Introduction

Virtual screening of compound libraries has been a widely adopted approach in structure-based drug discovery for finding novel lead compounds. However, the potential exploration of molecules with desired properties is severely curtailed by the limited size of available compound libraries (~10

9).[

1] This constraint pales in comparison to the vast chemical space of “drug-like” compounds, which is estimated to range from 10

23 to 10

60.[

2] To bridge this gap,

de novo drug design offers another approach to delving into the chemical space beyond existing compounds. Conventional

de novo design methods typically rely on a pre-defined fragment library to construct molecular structures in a stepwise manner. Such a building-up process is relatively time-consuming, and yet the structural diversity among the generated molecular structures is in principle limited by the fragment library employed therein. Besides, conventional

de novo design methods often produce molecular structures that are challenging for synthesis due to extensive enumeration.[

3,

4] All these obstacles have hindered the wide application of

de novo design to practical drug discovery efforts.

In recent years, generative models, a type of unsupervised training model, have emerged as invaluable tools in various scientific domains. [

5] Such models were able to generate new samples by comprehending the essential probability distribution underlying the given training samples. Generative models quickly found their applications in the realm of chemistry, where they were typically trained on large compound libraries to capture the intrinsic probability distribution embedded in the molecular structures. By drawing samples from the learned distribution, novel molecular structures were generated, which effectively expanded the accessible chemical space. It has been demonstrated that even a tiny fraction, for example 0.1%, of a compound library, when used to train a generative model, could cover a significant portion of the chemical space spanned by the entire library.[

6] Thus, generative models hold a great promise in expanding the arsenal for drug discovery. Particularly for

de novo drug design, generative models can not only create new molecules but also to craft molecules of specific interest.

Reinforcement learning presents an approach for achieving targeted molecule generation.[

7] Within the framework of reinforcement learning, an agent engages with an environment through a sequence of actions. The agent iteratively refines its policy to maximize cumulative rewards across the action sequence, guided by the environment's feedback. In context of

de novo drug design employing reinforcement learning, an environment is tailored to provide rewards to the agent based on the properties of the generated molecules. Previous studies have demonstrated the utility of reinforcement learning in biasing generative models towards the creation of molecules with desired optimized properties.[

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]

However, many of the current generative models exhibit certain limitations when being evaluated in real-world drug discovery scenarios. For example, some models aim at overly contrived objectives, such as maximization of log P, [

8,

9,

12,

17,

19] which is not directly relevant to drug discovery. Some other models focus exclusively on the binding affinity against a specific target.[

10,

11,

14,

15,

16] However, a successful drug discovery process is multi-objective in nature, where one has to consider and evaluate multiple properties of the candidates simultaneously.[

20,

21,

22,

23] Therefore, we believe that a generative model with practical value for

de novo drug design has to be trained in a multi-objective manner.

Accordingly, we have developed such a molecular generative model, namely METEOR (Molecular Exploration Through multiplE-Objective Reinforcement). METEOR is integrated with a reinforcement learning framework, which allows rapid design of molecules with desirable drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, as well as binding affinity to a user-defined target protein. In METEOR, we employ the Graph Convolutional Policy Network (GCPN) originally proposed by You et al.,[

8] as the fundamental architecture to construct the backend generative model. We evaluated several graph traversal algorithms [

24] in terms of their efficiency in molecular structure generation. We also introduced chemical rules to detect improper substructures, thereby substantially elevating the quality of the molecular structures generated. Importantly, we introduced a special reward function to promote multi-objective optimization, combining considerations of binding affinity to the target protein, drug-likeness, and synthetic accessibility. Here, binding affinity to the target protein was evaluated by PLANET, a GNN-based deep learning model developed by our group.[

25] Finally, we showcased the potential application of METEOR to real-world drug discovery with a retrospective example.

Methods

The Backend Molecule Generative Models

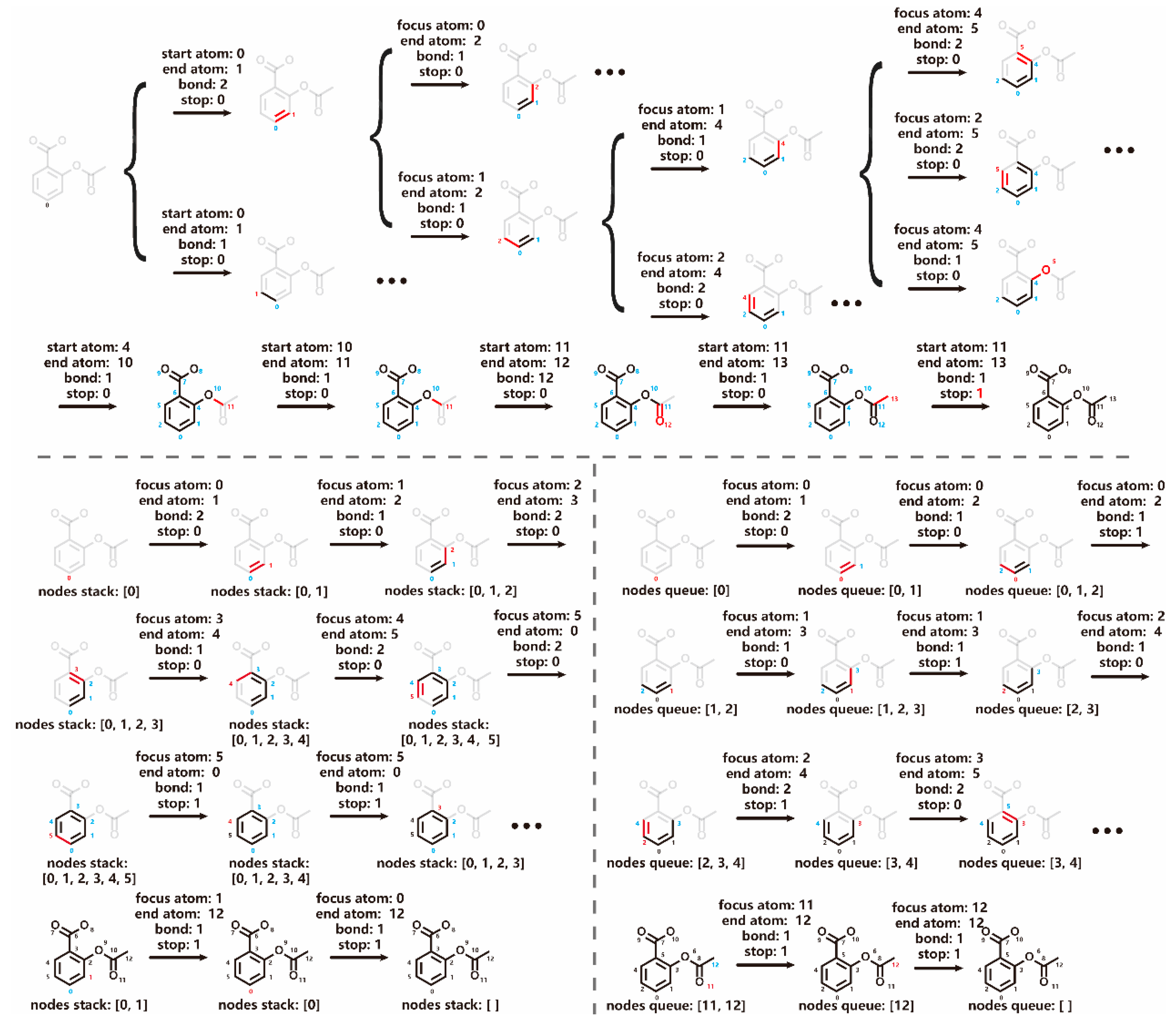

The GCPN model extends an existing molecular graph by adding new chemical bonds one after another (

Figure 1). During this process, four decisions need to be made at each step: (1) determining the starting atom (“focus atom”) to which the new bond is added, (2) selecting the end atom of the new bond, (3) specifying type of the new bond, and (4) deciding whether to terminate graph expansion.[

8] The first decision significantly expands the action space of GCPN, leading to numerous possibilities within each existing subgraph. To address this complexity, we introduced two models: a depth-first model (DFM) and a breadth-first model (BFM), each employing a distinct graph traversal algorithm (

Figure 1). In both models, the “focus atom”, defined by the respective graph traversal algorithm, serves as the starting point for adding a new bond. In alignment with DFM and BFM, the final task in GCPN, i.e., determining whether to terminate graph generation, is replaced by marking the current focus atom as “finished”. Graph generation terminates when all nodes have been marked.

Individual atom nodes were encoded using vectors with a dimension of 20, consisted of one-hot encoded element type, atom degree, and membership in rings of varying sizes from 3 to 7. These initial vectors were then embedded into a latent space (

) with a size of 64 dimensions. To extract features from the input graphs, we utilized the graph convolution network (GCN) architecture.[

26,

27,

28] The entire molecular graph was partitioned into three distinct subgraphs based on different bond orders. One module with three separate graph convolution layers with a hidden size of 64, each with learnable parameters

, were employed on the three subgraphs, as denoted in Equation 1.

is the i

th slice bond-conditioned adjacent matrix,

=

;

is the i

th slice bond-conditioned degree matrix with self-loop.

In our implementation, we utilized three such modules to extract the underlying features from the molecular graphs. The extracted latent features were subsequently utilized to make informed decisions within the model. The configuration of task layers in GCPN remained consistent with the original literature.[

8] In the case of DFM and BFM, when selecting ending atom for the chemical bond to be added, nodes marked as “finished” were overlooked. The probability of each action

was calculated as shown in Equation 2:

Each action step is composed of three sub-tasks , i.e., selecting the end atom of the new bond; specifying type of the new bond and whether to mark the focus atom as “finished”. equals to 0 if the focus atom is not decided to be marked, else equals to 1.

To enhance stability and performance in reinforcement learning, a commonly employed strategy involves pre-training a generative model using an established compound database.[

29] In our study, we employed the widely-used ZINC 250k data set, comprising structurally diverse “drug-like” molecules that have been synthesized in reality. Structures of these molecules were examined to eliminate those containing rings with eight or more members. The remaining molecules were considered as the ground truth and served as expert training data. For GCPN pre-training, a randomly sampled connected subgraph G’ from a molecule graph G, was viewed as the state

. Any action

added an atom or a bond in G but not in G’ could be viewed as an expert action during the trajectory of generating a ground-truth molecule. The training objective was to maximize the possibility

of GCPN to take expert action

at state

. This training approach was similar to that previously reported.[

8] For both DFM and BFM, the molecular structures from the filtered ZINC 250k data set were transformed into expert trajectories by randomly selecting a starting node and traversing the graphs in a depth-first or breadth-first manner, respectively. The resulting expert actions

consisting the trajectories were collected for pre-training DFM and BFM. The objective in expert training for all models can be expressed as shown in Equation 3:

The Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001 was applied. After 1,000,000 training steps, GCPN, DFM and BFM with converged loss were obtained as pre-trained generative models.

The Molecule Generation Environment

Within the context of molecular graph generation under a reinforcement learning framework, the molecule generation environment plays two essential roles, i.e. state transition dynamics and reward assignment.

(1) State Transition Dynamics

The molecule generation environment plays a pivotal role in executing the actions taken by the agent, ensuring adherence to specified rules. One fundamental rule incorporated into the environment is valency check, preventing actions that exceed an atom's maximal valency.[

8] It is noteworthy that substructures adhering to the valency rule might still exhibit instability due to significant strain energy. To supplement the valency check, the environment in our model incorporates detections of the following substructures: (a) cumulative alkenes and peroxyl bonds; (b) double or triple bonds in three or four membered-ring; (c) bridged ring formed with aromatic rings, and (d) macro rings (referring to the smallest set of smallest rings in a molecular graph) with eight or more members. Substructure detection is performed after each agent action through SMARTS matching (see

Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Only actions that pass both the valency check and substructure detection are adopted by the environment to update the current molecule subgraph. Note that generation of macrocyclic structures are not enabled in our model, given the challenges associated with controlling the quality of generated macrocycles. From a practical view, macrocyclic structures are typically derived from certain lead molecules in order to impose conformational constraints. They are normally not desired as promising candidates at the early stage of drug discovery.

(2) Reward Assignment

The behavior of agents is steered by the rewards from the molecule generation environment, which can be categorized into two components: step reward and final reward. A zero-step reward is assigned to each step, except for two specific actions: (a) When a new ring is formed, a small step reward of 0.02 is assigned to encourage ring formation; (b) When an improper action is canceled by the molecular environment, a step reward of -0.2 is given to discourage such actions. The step reward serves to guide the agent's behavior and reduce the occurrence of improper actions. The final reward comprises several domain-specific rewards assigned based on different properties, including drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, and predicted bio-activity. The final reward is calculated as the weighted sum of these rewards, further adjusted by a penalty factor. Reward functions related to specific properties utilize a linear scaling function that maps values between a lower bound and an upper bound, as described in Equation 4:

This type of function is chosen based on the assumption that it is not necessary to optimize certain properties beyond desired ranges. For example, it is not necessary to further optimize the synthetic accessibility of a molecule with a SAScore [

30] higher than 2.0 because it is already good enough at this level.

Generated molecules are evaluated by the following three properties:

(a) Drug-likeness of a molecule is assessed by the QED value,[

31] which ranges within (0.0, 1.0).

(b) Synthetic accessibility of a molecule is evaluated using SAScore, which ranges within [1.0, 10.0]. SAScore is a rule-based tool for estimating synthetic accessibility, and its output is determined by the summation of fragment scores and a complexity penalty. [

30]

(c) Binding affinity to the target protein is predicted by PLANET, a graph neural network model developed in our group.[

25] PLANET operates on two-dimensional molecular graphs as inputs and thus skips the exhaust molecular docking process. Its ultra-fast speed is suitable for processing generated molecules in a large number.

A penalty factor is also implemented to influence the agent model's behavior by scaling the sum of property rewards. This factor is determined based on three aspects:

(a) Complexity penalty (). The complexity penalty is assigned based on the number of heavy atoms in the designed molecule, defined as a linear scaling function akin to Equation 4. The lower and upper bounds for the number of heavy atoms are set to 10 and 40, respectively. Additionally, for molecules with more than two chiral centers, a penalty factor of 0.5 will be multiply to .

(b) Property penalty (

). Since the reward is the sum of three property rewards, it is possible for an agent to receive a high reward from a molecule that possesses two excellent properties but one extremely poor property. The property penalty is applied as follows (Equation 5):

(c) Similarity penalty (

). Agents trained in reinforcement learning tend to generate highly-scored molecules. However, once a local maximum is reached, agents often struggle to explore other areas, leading to a phenomenon known as "policy collapse." Inspired by the work of Blaschke et al.,[

14] we devised a similarity penalty to encourage agents not only to focus on specific favorable regions in the chemical space yielding high scores but also to explore various areas within the space. Our algorithm for calculating the similarity penalty differs from that of Blaschke though: First, all halogen atoms in the molecular structure are ignored. Subsequently, a mapping between the current molecule and those generated before the preceding twenty rounds of roll-out is performed. If a successful mapping is found, a zero-penalty factor is assigned. Molecules passing this mapping step proceed to subsequent similarity calculation. A stack is used to retain favorable molecules, that is, those generated over the preceding 10 rounds of roll-out with a final property reward surpassing 70% of the possible maximum. Tanimoto similarity coefficients between the extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECPF4) of the transformed molecule and all stored high-quality molecules are calculated.

is determined based on the maximal Tanimoto similarity coefficient, as outlined in Equation 6:

The final reward (

) is the weighted sum of all property reward scaled by overall penalty (Equation 7):

Here, i and j denote for different types of molecular property and penalty factor, respectively.

(3) Reinforcement Learning

Policy gradient-based methods are widely adopted in reinforcement learning. In our model, Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) is adopted.[

32] The learning objective can be written as Equation 8:

In the objective function, γ represents the discount factor, and its value is experimentally set to 0.98. The clip value, denoted as ε, is set to 0.1. The superscript k denotes for the generative model obtained after the last round of training. The estimated advantage function incorporates a learnable value function b. The value function takes the same molecular graph embedding obtained from the GCN layers and maps it to a scalar representing the estimated expected reward. The probability of an action taken by the generative model with parameter θ under state , denoted as , is calculated using Equation 2.

Results and Discussion

Comparison of Generative Models Based on Different Algorithms

The several generative models developed in our study were trained on the ZINC 250k data set in order to generate valid molecular graphs. To evaluate the performance of these models in this aspect, metrics encompassing validity, uniqueness, and novelty were considered. These metrics were assessed based on a sample of 50,000 molecules generated by each model.

The validity of the generated molecules remained as 100% across all models (

Table 3), which should be attributed to the step-by-step valency check enabled during graph generation. In contrast to SMILES-based models, which might encounter validity issues due to syntax problems, graph-based generative models benefit from a more natural representation of molecular structures, ensuring high validity. However, validity check by RDKit does not guarantee drug-like molecular structures (

Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). To address this issue, we have implemented several additional substructure detections in the molecular environment in our model, including identifying cumulative alkenes and peroxyl bonds, double or triple bonds in three or four-membered rings, bridged rings formed with aromatic rings, and macro rings with eight or more members. Our analysis indicated that these additional substructure detections has led to the elimination of approximately 40% of the impractical structures generated by GCPN

origin. Besides, the BFM model was observed to have problem in ring closure (

Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). This problem aroused due to the divergent nature of breadth-first graph generation, where the generative model tended to generate molecular graphs with incomplete rings, which may be closed later after several inconsecutive actions. In contrast, GCPN and DFM models in principle can generate molecular graphs with rings in a more practical and complete manner.

Among our evaluation metrics, uniqueness reflects the fraction of non-duplicate molecules, while novelty reflects the fraction of generated molecules not presented in the training set. Our results show that BFM exhibits the lowest performance in terms of uniqueness and novelty (

Table 3). By analyzing BFM-generated molecules, we have observed that the graph generation process is prone to terminate prematurely and produce simple and duplicate structures. In order to evaluate the scaffold uniqueness and novelty presented by the molecules in the ZINC 250k data set, we extracted the Bemis-Murcko scaffolds for all of them. Our results revealed that GCPN

ours and DFM achieve similar metrics, while the performance of BFM is limited by its preference to molecules with simple structures.

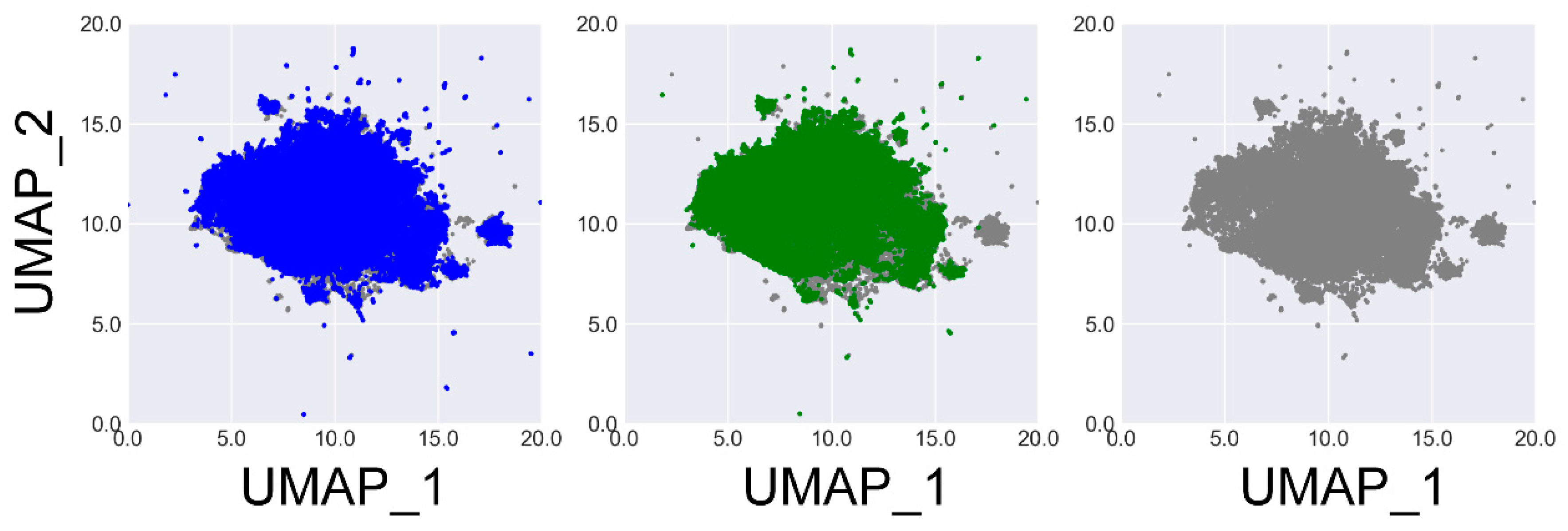

To gain a deeper understanding of the chemical space covered by the molecules generated by these several general models, we performed UMAP projection on the molecules generated by GCPN

ours and DFM, as well as 50,000 molecules randomly selected from the ZINC 250k data set. Here, UMAP analysis was performed with the umap-learn Python package.[

35] Molecules were represented by their ECFP4 fingerprints hashed to 1024 bits. The resulting binary vectors were then reduced to 250 dimensions using principal component analysis before being projected onto two dimensions. The results are illustrated in

Figure 2. One can see that both the outcomes given by GCPN

ours and DFM effectively span the chemical space represented by the training set (i.e. ZINC 250k), indicating their comparable ability of generating diverse molecule structures.

Test Case: De Novo Design with METEOR

As discussed above, GCPNours and DFM demonstrated a remarkable advantage over BFM, this test attempted to evaluate the performance of METEORGCPN and METEORDFM within the realm of reinforcement learning. We then wanted to examine their performance in a real de novo drug design scenario. The objective here was to design ligand molecules targeting GBA, simultaneously optimizing essential properties including drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, and binding affinity to the target.

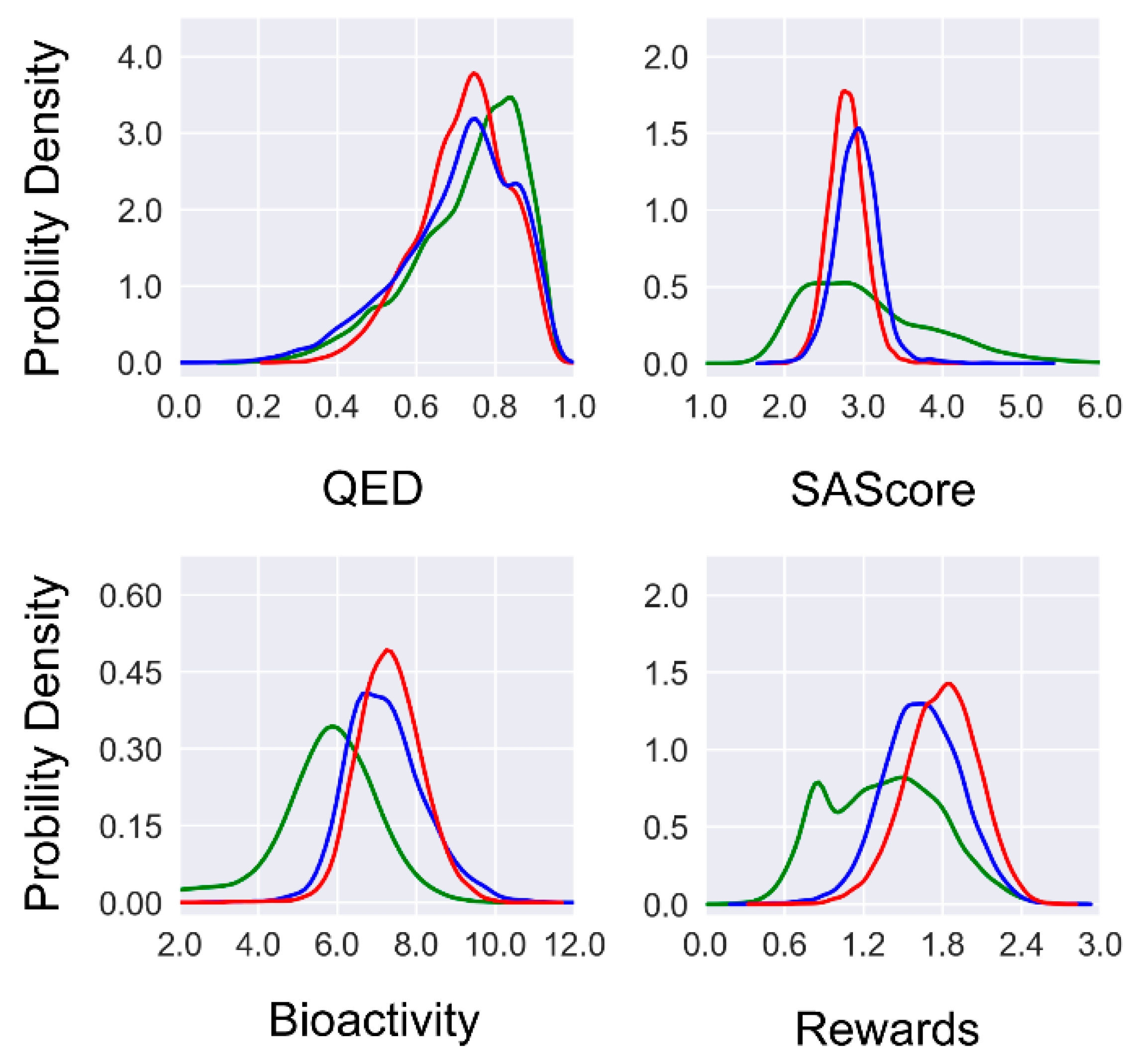

To investigate the effect of multi-objective optimization, we examined the three desired features (i.e., drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, and binding affinity) of the molecules generated at the initial round and the final round of reinforcement learning (

Figure 3). Firstly, a notable improvement in the predicted binding affinity can be observed if comparing the molecules generated by METEOR

DFM, METEOR

GCPN, and those from ZINC 250k. Regarding the QED value, a significant fraction of the molecules generated by METEOR

GCPN and METEOR

DFM (77.6% and 83.8%, respectively) exceeded the QED threshold of 0.6. Nevertheless, no notable improvement in the QED value was observed after reinforcement learning. This is because the ZINC 250k data set as a whole already exhibits a high level of QED value, leaving very limited room for further improvement. Regarding the SAScore value, the majority of ZINC 250k molecules falls within the range of (1.5, 5.0). After reinforcement learning, SAScore of the generated molecules concentrated at the range of (2.5, 3.5) with a more focused distribution. Furthermore, both models generated fewer molecules that were predicted to be challenging for synthesis as compared to the ZINC 250k molecules. Considering all three features together, the distribution of unweighted sum of three feature rewards shifted to the right as compared to the distribution of the ZINC 250k molecules. To conclude, both METEOR

DFM and METEOR

GCPN were able to generate novel molecules with improved predicted binding affinity under the constraints of drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility.

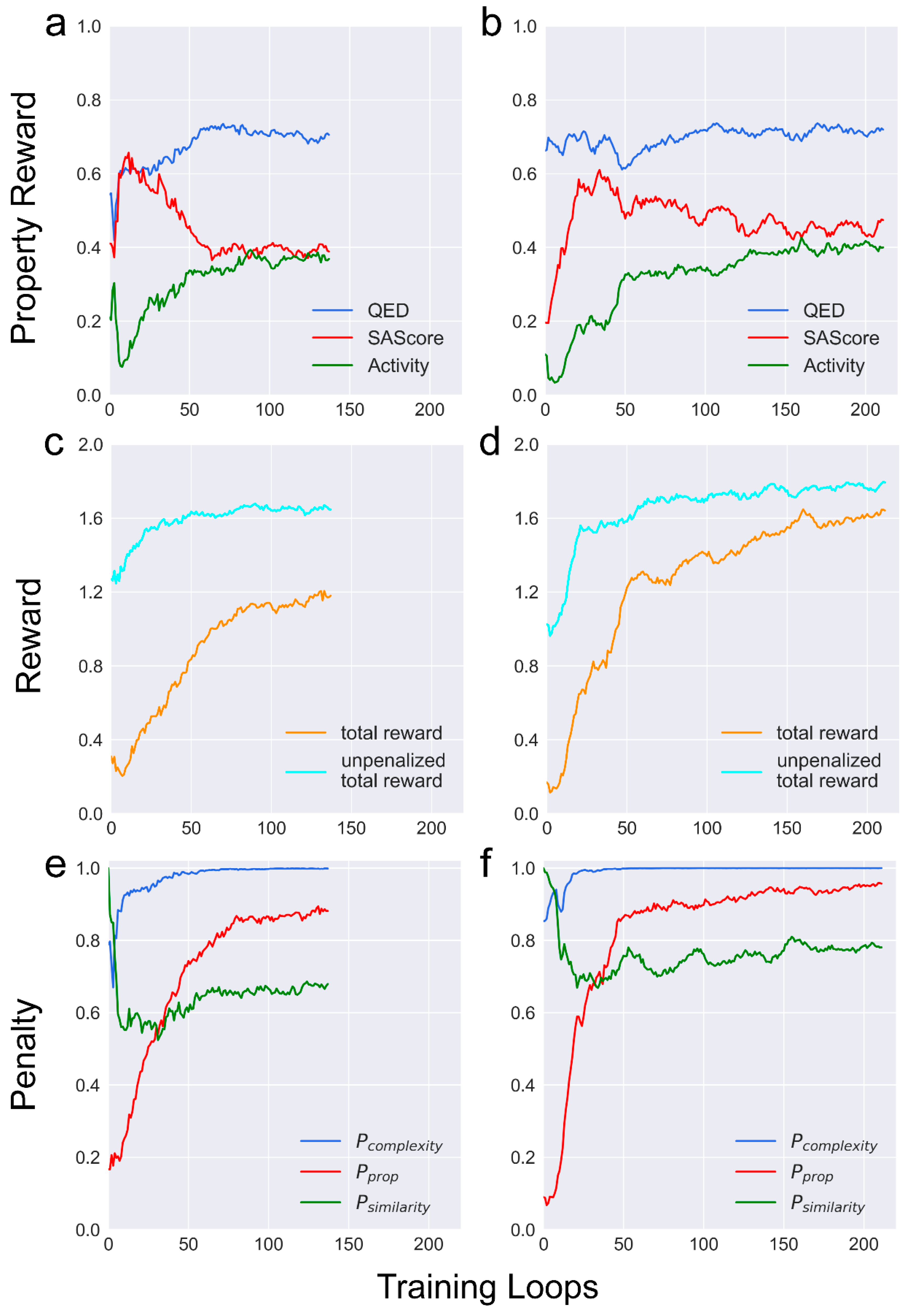

METEORGCPN: Has a Larger Action Space as Well as a Higher Learning Efficiency

Incorporating the depth-first graph traversal algorithms in DFM eliminates the need to decide the starting atom for adding a new bond. This modification reduces the action space of METEOR

DFM and theoretically streamlines reinforcement learning. However, the learning curve demonstrated that METEOR

GCPN can be trained at a higher level of stability and efficiency than METEOR

DFM in reinforcement learning (

Figure 4a and 4b). After 50 rounds of reinforcement learning, METEOR

GCPN received mean total reward around 1.25, whereas the mean total reward of METEOR

DFM at the same point was approximately 0.85. Despite the smaller action space of METEOR

DFM, the full trajectory for METEOR

DFM for generating a molecular graph is roughly twice as long as that of METEOR

GCPN. This inequality accounts for the different efficiency of METEOR

DFM and METEOR

GCPN. For example, over a three-day period of reinforcement learning, METEOR

GCPN generated around 2.7 million molecules across 212 rounds, whereas METEOR

DFM generated around 1.8 million molecules over 138 rounds. Given the same amount of training time, the additional training iterations achieved by METEOR

GCPN make it possible to uncover molecules with improved properties. Moreover, GCPN's inherent capability of determining when to terminate the graph expansion allows METEOR

GCPN to assess the attributes of the existing molecular structure. This capability empowers METEOR

GCPN to judiciously halt the expansion of a graph when the current structure exhibits particularly favorable attributes. This explains why METEOR

GCPN generated molecules with superior synthetic accessibility in comparison to METEOR

DFM.

In addition, a notable disparity was observed between the total reward and the unpenalized reward acquired by both METEOR

GCPN and METEOR

DFM (

Figure 4c and 4d). This gap primarily aroused from the property penalty at the early training phase (

Figure 4e and 4f). In METEOR, property penalty (Equation 5) was the driving force for multi-objective optimization on binding affinity to the protein, drug-likeness, and synthetic accessibility. Computing rewards by a weighted sum across three property rewards reinforced the optimization to be conducted towards all three properties.

Complexity penalty was computed primarily by counting heavy atoms. This penalty was introduced to balance the bias along structure generation, where larger molecules tend to receive higher predicted binding scores by PLANET. Moreover, larger molecules often contain challenging moieties for chemical synthesis, such as chiral centers. The similarity penalty was introduced to encourage METEOR to explore the chemical space preventing it from becoming confined to local maxima. During the initial training rounds, relatively modest similarity penalty was observed among the molecules generated by both METEOR

DFM and METEOR

GCPN due to the presence of limited high-scoring molecules recorded in the memory stack. At the 40th round or so, the influence of similarity penalties became more obvious (

Figure 4e an 4f). Here, both METEOR

DFM and METEOR

GCPN were able to explore the full chemical space covered by the ZINC 250k dataset throughout the training process without being trapped in certain restricted regions (

Figure 5).

In conclusion, both METEORDFM and METEORGCPN are able to generate molecules with optimized properties. The major distinction between METEORDFM and METEORGCPN lies in their efficiency.

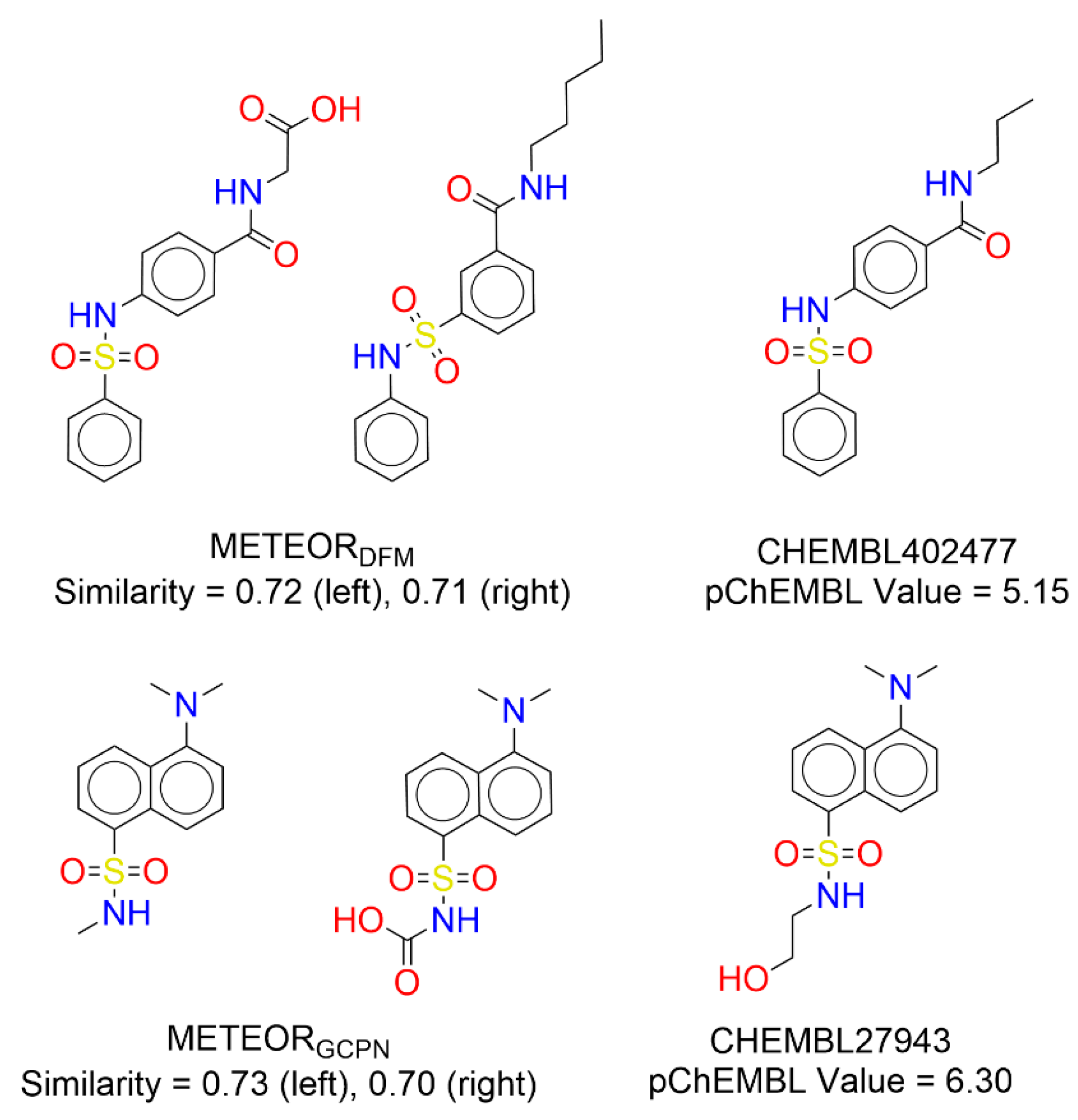

The Practical Value of METEOR in De Novo Drug Design

In this study, we evaluated the practical value of METEOR in

de novo drug design by using GBA as a test case. Quality of the molecules generated by METEOR was reflected by analyzing their similarity to true binders of GBA collected from ChEMBL. If using an ECFP4 Tanimoto coefficient of 0.6 as the threshold, 15 molecules generated by METEOR

DFM shared similar structures to true binders to GBA. As for METEOR

GCPN, this number was 17. A few such examples are given in

Figure 6. One can see that the generated molecules shared an almost identical scaffold as a certain GBA binder. This observation demonstrated that METEOR is able to generate drug-like molecules with potential value.

It should be mentioned though that as a whole, a substantial proportion of the true GBA binders considered in our study have a QED value below 0.5 or a SAScores over 3.5 (

Figure S4 in the Supporting Information). But the majority of the molecules generated by METEOR had optimized QED values and SAScores that do not stay at this range (

Figure 3). Thus, in this particular test cast, this gap resulted in rather limited matched pairs between the outcomes of METERO and true GBA binders.

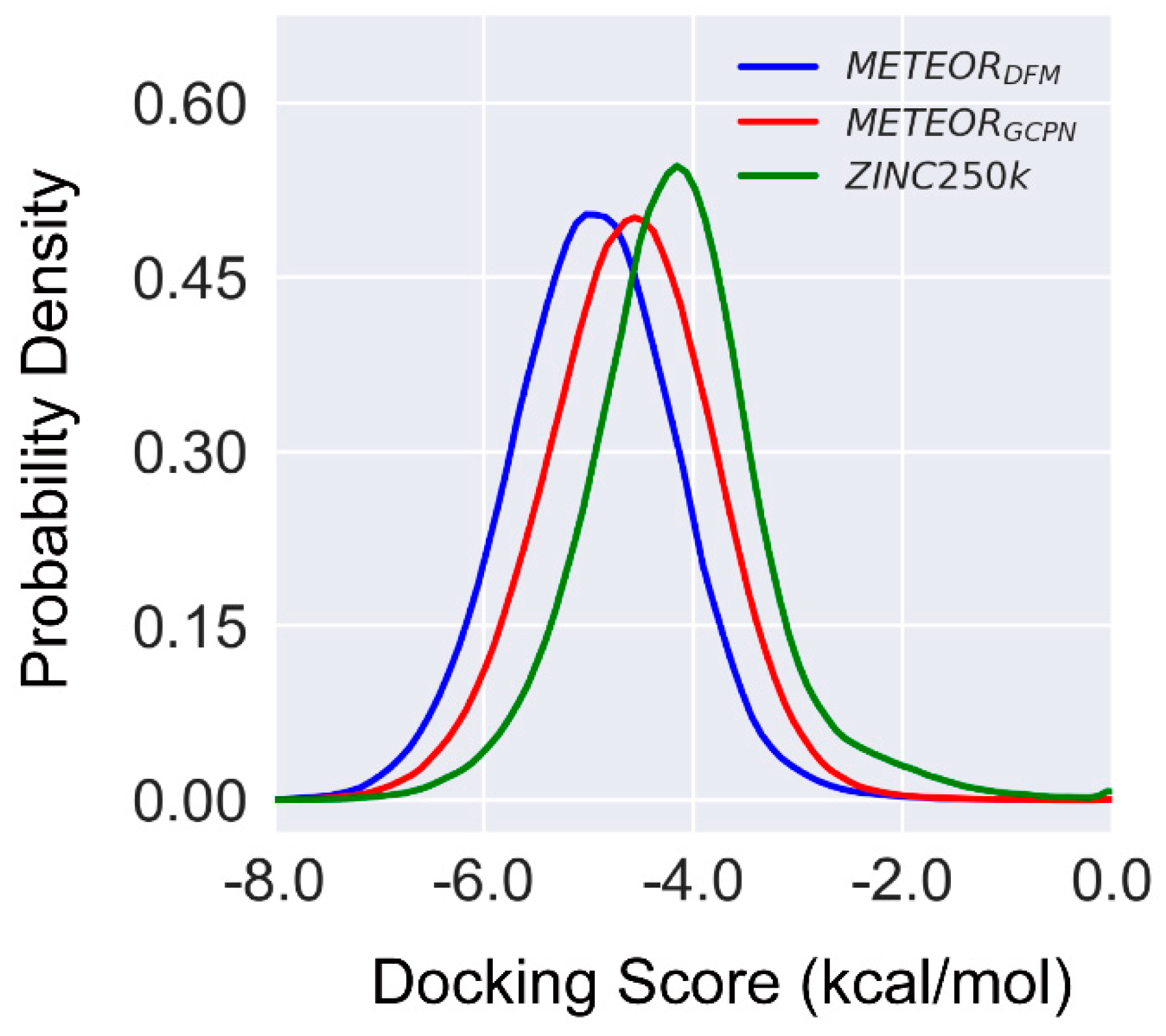

Moreover, we employed the GLIDE module in the Schrödinger software, a widely-used conventional molecule docking method, to evaluate the binding affinity of the molecules generated by METEOR with the target protein. Prior to the molecular docking job, the molecules generated during the reinforcement learning process in METEOR were filtered based on the following criteria: (1) the QED value above 0.6, (2) the SAScore lower than 3.0, and (3) the predicted binding affinity value greater than 7.0 (in -log units). The molecules meeting all requirements were then docked into the binding pocket on GBA. To make a comparison, all ZINC 250k molecules were also docked into the binding pocket on GBA through the same protocol.

As shown in

Figure 7, the molecules generated by either METEOR

GCPN or METEOR

DFM at average had better GLIDE binding scores than those ZINC 250k molecules, even though even though the optimization of binding affinity in METEOR was guided by a different scoring function PLANET. The 1% percentile of docking scores were -6.20, -6.83 and -6.57 for molecules from ZINC 250k, METEOR

DFM and METEOR

GCPN respectively. Note that besides binding affinity to the target protein, the molecule generated by METEOR were also optimized in terms of drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that more promising active hits can be discovered through application of METEOR rather than a conventional virtual screening of the ZINK 250k data set.

Conclusion

In this work, we have developed a deep learning mode, called METEOR for potential application in de novo drug design. Compared to many other generative models already described in the literature, METEOR has several distinct technical features:

Firstly, the backend agent of METEOR is based on the well-established GCPN model. To ensure the overall quality of the generated molecular graphs, we have implemented a set of rules to identify undesired substructures, which have been proven to be crucial. In fact, if these rules are not enabled, approximately 40% percent of the molecule graphs generated by METEOR would be undesirable. This demonstrates the importance of integrating chemical knowledge into molecular structure generation.

Secondly, during the development of METEOR, we evaluated several graph traversal algorithms within a reinforcement learning framework. Our findings indicate that the depth-first graph generation (DFM) outperforms breadth-first graph generation (BFM). Its outcomes closely align with those of the original GCPN model in terms of validity, uniqueness, and novelty. This observation supports the potential value of both METEORGCPN and METEORDFM to de novo drug design. In the test case of GBA, without the knowledge of true binders, both models were able to generate molecules with superior properties compared to those in the ZINC 250k data set.

Last, and very importantly, unlike many other generative models that focus on a single objective, METEOR is designed to generate molecules with optimized traits regarding binding affinity, drug-likeness, and synthetic accessibility. These several features are all crucial for the early phase of drug discovery. We believe this makes METEOR well-suited for practical drug design applications.

However, it is important to note that in the current METEOR model, drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility are evaluated with rather naïve metrics like QED and SAScore. These metrics are employed by us due to the emphasis on efficiency over accuracy within the reinforcement learning framework, where efficiency is essential to allow more computing time for roll-out and model training. The usefulness of the molecules generated by METEOR is of course limited by the effectiveness of these metrics. In the broader context of generative chemistry, generating reasonable chemical structures through an advanced training architecture is no longer the major bottleneck.[

36,

37,

38] More accurate, and preferably fast enough, computational methods for property prediction represent a greater challenge. Any significant advancements toward this direction would be highly welcomed by the scientific community.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81725022 and 82173739 to R. Wang), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (National Key Research Program, Grant No.2023YFF1205102 to Y. Li), and the Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 24ZR1413800 to Y. Li).

References

- Sterling, T.; Irwin, J.J. ZINC 15 – ligand discovery for everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 2324–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, P.; Ellis, C. Chemical space. Nature 2004, 432, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaelen, Q.; Lin, Y.-C.; Zhavoronkov, A. The advent of generative chemistry. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, T.; Correia, J.; Pereira, V.; Rocha, M. Generative deep learning for targeted compound design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 5343–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atance, S.R.; Diez, J.V.; Engkvist, O.; Olsson, S.; Mercado, R. De novo drug design using reinforcement learning with graph- based deep generative models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 4863–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arus-Pous, J.; Johansson, S.V.; Prykhodko, O.; Bjerrum, E.J.; Tyrchan, C.; Reymond, J.L.; Chen, H.; Engkvist, O. Randomized SMILES strings improve the quality of molecular generative models. J. Cheminform. 2019, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, B.; Goel, M.; Priyakumar, U.D. Modern machine learning for tackling inverse problems in chemistry: molecular design to realization. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 5316–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.X.; Liu, B.W.; Ying, R.; Pande, V.; Leskovec, J. Graph convolutional policy network for goal-directed molecular graph generation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 6410–6421. [Google Scholar]

- Mariya, P.; Mykhailo, S.; Junier, O.; Olexandr, I. MolecularRNN: generating realistic molecular graphs with optimized properties. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.; Giblin, K.A.; Janet, J.P.; Patronov, A.; Engkvist, O. De novo design with deep generative models based on 3D similarity scoring. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 44, 116308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshunova, M.; Huang, N.; Capuzzi, S.; Radchenko, D.S.; Savych, O.; Moroz, Y.S.; Wells, C.I.; Willson, T.M.; Tropsha, A.; Isayev, O. Generative and reinforcement learning approaches for the automated de novo design of bioactive compounds. Commun. Chem. 2022, 5, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicho, M.; Luukkonen, S.; van den Maagdenberg, H.W.; Schoenmaker, L.; Beiquignon, O.J.M.; van Westen, G.J.P. DrugEx: deep learning models and tools for exploration of drug-like chemical space. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 3629–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, K.; Huang, J. A simple way to incorporate target structural information in molecular generative models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 3719–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, T.; Engkvist, O.; Bajorath, J.; Chen, H.M. Memory-assisted reinforcement learning for diverse molecular de novo design. J. Cheminform. 2020, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivecrona, M.; Blaschke, T.; Engkvist, O.; Chen, H.M. Molecular de-novo design through deep reinforcement learning. J. Cheminform. 2017, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhavoronkov, A.; Ivanenkov, Y.A.; Aliper, A.; Veselov, M.S.; Aladinskiy, V.A.; Aladinskaya, A.V.; Terentiev, V.A.; Polykovskiy, D.A.; Kuznetsov, M.D.; Asadulaev, A.; et al. Deep learning enables rapid identification of potent DDR1 kinase inhibitors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1038–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokaya, M.; Imrie, F.; van Hoorn, W.P.; Kalisz, A.; Bradley, A.R.; Deane, C.M. Testing the limits of SMILES-based de novo molecular generation with curriculum and deep reinforcement learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazuz, E.; Shtar, G.; Shapira, B.; Rokach, L. Molecule generation using transformers and policy gradient reinforcement learning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilodeau, C.; Jin, W.; Jaakkola, T.; Barzilay, R.; Jensen, K.F. Generative models for molecular discovery: recent advances and challenges. Wires. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Dai, L.; Huang, W.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, S.; Lei, J.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y. DRlinker: Deep Reinforcement Learning for Optimization in Fragment Linking Design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 5907–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wengong, J.; Regina, B.; Tommi, J. Multi-Objective Molecule Generation using Interpretable Substructures. ArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janet, J.P.; Ramesh, S.; Duan, C.; Kulik, H.J. Accurate Multiobjective Design in a Space of Millions of Transition Metal Complexes with Neural-Network-Driven Efficient Global Optimization. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneiding, H.; Nova, A.; Balcells, D. Directional multiobjective optimization of metal complexes at the billion-system scale. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2024, 4, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercado, R.; Bjerrum, E.J.; Engkvist, O. Exploring graph traversal algorithms in graph-based molecular generation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 2093–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y.; Wang, R. PLANET: a multi-objective graph neural network model for protein–ligand binding affinity prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 64, 2205–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvenaud, D.; Maclaurin, D.; Aguilera-Iparraguirre, J.; Gómez-Bombarelli, R.; Hirzel, T.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; Adams, R.P. Convolutional networks on graphs for learning molecular fingerprints. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 2, 2224–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Kearnes, S.; McCloskey, K.; Berndl, M.; Pande, V.; Riley, P. Molecular graph convolutions: moving beyond fingerprints. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.; Koltun, V. Guided policy search. Proc. Mach. Learn. 2013, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ertl, P.; Schuffenhauer, A. Estimation of synthetic accessibility score of drug-like molecules based on molecular complexity and fragment contributions. J. Cheminform. 2009, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerton, G.R.; Paolini, G.V.; Besnard, J.; Muresan, S.; Hopkins, A.L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Nguyen, V.-K.; Jacquemard, C.; Rognan, D. LIT-PCBA: an unbiased data set for machine learning and virtual screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 4263–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brumshtein, B.; Greenblatt, H.M.; Butters, T.D.; Shaaltiel, Y.; Aviezer, D.; Silman, I.; Futerman, A.H.; Sussman, J.L. Crystal structures of complexes of N-butyl- and N-nonyl-deoxynojirimycin bound to acid β-glucosidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 29052–29058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneiding, H.; Balcells, D. Augmenting genetic algorithms with machine learning for inverse molecular design. Chem. Sci 2024, 15, 15522–15539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Fiscato, M.; Segler, M.H.S.; Vaucher, A.C. GuacaMol: Benchmarking Models for de Novo Molecular Design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 1096–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.H. A graph-based genetic algorithm and generative model/Monte Carlo tree search for the exploration of chemical space. Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 3567–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).