Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Intratumoral microbiota, the diverse community of microorganisms residing within tumor tissues, represent an emerging and intriguing field in cancer biology. These microbial populations are distinct from the well-studied gut microbiota, offering novel insights into tumor biology, cancer progression, and potential therapeutic interventions. Recent studies have explored the use of certain antibiotics to modulate intratumoral microbiota and enhance the efficacy of cancer therapies, showing promising results. Antibiotics can alter intratumoral microbiota’s composition, which may have a major role in promoting cancer progression and immune evasion. Certain bacteria within tumors can promote immunosuppression and resistance to therapies. By targeting these bacteria, antibiotics can help create a more favorable environment for chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy to act effectively. Some bacteria within the tumor microenvironment produce immunosuppressive molecules that inhibit the activity of immune cells. The combination of antibiotics and other cancer therapies holds significant promise for creating a synergistic effect and enhancing the immune response against cancer. In this review we analyze several preclinical studies that have been conducted to demonstrate the synergy between antibiotics and other cancer therapies and discuss possible clinical implications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Synergy of Antibiotics with Chemotherapy

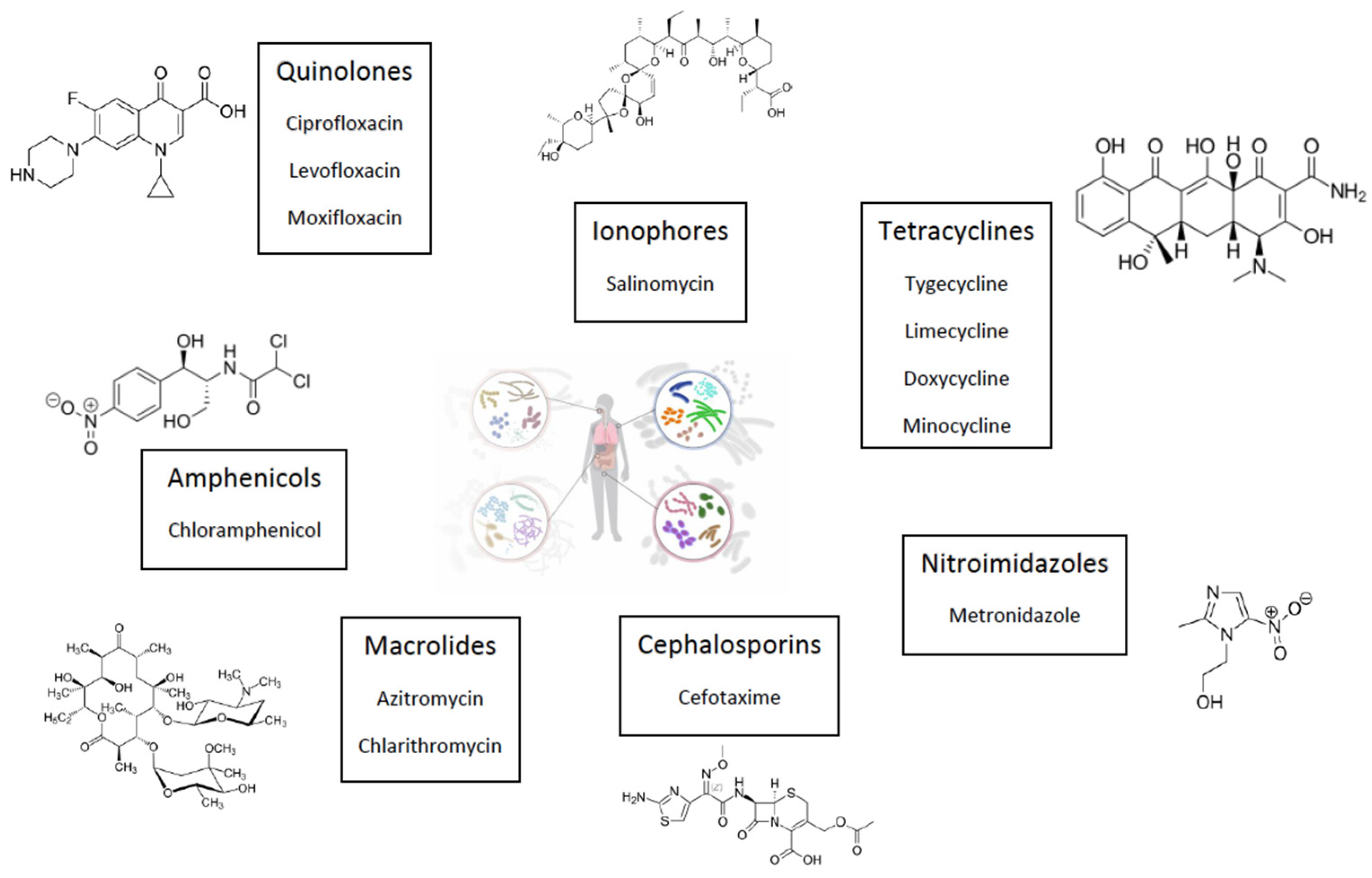

Quinolones

Tetracyclines

Macrolides

Chloramphenicol

Salinomycin

Cephalosporins

3. Synergy of Antibiotics with TKIs

4. Synergy of Antibiotics with Immunotherapy

| Chemotherapy | Targeted therapy | Immunotherapy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quinolones | Reverse MDR by altering ABCB1 expression, induce apoptosis | Delay tumor’s growth by MCM6/KIFC1 inhibition in combination with Palbociclib and improve sunitinib penetration through the blood-brain barrier | / |

| Tetracyclines | Inhibit phosforilation signaling pathways, induce autophagy/apoptosis and mitochondrial damage, inhibit EMT, MMPs and NF-kB pathway | Inhibit EGFR phosphorylation and GRB2 signaling pathway | Potentiate immune response and CAR-T cells activity by inhibiting autophagy |

| Macrolides | Induce autophagy and increase platinum sensitivity by limiting endogenous antioxidant enzyme expression and increasing the levels of ROS | Block TKIs-induced autophagy | / |

| Metronidazole | Targets Fusobacterium Nucleatum and regulates gut microbiota | / | / |

| Chloramphenicol | Induces autophagy and decrease the levels of HIF-1α, VEGF and GT-1 | / | / |

| Salinomycin | Induces ferroptosis, inhibits angiogenesis and modulates epigenetic mechanisms | / | / |

| Cephalosporines | Promote extrinsic apoptotic signaling | / | / |

5. Innovative Antibiotic Strategies

6. Clinical Trials

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, X.; et al. The Role of Intestinal Flora in Anti-Tumor Antibiotic Therapy. Front Biosci Landmark Ed 2022, 27, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, H.; et al. Efficacy of Adding Levofloxacin to Gemcitabine and Nanoparticle-Albumin-Binding Paclitaxel Combination Therapy in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Study Protocol for a Multicenter, Randomized Phase 2 Trial (T-CORE2201). BMC Cancer 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, H.; Saijo, K.; Komine, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Suzuki, A.; Ouchi, K.; Takahashi, M.; Takahashi, S.; Shirota, H.; Takahashi, M.; Ishioka, C. Antibiotics Improve the Treatment Efficacy of Oxaliplatin-Based but Not Irinotecan-Based Therapy in Advanced Colorectal Cancer Patients. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.; Mo, R.; Liao, H.; Qiu, C.; Wu, G.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, X.-J. Gut Microbiota Depletion by Antibiotics Ameliorates Somatic Neuropathic Pain Induced by Nerve Injury, Chemotherapy, and Diabetes in Mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykut, B.; et al. The Fungal Mycobiome Promotes Pancreatic Oncogenesis via Activation of MBL. Nature 2019, 574, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. H.; Wang, A.; Chu, A. N.; Gong, Y. H.; Yuan, Y. Mucosa-Associated Microbiota in Gastric Cancer Tissues Compared with Noncancer Tissues. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaora, S.; et al. Identification of Bacteria-Derived HLA-Bound Peptides in Melanoma. Nature 2021, 592, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Promotes the Development of Colorectal Cancer by Activating a Cytochrome P450/Epoxyoctadecenoic Acid Axis via TLR4/Keap1/NRF2 Signaling. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 4485–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; et al. The Microbial Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide Promotes Antitumor Immunity in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cell Metab 2022, 34, 581–594e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; et al. Influence of Intratumor Microbiome on Clinical Outcome and Immune Processes in Prostate Cancer. Cancers Basel 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuzillet, C.; et al. Prognostic Value of Intratumoral Fusobacterium Nucleatum and Association with Immune-Related Gene Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Y. Lung Microbiota Features of Stage III and IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients without Lung Infection. Transl Cancer Res 2022, 11, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, S.; et al. Profiling of Lung Microbiota Discloses Differences in Adenocarcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Sci Rep 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevcikova, A.; et al. The Impact of the Microbiome on Resistance to Cancer Treatment with Chemotherapeutic Agents and Immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, L. T.; Straussman, R. Intratumoral Bacteria May Elicit Chemoresistance by Metabolizing Anticancer Agents. Mol Cell Oncol 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; et al. Intratumoral Microbiota Impacts the First-Line Treatment Efficacy and Survival in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Free of Lung Infection. J Healthc. Eng 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; et al. Intratumoral Microbiota: A New Frontier in Cancer Development and Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejman, D.; et al. The Human Tumor Microbiome Is Composed of Tumor Type Specific Intracellular Bacteria. Science 2020, 368, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Yang; et al. Intratumoral Microbiota: Roles in Cancer Initiation, Development and Therapeutic Efficacy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M. R.; Baik, J. E.; Lagana, S. M.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Promotes Colorectal Cancer by Inducing Wnt/Beta-catenin Modulator Annexin A1. EMBO Rep 2019, 20, e47638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Su, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Promotes Colorectal Cancer Metastasis by Modulating KRT7-AS/KRT7. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casasanta, M. A.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Host-Cell Binding and Invasion Induces IL-8 and CXCL1 Secretion That Drives Colorectal Cancer Cell Migration. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayasuryan, B.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Induces Proliferation and Migration in Pancreatic Cancer Cells through Host Autocrine and Paracrine Signaling. Sci Signal 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.; et al. Intratumor Fusobacterium Nucleatum Promotes the Progression of Pancreatic Cancer via the CXCL1-CXCR2 Axis. Cancer Sci 2023, 114, 3666–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; et al. Exosomes Derived from Fusobacterium Nucleatum-Infected Colorectal Cancer Cells Facilitate Tumour Metastasis by Selectively Carrying miR-1246/92b-3p/27a-3p and CXCL16. Gut 2020, 69, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell 2017, 170, 548–563e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum-Derived Succinic Acid Induces Tumor Resistance to Immunotherapy in Colorectal Cancer. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 781–797e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, L. T.; et al. Potential Role of Intratumor Bacteria in Mediating Tumor Resistance to the Chemotherapeutic Drug Gemcitabine. Science 2017, 357, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, S.; et al. Evolved Bacterial Resistance to the Chemotherapy Gemcitabine Modulates Its Efficacy in Co-Cultured Cancer Cells. Elife 2023, 12, e83140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F. P.; et al. Escherichia Coli-Induced cGLIS3-Mediated Stress Granules Activate the NF-κB Pathway to Promote Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Progression. Adv Sci 2024, 11, 2306174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C, G.; X, W.; B, Y.; W, Y.; W, H.; G, W.; J, M. Synergistic Target of Intratumoral Microbiome and Tumor by Metronidazole-Fluorouridine Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; et al. Effects of Metronidazole on Colorectal Cancer Occurrence and Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases by Regulating Fusobacterium Nucleatum in Mice. Immun Inflamm Dis 2023, 11, e1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; et al. A Prospective, Single-Centre, Randomized, Double-Blind Controlled Study Protocol to Study Whether Long-Term Oral Metronidazole Can Effectively Reduce the Incidence of Postoperative Liver Metastasis in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Trials 2023, 24, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kd, L.; M, Z.-R.; Ag, K.; A, B.; Ss, M.; Cd, J.; S, B. The Cancer Chemotherapeutic 5-Fluorouracil Is a Potent Fusobacterium Nucleatum Inhibitor and Its Activity Is Modified by Intratumoral Microbiota. Cell Rep. 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; et al. Antibiotics for Cancer Treatment: A Double-Edged Sword. J Cancer 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeler, D. S.; et al. Ciprofloxacin and Epirubicin Synergistically Induce Apoptosis in Human Urothelial Cancer Cell Lines. Urol Int 2012, 88, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A. C.; et al. Ciprofloxacin Sensitizes Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer Cell Lines to Doxorubicin and Docetaxel Treatment on a Schedule-Dependent Manner. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2009, 64, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rayes, B. F.; et al. Ciprofloxacin Inhibits Cell Growth and Synergises the Effect of Etoposide in Hormone Resistant Prostate Cancer Cells. Int J Oncol 2002, 21, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranav Gupta; et al. Ciprofloxacin Enhances the Chemosensitivity of Cancer Cells to ABCB1 Substrates. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; et al. Moxifloxacin and Ciprofloxacin Induces S-Phase Arrest and Augments Apoptotic Effects of Cisplatin in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells via ERK Activation. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J. C.; Wang, T. J.; Chang, P. Y.; Syu, J. J.; Chen, J. C.; Chen, C. Y.; Jian, Y. T.; Jian, Y. J.; Zheng, H. Y.; Chen, W. C.; Lin, Y. W. Minocycline Enhances Mitomycin C-Induced Cytotoxicity through down-Regulating ERK1/2-Mediated Rad51 Expression in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2015, 97, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danko, T.; et al. Rapamycin plus Doxycycline Combination Affects Growth Arrest and Selective Autophagy-Dependent Cell Death in Breast Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F. Y.; Wu, Y. H.; Zhou, S. J.; Deng, Y. L.; Zhang, Z. Y.; Zhang, E. L.; Huang, Z. Y. Minocycline and Cisplatin Exert Synergistic Growth Suppression on Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Inducing S Phase Arrest and Apoptosis. Oncol Rep 2014, 32, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloskowski, T.; et al. Ciprofloxacin and Levofloxacin as Potential Drugs in Genitourinary Cancer Treatment—The Effect of Dose–Response on 2D and 3D Cell Cultures. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoor, M.; et al. Superficial Bladder Tumours: Recurrence and Progression. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2011, 21, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jaber, D. F.; et al. The Effect of Ciprofloxacin on the Growth of B16F10 Melanoma Cells. J Cancer Res Ther 2017, 13, 956–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beberok, A.; et al. Ciprofloxacin Triggers the Apoptosis of Human Triple-Negative Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells via the P53/Bax/Bcl-2 Signaling Pathway. Int J Oncol 2018, 52, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengtian Fan; et al. Ciprofloxacin Promotes Polarization of CD86+/CD206- Macrophages to Suppress Liver Cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 44, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; et al. Efficacy of Adding Levofloxacin to Gemcitabine and Nanoparticle-Albumin-Binding Paclitaxel Combination Therapy in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Study Protocol for a Multicenter, Randomized Phase 2 Trial (T-CORE2201). BMC Cancer 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Yang, Q.; Xu, W.; Jiang, S.; Han, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhang, S. Inhibition of Autophagy Enhances the Antitumour Activity of Tigecycline in Multiple Myeloma. J Cell Mol Med 2018, 22, 5955–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaaeldin, R.; et al. Modulation of Apoptosis and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition E-Cadherin/TGF-β/Snail/TWIST Pathways by a New Ciprofloxacine Chalcone in Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 2383–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Yang, Q.; Xu, W.; Jiang, S.; Han, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhang, S. Inhibition of Autophagy Enhances the Antitumour Activity of Tigecycline in Multiple Myeloma. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 5955–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Yang, L.; Jiang, X.; Xu, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Xiang, Z.; Cui, H. Antibiotic Drug Tigecycline Inhibited Cell Proliferation and Induced Autophagy in Gastric Cancer Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Gu, Z.; Chen, W.; Jiao, J. Tigecycline Targets Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer through Inhibition of Mitochondrial Function. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 30, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Dong, Z.; Ren, A.; Fu, G.; Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Cui, H. Antibiotic Tigecycline Inhibits Cell Proliferation, Migration and Invasion via down-Regulating CCNE2 in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 4245–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X, J.; Z, G.; W, C.; J, J. Tigecycline Targets Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer through Inhibition of Mitochondrial Function. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendramin, R.; Katopodi, V.; Cinque, S.; Konnova, A.; Knezevic, Z.; Adnane, S.; Verheyden, Y.; Karras, P.; Demesmaeker, E.; Bosisio, F. M.; Kucera, L.; Rozman, J.; Gladwyn-Ng, I.; Rizzotto, L.; Dassi, E.; Millevoi, S.; Bechter, O.; Marine, J.-C.; Leucci, E. Activation of the Integrated Stress Response Confers Vulnerability to Mitoribosome-Targeting Antibiotics in Melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B, H.; Y, G. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Translation as a Therapeutic Strategy for Human Ovarian Cancer to Overcome Chemoresistance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Song, M.; Zhou, M.; Hu, Y. Antibiotic Tigecycline Enhances Cisplatin Activity against Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Inducing Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Damage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, F.; Vlashi, E. Doxycycline Inhibits the Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Breast Cancer. Cell Cycle Georget. Tex 2017, 16, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al, L.; B, S.; Ni, L.; Al, E.; Y, B.; M, V.; Pn, H.; Jp, S.; Mw, R. Doxycycline Impairs Mitochondrial Function and Protects Human Glioma Cells from Hypoxia-Induced Cell Death: Implications of Using Tet-Inducible Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C. C.; Lo, M. C.; Moody, R. R.; Stevers, N. O.; Tinsley, S. L.; Sun, D. Doxycycline Targets Aldehyde Dehydrogenase-Positive Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 3041–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scatena, C.; Lisanti, M. P.; Naccarato, A. G.; et al. Doxycycline, an Inhibitor of Mitochondrial Biogenesis, Effectively Reduces Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in Early Breast Cancer Patients: A Clinical Pilot Study. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; et al. Doxycycline Reverses Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Suppresses the Proliferation and Metastasis of Lung Cancer Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 40667–40679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. F.; Yang, Y. N.; Chu, H. R.; Huang, T. Y.; Wang, S. H.; Chen, H. Y.; Li, Z. L.; Yang, Y. S. H.; Lin, H. Y.; Hercbergs, A.; Whang-Peng, J.; Wang, K.; Davis, P. J. Role of Integrin Avβ3 in Doxycycline-Induced Anti-Proliferation in Breast Cancer Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 829788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, R.; Macha, M. A.; Rachagani, S.; Das, S.; Smith, L. M.; Kaur, S.; Batra, S. K. Axed MUC4 (MUC4/X) Aggravates Pancreatic Malignant Phenotype by Activating Integrin-Β1/FAK/ERK Pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 2538–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhao, N.; Ni, C. S.; Zhao, X. L.; Zhang, W. Z.; Su, X.; Zhang, D. F.; Gu, Q.; Sun, B. C. Doxycycline Inhibits the Adhesion and Migration of Melanoma Cells by Inhibiting the Expression and Phosphorylation of Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK). Cancer Lett. 2009, 285, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; et al. Doxycycline Inhibits Cancer Stem Cell-like Properties via PAR1/FAK/PI3K/AKT Pathway in Pancreatic Cancer. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 619317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ao, J.; Yu, D.; Rao, T.; Ruan, Y.; Yao, X. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Translation Effectively Sensitizes Renal Cell Carcinoma to Chemotherapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 490, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Targeting the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2020, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiao, S.; Li, X.; Banu, H.; Hamal, S.; Wang, X. Therapeutic Effects of Antibiotic Drug Tigecycline against Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Inhibiting Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015, 467, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Yu, C.; Li, F.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Ye, L. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Cancers and Targeted Therapies. Signal Transduct Target. Ther 2021, 6, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Tan, L.; Yin, Z.; Zhu, W.; Tao, K.; Wang, G.; Shi, W.; Gao, J. MIR17HG-miR-18a/19a Axis, Regulated by Interferon Regulatory Factor-1, Promotes Gastric Cancer Metastasis via Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xiao, T.; Qin, Y.; Gu, J.; Sun, B.; Liu, Y.; Jing, X.; Hu, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, H.; Sun, T.; Yang, C. Doxycycline Directly Targets PAR1 to Suppress Tumor Progression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 16829–16842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Wu, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, L.; Zhou, J. Effect of the Notch1-Mediated PI3K-Akt-mTOR Pathway in Human Osteosarcoma. Aging 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, J.; Dittmar, T. Minocycline Impairs TNF-α-Induced Cell Fusion of M13SV1-Cre Cells with MDA-MB-435-pFDR1 Cells by Suppressing NF-κB Transcriptional Activity and Its Induction of Target-Gene Expression of Fusion-Relevant Factors. Cell Commun Signal 2019, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataie-Kachoie, P.; Badar, S.; Morris, D. L.; Pourgholami, M. H. Minocycline Targets the NF-κB Nexus through Suppression of TGF-Β1-TAK1-IκB Signaling in Ovarian Cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2013, 11, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. C.; Liu, J.; Baglo, Y.; Rizvi, I.; Anbil, S.; Pigula, M.; Hasan, T. Mechanism-Informed Repurposing of Minocycline Overcomes Resistance to Topoisomerase Inhibition for Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhunzianov, A. A.; et al. Unravelling the Therapeutic Potential of Antibiotics in Hypoxia in a Breast Cancer MCF-7 Cell Line Model. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 11540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, K.; Moriya, S.; Miyahara, K.; et al. Macrolide Antibiotics Exhibit Cytotoxic Effect under Amino Acid-Depleted Culture Condition by Blocking Autophagy Flux in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Lines. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, S.; Ito, K.; Yamashiro, Y.; et al. EGFR-Independent Autophagy Induction with Gefitinib and Enhancement of Its Cytotoxic Effect by Targeting Autophagy with Clarithromycin in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015, 461, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toriyama, K.; et al. In Vitro Anticancer Effect of Azithromycin Targeting Hypoxic Lung Cancer Cells via the Inhibition of Mitophagy. Oncol. Lett. 2024, 27, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukai, S.; Moriya, S.; Hiramoto, M.; et al. Macrolides Sensitize EGFR-TKI-Induced Non-Apoptotic Cell Death via Blocking Autophagy Flux in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines. Int J Oncol 2016, 48, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B. Clarithromycin Synergizes with Cisplatin to Inhibit Ovarian Cancer Growth in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H. L.; et al. Chloramphenicol Induces Autophagy and Inhibits the Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 Alpha Pathway in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, K.; et al. Induction of Glioblastoma Cell Ferroptosis Using Combined Treatment with Chloramphenicol and 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; et al. Salinomycin Triggers Prostate Cancer Cell Apoptosis by Inducing Oxidative and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress via Suppressing Nrf2 Signaling. Exp Ther Med 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; et al. Salinomycin Effectively Eliminates Cancer Stem-like Cells and Obviates Hepatic Metastasis in Uveal Melanoma. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daimon, T.; et al. MUC1-C Is a Target of Salinomycin in Inducing Ferroptosis of Cancer Stem Cells. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, J.; et al. Salinomycin Inhibits Breast Cancer Progression via Targeting HIF1a/VEGF-Mediated Tumor Angiogenesis in Vitro and in Vivo. Biochem Pharmacol 2019, 164, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. K.; et al. Salinomycin Inhibits Epigenetic Modulator EZH2 to Enhance Death Receptors in Colon Cancer Stem Cells. Epigenetics 2021, 16, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X. Combination of Cefotaxime and Cisplatin Specifically and Selectively Enhances Anticancer Efficacy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2023, 23, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; et al. Comparison of Autophagy Inducibility in Various Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Their Enhanced Cytotoxicity via Inhibition of Autophagy in Cancer Cells in Combined Treatment with Azithromycin. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2020, 22, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kast, R. E.; et al. OPALS: A New Osimertinib Adjunctive Treatment of Lung Adenocarcinoma or Glioblastoma Using Five Repurposed Drugs. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, T.; et al. Assessment of Azithromycin as an Anticancer Agent for Treatment of Imatinib Sensitive and Resistant CML Cells. Leuk Res 2021, 102, 106523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Lymecycline Reverses Acquired EGFR-TKI Resistance in Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer by Targeting GRB2. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159, 10500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkov, O.; Manko, N.; Bilous, S.; Didikin, G.; Klyuchivska, O.; Dilay, N.; Stoika, R. Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activity of Metronidazole and Levofloxacin Composites with Silver Nanoparticle. Curr Issues Pharm Med Sci 2021, 34, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, S.; et al. Macrolide Antibiotics Block Autophagy Flux and Sensitize to Bortezomib via Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated CHOP Induction in Myeloma Cells. Int J Oncol 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kositza, J.; et al. Identification of the KIF and MCM Protein Families as Novel Targets for Combination Therapy with CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Bladder Cancer. Urol Oncol 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalek, E.; et al. The Penetration of Sunitinib through the Blood-Brain Barrier after the Administration of Ciprofloxacin. Acta Pol Pharm 2014, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.-Y.; et al. Doxycycline Inducible Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Targeting CD147 for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019, 7, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; et al. Nanodrug Inducing Autophagy Inhibition and Mitochondria Dysfunction for Potentiating Tumor Photo-Immunotherapy. Small 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, Y.; et al. Tetracyclines Enhance Anti-Tumor T-Cell Responses Induced by a Bispecific T-Cell Engager. Biol Pharm Bull 2022, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padma, S.; Patra, R.; Sen Gupta, P. S.; Panda, S. K.; Rana, M. K.; Mukherjee, S. Cell Surface Fibroblast Activation Protein-2 (Fap2) of Fusobacterium Nucleatum as a Vaccine Candidate for Therapeutic Intervention of Human Colorectal Cancer: An Immunoinformatics Approach. Vaccines 2023, 11, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y.; et al. Tubeimuside I Improves the Efficacy of a Therapeutic Fusobacterium Nucleatum Dendritic Cell-Based Vaccine against Colorectal Cancer. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1154818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Rehman, A.; Rehman, L.; Darbaniyan, F.; Blumenberg, V.; Schubert, M.-L.; Mor, U.; Zamir, E.; Schmidt, S.; Hayase, T.; Chia-Chi, C.; McDaniel, L. K.; Flores, I.; Strati, P.; Nair, R.; Chihara, D.; Fayad, L. E.; Ahmed, S.; Iyer, S. P.; Wang, M. L.; Jain, P.; Nastoupil, L. J.; Westin, J. R.; Arora, R.; Turner, J. G.; Khawaja, F.; Wu, R.; Dennison, J. B.; Menges, M.; Hidalgo-Vargas, M.; Reid, K. M.; Davila, M. L.; Dreger, P.; Korell, F.; Schmitt, A.; Tanner, M. R.; Champlin, R. E.; Flowers, C. R.; Shpall, E. J.; Hanash, S.; Neelapu, S. S.; Schmitt, M.; Subklewe, M.; Fahrmann, J.; Stein-Thoeringer, C.; Elinav, E.; Jain, M. D.; Hayase, E.; Jenq, R. R.; Saini, N. Y. Antibiotic-Induced Loss of Gut Microbiome Metabolic Output Correlates with Clinical Responses to CAR T-Cell Therapy. Blood 2024, blood.2024025366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, P.; Albarrán, V.; González-Merino, C.; García de Quevedo, C.; Sotoca, P.; Chamorro, J.; Rosero, D. I.; Barrill, A.; Alía, V.; Calvo, J. C.; Moreno, J.; Pérez de Aguado, P.; Álvarez-Ballesteros, P.; San Román, M.; Serrano, J. J.; Soria, A.; Olmedo, M. E.; Saavedra, C.; Cortés, A.; Gómez, A.; Lage, Y.; Ruiz, Á.; Ferreiro, M. R.; Longo, F.; Guerra, E.; Martínez-Delfrade, Í.; Garrido, P.; Gajate, P. Detrimental Effect of an Early Exposure to Antibiotics on the Outcomes of Immunotherapy in a Multi-Tumor Cohort of Patients. The Oncologist 2024, oyae284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J. L.; et al. Electro-Antibacterial Therapy (EAT) to Enhance Intracellular Bacteria Clearance in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Bioelectrochemistry 2024, 157, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlamani, R. A.; Dhanabal, A.; Detwiler, D. A.; Pal, R.; McCarthy, J.; Seleem, M. N.; Garner, A. L. Nanosecond Electric Pulses Rapidly Enhance the Inactivation of Gram-Negative Bacteria Using Gram-Positive Antibiotics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 2217–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlamani, A.; Detwiler, D. A.; Dhanabal, A.; Garner, A. L. Synergistic Bacterial Inactivation by Combining Antibiotics with Nanosecond Electric Pulses. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 102, 7589–7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovsin, Z.; Klancnik, A.; Kotnik, T. Electroporation as an Efficacy Potentiator for Antibiotics with Different Target Sites. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.; et al. Three-in-One Peptide Prodrug with Targeting, Assembly and Release Properties for Overcoming Bacterium-Induced Drug Resistance and Potentiating Anti-Cancer Immune Response. Adv Mater 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; et al. Dual Gate-Controlled Therapeutics for Overcoming Bacterium-Induced Drug Resistance and Potentiating Cancer Immunotherapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; et al. Transforming Intratumor Bacteria into Immunopotentiators to Reverse Cold Tumors for Enhanced Immune-Chemodynamic Therapy of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; et al. Lipid Prodrug Nanoassemblies via Dynamic Covalent Boronates. ACS Nano 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Yuan, W.; Huang, W.; Wu, G.; Ma, J. Synergistic Target of Intratumoral Microbiome and Tumor by Metronidazole–Fluorouridine Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 7335–7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; et al. Size-Tunable Nanogels for Cascaded Release of Metronidazole and Chemotherapeutic Agents to Combat Fusobacterium Nucleatum-Infected Colorectal Cancer. J Control Release 2024, 365, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; et al. Salinomycin-Loaded Gold Nanoparticles for Treating Cancer Stem Cells by Ferroptosis-Induced Cell Death. Mol Pharm 2019, 16, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; et al. Polymeric Micellar Formulation Enhances Antimicrobial and Anticancer Properties of Salinomycin. Pharm Res 2019, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. Salinomycin-Loaded Small-Molecule Nanoprodrugs Enhance Anticancer Activity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Nanomed 2020, 15, 6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak, G.; et al. Salinomycin Encapsulated PLGA Nanoparticles Eliminate Osteosarcoma Cells via Inducing/Inhibiting Multiple Signaling Pathways: Comparison with Free Salinomycin. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2020, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Enhanced and Prolonged Antitumor Effect of Salinomycin-Loaded Gelatinase-Responsive Nanoparticles via Targeted Drug Delivery and Inhibition of Cervical Cancer Stem Cells. Int J Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanchan, S.; et al. Nanocarrier-Mediated Salinomycin Delivery Induces Apoptosis and Alters EMT Phenomenon in Prostate Adenocarcinoma. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandooren, J.; et al. Differential Inhibition of Activity, Activation and Gene Expression of MMP-9 in THP-1 Cells by Azithromycin and Minocycline versus Bortezomib: A Comparative Study. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zyro, D.; et al. Multifunctional Silver(I) Complexes with Metronidazole Drug Reveal Antimicrobial Properties and Antitumor Activity against Human Hepatoma and Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Cancers 2022, 14, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyro, D.; et al. Pro-Apoptotic and Genotoxic Properties of Silver(I) Complexes of Metronidazole and 4-Hydroxymethylpyridine against Pancreatic Cancer Cells In Vitro. Cancers 2020, 12, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowska-Lis, U.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Water-Soluble Silver(I) Complexes of Metronidazole Drug and Selected Counter-Ions. Dalton Trans 2015, 44, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radko, L.; et al. Silver(I) Complexes of the Pharmaceutical Agents Metronidazole and 4-Hydroxymethylpyridine: Comparison of Cytotoxic Profile for Potential Clinical Application. Molecules 2019, 24, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryjska, K.; et al. Synthesis, Spectroscopy, Single-Crystal Structure Analysis and Antibacterial Activity of Two Novel Complexes of Silver(I) with Miconazole Drug. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabijanska, M.; et al. Silver Complexes of Miconazole and Metronidazole: Potential Candidates for Melanoma Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ude, Z.; et al. A Novel Dual-Functioning Ruthenium (II)-Arene Complex of an Anti-Microbial Ciprofloxacin Derivative - Anti-Proliferative and Anti-Microbial Activity. J Inorg Biochem 2016, 160, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitew Alem, M. B.; et al. Cytotoxic Mixed-Ligand Complexes of Cu (II): A Combined Experimental and Computational Study. Front Chem 2022, 10, 1028957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-H.; Jeng, J.-H.; Wang, Y.-J.; Tseng, C.-J.; Liang, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-H.; Lee, H.-M.; Lin, J.-K.; Lin, C.-H.; Lin, S.-Y.; et al. Antitumor Effects of Miconazole on Human Colon Carcinoma Xenografts in Nude Mice through Induction of Apoptosis and G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2002, 180, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H. J.; Seo, I.; Jha, B. K.; Suh, S. I.; Baek, W. K. Miconazole Induces Autophagic Death in Glioblastoma Cells via Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Oncol Lett 2021, 21, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Shiau, M.; Ou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Cheng, C.; Chiu, K.; Wang, S.; Tsai, K. Miconazole Induces Apoptosis via the Death Receptor 5-Dependent and Mitochondrial-Mediated Pathways in Human Bladder Cancer Cells. Oncol Rep 201AD, 37, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, L.; et al. Anti-Fungal Drug Itraconazole Exerts Anti-Cancer Effects in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma via Suppressing Hedgehog Pathway. Life Sci 2020, 254, 117695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; et al. Itraconazole Inhibits the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway Thereby Inducing Autophagy-Mediated Apoptosis of Colon Cancer Cells. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; et al. Anti-Proliferation of Breast Cancer Cells with Itraconazole: Hedgehog Pathway Inhibition Induces Apoptosis and Autophagic Cell Death. Cancer Lett 2017, 385, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S.; et al. Dichloroacetate Inhibits Neuroblastoma Growth by Specifically Acting against Malignant Undifferentiated Cells. Int J Cancer 2012, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, R.; Lisanti, M. P.; et al. Antibiotics That Target Mitochondria Effectively Eradicate Cancer Stem Cells, across Multiple Tumor Types: Treating Cancer like an Infectious Disease. Oncotarget 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, M.; Lisanti, M. P.; et al. Repurposing Atovaquone: Targeting Mitochondrial Complex III and OXPHOS to Eradicate Cancer Stem Cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Francesco, E. M.; Lisanti, M. P.; et al. Vitamin C and Doxycycline: A Synthetic Lethal Combination Therapy Targeting Metabolic Flexibility in Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs). Oncotarget 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorillo, M.; Lisanti, M. P.; et al. Doxycycline, Azithromycin and Vitamin C (DAV): A Potent Combination Therapy for Targeting Mitochondria and Eradicating Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs). Aging 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NCT Number | Title | Conditions | Country_PI | Drug_INN | PhaseCode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChiCTR2000029245 | The efficacy and safety of the combination of transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation with metronidazole in hepatocellular carcinoma | Hepatocellular carcinoma | China | Metronidazole | Other |

| ChiCTR1800014946 | Thalidomide, Clarithromycin and Dexamethasone Regimen for Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma | Multiple Myeloma | China | Clarithromycin | Other |

| ChiCTR-IOR-17010695 | The significance of minimal residual disease exmination on the multiple myeloma maintain treatment | Multiple myeloma | China | Clarithromycin | Other |

| ACTRN12620000815965 | Phase II Trial of Doxycycline with Radiotherapy for Rectal Cancer | Rectal Cancer;Cancer - Bowel - Back passage (rectum) or large bowel (colon) | New Zealand | Doxycycline | Phase 2 |

| NCT05462496 | Modulation of the Gut Microbiome With Pembrolizumab Following Chemotherapy in Resectable Pancreatic Cancer | Pancreatic Cancer | United States | CiprofloxacinMetronidazole | Phase 2 |

| NCT04523987 | A Pilot Study of Ciprofloxacin Plus Gemcitabine and Nab-Paclitaxel Chemotherapy in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. | Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | Singapore | Ciprofloxacin | Phase 1 |

| NCT02387203 | Antibiotic Treatment and Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Pseudomyxoma Peritonei of Appendiceal Origin | Pseudomyxoma Peritonei|Appendiceal Neoplasms | United States | Clarithromycin | Phase 2 |

| NCT01745588 | Autologous Stem Cell Transplant With Pomalidomide (CC-4047®) Maintenance Versus Continuous Clarithromycin/ Pomalidomide / Dexamethasone Salvage Therapy in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma | Multiple Myeloma | United States | Clarithromycin | Phase 2 |

| NCT04302324 | A Phase II Study of Daratumumab, Clarithromycin, Pomalidomide And Dexamethasone (D-ClaPd) In Multiple Myeloma Patients Previously Exposed to Daratumumab | Multiple Myeloma|Refractory Multiple Myeloma|Relapse Multiple Myeloma | United States | Clarithromycin | Phase 2 |

| NCT02542657 | Ixazomib With Pomalidomide, Clarithromycin and Dexamethasone in Treating Patients With Multiple Myeloma | Myeloma | United States | Clarithromycin | Phase 1/2 |

| NCT04287660 | Study of BiRd Regimen Combined With BCMA CAR T-cell Therapy in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (MM) Patients | Multiple Myeloma | China | Clarithromycin | Phase 3 |

| NCT01559935 | Carfilzomib, Clarithromycin (Biaxin®), Lenalidomide (Revlimid®), and Dexamethasone (Decadron®) [Car-BiRD] Therapy for Subjects With Multiple Myeloma | Multiple Myeloma | United States | Clarithromycin | Phase 2 |

| NCT02343042 | Selinexor and Backbone Treatments of Multiple Myeloma Patients | Multiple Myeloma | United States | Clarithromycin | Phase 1/2 |

| NCT03031483 | Clarithromycin + Lenalidomide Combination: a Full Oral Treatment for Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma | Mucosa Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma | Italy | Clarithromycin | Phase 2 |

| NCT02875223 | A Safety and Efficacy Study of CC-90011 in Participants With Relapsed and/or Refractory Solid Tumors and Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas | Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin|Neoplasms | France | ItraconazoleRifampicin | Phase 1 |

| NCT03076281 | Metformin Hydrochloride and Doxycycline in Treating Patients With Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma That Can Be Removed by Surgery | Larynx|LIP|Oral Cavity|Pharynx | United States | Doxycycline | Phase 2 |

| NCT01820910 | Phase II Trial of First-line Doxycycline for Ocular Adnexal Marginal Zone Lymphoma Treatment | Marginal Zone Lymphoma of Ocular Adnexal | United States | Doxycycline | Phase 2 |

| NCT03116659 | CTCL Directed Therapy | Lymphoma, T-Cell, Cutaneous | United States | Doxycycline | Phase 1 |

| NCT04264676 | Study of Oral Metronidazole on Postoperative Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer | Colorectal Cancer Stage II|Colorectal Cancer Stage III | China | Metronidazole | Phase 1 |

| NCT05720559 | Early Blocking Strategy for Metachronous Liver Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer Based on Pre-hepatic CTC Detection | Preventive Effect of Quintuple Therapy on Metachronous Liver Metastases in Patients With Colorectal Cancer | China | Metronidazole | Phase 2 |

| NCT05774964 | Quintuple Method for Treatment of Multiple Refractory Colorectal Liver Metastases | For Patients With Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases Who Were Not Able to Curative Surgical Resection.Focused on the Treatment Effect With the Quintuple Method | China | Metronidazole | Phase 2 |

| NCT06126731 | Combination Study of Antibiotics With Enzalutamide (PROMIZE) | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC) | United Kingdom | CiprofloxacinMetronidazole | Phase 1/2 |

| 2020-003152-33 | A phase II trial of long-term intravenous treatment with bi-weekly Azithromycin in patients with gastric lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT-lymphoma) | gastric MALT Lymphoma | Austria | Azithromycin | Phase 2 |

| 2019-004074-25 | A Phase II Open-Label Randomized COntrolled Pre-Surgical Feasibility Study of Antibiotic COmbinations in Early Breast Cancer | We investigated, in a population of patients with breast cancer, the combined effect of azithrocyn, docyciclin and vitamin C on biomarkers associated with cell proliferation | Italy | Azithromycin | Phase 2 |

| 2016-000871-26 | Studio di Fase II, randomizzato, in aperto, controllato di fattibilit¿ dell¿impiego di doxiciclina nel tumore mammario in stadio precoce | Breast cancer - Stage 1-2 to or Stage 3 that is candidate for primary surgery | Italy | Doxycycline | Phase 2 |

| ChiCTR2100047608 | Clarithromycin added to pomadomide-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone (Cla-PCd) versus pomadomide cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone (PCd) in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a prospective, multicentre, randomised, controlled clinical trial | Multiple Myeloma | China | Clarithromycin | Phase 4 |

| ChiCTR2100046201 | A prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled study on whether long-term oral antibiotics can effectively reduce the incidence of postoperative tumor recurrence and metastasis in patients with colorectal cancer | colorectal cancer | China | Metronidazole | Not available/Missing |

| RPCEC00000367 | Doxycycline for prostate cancer | Prostate cancer;Prostatic Neoplasms;Genital Neoplasms, Male;Urogenital Neoplasms ;Prostatic Diseases;Genital Diseases, Male ;Male Urogenital Diseases | Mexico | Doxycycline | Phase 2 |

| ChiCTR2100054650 | A phase II clinical study evaluating the efficacy and safety of Fruquintinib combined with azithromycin liposome in patients with Platinum resistant ovarian cancer | Ovarian cancer | China | Azithromycin | Phase 4 |

| JPRN-jRCTs021230005 | A randomized phase 2 study assessing the efficacy and safety of levofloxacin added to the GEM/nabPTX combination therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer(T-CORE2201) | pancretic cancer | Japan | Levofloxacin | Phase 2 |

| ACTRN12623001164684 | Assessing treatment effectiveness of the 'Repurposing-Drugs-in-Oncology' (ReDO) protocol for cancer: The ReDO cancer treatment study | Cancer; <br>Cancer;Cancer - Any cancer | Australia | Doxycycline | Other |

| NCT02874430 | Metformin Hydrochloride and Doxycycline in Treating Patients With Localized Breast or Uterine Cancer | Breast Carcinoma, Endometrial Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma, Endometrial Serous Adenocarcinoma, Uterine Corpus Cancer, Uterine Corpus Carcinosarcoma | United States | Doxycycline | Phase 2 |

| NCT04063189 | Clinical Trial of Clarithromycin, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone in the Treatment of the First Relapsed Multiple Myeloma | Multiple Myeloma in Relapse | China | Clarithromycin | Phase 2 |

| NCT02575144 | GEM-CLARIDEX: Ld vs BiRd | Multiple Myeloma | Spain | Clarithromycin | Phase 3 |

| NCT03962920 | Personalized Treatment of Urogenital Cancers Depends on the Microbiome | Microbial Disease | Denmark | Tigecycline | Other |

| NCT06452394 | NEODOXy: Targeting Breast Cancer Stem Cells With Doxycycline | Breast Cancer | Switzerland | Doxycycline | Phase 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).