Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

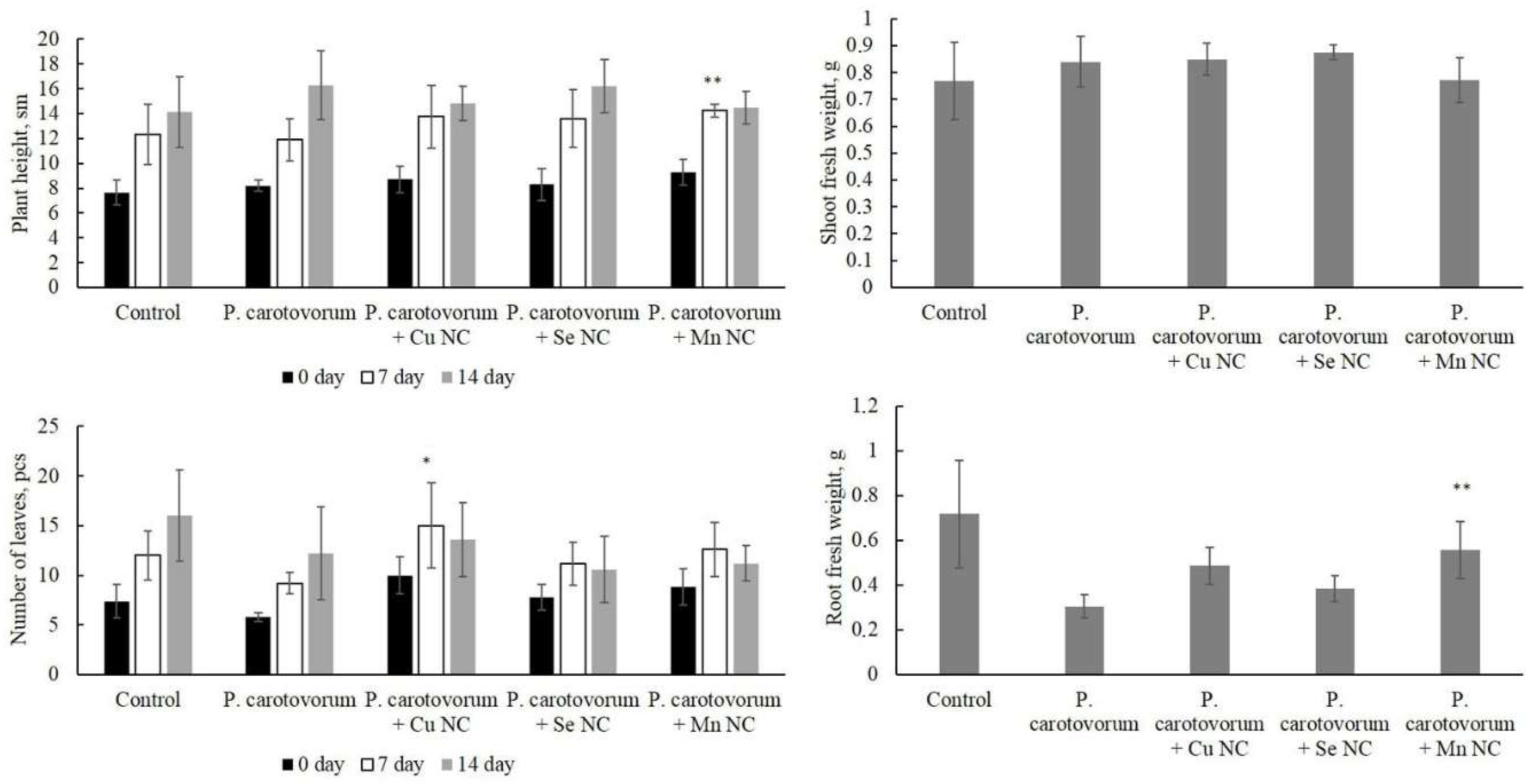

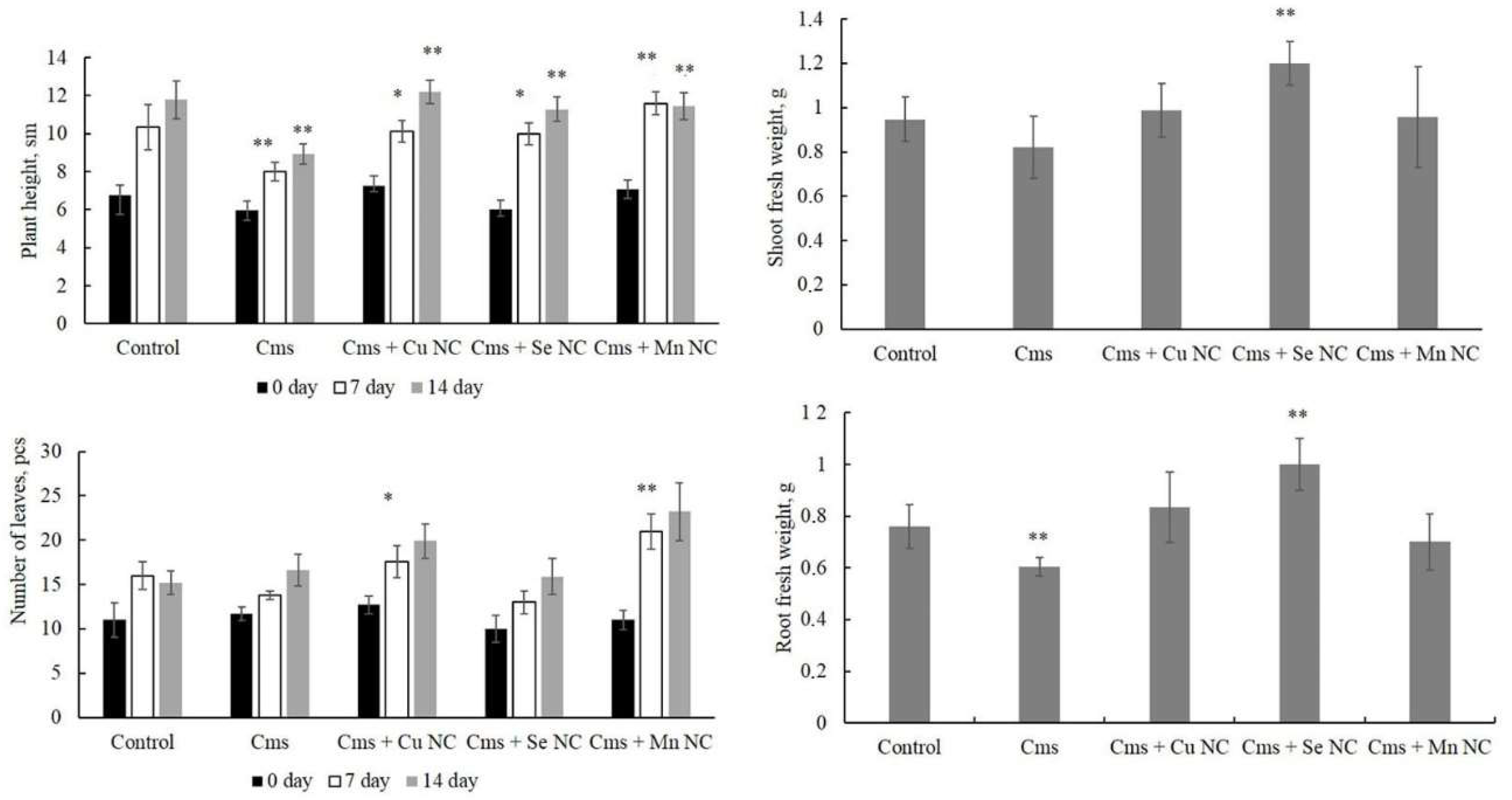

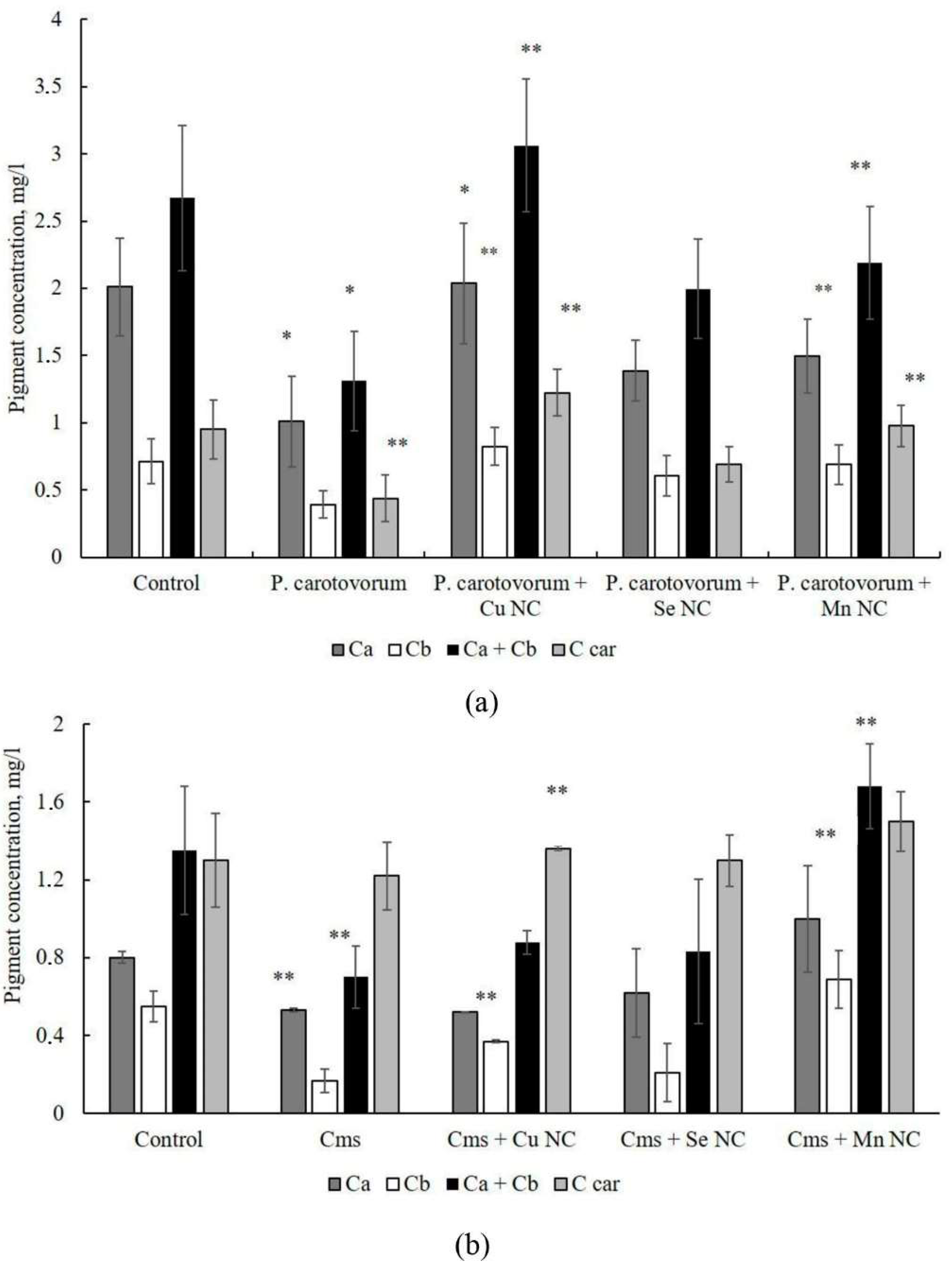

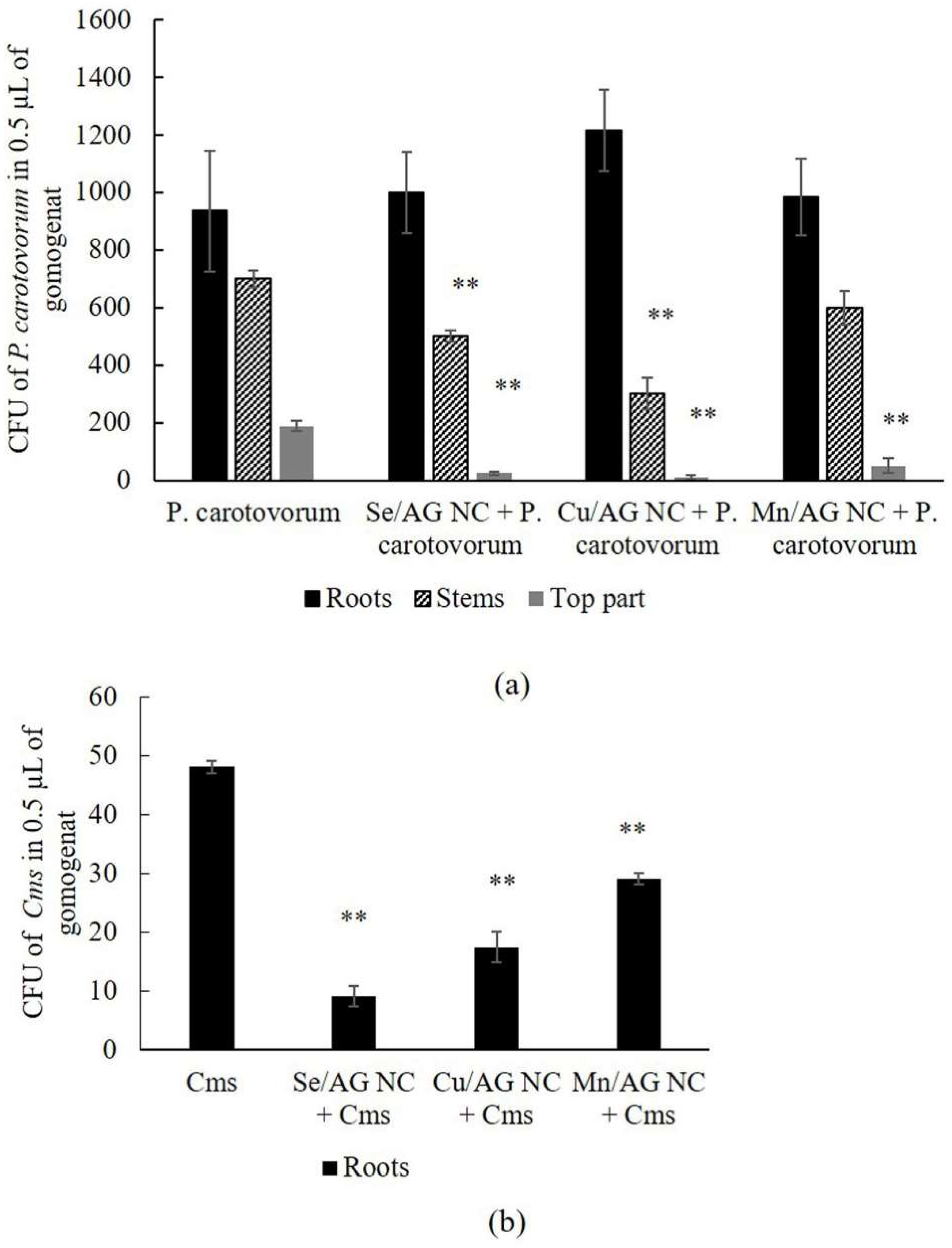

The effect of chemically synthesized nanocomposites (NCs) of selenium (Se/AG NC), copper oxide (Cu/AG NC) and manganese hydroxide (Mn/AG NC) based on the natural polymer arabinogalactan (AG) on the processes of growth, development and colonization of potato plants in vitro was studied upon infection with the causative agent of potato blackleg – the Gram-negative bacterium Pectobacterium carotovorum and the causative agent of ring rot – the Gram-positive bacterium Clavibacter sepedonicus (Cms). It was shown that infection of potatoes with P. carotovorum reduced root formation of plants and the concentration of pigments in leaf tissues. Treatment of plants with Cu/AG NC before infection with P. carotovorum stimulated leaf formation and increased the concentration of pigments in them. A similar effect was observed when potatoes were exposed to Mn/AG NC, and an increase in growth and root formation was also observed. Infection of plants with Cms inhibited plant growth. Treatment with each of the NCs mitigated this negative effect of the phytopathogen. At the same time, Se/AG and Mn/AG NCs promoted leaf formation. Se/AG NC increased the biomass of Cms-infected plants. Treatment of plants with NCs before infection showed a decrease in the intensity of colonization of plants by bacteria. The Se/AG NC had the maximum effect, which is probably due to its high antioxidant capacity. Thus, the NCs are able to mitigate the negative effect of bacterial phytopathogens on vegetation and the intensity of colonization by these bacteria during infection of cultivated plants.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Nanocomposites (NCs)

4.2. Potato Plants

4.3. Bacteria

4.4. Nanocomposite Treatment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayliffe, M.; Sørensen, C.K. Plant nonhost resistance: paradigms and new environments. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 50, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newbery, F.; Qi, A.; Fitt, B.D.L. Modelling impacts of climate change on arable crop diseases: progress, challenges and applications. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016, 32, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, I.K.; van der Wolf, J.M.; Saddler, G.; Lojkowska, E.; Hélias, V.; Pirhonen, M.; Tsror, L.; Elphinstone, J.G. Dickeya species: an emerging problem for potato production in Europe. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wolf, J.M.; Acuña, I.; De Boer, S.H.; Brurberg, M.B.; Cahill, G.; Charkowski, A.O.; Coutinho, T.; Davey, T.; Dees, M.W.; Degefu, Y.; Dupuis, B.; Elphinstone, J.G.; Fan, J.; Fazelisanagri, E.; Fleming, T.; Gerayeli, N.; Gorshkov, V.; Helias, V.; le Hingrat, Y.; Johnson, S.B.; Keiser, A.; Kellenberger, I.; Li, X.; Lojkowska, E.; Martin, R.; Perminow, J.I.; Petrova, O.; Motyka-Pomagruk, A.; Rossmann, S.; Schaerer, S.; Sledz, W.; Toth, I.K.; Tsror, L.; van der Waals, J.E.; de Werra, P.; Yedidia, I. Diseases Caused by Pectobacterium and Dickeya Species Around the World. In Plant Diseases Caused by Dickeya and Pectobacterium Species, Van Gijsegem, F., van der Wolf, J.M., Toth, I.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 215–261. [Google Scholar]

- Osdaghi, E.; van der Wolf, J.M.; Abachi, H.; Li, X.; De Boer, S.H.; Ishimaru, C.A. Bacterial ring rot of potato caused by Clavibacter sepedonicus: A successful example of defeating the enemy under international regulations. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 911–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, D.; Kaur, G.; Singh, P.; Yadav, K.; Ali, S.A. Nanoparticle-Based Sustainable Agriculture and Food Science: Recent Advances and Future Outlook. Front. nanotechnol. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Fraceto, L.F.; Amorim, M.J.B. Nano-pesticides: the lunch-box principle-deadly goodies (semio-chemical functionalised nanoparticles that deliver pesticide only to target species). J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rayeen, F.; Mishra, R.; Tripathi, M.; Pathak, N. Nanotechnology applications in sustainable agriculture: An emerging eco-friendly approach. Plant Nano Biology 2023, 4, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfileva, A.I.; Nozhkina, O.A.; Graskova, I.A.; Sidorov, A.V.; Lesnichaya, M.V.; Aleksandrova, G.P.; Dolmaa, G.; Klimenkov, I.V.; Sukhov, B.G. Synthesis of selenium and silver nanobiocomposites and their influence on phytopathogenic bacterium Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2018, 67, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfileva, A.I.; Moty’leva, S.M.; Klimenkov, I.V.; Arsent’ev, K.Y.; Graskova, I.A.; Sukhov, B.G.; Trofimov, B.A. Development of antimicrobial nano-selenium biocomposite for protecting potatoes from bacterial phytopathogens. Nanotechnologies in Russia 2017, 12, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graskova, I.A.; Perfileva, A.I.; Nozhkina, O.A.; Dyakova, A.V.; Nurminsky, V.N.; Klimenkov, I.V.; Sudakov, N.P.; Borodina, T.M.; Aleksandrova, G.P.; Lesnichaya, M.V.; Sukhov, B.G.; Trofimov, B.A. The effect of nanoscale selenium on the causative agent of ring rot and potato in vitro. Khimiya Rastitel'nogo Syr'ya 2019, 3, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfileva, A.I.; Nozhkina, O.A.; Graskova, I.A.; Dyakova, A.V.; Pavlova, A.G.; Aleksandrova, G.P.; Klimenkov, I.V.; Sukhov, B.G.; Trofimov, B.A. Selenium nanocomposites having polysaccharid matrices stimulate growth of potato plants in vitro infected with ring rot pathogen. Dokl. Biol. Sci. 2019, 489, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perfileva, A.I.; Nozhkina, O.A.; Ganenko, T.V.; Graskova, I.A.; Sukhov, B.G.; Artem’ev, A.V.; Trofimov, B.A.; Krutovsky, K.V. Selenium nanocomposites in natural matrices as potato recovery agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khutsishvili, S.S.; Perfileva, A.I.; Nozhkina, O.A.; Ganenko, T.V.; Krutovsky, K.V. Novel nanobiocomposites based on natural polysaccharides as universal trophic low-dose micronutrients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khutsishvili, S.S.; Perfileva, A.I.; Kon’kova, T.V.; Lobanova, N.A.; Sadykov, E.K.; Sukhov, B.G. Copper-containing bionanocomposites based on natural raw arabinogalactan as effective vegetation stimulators and agents against phytopathogens. Polymers 2024, 16, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfileva, A.I. The effect of iodoacetic acid sodium salt (pesticides-inhibitor of mitochondrions) on potatoes plants by the example of model system in vitro. Izvestiya Vuzov. Prikladnaya Khimiya i Biotekhnologiya (Proceedings of Universities. Applied Chemistry and Biotechnology) 2013, 1, 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, L.H.; Tom, J.Y.; van der Zouwen, P.S.; Mendes, O.; Poleij, L.M.; van der Wolf, J.M. Effect of temperature treatments on the viability of Clavibacter sepedonicus in infected potato tissue. Potato Res. 2021, 64, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Xu, Y.; Lin, L.; Sun, D.-W. Biofilm formation of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum on polypropylene surface during multiple cycles of vacuum cooling. IJFST 2021, 56, 3495–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryń, G.; Franke, K.; Nowakowski, M.M.; Nowakowski, M. Latent infection by Clavibacter sepedonicus and correlation with ring rot symptoms development in potato cultivars. Potato Res. 2021, 64, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Du, S.; Ma, L.; Liao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Toth, I.; Fan, J. Characterization of Pectobacterium carotovorum proteins differentially expressed during infection of Zantedeschia elliotiana in vivo and in vitro which are essential for virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.R.; Kariola, T.; Niemi, O.; Palva, T. Pathogenicity of and plant immunity to soft rot Pectobacteria. Frontiers in Plant Sci. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfileva, A.I.; Tsivileva, O.M.; Nozhkina, O.A.; Karepova, M.S.; Graskova, I.A.; Ganenko, T.V.; Sukhov, B.G.; Krutovsky, K.V. Effect of natural polysaccharide matrix-based selenium nanocomposites on Phytophthora cactorum and Rhizospheric microorganisms. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesnichaya, M.V.; Malysheva, S.F.; Belogorlova, N.A.; Graskova, I.A.; Gazizova, A.V.; Perfilyeva, A.I.; Nozhkina, O.A.; Sukhov, B.G. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of arabinogalactan-stabilized selenium nanoparticles from sodium bis(2-phenylethyl)diselenophosphinate. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2019, 68, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfileva, A.I.; Kharasova, A.R.; Nozhkina, O.A.; Sidorov, A.V.; Graskova, I.A.; Krutovsky, K.V. Effect of nanopriming with selenium nanocomposites on potato productivity in a field experiment, soybean germination and viability of Pectobacterium carotovorum. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, N.E.-A.; Bashir, S.I.; Rabei, N.H.; Saber, W.I.A. Innovative biosynthesis, artificial intelligence-based optimization, and characterization of chitosan nanoparticles by Streptomyces microflavus and their inhibitory potential against Pectobacterium carotovorum. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Fu, X.; Gao, Y.; Shi, L.; Liu, Q.; Yang, W.; Feng, J. Synthesis, antibacterial evaluation, and safety assessment of CuS NPs against Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, O.; Mohsin Baig, M.M.; Ikram, M.; Iqbal, T.; Islam, S.; Syed, W.; Al-Rawi, M.B.A.; Naseem, M. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles and study their anti-pathogenic properties against pathogens effect on plants and animals. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Altaf, M.; Robab, M.I.; Shahid, M.; Manoharadas, S.; Hussain, S.A.; Shaikh, H. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles mitigate biotic stress induced by meloidogyne incognita in Trachyspermum ammi (L.) by improving growth, biochemical, and antioxidant enzyme activities. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 11389–11403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ning, C.; Pan, T.; Cai, K. Role of Silica Nanoparticles in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Thounaojam, T.C.; Chowdhury, D.; Upadhyaya, H. The role of selenium and nano selenium on physiological responses in plant: a review. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, M.F.; Shahbaz, M.; Khalid, F.; Rasheed, Y.; Asif, K.; Naz, N.; Zulfiqar, U.; Zulfiqar, F.; Moosa, A.; Alamer, K.H.; Attia, H. Biogenic nanoparticles application in agriculture for ROS mitigation and abiotic stress tolerance: A review. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortella, G.; Rubilar, O.; Pieretti, J.C.; Fincheira, P.; de Melo Santana, B.; Fernández-Baldo, M.A.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Seabra, A.B. Nanoparticles as a promising strategy to mitigate biotic stress in agriculture. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, L.; Welchen, E.; Gonzalez, D.H. Mitochondria and copper homeostasis in plants. Mitochondrion 2014, 19, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fargašová, A. Toxicity comparison of some possible toxic metals (Cd, Cu, Pb, Se, Zn) on young seedlingsof Sinapis alba L. PSE. 2004, 50, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yruela, I. Copper in plants: acquisition, transport and interactions. Functional plant biology : FPB 2009, 36, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maithreyee, M.N.; Gowda, R. Influence of nanoparticles in enhancing seed quality of aged seed. MJAS 2015, 49, 310–313. [Google Scholar]

- Nekoukhou, M.; Fallah, S.; Pokhrel, L.R.; Abbasi-Surki, A.; Rostamnejadi, A. Foliar enrichment of copper oxide nanoparticles promotes biomass, photosynthetic pigments, and commercially valuable secondary metabolites and essential oils in dragonhead (Dracocephalum moldavica L.) under semi-arid conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasifar, A.; Shahrabadi, F.; ValizadehKaji, B. Effects of green synthesized zinc and copper nano-fertilizers on the morphological and biochemical attributes of basil plant. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 43, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodetskaia, T.A.; Fedorova, O.A.; Evlakov, P.M.; Baranov, O.Y.; Zakharova, O.V.; Gusev, A.A. Effect of copper oxide and silver nanoparticles on the development of tolerance to alternaria alternata in poplar in vitro clones. Nanobiotechnology Reports 2021, 16, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, O.; Grodetskaya, T.; Evtushenko, N.; Evlakov, P.; Gusev, A.; Zakharova, O. The impact of copper oxide and silver nanoparticles on woody plants obtained by in vitro method. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 875, 012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodetskaya, T.A.; Evlakov, P.M.; Fedorova, O.A.; Mikhin, V.I.; Zakharova, O.V.; Kolesnikov, E.A.; Evtushenko, N.A.; Gusev, A.A. Influence of copper oxide nanoparticles on gene expression of birch clones in vitro under stress caused by phytopathogens. Nanomaterials 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Luna, J.; Nopal-Hormiga, Y.; López-Sánchez, L.; Mtz-Enriquez, A.I.; Pariona, N. Effect of methods application of copper nanoparticles in the growth of avocado plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Zu, C.; Shen, J.; Shao, F.; Li, T. Effects of selenium on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of flue-cured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2015, 84, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.-A.A.; Darwesh, O.M.; Mekki, B.B.; El-Hallouty, S.M. Evaluation of cytotoxicity, biochemical profile and yield components of groundnut plants treated with nano-selenium. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Chen, S.S.; Gao, D.Q.; Liu, G.Q.; Bai, H.X.; Li, A.; Peng, L.X.; Ren, Z.Y. Selenium improves photosynthesis and protects photosystem II in pear (Pyrus bretschneideri), grape (Vitis vinifera), and peach (Prunus persica). Photosynthetica 2015, 53, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Geiser-Lee, J.; Deng, Y.; Kolmakov, A. Interactions between engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) and plants: Phytotoxicity, uptake and accumulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3053–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombuloglu, H.; Tombuloglu, G.; Slimani, Y.; Ercan, I.; Sozeri, H.; Baykal, A. Impact of manganese ferrite (MnFe2O4) nanoparticles on growth and magnetic character of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de França Bettencourt, G.M.; Degenhardt, J.; Zevallos Torres, L.A.; de Andrade Tanobe, V.O.; Soccol, C.R. Green biosynthesis of single and bimetallic nanoparticles of iron and manganese using bacterial auxin complex to act as plant bio-fertilizer. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, D.M.; Abd El-Aziz, M.E.; Osman, S.A.; Abd Elwahed, M.S.A.; Shaaban, E.A. Foliar spraying of MnO2-NPs and its effect on vegetative growth, production, genomic stability, and chemical quality of the common dry bean. Arab j. basic appl. sci. 2022, 29, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgueitio-Herrera, E.; Falconí, C.E.; Cumbal, L.; Gómez, J.; Yanchatipán, K.; Tapia, A.; Martínez, K.; Sinde-Gonzalez, I.; Toulkeridis, T. Synthesis of iron, zinc, and manganese nanofertilizers, using andean blueberry extract, and their effect in the growth of cabbage and lupin plants. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, P. Positive effects of metallic nanoparticles on plants: Overview of involved mechanisms. PPB. 2021, 161, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasote, D.M.; Lee, J.H.J.; Jayaprakasha, G.K. Manganese oxide nanoparticles as safer seed priming agent to improve chlorophyll and antioxidant profiles in watermelon seedlings. Nanomaterials 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunyemi, S.O.; Abdallah, Y.; Ibrahim, E.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, J.a.; Wang, F.; Ahmed, T.; Alkhalifah, D.H.M.; Hozzein, W.N.; Yan, C.; et al. Bacteriophage-mediated biosynthesis of MnO2NPs and MgONPs and their role in the protection of plants from bacterial pathogens. Front. microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xie, H.; Wang, P.; Yin, H. Nanoparticles in plants: uptake, transport and physiological activity in leaf and root. Materials 2023, 16, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentkowska, A.; Pyrzyńska, K. Antioxidant properties of selenium nanoparticles synthesized using tea and herb water extracts. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abideen, Z.; Hanif, M.; Munir, N.; Nielsen, B.L. Impact of Nanomaterials on the regulation of gene expression and metabolomics of plants under salt stress. Plants 2022, 11, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu Adjei, M.; Zhou, X.; Mao, M.; Xue, Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, H.; Luo, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, W.; Feng, L.; Ma, J. Magnesium oxide nanoparticle effect on the growth, development, and microRNAs expression of Ananas comosus var. bracteatus. J. Plant Interact. 2021, 16, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Wang, Y.; Samynathan, R.; Shariati, M.A.; Rebezov, M.; Nile, A.; Sun, M.; Venkidasamy, B.; Xiao, J.; et al. Nano-priming as emerging seed priming technology for sustainable agriculture—recent developments and future perspectives. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takehara, Y.; Fijikawa, I.; Watanabe, A.; Yonemura, A.; Kosaka, T.; Sakane, K.; Imada, K.; Sasaki, K.; Kajihara, H.; Sakai, S.; Mizukami, Y.; Haider, M.S.; Jogaiah, S.; Ito, S. Molecular analysis of MgO nanoparticle-induced immunity against fusarium wilt in tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, Y.; Liu, H.; Xin, H. Effect of different copper oxide particles on cell division and related genes of soybean roots. PPB 2021, 163, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, H.; Juárez-Maldonado, A.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Ortega-Ortiz, H.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Sánchez-Aspeytia, D.; González-Morales, S. Chitosan-PVA and copper nanoparticles improve growth and overexpress the sod and ja genes in tomato plants under salt stress. Agronomy 2018, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytešníková, Z.; Pečenka, J.; Tekielska, D.; Kiss, T.; Švec, P.; Ridošková, A.; Bezdička, P.; Pekárková, J.; Eichmeier, A.; Pokluda, R.; Vojtěch, A.; Richtera, L. Reduced graphene oxide-based nanometal-composite containing copper and silver nanoparticles protect tomato and pepper against Xanthomonas euvesicatoria infection. Chem. biol. technol. agric. 2022, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Vargas, E.R.; Ortega-Ortíz, H.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; De Alba Romenus, K.; Cabrera de la Fuente, M.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Foliar application of copper nanoparticles increases the fruit quality and the content of bioactive compounds in tomatoes. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Ullah, Z.; Iqbal, J.; Chalgham, W.; Ahmad, A. Aspartic acid-based nano-copper induces resilience in Zea mays to applied lead stress via conserving photosynthetic pigments and triggering the antioxidant biosystem. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidouri, S.; Karmous, I. Clue of zinc oxide and copper oxide nanoparticles in the remediation of cadmium toxicity in Phaseolus vulgaris L. via the modulation of antioxidant and redox systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 85271–85285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P.; Nadda, A.; Chaudhary, A.; Khati, P. Advances in nanotechnology for smart agriculture: Techniques and applications; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Tripathy, S.; Patra, C.R. Manganese-based advanced nanoparticles for biomedical applications: future opportunity and challenges. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 16405–16426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, H.; Cheheregani Rad, A.; Raza, A.; Djalovic, I.; Prasad, P.V.V. The comparative effects of manganese nanoparticles and their counterparts (bulk and ionic) in Artemisia annua plants via seed priming and foliar application. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Sun, R.; Lv, R.; Du, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, R.; Qi, Y. Multienzymatic antioxidant activity of manganese-based nanoparticles for protection against oxidative cell damage. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2022, 8, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zhu, Q.; Zeng, Y. Manganese oxide nanoparticles as mri contrast agents in tumor multimodal imaging and therapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 8321–8344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragg, R.; Schilmann, A.M.; Korschelt, K.; Wieseotte, C.; Kluenker, M.; Viel, M.; Völker, L.; Preiß, S.; Herzberger, J.; Frey, H.; Heinze, K.; Blümler, P.; Tahir, M.N.; Nataliof, F.; Tremel, W. Intrinsic superoxide dismutase activity of MnO nanoparticles enhances the magnetic resonance imaging contrast. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 7423–7428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Guan, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Manganese dioxide nanozymes as responsive cytoprotective shells for individual living cell encapsulation. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 13661–13665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, S.; Lin, S.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Wei, H. ROS scavenging Mn3O4 nanozymes for in vivo anti-inflammation. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2927–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khepar, V.; Ahuja, R.; Sidhu, A.; Samota, M.K. Nano-sulfides of Fe and Mn efficiently augmented the growth, antioxidant defense system, and metal assimilation in rice seedlings. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 30231–30238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanenko, A.S.; Riffel, A.A.; Graskova, I.A.; Rachenko, M.A. The role of extracellular ph-homeostasis in potato resistance to ring rot pathogen. J. Phytopathol. 1999, 147, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozen, N.J.M.; Van Vuurde, J.W.L. Development of a semi-selective medium and an immunofluorescence colony-staining procedure for the detection of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus in cattle manure slurry. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 1991, 97, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaginian, I.A.; Danilina, G.A.; Chernukha, M.; Alekseeva, G.V.; Batov, A.B. Biofilm formation by strains of Burkholderia cepacia complex in dependence of their phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. Zhurnal mikrobiologii, epidemiologii i immunobiologii 2007, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chazaux, M.; Schiphorst, C.; Lazzari, G.; Caffarri, S. Precise estimation of chlorophyll a, b and carotenoid content by deconvolution of the absorption spectrum and new simultaneous equations for Chl determination. TPJ 2022, 109, 1630–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | P. carotovorum | Cms |

|---|---|---|

| Infection | • reduction of root biomass | • decrease in plant growth rate |

| • reduction of pigment concentration | • decrease in pigment concentration | |

| NC Cu/AG + Infection | • stimulation of leaf formation during infection | • stimulation of plant growth intensity |

| • increase in pigment concentration | • increase in chlorophyll b concentration | |

| • reduction in CFUs of the phytopathogen in the apical and stem zone of plants | • reduction of CFU of phytopathogen in the root zone of plants | |

| NC Se/AG + Infection | • reduction of CFUs of phytopathogen in the apical and stem zone of plants | • reduction of pathogen phytotoxicity |

| • stimulation of plant growth intensity and leaf formation | ||

| • increase in biomass of fresh shoots and roots | ||

| • reduction of CFU of phytopathogen in the root zone of plants | ||

| NC Mn/AG + Infection | • reduction of pathogen phytotoxicity | • stimulation of plant growth rate and leaf formation |

| • stimulation of plant growth and leaf formation during infection | • increase in chlorophyll concentration | |

| • increase in root formation | ||

| • increase in the concentration of chlorophyll b and carotenoids | • reduction of CFU of phytopathogen in the root zone of plants | |

| • reduction in CFUs of the phytopathogen in the apical zone of plants |

| Treatment variant | Number of plants used for measuring biometric parameters taken daily for 7 days | Number of plants in the experiment to determine the intensity of colonization by the pathogen seeded two days after infection with the phytopathogen |

|---|---|---|

| Control (without infection and NC) | 5 | 3 |

| P. carotovorum | 5 | 3 |

| P. carotovorum + Se/АG NC | 5 | 3 |

| P. carotovorum + Mn/АG NC | 5 | 3 |

| P. carotovorum + Cu/АG NC | 5 | 3 |

| Cms | 5 | 3 |

| Cms + Se/АG NC | 5 | 3 |

| Cms + Mn/АG NC | 5 | 3 |

| Cms + Cu/АG NC | 5 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).