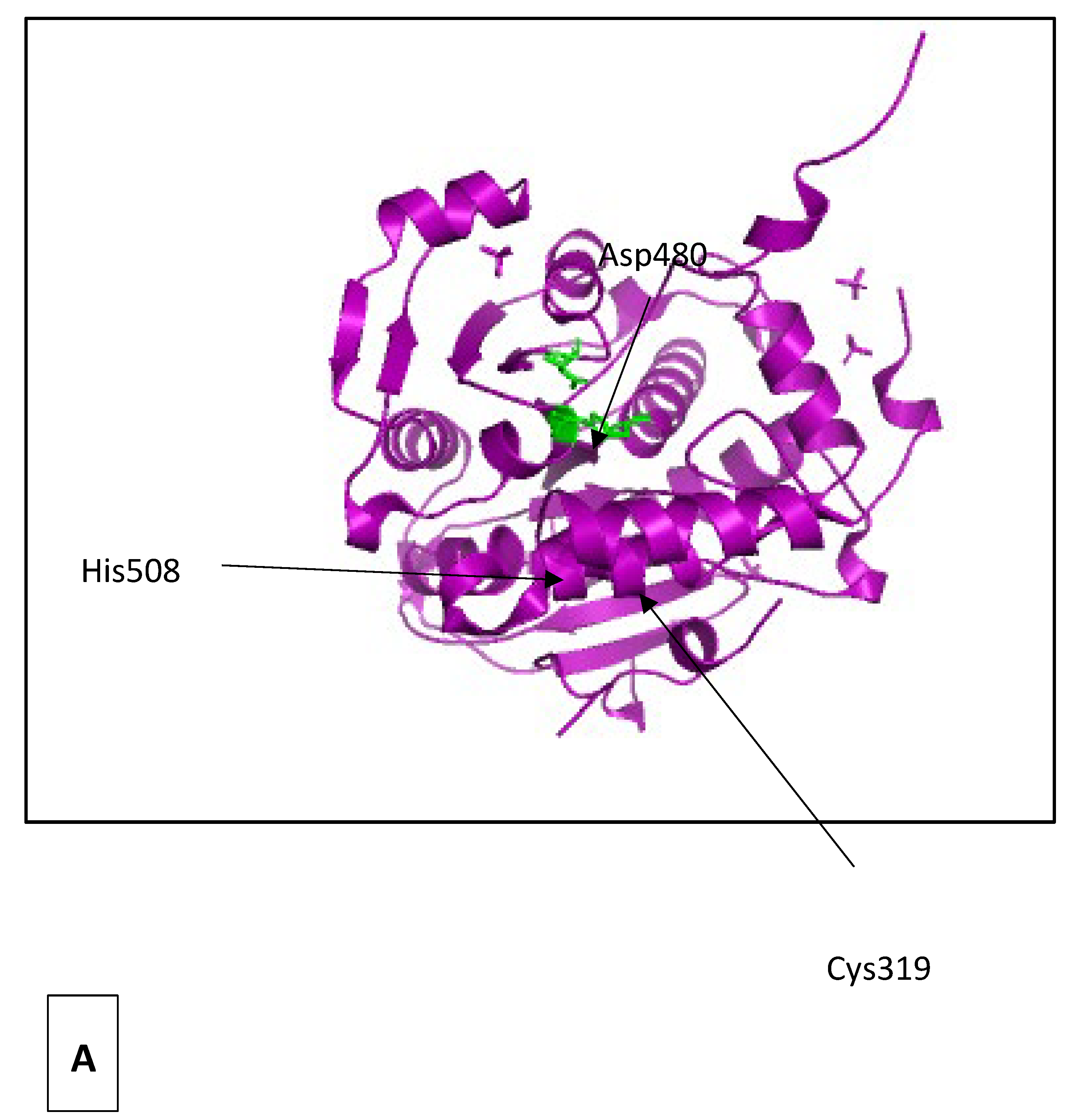

Structure and Sequence

Substrate Specificity and Kinetics

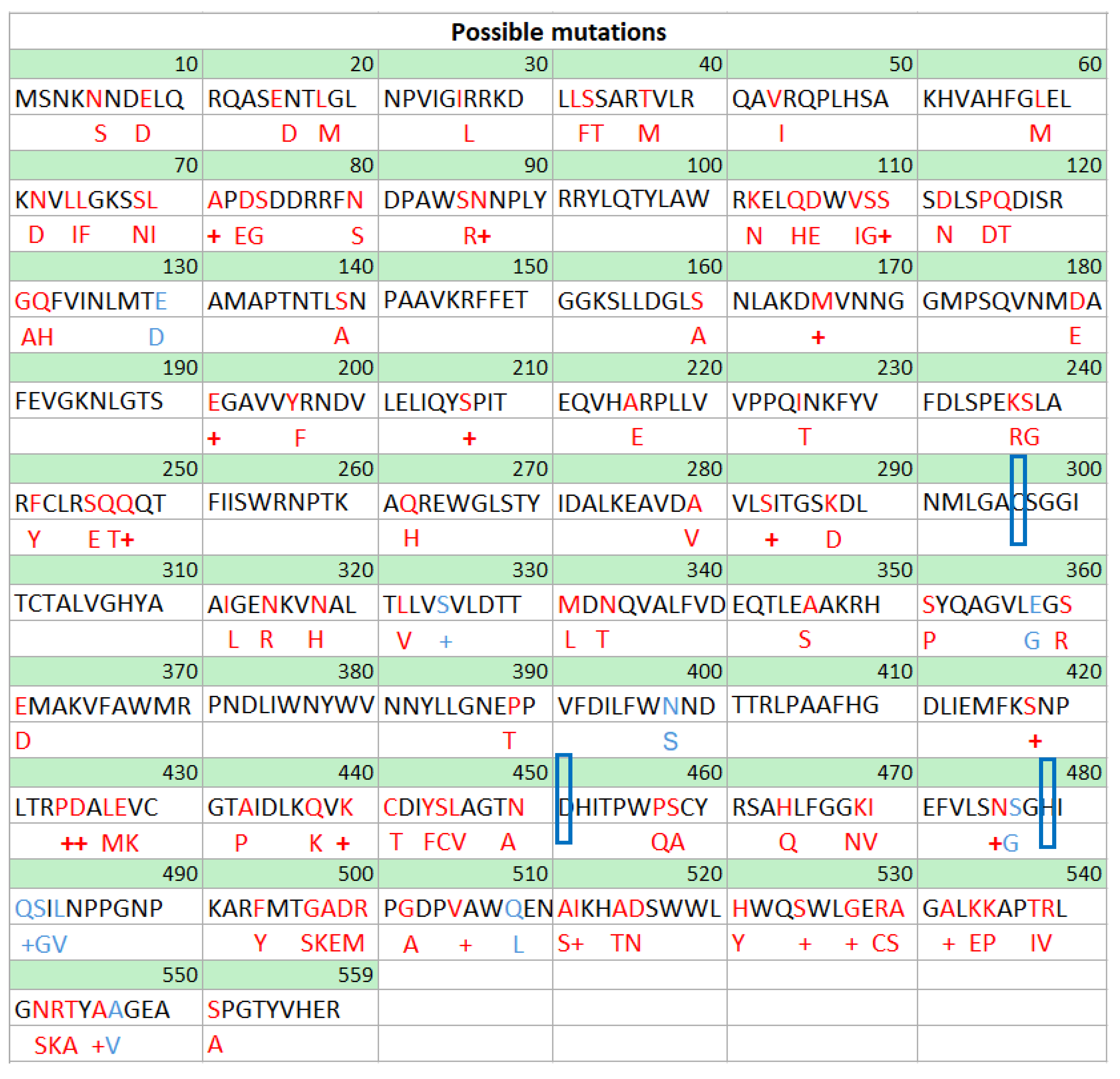

Point Mutations that Might Affect Substrate Specificity

Protein Engineering for Catalytic Enhancement

Methods to Evaluate the Enzymatic Activity

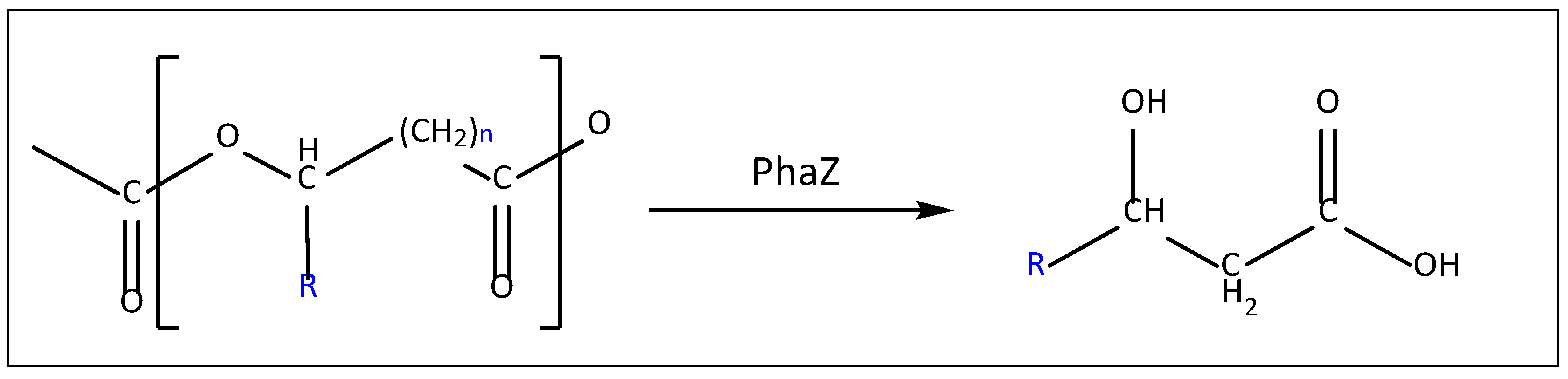

PHA Depolymerase (PhaZ)

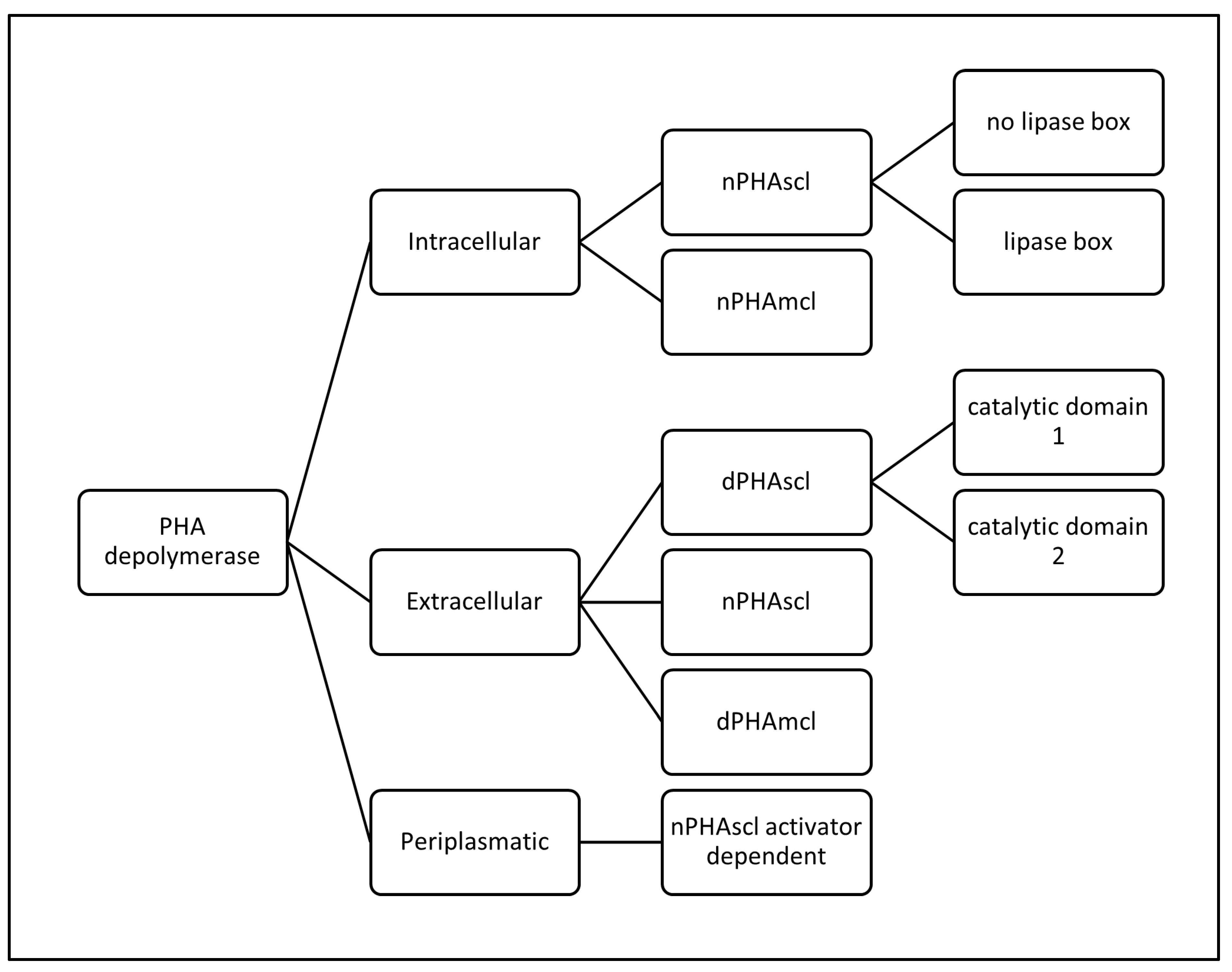

Classification

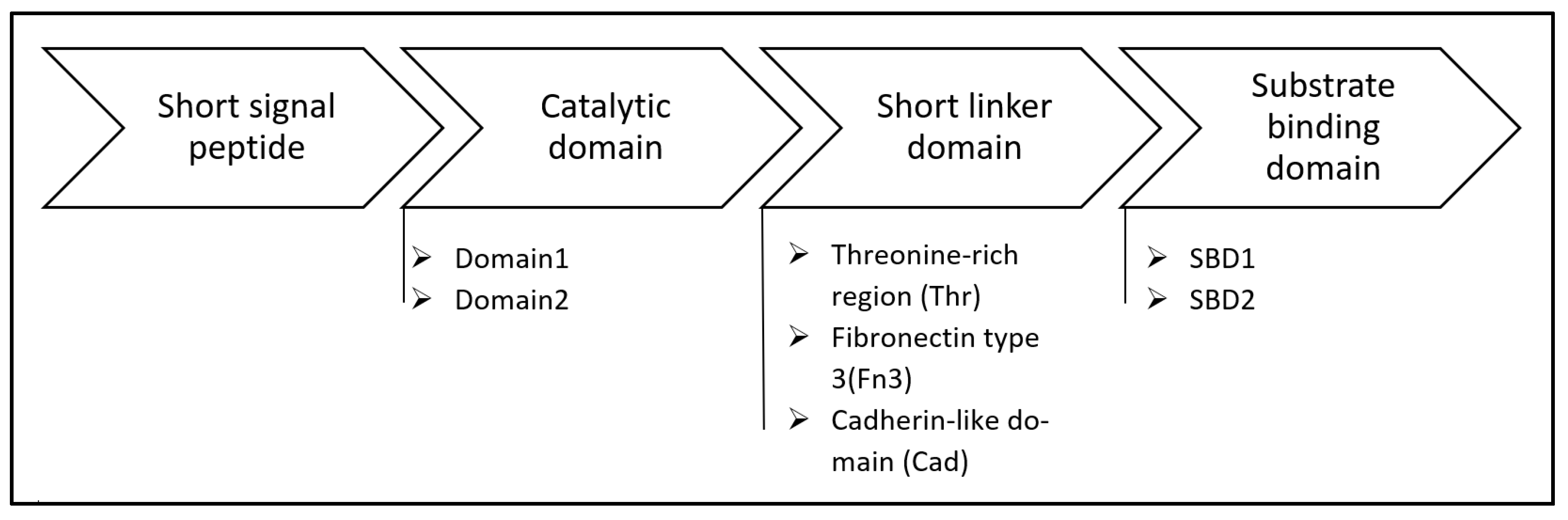

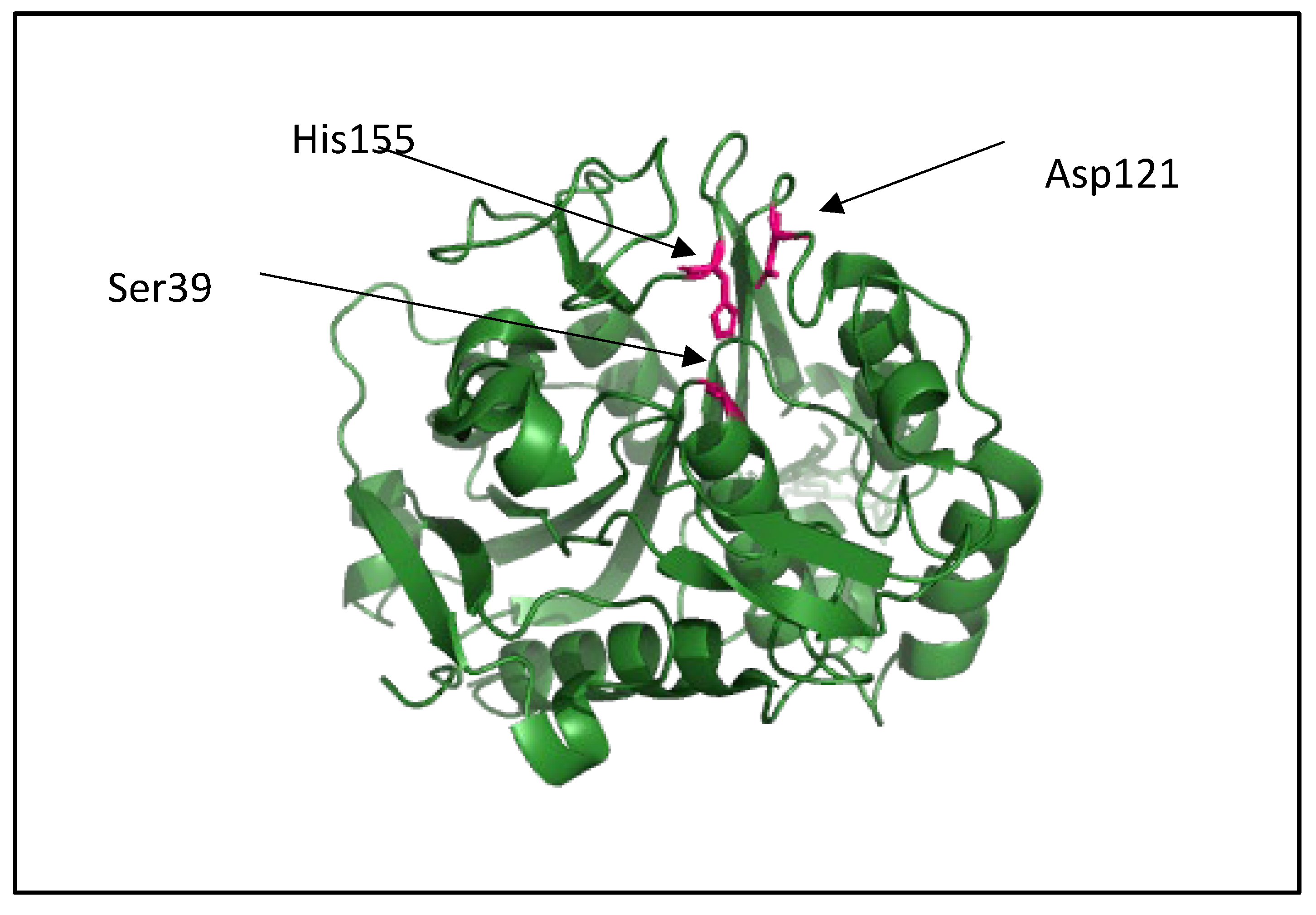

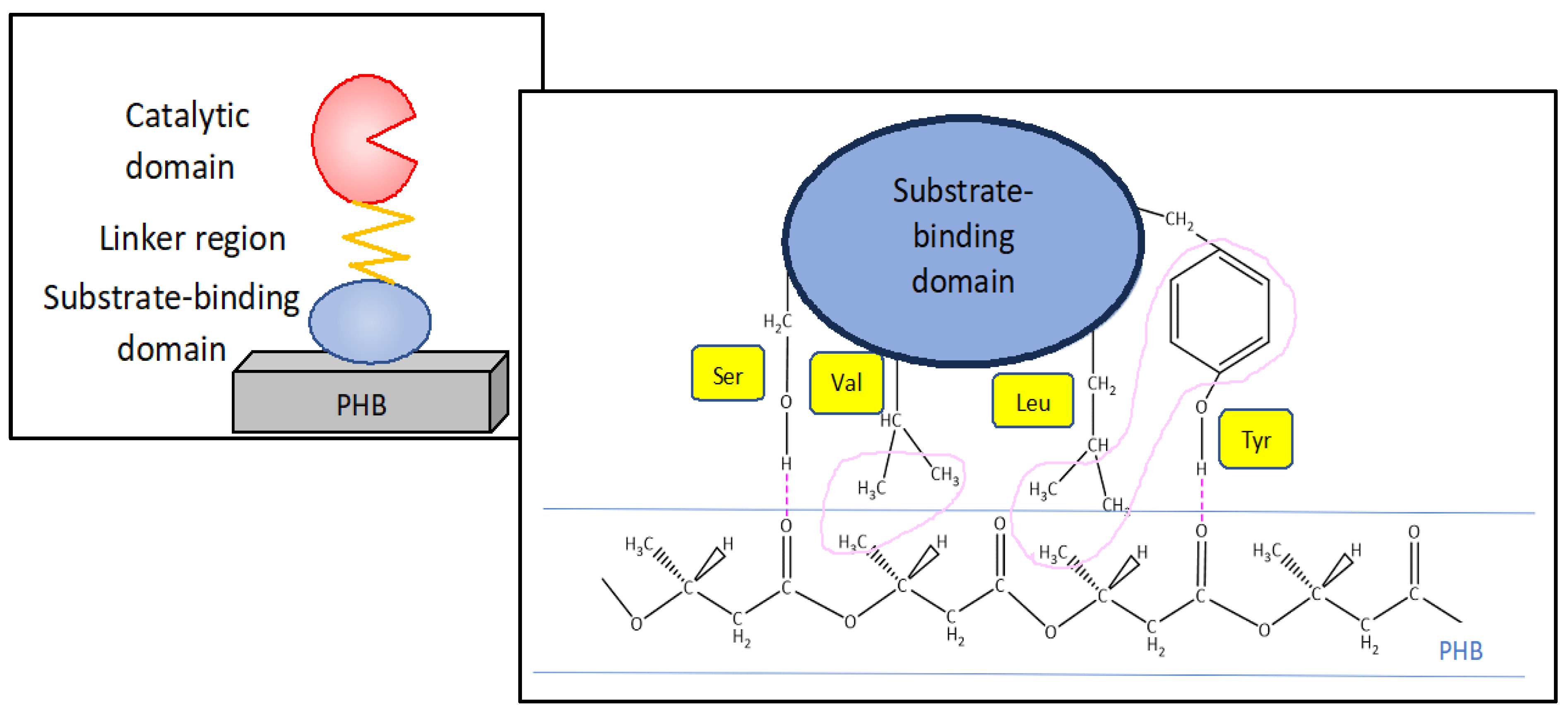

Structure and Sequence

Substrate Specificity and Kinetics

Protein Engineering for Catalytic Enhancement

Methods to Evaluate the Enzymatic Activity

Lipases Capable of Degrading PHAs

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Statements and Declarations

References

- Hazenberg W and Witholt B (1997) Efficient production of medium-chain-length poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) from octane by Pseudomonas oleovorans: economic considerations, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 48, 5: 588-596. [CrossRef]

- Lenz R W and Marchessault R H (2005) Bacterial Polyesters: Biosynthesis, Biodegradable Plastics and Biotechnology, Biomacromolecules, 6, 1: 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Stainer W R, Kunisawa R, and Contopoulou B (1959) The role of organic substrates in bacterial photosynthesis, Proceedings Natl. Acad. Science, 45: 1246-1260. [CrossRef]

- Poli A, Di Donato P, Abbamondi G R, and Nicolaus B (2011) Synthesis, Production, and Biotechnological Applications of Exopolysaccharides and Polyhydroxyalkanoates by Archaea, Archaea, 2011, 1: 693253. [CrossRef]

- Lemoigne M (1926) Produits de deshydration et de polymerisation de l’acide B-oxybutyric, The Bulletin de la Société Chimique de France 8: 770-778.

- Jendrossek D and Handrick R (2002) Microbial Degradation of Polyhydroxyalkanoates, Annual Review of Microbiology, 56, 1: 403-432. [CrossRef]

- Steinbüchel A and Valentin H E (1995) Diversity of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acids, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 128, 3: 219-228. [CrossRef]

- Gao X, Chen J-C, Wu Q, and Chen G-Q (2011) Polyhydroxyalkanoates as a source of chemicals, polymers, and biofuels, Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 22, 6: 768-774. [CrossRef]

- Reddy C S K, Ghai R, Rashmi, and Kalia V C (2003) Polyhydroxyalkanoates: an overview, Bioresource Technology, 87, 2: 137-146. [CrossRef]

- Samui A B and Kanai T (2019) Polyhydroxyalkanoates based copolymers, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 140: 522-537. [CrossRef]

- Grigore M E, Grigorescu R M, Iancu L, Ion R-M, Zaharia C, and Andrei E R (2019) Methods of synthesis, properties and biomedical applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates: a review, Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition, 30, 9: 695-712. [CrossRef]

- Pandey A, Adama N, Adjallé K, and Blais J-F (2022) Sustainable applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates in various fields: A critical review, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 221: 1184-1201. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan D, Aristya Ganies R, Lin Y-J, Chang J-J, Yen H-W, and Chang J-S (2021) Microbial cell factories for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates, Essays in Biochemistry, 65, 2: 337-353. [CrossRef]

- Rehm B H A (2003) Polyester synthases: natural catalysts for plastics, Biochemical Journal, 376, 1: 15-33. [CrossRef]

- Lee S Y (1996) Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates, Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 49, 1: 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Steinbüchel A and Lütke-Eversloh T (2003) Metabolic engineering and pathway construction for biotechnological production of relevant polyhydroxyalkanoates in microorganisms, Biochemical Engineering Journal, 16, 2: 81-96. [CrossRef]

- Knoll M, Hamm T M, Wagner F, Martinez V, and Pleiss J (2009) The PHA Depolymerase Engineering Database: A systematic analysis tool for the diverse family of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) depolymerases, BMC Bioinformatics, 10, 1: 89. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Yin J, and Chen G-Q (2014) Polyhydroxyalkanoates, challenges and opportunities, Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 30: 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Atiwesh G, Mikhael A, Parrish C C, Banoub J, and Le T-A T (2021) Environmental impact of bioplastic use: A review, Heliyon, 7, 9: e07918. [CrossRef]

- Fredi G and Dorigato A (2021) Recycling of bioplastic waste: A review, Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 4, 3: 159-177. [CrossRef]

- Bioplastics E. “European Bioplastics e.V.” https://www.european-bioplastics.org/bioplastics/ (accessed 11th March, 2024, 2024).

- Bhagwat G et al. (2020) Benchmarking Bioplastics: A Natural Step Towards a Sustainable Future, Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 28, 12: 3055-3075. [CrossRef]

- Das M, Manda B, and Katiyar V, Sustainable routes for synthesis of poly (ε-caprolactone): Prospects in chemical industries. Singapore: Springer, 2020.

- Patni N, Yadava P, Agarwal A, and Maroo V (2014) An overview on the role of wheat gluten as a viable substitute for biodegradable plastics, 30, 4: 421-430. [CrossRef]

- Hardin T. “Plastic: It’s Not All the Same.” Copyright © Plastic Oceans International. https://plasticoceans.org/7-types-of-plastic/ (accessed February, 2024).

- Zhou Y, He Y, Lin X, Feng Y, and Liu M (2022) Sustainable, High-Performance, and Biodegradable Plastics Made from Chitin, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 14, 41: 46980-46993. [CrossRef]

- Chen G-Q, Chen X-Y, Wu F-Q, and Chen J-C (2020) Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) toward cost competitiveness and functionality, Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 3, 1: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Jian J, Xiangbin Z, and Xianbo H (2020) An overview on synthesis, properties and applications of poly(butylene-adipate-co-terephthalate)–PBAT, Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 3, 1: 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Rishi V, Sandhu A K, Kaur A, Kaur J, Sharma S, and Soni S K (2020) Utilization of kitchen waste for production of pullulan to develop biodegradable plastic, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 104, 3: 1307-1317. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Wang L, Gardner D J, Shaler S M, and Cai Z (2021) Towards a cellulose-based society: opportunities and challenges, Cellulose, 28, 8: 4511-4543. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghita R, Gutt G, and Amariei S, “The Use of Edible Films Based on Sodium Alginate in Meat Product Packaging: An Eco-Friendly Alternative to Conventional Plastic Materials,” Coatings, vol. 10, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- Guilbert S, Morel M-H, Gontard N, and Cuq B, “Protein-Based Plastics and Composites as Smart Green Materials,” in Feedstocks for the Future, vol. 921, (ACS Symposium Series, no. 921): American Chemical Society, 2006, ch. 24, pp. 334-350. [CrossRef]

- Merino D, Paul U C, and Athanassiou A (2021) Bio-based plastic films prepared from potato peels using mild acid hydrolysis followed by plasticization with a polyglycerol, Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 29: 100707. [CrossRef]

- Baker M I, Walsh S P, Schwartz Z, and Boyan B D (2012) A review of polyvinyl alcohol and its uses in cartilage and orthopedic applications, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 100B, 5: 1451-1457. [CrossRef]

- Jalabert M, Fraschini C, and Prud’homme R E (2007) Synthesis and characterization of poly(L-lactide)s and poly(D-lactide)s of controlled molecular weight, Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry, 45, 10: 1944-1955. [CrossRef]

- Patnaik S, Panda A K, and Kumar S (2020) Thermal degradation of corn starch based biodegradable plastic plates and determination of kinetic parameters by isoconversional methods using thermogravimetric analyzer, Journal of the Energy Institute, 93, 4: 1449-1459. [CrossRef]

- Li G et al., “Synthesis and Biological Application of Polylactic Acid,” Molecules, vol. 25, no. 21. [CrossRef]

- Siracusa V and Blanco I, “Bio-Polyethylene (Bio-PE), Bio-Polypropylene (Bio-PP) and Bio-Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (Bio-PET): Recent Developments in Bio-Based Polymers Analogous to Petroleum-Derived Ones for Packaging and Engineering Applications,” Polymers, vol. 12, no. 8. [CrossRef]

- Barletta M et al. (2022) Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS): Materials, processing, and industrial applications, Progress in Polymer Science, 132: 101579. [CrossRef]

- Mohanan N, Montazer Z, Sharma P K, and Levin D B (2020) Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of Synthetic Plastics, (in English), Frontiers in Microbiology, Review 11. [CrossRef]

- Telmo O, “Polymers and the Environment,” in Polymer Science, Y. Faris Ed. Rijeka: IntechOpen, 2013, p. Ch. 1.

- Dilkes-Hoffman L S, Lant P A, Laycock B, and Pratt S (2019) The rate of biodegradation of PHA bioplastics in the marine environment: A meta-study, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 142: 15-24. [CrossRef]

- Rudnik E, “11 - Biodegradability Testing of Compostable Polymer Materials,” in Handbook of Biopolymers and Biodegradable Plastics, S. Ebnesajjad Ed. Boston: William Andrew Publishing, 2013, pp. 213-263.

- worldometer. “Oil left in the world.” https://www.worldometers.info/oil/#:~:text=The%20world%20has%20proven%20reserves,(at%20current%20consumption%20levels) (accessed October 29, 2024, 2024).

- Rajendran N and Han J (2022) Techno-economic analysis of food waste valorization for integrated production of polyhydroxyalkanoates and biofuels, Bioresource Technology, 348: 126796. [CrossRef]

- Statita. “Statista. Price of high-density polyethylene worldwide from 2017 to 2023.” https://www.statista.com/statistics/1171074/price-high-density-polyethylene-forecast-globally/ (accessed.

- Choi J and Lee S Y (1999) Factors affecting the economics of polyhydroxyalkanoate production by bacterial fermentation, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 51, 1: 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Technavio, “Top 6 vendors in the polyhydroxyalkanoate market from 2017 to 2021:Technavio,” 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170824005079/en/Top-6-Vendors-Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Market-2017-2021.

- Kourmentza C et al. (2017) Recent Advances and Challenges towards Sustainable Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Production, Bioengineering, 4, 2. [CrossRef]

- Jiang G et al. (2016) Carbon Sources for Polyhydroxyalkanoates and an Integrated Biorefinery, (in eng), Int J Mol Sci, 17, 7: 1157. [CrossRef]

- Bio-on. “Bio-on.” http://www.bio-on.it/production.php#p9 (accessed october 17, 2019).

- Danimerscientific. “Danimer scientific.” https://danimerscientific.com/pha-the-future-of-biopolymers/pha-culture-manufacturing/ (accessed october 17, 2019).

- TianAn. “TianAn Biopolymer.” http://www.tianan-enmat.com/index.html# (accessed october 17, 2019).

- TianjinGreenBio. “Tiajin GreenBio Materials.” http://www.tjgreenbio.com/en/about.aspx?title=About%20GreenBio&cid=25 (accessed october 17, 2019).

- Chen G-Q (2009) A microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) based bio- and materials industry, Chemical Society Reviews. 8: 2434-2446. [CrossRef]

- Ray S, “Mass Multiplication, Production Cost Analysis and Marketing of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs),” in Industrial Microbiology Based Entrepreneurship: Making Money from Microbes, N. Amaresan, D. Dharumadurai, and D. R. Cundell Eds. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2022, pp. 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Jabeen N, Majid I, and Nayik G A (2015) Bioplastics and food packaging: A review, Cogent Food & Agriculture, 1, 1: 1117749. [CrossRef]

- Noda I, Green P R, Satkowski M M, and Schechtman L A (2005) Preparation and Properties of a Novel Class of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Copolymers, Biomacromolecules, 6, 2: 580-586. [CrossRef]

- Samrot A V, Avinesh R B, Sukeetha S D, and Senthilkumar P (2011) Accumulation of Poly[(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates] in Enterobacter cloacae SU-1 During Growth with Two Different Carbon Sources in Batch Culture, Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 163, 1: 195-203. [CrossRef]

- Kessler B, Weusthius R, Witholt B, and Eggink G (2001) Production of microbial polyesters: fermentation and downstream processes, Advances in Biochemical Engineering/ Biotechnology, 71: 159-82. [CrossRef]

- Evans D A (2014) History of the Harvard ChemDraw Project, Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 53, 42: 11140-11145. [CrossRef]

- Olivera E R, Arcos M, Naharro G, and Luengo J M, “Unusual PHA Biosynthesis,” in Plastics from Bacteria: Natural Functions and Applications, G. G.-Q. Chen Ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010, pp. 133-186. [CrossRef]

- Chen G-Q and Wu Q (2005) Microbial production and applications of chiral hydroxyalkanoates, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 67, 5: 592-599. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Chung A, and Chen G-Q (2017) Synthesis of Medium-Chain-Length Polyhydroxyalkanoate Homopolymers, Random Copolymers, and Block Copolymers by an Engineered Strain of Pseudomonas entomophila, Advanced Healthcare Materials, 6, 7: 1601017. [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Tappel R, and Nomura C (2009) Mini-Review: Biosynthesis of Poly(hydroxyalkanoates), Journal of Macromolecular Science®, Part C: Polymer Reviews: 226-248. [CrossRef]

- Matsusaki H, Abe H, and Doi Y (2000) Biosynthesis and Properties of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyalkanoates) by Recombinant Strains of Pseudomonas sp. 61-3, Biomacromolecules, 1, 1: 17-22. [CrossRef]

- Tsuge T, Hyakutake M, and Mizuno K (2015) Class IV polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthases and PHA-producing Bacillus, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 99, 15: 6231-6240. [CrossRef]

- Altschul S F et al. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs, Nucleic Acids Research, 25, 17: 3389-3402. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z et al. (2019) Domain-centric dissection and classification of prokaryotic poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthases, bioRxiv: 693432. [CrossRef]

- Thomson N, Roy I, Summers D, and Sivaniah E (2010) In vitro production of polyhydroxyalkanoates: achievements and applications, Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 85, 6: 760-767. [CrossRef]

- Antonio R V, Steinbüchel A, and Rehm B H A (2000) Analysis of in vivo substrate specificity of the PHA synthase from Ralstonia eutropha: formation of novel copolyesters in recombinant Escherichia coli, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 182, 1: 111-117. [CrossRef]

- Wong P A L, Chua H, Lo W, Lawford H G, and Yu P H (2002) Production of specific copolymers of polyhydroxyalkanoates from industrial waste, Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, journal article 98, 1: 655-662. [CrossRef]

- Aragao G M F, Lindley N D, Uribelarrea J L, and Pareilleux A (1996) Maintaining a controlled residual growth capacity increases the production of polyhydroxyalkanoate copolymers by Alcaligenes eutrophus, Biotechnology Letters, 18, 8: 937-942. [CrossRef]

- Bates F S and Fredrickson G H (1990) Block Copolymer Thermodynamics: Theory and Experiment, Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 41, 1: 525-557. [CrossRef]

- Mantzaris N V, Kelley A S, Daoutidis P, and Srienc F (2002) A population balance model describing the dynamics of molecular weight distributions and the structure of PHA copolymer chains, Chemical Engineering Science, 57, 21: 4643-4663. [CrossRef]

- Muthuraj R, Valerio O, and Mekonnen T H (2021) Recent developments in short- and medium-chain- length Polyhydroxyalkanoates: Production, properties, and applications, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 187: 422-440. [CrossRef]

- Pereira J R et al. (2019) Demonstration of the adhesive properties of the medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate produced by Pseudomonas chlororaphis subsp. aurantiaca from glycerol, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 122: 1144-1151. [CrossRef]

- Panaitescu D M et al. (2017) Medium Chain-Length Polyhydroxyalkanoate Copolymer Modified by Bacterial Cellulose for Medical Devices, Biomacromolecules, 18, 10: 3222-3232. [CrossRef]

- Ansari S, Sami N, Yasin D, Ahmad N, and Fatma T (2021) Biomedical applications of environmental friendly poly-hydroxyalkanoates, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 183: 549-563. [CrossRef]

- Sun J, Dai Z, Zhao Y, and Chen G-Q (2007) In vitro effect of oligo-hydroxyalkanoates on the growth of mouse fibroblast cell line L929, Biomaterials, 28, 27: 3896-3903. [CrossRef]

- Rai R, Keshavarz T, Roether J A, Boccaccini A R, and Roy I (2011) Medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoates, promising new biomedical materials for the future, Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports, 72, 3: 29-47. [CrossRef]

- Xu X-Y et al. (2010) The behaviour of neural stem cells on polyhydroxyalkanoate nanofiber scaffolds, Biomaterials, 31, 14: 3967-3975. [CrossRef]

- Chamas A et al. (2020) Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 8, 9: 3494-3511. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M et al. (2020) Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates: Opportunities, challenges, and prospects, Journal of Cleaner Production, 263: 121500. [CrossRef]

- Chen J-Y, Song G, and Chen G-Q (2006) A lower specificity PhaC2 synthase from Pseudomonas stutzeri catalyses the production of copolyesters consisting of short-chain-length and medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoates, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 89, 1: 157-167. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Zhang J, Wu Q, and Chen G-Q (2003) Enhanced production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) via manipulating the fatty acid β-oxidation pathway in E. coli, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 221, 1: 97-101. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Luo G, Zhou X R, and Chen G-Q (2011) Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxydecanoate) and 3-hydroxydodecanoate dominating polyhydroxyalkanoates by β-oxidation pathway inhibited Pseudomonas putida, Metabolic Engineering, 13, 1: 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Meng D-C and Chen G-Q, “Synthetic Biology of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA),” in Synthetic Biology – Metabolic Engineering, H. Zhao and A.-P. Zeng Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 147-174. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X J, Sun Z, Ramsay J A, and Ramsay B A (2013) Fed-batch production of MCL-PHA with elevated 3-hydroxynonanoate content, AMB Express, 3, 1: 50. [CrossRef]

- Vo M T, Lee K-W, Jung Y-M, and Lee Y-H (2008) Comparative effect of overexpressed phaJ and fabG genes supplementing (R)-3-hydroxyalkanoate monomer units on biosynthesis of mcl-polyhydroxyalkanoate in Pseudomonas putida KCTC1639, Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 106, 1: 95-98. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Sánchez A, Rathinasabapathy A, López-Cuellar M d R, Vergara-Porras B, and Pérez-Guevara F (2020) Biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates from vegetable oil under the co-expression of fadE and phaJ genes in Cupriavidus necator, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 164: 1600-1607. [CrossRef]

- Budde C F, Riedel S L, Willis L B, Rha C, and Sinskey A J (2011) Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from plant oil by engineered Ralstonia eutropha strains, (in eng), Applied and environmental microbiology, 77, 9: 2847-2854. [CrossRef]

- Wong Y-M, Brigham C J, Rha C, Sinskey A J, and Sudesh K (2012) Biosynthesis and characterization of polyhydroxyalkanoate containing high 3-hydroxyhexanoate monomer fraction from crude palm kernel oil by recombinant Cupriavidus necator, Bioresource Technology, 121: 320-327. [CrossRef]

- Fukui T, Abe H, and Doi Y (2002) Engineering of Ralstonia eutropha for Production of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from Fructose and Solid-State Properties of the Copolymer, Biomacromolecules, 3, 3: 618-624. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia S K et al. (2018) Production of (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) copolymer from coffee waste oil using engineered Ralstonia eutropha, Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 41, 2: 229-235. [CrossRef]

- Agnew D E, Stevermer A K, Youngquist J T, and Pfleger B F (2012) Engineering Escherichia coli for production of C12–C14 polyhydroxyalkanoate from glucose, Metabolic Engineering, 14, 6: 705-713. [CrossRef]

- Park S J, Park J P, and Lee S Y (2002) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates rich in specific monomers, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 214, 2: 217-222. [CrossRef]

- Tan H T, Chek M F, Lakshmanan M, Foong C P, Hakoshima T, and Sudesh K (2020) Evaluation of BP-M-CPF4 polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase on the production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from plant oil using Cupriavidus necator transformants, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 159: 250-257. [CrossRef]

- Salvachúa D et al. (2020) Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for increased polyhydroxyalkanoate production from lignin, Microbial Biotechnology, 13, 1: 290-298. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi L, Wu L-P, Chen J, and Chen G-Q (2012) Synthesis of Diblock copolymer poly-3-hydroxybutyrate -block-poly-3-hydroxyhexanoate [PHB-b-PHHx] by a β-oxidation weakened Pseudomonas putida KT2442, (in eng), Microbial cell factories, 11: 44-44. [CrossRef]

- Li M et al. (2019) Engineering Pseudomonas entomophila for synthesis of copolymers with defined fractions of 3-hydroxybutyrate and medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoates, Metabolic Engineering, 52: 253-262. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang S-P et al. (2007) Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates with High 3-Hydroxydodecanoate Monomer Content by fadB and fadA Knockout Mutant of Pseudomonas putida KT2442, Biomacromolecules, 8, 8: 2504-2511. [CrossRef]

- Zhao F et al. (2020) Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01 for enhanced production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates with enriched content of the dominant monomer, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 154: 1596-1605. [CrossRef]

- Liu W and Chen G-Q (2007) Production and characterization of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate with high 3-hydroxytetradecanoate monomer content by fadB and fadA knockout mutant of Pseudomonas putida KT2442, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 76, 5: 1153-1159. [CrossRef]

- Wang L et al. (2019) Bioinformatics Analysis of Metabolism Pathways of Archaeal Energy Reserves, Scientific Reports, 9, 1: 1034. [CrossRef]

- Lane C E and Benton M G (2015) Detection of the enzymatically-active polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase subunit gene, phaC, in cyanobacteria via colony PCR, Molecular and Cellular Probes, 29, 6: 454-460. [CrossRef]

- Blunt W, Levin D B, and Cicek N, “Bioreactor Operating Strategies for Improved Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Productivity,” Polymers, vol. 10, no. 11. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Filho E R, Gomez J G C, Taciro M K, and Silva L F (2021) Burkholderia sacchari (synonym Paraburkholderia sacchari): An industrial and versatile bacterial chassis for sustainable biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates and other bioproducts, Bioresource Technology, 337: 125472. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Filho E R et al. (2022) Engineering Burkholderia sacchari to enhance poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) [P(3HB-co-3HHx)] production from xylose and hexanoate, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 213: 902-914. [CrossRef]

- Mezzolla V, D’Urso F O, and Poltronieri P (2018) Role of PhaC Type I and Type II Enzymes during PHA Biosynthesis, Polymers, 10, 8. [CrossRef]

- Chen J-Y, Liu T, Zheng Z, Chen J-C, and Chen G-Q (2006) Polyhydroxyalkanoate synthases PhaC1 and PhaC2 from Pseudomonas stutzeri 1317 had different substrate specificities, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 234, 2: 231-237. [CrossRef]

- Bhubalan K et al. (2011) Characterization of the Highly Active Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthase of <span class="named-content genus-species" id="named-content-1">Chromobacterium</span> sp. Strain USM2, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77, 9: 2926. [CrossRef]

- Trakunjae C et al., “Biosynthesis of P(3HB-co-3HHx) Copolymers by a Newly Engineered Strain of Cupriavidus necator PHB−4/pBBR_CnPro-phaCRp for Skin Tissue Engineering Application,” Polymers, vol. 14, no. 19. [CrossRef]

- Wittenborn E C, Jost M, Wei Y, Stubbe J, and Drennan C L (2016) Structure of the Catalytic Domain of the Class I Polyhydroxybutyrate Synthase from Cupriavidus necator, (in eng), J Biol Chem, 291, 48: 25264-25277. [CrossRef]

- Nambu Y, Ishii-Hyakutake M, Harada K, Mizuno S, and Tsuge T (2019) Expanded Amino Acid Sequence of the PhaC Box in the Active Center of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthases, FEBS Letters, n/a, n/a. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Yasuo T, Lenz R W, and Goodwin S (2000) Kinetic and Mechanistic Characterization of the Polyhydroxybutyrate Synthase from Ralstonia eutropha, Biomacromolecules, 1, 2: 244-251. [CrossRef]

- PyMOL. (2020). [Online]. Available: http://www.pymol.org/pymol.

- Yuan W et al. (2001) Class I and III Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthases from Ralstonia eutropha and Allochromatium vinosum: Characterization and Substrate Specificity Studies, Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 394, 1: 87-98. [CrossRef]

- Liu M-H, Chen Y, Jr., and Lee C-Y (2018) Characterization of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis by Pseudomonas mosselii TO7 using crude glycerol, Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 82, 3: 532-539. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Jr., Huang Y-C, and Lee C-Y (2014) Production and characterization of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates by Pseudomonas mosselii TO7, Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 118, 2: 145-152. [CrossRef]

- Licciardello G, Catara A F, and Catara V, “Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Extracellular Products Using Pseudomonas Corrugata and P. Mediterranea: A Review,” Bioengineering, vol. 6, no. 4. [CrossRef]

- Licciardello G et al. (2017) Transcriptome analysis of Pseudomonas mediterranea and P. corrugata plant pathogens during accumulation of medium-chain-length PHAs by glycerol bioconversion, New Biotechnology, 37: 39-47. [CrossRef]

- Solaiman D K Y, Ashby R D, and Foglia T A (2002) Physiological Characterization and Genetic Engineering of Pseudomonas corrugata for Medium-Chain-Length Polyhydroxyalkanoates Synthesis from Triacylglycerols, Current Microbiology, 44, 3: 189-195. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P K, Fu J, Zhang X, Fristensky B, Sparling R, and Levin D B (2014) Genome features of Pseudomonas putida LS46, a novel polyhydroxyalkanoate producer and its comparison with other P. putida strains, AMB Express, 4, 1: 37. [CrossRef]

- Cerrone F et al. (2014) Medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate (mcl-PHA) production from volatile fatty acids derived from the anaerobic digestion of grass, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 98, 2: 611-620. [CrossRef]

- Zhao F et al. (2019) Screening of endogenous strong promoters for enhanced production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates in Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01, Scientific Reports, 9, 1: 1798. [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Duan J, Geng W, Feng J, Wang S, and Song C (2013) Comparison of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates synthases from Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01 with the same substrate specificity, Microbiological Research, 168, 4: 231-237. [CrossRef]

- Pereira J R et al. (2021) Production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates by Pseudomonas chlororaphis subsp. aurantiaca: Cultivation on fruit pulp waste and polymer characterization, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 167: 85-92. [CrossRef]

- Meneses L, Craveiro R, Jesus A R, Reis M A M, Freitas F, and Paiva A, “Supercritical CO2 Assisted Impregnation of Ibuprofen on Medium-Chain-Length Polyhydroxyalkanoates (mcl-PHA),” Molecules, vol. 26, no. 16. [CrossRef]

- Shen X-W, Shi Z-Y, Song G, Li Z-J, and Chen G-Q (2011) Engineering of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase PhaC2Ps of Pseudomonas stutzeri via site-specific mutation for efficient production of PHA copolymers, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 91, 3: 655-665. [CrossRef]

- Kraak M N, Kessler B, and Witholt B (1997) In vitro Activities of Granule-Bound Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxyalkanoate] Polymerase C1 of Pseudomonas oleovorans, European Journal of Biochemistry, 250, 2: 432-439. [CrossRef]

- Weimer A, Kohlstedt M, Volke D C, Nikel P I, and Wittmann C (2020) Industrial biotechnology of Pseudomonas putida: advances and prospects, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 104, 18: 7745-7766. [CrossRef]

- Fontaine P, Mosrati R, and Corroler D (2017) Medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoates biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida mt-2 is enhanced by co-metabolism of glycerol/octanoate or fatty acids mixtures, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 98: 430-435. [CrossRef]

- Le Meur S, Zinn M, Egli T, Thöny-Meyer L, and Ren Q (2012) Production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates by sequential feeding of xylose and octanoic acid in engineered Pseudomonas putida KT2440, BMC Biotechnology, 12, 1: 53. [CrossRef]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos,, J. B, and K. a M, T.L. (2009) BLAST+: architecture and applications., BMC Bioinformatics, 10, 421.: 421. [CrossRef]

- Tsuge T et al. (2005) Biosynthesis of Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Copolymer from Fructose Using Wild-Type and Laboratory-Evolved PHA Synthases, Macromolecular Bioscience, 5, 2: 112-117. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Jr., Tsai P-C, Hsu C-H, and Lee C-Y (2014) Critical residues of class II PHA synthase for expanding the substrate specificity and enhancing the biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate, Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 56: 60-66. [CrossRef]

- Hiroe A, Watanabe S, Kobayashi M, Nomura C T, and Tsuge T (2018) Increased synthesis of poly(3-hydroxydodecanoate) by random mutagenesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 102, 18: 7927-7934. [CrossRef]

- Takase K, Taguchi S, and Doi Y (2003) Enhanced Synthesis of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) in Recombinant Escherichia coli by Means of Error-Prone PCR Mutagenesis, Saturation Mutagenesis, and In Vitro Recombination of the Type II Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthase Gene, The Journal of Biochemistry, 133, 1: 139-145. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto K i, Takase K, Yamamoto Y, Doi Y, and Taguchi S (2009) Chimeric Enzyme Composed of Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Synthases from Ralstonia eutropha and Aeromonas caviae Enhances Production of PHAs in Recombinant Escherichia coli, Biomacromolecules, 10, 4: 682-685. [CrossRef]

- Yang T H, Jung Y K, Kang H O, Kim T W, Park S J, and Lee S Y (2011) Tailor-made type II Pseudomonas PHA synthases and their use for the biosynthesis of polylactic acid and its copolymer in recombinant Escherichia coli, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 90, 2: 603-614. [CrossRef]

- Yang T H et al. (2010) Biosynthesis of polylactic acid and its copolymers using evolved propionate CoA transferase and PHA synthase, Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 105, 1: 150-160. [CrossRef]

- Ren Y, Meng D, Wu L, Chen J, Wu Q, and Chen G-Q (2017) Microbial synthesis of a novel terpolyester P(LA-co-3HB-co-3HP) from low-cost substrates, Microbial Biotechnology, 10, 2: 371-380. [CrossRef]

- Shozui F et al. (2010) A New Beneficial Mutation in Pseudomonas sp. 61-3 Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Synthase for Enhanced Cellular Content of 3-Hydroxybutyrate-Based PHA Explored Using Its Enzyme Homolog as a Mutation Template, Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 74, 8: 1710-1712. [CrossRef]

- Chuah J-A et al. (2013) Characterization of Site-Specific Mutations in a Short-Chain-Length/Medium-Chain-Length Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthase: In Vivo and In Vitro Studies of Enzymatic Activity and Substrate Specificity, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 79, 12: 3813-3821. [CrossRef]

- Seng Wong T and Lan Tee K, Springer, Ed. A Practical Guide to Protein Engineering. 2020.

- Tsuge T (2016) Fundamental factors determining the molecular weight of polyhydroxyalkanoate during biosynthesis, Polymer Journal, 48, 11: 1051-1057. [CrossRef]

- Zou H, Shi M, Zhang T, Li L, Li L, and Xian M (2017) Natural and engineered polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthase: key enzyme in biopolyester production, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 101, 20: 7417-7426. [CrossRef]

- Nomura C T and Taguchi S (2007) PHA synthase engineering toward superbiocatalysts for custom-made biopolymers, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 73, 5: 969-979. [CrossRef]

- Tajima K et al. (2012) In vitro synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) incorporating lactate (LA) with a block sequence by using a newly engineered thermostable PHA synthase from Pseudomonas sp. SG4502 with acquired LA-polymerizing activity, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 94, 2: 365-376. [CrossRef]

- Sheu D-S and Lee C-Y (2004) Altering the Substrate Specificity of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthase 1 Derived from <em>Pseudomonas putida</em> GPo1 by Localized Semirandom Mutagenesis, Journal of Bacteriology, 186, 13: 4177. [CrossRef]

- Rehm B H A, Antonio R V, Spiekermann P, Amara A A, and Steinbüchel A (2002) Molecular characterization of the poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) synthase from Ralstonia eutropha: in vitro evolution, site-specific mutagenesis and development of a PHB synthase protein model, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology, 1594, 1: 178-190. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi S, Nakamura H, Hiraishi T, Yamato I, and Doi Y (2002) In Vitro Evolution of a Polyhydroxybutyrate Synthase by Intragenic Suppression-Type Mutagenesis1, The Journal of Biochemistry, 131, 6: 801-806. [CrossRef]

- Niamsiri N, Delamarre S C, Kim Y-R, and Batt C A (2004) Engineering of Chimeric Class II Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthases, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 70, 11: 6789. [CrossRef]

- Tsuge T, Watanabe S, Shimada D, Abe H, Doi Y, and Taguchi S (2007) Combination of N149S and D171G mutations in Aeromonas caviae polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase and impact on polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 277, 2: 217-222. [CrossRef]

- Sun J, Shozui F, Yamada M, Matsumoto K i, Takase K, and Taguchi S (2010) Production of P(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate-co-3-hydroxyoctanoate) Terpolymers Using a Chimeric PHA Synthase in Recombinant Ralstonia eutropha and Pseudomonas putida, Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 74, 8: 1716-1718. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Jr. (2014) Critical residues of class II PHA synthase for expanding the substrate specificity and enhancing the biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate, Enzyme and microbial technology, v. 56: pp. 7-66-2014 v.56. [CrossRef]

- Choi S Y et al. (2016) One-step fermentative production of poly(lactate-co-glycolate) from carbohydrates in Escherichia coli, Nature Biotechnology, 34, 4: 435-440. [CrossRef]

- Han X, Satoh Y, Tajima K, Matsushima T, and Munekata M (2009) Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate by an improved two-phase reaction system (TPRS), Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 108, 6: 517-523. [CrossRef]

- Thomson N M et al. (2013) Efficient Production of Active Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthase in <span class="named-content genus-species" id="named-content-1">Escherichia coli</span> by Coexpression of Molecular Chaperones, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 79, 6: 1948. [CrossRef]

- Valentin H E and Steinbüchel A (1994) Application of enzymatically synthesized short-chain-length hydroxy fatty acid coenzyme A thioesters for assay of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthases, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 40, 5: 699-709. [CrossRef]

- de Roo G, Ren Q, Witholt B, and Kessler B (2000) Development of an improved in vitro activity assay for medium chain length PHA polymerases based on CoenzymeA release measurements, Journal of Microbiological Methods, 41, 1: 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Fukui T et al. (1976) Enzymatic synthesis of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate inZoogloea ramigera, Archives of Microbiology, 110, 2: 149-156. [CrossRef]

- Gerngross T U et al. (1994) Overexpression and Purification of the Soluble Polyhydroxyalkanoate Synthase from Alcaligenes eutrophus: Evidence for a Required Posttranslational Modification for Catalytic Activity, Biochemistry, 33, 31: 9311-9320. [CrossRef]

- Burns K L, Oldham C D, Thompson J R, Lubarsky M, and May S W (2007) Analysis of the in vitro biocatalytic production of poly-(β)-hydroxybutyric acid, Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 41, 5: 591-599. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger K E, Steinbüchel A, and Jendrossek D (1995) Substrate specificities of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerases and lipases: bacterial lipases hydrolyze poly(omega-hydroxyalkanoates), (in eng), Applied and environmental microbiology, 61, 8: 3113-3118. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7487042. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC167586/. [CrossRef]

- Behrends A, Klingbeil B, and Jendrossek D (1996) Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) depolymerases bind to their substrate by a C-terminal located substrate binding site, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 143, 2-3: 191-194. [CrossRef]

- Saito T, Iwata A, and Watanabe T (1993) Molecular structure of extracellular poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) depolymerase fromAlcaligenes faecalis T1, Journal of environmental polymer degradation, 1, 2: 99-105. [CrossRef]

- Ohura T, Kasuya K-I, and Doi Y (1999) Cloning and Characterization of the Polyhydroxybutyrate Depolymerase Gene of <em>Pseudomonas stutzeri</em> and Analysis of the Function of Substrate-Binding Domains, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 65, 1: 189. [Online]. Available: http://aem.asm.org/content/65/1/189.abstract. [CrossRef]

- Papaneophytou C P, Pantazaki A A, and Kyriakidis D A (2009) An extracellular polyhydroxybutyrate depolymerase in Thermus thermophilus HB8, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 83, 4: 659-668. [CrossRef]

- Hisano T et al. (2006) The Crystal Structure of Polyhydroxybutyrate Depolymerase from Penicillium funiculosum Provides Insights into the Recognition and Degradation of Biopolyesters, Journal of Molecular Biology, 356, 4: 993-1004. [CrossRef]

- Wakadkar S, Hermawan S, Jendrossek D, and Papageorgiou A C (2010) The structure of PhaZ7 at atomic (1.2 A) resolution reveals details of the active site and suggests a substrate-binding mode, (in eng), Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun, 66, Pt 6: 648-654. [CrossRef]

- Kellici T F, Mavromoustakos T, Jendrossek D, and Papageorgiou A C (2017) Crystal structure analysis, covalent docking, and molecular dynamics calculations reveal a conformational switch in PhaZ7 PHB depolymerase, Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 85, 7: 1351-1361. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y-L, Lin Y-T, Chen C-L, Shaw G-C, and Liaw S-H (2014) Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) depolymerase from Bacillus thuringiensis, Structural biology communications, 70, 10: 1421-1423. [CrossRef]

- Mukai K, Yamada K, and Doi Y (1993) Kinetics and mechanism of heterogeneous hydrolysis of poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] film by PHA depolymerases, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 15, 6: 361-366. [CrossRef]

- Kasuya K-i, Inoue Y, and Doi Y (1996) Adsorption kinetics of bacterial PHB depolymerase on the surface of polyhydroxyalkanoate films, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 19, 1: 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Fujita M et al. (2005) Interaction between Poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] Depolymerase and Biodegradable Polyesters Evaluated by Atomic Force Microscopy, Langmuir, 21, 25: 11829-11835. [CrossRef]

- Hiraishi T, Hirahara Y, Doi Y, Maeda M, and Taguchi S (2006) Effects of Mutations in the Substrate-Binding Domain of Poly[(<em>R</em>)-3-Hydroxybutyrate] (PHB) Depolymerase from <em>Ralstonia pickettii</em> T1 on PHB Degradation, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72, 11: 7331. [CrossRef]

- Kasuya K-i, Ohura T, Masuda K, and Doi Y (1999) Substrate and binding specificities of bacterial polyhydroxybutyrate depolymerases, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 24, 4: 329-336. [CrossRef]

- Gowda U. S V and Shivakumar S (2015) Poly(-β-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) depolymerase PHAZPenfrom Penicillium expansum: purification, characterization and kinetic studies, 3 Biotech, 5, 6: 901-909. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar S (2013) Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) Depolymerase from Fusarium solani Thom, Journal of Chemistry, 2013: 9, Art no. 406386. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar S, Jagadish S J, Zatakia H, and Dutta J (2011) Purification, Characterization and Kinetic Studies of a Novel Poly(β) Hydroxybutyrate (PHB) Depolymerase PhaZPenfrom Penicillium citrinum S2, Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 164, 8: 1225-1236. [CrossRef]

- Tanio T et al. (1982) An Extracellular Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) Depolymerase from Alcaligenes faecalis, European Journal of Biochemistry, 124, 1: 71-77. [CrossRef]

- Madison L L and Huisman G W (1999) Metabolic Engineering of Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoates): From DNA to Plastic, Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 63, 1: 21. [Online]. Available: http://mmbr.asm.org/content/63/1/21.abstract. [CrossRef]

- Hiraishi T, Komiya N, and Maeda M (2010) Y443F mutation in the substrate-binding domain of extracellular PHB depolymerase enhances its PHB adsorption and disruption abilities, Polymer Degradation and Stability, 95, 8: 1370-1374. [CrossRef]

- Tan L-T, Hiraishi T, Sudesh K, and Maeda M (2014) Effects of mutation at position 285 of Ralstonia pickettii T1 poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] depolymerase on its activities, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 98, 16: 7061-7068. [CrossRef]

- Huisman G W, Wonink E, Meima R, Kazemier B, Terpstra P, and Witholt B (1991) Metabolism of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) (PHAs) by Pseudomonas oleovorans. Identification and sequences of genes and function of the encoded proteins in the synthesis and degradation of PHA, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 266, 4: 2191-2198. [Online]. Available: http://www.jbc.org/content/266/4/2191.abstract. [CrossRef]

- Schirmer A, Jendrossek D, and Schlegel H G (1993) Degradation of poly(3-hydroxyoctanoic acid) [P(3HO)] by bacteria: purification and properties of a P(3HO) depolymerase from Pseudomonas fluorescens GK13, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 59, 4: 1220. [Online]. Available: http://aem.asm.org/content/59/4/1220.abstract. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay B A, Saracovan I, Ramsay J A, and Marchessault R H (1994) A method for the isolation of microorganisms producing extracellular long-side-chain poly (β-hydroxyalkanoate) depolymerase, Journal of environmental polymer degradation, 2, 1: 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Williamson D H, Mellanby J, and Krebs H A (1962) Enzymic determination of d(−)-β-hydroxybutyric acid and acetoacetic acid in blood, Biochemical Journal, 82, 1: 90-96. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi T and Saito T (2003) Catalytic triad of intracellular poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) depolymerase (PhaZ1) in Ralstonia eutropha H16, Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 96, 5: 487-492. [CrossRef]

- Kasuya K-i, Inoue Y, Yamada K, and Doi Y (1995) Kinetics of surface hydrolysis of poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] film by PHB depolymerase from Alcaligenes faecalis T1, Polymer Degradation and Stability, 48, 1: 167-174. [CrossRef]

- Kasuya K et al. (1997) Biochemical and molecular characterization of the polyhydroxybutyrate depolymerase of Comamonas acidovorans YM1609, isolated from freshwater, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 63, 12: 4844. [Online]. Available: http://aem.asm.org/content/63/12/4844.abstract. [CrossRef]

- Handrick R et al. (2001) A New Type of Thermoalkalophilic hydrolase of Paucimonas lemoignei with high specificity for amorphous polyesters of short chain-length hydroxyalkanoic acids., The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276, September 28, 39: 36215-36224. [CrossRef]

- Jendrossek D (2007) Peculiarities of PHA granules preparation and PHA depolymerase activity determination, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 74, 6: 1186. [CrossRef]

- Molitoris H P, Moss S T, de Koning G J M, and Jendrossek D (1996) Scanning electron microscopy of polyhydroxyalkanoate degradation by bacteria, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 46, 5: 570-579. [CrossRef]

- Spyros A, Kimmich R, Briese B H, and Jendrossek D (1997) H NMR Imaging Study of Enzymatic Degradation in Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate). Evidence for Preferential Degradation of the Amorphous Phase by PHB Depolymerase B from Pseudomonas lemoignei, Macromolecules, 30, 26: 8218-8225. [CrossRef]

- Oh J S, Choi M H, and Yoon S (2005) In vivo 13C-NMR spectroscopic study of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid degradation kinetics in bacteria, Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 15: 1330-1336.

- Taidi B, Mansfield D A, and Anderson A J (1995) Turnover of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) and its influence on the molecular mass of the polymer accumulated by Alcaligenes eutrophus during batch culture, FEMS Microbiology Letters, 129, 2-3: 201-205. [CrossRef]

- De Eugenio L I et al. (2006) Biochemical evidence that phaZ gene encodes a specific intracellular medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerase in Pseudomonas putida KT2442: characterization of a paradigmatic enzyme, Journal of Biological Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa Y and Calabia B P (2004) Review Degradation of microbial polyesters, Biotechnology Letters, 26, 15: 1181-1189. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P K, Mohanan N, Sidhu R, and Levin D B (2019) Colonization and degradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates by lipase-producing bacteria, Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 65, 6: 461-475. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed R A, Salleh A B, Leow A T C, Yahaya N M, and Abdul Rahman M B (2017) Ability of T1 Lipase to Degrade Amorphous P(3HB): Structural and Functional Study, Molecular Biotechnology, 59, 7: 284-293. [CrossRef]

- Mok P-S, Ch’ng D H-E, Ong S-P, Numata K, and Sudesh K (2016) Characterization of the depolymerizing activity of commercial lipases and detection of lipase-like activities in animal organ extracts using poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) thin film, AMB Express, 6, 1: 97. [CrossRef]

- Ch’ng D H-E and Sudesh K (2013) Densitometry based microassay for the determination of lipase depolymerizing activity on polyhydroxyalkanoate, AMB Express, 3, 1: 22. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Contreras A, Calafell-Monfort M, and Marqués-Calvo M S (2012) Enzymatic degradation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) by commercial lipases, Polymer Degradation and Stability, 97, 4: 597-604. [CrossRef]

- Mendes A A, Oliveira P C, Vélez A M, Giordano R C, Giordano R d L C, and de Castro H F (2012) Evaluation of immobilized lipases on poly-hydroxybutyrate beads to catalyze biodiesel synthesis, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 50, 3: 503-511. [CrossRef]

- Yang T H, Kwon M-A, Lee J Y, Choi J-E, Oh J Y, and Song J K (2015) In Situ Immobilized Lipase on the Surface of Intracellular Polyhydroxybutyrate Granules: Preparation, Characterization, and its Promising Use for the Synthesis of Fatty Acid Alkyl Esters, Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 177, 7: 1553-1564. [CrossRef]

- Houten S M and Wanders R J A (2010) A general introduction to the biochemistry of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation, Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, 33, 5: 469-477. [CrossRef]

- Chung A-L et al. (2011) Biosynthesis and Characterization of Poly(3-hydroxydodecanoate) by β-Oxidation Inhibited Mutant of Pseudomonas entomophila L48, Biomacromolecules, 12, 10: 3559-3566. [CrossRef]

| Short-chain-length PHAs | Medium-chain-length PHAs |

|---|---|

| Highly crystalline [76,77] | Low crystallinity [76,77] |

| Hard [76,77] | Soft [76,77] |

| Brittle [76,77] | Flexible [76,77] |

| Thermo-elastomeric polyesters [76,77] | |

| Low glass transition and melting temperature [76,78] | |

| Low tensile strength and modulus [76,78] | |

| Higher elongation at break [76,78] |

| Organism used | Β-oxidation pathway modification | PHAs yield | % of mcl-monomer | Substrate used | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ralstonia eutropha | Heterologous expression of phaC from, Rhodococcus aetherivorans I24, Expression of phaJ from P. aeruginosa to increase PHAs accumulation, Modification of the phaB activity |

71 wt% 66 wt% |

P(HB-co-17%-HHx) P(HB-co-30%-HHx) |

Palm oil | [92] |

| Cupriavidus necator (Ralstonia eutropha) | phaC from R. aetherivorans I24 and phaJfrom P. aeruginosa expressed in plasmid pCB113 | 45 wt% 1.3 g/l PHAs |

P(HB-co-70%HHx) | Crude palm kernel oil | [93] |

| Ralstonia eutropha | Introduction of crotonyl-CoA reductase from Streptomyces cinnamonensis, phaC and phaJ from A. caviae | 48 wt% 1.48 g/l CDW |

P(HB-co-1.5%HHx) | Fructose | [94] |

| Ralstonia eutropha | Overexpression of enoyl coenzyme-A hydratase (phaJ) and phaC2. Deletion of acetoacetyl Co-A reductases (phaB1, phaB2 and phaB3) | 69 wt% | P(78%HB-co-22%HHx) | Coffee waste oil | [95] |

| Pseudomonas putida KCTC1639 | Overexpression of phaJ Overexpression offabG |

27wt% 0.51 g/l PHAs (FabG overexpression depressed PHAs production) |

NI | Octanoic acid | [90] |

| Cupriavidus necator | Expression of fadE from E. coli and phaJ1 from P. putida KT2440, in plasmid pMPJAS03 | 46.1wt%, 4.1 g/l CDW 38.3 wt%, 3.28 g/l CDW |

P(99%HB-co-0.37%HV-co-0.27%HHx-co-0.21%HO-co-0.08%HD) P(99.39%HB-co-0.33%HV-co-0.18%HHx-co-0.10%HO) |

Canola oil Avocado oil |

[91] |

| DH5α Escherichia coli | Deletion of key genes in β-oxidation pathway and overexpression of acyl-ACP thioesterase (BTE), phaJ3 and phaC2 from P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PP_0763 from P. putida KT2440 strain (fadRABIJ) | 0.93 g/l CDW 0.75 wt% |

P(100%HDD) | Decanoic acid | [96] |

|

Escherichia coli W3110 Escherichia coli WA101(fadA mutant) |

Expression offabGfrom E. coli and phaC2 from Pseudomonas sp 61-3 Expression of rhlG from P. aeruginosa and PhaC2 from Pseudomonas. sp 61-3 Expression of fabG from E. coli and phaC2 from Pseudomonas. sp 61-3 |

4.8 wt%, 1.73g/l CDW, 0.08g/l PHAs 3.2wt%, 1.20g/l CDW, 0.04g/l PHAs 22.1wt%, 0.98g/l CDW, 0.22g/l PHAs |

P(11%HHx-co-39%HO-co-50%HD) P(47%HO-co-53%HD) P(7%HO-co-93%HD) |

Sodium decanoate |

[97] |

| Cupriavidus necator | 5 different transformants harboring phaC BP-M-CPF4 gene. (phaJ from P. aeruginosa expression increased HHx proportion). (phaB and phaA genes expression modify composition) |

(48.9-83.7)wt% (3.6-6.2)CDW (2.1-1.4)g/l PHAs |

HHx(1-18%) | Palm olein Palm kernel oil |

[98] |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | Deletion of phaZ, fadBA1andfadBA2 and overexpression of phaG, alkK, phaC1 and phaC2 (strain AG2162) | 1.758 g/l CDW 54 wt% 0.657g/l CDW, 17.7 wt% |

No information | P-coumaric acid Lignin(corn stover) |

[99] |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | No (acrylic acid inhibits β-oxidation pathway) | 75.5 wt% 1.8 g/lh PHAs |

P(89%HHp-co-11%HN) | nonanoic acid: glucose: acrylic acid (1.25:1:0.05) | [89] |

| P. putida KT2442 | Deletion of: fadB2x, fadAx, fadB, fadA, 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA deshydrogenase, acyl-CoA dehydrogenase and phaG. | 9.19 wt% 1.03 g/l CDW |

P(3HD-co-84%-3HDD) | Decanoic acid Dodecanoic acid |

[87] |

| P. putida KT2442 | Deletion of fadB and fadA, Deletion of phaC and replacement with phaPCJAC operon (KTOYO6ΔC (phaPCJAC) strain) | 5.82 g/l CDW 57.80 wt% |

58%PHB-block-42%PHHx | sodium butyrate, sodium hexanoate (1:2) alternating times | [100] |

| Pseudomonas entomophila LAC32 | Weakening of β-oxidation pathway (Deletion of fadA(x), fadB(x) and phaG) Insertion of phaA and phaB from C. necator. PhaC mutated from P. putida 61-3. Block of some genes in de novo fatty acid synthesis pathway |

Not reported | different rations with mcl from 0 to 100% | Glucose and related fatty acids | [101] |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2442 | fadA and fadB knockout mutant | 84 wt% | P(41%HDD-co-59%HA) | Dodecanoate | [102] |

| Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01 |

fadA and fadB knockout mutant (NKU-∆β5) fadA, fadB, phaG, phaZ knockout mutant (NKU-∆8) NKU-∆8. |

38 wt%, 1.7 g/l CDW 44 wt%, 2.3 g/l CDW 32 wt%, 1.3 g/l CDW |

P(5.57%HHx-co-93.3%HO-co-1.05%HD) P(5.29%HO-co-94%HD) P(2.99%HO-co-28%HD-co-68%HDD) |

Sodium octanoate Sodium decanoate Dodecanoic acid |

[103] |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2442 | Deletion of fadA, fadB (P. putida KTOY06) | 2.86 g/l CDW 45.99 wt% |

P(2.2%HHx-co-11%HO-co-21.6%HD-co-16.1%HDD-co-49%HTD) | Tetradecanoic acid | [104] |

| Source PhaC | Mutation | Host | Carbon source | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. stutzeri 1317 | Ser325Thr Gln481Lys |

Ralstonia eutropha PHB¯4 | Gluconate and Octanoate | Higher PHAs content and more affinity for PHB. | [130] |

| Pseudomonas 61-3 | Ser325Cys Ser325Thr Glu481Lys Glu481Met Glu481Arg |

Ralstonia eutropha PHB¯4 | Fructose | Higher activity. The combination Ser325Cys with Glu481Met has higher activity but all combination worked. Mutation in position 481 produces higher molecular weight. (98-99% of short-chain-length) | [136] |

| P. putida GPo1 | Leu484Val Ala547Val Gln481Met Ser482Gly |

P. putida GPp104 PHAs¯ | Sodium octanoate | Leu484Val increase PHB monomer content Ala547Val increase PHAs content. Gln481Met increases HHx monomer and PHAs content Ser482Gly increases HHx monomer and PHAs content. |

[137] |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | Glu358Gly Asn398Ser |

Β-oxidation deficient E. coli LSBJ | Sodium dodecanoate | Higher PHDD production with higher molecular weight. Amino acids with hydrophobic and smaller residues either retained or increased PHDD. | [138] |

| Pseudomonas sp. 61-3 | Ser325Cys ---TGC Ser325Thr---ACC Gln481Met Gln481Lys--- AAG Gln481Arg---CGG |

E. coli | Glucose | Double mutants increase PHB content. Codon picking is very important to enhance PHB content. The mutation Ser325Thr, which exists in PhaC type I, increases affinity for PHB. | [139] |

|

Cupriavidus necator Aeromonas caviae |

26% of the N-terminal of PhaCAC and 74% of the C-terminal of PhaCRe |

E. coli LSS218 | Sodium dodecanoate | Using sodium dodecanoate, they obtained higher scl-mcl PHAs than the parental enzymes. | [140] |

|

P. chlororaphis P. sp. 61-3 P. putida KT2440 P. resinovorans P. aeruginosa PAO1 |

Glu130Asp Ser325Thr Ser477Gly Gln481Lys |

E. coli XL1-Blue | Glucose Lactate |

PhaC having mutations in these 4 sites were able to accept lactyl-CoA as substrate and produce PLA while wild types did not accumulate polymers. | [141] |

| P. sp. MBEL 6-19 | Glu130Asp Ser325Thr Gln481Met |

E. coli XL1-Blue | Glucose | Increase the substrate specificity towards scl. Production pf P(HB-co-LA) | [142] |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | Glu130Asp Ser325Thr Ser477Gly Gln481Lys |

E. coli | Lactic acid | Terpolyesters (LA-co-3HB-3HP) Change of substrate specificity. |

[143] |

| Pseudomonas sp.61-3 | Gln508Leu Gln481Lys |

E. coli | Mutation Gln508Leu is present in C. necator. Double mutation enhances PHB content. |

[144] |

| Method | PhaC source | Changed enzyme property | Polyester | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversify PCR random mutagenesis | Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | Higher yield with higher molecular weight | P3HDD | [138] |

| Error-prone PCR mutagenesis, saturation mutagenesis, in vitro recombination | Pseudomonas sp. 61-3 | Higher yield | P3HB | [139] |

| Site-specific mutagenesis | Pseudomonas sp. SG4502 | Substrate specificity | P(LA-co-3HB) | [150] |

| Localized semi-random mutagenesis | Pseudomonas oleovorans GPo1 | Substrate specificity | P3HB, P3HA | [151] |

| Gene shuffling | C. necator | Higher yield, substrate specificity | P3HA | [152] |

| PCR-mediated random mutagenesis, intragenic suppression-mutagenesis | Ralstonia eutropha | Yield | P3HB | [153] |

| Chimeric PHA synthase |

P. oleovorans P. fluorescens P. aureofaciens |

Higher yield, substrate specificity | scl/mcl | [154] |

| Recombination of beneficial mutations | Aeromonas caviae | Molecular weight, fraction composition | P(3HB-co-3HHx) | [155] |

| Chimeric PHA synthase |

Aeromonas caviae C. necator |

Substrate specificity | P(3HB-co-3HHx-co-3HO) | [156] |

| Chimeric PHA synthase |

A. caviae C. necator |

Substrate specificity | 3HHx / 3HB | [140] |

| Site specific mutagenesis | Pseudomonas sp. S64502 | Substrate specificity | P(LA-co-3HB) | [150] |

| Site specific mutagenesis |

P. chlororaphis P.sp.61-3 P. putida KT2440 P. resinovorans P. aeruginosa PAC1 |

Substrate specificity | P(3HB-co-LA) | [141] |

| Site specific mutagenesis Saturation mutagenesis |

Pseudomonas sp. MBEL 6-19 | Substrate specificity | P(3HB-co-LA) | [142] |

| Site specific mutagenesis, saturation mutagenesis | Pseudomonas putida GPo | Yield, substrate specificity | Copolymers with 3HB, 3HHx, 3HO, 3HD | [157] |

| None (natural mutation) | Pseudomonas MBEL 6-19 | Substrate specificity | P(LA-co-GA-co-3HB) P(LA-co-GA-co-4HB), P(LA-co-GA-2HB) | [158] |

| Site specific mutagenesis | Pseudomonas stutzeri | Substrate specificity | P(LA-co-3HB-co-3HP) | [143] |

| PCR- mediated random mutagenesis Recombination of beneficial mutations. |

Pseudomonas sp.61-3 | Yield | P3HB | [144] |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoA detection 412 nm | Quick | False positives due to other hydrolysis reactions that release CoA. | [70,161,162] |

| Thioesters hydrolysis detection 236 nm | Quick | Less accurate than CoA detection. | [70,163,164] |

| Substrate depletion and product formation analysis with HPLC and GC | Highly accurate | More time consuming | [131] |

| Co-A, acetyl-CoA and β-hydroxybutyryl-CoA analysis with HPLC | It is accurate and measures fluctuation in the overall system | Costly and time consuming | [165] |

| Organism | Type | Apparent Km(µg/ml) | Apparent Vmax(µg/min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium expansum | ePHAscl | 1.04 | 4.5 | [180] |

| Thermus thermophilus | edPHAscl-typeI | 53 | N/A | [170] |

| Fusarium solani | ePHAscl | 100 | 50 | [181] |

| Penicillium citrinum | ePHAscl | 1250 | 12.5 | [182] |

| Alcaligenes faecalis | edPHAscl-typeI | 13.3 | N/A | [183] |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sudan Black observation | Easy and quick | Not quantitative result | [187] |

| Halo formation in plate assay | Easy and quick, for extracellular PhaZ only. | Semi-quantitative result | [6,188,189] |

| Measurement of 3HB release | Quantitative method | No information | [190,191,192,193] |

| Measure esterase activity at 410 nm | Quantitative method | No information | [170,188] |

| Measurement of PHAs weight lost | Easy | Not practical for rapid routine assays | [194,195] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).