Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

25 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Measurement of Plant Fresh and Dry Weight

2.3. Measurement of Photosynthetic Rate, Chlorophyll, and Carotenoid Content

2.4. Measurement of Fruit Yield and Individual Fruit Weight

2.5. Measurement of Fruit Firmness and Brix

2.6. Measurement of Total Sugar, Sucrose, Reducing Sugar, and Titratable Acid Contents

2.7. Determination of Flavonoid Content in Fruit

2.8. Determination of Ca and Mg Content

2.9. Determination of Exchangeable Ca Content

2.10. Determination of Ca Content in Xylem Sap

2.11. Data Analysis

3. Results

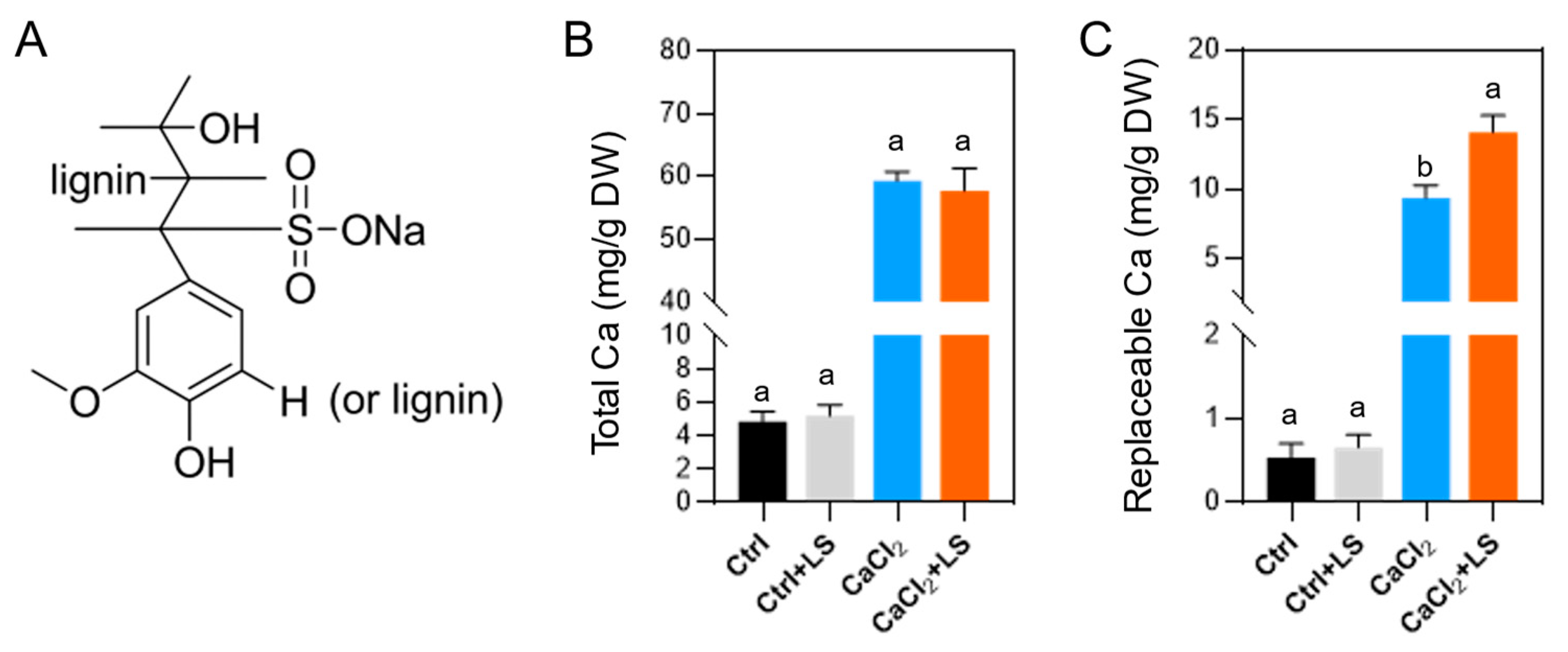

3.1. Lignosulfonate Maintains Soil Available Ca

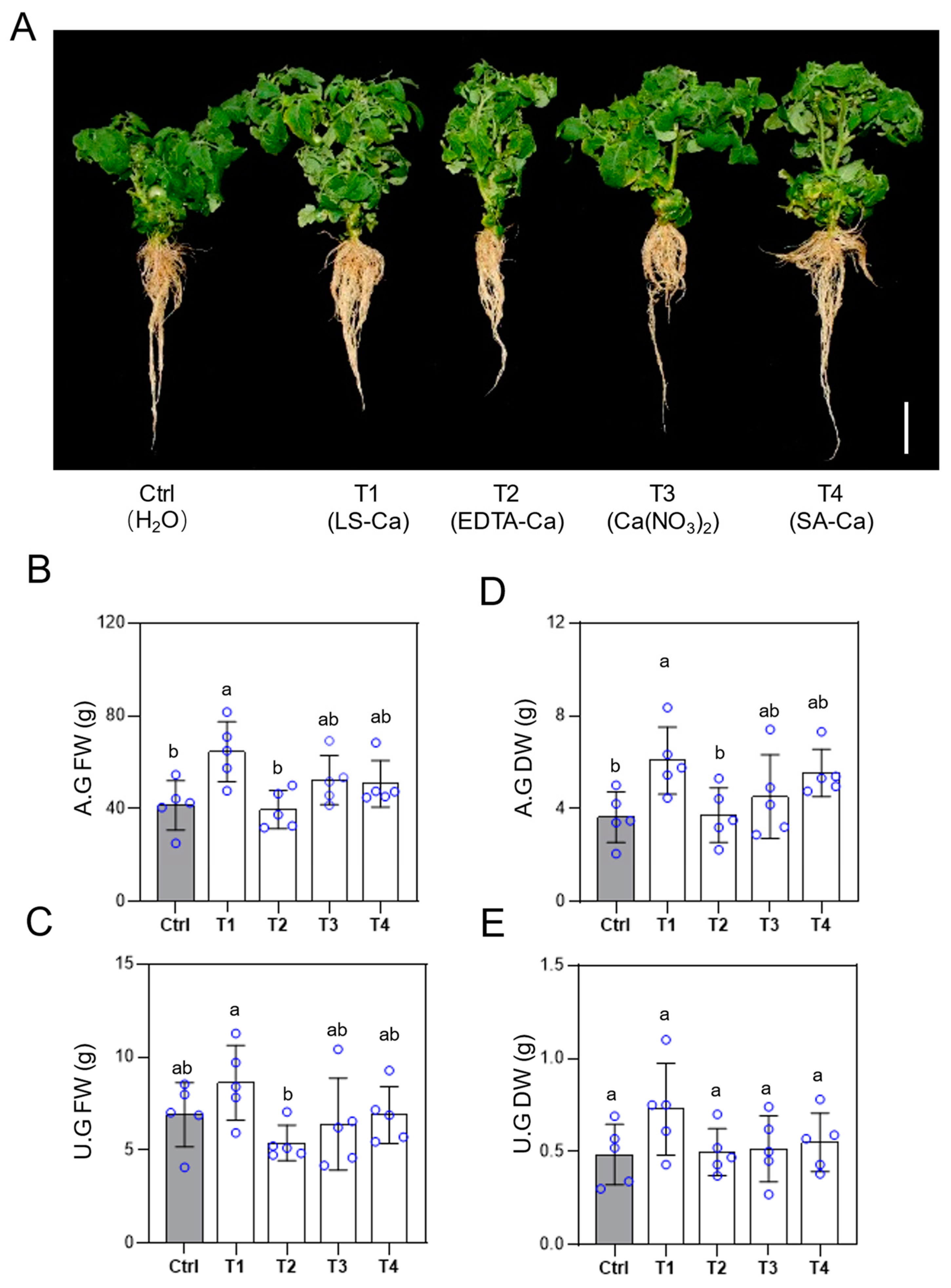

3.2.LS-Ca Fertilizer Promotes the Growth of Aboveground Parts of Tomato Plants

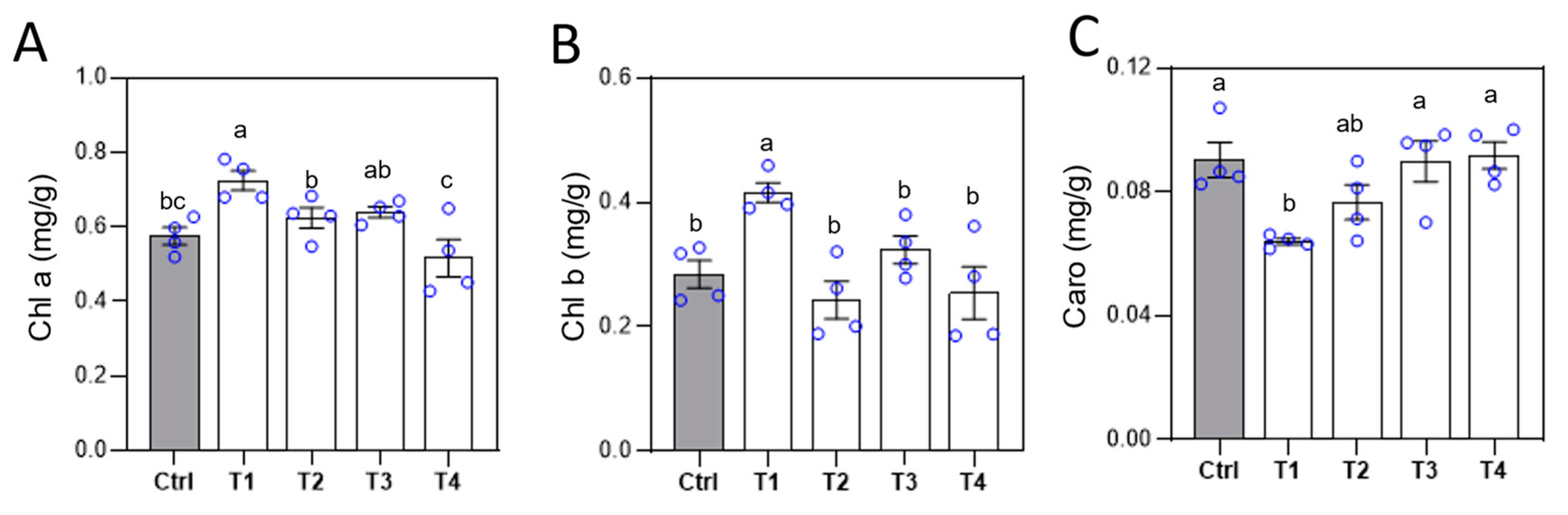

3.3. LS-Ca Fertilizer Improves Light Use Efficiency in Tomatoes

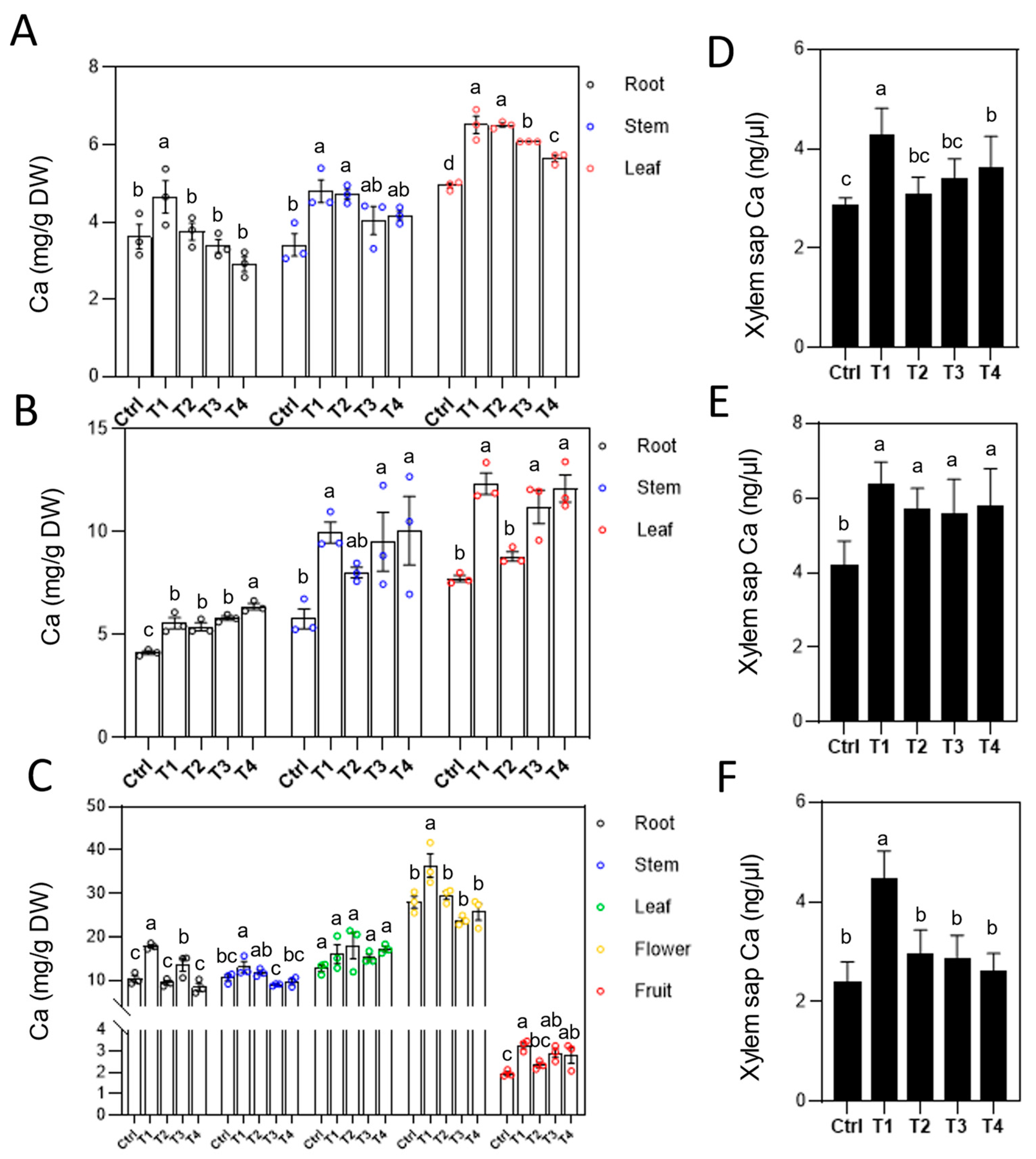

3.4. LS-Ca Fertilizer Enhances Ca²⁺ Uptake and Transport

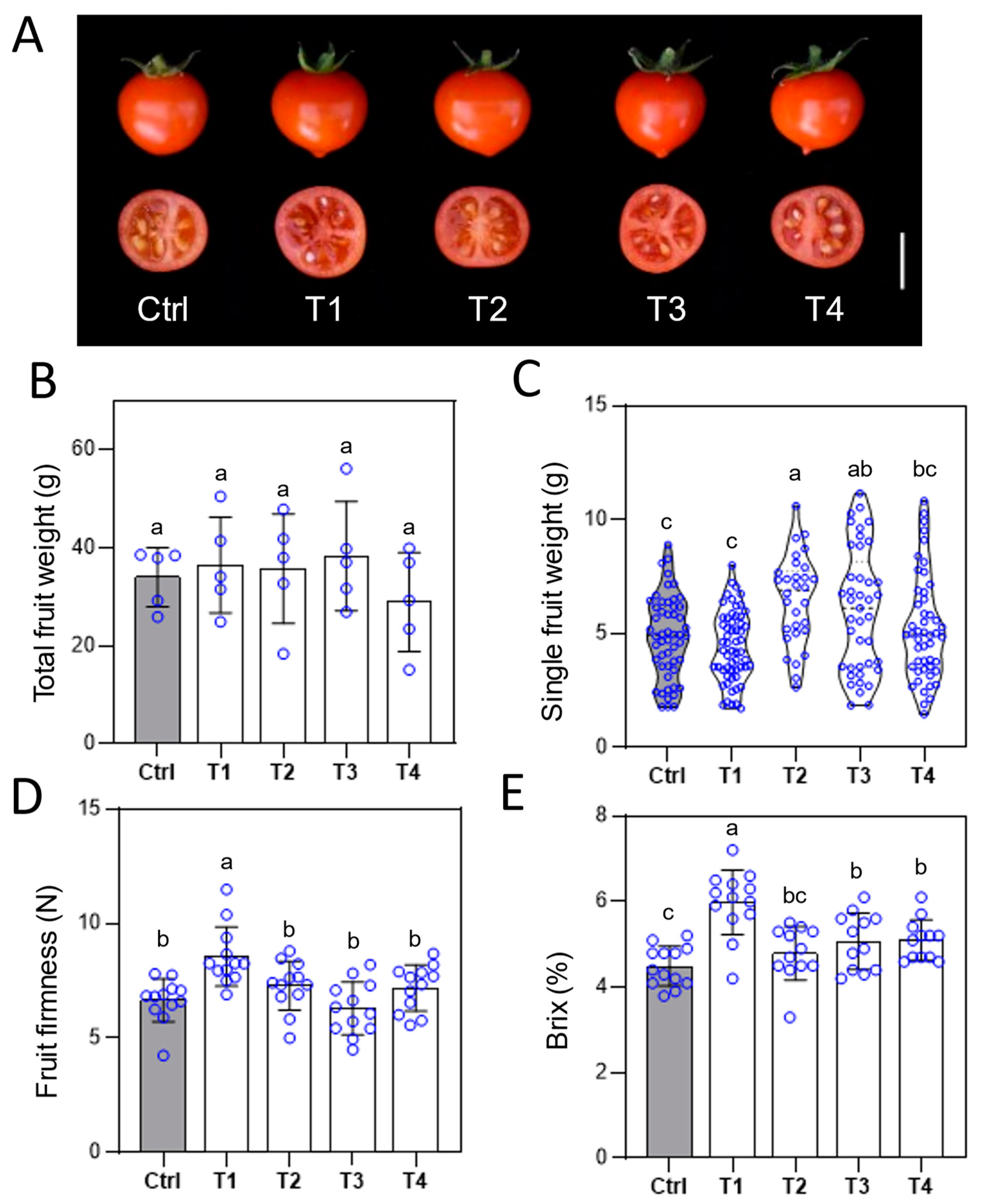

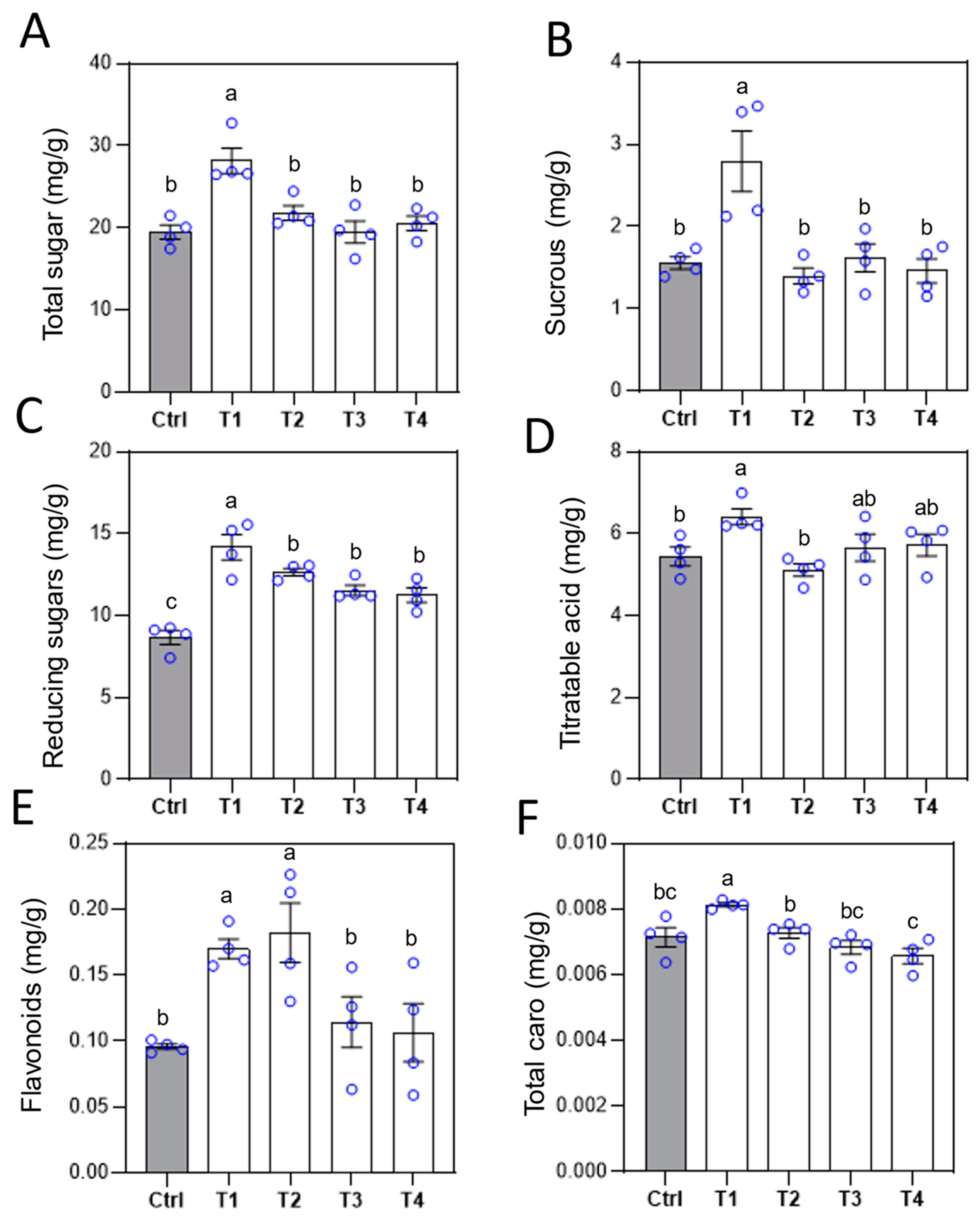

3.5. LS-Ca Fertilizer Enhances Tomato Fruit Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naveed Ahmad, I.A., Asif Ali, Muhammad Sajid, Izhar Ullah, Abdur Rab, Syed Tanveer Shah, Fazal-i-Wahid,; Masood Ahmad, A.B., Fareeda Bibi,. 2. Foliar application of Ca improves growth, yield and quality of tomato cultivars. Pure and Applied Biology (PAB) 2020, 10-19%V 19.

- Kadir, S.A. Fruit Quality at Harvest of “Jonathan” Apple Treated with Foliarly-Applied Ca Chloride. J. Plant Nutr. 2005, 27, 1991-2006. [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.J.; Kofranek, A.; Rubatzky, V.E.; Hartmann, H.T. Plant Science: Growth, Development, and Utilization of Cultivated Plants. BioScience 1983.

- Bangerth, F. Ca-Related Physiological Disorders of Plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1979, 17, 97-122. [CrossRef]

- Goulding, K.W.T. Soil acidification and the importance of liming agricultural soils with particular reference to the United Kingdom. Soil Use Manage. 2016, 32, 390-399. [CrossRef]

- Rajan, M.; Shahena, S.; Chandran, V.; Mathew, L. Chapter 3 - Controlled release of fertilizers—concept, reality, and mechanism. In Controlled Release Fertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture, Lewu, F.B., Volova, T., Thomas, S., K.R, R., Eds.; Academic Press: 2021; pp. 41-56.

- Jing, T.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Shankar, A.; Saxena, A.; Tiwari, A.; Maturi, K.C.; Solanki, M.K.; Singh, V.; Eissa, M.A.; et al. Role of Ca nutrition in plant Physiology: Advances in research and insights into acidic soil conditions - A comprehensive review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 210, 108602. [CrossRef]

- de Souza Alonso, T.A.; Ferreira Barreto, R.; de Mello Prado, R.; Pereira de Souza, J.; Falleiros Carvalho, R. Silicon spraying alleviates Ca deficiency in tomato plants, but Ca-EDTA is toxic. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2020, 183, 659-664. [CrossRef]

- Norvell, W.A. Reactions of Metal Chelates in Soils and Nutrient Solutions. In Micronutrients in Agriculture; 1991; pp. 187-227.

- Li, T.; Wei, Q.; Sun, W.; Tan, H.; Cui, Y.; Han, C.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, F.; Huang, M.; Yan, D. Spraying sorbitol-chelated Ca affected foliar Ca absorption and promoted the yield of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Hui, Y.; Zhang, L.; Su, B.; Wang, R. Foliar application of chelated sugar alcohol Ca fertilizer for regulating the growth and quality of wine grapes. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2022, 15, 153-158. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kawai, T.; Inukai, Y.; Aoki, D.; Feng, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Fukushima, K.; Lin, X.; Shi, W.; Busch, W.; et al. A lignin-derived material improves plant nutrient bioavailability and growth through its metal chelating capacity. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4866. [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.D.-X.; Wan Abdullah, W.M.A.N.; Tang, C.-N.; Low, L.-Y.; Yuswan, M.H.; Ong-Abdullah, J.; Tan, N.-P.; Lai, K.-S. Sodium lignosulfonate improves shoot growth of Oryza sativa via enhancement of photosynthetic activity and reduced accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13226. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.M. Nutrient Remobilization During Leaf Senescence. In Annual Plant Reviews Volume 26: Senescence Processes in Plants; 2007; pp. 87-107.

- Hocking, B.; Tyerman, S.D.; Burton, R.A.; Gilliham, M. Fruit Ca: Transport and Physiology. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Wang, G.; Sui, J.; Liu, G.; Ma, F.; Bao, Z. Biostimulants alleviate temperature stress in tomato seedlings. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 293, 110712. [CrossRef]

- Alexou, M.; Peuke, A.D. Methods for Xylem Sap Collection. In Plant Mineral Nutrients: Methods and Protocols, Maathuis, F.J.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2013; pp. 195-207.

- Rubin, E.M. Genomics of cellulosic biofuels. Nature 2008, 454, 841-845. [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 850-861. [CrossRef]

- Hepler, P.K.; Winship, L.J. Ca at the Cell Wall-Cytoplast Interface. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 147-160. [CrossRef]

- Gilliham, M.; Dayod, M.; Hocking, B.J.; Xu, B.; Conn, S.J.; Kaiser, B.N.; Leigh, R.A.; Tyerman, S.D. Ca delivery and storage in plant leaves: exploring the link with water flow. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2233-2250. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, U.M.; Ji, N.; Li, H.; Wu, Q.; Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Ma, D.; Lu, X. Can lignin be transformed into agrochemicals? Recent advances in the agricultural applications of lignin. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113646. [CrossRef]

- Kevers, C.; Soteras, G.; Baccou, J.C.; Gaspar, T. Lignosulfonates: Novel promoting additives for plant tissue cultures. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Plant 1999, 35, 413-416. [CrossRef]

- Muto, S.; Izawa, S.; Miyachi, S. Light-induced Ca2+ uptake by intact chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. 1982, 139, 250-254. [CrossRef]

- Kreimer, G.; Melkonian, M.; Holtum, J.A.M.; Latzko, E. Characterization of Ca fluxes across the envelope of intact spinach chloroplasts. Planta 1985, 166, 515-523. [CrossRef]

- Kreimer, G.; Melkonian, M.; Latzko, E. An electrogenic uniport mediates light-dependent Ca2+ influx into intact spinach chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. 1985, 180, 253-258. [CrossRef]

- Hochmal, A.K.; Schulze, S.; Trompelt, K.; Hippler, M. Ca-dependent regulation of photosynthesis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2015, 1847, 993-1003. [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.A.; Halliwell, B. Action of Ca ions on spinach (Spinacia oleracea) chloroplast fructose bisphosphatase and other enzymes of the Calvin cycle. Biochem. J. 1980, 188, 775-779. [CrossRef]

- Portis, A.R.; Heldt, H.W. Light-dependent changes of the Mg2+ concentration in the stroma in relation to the Mg2+ dependency of CO2 fixation in intact chloroplasts. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1976, 449, 434-446. [CrossRef]

- Hertig, C.; Wolosiuk, R.A. A dual effect of Ca2+ on chloroplast fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1980, 97, 325-333. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, G.; Siemion, J.; Antidormi, M.; Bonville, D.; McHale, M. Have Sustained Acidic Deposition Decreases Led to Increased Ca Availability in Recovering Watersheds of the Adirondack Region of New York, USA? Soil Systems 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Cui, B.; Ge, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, J. Reinforcement of Recycled Aggregate by Microbial-Induced Mineralization and Deposition of Ca Carbonate—Influencing Factors, Mechanism and Effect of Reinforcement. Crystals 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.F.; Ahmed, O.H.; Jalloh, M.B.; Omar, L.; Kwan, Y.M.; Musah, A.A.; Poong, K.H. Soil Nutrient Retention and pH Buffering Capacity Are Enhanced by Calciprill and Sodium Silicate. Agronomy 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bemadac, A.; Jean-Baptiste, I.; Bertoni, G.; Morard, P. Changes in Ca contents during melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruit development. Sci. Hortic. 1996, 66, 181-189. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.-w.; Chen, J.-y.; Song, T.; Jiang, Y.-g.; Zhang, Y.-f.; Wang, L.-j.; Li, F.-l. Preharvest spraying Ca ameliorated aroma weakening and kept higher aroma-related genes expression level in postharvest ‘Nanguo’ pears after long-term refrigerated storage. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 247, 287-295. [CrossRef]

- DRAŽETA, L.; LANG, A.; HALL, A.J.; VOLZ, R.K.; JAMESON, P.E. Causes and Effects of Changes in Xylem Functionality in Apple Fruit. Ann. Bot. 2004, 93, 275-282. [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, S.Y.; Greer, D.H.; Hatfield, J.M.; Orchard, B.A.; Keller, M. Solute Transport into Shiraz Berries during Development and Late-Ripening Shrinkage. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 73. [CrossRef]

- Choat, B.; Gambetta, G.A.; Shackel, K.A.; Matthews, M.A. Vascular Function in Grape Berries across Development and Its Relevance to Apparent Hydraulic Isolation. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1677-1687. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fan, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Sun, S.; Sun, R.-C. Research Progress in Lignin-Based Slow/Controlled Release Fertilizer. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4356-4366. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).