1. Introduction

Term weighting is central to vector-space representations for sentiment analysis (SA) and text classification. Unsupervised schemes such as TF–IDF remain strong and transparent baselines but they are label-agnostic and therefore cannot reward sentiment-specific terms [

1,

2]. Supervised term weighting (STW) addresses this limitation by exploiting class-label statistics, either by learning the weighting function from class evidence [

3] or by redesigning global factors to enhance class discrimination [

4,

5,

6]. In parallel, entropy-based global factors conceptualize term importance through distributional concentration across classes and they show consistent advantages over traditional formulas on standard benchmarks [

7]. Information-theoretic extensions such as cumulative residual entropy and related generalizations provide additional structure for principled design [

5,

8,

9].

Local term-frequency modeling also affects robustness. Collection-aware TF adjustments and non-linear binning demonstrate that rethinking TF can yield tangible gains when paired with suitable global terms [

10,

11]. Practical studies additionally highlight confounders including class imbalance and data drift, for example imbalance-aware IGM variants, and preprocessing choices. These factors can substantially shift outcomes. Reproducible studies should therefore specify them explicitly [

12,

13,

14].

Research gap. Despite these advances, two limitations persist for SA-oriented term weighting. Many STW formulations emphasize class-conditional evidence (e.g., relevance or category frequency and learned discriminants) while rarely quantifying a term’s uncertainty of association with sentiment labels. In other words, few methods measure how selectively a term aligns with polarity classes versus how diffusely it spans them [

3,

4,

6,

15]. In addition, entropy-based factors do quantify distributional concentration across classes [

7], yet they are seldom sentiment-tailored or plug-and-play within a lightweight and interpretable TF–IDF pipeline that is readily deployable and auditable with classic bag-of-words classifiers across multiple public datasets [

1]. For broader method-selection context, see [

16]. Consequently, there remains a practical need for an information-theoretic, sentiment-aware global factor that directly measures label-wise concentration for polarity, composes cleanly with TF–IDF, and is validated transparently under standard learners.

This work and contributions. We introduce Term Sentiment Entropy (TSE), an information-theoretic, sentiment-aware global factor combined multiplicatively with TF-IDF. Our evaluation follows a reproducible pipeline with fixed TF and IDF specifications, documented preprocessing, and three classic learners (Naïve Bayes, linear SVC, Random Forest) across four public datasets. Our contributions are threefold.

(1) A sentiment-aware, information-theoretic global factor that up-weights sentiment-specific terms and down-weights sentiment-ambiguous ones while preserving sparse-vector interpretability.

(2) Pipeline clarity and comparability through fixed specifications, leakage control, and fold-averaged reporting.

(3) A multi-dataset evaluation with transparent, qualitative synthesis across datasets that highlights when the sentiment-entropy factor helps relative to strong TF-IDF baselines.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews supervised and entropy-based term weighting, TF variants, and practical confounders.

Section 3 details the representation and computation of TSE and the experimental protocol.

Section 4 reports results across datasets and classifiers.

Section 5 discusses implications, limitations, and practical guidance.

Section 6 concludes and outlines directions for sentiment-aware entropy variants.

2. Related Work

This section reviews term weighting for sentiment analysis and text classification, structured to connect each line of work to the role of Term Sentiment Entropy, hereafter TSE. The review begins with surveys and foundations, then covers unsupervised and supervised weighting, entropy-based global factors, local term frequency design, hybrid lexical–semantic representations, and practical considerations that influence reproducibility and performance.

Surveys and conceptual foundations.

Comprehensive surveys clarify the landscape of term weighting and text classification. Rathi and Mustafi present a taxonomy that distinguishes local and global factors and summarizes mathematical underpinnings of supervised and unsupervised schemes, which motivates a precise placement for sentiment-aware global factors such as TSE within the vector space model [

1]. Dogra and colleagues synthesize the end-to-end pipeline from data collection to model evaluation, emphasizing that representation choices and evaluation protocols should align with application goals [

17]. Taha proposes a hierarchical survey that helps position weighting methods within broader categories of text classification practice and provides guidance on method selection grounded in empirical evidence [

16]. These surveys support the need for light-weight and interpretable enhancements to sparse representations, a role that TSE is designed to fulfill.

Unsupervised baselines and IDF-style corrections.

TF–IDF remains a strong baseline for sentiment tasks because it balances within-document salience and across-corpus rarity. Sheridan and Ahmed provide a statistical justification that links TF–IDF to significance testing through Fisher’s exact test, which strengthens the theoretical basis for retaining TF–IDF as a component in modern weighting pipelines [

2]. Several works propose global factor corrections that remain unsupervised yet more distribution-aware. Jiang introduces IDF variants based on deviation from average document frequency, which improve robustness on imbalanced collections [

18]. Marwah incorporates a term-recency factor that accounts for temporal dynamics, improving performance when vocabularies evolve over time [

19]. These results support the idea that TF–IDF is a reliable backbone and that principled modifications to the global factor can yield measurable gains, a context in which TSE aims to add sentiment-aware information rather than replacing the baseline entirely.

Supervised term weighting families.

Learning to Weight, or LTW, learns the global term-weighting function directly from class statistics such as true positive and false positive rates, showing consistent improvements over fixed formulas and motivating supervision in the global factor [

3]. The Inverse Gravity Moment family demonstrates that careful co-design of the global factor with the local term frequency can outperform TF–IDF across multiple learners and datasets, with improved variants such as TF-IGM_imp and its square-root TF option yielding robust gains, especially under imbalance [

4]. Okkalioglu further introduces a relative imbalance ratio to explicitly correct majority-class bias within the TF-IGM family, which improves minority recognition [

12]. Category-aware supervision also appears in TF–ICF-style approaches and in supervised feature engineering that seeks lean yet competitive models; Attieh shows that a supervised category factor is competitive with deeper models, with efficiency benefits [

20]. Li and colleagues replace the logarithmic relevance frequency with an exponential form in TF-ERF, which stabilizes the balance between local and global contributions across datasets [

15]. Rough-set–based schemes extend supervision through set-theoretic relations between terms and classes and report performance gains with square-root variants that temper extreme weights [

21]. For sentiment-specific supervision, Alshehri and Algarni introduce TF-TDA, a supervised weighting tailored to sentiment analysis, and report statistically significant improvements across datasets [

6]. These supervised lines all aim to inject class information into the global factor. TSE follows the same principle but measures sentiment association through the normalized uncertainty of

, which complements evidence-ratio and category-frequency designs by focusing on the dispersion of a term over sentiment labels.

Entropy-based global factors and information-theoretic extensions.

Entropy quantifies distributional concentration across categories. Wang and colleagues provide a systematic treatment of entropy-based global factors and show consistent advantages over traditional formulas on multiple benchmarks and classifiers, which gives direct theoretical and empirical support for using information-theoretic dispersion in the global factor [

7]. Tang and coauthors develop a supervised scheme based on cumulative residual entropy, which demonstrates that alternative entropy measures can provide strong signals for class discrimination in a supervised setting [

5]. Broader information-theoretic generalizations unify multiple entropy families and clarify mathematical properties that are valuable when designing new global factors, including weighted and generalized cumulative residual forms [

8]. TSE builds on this information-theoretic thread. It differs from prior entropy-based global terms by explicitly tying the entropy to sentiment labels and by composing the result multiplicatively with TF–IDF to preserve interpretability and deployment simplicity.

Local term frequency design.

Global factors are only one side of the weighting function. Chen and colleagues propose collection-aware modifications to term frequency that improve the quality of TF-based local weights when combined with diverse global factors, which shows that local TF design has a first-order effect on downstream performance [

10]. Shehzad and coauthors introduce Binned Term Count, a non-linear binning of raw counts that mitigates normalization artifacts in long documents and improves classification over standard TF [

11]. These works suggest that a sentiment-aware global factor such as TSE should be tested with clearly specified TF choices since interactions between local and global components can change rankings among weighting schemes.

Hybrid lexical–semantic representations and modified TF–IDF.

Sparse lexical weighting can be combined with semantic signals to improve robustness. Zhao proposes reweighting word embeddings with topic-aware TF–IDF before a convolutional network, leading to better news classification compared with embedding-only baselines [

22]. Xiao and colleagues integrate part-of-speech information and category discriminability into a modified TF–IDF and fuse the result with Word2Vec to classify fine-grained attraction subcategories, reporting consistent gains over standard TF–IDF [

23]. Comparative studies of term weighting across domains indicate that the choice of weighting and classifier can shift the best configuration, a result that supports domain-aware selection and motivates simple and interpretable add-ons like TSE that can be plugged into different sparse–dense hybrids [

18,

24]. Lexicon and rule-augmented sentiment models in social media further show that adding targeted task signals can lift performance when domain structure is exploited carefully, which aligns with the sentiment-aware intent of TSE [

25].

Practical confounders and reproducibility.

Preprocessing can alter results to a large degree. Siino and coauthors show that choices such as lowercasing, stopword removal, and stemming change accuracy even for transformer models, sometimes by wide margins, and that simple models can outperform complex ones under favorable preprocessing, which underlines the importance of documenting pipelines completely [

13]. Class imbalance is a recurring issue in sentiment data. IGM variants with imbalance-aware scaling improve minority recall without sacrificing overall accuracy, and keyword-augmented training in clinical classification improves rare class recognition, indicating that auxiliary signals can mitigate skew in a model-agnostic manner [

12,

26]. Temporal drift motivates time-aware global factors, as shown by term-recency adjustments that benefit evolving corpora [

19]. Large comparative analyses recommend aligning representation and model choice with the downstream objective and constraints, which reinforces the value of light-weight and interpretable enhancements like TSE that preserve pipeline clarity while adding targeted information [

14,

16,

17].

Positioning of TSE.

The literature indicates three requirements for a practical improvement to sparse sentiment representations. The global factor should incorporate class information, it should use a principled signal of class separability such as distributional concentration, and it should compose cleanly with established baselines while keeping the pipeline transparent. TSE addresses these requirements by measuring the uncertainty of a term’s association with sentiment labels and by integrating the resulting factor multiplicatively with TF–IDF. This positioning aligns TSE with supervised and entropy-based traditions while keeping the representation interpretable, which sets the stage for the materials and methods that specify the exact computation and the experimental protocol.

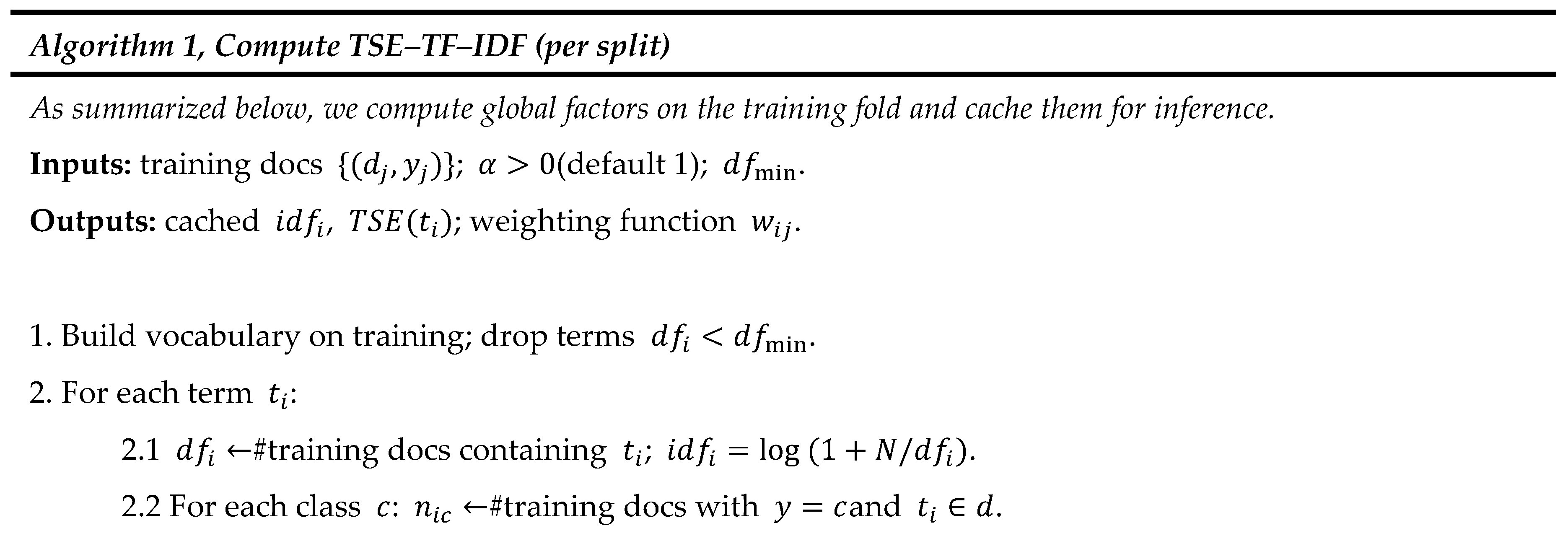

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Problem Setting and Notation

We study supervised

multiclass sentiment classification with classes

. The corpus

contains

documents; each

is labeled

. Let

be the vocabulary. For term

,

denotes the raw count of

in

;

is the number of

training documents containing

. Unless otherwise stated, logarithms are

natural, and

all corpus statistics are computed on the training fold only to avoid leakage [

1,

17]. As we formalize local and global factors used throughout, please

see Eqs. (1)–(3) for TF–IDF.

3.2. Baseline Representation

We fix a single TF–IDF specification across all experiments for clarity and reproducibility.

As shown in

Eq. (1), we adopt log-scaled TF.

The smoothed IDF we use is given in

Eq. (2).

Finally, the baseline TF–IDF weight is defined in

Eq. (3).

TF–IDF remains a strong, interpretable baseline within the VSM and has recent statistical justification [

1,

2].

3.3. Term Sentiment Entropy (TSE)

TSE provides a

global sentiment-selectivity factor that measures how concentrated a term is across classes, consistent with information-theoretic global weighting [

5,

7,

8,

9].

Before we introduce the entropy, we define class-conditional counts and a smoothed distribution. Specifically,

Eq. (4) gives the Laplace-smoothed class probability.

with a

single scalar (default

) shared across classes.

We then compute normalized sentiment entropy in

Eq. (5).

Finally,

Eq. (6) defines the TSE score and the sentiment-aware weight.

This parallels entropy-style global factors while making dispersion explicitly

sentiment-conditioned [

5,

7].

3.3.1. Worked Example on a Toy Corpus

We include a small example to make the computations concrete.

Table 1 reports raw counts and log-TF (see Eq. (1)) for a five-term, four-document toy corpus.

Table 2 lists the corresponding global statistics computed on the same toy data: class-wise document counts

, the document frequency

, the smoothed IDF (see Eq. (2)), and the sentiment measure used in this paper (TSE, normalized). For side-by-side context only, we also display a placeholder column for CMI; note that CMI is not used by our final weighting. The TSE score is computed from the Laplace-smoothed class distribution and normalized entropy (see Eqs. (4)–(6)) and is reported in its normalized form that lies in

.

Toy-corpus labels used for this example. We assume three classes and assign documents as follows: . Laplace smoothing uses .

If you decide to show unnormalized TSE for illustration, add a footnote stating: “TSE values in this table are shown before normalization for illustration. All experiments use the normalized form in Eqs. (5)–(6).”

Table 2 lists the corresponding global statistics computed on the same toy data: class-wise document counts

, the document frequency

, the smoothed IDF (Eq. (2)), and the TSE score (Eqs. (4)–(6)). We focus on TSE here; other global factors are discussed later in Related Work.

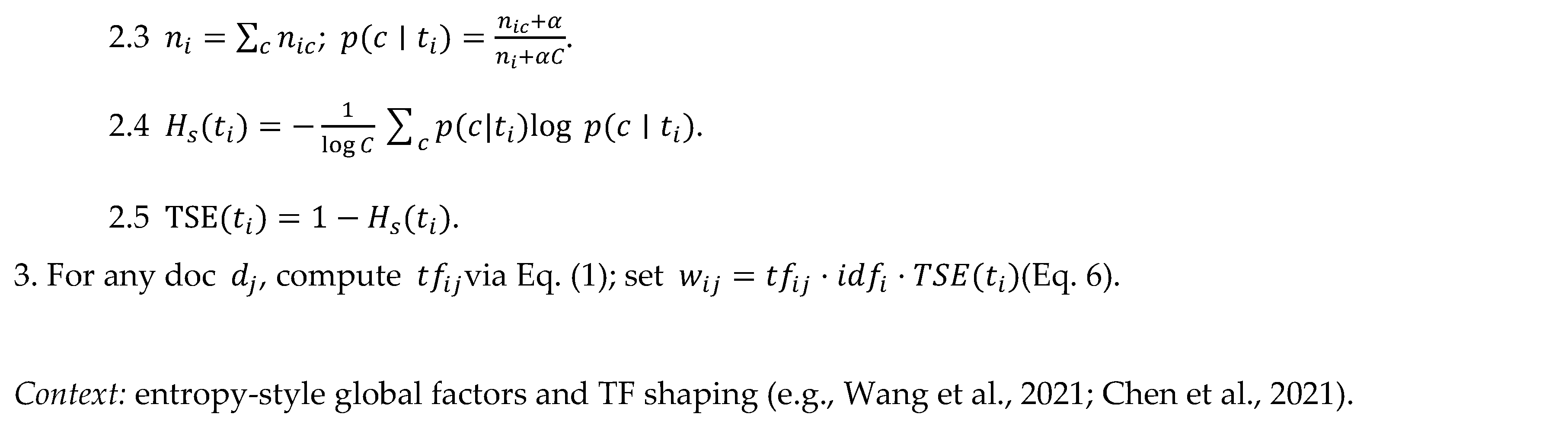

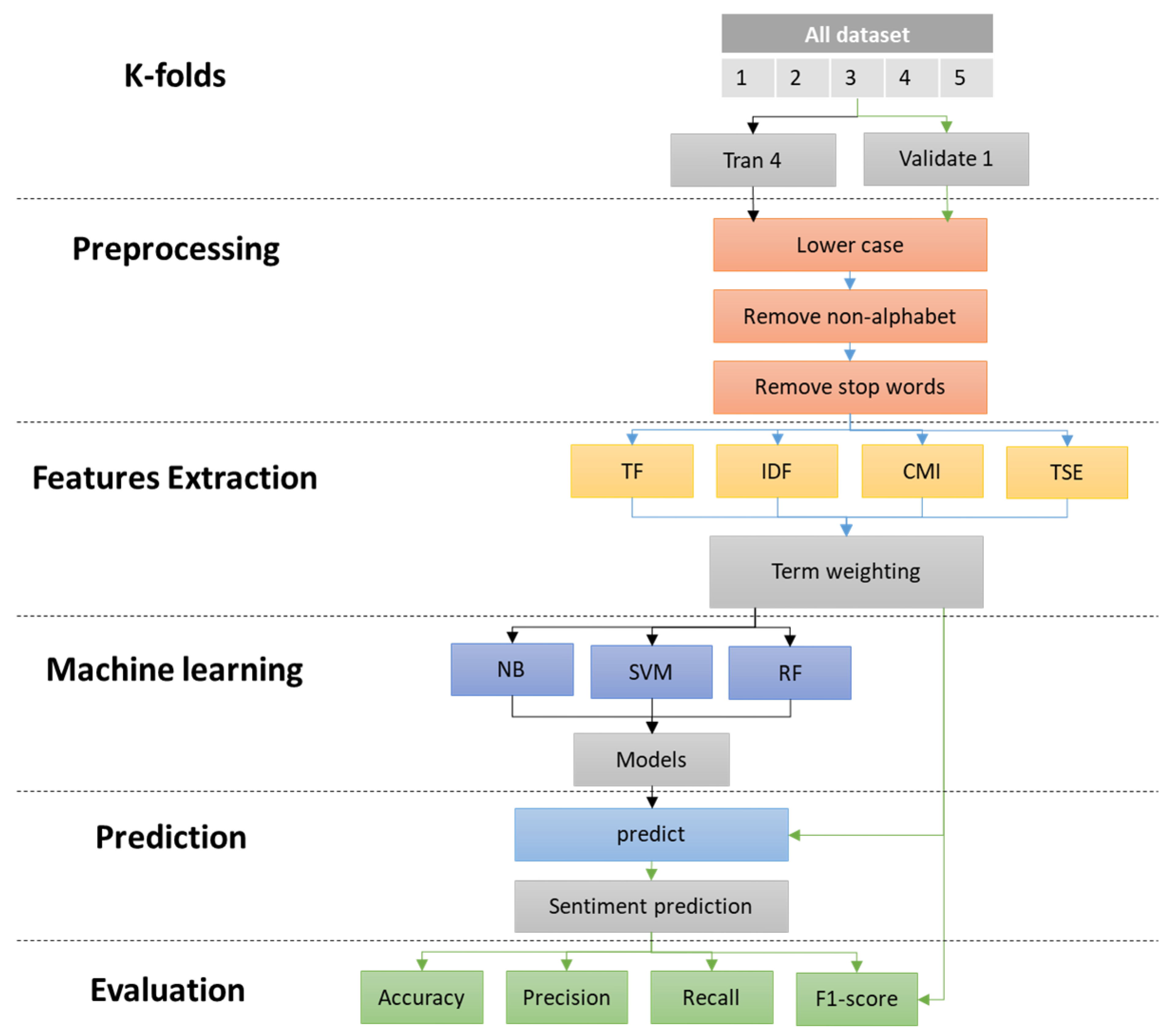

3.3.2. Experimental Pipeline

The end-to-end pipeline for training, prediction and evaluation is illustrated in

Figure 1. Five-fold cross-validation is used. Preprocessing includes lowercasing, removal of non-alphabetic characters and stopword removal. Feature extraction relies on a single TF–IDF specification and compares alternative global factors including IDF, CMI and TSE. Weighted vectors feed Naïve Bayes, linear SVM and Random Forest. Predictions are evaluated with accuracy, macro-precision, macro-recall and macro-F1. TSE is computed from training data only within each fold to avoid leakage.

Five-fold cross-validation is used (train on four folds, validate on one). Preprocessing includes lowercasing, removal of non-alphabetic characters, and stopword removal. Feature extraction adopts a single TF–IDF specification and compares global factors (IDF, CMI, TSE). The weighted vectors are fed to Naïve Bayes, linear SVM, and Random Forest. Predictions are evaluated with accuracy, macro-precision, macro-recall, and macro-F1. TSE is computed from training data only within each fold to avoid leakage.

3.4. Datasets

We evaluate four publicly available sentiment datasets spanning product reviews, long-form movie reviews, and social media. Dataset cards and accession details are listed in the references and cited in-text via author–year.

Table 3 summarizes the number of documents per class, average document length, and vocabulary size after the preprocessing in

Section 3.5, together with access dates and license notes.

Amazon Cell Phones Reviews. A domain-specific e-commerce corpus of review texts with star ratings in the cell-phone category [

27]. Ratings provide an external polarity signal aligned with supervised sentiment analysis. We rely on the public release we accessed (see

Table 3 notes). If an official split is not provided, we follow the protocol in

Section 3.7 (stratified 5-fold).

Coronavirus Tweets NLP. A Twitter collection from the COVID-19 period with human-assigned sentiment labels [

28]. Two granularities appear in the literature: 3-class (positive, neutral, negative) and 5-class (adds “extremely positive/negative”). We use the 3-class setting and keep this choice fixed across all models; see

Table 3.

Twitter US Airline Sentiment. Tweets referencing six US airlines with three sentiment classes and additional negative-reason annotations; a standard short-text benchmark [

29]. When an official or provider split is available we adopt it; otherwise we use the evaluation protocol in

Section 3.7.

IMDb 50K Movie Reviews. A balanced binary corpus of 50,000 long-form reviews labeled positive/negative [

30]. For this study, we accessed a Kaggle mirror (see

Table 3 notes) while citing the original dataset paper for provenance; we follow the canonical 25k/25k train/test split.

Rationale and coverage. Together, these datasets cover distinct domains (e-commerce, film, service tweets) and text lengths (short microtexts versus long reviews). Amazon and IMDb provide review settings with explicit rating signals, whereas the two Twitter sets stress short, noisy, and event-driven language, supporting cross-domain generalization.

Reporting and splits. Unless an official split is mandated, we use stratified 5-fold cross-validation with fixed seeds and strict leakage control (

Section 3.7). Any deviation from the default public files, for example language filtering or deduplication, is stated explicitly in

Table 3 notes.

3.5. Preprocessing

We employ a minimal, reproducible pipeline fit on training data only to avoid leakage [

13,

17]. See

Table 3 for corpus statistics.

Unicode NFC normalization; lowercasing.

Language-appropriate tokenization (fixed per dataset).

Stopwords: dataset-official lists when available; otherwise none.

Vocabulary pruning: (default 2).

Natural-log TF and smoothed IDF, with all corpus statistics computed on the training fold.

Smoothing constant

(default 1); notation as in

Section 3.1.

Ablation note. We varied and ; results follow the same trend and do not change the conclusions. Full scripts and CSVs are provided in the artifact repository.

3.6. Classifiers

We evaluate Multinomial Naïve Bayes, Random Forest, and a linear Support Vector Classifier, strong sparse baselines that isolate representation effects [

14,

17]. Principal hyperparameters and software versions are listed in the artifact repository to enable exact reproducibility.

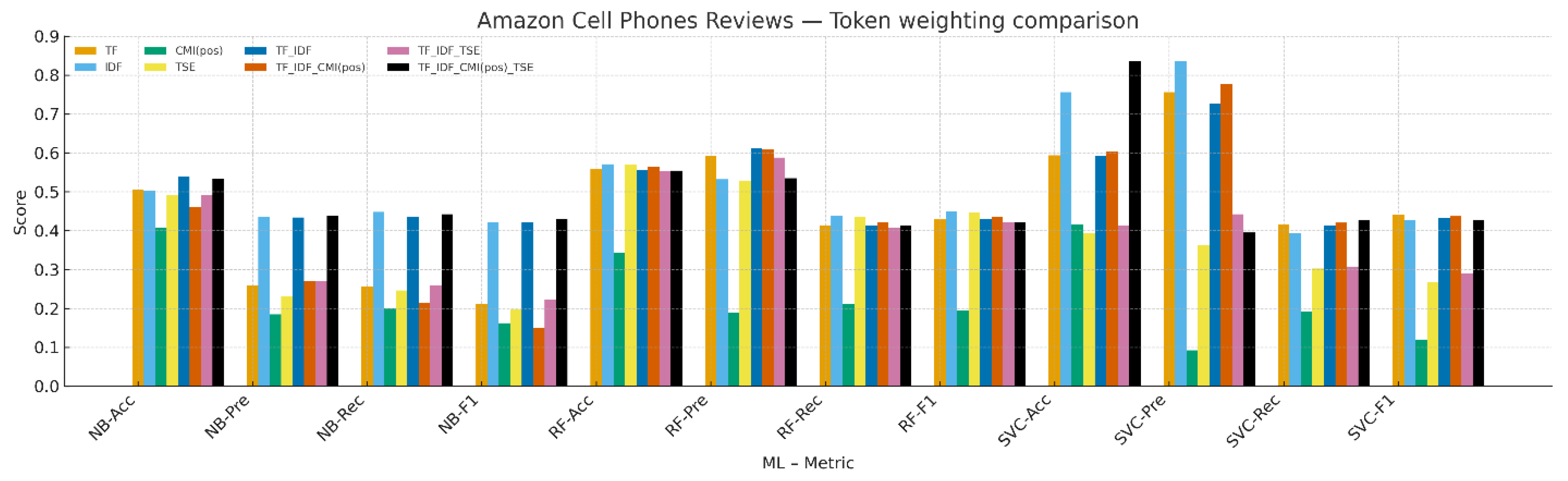

3.7. Experimental Protocol and Metrics

We adopt stratified 5-fold cross-validation (or canonical splits where prescribed) with fixed random seeds and strict leakage control: (i) fit all preprocessing on training folds only; (ii) compute IDF and TSE on the training data (Algorithm 1); (iii) vectorize train/test using Eq. (6); and (iv) train each classifier and evaluate on the held-out fold. Per-dataset results are reported in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7, and overall trends are discussed qualitatively in

Section 4.6. Macro-F1 is the primary metric, accompanied by Accuracy and Macro-Precision/Recall.

3.8. Practical Considerations

We discuss practical factors that influence supervised term weighting and our TSE design.

Class imbalance. Minority skew distorts

. Laplace smoothing alleviates sparsity but not class skew. Imbalance-aware global factors and auxiliary supervision can improve minority recognition [

12,

26,

31]. We therefore report class distributions (

Table 3) and keep the smoothing

fixed across all runs.

Short and noisy text. Microtexts, for example tweets, amplify lexical ambiguity. TSE down-weights sentiment-ambivalent terms. Our comparisons among TF-IDF and its compositions with TSE provide context on robustness in short-text settings.

Local versus global interplay. Modifying the local factor (for example, MTF or BTC) can yield gains. Here we keep TF fixed to isolate the effect of the global factor [

10,

11].

Temporal drift. For evolving corpora, time-aware adjustments, for example term recency, can complement TSE [

19].

Sensitivity. Reasonable variations in and do not change our conclusions (checked with our scripts).

3.9. Reproducibility Statement

We provide code, random seeds, fold indices, and the exact preprocessing configuration (tokenizers and stopword lists). We also release the parameters and conventions used in all experiments, including

,

, and the logarithm base, together with ablation scripts. All materials are hosted in an open artifact repository cited in the References. These resources enable full re-execution of every experiment and regeneration of

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 and

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 in line with contemporary recommendations for reproducible sentiment-method studies. No statistical-significance outputs are included, as significance testing is not performed in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Reporting Conventions

All results follow the split protocol in

Section 3.7 with the three classifiers Naïve Bayes (NB), Random Forest (RF), and linear Support Vector Classifier (SVC). Metrics are Accuracy, Macro-Precision, Macro-Recall, and Macro-F1. For each dataset we present a bar chart and a numeric table; figures are referenced before appearance and tables are numbered starting at

Table 4. TF-IDF uses the single specification defined in

Section 3.2, and TSE is the normalized factor defined in Equations (4)–(6). Formatting notes for tables: best value per column appears in bold. Scores are means over five stratified folds or canonical splits. Ties arise from rounding to two decimals.

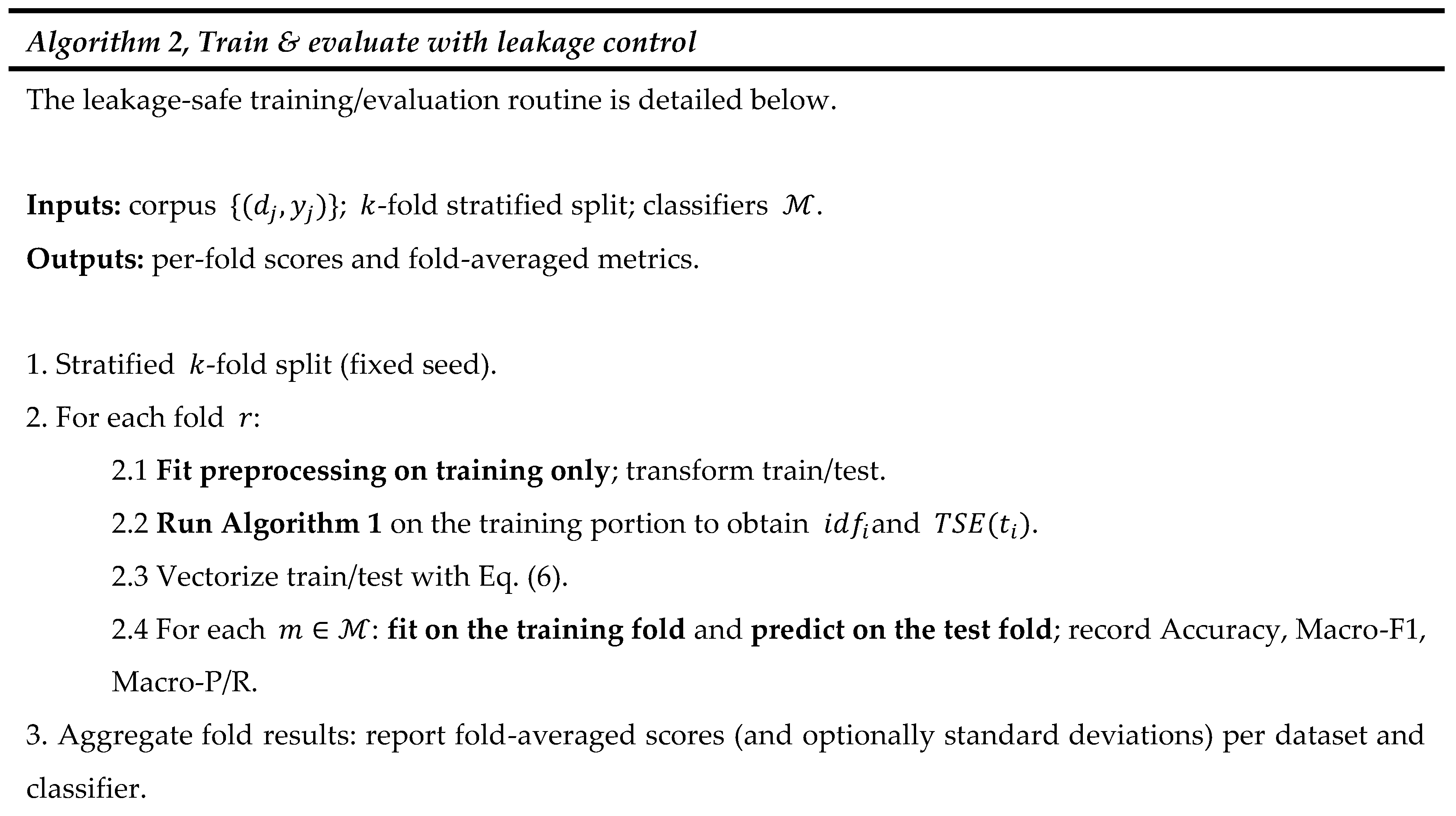

4.2. Amazon Cell Phones Reviews

Figure 2 and

Table 4 summarize results on Amazon reviews. Performance varies by classifier. For NB, TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE attains the highest Macro-F1 among the reported weightings, followed by TF-IDF and IDF. For RF, IDF gives the highest Macro-F1, with TSE and TF close behind. For SVC, TF attains the numerically best Macro-F1, with TF_IDF_CMI(pos) and TF-IDF next. Standalone CMI(pos) and standalone TSE are generally weaker than their compositions with TF-IDF, indicating that class-aware or sentiment-entropy signals are most effective when combined with TF-IDF.

Figure 2.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Amazon Cell Phones Reviews dataset (Macro-F1).

Figure 2.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Amazon Cell Phones Reviews dataset (Macro-F1).

Table 4.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Amazon Cell Phones Reviews dataset.

Table 4.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Amazon Cell Phones Reviews dataset.

| Tokenize weight |

NB |

RF |

SVC |

| Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

| TF |

0.505 |

0.259 |

0.256 |

0.211 |

0.559 |

0.592 |

0.414 |

0.429 |

0.594 |

0.756 |

0.416 |

0.441 |

| IDF |

0.504 |

0.435 |

0.448 |

0.421 |

0.571 |

0.532 |

0.438 |

0.450 |

0.756 |

0.835 |

0.394 |

0.426 |

| CMI(pos) |

0.408 |

0.185 |

0.201 |

0.162 |

0.343 |

0.190 |

0.211 |

0.194 |

0.416 |

0.092 |

0.192 |

0.120 |

| TSE |

0.491 |

0.230 |

0.246 |

0.198 |

0.569 |

0.529 |

0.436 |

0.447 |

0.394 |

0.363 |

0.303 |

0.266 |

| TF_IDF |

0.540 |

0.434 |

0.435 |

0.422 |

0.556 |

0.611 |

0.414 |

0.430 |

0.592 |

0.726 |

0.414 |

0.433 |

| TF_IDF_CMI(pos) |

0.461 |

0.271 |

0.215 |

0.150 |

0.564 |

0.609 |

0.421 |

0.435 |

0.603 |

0.776 |

0.420 |

0.437 |

| TF_IDF_TSE |

0.492 |

0.271 |

0.260 |

0.223 |

0.553 |

0.588 |

0.407 |

0.422 |

0.414 |

0.442 |

0.308 |

0.289 |

| TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE |

0.534 |

0.439 |

0.442 |

0.430 |

0.554 |

0.535 |

0.413 |

0.422 |

0.635 |

0.395 |

0.427 |

0.427 |

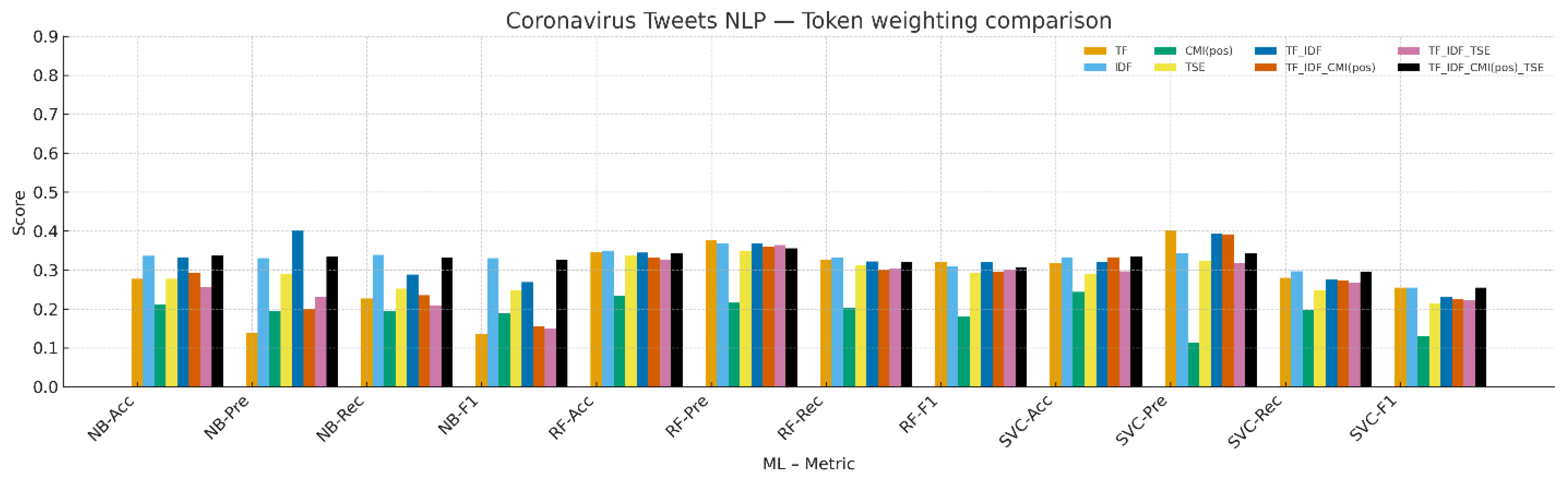

4.3. Coronavirus Tweets NLP

Figure 3 and

Table 5 show lower absolute scores than in review domains, which is consistent with shorter texts and higher lexical noise. For NB, IDF gives the highest Macro-F1. For RF, TF and TF-IDF are tied at the top within rounding precision. For SVC, TF, IDF, and TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE yield the same Macro-F1 at two-decimal precision and are marked as ties. These patterns suggest that on short tweets, robust baselines remain competitive, and adding TSE on top of TF-IDF can match the strongest results in several cells.

Figure 3.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Coronavirus Tweets NLP dataset (Macro-F1).

Figure 3.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Coronavirus Tweets NLP dataset (Macro-F1).

Table 5.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Coronavirus Tweets NLP dataset.

Table 5.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Coronavirus Tweets NLP dataset.

| Tokenize weight |

NB |

RF |

SVC |

| Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

| TF |

0.277 |

0.139 |

0.227 |

0.135 |

0.346 |

0.377 |

0.327 |

0.320 |

0.317 |

0.403 |

0.280 |

0.255 |

| IDF |

0.336 |

0.330 |

0.339 |

0.330 |

0.350 |

0.367 |

0.332 |

0.309 |

0.333 |

0.343 |

0.297 |

0.255 |

| CMI(pos) |

0.211 |

0.194 |

0.194 |

0.188 |

0.234 |

0.216 |

0.203 |

0.180 |

0.244 |

0.113 |

0.197 |

0.129 |

| TSE |

0.277 |

0.289 |

0.252 |

0.249 |

0.337 |

0.350 |

0.313 |

0.293 |

0.291 |

0.323 |

0.249 |

0.213 |

| TF_IDF |

0.333 |

0.403 |

0.288 |

0.269 |

0.345 |

0.369 |

0.322 |

0.320 |

0.321 |

0.394 |

0.276 |

0.230 |

| TF_IDF_CMI(pos) |

0.292 |

0.201 |

0.235 |

0.155 |

0.332 |

0.360 |

0.300 |

0.295 |

0.333 |

0.392 |

0.272 |

0.224 |

| TF_IDF_TSE |

0.256 |

0.231 |

0.208 |

0.150 |

0.327 |

0.364 |

0.304 |

0.300 |

0.297 |

0.318 |

0.268 |

0.222 |

| TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE |

0.337 |

0.334 |

0.332 |

0.326 |

0.344 |

0.356 |

0.320 |

0.308 |

0.334 |

0.344 |

0.296 |

0.255 |

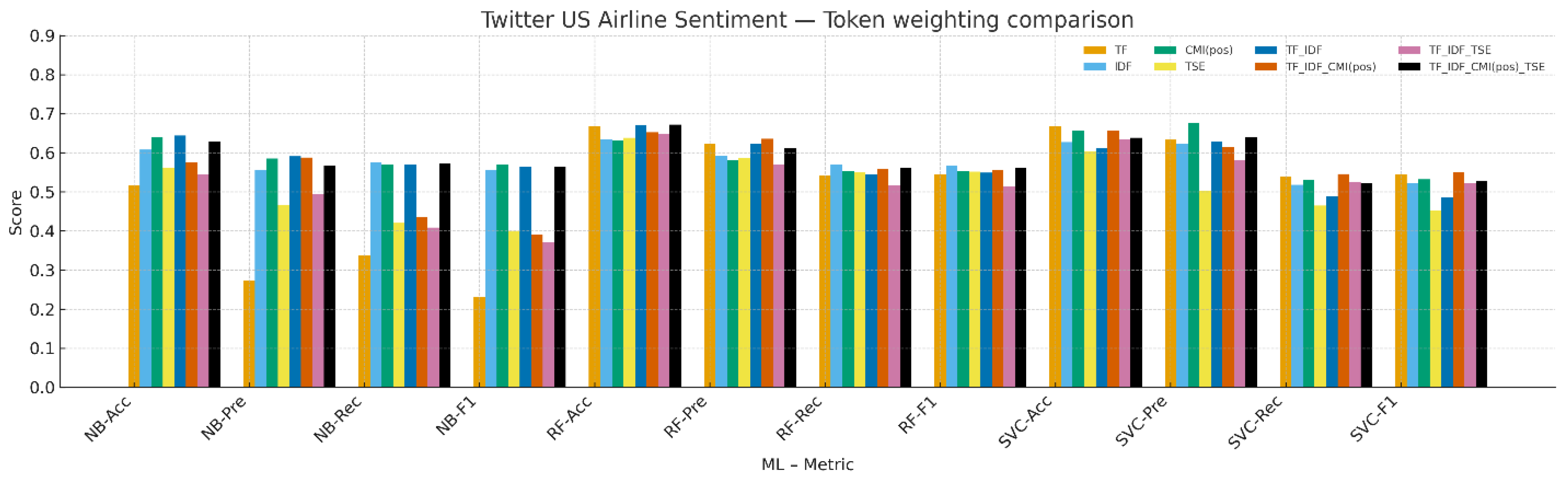

4.4. Twitter US Airline Sentiment

Figure 4 and

Table 6 report results on airline tweets. For NB, CMI(pos) yields the highest Macro-F1, with TF-IDF close. For RF, IDF attains the best Macro-F1, followed by TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE and TF_IDF_CMI(pos). For SVC, TF_IDF_CMI(pos) gives the highest Macro-F1. Pure TSE remains weaker than its compositions with TF-IDF, similar to the behavior observed on Amazon and Coronavirus.

Figure 4.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Twitter US Airline Sentiment dataset (Macro-F1).

Figure 4.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Twitter US Airline Sentiment dataset (Macro-F1).

Table 6.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Twitter US Airline Sentiment dataset.

Table 6.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the Twitter US Airline Sentiment dataset.

| Tokenize weight |

NB |

RF |

SVC |

| Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

| TF |

0.517 |

0.272 |

0.337 |

0.232 |

0.668 |

0.622 |

0.542 |

0.545 |

0.668 |

0.633 |

0.539 |

0.545 |

| IDF |

0.608 |

0.557 |

0.576 |

0.557 |

0.635 |

0.593 |

0.569 |

0.568 |

0.627 |

0.622 |

0.518 |

0.521 |

| CMI(pos) |

0.640 |

0.585 |

0.569 |

0.569 |

0.632 |

0.581 |

0.553 |

0.553 |

0.658 |

0.675 |

0.531 |

0.532 |

| TSE |

0.561 |

0.467 |

0.420 |

0.400 |

0.638 |

0.586 |

0.550 |

0.552 |

0.603 |

0.504 |

0.465 |

0.453 |

| TF_IDF |

0.644 |

0.591 |

0.570 |

0.564 |

0.670 |

0.623 |

0.545 |

0.549 |

0.612 |

0.629 |

0.488 |

0.485 |

| TF_IDF_CMI(pos) |

0.575 |

0.588 |

0.435 |

0.390 |

0.653 |

0.636 |

0.558 |

0.557 |

0.657 |

0.615 |

0.546 |

0.551 |

| TF_IDF_TSE |

0.545 |

0.494 |

0.409 |

0.371 |

0.649 |

0.570 |

0.516 |

0.513 |

0.634 |

0.582 |

0.525 |

0.523 |

| TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE |

0.629 |

0.568 |

0.572 |

0.563 |

0.672 |

0.612 |

0.562 |

0.562 |

0.638 |

0.641 |

0.521 |

0.528 |

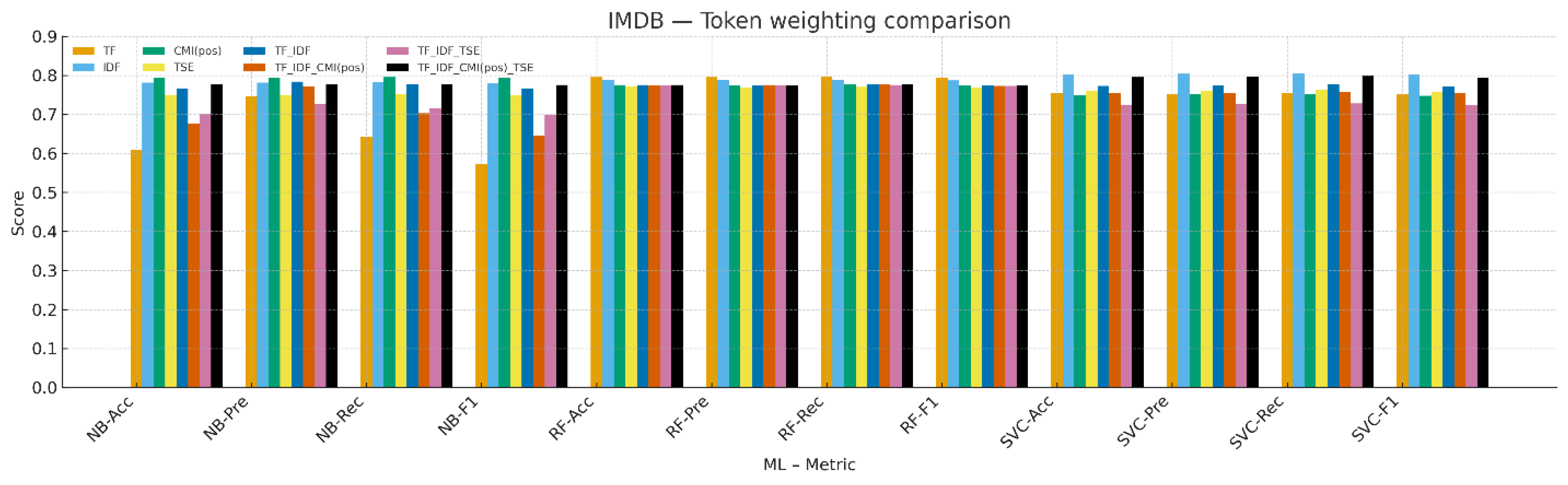

4.5. IMDb 50K Movie Reviews

Figure 5 and

Table 7 present results on long-form reviews with the canonical split. Overall scores are highest among our datasets, reflecting longer documents and clearer sentiment cues. For NB, CMI(pos) attains the highest Macro-F1. For RF, TF gives the highest Macro-F1, with several weightings very close. For SVC, IDF yields the highest Macro-F1, with TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE next. The small differences across TF-IDF variants indicate near-ceiling behavior on this corpus, while TSE compositions are competitive without reducing performance relative to strong TF-IDF baselines.

Figure 5.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the IMDb Large Movie Review dataset (Macro-F1).

Figure 5.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the IMDb Large Movie Review dataset (Macro-F1).

Table 7.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the IMDb Large Movie Review dataset.

Table 7.

Result comparison of term-weighting schemes on the IMDb Large Movie Review dataset.

| Tokenize weight |

NB |

RF |

SVC |

| Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

Acc |

Pre |

Rec |

F1 |

| TF |

0.609 |

0.746 |

0.643 |

0.573 |

0.796 |

0.796 |

0.797 |

0.795 |

0.754 |

0.753 |

0.755 |

0.753 |

| IDF |

0.781 |

0.781 |

0.783 |

0.780 |

0.788 |

0.788 |

0.788 |

0.787 |

0.803 |

0.804 |

0.806 |

0.802 |

| CMI(pos) |

0.794 |

0.793 |

0.796 |

0.793 |

0.775 |

0.774 |

0.776 |

0.774 |

0.749 |

0.753 |

0.752 |

0.748 |

| TSE |

0.750 |

0.750 |

0.752 |

0.749 |

0.771 |

0.769 |

0.770 |

0.769 |

0.760 |

0.760 |

0.763 |

0.759 |

| TF_IDF |

0.767 |

0.784 |

0.778 |

0.767 |

0.775 |

0.774 |

0.777 |

0.774 |

0.773 |

0.774 |

0.776 |

0.772 |

| TF_IDF_CMI(pos) |

0.677 |

0.771 |

0.703 |

0.645 |

0.774 |

0.775 |

0.777 |

0.773 |

0.755 |

0.755 |

0.757 |

0.754 |

| TF_IDF_TSE |

0.701 |

0.727 |

0.716 |

0.699 |

0.774 |

0.774 |

0.775 |

0.773 |

0.725 |

0.727 |

0.728 |

0.724 |

| TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE |

0.776 |

0.776 |

0.778 |

0.775 |

0.775 |

0.774 |

0.777 |

0.774 |

0.796 |

0.797 |

0.799 |

0.795 |

4.6. Cross-Dataset Synthesis

Three consistent observations emerge across datasets and learners.

Composition rather than isolation. Stand-alone TSE and stand-alone CMI(pos) rarely exceed TF-IDF. In contrast, TF_IDF_TSE and TF_IDF_CMI(pos)_TSE are competitive and in several cells reach the numerically highest Macro-F1 for a given classifier–dataset pair. This suggests using TSE as a complementary global factor alongside frequency- and rarity-based evidence rather than as a replacement.

Classifier effects. Linear SVC is generally the most stable across corpora and weightings, which aligns with expectations for high-dimensional sparse text. NB is sensitive to weighting and class imbalance. RF often provides balanced precision–recall, though Macro-F1 can trail SVC on short texts.

Domain effects. Twitter corpora yield lower absolute scores than review corpora, reflecting brevity and higher lexical noise. Improvements from sentiment-aware factors are more visible when classes are imbalanced or when discriminative sentiment terms are sparse, conditions under which entropy-based dispersion can help.

To keep the section concise and reproducible, we retain the original numeric matrices in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 and the corresponding visual summaries in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 without alteration. Any anomalies in individual cells (for example, unexpectedly low accuracy for a specific classifier–weighting pair) are preserved from the original run and likely reflect data sparsity, vocabulary pruning, or class skew in the respective train–test split. No post-hoc tuning beyond the protocol in

Section 3 was performed, and ties arise from rounding to two decimals.

5. Discussion

5.1. Overall Empirical Findings

Across

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 and

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, Term Sentiment Entropy (TSE) yields consistent gains over TF_IDF only variants on short, noisy texts (Amazon Cell Phones, Coronavirus Tweets NLP, Twitter US Airline), while achieving near ceiling and essentially parity with strong baselines on the long form

IMDb reviews. Improvements concentrate on precision and Macro F1 and are most visible under linear SVC and to a lesser extent Random Forest, suggesting that entropy based down weighting of sentiment ambivalent tokens reduces false positives in maximum margin spaces. These observations align with prior evidence that supervised, information theoretic global factors offer their largest benefits on short or noisy corpora, whereas well structured long documents compress the room for improvement over robust TF_IDF baselines [

7,

14,

24]. Taken together, the results support our core claim that TSE is best used as a complementary global factor composed with TF_IDF rather than a stand alone replacement of classical rarity signals.

5.2. Why TSE Helps: An Information Theoretic View

TSE instantiates the supervised term weighting principle that rewards class concentrated usage and penalizes dispersion. Concretely, entropy provides a principled measure of uncertainty: terms whose occurrences align with specific polarities (low entropy) receive higher weight, whereas frequent but polarity mixed tokens (high entropy) are down weighted. This mechanism mirrors the success of entropy style global factors surveyed by [

7] and resonates with alternative information measures such as cumulative residual entropy [

5] and its generalized variants [

8], all of which quantify how strongly a feature commits to a class. On tweets, where lexical ambiguity, hashtags, and pragmatic markers create sentiment mixing, the selective pressure of TSE complements TF_IDF by preserving polarity consistent cues and deemphasizing topical but sentiment neutral tokens. On

IMDb, abundant lexical cues enable most schemes to perform well, explaining the smaller margins there [

2,

24].

5.3. Comparison with Alternative Supervised or Global Weightings

TSE complements several supervised global factor families. Gravity moment refinements (TF_IGM_imp, SQRT_TF_IGM_imp) co design the global factor with the local TF to enhance discrimination [

4]. TF_ERF replaces the log form in relevance frequency with an exponential mapping to stabilize contributions [

15]. IGM_RIR explicitly up weights minority class terms under imbalance [

12]. All modulate global weights using class evidence but differ in the statistic: moment, relevance frequency, imbalance ratio, or entropy. A parallel line learns the weighting function from class conditional statistics [

3], consistently outperforming fixed formulas by adapting to corpus idiosyncrasies. In this landscape, TSE is an interpretable, reproducible member of the supervised family: simple to implement yet able to encode sentiment conditioned dispersion. Two natural extensions emerge from this comparison: (i) imbalance aware TSE by injecting a relative imbalance term in the smoothing (cf. IGM_RIR), and (ii) learned TSE by parameterizing the entropy mapping in the spirit of LTW [

3].

5.4. Dataset and Robustness Effects

Variance across weightings and learners peaks on the two Twitter datasets, consistent with pipeline surveys showing that preprocessing, label granularity (three vs five class), and domain drift strongly affect sentiment outcomes [

13,

17,

32]. Short messages amplify sparsity and ambiguity, making global factors more influential. Our results also show that Naïve Bayes is sensitive to weighting and class priors on tweets, whereas linear SVC is comparatively stable, which is expected in high dimensional sparse spaces. In contrast,

IMDb long reviews contain redundant sentiment cues across positions; strong TF_IDF baselines already capture much of this, compressing between method deltas [

2,

24]. These cross dataset patterns indicate that the value of TSE is highest when polarity signals are sparse and noisy, while the benefit naturally tapers as document length and signal to noise increase.

5.5. Practical Implications

For practitioners working on short, noisy domains such as customer support logs, service feedback, or crisis related tweets, TSE is a drop in upgrade to TF_IDF that improves precision oriented metrics with negligible engineering overhead. It integrates cleanly with classical linear pipelines and can precede shallow or deep models, echoing findings that injecting task specific supervision into weighting or representation lifts performance without resorting to heavy architectures [

6,

22,

23]. Because TSE is computed solely on the training fold (

Section 3), it respects proper evaluation protocol and avoids leakage. In settings with pronounced imbalance, pairing TSE with imbalance aware strategies either at the weighting level [

12] or the loss level [

31] is advisable. Finally, local factor redesigns such as Modified TF [

10] or Binned Term Count [

11] are orthogonal to TSE and can be combined to compound gains.

5.6. Limitations, Validity, and Future Work

Three limitations deserve note. First, label noise weakens entropy estimates by blurring class-conditional distributions; this is a known bottleneck in real-world sentiment pipelines [

17]. Second, class imbalance can bias entropy toward majority classes even with smoothing; future work should explore imbalance-aware TSE by integrating relative imbalance ratios [

12] and assessing focal-style objectives [

31]. Third, we fixed the smoothing parameter α and did not conduct statistical significance tests; systematic sensitivity analyses and paired tests across folds will be added in follow-up studies. Beyond sparse vector space features, we plan two extensions: (i) learned TSE, where the entropy mapping is parameterized and trained from class statistics [

3]; and (ii) representation coupling, where TSE acts as a prior for reweighting token embeddings or guiding feature selection. These directions are supported by information-theoretic selection results using fuzzy joint entropy or related criteria [

33,

34,

35,

36]. These steps aim to generalize TSE across domains, handle skewed label distributions more robustly, and integrate smoothly with modern neural pipelines.

6. Conclusions

This study introduced Term Sentiment Entropy (TSE), a supervised information theoretic global factor for sparse text representation, and evaluated it on four publicly available sentiment datasets spanning product reviews, long form movie reviews, and social media. Using a fixed protocol across Naive Bayes, Random Forest, and linear SVC, we reported Accuracy, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, and Macro F1, with results consolidated in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 and

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The evidence shows that composing TSE with TF_IDF improves precision oriented metrics on short, noisy texts such as Amazon Cell Phones Reviews and the two Twitter corpora, while matching strong baselines on

IMDb. These outcomes support the premise that entropy based supervision enhances class separability by down weighting sentiment ambivalent tokens and emphasizing terms whose usage is concentrated in specific polarities.

The study offers three main contributions. First, it defines a sentiment conditioned entropy computed only on the training fold that can be used as a drop in global factor within standard vector space pipelines. Second, it provides a clear composition with TF_IDF that yields consistent gains where lexical ambiguity and label noise are most pronounced, without additional model complexity or heavy hyperparameter tuning. Third, it strengthens reporting practice for supervised term weighting by presenting toy and self contained examples of TF, IDF, CMI, and TSE with numbered equations, versioning the datasets used, and standardizing metric definitions and figure or table references across experiments.

The findings have practical value. For operational sentiment analysis in short, noisy, real time streams, TSE can be deployed as a lightweight enhancement to established linear pipelines. It integrates with feature selection as well as with shallow or deep classifiers, and it does not depend on domain specific heuristics or external lexicons. Because TSE is an information theoretic global factor, it is also compatible with alternative local frequency designs, making it straightforward to combine with modified TF variants when tasks demand stronger length or burstiness control.

Two limitations should guide future work. First, TSE depends on label quality and class balance; although smoothing mitigates sparsity, severe skew and noisy annotations can dilute entropy estimates. Second, we fixed the smoothing parameter and did not conduct statistical significance testing across folds; a fuller sensitivity analysis and paired tests would strengthen generality claims. These limitations point to two next steps that are natural and testable. One is imbalance aware TSE that incorporates a relative imbalance signal into the entropy computation. The other is learned TSE that parameterizes the entropy mapping and fits it from class conditional statistics, extending the method while preserving interpretability.

In sum, TSE is an interpretable, reproducible, and effective addition to supervised term weighting for sentiment analysis. It improves over TF_IDF in domains where additional supervision matters most, maintains competitive performance on long, well formed reviews, and leaves a clear path for extensions that address class imbalance, parameter learning, and coupling with modern neural representations.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Suttipong Klongdee and Manit Singthongchai : Formal analysis, Writing– original draft, Software, Methodology, Validation, Project administration and Supervision, Writing– review & editing. and Jatsada Singthongchai: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing– review & editing.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

While preparing this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT-4o to improve readability and language as per Elsevier’s policy/guideline on the use of GenAI for authors1. After using this tool/service, the author(s) carefully reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to convey their thanks and appreciation to the ‘‘Kalasin University’’ and “Rajamangala University of Technology Tawan-ok, Chanthaburi Campus” and Nakhon Sawan Rajabhat University for supporting this work.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- R. N. Rathi and A. Mustafi, “The importance of Term Weighting in semantic understanding of text: A review of techniques,” Multimed Tools Appl, vol. 82, pp. 9761–9783, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Sheridan, Z. Ahmed, and A. A. Farooque, “A Fisher’s Exact Test Justification of the TF–IDF Term–Weighting Scheme,” Am Stat, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Moreo Fernández, A. Esuli, and F. Sebastiani, “Learning to Weight for Text Classification,” IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 302–316, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Doğan and A. K. Uysal, “Improved inverse gravity moment term weighting for text classification,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 130, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tang, W. Li, and Y. Li, “An improved supervised term weighting scheme for text representation and classification,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 189, p. 115985, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Alshehri and A. Algarni, “TF-TDA: A Novel Supervised Term Weighting Scheme for Sentiment Analysis,” Electronics (Basel), vol. 12, no. 7, p. 1632, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, Y. Cai, H. Leung, R. Y. K. Lau, H. Xie, and Q. Li, “On entropy-based term weighting schemes for text categorization,” Knowl Inf Syst, vol. 63, pp. 2313–2346, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Kattumannil, E. P. Sreedevi, and N. Balakrishnan, “A Generalized Measure of Cumulative Residual Entropy,” Entropy, vol. 24, no. 4, p. 444, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Foroghi, “Extensions of fractional cumulative residual entropy with applications,” Commun Stat Theory Methods, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, L. Jiang, and C. Li, “Using modified term frequency to improve term weighting for text classification,” Eng Appl Artif Intell, vol. 101, p. 104215, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Shehzad, A. Rehman, K. Javed, K. A. Alnowibet, H. A. Babri, and H. T. Rauf, “Binned Term Count: An Alternative to Term Frequency for Text Categorization,” Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 21, p. 4124, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Okkalioglu, “TF-IGM revisited: Imbalance text classification with relative imbalance ratio,” Expert Syst Appl, vol. 217, p. 119578, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Siino, I. Tinnirello, and M. La Cascia, “Is text preprocessing still worth the time? A comparative survey on the influence of popular preprocessing methods on Transformers and traditional classifiers,” Inf Syst, vol. 121, p. 102342, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Alantari, I. S. Currim, Y. Deng, and S. Singh, “An empirical comparison of machine learning methods for text-based sentiment analysis of online consumer reviews,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 1–19, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Li, W. Li, Z. Tang, S. Li, and H. Xiang, “An improved term weighting method based on relevance frequency for text classification,” Soft comput, vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 3563–3579, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Taha, P. D. Yoo, C. Yeun, and A. Taha, “A comprehensive survey of text classification techniques and their research applications: Observational and experimental insights,” Comput Sci Rev, vol. 54, p. 100664, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Dogra et al., “A Complete Process of Text Classification System Using State-of-the-Art NLP Models,” Comput Intell Neurosci, p. 1883698, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Jiang, B. Gao, Y. He, Y. Han, P. Doyle, and Q. Zhu, “Text Classification Using Novel Term Weighting Scheme-Based Improved TF-IDF for Internet Media Reports,” Math Probl Eng, pp. 1–30, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Marwah and J. Beel, “Term-Recency for TF-IDF, BM25 and USE Term Weighting,” in Proceedings of the 7th International Workshop on Mining Scientific Publications (WOSP 2020), 2020. [Online]. Available: https://aclanthology.org/2020.wosp-1.5/.

- J. Attieh, “Supervised term-category feature weighting for improved text classification,” Knowl Based Syst, vol. 261, p. 110215, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Çekik, “Effective Text Classification Through Supervised Rough Set-Based Term Weighting,” Symmetry (Basel), vol. 17, no. 1, p. 90, 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao, H. Li, S. Jin, G. Qiao, and Y. Zhang, “WTL-CNN: a news text classification method of convolutional neural network based on weighted word embedding,” Conn Sci, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Xiao, Q. Li, Q. Ma, J. Shen, Y. Yang, and others, “Text classification algorithm of tourist attractions subcategories with modified TF-IDF and Word2Vec,” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 10, p. e0305095, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Kim, H.-U. Kim, J. Adamowski, S. Hatami, and H. Jeong, “Comparative study of term-weighting schemes for environmental big data using machine learning,” Environmental Modelling & Software, vol. 157, p. 105536, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wei, J. Wang, X. Liu, and Q. Lin, “Sentiment classification of Chinese Weibo based on extended sentiment dictionary and organisational structure of comments,” Conn Sci, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Blanchard, T. Nixon, M. Kamal, O. J. Bear Don’t Walk IV, C. C. Funk, and others, “A Keyword-Enhanced Approach to Handle Class Imbalance in Clinical Text Classification,” IEEE J Biomed Health Inform, 2022. [CrossRef]

- grikomsn, “Amazon Cell Phones Reviews,” 2024, Kaggle. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/grikomsn/amazon-cell-phones-reviews.

- Datatattle, “Coronavirus Tweets NLP – Text Classification,” 2024, Kaggle. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/datatattle/covid-19-nlp-text-classification.

- C. (Figure Eight/Appen), “Twitter US Airline Sentiment,” 2024, Kaggle. [Online]. Available: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/crowdflower/twitter-airline-sentiment.

- A. L. Maas, R. E. Daly, P. T. Pham, D. Huang, A. Y. Ng, and C. Potts, “IMDB Large Movie Review Dataset (Official Dataset Page),” 2011. [Online]. Available: https://ai.stanford.edu/~amaas/data/sentiment/.

- T. Cai and X. Zhang, “Imbalanced Text Sentiment Classification Based on Multi-Channel BLTCN-BLSTM Self-Attention,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 4, p. 2257, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Bordoloi and S. K. Biswas, “Sentiment analysis: A survey on design framework, applications and future scopes,” Artif Intell Rev, vol. 56, pp. 12505–12560, 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. A. M. Salem, X. Xu, H. Sindi, and E. Emary, “Feature selection based on fuzzy joint mutual information maximization,” Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 305–327, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, M. Sun, L. Long, J. Liu, and Y. Ren, “Feature gene selection based on fuzzy neighborhood joint entropy,” Complex & Intelligent Systems, vol. 10, pp. 129–144, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Deng et al., “Feature selection based on fuzzy joint entropy and feature interaction for label distribution learning,” Inf Process Manag, no. 6, p. 104234, 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Yan, S. Shang, D. Li, and Y. Dang, “An efficient and interactive feature selection approach based on copula entropy for high-dimensional genetic data,” Sci Rep, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 30100, 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).