Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Wheat germ is a by-product of the cereal industry with interesting nutritional properties, including its high protein content. However, so far few applications have been found in the meat industry despite the growing interest in the use of vegetable proteins to reduce meat consumption. Therefore, the use of whet germ for the production of low-fat frankfurters was considered. A control sausage and four formulations with progressive substitution of lean pork (25%, 50%, 75% and 100%) were elaborated. Proximal composition, color, texture, emulsion characterization, fatty acid profile, fat oxidation and consumer acceptance were then analyzed. The results showed that the incorporation of wheat germ improved emulsion stability although the batters were more cohesive. In terms of the final product, the progressive substitution of meat by germ resulted in significant increases in fiber as well as significant decreases in moisture, fat, protein and ash. Sausages made with germ were darker and yellower and less reddish, as well as harder, chewier and gummier, but less cohesive and elastic. Similarly, wheat germ substitution improved the quality of the lipid profile, but decreased acceptability. Substitution of meat was only feasible up to 25%, a formulation for which there was hardly any significant difference with the control.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Food Materials and Adittives

2.2. Sausage Manufacture

2.3. Jelly and Fat Separation

2.4. Emulsion Stability

2.5. Proximate Composition

2.6. Texture and Color

2.7. Fatty Acid Profile and Fat Oxidation Stability

2.8. Sensory Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Emulsion Characteristics

3.2. Proximate Composition

3.3. Color and Texture

3.4. Fatty Acid Profile

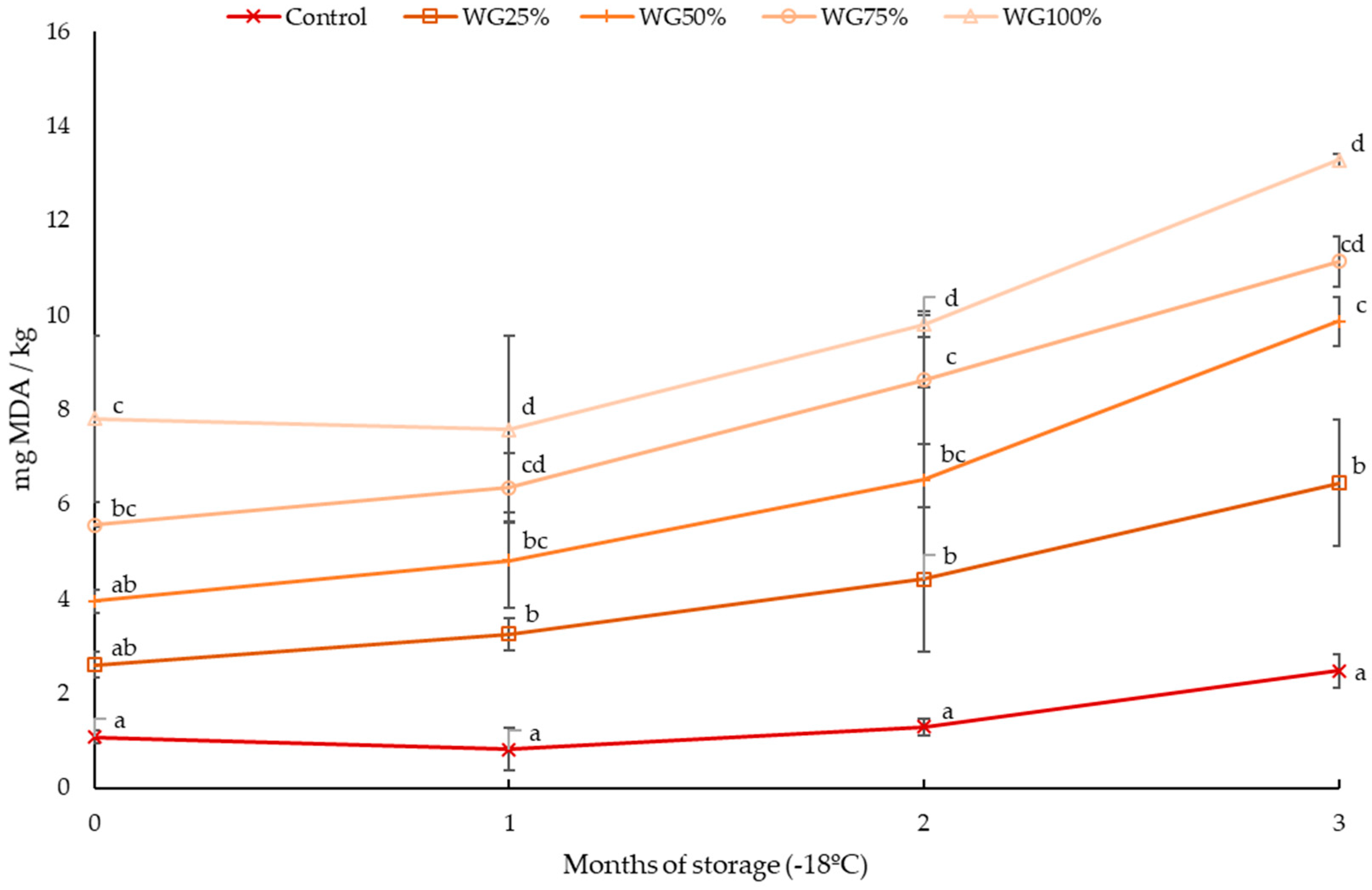

3.5. Fat Oxidation

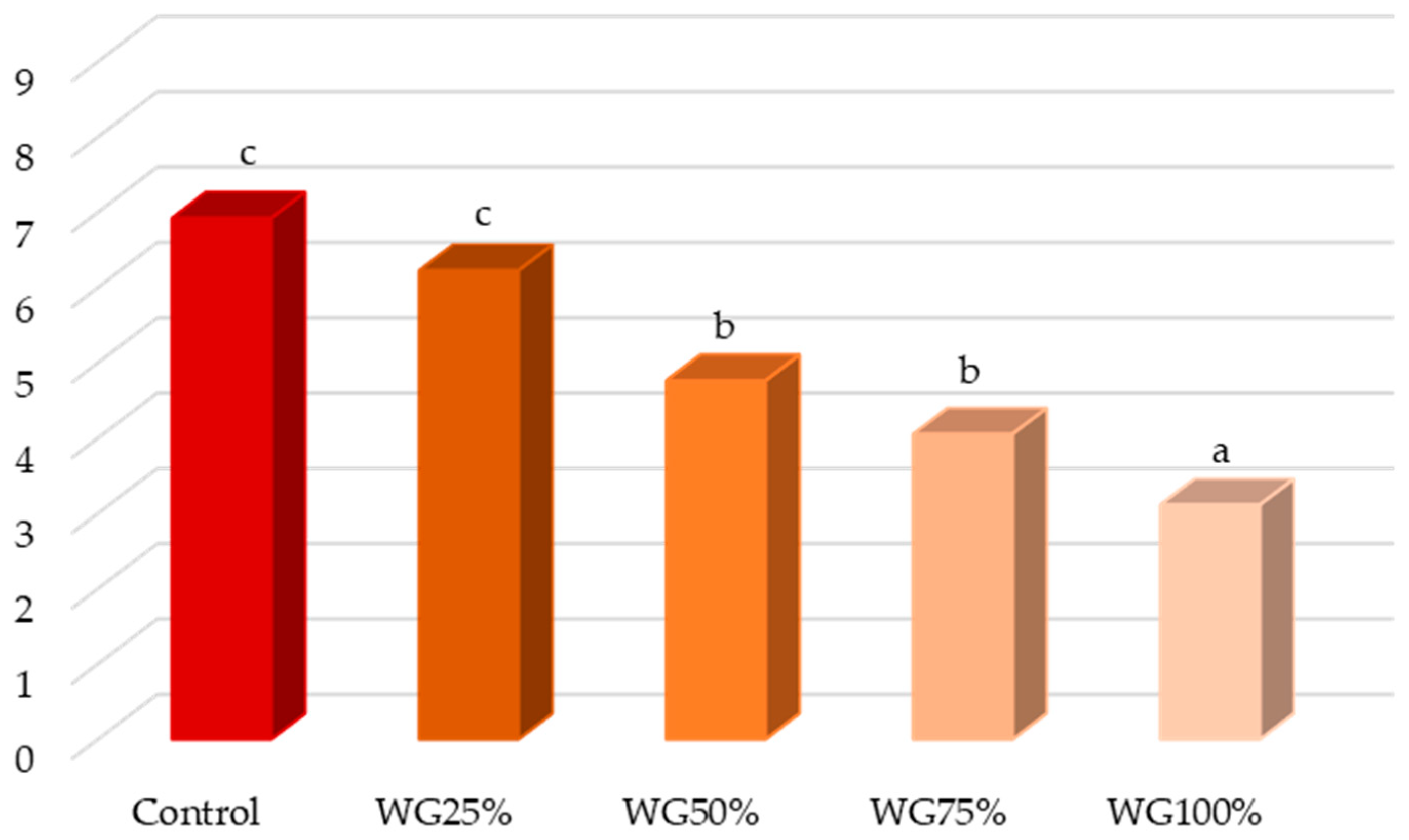

3.6. Sensory Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S.A. Meat Consumption, Health, and the Environment. Science 2018, 361, eaam5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiker, N.R.W.; Bertram, H.C.; Mejborn, H.; Dragsted, L.O.; Kristensen, L.; Carrascal, J.R.; Bügel, S.; Astrup, A. Meat and Human Health—Current Knowledge and Research Gaps. Foods 2021, 10, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekmekcioglu, C.; Wallner, P.; Kundi, M.; Weisz, U.; Haas, W.; Hutter, H.-P. Red Meat, Diseases, and Healthy Alternatives: A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenus, F.; Wirsenius, S.; Johansson, D.J.A. The Importance of Reduced Meat and Dairy Consumption for Meeting Stringent Climate Change Targets. Clim. Change 2014, 124, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, T.; Abrahamse, W. Communicating the Climate Impacts of Meat Consumption: The Effect of Values and Message Framing. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 44, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.A.; Nadeem, M.A.; Nawaz, H.; Amin, M.M.; Abbasi, G.H.; Nadeem, M.; Ali, M.; Ameen, M.; Javaid, M.M.; Maqbool, R.; et al. Pesticides: Impacts on Agriculture Productivity, Environment, and Management Strategies. In Emerging Contaminants and Plants: Interactions, Adaptations and Remediation Technologies; Aftab, T., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 109–134. ISBN 978-3-031-22269-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Gerbens-Leenes, W. The Water Footprint of Global Food Production. Water 2020, 12, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huis, A.V.; Van Itterbeeck, J.; Klunder, H.; Mertens, E.; Halloran, A.; Muir, G.; Vantomme, P. Edible Insect, Future Prospect for Food and Feed Security.

- Bhat, Z.F.; Kumar, S.; Fayaz, H. In Vitro Meat Production: Challenges and Benefits over Conventional Meat Production. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.G.; Heidemann, M.S.; Borini, F.M.; Molento, C.F.M. Livestock Value Chain in Transition: Cultivated (Cell-Based) Meat and the Need for Breakthrough Capabilities. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, B.T.; Wea, A.; Andriati, N. Physicochemical, Sensory Attributes and Protein Profile by SDS-PAGE of Beef Sausage Substituted with Texturized Vegetable Protein. Food Res. 2017, 2, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choton, S.; Gupta, N.; Bandral, J.D.; Anjum, N.; Choudary, A. Extrusion Technology and Its Application in Food Processing: A Review. Pharma Innov. 2020, 9, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P. A., Rodríguez, W., Gómez, E. K. C., & Zambrano, A. A. Estudio Microbiológico y Fisicoquímico de Hongos Comestibles (Pleurotus ostreatus y Pleurotus pulmonarius) Frescos y Deshidratados. [Microbiological and physicochemical study of fresh and dried edible mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus pulmonarius)] Ingenierías & Amazonia, 2024, 7(1).

- Petrusán, J.-I.; Rawel, H.; Huschek, G. Protein-Rich Vegetal Sources and Trends in Human Nutrition: A Review. Curr. Top. Pept. Protein Res, 2016, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Difonzo, G.; Antonino, C.; Squeo, G.; Caponio, F.; Faccia, M. Application of Agri-Food By-Products in Cheesemaking. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rațu, R.N.; Veleșcu, I.D.; Stoica, F.; Usturoi, A.; Arsenoaia, V.N.; Crivei, I.C.; Postolache, A.N.; Lipșa, F.D.; Filipov, F.; Florea, A.M.; et al. Application of Agri-Food By-Products in the Food Industry. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, K.; Özcan, M.M.; AL-Juhaımı, F.; Babıker, E.E.; Sarker, Z.I.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Ahmed, M.A. Nutritional Composition, Extraction, and Utilization of Wheat Germ Oil: A Review. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 119, 1600160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Powers, S.; Field, J.M.; Fido, R.J.; Jones, H.D.; Arnold, G.M.; West, J.; Lazzeri, P.A.; Barcelo, P.; Barro, F.; et al. Comparative Field Performance over 3 Years and Two Sites of Transgenic Wheat Lines Expressing HMW Subunit Transgenes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 113, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewry Jones, H. d., P. r. Transgenic Wheat: Where Do We Stand after the First 12 Years? Ann. Appl. Biol. 2005, 147, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R. The HEALTHGRAIN Programme Opens New Opportunities for Improving Wheat for Nutrition and Health. Nutr. Bull. 2009, 34, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gili, R.D.; Palavecino, P.M.; Cecilia Penci, M.; Martinez, M.L.; Ribotta, P.D. Wheat Germ Stabilization by Infrared Radiation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Sun, A.; Ni, Y.; Cai, T. Some Nutritional and Functional Properties of Defatted Wheat Germ Protein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 6215–6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, H.M.K.E. Assessment of Gross Chemical Composition, Mineral Composition, Vitamin Composition and Amino Acids Composition of Wheat Biscuits and Wheat Germ Fortified Biscuits. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 6, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, J.; Rakić, D.; Fišteš, A.; Pajin, B.; Lončarević, I.; Tomović, V.; Zarić, D. Defatted Wheat Germ Application: Influence on Cookies’ Properties with Regard to Its Particle Size and Dough Moisture Content. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2017, 23, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, T.; Voigt, W. Fermented Wheat Germ Extract - Nutritional Supplement or Anticancer Drug? Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, H.H.M.; Abdel Mageed, M.A.; Lotfy, S.N. Quality and Flavour Stability of Coffee Substitute Prepared by Extrusion of Wheat Germ and Chicory Roots. Amino Acids 2008, 34, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, J.C.; Munekata, P.E.S.; de Carvalho, F.A.L.; Domínguez, R.; Trindade, M.A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Healthy Beef Burgers: Effect of Animal Fat Replacement by Algal and Wheat Germ Oil Emulsions. Meat Sci. 2021, 173, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdaroğlu, M.; Özsümer, M.S. Effects of Soy Protein, Whey Powder And Wheat Gluten On Quality Characteristics of Cooked Beef Sausages Formulated With 5, 10 And 20% Fat. Electronic Journal of Polish Agricultural Universities, 2003, 6(2), 3.

- Elbakheet, S.I.; Elgasim, E.A.; Algadi, M.Z.; Si, E.; Ea, E.; Mz, A. Utilization of Wheat Germ Flour in the Processing of Beef Sausage. 2018, Adv Food Process Technol: AFPT-101 100001.

- Güngör, E.; Gökoğlu, N. Determination of Microbial Contamination Sources at a Frankfurter Sausage Processing Line. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2010, 34, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizer Rocha, Y.J.; Lapa-Guimarães, J.; de Noronha, R.L.F.; Trindade, M.A. Evaluation of Consumers’ Perception Regarding Frankfurter Sausages with Different Healthiness Attributes. J. Sens. Stud. 2018, 33, e12468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bis-Souza, C.V.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Penna, A.L.B.; Barretto, A.C.S. New Strategies for the Development of Innovative Fermented Meat Products: A Review Regarding the Incorporation of Probiotics and Dietary Fibers. Food Rev. Int. 2019, 35, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaza M, Y.L.; Restrepo M, D.A.; López V, J.H.; Ochoa G, O.A.; Cabrera T, K.R. Evolution of The Antioxidant Capacity of Frankfurter Sausage Model Systems with Added Cherry Extract (Prunus Avium L.) During Refrigerated Storage. Vitae 2011, 18, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Jung, E.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, J.-J.; Choi, Y.-I. Effect of Replacing Pork Fat with Vegetable Oils on Quality Properties of Emulsion-Type Pork Sausages. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2015, 35, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.A.L.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Barba-Orellana, S.; Mattar, J.; Rimac Brnčić, S.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M. Replacement of Meat by Spinach on Physicochemical and Nutritional Properties of Chicken Burgers. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti-Quijal, F.J.; Zamuz, S.; Tomašević, I.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Marszałek, K.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M. A Chemometric Approach to Evaluate the Impact of Pulses, Chlorella and Spirulina on Proximate Composition, Amino Acid, and Physicochemical Properties of Turkey Burgers. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 3672–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamuz, S.; Purriños, L.; Galvez, F.; Zdolec, N.; Muchenje, V.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M. Influence of the Addition of Different Origin Sources of Protein on Meat Products Sensory Acceptance. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, P.F.; Silva, C.F. da; Ferreira, J.P.; Guerra, J.M.C. Vegetable-Based Frankfurter Sausage Production by Different Emulsion Gels and Assessment of Physical-Chemical, Microbiological and Nutritional Properties. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, I.; Santos, S.; Hernández-Jiménez, M.; Vivar-Quintana, A.M. The Effects of the Progressive Replacement of Meat with Texturized Pea Protein in Low-Fat Frankfurters Made with Olive Oil. Foods 2022, 11, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçal, C.; Pinto, C.A.; Silva, A.M.S.; Monteiro, C.; Saraiva, J.A.; Cardoso, S.M. Macroalgae-Fortified Sausages: Nutritional and Quality Aspects Influenced by Non-Thermal High-Pressure Processing. Foods 2021, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloukas, I.; Honikel, K.O. The Influence of Mincing and Temperature of Storage on the Oxidation of Pork Back Fat and Its Effect on Water- and Fat-Binding in Finely Comminuted Batters. Meat Sci. 1992, 32, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurueña-Martínez, M.; Revilla, I.; M Vivar-Quintana, A. New Formulations for Low-Fat Frankfurters and Its Effect on Product Quality. Czech J. Food Sci. 2004, 22, S333–S337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.; Cofrades, S.; Troy, D.J. Effects of Fat Level, Oat Fibre and Carrageenan on Frankfurters Formulated with 5, 12 and 30% Fat. Meat Sci. 1997, 45, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G.H.S. A Simple Method for the Isolation and Purification of Total Lipides from Animal Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buege, J.A.; Aust, S.D. [30] Microsomal Lipid Peroxidation. In Methods in Enzymology; Fleischer, S., Packer, L., Eds.; Biomembranes - Part C: Biological Oxidations; Academic Press, 1978; Vol. 52, pp. 302–310.

- Thushan Sanjeewa, W.G.; Wanasundara, J.P.D.; Pietrasik, Z.; Shand, P.J. Characterization of Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum L.) Flours and Application in Low-Fat Pork Bologna as a Model System. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.J.; Tung, M.A. Functional Properties of Modified Oilseed Protein Concentrates and Isolates. Can. Inst. Food Sci. Technol. J. 1983, 16, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Llovera, M.; Giner, E.; Fiszman, S.; Salvador, A.; Flores, J. Effect of a New Emulsifier Containing Sodium Stearoyl-2-Lactylate and Carrageenan on the Functionality of Meat Emulsion Systems. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedna, M.; Prinyawiwatkul, W.; Rao, R.M. Solubilized Wheat Protein Isolate: Functional Properties and Potential Food Applications. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamani, M.H.; Meera, M.S.; Bhaskar, N.; Modi, V.K. Partial and Total Replacement of Meat by Plant-Based Proteins in Chicken Sausage: Evaluation of Mechanical, Physico-Chemical and Sensory Characteristics. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 2660–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnanasambandam, R.; Zayas, J.F. Quality Characteristics of Meat Batters and Frankfurters Containing Wheat Germ Protein Flour. J. Food Qual. 1994, 17, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El- Sayed, S.M.; Farag, S.E.; El-Sayed, S.A.M. Utilization of Some Chicken Edible Internal Organs and Wheat Germ in Production of Sausage. J. Food Dairy Sci. 2018, 9, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İbanoǧlu, E. Kinetic Study on Colour Changes in Wheat Germ Due to Heat. J. Food Eng. 2002, 51, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govari, M.; Pexara, A. Nitrates and Nitrites in Meat Products. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2015, 66, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdaroğlu, M.; Özsümer, M.S. Effects of soy protein, whey powder and wheat gluten on quality characteristics of cooked beef sausages formulated with 5, 10 and 20% fat. Elect. J. Polish Agric. Univ. 2003, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Garcı́a, M.L.; Dominguez, R.; Galvez, M.D.; Casas, C.; Selgas, M.D. Utilization of Cereal and Fruit Fibres in Low Fat Dry Fermented Sausages. Meat Sci. 2002, 60, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A. Effect of Orange Dietary Fibre, Oregano Essential Oil and Packaging Conditions on Shelf-Life of Bologna Sausages. Food Control 2010, 21, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd EL-Rahman, A.M.M. 2015.

- Wood, J.D.; Enser, M.; Fisher, A.V.; Nute, G.R.; Sheard, P.R.; Richardson, R.I.; Hughes, S.I.; Whittington, F.M. Fat Deposition, Fatty Acid Composition and Meat Quality: A Review. Meat Sci. 2008, 78, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho de Oliveira, T.L.; Malfitano de Carvalho, S.; de Araújo Soares, R.; Andrade, M.A.; Cardoso, M. das G.; Ramos, E.M.; Piccoli, R.H. Antioxidant Effects of Satureja montana L. Essential Oil on TBARS and Color of Mortadella-Type Sausages Formulated with Different Levels of Sodium Nitrite. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 45, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, A.; Cegielska-Radziejewska, R.; Szablewski, T.; Zabielski, J. TBARS and Microbial Growth Predicative Models of Pork Sausage Stored at Different Temperatures. Czech J. Food Sci. 2015, 33, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzocchi, S.; Caboni, M.F.; Greco Miani, M.; Pasini, F. Wheat Germ and Lipid Oxidation: An Open Issue. Foods 2022, 11, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Sung, J.-M.; Cho, H.J.; Woo, S.-H.; Kang, M.-C.; Yong, H.I.; Kim, T.-K.; Lee, H.; Choi, Y.-S. Natural Extracts as Inhibitors of Microorganisms and Lipid Oxidation in Emulsion Sausage during Storage. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2021, 41, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhao, L.; Chen, H.; Sun, D.; Deng, B.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F. Inactivation of Lipase and Lipoxygenase of Wheat Germ with Temperature-Controlled Short Wave Infrared Radiation and Its Effect on Storage Stability and Quality of Wheat Germ Oil. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0167330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chi, C.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, Y. Comparison of Wheat Germ and Oil Characteristics and Stability by Different Stabilization Techniques. LWT 2024, 191, 115664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjiao, F.; Yongkui, Z.; Yunchuan, C.; Junxiu, S.; Yuwen, Y. TBARS Predictive Models of Pork Sausages Stored at Different Temperatures. Meat Sci. 2014, 96, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, C.K.B.; Torres, E.A.F.S. Lipid Oxidation and Quality Parameters of Sausages Marketed Locally in the Town of Săo Paulo (Brazil). Czech J. Food Sci. 2002, 20, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J.A. Thiobarbituric Acid Test for Monitoring Lipid Oxidation in Meat. Food Chem. 1997, 59, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | Control | WG25% | WG50% | WG75% | WG100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean pork | 40 | 30 | 20 | 10 | 0 |

| Wheat germ | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| Olive oil | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| Locust bean/xantham gum | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Ice | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Polyphosphate | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Nitrite salt1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Potato starch | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Soy protein | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sodium ascorbate | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Dextrose | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Sodium lactate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Flavorings | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Onion | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Garlic | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Pepper | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Control | WG25% | WG50% | WG75% | WG100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back-extrusion force (N) | 3.80±0.78a | 5.56±0.59a | 9.61±2.24ab | 17.48±7.20b | 32.18±15.25c |

| Back-extrusion area (N·s) | 28.70±5.67a | 20.82±12.13a | 21.55±12.76a | 67.79±43.74a | 134.97±89.16b |

| %TEF | 4.14±0.75b | 3.92±1.53b | 2.55±0.81a | 1.24±1.27a | 1.41±0.54a |

| %Fat | 2.92±1.68a | 3.27±0.99a | 6.32±2.14b | 6.51±0.62b | 6.56±0.67b |

| Jelly/fat separation (%) | 0.193±0.13b | 0.074±0.07a | 0.013±0.01a | 0.005±0.01a | 0.003±0.01a |

| Wheat Germ | Control | WG25% | WG50% | WG75% | WG100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 8.37±0.18 | 61.88±3.20c | 56.86±4.20c | 48.67±2.59b | 45.47±3.94ab | 39.87±5.98a |

| Total fat (%) | 7.64±0.13 | 12.26±1.53b | 9.21±1.43a | 8.96±1.12a | 8.09±0.85a | 7.92±1.00a |

| Protein (%) | 25.75±0.21 | 11.51±0.84a | 10.90±1.15a | 12.20±0.95a | 12.11±3.26a | 13.27±1.34a |

| Ash (%) | 4.30±0.03 | 3.29±0.35a | 3.39±0.35a | 3.60±0.16a | 3.93±0.18a | 4.70±0.68b |

| Fiber (%) | 24.90±0.85 | 2.23±0.95a | 3.70±0.29a | 6.25±1.67b | 7.45±1.65bc | 9.63±1.64c |

| Carbohydrate (%) | 29.05±0.92 | 8.53±0.27a | 15.94±1.66b | 20.07±1.11bc | 21.96±2.78bc | 24.61±3.56c |

| Starch (%) | 17.45±0.35 | 3.29±0.37a | 5.04±0.24b | 6.68±0.02c | 7.75±0.63d | 9.89±0.15e |

| Control | WG25% | WG50% | WG75% | WG100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | 64.24±1.65e | 59.04±1.39d | 56.82±1.37c | 51.10±0.71b | 45.50±1.50a |

| a* | 19.50±0.38b | 15.92±0.69a | 15.94±0.80a | 16.03±1.93a | 15.20±1.39a |

| b* | 30.90±1.25ab | 22.88±2.68a | 31.07±1.88ab | 33.51±5.85b | 31.39±5.69ab |

| Hardness (g) | 1964.63±509.48a | 1901.98±264.14a | 2947.78±556.36b | 3698.22±370.19c | 4947.98±334.02d |

| Adhesiveness (g·mm) | -1.32±1.83a | -0.43±0.79a | -0.88±1.42a | -0.11±0.08a | -0.30±0.57a |

| Springiness (mm) | 0.95±0.15d | 0.86±0.05c | 0.80±0.05c | 0.70±0.07b | 0.62±0.40a |

| Cohesiveness | 0.76±0.04d | 0.68±0.05c | 0.64±0.09b | 0.62±0.06b | 0.53±0.05a |

| Gumminess (g) | 1478.49±315.29a | 1297.29±186.77a | 1887.94±508.74b | 2277.53±181.36c | 2624.37±210.53d |

| Chewiness (g·mm) | 1426.65±535.57b | 1121.46±203.04a | 1532.16±487.62b | 1611.54±269.10b | 1622.40±135.70b |

| Wheat Germ | Control | WG25% | WG50% | WG75% | WG100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6:0 | 0.35±0.14 | 0.04±0.05a | 0.01±0.01a | 0.04±0.03a | 0.02±0.02a | 0.02±0.00a |

| C8:0 | 0.65±0.11 | 0.03±0.02a | n.d. | n.d. | 0.02±0.01a | n.d. |

| C10:0 | 0.08±0.10 | 0.03±0.00b | 0.03±0.01b | 0.03±0.01b | 0.02±0.00ab | 0.01±0.00a |

| C11:0 | 0.03±0.00 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.09±0.10a | n.d. | 0.01±0.02a |

| C12:0 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.03±0.00b | 0.03±0.01b | 0.03±0.01b | 0.02±0.00a | 0.02±0.00a |

| C13:0 | 0.06±0.00 | 0.08±0.11a | 0.02±0.00a | 0.09±0.10a | 0.02±0.01a | 0.02±0.00a |

| C14:0 | 0.27±0.03 | 0.31±0.04c | 0.28±0.07c | 0.22±0.02b | 0.14±0.01a | 0.10±0.00a |

| C14:1n5 | 0.06±0.04 | 0.03±0.01a | 0.02±0.00a | 0.03±0.01a | 0.02±0.00a | 0.03±0.01a |

| C15:0 | 0.17±0.03 | 0.04±0.02a | 0.01±0.02a | 0.02±0.01a | 0.02±0.00a | 0.03±0.01a |

| C15:1 | 0.03±0.04 | 0.05±0.06a | 0.14±0.01a | 0.13±0.03a | 0.12±0.06a | 0.14±0.03a |

| C16:0 | 37.69±1.84 | 15.39±0.33a | 15.87±0.49a | 15.55±0.46a | 15.08±0.23a | 15.40±0.29a |

| C16:1 | 0.41±0.10 | 0.19±0.01a | 0.19±0.03a | 0.16±0.01a | 0.60±0.61a | 0.84±0.48a |

| C17:0 | 0.47±0.01 | 1.48±0.04c | 1.47±0.03c | 1.28±0.03b | 0.08±0.08a | 0.03±0.00a |

| C17:1 | 0.21±0.27 | 0.19±0.01ab | 0.23±0.03b | 0.19±0.02ab | 0.20±0.04ab | 0.16±0.01a |

| C18:0 | 0.64±1.00 | 4.84±0.34c | 0.02±0.00a | 1.23±2.07ab | 3.30±0.12bc | 2.10±1.39ab |

| C18:1n9t | 0.31±0.02 | 0.37±0.11a | 0.64±0.15b | 0.59±0.07b | 0.58±0.11b | 0.55±0.05b |

| C18:1 n9c | 24.08±0.39 | 62.22±0.35bc | 63.57±0.88c | 60.51±0.77b | 57.36±1.58a | 55.66±1.45a |

| C18:2n6t | 0.10±0.01 | 0.04±0.01a | 0.08±0.09a | 0.03±0.01a | 0.02±0.01a | 0.03±0.02a |

| C18:2 n6 | 26.23±0.47 | 11.67±0.40a | 13.79±0.37b | 15.60±0.79b | 18.40±1.35c | 20.35±1.16c |

| C20:0 | 0.39±0.31 | 0.43±0.01a | 0.43±0.01a | 0.43±0.01a | 0.42±0.03a | 0.41±0.01a |

| C18:3 n6 | 0.36±0.05 | 0.05±0.01a | 0.08±0.09a | 0.03±0.01a | 0.02±0.01a | 0.03±0.02a |

| C20:1 n9 | 1.24±0.94 | 0.04±0.01a | 0.05±0.01a | 0.07±0.04a | 0.05±0.01a | 0.05±0.01a |

| C18:3 n3 | 2.27±0.07 | 0.71±0.01a | 1.08±0.03b | 1.46±0.09c | 1.96±0.19d | 2.30±0.15e |

| C21:0 | 0.30±0.02 | 0.03±0.00a | 0.04±0.02a | 0.03±0.02a | 0.02±0.01a | 0.03±0.02a |

| C20:2 n6 | 0.31±0.01 | 0.30±0.10a | 0.44±0.01a | 0.25±0.09a | 0.25±0.04a | 0.30±0.10a |

| C22:0 | 0.27±0.04 | 0.13±0.00a | 0.15±0.00a | 0.03±0.01a | 0.09±0.08a | 0.10±0.08a |

| C20:3 n6 | 0.09±0.03 | 0.05±0.00a | 0.07±0.03a | 0.04±0.01a | 0.03±0.02a | 0.17±0.19a |

| C22:1 n9 | 0.68±0.04 | 0.19±0.05a | 0.30±0.00a | 0.17±0.05a | 0.22±0.10a | 0.27±0.08a |

| C20:3 n3 | 0.15±0.03 | 0.03±0.00a | 0.03±0.01a | 0.02±0.00a | 0.11±0.13a | 0.03±0.00a |

| C23:0 | 0.15±0.14 | 0.27±0.04c | 0.21±0.01c | 0.11±0.03b | 0.10±0.02b | 0.01±0.01a |

| C20:4 n6 | 0.23±0.01 | 0.15±0.11a | 0.08±0.01a | 0.08±0.02a | 0.06±0.05a | 0.11±0.03a |

| C22:2 n6 | 0.17±0.02 | 0.06±0.06a | 0.01±0.01a | 0.02±0.00a | 0.02±0.00a | 0.02±0.00a |

| C24:0 | 0.33±0.18 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.06±0.09a | 0.05±0.02a | 0.03±0.05a |

| C20:5 n3 | 0.26±0.10 | 0.05±0.00a | 0.07±0.00a | 0.04±0.03a | 0.06±0.02a | 0.06±0.02a |

| C24:1 n9 | 0.42±0.27 | 0.15±0.22a | 0.04±0.01a | 0.03±0.00a | 0.04±0.01a | 0.05±0.01a |

| C22:4 n3 | 0.17±0.06 | 0.06±0.01b | 0.05±0.00b | 0.03±0.00a | 0.02±0.01a | 0.02±0.00a |

| C22:5 n3 | 0.28±0.19 | 0.14±0.18a | 0.05±0.02a | 0.86±1.45a | 0.02±0.03a | 0.02±0.00a |

| C22:6 n3 | 0.31±0.20 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.04±0.08a |

| SFA | 41.85±0.83 | 23.06±0.42b | 18.59±0.54a | 19.16±1.46a | 19.35±0.54a | 18.27±1.51a |

| MUFA | 28.35±0.59 | 63.78±0.61bc | 65.61±1.03c | 62.34±0.84b | 59.66±1.76a | 58.25±1.29a |

| PUFA | 29.80±1.43 | 13.17±0.27a | 15.80±0.49ab | 18.50±1.57bc | 21.00±1.61cd | 23.48±1.47e |

| n3 | 2.42±1.00 | 0.98±0.18a | 1.28±0.03a | 2.41±1.44a | 2.17±0.27a | 2.46±0.22a |

| n6 | 27.38±0.42 | 12.19±0.36a | 14.52±0.47b | 16.09±0.80b | 18.82±1.36c | 21.03±1.26d |

| P/S | 0.68±1.71 | 0.57±0.01a | 0.85±0.00b | 0.97±0.14b | 1.09±0.08bc | 1.30±0.19c |

| n6/n3 | 7.65±0.42 | 12.79±2.28a | 11.37±0.14a | 8.15±3.67a | 8.70±0.54a | 8.57±0.28a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).