Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

| species | origin | comment |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | laboratory strain collection | surrogate food spoilage |

| Citrobacter koseri | laboratory strain collection | fish-borne pathogen |

| Listeria monocytogenes | DSM 20600 | food pathogen |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 15442 | food spoilage & pathogen |

| Salmonella enterica | LT-2 | food pathogen |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | laboratory strain collection | surrogate food pathogen |

| Staphylococcus warneri | laboratory strain collection | surrogate food pathogen |

2.2. Species Identification Through 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

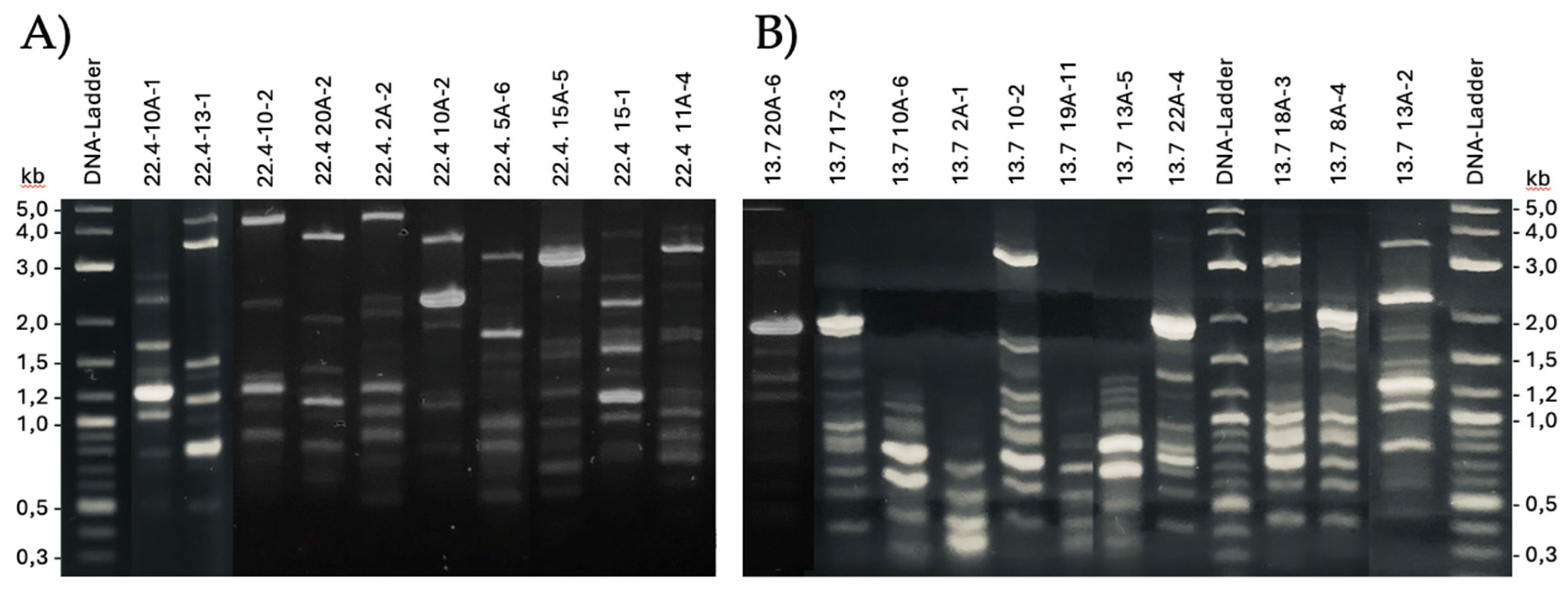

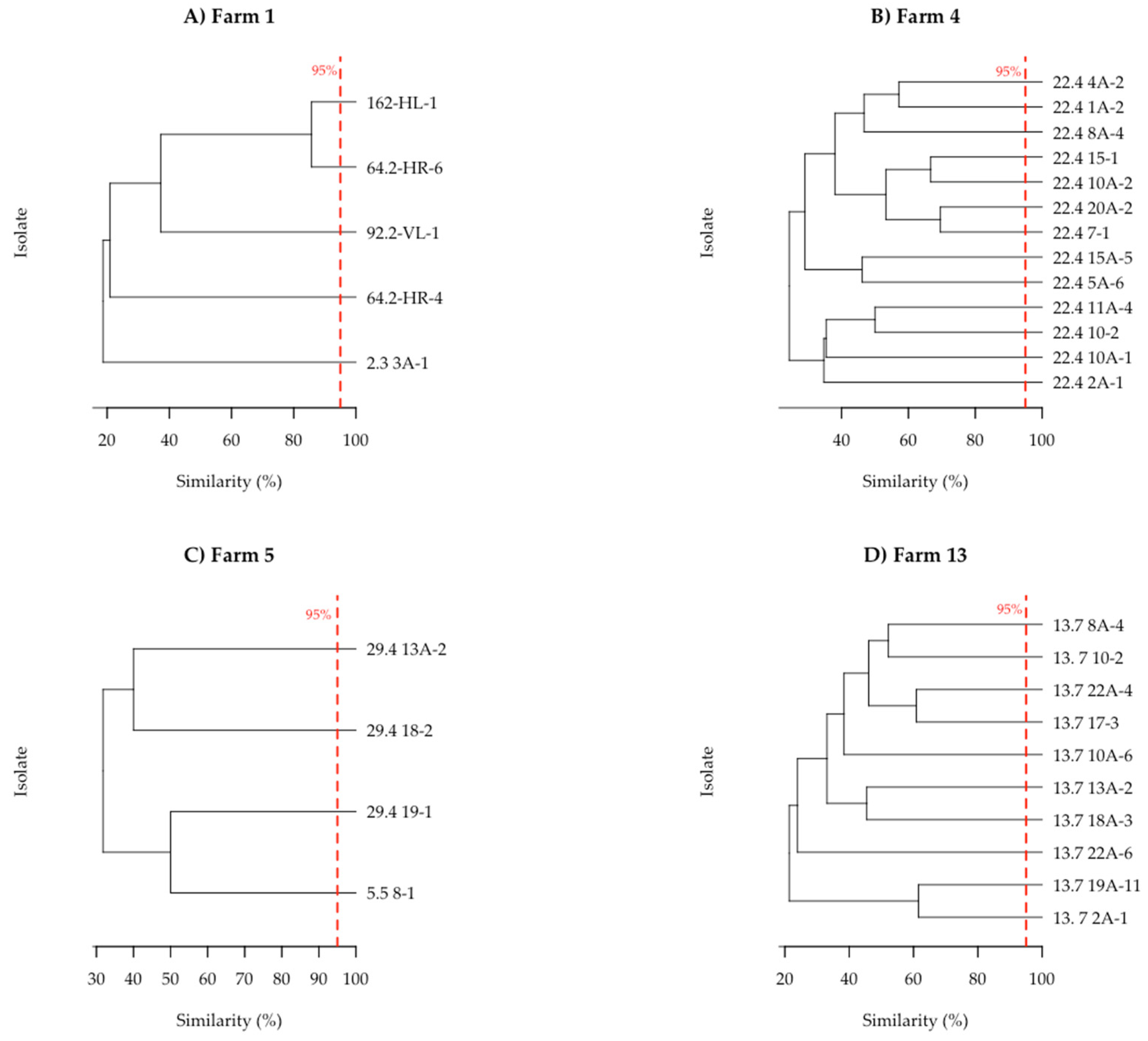

2.3. Random-Amplified-Polymorphic-DNA Analysis (RAPD)

2.4. Hydrogen Peroxide Production

2.5. In Vivo Detection of Antimicrobial Activity

2.5. Whole Genome Sequencing

2.6. Data Analyses and Statistics

2.7. Bioinformatics Pipeline and Genome Assembly

2.8. Genome Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Pediococcus Pentosaceus Strains from the Cattle Udder

3.2. Identification of Subspecies

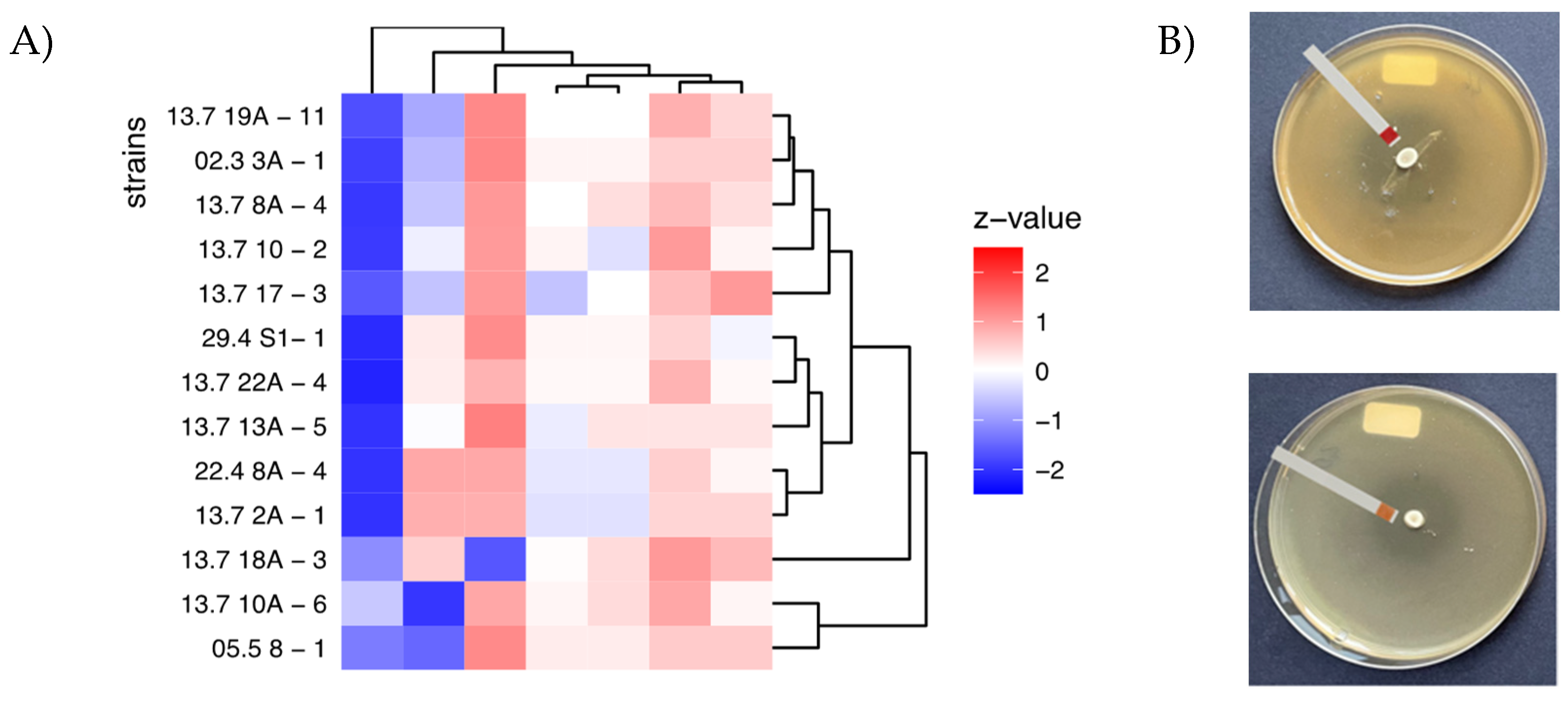

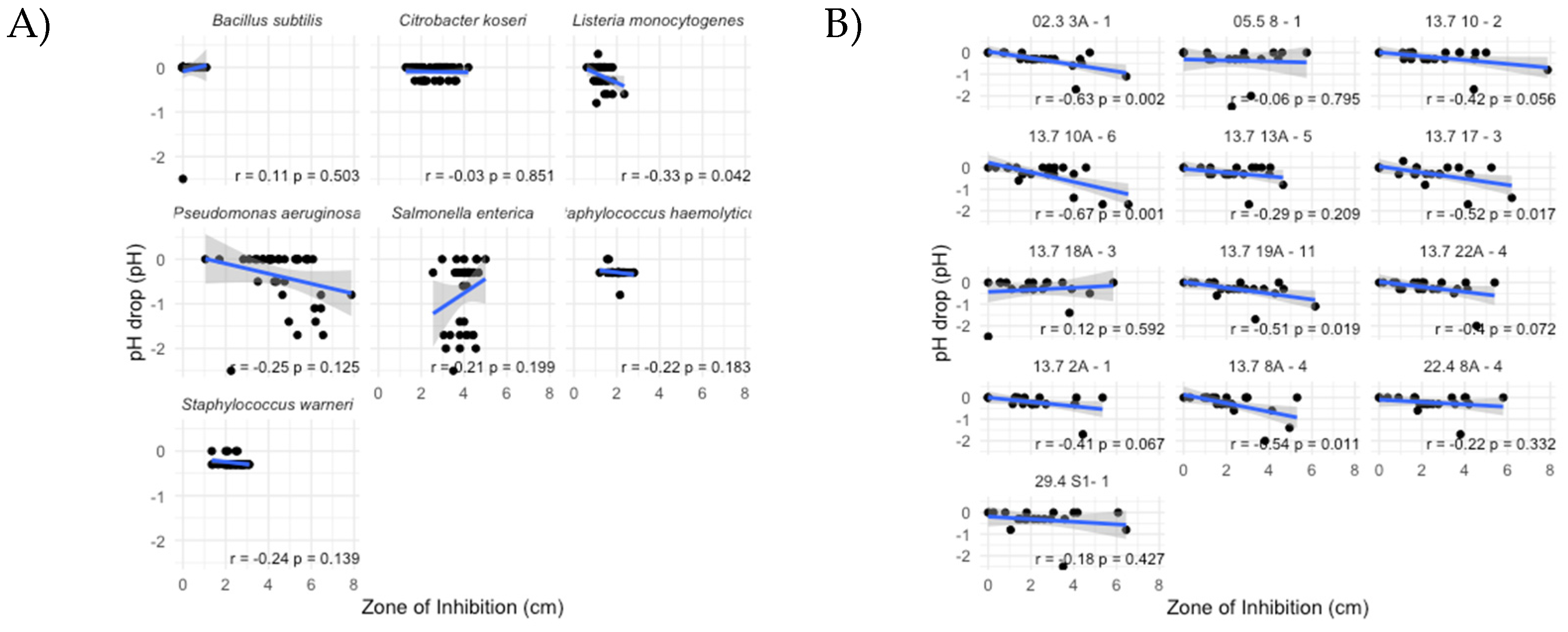

3.3. Antimicrobial Profiles

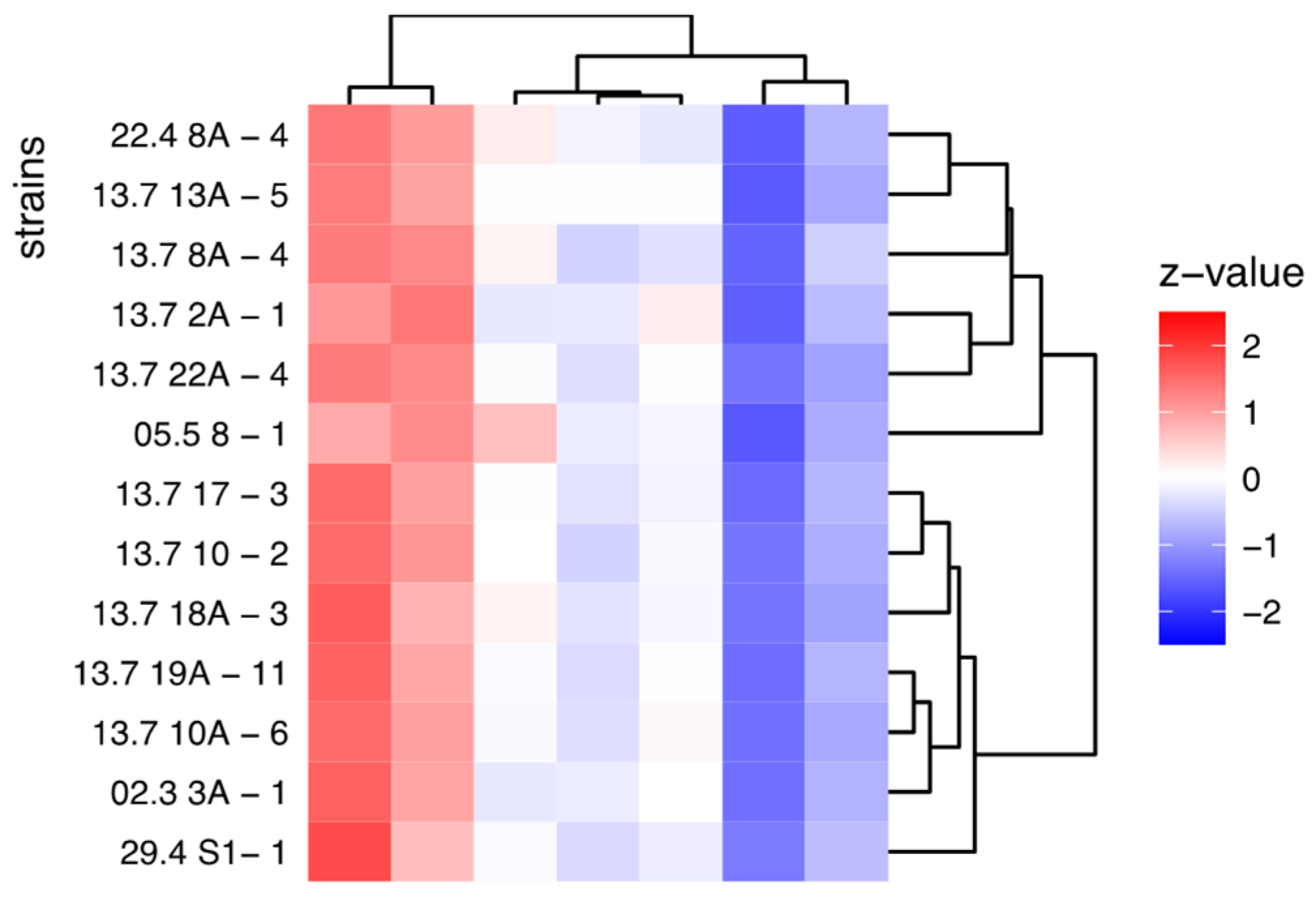

3.4. Acidification

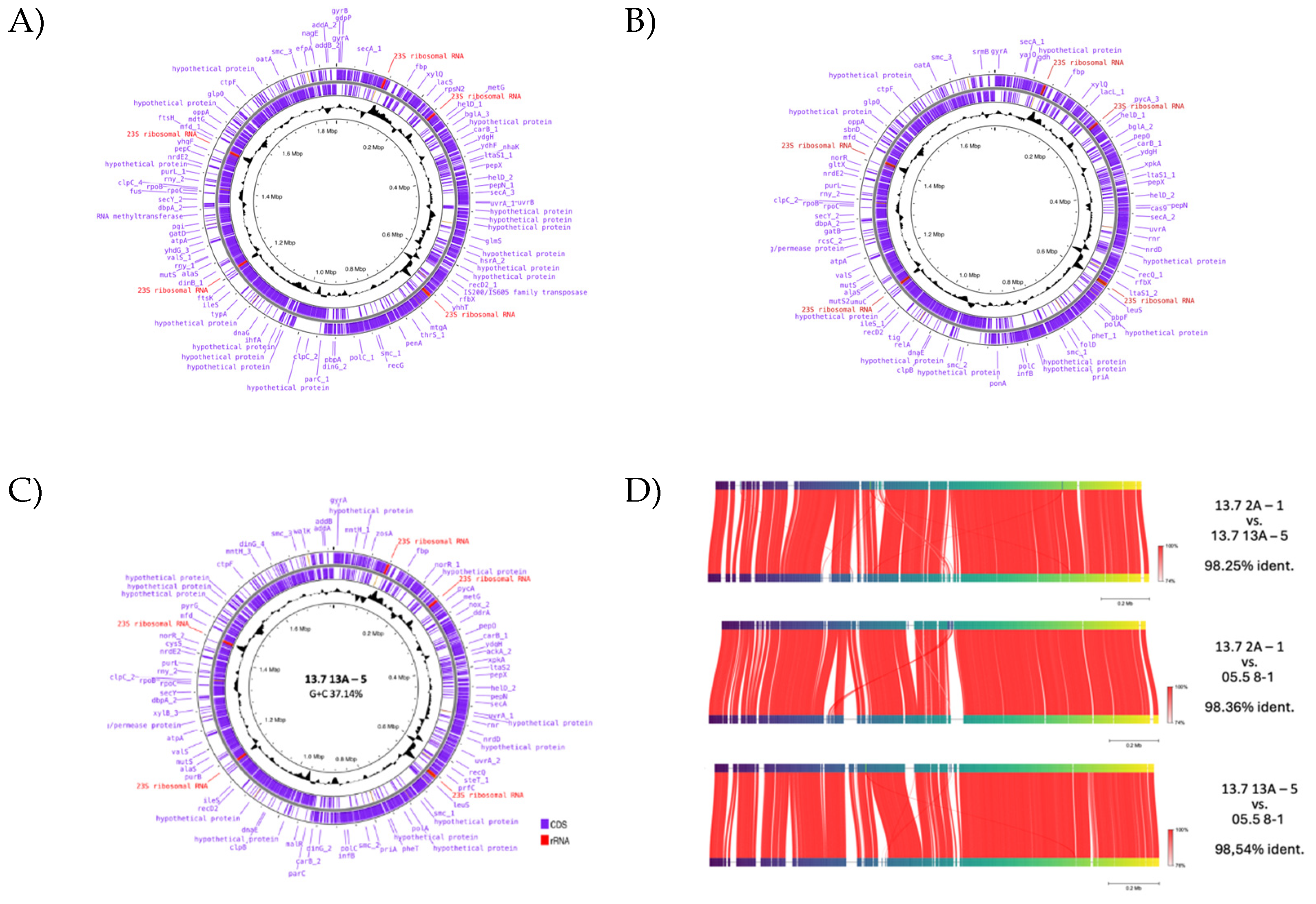

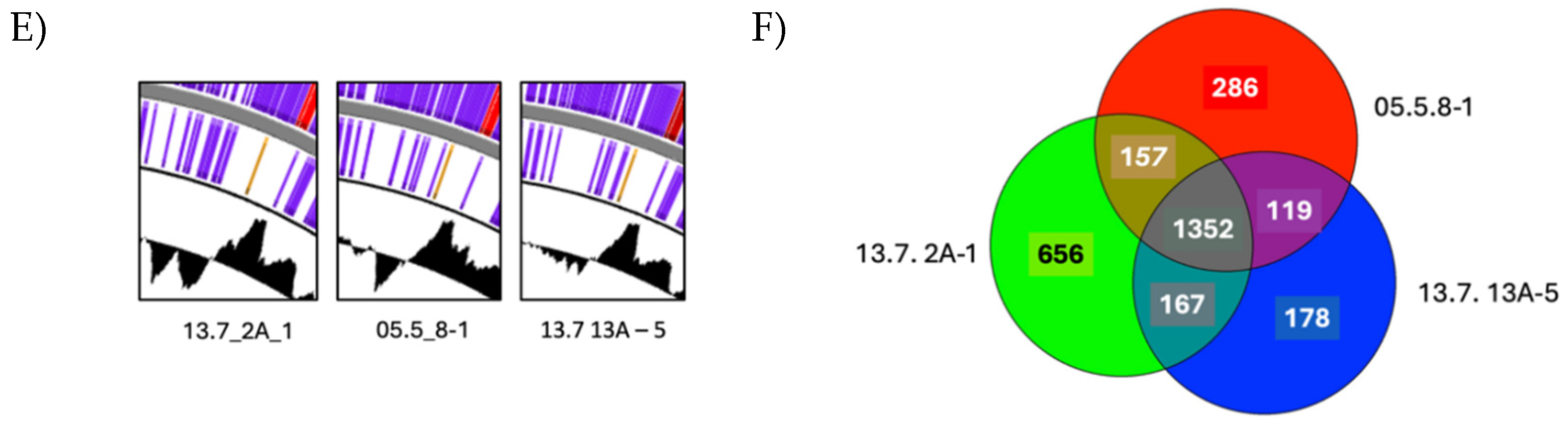

3.6. Genome Analyses

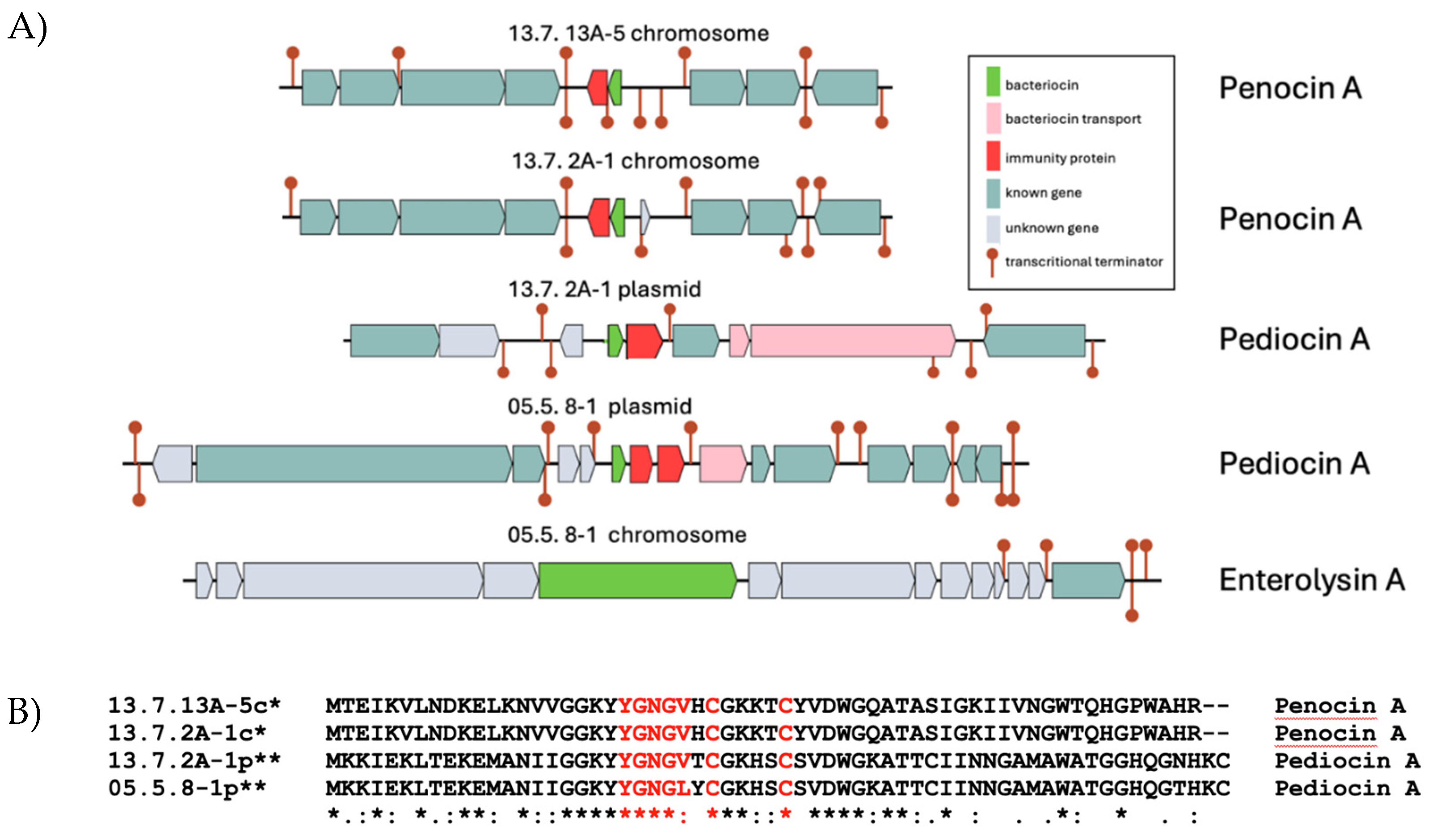

3.7. Bacteriocin Encoding Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ozen, M.; Dinleyici, E.C. The History of Probiotics: The Untold Story. Beneficial Microbes 2015, 6, 159–166. [CrossRef]

- Bamforth, C.W.; Cook, D.J. Food, Fermentation and Microorganisms; 2nd ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, 2019; ISBN 978-1-119-55743-2.

- Fischer, S.W.; Titgemeyer, F. Protective Cultures in Food Products: From Science to Market. Foods 2023, 12, 1541. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, A.A.; Pinto-Neto, W. de P.; da Paixão, G.A.; Santos, D. da S.; De Morais, M.A.; De Souza, R.B. Journey of the Probiotic Bacteria: Survival of the Fittest. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 95. [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevic, T.; Shah, N.P. Probiotics—From Metchnikoff to Bioactives. International Dairy Journal 2008, 18, 714–728. [CrossRef]

- Parche, S.; Amon, J.; Jankovic, I.; Rezzonico, E.; Beleut, M.; Barutçu, H.; Schendel, I.; Eddy, M.P.; Burkovski, A.; Arigoni, F.; et al. Sugar Transport Systems of Bifidobacterium Longum NCC2705. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology 2006, 12, 9–19. [CrossRef]

- Foligné, B.; Daniel, C.; Pot, B. Probiotics from Research to Market: The Possibilities, Risks and Challenges. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2013, 16, 284–292. [CrossRef]

- Redzepi, R.; Zilber, D.; Sung, E.; Troxler, P. The Noma Guide to Fermentation: Foundations of Flavour; Artisan: New York, 2018; ISBN 978-1-57965-718-5.

- Katz, S.E. Wild Fermentation: The Flavor, Nutrition, and Craft of Live-Culture Foods; Revised and updated edition.; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, Vermont, 2016; ISBN 978-1-60358-628-3.

- Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology; Boone, D.R., Castenholz, R.W., Garrity, G.M., Eds.; 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-98771-2.

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A Taxonomic Note on the Genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 Novel Genera, Emended Description of the Genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and Union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Cai, L.; Lv, L.; Li, L. Pediococcus Pentosaceus, a Future Additive or Probiotic Candidate. Microbial Cell Factories 2021, 20, 45. [CrossRef]

- Raccach, M. Pediococcus. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Second Edition); Batt, C.A., Tortorello, M.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2014; pp. 1–5 ISBN 978-0-12-384733-1.

- Spitaels, F.; Wieme, A.D.; Janssens, M.; Aerts, M.; Daniel, H.-M.; Landschoot, A.V.; Vuyst, L.D.; Vandamme, P. The Microbial Diversity of Traditional Spontaneously Fermented Lambic Beer. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e95384. [CrossRef]

- Spitaels, F.; Wieme, A.D.; Janssens, M.; Aerts, M.; Van Landschoot, A.; De Vuyst, L.; Vandamme, P. The Microbial Diversity of an Industrially Produced Lambic Beer Shares Members of a Traditionally Produced One and Reveals a Core Microbiota for Lambic Beer Fermentation. Food Microbiology 2015, 49, 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Huang, L.; Zeng, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, D.; Xie, J.; Xie, J.; Tu, Q.; Deng, D.; Yin, J. Pediococcus Pentosaceus: Screening and Application as Probiotics in Food Processing. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Porto, M.C.W.; Kuniyoshi, T.M.; Azevedo, P.O.S.; Vitolo, M.; Oliveira, R.P.S. Pediococcus Spp.: An Important Genus of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Pediocin Producers. Biotechnology Advances 2017, 35, 361–374. [CrossRef]

- Vandenbergh, P.A. Lactic Acid Bacteria, Their Metabolic Products and Interference with Microbial Growth. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 1993, 12, 221–237. [CrossRef]

- De Man, J.C.; Rogosa, M.; Sharpe, M.E. A MEDIUM FOR THE CULTIVATION OF LACTOBACILLI. Journal of Applied Bacteriology 1960, 23, 130–135. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Lee, Y. A Differential Medium for Lactic Acid-Producing Bacteria in a Mixed Culture. Lett Appl Microbiol 2008, 46, 676–681. [CrossRef]

- Ames, B.N.; McCann, J.; Yamasaki, E. Methods for Detecting Carcinogens and Mutagens with the Salmonella/Mammalian-Microsome Mutagenicity Test. Mutation Research/Environmental Mutagenesis and Related Subjects 1975, 31, 347–363. [CrossRef]

- Judicial Commission of the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes The Type Species of the Genus Salmonella Lignieres 1900 Is Salmonella Enterica (Ex Kauffmann and Edwards 1952) Le Minor and Popoff 1987, with the Type Strain LT2T, and Conservation of the Epithet Enterica in Salmonella Enterica over All Earlier Epithets That May Be Applied to This Species. Opinion 80. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2005, 55, 519–520. [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, L.; Giraffa, G. Rapid Identification of Dairy Lactic Acid Bacteria by M13-Generated, RAPD-PCR Fingerprint Databases. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2005, 63, 135–144. [CrossRef]

- Sirichoat, A.; Flórez, A.B.; Vázquez, L.; Buppasiri, P.; Panya, M.; Lulitanond, V.; Mayo, B. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles of Lactic Acid Bacteria from the Human Vagina and Genetic Basis of Acquired Resistances. IJMS 2020, 21, 2594. [CrossRef]

- Tomás, M.S.J.; Claudia Otero, M.; Ocaña, V.; Elena Nader-Macías, M. Production of Antimicrobial Substances by Lactic Acid Bacteria I: Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Spencer, J.F.T., Ed.; Public Health Microbiology: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: New Jersey, 2004; Vol. 268, pp. 337–346 ISBN 978-1-59259-766-6. [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, B.A.; Adetoye, A.; Ayeni, F.A. Antibacterial Activities of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Cow Faeces against Potential Enteric Pathogens. Afr Health Sci 2015, 15, 888–895. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.K.; Singh, B.; Tiwari, S.K. Comparative Analysis of Inhibition-Based and Indicator-Independent Colorimetric Assay for Screening of Bacteriocin-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria. 2021, 687–695. [CrossRef]

- Nanopore Technologies MinKNOW.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2021.

- RStudio Team RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R 2022.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 2019, 4, 1686. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Bryan, J. Readxl: Read Excel Files 2022.

- Huber, N. Ggdendroplot: Create Dendrograms for Ggplot2 2023.

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; M. Henry H. Stevens; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package 2022.

- Ghazi, F.; Kihal, M.; Altay, N.; Gürakan, G.C. Comparison of RAPD-PCR and PFGE Analysis for the Typing of Streptococcus Thermophilus Strains Isolated from Traditional Turkish Yogurts. Ann Microbiol 2016, 66, 1013–1026. [CrossRef]

- Hilton, A.C.; Mortiboy, D.; Banks, J.G.; Penn, C.W. RAPD Analysis of Environmental, Food and Clinical Isolates of Campylobacter Spp. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology 1997, 18, 119–124. [CrossRef]

- Szaluś-Jordanow, O.; Krysztopa-Grzybowska, K.; Czopowicz, M.; Moroz, A.; Mickiewicz, M.; Lutyńska, A.; Kaba, J.; Nalbert, T.; Frymus, T. MLST and RAPD Molecular Analysis of Staphylococcus Aureus Subsp. Anaerobius Isolated from Goats in Poland. Arch Microbiol 2018, 200, 1407–1410. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.; Seseña, S.; Palop, M.L. A Comparative Study of Different PCR-Based DNA Fingerprinting Techniques for Typing of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Eur Food Res Technol 2014, 239, 87–98. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.L.; Godfrey, P.A.; Stegger, M.; Andersen, P.S.; Feldgarden, M.; Frimodt-Møller, N. Selection of Unique Escherichia Coli Clones by Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD): Evaluation by Whole Genome Sequencing. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2014, 103, 101–103. [CrossRef]

- Birch, M.; Denning, D.W.; Law, D. Rapid Genotyping ofEscherichia Coli O157 Isolates by Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996, 15, 297–302. [CrossRef]

- Mölder, F.; Jablonski, K.P.; Letcher, B.; Hall, M.B.; Tomkins-Tinch, C.H.; Sochat, V.; Forster, J.; Lee, S.; Twardziok, S.O.; Kanitz, A.; et al. Sustainable Data Analysis with Snakemake 2021.

- Nanopore Technologies Guppy.

- Wick, R.; Volkening, J. Porechop 2018.

- Wick, R. Filtlong 2024.

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Cerdeira, L.T.; Hawkey, J.; Méric, G.; Vezina, B.; Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. Trycycler: Consensus Long-Read Assemblies for Bacterial Genomes. Genome Biology 2021, 22, 266. [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M.; Yuan, J.; Lin, Y.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembly of Long, Error-Prone Reads Using Repeat Graphs. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 540–546. [CrossRef]

- Raven Team Raven 2024.

- Miniasm: Ultrafast de Novo Assembly for Long Noisy Reads.

- Wick, R.R.; Holt, K.E. Benchmarking of Long-Read Assemblers for Prokaryote Whole Genome Sequencing 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Starrett, G.J.; Sappington, A.; Kostic, A.; Koren, S.; Buck, C.B.; Phillippy, A.M. Mash Screen: High-Throughput Sequence Containment Estimation for Genome Discovery. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 232. [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Treangen, T.J.; Melsted, P.; Mallonee, A.B.; Bergman, N.H.; Koren, S.; Phillippy, A.M. Mash: Fast Genome and Metagenome Distance Estimation Using MinHash. Genome Biol 2016, 17, 132. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. High-Accuracy Alignment Ensembles Enable Unbiased Assessments of Sequence Homology and Phylogeny 2022, 2021.06.20.449169. [CrossRef]

- Nanopore Technologies Medaka 2024.

- Schwengers, O.; Jelonek, L.; Dieckmann, M.A.; Beyvers, S.; Blom, J.; Goesmann, A. Bakta: Rapid and Standardized Annotation of Bacterial Genomes via Alignment-Free Sequence Identification: Find out More about Bakta, the Motivation, Challenges and Applications, Here. Microbial Genomics 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.; Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Phillippy, A.M.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Aluru, S. High Throughput ANI Analysis of 90K Prokaryotic Genomes Reveals Clear Species Boundaries. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5114. [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R.; Enns, E.; Marinier, E.; Mandal, A.; Herman, E.K.; Chen, C.; Graham, M.; Van Domselaar, G.; Stothard, P. Proksee: In-Depth Characterization and Visualization of Bacterial Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, 51, W484–W492. [CrossRef]

- Dieckmann, M.A.; Beyvers, S.; Nkouamedjo-Fankep, R.C.; Hanel, P.H.G.; Jelonek, L.; Blom, J.; Goesmann, A. EDGAR3.0: Comparative Genomics and Phylogenomics on a Scalable Infrastructure. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, W185–W192. [CrossRef]

- van Heel, A.J.; de Jong, A.; Song, C.; Viel, J.H.; Kok, J.; Kuipers, O.P. BAGEL4: A User-Friendly Web Server to Thoroughly Mine RiPPs and Bacteriocins. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, W278–W281. [CrossRef]

- Albano, H.; Oliveira, M.; Aroso, R.; Cubero, N.; Hogg, T.; Teixeira, P. Antilisterial Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from “Alheiras” (Traditional Portuguese Fermented Sausages): In Situ Assays. Meat Science 2007, 76, 796–800. [CrossRef]

- Banwo, K.; Sanni, A.; Tan, H. Functional Properties of Pediococcus Species Isolated from Traditional Fermented Cereal Gruel and Milk in Nigeria. Food Biotechnology 2013, 27, 14–38. [CrossRef]

- Garin-Murguialday, N.; Espina, L.; Virto, R.; Pagán, R. Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bacillus Subtilis as Potential Protective Cultures for Biopreservation in the Food Industry. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4016. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yang, B.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Comparative Genomics of Pediococcus Pentosaceus Isolated From Different Niches Reveals Genetic Diversity in Carbohydrate Metabolism and Immune System. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Nigatu; Ahrné; Gashe; Molin Randomly Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) for Discrimination of Pediococcus Pentosaceus and Ped. Acidilactici and Rapid Grouping of Pediococcus Isolates. Letters in Applied Microbiology 1998, 26, 412–416. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.-L.; Quednau, M.; Molin, G.; Ahrné, S. Randomly Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) for Rapid Typing of Lactobacillus Plantarum Strains. Lett Appl Microbiol 1995, 21, 155–159. [CrossRef]

- Fugaban, J.I.I.; Vazquez Bucheli, J.E.; Park, Y.J.; Suh, D.H.; Jung, E.S.; Franco, B.D.G.D.M.; Ivanova, I.V.; Holzapfel, W.H.; Todorov, S.D. Antimicrobial Properties of Pediococcus Acidilactici and Pediococcus Pentosaceus Isolated from Silage. J of Applied Microbiology 2022, 132, 311–330. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Lathrop, A. Effects of Lactobacillus Plantarum, Pediococcus Acidilactici, and Pediococcus Pentosaceus on the Growth of Listeria Monocytogenes and Salmonella on Alfalfa Sprouts. Journal of Food Protection 2019, 82, 522–527. [CrossRef]

- Santini, C.; Baffoni, L.; Gaggia, F.; Granata, M.; Gasbarri, R.; Di Gioia, D.; Biavati, B. Characterization of Probiotic Strains: An Application as Feed Additives in Poultry against Campylobacter Jejuni. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2010, 141, S98–S108. [CrossRef]

- Khorshidian, N.; Khanniri, E.; Mohammadi, M.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Yousefi, M. Antibacterial Activity of Pediocin and Pediocin-Producing Bacteria Against Listeria Monocytogenes in Meat Products. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 709959. [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, G.K.; Tiwari, S.; Kumar, A.; Raman, R.K.; Kadyan, S. Review on Factors Affecting and Control of Post-Acidification in Yoghurt and Related Products. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 109, 499–512. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Chattopadhyay, P. Application of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) as a Sensory Assessment Tool for Fermented Food Products. J Food Sci Technol 2012, 49, 328–334. [CrossRef]

- Shintani, M.; Vestergaard, G.; Milaković, M.; Kublik, S.; Smalla, K.; Schloter, M.; Udiković-Kolić, N. Integrons, Transposons and IS Elements Promote Diversification of Multidrug Resistance Plasmids and Adaptation of Their Hosts to Antibiotic Pollutants from Pharmaceutical Companies. Environmental Microbiology 2023, 25, 3035–3051. [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.E.; Maifreni, M.; Marino, M.; Bartolomeoli, I.; Carraro, L.; Fasolato, L.; Cardazzo, B. Genotypic and Phenotypic Diversity of Pediococcus Pentosaceus Strains Isolated from Food Matrices and Characterisation of the Penocin Operon. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 103, 1149–1163. [CrossRef]

- Lengeler, J.W.; Titgemeyer, F.; Vogler, A.P.; Wohrl, B.M.; Kornberg, H.L.; Henderson, P.J.F. Structures and Homologies of Carbohydrate: Phosphotransferase System (PTS) Proteins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences 1997, 326, 489–504. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Blanco, I.; José Luduverio Pizauro, L.; Victor Dos Anjos Almeida, J.; Miguel Nóbrega Mendonça, C.; De Mello Varani, A.; Pinheiro De Souza Oliveira, R. Pan-Genomic and Comparative Analysis of Pediococcus Pentosaceus Focused on the in Silico Assessment of Pediocin-like Bacteriocins. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2022, 20, 5595–5606. [CrossRef]

- Papagianni, M.; Anastasiadou, S. Pediocins: The Bacteriocins of Pediococci. Sources, Production, Properties and Applications. Microbial Cell Factories 2009, 8, 3. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.M.; Martínez, M.I.; Kok, J. Pediocin PA-1, a Wide-Spectrum Bacteriocin from Lactic Acid Bacteria. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2002, 42, 91–121. [CrossRef]

- Venema, K.; Kok, J.; Marugg, J.D.; Toonen, M.Y.; Ledeboer, A.M.; Venema, G.; Chikindas, M.L. Functional Analysis of the Pediocin Operon of Pediococcus Acidilactici PAC1.0: PedB Is the Immunity Protein and PedD Is the Precursor Processing Enzyme. Molecular Microbiology 1995, 17, 515–522. [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Fan, L.; Yan, J.; Jiang, Y.; Doucette, C.; Fillmore, S.; Walker, B. Influence of Culture Media, pH and Temperature on Growth and Bacteriocin Production of Bacteriocinogenic Lactic Acid Bacteria. AMB Express 2018, 8, 10. [CrossRef]

- Mataragas, M.; Metaxopoulos, J.; Galiotou, M.; Drosinos, E.H. Influence of pH and Temperature on Growth and Bacteriocin Production by Leuconostoc Mesenteroides L124 and Lactobacillus Curvatus L442. Meat Science 2003, 64, 265–271. [CrossRef]

- Aasen, I.M.; Møretrø, T.; Katla, T.; Axelsson, L.; Storrø, I. Influence of Complex Nutrients, Temperature and pH on Bacteriocin Production by Lactobacillus Sakei CCUG 42687. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2000, 53, 159–166. [CrossRef]

| ranking | strain | No. inhibited pathogens above average | sum | mean | p_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13.7 13A - 5 | 5 | 2.465265 | 0.3521807 | 0.20896 |

| 2 | 05.5 8 - 1 | 3 | 2.728224 | 0.3897463 | 0.79546 |

| 3 | 13.7 2A - 1 | 3 | 2.654947 | 0.3792781 | 0.06718 |

| 4 | 13.7 10 - 2 | 3 | 2.612546 | 0.3732209 | 0.05576 |

| 5 | 22.4 8A - 4 | 3 | 2.607411 | 0.3724873 | 0.33180 |

| 6 | 13.7 22A - 4 | 3 | 2.606640 | 0.3723771 | 0.07161 |

| 7 | 13.7 18A - 3 | 3 | 2.577932 | 0.3682761 | 0.59202 |

| 8 | 29.4 S1- 1 | 2 | 2.506960 | 0.3581371 | 0.42734 |

| strain | 13.7 13A–5 | 05.5 8-1 | 13.7 2A-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| genome (bp) | 1771607 | 1731150 | 1835763 |

| predicted genes | 1,816 | 1,914 | 2,332 |

| plasmids (bp) | 12,144; 12,513; 29,159 | 13,332; 20,517; 21,974; 24,254; 68,459 | 12,153; 16,367; 22,192; 36,437; 42,648; 44,253 |

| G+C content (%) | 37.14 | 37.41 | 37.11 |

| uvrA1 | 490,671 | 464,679 | 459,969 |

| polC1 | 856,007 | 806,61 | 867,588 |

| secY1 | 1,320,181 | 1,287,919 | 1,381,749 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).