1. Introduction

Classic health-related quality of life (HRQOL) metrics used in spine surgery face several challenges that make them cumbersome and potentially biased [

1]. These instruments often carry biases, as they are typically developed from Western perspectives and may not translate well across diverse populations [

2]. Educational disparities can disadvantage respondents with lower literacy levels, while the lengthy and complex nature of these assessments can be burdensome for patients dealing with pain and mobility issues. Questions arise about the validity of these measures across different healthcare contexts and cultural practices [

3]. Many HRQOL instruments adopt a deficit-based approach, potentially missing important aspects of patients’ experiences. Additionally, generic measures may not adequately capture the specific concerns relevant to spine surgery patients [

4].

To address these issues, we advocate for developing more context-specific and strengths-based HRQOL measures that combine quantitative and qualitative methods for a more comprehensive assessment via natural language processing (NLP), specifically sentiment analysis [

5]. NLP converts free-form text, such as patient interview transcriptions, into quantitative metrics. Sentiment analysis is a type of NLP that enables subject matter experts to construct domain-specific lexicons to assign a value that is either negative (-1) or positive (1) to certain words [

6].

The growth of telehealth has provided opportunities to apply sentiment analysis to transcripts of adult spinal deformity patient visits to derive a novel and less biased HRQOL metric [

7]. The telehealth market is projected to reach

$791.04 billion by 2032 [

8]. This has led to a significant increase in digital patient-provider interactions, providing a wealth of textual data that offers a rich source for sentiment analysis. Additionally, this analysis can be done in real-time, potentially providing more accurate reflections of patients’ experiences with spinal deformity at home and day-to-day, rather than responses influenced by the clinical setting [

6,

9].

We demonstrate the feasibility of constructing a spine-specific lexicon for sentiment analysis to derive a HRQOL metric for an adult spinal deformity patient from the transcript of their preoperative telehealth visit. Our study asks 7 open-ended questions about spinal conditions, treatment, and quality of life to twenty-five (25) adult patients during telehealth visits. Using our domain-specific lexicon, sentiment analysis is performed on the transcripts to produce a HRQOL. The Pearson correlations among our sentiment analysis HRQOL metric and established HRQOL metrics (SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI) are statistically significant and range between 0.43 and 0.74.

The remainder of our paper is organized as follows. First, we provide background detail related to sentiment analysis and established HRQOL metrics (SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI). Then we review related research. Next, we describe the data collected in our study. Following that, we describe our domain-specific lexicon and how it is applied to the data to yield a HRQOL metric for an adult spinal deformity. Then, we present our approach to validating the lexicon. Finally, we present the results and discuss avenues for future research.

2. Background

2.1. Sentiment Analysis

Sentiment analysis has become valuable in healthcare research, particularly for understanding patients’ experiences [

10]. This method analyzes text data to gain insights into patients’ quality of life (positive sentiment) and lack of quality of life (negative sentiment) [

10,

11]. The most successful applications of sentiment analysis to patient interviews employ domain-specific lexicons [

12]. Domain-specific lexicons leverage subject matter expertise to account for contextual nuances in the field in which they are applied [

13]. By leveraging this technique, researchers can gain deeper insights into patient experiences, potentially informing improvements in care delivery and communication strategies for patients [

6,

14,

15].

2.2. Conventional HRQOL Metrics

2.2.1. Oswestry Disability Index

The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) is a widely used patient-reported outcome measure that assesses functional disability related to low back pain [

16]. The ODI consists of 10 sections that assess different aspects of daily living affected by low back pain including: pain intensity, personal care, lifting, walking, sitting, standing, sleeping, sex life, social life, and traveling. Each section is scored from 0-5, with higher scores indicating greater disability. The total score is calculated as a percentage, ranging from 0% (no disability) to 100% (maximum disability). Scores are typically interpreted as follows: (0-20%) - Minimal disability; (21-40%) Moderate disability; (41-60%) - Severe disability; (61-80%) Crippled; (81-100%) Bed-bound or exaggerating symptoms [

17]. The questionnaire is self-administered by patients and takes about 3-5 minutes to complete. It can be delivered in paper, telephone, SMS, or web-based formats. The ODI has demonstrated good reliability, validity, and responsiveness across numerous studies. However, some research suggests it may be multidimensional rather than unidimensional [

18].

2.2.2. 36-Item Short Form Health Survey

The SF-36 (36-Item Short Form Health Survey) is a widely used patient-reported outcome measure that assesses health-related quality of life across various populations, including both healthy individuals and those with medical conditions [

19]. It is used in clinical practice, research, health policy evaluations, and general population surveys [

20,

21,

22]. The SF-36 assesses eight health concepts or domains: (1) physical functioning, (2) role limitations due to physical health problems, (3) bodily pain, (4) general health, (5) vitality (energy/fatigue), (6) social functioning, (7) role limitations due to emotional problems, and (8) mental health (psychological distress and well-being). Additionally, it includes a single item that indicates perceived change in health. Each domain is scored on a 0-100 scale, with higher scores indicating better health status [

19]. Physical component and mental component summary scores can be calculated. The scoring involves recoding item responses and averaging items within each scale. The SF-36 is self-administered by patients or can be administered by a trained interviewer in person or by telephone. It typically takes about 5-10 minutes to complete and has demonstrated good reliability and validity across various populations. Specifically, it has shown high internal consistency, good construct validity, and responsiveness to changes in health status [

22].

2.2.3. Scoliosis Research Society-22

The SRS-22 (Scoliosis Research Society-22) is a patient-reported outcome measure specifically designed to assess health-related quality of life in individuals with scoliosis [

23]. It assesses five domains: (1) function/activity; (2) pain; (3) self-image/appearance; (4) mental health; and (5) satisfaction with management. It is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1-5), with higher scores indicating better outcomes. Domain scores are calculated by averaging the scores of the items within each domain. Scores range from 1 to 5 for each domain and the total score, with 5 representing the best possible outcome. A total score can be calculated by averaging all domain scores [

24].

The questionnaire is self-administered by patients and completion time is typically 5-10 minutes. The SRS-22 has demonstrated good reliability, validity, and responsiveness in various studies across different languages and cultures. It has been translated into multiple languages, with validated versions available in several countries [

25,

26,

27].

2.3. Related Research

The field of spine surgery and adult spinal deformity (ASD) research has evolved significantly in recent years, with efforts to complement traditional outcome measures such as the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22), and Short Form-36 (SF-36) with more comprehensive and diverse metrics. This review explores several innovative approaches in this area of research.

These efforts collectively reflect a shift towards innovative inclusive, precise, and patient-centered outcome measures in spine surgery research. By complementing traditional measures with newer instruments and methodologies, researchers aim to gain a more comprehensive understanding of patient outcomes and treatment effectiveness, ultimately leading to improved patient care and clinical decision-making.

2.3.1. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

A significant advancement in the field is the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), which offers a comprehensive, adaptive testing approach that correlates well with existing measures while reducing respondent burden [

28,

29]. PROMIS utilizes computer adaptive testing (CAT) to tailor questions to each individual, typically requiring only 4-12 items that can be completed in under a minute [

30]. The PROsetta Stone Project further enhances PROMIS by providing crosswalks between legacy measures and PROMIS scores, facilitating comparisons across different studies and instruments [

31]. PROsetta Stone has developed links for various domains including depression, anxiety, physical function, pain, fatigue, and global health, creating crosswalks between PROMIS and widely used instruments such as SF-36, Brief Pain Inventory, CES-D, MASQ, FACIT-Fatigue, GAD-7, HOOS/KOOS, ODI, and PHQ-916 [

32]. This approach allows for more efficient and precise measurement of patient-reported outcomes across a wide range of health domains.

2.3.2. Minimal Clinically Important Difference Values

Researchers have also focused on making outcome measures more meaningful and clinically relevant. The incorporation of Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) values for various instruments helps interpret score changes in terms of their clinical significance rather than just statistical significance [

33]. Additionally, alternative administration methods, such as phone-based questionnaires, have been validated to improve data collection and reduce loss to follow-up [

34]. There is also a growing trend towards using condition-specific measures, exemplified by the validation of SRS-22 for adult spinal deformity, which was originally designed for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis [

35]. This approach aims to capture aspects of health-related quality of life that might be missed by generic instruments. Furthermore, researchers are increasingly adopting a comprehensive assessment strategy, using combinations of measures to provide a more holistic view of patient outcomes.

2.3.3. Innovative Approaches to Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL)

Recent research has demonstrated innovative approaches to health-related quality of life (HRQOL) assessment using advanced technologies and methodologies. These studies showcase the potential of natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning techniques to analyze diverse data sources for HRQOL insights. The AI-PREM pipeline analyzes open-ended questionnaire responses [

36], while Torén et al. combined disease-specific and generic HRQOL measures for a more comprehensive assessment in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis [

37]. Another study utilized deep learning models to extract HRQOL trajectories from transcribed patient interviews, comparing results with traditional survey-based measures [

38]. Another effort explored the use of large language models for sentiment analysis of health-related social media data [

39]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the growing potential for automated analysis of unstructured text data to provide richer, more nuanced insights into patient experiences and outcomes, complementing or potentially replacing traditional questionnaire-based methods in HRQOL assessment.

2.3.4. Telehealth in Spine Care

Recent studies have highlighted the increasing adoption of telehealth in spine care, particularly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic [

40]. One study reported a dramatic rise in telemedicine usage for spine consultations, from less than 7% to over 60% during the pandemic. The panel concluded that video-based telemedicine could effectively evaluate patients for common spine issues like lumbar stenosis and disc herniation, thereby reducing the need for long-distance travel [

41]. A retrospective study found that 24.3% of patients had changes in their treatment plans after in-person evaluations following initial telemedicine consultations, with longer intervals between visits correlating with a higher likelihood of plan changes [

42]. Additionally, a cross-sectional survey revealed that telemedicine usage increased from under 10% to over 39% during the pandemic, with a majority of providers finding it easy to use and agreeing that it was suitable for imaging reviews, initial appointments, and postoperative care. However, most surgeons still preferred at least one in-person visit before surgery. These findings underscore the potential benefits and ongoing evolution of telehealth in spine care [

43].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Creating the Open Ended Interview Questions

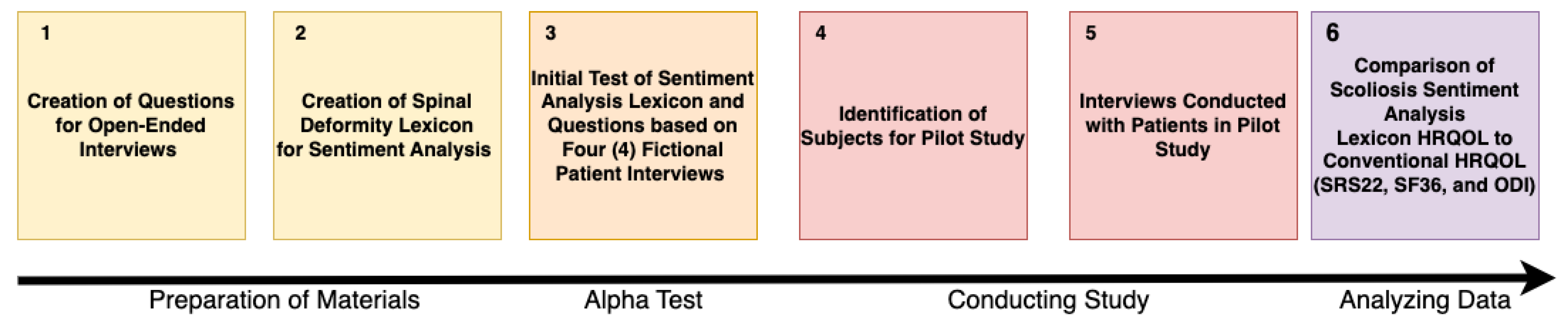

An overview of our study is presented in Figure

Figure 1, illustrating the progression from the preparatory phase to data analysis, which ultimately yields the results for our conclusions. Initially, we identified seven open-ended questions for our interviews with patients. These questions were generated by authors MMS and CPA, who each brainstormed an initial set of open-ended questions regarding patients’ spinal conditions, treatment, and quality of life during telehealth visits. The two then met to identify common questions from their proposals and discussed any drawbacks associated with questions proposed by one author but not the other. Ultimately, they reached a consensus on the seven questions listed below. It is important to note that while this process leverages a combined twenty years of clinical experience in spinal deformity, it is unlikely that such a process would yield effective interview questions for individuals with little to no experience in this field. This follows best practices identified in [

44,

45,

46]. These questions are also provided in the data and source code repository for the paper [

47].

How does your spinal condition affect your daily life?

How does your condition affect your family?

How does your condition affect your income or ability to work?

How does your condition affect your ability to enjoy life?

What you hope to gain from surgery?

What are your fears regarding treatment of your condition?

Do you feel optimistic and lucky or do you feel pessimistic and unlucky?

3.2. Creating the Domain Specific Lexicon

Next, authors RJG and CJL collaborated with MMS to create the lexicon. This process began with an initial presentation by RJG and CJL to MMS regarding the characteristics of terms in a domain-specific lexicon for sentiment analysis that effectively separates signal from noise. They highlighted that MMS needed to identify terms that had: (1) relevance to the spinal deformity domain, (2) strong sentiment indicators, (3) unambiguous meanings, and (4) moderate to high frequency of use. Following this presentation, MMS identified terms likely to be included in patients’ responses to questions indicating positive (+1) or negative (-1) quality of life. These terms formed the Spinal Deformity Lexicon used in the study. The complete lexicon can be found at [

47]. Examples of positive terms include: accomplish, improving, supportive, trust, encouragement, and independent. Examples of negative terms include: medication, reliant, oxycodone, methadone, disability, and pain. A comparison of the number of positive and negative terms in the Spinal Deformity Lexicon relative to other established sentiment analysis lexicons (AFINN, BING, and NRC) is shown in

Table 2. These lexicons differ in their approaches to sentiment analysis. The AFINN lexicon, developed by Finn Arup Nielsen, assigns sentiment scores to words ranging from -5 (most negative) to +5 (most positive) [

48]. It was initially based on tweets related to the UN Climate Conference. The BING lexicon, created by Minqing Hu and Bing Liu, takes a binary approach, classifying words as either positive or negative, and was designed for analyzing e-commerce customer reviews [

49]. The National Research Council of Canada (NRC) Emotion Lexicon provides a more comprehensive approach by associating words with eight basic emotions (anger, fear, anticipation, trust, surprise, sadness, joy, and disgust) and two sentiments (negative and positive), making it valuable for nuanced emotion detection tasks in text analysis [

50].

Table 1.

Comparison of our lexicon to other alternatives.

Table 1.

Comparison of our lexicon to other alternatives.

| Lexicon |

# of Positive Words |

# of Negative Words |

# of Total Words |

| Spinal Deformity Lexicon |

114 |

109 |

223 |

| AFINN [48] |

878 |

1,598 |

2,476 |

| BING [49] |

2,007 |

4,781 |

6,788 |

| NRC [50] |

2,317 |

3,338 |

5,655 |

Initially, it may be concerning that our lexicon includes an order of magnitude fewer terms than more general sentiment analysis lexicons such as AFINN [

48], BING [

49], and NRC [

50]. However, we consider this a strength of our approach.

Our lexicon is tailored to capture sentiment-bearing words that are particularly relevant and frequently used within the context of spinal deformities and the responses to our seven open-ended questions. This focused approach results in a more compact lexicon, as it excludes terms that may be sentiment-laden in general language but are irrelevant or neutral in our specific domain [

51]. Furthermore, we constructed our lexicon to exhibit higher precision in sentiment classification for the responses to our open-ended questions. By concentrating on this set of highly relevant terms, our lexicon can more accurately capture the nuanced sentiments expressed in domain-specific texts [

52]. This precision is particularly valuable because some words in our lexicon may have different or even opposite sentiment polarities in other contexts. For instance, the word "exceeding" might be negative when referring to surpassing a legal limit; however, in our lexicon, it indicates improved quality of life [

53].

Finally, we applied lemmatization to the lexicon. This reduces each inflected word in the lexicon to its base form and ensures that different variations of the same word are treated consistently. For example, in our lexicon, words like "pains", "pained", and "painful" are reduced to the lemma "pain". Similarly, verb forms like "improving", "improved", and "improves" are all lemmatized to "improve". This process helps capture the true sentiment more accurately across different word forms and tenses used by patients. It also enables the lexicon to match a wider range of word variations in patient responses to the core concepts, increasing its coverage and applicability across diverse patient expressions. We performed this analysis using the

R package

textstem [

54]. We chose not to stem any of the words in our lexicon to avoid instances where stemming produces non-words or conflates terms with different meanings. For example, "organization" and "organ" might be reduced to the same stem, potentially altering the sentiment interpretation [

55]. Additionally, we did not use Named Entity Recognition (NER) to create our lexicon. While NER systems are designed to identify and classify named entities like people, organizations, and locations, they do not inherently capture the sentiment associated with these entities [

56] and these entities did not appear in the text of any our patient interview questions. For this reason, we chose not to employ NER, focusing instead on maintaining the integrity and accuracy of sentiment analysis in our specific context.

3.3. Scoring the Lexicon

Recall that our lexicon assigns a score of +1 to positive terms and -1 to negative terms included in a patient’s answer. However, when scoring a patient’s entire response to a question, we incorporate valence and negation scoring to enhance the depth and accuracy of sentiment analysis. Valence scoring refers to the intensity or strength of the sentiment expressed by a word. For example, without valence shifting the two sentences below would each receive a sentiment score of -1:

Each sentence would initially receive a score of -1 because it contains two terms (weak, burden) from our lexicon, both of which are negative.

The application of valence shifting allows for a more precise measurement of sentiment intensity in these sentences by distinguishing between mild and strong sentiments. When scored with valence shifting, the sentiment of the first sentence becomes -0.8165, while the second sentence becomes -1.5556. Negation scoring works similarly by handling words or phrases that reverse or nullify the sentiment of surrounding terms, effectively flipping the sentiment of the resulting phrase. For example, if the first sentence were rewritten as ’I am neither weak nor a burden,’ the resulting sentiment would be positive.

Specifically, we use the

R package

sentimentr to implement our lexicon, valence shifting and negation [

57].

sentimentr employs a rule-based approach to handle valence shifters and negation, considering four types: negators, amplifiers, de-amplifiers, and adversative conjunctions. The package analyzes words in polarized context clusters around sentiment-bearing words, typically examining 4 words before and 2 words after. Negation handling in

sentimentr is implemented based on the number of negators in a cluster, with an odd number reversing polarity and an even number canceling out the negation effect. It also applies weights to amplifiers and de-amplifiers, considering their interaction with negators, and uses adversative conjunctions to identify contrasting sentiments within a sentence. This approach enables a more nuanced, rule-based handling of valence shifters and negation compared to other popular libraries such as

spaCy [

58] and

cTakes [

59].

spaCy analyzes sentiment at the token level, without the complex context clustering. While

cTakes has a strong focus on negation detection, particularly for medical concepts extracted from Electronic Medical Records (EMRs), it does not handle the full range of valence shifters that

sentimentr does. Moreover, our data comes from patient interviews, not EMRs. The position encoding and valence shifting logic performed by

sentimentr could be implemented in

spaCy, but it is not available by default and would need to be created as a custom pipeline. In future work, we will explore implementing this capability for our lexicon.

3.4. Initial Test of the Lexicon on Fictional Patient Responses

We conducted an initial test of our lexicon before applying it in our pilot study. In this test, CPA, who had not yet interacted with the lexicon, wrote answers to each of the questions based on his experience with patients who had specific SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI scores. The scores for four fictional patients were detailed, with each metric measured on a scale from 0 to 100. For the SRS-22 and SF-36, higher scores indicate more mobility and function, while for the ODI, lower scores indicate less mobility and function. To simplify interpretation, we present the 1-ODI score to align with the SRS-22 and SF-36.

The responses that CPA wrote to the open-ended questions for these fictional patients are available in the dataset provided at [

47]. This dataset aims to facilitate the sharing, management, and discovery of materials supporting this study. This initial test served as a validation step for our lexicon, ensuring its applicability and effectiveness before implementation in the pilot study. By using fictional patients with specific scores, we were able to assess how well the lexicon captured the nuances of patient experiences across different levels of mobility and function.

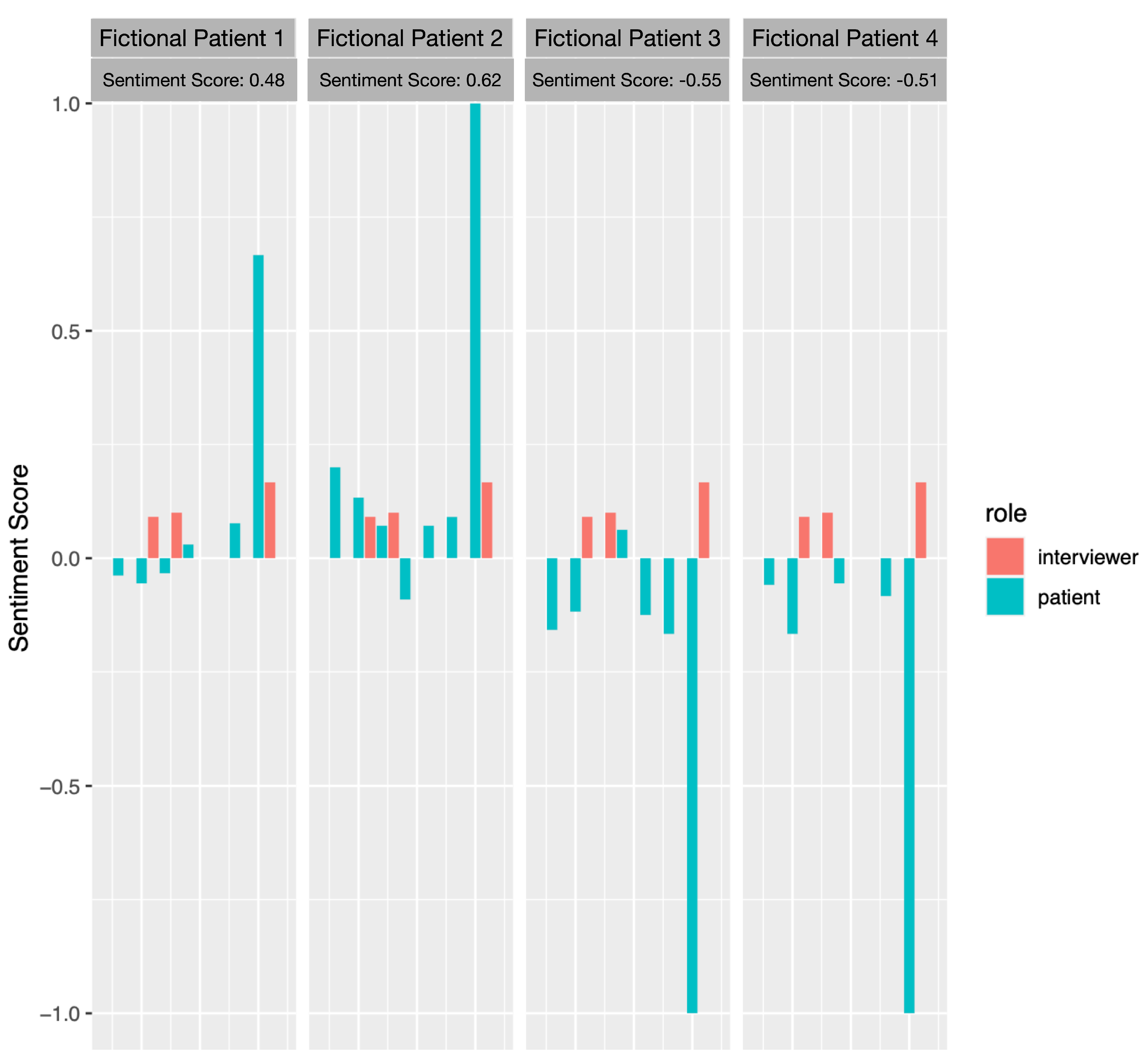

Next, we conducted sentiment analysis using our domain-specific lexicon on each response to every question for each of the fictional patients. The results of this analysis, along with the average sentiment for each patient during the interview, are shown in

Figure 2. Each facet in

Figure 2 represents a different fiction patient. From left to right these patients are: Fictional Patient 1 (SRS-22/SF-36: 0.6, ODI: 0.4); Fictional Patient 2 (SRS-22/SF-36: 0.8, ODI: 0.2); Fictional Patient 3 (SRS-22/SF-36: 0.2, ODI: 0.8); Fictional Patient 4 (SRS-22/SF-36: 0.4, ODI: 0.6). Within a facet each bar represents the sentiment score for a specific question asked to a fictional patient. The x-axis shows the question number (Q1 through Q7), while the y-axis represents the sentiment score calculated using the spinal deformity lexicon. The bars are color-coded to distinguish the sentiment of the patient’s response (in blue) from the sentiment of the interviewer’s questions in red. The height of each bar indicates the sentiment score for that particular question and patient. Positive scores (above 0) indicate a more positive sentiment. Negative scores (below 0) indicate a more negative sentiment. The magnitude of the score represents the strength of the sentiment.

Figure 2 demonstrates initial success in our application of the domain-specific lexicon to the interview questions for this initial test on fictional patients. The sentiment scores achieved by applying our approach across all responses rank the mobility and function of the patients in the same order as the SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI scores. Patients who express, on average, the most negative sentiment have the least mobility and function (lowest SRS-22 and SF-36 scores; highest ODI score). Similarly, patients who express, on average, the most positive sentiment have the most mobility and function (highest SRS-22 and SF-36 scores; lowest ODI score). This result was not guaranteed; recall that CPA had not seen or interacted with our lexicon when he created the responses to the interview questions from the fictional patients. Furthermore, our results indicate that there is nuance in our lexicon, as it was able to differentiate between patients with very low mobility and function (SRS-22/SF-36: 0.2; ODI: 0.8) and those with moderately low mobility and function (SRS-22/SF-36: 0.4; ODI: 0.6).

Figure 2 illustrates the ability of the lexicon to distinguish between patients with very high mobility and function (SRS-22/SF-36: 0.8; ODI: 0.2) and those with moderately high mobility and function (SRS-22/SF-36: 0.6; ODI: 0.4). While these results do not validate our lexicon, it allows us to determine that the lexicon can accurately capture and differentiate between varying levels of mobility and function in patients with spinal deformities. In addition, the test examined whether the sentiment scores derived from the lexicon aligned with the conventional HRQOL metrics (SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI) for fictional patients. It is important to note that the fictional patients’ responses were created by CPA who had not interacted with the lexicon, ensuring an unbiased test of its capabilities.

3.5. Evaluation of the Lexicon

Next, we evaluated the lexicon on twenty-five patients. An overview of the patients’ gender and age is shown in

Table 3. Of the 25 patients, 19 were men and 6 were women. The men were slightly younger with more variance in their age than the women. Overall, the total sample was older.

Each patient completed the open-ended questions in an interview setting. The audio transcriptions of the interviews were converted to text and scored using a spinal-specific lexicon. Afterward, we administered the questionnaires associated with the SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI measures. We preprocessed all these metrics for the patients to ensure they were directionally aligned (i.e., the higher the score, the better the quality of life).

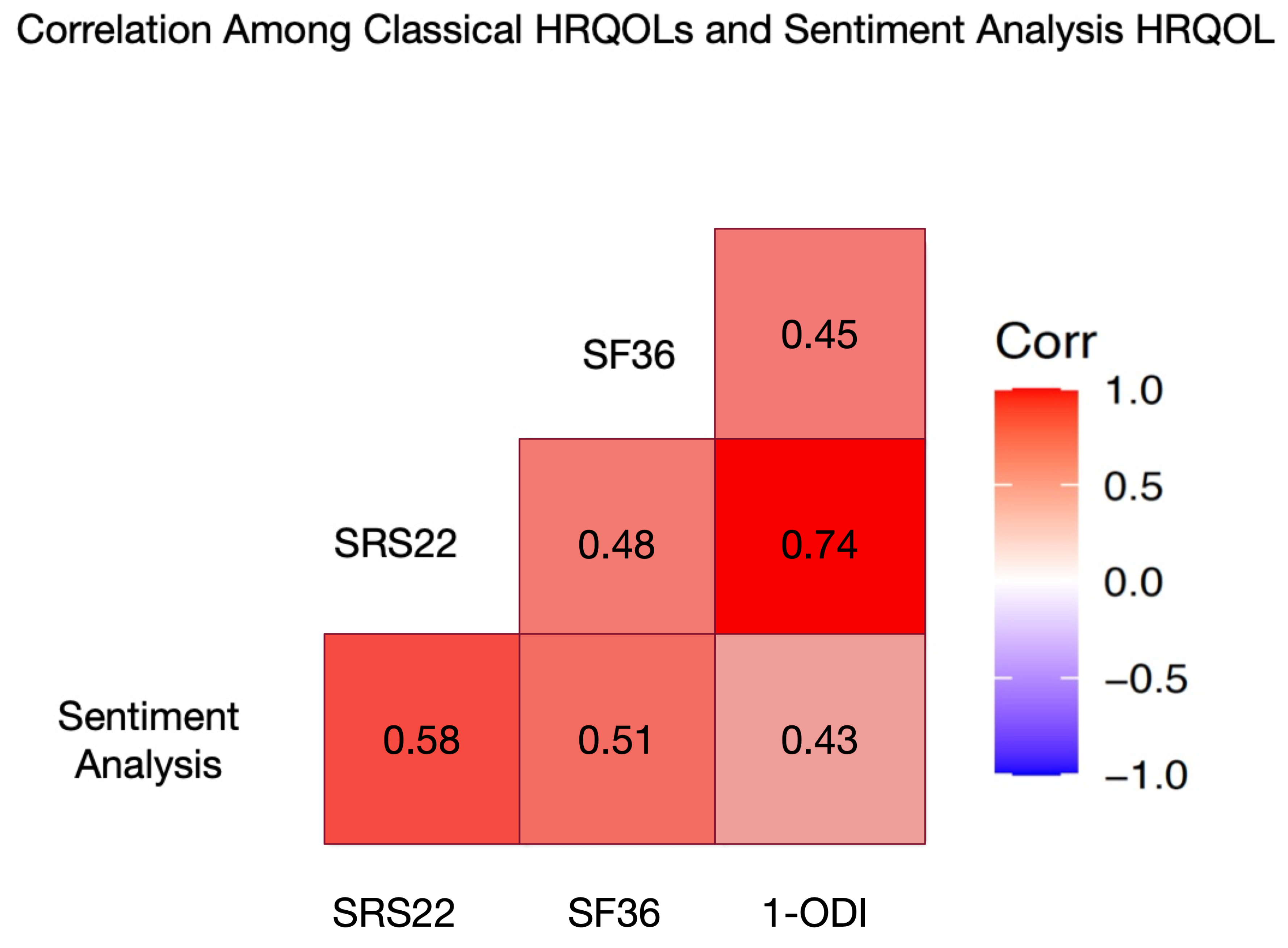

Using this data, we analyzed the Pearson correlation among: (1) our sentiment analysis HRQOL metric derived from transcripts of preoperative telehealth visits, and (2) the SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI metrics for those patients. The results of this analysis are shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows the Pearson correlation matrix for the conventional HRQOL metrics (SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI) and our sentiment analysis HRQOL metric derived from applying our spinal-specific lexicon to the interview responses of the of 25 patients to the seven open-ended questions.

The p-value and Bonferroni-adjusted p-value of our sentiment analysis metric in relation to each of the conventional HRQOL metrics is shown in

Table 4. We include the Bonferroni-adjusted p-value due to comparing our sentiment analysis HRQOL metric with the three conventional HRQOL metrics. The Bonferroni correction controls the probability of making at least one Type I error among all three of the hypothesis tests [

60]. Scoring the responses to all seven questions using sentiment analysis from our spinal-specific lexicon demonstrated statistically significant p-values (p < 0.05) and a medium Cohen’s effect size (0.2 – 0.8) with the conventional HRQOL metrics. The lowest correlation was 0.43 (ODI), while the highest was 0.58 (SRS-22). In addition, the only Conventional HRQOL that had a Bonferroni-adjusted p-value that was not statistically significant was 1-ODI. Overall, this data indicates a positive linear relationship between our sentiment analysis metric and the conventional HRQOL metrics.

Furthermore, all metrics demonstrate correlations with a medium effect size with one another. Specifically, none of the correlations among the HRQOL measures were less than 0.2 or greater than 0.8. This provides additional evidence that our sentiment analysis HRQOL metric is as effective as the conventional HRQOL metrics.

To further validate the effectiveness of our sentiment analysis HRQOL metric (SA) compared to conventional HRQOL metrics, we employed Steiger’s Z-test for Dependent Correlations [

61]. This statistical method enables us to compare pairs of correlations that share a common variable, allowing us to determine if there are statistically significant differences in strength between them. By using this test, we can assess whether our sentiment analysis approach performs comparably to traditional HRQOL metrics in measuring health-related quality of life. This approach has been used in other medical studies with similar contexts [

62,

63].

We applied Steiger’s Z-test for Dependent Correlations to every pair of correlated HRQOL measures in our study. For each application, we utilized three pairs of correlations among the HRQOL measures. For example, to determine if there is a statistically significant difference between the correlations of SRS-22 and our sentiment analysis (SA) HRQOL metric with a common variable, we used the SF-36 measure as the common variable. This approach allows us to compare the strength of the correlations between SRS-22 and SF-36 versus SA and SF-36, while accounting for the fact that these correlations are not independent since they share SF-36 as a common variable.

Specifically, we provide as input to Steiger’s Z-test all of the following: (1) the correlation between SRS-22 and SA (

), (2) the correlation between SRS-22 and SF-36 (

), and (3) the correlation between SA and SF-36 (

). Using this data Steiger’s Z-test computes a p-value that indicates indicates the probability of obtaining the observed difference between (

) and (

) by chance, if there was actually no true difference between them in the population. We consider there to be no true difference between a given pair of correlations if

. Since we are performing six tests we also report the Bonferroni-adjusted p-value for each pair of correlations. Recall, this correction controls the probability of making at least one Type I error among all six hypothesis tests in

Table 5 [

60].

The results are shown in

Table 5. In all but two cases, the resulting p-value of the comparison between the pairs of correlations is greater than 0.05. This provides evidence that there are no statistically significant differences among most pairs of correlations between HRQOL measures. The only exceptions are that there is a stronger correlation between SRS-22 and 1-ODI than between: (1) SA and 1-ODI, and (2) SF-36 and 1-ODI. In all other cases, each HRQOL measure, including the sentiment analysis HRQOL measure derived from applying our spinal deformity lexicon, appears to be an acceptable alternative to the others. We discuss these findings further in

Section 4.

4. Discussion

Our study provides evidence that applying NLP techniques to patient transcripts can yield effective HRQOL metrics. The resulting HRQOL metric from our study is statistically significantly correlated with conventional HRQOL metrics (SRS-22, SF-36, and ODI), with the effect size of the correlation (i.e., medium) comparable to the effect sizes of correlations among the conventional metrics themselves.Furthermore, our spinal deformity lexicon-driven approach showed statistically significant strong correlations among most pairs of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) measures. In almost all cases these results hold even when the Bonferroni-adjustment to the p-values is applied.

However, there were two exceptions: (1) the correlation between SRS-22 and 1-ODI was stronger than the correlation between our sentiment analysis HRQOL and 1-ODI and (2) and the correlation between our our sentiment analysis HRQOL and 1-ODI was not statistically significant when the Bonferroni-adjustment to the p-value was applied. One possible explanation for these exceptions is that ODI primarily focuses on low back pain and related functional limitations. While relevant for some spinal deformity patients, it may not capture the full spectrum of issues faced by this population. Specifically, ODI does not address psychosocial aspects like body image and self-esteem, which are particularly important for some patients with spinal deformities and are reflected in terms in our lexicon [

64,

65].

4.1. Limitations

It is important to highlight some limitations of our approach. First, this pilot study was performed on only 25 patients, who are predominantly female and older. The results are more susceptible to sampling error, leading to reduced reliability of sentiment scores and a risk of overfitting to specific characteristics of the sample group. These factors affect the generalizability of our findings. To improve this research, future studies should use larger, more diverse patient samples to create more comprehensive and generalizable lexicons, providing further validation.

Second, our lexicon-based approach to sentiment analysis, despite the application of valence shifting and negation, has inherent limitations. It may miss some context-dependent nuances and sarcasm, and will need periodic updates to accommodate evolving language relevant to the open-ended questions in our interview.

More complex machine learning and deep learning models could potentially capture these subtleties better, but at the cost of increased complexity and reduced interpretability. Our sentiment analysis metric, however, offers transparency and modifiability. These characteristics make it accessible for spinal deformity subject matter experts and quick to deploy in clinical settings.

Additionally, a more sophisticated statistical approach could provide further insights. A generalized linear model (GLM) incorporating demographic factors (e.g., education) and sentiment analysis scores as independent variables would offer a more robust method to evaluate the relationship between established metrics and the new sentiment analysis approach. Adjusting for these demographic factors would increase the internal validity of the study by reducing the impact of potential confounding variables. However, implementing this approach with our current sample size would limit the statistical power of a GLM, leading to unreliable estimates. For future research, we will explore collecting more detailed demographic data, including educational level, from a larger sample of patients. We can then use a GLM or similar multivariate approach to analyze the relationships between sentiment analysis scores, established metrics, and demographic factors.

4.2. Future Work

This study serves as a proof of concept for creating a domain-specific sentiment lexicon and provides a methodological framework that can be expanded upon in future work. Researchers in different medical specialties can use this study as a template for developing domain-specific lexicons and applying sentiment analysis to patient interviews. The process of creating a specialized lexicon, as detailed in the study, could be replicated for oncology, cardiology, neurology, and orthopedics. We are also planning a longitudinal study to examine how sentiment analysis scores correlate with patient outcomes over time. This study will involve: (1) collecting sentiment analysis scores at multiple timepoints (e.g., pre-surgery, immediately post-surgery, 3 months post-surgery, 1 year post-surgery); (2) tracking clinical outcomes like pain levels, functional status, and quality of life measures at the same timepoints; and (3) analyzing whether initial sentiment scores predict later clinical outcomes. This longitudinal approach will provide valuable insights into the predictive power of sentiment analysis in clinical settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.A., M.M.S, and R.G.; methodology, C.P.A., M.M.S, and R.G.; software, R.G., and C.J.L.; validation, R.G., C.J.L. and, M.M.S; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.; writing—review and editing, C.J.L, M.M.S, and C.P.A.; visualization, R.G., and C.J.L.; supervision, C.P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California San Francisco (Study # 19-27970 and 12/2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The open-ended questions in our study, the domain specific lexicon for spinal deformity that is paired with the questions, the fictional patient responses that were used to alpha test our domain, and the source code used to conduct the analysis are located online in a Mendeley Data repository [

47]. Unfortunately, we are unable to share the actual patients responses due to IRB restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Administrative, technical support, and materials used for experiments and analysis were provided by University of California San Francisco, and Old Dominion University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HRQOL |

Health-Related Quality of Life |

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| ODI |

Oswestry Disability Index |

| SF-36 |

36-Item Short Form Health Survey |

| SRS-22 |

Scoliosis Research Society-22 |

| ASD |

Adult Spinal Deformity |

| PROMIS |

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System |

| MCID |

Minimal Clinically Important Difference |

| AI-PREM |

Artificial Intelligence Patient-Reported Experience Measure |

| SA |

Sentiment Analysis HRQOL metric |

| CES-D |

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| MASQ |

Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire |

| FACIT |

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy |

| GAD7 |

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale |

| HOOS |

Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score |

| KOOS |

Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score |

| PHQ-9 |

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| EMR |

Electronic Medical Records |

| NER |

Name Entity Recognition |

| AFINN |

Sentiment Analysis Lexicon created by Finn Arup Nielsen |

| BING |

Sentiment Analysis Lexicon created by Minqing Hu and Bing Liu |

| NRC |

NRC (National Research Council Canada) Word-Emotion Association Lexicon |

References

- Acquadro, C.; Conway, K.; Hareendran, A.; Aaronson, N.; Issues, E.R.; of Life Assessment (ERIQA) Group, Q. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value in Health 2008, 11, 509–521.

- Devins, G.M. Culturally relevant validity and quality of life measurement. Handbook of disease burdens and quality of life measures 2010, pp. 153–169.

- Copay, A.G.; Glassman, S.D.; Subach, B.R.; Berven, S.; Schuler, T.C.; Carreon, L.Y. Health-related quality of life: analysis of a decade of data from an adult spinal deformity database. Spine 2018, 43, 125–132.

- Finkelstein, J.A.; Schwartz, C.E. Patient-reported outcomes in spine surgery: past, current, and future directions: JNSPG 75th anniversary invited review article. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 2019, 31, 155–164.

- Sheikhalishahi, S.; Miotto, R.; Dudley, J.T.; Lavelli, A.; Rinaldi, F.; Osmani, V. Natural language processing of clinical notes on chronic diseases: systematic review. JMIR medical informatics 2019, 7, e12239.

- Cammel, S.A.; De Vos, M.S.; van Soest, D.; Hettne, K.M.; Boer, F.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Boosman, H. How to automatically turn patient experience free-text responses into actionable insights: a natural language programming (NLP) approach. BMC medical informatics and decision making 2020, 20, 1–10.

- Kichloo, A.; Albosta, M.; Dettloff, K.; Wani, F.; El-Amir, Z.; Singh, J.; Aljadah, M.; Chakinala, R.C.; Kanugula, A.K.; Solanki, S.; others. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Family medicine and community health 2020, 8.

- Fortune Business Insights. Telehealth Market Size, Share, Growth and Industry Analysis [2032]. Fortune Business Insights 2024.

- Falavigna, A.; Dozza, D.C.; Teles, A.R.; Wong, C.C.; Barbagallo, G.; Brodke, D.; Al-Mutair, A.; Ghogawala, Z.; Riew, K.D. Patient-reported outcome measures in spine surgery. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 2017, 27, 1–10.

- Greaves, F.; Ramirez-Cano, D.; Millett, C.; Darzi, A.; Donaldson, L. Use of sentiment analysis for capturing patient experience from free-text comments posted online. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2013, 15, e239.

- Denecke, K.; Deng, Y. Sentiment analysis in medical settings: New opportunities and challenges. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2015, 64, 17–27.

- Wang, Y.; Sohn, S.; Liu, S.; Shen, F.; Wang, L.; Atkinson, E.J.; Amin, S.; Liu, H. Natural language processing for patient-reported outcomes: data from clinical notes of pain assessments. AMIA Summits on Translational Science Proceedings 2018, 2018, 229.

- Korkontzelos, I.; Nikfarjam, A.; Shardlow, M.; Sarker, A.; Ananiadou, S.; Gonzalez, G.H. Analysis of the effect of sentiment analysis on extracting adverse drug reactions from tweets and forum posts. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2016, 62, 148–158.

- Gohil, S.; Vuik, S.; Darzi, A. Social media sentiment analysis for chronic disease management: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2018, 20, e38.

- Gohil, S.; Vuik, S.; Darzi, A. Systematic review of the use of sentiment analysis in healthcare. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2021, 21, 1–18.

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry disability index. Spine 2000, 25, 2940–2953.

- Tonosu, J.; Takeshita, K.; Hara, N.; Matsudaira, K.; Kato, S.; Masuda, K.; Chikuda, H. The normative score and the cut-off value of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). European Spine Journal 2012, 21, 1596–1602.

- Vianin, M. Psychometric properties and clinical usefulness of the Oswestry Disability Index. Journal of chiropractic medicine 2008, 7, 161–163.

- Zanoli, G.; Jönsson, B.; Strömqvist, B. SF-36 scores in degenerative lumbar spine disorders: analysis of prospective data from 451 patients. Acta orthopaedica 2006, 77, 298–306.

- Walsh, T.L.; Homa, K.; Hanscom, B.; Lurie, J.; Sepulveda, M.G.; Abdu, W. Screening for depressive symptoms in patients with chronic spinal pain using the SF-36 Health Survey. The Spine Journal 2006, 6, 316–320.

- Guilfoyle, M.R.; Seeley, H.; Laing, R.J. The Short Form 36 health survey in spine disease—validation against condition-specific measures. British journal of neurosurgery 2009, 23, 401–405.

- Zhang, Y.; Bo, Q.; Lun, S.s.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J. The 36-item short form health survey: reliability and validity in Chinese medical students. International journal of medical sciences 2012, 9, 521.

- Asher, M.; Lai, S.M.; Burton, D.; Manna, B. Discrimination validity of the scoliosis research society-22 patient questionnaire: relationship to idiopathic scoliosis curve pattern and curve size. Spine 2003, 28, 74–77.

- Asher, M.; Lai, S.M.; Burton, D.; Manna, B. The reliability and concurrent validity of the scoliosis research society-22 patient questionnaire for idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 2003, 28, 63–69.

- Monticone, M.; Nava, C.; Leggero, V.; Rocca, B.; Salvaderi, S.; Ferrante, S.; Ambrosini, E. Measurement properties of translated versions of the Scoliosis Research Society-22 Patient Questionnaire, SRS-22: a systematic review. Quality of Life Research 2015, 24, 1981–1998.

- Climent, J.M.; Bago, J.; Ey, A.; Perez-Grueso, F.J.; Izquierdo, E. Validity of the Spanish version of the Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22) patient questionnaire. Spine 2005, 30, 705–709.

- Alanay, A.; Cil, A.; Berk, H.; Acaroglu, R.E.; Yazici, M.; Akcali, O.; Kosay, C.; Genc, Y.; Surat, A. Reliability and validity of adapted Turkish Version of Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22) questionnaire. Spine 2005, 30, 2464–2468.

- Patel, A.A.; Dodwad, S.N.M.; Boody, B.S.; Bhatt, S.; Savage, J.W.; Hsu, W.K.; Rothrock, N.E. Patient-reported outcome measures in adult spinal deformity surgery: a systematic review. Spine 2018, 43, 978–989.

- Jacobson, R.P.; Kang, D.; Houck, J. Can Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System®(PROMIS) measures accurately enhance understanding of acceptable symptoms and functioning in primary care? Journal of patient-reported Outcomes 2020, 4, 1–11.

- Segawa, E.; Schalet, B.; Cella, D. A comparison of computer adaptive tests (CATs) and short forms in terms of accuracy and number of items administrated using PROMIS profile. Quality of Life Research 2020, 29, 213–221.

- Patel, A.A.; Dodwad, S.N.M.; Boody, B.S.; Bhatt, S.; Savage, J.W.; Hsu, W.K.; Rothrock, N.E. Validation of Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) computer adaptive tests (CATs) in the surgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine 2018, 43, 1521–1528.

- Choi, S.; Lim, S.; Schalet, B.; Kaat, A.; Cella, D. PROsetta: An R package for linking patient-reported outcome measures. Applied psychological measurement 2021, 45, 386–388.

- Glassman, S.D.; Copay, A.G.; Berven, S.H.; Polly, D.W.; Subach, B.R.; Carreon, L.Y. Defining substantial clinical benefit following lumbar spine arthrodesis. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 2008, 90, 1839–1847.

- Copay, A.G.; Subach, B.R.; Glassman, S.D.; Polly Jr, D.W.; Schuler, T.C. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. The Spine Journal 2007, 7, 541–546.

- Munroe, B.; Curtis, K.; Considine, J.; Buckley, T. The impact structured patient assessment frameworks have on patient care: an integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2013, 22, 2991–3005.

- van Buchem, M.M.; Neve, O.M.; Kant, I.M.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Boosman, H.; Hensen, E.F. Analyzing patient experiences using natural language processing: development and validation of the artificial intelligence patient reported experience measure (AI-PREM). BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2022, 22, 183.

- Torén, S.; Diarbakerli, E. Health-related quality of life in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: a cross-sectional study including healthy controls. European Spine Journal 2022, 31, 3512–3518.

- Lian, R.; Hsiao, V.; Hwang, J.; Ou, Y.; Robbins, S.E.; Connor, N.P.; Macdonald, C.L.; Sippel, R.S.; Sethares, W.A.; Schneider, D.F. Predicting health-related quality of life change using natural language processing in thyroid cancer. Intelligence-based medicine 2023, 7, 100097.

- He, L.; Omranian, S.; McRoy, S.; Zheng, K. Using Large Language Models for sentiment analysis of health-related social media data: empirical evaluation and practical tips. medRxiv 2024, pp. 2024–03.

- Lovecchio, F.; Riew, K.D. Telemedicine in spine surgery: a systematic review. Global Spine Journal 2020, 10, 61S–69S.

- Iyer, S.; Bovonratwet, P.; Samartzis, D.; Schoenfeld, A.J.; An, H.S.; Awwad, W.; Blumenthal, S.L.; Cheung, J.P.; Derman, P.B.; El-Sharkawi, M.; others. Appropriate telemedicine utilization in spine surgery: results from a Delphi study. Spine 2022, 47, 583–590.

- Melnick, K.; Porche, K.; Sriram, S.; Goutnik, M.; Cuneo, M.; Murad, G.; Chalouhi, N.; Polifka, A.; Hoh, D.J.; Decker, M. Evaluation of patients referred to the spine clinic via telemedicine and the impact on diagnosis and surgical decision-making. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 2023, 1, 1–7.

- Riew, G.J.; Lovecchio, F.; Samartzis, D.; Louie, P.K.; Germscheid, N.; An, H.; Cheung, J.P.Y.; Chutkan, N.; Mallow, G.M.; Neva, M.H.; others. Telemedicine in spine surgery: global perspectives and practices. Global Spine Journal 2023, 13, 1200–1211.

- Weller, S.C.; Vickers, B.; Bernard, H.R.; Blackburn, A.M.; Borgatti, S.; Gravlee, C.C.; Johnson, J.C. Open-ended interview questions and saturation. PloS one 2018, 13, e0198606.

- DeJonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L.M. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Family medicine and community health 2019, 7.

- Fontanella, B.J.B.; Campos, C.J.G.; Turato, E.R. Data collection in clinical-qualitative research: use of non-directed interviews with open-ended questions by health professionals. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 2006, 14, 812–820.

- Gore, R.; Lynch, C. Spinal specific lexicon for sentiment analysis of adult spinal deformity patient interviews correlate with SRS22, SF36, and ODI scores: a pilot study of 25 patients. Mendeley Data 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F.Å. A new ANEW: Evaluation of a word list for sentiment analysis in microblogs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1103.2903 2011.

- Hu, M.; Liu, B. Mining and summarizing customer reviews. Proceedings of the tenth ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining, 2004, pp. 168–177.

- Mohammad, S.M.; Turney, P.D. Crowdsourcing a word–emotion association lexicon. Computational intelligence 2013, 29, 436–465.

- Labille, K.; Gauch, S.; Alfarhood, S. Creating domain-specific sentiment lexicons via text mining. Proc. Workshop Issues Sentiment Discovery Opinion Mining (WISDOM), 2017, pp. 1–8.

- Deng, S.; Sinha, A.P.; Zhao, H. Adapting sentiment lexicons to domain-specific social media texts. Decision Support Systems 2017, 94, 65–76.

- Yekrangi, M.; Abdolvand, N. Financial markets sentiment analysis: Developing a specialized lexicon. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems 2021, 57, 127–146.

- Rinker, T. R Package ‘textstem’. Retrieved March 2018, 17, 2019.

- Symeonidis, S.; Effrosynidis, D.; Arampatzis, A. A comparative evaluation of pre-processing techniques and their interactions for twitter sentiment analysis. Expert Systems with Applications 2018, 110, 298–310.

- Zhang, L.; Nie, X.; Zhang, M.; Gu, M.; Geissen, V.; Ritsema, C.J.; Niu, D.; Zhang, H. Lexicon and attention-based named entity recognition for kiwifruit diseases and pests: A Deep learning approach. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1053449.

- Rinker, T. Package ‘sentimentr’. Retrieved 2017, 8, 31.

- Vasiliev, Y. Natural language processing with Python and spaCy: A practical introduction; No Starch Press, 2020.

- Savova, G.K.; Masanz, J.J.; Ogren, P.V.; Zheng, J.; Sohn, S.; Kipper-Schuler, K.C.; Chute, C.G. Mayo clinical Text Analysis and Knowledge Extraction System (cTAKES): architecture, component evaluation and applications. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2010, 17, 507–513.

- Sedgwick, P. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni correction. Bmj 2012, 344.

- Steiger, J.H. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological bulletin 1980, 87, 245.

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, W.; Xiahou, Z.; Song, Y. Unveiling the hidden link between oral flora and colorectal cancer: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15, 1451160.

- Lee, R.Y.; Kross, E.K.; Torrence, J.; Li, K.S.; Sibley, J.; Cohen, T.; Lober, W.B.; Engelberg, R.A.; Curtis, J.R. Assessment of natural language processing of electronic health records to measure goals-of-care discussions as a clinical trial outcome. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e231204–e231204.

- Adogwa, O.; Karikari, I.O.; Elsamadicy, A.A.; Sergesketter, A.R.; Galan, D.; Bridwell, K.H. Correlation of 2-year SRS-22r and ODI patient-reported outcomes with 5-year patient-reported outcomes after complex spinal fusion: a 5-year single-institution study of 118 patients. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 2018, 29, 422–428.

- Fujimori, T.; Nagamoto, Y.; Takenaka, S.; Kaito, T.; Kanie, Y.; Ukon, Y.; Furuya, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Okuda, S.; Iwasaki, M.; others. Development of patient-reported outcome for adult spinal deformity: validation study. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1286.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).