1. Introduction

Neisseria meningitidis is causative agent of invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) that is characterized by severe illness such as meningitis and septicemia. Among the 12 known serogroups of

N. meningitidis that are defined by the antigenicity of the meningococcal capsule, six—A, B, C, W, X, and Y—are responsible for the vast majority of IMD cases around the globe [

1]. Moreover, meningococcal isolates can be classified according to their genotypes into sequence types (ST) which can be clustered into clonal complexes (CC). The sequence data that allow this genotyping can now be extracted from whole genome sequences (WGS) using molecular tools available on the PUBMLST platform (

https://pubmlst.org/). Several CC are considered hyperinvasive and are responsible for most of IMD cases: CC11, CC32, CC41/44 and CC269 [

2].

Nevertheless, the distribution of these serogroups is not static; it varies geographically and fluctuates over time due to shifts in population immunity, introduction of vaccination programs, and localized outbreaks. An illustrative example of this geographic variability is the emergence of serogroup X in Africa over the past decade. While serogroup X is historically rare in Europe, the sub-Saharan region—notably within the “meningitis belt”—has experienced a rising number of

N. meningitidis X infections since 2006. This emergence has been particularly notable in countries such as Nigeria, Niger and Burkina Faso, where ongoing surveillance has detected significant increases in serogroup X–induced IMD, culminating in substantial outbreaks in 2010 and 2012 [

2].

However, beyond these six common serogroups, the less frequent or “rare serogroups” of

N. meningitidis including E and Z, non-groupable (NG) isolates and serogroup X in Europe, have also been sporadically implicated in IMD cases. Such isolates constitute a marginal proportion of overall IMD cases in the general population. The incidence and pathogenicity of these rare serogroups are les described, given their minimal impact on public health in comparison to the more prevalent serogroups, and as a result, literature on their epidemiology remains limited [

2]. Despite this, some studies suggest that patients with terminal complement pathway deficiencies exhibit higher susceptibility to both rare meningococcal serogroups (like serogroup E) and NG strains, being inherently defective in complement-mediated bacterial clearance [

3]. Additionally, recent advances in monoclonal antibody therapies, such as eculizumab, have revolutionized the management of diseases like paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) and atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (aHUS). However, these treatments also induce acquired complement deficiencies by specifically inhibiting the terminal complement pathway, leaving treated patients vulnerable to infections from encapsulated bacterial pathogens, including rare meningococcal serogroups[

4].

While current vaccines targeting serogroup B (4CMenB and fHbp bivalent vaccines) are also effective against other highly prevalent serogroups such as C, W and Y [

5], there is limited data regarding their efficacy against rare serogroups, such as serogroup E. Given this uncertainty, further research is required to assess whether existing vaccination strategies provide adequate protection against these less common isolates.

The present study aims to explore and describe the cases of IMD caused by rare serogroups, other than A, B, C, W, and Y, using the database of the National Reference Center for meningococci and Haemophilus influnezae in France, covering a 10-year period from 2014 to 2023. This analysis will provide fresh insights into the epidemiology and genomic features of infections caused by these seldom-addressed serogroups, particularly in vulnerable populations such as complement-deficient individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of the Study Cohort

In France, IMD is mandatorily reported. Epidemiological data on cases and serogroup distribution have been under close surveillance for several decades as part of the mission of our laboratory as a National Reference Center for Meningococci and Haemophilus influnezae (NRCMHi). We therefore retrospectively screened our database for all IMD cases (detection of Nm by culture and/or PCR from sterile sites) received between 2014 and 2023 and extracted epidemiological data (sex, age and early mortality) and clinical data, including clinical manifestations as well as underlying comorbidities.

2.2. Characterization of Clinical Isolates

IMD cases were biologically confirmed and grouped by culture and/or PCR. Full typing was performed using Whole Genome Sequencing by next generation sequencing for cultured isolates. Primary samples underwent Sanger sequencing-based multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Genotypic data (ST and CC) were extracted using tools available on the PUBMLST.org databases. All sequences are available in this database by filtering on “country=France” and Period (>2013 and <2024).

2.3. Bactericidal Activity Assays and Prediction of Strain Vaccine Coverage

We conducted a serum bactericidal assay (SBA) using sera from subjects vaccinated with the 4CMenB vaccine and compared the bactericidal titers before and after vaccination against three isolates of serogroup E using human complement, as previously described [

6]. Predictions of coverage by vaccines targeting group B isolates using the MenDeVar approach [

7] was extracted using tools available in the PUBMLST.org databases. This method predicts vaccine coverage based on the alleles of genes encoding vaccine antigens present in a given isolate. Isolates were classified as “covered” if they had at least one allele encoding a covered peptide or as “non-covered” if all alleles encoded uncovered peptides. Isolates were classified as “unpredictable” if all the alleles encoded peptides for which available data are insufficient to predict coverage or non-coverage.

2.4. Measure of Complement Deposit on Bacterial Surface

Isolates of each serogroup of N. meningitidis were grown overnight in a GC agar plate with supplements (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Illkirch, France). A suspension containing 2x106 CFU diluted in 50µl of Hanks balanced salt solution supplemented with 0.15 mM calcium chloride and 0.5 mM magnesium chloride (HBSS++) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Illkirch, France) (HBSS++) with 1%BSA were mixed with 50µl of normal sera from consent anonymous donors in a 96-wells plate and incubated for 30 min at 37° C, 5% CO2. After the incubation, the bacteria were washed in HBSS++ with 1%BSA and then resuspended in a solution containing the FITC-conjugated anti-human C5b-C9 antibody (clone aE11 FITC conjugated antibody (HycultBiotech)) diluted to 1:50 and incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Unstained bacteria served as negative control. After incubation, the bacteria were washed twice in HBSS++ with 1%BSA, resuspended with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution, and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. After incubation, the plate was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min and resuspended in 100 µl HBSS++ with 1%BSA. The plate was acquired using the CytoFlex S (Beckman Culture) and the data were processed using FlowJo version 10.4.1 (BD Biosciences).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of IMD Cases of Unusual Serogroups

Screening of the NRCMHi database identified 3610 IMD cases for the period 2014-2023. Serogroup distribution of the 3610 IMD cases was as follows: 1784 (49.4%) were serogroup B, 627 (17.4%) were serogroup C, 575 (15.9%) were serogroup W, 565 (15.7%) were serogroup Y, and 59 (1.6%) were other serogroups (

Table 1). These other serogroups included isolates of serogroups E, X and Z in addition to non-groupable isolates (all referred thereafter as unusual groups). The IMD cases corresponding to these 59 isolates had a male/female ratio of 1.1, similar to that of the usual serogroups (1.0). The median age for these 59 IMD cases (21.5 years) was also comparable to that of the usual serogroup IMD cases (B, C, W and Y) (22.3 years) (

Table 1). It is noteworthy that serogroup B cases play a major role in explaining this median figure, as they account for half the number of cases of the usual serogroups, while the median ages for cases due to serogroups C, W and Y were higher than those of the other serogroups (

Table 1).

The 59 cases of unusual groups were confirmed by culture (n=38, 64.4%), by PCR (n=19; 32.2 %) and in 2 cases by both culture and PCR (3.4%). Serogroup X was the most frequent (n=21; 35.6%) among capsulated isolates followed by serogroup E (n=11, 18.6%); one isolates (1.7%) was of serogroup Z and 26 isolates (44.1%) were non-groupable.

The overall percentage of the unusual groups was 1.6%, with a non-significant trend towards an increase in the last three years (p=0.09). This percentage varied yearly from 0.5% (in 2014 and 2018) to 4.7% (in 2021). The distribution of clinical forms of IMD was also similar to that among IMD cases due to usual groups, mostly featuring bacteremia and/or meningitis. Cases associated with non-meningeal forms (pneumonia, abdominal presentation, or arthritis) were also present in 20% of the 59 cases.

WGS or MLST were only available for 54 cases (91.5%). 15 clonal complexes were identified among 46 isolates while 8 isolates did not belong to any known clonal complex and were designated as UA (UnAssigned). Isolates of clonal complex CC60 were the most frequent and all belonged to serogroup E (n=9; 16.7%), followed by isolates of CC1157 (n=8; 14.8%) that were mainly of serogroup X (n=7) with one E isolate. Notably, 3 isolates of CC181 (serogroup X) were also detected. Only four non-groupable isolates (7.4%) belonged to one of the hyperinvasive clonal complexes (2 from CC32 and 2 from CC269).

3.2. Complement Activation on Meningococcal Bacterial Surface

IMD cases that are due to unusual groups appear to be associated with complement deficiencies (hereditary or acquired deficiencies). Six of the 59 cases (10.2%) reported here were associated with complement deficiencies. One case was associated with late terminal complement pathway deficiency (TPD). The Five other cases were associated with acquired deficiency due to treatment for Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) using monoclonal antibodies against the C5 complement component (anti-C5 mAb). Of the 6 corresponding isolates, 5 belonged to group E and one isolate was non-capsulated.

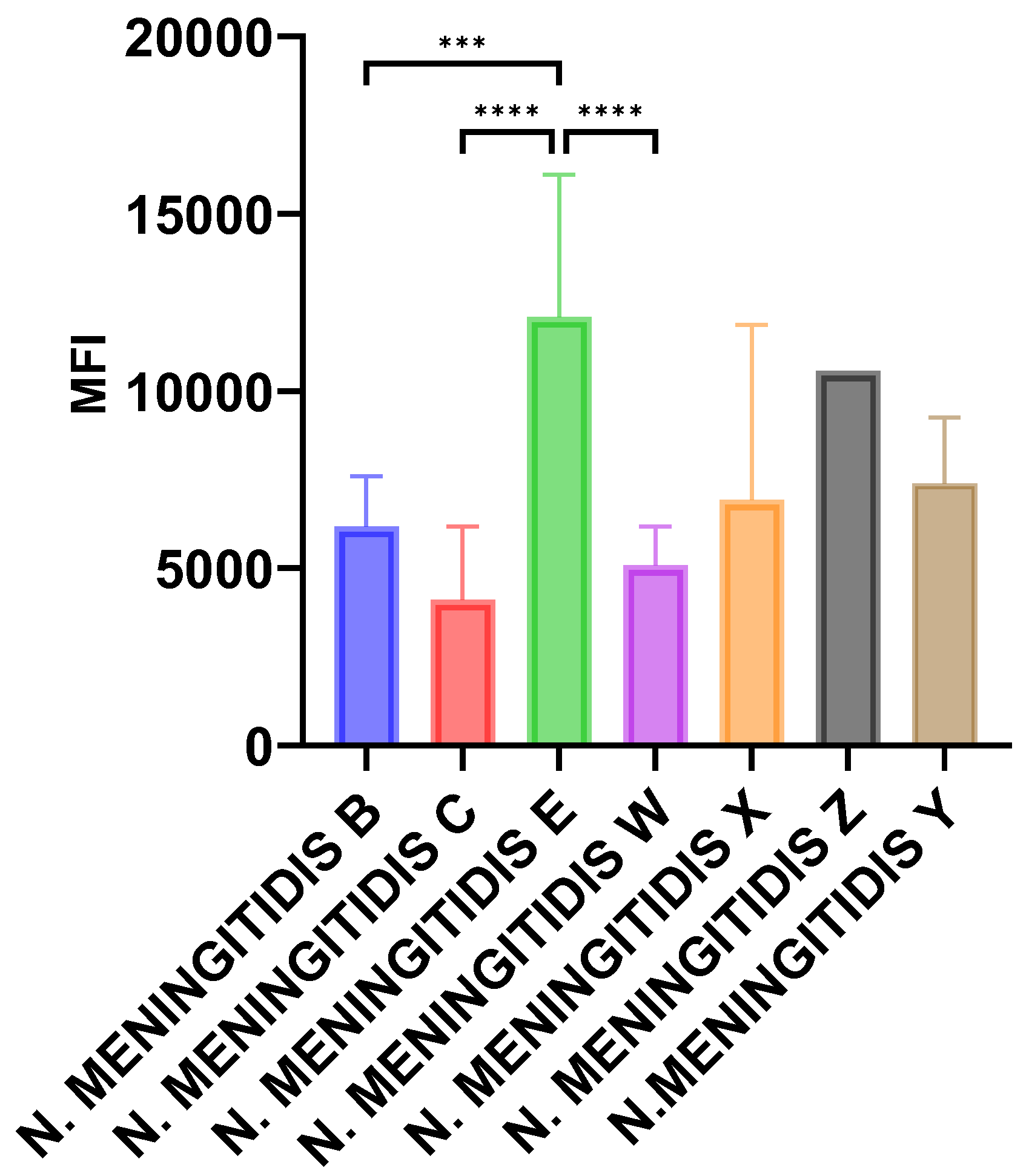

We, therefore, tested the deposition of the terminal complement pathway components on bacterial surfaces using flow cytometry and monoclonal antibody directed against the membrane attack complex C5b-C9 (MAC) as described in the Methods section.

Isolates of serogroups E (n=7), X (n=6) and Z (n=1) from the current study were tested and we added invasive isolates of serogroups B (n=16), C (n=8), W(n=14) and Y (n=8) belonging to hyperinvasive isolates. Data were expressed as mean of fluorescence index for isolates of the same serogroup. Significantly higher levels of MAC deposition were observed for isolates of serogroup E when compared with serogroups, B, C, and W (p<0.001). Serogroup X isolates also showed higher levels compared with serogroups B, C, and W but did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 1).

3.3. Coverage of Serogroup E Isolates by Vaccines Against Meningococci B

Data on vaccine coverage by both vaccines available against meningococci of serogroup B (4CMenB and the Bivalent fHbp) were extracted from WGS data of the 38 cases for which a cultured isolate were available. MenDeVar-based prediction showed that 7/38 isolates (18.4%) were predicted to be covered by the 4CMenB, and 20/38 isolates (52.6%) were predicted to be covered by the Bivalent fHbp vaccine (

Table 2) [

7]. Serogroup E isolates were predicted to be covered by the serogroup B bivalent fHBP vaccine but were unpredictable for their coverage by the 4CMenB vaccine [

7]. We therefore used SBA approach and compared SBA titers in sera from subjects vaccinated by the 4CMenB vaccine before and after vaccination. SBA titers in sera before vaccination were below the threshold of 4 that correlates with protection but increased to 8 and 16 in sera after vaccination (above the threshold of 4 that correlates with protection) for the three serogroup E tested isolates. The results suggest that the 4CMenB vaccine covered these isolates.

4. Discussion

Our work highlights the unusual meningococcal serogroups that although of low prevalence, require awareness as they may reveal or reflect special patient backgrounds such as unusual presentation of IMD or association with complement deficiencies. Moreover, some isolates may be linked to travel/immigration such as the serogroup X isolates of CC181 that were also reported in meningitis cases due to serogroup X in sub-Saharan Africa and refugee camps in Europe [

8]. IMD cases due to these unusual serogroups were mainly among children, adolescents, and young adults as reflected by the median age of 21.5, which is similar to that of cases due to serogroup B. Cases due to serogroups W and Y are usually reported in adults or older adults [

2] while IMD cases due to serogroup C are shifting to adults after the implementation of mandatory vaccination against meningococci of serogroup C in France since 2018 [

9].

These unusual isolates usually do not belong to the major hyperinvasive genetic lineages. This observation is at odds with the percentage of invasive isolates belonging to the hyperinvasive clonal complexes (CC11, CC32, CC41/44, and CC269) in France, which was 66.8% before the COVID-19 pandemic [

9]. We have previously reported that serogroup Y and non-groupable isolates were significantly more prevalent among TPD patients [

3]. Serogroup E isolates were also associated with both acquired and hereditary complement deficiencies. Our data showed that serogroup E isolates exhibited the highest level of MAC deposition at the bacterial surface which may prevent the invasion by these isolates in immunocompetent subjects. However, when MAC is missing, the invasiveness of these bacteria is enhanced. These data agree with a higher susceptibility to IMD due to serogroup E isolates when MAC is missing as in patients with TPD or those treated with anti-C5 mAb.

Vaccines targeting meningococci B are composed of proteins and may be effective against isolates of other serogroups when isolates match with vaccine components [

5]. Our data further provide evidence that isolates of unusual serogroups can also be covered by vaccines that were licensed against isolates of serogroup B. This result supports the recommendation for a wide anti-meningococcal vaccination including ACWY and B vaccines among patients with complement deficiencies. The burden of cases due to isolates of unusual serogroups is expected to increase in proportion, and their number is also expected to rise upon the increasing indication of anti-complement drugs [

10].

5. Conclusions

IMD cases due to the usual serogroups in Europe (B, C, Y, and W) are expected to decrease upon the implementation of vaccination strategies against these serogroups. Therefore, enhanced surveillance of cases due to other serogroups and analysis of the corresponding isolates is warranted.

Author Contributions

MKT, AED and ST conceptualized the work, extracted and analyzed the data. GF performed the experimental work on complement activation. AT, OD and EH performed WGS and SBA . MKT wrote the first draft and all Authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Institut Pasteur, grant number E024519 and Santé Publique France grant number E02498 your future funding.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the staff of the National Reference Centre for meningococci and Haemophilus influenzae for technical assistance. This publication made use of the

Neisseria MultiLocus Sequence Typing website (

https://pubmlst.org/) developed by Keith Jolley and sited at the University of Oxford (K.A. Jolley, M.C. Maiden. BMC Bioinform, 11 (2010), p. 595). The development of this site has been funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Conflicts of Interest

MKT performs contract work for the Institut Pasteur funded by GSK, Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur. MKT and AED have a NZ630133A Patent with GSK "Vaccines for serogroup X meningococcus" issued. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Caugant, D.A.; Maiden, M.C. Meningococcal carriage and disease--population biology and evolution. Vaccine 2009, 27 (Suppl 2), B64–B70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo, R.; Bai, X.; Borrow, R.; Caugant, D.A.; Carlos, J.; Ceyhan, M.; Christensen, H.; Climent, Y.; De Wals, P.; Dinleyici, E.C.; et al. The Global Meningococcal Initiative meeting on prevention of meningococcal disease worldwide: Epidemiology, surveillance, hypervirulent strains, antibiotic resistance and high-risk populations. Expert Rev Vaccines 2019, 18, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosain, J.; Hong, E.; Fieschi, C.; Martins, P.V.; El Sissy, C.; Deghmane, A.E.; Ouachee, M.; Thomas, C.; Launay, D.; de Pontual, L.; et al. Strains Responsible for Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Patients With Terminal Complement Pathway Deficiencies. J Infect Dis 2017, 215, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, L.A.; Topaz, N.; Wang, X.; Hariri, S.; Fox, L.; MacNeil, J.R. High Risk for Invasive Meningococcal Disease Among Patients Receiving Eculizumab (Soliris) Despite Receipt of Meningococcal Vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017, 66, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biolchi, A.; Tomei, S.; Brunelli, B.; Giuliani, M.; Bambini, S.; Borrow, R.; Claus, H.; Gorla, M.C.O.; Hong, E.; Lemos, A.P.S.; et al. 4CMenB Immunization Induces Serum Bactericidal Antibodies Against Non-Serogroup B Meningococcal Strains in Adolescents. Infect Dis Ther 2021, 10, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Terrade, A.; Taha, M.K. Immunogenicity and safety among laboratory workers vaccinated with Bexsero(R) vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017, 13, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.M.C.; Jolley, K.A.; Smith, A.; Cameron, J.C.; Feavers, I.M.; Maiden, M.C.J. Meningococcal Deduced Vaccine Antigen Reactivity (MenDeVAR) Index: A Rapid and Accessible Tool That Exploits Genomic Data in Public Health and Clinical Microbiology Applications. J Clin Microbiol 2020, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanelli, P.; Neri, A.; Vacca, P.; Picicco, D.; Daprai, L.; Mainardi, G.; Rossolini, G.M.; Bartoloni, A.; Anselmo, A.; Ciammaruconi, A.; et al. Meningococci of Serogroup X Clonal Complex 181 in Refugee Camps, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 2017, 23, 870–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, S.; Hong, E.; Denizon, M.; Falguieres, M.; Terrade, A.; Deghmane, A.E.; Taha, M.K. The rapid rebound of invasive meningococcal disease in France at the end of 2022. J Infect Public Health 2023, 16, 1954–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patriquin, C.J.; Kuo, K.H.M. Eculizumab and Beyond: The Past, Present, and Future of Complement Therapeutics. Transfusion medicine reviews 2019, 33, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).