1. Introduction

Internal Schlemm’s canal opening surgery is a type of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) increasingly used to treat mild to moderate glaucoma.

Various devices, including Trabectome[

1],Kahook dual blade (KDB)[

2], Tanito microhook (TMH) [

3], T-hook [

4], Gonioscopy-Assisted Transluminal Trabeculotomy (GATT) [

5] have been developed and are now widely applied in clinical practice.

The surgical outcomes of these devices are generally similar, often resulting in postoperative intraocular pressures (IOP) in high teens [

6].

Several factors, such as pre-operative IOP, exfoliation glaucoma (EXG), IOP spikes, a history of selective laser trabeculoplasty or argon laser trabeculoplasty, younger age, high central corneal thickness, myopia, male gender, and Black ethnicity may influence postoperative IOP[

7].

In addition to these factors, our clinical observations suggest that the IOP reduction after surgery is poor in diabetic patients.

To investigate the potential effects of diabetes mellitus (DM) on the surgical outcomes of Schlemm’s canal-based MIGS, we conducted a retrospective study on 232 patients who underwent combined cataract surgery and internal trabeculotomy at Sensho-kai eye institute.

2. Materials and Methods

Inclusion criteria were patients with cataracts and mild to moderate primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) or ocular hypertension (OH) who were indicated for combined cataract surgery and minimally invasive Schlemm’s canal opening surgery (PI+SCO MIGS) due to poor visual acuity or inadequate IOP control despite the use of topical medications. Exclusion criteria included EXG, angle closure glaucoma (ACG), uveitic glaucoma, pigmentary glaucoma, and patients with poor compliance or incomplete data.

When eye with glaucomatous optic neuropathy (GON: characterized by retinal nerve fiber layer defects and glaucomatous optic disc cupping) or glaucomatous retinal nerve fiber layer defects had Shaffer grade of 2 or narrower angles on gonioscopy or an angle opening distance at 500µm less than 0.2 mm as measured by anterior segment OCT (CASIA II, Tomey, Aichi), the eyes were diagnosed with chronic angle-closure glaucoma and excluded from this study. Between November 2016 and January 2024, 232 eyes underwent PI+SCO MIGS at Sensho-kai Eye Institute and were followed for more than 6 months. The surgeries included 81 eyes with KDB, 84 eyes with TMH, and 67 eyes with T-Hook. Among these, 24 eyes with EXG, 30 eyes with chronic ACG, 9 eyes with uveitic glaucoma, 1 eye with pigmentary glaucoma and 1 eye from a patient with poor compliance were excluded. Of the remaining 167 eyes, 58 patients had bilateral surgeries, and data from their left eyes were excluded. Finally, 109 eyes of 109 patients were enrolled in this study.

Primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) was defined as the presence of an open angle and GON, and glaucomatous abnormality detected using optical coherence tomography (OCT; AngioVue, RTVue XR; Optovue, Fremont, CA, USA). Visual field defects were evaluated with a Humphrey Field Analyzer (750i; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Tokyo, Japan). Ocular hypertension (OH) was defined as having an open angle and a history of high IOP exceeding 21 mmHg on at least two occasions, without glaucomatous visual field defects (normal glaucoma hemifield test and pattern standard deviation within 95% of normal on the Humphrey Field Analyzer) or glaucomatous optic neuropathy.

DM was diagnosed based on criteria established by the Japan Association for Diabetes Education and Care, defined as a fasted blood sugar level≥126mg/dl and/or HbA1C≥6.5%.

The surgeries were performed by two of the authors (EC, TC). The surgical procedures have been reported previously [

6]. Briefly, after the injection of viscoelastic material and anterior capsulorhexis, the internal trabeculotomy devices (KDB, TMH, and T-Hook) were inserted through a clear corneal opening at the 10 o’clock position, and the trabecular meshwork was incised over 120–150 degrees using a double-mirror Ahmed surgical goniolens (UADVX-H; Ocular). Following internal trabeculotomy, phacoemulsification, aspiration, and intraocular lens implantation were performed. After completion of cataract surgery, a 0.25% acetylcholine solution was injected into the anterior chamber (AC), and the corneal wound was closed with a single 10-0 nylon suture. Antiglaucoma medications were administered if postsurgical IOP were elevated. Postoperatively, gatifloxacin, 0.1% betamethasone, and 2% pilocarpine eye drops 4 times per day were used for 2–4 weeks.

Postsurgical bleeding into the anterior chamber in these patients was classified using the Shimane University grading system, which categorizes hyphema severity into 4 levels: L0 no hyphema, L1 layered bleeding <1mm, L2 layered bleeding ≥ 1mm but not exceed the pupillary margin, L3 layered bleeding exceeding the inferior pupillary margin.

Blood clot (C) is categorized as C0 indicating no blood clots in the anterior chamber (AC) and 1 the presence of blood clots. Floating red blood cells (R) are categorized as R0 indicating no floating RBCs in the AC, R1 floating RBCs with clearly visible iris patterns in the entire AC, R2 floating RBCs partially obscured iris patterns; R3 dense floating RBCs with completely obscured iris patterns. [

8]

In this study, pre-operative IOP was defined as the highest IOP measured under medication within three months prior to surgery. In contrast, the pre-operative 3-mean IOP was defined as the average of IOP measurements recorded immediately before surgery under medications.

Informed consent and approval by Internal Review Board: This study design was approved by internal review board at Sensho-kai (Head H Amano). Informed consent for surgery and approval of patients to use the data for clinical study were obtained from each patient before surgery. The study design adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis: we used analysis of variance (ANOVA), Wilcoxon signed rank test, chi square test, Kaplan-Meier life table analysis, Haberman’s residual analysis, multivariate linear mixed model, and multiple regression all packaged in Bell Curve for Excel (Social Survey Research Information Co, Tokyo)

3. Results

The mean follow-up period was 35.3±24.8 months (range 6.0-94.2 months).

Demographic data is presented in

Table 1. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the diabetic and non-diabetic cohorts, including pre-surgical IOP (highest IOP within 3 months prior to MIGS surgery), logMAR best corrected visual acuity, refractive error, mean deviation on Humphrey visual field analysis, extent of canal opening, and follow-up duration (

Table 1).

3.1. Post-Operative Course of IOP and Medications After Canal Opening MIGS.

Post-surgical IOP significantly decreased in both the diabetic and non-diabetic cohort as determined by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P<0.01). However, the diabetic cohort exhibited significantly higher post-surgical IOP compared to non-diabetic cohort between three months (P=0.001) and two years (P=0.019) after surgery (

Table 2).

Regarding post-surgical medications, the number of medications decreased significantly in both the DM (P=0.03 to <0.001 for 3 years) and non-DM cohorts (P=0.03 to <0.001 for 5 years; signed-rank test), with no significant difference observed between the two groups (

Table 3).

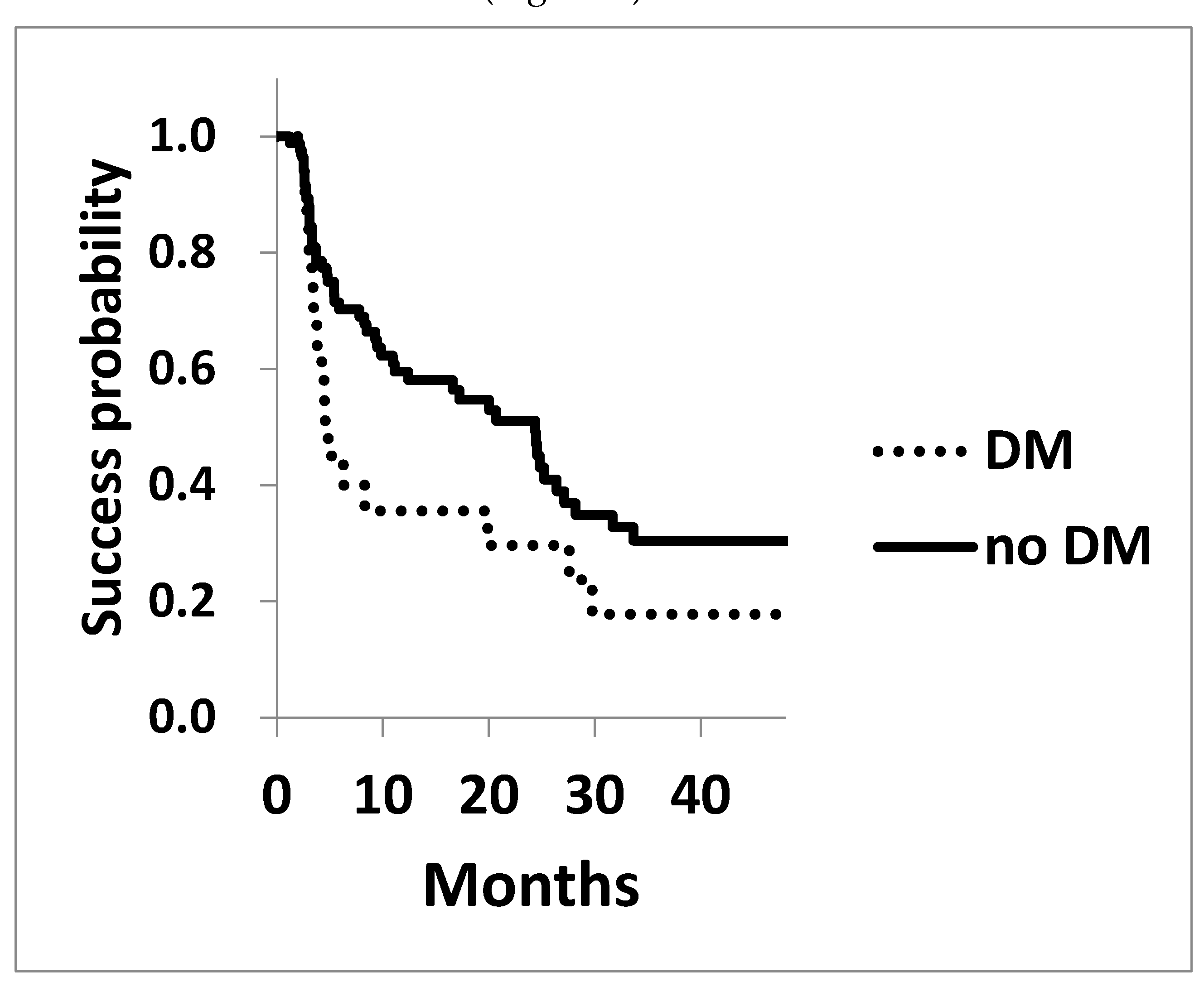

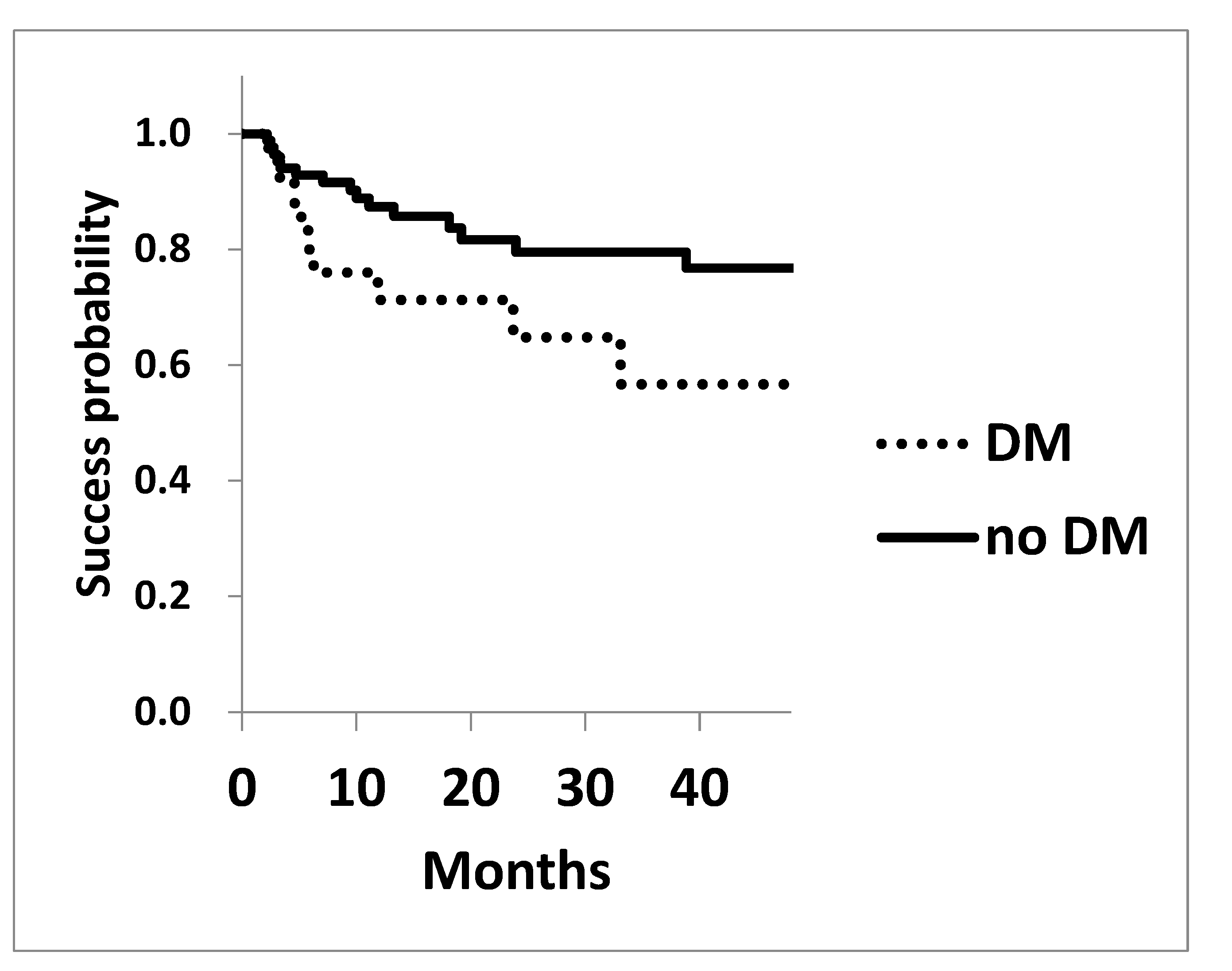

The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for achieving post-surgical IOP of 15 mmHg and 18 mmHg is shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. The survival probability to achieve 15 mmHg at three years in diabetic patients was 17.8±0.09, significantly lower compared to that of the non-diabetic cohorts of 30.4±0.06 (P=0.042 Log rank test,

Figure 1). Similarly, the probability of achieving 18 mmHg at three years in DM and non-diabetic cohorts were 56.7±0.12 and 79.5±0.05 (P=0.065), respectively, showing a trend toward worse outcomes in diabetic cohort (

Figure 2).

Legend for

Figure 1: The survival probability of achieving a target of 15 mmHg assessed using Kaplan-Meier life table analysis, was significantly lower in the diabetic cohort (P=0.042).

Legend for

Figure 2: The survival probability of achieving a target IOP of 18 mmHg was assessed using Kaplan-Meier life table analysis. The success probability was marginally lower in the diabetic cohort P=0.065.

3.2. Post-Operative Intra-Cameral Bleedings

Regarding post-surgical intracameral bleeding, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of hyphema (L), clot formation (C), or bleeding density (R) between the groups. (

Table 4)

3.3. Results of Multivariate Analysis

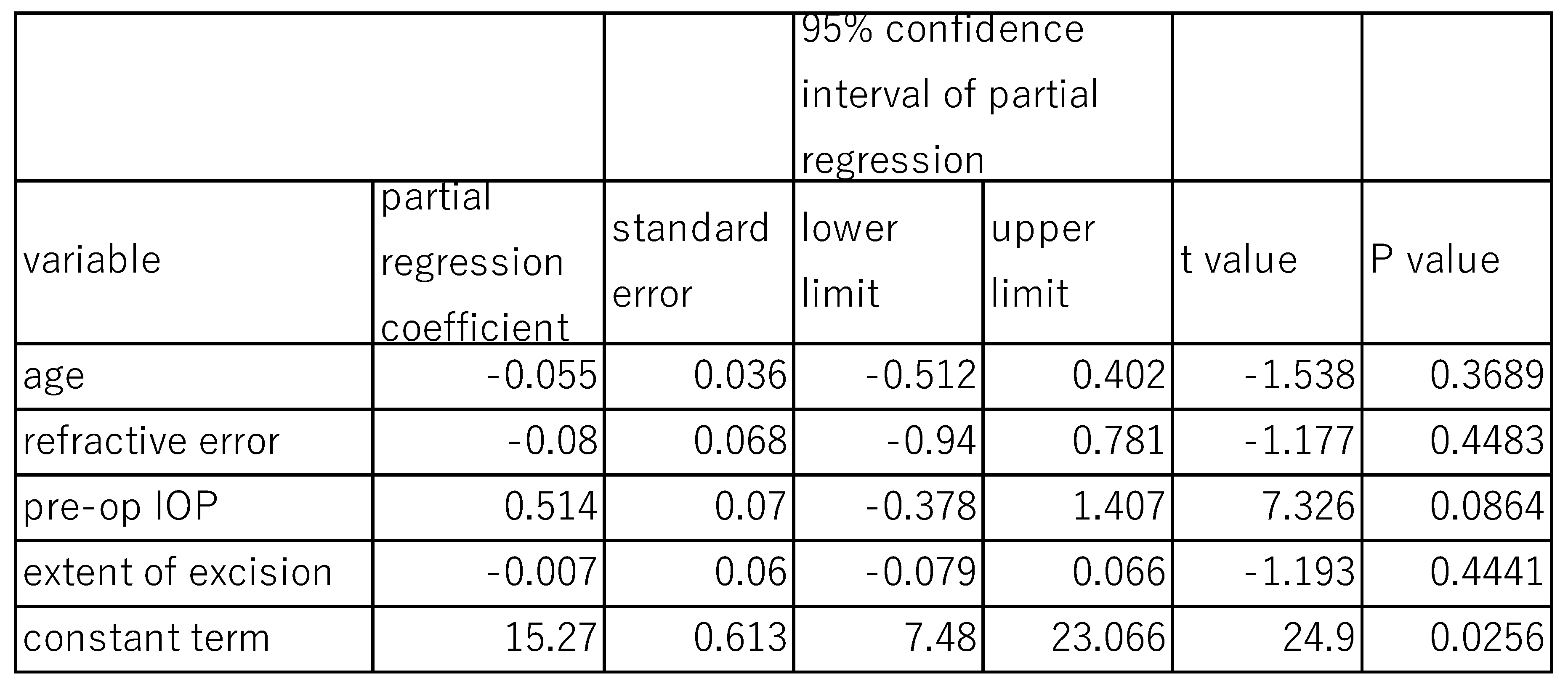

The effects of DM on post-surgical IOP at 12 months were analyzed using a multivariate Linear mixed model (

Table 5). The fixed effects of variables such as age (P=0.369), refractive error (P=0.448), extent of canal opening (P=0.444) were not statistically significant, indicating no significant association between these three variables and post-surgical IOP. The fixed effects of pre-surgical IOP (P=0.086) were marginal. However, the random effect of DM on 12-month post-surgical IOP was statistically significant (P<0.001), with a standard deviation of 0.777, a variance component 0.604, and a chi square value of 12.33 (

Table 5), suggesting that DM contribute to variability in post-surgical IOP outcomes.

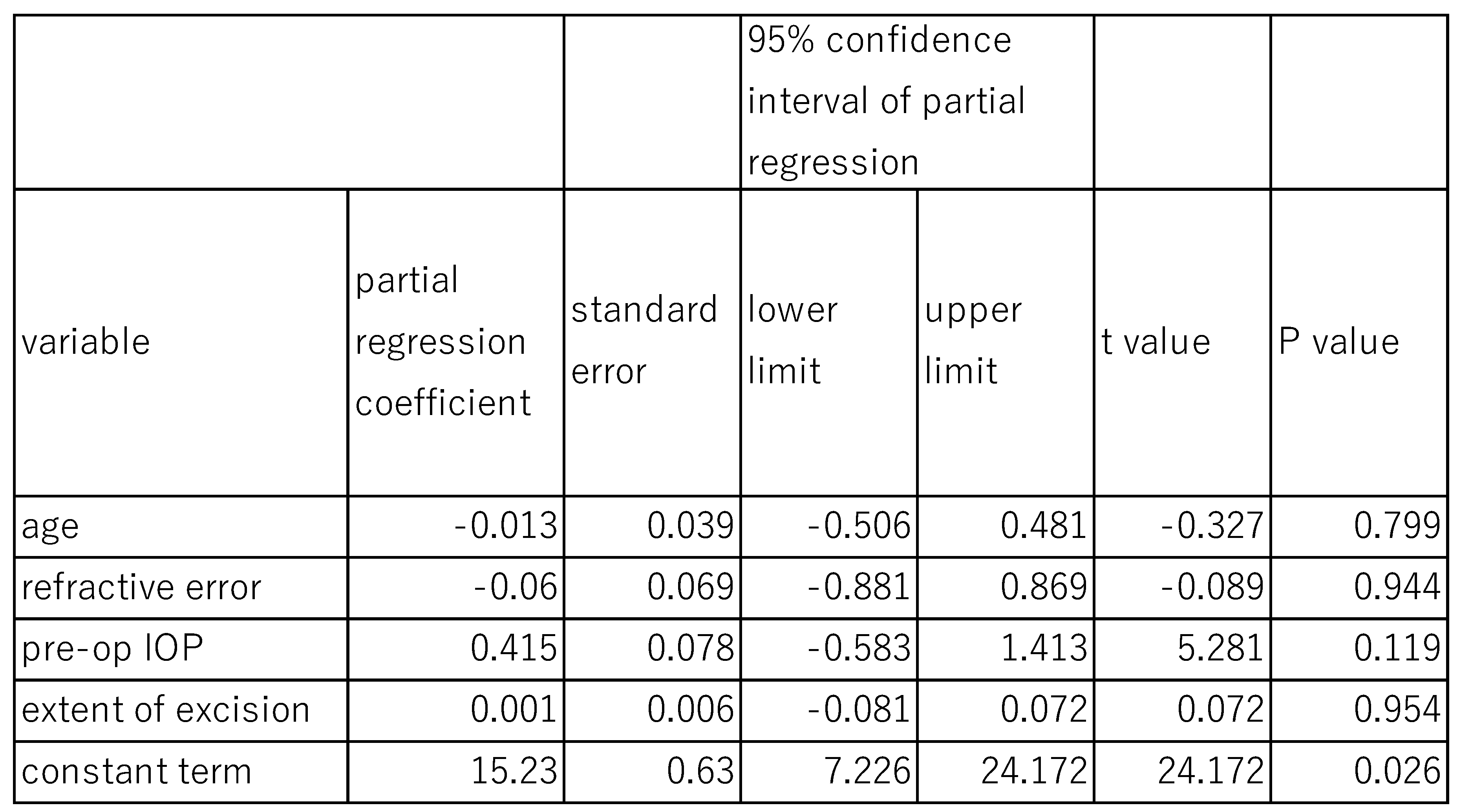

Similarly, when the effects of DM on post-surgical IOP at 6 months were assessed using the same model (

Table 6). The fixed effects of age (P=0.799), refractive error (P=0.943), pre-operative IOP (P=0.119), and extent of canal opening (P=0.954) were not statistically significant. However, the random effect of DM on post-surgical IOP at 6 months was statistically significant (P<0.001), with a standard deviation of 0.787, a variance component of 0,619, and chi square value of 11.06 (

Table 6).

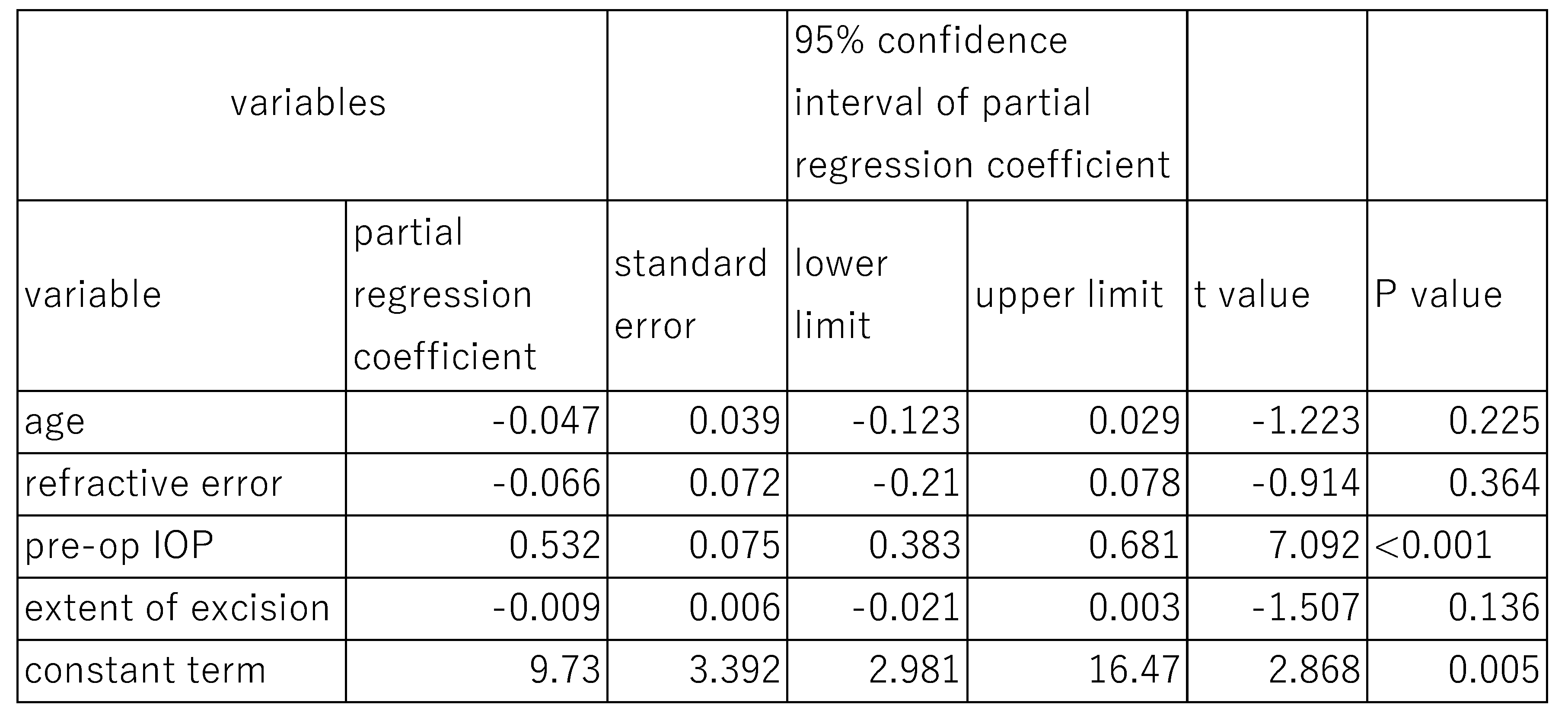

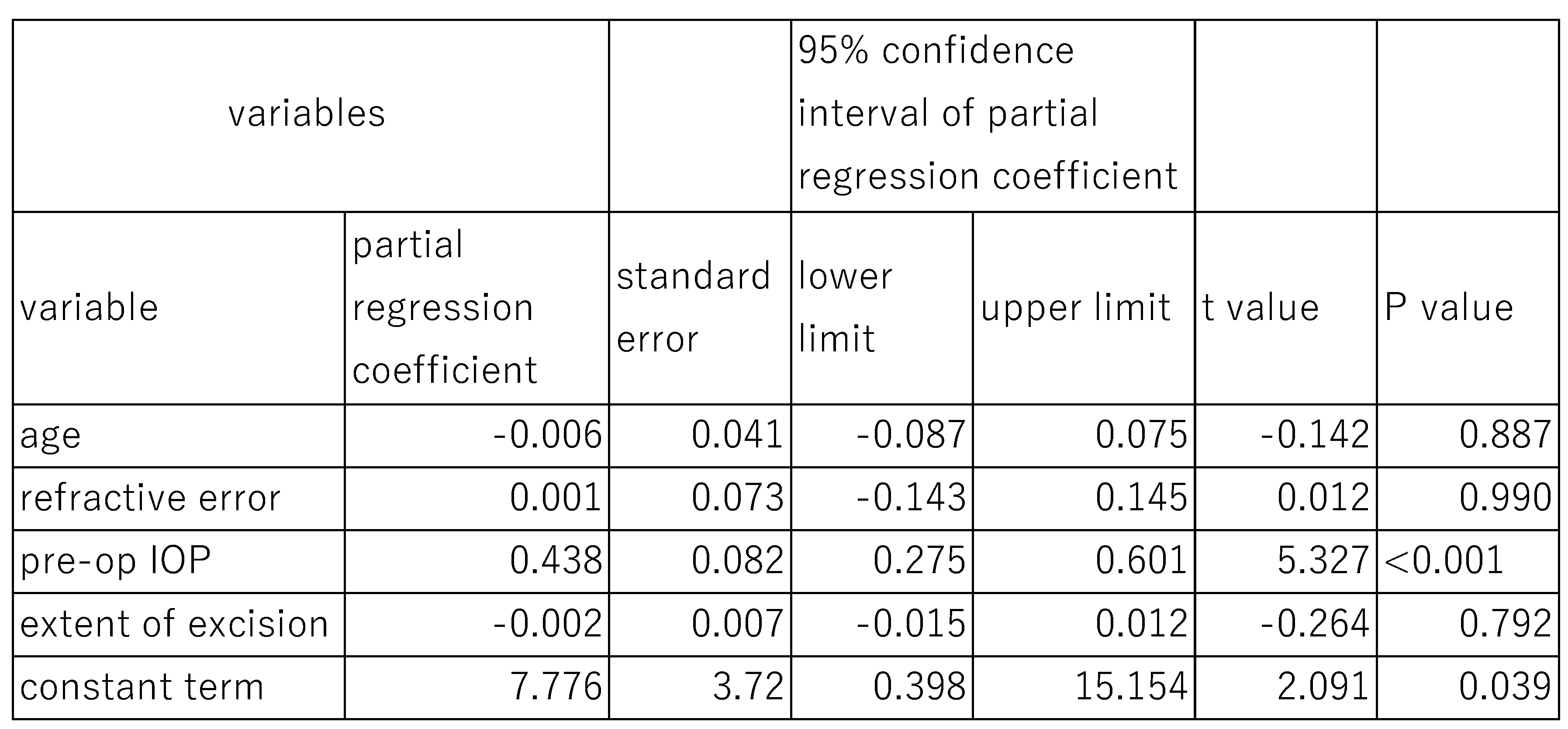

In another study, the associations between numerical variables and post-surgical IOP excluding the effects of DM, were assessed using multiple regression analysis (

Table 7 and

Table 8).

In this case, preoperative IOP was significantly associated with post-surgical IOP at both 6 months (P<0.001) and 12 months (P<0.001). However, other parameters such as age, refractive error, and extent of canal opening showed no significant association with post-surgical IOP at either time point.

4. Discussion

To the best of the author’s knowledge, there are no studies investigating the relationship between canal-based MIGS and diabetes. However, there are several studies suggesting that diabetes mellitus (DM) negatively affects the outcomes of trabeculectomy and SLT[

9,

10,

11].

The underlying reasons for poorer surgical outcomes with diabetes remain unclear. The possibility that the extent of postoperative intraocular bleeding influences postoperative intraocular pressure is considered low because there were no observed differences in post-surgical hyphema or clot formation between diabetic and non-diabetic patients (

Table 4).

In diabetic patients, post-surgical inflammation tends to be pronounced, while angiogenesis and fibroblast proliferation in the sclera and conjunctiva are reduced [

12]. These factors, along with lower collagen synthesis and structural changes, may impair the ability of tissue to contract and result in increased collagen density, granulation, and enhanced re-epithelialization [

12]. Additionally, breakdown of the blood aqueous barrier, release of cytokines, and persistent inflammation may alter the remodeling of surgical wound, potentially contributing to poorer outcomes.

In the statistical analysis of the relationship between postoperative IOP and preoperative IOP, multiple regression revealed a significant correlation (P < 0.001) between preoperative IOP and IOP values at 6 months or 12 months post-surgery. However, in the multivariate linear mixed model, the relationship between preoperative IOP and IOP at 6 months post-surgery showed marginal significance with P = 0.08.

Since the purpose of the multivariate linear mixed model is to examine the random effect of DM, there is a possibility that confounding effects due to DM being involved. Additionally, the multivariate linear mixed model is considered to examine the relationship between preoperative IOP and the variability in post-surgical IOP outcomes, which may explain the discrepancy in results compared to the linear regression analysis.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size of diabetic subjects is relatively small. Second, the retrospective design may introduce unforeseen biases that could affect the results. Lastly, the severity and duration of diabetes, which could potentially influence the outcome, were not assessed in this study and should be addressed in future research.

6. Conclusions

We studied surgical outcomes of concomitant Schlemm’s canal opening MIGS and cataract surgery in 25 diabetic and 84 non-diabetic POAG or ocular hypertension. Post surgical IOP decreased significantly in both diabetic and non-diabetic cohorts. However, the IOP reduction in diabetic cohort was significantly lower than that in non-diabetic cohort.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EC.; methodology, EC.; software, EC.; validation, EC. and EN.; formal analysis, EC.; investigation, EC.; resources, EC.; data curation, EC.; writing—original draft preparation, EC.; writing—review and editing, EN.; visualization, TC.; supervision, TC.; project administration, TC.; funding acquisition, EC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sensho-kai Eye Institute, and The APC was funded by Sensho-kai Eye Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Study design of this study was approved by the IRB at Sensho-kai (Head H Amano) approval number is C2014-1. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sensho-kai Eye Institute.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent for publication was not specifically obtained from the participating patients; however, the possibility of publication was disclosed during the process of obtaining consent for surgical agreement. The content of this paper does not identify individual participants, and the IRB waived the requirement for additional consent for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The research data used in this research are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the technicians at Sensho-kai for providing data that contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Minckler, D.S.; Baerveldt, G.; Alfaro, M.R.; Francis, B.A. Clinical results with the Trabectome for treatment of open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2005, 112, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibold, L.K.; Soohoo, J.R.; Ammar, D.A.; Kahook, M.Y. Preclinical investigation of ab interno trabeculectomy using a novel dual-blade device. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013, 155, 524–529.e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanito, M.; Sano, I.; Ikeda, Y.; Fujihara, E. Microhook ab interno trabeculotomy, a novel minimally invasive glaucoma surgery, in eyes with open-angle glaucoma with scleral thinning. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016, 94, e371–e372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chihara, E.; Chihara, T. Development and Application of a New T-shaped Internal Trabeculotomy Hook (T-hook). Clin Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 3919–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, D.S.; Godfrey, D.G.; Smith, O.; Feuer, W.J.; Montes de Oca, I.; Fellman, R.L. Gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy, ab interno trabeculotomy: technique report and preliminary results. Ophthalmology. 2014, 121, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chihara, E.; Chihara, T. Consequences of clot formation and hyphema post-internal trabeculotomy for glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2024, 33, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chihara, E.; Hamanaka, T. Historical and Contemporary Debates in Schlemm’s Canal-Based MIGS. J Clin Med. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, A.; Ichioka, S.; Takayanagi, Y.; Tsutsui, A.; Manabe, K.; Tanito, M. Comparison of Postoperative Hyphemas between Microhook Ab Interno Trabeculotomy and iStent Using a New Hyphema Scoring System. J Clin Med. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, S.K.; Hosseini, H.; Saidi, E.; Nassiri, N.; Neelakanta, G.; Giaconi, J.A.; Caprioli, J. Long-term outcomes of primary trabeculectomy in diabetic patients with primary open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013, 97, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dally, L.; Ederer, F.; Gaasterland, D.; Beth Blackwell, B.; VanVeldhuisen, P.; Allen, R.; Beck, A.; Weber, P.; Ashburn, F. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention study (AGIS): 11. Risk factors for failure of trabeculectomy and Argon laser trabeculoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002, 134, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koucheki, B.; Hashemi, H. Selective laser trabeculoplasty in the treatment of open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2012, 21, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasari, N.; Jiang, A.; Skochdopole, A.; Chung, J.; Reece, E.M.; Vorstenbosch, J.; Winocour, S. Updates in Diabetic Wound Healing, Inflammation, and Scarring. Semin Plast Surg. 2021, 35, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).