1. Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. In 2023, it is estimated that there were more than 235,000 new cases of lung cancer in USA [

1]. In last years, the widespread use of molecular analyses has greatly supported treatment decision, especially for adenocarcinoma (AC), the most common histologic subtype [

2]. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) multigene panels to assess ESCAT (ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets) level I alterations (in the

EGFR and

BRAF genes, for the presence of KRAS p.G12C mutation and in the fusions involving

ALK,

ROS,

MET and

RET genes) are recommended for daily practice [

3].

Larger NGS panels are highly recommended to be performed in clinical research centers in the context of clinical research and in order to increase access to innovative drugs [

4,

5]. In addition,

HER2 mutation and other gene alterations (e.g.

NRG1 fusion), are also recommended to be routinely evaluated as targeted drugs have been recently approved [

6].

The growing trend in the use of NGS in patients with lung AC revealed how other genes (e.g.:

KEAP1,

STK11,

TP53) might have a clinical role, even if no specific targeted drugs have been developed or approved for them [

7,

8].

KRAS mutations are identified in about 30% of lung AC [

3] and frequently occur at exon 2 (in the hotspots located at codons 12 and 13), with the most common change represented by the substitution of glycine for cysteine at position 12 (p.G12C) (39%), followed by the p.G12V (21%) and the p.G12D (17%) [

9].

KRAS alterations have been associated with Caucasian ethnicity, female sex, AC histology and a history of smoking. The mutant KRAS protein has long been considered "undruggable" until the identification of specific KRAS p.G12C inhibitors like sotorasib or adagrasib [

10,

11]. Based on encouraging data from clinical trials showing a benefit in terms of progression free survival (PFS) and safety profile, these two first-in-class drugs in recent years (from 2022) received conditional authorization and accelerated approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), respectively [

12,

13], for patients with advanced lung AC carrying the KRAS p.G12C after first-line treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), with or without platinum-based chemotherapy [

9,

14,

15].

Even though the prognostic value of

KRAS mutation in lung AC has not yet been defined, many retrospective studies exploring the role of these mutations have been published [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Many recent clinical studies have pointed out a possible impact on clinical outcome of the interaction of

KRAS mutations with other alterations [

14,

21,

22,

23]. For example, co-alterations of

KRAS+

TP53 or

STK11 genes seem to have a negative prognostic impact based on results from different retrospective trials [

14,

20,

24]. Another important aspect is the immune profile of these patients. Tumors with a

KRAS+

TP53 co-mutation generally exhibit significant upregulation of PD-L1 expression, whereas those with a

KRAS+

STK11 co-mutation are frequently negative for PD-L1 expression. Therefore, in the future, knowledge of gene alterations concomitant to

KRAS mutations could guide the use of therapies, especially ICIs [

24,

25].

Despite significant progress in the molecular characterization of NSCLC, stratifying patients based on their molecular profiles remains a major clinical challenge. The biological complexity of the tumor, combined with the frequent presence of co-mutations and intra-tumoral heterogeneity, makes it difficult to predict clinical behavior and response to targeted treatments. For instance, while

KRAS mutations are among the most common, their prognosis varies significantly depending on the concomitant presence of other genetic alterations, such as

TP53 or

STK11, which impact therapy response and clinical outcomes [

25]. This variability highlights the need to improve the interpretation of molecular data to optimize personalized therapeutic strategies and increase clinical success rates.

The majority of the studies published to date focused on analyzing the effect of the molecular pattern in metastatic lung AC (stage IV disease), while little is known about early stages. To better clarify this aspect, we conducted a retrospective real-world analysis of all consecutive lung AC patients, therefore including all the stages, who were followed in a single center, the Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland (IOSI). Our main objective was to unveil correlations between molecular characteristics and survival in patients with KRAS-mutant lung AC; in particular, we focused our attention on early stage cancers, to better understand the influence of molecular analyses in this setting. Above all, we explored the clinical role of KRAS and TP53 co-mutations as prognostic factor.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population and Study Design

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of all consecutive patients first diagnosed with lung AC, regardless of the stage, from the first of January 2018 to 31 August 2022. The study was conducted at IOSI and all patients received a treatment based on the stage of the tumor, which was decided after a multidisciplinary discussion and in accordance with the recommendations of the European guidelines [

1,

2].

For each patient, we collected clinical pathological data from electronic medical records, including gender, age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) at the time of diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), smoking history (classified as never, former, or current smokers), laboratory values, tumor histology, molecular analysis, tumor staging at the time of diagnosis according to the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer [

26], sites of metastatic disease, treatments received, and outcomes (date of progression, death, or last follow-up).

This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (BASEC: 2023-01209; Rif. CE 4402) and all the patients signed the informed consent.

Main inclusion criteria were age of 18 years or older at the time of diagnosis; a diagnosis of non squamous non-small cell lung cancer (non-sq NSCLC) and availability of clinical data. Main exclusion criteria included unavailability of clinical data and absence of sufficient amount of tissue for performing the molecular characterization.

2.2. Treatment Characteristics

Staging procedures and treatment proposals were developed according to the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines and were evaluated within a multidisciplinary team based on tumour staging according to the Union for International Cancer Control UICC TNM eight edition. The decision-making process was carried out by specialists with proved expertise in thoracic oncology and after consultation with the patient. A personalized approach was offered according to tumor-related factors (e.g. molecular pathology, PD-L1 expression) and individual factors (e.g. age, performance status - PS, preexisting comorbidities and patient’s preferences).

All patients with early stage or locally advanced NSCLC were discussed in a multidisciplinary tumour board (MTB). In general, in patients with clinical stages I–III NSCLC, detailed loco-regional staging according to ESMO Clinical Guidelines was performed [

27]. Patients with stage I NSCLC underwent surgery with lobectomy or anatomical resection combined with lymph node dissection. Stage II patients underwent surgery (lobectomy or anatomical segmentectomy resection with lymph node dissection). Adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy was offered to patients with resected stage II and III NSCLC. Patients with resectable Stage III NSCLC received surgery (lobectomy or pneumonectomy with lymph node dissection) and (neo-) adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy whereas non-resectable Stage IIIB were treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy with platinum-based doublet, followed by maintenance durvalumab for one year. Generally, systemic therapy was offered to all stage IV patients with PS 0-2. Patients with a PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS)≥50% received single-agent immunotherapy as first-line treatment. Patients with a PD-L1 TPS of 1% to 49% received immunotherapy plus platinum-based chemotherapy. For patients with non-sq NSCLC harbouring certain driver alterations (such as in the

EGFR,

ALK,

ROS1,

BRAF,

RET,

MET, or

NTRK genes), first-line treatment consisted of targeted agents based on the mutation type and the availability (SwissMedic approval) [

28].

2.3. Tumor Analysis

The molecular characterization of all samples was conducted at the Institute of Pathology EOC in Locarno, Switzerland. Initially, NGS was used to identify point mutations and small insertions or deletions, while fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was applied for gene fusions. However, starting from 2020, NGS has also been used to detect gene fusions. Genomic DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp DNA Formalin Fixed and Paraffin Embedded (FFPE) Tissue kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA) on three 8 µm thick FFPE sections. The extracted DNA underwent NGS using the Ion Torrent S5XL platform with the commercially available Ion AmpliSeq Colon and Lung Cancer Panel v2 (CLv2) (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The CLv2 panel provides information on the mutational status of 22 genes frequently mutated in lung AC. FISH analysis was performed on FFPE tissue sections following established criteria [

16,

18]. Immunohistochemical evaluation of PD-L1 protein expression was conducted using an automated instrument and the SP263 monoclonal rabbit anti-human antibody [

19]. Starting from 2020, the Archer FusionPlex Lung NGS Panel (Archer, Boulder, CO, USA) was applied for gene fusion detection. In this case total RNA was extracted using the ReliaPrep FFPE Total RNA Miniprep System (Promega, WI, USA) and RNA was analyzed through an anchored Multiplex PCR and NGS. The Archer FusionPlex Lung NGS Panel focuses on detecting gene fusions, including exon skipping, in 14 genes, including

ALK,

ROS1,

RET,

MET,

NTRK1-2-3. A case was defined as mutated in a particular gene if the Variant allele frequency (VAF) in a tissue sample was ≥5% and if the method had a good coverage result (>500 for all the regions).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics and tumor characteristics, including measures such as mean, median, and proportions. Differences in continuous variables were assessed using the two-tailed Fisher's exact test. Overall Survival (OS) was measured from the date of biopsy-proven diagnosis to the date of death. For patients who were still alive at the end of the study, their data were censored at the time of their last available follow-up. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to estimate OS and group comparisons were conducted using the log-rank test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Entire Cohort

We identified 464 patients with non-sqNSCLC consecutively diagnosed in our Institution from January 2018 to August 2022. The characteristics of all the study population are reported in

Table 1: Two hundred and fifty seven were men (55.4%), the median patient age at diagnosis was 73 years (range, 30–99 years). Concerning smoking history, 367 patients (79.1%) were current or former smokers. The majority of cases were diagnosed with lung AC (n = 456; 98.3%). Stage IV cases have been diagnosed in 259 patients (55.8%) with a 16.2% harboring brain metastases. PD-L1 expression was >50% in 114 patients (24.6%). After a median follow-up of 30.47 months, with 229 deaths recorded, the population's median OS (mOS) was 17.5 months. Dividing the population into stages, we observed the following mOS values: for stage I and II mOS has not been reached, for stage III and IV the mOS was 32.7 and 11.8 months, respectively (p<0.0001;

Figure S1). At molecular level, thanks to NGS analysis, we found alterations in different potentially targetable genes (

Figure S2):

KRAS (n=179; 38.6%),

EGFR (n=64; 14.2%),

BRAF (n=15; 3.6%),

HER2 (n=2; 0.4%),

ALK (n=10; 2.1%),

ROS1 (n=1; 0.2%),

RET (n=1; 0.2%),

NTRK (n=1; 0.2%),

MET exon skipping (n=15; 4.7%). Other genomic alterations have been identified: 203 (43.7%) patients had a mutation in the

TP53 gene, 17 (3.7%) in

STK11 and 42 (9%) in other genes including

FGFR2,

SMAD4,

ERBB4,

PTEN,

CTNNB1,

PIK3CA and

FBXW7.

3.2. Impact of KRAS Mutational Status

The clinical and molecular characteristics of

KRAS mutant are described in

Table 2: 98 were men (54.7%), the median patient age at diagnosis was 70 years (range, 45–86 years) and 160 patients (89.2%) were current or former smokers. Most patients were diagnosed with lung AC (n = 177; 98.9%) and 100 (55.9%) had clinical stage IV disease at diagnosis, with a 14% incidence of brain metastases. PD-L1 expression levels were >50% in 55 patients (30.7%). The main

KRAS mutations detected were p.G12C (47.5%), p.G12V (19%) and p.G12D (11.7%) changes.

To assess correlations among the various clinical-molecular characteristics, we used the two-tailed Fisher's exact test and we observed a statistically significant association between having a KRAS mutation and a positive smoking history (p<0.0001). Instead, there were no associations between the presence of KRAS mutations and gender, BMI, age at diagnosis, brain metastases, or TNM stage. Finally, there was a statistically significant association between the presence of KRAS mutations and the absence of EGFR (p<0.0001) and BRAF (p=0.004) mutations, and ALK rearrangements (p=0.008). Therefore, our data confirmed the mutual exclusivity among these molecular alterations.

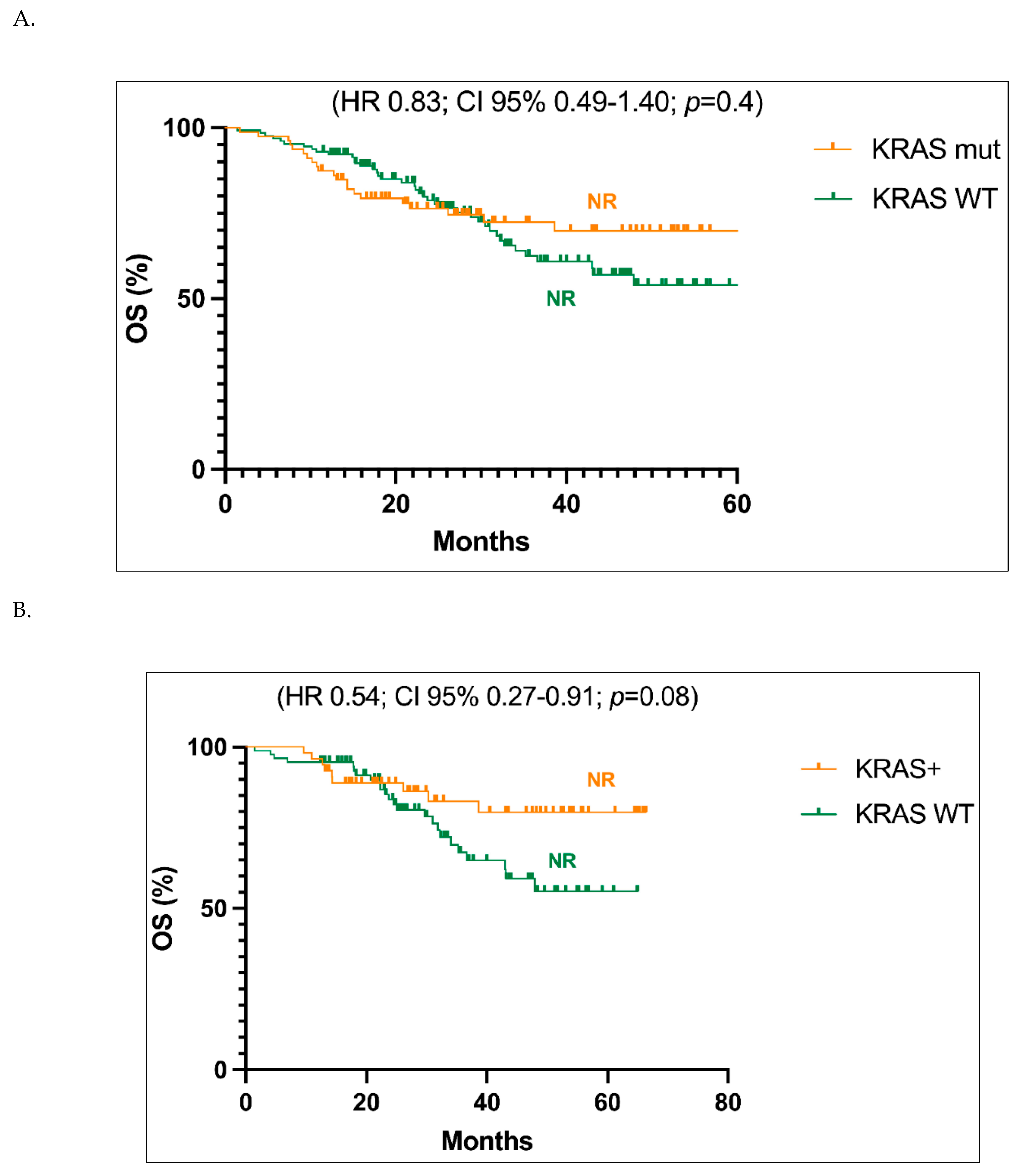

Focusing on stages I-III, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed a not reached value of mOS in both patients with

KRAS mutant tumors and with a

KRAS WT sequence, with no significant statistical difference between these two groups (HR 0.83; CI 95% 0.49-1.40; p=0.4;

Figure 1A). Similar results were obtained when only early stages (stage I and II) were taken into account, although a trend in favour of better follow-up for

KRAS mutant with respect to

KRAS WT cases can be observed, with a HR value of 0.54 (Cl 95% 0.27-0.91; p=0.08) (

Figure 1B).

3.3. Impact of Co-Occurring Mutation

Table 3 reports the number of cases with

KRAS WT,

KRAS-only mutations or

KRAS+TP53 co-mutations subdivided according to the stages. The number of cases with

KRAS mutations and

KRAS WT are well balanced in all the stages.

As described in

Table 2, we have also identified concomitant mutations in 43% of cases, involving genes such as

TP53 (74%),

STK11 (14.3%), and others (24.7%;

MET,

BRAF,

FGFR2,

SMAD4,

ERBB4,

PTEN,

CTNNB1,

PIK3CA,

FBXW7).

Among these molecular alterations, the only statistically significant correlations were those between

KRAS and

STK11 and

KRAS and

TP53. As regards the first couple, among 17 patients with

STK11 mutations, 11 had concurrent

KRAS mutations (p=0.03). Concerning the second couple, our data revealed a statistically significant higher occurrence of

TP53 mutations in patients with

KRAS WT tumors compared to those with

KRAS mutation (31.17% vs. 12.34%, p<0.0001).

TP53 co-mutation also appears to be correlated with the disease stage. The probability of an early stage diagnosis is higher in individuals without co-mutations (

KRAS-only). Fisher's exact test revealed that in patients with

KRAS+

TP53 co-mutations, compared to those with

KRAS-only tumors, there were a greater likelihood of being diagnosed at stage IV rather than stage I, II and III (p=0.01). Interestingly, in our cohort, only 5.4% (3 patients out of 55) of patients with

KRAS and

TP53 co-mutations has stage I at diagnosis (

Table 3).

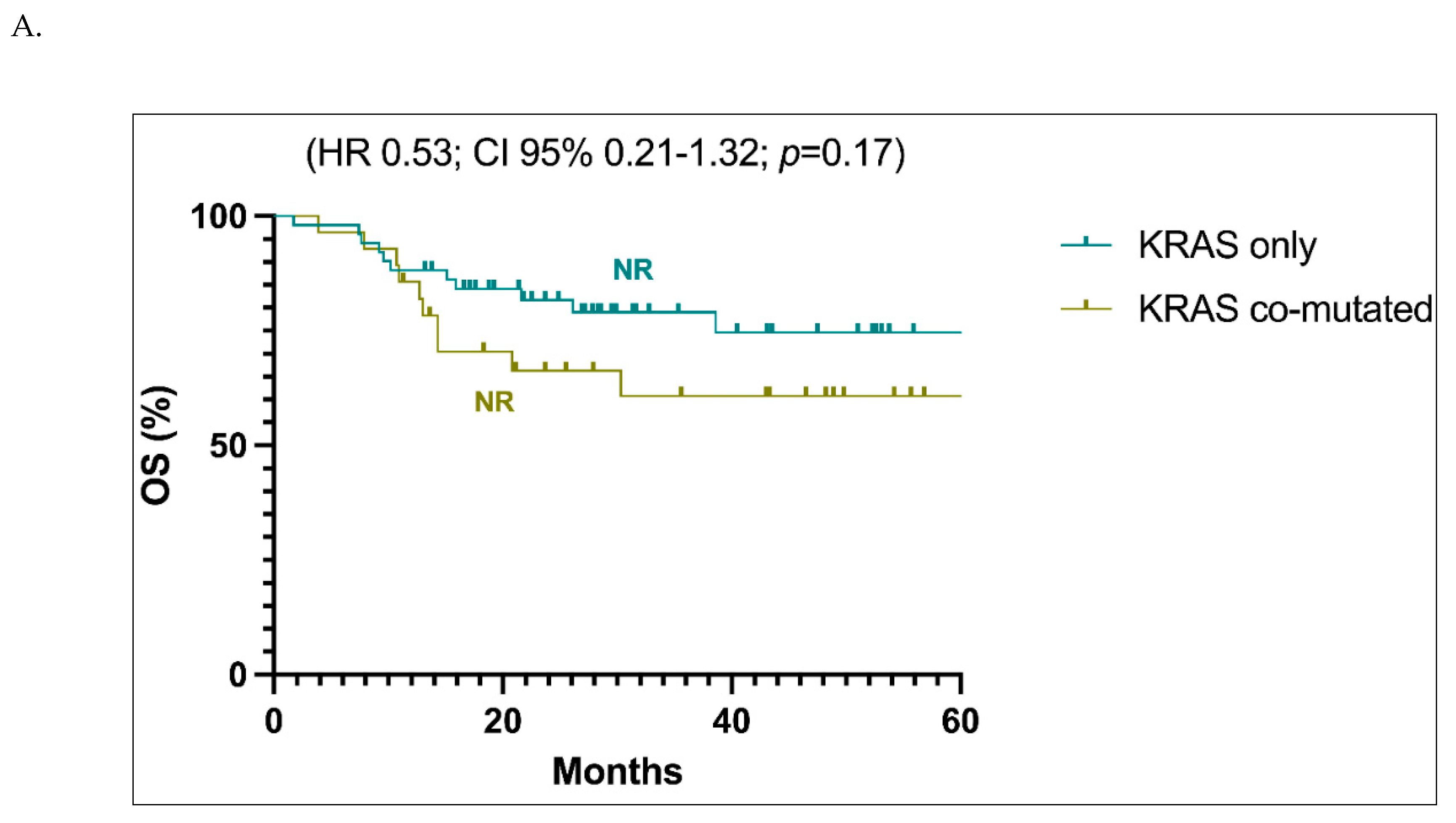

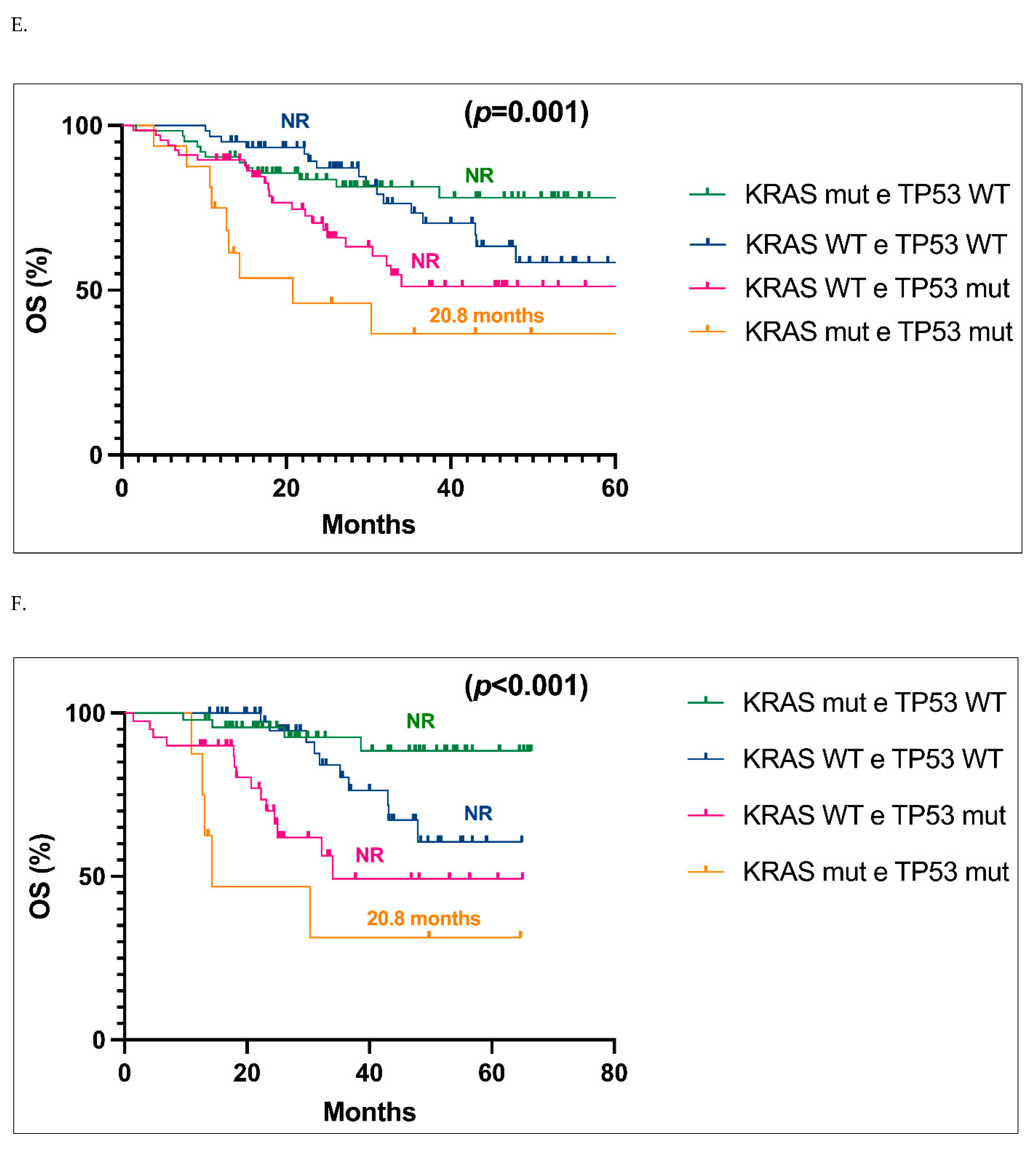

The survival analyses did not reveal a statistically significant difference between stages I-III patients with

KRAS-only tumors versus those with

KRAS co-mutations, although a trend in favour of better prognosis for

KRAS-only patients can be observed (

Figure 2A). Both populations exhibited a not reached value of mOS (HR 0.53; CI 95% 0.21-1.32; p=0.17). The trend in favour of better prognosis for

KRAS only patients in stages I-III became significant when only stages I and II were evaluated: in this cases, the HR value is 0.15 (Cl 95% 0.03-0.67; p=0.01) (

Figure 2B).

Upon analyzing specific co-mutations, we found that patients with co-mutated

KRAS+

TP53 tumors had a significantly shorter mOS, while those with

KRAS+

STK11 co-mutations had comparable mOS to

KRAS-only patients whether stages I-III (p=0.008,

Figure 2C) or stage I-II were analyzed (p=0.004,

Figure 2D).

In light of the obtained results, we analyzed OS of patients with stage I-III or only I-II carrying both

KRAS+

TP53 mutations, compared to those with only

KRAS or only

TP53 alterations and those with

KRAS and

TP53 WT status (

Figure 2E,F, respectively). The four subgroups displayed a statistically significant different OS in both groups of patients (p=0.001,

Figure 2E; p<0.001,

Figure 2F), with patients carrying a simultaneous

KRAS+

TP53 mutations experiencing the worst OS (20.8 months) (

Figure 2E,F).

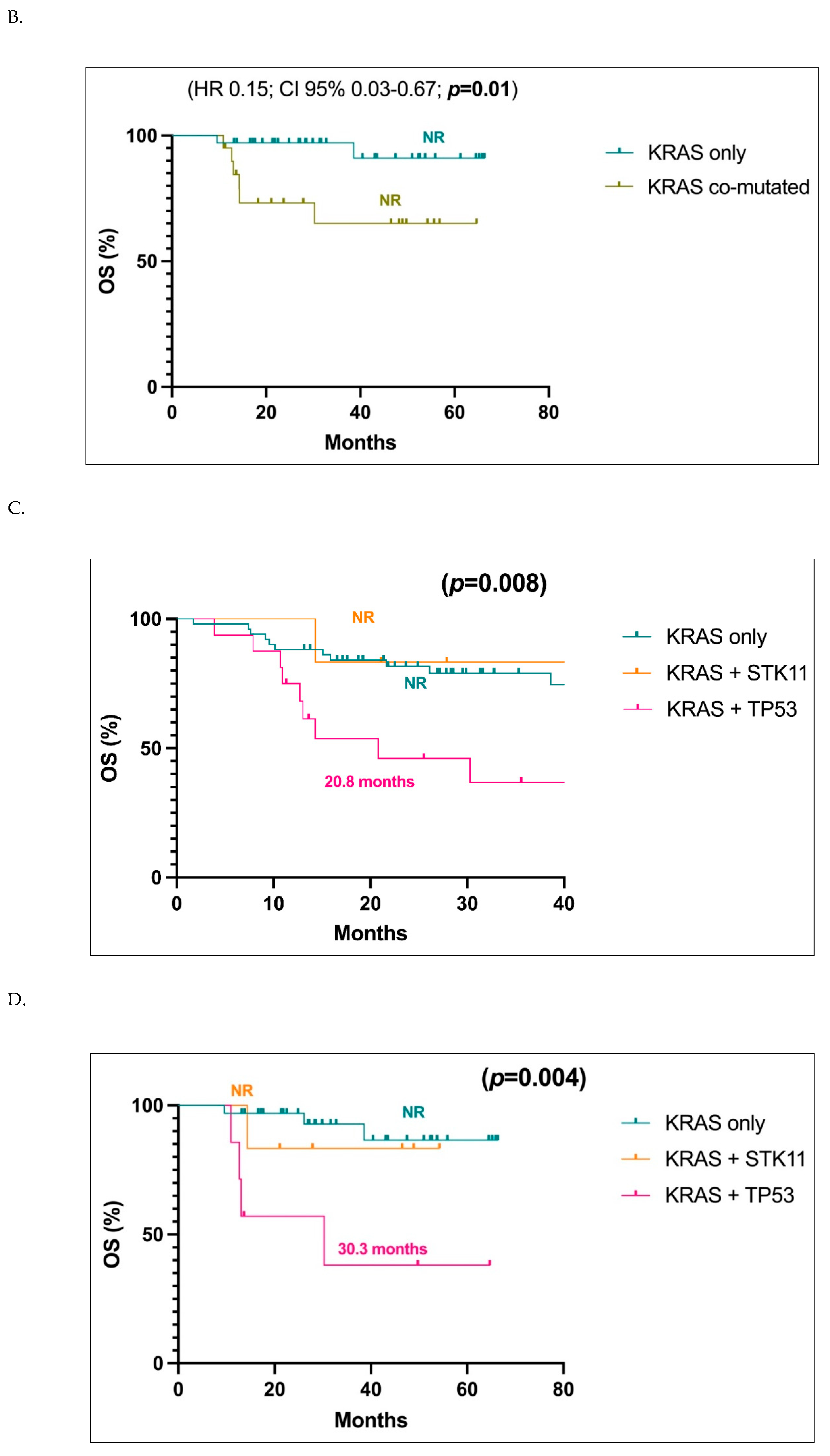

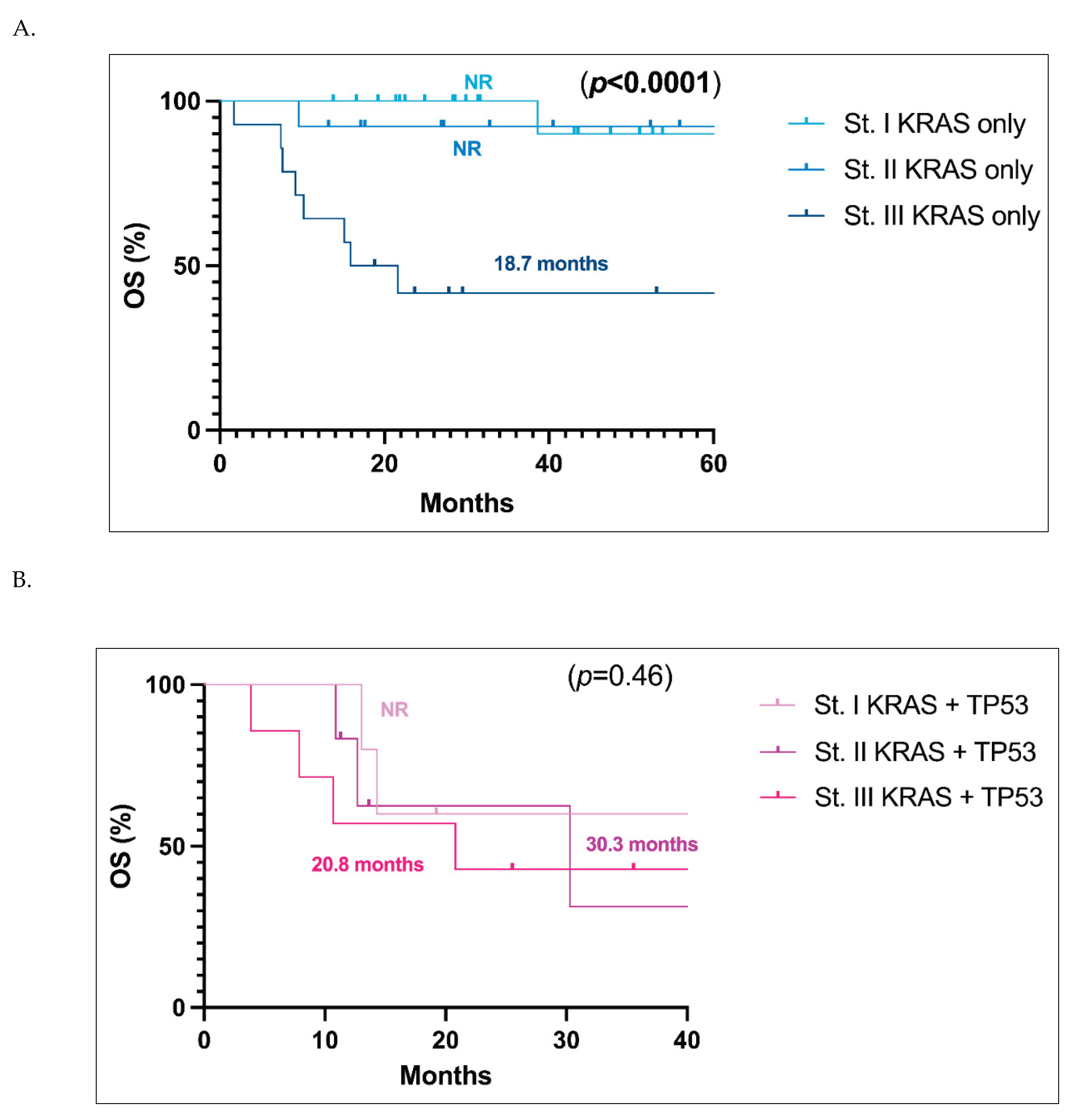

Finally, we compared the OS of

KRAS-only (

Figure 3A) patients and

KRAS+

TP53 co-mutated patients (

Figure 3B) in stage I vs II vs III respectively. In patients with only a

KRAS mutation, stage I and II patients have not yet reached a median OS, whereas in stage III, the mOS was 18.7 months, with a significant difference between stage III vs I and II (

p<0.0001), while curves of stage I and stage II for

KRAS-only patients are substantially superimposable (

Figure 3A). When

KRAS+

TP53 co-mutated cases were taken into account, on the contrary, the curves of stages I, II and III were all superimposable, with mOS not reached in stage I, 30.3 months in stage II, and 20.8 months in stage III (

p=0.46) (

Figure 3B).

4. Discussion

Here we report a retrospective analysis of a consecutive Swiss population-based ns-NSCLC cohort, subjected to NGS analysis at the time of diagnosis, focusing especially on stage I-III or stage I-II KRAS mutant patients.

Multiple previous analyses focused on stage IV cohorts and yielded conflicting evidence regarding the predictive significance of these concurrent alterations [

10,

12,

20]. With access to molecular data from stage I-III patients, our study has the advantage of including all patients diagnosed with ns-NSCLC, enabling us to identify correlations among markers that may be specific to certain stages. We decided to especially focus our attention on early-stages because today little attention has been paid to the effect caused by specific molecular alterations on therapies in early stages, especially in stage I.

Our initial analysis showed that the incidence rates of targetable mutations were generally consistent with the available evidence confirming the representativeness of our cohort. An exception is

KRAS, which appeared to be more prevalent in our dataset compared to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) group [

13]. We presume that this difference can be attributed to the high rate of smokers in our region, a factor that is directly correlated to the incidence of

KRAS mutations [

9], as also demonstrated in our cohort.

Our analyses, on one hand confirmed the mutual exclusivity of EGFR, KRAS and BRAF mutations and ALK rearrangements, and on the other hand pointed out that TP53 mutations occur more frequently in KRAS WT patients and in advanced/metastatic (IV) stages, thus indirectly indicating a particular negative prognostic factor for such a molecular profile.

Then we took into consideration the clinical data and matched them to the molecular ones. At first, as expected, the mOS by stage confirmed that patients outcome worsen when the disease is diagnosed at a more advanced stage compared to an earlier stage, further indicating the consistency of our cohort.

To better understand the impact of the presence of a

KRAS mutation, we compared the mOS with and without this alteration of patients with stage I-III or stage I-II. The analysis confirms that the presence of the

KRAS mutation by itself should not be considered a prognostic factor. On the contrary, it appears that the prognosis should be more significantly influenced by the presence of concurrent mutations. At first, specifically in stages I-II, the occurrence of a mutation limited to

KRAS (“

KRAS-only”) identifies a group of cases with better prognosis if compared to patients with

KRAS co-mutations. This datum is lost when stage III patients are added, although a similar trend can still be observed. However, the role played by co-mutations may not be unique and therefore we evaluated our cohort dividing co-mutated patients into two groups: one with

KRAS+

TP53 mutations and one with

KRAS+

STK11 mutations, i.e the two largest subgroups of patients. From this grouping, we obtained a significant difference which is highly noticeable, as we demonstrated that patients with stage I-II carrying both

KRAS+

TP53 mutations experience a worse outcome if compared to patients with only a

KRAS mutation or carrying

KRAS+

STK11 co-mutations. In 2019, La Fleur and colleagues had already analyzed a cohort of patients who underwent surgery for early-stage NSCLC, and they found a worse prognosis in individuals with

TP53 mutations, thus reinforcing the results of our study [

14].

The observed adverse prognostic significance of TP53 mutations in NSCLC is strengthened by a further stratification: patients with only TP53 alterations had a poorer prognosis compared to those with KRAS-only mutations or those with KRAS and TP53 WT status. However, when we compare the mOS of these patients with those having KRAS+TP53 co-mutations, we can observe that the mOS was even worse than the TP53-only subgroup, thus hypothesizing a synergistic negative effect of these two alterations.

This concept is ultimately affirmed by the analysis of OS in KRAS-only patients and KRAS+TP53 co-mutated patients in stages I, II and III evaluated separately. In KRAS-only subjects, we observe a worse OS among stage III patients than patients at stage I and II (the last two groups showing a superimposable value between them). Conversely, in KRAS+TP53 co-mutated patients, both stage I and stage II exhibit OS rates superimposable between them but also similar to those in stage III. Our results may indicate that KRAS+TP53 co-mutated patients at stage I experience a really negative outcome, similar to the one of stage III patients.

Our analyses may therefore have relevant clinical implications. In fact, recent phase III studies have prompted the clinical community to reconsider the treatment approach for patients with early-stage NSCLC. The CheckMate 816, and other recent trials have shown that chemo-immunotherapy provides benefits for patients starting from stage II, although the subgroup analysis has mainly shown greater advantages in stage III patients [

21,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Additionally, in the adjuvant setting, the PEARLS and IMPOWER 010 trials have demonstrated benefit in adding immunotherapy to adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II-III patients. Also in this case, the evidence is stronger for the stage III subgroup [

22,

23]. To date, there is no biomarker which enable to identify patients with early stage I-II NSCLC that could benefit more from a (neo)- adjuvant (chemo)-immunotherapy. Therefore, it remains unclear whether pre- or post-operative chemo-immunotherapy is necessary for all patients with stage II NSCLC. We likely lack sufficient information to determine whether some patients diagnosed at these stages may benefit more from one therapy over another. However, our analysis suggests that the molecular characterization of tumors may help on this point: patients with a

TP53 mutated or a

KRAS+

TP53 co-mutated tumor seem to have a poor prognosis and maybe they could represent the group of patients which can benefit effectively from chemo-immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting in very early stage (stage I). On the other hand, in our retrospective analysis patients with

KRAS-only tumors exhibit more favourable prognosis suggesting that in this group we may consider a more observational approach and with more data we could potentially reduce pharmacological therapies in the initial stages.

In our study, unlike the

KRAS+

TP53 double mutant, considerations and analysis regarding

KRAS+

STK11 co-mutations cannot be extended further due to low number of cases harbouring mutations in both these markers. The low number of these double mutant cases explain also why we cannot confirm the data in literature reporting how

STK11 co-mutation associate to worse outcomes in NSCLC [

8,

11,

13].

The strength of our study lies in the presence of a homogeneous population, consecutively diagnosed with NGS analysis and treated at the same Institute in accordance with current European guidelines [

1,

2].

At the same time, the fact that we analyzed a small single-cohort of homogenous population could be a limitation. Indeed, we can underestimate the clinical role of less frequently altered genes. As a consequence, the enlargement of the number of cases could permit to obtain data also for the categories that are not enough represented in this study, such as the KRAS+STK11 double mutant.

A second limitation of this study is the relatively small number of genes included in the NGS panel that we applied. This panel is a commercially available solution recommended for diagnostic purposes because it represents a good compromise between low costs and an adequate complete characterization of NSCLC. However, this panel does not include some relevant emerging markers, such as KEAP1, which therefore cannot be evaluated in our cohort (by considering them as KRAS-only mutant cases). Consequently, there was a minority of KRAS-only patients that probably should have been considered within the subgroup of KRAS co-mutated individuals.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our analysis shows that routine NGS provides important information not only for potential actionable mutations but also for the prognostic and predictive role of the presence of co-occurring mutations: in particular, it seems that the assessment of TP53 mutations may be of a pivotal interest even in early stages. This crucial information potentially leads to a molecular reclassification of ns-NSCLC based on the identified alterations and may have important clinical relevance in adapting the treatment with chemo/immunotherapy in the (neo)-adjuvant setting.

Future prospective works must be done to confirm our hypothesis in larger series using more comprehensive panels.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Overall survival analysis of the entire population divided by stages; Figure S2: Driver molecular characteristics of all populations.

Author Contributions

All the authors conceived and/or designed the work that led to the submission, acquired data, and/or played an important role in interpreting the results, drafted or revised the manuscript, approved the final version and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Individual contributions are listed below. Conceptualization, L.M., M.F., P.F.; Investigation, L.M., F.M., J.P., B.P., A.V., S.E., L.G., S.F., M.P., M.I., G.S., M.F. and P.F.; data curation L.M., F.M., J.P., B.P., A.V., M.P. and M.I.; statistical analyses, L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M., J.P., S.E., M.F. and P.F.; writing—review and editing L.M., F.M., J.P., B.P., A.V., S.E., L.G., S.F., M.P, M.I., G.S., M.F. and P.F; supervision, M.F. and P.F.; M.F. and P.F. are co-last authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Institutional funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the ICH-GCP, or ISO EN 14155, as well as all national legal and regulatory requirements. Data were collected and analyzed for study purposes only after the required authorizations from the competent Ethics Committees (Cantonal Ethics Committee, via Orico 5, Bellinzona, Switzerland) (BASEC: 2023-01209; Rif. CE 4402).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to institutional policy.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Adenocarcinoma |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| ECOG PS |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status |

| EMA |

European Medicines Agency |

| ESCAT |

ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets |

| ESMO |

European society for medical oncology. |

| FDA |

US Food and drug administration |

| FFPE |

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded |

| FISH |

Fluoresence in situ hybridization |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| ICIs |

Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| IOSI |

Oncology institute of Southern Switzerland |

| MTB |

Multidisciplinary tumour board |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| Non-sq NSCLC |

Non-squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| NR |

Not-reached |

| NSCLC |

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| PS |

Performance status |

| VAF |

Variant allele frequencies |

References

- Hendriks, L.; Kerr, K.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.; Solomon, B.; et al. Oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, L.; Kerr, K.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.; Solomon, B.; et al. Non-oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstraw, P.; Chansky, K.; Crowley, J.; Rami-Porta, R.; Asamura, H.; Eberhardt, W.E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Groome, P.; Mitchell, A.; Bolejack, V.; et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, F.; Remon, J.; Mateo, J.; Westphalen, C.; Barlesi, F.; Lolkema, M.; Normanno, N.; Scarpa, A.; Robson, M.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with metastatic cancers: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1491–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosele, M.; Westphalen, C.; Stenzinger, A.; Barlesi, F.; Bayle, A.; Bièche, I.; Bonastre, J.; Castro, E.; Dienstmann, R.; Krämer, A.; et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with advanced cancer in 2024: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.T. , Smit E.F., Goto Y., Nakagawa K., Udagawa H., Mazières J. et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in HER2-Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386(3):241-251.

- Li, J. , Shi D., Li S., Shi X., Liu Y., Zhan, Y. et al. KEAP1 promotes anti-tumor immunity by inhibiting PD-L1 expression in NSCLC. Cell Death Dis 2024; 15:175.

- Rosellini, P.; Amintas, S.; Caumont, C.; Veillon, R.; Galland-Girodet, S.; Cuguillière, A.; Nguyen, L.; Domblides, C.; Gouverneur, A.; Merlio, J.-P.; et al. Clinical impact of STK11 mutation in advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 172, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, J. , Abdel Karim N., Khan H., Naqash A. R., Bac, Y., Xiu J. et al. Characterization of KRAS Mutation Subtypes in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 2021;20:2577-2584.

- Zhao, J. , Han Y., Li J., Chai R. & Bai C. Prognostic value of KRAS/TP53/PIK3CA in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett 2019;17:3233-3240.

- Bange, E.; Marmarelis, M.E.; Hwang, W.-T.; Yang, Y.-X.; Thompson, J.C.; Rosenbaum, J.; Bauml, J.M.; Ciunci, C.; Alley, E.W.; Cohen, R.B.; et al. Impact of KRAS and TP53 Co-Mutations on Outcomes After First-Line Systemic Therapy Among Patients With STK11-Mutated Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , Li H., Zhu J., Zhang Y., Liu X., Li R. et al. The Prevalence and Concurrent Pathogenic Mutations of KRAS (G12C) in Northeast Chinese Non-small-cell Lung Cancer Patients. Cancer Manag Res 2021;13:2447-2454.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014;511:543-550.

- La Fleur, L.; Falk-Sörqvist, E.; Smeds, P.; Berglund, A.; Sundström, M.; Mattsson, J.S.; Brandén, E.; Koyi, H.; Isaksson, J.; Brunnström, H.; et al. Mutation patterns in a population-based non-small cell lung cancer cohort and prognostic impact of concomitant mutations in KRAS and TP53 or STK11. Lung Cancer 2019, 130, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, E.; Thawani, R. Current perspectives of KRAS in non-small cell lung cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2024, 51, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V.; Bernasconi, B.; Merlo, E.; Balzarini, P.; Vermi, W.; Riva, A.; Chiaravalli, A.M.; Frattini, M.; Sahnane, N.; Facchetti, F.; et al. ALK testing in lung adenocarcinoma: technical aspects to improve FISH evaluation in daily practice. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuta, K.; Kohno, T.; Yoshida, A.; Shimada, Y.; Asamura, H.; Furuta, K.; Kushima, R. RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung carcinoma: a clinicopathological and molecular analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubendorf, L.; Büttner, R.; Al-Dayel, F.; Dietel, M.; Elmberger, G.; Kerr, K.; López-Ríos, F.; Marchetti, A.; Öz, B.; Pauwels, P.; et al. Testing for ROS1 in non-small cell lung cancer: a review with recommendations. Virchows Arch. 2016, 469, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garon E., B. , Rizvi N. A., Hui R., Leighl N., Balmanoukian A. S., Eder J. P. et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2018-2028.

- Arbour, K.C.; Jordan, E.; Kim, H.R.; Dienstag, J.; Yu, H.A.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Lito, P.; Berger, M.; Solit, D.B.; Hellmann, M.; et al. Effects of Co-occurring Genomic Alterations on Outcomes in Patients withKRAS-Mutant Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Spicer, J.; Lu, S.; Provencio, M.; Mitsudomi, T.; Awad, M.M.; Felip, E.; Broderick, S.R.; Brahmer, J.R.; Swanson, S.J.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felip, E. , Altorki N., Zhou C., Csőszi T., Vynnychenko I., Goloborodko O. et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021;398:1344-1357.

- O’bRien, M.; Paz-Ares, L.; Marreaud, S.; Dafni, U.; Oselin, K.; Havel, L.; Esteban, E.; Isla, D.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Faehling, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy for completely resected stage IB–IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (PEARLS/KEYNOTE-091): an interim analysis of a randomised, triple-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1274–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bironzo, P.; Cani, M.; Jacobs, F.; Napoli, V.M.; Listì, A.; Passiglia, F.; Righi, L.; Di Maio, M.; Novello, S.; Scagliotti, G.V. Real-world retrospective study of KRAS mutations in advanced non–small cell lung cancer in the era of immunotherapy. Cancer 2023, 129, 1662–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M. , Xu T. & Chan, P. KRAS/LKB1 and KRAS/TP53 co-mutations create divergent immune signatures in lung adenocarcinomas. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2021;13:17588359211006950.

- Detterbeck, F.C.; Boffa, D.J.; Kim, A.W.; Tanoue, L.T. The Eighth Edition Lung Cancer Stage Classification. Chest 2017, 151, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmus, P.E.; Kerr, K.M.; Oudkerk, M.; Senan, S.; Waller, D.A.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Escriu, C.; Peters, S.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, iv1–iv21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchard, D.; Popat, S.; Kerr, K.; Novello, S.; Smit, E.F.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Mok, T.S.; Reck, M.; Van Schil, P.E.; Hellmann, M.D.; et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29 (Suppl. 4), iv192–iv237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymach, J.V.; Harpole, D.; Mitsudomi, T.; Taube, J.M.; Galffy, G.; Hochmair, M.; Winder, T.; Zukov, R.; Garbaos, G.; Gao, S.; et al. Perioperative Durvalumab for Resectable Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1672–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, T.; Leung, C.H.; Weissferdt, A.; Pataer, A.; Carter, B.W.; Godoy, M.C.B.; Feldman, H.; William, W.N.; Xi, Y.; Basu, S.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in operable non-small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 platform NEOSTAR trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, S.; Kim, A.; Solomon, B.; Gandara, D.; Dziadziuszko, R.; Brunelli, A.; Garassino, M.; Reck, M.; Wang, L.; To, I.; et al. IMpower030: Phase III study evaluating neoadjuvant treatment of resectable stage II-IIIB non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with atezolizumab (atezo) + chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, ii30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, T. , Award M. M., Spicer J. D., He J., Lu S., Sepesi B., et al. Perioperative Nivolumab in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2024;390:1756-1769.

- Wakelee, H. , Liberman N., Kato T., Tsuboi M., Lee S., Gao S., et al. Perioperative Pembrolizumab for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2023;389:491-503.

- Wislez, M.; Mazieres, J.; Lavole, A.; Zalcman, G.; Carre, O.; Egenod, T.; Caliandro, R.; Dubos-Arvis, C.; Jeannin, G.; Molinier, O.; et al. Neoadjuvant durvalumab for resectable non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): results from a multicenter study (IFCT-1601 IONESCO). J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

A. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-III with KRAS-mutated (KRAS mut) versus non-mutated (KRAS WT) status. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. B. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-II with KRAS-mutated (KRAS mut) versus non-mutated (KRAS WT) status. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached.

Figure 1.

A. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-III with KRAS-mutated (KRAS mut) versus non-mutated (KRAS WT) status. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. B. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-II with KRAS-mutated (KRAS mut) versus non-mutated (KRAS WT) status. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached.

Figure 2.

A. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-III with KRAS-only versus KRAS co-mutated tumors. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. B. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-II with KRAS-only versus KRAS co-mutated tumors. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. C. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-III with KRAS-only versus KRAS+STK11 and KRAS+TP53 mutated tumors. Abbreviations: NR, not reached. D. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-II with KRAS-only versus KRAS+STK11 and KRAS+TP53 mutated tumors. Abbreviations: NR, not reached. E. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the stages I-III population with KRAS+TP53 mutations versus only KRAS, only TP53 and KRAS and TP53 WT. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. F. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the stages I-II population with KRAS+TP53 mutations versus only KRAS, only TP53 and KRAS and TP53 WT. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached.

Figure 2.

A. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-III with KRAS-only versus KRAS co-mutated tumors. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. B. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-II with KRAS-only versus KRAS co-mutated tumors. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. C. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-III with KRAS-only versus KRAS+STK11 and KRAS+TP53 mutated tumors. Abbreviations: NR, not reached. D. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the population in stages I-II with KRAS-only versus KRAS+STK11 and KRAS+TP53 mutated tumors. Abbreviations: NR, not reached. E. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the stages I-III population with KRAS+TP53 mutations versus only KRAS, only TP53 and KRAS and TP53 WT. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. F. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the stages I-II population with KRAS+TP53 mutations versus only KRAS, only TP53 and KRAS and TP53 WT. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached.

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) analysis of the KRAS only population in stage I, II, and III respectively. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. B. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the KRAS and TP53 co-mutated population in stage I, II, and III respectively.

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) analysis of the KRAS only population in stage I, II, and III respectively. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached. B. Overall survival (OS) analysis of the KRAS and TP53 co-mutated population in stage I, II, and III respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all population.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all population.

| All population (n= 464) |

|---|

| |

n (%) |

| Sex |

|

| Male |

257 (55.4%) |

| Female |

207 (44.6%) |

| Age at diagnosis [range], years |

|

| |

73 [30–99] |

| Smoking habit |

|

| Current |

220 (47.4%) |

| Former |

147 (31.7%) |

| Never |

80 (17.2%) |

| Unknown |

17 (3.7%) |

| Histology |

|

| Adenocarcinoma |

456 (98.3%) |

| Adeno-squamous carcinoma |

8 (1.7%) |

| Stage at diagnosis |

|

| I |

100 (21.6%) |

| II |

41 (8.8%) |

| III |

62 (13.4%) |

| IV |

259 (55.8%) |

| Brain metastases in stage IV patients |

|

| No |

388 (83.6%) |

| Yes |

75 (16.2%) |

| Unknown |

1 (0.2%) |

| PD-L1 (TPS) expression |

|

| Negative |

168 (36.2%) |

| 1-49% |

166 (35.8%) |

|

> 50% |

114 (24.6%) |

| Unknown |

16 (3.4%) |

| Gene Alterations |

|

| No |

68 (14.66%) |

| KRAS |

179 (38.6%) |

| MET |

15 (3.2%) |

| EGFR |

65 (14%) |

| ALK |

10 (2.2%) |

| ROS |

1 (0.2%) |

| RET |

1 (0.2%) |

| TP53 |

199 (42.9%) |

| STK11 |

17 (3.7%) |

| HER2 |

2 (0.4%) |

| BRAF |

17 (3.7%) |

| NTRK |

1 (0.2%) |

| Other* |

33 (7.1%) |

|

*FGFR2, SMAD4, ERBB4, PTEN, CTNNB1, PIK3CA, FBXW7

|

|

Table 2.

Characteristics of the KRAS mutant population.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the KRAS mutant population.

|

KRAS positive population (n= 179)

|

|---|

| |

n (%) |

| Sex |

|

| Male |

98 (54.7%) |

| Female |

81 (45.3%) |

| Age at diagnosis [range], years |

|

| |

70 [45–86] |

| Smoking habit |

|

| Current |

106 (59.2%) |

| Former |

54 (30.2%) |

| Never |

12 (6.7%) |

| Unknown |

7 (3.9%) |

| Histology |

|

| Adenocarcinoma |

177 (98.9%) |

| Adeno-squamous carcinoma |

2 (1.1%) |

| Stage at diagnosis |

|

| I |

35 (19.6%) |

| II |

20 (11.2%) |

| III |

22 (12.3%) |

| IV |

100 (55.9%) |

| Brain metastases in stage IV patients |

|

| No |

153 (85.5%) |

| Yes |

25 (14%) |

| Unknown |

1 (0.5%) |

| PD-L1 (TPS) expression |

|

| Negative |

59 (33%) |

| 1-49% |

61 (34.1%) |

|

> 50% |

55 (30.7%) |

| Unknown |

4 (2.2%) |

| Mutation type |

|

| p.G12C |

85 (47.5%) |

| p.G12V |

34 (19%) |

| p.G12D |

21 (11.7%) |

| p.G12A |

9 (5%) |

| Other* |

30 (16.8%) |

|

KRAS concomitant alterations |

|

| No |

102 (57%) |

| Yes |

77 (43%) |

| MET |

5 (6.5%) |

| EGFR |

1 (1.3%) |

| ALK |

0 (0%) |

| ROS |

0 (0%) |

| RET |

0 (0%) |

| TP53 |

55 (74%) |

| STK11 |

11 (14.3%) |

| Other** |

14 (18.2%) |

| *p.G12S, G12R, G12F, G13D, G13C, L19F, A146T, Q22K, Q61H, Q61L |

|

|

**BRAF, FGFR2, SMAD4, ERBB4, PTEN, CTNNB1, PIK3CA, FBXW7

|

|

Table 3.

KRAS wt, KRAS mutations and KRAS+TP53 mutations on the basis of tumor stage.

Table 3.

KRAS wt, KRAS mutations and KRAS+TP53 mutations on the basis of tumor stage.

| |

KRAS WT |

KRAS-only |

KRAS+TP53 mut |

| Stage I |

65/285 (22.8%) |

23/102 (22.6%) |

3/55 (5.4%) |

| Stage II |

21/285 (7.4%) |

13/102 (12.7%) |

5/55 (9.1%) |

| Stage III |

40/285 (14%) |

14/102 (13.7%) |

6/55 (10.9%) |

| Stage IV |

159/285 (55.8%) |

52/102 (51%) |

41/55 (74.6%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).