Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 80-85% of all lung cancer cases, making it the most prevalent form of the disease (1, 2). Globally, lung cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths, with millions of new cases and deaths occurring annually. NSCLC typically affects older adults, with smoking being a major risk factor, although non-smokers can also develop the fatal disease, particularly in cases with mutations in specific driver genes like EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor). NSCLC is often diagnosed in advanced stages due to the lack of early symptoms, leading to poor survival rates compared to other cancers.

The advent of molecular profiling has revolutionized the diagnosis and treatment of NSCLC. Over the last two decades, the identification of specific genetic mutations in NSCLC using next generation sequencing (NGS) has enabled the development of targeted therapies, dramatically improving outcomes for subsets of patients. Understanding the molecular landscape of NSCLC is crucial in determining prognosis and selecting appropriate therapies. Targeted therapies have improved response rates, progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with actionable mutations (3).

The most prevalent driver gene mutation in NSCLC is the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), present in 45% of Asian patients and 20% of Caucasian patients with adenocarcinoma histology (4). KRAS is another common oncogenic driver in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) identified in up to 25% of adenocarcinomas and 3% of squamous cell carcinomas (5, 6).

In general, EGFR-mutant lung cancers are more common in nonsmokers, respond well to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy, and have a higher overall survival rate (7,8). Conversely, KRAS-mutant lung cancers are more common in patients with a history of smoking, do not respond to TKI therapy, and have a lower overall survival rate (9).

Historically, EGFR and KRAS mutations were believed to be mutually exclusive (10). However, over the past few years, there have been emerging case reports showing the co-existence of both mutations in a single case (11). The majority of these co-occurring alterations were detected or enriched in samples collected from patients at with resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment, indicating a potential functional role in driving resistance to therapy. These co-occurring tumor genomic alterations are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and evidence suggests that multiple clonal and sub-clonal cancer cell populations can co-exist and contribute to EGFR TKI resistance (12).

Studies have shown that there is no survival benefit in favor of EGFR/KRAS mutation co-existence. In one study, a patient with concurrent EGFR and KRAS mutations along with ROS1 fusion showed an excellent response to Icotinib but not to crizotinib, suggesting that the EGFR mutation was the oncogenic driver while the ROS1 fusion and KRAS mutation were not (13). In another study, the most frequent co-occurring mutations with sensitizing EGFR mutations included KRAS at 53.9%, followed by ERBB2 at 24.3%, MET at 16.5%, and BRAF at 3.3% (14). KRAS mutations in concomitant drivers were frequently hyper-exchange mutations (25.6% vs. 8.2%, P < .001) compared with KRAS single drivers (15).

Co-existing KRAS mutations in EGFR NSCLCs have been described, despite their prevalence at progression and their role in the response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) remain marginally explored (11). Our case report reviews and contributes to the existing literature on coexisting KRAS and EGFR mutations and their impact on clinical outcomes.

Case Report

In November 2020, a 64-year-old woman presented to the urgent care clinic with complaints of pain in her ribs and back that worsened during breathing. A CT scan showed a 4.5 x 3.5 x 3.5 cm mass in the left lower lobe of the lung, highly suspicious for malignancy. Additionally, numerous bilateral pulmonary nodules and mildly enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, suspicious for metastatic disease, were noted. A PET scan revealed several prominent mediastinal and subcarinal lymph nodes and metabolically active lytic lesions in the left seventh rib, sacrum, and the spinous process of the L5 vertebrae. An MRI of the brain also revealed two brain lesions - one in the superior right frontal lobe and the other in the right parietal lobe, as well as lesions in the cerebellum.

A CT-guided core biopsy of the lung mass confirmed the diagnosis of non-small cell lung carcinoma, morphology compatible with adenocarcinoma.

Molecular testing was initiated. However, due to limited tissue, the specimen was deemed as inadequate. As molecular testing continues to evolve, newer technologies like liquid biopsies (which detect circulating tumor DNA) are becoming more common in clinical practice. This specimen was sent for plasma circulating DNA analysis subsequently and revealed an EGFR L858R mutation at a variant allele frequency of 0.44%. EGFR L858R mutation is a missense alteration located within the kinase domain of the EGFR protein. It is one of the most common mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and predicts sensitivity to EGFR-targeted therapies. It has been reported in 31% of lung adenocarcinoma cases, particularly in East Asian patients.

The patient received a combination of pembrolizumab, pemetrexed, and carboplatin chemotherapy in January 2021 following the guidelines of standard first line treatment. After four cycles, there was a significant reduction in the size of the lung mass. Given the presence of the EGFR mutation, the therapy was further personalized and the patient was started on Osimertinib, which led to further reduction of the mass as observed by imaging studies.

The disease relapsed within two years of treatment and a repeat CT- scan showed a multilobulated 4.8 x 4.2 cm left lower lobe perihilar soft tissue mass lesion with adjacent mass effect around the bronchus. The dose of Osimertinib was increased to 80 mg daily, which was well tolerated by the patient.

The patient subsequently developed pleural effusion which was submitted for cytological analysis. 400 cc of pale yellow fluid was obtained by thoracentesis. A cytological examination revealed metastatic adenocarcinoma (

Figure 1a,

Figure 1b). The cell block contained adequate tumor cells for ancillary testing and next generation sequencing. TTF-1 clone 8G7G3/1 was positive with strong nuclear staining, confirming pulmonary origin of the tumor cells (

Figure 1c). PDL-1, tumor proportion score was 40%. (

Figure 1d).

Figure 1a.

Papanicolaou stain 10X, Thin Prep. Low power examination shows cellular specimen with numerous atypical clusters of cells.

Figure 1a.

Papanicolaou stain 10X, Thin Prep. Low power examination shows cellular specimen with numerous atypical clusters of cells.

Figure 1b.

Papanicolaou stain 20X. High power shows clusters of tumor cells consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1b.

Papanicolaou stain 20X. High power shows clusters of tumor cells consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1c.

TTF1 stain 20X. Tumor cells staining with TTF1 confirming metastatic lung adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1c.

TTF1 stain 20X. Tumor cells staining with TTF1 confirming metastatic lung adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1d.

PDL1 immuno stain 20X. Membrane staining of a portion of tumor cells in cell block.

Figure 1d.

PDL1 immuno stain 20X. Membrane staining of a portion of tumor cells in cell block.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) revealed both EGFR L858R and KRAS G12D mutations. For DNA NGS, tumor DNA was used for multiplex amplification with gene-specific primers targeting the coding exons and exon flanking regions of 275 cancer-related genes using the QIAseq Human Comprehensive Cancer Panel (Qiagen). NGS was performed using the NextSeq2000 (Illumina) and analyzed with CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen). The variants were filtered based on variant allele frequency (VAF, ≥5%), mutation databases, and population-based reference datasets including gnomAD, ClinVar, and COSMIC. NGS confirmed this mutational change with EGFR L858R having a VAF of 49.50% and also detected the presence of KRAS G12D at a VAF of 49.27%. KRAS G12D mutation is an activating alteration within the KRAS gene, a gene commonly mutated in several malignancies, including lung adenocarcinoma. KRAS mutations are associated with poor prognosis in NSCLC and are generally mutually exclusive with EGFR mutations. KRAS G12D has been reported in approximately 20% of lung adenocarcinoma cases. Three variants of unknown significance were also detected in the patient specimen. These were ALK R1436H, LRP1B N2814D and KMT2D S2251L.

Targeted NGS RNA fusion analysis was also performed using a custom Illumina TruSight 523 gene panel, which resulted as negative for RNA fusions.

Following these findings, treatment options were discussed, a change in therapy was made, and the patient was started on Amivantamab. The patient declined enrollment in clinical trials.

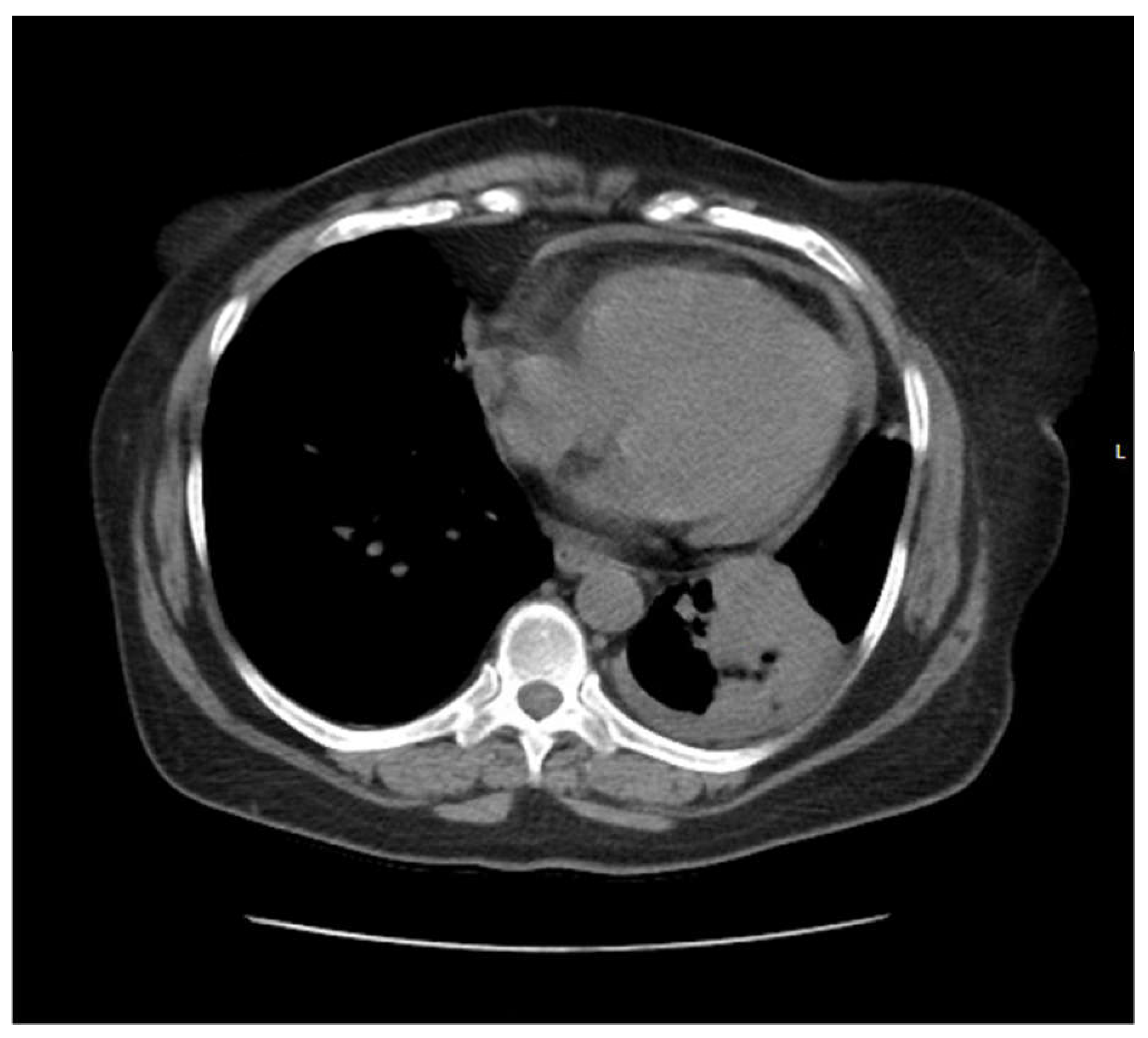

Pic 1.

CT scan showing a left lower lobe perihilar soft tissue mass lesion.

Pic 1.

CT scan showing a left lower lobe perihilar soft tissue mass lesion.

Pic 2.

IR thoracocentesis showing pleural effusion.

Pic 2.

IR thoracocentesis showing pleural effusion.

The patient again presented to the hospital within two months of treatment with nausea, vomiting, and bloody diarrhea. She was admitted for pancytopenia and failure to thrive. The symptoms were suspected to be related to recent chemotherapy. The clinical condition continued to deteriorate despite all efforts, and the patient passed away while on comfort care.

Discussion:

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has enabled the detection of concomitant driver alterations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (12). Many of these alterations emerge or become enriched in patients who develop resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapies, suggesting that they play a role in driving treatment resistance. Importantly, these co-occurring mutations are not always mutually exclusive. In fact, evidence points to the presence of various clonal and sub-clonal populations of cancer cells within a tumor, all contributing to resistance against EGFR-targeted treatments.

The coexistence of EGFR and KRAS mutations is particularly poses a significant therapeutic challenge. While KRAS mutations are well-established drivers of primary resistance to EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC patients without specific molecular selections, their role in acquired resistance in EGFR-mutant patients is less clear. Interestingly, some studies have shown that patients harboring both EGFR and KRAS mutations responded to the EGFR-TKI Icotinib, but not to crizotinib, suggesting that EGFR may still be the dominant oncogenic driver in these cases. However, not all research points to a negative prognosis for EGFR (+)/KRAS (+) patients, possibly because tumors are composed of multiple subpopulations, with the EGFR-mutated cells responding better to treatment while the KRAS-mutant cells continue to drive resistance.

Studies have also shown that the percentage of NSCLC patients with coexisting KRAS and EGFR mutations increases following EGFR-TKI therapy. For example, one study revealed that the prevalence of dual mutations rose to 3.49% (3 out of 86 patients) post-TKI treatment (17). This finding aligns with the hypothesis that dormant tumor cells harboring both mutations may begin to proliferate once EGFR L858R expression is halted, allowing these previously hidden populations to become clinically relevant. In cases where KRAS mutations, particularly at codon 12, coexist with EGFR mutations, the response to treatment tends to be poor.

Furthermore, it has been suggested that KRAS mutations in patients with concomitant driver alterations often involve hyperexchange mutations—mutations that disrupt the normal regulatory function of GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) (14). This impairment keeps KRAS in a continuously active state, fueling uncontrolled cellular signaling and tumor growth. KRAS hyperexchange mutants are particularly aggressive and contribute to the persistent activation of pathways that promote cancer progression. To combat these aggressive forms of cancer, research suggests that a dual inhibition strategy, targeting both EGFR and the MEK pathway, may help overcome resistance in EGFR-mutant tumors expressing KRAS mutations.

In the case of our patient, the KRAS G12D mutation likely emerged as a response to three years of TKI therapy. By 2023, the patient's osimertinib dose was increased due to disease progression, and by July 2024, both EGFR and KRAS mutations were detected. At this point, the treatment plan shifted to include Amivantamab, a dual inhibitor targeting both EGFR and the MEK pathway, which provided temporary stabilization. However, the aggressive nature of the KRAS G12D mutation, possibly a hyperexchange variant, likely contributed to the rapid deterioration in treatment efficacy, ultimately leading to a poor outcome.

This case underscores the complexity of managing NSCLC with coexisting EGFR and KRAS mutations and highlights the importance of continuous molecular monitoring to adapt treatment strategies as the cancer evolves.

Conclusion:

This case highlights the importance of continuous molecular testing in managing NSCLC, especially in cases with rare mutation profiles. The emergence of new mutations during treatment can significantly impact the course of therapy and patient outcomes. In this case, the detection of both EGFR and KRAS mutations guided the selection of a more personalized targeted therapeutic strategy, including the use of Amivantamab. By utilizing Amivantamab, a bispecific antibody targeting EGFR and MET, the therapy was tailored to address the complexity of the patient's molecular profile. This highlights the potential for targeted treatments to provide better disease control and improved outcomes in NSCLC patients with co-occurring mutations.

Additionally, this case reinforces the need for clinicians to remain vigilant through regular molecular monitoring, ensuring that therapeutic strategies are continually optimized as the genetic landscape of the tumor evolves over time.

References

- Erratum to "Cancer statistics, 2024". CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Mar-Apr;74(2):203. doi: 10.3322/caac.21830. Epub 2024 Feb 16. Erratum for: CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Jan-Feb;74(1):12-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820. PMID: 38363123. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S, Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N, Chen W. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022 Feb 9;135(5):584-590. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002108. PMID: 35143424; PMCID: PMC8920425. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Q., Gou, Q., Gan, X. et al. Novel therapeutic strategies for rare mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 14, 10317 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61087-2. [CrossRef]

- Kim ES, Melosky B, Park K, Yamamoto N, Yang JC. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors for EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: outcomes in Asian populations. Future Oncol. 2021 Jun;17(18):2395-2408. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0195. Epub 2021 Apr 15. PMID: 33855865. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judd J, Abdel Karim N, Khan H, Naqash AR, Baca Y, Xiu J, VanderWalde AM, Mamdani H, Raez LE, Nagasaka M, Pai SG, Socinski MA, Nieva JJ, Kim C, Wozniak AJ, Ikpeazu C, de Lima Lopes G Jr, Spira AI, Korn WM, Kim ES, Liu SV, Borghaei H. Characterization of KRAS Mutation Subtypes in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021 Dec;20(12):2577-2584. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0201. Epub 2021 Sep 13. PMID: 34518295; PMCID: PMC9662933. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012 Sep 27;489(7417):519-25. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. Epub 2012 Sep 9. Erratum in: Nature. 2012 Nov 8;491(7423):288. Rogers, Kristen [corrected to Rodgers, Kristen]. PMID: 22960745; PMCID: PMC3466113. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Guo X, Gao Q, Zhang J, Zheng J, Zhao G, Okuda K, Tartarone A, Jiang M. Association between cigarette smoking history, metabolic phenotypes, and EGFR mutation status in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2023 Oct 31;15(10):5689-5699. doi: 10.21037/jtd-23-1371. Epub 2023 Oct 20. PMID: 37969305; PMCID: PMC10636471. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu K, Xie F, Wang F, Fu L. Therapeutic strategies for EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer patients with osimertinib resistance. J Hematol Oncol. 2022 Dec 8;15(1):173. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01391-4. PMID: 36482474; PMCID: PMC9733018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks JL, Broderick S, Zhou Q, Chitale D, Li AR, Zakowski MF, Kris MG, Rusch VW, Azzoli CG, Seshan VE, Ladanyi M, Pao W. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of EGFR and KRAS mutations in resected lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2008 Feb;3(2):111-6. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318160c607. PMID: 18303429. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang TW, Oak CH, Chang HK, Suo SJ, Jung MH. EGFR and KRAS mutations in patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Korean J Intern Med. 2009 Mar;24(1):48-54. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2009.24.1.43. PMID: 19270482; PMCID: PMC2687655. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P76.33 Concurrent EGFR and KRAS Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma: A Single Institution Case Series. Schwartz, C. et al. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, Volume 16, Issue 3, S600 - S601.

- Rachiglio AM, Fenizia F, Piccirillo MC, Galetta D, Crinò L, Vincenzi B, Barletta E, Pinto C, Ferraù F, Lambiase M, Montanino A, Roma C, Ludovini V, Montagna ES, De Luca A, Rocco G, Botti G, Perrone F, Morabito A, Normanno N. The Presence of Concomitant Mutations Affects the Activity of EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in EGFR-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Mar 10;11(3):341. doi: 10.3390/cancers11030341. PMID: 30857358; PMCID: PMC6468673. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju L, Han M, Zhao C, Li X. EGFR, KRAS and ROS1 variants coexist in a lung adenocarcinoma patient. Lung Cancer. 2016 May;95:94-7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.03.005. Epub 2016 Mar 15. PMID: 27040858. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Lin L, Liang C, Pang J, Yin JC, Zhang J, Shao Y, Sun C, Guo R. Landscape of Concomitant Driver Alterations in Classical EGFR-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2024 Aug;8:e2300520. doi: 10.1200/PO.23.00520. PMID: 39102631. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huaying Wang et al., Landscape of Concomitant Driver Alterations in Classical EGFR-Mutated Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 8, e2300520(2024). DOI:10.1200/PO.23.00520. [CrossRef]

- Gini B, Thomas N, Blakely CM. Impact of concurrent genomic alterations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutated lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2020 May;12(5):2883-2895. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.03.78. PMID: 32642201; PMCID: PMC7330397. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choughule A, Sharma R, Trivedi V, Thavamani A, Noronha V, Joshi A et al. Coexistence of KRAS mutation with mutant but not wild-type EGFR predicts response to tyrosine-kinase inhibitors in human lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2014; 111: 2203–2204.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).