1. Introduction

Despite the advanced diagnostic capabilities of modern medicine, certain diseases and dysfunctions in the human body remain challenging to diagnose and treat early on. Often, this is due to a limited understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving the formation and progression of the pathology, leading to restricted therapeutic options. Breast cancer (BC) ranks among the most prevalent cancers globally, while recent advancements in diagnosis and treatment have improved survival rates; however, the survival is associated with an increased risk of complications. One of the most severe complications is breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) [

1], which significantly diminishes quality of life for affected individuals [

2]. The development of BCRL before the appearance of visible symptoms can last from several months to up to 10 years post-surgery, affecting approximately 20-49% of breast cancer survivors [

3].

Lymphedema or lymphoedema is a condition characterized by regional lymphatic dysfunction due to impaired lymphatic fluid flow or its complete absence. The disease progression is accompanied by chronic inflammation and results in gradual accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space. This results in limb swelling, as well as fibrotic changes in the skin and subcutaneous tissues due to compromised lymphatic system function [

4].

Current secondary lymphedema treatment options, including both conservative and surgical approaches, primarily address symptoms, slow disease progression, and mitigate complications. However, these treatments often fail to substantially improve the quality of life for patients [

5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for novel and effective early diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for BCRL.

A most promising approach to tackling these challenges involves the use of high-throughput omics technologies, particularly metabolomics [

6]. Various

omics investigate different molecular levels of tissue functioning organization, encompassing the genome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, lipidome, etc. While the genome represents the most stable molecular level, the metabolome stands out as the most dynamic and responsive to changes caused by numerous internal and external factors. Moreover, metabolomic profile exerts a profound influence on a tissue physiology. The concentrations of metabolites in tissues or fluids are typically regulated within narrow ranges by their roles in metabolic processes. However, the onset of pathological conditions, such as malignant tumors and postoperative complications, can result in significant alterations in both the metabolic cycles of affected tissues and the blood metabolome [

7].

The correct collection of biosamples for metabolomic purposes is a crucial step, performed even before the initial treatment of samples, such as metabolic activity quenching or extraction of metabolites. While blood sampling is a routine clinical procedure, sampling of interstitial fluid (ISF) presents a challenge. Recently, we developed and tested a novel ISF sampling method [

8], which was employed in this study and allowed for the successful acquisition of this valuable material from BCRL patients.

In the current study, we employed a quantitative metabolomic approach based on the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to investigate changes in the human lymphatic system's function associated with BCRL progression. The objectives were to identify metabolomic biomarkers of lymphedema in the ISF and blood serum of patients who had undergone BC treatment and to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying lymphedema onset and progression. This research aims to deepen insights into lymphatic system function and offers potential for the development of promising and minimally invasive methods for early BCRL diagnosis and personalized treatment.

4. Discussion

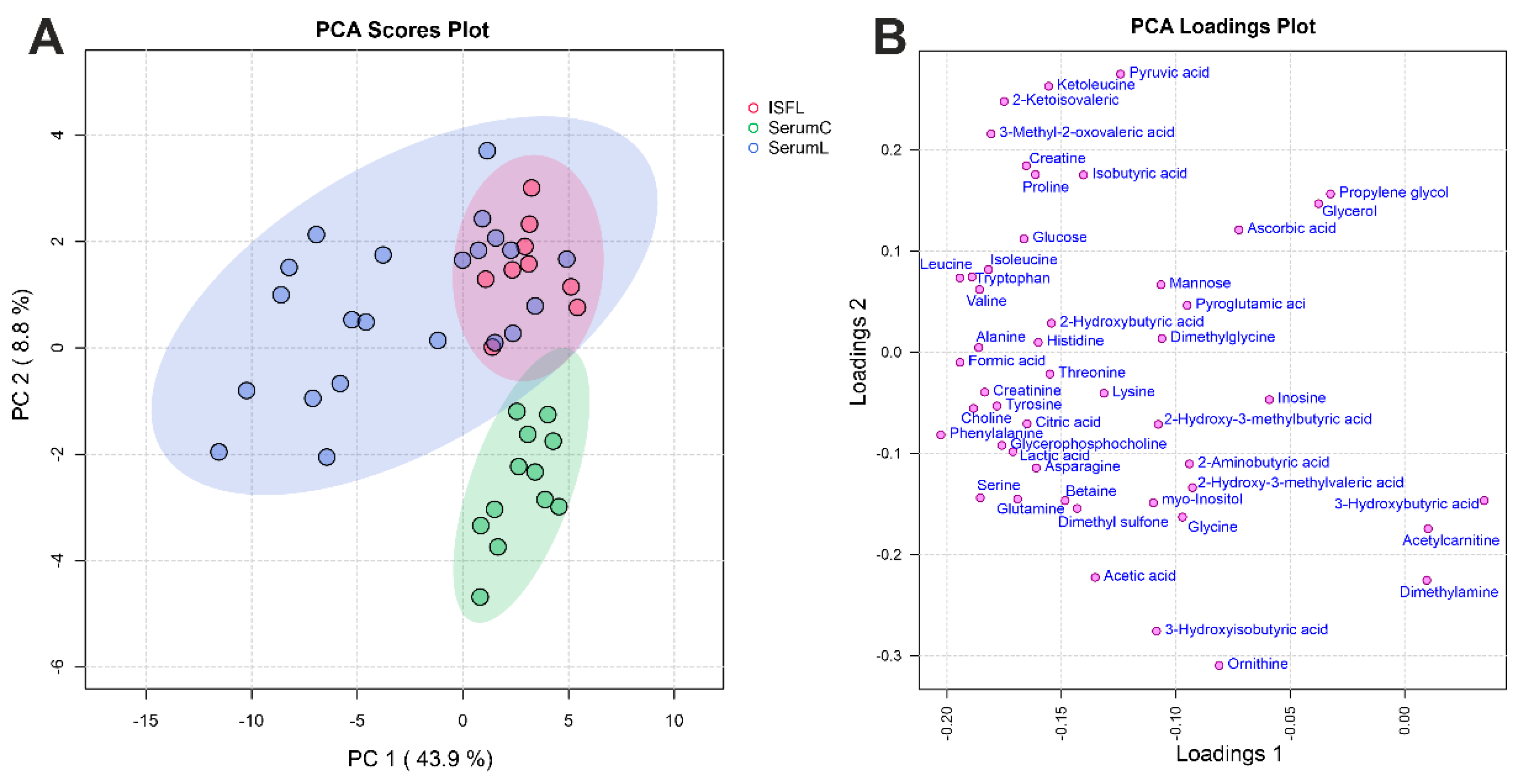

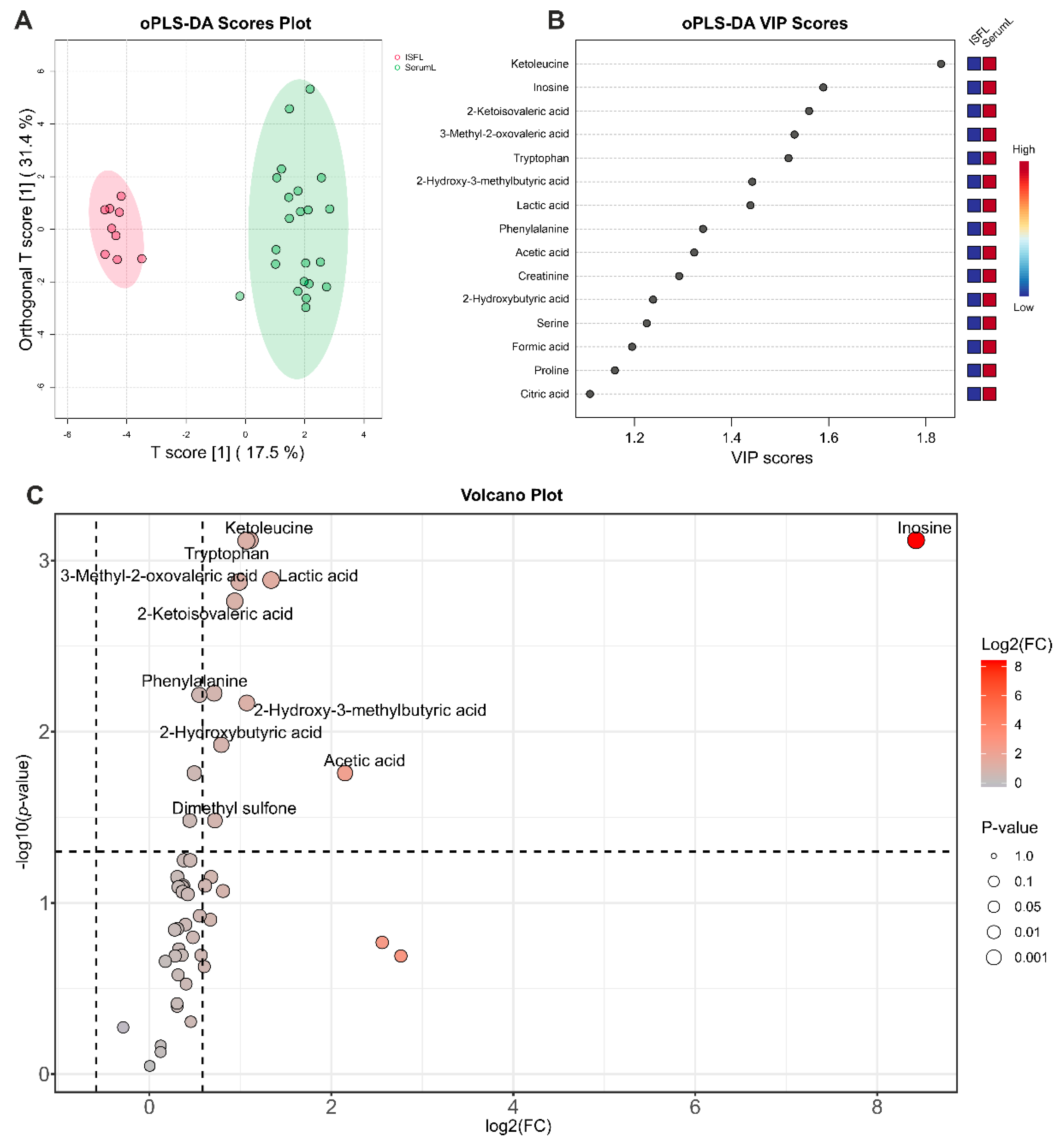

Analysis of quantitative data obtained by NMR method on concentrations of the most abundant metabolites indicates that serum and ISF in BCRL patients have a rather similar metabolomic composition: concentrations of the majority of metabolites (

Table 1) are comparable, although nearly all compounds exhibit slightly higher concentrations in serum compared to ISF (

Figure 3C). PCA analysis (

Figure 2) supports this observation showing no clear separation between the serum and ISF sample groups. The most pronounced statistically significant differences between serum and ISF revealed by a combination of univariate and supervised multivariate statistics were (oPLS-DA) observed for inosine, ketoleucine, tryptophan, lactic acid, 3-methyl-2-oxovaleric acid, 2-ketoisovaleric acid, phenylalanine, 2-hydroxy-3-methylbutyric acid, 2-hydroxybutyric acid, acetic acid, creatinine, serine, formic acid, proline, and citric acid. The metabolomic composition of ISF may differ from that of serum due to the disruption of ISF outflow into the lymphatic vessels in secondary lymphedema, accompanied by altered biochemical processes in the extracellular matrix and chronic inflammation. Assuming that under normal conditions the metabolomic compositions of serum and ISF are in dynamic equilibrium [

14,

15], it can be concluded that the increased generation of these metabolites in the blood or their elevated consumption in ISF leads to a partial disruption of this equilibrium. The implications of the increased metabolite generation are discussed below.

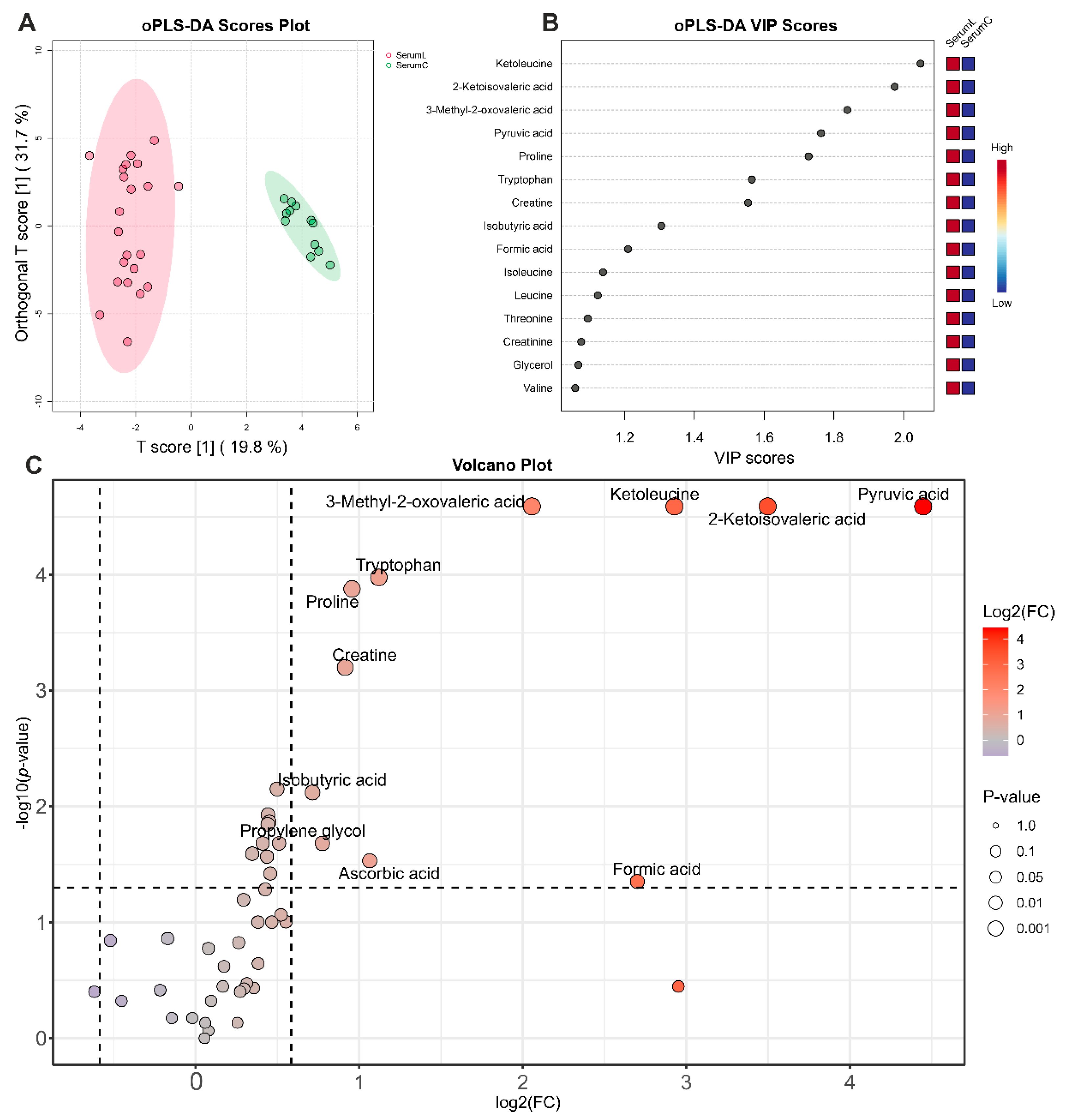

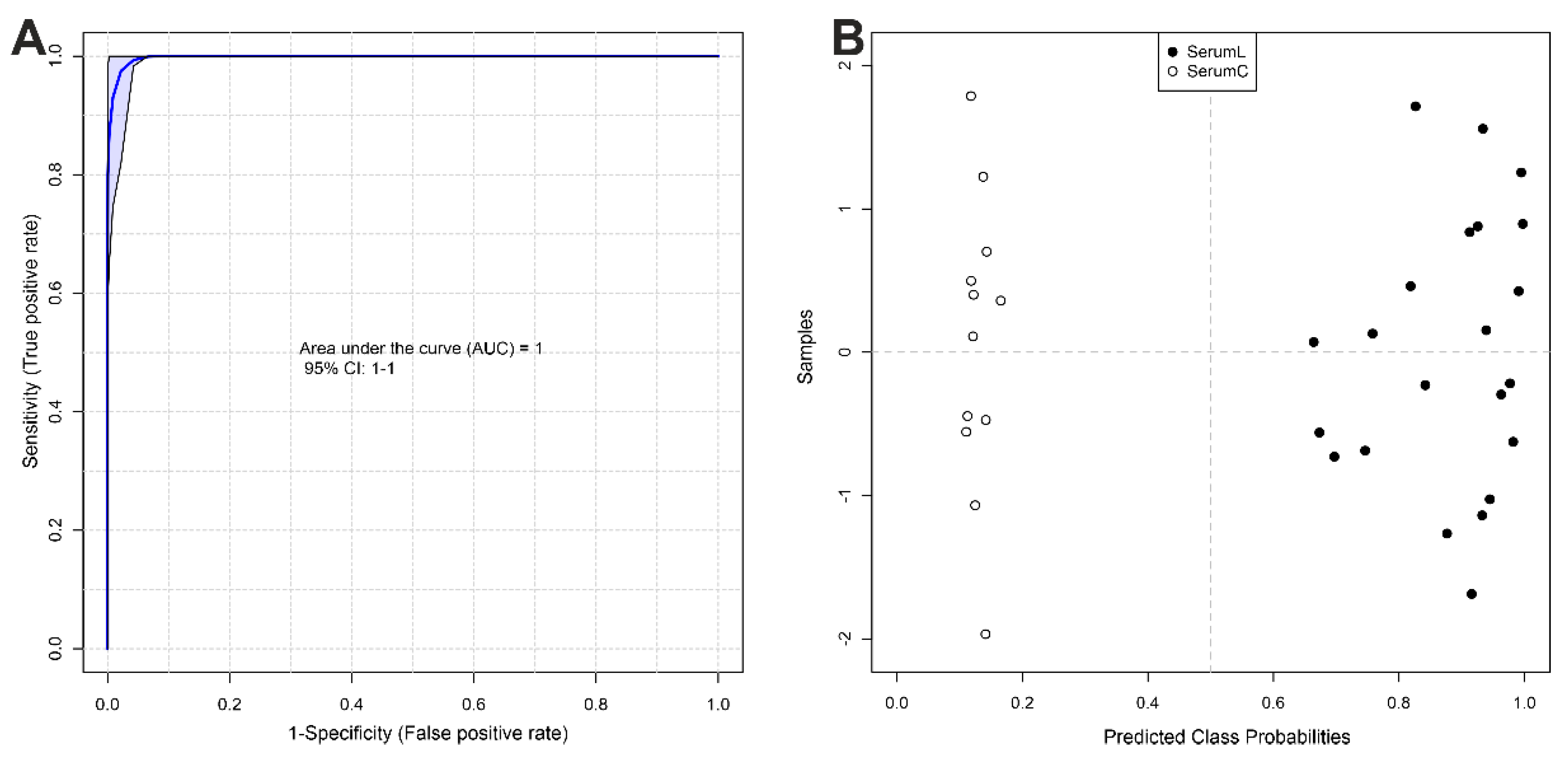

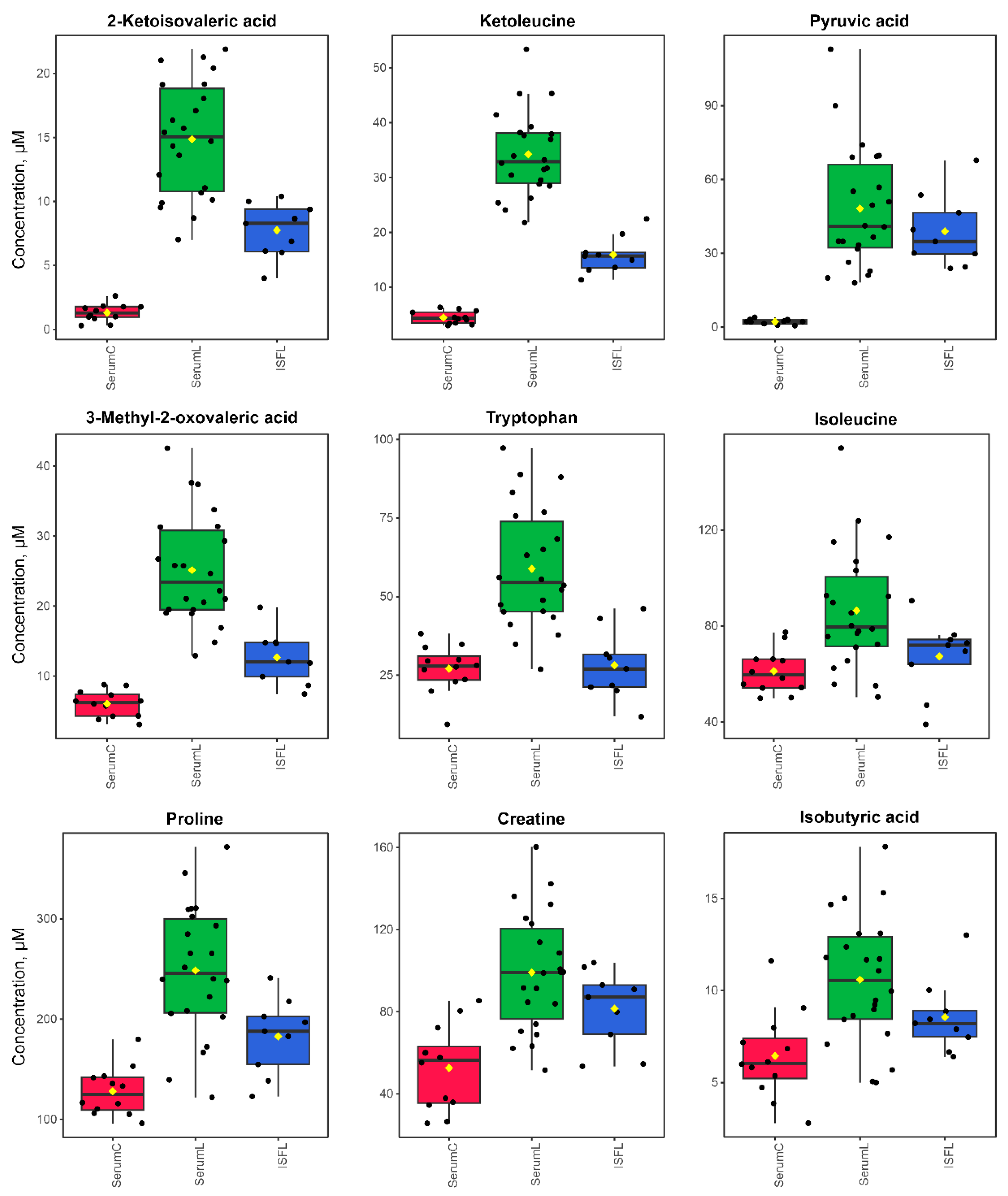

The most pronounced differences in the serum of BCRL and control patients, identified through a combination of univariate and multivariate statistics (

Figure 4), were observed for pyruvic acid, 2-ketoisovaleric acid, ketoleucine, 3-methyl-2-oxovaleric acid, tryptophan, proline, creatine, isobutyric acid, propylene glycol, ascorbic acid, formic acid, isoleucine, leucine, threonine, creatinine, glycerol, and valine; all concentrations are increased in BCRL patients. Biomarker analysis using the ROC-AUC method further supports the differences in 11 of these metabolites, demonstrating high diagnostic significance (AUC > 0.8,

Table 2).

It should be noted that the magnitude of the increase in the differential metabolite concentrations in BCRL serum, compared to control serum, was noticeably greater than the magnitude of differences observed between BCRL serum and BCRL ISF, as well as the differences between control serum and BCRL ISF (

Figure 7,

Figure S3). This suggests that the observed metabolomic changes primarily occur in the blood rather than in ISF. Subsequently, these alterations in the blood spread to ISF [

14], resulting in less pronounced changes in metabolite concentrations in ISF. Unfortunately, direct comparison of ISF from BCRL and control groups was not possible, due to study limitations related to the current difficulties of obtaining ISF from control patients and from unaffected arms of BCRL patients. Nevertheless, the proposed interpretation of the observed alterations in metabolite concentrations among the sample groups appears to be the most plausible. Therefore, blood serum emerges as a promising fluid for the development of early lymphedema diagnostics additionally to ISF. Moreover, the ease of collecting blood samples compared to ISF could expedite further research on BCRL.

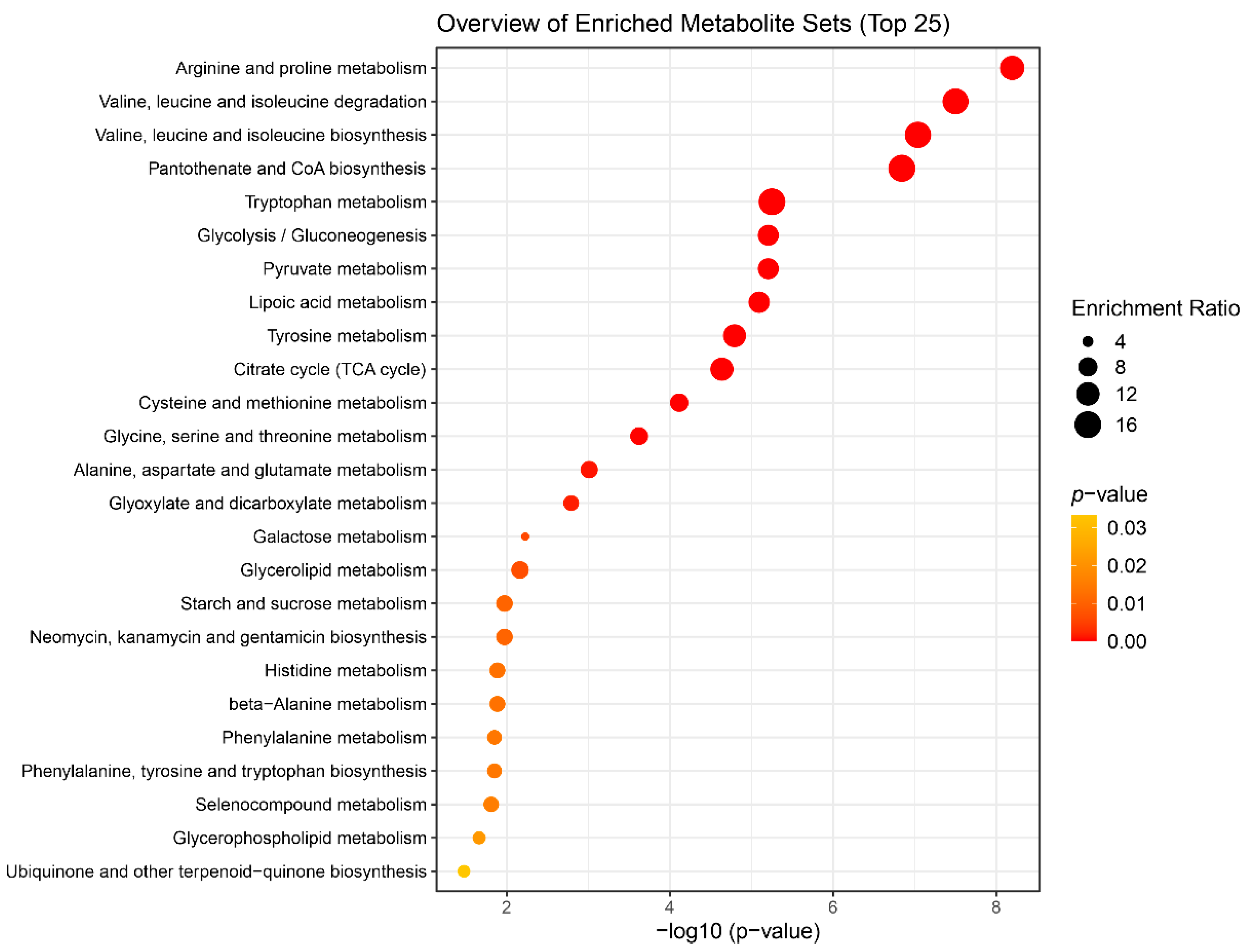

The pathogenesis of lymphedema involves chronic inflammation, increased adipose tissue, interstitial fluid accumulation, and subsequent tissue fibrosis leading to the development of the disease. Based on the results of the enrichment analysis, we assessed the significance of biochemical pathways in the development of lymphedema. It should be noted that our study had another limitation due to the lack of data from patients who had undergone BC treatment but did not develop BCRL. However, a few recent studies have reported changes in the blood plasma metabolome following surgical and chemotherapy treatment of BC [

16,

17]. Pathways altered after 1 month include purine metabolism, galactose metabolism and several others [

16]. One year after BC treatment changes in lysine degradation, branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) metabolism, linoeic acid metabolism, and tyrosine metabolism have been observed [

17]. In the current study, most patients undergone chemotherapy and surgery more than one year prior to sample collection (

Table S1), and all patients showed no signs of BC recurrence.

Most of the enriched metabolic sets listed in the

Table 3 characterize the activation of energy production pathways. The processes of BCRL development are accompanied by activation of the defense mechanisms required by the body for an effective response to the disease. Usually, energy deficiency manifests itself in an increase in the content of intermediates of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, protein metabolism and fatty acid oxidation. In our case, the processes related to the TCA cycle, the degradation of valine, leucine and isoleucine (BCAA), the metabolism of other amino acids, pyruvate, and lipoic acid are noted. These processes indicate the activity of glycolysis or gluconeogenesis in the body (which is also in the QMSEA list,

Table 3), and they are involved in replenishing the energy needs of the body to fight the disease. It is worth noting the activation of the synthesis of pantothenate and coenzyme A, which are important substrates of the metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins and fatty acids, complements the hypothesis of activation of energy production processes [

18].

In addition to the energy role, metabolic processes involving glutamine may reflect increased activity of immune cells, since glutamine is used as an energy source by immune cells – lymphocytes, neutrophils and macrophages [

19]. Branched-chain amino acids have been shown to play a signaling role in regulatory T-cells, which are a subset of immune cells that, among other activities, perform immunosuppressive functions [

20].

The metabolism of methylating agents – serine, glycine, betaine, and methionine – affects key biochemical processes. It is particularly interesting that hypermethylation, according to previous studies, is associated with shifting immune responses toward a T-helper 2 (Th2) proinflammatory response, and also contributes to an increase in cytokine production, thereby generally intensifying inflammation [

21,

22]. It was described earlier [

4] that the inflammatory response in secondary lymphedema typically involves upregulated expression of various cytokines and chemokines, as well as an increase in the accumulation and activation of immune cells. In a mouse model, an increased number of CD4+ T cells and increased Th2 differentiation were observed [

23]. Th2 cells play a significant role in the pathogenesis of lymphedema, as inhibition of their differentiation has been shown to reduce fibrosis and improve lymphatic function [

23,

24]. Thus, information on altered in the metabolism of methylating agents may be used for the development of subsequent studies on BCRL.

The data obtained demonstrate the potential for further search and verification of biomarkers though targeted monitoring of metabolites in these pathways on a larger cohort, enabling a more reliable assessment of deviations in the biochemical processes involving these metabolites.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results of the statistical analysis of 1H NMR quantitative data obtained from serum and ISF samples from BCRL and control patient groups, we made the following observations. Serum and ISF display a rather similar metabolomic composition, though concentrations of nearly all compounds are slightly higher in serum compared to ISF. Significant differences in metabolite concentrations between the serum of BCRL and control patients were identified using multiple statistical methods. Differential metabolites that may serve as potential biomarkers for lymphedema are 2-ketoisovaleric acid, 3-methyl-2-oxovaleric acid, ketoleucine, pyruvic acid, tryptophan, proline, creatine, isoleucine, isobutyric acid, leucine, and creatinine. The most significantly altered metabolic pathways, as evaluated by enrichment analysis, include “Arginine and proline metabolism”, pathways of branched-chain amino acids, “Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis”, “Tryptophan metabolism”, “Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis”, “Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism”, “Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism”, “Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism”, all of which are associated with the activation of energy production and inflammation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.V.Y. and V.V.N.; methodology, L.V.Y., N.A.O., and Y.P.T.; formal analysis, V.V.Y., L.V.Y., and D.S.G.; investigation, L.V.Y., D.S.G. and N.A.O.; resources, V.V.N.; visualization, L.V.Y., D.S.G., and V.V.Y; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, V.V.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.V.Y., N.A.O., and Y.P.T.; project administration, funding acquisition, L.V.Y.; supervision, Y.P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

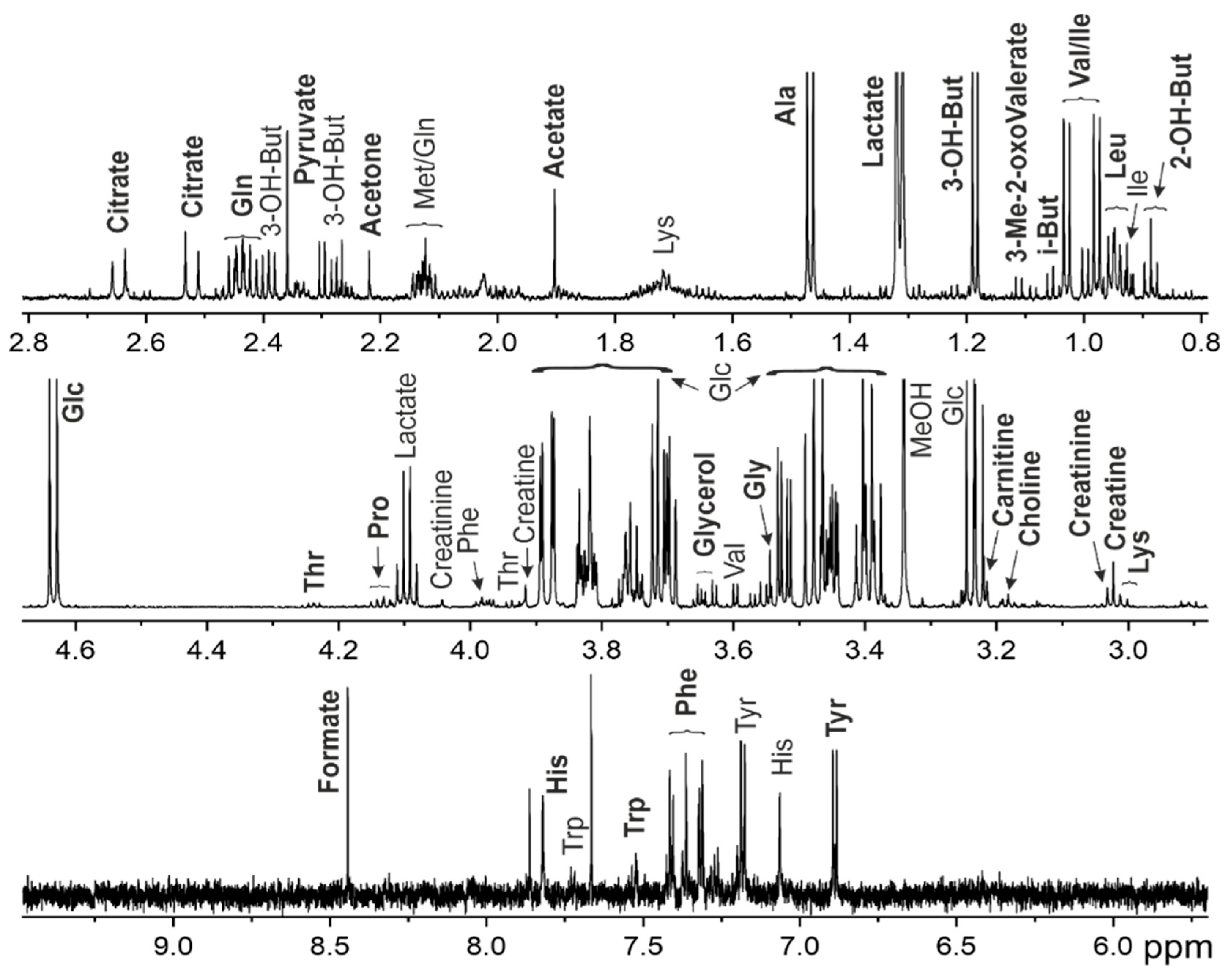

Figure 1.

Representative 1H NMR spectrum for interstitial fluid of 70 y.o. patient with grade IIa lymphedema of the left upper limb. Abbreviations: 2-OH-But - 2-hydroxybutyrate, 3-Me-2-oxoValerate—3-Methyl-2-oxovalerate, 3-OH-But - 3-hydroxybutyrate, Glc – glucose, i-But – isobutyrate, MeOH—methanol. For amino acids, a standard tree letter code is used.

Figure 1.

Representative 1H NMR spectrum for interstitial fluid of 70 y.o. patient with grade IIa lymphedema of the left upper limb. Abbreviations: 2-OH-But - 2-hydroxybutyrate, 3-Me-2-oxoValerate—3-Methyl-2-oxovalerate, 3-OH-But - 3-hydroxybutyrate, Glc – glucose, i-But – isobutyrate, MeOH—methanol. For amino acids, a standard tree letter code is used.

Figure 2.

Overview of the entire dataset by PCA method. (A) PCA scores and (B) loadings plots for the sample groups. SerumC (green) – serum samples from control group, SerumL (blue) – serum samples from BCRL group, ISFL (red) – interstitial fluid samples from BCRL group. Variance explained by the first (PC 1) and second (PC 2) principal components are indicated on the axis. Colored ovals indicate 95% confidence regions.

Figure 2.

Overview of the entire dataset by PCA method. (A) PCA scores and (B) loadings plots for the sample groups. SerumC (green) – serum samples from control group, SerumL (blue) – serum samples from BCRL group, ISFL (red) – interstitial fluid samples from BCRL group. Variance explained by the first (PC 1) and second (PC 2) principal components are indicated on the axis. Colored ovals indicate 95% confidence regions.

Figure 3.

Analysis of differences between serum and ISF from BCRL patients. (A) oPLS-DA scores plot between serum (SerumL, green) and ISF (ISFL, red) samples. The T-score axis represents between-group variation, and the orthogonal T-score axis – within-group variation. Colored ovals indicate 95% confidence regions. (B) VIP scores plot for the top 15 metabolites from oPLS-DA. The colored boxes on the right indicate an increase (red) or a decrease (blue) in the metabolite abundance for the corresponding group. (C) Volcano plot. The x-axis represents the mean fold change (FC) between groups, and the y-axis represents the statistical significance of changes. Dashed lines indicate thresholds, and the color and the size of the circle indicate FC and p-values, respectively.

Figure 3.

Analysis of differences between serum and ISF from BCRL patients. (A) oPLS-DA scores plot between serum (SerumL, green) and ISF (ISFL, red) samples. The T-score axis represents between-group variation, and the orthogonal T-score axis – within-group variation. Colored ovals indicate 95% confidence regions. (B) VIP scores plot for the top 15 metabolites from oPLS-DA. The colored boxes on the right indicate an increase (red) or a decrease (blue) in the metabolite abundance for the corresponding group. (C) Volcano plot. The x-axis represents the mean fold change (FC) between groups, and the y-axis represents the statistical significance of changes. Dashed lines indicate thresholds, and the color and the size of the circle indicate FC and p-values, respectively.

Figure 4.

Analysis of differences between serum samples from BCRL patients and controls. (A) oPLS-DA scores plot between serum samples of BCRL patients (SerumL, red) and controls (SerumC, green). The T-score axis represents between-group variation, and the orthogonal T-score axis – within-group variation. Colored ovals indicate 95% confidence regions. (B) VIP scores plot for top 15 metabolites from oPLS-DA. The colored boxes on the right indicate an increase (red) or a decrease (blue) in metabolite abundance for the corresponding group. (C) Volcano plot. The x-axis represents the mean fold change (FC) between groups, and the y-axis represent the statistical significance of changes. Dashed lines indicate thresholds, and the color and the size of the circle indicate FC and p-values, respectively.

Figure 4.

Analysis of differences between serum samples from BCRL patients and controls. (A) oPLS-DA scores plot between serum samples of BCRL patients (SerumL, red) and controls (SerumC, green). The T-score axis represents between-group variation, and the orthogonal T-score axis – within-group variation. Colored ovals indicate 95% confidence regions. (B) VIP scores plot for top 15 metabolites from oPLS-DA. The colored boxes on the right indicate an increase (red) or a decrease (blue) in metabolite abundance for the corresponding group. (C) Volcano plot. The x-axis represents the mean fold change (FC) between groups, and the y-axis represent the statistical significance of changes. Dashed lines indicate thresholds, and the color and the size of the circle indicate FC and p-values, respectively.

Figure 5.

Biomarker analysis between serum samples from BCRL patients (SerumL, full circles) and controls (SerumC, open circles). (A) ROC curve plot for the created biomarker model (combination of 5 metabolites), based on its average performance across all MCCV runs, with the 95 % confidence interval. (B) Predicted class probabilities for all samples using the created biomarker model. Due to balanced subsampling, the classification boundary is at the center (x = 0.5, dotted line).

Figure 5.

Biomarker analysis between serum samples from BCRL patients (SerumL, full circles) and controls (SerumC, open circles). (A) ROC curve plot for the created biomarker model (combination of 5 metabolites), based on its average performance across all MCCV runs, with the 95 % confidence interval. (B) Predicted class probabilities for all samples using the created biomarker model. Due to balanced subsampling, the classification boundary is at the center (x = 0.5, dotted line).

Figure 6.

Summary plot for the Quantitative Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (QMSEA), presenting top 25 enriched metabolite sets. The size of the circles indicates the enrichment ratio, the color indicates the statistical significance.

Figure 6.

Summary plot for the Quantitative Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (QMSEA), presenting top 25 enriched metabolite sets. The size of the circles indicates the enrichment ratio, the color indicates the statistical significance.

Figure 7.

Boxplots for the concentrations (in µM) of differential metabolites. SerumC (red) – serum samples from control group, SerumL (green) – serum samples from BCRL group, ISFL (blue) – interstitial fluid samples from BCRL group.

Figure 7.

Boxplots for the concentrations (in µM) of differential metabolites. SerumC (red) – serum samples from control group, SerumL (green) – serum samples from BCRL group, ISFL (blue) – interstitial fluid samples from BCRL group.

Table 1.

Averaged concentrations of metabolites in sample groups. Values are given in µM as mean ± standard deviation. SerumC – serum samples from control group, SerumL – serum samples from BCRL group, ISFL – interstitial fluid samples from BCRL group.

Table 1.

Averaged concentrations of metabolites in sample groups. Values are given in µM as mean ± standard deviation. SerumC – serum samples from control group, SerumL – serum samples from BCRL group, ISFL – interstitial fluid samples from BCRL group.

| Metabolites\Groups |

SerumC |

SerumL |

ISFL |

| 2-Aminobutyric acid |

27 ± 5 |

27 ± 10 |

22 ± 9 |

| 2-Hydroxy-3-methylbutyric acid |

8.7 ± 4.1 |

9.3 ± 3 |

4.4 ± 3 |

| 2-Hydroxy-3-methylvaleric acid |

25 ± 2 |

26 ± 18 |

17 ± 7 |

| 2-Hydroxybutyric acid |

64 ± 19 |

84 ± 29 |

48 ± 21 |

| 2-Ketoisovaleric acid |

1.3 ± 0.7 |

15 ± 5 |

7.8 ± 2.1 |

| 3-Hydroxybutyric acid |

230 ± 210 |

150 ± 120 |

100 ± 90 |

| 3-Hydroxyisobutyric acid |

32 ± 5 |

22 ± 15 |

16 ± 6 |

| 3-Methyl-2-oxovaleric acid |

6 ± 1.9 |

25 ± 8 |

13 ± 4 |

| Acetic acid |

270 ± 40 |

240 ± 160 |

54 ± 7 |

| Acetylcarnitine |

12 ± 3 |

11 ± 4 |

10 ± 2 |

| Alanine |

400 ± 90 |

550 ± 180 |

410 ± 90 |

| Ascorbic acid |

2.9 ± 2 |

6.1 ± 4 |

3.5 ± 4.4 |

| Asparagine |

47 ± 7 |

58 ± 27 |

39 ± 14 |

| Betaine |

35 ± 11 |

44 ± 22 |

27 ± 12 |

| Choline |

11 ± 2 |

15 ± 6 |

11 ± 3 |

| Citric acid |

130 ± 30 |

160 ± 40 |

120 ± 30 |

| Creatine |

53 ± 20 |

99 ± 29 |

82 ± 19 |

| Creatinine |

73 ± 17 |

100 ± 28 |

68 ± 9 |

| Dimethylamine |

4.8 ± 2.9 |

3.5 ± 2.4 |

2.3 ± 1.4 |

| Dimethylglycine |

2.9 ± 0.8 |

4.1 ± 2 |

3.8 ± 1.6 |

| Dimethyl sulfone |

10 ± 3.3 |

11 ± 5 |

6.4 ± 2.9 |

| Formic acid |

33 ± 3 |

210 ± 170 |

36 ± 6 |

| Glucose |

5100 ± 700 |

6900 ± 2200 |

5300 ± 900 |

| Glutamine |

530 ± 100 |

650 ± 210 |

470 ± 70 |

| Glycerol |

140 ± 30 |

200 ± 70 |

180 ± 50 |

| Glycerophosphocholine |

47 ± 11 |

61 ± 24 |

40 ± 8 |

| Glycine |

260 ± 90 |

310 ± 150 |

230 ± 70 |

| Histidine |

67 ± 13 |

92 ± 32 |

72 ± 15 |

| Inosine |

6.6 ± 4.7 |

6.9 ± 4.6 |

0 |

| Isobutyric acid |

6.5 ± 2.4 |

11 ± 3 |

8.6 ± 2 |

| Isoleucine |

61 ± 9 |

86 ± 25 |

67 ± 16 |

| Ketoleucine |

4.5 ± 1.1 |

34 ± 8 |

16 ± 3 |

| Lactic acid |

2700 ± 700 |

3500 ± 1600 |

1400 ± 500 |

| Leucine |

130 ± 20 |

170 ± 40 |

140 ± 20 |

| Lysine |

170 ± 30 |

190 ± 50 |

170 ± 30 |

| Mannose |

64 ± 17 |

72 ± 17 |

58 ± 15 |

| myo-Inositol |

44 ± 12 |

46 ± 15 |

36 ± 14 |

| Ornithine |

81 ± 15 |

72 ± 28 |

55 ± 13 |

| Phenylalanine |

74 ± 16 |

100 ± 30 |

62 ± 13 |

| Proline |

130 ± 20 |

250 ± 70 |

180 ± 40 |

| Propylene glycol |

3.6 ± 3.4 |

6.2 ± 2.4 |

7.6 ± 4.5 |

| Pyroglutamic acid |

11 ± 10 |

88 ± 126 |

13 ± 20 |

| Pyruvic acid |

2.2 ± 1 |

48 ± 25 |

39 ± 15 |

| Serine |

250 ± 40 |

300 ± 80 |

210 ± 40 |

| Threonine |

100 ± 20 |

140 ± 40 |

110 ± 30 |

| Tryptophan |

27 ± 8 |

59 ± 19 |

28 ± 11 |

| Tyrosine |

62 ± 16 |

83 ± 31 |

67 ± 9 |

| Valine |

230 ± 40 |

300 ± 70 |

240 ± 40 |

Table 2.

Result of univariate biomarker analysis. AUC - Area under ROC curve.

Table 2.

Result of univariate biomarker analysis. AUC - Area under ROC curve.

| Metabolite |

AUC |

p-value |

Fold Change |

| 2-Ketoisovaleric acid |

1.00 |

1.29E-11 |

-3.50 |

| 3-Methyl-2-oxovaleric acid |

1.00 |

2.40E-09 |

-2.06 |

| Ketoleucine |

1.00 |

1.86E-14 |

-2.93 |

| Pyruvic acid |

1.00 |

3.25E-07 |

-4.45 |

| Tryptophan |

0.96 |

5.63E-06 |

-1.12 |

| Proline |

0.95 |

7.58E-07 |

-0.96 |

| Creatine |

0.91 |

2.40E-05 |

-0.91 |

| Isoleucine |

0.84 |

0.0023 |

-0.50 |

| Isobutyric acid |

0.84 |

0.0008 |

-0.72 |

| Leucine |

0.82 |

0.0019 |

-0.44 |

| Creatinine |

0.80 |

0.0053 |

-0.45 |

Table 3.

Most affected metabolic pathways determined by QMSEA and associated metabolites. FDR – false discovery rate correction for p-values.

Table 3.

Most affected metabolic pathways determined by QMSEA and associated metabolites. FDR – false discovery rate correction for p-values.

| Metabolite Set |

Total Compounds |

Hits |

p-value (FDR) |

Associated metabolites |

| Arginine and proline metabolism |

36 |

4 |

2.69E-07 |

creatine; proline; ornithine; pyruvic acid |

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation |

39 |

7 |

6.66E-07 |

3-methyl-2-oxovaleric acid; valine; 2-ketoisovaleric acid; isoleucine; 3-hydroxyisobutyric acid; ketoleucine; leucine |

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis |

8 |

7 |

1.28E-06 |

threonine; 3-methyl-2-oxovaleric acid; leucine; 2-ketoisovaleric acid; isoleucine; ketoleucine; valine |

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis |

20 |

2 |

1.52E-06 |

valine; 2-ketoisovaleric acid |

| Tryptophan metabolism |

41 |

1 |

3.75E-05 |

tryptophan |

| Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis |

26 |

2 |

3.75E-05 |

pyruvic acid; acetic acid |

| Pyruvate metabolism |

23 |

2 |

3.75E-05 |

pyruvic acid; acetic acid |

| Lipoic acid metabolism |

28 |

2 |

4.24E-05 |

pyruvic acid; glycine |

| Tyrosine metabolism |

42 |

2 |

7.55E-05 |

tyrosine; pyruvic acid |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) |

20 |

2 |

9.70E-05 |

citric acid; pyruvic acid |

| Cysteine and methionine metabolism |

33 |

3 |

0.00029393 |

serine; 2-aminobutyric acid; pyruvic acid |

| Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism |

33 |

8 |

0.00083638 |

serine; choline; betaine; dimethylglycine; glycine; threonine; creatine; pyruvic acid |

| Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism |

28 |

5 |

0.0031553 |

asparagine; alanine; glutamine; citric acid; pyruvic acid |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism |

31 |

7 |

0.0048664 |

citric acid; serine; glycine; acetic acid; pyruvic acid; formic acid; glutamine |