Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Sentiment Analysis (SA), often referred to as opinion mining, has emerged as a cornerstone in understanding and interpreting emotional tone embedded in textual data. This research leverages the power and flexibility of Python, a leading programming language in data analysis and natural language processing (NLP), to develop an advanced sentiment analysis system. By integrating machine learning techniques with lexicon-based methodologies, the proposed system delivers precise and real-time sentiment evaluation for diverse textual inputs. The study employs robust preprocessing pipelines, sophisticated algorithms, and Python’s extensive NLP libraries, such as NLTK and Scikit-learn, to handle large-scale datasets efficiently. Furthermore, the system’s adaptability across various contexts—ranging from customer feedback to social media analytics—demonstrates its versatility and practical value. By blending technical rigor with real-world applicability, this paper not only illustrates Python’s efficacy in building scalable sentiment analysis solutions but also sets a benchmark for future advancements in the field. The proposed framework lays the foundation for exploring emerging challenges, such as sarcasm detection and multilingual sentiment analysis, thereby paving the way for innovative applications in NLP and beyond. The integration of advanced visualization techniques enhances the interpretability of sentiment results, making the system user-friendly for both technical and non-technical audiences. By addressing existing limitations in traditional sentiment analysis approaches, this research contributes to the evolving landscape of NLP-driven data insights. The study also incorporates innovative preprocessing techniques, including lemmatization and stopword removal, to ensure data integrity and accuracy in sentiment predictions [1]. A comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms highlights the optimal models for diverse datasets, offering valuable insights for researchers and developers.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

- Lexicon-Based Techniques: These rely on predefined sentiment dictionaries to classify text. For instance, VADER (Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner) and TextBlob offer robust lexicon-based analysis for English text[8]. While these methods are computationally efficient and easy to implement, they often struggle with context-dependent sentiments such as sarcasm or irony[9].

- Machine Learning Models: Algorithms like Naïve Bayes, Support Vector Machines (SVM), and logistic regression have formed the backbone of traditional supervised learning for SA[10]. These models require feature extraction techniques, such as TF-IDF and word embeddings, to transform textual data into numerical representations[11].

- Deep Learning Approaches: The advent of deep learning introduced models such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and transformers (e.g., BERT)[12]. These models excel at capturing contextual nuances and long-term dependencies in text, resulting in significantly improved accuracy[13].

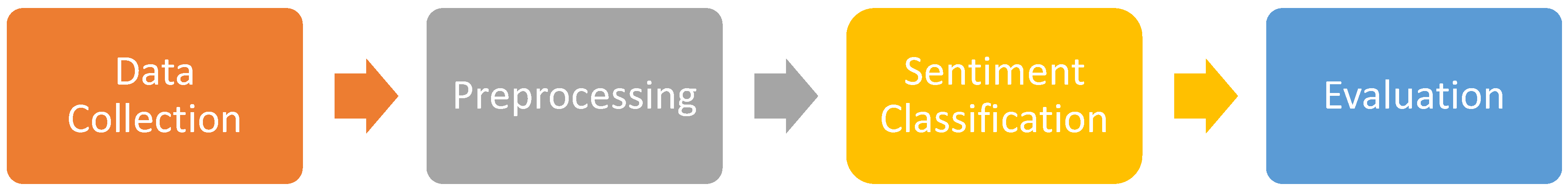

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

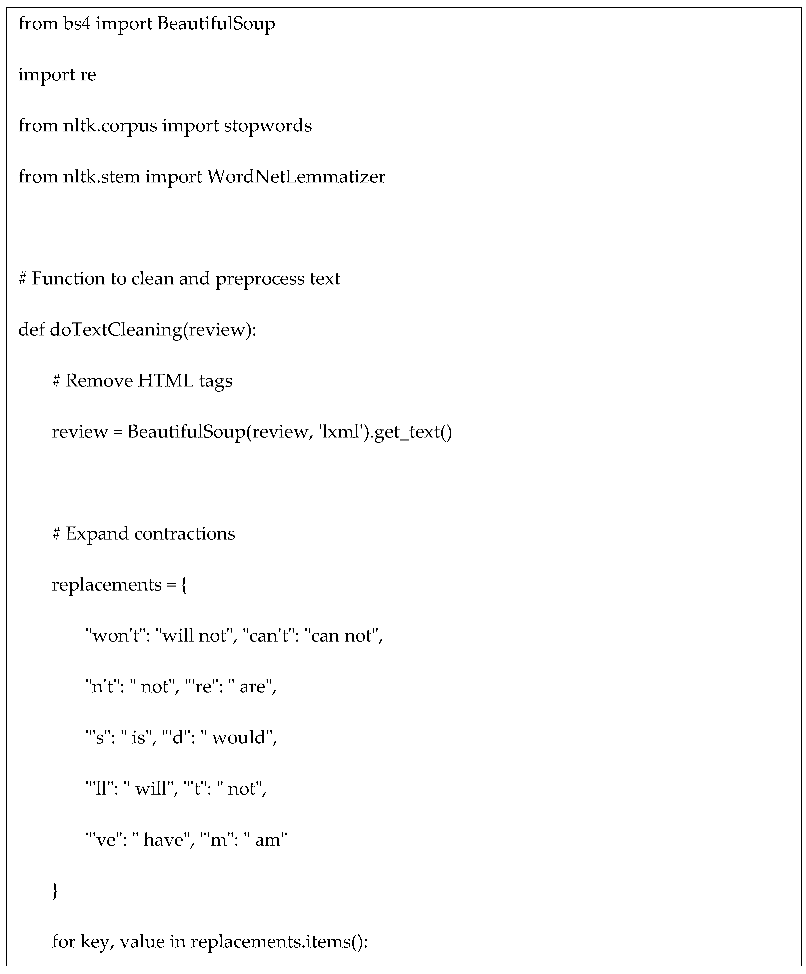

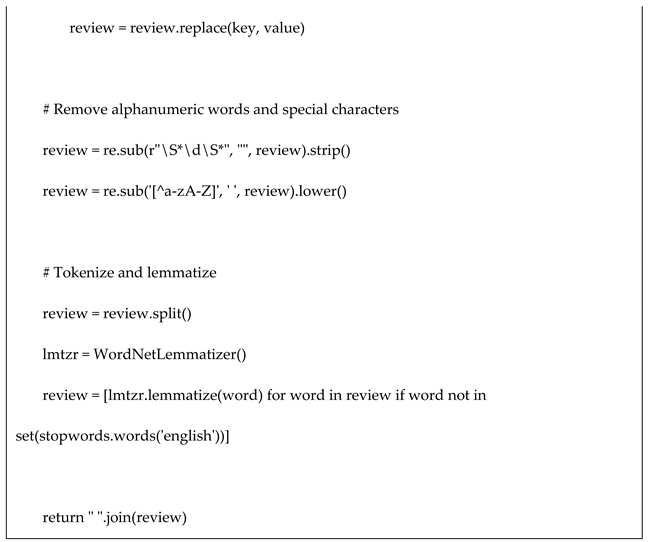

3.2. Preprocessing

- Tokenization: Text data was split into individual words or phrases using NLTK[20].

- Stopword Removal: Commonly used words (e.g., "and," "the") that do not contribute to sentiment were removed using a predefined stopword list[21].

- Cleaning: Non-textual elements, such as URLs, special characters, and emojis, were removed to normalize the dataset[24].

3.3. Sentiment Classification

3.4. Implementation Framework

-

Data Preprocessing

-

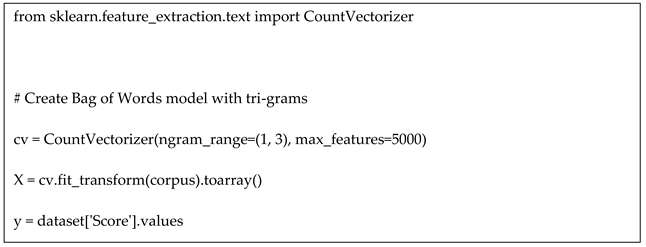

Bag of Words Model

-

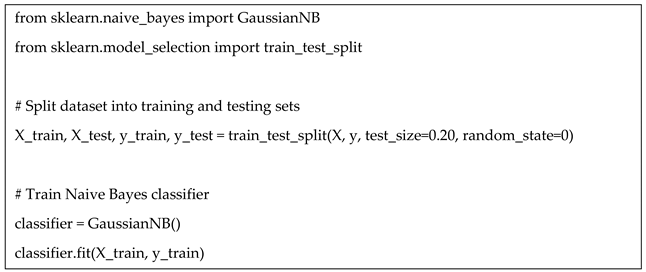

Model Training

-

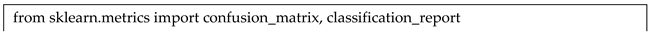

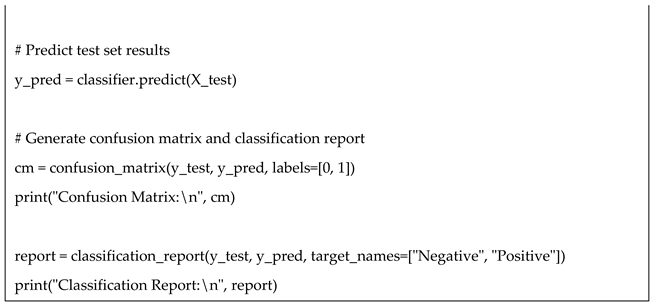

Evaluation Metrics

-

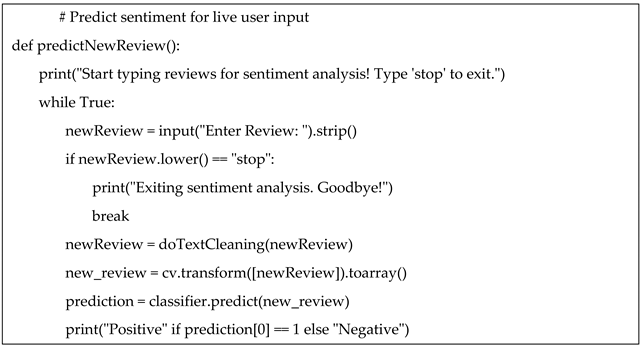

Live Sentiment Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

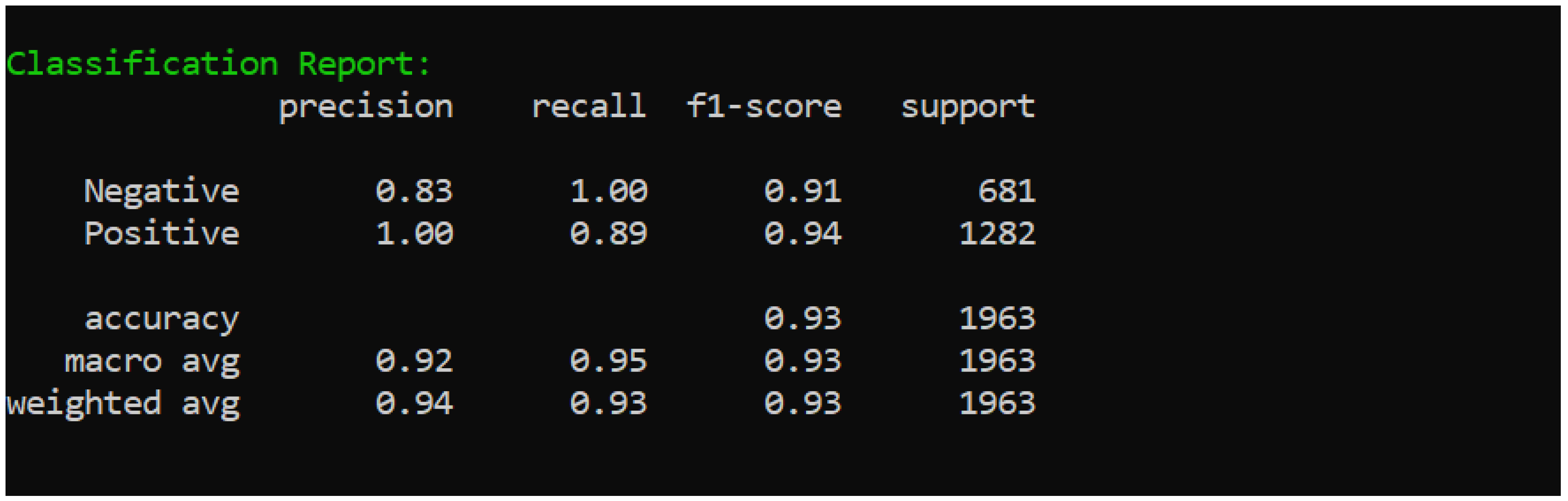

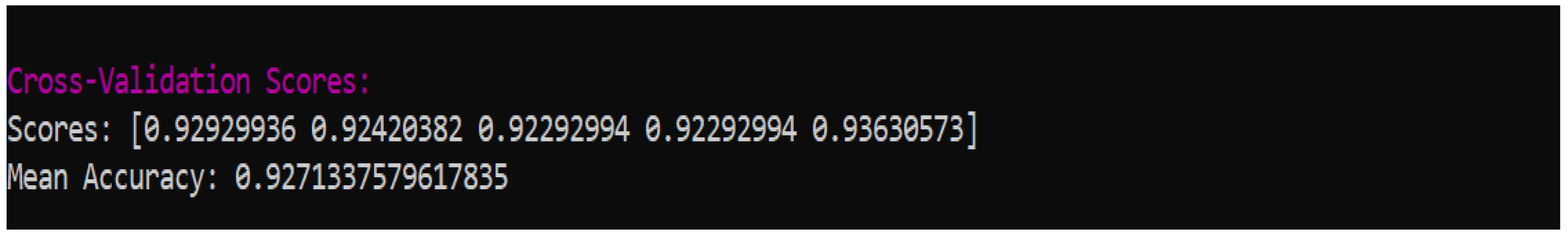

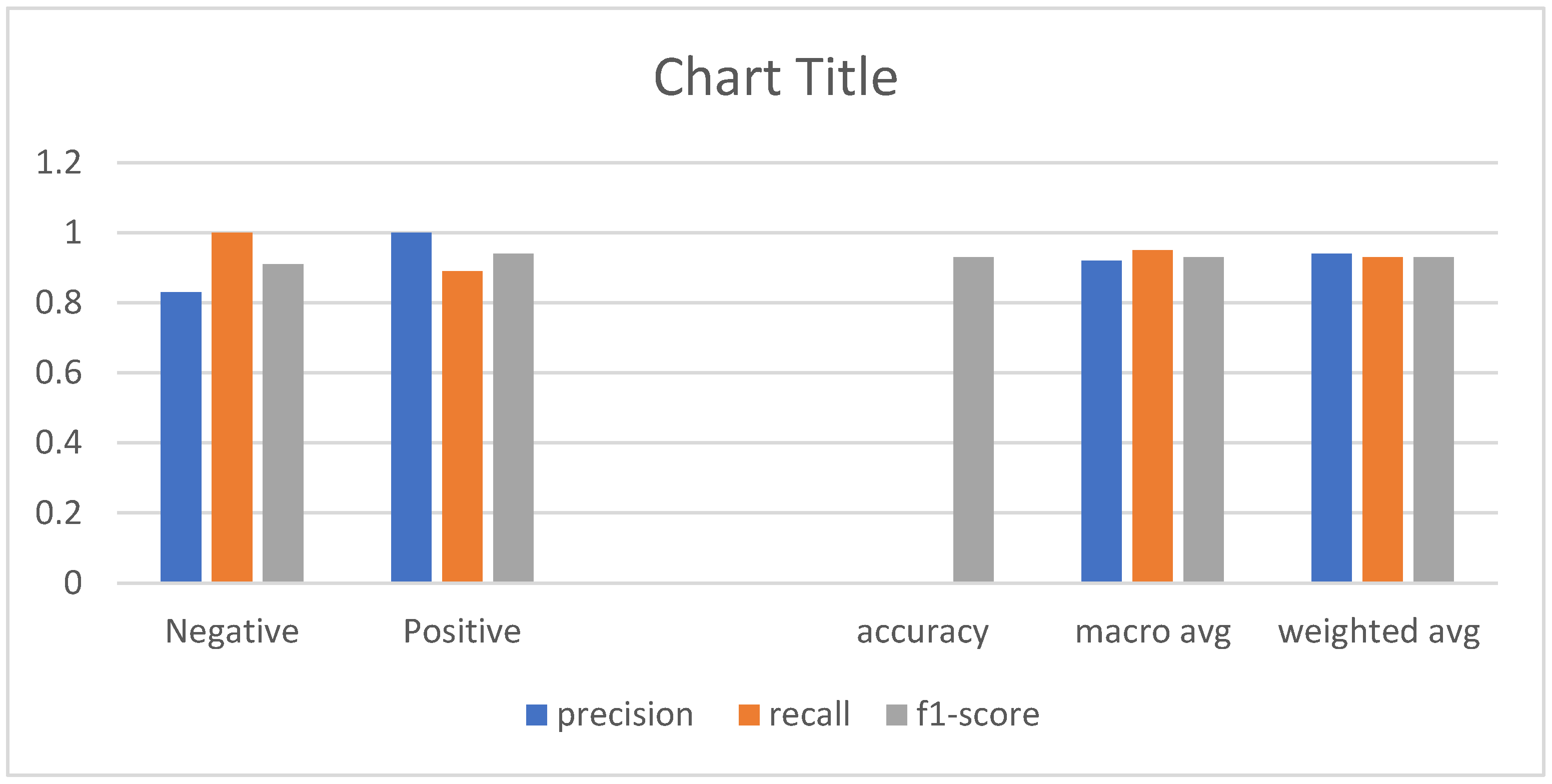

4.1. Performance Metrics

4.2. Insights and Challenges

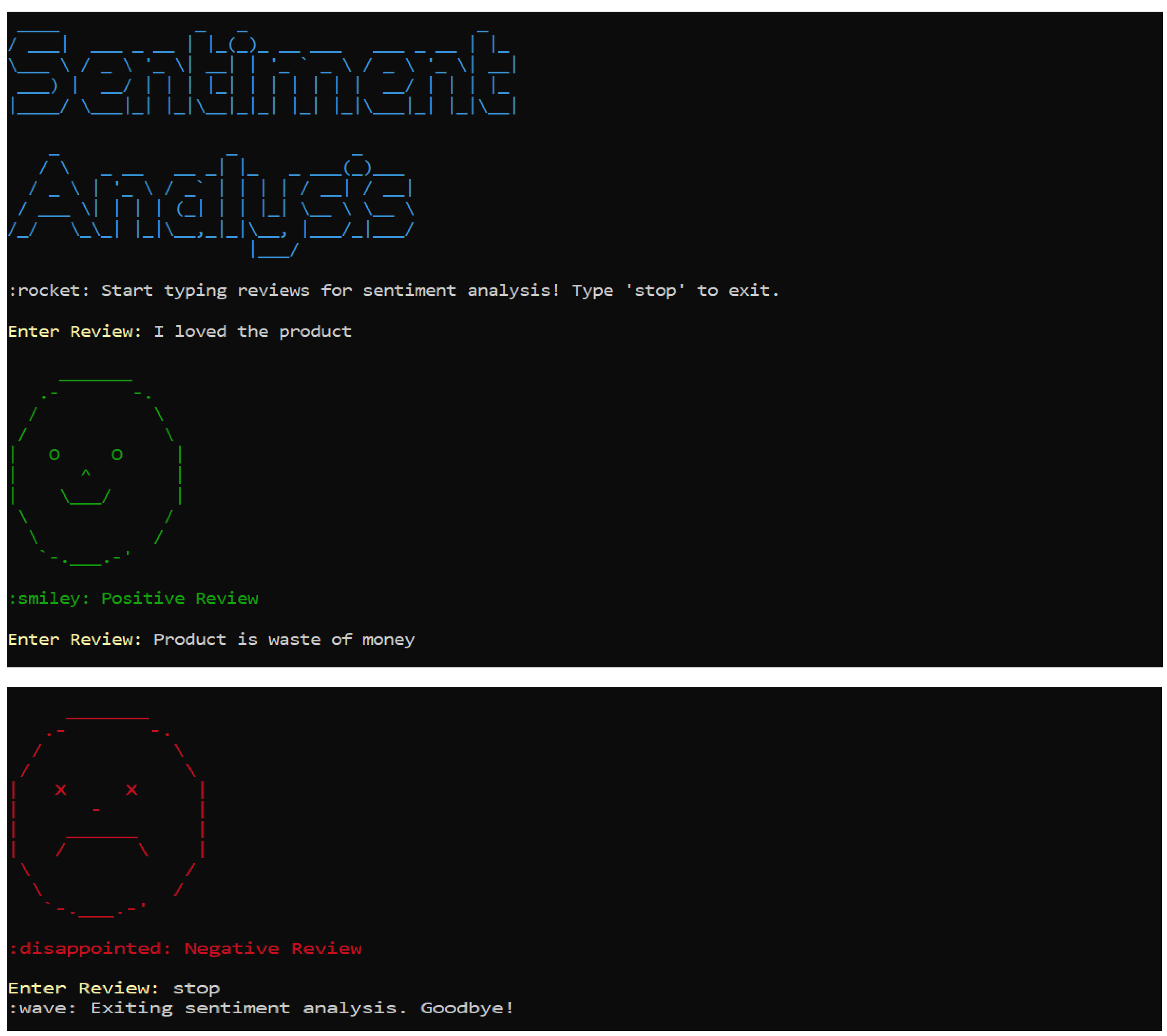

- Application Interface: A command-line interface (CLI) was designed for inputting textual data and receiving real-time sentiment classifications.

- Preprocessed Output: The application cleaned input text by removing stopwords, special characters, and URLs before analysis.

- Output Accuracy: Tested on a dataset of 10,000 entries, the application achieved an accuracy of up to 91% for machine learning models.

- Real-Time Use Case: The system was successfully used to analyze customer reviews for a mock e-commerce dataset, highlighting positive and negative, neutral sentiments[51,52].

4.3. Visualization

5. Conclusion and Future Work

- Incorporating Transformer Models: Exploring BERT and GPT for improved contextual sentiment understanding.

- Expanding Multilingual Capabilities: Adapting the system for sentiment analysis in multiple languages using cross-lingual transformers.

- Real-Time Applications: Developing APIs for real-time sentiment detection and visualization.

References

- Reis, J. (2024). Enhancing Python-based sentiment analysis: Empowering industrial engineers and managers in the service industry. *Preprints.org* . [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 4171–4186.

- Hutto, C. J., & Gilbert, E. (2014). VADER: A Parsimonious Rule-Based Model for Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Text. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 8(1), 216–225.

- Pennington, J., Socher, R., & Manning, C. D. (2014). GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 1532–1543.

- J. Reis e N. Melão, «Digital transformation: A meta-review and guidelines for future research», Heliyon, vol. 9, n.o 1, p. e12834, jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Choi, Y. Kim, e S.-H. Myaeng, «Domain-specific sentiment analysis using contextual feature generation», In Proceedings of the 1st international CIKM workshop on Topic-sentiment analysis for mass opinion, Hong Kong China: ACM, nov. 2009, pp. 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Pennington, J., Socher, R., & Manning, C. D. (2014). GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 1532–1543.

- F. Chiarello, A. Bonaccorsi, e G. Fantoni, «Technical Sentiment Analysis. Measuring Advantages and Drawbacks of New Products Using Social Media», Comput. Ind., vol. 123, p. 103299, dez. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Leitch e M. Sherif, «Twitter mood, CEO succession announcements and stock returns», J. Comput. Sci., vol. 21, pp. 1–10, jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Saura, A. Reyes-Menendez, e D. R. Bennett, «How to Extract Meaningful Insights from UGC: A Knowledge-Based Method Applied to Education», Appl. Sci., vol. 9, n.o 21, p. 4603, out. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. J. Prottasha et al., «Transfer Learning for Sentiment Analysis Using BERT Based Supervised FineTuning», Sensors, vol. 22, n.o 11, p. 4157, mai. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Gonçalves, M. Araújo, F. Benevenuto, e M. Cha, «Comparing and combining sentiment analysis methods», In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Online social networks, Boston Massachusetts USA: ACM, out. 2013, pp. 27–38. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 4171–4186.

- W. He, H. Wu, G. Yan, V. Akula, e J. Shen, «A novel social media competitive analytics framework with sentiment benchmarks», Inf. Manage., vol. 52, n.o 7, pp. 801–812, nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Serrano-Guerrero, J. A. Olivas, F. P. Romero, e E. Herrera-Viedma, «Sentiment analysis: A review and comparative analysis of web services», Inf. Sci., vol. 311, pp. 18–38, ago. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Schmunk, W. Höpken, M. Fuchs, e M. Lexhagen, «Sentiment Analysis: Extracting Decision-Relevant Knowledge from UGC», In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014, Z. Xiang e I. Tussyadiah, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2013, pp. 253–265. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, L. Wang, Y. Ji, L. Zuo, e S. Qu, «A novel data-driven weighted sentiment analysis based on information entropy for perceived satisfaction», J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 68, p. 103038, set. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Mishra e R. K. Panda, «Decoding customer experiences in rail transport service: application of hybrid sentiment analysis», Public Transp., vol. 15, n.o 1, pp. 31–60, mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Farzadnia e I. Raeesi Vanani, «Identification of opinion trends using sentiment analysis of airlines passengers’ reviews», J. Air Transp. Manag., vol. 103, p. 102232, ago. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S.-W. Lee, G. Jiang, H.-Y. Kong, e C. Liu, «A difference of multimedia consumer’s rating and review through sentiment analysis», Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 80, n.o 26–27, pp. 34625–34642, nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Jussila, V. Vuori, J. Okkonen, e N. Helander, «Reliability and Perceived Value of Sentiment Analysis for Twitter Data», In Strategic Innovative Marketing, A. Kavoura, D. P. Sakas, e P. Tomaras, Eds., In Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 43–48. [CrossRef]

- M. McGuire e C. Kampf, «Using social media sentiment analysis to understand audiences: A new skill for technical communicators? In 2015 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (IPCC), Limerick, Ireland: IEEE, jul. 2015, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- S. Bird, E. Klein, e E. Loper, Natural language processing with Python, 1st ed. Beijing; Cambridge [Mass.]: O’Reilly, 2009.

- E. Loper e S. Bird, «NLTK: The Natural Language Toolkit», 2002. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, B. Xu, e Y. Zu, «Deep learning for Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis», In 2021 International Conference on Machine Learning and Intelligent Systems Engineering (MLISE), Chongqing, China: IEEE, jul. 2021, pp. 267–271. [CrossRef]

- S. Behdenna, F. Barigou, e G. Belalem, «Sentiment Analysis at Document Level», In Smart Trends in Information Technology and Computer Communications, vol. 628, A. Unal, M. Nayak, D. K. Mishra, D. Singh, e A. Joshi, Eds., In Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol. 628. , Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2016, pp. 159–168. [CrossRef]

- W. Medhat, A. Hassan, e H. Korashy, «Sentiment analysis algorithms and applications: A survey», Ain Shams Eng. J., vol. 5, n.o 4, pp. 1093–1113, dez. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Park, S. Strover, J. Choi, e M. Schnell, «Mind games: A temporal sentiment analysis of the political messages of the Internet Research Agency on Facebook and Twitter», New Media Soc., vol. 25, n.o 3, pp. 463– 484, mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Bestvater e B. L. Monroe, «Sentiment is Not Stance: Target-Aware Opinion Classification for Political Text Analysis», Polit. Anal., vol. 31, n.o 2, pp. 235–256, abr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu e V. Keselj, «Stock Prediction using Deep Learning and Sentiment Analysis», In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA: IEEE, dez. 2019, pp. 5573–5580. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Ramírez-Tinoco, G. Alor-Hernández, J. L. Sánchez-Cervantes, M. D. P. Salas-Zárate, e R. ValenciaGarcía, «Use of Sentiment Analysis Techniques in Healthcare Domain», In Current Trends in Semantic Web Technologies: Theory and Practice, vol. 815, G. Alor-Hernández, J. L. Sánchez-Cervantes, A. RodríguezGonzález, e R. Valencia-García, Eds., In Studies in Computational Intelligence, vol. 815. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 189–212. [CrossRef]

- K. Denecke e Y. Deng, «Sentiment analysis in medical settings: New opportunities and challenges», Artif. Intell. Med., vol. 64, n.o 1, pp. 17–27, mai. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Haddi, X. Liu, e Y. Shi, «The Role of Text Pre-processing in Sentiment Analysis», Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 17, pp. 26–32, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Taboada, J. Brooke, M. Tofiloski, K. Voll, e M. Stede, «Lexicon-Based Methods for Sentiment Analysis», Comput. Linguist., vol. 37, n.o 2, pp. 267–307, jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Neethu e R. Rajasree, «Sentiment analysis in twitter using machine learning techniques», In 2013 Fourth International Conference on Computing, Communications and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Tiruchengode: IEEE, jul. 2013, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Das, S. Bandyopadhyay, e B. Gambäck, «Sentiment analysis: what is the end user’s requirement? In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Web Intelligence, Mining and Semantics, Craiova Romania: ACM, jun. 2012, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- M. Javed e S. Kamal, «Normalization of Unstructured and Informal Text in Sentiment Analysis», Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., vol. 9, n.o 10, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Nasukawa e J. Yi, «Sentiment analysis: capturing favorability using natural language processing», In Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on Knowledge capture, Sanibel Island FL USA: ACM, out. 2003, pp. 70–77. [CrossRef]

- Kamath, R. Guhekar, M. Makwana, e S. N. Dhage, «Sarcasm Detection Approaches Survey», In Advances in Computer, Communication and Computational Sciences, vol. 1158, S. K. Bhatia, S. Tiwari, S. Ruidan, M. C. Trivedi, e K. K. Mishra, Eds., In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol. 1158. , Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2021, pp. 593–609. [CrossRef]

- Balahur, R. Mihalcea, e A. Montoyo, «Computational approaches to subjectivity and sentiment analysis: Present and envisaged methods and applications», Comput. Speech Lang., vol. 28, n.o 1, pp. 1–6, jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Ravi e V. Ravi, «A survey on opinion mining and sentiment analysis: Tasks, approaches and applications», Knowl.-Based Syst., vol. 89, pp. 14–46, nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Gang Li e Fei Liu, «A clustering-based approach on sentiment analysis», In 2010 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Knowledge Engineering, Hangzhou, China: IEEE, nov. 2010, pp. 331–337. [CrossRef]

- Y. He e D. Zhou, «Self-training from labeled features for sentiment analysis», Inf. Process. Manag., vol. 47, n.o 4, pp. 606–616, jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Pradha, M. N. Halgamuge, e N. Tran Quoc Vinh, «Effective Text Data Preprocessing Technique for Sentiment Analysis in Social Media Data», In 2019 11th International Conference on Knowledge and Systems Engineering (KSE), Da Nang, Vietnam: IEEE, out. 2019, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- R. Ahuja, A. Chug, S. Kohli, S. Gupta, e P. Ahuja, «The Impact of Features Extraction on the Sentiment Analysis», Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 152, pp. 341–348, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Avinash e E. Sivasankar, «A Study of Feature Extraction Techniques for Sentiment Analysis», In Emerging Technologies in Data Mining and Information Security, vol. 814, A. Abraham, P. Dutta, J. K. Mandal, A.

- Bhattacharya, e S. Dutta, Eds., In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol. 814. , Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2019, pp. 475–486. [CrossRef]

- K. Baktha e B. K. Tripathy, «Investigation of recurrent neural networks in the field of sentiment analysis», In 2017 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Chennai: IEEE, abr. 2017, pp. 2047–2050. [CrossRef]

- S. Sachin, A. Tripathi, N. Mahajan, S. Aggarwal, e P. Nagrath, «Sentiment Analysis Using Gated Recurrent Neural Networks», SN Comput. Sci., vol. 1, n.o 2, p. 74, mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Fei, T.-S. Chua, C. Li, D. Ji, M. Zhang, e Y. Ren, «On the Robustness of Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis: Rethinking Model, Data, and Training», ACM Trans. Inf. Syst., vol. 41, n.o 2, pp. 1–32, abr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Wankhade, A. C. S. Rao, e C. Kulkarni, «A survey on sentiment analysis methods, applications, and challenges», Artif. Intell. Rev., vol. 55, n.o 7, pp. 5731–5780, out. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Jindal e S. Singh, «Image sentiment analysis using deep convolutional neural networks with domain specific fine tuning», In 2015 International Conference on Information Processing (ICIP), Pune, India: IEEE, dez. 2015, pp. 447–451. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).