1. Introduction

The use of the Internet has become a daily practice, present in almost all areas of our lives, from work or school activities, to commerce, food, leisure, entertainment, among many others. Therefore, it is currently difficult to find, consume or carry out activities that are not linked to the Internet. Since its inception in 1983, the number of users using this tool has grown exponentially to reach the latest figure, recorded at the end of 2022, of 5,282 million users worldwide (around 66% of the total population) (Statista, 2022).

One of the reasons why the number of Internet users has grown so much in such a short time is due to the great advantages and benefits it provides, such as access to updated information, a greater possibility of communicating with other people, ease and convenience when shopping, working remotely, etc. However, despite all these positive aspects, there are also many other negative aspects related to its use, due precisely to its accessibility characteristics and the wide range of services that this tool offers (Plaza de la Hoz, 2018). This accessibility can lead to overuse, thus increasing the risk of the appearance of the so-called Problematic Internet Use (PIU) or Internet Addiction (IA).

Both terms, Internet Addiction and Problematic Internet Use, refer to inappropriate use of the Internet. The difference is that the first one points to aspects of a more psychopathological nature, while the second one focuses on the description of behaviours and thoughts associated with this misuse (Gómez & Muñoz, 2005).

This problem can manifest itself in two ways, generalised or specific (Davis, 2005; Machimbarrena et al., 2023). When it manifests in a generalised form, the individual makes a general inappropriate use of the Internet where their behaviour does not have a specific purpose, but, due to difficulties in the social area, they use this network as a way of interacting with the outside world. However, when manifested in a specific way, the use of the Internet is focused specifically on one activity (e.g. online shopping), as the person has pre-existing clinical conditions that lead to these behaviours, and Internet use may exacerbate these conditions. If the person could not express their problem through the Internet, they would do so through another medium.

The role of electronic devices, such as the use of mobile phones or tablets, should be taken into account. These are very present in everyday life and are closely related to the use of the Internet, so their use would also be susceptible to the emergence of this inappropriate use of the Internet (Pérez et al., 2021).

Online gaming can be found within the use of the Internet. There is literature that alludes to the problems that this practice can entail, including terms such as Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) (Carbonell, 2014) which is considered a non-substance addictive disorder whose main characteristic is the recurrent and persistent participation in online video games over time, leading to clinically significant distress (Carbonell, 2014) or terms such as Problematic Online Gaming (POG) (Király et al., 2014) that allude to a problematic use of this practice. Moreover, these are closely related to gambling, a practice with which they seem to be converging more and more, as they share many characteristics and, due to the Internet, are carried out on the same level (Kim & King, 2020). However, there are no conclusive results regarding the relationship between PIU and online gaming, as other authors (Király et al., 2014; López-Fernández, 2018) claim that the relationship between these two entities is weak and should be considered separate entities, while other authors (Machimbarrena et al., 2023) defend the positive association between them.

Therefore, the term IA will be used in this study to refer to Internet addiction (IA) itself, to problematic Internet use (PIU) and to the generalised use of any digital technology, excluding gaming and gambling, as no conclusive results have been found in recent literature.

Adolescents are the most vulnerable group to develop this addiction, as, at this stage of life, they are particularly sensitive to the social environment in which they live. Easy access through devices such as mobile phones or tablets makes the Internet use an important part of their daily lives (Li et al, 2014; Castellana et al., 2007)

Through this technology, adolescents have a means of learning, communication, leisure and fun, making this technology an essential part of their daily lives. Thanks to the Internet, communication with peers also becomes easier since the physical distance between interlocutors is no longer a problem. In addition, anonymity and the absence of eye contact facilitate interaction, masking identity and facilitating the communication of unpleasant topics or emotions (Castellana et al., 2007; Peris et al., 2020).

Likewise, some difficulties specific to adolescence have been pointed out, such as omnipotence, the tendency to externalize guilt, the search for sensations, lack of self-control, the difficulty of recognizing addictive behaviors or the normalization of risky behaviors that, together with the limited life experience, can increase the risk of developing addictions (Castellana et al., 2007; Peris et al., 2020).

The real problem of problematic Internet use, or Internet addiction, lies in the future repercussions that this misuse has on the mental health of these adolescents (Lai et al., 2022) hence the importance of education for the development of good habits during this stage (Contreras et al., 2019).

It is estimated that 14% of young people between 10 and 19 years of age suffer from some type of mental disorder (World Health Organization, 2021). The most frequent during this age group are anxiety and depression disorders (prevalence of 42.9%), conduct disorders (prevalence of 20.1%), attention and hyperactivity disorders (prevalence of 19.5%), intellectual and developmental disabilities (prevalence of 14.9%) and other mental disorders (prevalence of 9.5%) (Unicef Data, 2024).

As can be seen, anxiety disorders and depression are the most prevalent during adolescence, followed by conduct disorders (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and dissocial disorder (DD)).

Finally, suicide is another of the main mental health problems in adolescence, which has increased in recent years, mainly due to the economic and health crisis, and has been considered the fourth leading cause of death in this age group (Unicef Data, 2024). Young people aged 15-29 years are considered to be one of the most vulnerable groups, with a higher prevalence in men (2:1) (Unicef Data, 2024).

Authors such as Pedrero et al. (Pedrero et al., 2012) report higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress and psychological discomfort, greater difficulty in expressing emotions, low self-control, low self-esteem, insomnia and a greater likelihood of suffering psychological disorders as a result of Internet abuse. Other authors (Echeburúa & de Corral, 2010) explain that these mental health problems derive from Internet dependence, as Internet abuse will lead to a loss of control, with withdrawal symptoms appearing and resulting in increased levels of anxiety, depression and irritability. All this leads to a progressive increase in tolerance, increasing the time spent online with negative repercussions in all areas of their lives (personal, emotional, social, academic and family).

Furthermore, problematic Internet use also appears to be related to substance use (Rücker et al., 2015). Evidence has been found of a direct relationship with tobacco use, but also with alcohol, cannabis and other illegal drugs, but in these cases, consumption seemed to be mediated by tobacco use (Rücker et al., 2015). Thus, Internet addiction would constitute a risk factor for the development of other addictive behaviours (Rücker et al., 2015).

Finally, in relation to suicidal behaviours, authors such as Bousoño et al. (2017) considered that, although some elements of internet use may act as protective factors, in general, Internet misuse is associated with an increased risk of suicidal ideation, self-harm and depression.

Based on previous studies, some variables were identified as possible moderators that may contribute to inconsistency in the findings on associations between problematic Internet use and mental health outcomes.

There is evidence that being male or female may contribute to differences in this relationship. Some studies showed that the associations of problematic internet use with depressive symptoms (Wallburg et al., 2016, Lozano-Blasco & Cortes-Pascual, 2020), loneliness (Cai et al., 2023) and anxiety (Baloğlu, 2018) were stronger for men than for women. However, findings to the contrary were also found (Lei et al., 2020), as well as findings that showed no differences between gender groups for other variables such as depression, anxiety and subjective well-being (Cai et al., 2023).

Regarding age as a moderating variable, Lei et al. (2020) observed that the relationship between excessive Internet use and subjective well-being, as well as positive emotions, was stronger in younger students compared to university students. This finding suggests that age may influence how Internet use affects well-being, especially at earlier stages of development. In contrast, Huang (2010) and Lozano-Blasco & Cortes-Pascual (2020) found no significant results in their analysis.

Geographic region as a moderating variable has been shown to be significant in several analyses. Cai et al. (2023) found that study region acted as a statistical moderator for the observed heterogeneity in correlations between problematic Internet use and depressive symptoms, loneliness and other mental health outcomes. Specifically, these associations were stronger in studies conducted in South Asia and Europe, compared to other regions coded in their meta-analysis (Europe, West Asia and East Asia). The same was true for the study by Lei et al. (2020) who observed that the link between negative emotions and excessive Internet use was stronger in studies with participants from central and western China than in those with participants from eastern China. In contrast, Lozano-Blasco & Cortes-Pascual (2020) found no significant evidence in their analysis.

These findings highlight the importance of considering such variables as moderating factors in the present research.

Recent meta-analytic studies have found evidence of a relationship between problematic Internet use and the appearance of internalizing symptomatology such as depression, anxiety, loneliness, self-esteem or subjective well-being in adolescent or young adult populations (Lozano-Blasco, R., & Cortes-Pascual, A.,2020; Cai et al., 2023; Lei et al., 2020; Huang, 2010; Çikrikci, 2016), see

Table 1.

Cai et al. (2023) found that higher levels of PIU were associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety and loneliness, and lower subjective well-being. Lozano-Blasco & Cortes-Pascual (2020) focused on depressive disorder in adolescents aged 13-17, observing an increase in depressive disorder with higher Internet use. Lei et al. (2020) identified that PIU is negatively correlated with subjective well-being, life satisfaction and positive emotions, and positively correlated with negative emotions. Huang (2010) and Çikrikci (2016) revealed lower well-being when PIU scores were higher, assessing components such as self-esteem and life satisfaction.

As can be seen in

Table 1, research on the relationship between Internet addiction and externalizing problems in adolescents has been less investigated. In order to obtain more information about the role of these variables in addiction or problematic Internet use, in addition to aggressiveness, externalizing symptomatology (externalizing problems (referring to general measures and impulsiveness) has been included.

This review examines the relationship between Internet addiction/problematic Internet use and mental health, taking into account both internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, and focusing on the adolescent population. A meta-analytic approach was used to determine the impact of Internet use on adolescent mental health, and two objectives were set: a) to identify the relationship between inappropriate Internet use (IA or PIU) and the most prevalent mental health variables in young people; b) to quantify the strength of the relationship in each of them and the possible moderating variables (mean age, SD age, gender, JBI score, continent and study desing).

2. Materials and Methods

Following the objectives stated in this article, literature review was carried out on the relationship between Internet addiction and mental health to determine and quantify the impact of Internet use on adolescent mental health.

The PRISMA guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses was followed.

Table S1 (in the Supplementary Material) includes the PRISMA guide checklist applied to our study (Page et al., 2021). In addition, registration in the international systematic review database, PROSPERO, was carried out on 30 January 2024 (National Institute for Health and Care Research, s.f).

2.1. Study Selection Criteria

Specific criteria were established for the inclusion of relevant articles in the analysis. These criteria included the selection of empirical and quantitative research articles, with a focus on the adolescent population, aged 11-18 years, and written in English or Spanish. Articles were considered from any country of publication that primarily addressed the relationship between addiction or problematic Internet use and mental health. In addition, the search was limited to articles published in the last five years, from 2019 to 2023.

On the other hand, we excluded studies that focused on video games, gaming or Covid-19, as well as those with a sample size of less than 30 participants. In addition, articles whose main focus was not on Internet use or which relegated Internet use to a secondary role were discarded.

2.2. Search Strategy

To retrieve relevant studies in the field of Internet addiction or problematic Internet use and health, all the database collections of Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, All Database) were used, which includes bibliographic references of articles of scientific and academic interest in its core collection (Web of Science Core Collection) composed by eight databases: Medline, Current Contents Connect, SciELO Citation Index, Derwent Innovations Index, Grants Index, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Preprint Citation Index and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Citation Index

The search was conducted in all Web of Science databases on 25 March 2023, limiting the search to the last 5 years in the research areas of psychology, behavioural sciences and pediatrics and selecting English and Spanish as the language. This search was replicated by two more researchers

The combination of terms entered into the search was:

((((TS=(Internet addiction or excessive internet use or problematic internet use or digital technology use)) AND TS=(teenagers or adolescents or teens or youth)) AND TS=(mental health or mental illness or mental disorder or psychiatric illness or psychological consequences or psychological effect or psychological impact or psychological problems or psychological wellbeing or psychological well-being or psychological wellbeing)) NOT TS=(gaming)) NOT TS=(covid-19 or coronavirus or 2019-ncov or sars-cov-2 or cov-19) NOT TS= (university students or college students or undergraduate students).

2.3. Study Selection

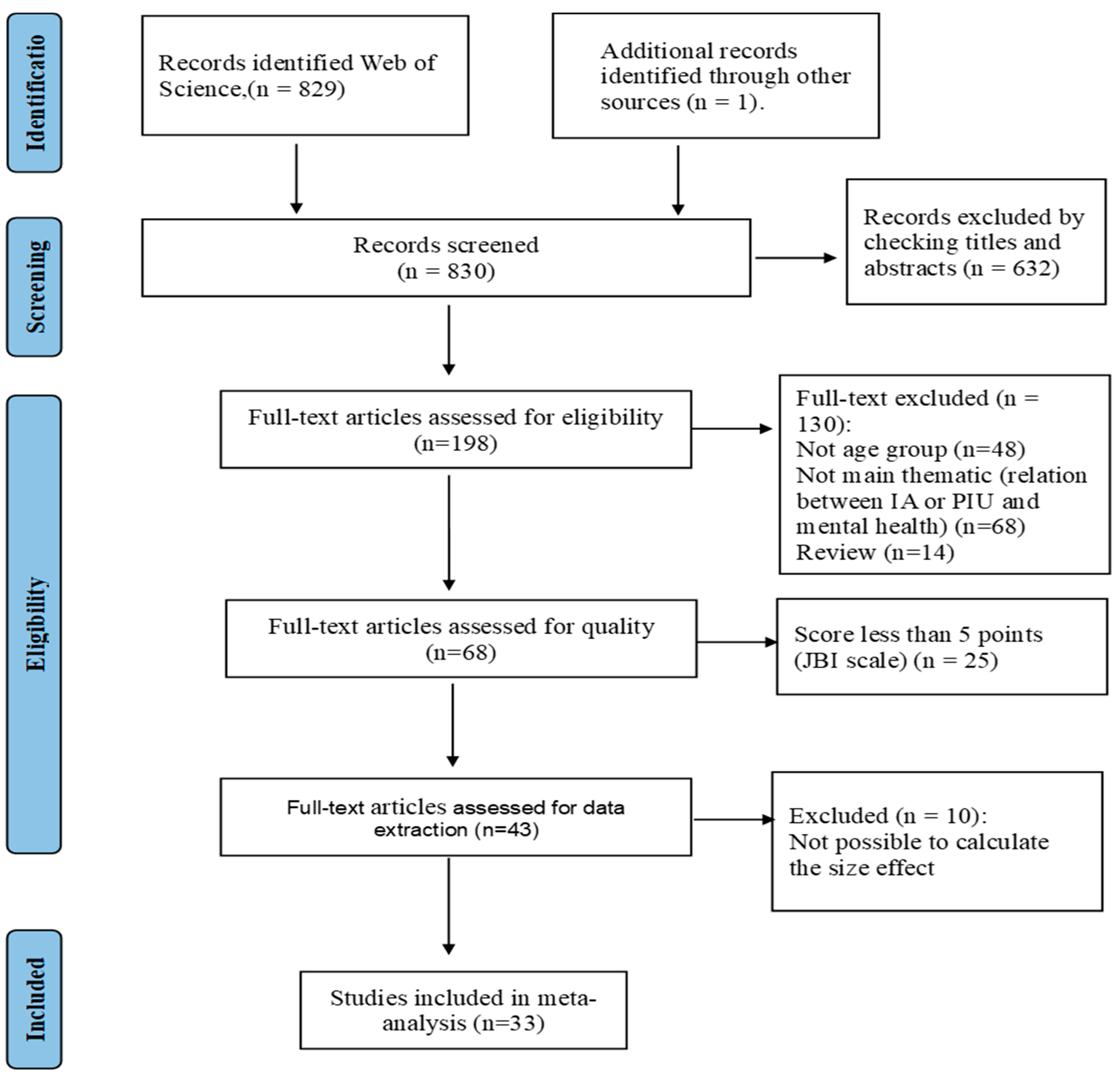

After the first search, as can be seen in the flow chart below (

Figure 1), the total number of articles found was 830. Subsequently, after screening by title and abstract, the number decreased to 198 articles, of which, after a complete reading and application of the selection criteria, the number decreased to 68 articles.

After assessment of the methodological quality of these articles (following the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist), 25 articles were eliminated for scoring less than 5 points on this scale, leaving 43 articles. Finally, 10 articles were eliminated because they did not provide sufficient quantitative information to calculate the effect size, leaving 33 articles.

2.4. Data extraction from the Selected Studies and Coding of Variables

Once the final articles were selected for review, a data extraction procedure, based on variable, coding was followed. Each study was reviewed by two trained coders using a standard list of variables

These were divided into the following variables: extrinsic, substantive, methodological and outcome. The register carried out can be seen in

Table S3 (in the

Supplementary Material).

Extrinsic variables include data referring to the code of each article, authors' citations, number of authors, year of publication and the article's quality score (total and percentage).

For the substantive variables we find those referring to subject and sample variables (sample size, percentage of women, mean and standard deviation of age and nationality)

Methodological variables refer to design variables and variables related to Internet addiction, depression, anxiety, stress, suicidal behaviour (referring to suicidal behaviour or self-harm), psychological well-being, externalizing problems and internalizing problems (where descriptors and instruments are recorded).

Finally, the outcome variables refer to the statistic used and the numerical result of the relationship between Internet addiction with depression, anxiety, stress, suicidal behaviour (referring to suicidal behaviour or self-harm), psychological well-being, self-esteem, body image, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, tobacco use, alcohol use, aggressiveness, impulsiveness and delinquent behaviour

2.5. Computation of Effect Sizes

The effect size index was the Pearson’s correlation coefficient calculated between mental health constructs and internet addiction. For each study, the Pearson’s correlations were transformed into the Fisher’s Z metric to normalize distributions and stabilize variances. To make their interpretation easier, the Fisher’s Z values for the individual effect sizes, the mean effect sizes and their confidence limits were back transformed into Pearson correlation metric (Borenstein et al., 2009).

Although most of the studies included reported the results in terms of correlations, some studies that did not directly report correlation coefficients. For example, if the study reported the results by means of means and standard deviations or odds ratio, conversion formulas were applied to transformed then into correlation coefficients (for more details see Sánchez-Meca et al. (2003)). If the study reported the results by means of medians approximation methods were applied to estimate the means and standard deviations (for more details see Wan et al. (2014)).

Effect sizes were calculated for each mental health construct: depression, anxiety, stress, psychological well-being, self-esteem, externalizing problems, aggressiveness, impulsiveness and suicidal behaviour. In all cases, positive correlations indicated a positive relationship between mental health and internet addiction, and negative correlations indicated a negative relationship between mental health and internet addiction.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Separate meta-analyses were carried out to assess the relationship between each mental health construct (depression, anxiety, stress, psychological well-being, self-esteem, externalizing problems, aggressiveness, impulsiveness, suicidal behavior) and Internet addiction.

As variability was expected in effect sizes, random-effects models were assumed (Borenstein et al., 2009). These models involve weighting each effect sizes by its inverse variance, defined as the sum of the within-study variance and between-study variance, the latter being estimated by restricted maximum likelihood (Cooper et al., 2019).

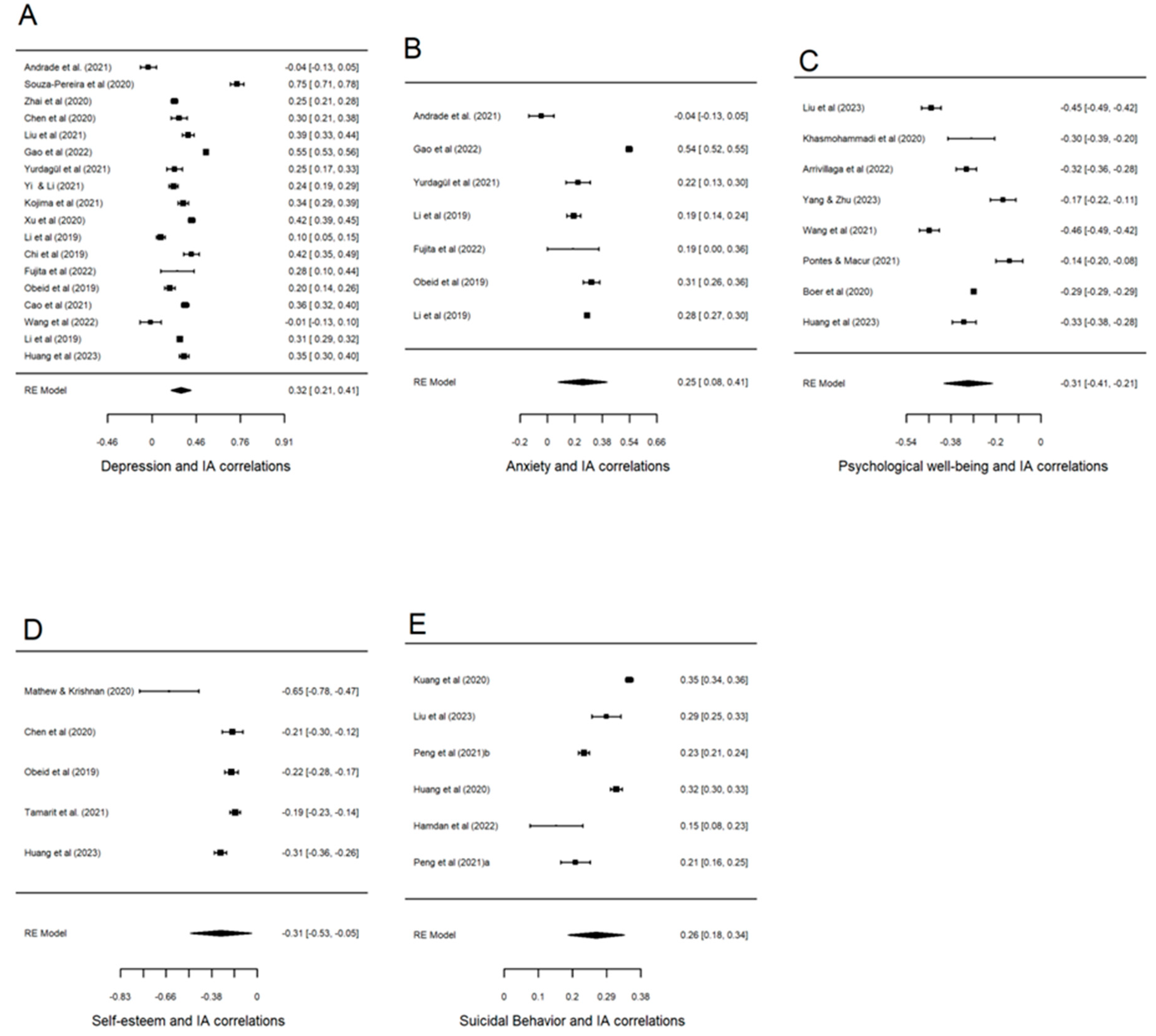

For each meta-analysis, with more than 3 articles, a forest plot was constructed displaying the individual correlations, and the mean effect size with a 95% confidence interval computed by means of the method proposed by Hartung (1999).

The Cochran’s heterogeneity Q statistic and the I² index were calculated to assess the heterogeneity among the effect sizes. The degree of heterogeneity was estimated using the I² index (values of 0%, 25%, 50% and 75% representing no, low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively) (Huedo-Medina et al., 2006).

Publication bias was assessed using both a funnel plot with Duval and Tweedie´s trim-and-fill method for imputing missing data and the Egger’s test (Duval & Tweedie, 2000; Egger et al., 1997). A statistically significant result for the Egger test (p < .10) was evidence of publication bias. Using p < .10 instead of the usual p < .05 because of the lower statistical power of Egger test with such a small number of studies.

Finally, if heterogeneity was found and the number of studies was at least 10, analyses of potential moderator variables were performed (Aguinis et al., 2011). Weighted ANOVAs and meta-regressions for categorical and continuous moderators were applied, respectively, by assuming mixed-effects models. An improved F statistic developed by Knapp and Hartung (Knapp & Hartung, 2003; Rubio-Aparicio et al., 2020) was applied for testing the statistical significance of each moderator. In addition, an estimate of the proportion of variance accounted for by the moderator variable, R2, was calculated (López-López et al., 2014).

All statistical analyses were conducted with the metafor program in R (Viechtbauer, 2010).

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Methodological Quality

To evaluate the quality of the articles selected in this meta-analysis, the tool “JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist” was used, more specifically the one that evaluates cross-sectional studies, developed by the JBI organization and its collaborators and approved by the JBI Scientific Committee after an extensive peer review (Moola et al., 2020).

According to the organization (Moola et al., 2020), the objective of this assessment is to evaluate the methodological quality of a study and determine to what extent it has considered the possibility of bias in its design, execution and analysis.

In addition, these authors stress the importance that during the conduct of a systematic review or meta-analysis, all articles selected for inclusion must undergo rigorous assessment by two critical appraisers.

In this study, this tool was used to assess the quality of the included studies, see

Table S4 (in the Supplementary Material) Specifically, this tool includes 8 items, which reflect five areas of study quality (sampling methods (inclusion criteria and sample description), validity and reliability, measurement tool, identification and strategies to address confounding factors, and appropriate use of statistical analysis). Each of the eight items was scored as "Yes", "No", "Unclear" and "Not applicable", assigning a score of "1" or "0", with 1 being "Yes" and 0 being the other options. Therefore, the total scores range from 0 to 8.

The quality rating score was obtained by adding up the scores for each of the items on the scale. For this purpose, a total score was derived whose values could be between 0 and 8 and the score was also obtained as a percentage (by dividing the total score by the total number of items multiplied by 100).

The quality assessment was carried out independently by two authors and discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two assessors.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

The search strategy initially identified 830 potential articles for inclusion in this article. After the screening process, a total of 33 studies met the eligibility and methodological quality criteria and were selected for this meta-analysis (

Figure 1). A summary of the main data and results of the selected articles is shown in

Table 2 (

Appendix A).

Of the 33 studies finally selected, published between 2019 and 2023, a total sample of 303,823 individuals is obtained. In this regard, it should be noted that the smallest sample is 60 and the largest is 154981. In terms of gender, of the total sample, 50.56% are men and 49.44% are women. It should be noted that only one study did not include women among its participants, only men were included in its sample. The mean age of the total sample is 14.57 years; only two articles do not provide a mean age or standard deviation, but give an age range, while the remaining articles report the mean age of their participants.

In terms of cultural differences, 66.67% of the selected studies were conducted in East Asia (China, Japan, Taiwan and Macau), with the East Asian population accounting for 46.2% of the total sample. Similarly, 9.09% of the studies were conducted in West Asia (Lebanon, Israel and Turkey) and another 9.09% in Europe (Spain and Slovakia), accounting for 0.74% and 1.55% of the total sample respectively. There were 6.06% of the research was carried out in South Asia (India and Malaysia) and another 6.06% in South America (Brazil), accounting for 0.14% and 0.37% of the total sample respectively. Finally, there was one study, representing 3.03% of the total number of articles, where the nationality was shared with Europe, North America and West Asia, accounting for 51.01% of participants in the total sample. The presence of different countries allows us to see if there are differences between cultures.

The most frequent study design was cross-sectional (n=28, 84.84%), the rest being longitudinal (n=5, 15.15%).

Most of the studies did not report the time period assessed, while 8 studies conducted their study over a period of 4-9 months, in one study the time period was 1 year, in 2 studies the time period was 2 years and in one study the time period was 4 years.

In terms of study outcomes, 18 studies assessed depression (41,693 subjects), 7 studies assessed anxiety (27,122 subjects), 2 studies assessed stress (8,456 subjects), 6 studies assessed suicidal behaviour (82,872 subjects), 8 studies assessed psychological well-being (164,918 subjects), 5 studies assessed self-esteem (4,742 subjects), 2 studies assessed externalizing problems (3172 subjects), 3 studies assessed aggressiveness (29,587 subjects) and 2 studies assessed impulsiveness (13,610 subjects).

The instruments used for each variable can be consulted in

Table 3 (

Appendix B), highlighting that the most widely used to measure Internet addiction was the IAT. As for the psychological variables, for depression the CES-D, for anxiety the GAD-7 and the DASS-21, the latter was also the most used for stress and psychological well-being, for suicidal behaviour the Form of questions proposed by the authors, for self-esteem the RSES, for aggressiveness the AQ was the most used, for impulsiveness the only instrument found was the BISS-11, and for externalizing problems the YSR and the SDQ.

3.3. Mean Correlations and Heterogeneity

Table 4 shows the results of the nine meta-analyses performed for each outcome. All of them were statistically significate with exception of externalizing problems (general measures) (r+ = 0.292; 95% CI = -0.487, 0.813), impulsiveness (r+ = 0.303; 95% CI = -0.605, 0.868) and stress (r+ = 0.253; 95% CI = -0.996, 0.999), probably due to the low statistical power with such a small number of studies (k = 2).

The highest mean correlation was found for the relationship between internet addiction and aggressiveness (r+ = 0.391; 95% CI = 0.244, 0.521), followed by the mean correlation for internet addiction and depression (r+ = 0.318; 95% CI = 0.214, 0.415). Similar mean correlations were found for psychological well-being (r+ = -0.312; 95% CI = -0.407, -0.212) and self-esteem (r+ = -0.306; 95% CI = -0.527, -0.047). Last, the mean correlations that estimated the relationship between internet addiction and anxiety and between internet addiction and suicidal behaviour were the smaller ones (r+ = 0.252; 95% CI = 0.078, 0.412 and r+ = 0.264; 95% CI = 0.185, 0.339, respectively).

In all cases the mean correlations reflected moderate magnitudes. Furthermore, the sign of the correlations indicated the sense of the relationship between internet addiction and each outcome.

It is important to consider the scarce number of studies that assessed the relationship between internet addiction and externalizing problems, aggressiveness, impulsiveness, and stress. For this reason, these results can be interpreted cautiously.

Finally, as can be seen in

Table 4, the analyses found considerable heterogeneity among individual correlations in all meta-analyses (I2 > 90% and p < .001).

Figure 2 presents the forest plots, of studies with more than 3 articles, constructed to show the results about the relationship between the internet addiction and the depression, anxiety, psychological well-being, and self-esteem and suicidal behavior (A, B, C, D and E, respectively). That great variability is also reflected in this figure.

3.4. Publication Bias

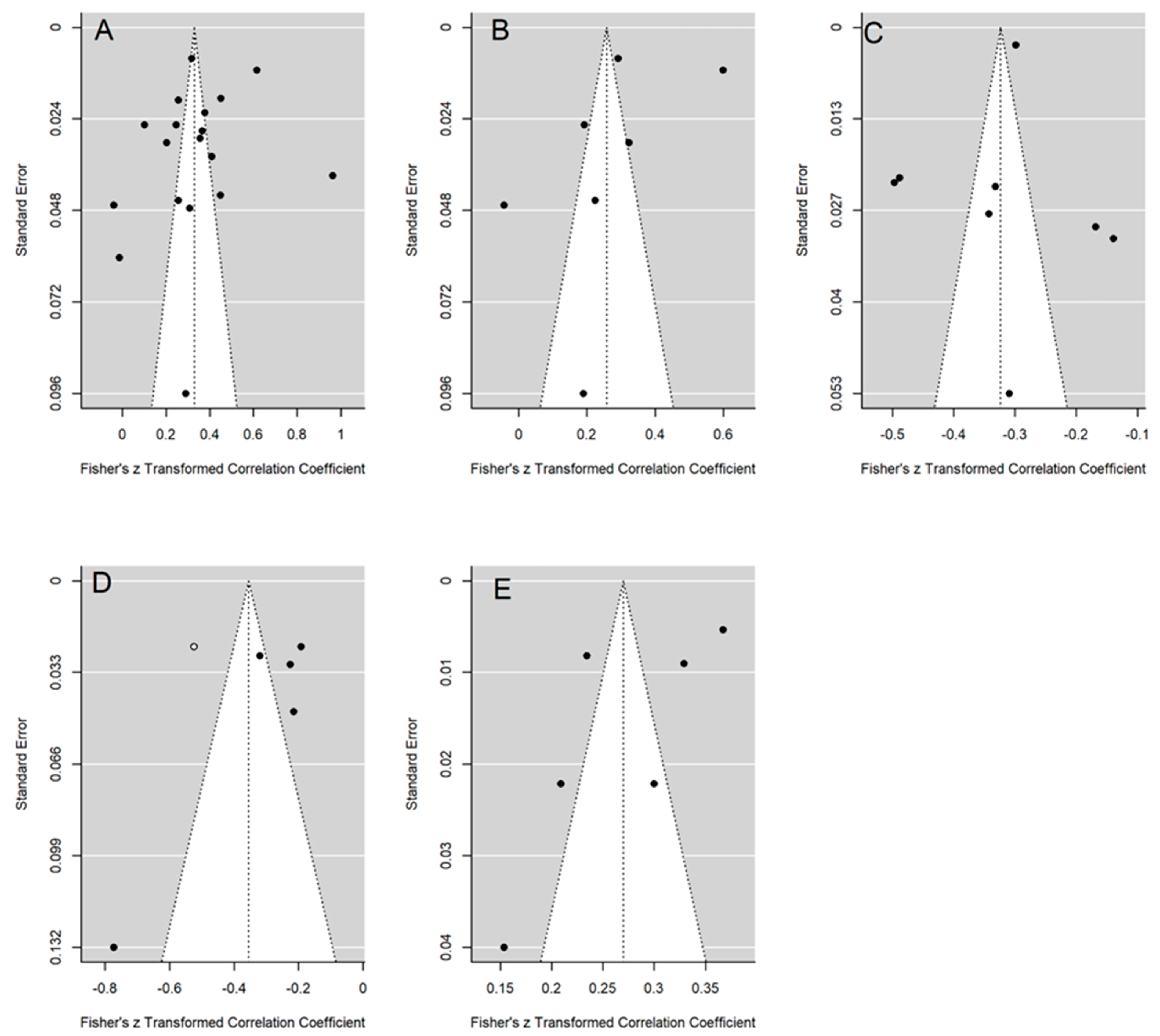

Publication bias was analysed for depression, anxiety, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and suicidal behaviour outcomes by constructed a funnel plot and assessing its asymmetry with the trim-and-fill method and the Egger test.

Non-significant results for the interception were obtained from the Egger test for depression (t(16) = -0.935; p = .364), anxiety (t(5) = -1.285; p = .255), psychological wellbeing (t(6) = 0.474; p = .652), and suicidal behaviour (t(4) = -2.271 ; p = .105). In addition, applying the trim-and-fill method no correlation coefficients had to be imputed to achieve the symmetry of the funnel plots for depression, anxiety, psychological well-being, and suicidal behaviour (see

Figure 3A, 3B, 3C , 3D and 3E, respectively). These results led us to discard publication bias as a threat against these meta-analytic results.

For self-esteem outcome the Egger test yielded a significant result (p < .10) for the interception (t(3) = -3.067; p = .053) and by applying the trim-and-fill method an additional correlation coefficient was imputed to the set original correlations to achieve symmetry in the funnel plot (see

Figure 3D). The adjusted mean correlation, once corrected by publication bias was radj = -0.355 (95% CI = -0.513, -0.196; k = 6). Compared with the original mean correlation obtained with the five studies (r+ = -0.306), the adjusted mean correlation barely changed.

3.5. Analyses of Moderators

The existence of heterogeneity found among the correlations led to carry out the analyses of moderator variables for those outcomes with at least 10 studies, i.e. depression.

Table 5 presents the results of the simple meta-regressions performed on continuous moderators. None of the analysed moderators reached a statistically significant association with the correlations between internet addiction and depression.

The continent where the study took place and design of the study were also analyses, as categorical moderators, by means of weighted ANOVAs models.

Table 6 presents those results. Once again, none of them reached a statistically significant association.

4. Discussion

Our objective was to determine the impact of Internet use on adolescents' mental health. To this end, a meta-analytic study was conducted on the relationship between the most prevalent mental health variables and Internet addiction, quantifying the strength of this relationship and possible moderating variables, such as age, sex, quality of the selected articles, nationality of the studies and type of design used. The associations between problematic Internet use and the nine mental health variables analysed in the selected studies were estimated: depression, anxiety, stress, psychological well-being, self-esteem, suicidal behaviour, externalizing problems, aggressiveness, impulsiveness.

The results indicate that Internet addiction is related to the variables depression, anxiety, mental well-being, self-esteem, aggressiveness and suicidal behavior. The strength of these relationships reflects moderate magnitudes, with the relationship between Internet addiction and aggressiveness being the highest, followed by the relationship with depression. These are followed by the relationship between Internet addiction and psychological well-being and self-esteem, respectively. The lowest relationship is found between Internet addiction and the variables anxiety and suicidal behaviour. However, no significant relationships were found between Internet addiction and variables of stress, impulsiveness and externalizing problems (general measures), probably due to the small number of articles that analysed the relationship with these variables.

Regarding the influence of moderating variables (mean age of the sample, standard deviation of age, percentage of women, study quality score (JBI), nationality and study design) only their possible effect on the relationship between depression and Internet addiction could be estimated. The results showed that these moderating variables had no effect on this relationship, indicating that this connection between Internet addiction and depression was robust with regard these variables.

Aggressiveness has been identified as one of the most prevalent externalizing behaviours in adolescence in the study of psychopathology (Keltikangas-Järvinen, 2005). In our meta-analytic study, it is one of the behaviours most strongly related to internet addiction. Obeid et al. (2019) and Peng et al. (2022) find that adolescents with higher scores on Internet addiction showed higher levels of aggressiveness. Peng et al. (2022), in addition to supporting the idea that Internet addiction was a positive predictor of aggression, show that aggression was at the same time a predictor of Internet addiction, both being a risk factor for the other. On the other hand, Huang et al. (2023), conduct a study where they observe the effect that aggressive personality has between problematic Internet use and suicidal ideation in adolescents, finding that participants who have more problems with the Internet show greater suicidal ideation, with this association being stronger in groups with aggressiveness.

These results are consistent with previous research showing that both frequency of use and severity of Internet addiction are related to higher aggression scores (Kim et al., 2015; Koo & Kwon, 2014).

In this sense, Internet use seems to facilitate the expression of latent aggressive impulses, such as repressed anger, aggression or hostility, which are not acceptable in society, but can be released in the digital environment; the relief of these emotional states generates a rewarding feeling that seems to lead to addiction (Koo & Kwon, 2014; Fumero et al., 2018).

Several studies highlight the association between depression and Internet addiction (Obeid et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Chi et al., 2019, Gao et al., 2020). Only one of the studies included in this meta-analysis, Andrade et al. (2021), found no significant associations between problematic Internet use and emotional variables, including depression. The authors claim that this lack of association could be explained by the small sample size.

Among those supporting this association is the study by Fujita et al. (2022), who reveal how adolescents with PIU show greater depressive symptoms compared to patients without PIU. The study by Wang et al. (2022) with adolescents with a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder concluded that adolescents with more severe depressive symptoms are more likely to have symptoms of Internet addiction. Souza-Pereira et al. (2020) show the association of problematic smartphone use (PSU) and depressive symptoms, the results suggest that adolescents with PSU are more likely to experience mood disturbances and depressive symptoms than adolescents without PSU. Yurdagül et al. (2021) find a direct relationship between problematic social media use, more specifically Instagram, with depression and other psychopathological symptoms.

Regarding the direction of the relationship between depression and Internet addiction among the selected studies, the longitudinal studies by Yi & Li (2021) and Li, G. et al. (2019) or the cross-sectional study by Gao et al. (2022) stated that it is depressive symptoms that predict the onset of Internet addiction, while others (Huang et al., 2023; Kojima et al., 2021) found that problematic Internet use precedes depressive symptoms.

The mediating role of depression in the relationship between IA/PIU with other variables such as perception of school climate (Zhai et al., 2020), bullying victimisation (Liu et al., 2021) or peer victimisation (Li, X. et al., 2019) has also been analysed. Depression proved to be a mediating variable in these relationships, determining that the relationship between depression and IA or PIU was significant and positive. Similarly, the longitudinal study by Cao et al. (2021), examines the mediating effect of IA concerning the relationship between depression and bullying victimization, identifying IA as a mediating variable and establishing a significant positive relationship between depression and IA.

Previous studies confirm this relationship, indicating that higher levels of Internet addiction are related to higher levels of depression (Cai et al., 2023; Colder-Carras et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2016; Akin & Iskender, 2011; Ha et al., 2007). One of the most common explanatory hypotheses for this relationship posits that spending more time on the Internet reduces face-to-face interactions, which deteriorates real-life interpersonal relationships, leading to a feeling of alienation that negatively impacts the individual's mental health (Baloğlu et al., 2018). Others also suggest that people with depressive symptoms use the Internet to reduce negative feelings (Kim et al., 2015). At a general level, there is no consensus on the direction of this relationship. Bickhan et al. (2015) claim that it is Internet addiction that affects depressive symptoms, proving that levels of depression can be reduced if Internet use is controlled through household rules; others, such as Chang et al. (2014), show that depression predicts and supports the persistence of young people's Internet addiction.

Regarding psychological well-being, some studies support its association with Internet addiction (Khasmohammadi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Pontes & Macur, 2021), noting that higher levels of Internet addiction are associated with poorer levels of psychological well-being. Wang et al. (2021) report a positive association between PIU and behavioural and emotional problems, while Pontes & Macur's study (2021) finds that PIU is associated with lower levels of subjective well-being.

The longitudinal study by Huang et al. (2023) identified three distinct trajectories of IA (low increase, moderate decrease and high decrease) among adolescents over three years. Their results indicated that being in the high or moderate risk IA groups was associated with lower psychological well-being.

Arrivillaga et al. (2022) find a direct association between problematic smartphone use (PSU) and psychological distress, Boer et al. (2020) analyse problematic social network use (PSMU) and psychological well-being of adolescents with data from 29 countries and find that PSMU is indicative of low well-being in all domains assessed and in all countries.

Psychological well-being was also analysed as a mediating variable in the relationship between PIU and other behavioural or mental health variables. Liu et al. (2023) focus on the mediating role of negative affectivity in the relationship between PIU and suicidality and self-injurious behaviours; Yang & Zhu (2023) analyse the mediating role of mental health in the relationship between PIU and externalizing behavioural problems among adolescents. In both cases, psychological well-being was found to be a mediating variable between these relationships, as well as indicating a positive association between these variables, determining that the higher the PIU, the worse the psychological well-being.

Thus, according to the authors reviewed in this meta-analytic study, it is generally observed that higher levels of addiction are associated with poorer psychological well-being. Previous studies, (Lin et al., 2018; Mei et al., 2016) agree with this result. According to Cardak (2013), an explanatory hypothesis is that the variable psychological well-being is related to a mental state characterised by feelings such as satisfaction, pleasure, self-perception of well-being, and positive emotions, which contrasts with aspects usually linked to Internet addiction, such as loneliness, poorer social adaptation, poorer emotional skills, and neuroticism, all of which hinder the individual's adaptation and coping ability.

As with psychological well-being, self-esteem was also inversely related to Internet addiction. Studies by Obeid et al. (2019) and Chen et al. (2020) support the association between self-esteem and Internet addiction, indicating that higher levels of Internet addiction resulted in lower levels of self-esteem. Also, as with psychological well-being in the longitudinal study by Huang et al. (2023), the results indicate that being in the high- or moderate-risk IA groups was associated with lower self-esteem. In the research carried out by Mathew & Krishnan (2020), they observe that higher levels of PIU resulted in lower levels of self-esteem.

Finally, the study by Tamarit et al. (2021) focuses on the mediating role of body self-esteem in the relationship between IA and sexual victimization in adolescents. It was found that self-esteem did affect this relationship, as well as being associated with IA, determining that the higher the IA, the lower the self-esteem.

In support of these results, previous studies (Cardak, 2023; Bahrainian, 2014) agree with these findings and found similar results. Griffith's (2000) explains that individuals who evaluate themselves negatively may perceive the Internet as a mean to compensate for some self-perceived shortcomings or negative aspects. Through anonymity or the absence of face-to-face contact, the Internet helps the adoption of another personality or social identity, thus satisfying these shortcomings and generating a dependent relationship with this medium.

In relation to anxiety and its association with IA, several studies support the relationship that higher levels of anxiety lead to higher levels of Internet addiction (Obeid et al., 2019; Gao et al, 2022; Li, G. et al., 2019). As well as Fujita et al. (2022) who in their study reveal how adolescents with PIU showed higher anxious symptoms compared to patients without PIU. However, Andrade et al. (2021), as with depression, do not find significant associations between PIU and anxiety, due to the small sample used.

Yurdagül et al. (2021) find that problematic social media use (PSMU), more specifically Instagram, is directly positively associated with anxiety for the male sample, while for females this association was indirect.

The study by Li, X. et al. (2019) focused on the mediating role of anxiety on the basis of the relationship between IA and peer victimization, determining how anxiety does affect this relationship, as well as observing that higher levels of IA lead to higher levels of anxiety.

Previous studies confirm these results (Akin & Iskender, 2011; Woods & Scott; 2016). This fact could be explained, on the one hand, by the fact that people with anxiety have a preference for online social interactions as these interactions have benefits for these people as it helps to maintain control over some variables such as the speed of interaction, the elaboration of sentences or the way in which they appear in front of the other person, factors that help to increase feelings of security and confidence (Akin & Iskender, 2011; Caplan, 2006). On the other hand, when internet access is restricted, when messages cannot be responded to immediately or when the FOMO phenomenon occurs, these have also been found to be associated with increased symptoms of anxiety (Woods & Scott; 2016).

Regarding the relationship between IA and suicidal and self-harming behaviours, some studies found that increases in IA scores led to increases in suicidal behaviours, including suicidal ideation (SI), suicidal plans (SP) and suicidal attempts (SA) (Peng et al., 2021a; Peng et al., 2021b).

In relation to suicidal ideation, other studies (Kuang et al, 2020; Huang et al., 2020) agree that the higher the IA/PIU, the higher the suicidal thoughts. Furthermore, the study by Liu et al. (2023) found a direct effect of PIU on suicidality and self-injurious behaviours (SSIB) and the study by Hamdan et al. (2022) found that an increase in IA/PIU was related to suicidal and self-injurious behaviours. Suicidal behaviours, especially in young people, are one of the problems with the greatest impact on global public health (Unicef Data, 2024). It is therefore important to look for variables that may be related or may be a risk factor for these behaviours to take place.

Previous studies agree with the results described above (Serrano et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2018; Marchant et al., 2017; Kaess et al., 2014). However, authors such as Daine et al. (2013) claim that Internet use can have protective effects as it can serve as a source of emotional support and improve coping strategies. Nevertheless, when talking about problematic Internet use, there seem to be more negative effects in relation to an increased risk of self-harm or suicidal ideation, as inappropriate Internet use facilitates exposure to suicidal behaviour and is associated with more dangerous methods of self-harm (Serrano et al., 2017).

Finally, the articles selected in relation to the variables stress, impulsiveness and externalizing problems found the following:

Finally, regarding the variables of stress, impulsivity, and externalizing problems (general measures), our study does not yield significant results due to due to the small number of articles found for this meta-analysis in relation to these variables. We will now briefly comment on the most significant results of the studies analysed.

In relation to stress and its association with IA, Gao et al. (2022) support the relationship that higher levels of stress lead to higher levels of Internet addiction. However, in the study by Andrade et al. (2021), as with depression and anxiety, no significant associations are found between PIU and stress, alleging that this could be explained by the small sample used.

In relation to impulsivity, Obeid et al. (2019) find more internet addiction in students with higher levels of impulsivity, and Huang et al. (2023) report a stronger association between PIU and suicidal ideation in students with impulsive personality.

For externalizing problems (in relation to general measures), Yang & Zhu (2023) found that PIU plays a negative role in promoting externalizing problem behaviours, as a positive association is found between these two variables. As in the study by Wang et al. (2021) they point out that the higher the PIU levels, the higher the presence of behavioural problems, especially in relation to hyperactivity and conduct problems.

4.1. Limitations

This paper included studies from around the world and illustrated the relationship between various mental health variables and AI, including symptomatological variables characteristic of both internalizing and externalizing disorders, and positive variables such as well-being and self-esteem. We included only validated measures of IA for each of the nine mental health variables, and studies with a quality of between 5 and 8 points on the JBI scale, eliminating those below 5 points. However, our study also has limitations. Firstly, the number of articles found for each of the mental health variables, with the exception of studies on depression, was below 10 articles. In this sense, this small number of articles for most of the variables only allowed us to take into account moderating variables in the relationship between depression and Internet addiction.

Secondly, some of the variables found after data extraction had to be extracted from the analyses due to the scarcity of studies found (n=1) (body image, internalizing problems, delinquent behaviour) and the impossibility of extracting the effect size from the original item (tobacco use and alcohol use).

Third, most of the studies included in this meta-analysis had a cross-sectional design, limiting the possibility of making inferences about the causal relationship between Internet addiction and adolescent mental health. Fourthly, no publication biases were found for any variable except self-esteem, which forces us to interpret the data with caution with respect to this variable.

5. Conclusions

Due to the increasing use of the Internet, several studies have focused on the relationship between Internet addiction and mental health-related problems. The present meta-analysis aims to synthesise and quantify the evidence found in recent years on the relationship of IA with mental health problems, both internalizing and externalizing, in the adolescent population.

The selected studies found evidence of a positive association between IA with variables such as depression, anxiety, stress, suicidal behaviour, externalizing problems, aggressiveness and impulsiveness, and a negative association with self-esteem and psychological well-being. Only one study (Andrade et al., 2021) was unable to determine the existence of a relationship between IA and depression, anxiety and stress.

The results of our meta-analysis confirm all relationships, except for the variables of stress, impulsivity and externalizing problems (general measures) where no significant associations with AI were found. The strength of the relationships found is of moderate magnitude, the strongest with aggression and depression and the weakest with anxiety and suicidal behaviour.

These results help to expand our knowledge about Internet addiction and its relationship with mental health variables in young people, emphasising not only internalizing variables, but also externalizing variables, such as aggression, for which we have less evidence. The study of the consequences of problematic internet use on mental health is a fundamental requirement for making progress in the design and implementation of more effective and efficient interventions in a population as vulnerable as adolescents.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary 1. Table S1. PRISMA 2020 Checklist; Supplementary 2. Table S2. PRISMA 2020 Checklist for structured summaries; Supplementary 3. Table S3. Coding of variables for analysis in SPSS; Supplementary 4. Table S4. Articles quality assessment (n=33) by JBI scale

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.L.G., R.M.P.H. and E.S.M.; methodology, M.R.A. and E.S.M.; formal analysis, M.R.A. and E.S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.M.; writing—review and editing, R.M.L.G., R.M.P.H. and E.S.M.; visualization, M.R.A.; supervision, R.M.L.G., R.M.P.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by European School of Alicante (Project 12274: Psy-cho.pedagogical Assessments). This study has been carried out in the research group “Health from a Nursing and Psychological Perspective” (E063-02). University of Murcia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data on guidelines for the publication of systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses and structured abstracts, coding of selected variables for analysis in SPSS and quality checklists of studies are available in the supplementary material of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Appendix A Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author |

Year |

Nationality |

Study design |

Total sample size |

Sex (F = Female

M = Male) |

Mean Age (SD age) |

Period of study |

Study outcome |

Assessment tools |

Main results between Internet Adiction/Problematic Internet Use and Study Outcome |

| Andrade et al. |

2021 |

South America |

Cross-sectional |

466 |

F= 53%

M= 47% |

12.8 (1.9) |

Not Reported. |

Depression, Anxiety, Stress |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21). |

The analysis of variance did not detect any differences between the no PIU and PIU groups regarding the

DASS-21 subscales (depression, anxiety and stress) (p>0.05)

|

| Arrivillaga et al. |

2022 |

Europe |

Cross-sectional |

1882 |

F= 54%

M= 46% |

14.71 (1.60) |

Not Reported. |

Psychological well-being |

Spanish short version of the

Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS-SV), Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

|

PSU was directly associated with psychological distress (r = .32, p < 0.01) |

| Boer et al. |

2020 |

Europe, North América, West Asia |

Cross sectional |

154981 |

F= 51%

M= 49% |

13.54 (1.64) |

2017-2018 |

Psychological well-being |

9-item Social Media Disorder Scale, "Mental" ranking de Cantril’s ladder, HBSC Symptom Checklist.

|

Problematic Social Media Use was correlated with psychological complaints (r= .290, p< 0.001) |

| Cao et al. |

2021 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

2022 |

F= 50.1%

M= 49.9% |

13.04 (1.0) |

Not Reported. |

Depression |

Young’s Internet Addiction Scale (IAT), Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Symptom Scale (CES-D)

|

Correlation analysis indicated that Internet addiction and depression

have significant, positive correlations with each other (r= .36, p< .01) |

| Chen et al. |

2020 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

451 |

F= 49.2%

M= 50.8% |

11.35 (0.56) |

2020 |

Depression, Self-Esteem |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Symptom Scale (CES-D), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES).

|

IA was positively correlated with depression (r= 0.2986) and self-esteem (r= 0.2127) |

| Chi et al. |

2019 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

522 |

F=42.92%

M=57.08% |

12.33 (0.56) |

Not Reported. |

Depression |

Young and De Abreu’s ten-item Internet addiction test, Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Symptom Scale (CES-D).

|

Internet addiction was positively correlated with depression (r= .42, p< .01) |

| Fujita et al. |

2022 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

112 |

F= 42.8%

M= 57.2% |

13.65 (1.9) |

April 2016-March 2018 |

Depression, Anxiety. |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), 9 items-Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7).

|

IA was positively correlated with depression (r=0.2808) and anxiety (r=0.1868) scores

|

| Gao et al. |

2022 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

7990 |

F= 49.62%

M= 50,38% |

|

Not Reported. |

Depression, Anxiety, Estrés. |

Revised Chen Internet Addiction Scale

(CIAS-R), Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

|

IA was positively correlated with depression (r=0. 5472), anxiety (r=0.5357) and stress (r=-0.4810)

|

| Hamdan et al. |

2022 |

West Asia |

Cross- sectional |

642 |

F= 53.6%

M= 46.4% |

14.95 (1.53) |

Not Reported. |

Suicide |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory-Youth Version (DSHI-Y)

|

IA was positively correlated with suicidal ideation (r= 0.1521)

|

| Huang et al. |

2023 |

East Asia |

Longitudinal |

1365 |

F= 46.8%

M= 53,2% |

14.68 (1.56) |

2015 - 2017 |

Depression, Psychological well-being, Self-Esteem. |

10-item IA Diagnostic Questionnaire, Children’s Depression

Inventory (CDI-S), 9-item Index of Well-Being, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)

|

IA was positively correlated with depression (r=0. 3500), psychological well-being (r=0.33) and inversely correlated with (r=-0.3100) |

| Huang et al. |

2020 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

12507 |

F= 51.49%

M= 48.41% |

16.6 (0.8) |

Not Reported. |

Suicidal ideation, Aggressiveness, Impulsiveness |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Scales produced

by the Beijing Center for Psychological Crisis Research and Intervention, Chinese version of the Buss & Perry aggression questionnaire (AQ-CV), Barratt impulsiveness scale-Chinese version (BIS-CV)

|

IA was positively correlated with suicidal Ideation (r=0.3176), aggressiveness (r=0.4426) and impulsiveness (r=0.3709)

|

| Khasmohammadi et al. |

2020 |

South Asia |

Cross-sectional |

357 |

F= 49.6%

M= 50.4% |

16.14 (1.42) |

12 meses (Not Reported) |

Psychological well-being |

Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS), Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS)

|

Psychological well-being was

negatively and significantly related to compulsive Internet use (r= -.300, p<.01). |

| Kojima et al. |

2021 |

East Asia |

Longitudianl |

1192 |

F= 50.83%

M= 49.17% |

|

2014-2018 |

Depression |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Birleson

Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS). |

The correlations between all PIU waves (t1, t2, t3) and depression waves (t1, t2, t3) correlate positively with each other (p<0.05). Correlation between PIU-t1 and depression-t1 was (r= .34, p<0.05)

|

| Kuang et al. |

2020 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

36266 |

F= 46%

M= 54% |

18.6 (1.9) |

Not Reported. |

Suicidal Ideation, |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Scale of Suicidal Ideation developed.

|

IA was positively correlated with suicidal ideation (r=0.3513)

|

| Li, G. et al. |

2019 |

East Asia |

Longitudinal |

1545 |

F= 55%

M= 45% |

14.88 (1.81) |

6 meses (Not Reported.date) |

Depression, Anxiety. |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Zung’s self-rating depression scale (SDS), Zung's

self-rating anxiety scale (SAS). |

Correlations between all IA waves (t1, t2, t3) correlated positively with Depression (t1, t2, t3) and Anxiety (t1, t2, t3) waves (p<0.05) except the correlation between AI-t2 with Depression-t1 and the correlation between AI-t3 with Depression-t3. Correlation between IA-t1 and Depression-t1 was (r= 0.10, p<0.001) and AI-t1 and Anxiety-t1 was (r= .19, p<0.001)

|

| Li, X. et al. |

2019 |

East Asia |

Cross sectional |

15415 |

F= 50.26%

M= 49.74% |

14.6 (1.7) |

Not Reported. |

Depression, Anxiety. |

Young diagnostic questionnaire for internet addiction (YDQ), Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies

Depression 9-item scale (CES-D9), Generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7)

|

Both depressive (r= .307, p< .01) and anxiety symptoms (r= .283, p<.01) were positively

associated with Internet addiction |

| Liu et al. |

2021 |

East Asia |

Longitudinal |

879 |

F= 41.9%

M= 58.1% |

13.51 (1.17) |

8 meses (Not Reported.) |

Depression |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Symptom Scale (CES-D).

|

There is a positive correlation between PIU and depressive symptoms (r= .388, p< .001) |

| Liu et al. |

2023 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

2095 |

F= 49%

M= 51% |

14.66 (1.87) |

Not Reported. |

Suicide, Psychological well-being |

Revised Chen Internet Addiction Scale

(CIAS-R), Health-

Risk Behavior Inventory for Chinese Adolescents (HBICA), Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

|

PIU was positively correlated with Suicidality and self-injurious (r=0.291 p< 0.001) and negative affectivity (r= .4553, p < 0.001).

|

| Mathew & Krishnan |

2020 |

South Asia |

Cross- sectional |

60 |

F= 0%

M= 100% |

15 (1.0) |

Not Reported. |

Self-esteem |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES)

|

Problematic Internet use was significantly negatively correlated with self-esteem (r=-0.649, p<0.001) |

| Obeid et al. |

2019 |

West Asia |

Cross-sectional |

1103 |

F=58.4%

M=41.6% |

15.50 (1.33) |

2017-2018 |

Depression, Anxiety, Self-Esteem, Aggressiveness, Impulsiveness |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Multiscore Depression Inventory for Children (MDIC), Buss-Perry Scale (AQ), BARRAT Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11). |

Higher IA was significantly and positively correlated with more impulsivity (r = .226, p< .001), more physical aggression (r = .328, p< .001), more anxiety (r = .312, p< .001), more sad mood (r = .199, p< .001). However, less IA was correlated with higher self-esteem (r = −.222, p< .001)

|

| Peng et al (a). |

2021 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

16130 |

F= 48.1%

M= 51.9% |

15.22 (1.79) |

February to October in 2015 |

Suicidal behaviour |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Questionaire. |

Internet addiction was positively correlated with suicidal behaviours (r=0.206, p<0.01)

|

| Peng et al (b). |

2021 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

15232 |

F= 48.2%

M= 51,8% |

15.18 (1.71) |

February to October in 2015 |

Suicidal behaviour |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Questionaire.

|

Internet addiction was positively correlated with suicidal behaviours (r=0.23, p<0.01)

|

| Peng et al. |

2022 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

15977 |

F= 48.2%

M= 51.2% |

15.21 (1.74) |

February to October 2015 |

Aggressiveness. |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Buss and Warren's

Aggression Questionnaire (BWAQ).

|

IA was positively correlated with aggressiveness (r=0.39)

|

| Pontes & Macur |

2021 |

Europe |

Cross-sectional |

1066 |

F= 50%

M= 50% |

13.46 (0.58) |

Not Reported. |

Psychological well-being, |

Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire Short-Form

(PIUQ-SF-6)

Questionaire |

PIU was inversely correlated with well-being (r=-0.1387) |

| Souza-Pereira et al. |

2020 |

South America |

Cross-sectional |

667 |

F= 53.8%

M= 46.2% |

15.5 (1.87) |

Not Reported. |

Depression. |

Spanish short version of the

Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS-SV), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

|

Smartphone Use was positively correlated with depression (r=-0.7451)

|

| Tamarit et al. |

2021 |

Europe |

Cross-sectional |

1763 |

F= 51%

M= 49% |

14.56 (1.16) |

Not Reported. |

Self-esteem |

Scale of risk of

addiction to social media and the Internet for adolescents (ERA-RSI), Escala de Autoestima Corporal (EAC)

|

Addiction symptoms are significantly negatively associated with Body satisfaction (r= -0.19, p < 0.01) |

| Wang et al. |

2022 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

278 |

F= 73.4%

M= 26.6% |

15.28 (1.71) |

Not Reported. |

Depression |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Symptom Scale (CES-D).

|

IA was positively correlated with depression (r=-0.0146) |

| Wang et al. |

2021 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

1976 |

F= 49.2%

M= 50,8% |

13.6 (1.5) |

January to April 2019 |

Psychological well-being, Externalizing Problems |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Self-report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

|

Problematic Internet use was significantly correlated with Total difficulties (behavioral and emotional problems) (r=0.46, p<0.05) and conduct problems (r=0.35, p<0.05) |

| Xu et al. |

2020 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

2892 |

F= 46.2%

M= 53,8% |

15.1 (1.7) |

April to July 2017 |

Depression |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Symptom Scale (CES-D)

|

IA was positively correlated with depression (r=0.4216) |

| Yang & Zhu |

2023 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

1196 |

F= 49.4%

M= 50.6% |

14.45 (0.63) |

2021 |

Psychological well-being, Externalizing problems |

10 items Internet Addiction Test (IAT),, 12-item General Health Questionnaire

(GHQ-12), Youth Self-Report (YSR)

|

Problematic Internet use was positively associated with externalizing problem behaviors (r = 0.230 p < 0.01) and

negatively associated with Mental health (r = - 0.167, p < 0.01).

|

| Yi & Li |

2021 |

East Asia |

Longitudinal |

1545 |

F= 55%

M= 45% |

14.88 (1.81) |

6 months (Not Reported date) |

Depression |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Zung’s self-rating depression scale (SDS). |

The correlations between all IA waves (t1, t2, t3) and depression waves (t1, t2, t3) correlate positively with each other (p<0.001). Correlation between AI-t1 and depression-t1 was (r= .24, p<0.001)

|

| Yurdagül et al. |

2021 |

West Asia |

Cross-sectional |

491 |

F= 58.65%

M= 41.35% |

15.92 (1.07) |

Not Reported. |

Depression, Anxiety |

Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS), Short Depression-Happiness Scale (SDHS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Short Form (STAI-6).

|

Problematic Instagram use (PIU) was

associated with depression (r = .25, p< .001), general anxiety (r = .22, p< .001). |

| Zhai et al. |

2020 |

East Asia |

Cross-sectional |

2758 |

F= 54%

M= 46% |

13.53 (1.06) |

Not Reported. |

Depression |

Internet

Addiction Test (IAT), Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI-S). |

There is a positive correlation between T2-PIU and T1-Depression (r= .25, p< .001). |

Appendix B. Coding of Variables for Analysis in SPSS

Table 3.

Summary of instruments used in the selected articles.

Table 3.

Summary of instruments used in the selected articles.

| Assessment tools |

Study outcome |

Author |

| Internet Addiction Test (IAT) |

Internet Addiction (IA)/Problematic Internet Use (PIU) |

Wang et al. (2022)

Yi & Li (2021)

Kojima et al. (2021)

Chen et al. (2020)

Zhai et al. (2020)

Liu et al. (2021)

Obeid et al. (2019)

Li, G. et al. (2019)

Peng et al. (2022)

Hamdan et al. (2022)

Fujita et al. (2022)

|

Peng et al. (2021a)

Peng et al. (2021b)

Wang et al. (2021)

Andrade et al. (2021)

Xu et al (2020)

Kuang et al. (2020)

Huang et al. (2020)

Mathew & Krishnan (2020)

Cao et al. (2021)

Yang & Zhu (2023) |

Young and De Abreu’s ten-item Internet addiction test´

|

IA/PIU |

Chi et al. (2019) |

Young diagnostic questionnaire for internet addiction (YDQ)

|

IA/PIU |

Li, X. et al. (2019) |

Spanish short version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS-SV)

|

IA/PIU |

Arrivillaga et al. (2022)

Souza-Pereira et al. (2020) |

9-item Social Media Disorder Scale

|

IA/PIU |

Boer et al. (2020) |

Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS)

|

IA/PIU |

Khasmohammadi et al. (2020) |

Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS)

|

IA/PIU |

Yurdagül et al. (2021) |

Revised Chen Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS-R)

|

IA/PIU |

Liu et al. (2023)

Gao et al. (2022) |

10-item IA Diagnostic Questionnaire

|

IA/PIU |

Huang et al. (2023) |

Scale of risk of

addiction to social media and the Internet for adolescents (ERA-RSI)

|

IA/PIU |

Tamarit et al. (2021) |

| Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire Short-Form (PIUQ-SF-6) |

IA/PIU |

Pontes & Macur (2021) |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Symptom Scale (CES-D) |

Depression |

Wang et al. (2022)

Chen et al. (2020)

Liu et al. (2021)

Cao et al. (2021)

Chi et al. (2019)

Li, X. et al. (2019)

Xu et al. (2020)

|

| Zung’s self-rating depression scale (SDS). |

Depression |

Yi & Li (2021)

Li, G. et al. (2019) |

Birleson Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS)

|

Depression |

Kojima et al. (2021) |

Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI-S)

|

Depression |

Zhai et al. (2020)

Huang et al. (2023) |

| Multiscore Depression Inventory for Children (MDIC) |

Depression |

Obeid et al. (2019) |

| Anxiety |

Self-Esteem

|

| Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) |

Depression |

Gao et al. (2022)

Andrade et al. (2021)

|

| Anxiety |

| Stress |

| Psychological well-being |

Arrivillaga et al. (2022)

Liu et al. (2023) |

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

|

Depression |

Souza-Pereira et al. (2020) |

Short Depression-Happiness Scale (SDHS)

|

Depression |

Yurdagül et al. (2021) |

9 items-Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

|

Depression |

Fujita et al. (2022) |

Generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7)

|

Anxiety |

Li, X. et al. (2019)

Fujita et al. (2022) |

Zung's self-rating anxiety scale (SAS)

|

Anxiety |

Li, G. et al. (2019) |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Short Form (STAI-6).

|

Anxiety |

Yurdagül et al. (2021) |

"Mental" ranking de Cantril’s ladder, HBSC Symptom Checklist

|

Psychological well-being |

Boer et al. (2020) |

Subjective Vitality Scale (SVS)

|

Psychological well-being |

Khasmohammadi et al. (2020) |

General Health Questionnaire

(GHQ-12)

|

Psychological well-being |

Yang & Zhu (2023) |

9-item Index of Well-Being

|

Psychological well-being |

Huang et al. (2023) |

| Self-report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) |

Psychological well-being |

Wang et al. (2021) |

| Externalizing Problems |

Form of questions proposed by the authors (Participants’ subjective well-being)

|

Psychological well-being |

Pontes & Macur (2021) |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) |

Self-Esteem |

Chen et al. (2020)

Huang et al. (2023) |

| Escala de Autoestima Corporal (EAC) |

Self-Esteem |

Tamarit et al. (2021) |

| State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES) |

Self-Esteem |

Mathew & Krishnan (2020) |

Health-Risk Behavior Inventory for Chinese Adolescents (HBICA)

|

Suicidal behaviour or Self-harm |

Liu et al. (2023) |

| Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory-Youth Version (DSHI-Y) |

Suicidal behaviour or Self-harm |

Hamdan et al. (2022) |

| Scale of Suicidal Ideation developed. |

Suicidal behaviour or Self-harm |

Kuang et al. (2020) |

| Scales produced by the Beijing Center for Psychological Crisis Research and Intervention |

Suicidal behaviour or Self-harm |

Huang et al. (2020) |

| Form of questions proposed by the authors |

Suicidal behaviour or Self-harm |

Peng et al. (2021a)

Peng et al. (2021b)

|

| Youth Self-Report (YSR) |

Externalizing Problems |

Yang & Zhu (2023) |

| Buss-Perry Scale (AQ) |

Aggressiveness |

Obeid et al. (2019)

Huang et al. (2020) |

Buss and Warren's Aggression Questionnaire (BWAQ)

|

Aggressiveness |

Peng et al. (2022) |

| BARRAT Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11). |

Impulsiveness |

Obeid et al. (2019)

Huang et al. (2020) |

References

- Aguinis, H.; Gottfredson, R.K.; Wright, T.A. Best-practice recommendations for estimating interaction effects using meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2011, 32, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, A.; Iskender, M. Internet addiction and depression, anxiety and stress. International online journal of educational sciences 2011, 3, 138–148. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264550590_Internet_addiction_and_depression_anxiety_and_stress.

- Andrade AL, M.; Enumo SR, F.; Passos MA, Z.; Vellozo, E.P.; Schoen, T.H.; Kulik, M.A.; Niskier, S.R.; Vitalle MS, D.S. Problematic Internet Use, Emotional Problems and Quality of Life Among Adolescents. Psico-USF 2021, 26, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrivillaga, C.; Rey, L.; Extremera, N. Psychological distress, rumination and problematic smartphone use among Spanish adolescents: An emotional intelligence-based conditional process analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2022, 296, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrainian, S.A.; Alizadeh, K.H.; Raeisoon, M.R.; Gorji, O.H.; Khazaee, A. Relationship of Internet addiction with self-esteem and depression in university students. Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene 2014, 55, 86. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264550590_Internet_addiction_and_depression_anxiety_and_stress.

- Baloğlu, M.; Özteke-Kozan H, İ.; Kesici, S. Gender differences in and the relationships between social anxiety and problematic internet use: Canonical analysis. Journal of medical Internet research 2018, 20, e33. Available online: https://wwwjmirorg/2018/1/e33/. [CrossRef]

- Bickham, D.S.; Hswen, Y.; Rich, M. Media use and depression: exposure, household rules, and symptoms among young adolescents in the USA. International Journal of Public Health 2015, 60, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.; Van Den Eijnden RJ, J.M.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Wong, S.-L.; Inchley, J.C.; Badura, P.; Craig, W.M.; Gobina, I.; Kleszczewska, D.; Klanšček, H.J.; Stevens GW, J.M. Adolescents’ Intense and Problematic Social Media Use and Their Well-Being in 29 Countries. Journal of Adolescent Health 2020, 66, S89–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.J.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to meta-analysis; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bousoño, M.; Al-Halabí, S.; Burón, P.; Garrido, M.; Díaz-Mesa, E.M.; Galván, G.; García-alvarez, L.; Carli, V.; Hoven, C.; Sarchiapone, M.; Wasserman, D.; Bousoño, M.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Iglesias, C.; Sáiz, P.A.; Bobes, J. Uso y abuso de sustancias psicotrópicas e internet, psicopatología e ideación suicida en adolescentes. Adicciones 2017, 29, 97–104. Available online: https://adiccioneses/indexphp/adicciones/article/view/811/845. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Mao, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; He, J.; Fan, X. Associations Between Problematic Internet Use and Mental Health Outcomes of Students: A Meta analytic Review. Adolescent Research Review 2023, 8, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Gao, T.; Ren, H.; Hu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Liang, L.; Mei, S. The relationship between bullying victimization and depression in adolescents: Multiple mediating effects of internet addiction and sleep quality. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2021, 26, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S.E. Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic Internet use. CyberPsychology & behavior 2006, 10, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, X. La adicción a los videojuegos en el DSM-5. Adicciones 2014, 26, 91–95. Available online: https://wwwredalycorg/pdf/2891/289131590001pdf. [CrossRef]

- Cardak, M. Psychological well-being and Internet addiction among university students. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET 2013, 12, 134–141. Available online: https://ericedgov/.

- Castellana, M.; Sánchez-Carbonell, X.; Graner, C.; Beranuy, M. El adolescente ante las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación: internet, móvil y videojuegos. Papeles del Psicólogo 2007, 28, 196–204. Available online: https://wwwredalycorg/articulooa.

- Chang, F.C.; Chiu, C.H.; Lee, C.M.; Chen, P.H.; Miao, N.F. Predictors of the initiation and persistence of Internet addiction among adolescents in Taiwan. Addictive Behaviors 2014, 39, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Wang, J.-Y.; Lin, Y.-L.; Yang, S.-Y. Association of Internet Addiction with Family Functionality, Depression, Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem among Early Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Tseng, P.T.; Lin, P.Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Stubbs, B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Wu, C.K.; Chen, Y.W.; Wu, M.K. Internet addiction and its relationship with suicidal behaviors: a meta-analysis of multinational observational studies. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2018, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Liu, X.; Guo, T.; Wu, M.; Chen, X. Internet Addiction and Depression in Chinese Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2019, 10, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]