2. Results and Discussion

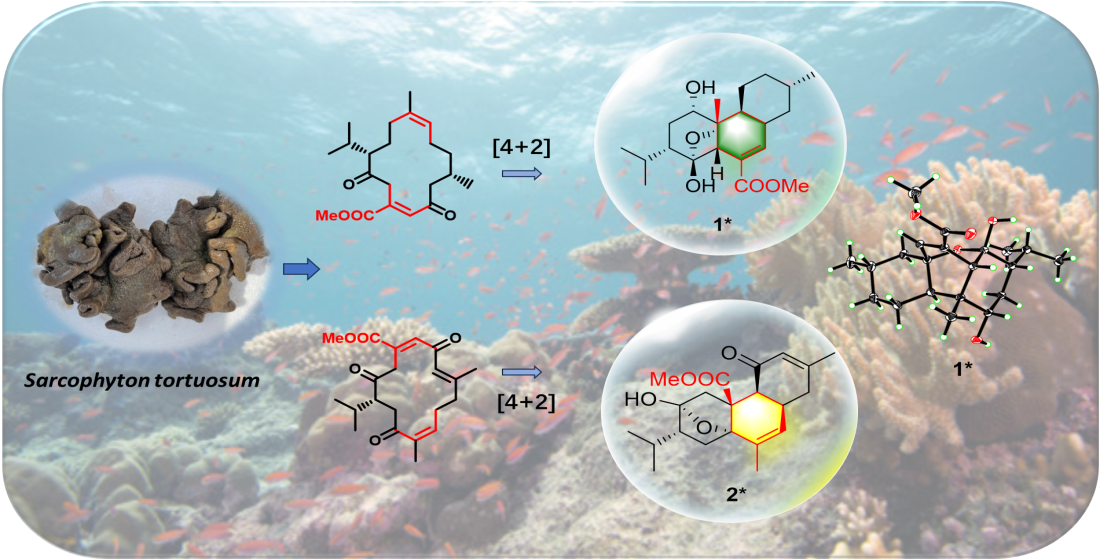

Freshly collected specimens of

S. tortuosum were frozen to –20°C before exhaustively extracted with acetone. The Et

2O-soluble portion of the acetone extract of the title animal was subjected to repeated chromatography, including silica gel, Sephadex LH-20, and RP-HPLC to yield four compounds (

1–

4). The known compounds

3 and

4 were readily identified as 4-oxochatancin (

3),[

15] and (+)-chatancin (

4),[

16] respectively, by direct comparison of their NMR spectroscopic data and specific rotation value with those reported in the literatures.

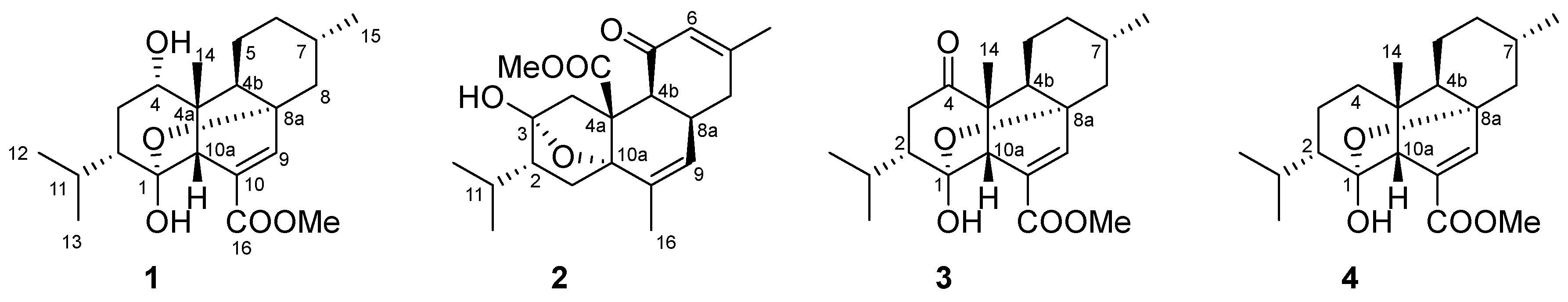

Compound 1 was isolated as a colorless crystal. Its molecular formula of C21H32O5 was established by the quasi-molecular ion peak at m/z 387.2129 ([M+Na]+, calc. 387.2147 for C21H32O5Na) in the HR-ESIMS spectrum, indicating six degrees of unsaturation. The IR spectrum displayed strong absorption at 3460 cm−1 and 1712 cm−1, suggested the presence of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups. The 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and DEPT spectra of 1 suggested the presence of one trisubstituted double bond [δH 7.27 (1H, s, H-9), δC 145.11 (CH, C-9) and δC 134.82 (qC, C-10)], one carbonyl carbon atom [δC 165.41 (qC, C-16)], and one oxymethine [δH 3.53 (1H, m, H-4), δC 77.0 (CH, C-4)]. Consequently, the remaining four degrees of unsaturation led to the fact that compound 1 was a tetracyclic structure.

Detailed comparison revealed that the NMR data (

Table 1) of compound

1 were almost identical to those of co-occurred compounds

3 and

4, which had been previously isolated from the tropical marine slug

Phyllodesmium longicirrum that prey on soft corals of the genus

Sarcophyton. The only difference between

1 and

3 was that the carbonyl group at the C-4 position in

3 was replaced by a hydroxyl group in

1, which as evidenced by the 2 mass unit difference in their ESIMS data. Thus, the planar structure of

1 was determined as shown in

Figure 1.

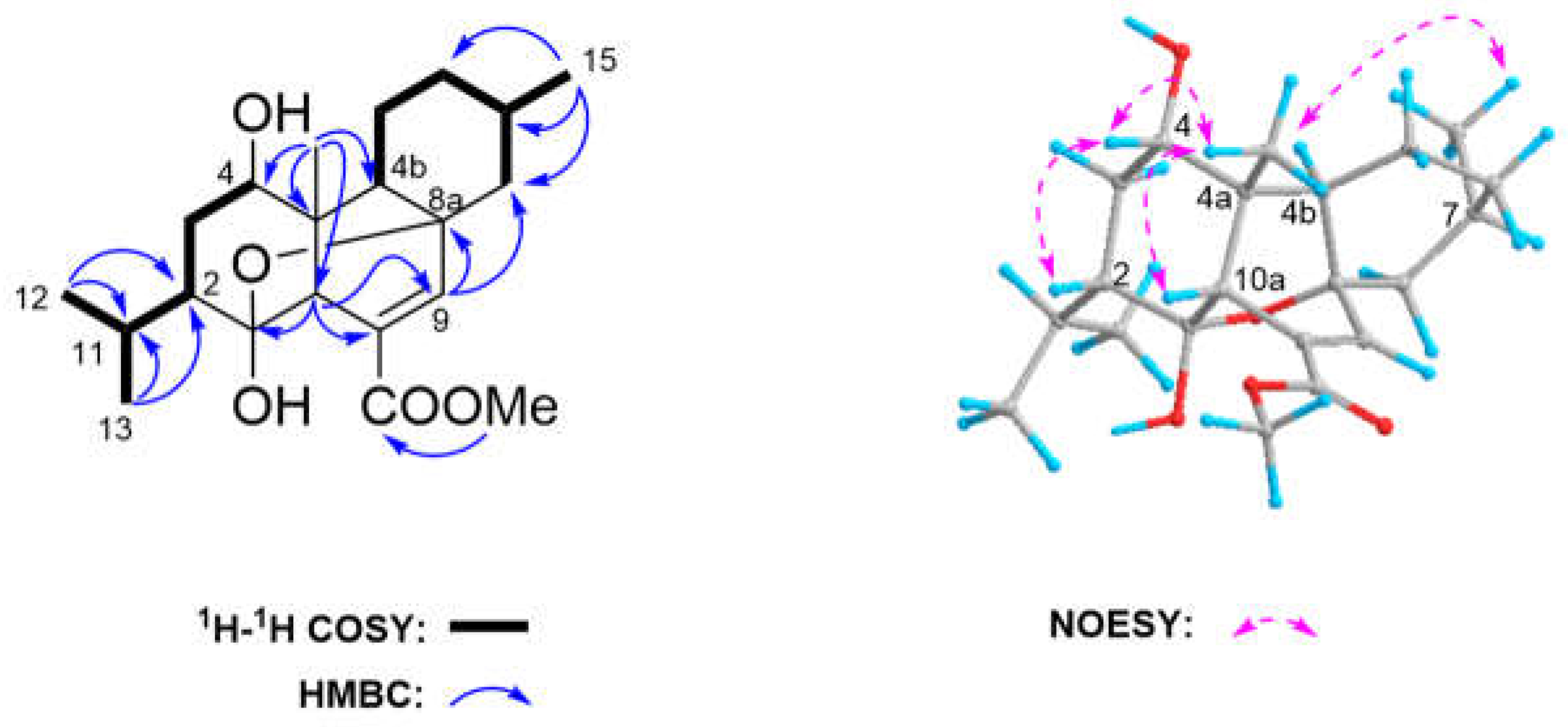

In the NOESY spectrum, there was a clear correlation between H-4 (

δH 3.53, m), CH

3-14 (

δH 0.85, s), H-2 (

δH 1.56) and H-10a (

δH 2.79, d,

J=1.73), indicating that H-2, H-4, CH

3-14 and H-10a are on the same side of the molecule, and randomly assigned as

b-orientation (

Figure 2). Subsequently, the interactions of H-4b (

δH 1.60)/CH

3-15(

δH 1.00, d,

J=6.3), revealed that these protons and/or proton-bearing groups were positioned at the other side of the molecule, thus

a-orientation. In the light of above observation, the relative configuration of C-2, C-4, C-4a, C-4b, C-7, and C-10a in

1 was assigned to be 2

S*, 4

S*, 4a

R*, 4b

R*, 7

S, and 10a

R*, respectively. In addition, the relative stereochemistry of C-1 and C-8a in

1 was tentatively determined to be the same 1

R* and 8a

R* as that of

3 on basis of their highly similar

13C NMR data.

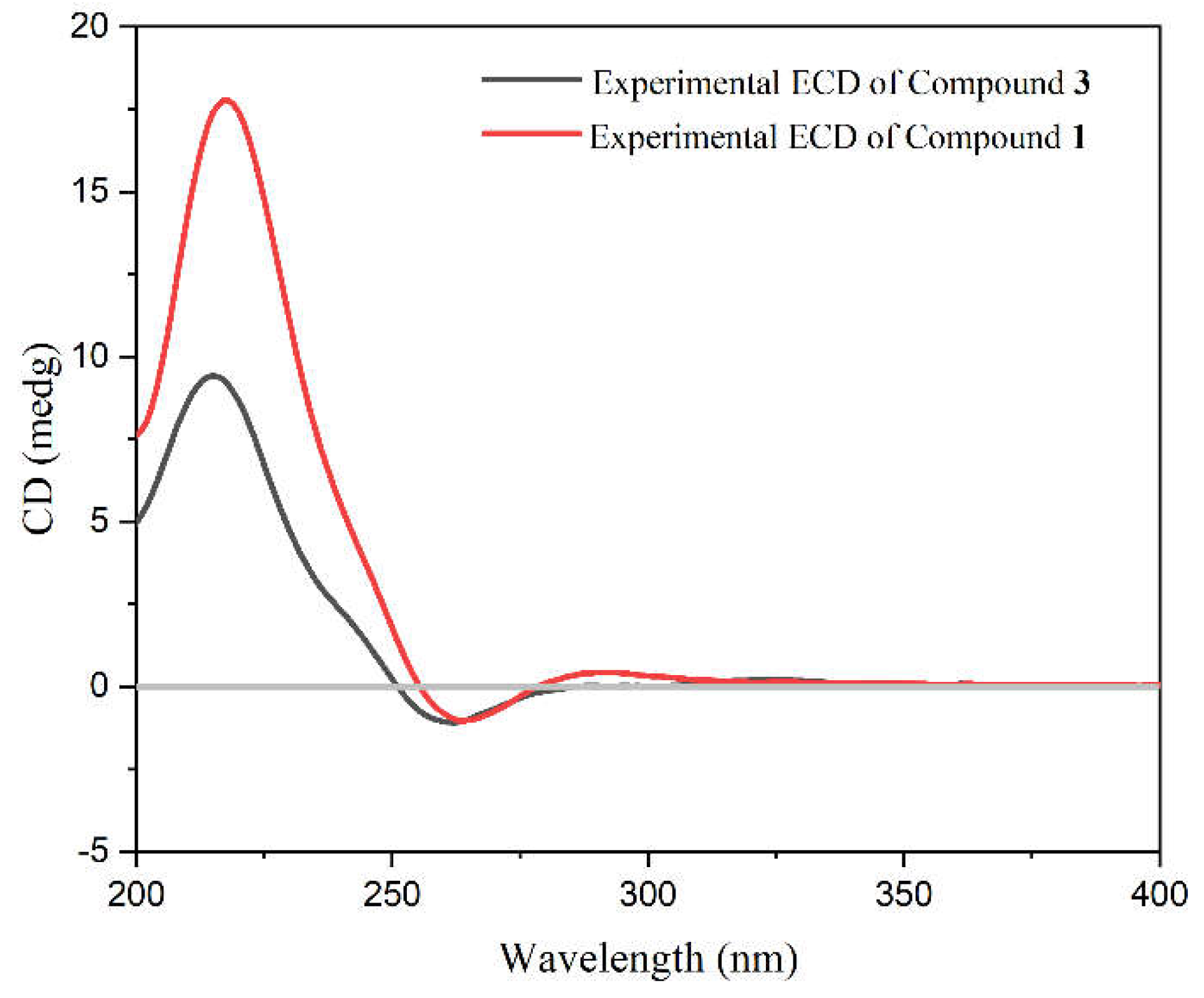

The absolute configuration of

1 was determined by comparing its ECD spectra with that of

3. As shown in

Figure 3, the cotton effects in the ECD spectra of the two compounds are consistent with each other. Therefore, the absolute configuration of

1 was ultimately determined as 1

R, 2

S, 4

S, 4a

R, 4b

R, 7

S, 8a

R, 10a

R.

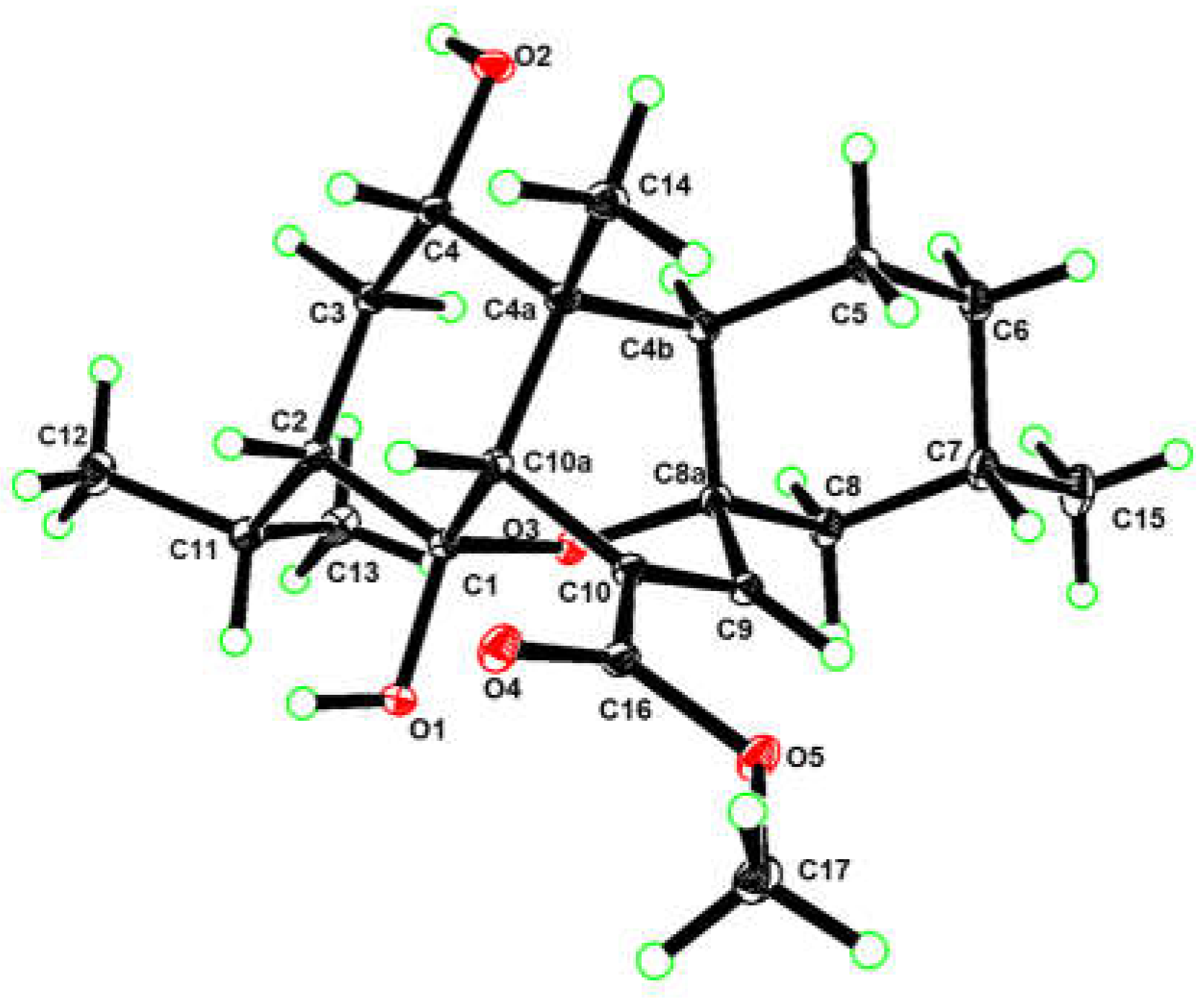

In order to unambiguously confirm the structure and absolute configuration of

1, the suitable single crystals of

1 in MeOH were obtained. The X-ray crystallographic analysis using Cu K

α radiation (λ=1.54178 Å) firmly disclosed the planar structure of

1 and determined its absolute configuration as 1

R, 2

S, 4

S, 4a

R, 4b

R, 7

S, 8a

R, 10a

R with the Flack parameter of 0.08(7) (

Figure 4, CCDC 2384793). Consequently, the structure of

1 was elucidated as depicted in

Figure 1 and named as 4

a-hydroxy-chatancin.

Sarcotoroid (2) was isolated as colorless oil, which possessed the molecular formula of C21H28O5 as assigned by HR-ESIMS protonated molecular ion peak at m/z 361.2004 ([M+H]+, calc. for C21H29O5, 361.2010), requiring eight degrees of unsaturation. The IR spectrum of 2 showed absorption bonds at 3300 cm–1 and 1727 cm–1 suggested the presence of hydroxy and easter carbonyl functionalities. The 1D and 2D NMR spectra of 2 revealed the presence of two trisubstituted double bonds [δH 5.86 (1H, s, H-6), δC 161.51 (qC, C-7), and δC 127.46 (CH, C-6); δH 5.89 (1H, s, H-9), δC 134.19 (qC, C-10), and δC 135.25 (CH, C-9)], one carbonyl group [δC 197.91 (qC, C-5)], one methyl ester group [δH 3.71 (3H, s, H-17) and δC 175.33 (qC, C-14)], and one hemiketal group [δC 106.36 (qC, C-3)]. The above functionalities accounted for four degrees of unsaturation, suggesting that compound 2 must possess a tetracyclic ring system accounting for the remaining four degrees of unsaturation.

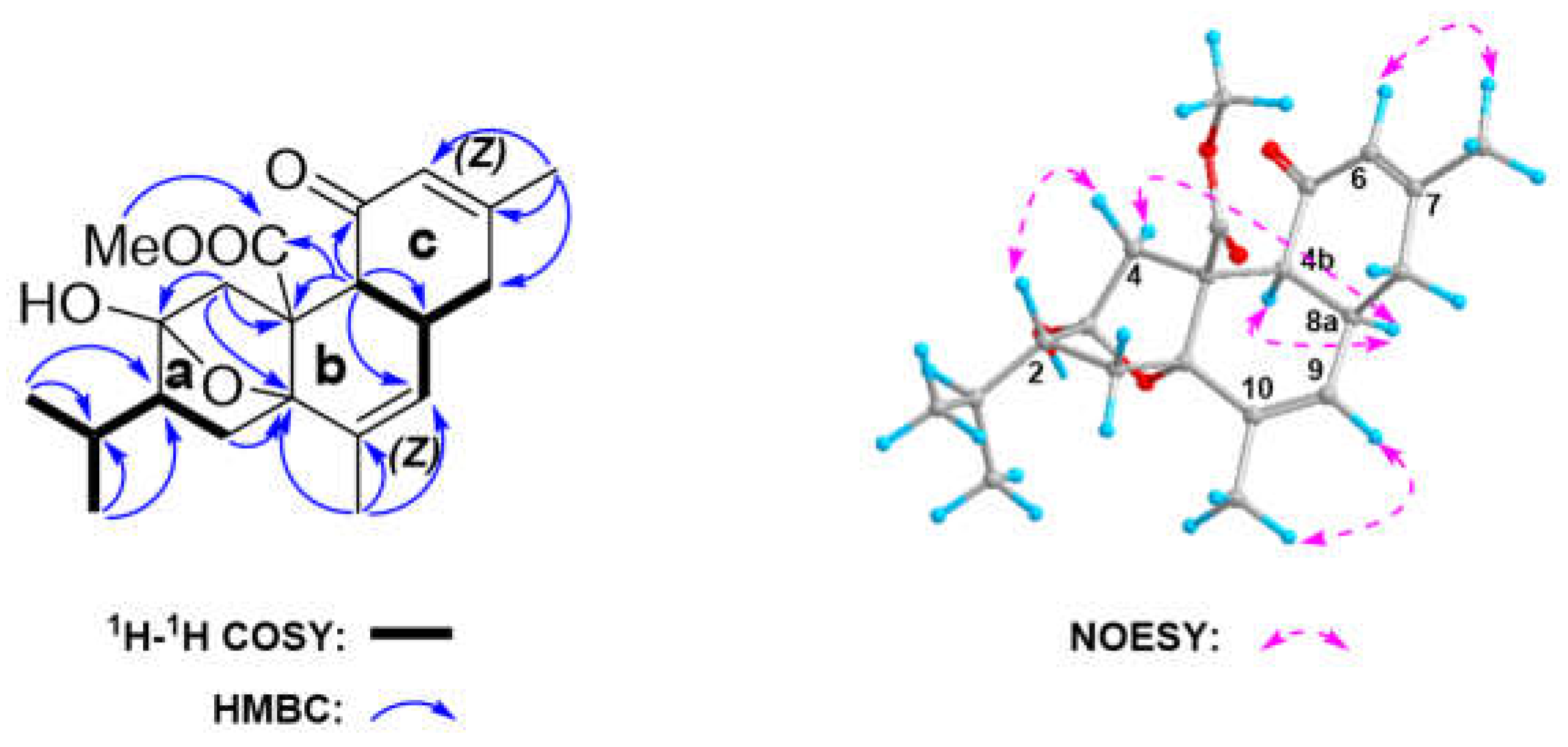

Detailed analysis of

1H‒

1H COSY spectrum of

2 revealed two sequential fragments (

Figure 5) by the clear correlations of H-4b [

δH 2.91 (d,

J = 13.0)]/H-8a [

δH 3.02, m]/H-8 [

δH 2.25, m]/H-9 [

δH 5.89, m], and CH

3-12 [

δH 0.88 (d,

J = 6.7)]/CH

3-13[

δH 0.90 (d,

J = 6.7)]/H-11 [

δH 1.98, m]/H-2 [

δH 2.18, m]/H

2-1 [

δH 1.82 (dd,

J = 13.1, 6.5),

δH 1.46 (dd,

J = 13.1, 8.3)]. The key HMBC correlations from H-4 to C-3, C-4a, and C-10a, from H-1 to C-2, C-3, C-10a, and C-4a, indicated the present of ring (

a) in the structure. The second ring (

b) was confirmed by HMBC correlations from H-4b to C-4a, C-8a, and C-9; as well as from CH

3-16 to C-9, C-10, and C-10a. The diagnostic HMBC correlation from H-4b to C-8a, C-8, and C-5 and from CH

3 to C-6, C-7, and C-8 agreed with the presence of the third ring (

c). Considering the downfield shift of the two quaternary carbons C-3 (

δC 106.36) and C-10a (

δC 81.47), the remaining one degree of unsaturation must be given by the formation of an oxygen bridge between C-3 and C-10a. Finally, the planar structure of

2 was determined as shown in

Figure 5.

The observed NOESY correlations between H-6 (

δH 5.86)/CH

3-15 (

δH 1.96) and H-9 (

δH 5.89)/CH

3-16 (

δH 1.86) demonstrated the

Z geometries of the double bonds at Δ

6,7 and Δ

9,10. The NOE correlations of H-4b/H-8a suggested that H-4b and H-8a were in same orientation. The NOE correlations of H-8a/H

a-4 and H

b-4/H-2 indicated that H-2 and H-8a were in opposite orientation. Thus, the relative configuration of C-4b, C-8a, and C-2 was assigned as 2

R*, 4b

S*, and 8a

S*. Due to the advantageous conformation of the five membered ring in the envelope form, the relative configuration of C-3, C-10a was determined to be 3

R* and 10a

S*. However, the relative configuration of C-4a remains a challenge task due to the absence of related NOESY correlations. Therefore, the quantum mechanical-nuclear magnetic resonance (QM-NMR) method, which has been widely used to define the relative configuration of multi stereogenic centers of natural products,[

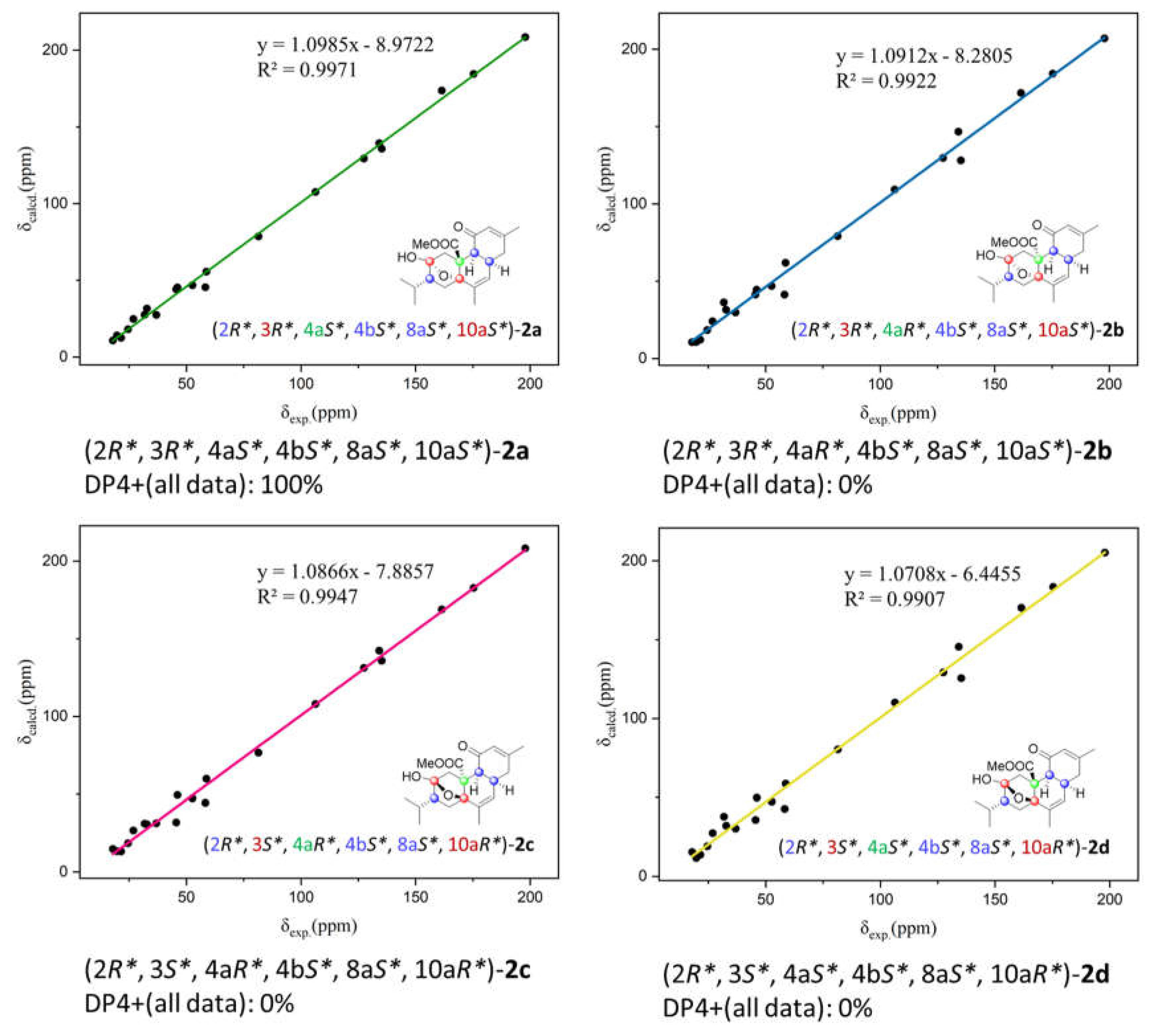

17] was applied. Four possible candidate structures, namely

2a (2

R*, 3

R*, 4a

S*, 4b

S*, 8a

S*, 10a

S*),

2b (2

R*, 3

R*, 4a

R*, 4b

S*, 8a

S*, 10a

S*),

2c (2

R*, 3

S*, 4a

R*, 4b

S*, 8a

S*, 10a

R*), and

2d (2

R*, 3

S*, 4a

S*, 4b

S*, 8a

S*, 10a

R*) were calculated for their theoretical NMR data. Following the DP4+ protocol, geometrical optimization at the DFT level was undertaken by using the B3LYP functional with the 6–311G(d,p) basis set.[

18] Afterward, the NMR calculation was conducted at the mPW1PW91/6-31G* level, and the experimental NMR data of

2 gave the best match to that of

2a with over 99% probability. (

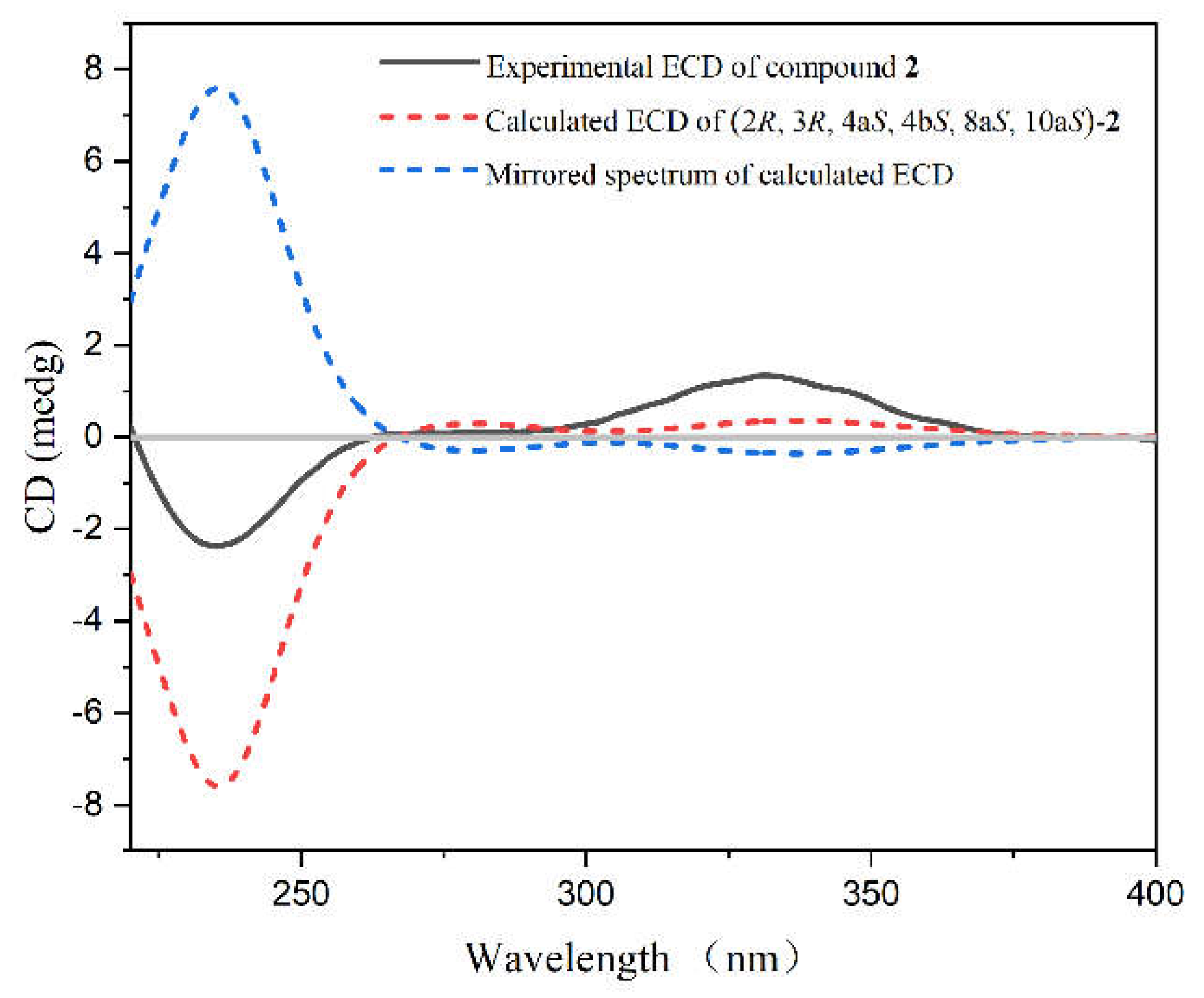

Figure 6). Moreover, the TDDFT-ECD method was also performed to determine the absolute configuration of

2.[

19,

20] As shown in

Figure 7, the calculated ECD curve of (2

R, 3

R, 4a

S, 4b

S, 8a

S, 10a

S)-

2 fits good agreement with the experimental ECD curve of

2. Finally, the absolute configuration of

2 was assigned as 2

R, 3

R, 4a

S, 4b

S, 8a

S, 10a

S as shown in

Figure 1.

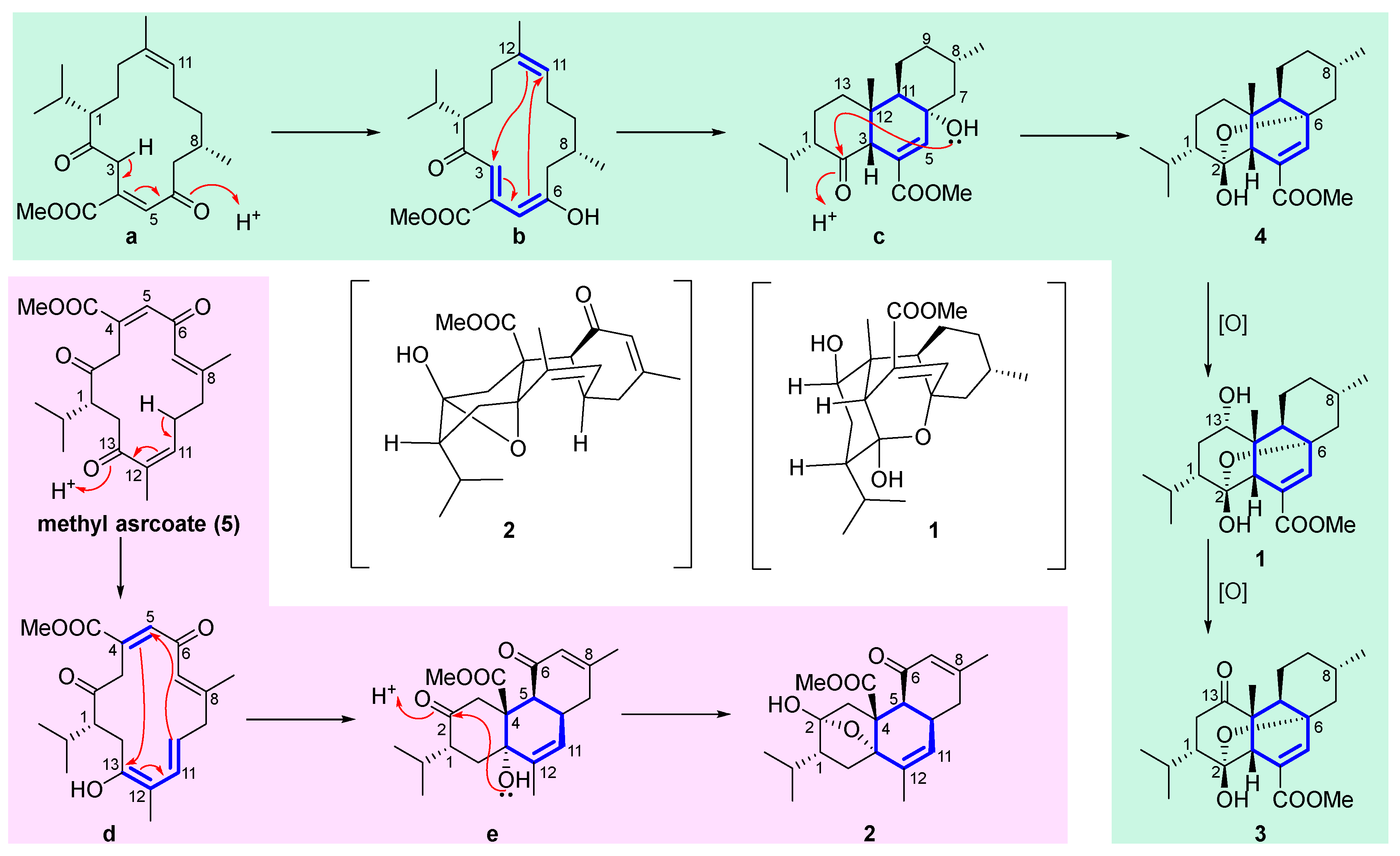

It is worth pointing out that the structural similarities between compounds

1–

4, and their co-occurrence in the same sample suggested that they may originate from the same biogenetic pathway. A plausible biosynthetic pathway for structural correlations among the related diterpenoids

1–

4 was proposed. As shown in

Scheme 1, compounds

1,

3 and

4 herein probably have the same precursor macrocyclic diketone

a. Firstly, the C-6 of

a undergoes enol interconversion, resulting in the formation of conjugated double bonds at Δ

3,4 and Δ

5,6 in

b. Subsequently, these conjugated double bonds participate in a transannular Diels-Alder cycloaddition with the double bond at Δ

11,12, leading to the formation of the core structure featuring an uncommon 6/6/6-tricyclic ring system. Finally, the lone pair electrons of the oxygen atom in 6-OH attacked the C-2 carbon atom, resulting in the formation of

4 with an epoxy bridge between C-6 and C-2. Following by two steps of oxidation, compounds

1 and

3 are ultimately obtained. Similarity, the precursor methyl sarcoate (

5)[

21] undergoes enol interconversion yielded

d, the conjugated double bonds at Δ

10,11 and Δ

12,13 of

d undergo a transannular Diels-Alder cycloaddition with the double bonds at Δ

4,5 to generate

e, followed by the nucleophilic attack of hydroxyl group 13-OH on C-2 formed

2.

In bioassay, all the isolated compounds were tested for their antibacterial effects. Streptococcus parauberis is the primary pathogen responsible for fish-borne streptococcal disease, which is widely distributed and highly pathogenic, causing significant economic losses in fish aquaculture worldwide. S. parauberis can infect a diverse range of fish, including both freshwater and farmed or wild species, exhibiting clinical symptoms similar to septicemia. However, these strains have gradually developed drug resistance, including multidrug resistance. The S. parauberis SPOF3K strain is a drug-resistant isolate from aquaculture that exhibits significant resistance to tetracycline and oxytetracycline, with the MIC of over 24 μg/mL and 12.42 μg/mL, respectively. Notably, compound 1 exhibited good antibacterial activity against the S. parauberis KSP28 and oxytetracycline-resistant S. parauberis SPOF3K, with an MIC value of 9.10 μg/mL, which is superior to the antibacterial effect of oxytetracycline (MIC = 12.42 μg/mL).

Photobacterium damselae (formerly

Vibrio damsela) is a halophilic bacterium associated with marine environments, known to cause skin ulcers in damselfish. It is a primary pathogen responsible for ulcers and hemorrhagic septicemia in various marine species, including dolphins, sharks, and shrimp, as well as both wild and cultivated fish. Additionally, this pathogen can lead to fatal infections in humans.[

22] Compound

1 showed significant antibacterial activities against the

P. damselae FP2244 with the MIC value of 18.21 μg/mL.

Besides, the isolated compounds were tested for antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter hormaechei, Aeromonas sabnonicida, Photobacterium halotolerans, Lactococcus garvieae FP MP5245, and several strains of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (G1, G4, G7, and G13), as well as Streptococcus agalactiae, Edwardsiella piscicida TH1, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Vibrio alginolyticus. However, these results were negative at the concentration of 100 μM.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activities of compound 1 and antibiotics.a.

Table 2.

Antibacterial activities of compound 1 and antibiotics.a.

| Compounds |

MIC (μg/mL) |

| S. parauberis |

S. parauberis SPOF3K |

P. damselae FP2244 |

| 1 |

9.10 |

9.10 |

18.21 |

| Tetracycline |

3.01 |

>24.00 |

0.02 |

| Oxytetracycline |

1.55 |

12.42 |

0.02 |

| Levofloxacin |

1.24 |

1.24 |

0.02 |

| Ampicillin |

4.64 |

0.58 |

0.02 |

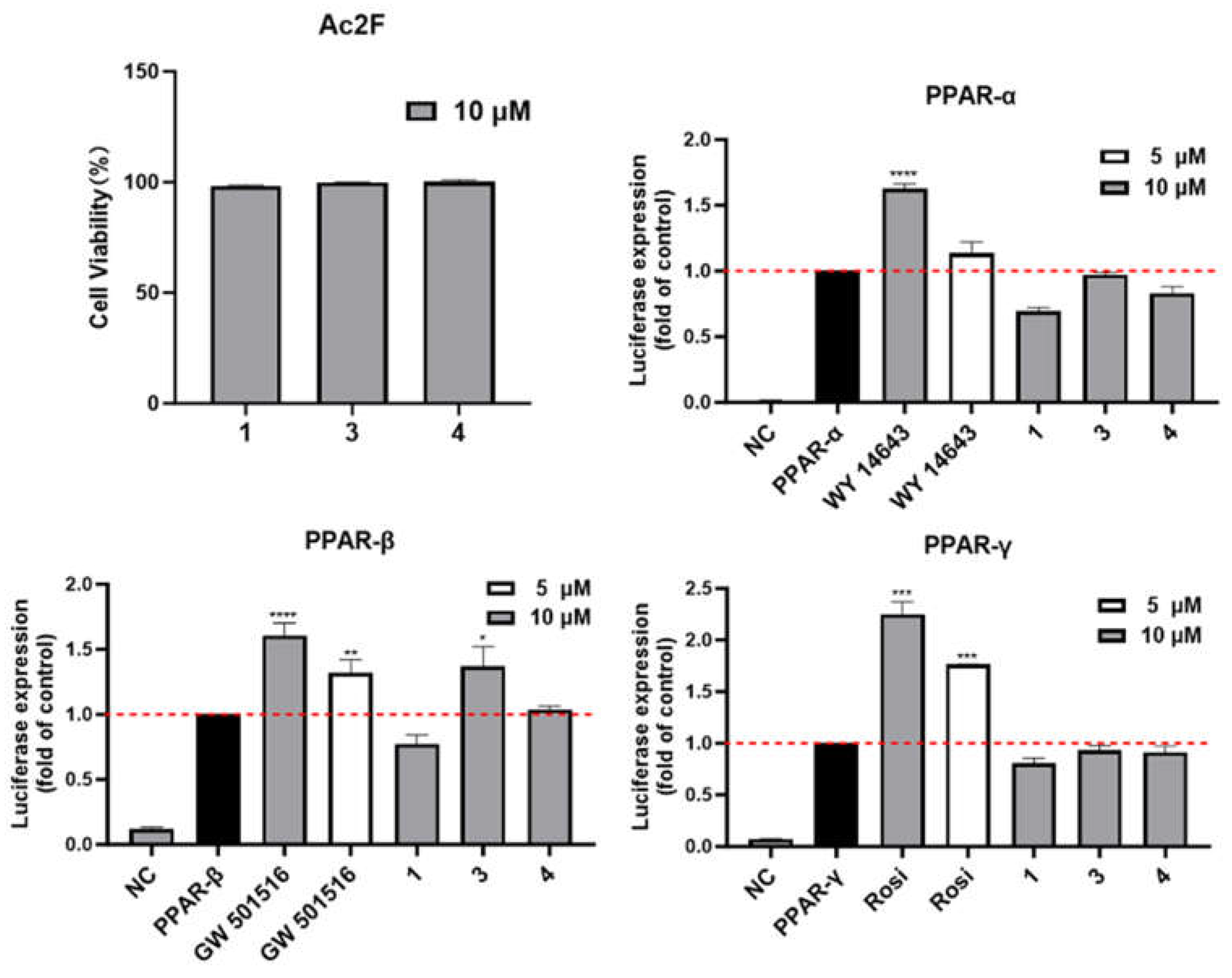

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) include PPAR-α, PPAR-β, and PPAR-γ isotypes, which are transcription factors that regulate gene expression upon ligand activation. PPAR-α enhances cellular fatty acid uptake, esterification, and trafficking, while also regulating genes involved in lipoprotein metabolism. PPAR-β stimulates lipid and glucose utilization by increasing mitochondrial function and fatty acid desaturation pathways. While PPAR-γ promotes fatty acid uptake, triglyceride formation, and storage in lipid droplets, which enhances insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism.[

23] The compounds

1,

3 and

4 were evaluated for PPAR transcriptional activity using luciferase assay (

Figure 8). As shown in

Figure 8A, these compounds were first evaluated for their cytotoxicity against Ac2F cells. Compounds

1,

3 and

4 demonstrated no cytotoxic effects on Ac2F cells at a concentration of 10 μM after 24 h treatment. Notably, compound

3 exhibited significant and selective PPAR-β agonist activity at the concentration of 10 μM, comparable to that of the positive control GW501516 at 5 μM.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Melting points were measured on an X-4 digital micro-melting point apparatus. The X-ray measurement was made on a Bruker D8 Venture X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (Bruker Biospin AG, Fällanden, Germany). Optical rotations were measured on a Perkinelmer 241 MC polarimeter. IR spectrum was recorded on a Nicolet iS50 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, WI, USA). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker DRX-600 spectrometer (Bruker Biospin AG, Fällanden, Germany). Chemical shifts are reported with the residual CDCl3 (δH 7.26 ppm) as the internal standard for 1H-NMR spectrometry and CDCl3 (δC 77.26 ppm) for 13C-NMR spectrometry. The HR-ESI-MS spectra were recorded on a ZenoTOF7600 mass spectrometer (SCIEX). Commercial silica gel (Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China, 200–300, and 300–400 mesh) was used for column chromatography, and Sephadex LH-20 gel (Amersham Biosciences) were used for column chromatography (CC), and precoated-silica-gel-plates (G60 F-254, Yan Tai Zi Fu Chemical Group Co., Yantai, China) were used for analytical TLC. Spots were detected on TLC under UV light or by heating after spraying with anisaldehyde H2SO4 reagent. Reversed phase (RP) HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1260 series liquid chromatograph equipped with a DAD G1315D detector at 210 nm (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). An Agilent semi-preparative XDB-C18 column (5 μm, 250×9.4 mm) was employed for the purification. All solvents used for CC and HPLC were of analytical grade (Shanghai Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and chromatographic grade (Dikma Technologies Inc., Beijing, China), respectively.

3.2. Animal Materials

The soft coral S. tortuosum was collected from Ximao Island, Hainan Province, China, in 2023 at a depth of –20 meters, and identified by Professor Xiu-Bao Li from Hainan University. A voucher specimen (No. 23-YT-20) is available for inspection at the Shandong Laboratory of Yantai Drug Discovery.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

The frozen animals (800.4 g, dry weight after extraction) were cut into pieces and extracted exhaustively with acetone at room temperature (4×2L). The organic extract was evaporated to give a brown residue, which was then partitioned between diethyl ether (Et2O) and H2O. The Et2O solution was concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain a dark brown residue (58.0 g), which was classified by silica gel column chromatography (200-300 mesh) and eluted with a step gradient [0–100% Et2O in petroleum ether (PE) solution to obtain six fractions (A–G). Fraction D (2.1 g) was subjected to chromatography on a Sephadex LH-20 column using a petroleum ether (PE)/CH2Cl2/MeOH (2:1:1) elution system, yielding subfractions DA to DC. Purification of the DB subfraction was performed using Sephadex LH-20 (CH2Cl2), followed by silica gel column chromatography with a PE/Et2O (20:1) elution, yielding four subfractions (DBAA–DBAD). Further purification of DBAB by RP-HPLC [CH3CN/H2O (85:25), 3.0 mL/min] led to the isolation of compound 4 (4 mg, tR = 29 min). Fraction F (2.3 g) was purified by chromatography on Sephadex LH-20, as described above, yielding subfractions FBA–FBE and FCA–FCH. Subfraction FBA was subjected to silica gel column chromatography, eluting with PE/Et2O (15:1), to give five subfractions (FBAA–FBAE). Further purification of subfraction FBAB by semi-preparative RP-HPLC (CH3CN/H2O, 70:30) yielded compound 3 (2 mg, tR = 23.5 min). Further purification of subfraction FCD by semi-preparative RP-HPLC (CH3CN/H2O, 52:48) yielded compound 1 (1.2 mg, tR =11 min), and purification of subfraction FCF by semi-preparative RP-HPLC (CH3CN/H2O, 45:55) yielded compound 2 (1.7 mg, tR = 16 min).

3.4. Spectroscopic Data of Compounds

4

a-hydroxy-chatancin (

1): Colorless crystal, (m. p. 122-124°C),

–2 (c 0.10, MeOH); IR (KBr): ν

max 3460, 2952, 2925, 2868, 1712, 1268 cm

−1; For

1H and

13C NMR spectroscopic data, see

Table 1; HR-ESI-MS

m/z 387.2129 ([M+Na]

+; calcd. for C

21H

32O

5Na, 387.2147).

Sarcotoroid (

2): Colorless oil,

–16 (c 0.10, MeOH); IR (KBr): ν

max 3300, 2952, 2918, 2850, 1727, 1627 cm

−1; For

1H and

13C NMR spectroscopic data, see

Table 1; HR-ESI-MS

m/z 361.2004 ([M+H]

+; calc. for C

21H

29O

5, 361.2010).

3.5. Calculation Section

For the QM-NMR calculations of compounds, conformational search was performed by using the torsional sampling (MCMM) approach and the OPLS_2005 force field applying an energy window of 21 kJ/mol (5.02 kcal/mol). Reoptimize the conformers of populations exceeding 1% Boltzman populations at the B3LYP/6-311G (d, p) level. Subsequently, nuclear magnetic resonance calculations were performed at the PCM/mPW1PW91/6-31G (d) level. The shielding constant of NMR was calculated using the GIAO method. Finally, calculate the average shielding constant for each stereoisomer Boltzmann distribution and correlate it with experimental data.

Regarding the TDDFT-ECD calculations of compounds, conformational search was carried out according to the general protocols previously described for QM-NMR calculation. Reoptimized the conformers above 1% Boltzmann population and used the IEFPCM solvent model for TDDFT-ECD calculations, using Gaussian 09 at the theoretical B3LYP/6-311G (d, p) level. Finally, the SpecDis 171 software was used to obtain the calculated ECD spectrum and visualize the results.

3.6. X-ray crystallographic Analysis for Compound 1

The crystallographic data were collected on a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54178 Å). The structures were solved with the ShelXT structure solution program using Intrinsic Phasing and refined with the ShelXL refinement package using Least Squares minimisation.

Compound 1: colorless crystals (m.p. 122-124°C), monoclinic, C21H34O6, Mr = 382.48, (including a water molecule) crystal size 0.2 × 0.15 × 0.04 mm3, space group C2, a = 19.2786(5) Å, b=11.3201(3)Å, c = 10.4695(3) Å, V = 2061.47(10) Å3, Z = 4, ρcalc = 1.232 g/cm3, F (000) = 832.0, Independent reflections: 3908 [Rint = 0.0656, Rsigma = 0.0341]. R1 = 0.0331, wR2 = 0.0810 reflections with I ≥ 2σ (I), R1 = 0.0331, wR2 = 0.0810 for all unique data, Flack parameter: 0.08(7). The crystals of 1 were recrystallized from MeOH. These above crystal data were deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) and assigned the accession number (CCDC 2384793).

3.7. Antibacterial Activity Bioassays

The bacterial strains S. parauberis KSP28, S. parauberis SPOF3K, P. damselae FP2244, A. sabnonicida, P. halotolerans and L. garvieae FP MP5245, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, E. cloacae, E. hormaechei, A. salmonicida, S. agalactiae, V. parahaemolyticus, and V. alginolyticus were provided by National Fisheries Research & Development Institute, Korea. The vancomycin-resistant strains E. faecium bacteria G1, G4, G7 and G13, and S. aureus were provided by Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. The E. piscicida TH1 was provided by Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences. were also used in antibacterial experiments.

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for compounds were determined using the 0.5 McFarland standard method. Mueller–Hinton II broth (cation-adjusted, BD 212322) was used for bacterial culture. Compounds were generally dissolved in DMSO to a concentration of 2 mM as stock solutions. All samples were diluted in culture broth to an initial concentration of 100 µM. Serial 1:1 dilutions were then performed using culture broth to achieve concentrations ranging from 100 µM to 0.24 µM. A total of 5 µL of each dilution was distributed into 96-well plates, along with sterile controls, growth controls (containing culture broth and DMSO without compounds), and positive controls (containing culture broth with antibiotics). All wells except sterile control well were inoculated with 95 µL of an exponential-phase bacterial suspension (approximately 105 CFU/well). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 12 h. MIC values were defined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibited bacterial growth. All MIC values were interpreted in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. The MIC in molar concentration was ultimately converted to mass concentration based on the molecular weight of each compound.

3.8. Cell Culture and Cell Viability

Rat liver Ac2F cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 2.5 mg/L amphotericin B, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and were maintained in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were seeded in 96-well culture plates, cultured for 12 h, and then treated with various concentrations of samples for 24 h. Cell viabilities were evaluated using water-soluble tetrazolium (CCK-8) reagent, which was added to each well (10 mL) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Absorbances were read using an microplate absorbance reader at a wavelength of 450 nm.

3.9. Luciferase Transactivation Assays

For luciferase assays, the 3×AOX-TK-luciferase reporter plasmid, containing 3 copies of the PPRE in the acyl CoA oxidase promoter was a gift from Dr. Chistopher K. Glass (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA). The pcDNA3 expression vector and full-length human PPAR-α, PPAR-β, or PPAR-γ expression vector (pFlag-PPAR-α, pFlag-PPAR-β, or pFlag-PPAR-γ) were gifts from Dr. Chatterjee (the University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke's Hospital at Cambridge, UK). For the experiment, 1 μg of 3×AOX-TK-luciferase reporter plasmid were transfected into Ac2F cells in a 48-well plate (1×105 cells/well) with 0.1 μg of effector plasmids, including pcDNA3, or pFlag-PPAR-α/β/γ by using Lipofectamine™ 2000 as the manufacturer's instructions. After transfection for 6 h, the conditioned media was removed and replaced with serum-free media, and the compounds were added. After an additional incubation for 7 h, cells were washed with PBS and assayed with the Luciferase Assay Systems (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Luciferase activity was measured using a GloMax-Multi Microplate Multimode Reader (EnVision, PerkinElmer, Uk).