Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

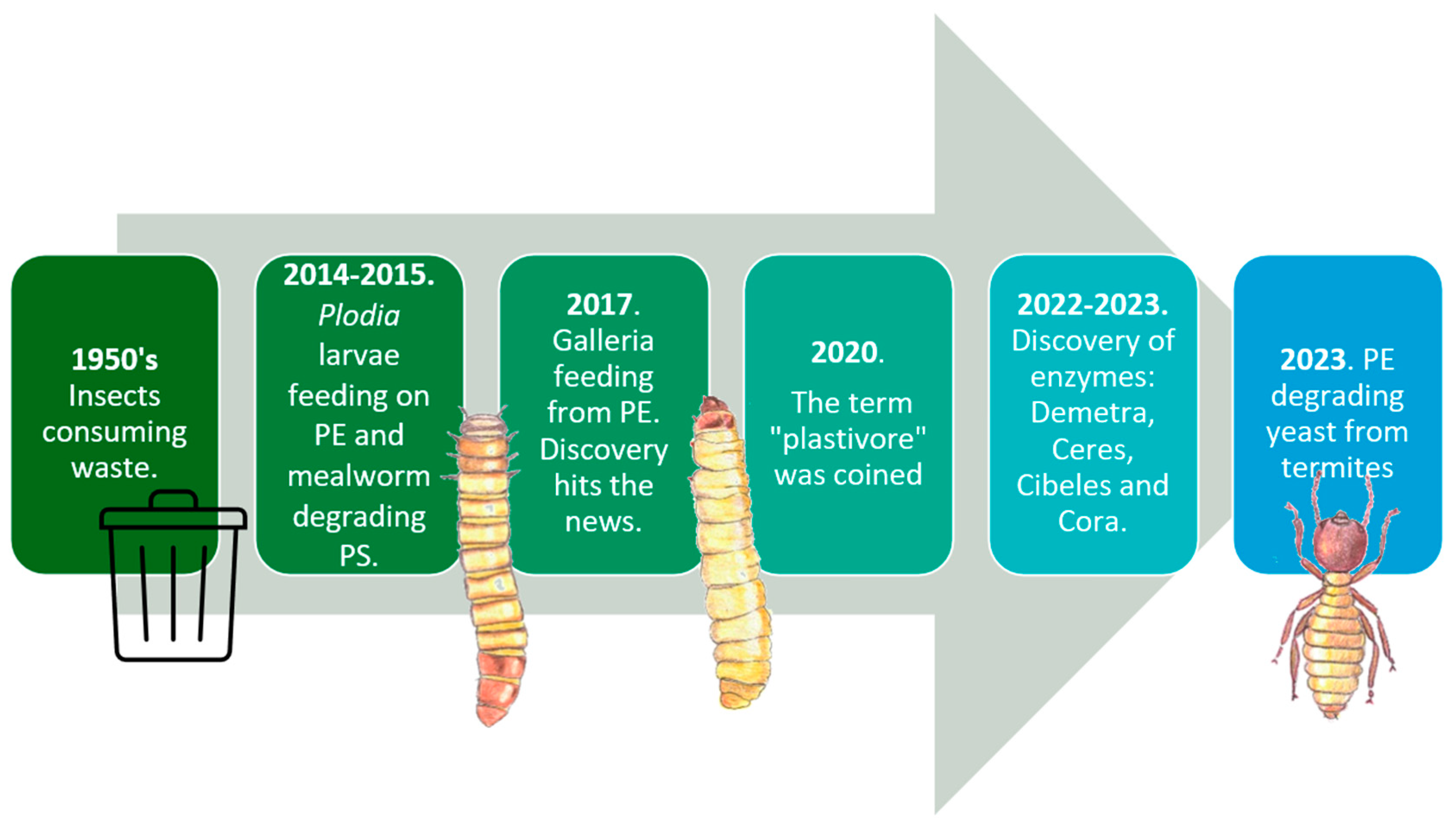

1. Introduction

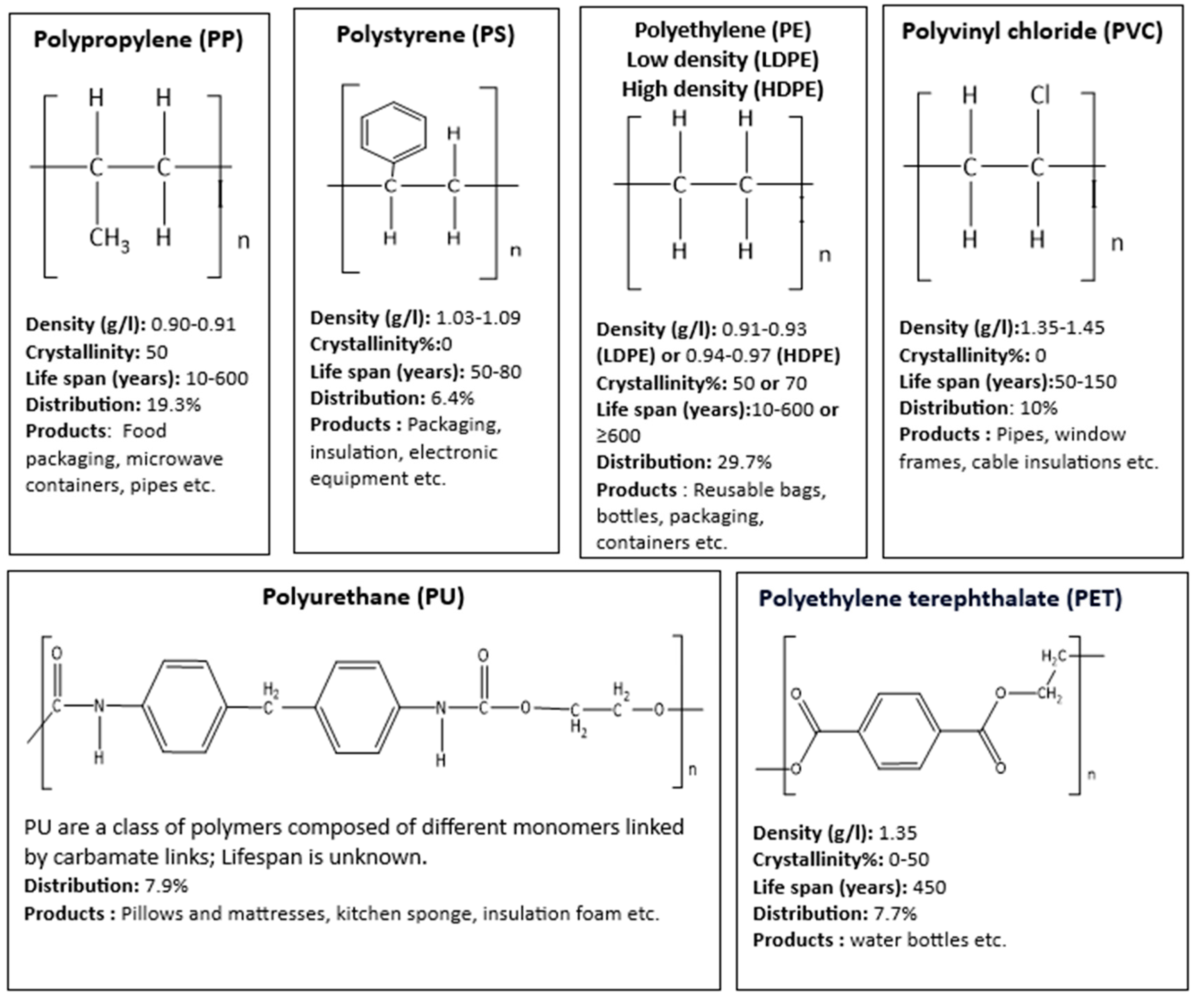

2. Plastic Pollution

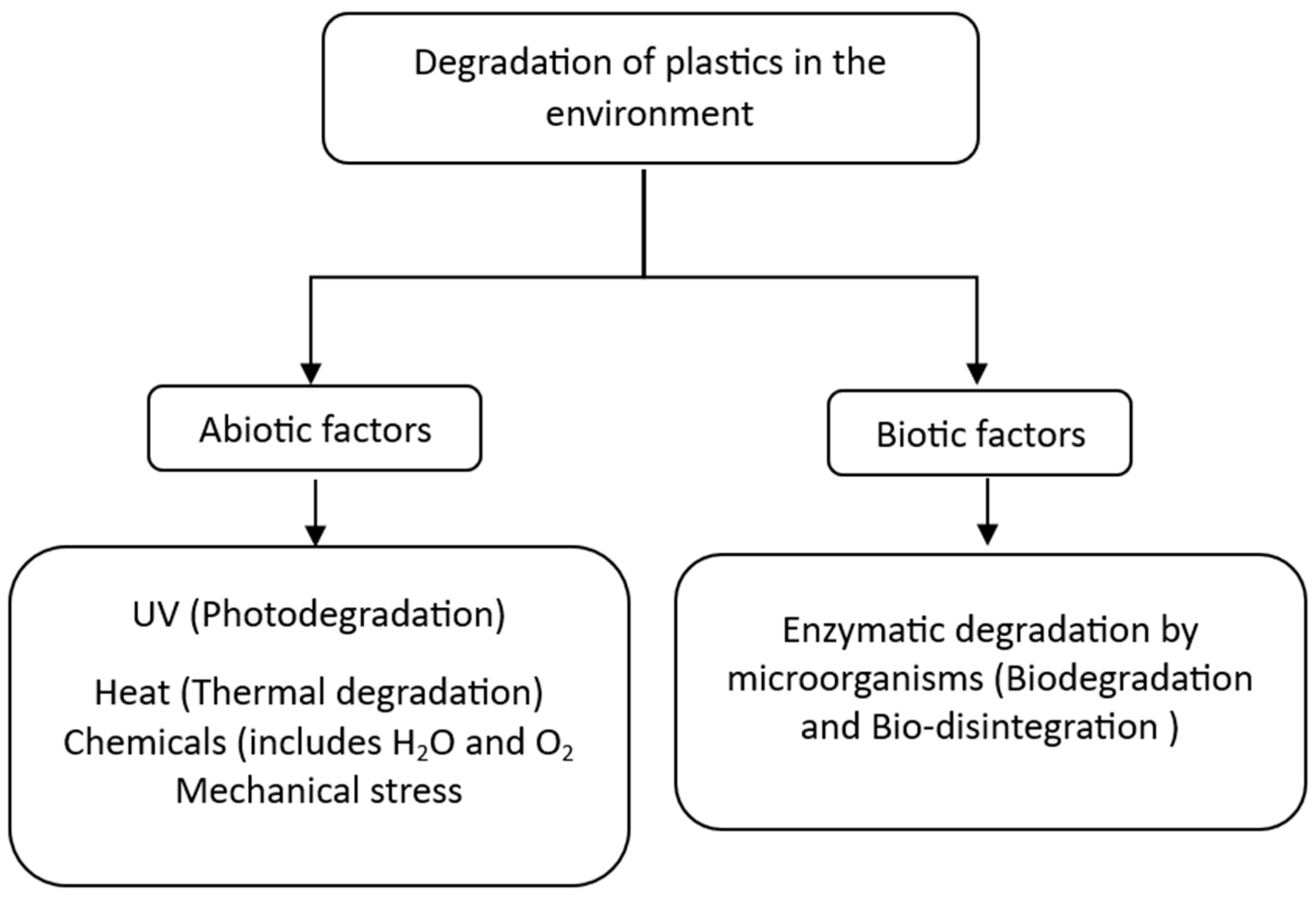

3. Degradation of Plastics-A General Perspective

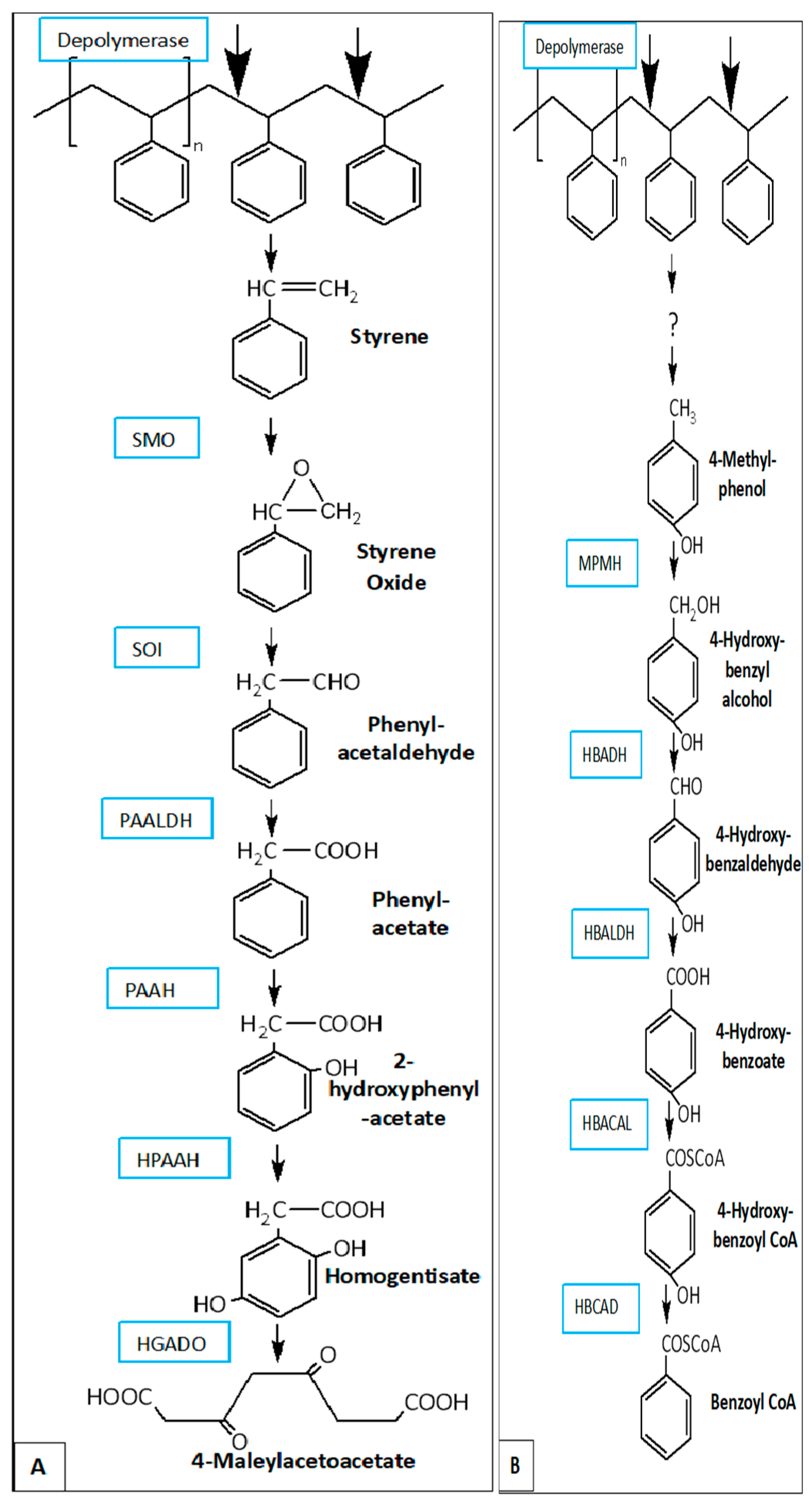

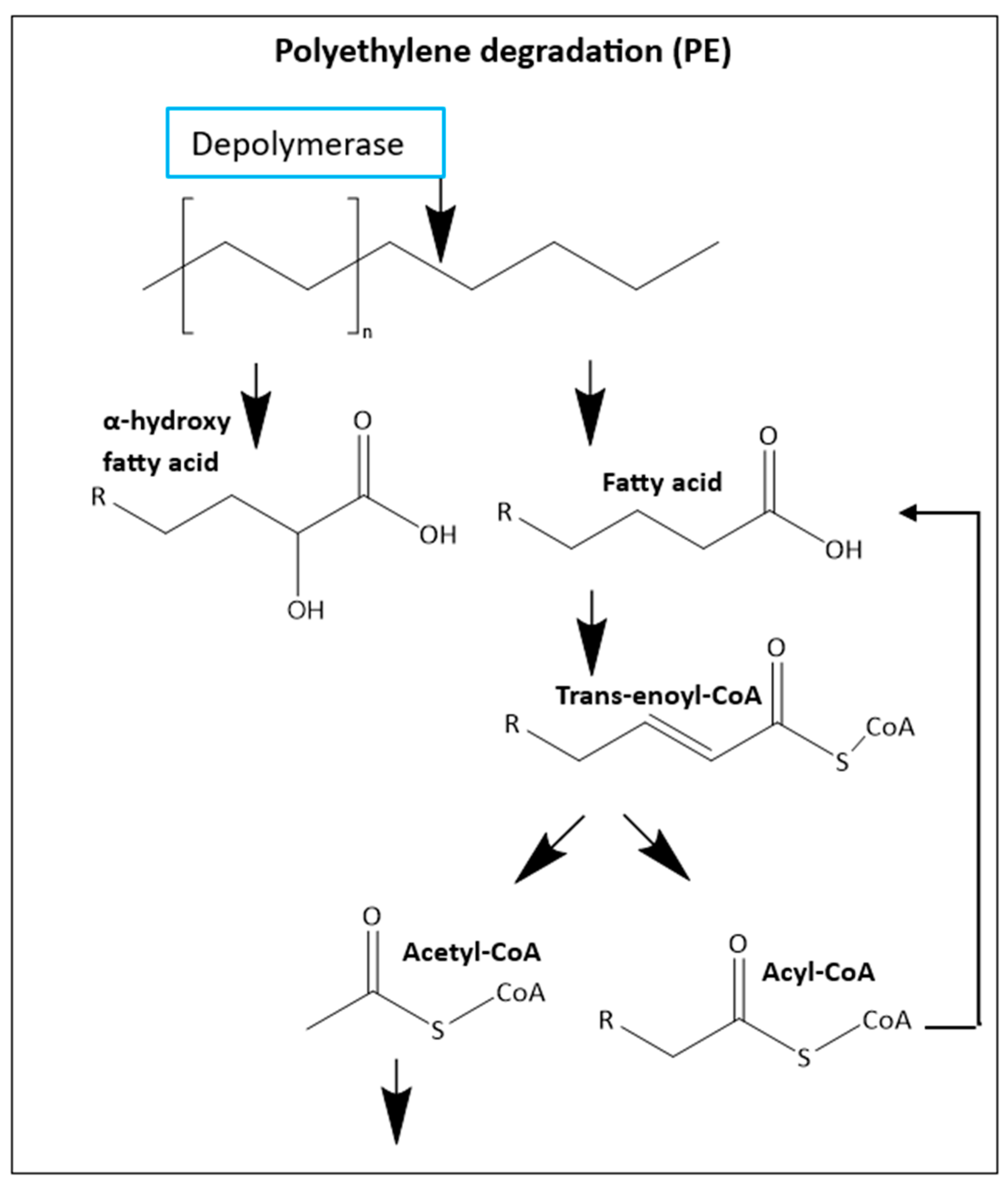

4. Microbial Degradation of Plastics

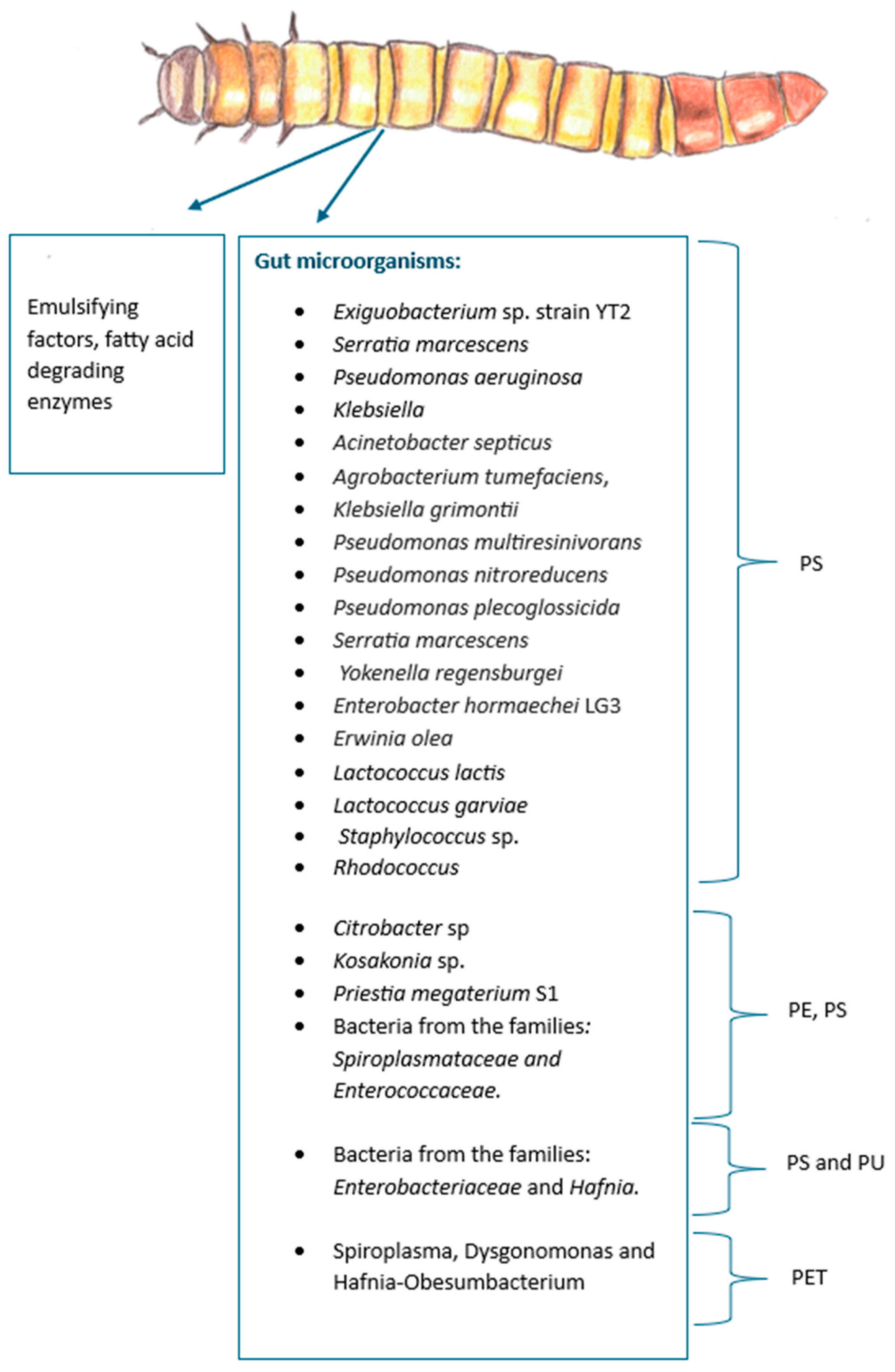

5. Insect Plastic Degradation Order: Lepidoptera (Butterflies and Moths)

The Waxworm Galleria Mellonella (Fabricius, 1798) [Lepidoptera: Pyralidae] to Degrade Plastic

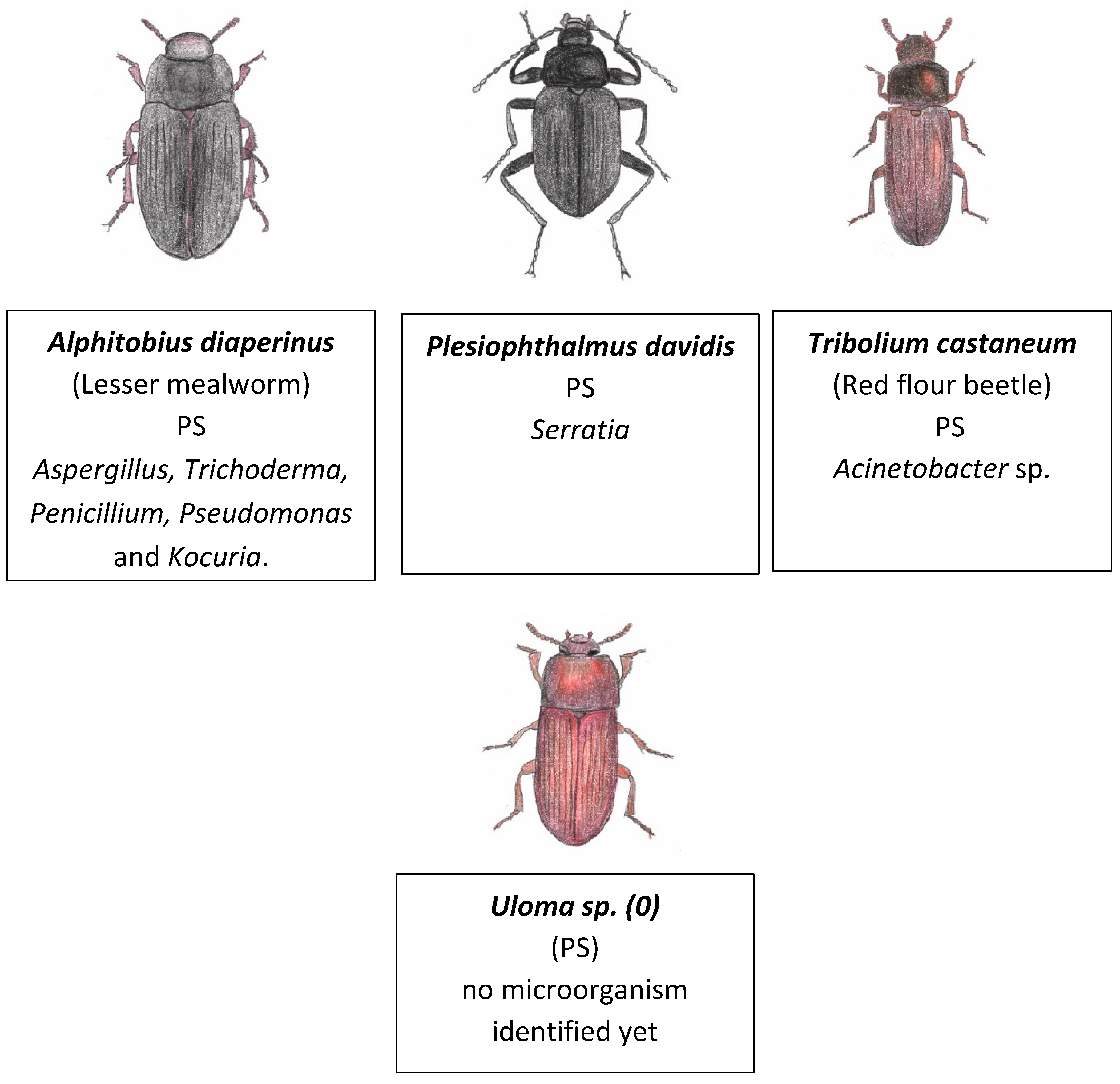

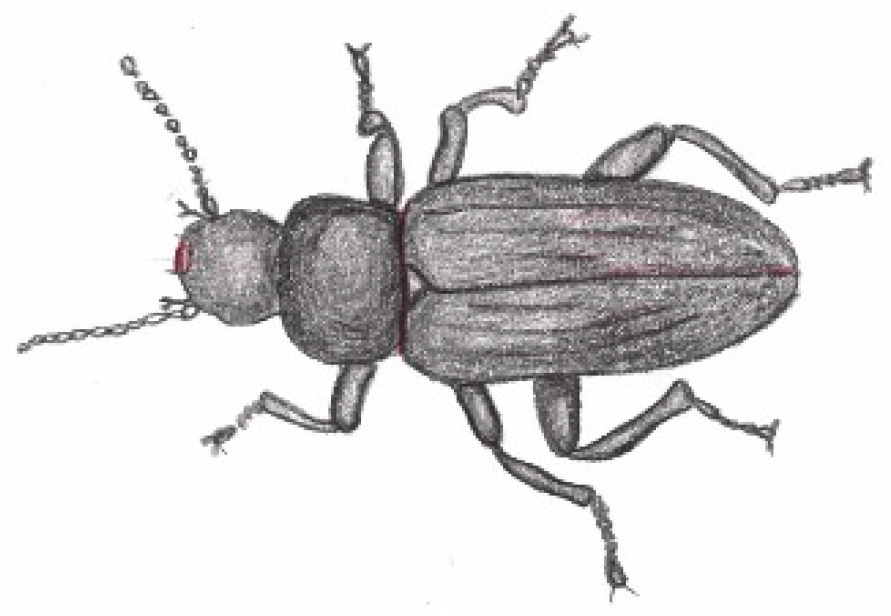

6. Insect Plastic Degradation Order: Coleoptera (Beetles and Weevils) [99]

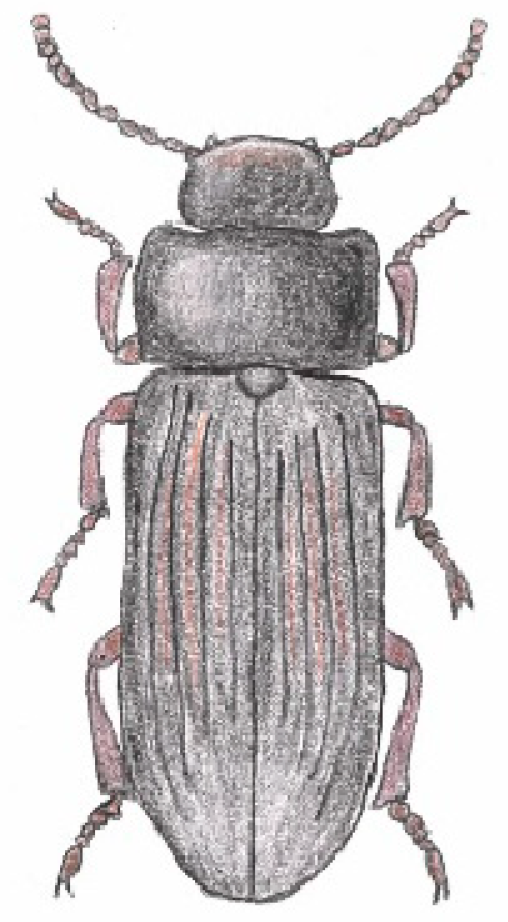

The Yellow Mealworm Tenebrio Molitor (Linnaeus, 1758) [Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae] to Degrade Plastic

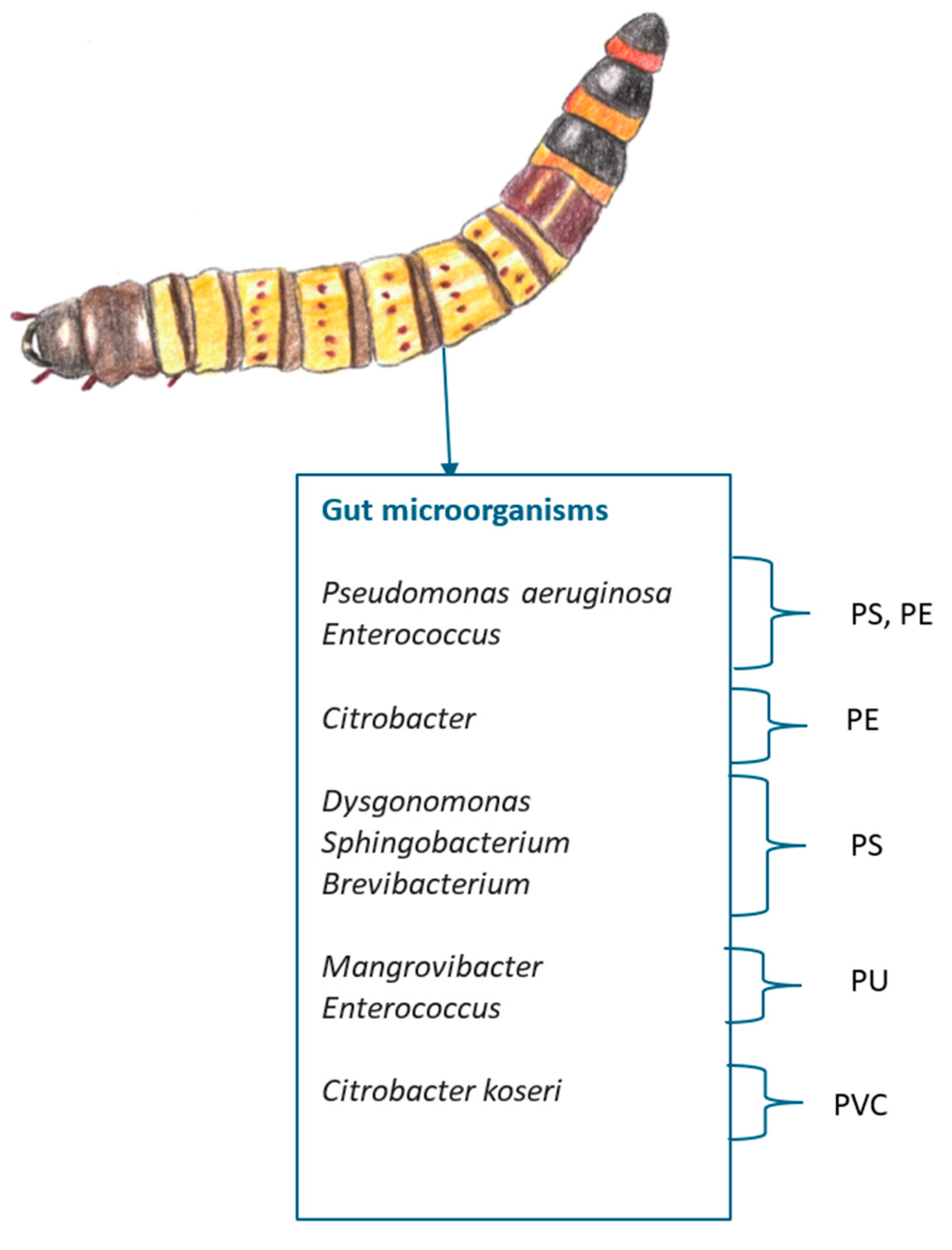

The Superworm Zophobas Atratus (Fabricius, 1776) [Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae] to Degrade Plastic

Other Organisms from the Class Insecta to Degrade Plastic

Analysis of Plastic Degradation After Exposure to Insect Larvae

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikiema, J. ;Asiedu, Z. A review of the cost and effectiveness of solutions to address plastic pollution, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2022 29, 17: 24547-24573. [CrossRef]

- Bergeson, A. R.;Silvera, A. J.;Alper, H. S. Bottlenecks in biobased approaches to plastic degradation, Nature Communications, 2024 15, 1: 4715. [CrossRef]

- Pivato, A. F. et al. Hydrocarbon-based plastics: Progress and perspectives on consumption and biodegradation by insect larvae, Chemosphere, 2022 293: 133600. [CrossRef]

- Essig, E. O.;Hoskins, W. M.;Linsley, E. G.;Micrelbacher, A. E.;Smith, R. F. A Report on the Penetration of Packaging Materials by Insects, Journal of Economic Entomology, 1943 36, 6: 822-829. [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, P. D. ;Lindgren, D. L. Penetration of packaging films: Film materials used for food packaging tested for resistance to some common stored-product insects, Hilgardia, 1954 8, 6: 3-4.

- Yang, Y.;Chen, J.;Wu, W.-M.;Zhao, J.;Yang, J. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus sp. YP1, a polyethylene-degrading bacterium from waxworm's gut, Journal of Biotechnology, 2015 200: 77-78. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.;Yang, Y.;Wu, W.-M.;Zhao, J.;Jiang, L. Evidence of Polyethylene Biodegradation by Bacterial Strains from the Guts of Plastic-Eating Waxworms, Environmental Science & Technology, 2014 48, 23: 13776-13784. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. et al. Biodegradation and Mineralization of Polystyrene by Plastic-Eating Mealworms: Part 1. Chemical and Physical Characterization and Isotopic Tests, Environmental Science & Technology, 2015 49, 20: 12080-12086. [CrossRef]

- Bombelli, P.;Howe, C. J.;Bertocchini, F. Polyethylene bio-degradation by caterpillars of the wax moth <em>Galleria mellonella</em>, Current Biology, 2017 27, 8: R292-R293. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C. This Bug Can Eat Plastic. But Can It Clean Up Our Mess?, National Geographic, 2017, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/wax-worms-eat-plastic-polyethylene-trash-pollution-cleanup.

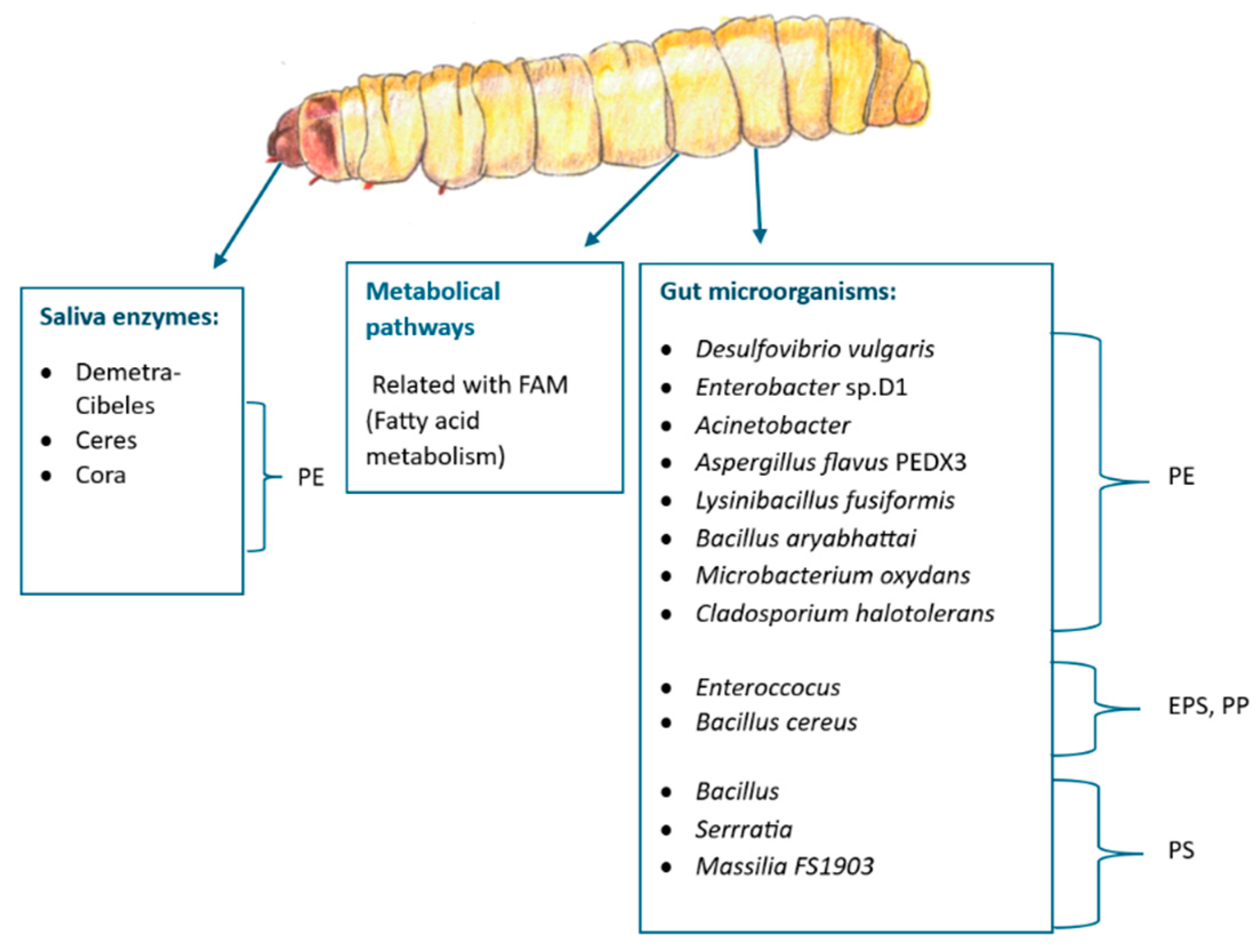

- Sanluis-Verdes, A. et al. Wax worm saliva and the enzymes therein are the key to polyethylene degradation by <em>Galleria mellonella</em>, bioRxiv, 2022: 2022.04.08.487620. [CrossRef]

- Spínola-Amilibia, M. et al. Plastic degradation by insect hexamerins: Near-atomic resolution structures of the polyethylene-degrading proteins from the wax worm saliva, Science Advances, 2023 9, 38: eadi6813. [CrossRef]

- Cassone, B. J.;Grove, H. C.;Elebute, O.;Villanueva, S. M. P.;LeMoine, C. M. R. Role of the intestinal microbiome in low-density polyethylene degradation by caterpillar larvae of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2020 287, 1922: 20200112. [CrossRef]

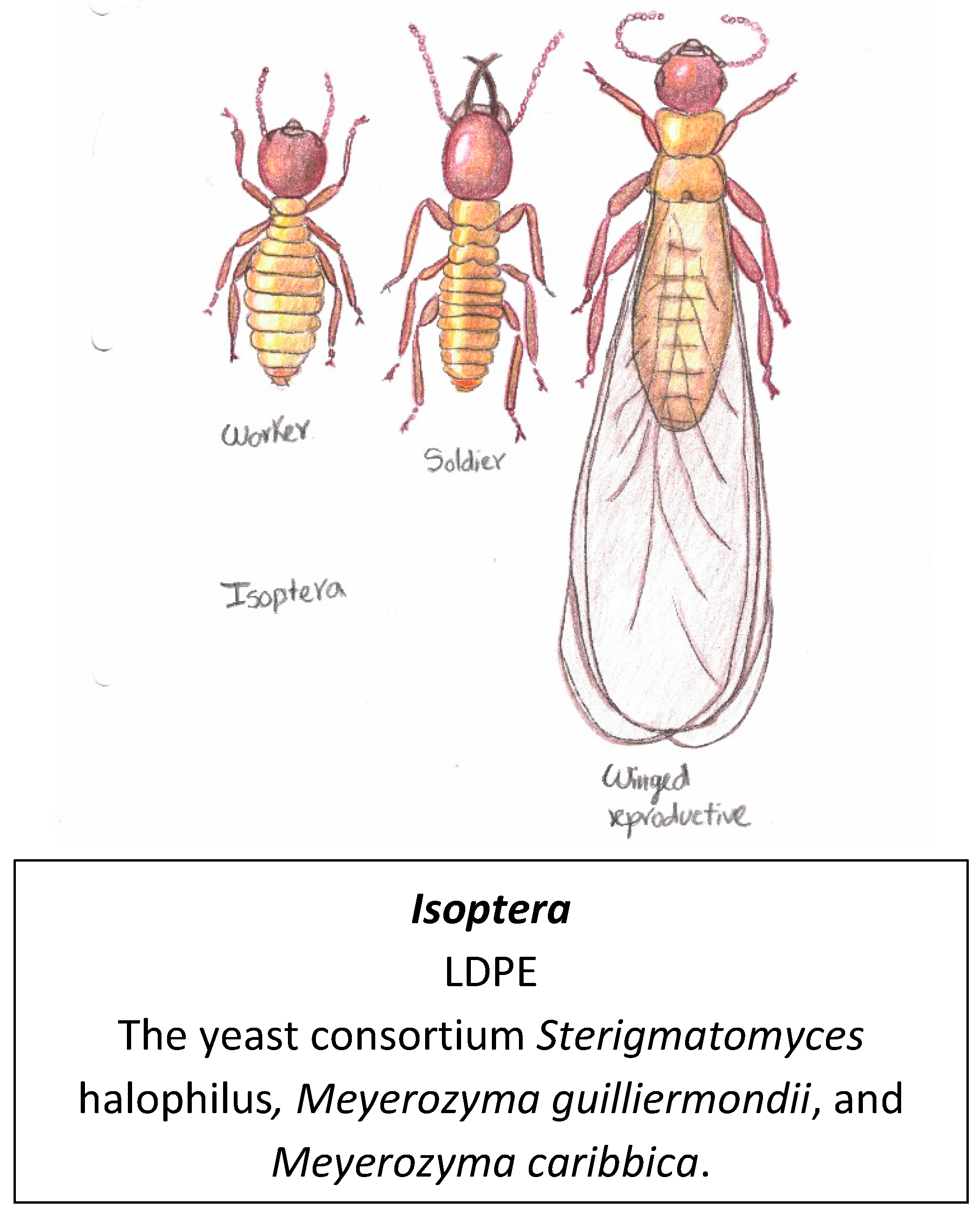

- Elsamahy, T.;Sun, J.;Elsilk, S. E.;Ali, S. S. Biodegradation of low-density polyethylene plastic waste by a constructed tri-culture yeast consortium from wood-feeding termite: Degradation mechanism and pathway, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023 448: 130944. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Hernandez, J. C. A toxicological perspective of plastic biodegradation by insect larvae, Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology, 2021 248: 109117. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S. A.;Abdul Manap, A. S.;Kolobe, S. D.;Monnye, M.;Yudhistira, B.;Fernando, I. Insects for plastic biodegradation – A review, Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 2024 186: 833-849. [CrossRef]

- An, R.;Liu, C.;Wang, J.;Jia, P. Recent Advances in Degradation of Polymer Plastics by Insects Inhabiting Microorganisms, Polymers, 2023 15, 5. [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.;Jambeck, J. R.;Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made, Science Advances, 3, 7: e1700782. [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, N.;Montazer, Z.;Sharma, P. K.;Levin, D. B. Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of Synthetic Plastics, (in English), Frontiers in Microbiology, 2020Review 11. [CrossRef]

- Telmo, O., "Polymers and the Environment," in Polymer Science, Y. Faris Ed. Rijeka: IntechOpen, 2013, p. Ch. 1.

- PlasticsEurope. "Plastics - the Facts 2019: an Analysis of European Plastics Production, Demand and Waste Data." (accessed 28 June, 2024).

- Cregut, M.;Bedas, M.;Durand, M. J.;Thouand, G. New insights into polyurethane biodegradation and realistic prospects for the development of a sustainable waste recycling process, Biotechnology Advances, 2013 31, 8: 1634-1647. [CrossRef]

- Zalasiewicz, J. et al. The geological cycle of plastics and their use as a stratigraphic indicator of the Anthropocene, Anthropocene, 2016 13: 4-17. [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P. J., "The “Anthropocene”," in Earth System Science in the Anthropocene, E. Ehlers and T. Krafft Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2006, pp. 13-18.

- Laist, D. W., "Impacts of Marine Debris: Entanglement of Marine Life in Marine Debris Including a Comprehensive List of Species with Entanglement and Ingestion Records," in Marine Debris: Sources, Impacts, and Solutions, J. M. Coe and D. B. Rogers Eds. New York, NY: Springer New York, 1997, pp. 99-139.

- Zhang, K. et al. Understanding plastic degradation and microplastic formation in the environment: A review, Environmental Pollution, 2021 274: 116554. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P. et al. Environmental occurrences, fate, and impacts of microplastics, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019 184: 109612. [CrossRef]

- Vethaak, A. D. ;Legler, J. Microplastics and human health, Science, 2021 371, 6530: 672-674. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.;Rehati, P.;Yang, Z.;Cai, Z.;Guo, C.;Li, Y. The potential toxicity of microplastics on human health, Science of The Total Environment, 2024 912: 168946. [CrossRef]

- Zurub, R. E.;Cariaco, Y.;Wade, M. G.;Bainbridge, S. A. Microplastics exposure: implications for human fertility, pregnancy and child health, (in English), Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2024Review 14. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. et al. Micro(nano)plastics pollution and human health: How plastics can induce carcinogenesis to humans?, Chemosphere, 2022 298: 134267. [CrossRef]

- Ziani, K. et al., "Microplastics: A Real Global Threat for Environment and Food Safety: A State of the Art Review," Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 3. [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H. A.;van Velzen, M. J. M.;Brandsma, S. H.;Vethaak, A. D.;Garcia-Vallejo, J. J.;Lamoree, M. H. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood, Environment International, 2022 163: 107199. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. et al. Detection of Various Microplastics in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery, Environmental Science & Technology, 2023 57, 30: 10911-10918. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.;Wu, S.;Wei, G. Adverse effects of microplastics and nanoplastics on the reproductive system: A comprehensive review of fertility and potential harmful interactions, Science of The Total Environment, 2023 903: 166258. [CrossRef]

- Programme, U. N. D. "United Nations Development Programme .Why aren't we recycling more plastic?" United Nations Development Programme https://stories.undp.org/why-arent-we-recycling-more-plastic#:~:text=Recycling%20rates%20vary%20by%20location,Some%2012%20percent%20is%20incinerated. (accessed November 28th, 2023).

- Yang, Z. et al. Is incineration the terminator of plastics and microplastics?, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021 401: 123429. [CrossRef]

- Jang, M. et al. Analysis of volatile organic compounds produced during incineration of non-degradable and biodegradable plastics, Chemosphere, 2022 303: 134946. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A. A.;Hasan, F.;Hameed, A.;Ahmed, S. Biological degradation of plastics: A comprehensive review, Biotechnology Advances, 2008 26, 3: 246-265. [CrossRef]

- Chamas, A. et al. Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2020 8, 9: 3494-3511. [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, A. et al. Temperature and light intensity effects on photodegradation of high-density polyethylene, Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2019 165: 153-160. [CrossRef]

- Yousif, E. ;Haddad, R. Photodegradation and photostabilization of polymers, especially polystyrene: review, SpringerPlus, 2013 2, 1: 398. [CrossRef]

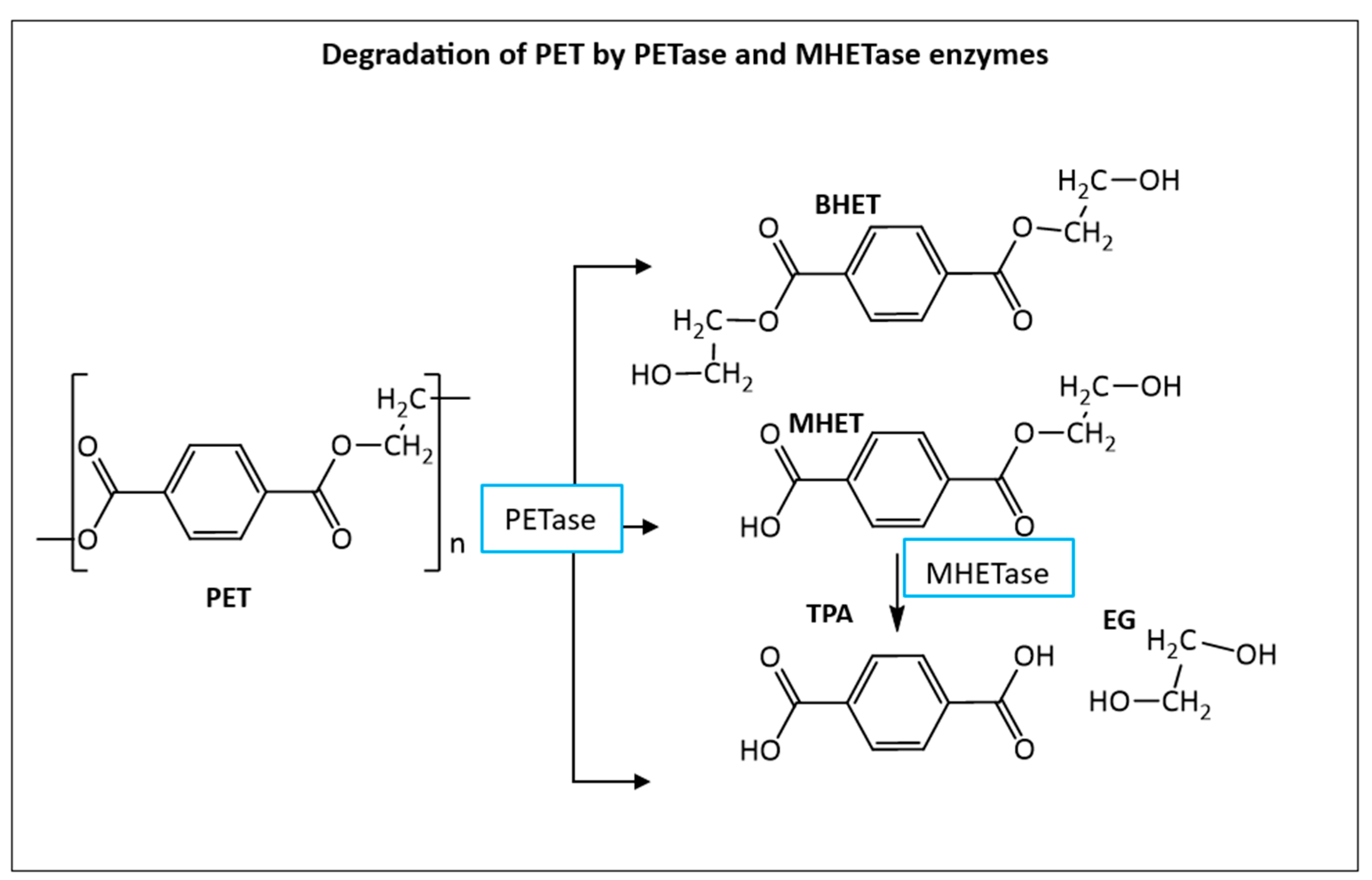

- Yoshida, S. et al. A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly(ethylene terephthalate), Science, 2016 351, 6278: 1196-1199. [CrossRef]

- Austin, H. P. et al. Characterization and engineering of a plastic-degrading aromatic polyesterase, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018 115, 19: E4350-E4357. [CrossRef]

- Danso, D. et al. New Insights into the Function and Global Distribution of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET)-Degrading Bacteria and Enzymes in Marine and Terrestrial Metagenomes, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2018 84, 8: e02773-17. [CrossRef]

- Meyer Cifuentes, I. E. et al. Molecular and Biochemical Differences of the Tandem and Cold-Adapted PET Hydrolases Ple628 and Ple629, Isolated From a Marine Microbial Consortium, (in English), Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2022Original Research 10. [CrossRef]

- Erickson, E. et al. Sourcing thermotolerant poly(ethylene terephthalate) hydrolase scaffolds from natural diversity, Nature Communications, 2022 13, 1: 7850. [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.;Yan, W.;Cao, Z.;Ding, M.;Yuan, Y., "Current Advances in the Biodegradation and Bioconversion of Polyethylene Terephthalate," Microorganisms, vol. 10, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Hollis, J. M.;Lovas, F. J.;Jewell, P. R.;Coudert, L. H. Interstellar Antifreeze: Ethylene Glycol, The Astrophysical Journal, 2002 571, 1: L59. [CrossRef]

- Hemmat Esfe, M.;Saedodin, S.;Mahian, O.;Wongwises, S. Efficiency of ferromagnetic nanoparticles suspended in ethylene glycol for applications in energy devices: Effects of particle size, temperature, and concentration, International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 2014 58: 138-146. [CrossRef]

- Westover, C. C. ;Long, T. E., "Envisioning a BHET Economy: Adding Value to PET Waste," Sustainable Chemistry, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 363-393. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.;Yin, X.;Liu, T.;Zhang, H.;Chen, G.;Wu, S. Biodegradation of bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate by a newly isolated Enterobacter sp. HY1 and characterization of its esterase properties, Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2020 60, 8: 699-711. [CrossRef]

- Gambarini, V.;Pantos, O.;Kingsbury Joanne, M.;Weaver, L.;Handley Kim, M.;Lear, G. Phylogenetic Distribution of Plastic-Degrading Microorganisms, mSystems, 2021 6, 1. [CrossRef]

- Ekanayaka, A. H. et al., "A Review of the Fungi That Degrade Plastic," Journal of Fungi, vol. 8, no. 8. [CrossRef]

- Montazer, Z.;Habibi Najafi, M. B.;Levin, D. B. Microbial degradation of low-density polyethylene and synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate polymers, Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2018 65, 3: 224-234. [CrossRef]

- Montazer, Z.;Habibi Najafi, M. B.;Levin, D. B. In vitro degradation of low-density polyethylene by new bacteria from larvae of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2020 67, 3: 249-258. [CrossRef]

- O'Leary Niall, D.;O'Connor Kevin, E.;Ward, P.;Goff, M.;Dobson Alan, D. W. Genetic Characterization of Accumulation of Polyhydroxyalkanoate from Styrene in Pseudomonas putida CA-3, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005 71, 8: 4380-4387. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. et al. Unique Raoultella species isolated from petroleum contaminated soil degrades polystyrene and polyethylene, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2023 263: 115232. [CrossRef]

- Gambarini, V.;Pantos, O.;Kingsbury, J. M.;Weaver, L.;Handley, K. M.;Lear, G. PlasticDB: a database of microorganisms and proteins linked to plastic biodegradation, Database, 2022 2022: baac008. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.;Kaur, A.;Khatri, M.;Singh, G.;Arya, S. K. A review on cutinases enzyme in degradation of microplastics, Journal of Environmental Management, 2023 347: 119193. [CrossRef]

- Oda, M.;Numoto, N.;Bekker, G.-J.;Kamiya, N.;Kawai, F., "Chapter Eight - Cutinases from thermophilic bacteria (actinomycetes): From identification to functional and structural characterization," in Methods in Enzymology, vol. 648, G. Weber, U. T. Bornscheuer, and R. Wei Eds.: Academic Press, 2021, pp. 159-185.

- Müller, R.-J.;Schrader, H.;Profe, J.;Dresler, K.;Deckwer, W.-D. Enzymatic Degradation of Poly(ethylene terephthalate): Rapid Hydrolyse using a Hydrolase from T. fusca, Macromolecular Rapid Communications, 2005 26, 17: 1400-1405. [CrossRef]

- Son, H. F. et al. Rational Protein Engineering of Thermo-Stable PETase from Ideonella sakaiensis for Highly Efficient PET Degradation, ACS Catalysis, 2019 9, 4: 3519-3526. [CrossRef]

- Bell, E. L. et al. Directed evolution of an efficient and thermostable PET depolymerase, Nature Catalysis, 2022 5, 8: 673-681. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y. et al. Computational Redesign of a PETase for Plastic Biodegradation under Ambient Condition by the GRAPE Strategy, ACS Catalysis, 2021 11, 3: 1340-1350. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H. et al. Machine learning-aided engineering of hydrolases for PET depolymerization, Nature, 2022 604, 7907: 662-667. [CrossRef]

- Di Rocco, G. et al. A PETase enzyme synthesised in the chloroplast of the microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is active against post-consumer plastics, Scientific Reports, 2023 13, 1: 10028. [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J. "Taxonomy of Lepidoptera: the scale of the problem." University College. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/taxome/lepnos.html (accessed.

- Powell, J. A., "Chapter 151 - Lepidoptera: Moths, Butterflies," in Encyclopedia of Insects (Second Edition), V. H. Resh and R. T. Cardé Eds. San Diego: Academic Press, 2009, pp. 559-587.

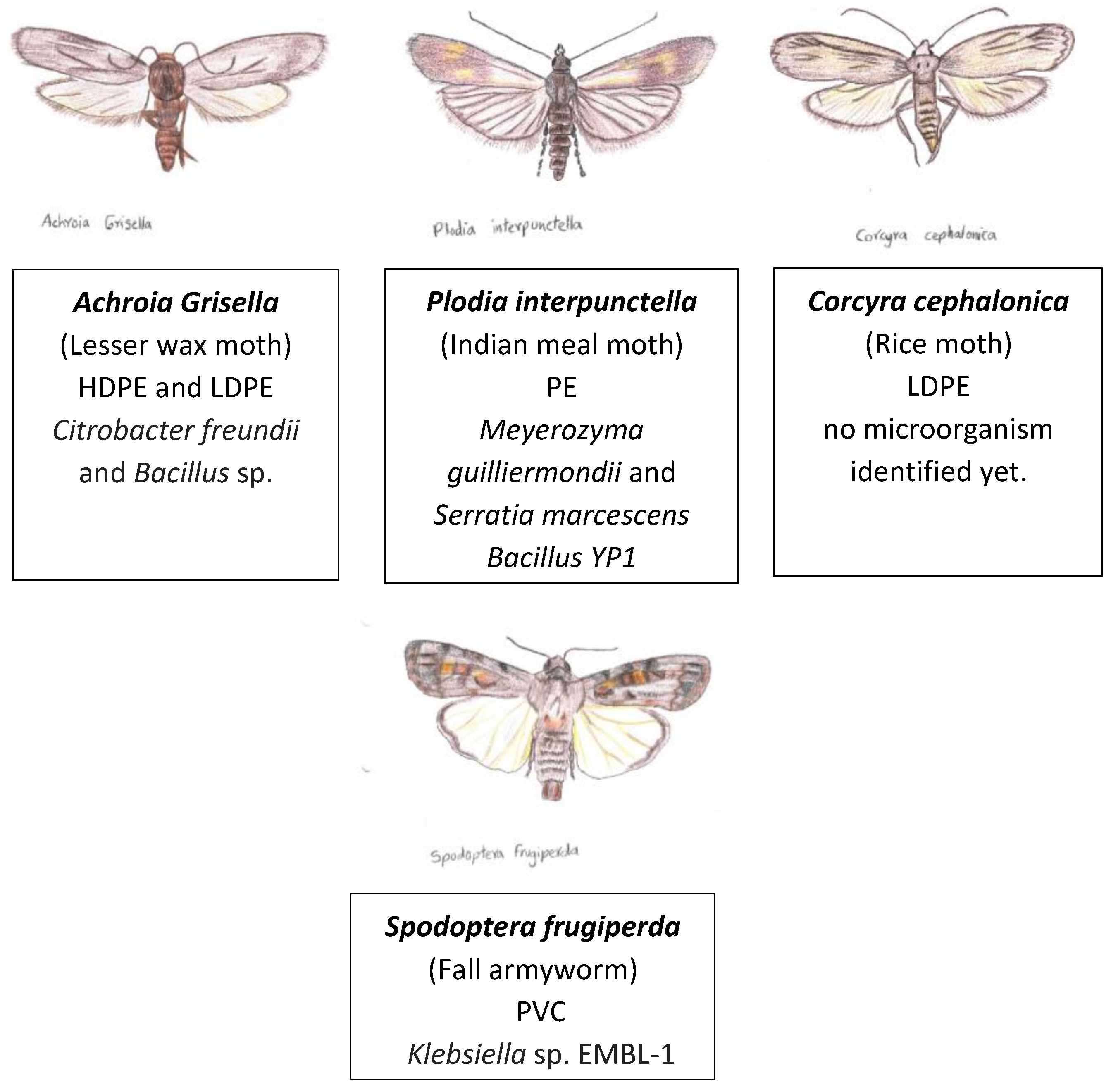

- Kundungal, H.;Gangarapu, M.;Sarangapani, S.;Patchaiyappan, A.;Devipriya, S. P. Efficient biodegradation of polyethylene (HDPE) waste by the plastic-eating lesser waxworm (Achroia grisella), Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2019 26, 18: 18509-18519. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. S.;Elsamahy, T.;Zhu, D.;Sun, J. Biodegradability of polyethylene by efficient bacteria from the guts of plastic-eating waxworms and investigation of its degradation mechanism, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023 443: 130287. [CrossRef]

- Lou, H. et al. Biodegradation of polyethylene by Meyerozyma guilliermondii and Serratia marcescens isolated from the gut of waxworms (larvae of Plodia interpunctella), Science of The Total Environment, 2022 853: 158604. [CrossRef]

- Kesti, S. S. ;Thimmappa*, S. C. First report on biodegradation of low density polyethylene by rice moth larvae, Corcyra cephalonica Holistic Approach Environmental 2019 9, 4: 79-83. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.;Peng, H.;Yang, D.;Zhang, G.;Zhang, J.;Ju, F. Polyvinyl chloride degradation by a bacterium isolated from the gut of insect larvae, Nature Communications, 2022 13, 1: 5360. [CrossRef]

- Kwadha, C. A.;Ong’amo, G. O.;Ndegwa, P. N.;Raina, S. K.;Fombong, A. T., "The Biology and Control of the Greater Wax Moth, Galleria mellonella," Insects, vol. 8, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- Mikulak, E.;Gliniewicz, A.;Przygodzka, M.;Solecka, J. Galleria mellonella L. as model organism used in biomedical and other studies, Przegląd Epidemiologiczny - Epidemiological Review, 2018journal article 72, 1: 57-73. [Online]. Available: https://www.przeglepidemiol.pzh.gov.pl/Galleria-mellonella-L-as-model-organism-used-in-biomedical-and-other-studies,180812,0,2.html.

- Asai, M.;Li, Y.;Newton, S. M.;Robertson, B. D.;Langford, P. R. Galleria mellonella–intracellular bacteria pathogen infection models: the ins and outs, FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2023 47, 2: fuad011. [CrossRef]

- Peydaei, A.;Bagheri, H.;Gurevich, L.;de Jonge, N.;Nielsen, J. L. Mastication of polyolefins alters the microbial composition in Galleria mellonella, Environmental Pollution, 2021 280: 116877. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R. et al. Exposure to polylactic acid induces oxidative stress and reduces the ceramide levels in larvae of greater wax moth (Galleria mellonella), Environmental Research, 2023 220: 115137. [CrossRef]

- Kong, H. G. et al. The <em>Galleria mellonella</em> Hologenome Supports Microbiota-Independent Metabolism of Long-Chain Hydrocarbon Beeswax, Cell Reports, 2019 26, 9: 2451-2464.e5. [CrossRef]

- Réjasse, A.;Waeytens, J.;Deniset-Besseau, A.;Crapart, N.;Nielsen-Leroux, C.;Sandt, C. Plastic biodegradation: Do Galleria mellonella Larvae Bioassimilate Polyethylene? A Spectral Histology Approach Using Isotopic Labeling and Infrared Microspectroscopy, Environmental Science & Technology, 2022 56, 1: 525-534. [CrossRef]

- Cassone, B. J.;Grove, H. C.;Kurchaba, N.;Geronimo, P.;LeMoine, C. M. R. Fat on plastic: Metabolic consequences of an LDPE diet in the fat body of the greater wax moth larvae (Galleria mellonella), Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022 425: 127862. [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y. et al. Biodegradation of Polyethylene and Polystyrene by Greater Wax Moth Larvae (Galleria mellonella L.) and the Effect of Co-diet Supplementation on the Core Gut Microbiome, Environmental Science & Technology, 2020 54, 5: 2821-2831. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Barrionuevo, J. M. et al. Consumption of low-density polyethylene, polypropylene, and polystyrene materials by larvae of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella L. (Lepidoptera, Pyralidae), impacts on their ontogeny, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2022 29, 45: 68132-68142. [CrossRef]

- Kundungal, H.;Gangarapu, M.;Sarangapani, S.;Patchaiyappan, A.;Devipriya, S. P. Role of pretreatment and evidence for the enhanced biodegradation and mineralization of low-density polyethylene films by greater waxworm, Environmental Technology, 2021 42, 5: 717-730. [CrossRef]

- Peydaei, A.;Bagheri, H.;Gurevich, L.;de Jonge, N.;Nielsen, J. L. Impact of polyethylene on salivary glands proteome in Galleria melonella, Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics, 2020 34: 100678. [CrossRef]

- Ren, L. et al. Biodegradation of Polyethylene by Enterobacter sp. D1 from the Guts of Wax Moth Galleria mellonella, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2019 16, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. et al. Biodegradation of polyethylene microplastic particles by the fungus Aspergillus flavus from the guts of wax moth Galleria mellonella, Science of The Total Environment, 2020 704: 135931. [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, M. et al. High density polyethylene (HDPE) biodegradation by the fungus Cladosporium halotolerans, FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2023 99, 2: fiac148. [CrossRef]

- Nyamjav, I.;Jang, Y.;Park, N.;Lee, Y. E.;Lee, S. Physicochemical and Structural Evidence that Bacillus cereus Isolated from the Gut of Waxworms (Galleria mellonella Larvae) Biodegrades Polypropylene Efficiently In Vitro, Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 2023 31, 10: 4274-4287. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.;Su, T.;Zhao, J.;Wang, Z. Isolation, Identification, and Characterization of Polystyrene-Degrading Bacteria From the Gut of Galleria Mellonella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) Larvae, (in English), Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2021Original Research 9. [CrossRef]

- LeMoine, C. M. R.;Grove, H. C.;Smith, C. M.;Cassone, B. J. A Very Hungry Caterpillar: Polyethylene Metabolism and Lipid Homeostasis in Larvae of the Greater Wax Moth (Galleria mellonella), Environmental Science & Technology, 2020 54, 22: 14706-14715. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.;Nong, W.;Xie, Y.;Hui, J. H. L.;Chu, L. M. Long-term effect of plastic feeding on growth and transcriptomic response of mealworms (Tenebrio molitor L.), Chemosphere, 2022 287: 132063. [CrossRef]

- Young, R. et al. Improved reference quality genome sequence of the plastic-degrading greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics, 2024: jkae070. [CrossRef]

- Venegas, S. et al., "Biodegradation of Polystyrene by Galleria mellonella: Identification of Potential Enzymes Involved in the Degradative Pathway," Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 3. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. et al. Complete digestion/biodegradation of polystyrene microplastics by greater wax moth (Galleria mellonella) larvae: Direct in vivo evidence, gut microbiota independence, and potential metabolic pathways, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022 423: 127213. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, K.;Buckley, C. M.;Hartmans, S.;Dobson, A. D. Possible regulatory role for nonaromatic carbon sources in styrene degradation by Pseudomonas putida CA-3, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1995 61, 2: 544-548. [CrossRef]

- Noël, G.;Serteyn, L.;Sare, A. R.;Massart, S.;Delvigne, F.;Francis, F. Co-diet supplementation of low density polyethylene and honeybee wax did not influence the core gut bacteria and associated enzymes of Galleria mellonella larvae (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), International Microbiology, 2023 26, 2: 397-409. [CrossRef]

- Gressitt, J. L. "Coleopteran." https://www.britannica.com/animal/beetle. (accessed.

- Cucini, C.;Leo, C.;Vitale, M.;Frati, F.;Carapelli, A.;Nardi, F. Bacterial and fungal diversity in the gut of polystyrene-fed Alphitobius diaperinus (Insecta: Coleoptera), Animal Gene, 2020 17-18: 200109. [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.;Song, I.;Cha Hyung, J. Fast and Facile Biodegradation of Polystyrene by the Gut Microbial Flora of Plesiophthalmus davidis Larvae, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2020 86, 18: e01361-20. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.;Xin, X.;Shi, X.;Zhang, Y. A polystyrene-degrading Acinetobacter bacterium isolated from the larvae of Tribolium castaneum, Science of The Total Environment, 2020 726: 138564. [CrossRef]

- Kundungal, H.;Synshiang, K.;Devipriya, S. P. Biodegradation of polystyrene wastes by a newly reported honey bee pest Uloma sp. larvae: An insight to the ability of polystyrene-fed larvae to complete its life cycle, Environmental Challenges, 2021 4: 100083. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.;Han, T.;Kim, Y. Y., "Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor Larvae) as an Alternative Protein Source for Monogastric Animal: A Review," Animals, vol. 10, no. 11. [CrossRef]

- Shafique, L. et al., "The Feasibility of Using Yellow Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor): Towards a Sustainable Aquafeed Industry," Animals, vol. 11, no. 3. [CrossRef]

- Seong Hyeon, K.;Wonho, C.;Seong-Jin, H.;Nam-Jeong, K. Nutritional Value of Mealworm, Tenebrio molitor as Food Source, International Journal of Industrial Entomology., 2012 25, 1: 93-98. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, E. et al. The impact of polystyrene consumption by edible insects Tenebrio molitor and Zophobas morio on their nutritional value, cytotoxicity, and oxidative stress parameters, Food Chemistry, 2021 345: 128846. [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y. H.;Lee, J. H.;Patnaik, B. B.;Keshavarz, M.;Lee, Y. S.;Han, Y. S. Autophagy in Tenebrio molitor Immunity: Conserved Antimicrobial Functions in Insect Defenses, (in English), Frontiers in Immunology, 2021Review 12. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, M. W. ;Judge, K. A. Body size and lifespan are condition dependent in the mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor, but not sexually selected traits, Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2018 72, 3: 32. [CrossRef]

- Machona, O.;Chidzwondo, F.;Mangoyi, R. Tenebrio molitor: possible source of polystyrene-degrading bacteria, BMC Biotechnology, 2022 22, 1: 2. [CrossRef]

- Urbanek, A. K.;Rybak, J.;Wróbel, M.;Leluk, K.;Mirończuk, A. M. A comprehensive assessment of microbiome diversity in Tenebrio molitor fed with polystyrene waste, Environmental Pollution, 2020 262: 114281. [CrossRef]

- Brandon, A. M. et al. Biodegradation of Polyethylene and Plastic Mixtures in Mealworms (Larvae of Tenebrio molitor) and Effects on the Gut Microbiome, Environmental Science & Technology, 2018 52, 11: 6526-6533. [CrossRef]

- Brandon, A. M.;Garcia, A. M.;Khlystov, N. A.;Wu, W.-M.;Criddle, C. S. Enhanced Bioavailability and Microbial Biodegradation of Polystyrene in an Enrichment Derived from the Gut Microbiome of Tenebrio molitor (Mealworm Larvae), Environmental Science & Technology, 2021 55, 3: 2027-2036. [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.-Y. et al. Biodegradation of Polystyrene by Dark (Tenebrio obscurus) and Yellow (Tenebrio molitor) Mealworms (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), Environmental Science & Technology, 2019 53, 9: 5256-5265. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. et al. Biodegradation and Mineralization of Polystyrene by Plastic-Eating Mealworms: Part 2. Role of Gut Microorganisms, Environmental Science & Technology, 2015 49, 20: 12087-12093. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-S. et al. Biodegradation of polystyrene wastes in yellow mealworms (larvae of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus): Factors affecting biodegradation rates and the ability of polystyrene-fed larvae to complete their life cycle, Chemosphere, 2018 191: 979-989. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.;Su, T.;Zhao, J.;Wang, Z. Biodegradation of Polystyrene by Tenebrio molitor, Galleria mellonella, and Zophobas atratus Larvae and Comparison of Their Degradation Effects, Polymers, 2021 13, 20. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. et al. Biodegradation of expanded polystyrene and low-density polyethylene foams in larvae of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae): Broad versus limited extent depolymerization and microbe-dependence versus independence, Chemosphere, 2021 262: 127818. [CrossRef]

- He, L. et al. Responses of gut microbiomes to commercial polyester polymer biodegradation in Tenebrio molitor Larvae, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023 457: 131759. [CrossRef]

- Mamtimin, T. et al. Gut microbiome of mealworms (Tenebrio molitor Larvae) show similar responses to polystyrene and corn straw diets, Microbiome, 2023 11, 1: 98. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.;Hu, L.;Li, X.;Wang, J.;Jin, G. Nitrogen Fixation and Diazotrophic Community in Plastic-Eating Mealworms Tenebrio molitor L, Microbial Ecology, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tsochatzis, E.;Berggreen, I. E.;Tedeschi, F.;Ntrallou, K.;Gika, H.;Corredig, M., "Gut Microbiome and Degradation Product Formation during Biodegradation of Expanded Polystyrene by Mealworm Larvae under Different Feeding Strategies," Molecules, vol. 26, no. 24. [CrossRef]

- Gan, S. K.;Phua, S.-X.;Yeo, J. Y.;Heng, Z. S.;Xing, Z. Method for Zero-Waste Circular Economy Using Worms for Plastic Agriculture: Augmenting Polystyrene Consumption and Plant Growth, Methods and Protocols, 2021 4, 2. [CrossRef]

- Gan, S. K.;Phua, S.-X.;Yeo, J. Y.;Heng, Z. S.;Xing, Z., "Method for Zero-Waste Circular Economy Using Worms for Plastic Agriculture: Augmenting Polystyrene Consumption and Plant Growth," Methods and Protocols, vol. 4, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y. et al. Response of the yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) gut microbiome to diet shifts during polystyrene and polyethylene biodegradation, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021 416: 126222. [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.-Y. et al. Unveiling Fragmentation of Plastic Particles during Biodegradation of Polystyrene and Polyethylene Foams in Mealworms: Highly Sensitive Detection and Digestive Modeling Prediction, Environmental Science & Technology, 2023 57, 40: 15099-15111. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.;Xian, Z.-N.;Yue, W.;Yin, C.-F.;Zhou, N.-Y. Degradation of polyvinyl chloride by a bacterial consortium enriched from the gut of Tenebrio molitor larvae, Chemosphere, 2023 318: 137944. [CrossRef]

- Xian, Z.-N.;Yin, C.-F.;Zheng, L.;Zhou, N.-Y.;Xu, Y. Biodegradation of additive-free polypropylene by bacterial consortia enriched from the ocean and from the gut of Tenebrio molitor larvae, Science of The Total Environment, 2023 892: 164721. [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.;Feng, P.;Cheng, Z.;Wang, D. Effect of biodegrading polyethylene, polystyrene, and polyvinyl chloride on the growth and development of yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) larvae, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023 30, 13: 37118-37126. [CrossRef]

- Leicht, A. ;Masuda, H. Ingestion of Nylon 11 Polymers by the Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) Beetle and Subsequent Enrichment of Monomer-Metabolizing Bacteria in Fecal Microbiome, FBE, 2023 15, 2. [CrossRef]

- Leicht, A.;Gatz-Schrupp, J.;Masuda, H. Discovery of Nylon 11 ingestion by mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) larvae and detection of monomer-degrading bacteria in gut microbiota, AIMS Microbiology, 2022 8, 4: 612-623. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. et al. Differences in ingestion and biodegradation of the melamine formaldehyde plastic by yellow mealworms Tenebrio molitor and superworms Zophobas atratus, and the prediction of functional gut microbes, Chemosphere, 2024 352: 141499. [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.-Y. et al. Biodegradation of polyvinyl chloride, polystyrene, and polylactic acid microplastics in Tenebrio molitor larvae: Physiological responses, Journal of Environmental Management, 2023 345: 118818. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. et al. Biodegradation of polyether-polyurethane foam in yellow mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) and effects on the gut microbiome, Chemosphere, 2022 304: 135263. [CrossRef]

- Orts, J. M. et al., "Polyurethane Foam Residue Biodegradation through the Tenebrio molitor Digestive Tract: Microbial Communities and Enzymatic Activity," Polymers, vol. 15, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.;Yin, J.;Hao, W.;Jiao, M. Polyurethane foam induces epigenetic modification of mitochondrial DNA during different metamorphic stages of Tenebrio molitor, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019 183: 109461. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. et al. Ingestion and biodegradation of disposable surgical masks by yellow mealworms Tenebrio molitor larvae: Differences in mask layers and effects on the larval gut microbiome, Science of The Total Environment, 2023 904: 166808. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-S. et al. Impacts of physical-chemical property of polyethylene on depolymerization and biodegradation in yellow and dark mealworms with high purity microplastics, Science of The Total Environment, 2022 828: 154458. [CrossRef]

- Akash, K.;Parthasarathi, R.;Elango, R.;Bragadeeswaran, S. Characterization of Priestia megaterium S1, a polymer degrading gut microbe isolated from the gut of Tenebrio molitor larvae fed on Styrofoam, Archives of Microbiology, 2023 206, 1: 48. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-W.;Kim, M.;Kim, S.-Y.;Bae, J.;Kim, T.-J. Biodegradation of polystyrene by intestinal symbiotic bacteria isolated from mealworms, the larvae of <em>Tenebrio molitor</em>, Heliyon, 2023 9, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.-G.;Kwak, M.-J.;Kim, Y. Polystyrene microplastics biodegradation by gut bacterial Enterobacter hormaechei from mealworms under anaerobic conditions: Anaerobic oxidation and depolymerization, Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023 459: 132045. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.;Tao, H.;Wong, M. H. Feeding and metabolism effects of three common microplastics on Tenebrio molitor L, Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 2019 41, 1: 17-26. [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.-Y. et al. Influence of Polymer Size on Polystyrene Biodegradation in Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor): Responses of Depolymerization Pattern, Gut Microbiome, and Metabolome to Polymers with Low to Ultrahigh Molecular Weight, Environmental Science & Technology, 2022 56, 23: 17310-17320. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-S. et al. Ubiquity of polystyrene digestion and biodegradation within yellow mealworms, larvae of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), Chemosphere, 2018 212: 262-271. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. et al. Different plastics ingestion preferences and efficiencies of superworm (Zophobas atratus Fab.) and yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor Linn.) associated with distinct gut microbiome changes, Science of The Total Environment, 2022 837: 155719. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.;Xia, M.;Yang, Y. Biodegradation of vulcanized rubber by a gut bacterium from plastic-eating mealworms, (in eng), J Hazard Mater, 2023 448: 130940. [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.-Q. et al. Gut Microbiome Associating with Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism during Biodegradation of Polyethene in Tenebrio larvae with Crop Residues as Co-Diets, Environmental Science & Technology, 2023 57, 8: 3031-3041. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-S. et al. Confirmation of biodegradation of low-density polyethylene in dark- versus yellow- mealworms (larvae of Tenebrio obscurus versus Tenebrio molitor) via. gut microbe-independent depolymerization, Science of The Total Environment, 2021 789: 147915. [CrossRef]

- Rumbos, C. I. ;Athanassiou, C. G. The Superworm, Zophobas morio (Coleoptera:Tenebrionidae): A ‘Sleeping Giant’ in Nutrient Sources, Journal of Insect Science, 2021 21, 2: 13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.;Wang, J.;Xia, M. Biodegradation and mineralization of polystyrene by plastic-eating superworms Zophobas atratus, Science of The Total Environment, 2020 708: 135233. [CrossRef]

- Lu, B. et al. Understanding the Ecological Robustness and Adaptability of the Gut Microbiome in Plastic-Degrading Superworms (Zophobas atratus) in Response to Microplastics and Antibiotics, Environmental Science & Technology, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zaman, I. et al. Biodegradation of polyethylene and polystyrene by Zophobas atratus larvae from Bangladeshi source and isolation of two plastic-degrading gut bacteria, Environmental Pollution, 2024 345: 123446. [CrossRef]

- Nyamjav, I.;Jang, Y.;Lee, Y. E.;Lee, S. Biodegradation of polyvinyl chloride by Citrobacter koseri isolated from superworms (Zophobas atratus larvae), (in English), Frontiers in Microbiology, 2023Original Research 14. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-N.;Bairoliya, S.;Zaiden, N.;Cao, B. Establishment of plastic-associated microbial community from superworm gut microbiome, Environment International, 2024 183: 108349. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. et al. Biodegradation of foam plastics by Zophobas atratus larvae (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) associated with changes of gut digestive enzymes activities and microbiome, Chemosphere, 2021 282: 131006. [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.;Han, X.;Sun, H.;Wang, J.;Wang, Y.;Zhao, X. Effects of polymerization types on plastics ingestion and biodegradation by Zophobas atratus larvae, and successions of both gut bacterial and fungal microbiomes, Environmental Research, 2024 251: 118677. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H. et al. Circular waste management: Superworms as a sustainable solution for biodegradable plastic degradation and resource recovery, Waste Management, 2023 171: 568-579. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. R. et al. Biodegradation of Polystyrene by Pseudomonas sp. Isolated from the Gut of Superworms (Larvae of Zophobas atratus), Environmental Science & Technology, 2020 54, 11: 6987-6996. [CrossRef]

- Arunrattiyakorn, P. et al. Biodegradation of polystyrene by three bacterial strains isolated from the gut of Superworms (Zophobas atratus larvae), Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2022 132, 4: 2823-2831. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Triggered Oxidative Degradation of Polystyrene in the Gut of Superworms (Zophobas atratus Larvae), Environmental Science & Technology, 2023 57, 20: 7867-7874. [CrossRef]

- Inward, D.;Beccaloni, G.;Eggleton, P. Death of an order: a comprehensive molecular phylogenetic study confirms that termites are eusocial cockroaches, Biology Letters, 2007 3, 3: 331-335. [CrossRef]

- Kalleshwaraswamy, C. M.;Shanbhag, R. R.;Sundararaj, R., "Wood Degradation by Termites: Ecology, Economics and Protection," in Science of Wood Degradation and its Protection, R. Sundararaj Ed. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2022, pp. 147-170.

- Côté, W. A., "Chemical Composition of Wood," in Principles of Wood Science and Technology: I Solid Wood, F. F. P. Kollmann and W. A. Côté Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1968, pp. 55-78.

- Al-Tohamy, R. et al. Environmental and Human Health Impact of Disposable Face Masks During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Wood-Feeding Termites as a Model for Plastic Biodegradation, Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2023 195, 3: 2093-2113. [CrossRef]

- López-Naranjo, E. J.;Alzate-Gaviria, L. M.;Hernández-Zárate, G.;Reyes-Trujeque, J.;Cupul-Manzano, C. V.;Cruz-Estrada, R. H. Effect of biological degradation by termites on the flexural properties of pinewood residue/recycled high-density polyethylene composites, Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2013 128, 5: 2595-2603. [CrossRef]

- Samir Ali, S.;Al-Tohamy, R.;Sun, J.;Wu, J.;Huizi, L. Screening and construction of a novel microbial consortium SSA-6 enriched from the gut symbionts of wood-feeding termite, Coptotermes formosanus and its biomass-based biorefineries, Fuel, 2019 236: 1128-1145. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, L. F.;Tirado, B.;Cruz-Cárdenas, C. I.;Rojas-Anaya, E.;Aragón-Magadán, M. A., "De Novo Transcriptome Assembly of Cedar (Cedrela odorata L.) and Differential Gene Expression Involved in Herbivore Resistance," Current Issues in Molecular Biology, vol. 46, no. 8, pp. 8794-8806. [CrossRef]

- Baranchikov, Y.;Mozolevskaya, E.;Yurchenko, G.;Kenis, M. Occurrence of the emerald ash borer, Agrilus planipennis in Russia and its potential impact on European forestry, EPPO Bulletin, 2008 38, 2: 233-238. [CrossRef]

- Mayfield Iii, A. E. et al. Suitability of California bay laurel and other species as hosts for the non-native redbay ambrosia beetle and granulate ambrosia beetle, Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 2013 15, 3: 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Meng, P. S.;Hoover, K.;Keena, M. A. Asian Longhorned Beetle (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), an Introduced Pest of Maple and Other Hardwood Trees in North America and Europe, Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2015 6, 1: 4. [CrossRef]

- Linnakoski, R. ;Forbes, K. M. Pathogens—The Hidden Face of Forest Invasions by Wood-Boring Insect Pests, (in English), Frontiers in Plant Science, 2019Opinion 10. [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, P.;Verardi, A.;Dimatteo, S.;Spagnoletta, A.;Moliterni, S.;Errico, S. Tenebrio molitorin the circular economy: a novel approach for plastic valorisation and PHA biological recovery, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021 28, 38: 52689-52701. [CrossRef]

- Kundungal, H. ;Devipriya, S. P. Nature’s solution to degrade long-chain hydrocarbons: A life cycle study of beeswax and plastic eating insect larvae, Research Square 2024.

- Yang, S.-S. et al. Radical innovation breakthroughs of biodegradation of plastics by insects: history, present and future perspectives, Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering, 2024 18, 6: 78. [CrossRef]

- Boctor, J.;Pandey, G.;Xu, W.;Murphy, D. V.;Hoyle, F. C., "Nature’s Plastic Predators: A Comprehensive and Bibliometric Review of Plastivore Insects," Polymers, vol. 16, no. 12. [CrossRef]

- Milum, V. G. Vitula edmandsii as a Pest of Honeybee Combs, Journal of Economic Entomology, 1953 46, 4: 710-711. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M. F. ;Rossi, C. C. Overview of rearing and testing conditions and a guide for optimizing Galleria mellonella breeding and use in the laboratory for scientific purposes, APMIS, 2020 128, 12: 607-620. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.;Shen, Y.;Li, X.;Liu, X.;Qian, G.;Zhou, J. Feeding preference of insect larvae to waste electrical and electronic equipment plastics, Science of The Total Environment, 2022 807: 151037. [CrossRef]

- Guberman, R. "The Complete Plastics Recycling Process." https://www.rts.com/blog/the-complete-plastics-recycling-process-rts/ (accessed September 12, 2024).

- Billen, P.;Khalifa, L.;Van Gerven, F.;Tavernier, S.;Spatari, S. Technological application potential of polyethylene and polystyrene biodegradation by macro-organisms such as mealworms and wax moth larvae, Science of The Total Environment, 2020 735: 139521. [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J. "Current Plastic Recycling Prices." https://blog.recycleduklimited.com/current-plastic-recycling-prices (accessed 12 September 2024).

- Manzano-Agugliaro, F.;Sanchez-Muros, M. J.;Barroso, F. G.;Martínez-Sánchez, A.;Rojo, S.;Pérez-Bañón, C. Insects for biodiesel production, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2012 16, 6: 3744-3753. [CrossRef]

- Siow, H. S.;Sudesh, K.;Ganesan, S. Insect oil to fuel: Optimizing biodiesel production from mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) oil using response surface methodology, Fuel, 2024 371: 132099. [CrossRef]

- Ilijin, L. et al. Sourcing chitin from exoskeleton of Tenebrio molitor fed with polystyrene or plastic kitchen wrap, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2024 268: 131731. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, S., "Chitin Biotechnology Applications," in Biotechnology Annual Review, vol. 2, M. R. El-Gewely Ed.: Elsevier, 1996, pp. 237-258.

- Peng, B. Y. et al. Unveiling Fragmentation of Plastic Particles during Biodegradation of Polystyrene and Polyethylene Foams in Mealworms: Highly Sensitive Detection and Digestive Modeling Prediction, (in eng), Environ Sci Technol, 2023 57, 40: 15099-15111. [CrossRef]

- "Carbon Emissions and Plastic Waste. QM recylced energy." https://www.qmre.ltd/ (accessed 16 September 2024).

- Finnveden, G. et al. Recent developments in Life Cycle Assessment, Journal of Environmental Management, 2009 91, 1: 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Drugmand, J.-C.;Schneider, Y.-J.;Agathos, S. N. Insect cells as factories for biomanufacturing, Biotechnology Advances, 2012 30, 5: 1140-1157. [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, K. ;Collins, J. The roots—a short history of industrial microbiology and biotechnology, Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2013 97, 9: 3747-3762. [CrossRef]

- Sadler, J. C. ;Wallace, S. Microbial synthesis of vanillin from waste poly(ethylene terephthalate), Green Chemistry, 202110.1039/D1GC00931A 23, 13: 4665-4672. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, G. ;Chattopadhyay, P. Vanillin biotechnology: the perspectives and future, Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2019 99, 2: 499-506. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).