1. Introduction

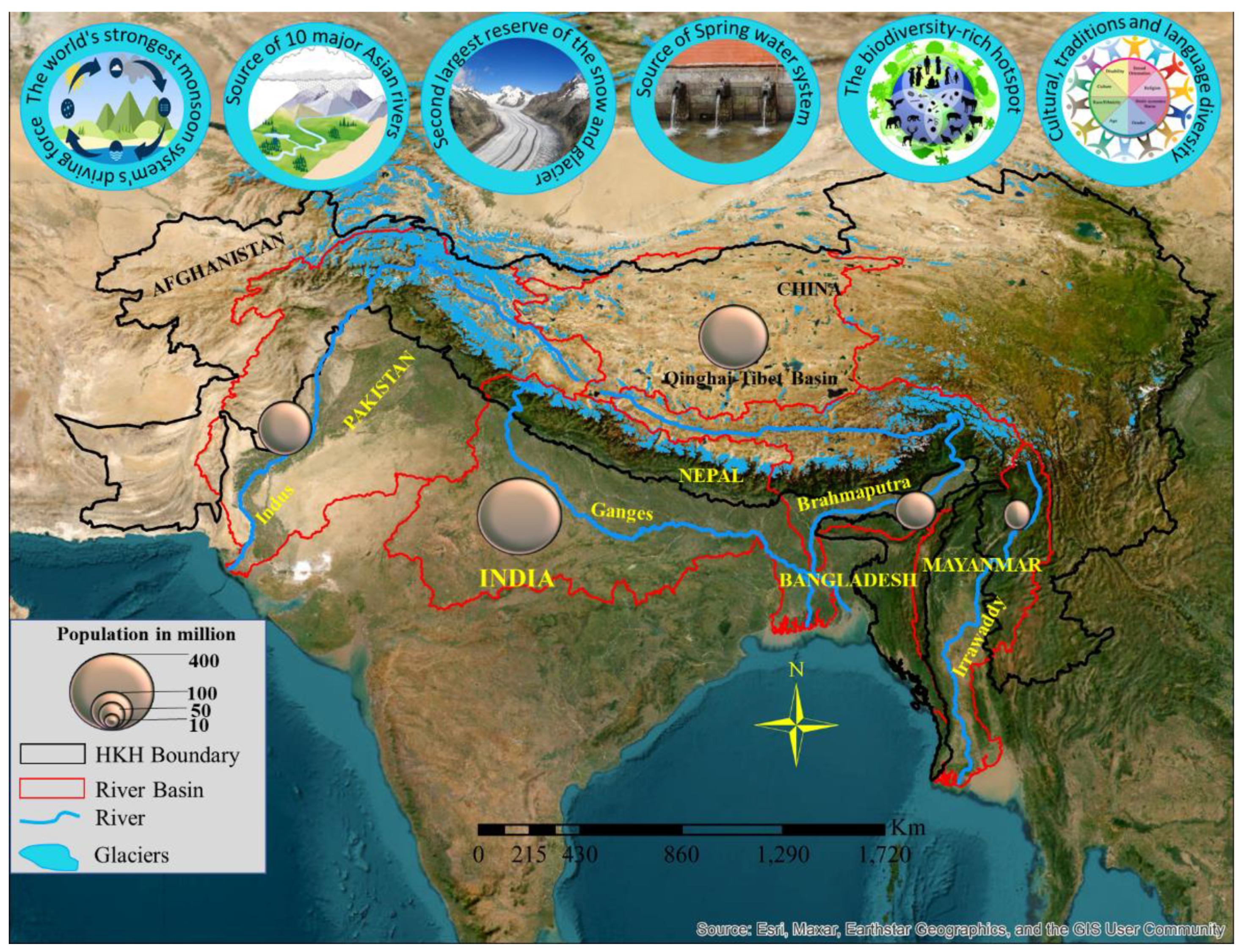

Given their significant contribution to global freshwater supplies and the polar regions, the Himalayas are referred to as the Earth's third pole (Dyurgerov and Meier, 2005). Across eight nations (India, China, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, Nepal and Pakistan), the Hindukush Himalayas (HKH) area stretches for around 3500 km. With approximately 12,000 glaciers spanning 41,000 km³, the HKH region is home to the largest glacier systems (Bolch et al., 2012). Snow, glaciers, and springs are the main contributing factors that keep the mega rivers flowing during the year's lean flow period (Gurung et al., 2018; Pant et al., 2021a). Flowing from the Himalayan cryospheric system, the principal rivers (Yangtze, Indus, Brahmaputra, Ganges, Mekong, and Yellow) offer a diverse array of ecosystem services, providing the foundation for one-fifth of the world's population, or 1.5 billion people, to survive (Rasul and Sharma, 2016). It is well known that these rivers originate in the Himalayas and are fed by glaciers. In contrast, precipitation in the form of rain and snowfall contributes significantly to the water supply in river systems that are not fed by glaciers.

Furthermore, spring is the sole reliable supply that keeps these rivers flowing during the dry seasons. A working group on "Inventory and Revival of Springs of the Himalaya for Water Security" was formed by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog in 2017 to assess the extent of spring-related issues. Five million springs are thought to exist in India, almost three million of which are in the Indian Himalayan Region alone, according to this research (Aayog, 2017). For the billions of people living in the Himalayan region, springs are a major source of water and the natural outflow of groundwater (Mantri, 2021). Whether in the lower plains or the headwater area, springs regulate the hydrology of the river. Because of the major springs that contribute to their flow, nearly all of the Himalayan rivers are perennial, flowing even during the dry season. The quality and discharge of these springs therefore directly affects how long mega rivers last. The primary sources of water for households, agriculture, and drinking in the Himalayan regions are springs. The majority of the river water is available for daily usage by the communities residing near the foothills' base. Nevertheless, the hamlets in the high-altitude regions suffer greatly from the fact that rivers in these geographical areas are unreachable; as a result, the communities in these locations rely mostly on the springs.

Recent climatic changes and rising temperatures, coupled with fewer rainy days in the Himalayan region and a roughly 16% decrease in snow cover from 1990 to 2001, have led to a reduction in spring discharge (Menon et al., 2010). These changes have caused negative mass balances, making springs increasingly vulnerable and highlighting the need for effective spring rejuvenation efforts (IPCC, 2007). Climate change is clearly affecting precipitation patterns and amounts, while land use changes, deforestation, reduced agricultural activities, landslides, and soil erosion are all contributing to the decline in spring discharge observed globally (Berg et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017). In the headwater regions, changes in water demand and supply have led to disruptions in the ecosystem of the HKH region (Siddique et al., 2019). Therefore, it is essential to develop comprehensive management strategies to tackle water shortages and manage water resources in a more efficient and sustainable manner, given the fluctuations in the factors that influence spring hydrology (Li et al., 2017).

In recent decades, extensive research has been conducted to understand the effects of climate change on global water resources (Green et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2020; Scanlon et al., 2023). Much of this research has concentrated on surface-water hydrology because of its visibility, accessibility, and widespread use (Green, 2016). However, only recently have scientists, water resource managers, and policymakers started to recognize the critical role of groundwater in providing drinking water, supporting commercial and industrial activities, and sustaining global ecosystems (Green et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2024). The withdrawal of groundwater from transboundary aquifers, much like surface water, is expected to have significant political implications in the near future (Vrba and Gun, 2004; Green et al., 2011). Puri and Aureli (2005) provided a detailed examination of issues related to transboundary aquifers and created a global map of these groundwater resources. Nevertheless, assessing the impact of climate change on mountain groundwater or spring hydrology remains challenging due to the numerous factors that directly or indirectly influence these water sources (Ojha et al., 2017). The scarcity of discharge data, climatic information, geological data, and land use coverage makes it particularly difficult to gauge the extent of the problems and develop effective solutions for the water crisis in the HKH region.

Water management extends beyond technical and scientific interventions to encompass human values, behaviors, and political agendas (Linton and Budds, 2014). Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM), as described by Gleick (2000), integrates ecological, cultural, and economic aspects while involving all stakeholders. Linton and Budds (2014) argue that the hydro-social cycle “requires investigating hydrosocial relations and as a broader framework for undertaking critical political ecologies of water” (page 170), which links water changes to social impacts, requires a transdisciplinary approach. This approach acknowledges that changes in water quality and quantity can alter social structures, creating a continuous cycle of impact if not addressed early.

Transdisciplinary research aims to bridge the gap between science and practice through a holistic, problem-oriented approach (Nowotny et al., 2001; Hoffmann et al., 2017; Dollin et al., 2023). Transdisciplinary water research supports the critical decision points during the research process (Krueger et al., 2016). However, Brouwer et al., (2018) suggested that transdisciplinary research can thrive only when it is grounded in a strong foundation of disciplinary knowledge. Apart from that, there must be a consensus among the stakeholders to work in a transdisciplinary mode of work, rather than adopting disciplinary research work. Ferguson et al., (2018), argued that there must be sufficient allocation of time, funding, and personnel to enhance and promote meaningful stakeholder participation throughout all stages of the transdisciplinary project, from inception to completion.

In the context of the Himalayan spring ecosystem, while interdisciplinary knowledge is present, transdisciplinary insights are still needed (Gosavi et al., 2021). Therefore, addressing water management challenges in the Himalayas requires a transdisciplinary approach that integrates diverse perspectives and expertise to develop solutions that address the region's social, ecological, and economic dimensions. This approach is crucial for managing the complex and dynamic Himalayan spring ecosystem sustainably.

Figure 1.

Map of the Hindukush Himalayan region and the sub-watersheds Indus, Ganga, Brahmaputra, Qinghai-Tibetan and Irrawaddy. Population in each river basin is presented after Shrestha et al., 2015.

Figure 1.

Map of the Hindukush Himalayan region and the sub-watersheds Indus, Ganga, Brahmaputra, Qinghai-Tibetan and Irrawaddy. Population in each river basin is presented after Shrestha et al., 2015.

This paper reviews the current scientific understanding of spring water hydrology globally and specifically within the Hindukush Himalayan (HKH) region. It examines the role of springs in achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and assesses international efforts to manage these resources amidst climate change and socio-economic challenges. We have scrutinized scientific methodologies used in studying spring hydrology, highlighted various interventions aimed at increasing spring discharge, and explored initiatives by both government and non-governmental organizations. Our case studies offer insights applicable on a global scale and advocate for a transdisciplinary approach to enhance SDG outcomes.

Our analysis stresses the importance of integrating scientific research with public participatory models for effective spring water management. By involving local stakeholders and fostering awareness, we aim to guide policymakers and managers in developing sustainable water resource strategies. The ultimate goal is to demonstrate how decreasing spring discharge can be mitigated and how springs can become valuable socio-economic assets, thereby contributing to regional well-being and potentially reversing migration trends through collaborative and inclusive management practices.

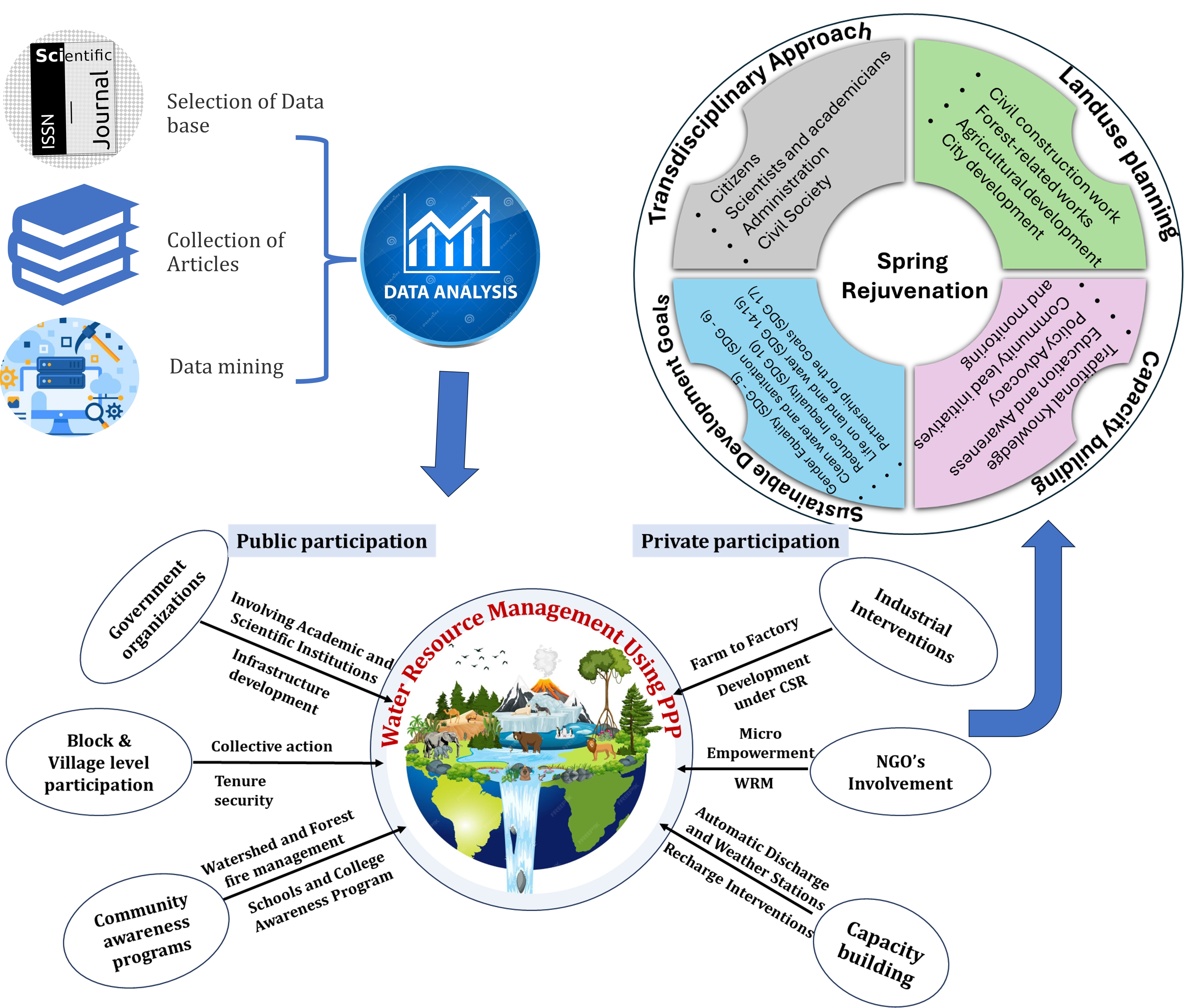

2. Methodology

This paper moves beyond a traditional review paper in that the methodology does not rely on literature reviews only. The methodology combines a classic literature review with 30 years of authors'experience in the Indian Himalayan region. Researchers have been working in the Central Himalayan region, monitoring spring water hydrological processes and social interactions with the Himalayan community have highlighted the requirement to expand beyond this single discipline orientation. Moreover, other authors of this paper have long experience working with the hydrological challenges outside the HKH region and bring their experience of connecting water with people through this review. Moreover, our experience of working in Khulgad watershed for last 30 years has helped us to develop an ethnographic review of the Himalayan Spring, resulting in, not only relying on the research articles but also connecting our long experience in spring hydrology and transdisciplinary research in the water sector.

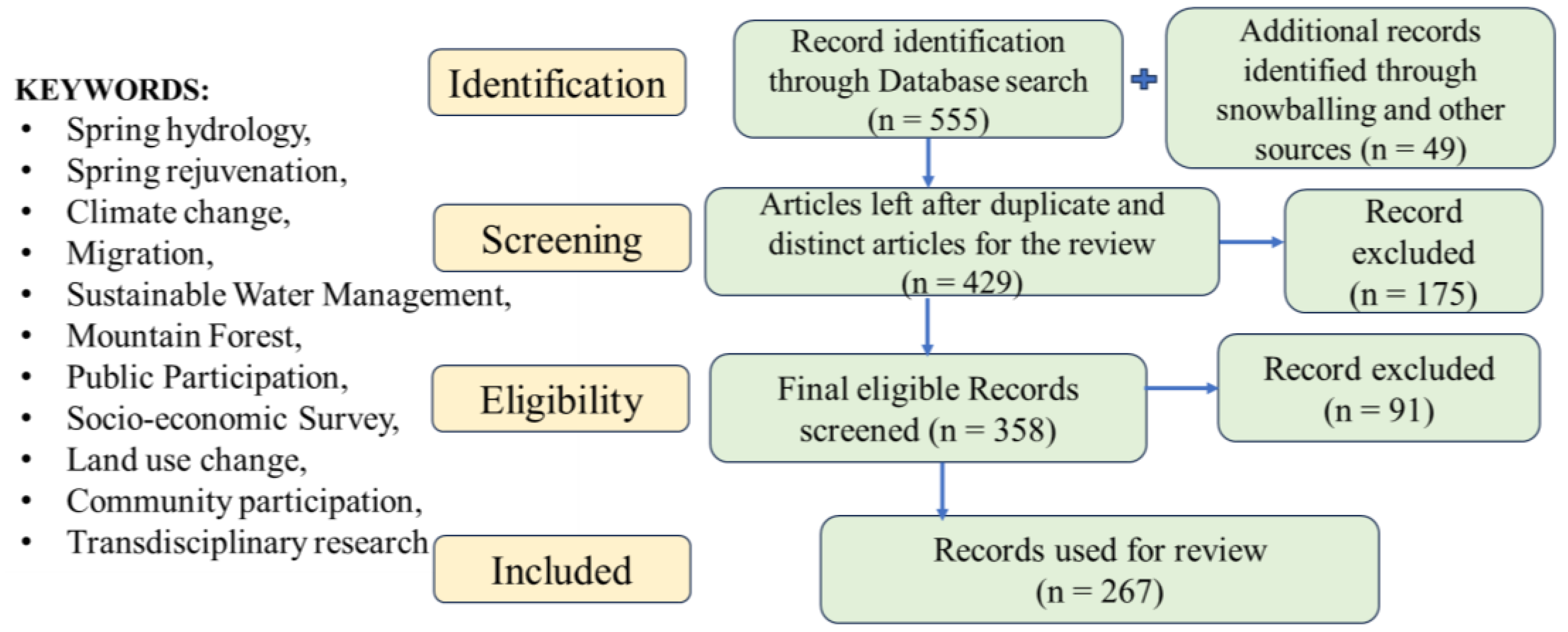

Following Saunders et al., (2012), who describes a structured literature review as an iterative process involving keyword definition, literature search, and analysis, we employed a six-step literature review process. This approach helped identify key works, pinpoint recent research areas, and provide insights into current research trends and future directions (

Figure 2). Moreover, snow balling method has also been adopted to select some of the literatures relevant for this review paper.

2.1. Defining Keywords

This study utilized the following query keywords: spring hydrology, spring rejuvenation, climate change, migration, sustainable water management, mountain forest, public participation, socio-economic survey, land use change, community participation, and transdisciplinary research. Based on these keywords, we created ten different combinations and used the boolean operator AND to identify the relevant literature.

“Spring hydrology” AND “sustainable water management”-02

“Spring rejuvenation”-16

“Springshed management”-10

“Mountain forest” AND “hydrology”-54

“Land use change” AND” spring hydrology”-9

“Public participation” AND “hydrology”-44

“Transdisciplinary research” AND “water”-257

“Participatory action research” AND “hydrology”-4

“Community participation” AND “Spring”-63

“Community engagement” AND “Spring”-96

These combinations were chosen to explore hydrological investigations, mountain spring hydrology, spring rejuvenation techniques, springshed management, impact of climate change and land use change in spring hydrology, transdisciplinary research and public involvement in springshed management.

2.2. Initial Results

This section involved gathering articles from multidisciplinary databases, primarily Scopus, accessed via the University Library of Western Sydney University. Scopus, is known for its extensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals across various disciplines, hence it was selected for its comprehensive scope (Fahimnia et al., 2015). Keywords were searched within the "title, abstract, keywords" fields in Scopus. The search was filtered to include articles published between 1985 and 2024, restricted to "Journal" documents and in "English," resulting in 555 articles for analysis. 49 additional reports and articles have been obtained through the national records and snowballing that were not available in the Scopus directory or under the key words.

2.3. Refining the Initial Results

To refine the search results, duplicates and the articles that are not streamlined with the present work were removed, resulting in 429 papers. From the review of the 429 results 358 records were found suitable under the mountain region water sources. Further manual filtering based on study relevance (present work) reduced the number of relevant documents to 267, covering the period from 1985 to 2024. Some articles that were identified though snowballing while reviewing the selected literature but doesn’t appear in the literature review process were also included in the review process. On the basis of the refined search results eight keyword combinations and linkages were defined and is detailed in

Table 1.

3. Factors Contributing to the Decrease in Spring Discharge and Water Quality

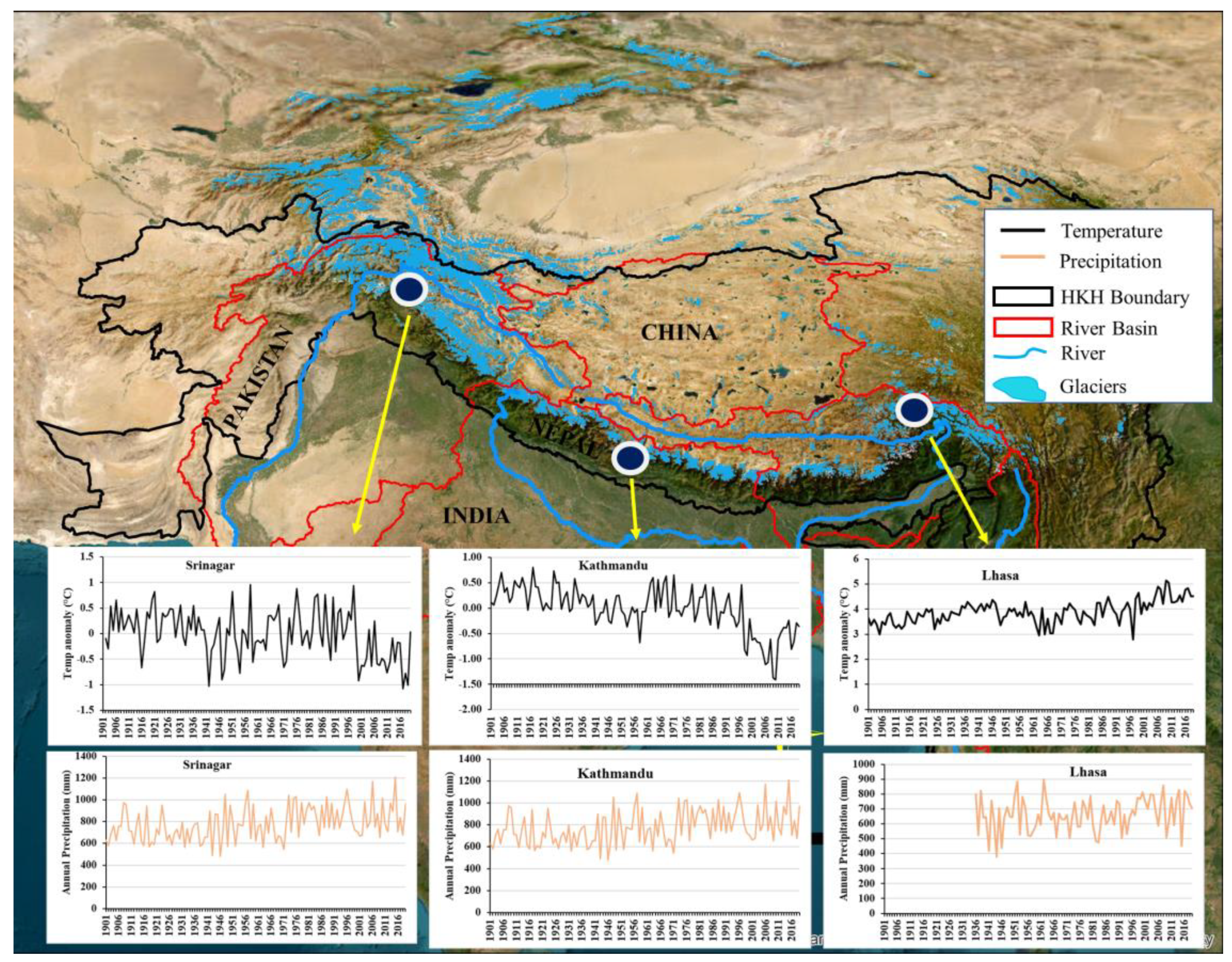

3.1. Impact of Climate Change on Spring Hydrological Cycle

Climate change and unsustainable human activities heighten the vulnerability of Himalayan ecosystems. Natural springs, vital for providing drinking water to the Himalayan population, are significantly affected by shifts in precipitation patterns, temperature, and glacier melt. Research shows that human-induced global warming alters precipitation and evapotranspiration patterns, impacting the sustainability of both surface and groundwater resources (Chiew and McMahon, 2002; IPCC, 2007). Rising temperatures can increase evaporation and evapotranspiration losses, causing water stress that adversely affects crop growth and yields. Consequently, changes in rainfall and temperature may drastically impact crop water needs, productivity, and yields, potentially leading to food shortages (Das, K., 2021).

The sustainability of spring water is heavily dependent on precipitation levels, making the analysis of future climate projections crucial for understanding spring water potential in the coming decades. Climate models, which have evolved since the 1960s, help us grasp climate patterns on local, regional, and global scales. These models include simple climate models (SCMs), energy-balance models, Earth-system models of intermediate complexity (EMICs), and comprehensive three-dimensional general circulation models (GCMs) (Green et al., 2011). According to the IPCC (2007), these models can provide valuable predictions of future climate changes at the continental level. However, accurately forecasting spring water discharge trends remains challenging due to limited localized data. To address this, downscaling techniques refine GCM outputs to local scales (Green et al., 2011).

In the HKH region, a more pronounced warming trend is observed compared to the plains (Verma and Jamwal, 2022). Detailed monthly analyses show a loss of seasonal contrast, with warmer winters and reduced heat during the rainy season. The Himalayas are warming faster than the global average, making them highly sensitive to climate changes (Shrestha et al., 2021). Rainfall is decreasing, especially during peak wet months from June to September, indicating significant climate shifts in the region (Mishra, 2017). Projections suggest that areas between 1000 and 2500 meters above sea level in the Himalayas will see a significant reduction in the frequency of wet days due to global warming (Ballav et al., 2021; Verma and Jamwal, 2022).

Precipitation is expected to become more erratic and intense, leading to increased surface runoff and reduced aquifer recharge (Shrestha, 2015). Azhoni & Goyal (2018) reported that local residents, despite lacking historical flow records, have observed many springs drying up, attributing this to climate change. Gu et al., (2022) found that while the overall frequency of droughts might remain stable, extreme events are likely to increase with rising temperatures. Therefore, understanding and evaluating long-term climate variability is essential for effective groundwater resource planning and management, especially given the growing demands from population growth and various sectors (Warner, 2007).

Figure 3.

The data for HKH region showing the change in temp and rainfall pattern from 1901 to 2016 at Srinagar, Kathmandu and Lhasa in HKH region [Data source: Climate Research Unit (CRU) Time Series (TS) Volume 4.01 (Harris et al., 2020)].

Figure 3.

The data for HKH region showing the change in temp and rainfall pattern from 1901 to 2016 at Srinagar, Kathmandu and Lhasa in HKH region [Data source: Climate Research Unit (CRU) Time Series (TS) Volume 4.01 (Harris et al., 2020)].

3.2. Impact of Land Use Change on Spring Hydrological Cycle

The hydrological balance between upstream and downstream areas in the Himalayan region is significantly affected by changes in climate and physical factors such as land use and land cover (LULC), snow cover, lean season flow, soil erosion, and sedimentation (Nepal et al., 2014). Changes in forest and urban landscapes are impacting the recharge sites in the headwater regions. There is limited research on how land use changes influence regional climate variables like precipitation, temperature, and humidity, and how these changes interact with global warming and the hydrological cycle in the Hindukush Himalayan region. Additionally, there is a lack of multidisciplinary data on watershed-level soil and geology that connects LULC changes with interactions between surface water and groundwater, which can lead to the deterioration of stream and river water quality. While land use and land cover changes do not directly increase pollution, they can exacerbate pollution when combined with climate change due to reduced dilution capacity for increasing non-point source pollutants. Furthermore, a key research question that remains unresolved is whether forests consume more water than grasslands (Madani et al., 2018).

Both human activities and natural processes influence land use and land cover (LULC) changes in watersheds. Tiwari (2008) noted that population growth and forest degradation in the Nainital district have led to reduced spring discharge. Singh and Pande (1989) found that converting native oak forests to pine forests in the Uttarakhand Himalayas affected spring hydrology. Pine forests, which have higher transpiration rates than oak forests, have been linked to declining spring discharge, while oak forests are known for better water infiltration and soil moisture retention (Ghimire et al., 2014). Similarly, Narain and Singh (2019) explored how expanding urban areas in the Kumaon Himalaya impact land use and water resources. Conversely, Alvarez-Garreton et al. (2019) found that increasing plantation density reduces annual runoff. To address the impacts of climate change and growing populations, further scientific research is needed on how plantation practices affect spring recharge, discharge, and surface runoff, particularly in forested regions.

Changes in land use and land cover (LULC) are known to affect groundwater recharge rates, which can alter pore pressure and lead to slope instability and landslides (Dehn et al., 2000). Increased groundwater levels from climatic or human activities can destabilize slopes and impact geomorphological and engineering aspects (Dragoni and Sukhija, 2008). Large-scale afforestation on barren land, if not carefully managed with geological and scientific considerations, can disrupt hydrological balance and cause landslides (Woldeamlak et al., 2007; Peña-Arancibia et al., 2012; Van Dijk et al., 2012).

Figure 4.

Change in LULC (Barren to Pine Forest) pattern between 1990 and 2022 of Kanlei Village in Khulgad watershed, Almora, India.

Figure 4.

Change in LULC (Barren to Pine Forest) pattern between 1990 and 2022 of Kanlei Village in Khulgad watershed, Almora, India.

3.2.1. Deforestation

Forest cover significantly impacts water availability at both local and regional levels, but extensive forest loss due to population pressure and demand for forest products has been prevalent (Ellison et al., 2017). Common causes of deforestation include logging, land conversion, frequent fires, agricultural expansion, and fuelwood collection (Lanh, 1994; Schmidt-Vogt, 2000). Trees affect hydrology through interception, evapotranspiration, and infiltration, which influence rainfall reaching the soil and groundwater (Nepal et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2023). Deforestation accelerates negative hydrological impacts, leading to land degradation, increased erosion, higher peak discharges, and reduced dry season flows (Bartarya, 1989; Bruijnzeel and Bremmer, 1989). In Asia, efforts are underway to regenerate degraded landscapes to address soil erosion, flooding, and drought, and to reduce pressure on remaining forests (Chokkalingam, 2001). Rüegg et.al., (2022), has briefly summarized the first Swiss Federal Forest Law (1876), which prefers to establish the mountain forest as the natural means of protection against the flood hazard.

While tree planting is seen as a climate change mitigation strategy, Bastin et al. (2019) emphasize the need to balance carbon and water cycles. Native forests generally use less water and retain more soil moisture compared to plantations. Native forests also result in less runoff and sedimentation than plantations or grasslands (Balocchi et al., 2021). Studies, such as Gilmour et al. (1987) on the Nepal Himalayas, show that forestation of grazed grasslands can improve soil water absorption. However, in the Uttarakhand region, deforestation and reduced rainfall led to a 35%–75% decrease in spring flow from the Gaula River basin between 1958 and 1986 (Valdiya & Bartarya, 1989, 1991). In Nainital, extensive deforestation has caused 159 natural springs to dry up and 50 to become seasonal in the past 30 years (Tiwari, 2008). Similarly, in Almora, Kumaun Mountains, 270 out of 360 springs have dried up due to land use changes (Rawat, 2009).

3.2.2. Population and Migration

Urban areas in the HKH region are rapidly growing due to rural-to-urban migration and natural population increases. Kumar et al. (2023) found a 135.02% rise in built infrastructure in Himalayan cities over the past 30 years, while ecological infrastructure has decreased by about 24%. As urban populations grow, so does the demand for water for drinking, sanitation, and industry (Singh et al., 2020). Urbanization has expanded from mid-elevation areas to higher Himalayan regions, driven by economic and technological changes and increased tourism. This expansion in tectonically active and ecologically unstable areas has led to resource depletion, biodiversity loss, and changes in climate, forests, and water availability, along with improved road connectivity, flash floods, slope failures, and landslides. These developments have altered the hydro-social cycle in the HKH region (Tiwari and Joshi, 2018). Increased infrastructure and human activities have led to higher surface water runoff and reduced groundwater recharge, diminishing spring and stream discharge (Tiwari and Joshi, 2016). Examples from Shimla and Almora highlight the insufficient protection of water supplies that have historically supported these communities.

In Almora, the town now relies on the Kosi River for water instead of the over 300 springs it previously used. Despite increased pumping capacity, the community faces shortages when the river dries up in the summer (Singh and Pandey, 2020). Mussoorie plans to lift water from the Yamuna River, located about 18 km away, using a four-stage pumping system. In contrast, Nainital has shifted from relying solely on springs to obtaining 95% of its water through lake bank filtration (Dimri & Dash, 2012). Most springs in the watershed have dried up or become seasonal, with only a small fraction of water supplied by a single remaining spring (Shah & Tewari, 2009). Rising populations have increased water demand and sewage generation, worsening river pollution (Khattiyavong and Lee, 2019). Socio-economic factors such as agricultural, industrial, and domestic needs, along with sewage treatment and effluent characteristics, also affect river water quality (Whitehead et al., 2015). In Uttarakhand, permanent and semi-permanent migration has led to depopulation and land abandonment. Between 2001 and 2013, male out-migration surged by 686%, resulting in a high sex ratio of 1037 women per thousand men (Tiwari and Joshi, 2016; Sati, 2021). The 2011 census recorded permanent migration in 3946 villages (25.1% of all villages) and semi-permanent migration in 6338 villages (40.25%) (Sati, 2021).

Migration from the Hindukush Himalayan (HKH) region is primarily driven by the search for employment opportunities elsewhere. Contributing factors include low agricultural productivity worsened by climate change, declining water availability, limited education, poor transportation and healthcare, and wildlife issues. As the region shifts from agrarian to wage-based livelihoods, traditional farming practices are being abandoned (Sati, 2021). The region’s challenging terrain hampers industrial development, pushing both educated and uneducated youth to seek opportunities outside. This outmigration disproportionately affects women, impacting their health, nutrition, and daily responsibilities, including fetching water from distant sources (Rao et al., 2019).

Climate change is altering rainfall patterns and reducing irrigation water sources, leading to decreased agricultural yields and accelerating migration from villages to cities. This cycle diminishes irrigated agricultural land, increases runoff from hilly areas, and reduces groundwater recharge and spring discharge. These issues contribute to socio-economic challenges and environmental degradation in the Himalayan region. An integrated, transdisciplinary watershed management approach is essential to sustain the HKH ecosystem.

3.2.3. Forest Fire

Wildfires significantly impact the hydrological and soil processes in catchments. Climate predictions indicate that wildfires will become more frequent and severe, affecting the mountain regions' hydrological cycle (Balocchi et al., 2022). Factors such as lack of winter precipitation and extreme early spring heat increase the risk of severe forest fires (Bozkurt et al., 2017). Dry watersheds with historically low moisture levels also contribute to higher fire risk (Garreaud et al., 2017). Forest fires rapidly alter leaf area, transpiration, and interception, which disrupt regional water balance controls (Shakesby et al., 2006; Nolan et al., 2015; White et al., 2020). This dryness and the reduction in cover can lead to complex and unpredictable changes in catchment storage and hydrology, making it crucial to understand these changes for effective water resource management (Batelis et al., 2014).

During a forest fire, canopy destruction, changes in soil water repellence, and alterations in soil macropore structure can increase peak and storm flows while decreasing baseflow and low flows (Scott et al., 1992; Bart et al., 2017). The formation of a hydrophobic layer or soil sealing is believed to contribute to these changes (Larsen et al., 2009; Flint, 2019). Such alterations can significantly affect groundwater recharge rates, streamflow, and soil moisture storage (Bart et al., 2017). Additionally, severe dryness exacerbates the reduction of groundwater and soil water reserves (Garreaud et al., 2017).

Each watershed responds differently to these hydrological changes during forest fires, and effective management relies on site monitoring, water age estimation, groundwater residence duration, and hydrological modeling (Balocchi et al., 2022). Various studies have explored fire impacts on streamflow dynamics using methods like paired catchment experiments, isotope mass balance, geochemical analysis, and runoff modeling (Bart & Hope, 2010; Balocchi et al., 2021; Loáiciga et al., 2001; Gibson et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2005; Jung et al., 2008; Seibert et al., 2010; Lane et al., 2012; Silberstein et al., 2013; Saxe et al., 2018; Pant et al., 2021a).

Research by Sheoran et al. (2022) indicates that wood burning is a major source of black carbon (BrC) emissions, which peak during the pre-monsoon and are primarily due to local forest fires. Black carbon affects local and global climates by altering cloud properties, radiative forcing, snow albedo, and precipitation (Bond et al., 2013). Similarly, Balochhi et al. (2022) studied the impact of forest fires on mean transit times (MTTs) of streamflow in central Chile, finding no significant changes in runoff and baseflow post-fire. However, more data on groundwater with high residence times is needed to detect any fluctuations in stream and baseflow.

3.3. Change in Spring Water Quality

Himalayan springs are celebrated for their fresh, mineral-rich water (Panwar, 2023). The chemistry of spring water is influenced by surface and subsurface geology, residence time, weathering rates, and local climate. Unlike surface waters, the hydrochemical processes affecting springs are more complex. Major factors leading to reduced spring discharge and water quality include changes in land use, altered rainfall patterns, and rising temperatures (Tambe et al., 2012; Shrestha et al., 2017). Anthropogenic activities have further worsened spring water quality by introducing new contaminants or exposing existing ones (Negi & Joshi, 2010; ACWADAM, 2011; Panwar, 2022).

Spring water quality is impacted by both geogenic factors, such as fluoride (F-) and iron (Fe) (Ansari et al., 2015; Joshi, 2006; Pant et al., 2021b), and anthropogenic factors like nitrates (NO3-) and fecal coliforms (Jeelani & Shah, 2016). In the drinking water, the fecal matter up to 160 CFU and turbidity >10 NTU are responsible for causing gastrointestinal illness (Nowreen et al., 2023). In the Kashmir Himalayas, fecal coliforms and total coliform streptococci ranged from 2-92, 13-260, and 3-15 MPN/100 ml (Shah & Jeelani, 2016). Nitrate contamination often results from agricultural chemicals and inadequate sewage management (Joshi & Kothyari, 2003; Thakur et al., 2018), with concentrations averaging 50-60 mg/l and reaching up to 224 mg/l in some areas (Thakur et al., 2018). Fecal coliforms are linked to settlements and cattle grazing (Negi & Joshi, 2010; Shah & Jeelani, 2016), while high electrical conductivity (EC) and low dissolved oxygen (DO) are associated with agricultural activities, making the water unsuitable for consumption (Kumar et al., 1997; Joshi, 2006). According to CHIRAG, 80% of tested springs had fecal coliform contamination. Karst springs in Jammu and Kashmir show higher levels of coliform, streptococci, nitrate, and chloride compared to other springs (Jeelani et al., 2018; Taloor et al., 2020; Lone et al., 2021). In the Kandela watershed of Himachal Pradesh, spring water is supersaturated with carbonate minerals and undersaturated with evaporites, indicating significant rock-water interaction (Ansari et al., 2015).

Population growth and tourism have further deteriorated water quality in the HKH region due to unregulated waste (Goldenberg, 2011; Shrestha et al., 2020). The region lacks adequate wastewater treatment infrastructure, with heavy tourism exacerbating the problem. For example, Namche Bazaar, a key stop for Mount Everest trekkers, has no wastewater treatment facilities despite significant tourist traffic. Sewage from local lodges flows directly into the Kosi River (Goldenberg, 2011).

Regular monitoring of select springs is recommended to address risks such as nutrient enrichment and pollution from heavy metals, pesticides, and microplastics (Bhat et al., 2022). In the Tehri Garhwal area of Uttarakhand, spring water shows positive correlations among bicarbonates (HCO3-), total hardness, calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+), and total dissolved solids (TDS), indicating geological controls, while chloride (Cl-), potassium (K+), sulfate (SO42-), and nitrate (NO3-) suggest anthropogenic contamination (Dudeja et al., 2013). Climate change and natural variability impact the quantity and quality of the hydrological cycle, affecting spring and river discharge (Holman, 2006; IPCC, 2007; Panwar, 2020; Tiwari et al., 2018). Reduced low flow volumes further compromise water quality during these periods (Santy et al., 2022).

4. Spring Recharge Interventions and Rejuvenations

To address the declining spring discharge and water crisis in the Himalayan regions, communities have increasingly adopted various water conservation methods. Over the past few decades, numerous CSOs (Civil Society), NGOs (Non- Government Organisations), and government organizations have launched spring rejuvenation programs. Some of the organisations that are effectively working with community-level partners for the spring rejuvenation are Advanced Centre for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM) in Maharashtra, the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) in Nepal, and the People’s Science Institute (PSI) in Dehradun.

Aayog (2017) has advised transitioning from the traditional ridge-to-valley approach to a valley-to-valley model to more effectively pinpoint and manage spring recharge zones for targeted restoration and protection. This new approach includes providing technical and capacity-building support in hydrogeology and aquifer management. Recharge interventions are generally categorized into two main types: Mechanical interventions and Biological interventions. Among these, mechanical interventions have proven particularly effective. However, given the diverse topography and geology of the Himalayan region, it is crucial to conduct watershed-level research to develop tailored methodologies for designing and selecting recharge structures that align with local hydrology, groundwater flow, terrain conditions, and water demand. Moreover, Assistive Natural Regeneration (ANR) has recently gained prominence for its cost-effective and environmentally friendly benefits in spring rejuvenation.

4.1. Mechanical Interventions

Springshed development approaches using rainwater harvesting structures and plantations of native trees have been considered the main rejuvenation practices in the Himalayan region to rejuvenate the springs in the Himalayan region. The mechanical intervention approach consists of trenches, hedge rows, percolation pits, check dams, and fencing with barbed wire, reducing grazing activities and preventing deforestation (Negi & Joshi, 2002). Before intervention work, hydrogeological investigations, delineation of aquifer boundary, and recharge zone identification were considered the primary tasks to be taken into account (Kumar & Pramanik, 2020). Typically, in seismically active mountain terrain, it is impractical to harness and store enormous amounts of water (Shah & Badiger, 2020). Under the spring rejuvenation program, we have carried out mechanical interventions in the Khulgad watershed of the Almora district in Uttarakhand, India, during the pre-monsoon period of 2023 (

Figure 5). Under this approach, the local community was involved after the stakeholders met and focused group discussions.

Moreover, the region selected for the recharge interventions was a landslide-free zone with a slope of less than 50%, which will reduce soil erosion and increase the chances of infiltration. After identifying the suitable location, various trenches and percolation pits were constructed for the rainfall recharge. The primary objective of the mechanical intervention is to develop a comparative discharge analysis of the springs and streams originating from the Khulgad watershed in pre and post-intervention scenarios.

Under the spring sanctuary development initiative, Negi & Joshi (2002) conducted a study on spring rejuvenation in the Dugar Gad micro watershed of Pauri-Garhwal, Indian Himalaya. They implemented engineering, vegetation, and social measures to improve water availability during the lean flow period (April-June). Their findings indicated that mechanical interventions positively affected spring rejuvenation. However, Negi & Joshi stressed the need for long-term monitoring to assess the full impact of these interventions. This includes comparing post-intervention data with historical discharge and demographic information to evaluate effectiveness. Similarly, efforts in Nagaland Mountain by the Land Resources and Rural Development Departments, NEIDA, and Tata Trusts involved springshed recharge activities on about 50 hectares. These activities included digging trenches, creating recharge ponds, building gabion structures, and planting trees, alongside regular monitoring of rainfall and spring discharge (Emn, 2019). Moreover, In Nepal and India, the pilot project by ICIMOD, ACWADAM, and HELVETAS in 2015 showed improvements in spring discharge in Dailekh and Sindhupalchok catchments within a year of implementing recharge interventions (Siddique et al., 2019).

In the Dhara Vikas program in Northeast India, trenches and pits were created to rejuvenate springs. However, there has been no direct scientific assessment of the effectiveness of these mechanical interventions on spring discharge (Azhoni et al., 2018). Additionally, Himalaya Sewa Sangh (HSS) and Himalaya Consortia for Himalayan Conservation (HIMCON) have installed slow sand filters in Uttarakhand's Henwal River valley, with the filtered water stored in tanks and distributed via pipelines (Sahay et al., 2019). Moreover, activist Chandan Nayal has planted over 60,000 oak trees and built numerous recharge structures in the Okhalkanda block of Kumaun. Despite his significant efforts for groundwater conservation, his work lacks scientific evaluation. Hence, this highlights the need for transdisciplinary collaboration and support to provide data-driven results and enhance the effectiveness of such initiatives. Overall, conservation, restoration and management activities need to be highly individualized and site-specific (Fraga et al., 2023).

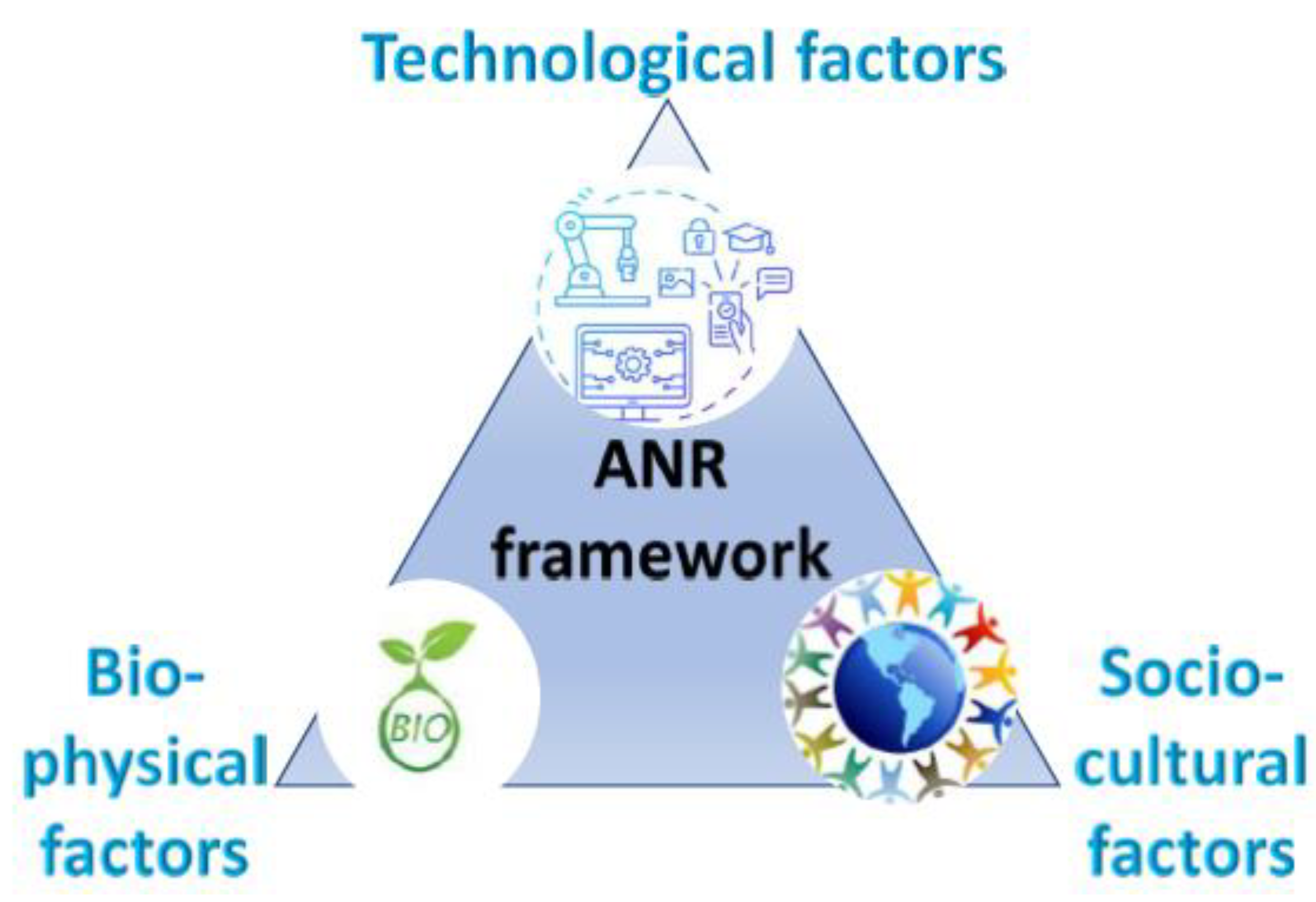

4.2. Assistive Natural Regeneration (ANR)

Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR) is an effective, cost-efficient method for rehabilitating degraded forests and grasslands. It involves controlling fires, restricting grazing, managing unwanted plant growth, and engaging local communities (Dugan et al., 2003). ANR is less expensive than traditional reforestation techniques and results in biologically diverse forests that benefit local populations.

ANR encompasses three dimensions: technological, bio-physical, and socio-cultural (including economic and institutional aspects) (Dugan et al., 2003). Successful implementation requires protecting the area from disturbances like fire and grazing, which allows ecological succession to occur. Shono et al. (2007) outlined a five-step methodology for ANR, though it can be adapted based on local conditions, resources, and goals. ANR is particularly suited for forest protection, biodiversity conservation, soil conservation, and establishing protective cover in hydrologically critical areas.

For effective ANR, ensuring a sufficient number of native seedlings and appropriate soil conditions is crucial. Adequate seed dispersal by biotic and abiotic agents also supports natural forest regeneration (Rosli & Zakaria, 2002). Successful ANR depends on matching site-specific species and understanding the ecological needs of the natural forest, which can be complex due to limited ecological knowledge (Kartawinata et al., 2001). Local communities often have valuable knowledge about their resources, which is sometimes underappreciated by experts and officials (Leach et al., 1999)

Figure 6.

Conceptual Framework of Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR) strategy for forest rehabilitation (modified after Sajise, 2003).

Figure 6.

Conceptual Framework of Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR) strategy for forest rehabilitation (modified after Sajise, 2003).

The socio-cultural and institutional dimensions are critical for the success of Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR) projects. These elements include the community’s values and the policies governing natural resource use. Community values involve the relationship between local people and their natural resources, including the economic benefits and protective practices that aid forest restoration.

In the Philippines, Community Based Resource Management (CBRM) projects have effectively protected areas from grassland fires (Sajise, 2003). ANR has been successfully implemented in countries like China, Nepal, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Sri Lanka under various names (Bay 2002; Sannai, 2003). For example, in Ifugao, the Philippines, ANR is used to restore forests on degraded grasslands (Dugan et al., 2003). In China, ANR is categorized into special and general types: Special ANR addresses cutover land with natural sowing capacity but lacking essential regeneration conditions, while General ANR involves artificial sowing and other treatments on barren or degraded lands.

A notable example of community-based ANR is in the Shyahidevi forest, Almora district, India. Local efforts to prevent forest fires have led to successful regeneration with native species like Banj (Quercus leucotrichophora), Deodar (Cedrus deodara), and Raga (Cupressus torulosa). This forest is a key recharge source for the Kosi River basin, and the sustained community involvement over 20 years has demonstrated the effectiveness of ANR as a model for sustainable development in the 14 recharge zones in the Kosi River basin (Rawat et al., 2018).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the Shyahidevi Reserve Forest of Almora, India, between 2012 and 2023 (Source of Photograph: Mr. Gajendra Pathak, Shitalakhet).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the Shyahidevi Reserve Forest of Almora, India, between 2012 and 2023 (Source of Photograph: Mr. Gajendra Pathak, Shitalakhet).

Overall, results suggest that ANR helps in soil and water conservation, biomass accumulation, and biodiversity protection and enhances ecosystem services (Yang et al., 2018), which could be thus implemented with high success in the Himalayan region. These socio-economic and institutional arrangements must be used to ensure that local communities will have both the responsibility and accountability for protecting and enhancing forest restoration through ANR or other appropriate means while at the same time securing the benefits that should accrue to them more sustainably and equitably.

5. Effectiveness of Various Scientific Interventions

The management of groundwater and spring water differs significantly from surface water, making it a complex task. In order to address the water-related challenges in the HKH region, the ultimate objective must be focused on the execution or effect of different scientific and community-based interventions for socio-economic gain. Supply-side improvements are prioritised alongside charting and safeguarding recharge zones, employing social or physical fences, and establishing capacity for para-hydrogeologists within the community. The springshed approach, as demonstrated by the Dhara Vikas program in Sikkim, India, has proven effective by addressing the entire catchment area rather than relying solely on political boundaries or traditional ridge-to-valley methods (Tambe et al., 2012). Nepal has similarly highlighted the value of this approach in revitalizing wetlands (Rijal, 2016). Implementing Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) can be transformative for sustainable groundwater management, as it not only enhances groundwater recharge but also improves water quality (Dillon et al., 2019; Dillon et al., 2020).

The adoption of hydrogeological mapping and the drawing of public investments have been made possible in large part by the joint efforts of local institutions and communities. For instance, a six-step strategy for spring revival in the HKH has been devised by ICIMOD and ACWADAM (Shrestha et al., 2017). A thorough approach was created for study and practice on reviving springs in the HKH region based on the lessons learnt from these efforts. The Sustainable Development Investment Portfolio (SDIP) of the Australian government was used to explore and revitalise springs in three districts of Bhutan and the Godavari landscape in Nepal. These activities have also been linked to an increase in spring discharge and a decrease in faecal coliform contamination (Buono, 2019; Jal Shakti, 2019; Tambe et al., 2020 a, b).

Groundwater management must start at the village level. Data from the MARVI project shows that effective groundwater collaboration and sustainable water sharing are feasible at local and aquifer scales. For long-term water security, groundwater management should be interdisciplinary, cross-departmental, and comprehensive (Maheshwari and Mehta, 2019). Baseline surveys by ICIMOD and ACWADAM are essential for substantiating the benefits of spring revival initiatives in mountainous areas (Shrestha et al., 2017). Similarly, CHIRAG’s (Central Himalayan Rural Action Group's) approach to mapping and managing springsheds with local involvement demonstrates effective knowledge transfer and capacity building. CHIRAG has also conducted recharge initiatives across ten distinct spring catchments in the Kumaun region of Uttarakhand (Bisht and Mahamuni, 2015). CHIRAG's strategy, supported by the Spring Initiative Partners, provides a model for state-wide spring conservation. Their spring atlas details essential procedures for systematic springshed management, from surveys to impact assessments, making it a valuable resource for ongoing projects.

6. Impact of Various Government Policies over Spring Hydrology

To effectively plan and assess spring revival efforts, a thorough understanding of water use, distribution patterns, and existing governance systems is crucial. Engaging researchers and stakeholders is an effective way to enhance the broader impacts of research and to investigate questions related to water sustainability within social-ecological systems (Ferguson et al., 2018). In the HKH region, water lifting schemes have helped supplement water supplies as spring flows declined, providing year-round access for villagers and easing the burden on women who previously had to fetch water from afar. However, this reliance on external water sources has led to reduced local involvement in water conservation, leaving springs unprotected and causing hydrological imbalances. Unplanned development in key recharge zones has increased surface runoff and diminished land recharge potential, exacerbating issues like flooding, soil loss, and landslides.

Furthermore, pumping water from distant sources is vulnerable to disruptions from extreme weather, pipe damage, power outages, or source changes. These engineering solutions, characterized by high costs and heavy capital investments, are unsustainable long-term, especially with catchment degradation and climate change impacting distant sources. To address these challenges, integrating nature-based solutions such as springshed management and leveraging indigenous knowledge is essential. Despite the potential and existing research, these local practices are often underutilized by governments and municipalities (Singh & Pandey, 2020). Effective community involvement and local knowledge are crucial for the success of Assisted Natural Regeneration (ANR) projects. To ensure communities are motivated to participate, they must see tangible benefits from the restoration efforts, particularly in the long-term products and services. This can be achieved by promoting high-value, market-oriented products, such as medicinal plants, provided they are harvested sustainably. Governments can also contract local communities to protect forests and implement ANR, but clear agreements on the distribution of benefits are essential. A well-designed national land-use policy that integrates ANR technologies for forest restoration will enhance the overall effectiveness and efficiency of these efforts.

In Darjeeling, India, the central town relies on a formal, centralized water supply, while the surrounding areas depend on informal sources such as water tankers and springs. Shah and Badiger (2020) highlight that the water crisis in Darjeeling stems from a complex interplay of issues, including political indifference, inadequate funding, poor coordination between state and regional authorities, and weaknesses in local governance. To address this crisis, several initiatives are underway. Notably, two programs show promise: one under the AMRUT plan (Chettri, 2016) and the other funded by the National Adaptation Fund (Department of Environment, 2016).

In India, the Dhara Vikas spring rejuvenation program, part of the National Employment Guarantee Scheme, has seen success with mechanical interventions like trenching and pit digging in the Himalayan States. However, there is a lack of detailed scientific studies to evaluate the full impact of these interventions (Azhoni & Goyal, 2018). Similarly, the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), which aims to provide safe and adequate tap water to every rural household by 2024, also emphasizes sustainability through recharge and reuse, greywater management, and rainwater harvesting. JJM prioritizes community involvement as a core component, including extensive information collection, education, and communication. Additionally, integrating community-centric approaches into national plans such as the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) and other missions (e.g., the National Water Mission, National Mission on Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem) can further support adaptation and mitigation efforts at the national level (Vijhani et al., 2023).

7. Private-Public Partnership in Water Resource Management

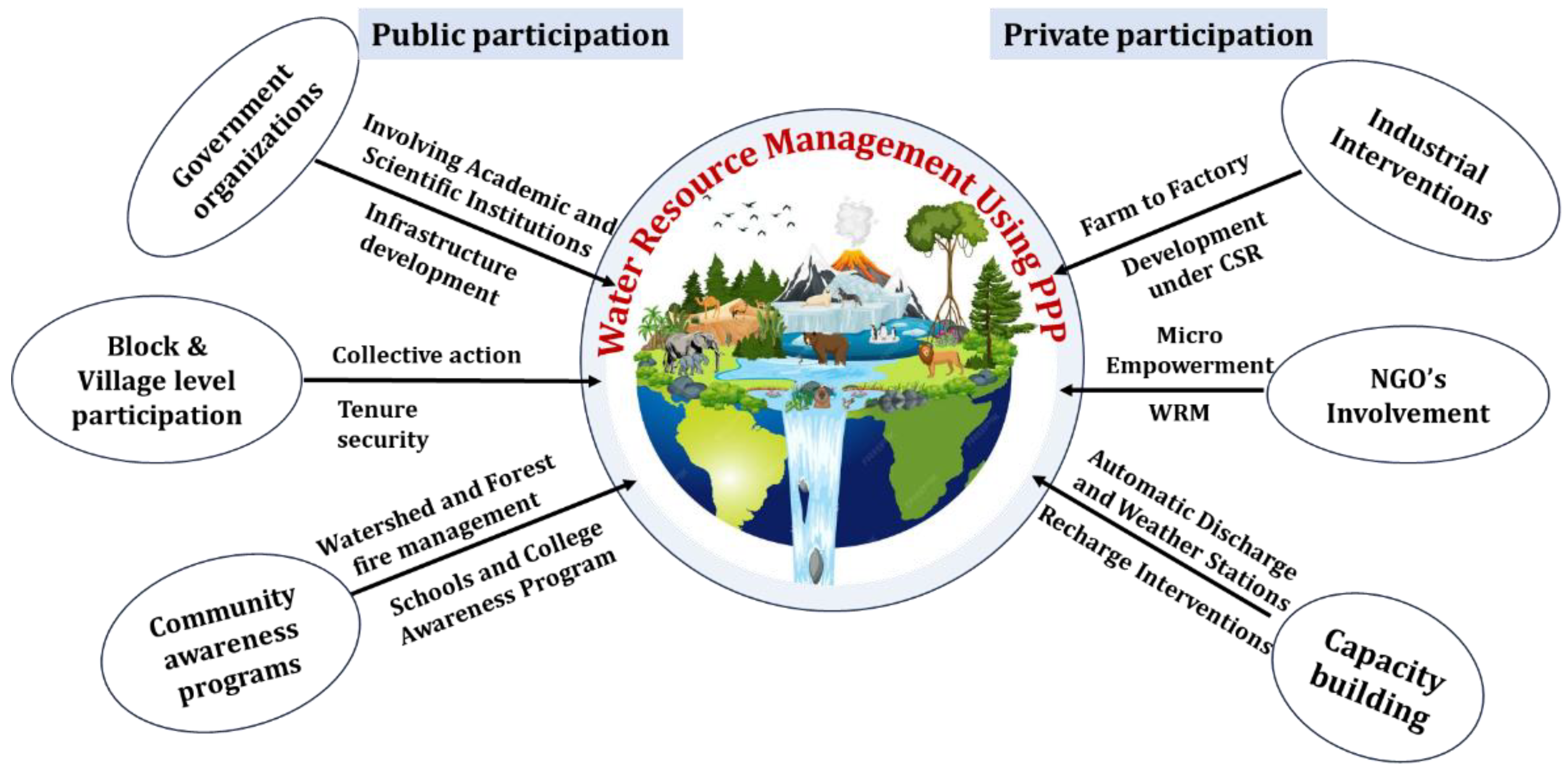

The Public-Private Partnership (PPP) model has recently gained prominence as a strategy for enhancing water resource management (Lima et al., 2021). Participatory research methods tackle various issues in water research, such as the undervaluation of local knowledge, the exclusion of marginalized communities, the bias toward elite and expert viewpoints, and exploitative research practices (Roque et al., 2022). While involving major stakeholders in decision-making can be resource-intensive, it can reduce political uncertainty and foster broader acceptance of policies (Van Aalst et al., 2008). Research across disciplines shows that some government-driven policies have led to natural resource degradation, whereas some public-private models have supported sustainable development (Ostrom, 2009). Isolated scientific studies often address issues with varying concepts and languages, leaving gaps in sustainable development understanding. Ostrom (2009) proposed a common framework to integrate scientific knowledge and socio-ecological systems for achieving sustainability goals. Studies indicate that wealth and income disparities within rural groups can lead to local leaders who effectively organize and manage resources (Leach et al., 1999; Vedeld, 2000; Poteete & Ostrom, 2004; Phetkongtong, and Nulong, 2022).

Water resources are crucial for the socio-economic development of the HKH region, which comprises the northeast hills, central hills, and northwest hills. Despite ample precipitation, water shortages affect agriculture and drinking needs. Thus, it is essential to explore options to increase crop water productivity and meet community water requirements. This includes improving water supply and conservation through technological advancements, restoring forest-water links, constructing water harvesting structures, enhancing water use efficiency through agronomic measures, and adopting a watershed management approach.

Figure 8.

Collective action for water resource management with PPP model.

Figure 8.

Collective action for water resource management with PPP model.

Before 1993, Nepal's forest management was largely ineffective, with minimal public involvement and no incentives for conservation, leading to extensive deforestation and overgrazing. The introduction of forestry legislation in 1993 marked a shift, transferring forest control to local public organizations. This change, supported by community-led management, nearly doubled the country's forest cover, according to recent NASA-funded research (Van et al., 2021). This demonstrates the effectiveness of self-governance, though it also highlights the risk of over-harvesting when resources are shared. To address these issues, external regulation or privatization can be impactful (Hardin, 1968). Additionally, providing special benefits to communities in recharge zones can help mitigate forest fires, reduce degradation, prevent soil loss, and enhance surface infiltration. An integrated Land and Water Resource Management (ILWRM) approach can be employed at the watershed level to align interests and demands from both upstream and downstream areas for more effective land and water management (Nepal et al., 2014).

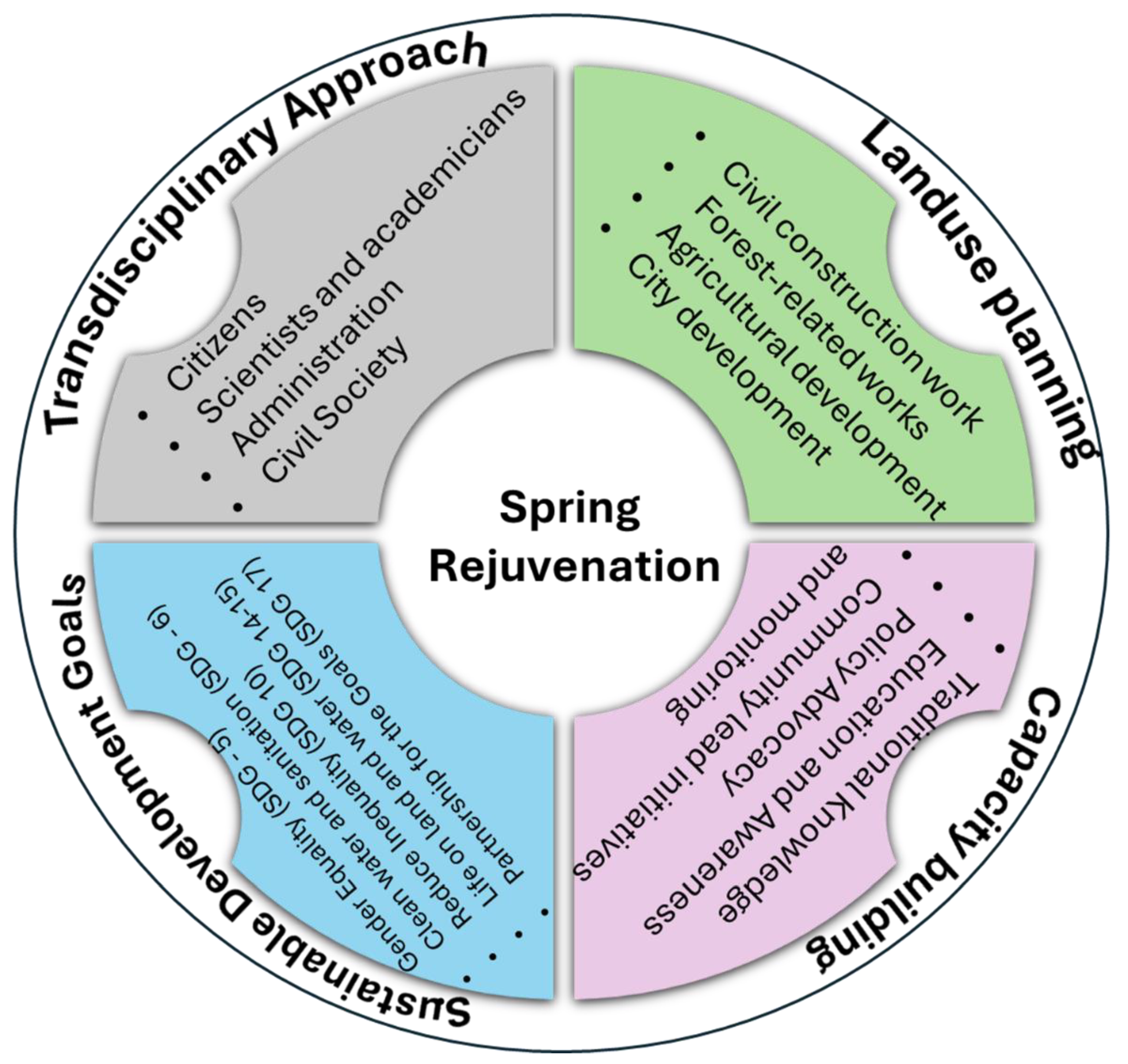

8.. Converting Research into Action Research / Transdisciplinary Approach

Using advanced tools is essential for planning and managing complex systems effectively (Andreu et al., 1996). To translate research into actionable strategies, a transdisciplinary approach is needed to integrate stakeholders from both upstream and downstream areas for better land and water management (Maheshwari et al., 2014).Analysis of water scenarios in the Hindukush Himalayan region over three decades has led to the development of a simple, sustainable economic model. Four key factors identified through literature reviews and SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timely) analysis for effective research translation are: adopting a transdisciplinary approach, land-use planning, capacity building, and achieving sustainable development goals (

Table 2,

Table 3,

Figure 9). Tools like AQUATOOL have proven useful for decision support in complex watersheds (Andreu et al., 1996). Additionally, the open-source InVest (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs) tool has been recommended for mapping and valuing spring products and services, providing a systematic inventory of the spring ecosystem (Gosavi et al., 2021).

8.1. Landuse Planning

Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) planning has become crucial in adapting to changing climatic conditions. Effective management of recharge zones can enhance ecosystem restoration and improve the recharge rate and water residence time of mountain aquifer systems. Civil construction in the HKH region should prioritize water resources and their sustainability as key components of urban planning. Forests and native plants are central to the hydrological system in the HKH, but shifts in plantation practices have led to an increase in pine forests at the expense of mixed or native species. Pine species, requiring significant water and producing needle-like leaves, hinder the survival and regeneration of native plants and have contributed to an increase in forest fires (Cooper, 1960; Dobriyal & Bijalwan, 2017).

To mitigate fire risks, integrating local communities, NGOs, and community-based organizations (CBOs) is essential. In Uttarakhand, Van Panchayats have long managed forests successfully, but forest communities need to adapt modern strategies to manage fire risks. Establishing Forest Self-Help Groups (FSHGs) or Forest Special Purpose Vehicles (FSPVs) can turn pine needles into useful resources, such as bio-briquettes, compost, or composite materials (Dobriyal & Bijalwan, 2017). In the HKH Mountains, both natural and human-made forests are heavily utilized, and the removal of leaf litter and grazing by livestock have been significant contributors to the degradation of forest hydrological functioning (Ghimire et al., 2014).

Restoring watershed hydrological performance requires more than just replanting trees; ongoing management is crucial to balance resource use and spring renewal (Panwar, 2020). Springs are vital in the HKH region, but overreliance on groundwater could lead to adverse effects due to the fragile nature of mountain aquifers. Therefore, LULC planning and recharge programs must be well-conceived and long-term. Approaches that account for the vulnerabilities of mountain ecosystems and focus on ecological restoration are necessary. Urban centers in the HKH face significant water challenges exacerbated by climate change, underscoring the need for sustainable urban planning and stakeholder accountability.

8.2. Capacity Building

In remote regions, gathering baseline data and establishing monitoring networks are challenging tasks. Effective spring management necessitates cooperation among researchers, government officials, and local communities, with a strong emphasis on enhancing local capabilities. Citizen science initiatives are valuable for increasing awareness, collecting detailed field data, and ensuring ongoing monitoring. Combining satellite-based hydrology and meteorology data with springshed monitoring improves the understanding and prediction of spring conditions, leading to more effective management strategies (Shukla & Sen, 2021). Gosavi et al. (2021) identified six key factors for assessing spring ecosystem health: aquifer and water quality, geomorphology, human impacts, institutional context, habitat, and biota. Springs, as common-pool resources, benefit from Ostrom's (1990) Socio-Ecological System (SES) framework for sustainable watershed management (Mirnezami et al., 2018). The MARVI project demonstrates a transdisciplinary approach by integrating local, indigenous, and scientific knowledge into a unified framework, improving water security and adaptability in evolving landscapes (Maheshwari & Mehta, 2019; Drenkhan et al., 2023).

A lack of detailed hydrogeological data, such as precipitation and discharge, contributes to uncertainties in assessing climate change and human impacts on spring hydrology. The absence of a comprehensive spring inventory hampers research on hydrological characterization and vulnerability (Panwar, 2020). Promoting mobile applications like MyWell at the village level, with support from local leaders and para-hydrologists, can facilitate mapping and monitoring of spring hydrology and water quality. Training local school students and women to gather basic meteorological and hydrological data can further support these efforts. Establishing a central agency to collect and integrate data on village boundaries, population density, water demand, and land use will aid in developing effective management plans for aquifers and springs at both local and regional scales.

8.3. Adopting the Transdisciplinary Mode of Research and Rejuvenation

Transdisciplinary work integrates diverse disciplines and stakeholders to address real-world problems and produce sustainable outcomes. Pohl et al. (2021) outline three phases of transdisciplinary research: Framing, Analyzing, and Exploring. Maheshwari et al. (2014) define transdisciplinary work as collaborative efforts involving researchers and non-academic participants working towards a common goal to improve complex situations. Understanding traditional water harvesting and conservation methods is crucial before applying new scientific methods. While traditional practices provide valuable insights, they may not always be suitable for contemporary challenges. Modern scientific approaches can enhance water management by offering new technologies and methodologies. For example, Maheshwari et al. (2023) and Dollin et al. (2023) conducted an 11-month training program for Young Water Professionals (YWPs) as part of the Situation Improvement Projects (SUIPs) and Australia India Water Centre (AIWC). This program enhanced YWPs' skills in project planning, implementation, and management using a transdisciplinary approach.

Several frameworks demonstrate the effectiveness of transdisciplinary approaches in societal development. For example:

i2s (Integration and Implementation science) Framework: Focuses on complex societal and environmental research through Synthesizing Knowledge, Managing Knowledge, and Supporting Improvement (Bammer, 2017).

CANDHY (Citizen and Hydrology) Framework: Integrates traditional Aboriginal Australian knowledge with modern hydrology and policy through collaboration among hydrologists, public servants, and researchers (Nardi et al., 2022).

ANU Framework: Emphasizes a transdisciplinary approach with characteristics like being Change-oriented, Systemic, Context-based, Pluralistic, Interactive, and Integrative (Bammer et al., 2023).

Overall, in the HKH region, addressing sustainable watershed management challenges requires local springshed interventions, regional recommendations, and effective stakeholder participation (Erostate et al., 2020).

8.4. Promoting the Suitable Development Goals

Groundwater accounts for 97% of the world’s freshwater, making its sustainability a critical concern. The UN-Water Sustainable Development Global Acceleration Framework, launched in 2020, highlights the importance of capacity development for achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6, which focuses on ensuring water availability and sustainable management. In the HKH region, women often spend significant time collecting water from distant sources, which limits their opportunities for other productive activities. Despite their central role in household water management, women are underrepresented in water resource planning. Involving women in water management is crucial for achieving gender equity (SDG 5) and reducing global inequalities. Improving water availability can enhance the economic, physical, and mental well-being of people, contributing to reduced inequalities (SDG 10). The HKH region, with its potential for organic food and milk production, requires a steady water supply. Enhancing water quantity and quality will boost livelihoods and support sustainable food production (SDG 12). Effective spring management will also improve environmental flows and support aquatic biodiversity (SDG 14). Partnerships at various levels—local, national, and global—are essential for achieving SDG 17, which focuses on strengthening global partnerships and leveraging technology to meet sustainable development goals by 2030.

9. Conclusions

The Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region, vital for millions, faces severe water scarcity, impacting rural agriculture and driving urban migration. This paper reviews the challenges of declining natural spring discharge in the HKH and assesses the role of a transdisciplinary approach in addressing these issues. Authors’ experiences in Himalayan springs and transdisciplinary water resource management over the last 30 years have helped to develop an ethnographic review of the Himalayan Spring.

Climate change, unsustainable human activities, and rising water demand are major drivers of reduced spring health. Factors such as altered precipitation, rising temperatures, deforestation, land-use changes, and infrastructure development have led to diminished spring discharge and poorer water quality, resulting in agricultural losses, migration, and socio-economic disruptions.

The study emphasizes the need for a transdisciplinary approach that integrates scientific expertise with community-based interventions. Water management involves not only technical aspects but also human values, behaviors, policy, and politics. By involving scientists, local villagers, and stakeholders, the study advocates for holistic solutions that address social, ecological, and economic dimensions of spring management.

Public-private partnerships (PPP) and participatory approaches are highlighted as effective for large-scale spring rejuvenation. Leveraging the strengths of both sectors and engaging local communities can achieve sustainable spring management. The study also underscores the importance of capacity development and knowledge transfer, including training para-hydrogeologists, mapping recharge areas, and implementing sustainable land-use practices.

In conclusion, addressing the declining spring discharge in the HKH region requires a transdisciplinary, community-centric approach. Integrating scientific knowledge with local wisdom, fostering stakeholder collaboration, and empowering communities can help overcome water scarcity challenges and achieve sustainable water resource management in the HKH region. This review also highlights the progress achieved in Khulgad spring shed management through targeted interventions.

Author Contributions

Neeraj Pant; Dharmappa Hagare: Conceptualization, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Writing-Original draft preparation, Basant Maheshwari: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Reviewing and Editing, Shive Prakash Rai: Visualization, Supervision, Reviewing and Editing, Megha Sharma: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Writing-Original draft preparation, Jen Dollin; Vaibhav Bahmoria: Methodology, Writing-Original draft preparation, Supervision, Reviewing and Editing, Nijesh Puthiyottil: Software, Data curation, Writing-Original draft preparation, and Jyothi Prasad: Visualization, Reviewing and Editing.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

While preparing this work, the authors used the OpenAI-ChatGPT Tool to improve the manuscript’s readability and language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the publication's content.

Acknowledgments

This project was partially funded by the Scheme for Promoting Academic and Research Collaboration (SPARC) of the De-partment of Human Resources, India. The project team gratefully acknowledges the SPARC funding. Also, the authors express their sincere thanks to Western Sydney University for providing the scholarship and research infrastructure funding for the first author. In addition, the support provided by several scientists such as Prof. J.S. Rawat, Dr. Kireet Kumar, Prof. S.K. Jain and Prof. Sumit Sen is greatly acknowledged. Further, the authors extend their sincere thanks to the local community leaders such as Mr. R.D. Joshi, Mr. Gajendra Singh Pathak, Mr. Chandan Nayal and Mr. Chandan Bhoj. Finally, but not the least, the authors thank the field monitoring team, and the community of Khulgad, Uttarakhand for their unwavering support for the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aayog, N.I.T.I. Inventory and revival of springs in the Himalayas for water security; Dept. of Science and Technology, Government of India: New Delhi, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ACWADAM; R Hydrogeological Studies and Action Research for Spring Recharge and Development and Hill-top Lake Restoration in Parts of Southern District, Sikkim State. Advanced Center for Water Resources Development and Management (ACWADAM) and Rural Management and Development Department (RMDD), Government of Sikkim, Gangtok. 2011. http://sikkimsprings. org/dv/research/ACWADAM report.pdf.

- Alvarez-Garreton, C.; Lara, A.; Boisier, J.P.; Galleguillos, M. The impacts of native forests and forest plantations on water supply in Chile. Forests 2019, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, J.; Capilla, J.; Sanchís, E. AQUATOOL, a generalized decision-support system for water-resources planning and operational management. Journal of hydrology 1996, 177, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Deodhar, A.; Kumar, U.S.; Khatti, V.S. Water quality of few springs in outer Himalayas–A study on the groundwater–bedrock interactions and hydrochemical evolution. Groundwater for sustainable development 2015, 1, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhoni, A.; Goyal, M.K. Diagnosing climate change impacts and identifying adaptation strategies by involving key stakeholder organisations and farmers in Sikkim, India: Challenges and opportunities. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 626, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballav, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Gosavi, V.; Dimri, A.P. Projected changes in winter-season wet days over the Himalayan region during 2020–2099. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2021, 146, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balocchi, F.; Flores, N.; Arumí, J.L.; Iroumé, A.; White, D.A.; Silberstein, R.P.; Ramírez de Arellano, P. Comparison of streamflow recession between plantations and native forests in small catchments in Central-Southern Chile. Hydrological Processes 2021, 35, e14182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balocchi, F.; Rivera, D.; Arumi, J.L.; Morgenstern, U.; White, D.A.; Silberstein, R.P.; Ramírez de Arellano, P. An Analysis of the Effects of Large Wildfires on the Hydrology of Three Small Catchments in Central Chile Using Tritium-Base. 2022.

- Bammer, G. Should we discipline interdisciplinarity? Palgrave Communications 2017, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammer, G.; Browne, C.A.; Ballard, C.; Lloyd, N.; Kevan, A.; Neales, N.; Nurmikko-Fuller, T.; Perera, S.; Singhal, I.; van Kerkhoff, L. Setting parameters for developing undergraduate expertise in transdisciplinary problem solving at a university-wide scale: a case study. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2023, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, R.; Hope, A. Streamflow response to fire in large catchments of a Mediterranean-climate region using paired-catchment experiments. J. Hydrol. 2010, 388, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, R.R.; Tague, C.L. The impact of wildfire on baseflow recession rates in California. Hydrol. Process. 2017, 31, 1662–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartarya, S.K.; Valdiya, K.S. Landslides and erosion in the catchment of the Gaula River, Kumaun Lesser Himalaya, India. Mountain Research and Development 1989, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastin, L.; Gorelick, N.; Saura, S.; Bertzky, B.; Dubois, G.; Fortin, M.J.; Pekel, J.F. Inland surface waters in protected areas globally: Current coverage and 30-year trends. PloS one 2019, 14, e0210496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batelis, S.-C.; Nalbantis, I. Potential Effects of Forest Fires on Streamflow in the Enipeas River Basin, Thessaly, Greece. Environ. Process. 2014, 1, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, D. Rehabilitation of degraded lands in humid zones of Africa. A report prepared for International Union of Forest Research Organizations, Global Forest Information Service (GFIS) project. Kumasi, Ghana. 2002.

- Berg, A.; Findell, K.; Lintner, B.; Giannini, A.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Van Den Hurk, B.; Lorenz, R.; Pitman, A.; Hagemann, S.; Meier, A.; Cheruy, F. Land–atmosphere feedbacks amplify aridity increase over land under global warming. Nature 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.U.; Nisa, A.U.; Sabha, I.; Mondal, N.C. Spring water quality assessment of Anantnag district of Kashmir Himalaya: towards understanding the looming threats to spring ecosystem services. Applied Water Science 2022, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, B.K. and Mahamuni, K., 2015, May. CHIRAG’s spring protection programme. In PowerPoint presented at 3rd annual meeting of the springs initiative, Bhimtal, Uttarakhand, May (Vol. 15).

- Bolch, T.; Kulkarni, A.; Kääb, A.; Huggel, C.; Paul, F.; Cogley, J.G.; Frey, H.; Kargel, J.S.; Fujita, K.; Scheel, M.; Bajracharya, S. The state and fate of Himalayan glaciers. Science 2012, 336, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, T.C.; Doherty, S.J.; Fahey, D.W.; Forster, P.M.; Berntsen, T.; DeAngelo, B.J.; Flanner, M.G.; Ghan, S.; Kärcher, B.; Koch, D.; Kinne, S. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment. Journal of geophysical research: Atmospheres 2013, 118, 5380–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, D.; Rojas, M.; Boisier, J.P.; Valdivieso, J. Climate change impacts on hydroclimatic regimes and extremes over Andean basins in central Chile. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.E.; Zhang, L.; McMahon, T.A.; Western, A.W.; Vertessy, R.A. A review of paired catchment studies for determining changes in water yield resulting from alterations in vegetation. J. Hydrol. 2005, 310, 28–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, S.; Büscher, C.; Hessels, L.K. Towards transdisciplinarity: A water research programme in transition. Science and Public Policy 2018, 45, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Bremmer, C.N. Highland-lowland interactions in the Ganges Brahmaputra river basin: a review of published literature. 1989.

- Buono, J. Spring protection and management: Context, history and examples of spring management in India. Groundwater development and management: Issues and challenges in South Asia, 2019; pp. 227–241.

- Chettri, V. Centre Funds Darjeeling Water Supply Rejig. Telegraph India, Siliguri, 26 April 2016. See: https://www. telegraphindia.com/1160426/jsp/siliguri/story_82251.jsp.

- Chiew, F.H.S.; McMahon, T.A. Modelling the impacts of climate change on Australian streamflow. Hydrol. Process. 2002, 16, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokkalingam, U.; De Jong, W. Secondary forest: a working definition and typology. The International Forestry Review 2001, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.F. Changes in vegetation, structure, and growth of southwestern pine forests since white settlement. Ecological monographs 1960, 30, 130–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K. Climate change forces Uttarakhand farmers to migrate (thethirdpole.net). 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dehn, M.; Bürger, G.; Buma, J.; Gasparetto, P. Impact of climate change on slope stability using expanded downscaling. Engineering Geology 2000, 55, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Environment. Detailed Project Report for National Adaptation Fund: Rain Water Harvesting and Sustainable Water Supply to the Hilly Areas in Darjeeling as an Adaptive Measure to Potential Climate Change Impacts. 2016.

- Dillon, P.; Page, D.; Vanderzalm, J.; Toze, S.; Simmons, C.; Hose, G.; Martin, R.; Johnston, K.; Higginson, S.; Morris, R. Lessons from 10 years of experience with Australia’s risk-based guidelines for managed aquifer recharge. Water 2020, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, P.; Stuyfzand, P.; Grischek, T.; Lluria, M.; Pyne, R.D.G.; Jain, R.C.; Bear, J.; Schwarz, J.; Wang, W.; Fernandez, E.; Stefan, C. Sixty years of global progress in managed aquifer recharge. Hydrogeology journal 2019, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, A.P.; Dash, S.K. Wintertime climatic trends in the western Himalayas. Climatic change 2012, 111, 775–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobriyal, M.; Bijalwan, A. Forest fire in western Himalayas of India: a review. New York Science Journal 2017, 10, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dollin, J.; Hagare, D.; Maheshwari, B.; Packham, R.; Reynolds, J.; Garg, A.; Harris, H.; Issac, A.M.; Meher, A.K.; Shivakumar, S.K. A reflective evaluation of young water professionals' transdisciplinary learning. World Water Policy 2023, 9, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, W. and Sukhija, B.S., 2008. Climate change and groundwater: a short review (Vol. 288, No. 1, pp. 1–12). London: The Geological Society of London.

- Drenkhan, F.; Buytaert, W.; Mackay, J.D.; Barrand, N.E.; Hannah, D.M.; Huggel, C. Looking beyond glaciers to understand mountain water security. Nature Sustainability 2023, 6, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudeja, D.; Bartarya, S.K.; Khanna, P.P. Ionic sources and water quality assessment around a reservoir in Tehri, Uttarakhand, Garhwal Himalaya. Environmental earth sciences 2013, 69, 2513–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, P.C., Durst, P.B., Ganz, D.J. and PJ, M., 2003. Advancing assisted natural regeneration (ANR) in Asia and the Pacific. RAP PUBLICATION, 19.

- Dyurgerov, M.B. and Meier, M.F., 2005. Glaciers and the changing Earth system: a 2004 snapshot (Vol. 58, p. 23). Boulder: Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado.

- Ellison, D.; Morris, C.E.; Locatelli, B.; Sheil, D.; Cohen, J.; Murdiyarso, D.; Gutierrez, V.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Creed, I.F.; Pokorny, J.; Gaveau, D. Trees, forests and water: Cool insights for a hot world. Global environmental change 2017, 43, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emn (2019) Nagaland: Springshed development project to cover 100 villages - Eastern Mirror. Available at: https://easternmirrornagaland.com/nagaland-springshed-development-project-to-cover-100-villages/.

- Erostate, M.; Huneau, F.; Garel, E.; Ghiotti, S.; Vystavna, Y.; Garrido, M.; Pasqualini, V. Groundwater dependent ecosystems in coastal Mediterranean regions: Characterization, challenges and management for their protection. Water research 2020, 172, 115461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. International journal of production economics 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- <monospace>Ferguson, L.; Chan, S.; Santelmann, M.V.; Tilt, B. Transdisciplinary research in water sustainability: What’s in it for an engaged researcher-stakeholder community? . Water Alternatives 2018, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- <monospace>Fraga, N.S.; Cohen, B.S.; Zdon, A.; Mejia, M.P.; Parker, S.S. Floristic Patterns and Conservation Values of Mojave and Sonoran Desert Springs in California. Natural Areas Journal 2023, 43, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, L.E.; Underwood, E.C.; Flint, A.L.; Hollander, A.D. Characterizing the Influence of Fire on Hydrology in Southern California. Nat. Areas J. 2019, 39, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreaud, R.; Alvarez-Garreton, C.; Barichivich, J.; Boisier, J.P.; Christie, D.A.; Galleguillos, M.; LeQuesne, C.; McPhee, J.; Zambrano-Bigiarini, M. The 2010–2015 mega drought in Central Chile: Impacts on regional. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017.

- Ghimire, C.P.; Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Lubczynski, M.W.; Bonell, M. Negative trade-off between changes in vegetation water use and infiltration recovery after reforesting degraded pasture land in the Nepalese Lesser Himalaya. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2014, 18, 4933–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.; Prepas, E.; McEachern, P. Quantitative comparison of lake throughflow, residency, and catchment runoff using stable isotopes: Modelling and results from a regional survey of Boreal lakes. J. Hydrol. 2002, 262, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]