Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

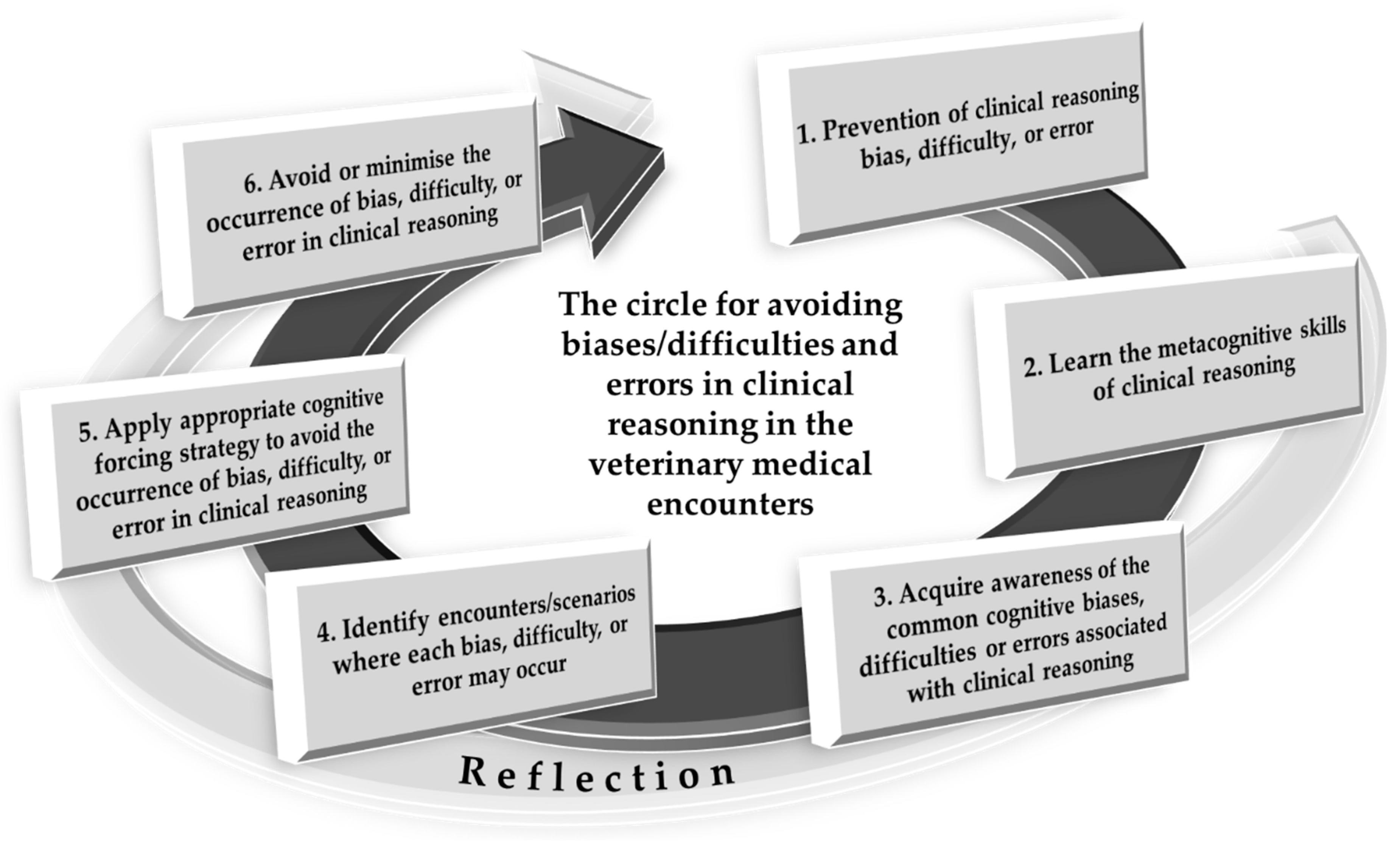

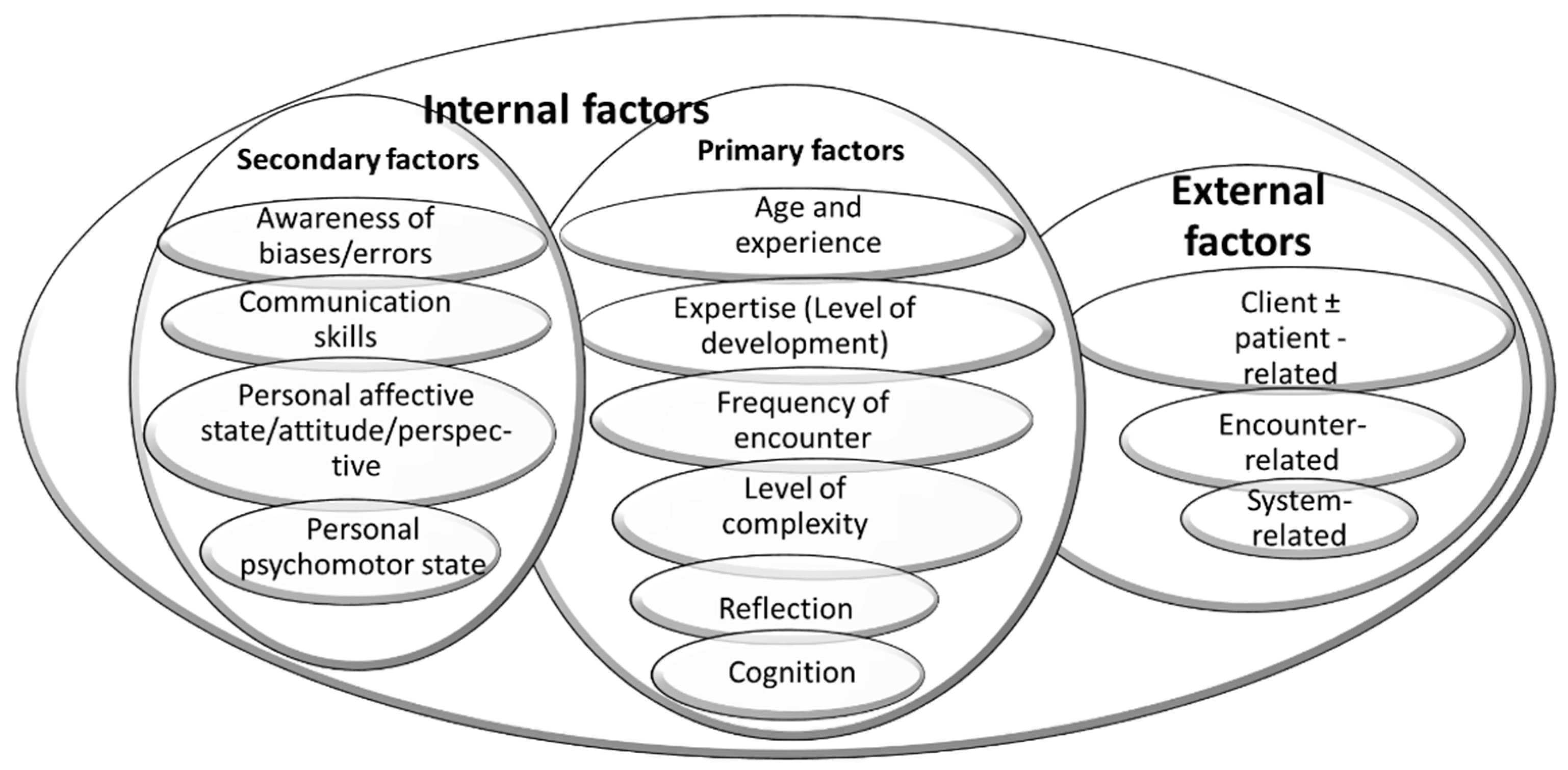

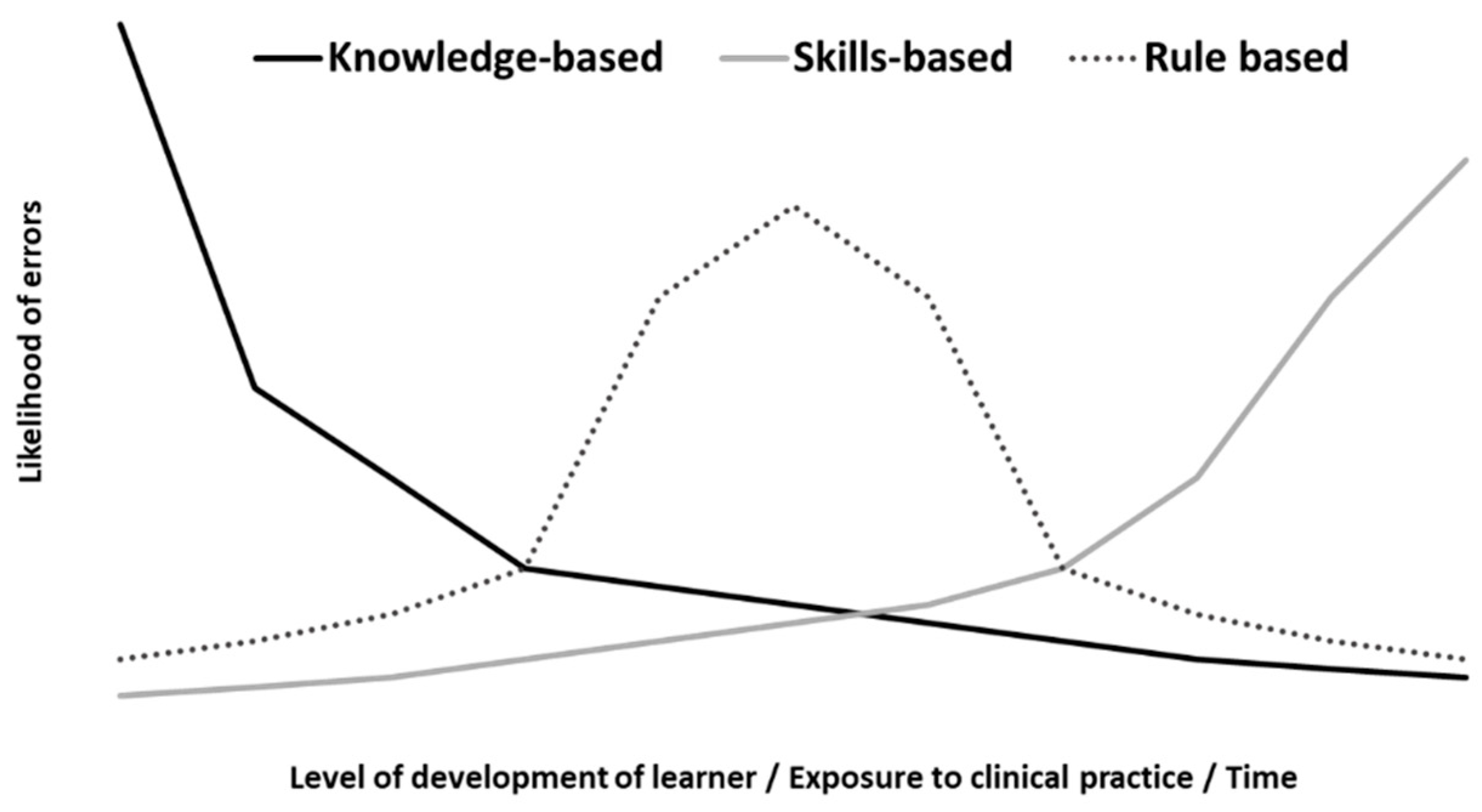

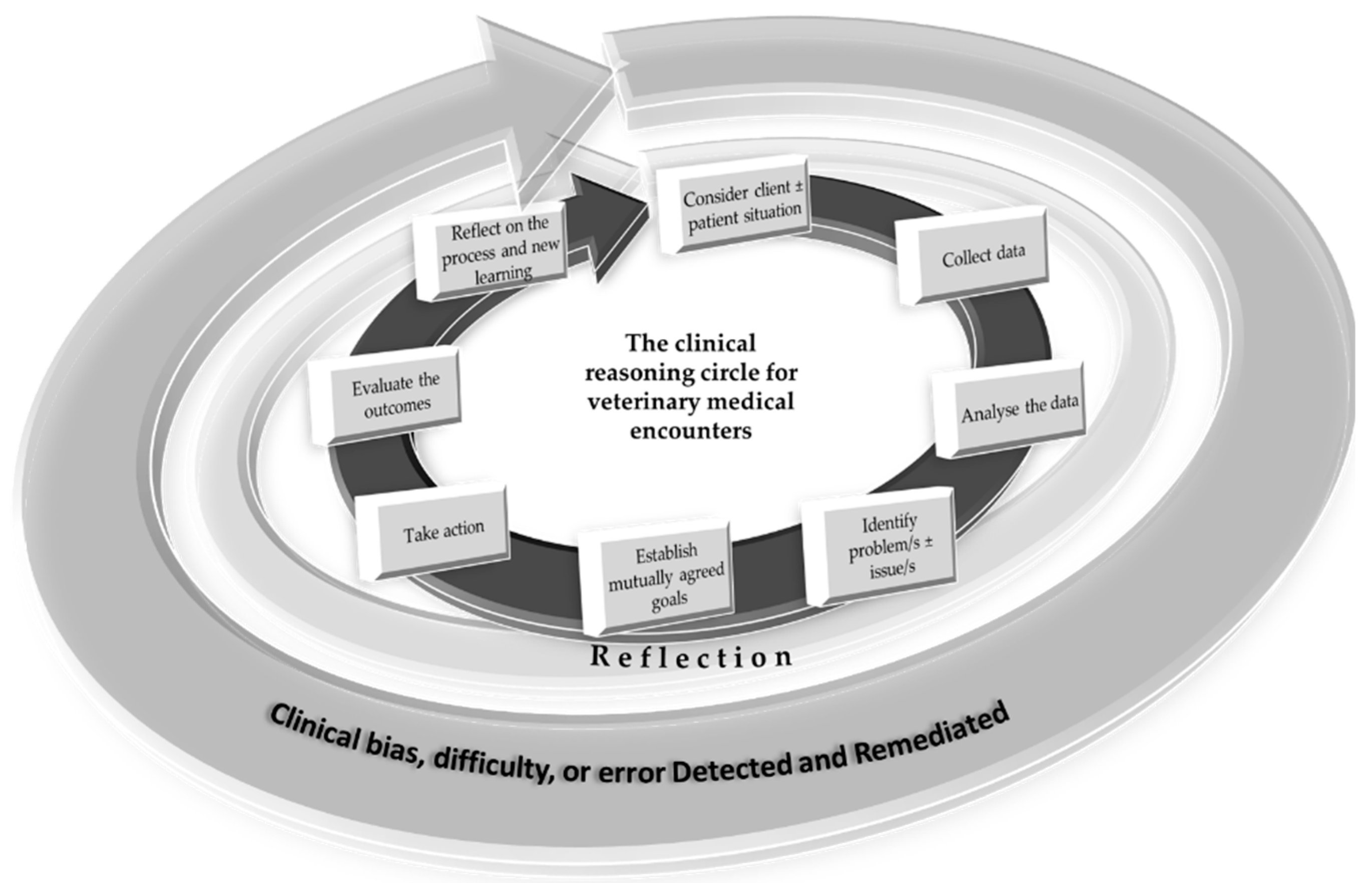

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Example Case

3. Remediation of Difficulties and Errors in Clinical Reasoning

4. Bias in Clinical Reasoning in Veterinary Clinical Encounters and Their Remediation

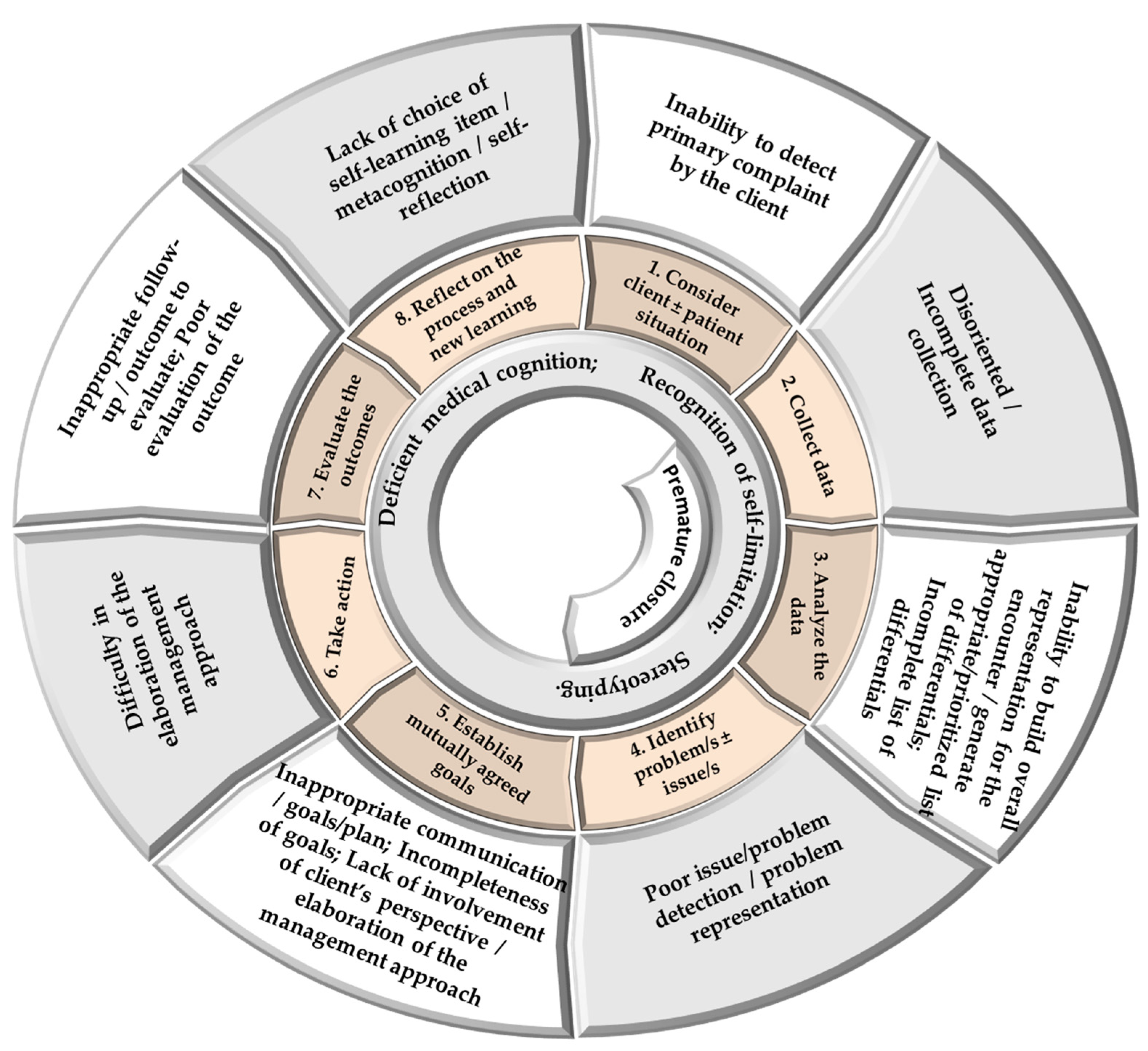

5. Stage-by-Stage Difficulties And Errors in Veterinary Medical Clinical Reasoning

5.1. Stage 1 – Consider Client ± Patient Situation

5.2. Stage 2 – Collect Data

5.3. Stage 3 – Analyze the Data

5.4. Stage 4 – Identify Problem/s ± Issue/s

5.5. Stage 5 – Establish Mutually Agreed Goals

5.6. Stage 6 – Take Action

5.7. Stage 7 – Evaluate the Outcome/s

5.8. Stage 8 – Reflect on Process and New Learning

6. Conclusions

7. Glossary

| Term | Meaning |

| Analytical type of clinical reasoning | Based on more deliberate, explicit, purposeful, rational and slow, and focuses on hypotheses generation and deductive reasoning that is closer to the cognitive processes associated with problem-solving. Common synonyms Deductive, Deliberate, Rational, Rule-governed or System / Type 2 clinical reasoning. |

| Bias (in clinical reasoning) | The preconceived notions and subconscious prejudices that veterinary medical professionals may hold towards clients or patients based on various attributes (e.g., client: age, disability, ethnicity, gender, gender orientation, race, or socioeconomic status; patient: age, breed, production type, reproductive status, sex, and species) and context (e.g., hygiene, production system, and season). |

| Case-based discussion | A clinical teaching tool that consists of a structured approach to learners’ clinical reasoning around written case records and/or structured interviews with a simulated client and patient. |

| Checklists (medical) | An algorithmic listing of actions to assist the learner in consistently carrying out each action, recording the completion, and minimizing errors. |

| Clinical competency | The ability to select and carry out relevant clinical tasks pertaining to the clinical encounter. These aim at resolving the health or productivity problem/s for the client, industry and/or patient, in an economical, effective, efficient and humane manner, followed by self-reflection on the performance indicating the occurrence of deep learning. |

| Clinical encounter | Any physical or virtual contact with a veterinary patient and client (e.g., owner, employee) with the primary responsibility to carry out clinical assessment or activity. |

| Clinical instructor | In addition to the regular veterinary practitioner’s duties, should also fulfil the roles of assessor, facilitator, mentor, preceptor, role model, supervisor, and teacher of veterinary learners in a clinical teaching environment. It may include any of the following: Apprentice/intern in the upper years, Resident, Veterinary educator/teacher, or Veterinary practitioner. |

| Clinical reasoning | The cognitive process interjected with unconscious operations during which a learner or practitioner collects information (clinical and context), process it, comes to an understanding of the problem presented during a clinical encounter, and prepares a management plan, followed by evaluation of the outcome and self-reflection. Common synonyms: Clinical / Diagnostic / Medical: Acumen / Cognition / Critical thinking / Decision-making / Information processing / Judgment / Problem solving / Rationale / Reasoning. |

| Clinical teaching | A form of interpersonal communication between a clinical instructor and a learner that involves a physical or virtual clinical encounter. |

| Cognition | A mental activity or a process for acquiring knowledge and understanding. |

| Cognitive forcing strategy | A group of interventions that use mechanisms to disrupt the heuristic processing of information. It is part of the metacognitive approach. |

| Context | A complex interaction of factors (including, but not limited to, affective/physical state, client, encounter, environment, finances, patient, and social environment) having an effect on the clinical reasoning competence of the learner. |

| Critical thinking | A self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective objective, unbiased analysis and evaluation of information from a variety of sources to form a judgement. |

| Debrief | A formal and structured analysis of the action carried out to obtain useful intelligence or information that could be applied in future. |

| Decision-making | The process of making choices by identifying a decision, gathering information, and assessing alternative hypotheses. |

| Decision-tree | A non-parametric supervised learning algorithm, a hierarchical model that uses a tree-like model of solutions and their possible consequences, including chance event outcomes, resource costs, and utility. |

| Deep learning | Learner aims to master essential academic content; think critically and solve complex problems; work collaboratively and communicate effectively; have an academic mindset; and be empowered through self-directed learning. |

| Deliberate reflection | A systematic review of the grounds of the initial hypothesis and considering alternatives. |

| Dual type of clinical reasoning | Clinical reasoning that utilizes concurrently the analytical and intuitive types. Common synonyms: Dual- / Mixed– process clinical reasoning / theory. |

| Educator in (O)RIME | A learner representative of the advanced part of the clinical curriculum, should be capable of doing all competencies prescribed for the other levels coupled with a critique of the encounter, including important omissions and further research questions, and present the case in a way that can educate others. Learners at this level are truly self-directed. It is a reality that some learners do not reach the level of educator by the time they graduate from veterinary school and may need 2 – 3 years post-graduation or residency to reach this level. |

| Effective feedback | A purposeful conversation between the clinical instructor and the veterinary medical learner with the aim to stimulate further development of clinical competencies and deep earning. |

| Error (medical) | An act of omission or commission in the planning or execution of clinical reasoning or a deviation from the standard with the potential to contribute to an unintended outcome. |

| Five Microskills model | An instructor-centered model of clinical teaching: 1) Get a commitment; 2) Probe for supporting evidence; 3) Teach general rules; 4) Reinforce what was done well; and 5) Correct mistakes. An additional stage is the ‘Debrief’. |

| Flipped classroom | An instructional strategy, a type of blended learning, with the aim to increase learners’ engagement and learning by having them learn at home basic concepts normally covered during class activity and work on applications and building upon these concepts, usually using live problem-solving, during class time. Common synonyms: Backwards/Inverse/Reverse classroom. |

| Guided reflection | A framework to facilitate and assess reflective veterinary medical practice that is usually assisted by the clinical instructor or mentor. |

| Heuristic | The general methods used in problem-solving not following a prescribed methodology, involving discovery, learning or problem-solving, mainly using experiential and trial-and-error bases. |

| Hypothesis-driven data collection | A combination of data collection and clinical reasoning resulting in the early generation of hypotheses and resultant data collection, used to rank competing differentials/management approaches, resulting in limited but focused data collection. Common synonym: Serial-cue approach. |

| Illness script | An organized mental summary of the knowledge of a disorder. Common synonyms: Medical scripts, Schema. |

| Interpreter in (O)RIME | A learner capable of organizing gathered information logically, preparing a prioritized list of differential diagnoses without prodding, and able to support their arguments for inclusion/exclusion of particular diagnoses/tests. The interpreter may or may not be able to propose a management plan for the clinical encounter. |

| Intuitive type of clinical reasoning | Based more on cognitive short-cuts (e.g., heuristics) than real intuitive (gestalt effect) processes. Therefore, even the intuitive type of clinical reasoning is not equal to the real meaning of intuitive (‘judgment made quickly and without apparent effort’). Common synonyms: Experiential, ‘Gut feeling’, Inductive, Non-analytical, Tacit, or System / Type 1 clinical reasoning. |

| Manager in (O)RIME | A learner representative of the mid- to late-part of the clinical curriculum should be capable of summarizing the gathered information in a logical way using veterinary medical language, preparing a prioritized list of differential diagnoses, supporting their arguments and proposing an appropriate management plan. At the manager level, the learner should consider the client’s circumstances, needs and preferences. |

| Mental organization (of knowledge) | All types of concepts and schemes for organizing medical information that promotes retrieval in a clinically relevant manner. |

| Mental representation | A cognitive or metacognitive processing of medical information processing in which medical information is received, recorded, but also modified by a complex process of associating new and previously known elements. |

| Metacognition | Critical awareness of one’s thought processes and learning, and an understanding of the patterns of thinking and learning (‘thinking about thinking’). |

| Mind mapping | A diagram used to visually put medical information into a hierarchy linked to and arranged around a central concept/hypothesis. |

| Observer in (ORIME) | A learner representative of the very early part of the curriculum, lacks skills to conduct a comprehensive health interview and/or present the clinical encounter at rounds or to peers or instructors. Learners at the observer level lack competencies that would contribute to the management of the case and patient care. |

| (O)RIME | Programmatic framework of assessment of competency of veterinary medical learners: (Observer) - Reporter – Interpreter – Manager – Educator. |

| Problem-solving | A complex set of attitudinal, behavioral and cognitive components, often used in a multiple-step process to arrive at the solution (i.e., collection, interpretation and integration of information). |

| Reflection | The metacognitive process that may occur before, during or after an encounter that aims to develop a deeper understanding of the encounter and self ± the team to inform the ongoing and/or future actions, behaviors, and encounters. |

| Reflection-for-action | A process of self-evaluation of the action to happen, including planning for action and doing the action, anticipating the unexpected, and planning and executing adjustments from before, during and after the encounter. |

| Reflection-in-action | A process of self-evaluation of the action as it happens resulting in ongoing adjustments during the encounter. |

| Reflection-on-action | A process of self-evaluation of the action after it has been completed, planning for adjustment in future encounters. |

| Reflective practice | A metacognitive, learner-centered strategy that assists learners in making sense of the learned material and engaging in deep learning. |

| Reporter in (O)RIME | A learner representative of the late part of the pre-clinical and early part of the clinical curriculum, should be capable of gathering reliable clinical information, preparing basic clinical notes, differentiating normal from abnormal, and presenting their findings to peers and/or instructors. |

| Role model | A person who learners look to as a good example and whose behavior they try to copy. |

| Safe (learning) environment | An environment in which a learner feels safe, relaxed, and willing to take risks in pursuing a goal; enhances self-esteem and encourages exploration. |

| Scaffolding | A teaching strategy in which the process is broken into manageable units and learners grasp the concepts and master new skills with a decreased input by the instructor. |

| Self-analysis | Part of the reflective practice characterized by reflective self-assessment of the performance versus goals for the encounter. |

| Self-awareness | Part of the reflective practice characterized by acceptance of constructive criticism and/or recognition of self-limitations. |

| Self-confidence | Part of the reflective practice characterized by the ability to speak in an awkward situation. |

| Self-directed learning | A method in which learners take charge of their own learning process by identifying learning needs, goals, and strategies and evaluating learning performances and outcomes. Learner-centered approach to learning. |

| Self-efficacy | Part of the reflective practice characterized by spending time to self-reflect and avoid/change/enhance actions in the on-going and/or future encounters. |

| Self-esteem | Part of the reflective practice characterized by believing in the self. |

| Self-evaluation / monitoring | Part of the reflective practice characterized by rechecking every decision to be or already made with the aim to adjust it. |

| Self-regulation | Part of the reflective practice characterized by controlling the behavior and expressions of the affective state. |

| Semantic qualifiers | Abstractions expressed using medical rather than lay terminology. Generally, they exist as divergent pairs that aid in comparing or contrasting the hypotheses. Examples of semantic qualifiers include acute or chronic, being affected by XX or previously healthy, bilateral or unilateral, constant or exacerbated by XX, continuous or intermittent, copious or scant, dull or sharp, frequent or rare, generalized or localized, left or right, mild or severe, etc. |

| Simulation | A model of a set of problems or clinical encounters that can be used to teach learners how to do something or deal with an encounter. |

| SNAPPS | A learner-centered model of clinical teaching: 1. Summarize briefly the history and findings; 2. Narrow the differential to two or three relevant possibilities; 3. Analyze the differential by comparing and contrasting the possibilities; 4. Probe the preceptor by asking questions about uncertainties, difficulties, or alternative approaches; 5. Plan management for the patient's medical issues; and 6. Select a case-related issue for self-directed learning. |

| Stimulated recall | A cognitive-forcing strategy used to prompt learners' retrospection by employing diverse stimuli and interview strategies. |

| Team-based learning | A method in which solving of an authentic clinical case using clinical reasoning skills. Particularly useful in developing basic science concepts through a peer-learning approach (learning occurs within a team but also between teams when activity is carried out concurrently with more than one team) and activation of prior knowledge. Learner-centered approach to learning. |

| Work-based learning | An educational method that immerses the learners in the workplace. Common synonyms: Experiential learning; Exposure to practice. |

| Working memory | One of the executive functions of the brain associated with the retention of a small amount of information in a readily accessible form necessary for comprehension, learning, and reasoning |

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonzalez, L.; Nielsen, A.; Lasater, K. Developing students' clinical reasoning skills: A faculty guide. Journal of Nursing Education 2021, 60, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, I.A. Errors in clinical reasoning: Causes and remedial strategies. BMj 2009, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxtoby, C.; Ferguson, E.; White, K.; Mossop, L. We need to talk about error: Causes and types of error in veterinary practice. Veterinary Record 2015, 177, 438–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaccia, T.; Tardif, J.; Triby, E.; Charlin, B. An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: The dual-process theory. Med Educ Online 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koufidis, C.; Manninen, K.; Nieminen, J.; Wohlin, M.; Silén, C. Unravelling the polyphony in clinical reasoning research in medical education. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice 2021, 27, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harasym, P.H.; Tsai, T.-C.; Hemmati, P. Current trends in developing medical students' critical thinking abilities. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences 2008, 24, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, E.J.F.M. Thirty years of illness scripts: Theoretical origins and practical applications. Medical Teacher 2015, 37, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, C.; Vinten, C.; Maddison, J. Use of inductive, Problem-Based clinical reasoning enhances diagnostic accuracy in final-year veterinary students. Journal of veterinary medical education 2020, 47, e0818097r0818091–0818515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audétat, M.C.; Laurin, S.; Sanche, G.; Béïque, C.; Fon, N.C.; Blais, J.G.; Charlin, B. Clinical reasoning difficulties: A taxonomy for clinical teachers. Medical Teacher 2013, 35, e984–e989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audétat, M.-C.; Laurin, S.; Dory, V.; Charlin, B.; Nendaz, M.R. Diagnosis and management of clinical reasoning difficulties: Part II. Clinical reasoning difficulties: Management and remediation strategies. Medical teacher 2017, 39, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amey, L.; Donald, K.J.; Teodorczuk, A. Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 2017, 78, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambe, K.A.; O'Reilly, G.; Kelly, B.D.; Curristan, S. Dual-process cognitive interventions to enhance diagnostic reasoning: A systematic review. BMJ quality & safety 2016, 25, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.; Carney, M.; Khandelwal, S.; Merritt, C.; Cole, M.; Malone, M.; Hemphill, R.R.; Peterson, W.; Burkhardt, J.; Hopson, L.; Santen, S.A. Cognitive debiasing strategies: A faculty development workshop for clinical teachers in emergency medicine. MedEdPORTAL 2017, 13, 10646–10646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrer, W.B.; Sullivan, W.M.; Fleming, A.E. Educational strategies for improving clinical reasoning. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 2013, 43, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.; Sur, M.; Weisse, M.; Moffett, K.; Lancaster, J.; Saggio, R.; Singhal, G.; Thammasitboon, S. Teaching diagnostic reasoning to faculty using an assessment for learning tool: Training the trainer. MedEdPORTAL 2020, 16, 10938–10938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan, E.; Schofield, S. Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 2018, 48, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopasky, A.; Artino, A.R.; Battista, A.; Ohmer, M.; Hemmer, P.A.; Torre, D.; Ramani, D.; Merrienboer, J.v.; Teunissen, P.W.; McBee, E.; et al. Understanding context specificity: The effect of contextual factors on clinical reasoning. Diagnosis 2020, 7, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordage, G. Why did I miss the diagnosis? Some cognitive explanations and educational implications. Academic Medicine 1999, 74, S138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, M.L.; Kissam, S.; Payne, V.L.; Meyer, A.N.D.; Sorensen, A.; Lenfestey, N.; Tant, E.; Henriksen, K.; LaBresh, K.; Singh, H. Cognitive interventions to reduce diagnostic error: A narrative review. BMJ Quality & Safety 2012, 21, 535–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, M.L. Educational strategies to reduce diagnostic error: Can you teach this stuff? Advances in health sciences education : Theory and practice 2009, 14, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.C.; Swee, D.E.; Ullian, J.A. Teaching medical decision making and students' clinical problem solving skills. Medical teacher 1991, 13, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaekers, S.P.J.; Van Beukelen, P.; Kremer, W.D.J.; Van Keulen, H.; Pilot, A. Instructional model for training competence in solving clinical problems. Journal of veterinary medical education 2011, 38, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humm, K.R.; May, S.A. Clinical reasoning by veterinary students in the first-opinion setting: Is it encouraged? Is it practiced? Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 2018, 45, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, M.E.; Thomas, A.; Lubarsky, S.; Gordon, D.; Gruppen, L.D.; Rencic, J.; Ballard, T.; Holmboe, E.; Da Silva, A.; Ratcliffe, T.; et al. Mapping clinical reasoning literature across the health professions: A scoping review. BMC medical education 2020, 20, 107–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Thomas, A.; Gordon, D.; Gruppen, L.; Lubarsky, S.; Rencic, J.; Ballard, T.; Holmboe, E.; Da Silva, A.; Ratcliffe, T.; et al. The terminology of clinical reasoning in health professions education: Implications and considerations. Medical teacher 2019, 41, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Veterinary Boards Council. AVBC Day One Competencies - version 1 January 2024. Available online: https://avbc.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/AVBC-Day-One-Competencies_Final_2024-v1-Jan-24.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. RCVS Day One Competences. Available online: https://www.rcvs.org.uk/news-and-views/publications/rcvs-day-one-competences-feb-2022/ (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- European Coordinating Committee on veterinary Training. List of subjects and Day One Competences as approved by ECCVT on 17 January 2019. Available online: https://www.eaeve.org/fileadmin/downloads/eccvt/List_of_subjects_and_Day_One_Competences_approved_on_17_January_2019.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Norman, G.R.; Monteiro, S.D.; Sherbino, J.; Ilgen, J.S.; Schmidt, H.G.; Mamede, S. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: Cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Academic Medicine 2017, 92, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audétat, M.-C.; Lubarsky, S.; Blais, J.-G.; Charlin, B. Clinical reasoning: Where do we stand on identifying and remediating difficulties? Creative education 2013, 4, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.N.; Ferlini Agne, G.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Teaching clinical reasoning to veterinary medical learners with a case example. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agne, G.F.; Carr, A.M.N.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Assisting the Learning of Clinical Reasoning by Veterinary Medical Learners with a Case Example. Veterinary Sciences 2024, 11, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBee, E.; Ratcliffe, T.; Picho, K.; Artino, A.R.; Schuwirth, L.; Kelly, W.; Masel, J.; van der Vleuten, C.; Durning, S.J. Consequences of contextual factors on clinical reasoning in resident physicians. Advances in health sciences education : Theory and practice 2015, 20, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durning, S.J.; Artino, A.R.; Boulet, J.R.; Dorrance, K.; van der Vleuten, C.; Schuwirth, L. The impact of selected contextual factors on experts’ clinical reasoning performance (does context impact clinical reasoning performance in experts?). Advances in health sciences education : Theory and practice 2012, 17, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croskerry, P. A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Academic medicine 2009, 84, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, M.C. Detecting acute confusion in older adults: Comparing clinical reasoning of nurses working in acute, long-term, and community health care environments. Research in nursing & health 2003, 26, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.G.; Mamede, S. How to improve the teaching of clinical reasoning: A narrative review and a proposal. Medical education 2015, 49, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrandt Dahlgren, M.; Valeskog, K.; Johansson, K.; Edelbring, S. Understanding clinical reasoning: A phenomenographic study with entry-level physiotherapy students. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 2022, 38, 2817–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovski, K.; McArthur, M. The art and science of consultations in bovine medicine: Use of modified Calgary – Cambridge guides. Macedonian Veterinary Review 2015, 38, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBee, E.; Ratcliffe, T.; Lambert, S.; Daniel, O.N.; Meyer, H.; Madden, S.J.; Durning, S.J. Context and clinical reasoning. Perspectives on medical education 2018, 7, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.E. Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2015, 103, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casapulla, S.; Longenecker, R.; Beverly, E.A. The value of clinical jazz: Teaching critical reflection on, in, and toward action. Family medicine 2016, 48, 377–380. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, R.W.; Bordage, G.; Connell, K.J. The importance of early problem representation during case presentations. Academic medicine 1998, 73, S109–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desy, J.; Busche, K.; Cusano, R.; Veale, P.; Coderre, S.; McLaughlin, K. How teachers can help learners build storage and retrieval strength. Medical Teacher 2018, 40, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, L. Teaching clinical reasoning piece by piece: A clinical reasoning Concept-Based Learning method. The Journal of nursing education 2018, 57, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessee, M.A. Pursuing improvement in clinical reasoning: The integrated clinical education theory. The Journal of nursing education 2018, 57, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalet, A.; Guerrasio, J.; Chou, C.L. Twelve tips for developing and maintaining a remediation program in medical education. Medical teacher 2016, 38, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Ferraz Grünewald, S.; Grünewald, T.; Ezequiel, O.S.; Lucchetti, A.L.G.; Lucchetti, G. One-minute preceptor and SNAPPS for clinical reasoning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern Med J 2023, 53, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, A.; Gupta, S.; Pinto-Powell, R.; Jackson, J.; Appel, J.; Roussel, D.; Daniel, M. Diagnosing and remediating clinical reasoning difficulties: A faculty development workshop. MedEdPORTAL 2017, 13, 10650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilminster, S.M.; Jolly, B.C. Effective supervision in clinical practice settings: A literature review.

- Croskerry, P. From mindless to mindful practice — Cognitive bias and clinical decision daking. The New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 2445–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audétat, M.C.; Laurin, S.; Dory, V.; Charlin, B.; Nendaz, M.R. Diagnosis and management of clinical reasoning difficulties: Part I. Clinical reasoning supervision and educational diagnosis. Medical Teacher 2017, 39, 792–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukut, S.L.; D'Eon, M.; Lawson, J.; Mayer, M.N. Providing comparison normal examples alongside pathologic thoracic radiographic cases can improve veterinary students’ ability to identify abnormal findings or diagnose disease. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 2023, 64, 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A.N.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Practical use of the (Observer)—Reporter—Interpreter—Manager—Expert ((O)RIME) framework in veterinary clinical teaching with a clinical example. Encyclopedia (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 2, 1666–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ander, D.S.; Wallenstein, J.; Abramson, J.L.; Click, L.; Shayne, P. Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator (RIME) descriptive ratings as and evaluation tool in an emergency medicine clerkship. Journal of Emergency Medicine 2012, 43, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.S.B.T. Intuition and reasoning: A Dual-Process perspective. Psychological inquiry 2010, 21, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.B.; Hayes, M.M.; Schwartzstein, R.M. Teaching clinical reasoning and critical thinking: From cognitive theory to practical application. Chest 2020, 158, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S.A. Clinical reasoning and Case-Based Decision Making: The fundamental challenge to veterinary educators. Journal of veterinary medical education 2013, 40, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockcroft, P.D. Clinical reasoning and decision analysis. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 2007, 37, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilminster, S.; Cottrell, D.; Grant, J.; Jolly, B. AMEE Guide No. 27: Effective educational and clinical supervision. Medical Teacher 2007, 29, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Kirkwood, R.; Petrovski, K. Use of effective feedback in veterinary clinical teaching. Encyclopedia (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 3, 928–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.N.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Using the five-microskills method in veterinary medicine clinical teaching. Veterinary Sciences 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, D.P.; London, D.A.; Emke, A.R. Using reflection to influence practice: Student perceptions of daily reflection in clinical education. Perspectives on medical education 2016, 5, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, S.F.; Shepard, K.F.; Harman, L.B.; Stephens, J. Novice and experienced physical therapist clinicians: A comparison of how reflection is used to inform the clinical decision-making process. Physical Therapy 2010, 90, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppen, L.D. Clinical reasoning: Defining it, teaching it, assessing it, studying it. West J Emerg Med 2017, 18, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.N.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. The art and science of consultations in bovine medicine: Use of Modified Calgary – Cambridge Guides, Part 2. Macedonian Veterinary Review 2023, 46, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt-Rawden, S.A.; Chisolm Ms Fau - Anton, B.; Anton B Fau - Flickinger, T.E.; Flickinger, T.E. Teaching empathy to medical students: An updated, systematic review.

- Koufidis, C.; Manninen, K.; Nieminen, J.; Wohlin, M.; Silén, C. Grounding judgement in context: A conceptual learning model of clinical reasoning. Medical education 2020, 54, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, A. Introduction to clinical reasoning. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice 2001, 7, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruczynski, L.I.; van de Pol, M.H.; Schouwenberg, B.J.; Laan, R.F.; Fluit, C.R. Learning clinical reasoning in the workplace: A student perspective. BMC medical education 2022, 22, 19–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurmans, L.; De Coninck, D.; Schoenmakers, B.; de Winter, P.; Toelen, J. Both medical and context elements influence the decision-making processes of pediatricians. Children (Basel) 2022, 9, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeweerd, J.-M. Understanding clinical decision making in small animal practice. Veterinary record 2019, 185, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassirer, J.P. Teaching clinical reasoning: Case-based and coached. Academic medicine 2010, 85, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.N.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Facilitating development of Problem-Solving Skills in veterinary learners with clinical examples. Veterinary Sciences 2022, 9, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, G. Developing teachers of clinical reasoning. The clinical teacher 2013, 10, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustinella, F.; Orlando, P.R.; Colletti, L.A.; Juneja, H.S.; Perkowski, L.C. Remediation strategies and students' clinical performance. Medical teacher 2004, 26, 664–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croskerry, P. Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decisionmaking. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2003, 41, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; Cutrer, W.; Reimschisel, T.; Gigante, J. You too can teach clinical reasoning. Pediatrics (Evanston) 2012, 130, 795–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audétat, M.-C.; Laurin, S.; Sanche, G.; Béïque, C.; Fon, N.C.; Blais, J.-G.; Charlin, B. Clinical reasoning difficulties: A taxonomy for clinical teachers. Medical teacher 2013, 35, e984–e989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.; Bartlett, M.; Gay, S.; Hammond, A.; Lillicrap, M.; Matthan, J.; Singh, M. Consensus statement on the content of clinical reasoning curricula in undergraduate medical education. Medical Teacher 2021, 43, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, S.S.C.d.; Corrêa, C.G.; Silva, R.d.C.G.E.; Cruz, D.d.A.M.L.d. Clinical reasoning in undergraduate nursing education: A scoping review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da U S P 2015, 49, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godager, L.H.; Abrahamsen, I.; Liland, M.C.; Torgersen, A.E.; Rørtveit, R. Case-Based E-Learning Tool Affects Self-Confidence in Clinical Reasoning Skills among Veterinary Students—A Survey at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 2024, e20230147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Silano, V.; Ramacciati, N.; Prandi, C.; Baldon, A.; Bianchi, M. Teaching strategies of clinical reasoning in advanced nursing clinical practice: A scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract 2023, 67, 103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, Y.; Ishiguro, N.; Suganuma, T.; Nishikawa, T.; Takubo, T.; Kojimahara, N.; Yago, R.; Nunoda, S.; Sugihara, S.; Yoshioka, T. Team-Based Learning, a learning strategy for clinical reasoning, in students with Problem-Based Learning tutorial experiences. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine 2012, 227, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauldin Pereira, M.; Artemiou, E.; Conan, A.; Köster, L.; Cruz-Martinez, L. Case-based studies and clinical reasoning development: Teaching opportunities and pitfalls for first year veterinary students. Medical science educator 2018, 28, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, S.; Hemmati, P.; Shirazi-Beheshtiha, S.H.; Aslani, F.; Taghdiri, M.R.; Abadiyeh, R.; Tsai, T.-C. Developing a clinical presentation curriculum in veterinary education: A cognitive perspective. Comparative clinical pathology 2012, 21, 1521–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.S. Increased student self-confidence in clinical reasoning skills associated with Case-Based Learning (CBL). Journal of veterinary medical education 2006, 33, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtman, N.; Beck, C.; Boller, E. Promoting clinical reasoning with a Clinical Integrative Puzzle – The experience of the University of Melbourne. Journal of comparative pathology 2016, 154, 82–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubarsky, S.; Dory, V.; Audétat, M.C.; Custers, E.; Charlin, B. Using script theory to cultivate illness script formation and clinical reasoning in health professions education. Can Med Educ J 2015, 6, e61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A. Concept-Based learning in clinical experiences: Bringing theory to clinical education for deep learning. The Journal of nursing education 2016, 55, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noushad, B.; Van Gerven, P.W.M.; de Bruin, A.B.H. Twelve tips for applying the think-aloud method to capture cognitive processes. Medical Teacher 2024, 46, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verillaud, B.; Veleur, M.; Kania, R.; Zagury-Orly, I.; Fernandez, N.; Charlin, B. Using learning-by-concordance to develop reasoning in epistaxis management with online feedback: A pilot study. Science Progress 2024, 107, 00368504241274583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, O.R. Brain, mind, and the organization of knowledge for effective recall and application. Learning Landscapes 2011, 5, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.; Pinto-Powell, R. Introductory clinical reasoning curriculum. MedEdPORTAL 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, D.; German, D.; Daley, B.; Taylor, D. Concept mapping: An aid to teaching and learning: AMEE Guide No. 157. Medical teacher 2023, 45, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinten, C.E.K.; Cobb, K.A.; Freeman, S.L.; Mossop, L.H. An investigation into the clinical reasoning development of veterinary students. Journal of veterinary medical education 2016, 43, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, J.; Mamede, S.; van den Berg, P.; Zwaan, L.; van Peet, P.; Bindels, P.; van Gog, T. Learning deliberate reflection in medical diagnosis: Does learning-by-teaching help? Advances in Health Sciences Education 2023, 28, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, L.; Mena-Rodríguez, E.; Rubio, L. Basic skills in higher education: An analysis of attributed importance. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Tsai, T.C. Learning clinical reasoning with virtual patients. Medical education 2020, 54, 481–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abani, S.; De Decker, S.; Tipold, A.; Nessler, J.N.; Volk, H.A. Can ChatGPT diagnose my collapsing dog? Frontiers in veterinary science 2023, 10, 1245168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid-García, A.; Rosales-Rosado, Z.; Freites-Nuñez, D.; Pérez-Sancristóbal, I.; Pato-Cour, E.; Plasencia-Rodríguez, C.; Cabeza-Osorio, L.; Abasolo-Alcázar, L.; León-Mateos, L.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, B. Harnessing ChatGPT and GPT-4 for evaluating the rheumatology questions of the Spanish access exam to specialized medical training. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 22129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockcroft, P.D. Diagnosis and clinical reasoning in cattle practice. In Bovine medicine, , Cockcroft, P.D., Ed., 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.-Y.; Fogelberg, K. Understanding implicit bias and its impact in veterinary medicine. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 2024, 54, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinten, C.E.K. Clinical reasoning in veterinary practice. Veterinary evidence 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.N.M.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Petrovski, K.R. Effective veterinary clinical teaching in a variety of teaching settings. Veterinary sciences 2022, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, N.; Bernier, C.; Houde, S.; Xhignesse, M. Teaching and learning clinical reasoning: A teacher's toolbox to meet different learning needs. British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005) 2020, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development; FT press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Linn, A.; Khaw, C.; Kildea, H.; Tonkin, A. Clinical reasoning: A guide to improving teaching and practice. Australian Family Physician 2012, 41, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ludders, J.W.; McMillan, M. Errors of clinical reasoning and decision-making in veterinary anesthesia. In Errors in veterinary anesthesia; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.C.M.; Hamdy, H. Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Medical Teacher 2013, 35, e1561–e1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovski, K.R.; McArthur, M. The art and science of consultations in bovine medicine: Use of modified Calgary–Cambridge guides. Macedonian Veterinary Review 2015, 38, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munby, H. Reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Current Issues in Education 1989, 9, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Client ± patient-related | Cognition-related | Process-related | System-related |

| Challenging learners/practitioner’s credentials [17,33,34] Client’s ± patient’s characteristics [4,17,18,34,35,36,37,38] Client’s wish/es and perceptions [34,38,39] Incorrect hypothesis suggestions [17,33,39,40] Language and vocabulary [17] Understanding of the problem [34,40] |

Awareness of common clinical reasoning biases, difficulties, or errors [9,10,14,15,18,19,31,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] Awareness of bias, difficulty, or error in clinical reasoning remediation strategies [9,10,14,15,18,19,31,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] Breadth and depth of veterinary medical cognition [10,30,52,53] Expertise / Level of development [7,17,19,53,54] Metacognitive competences Organization of mental representation [14,55] Personal attitude (e.g., beliefs, confidence, contemplation, creativity, curiosity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, motivation, open-mindedness, perseverance, prejudices, and values) [2,4,34,36,38,56,57] Personal psychomotor state (e.g., fatigue, sleep deprivation, and stress) [2,4,17,18,34,35,40,51,57,58,59] |

Available versus required time for the encounter [2,4,17,18,57] Depth and level of supervision [50,51,60] Error-management Individual versus teamwork Method of clinical teaching [31,50,61,62] Reflection [14,63,64] |

Available resources [2,17,18,35,39] Available versus required time for the encounter [2,4,17,18,57] Client-learner/practitioner relationship [33,34,38,40] Clinical encounter (e.g., urgency) [34,35] Clinical settings [35,36,39,65] Communication skills [33,34,39,40,42,66,67] Cultural environment [39] Distractors (e.g., noise) [4,35,57] Environment [34,57] Ethical issues [35,39] Financial constraints [2,39] Frequency of encounter Group/Team size Industry-related factors and issues [39] Legal factors and issues [39] Level of complexity Level of supervision [50,60,62] Social environment [1,2,5,17,18,58,64,68,69,70,71,72] Support from the team [18,50] Team dynamics [57] |

| Stage | Activity / Element | Example of veterinary medical learner’s synthesis of information |

| 1. Consider the client ± patient situation |

NA | Mr Jo Block is an inexperienced dairy manager and has presented Friday, a 6-year-old Jersey cow with ‘something hanging out from the back quarters’. The hanging bit is big like a sac with many lumps on it. Friday is lying down and is non-responsive to stimuli. She calved overnight with no assistance and has a live, healthy female calf. |

| 2. Collect data | Presenting problem | A sac-like, large tissue with many lamps protruding from the tail end. NOTE: The presenting problem should raise suspicion of uterine prolapse that requires to be treated as an emergency. |

| Health interview | Friday is a home-bred cow. The enterprise has a record of milk fever at the previous two calvings in Friday’s life. No other health issues have been recorded for Friday. The current milking herd consists of approximately 350 milking and 50 dry cows, in addition to 40 pregnant heifers and 2 bulls. The entire population is purebred Jersey. Cows are milked twice daily through a rotary milking shed with 46 units. Calving started 6 weeks ago and should finish in an additional 3 weeks. The entire population is on pure (Ryegrass-Clover mixture) pasture and no nutritional supplements are provided. Nitrogen fertilizer was applied some 4 weeks ago (in the middle of the ‘first rotation’), and regular effluent spraying occurs in the paddocks close to the milking shed. As the weather has been ‘playing up’, for the last night's pasture availability, Mr Jo Block has put the ‘springers’ (cows showing signs of impending calving) and freshly calved cows in the paddock just next to the milking shed. As this encounter is presented late in the calving, the usual management in this enterprise is to keep the ‘springers’ and the freshly calved cows altogether. The weather has been cold over the last few days, in addition to some rain. The previous night was very cold and overcast. |

|

| Various examination steps | Environment and husbandry – no abnormalities detected (NAD), except for the cold weather and the use of an effluent spayed paddock for overnight grazing. Friday’s clinical examination findings General inspection: Severe obtundancy (nearly comatose). Sternal recumbency with head tucked in the left paralumbal fossa. Cardinal signs: Mild tachycardia and muffling of heart sounds. Mildly subnormal body temperature and respiratory rate. Absence of rumen contractions. Very mild bloat. Tail end exam findings - Prolapsed tissues, resembling the uterus, with very little contamination on it. On palpation, it seemed very soft and easy to manipulate. No signs of recent defecation or urination. Remaining of the clinical examination - NAD. |

|

| Ancillary examination techniques/tests | Pre-treatment collection of blood samples. Significant findings in blood biochemistry carried out in a portable analyzer – Calcium 1.40 mmol/L (Normal range 2.40 – 3.10 mmol/L), and Magnesium 0.40 mmol/L (Normal range 0.75 – 0.95 mmol/L) |

|

| 3. Analyze the data and 4. Identify problem/s ± Issue/s |

Review data / Problem representation | Mr Block is an inexperienced dairy manager and has presented Friday, a 6-year-old Jersey cow, with peracute protruding tissues from the tail end, resembling a freshly prolapsed uterus, detected soon after calving. Friday is in a sternal recumbency and obtunded. She suffers from hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia. |

| Review context | Mr. Block mentioned that Friday must be saved. The client is concerned about Friday’s welfare and survival as this may affect his employment. | |

| Problem identification | Protruding tissue from the tail end, resembles the uterus. Soft and easily manipulated. Exposure to effluent-sprayed paddocks. Unfavorable weather. Sternal recumbency with head tucked in left paralumbal fossa. Significant obtundancy. Mild tachycardia. Mild subnormal body temperature and respiratory rate. Muffled heart sounds. Suspected constipation. Mild bloat. Hypocalcemia. Hypomagnesemia. |

|

| Recall knowledge | The initial hypothesis should be that Friday has been presented with uterine prolapse. Uterine prolapse is commonly associated with hypocalcemia which, in turn, is frequently preceded by hypomagnesemia (Figure S1). | |

| Interpretation | ‘The large sac with multiple lumps on it is the uterus that has come out through the open cervix very soon after Friday’s calving.’ | |

| Discrimination | ‘The sac hanging out is not small and smooth. Hence, vaginal prolapse can be ruled out.’ | |

| Relating | ‘Friday has something hanging out from the hid quarters and she is very sleepy, being not aware of what is happening around her.’ | |

| Inferring | ‘Friday’s uterus hanging out from the hid quarters is likely associated with the milk fever. Based on the previous experience of milk fever and the blood results she suffers from a milk fever. The milk fever is most likely associated with the lack of magnesium in her diet and grazing in the effluent paddock. The history of milk fever, lack of magnesium in the diet, and excess potassium in the effluent paddock, all increase the risk of milk fever recurring. This has resulted in an imbalance of magnesium and calcium in her blood.’ | |

| Matching | ‘Uterine prolapse occurs soon after calving.’ | |

| Predicting | ‘As you called early, and the uterus is not contaminated, we should be able to easily return it in place. Then, we should be able to treat her imbalances and save Friday.’ | |

| 5. Establish mutually agreed goals | NA | Mr. Block wants Friday to be saved. Otherwise, the owner may be very upset. The best possible outcome would be Friday surviving and returning to milk. The client should be advised to ensure effluent paddocks are not used for grazing of ‘springers’ and freshly calved cows. Hypomagnesemia and hypocalcemia are unlikely to be sporadic problems. Rather, they are usually population-level problems. This may need to be discussed with the client, and preventative strategies may be proposed. Yet, the client is not the decision-maker, and a follow-up may be required with the owner of the enterprise. |

| 6. Take action | NA | In this encounter, the primary hypomagnesaemia has resulted in hypocalcemia. The hypocalcemia has been a contributing factor to the occurrence of the uterine prolapse. Therefore, the management plan should consider all three conditions. The initial decision should be which of the three conditions to treat the first. The order of occurrence of the problem is most likely hypomagnesemia → hypocalcemia → uterine prolapse. Logically, the treatment should address the problem in the same order. Yet, the risk of loss of life with the current clinical presentation is highest with uterine prolapse, followed by hypocalcemia, and the least with hypomagnesemia. This should be considered, coupled with the effect of treatment on the ease of management of each condition. Hypomagnesemia is usually self-corrected with the correction of hypocalcemia and the return of the function of the alimentary system. Yet, Friday is in deep hypomagnesemia, and supportive treatment should be considered. She is currently in stage 2 of hypocalcemia. Hence, she has a few hours left before her life is in danger (in stage 3 of hypocalcemia; Figure S2). Calcium is essential for the uterus to contract. Currently, the uterus is soft and easily manipulated. Therefore, in this encounter, initially, the uterus should be repositioned, followed by treatment of hypocalcemia, and the last should be the attempt to treat the hypomagnesemia. |

| 7. Evaluate the outcome |

NA | Friday’s conditions should be treatable in a very short time (by 2 hours after intervention all conditions should be resolved). As hypocalcemia may recur, a depot of calcium should be provided, until the kidneys’ response is evident in 2 – 3 days (Figure S1). The client should be made aware to monitor for relapse of any of the conditions, in addition to monitoring for signs of metritis. |

| 8. Reflection and new learning |

NA | The knowledge of the pathophysiology and risk factors associated with prolapsed uterus should facilitate reflection on which of these apply to this case. The management should facilitate reflection on the decision of which condition to treat first. |

| Type of strategy | Proven methodologies | Examples | |

| Cognitive forcing strategies [12,30,48,77,80,81,82] | Case/Problem – based discussions [4,8,18,20,23,37,45,58,80,81,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] |

Based on ‘real life’ encounters Compare and contrast Consideration of alternatives Effective feedback Group work Justifying Repetitive practice Safe environment |

Models of clinical teaching Multiple encounters with variable content and context Self-explanation Serial-cue approach (hypothesis-driven data collection) Team-based learning ‘Think aloud’ |

| Developing medical understanding [5,18,37,43,48,80,91,92] | Anatomical approach (e.g., what part of the abdominal wall) Compare and contrast Illness scripts Management approach/Problem/Sign/Syndrome-based approach Pathophysiological approach (e.g., hypoproteinaemia) Safe environment Scaffolding Semantic qualifiers |

Models of clinical teaching Mnemonics Self-explanation ‘Think aloud’ |

|

| Developing retrieval practices [1,5,37,45,48,80,81,83,91,93] | ‘Ask rather than answer’ Compare and contrast Consideration of alternatives Developing ‘casual networks’ Justifying Lists’ creation Slow down Stimulated recall |

Debrief Flipped classroom Mind-mapping Models of clinical teaching Simulations ‘Think aloud’ Written format (e.g., Extended matching MCQ) |

|

| Facilitating the organization of mental representation [5,18,37,55,80,89,91,92,94,95] | Concept-based learning Concept/Mind mapping Decision-trees Group work Safe environment |

Serial-cue approach (hypothesis-driven data collection) Team-based learning ‘Think aloud’ |

|

| Simulated clinical encounters [1,19,37,45,48,82,91,92,96] | Based on ‘real life’ encounters Compare and contrast Consideration of alternatives Effective feedback Group work Justifying Safe environment |

Models of clinical teaching Multiple encounters with variable content and context Team-based learning ‘Think aloud’ |

|

| Standardized client ± patient [20,37,83] | Compare and contrast Consideration of alternatives Effective feedback Group work Justifying Repetitive practice Safe environment |

Models of clinical teaching Multiple encounters with variable content and context Team-based learning |

|

| Differential teaching considers the learner’s level/practitioner’s expertise [7,37,80,91,94,97] | Early learners: Low complexity; Traditional in early stages with progressively increasing complexity as learners advance; In a safe learning environment | Rudimentary compare and contrast Multiple encounters with variable content and context Problem representation ‘Think aloud’ Traditional teaching is followed by work-based learning as learners advance, starting in a safe environment and transitioning to work-based learning |

|

| Advanced learners: Higher complexity; Preferably in a work-based learning environment | Advanced compare and contrast Deliberate reflection Exemplars Illness scripts Models of clinical teaching Multiple encounters with variable content and context Semantic qualifiers Serial-cue approach (hypothesis-driven data collection) Slow down Team-based learning ‘Think aloud’ |

||

| Structured reflection [6,12,20,30,37,45,48,80,81] | Consideration of alternatives Evidence-based principles of veterinary medicine Distinct and eliminating features of the hypotheses Factors affecting clinical reasoning How / What / When / Who / Why Improvements and refinements Starting in a safe environment and transitioning to work-based learning |

Debrief Models of clinical teaching Written format (e.g., information technology/journal/portfolio) |

|

| Work-based learning [12,18,20,45,48,55,64,89,98] | ‘Real-life’ experience | Checklists Cognitive forcing strategies Guided reflection Instructions at assessment Models of clinical teaching Multiple encounters with a variety of clients ± patients Team-based learning |

|

| Bias | Description | Remediation strategy |

| Affect heuristic [2] |

Relying on emotion rather than considering objective information and/or contextual circumstance | Effective feedback; Refer to applicable collected data/context |

| Anchoring heuristic [5,30,40,49,58,69,77,78] |

Fixation on a single, early or first impression of the encounter, ignoring new information as it becomes available | Assess the reason for non-response to the management approach; Effective feedback; Explicit acknowledgement of uncertainty; Gamification; Refer to applicable collected data/context, and particularly information that is rejecting the first impression; Slowing down; Use of an objective source for the list of diagnoses/management approaches to compare to the completeness of the primary list |

| Availability [5,16,29,30,49,58,69] |

Referring to what comes to mind most easily, usually a recently seen encounter with similar collected data/context | Effective feedback; Gamification; Refer to baseline prevalence or probability of the suspected diagnosis/management approach; Use of an objective source for the list of diagnoses/management approaches to compare to the completeness of the primary list |

| Base rate neglect [16] |

Disproportionately ignoring the general probability of a diagnosis/management approach and focusing on specific information only | Effective feedback; Gamification; Refer to baseline prevalence or probability of the suspected diagnosis/management approach |

| Confirmation [12,29,58,77,78,104] |

Disproportionately accepting information that confirms or supports the initial hypothesis | Effective feedback; Use of an objective source for the list of diagnoses/management approaches to compare to the completeness of the primary list |

| Framing [16,29] |

Collecting information that supports a diagnosis/management strategy | Effective feedback; Refer to applicable collected data/context; Use of an objective source of list of diagnoses/management approaches; |

| Fundamental attribution | Attributing behavior to an intrinsic characteristic rather than external factors | Effective feedback; Use of an objective source for the list of diagnoses/management approaches to compare to the completeness of the primary list |

| Overconfidence [16,19,29] |

Belief that the level of knowledge is higher than the actual cognitive level. | Assess the reason for non-response to the management approach; Effective feedback; Explicit acknowledgement of uncertainty; Use of an objective source of list of diagnoses/management approaches; Slowing down |

| Premature closure [10,12,29,49,58,78,104] Probably the most common type of error [10,11,29] |

Acceptance of a single diagnosis/management approach before it has been fully verified (usually intuitive clinical reasoning type) | Effective feedback; Refer to applicable collected data/context; Slow down; Use of an objective source for the list of diagnoses/management approaches to compare to the completeness of the primary list |

| Representativeness heuristics [5,16,58,69,77] |

Disproportionately accepting signs and syndromes indicative of a single hypothesis, neglecting prevalence/probability and atypical encounters | Effective feedback; Gamification; Use of an objective source for the list of diagnoses/management approaches to compare to the completeness of the primary list |

| Scarcity heuristic [29] |

Disproportionately accepting signs and syndromes indicative of a rare prevalence (e.g., exotic disorders) / probability and/or atypical presentation of an encounters | Effective feedback; Gamification; Refer to baseline prevalence/probability or typical presentation of the suspected diagnosis/management approach |

| Survival | Assign excessive weight to data or events that have survived for some time | Effective feedback; Use of an objective source for the list of diagnoses/management approaches to compare to the completeness of the primary list |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).