1. Introduction

The drug discovery process is notoriously lengthy and expensive. Current estimates suggest that discovering a new drug using traditional methodologies costs approximately

$2.6 billion and can take over 10 years to complete [

1]. Consequently, pharmaceutical companies are keenly focused on reducing costs and accelerating the development timeline. The primary aim of drug discovery is to find compounds with the desired properties that can be approved as drugs and fit within the extensive chemical space of potential drug-like molecules, which ranges from

to

[

2]. Recently, deep learning (DL) has emerged as a powerful tool to tackle this challenge by enabling the design of diverse compounds with optimal drug properties [

3]. Having demonstrated substantial progress in fields like natural language processing and image recognition, DL is now being increasingly applied to drug discovery and other related fields [

4]. This application has opened new avenues for computational methods in identifying potential drug candidates and optimizing their properties.

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has shown tremendous potential in molecular generation. Specifically, deep learning is used to extract features from high-dimensional data, enhancing the representational capabilities of the model, while reinforcement learning continuously optimizes the decision-making process through a trial-and-error mechanism, enabling the model to generate molecules with specific biological activities [

5]. The advantage of using DRL lies in its ability to effectively navigate vast chemical spaces and discover novel compounds with desired properties [6, 7].

Realizing the full potential of DRL in molecular generation requires selecting the appropriate reinforcement learning (RL) algorithm. Popova et al. proposed the ReLeaSE method, by combining a stack-augmented RNN (StackRNN) generative model with the reinforcement learning, REINFORCE algorithm, to generate SMILES strings with specific physical and biological properties [

8]. Olivecrona et al. developed a molecular design method that integrates a three-layer recurrent neural network (RNN) with the REINFORCE algorithm to generate SMILES strings, optimized for specific pharmacological and physical properties using policy gradient methods and reward functions [

9]. Representing molecules using SMILES strings involves a neural network generating a sequence of characters, with each character treated as an action within the RL framework. When a valid SMILES string exhibiting specific desired characteristics is produced, the RL reward function provides feedback, guiding the network to optimize outputs based on molecular properties such as binding affinity, toxicity, and stability. The MoIDQN method optimized multiple molecular properties (e.g., logP and drug-likeness) by combining reinforcement learning techniques (double Q-learning and randomized value functions) [

10]. Hu proposed a method combining Bayesian Neural Networks (BNN) with Deep Q-Learning (DQN) for molecule optimization, this approach enhances decision accuracy in selecting optimal actions, resulting in molecules with higher quality and diversity [

11]. Pereira et al. developed a molecular generation framework based on the SMILES representation, adopting the REINFORCE algorithm to generate molecules with optimized target attributes and high diversity [

5]. These methods share several common limitations. They tend to exhibit high variance during training, leading to instability in generated results. Additionally, these algorithms have low sample efficiency, requiring large amounts of data and extensive training time to stabilize policy updates, which significantly diminishes predictive accuracy and generalization in data-scarce environments. Furthermore, they struggle to balance exploration and exploitation, often falling into local optima and failing to identify global optimal solutions.

In this work, we address these problems by utilizing Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm within the DRL framework for molecular generation. PPO was selected due to its ability to maintain training stability and efficiency [

12]. By constraining step size during updates, PPO minimizes fluctuations and high variance, enhancing training stability [

13]. It allows for frequent policy updates, ensuring a smooth and efficient training process [

14]. Importance sampling and clipping strategies improve sample efficiency, enabling faster convergence and high-quality molecule generation with less data, thereby reducing training resource consumption [

15]. Additionally, PPO balances exploration and exploitation through policy clipping, preventing local optima and increasing the likelihood of discovering globally optimal solutions [

12].

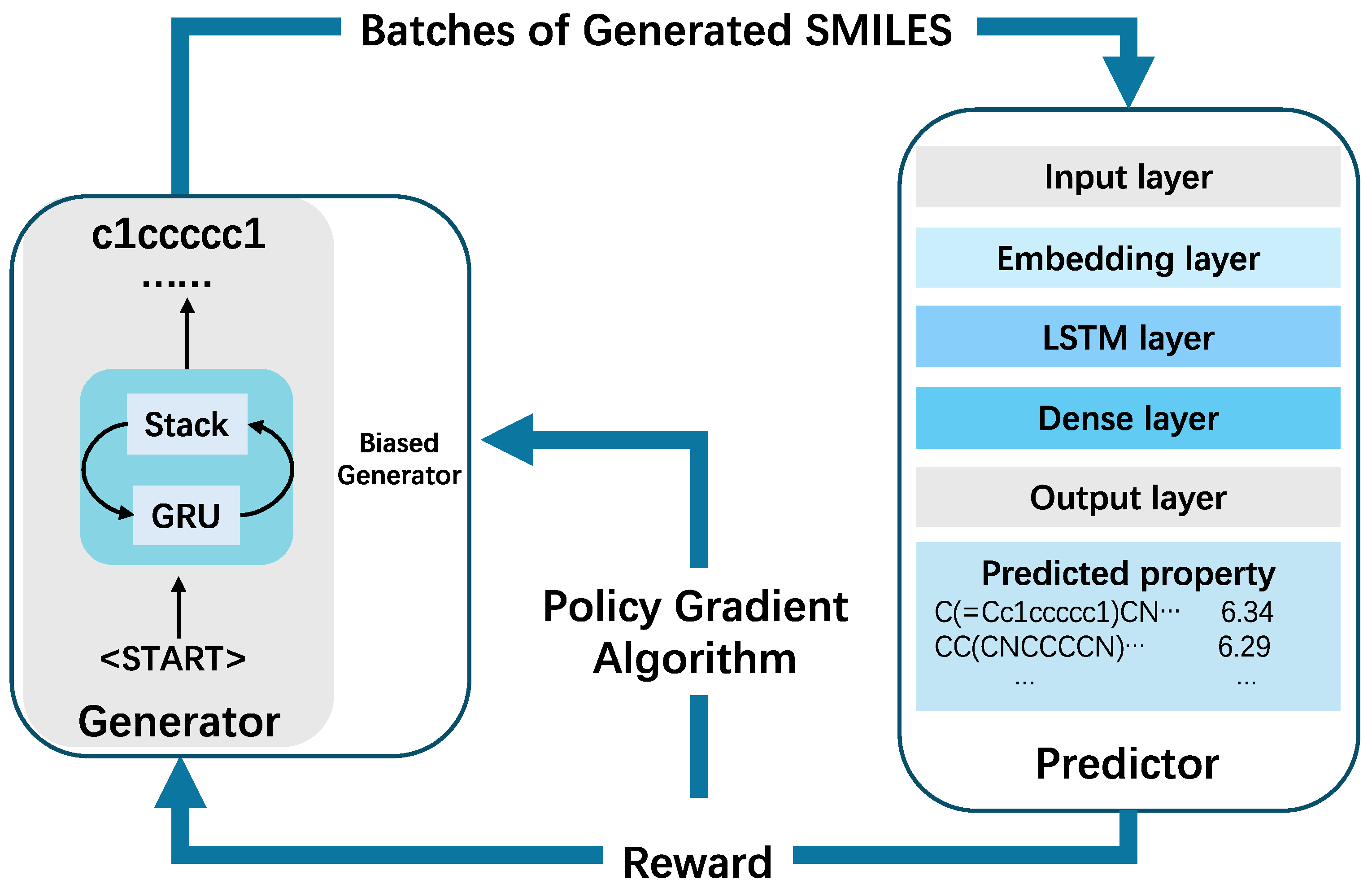

This paper proposes an end-to-end DRL framework, termed PSQ, structured with Stacked RNNs, SMILES notation, QSAR and a policy gradient PPO algorithm. The PSQ framework is designed to create molecules with optimized properties while maintaining high diversity.

2. Methods

The proposed PSQ method is divided into two stages. During the first stage, both StackRNN and QSAR models are trained separately with supervised learning algorithms. The StackRNN as generative model is trained to learn the building rules of molecules using SMILES notation, and QSAR as predictive model is trained to predict specific biological activities compounds. In the second stage, both two deep neural networks are trained jointly with an RL approach that optimizes target properties. In this process, the generative model acts as an agent responsible for creating novel, chemically feasible molecules. Meanwhile, the predictive model serves as a critic, assessing the properties of these generated compounds. The critic assigns a numerical reward (or penalty) to each molecule, based on its predicted properties. This reward guides the agent's behavior, and the generative model is trained to maximize the expected reward, thereby optimizing the quality and desirability of the generated molecules.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow of the framework for targeted molecule generation.

2.1. Reinforcement Learning of Molecule Design

RL is employed to address and solve the problem by enabling agents to use learning strategies that maximize returns or achieve specific goals during interactions with the environment. The PPO algorithm was used to implement the DRL framework, aiming to train the generator to produce a chemical space for molecules with desired properties. Both generative () and predictive () models are combined into the PPO reinforcement learning framework to optimize the generation of SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings, which are commonly used to represent chemical structures in drug discovery.

The action set comprises all letters and symbols utilized in the SMILES notation, such as carbon (C), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), hydrogen (H), and various bond types (single, double, triple, and aromatic bonds). This comprehensive action set ensures that the generative model can select the appropriate character at each step, progressively constructing a complete SMILES string. For instance, the aspirin molecule can be represented by the SMILES string CC(O)OC1CCCCC1C(O)O, which includes elements like carbon and oxygen, as well as ring structures (C1CCCCC1).

The state set encompasses all possible strings composed of the alphabet, with lengths ranging from zero to a specified maximum . The initial state of length zero serves as the unique starting point. Each training episode commences from , with the generative model incrementally adding characters until reaching a terminal state characterized by strings of length , marking the end of a training episode. The subset of terminal states of includes all states with length . This approach allows the system to explore all potential molecular representations within a fixed length range. The reward function is designed to assess the quality of the generated SMILES strings at the terminal state . All intermediate state rewards for are set to zero to avoid premature evaluation of incomplete molecules: Rewards are computed only upon completion of the generation, and this strategy focuses the system on producing complete and valid molecular representations.

In this framework, the generative model

acts as the policy approximation model. At each time step

, where

,

takes the previous state

as input and estimates the probability distribution

for the next action

:

The subsequent action is then sampled from this probability distribution and appended to the current state, generating a new partial SMILES string. For example, if the previous state is the partially generated SMILES string "CC(O)", the model estimates the probabilities of selecting the next character, such as "O", "C", or others.

The predictive model

plays a crucial role in evaluating the properties of the generated SMILES strings and providing feedback on their chemical properties. The reward

at the terminal state is a function of these predicted properties:

where

is a task-specific function that evaluates the quality of the SMILES string

based on the predictions from the predictive model

.

The PPO algorithm iteratively optimizes the policy parameters

through a series of key steps. The generative model

samples a batch of molecular structures using the current policy

. The predictive model

then assesses these structures and provides corresponding reward values

. The PPO algorithm updates the policy parameters

by maximizing the expected reward while constraining the update step to ensure stability. The objective function incorporates a clipping mechanism to prevent excessively large updates, maintaining the balance between exploration and exploitation. The optimization goal is formalized as:

where

represents the set of all possible terminal states. Through this iterative process, the generative model continuously refines its policy, leading to the generation of molecular structures with desired properties as assessed by the predictive model.

2.2. Proximal Policy Optimization

The PPO algorithm plays a pivotal role in optimizing the policy by maximizing the expected reward while maintaining stability and robustness during training. The core of the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm lies in optimizing the policy parameters

using policy gradient methods, with the objective of maximizing the expected cumulative reward

:

where

denotes a trajectory,

is the parameterized policy,

is the discount factor, and

is the reward function.

The PPO employs a surrogate objective function

that penalizes substantial policy deviations. This objective function is defined as:

where

represents the probability ratio between the new and old policies:

and

is the advantage estimate at time step

. The clipping function

ensures that the probability ratio remains within the range

to prevent large policy updates:

Algorithm 1 delineates the essential steps of the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm, focused on optimizing policy parameters

. The algorithm iteratively collects trajectories, computes returns and advantages, and performs gradient ascent on a clipped objective to update the policy. This clipping mechanism ensures stability by constraining probability ratios. The process continues until convergence, resulting in optimized policy parameters that effectively balance exploration and exploitation in reinforcement learning.

| Algorithm 1. PPO |

Input: an initialized policy and value function

for k=1 to epoch Set

Collect trajectories from

Compute returns and advantages using

for each minibatch in : Compute probability ratio

Compute clipped objective:

Perform gradient ascent on to update

end for

end for

Output: Optimized policy

|

2.3. Generative Model

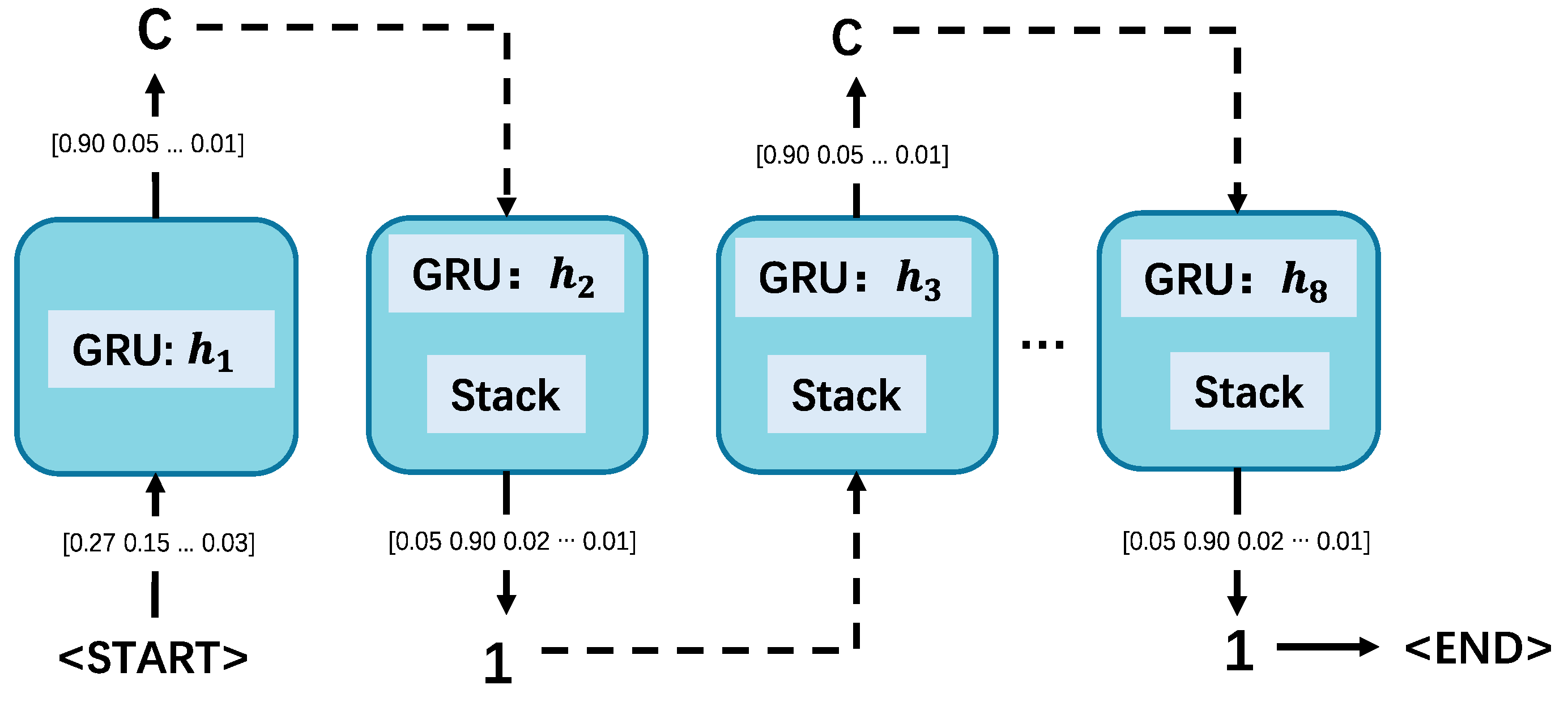

The generative model employed is a generative RNN that outputs molecules in SMILES notation (

Figure 2). We specifically use a stack-augmented RNN (Stack-RNN), known for its effectiveness in identifying algorithmic patterns [

16]. In our implementation, valid SMILES strings, which represent chemically feasible molecules, are treated as sequences of SMILES characters. The Stack-RNN's objective is to learn the underlying rules for forming these sequences, ensuring the generation of valid SMILES strings.

The Stack-RNN builds upon the standard GRU cell by incorporating two additional multiplicative gates, known as the memory stack. This structure enhances the model's ability to capture meaningful long-range dependencies. The stack memory functions as a persistent storage that retains information to be used by the hidden layer in subsequent time steps. This type of memory can be accessed only through its topmost element. The stack supports three operations: POP, which removes the top element; PUSH, which adds a new element to the top; and NO-OP, which leaves the stack unchanged. The top element of the stack has value

and is stored at position

when

, a new element

is added to the top of the stack, pushing previous elements down by one position. If

, the top element of the stack is removed, and the remaining elements are shifted up by one position. If

, the stack remains unchanged. These operations enable dynamic and flexible management of the stack memory, crucial for capturing complex dependencies in sequential data.

Now, the hidden layer

is updated as

where

is the matrix and

represents the top element of the stack at time step

. The matrix

integrates this stack element into the hidden layer update, allowing the model to leverage stack memory for capturing complex dependencies in sequential data [

8].

During the training phase, we pre-trained a generative model on the ChEMBL dataset [

17], consisting of approximately 1.5 million drug-like compounds, to ensure the model could produce chemically feasible molecules. This phase did not incorporate any property optimization. The neural network architecture featured a GRU layer with 1500 units [

18] and a stack augmentation layer with 512 units. Training was carried out on a GPU over 10,000 epochs.

The generative model operates in two modes: training and generating. In training mode, at each time step, the network processes the current prefix of the training sequence and predicts the probability distribution of the next character. The predicted character is sampled from this distribution and compared to the actual character, allowing the calculation of the cross-entropy loss. This loss is then used to update the model parameters. In generating mode, the network uses the prefix of the already generated sequences to predict and sample the next character's probability distribution. Unlike in training mode, the model parameters remain unchanged during generation.

Figure 2.

The outline of producing the SMILES string ‘C1CCCCC1’. For each step, the input character is processed by the GRU to generate a new hidden state, followed by an output probability distribution, selecting the output character, performing stack operations, and updating the input for the next time step.

Figure 2.

The outline of producing the SMILES string ‘C1CCCCC1’. For each step, the input character is processed by the GRU to generate a new hidden state, followed by an output probability distribution, selecting the output character, performing stack operations, and updating the input for the next time step.

2.4. Predictive Model

The predictor is a QSAR model designed to estimate the physical, chemical, or biological properties of molecules. This deep neural network, based on the study by Popova et al.[

8], includes an embedding layer, an LSTM layer, and two dense layers. It determines user-specified properties, such as molecular activity, by using SMILES strings as input data vectors. While similar to traditional QSAR models, this approach does not require numerical descriptors. Instead, the model learns directly from the SMILES notation, effectively relating comparisons between SMILES strings to differences in target properties.

In recently years, QSAR models have been crucial in optimizing leads and predicting biological activities of compounds in drug design [

19]. Any QSAR method can generally be expressed in the form

, where

denotes the biological activity or property of interest,

represent the molecular descriptors. The function

captures the relationship between these descriptors and the target property, and it can take various forms, including linear and non-linear functions [

8].

The QSAR model was developed to predict the pIC50 properties for Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) inhibitors. The curated dataset was split into training and validation sets using a 5-fold cross-validation (5CV) fashion. Instead of utilizing traditional calculated chemical descriptors, this model employed SMILES representations. The model consisted of an embedding layer that transformed the sequence of discrete SMILES tokens into a vector of 100 continuous numbers, an LSTM layer with 100 units and tanh nonlinearity, a dense layer with 100 units and rectify nonlinearity function, and a final dense layer with a single unit and identity activation function. Training was performed using a learning-rate decay technique until convergence was achieved.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

To explore the utility of the PPO algorithm in a drug design setting, we conducted a case study on biological activity prediction focusing on putative inhibitors of JAK2. Specifically, we designed molecules to modulate JAK2 activity with the goal of minimizing or maximizing negative logarithm of half maximal inhibitory concentration (

) values. While most drug discovery studies focus on identifying molecules with enhanced activity, minimizing bioactivity is also crucial to mitigate off-target effects. Therefore, we aimed to explore our system's capability to bias the design of novel molecular structures toward any desired range of target properties. Janus Kinase 2 (JAK2) is a key non-receptor tyrosine kinase involved in cytokine signaling. Mutations in JAK2 are linked to myeloproliferative neoplasms, including polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelofibrosis [

20]. JAK2 inhibitors have shown significant promise in treating these conditions [

21].

The evaluation of generated molecules is crucial to ensure their potential efficacy and safety in drug development. Six specific metrics were chosen: molecular validity, molecular diversity, molecular weight distribution, biological activity distribution, functional group analysis, and pharmacophore features. These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the generated molecules from various critical perspectives.

Molecular validity ensures that the generated molecules conform to the basic rules of chemical structure, including valence rules and chemical stability, which is essential for further biological testing and development [

22]. Molecular diversity measures the variety within the set of generated molecules, indicating a broader exploration of chemical space, which is important for identifying novel compounds with unique properties [

23]. The molecular weight distribution assesses the distribution of molecular weights in the generated set, ensuring that the molecules fall within a desirable range for drug-like properties, as extreme weights (either too high or too low) can affect bioavailability and drug-likeness [

24]. Biological activity distribution evaluates the predicted biological activities of the molecules, helping to identify compounds that are likely to be effective against the target, ensuring that the generated set includes potent candidates [

25]. Functional group analysis examines the presence and frequency of functional groups within the molecules, this method is crucial for the interaction of drugs with biological targets, and their appropriate representation can influence the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the molecules [

26]. Pharmacophore features analyze the presence of essential pharmacophore features required for the interaction with the biological target, ensuring that the generated molecules have the necessary structural motifs to engage effectively with the target, increasing the likelihood of biological efficacy [

27].

3. Results and Discussion

In this section, we present a comparative analysis of molecules with minimized or maximized values for JAK2, generated using the PPO and REINFORCE algorithms. The comparison is conducted across six critical metrics: molecular validity, molecular diversity, molecular weight distribution, biological activity distribution, functional group analysis, and pharmacophore features. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness and quality of the generated molecules.

We chose to compare PPO with REINFORCE because both are prominent reinforcement learning algorithms used in generative tasks, yet they have distinct mechanisms and performance characteristics. PPO is known for its stability and efficiency due to its clipped surrogate objective function, whereas REINFORCE directly optimizes the expected return but can suffer from high variance and less stable updates. By examining these six aspects, we aim to demonstrate the advantages of the PPO algorithm in producing chemically valid, diverse, and biologically relevant molecules, highlighting its potential to enhance the drug discovery process.

3.1. Chemical Properties

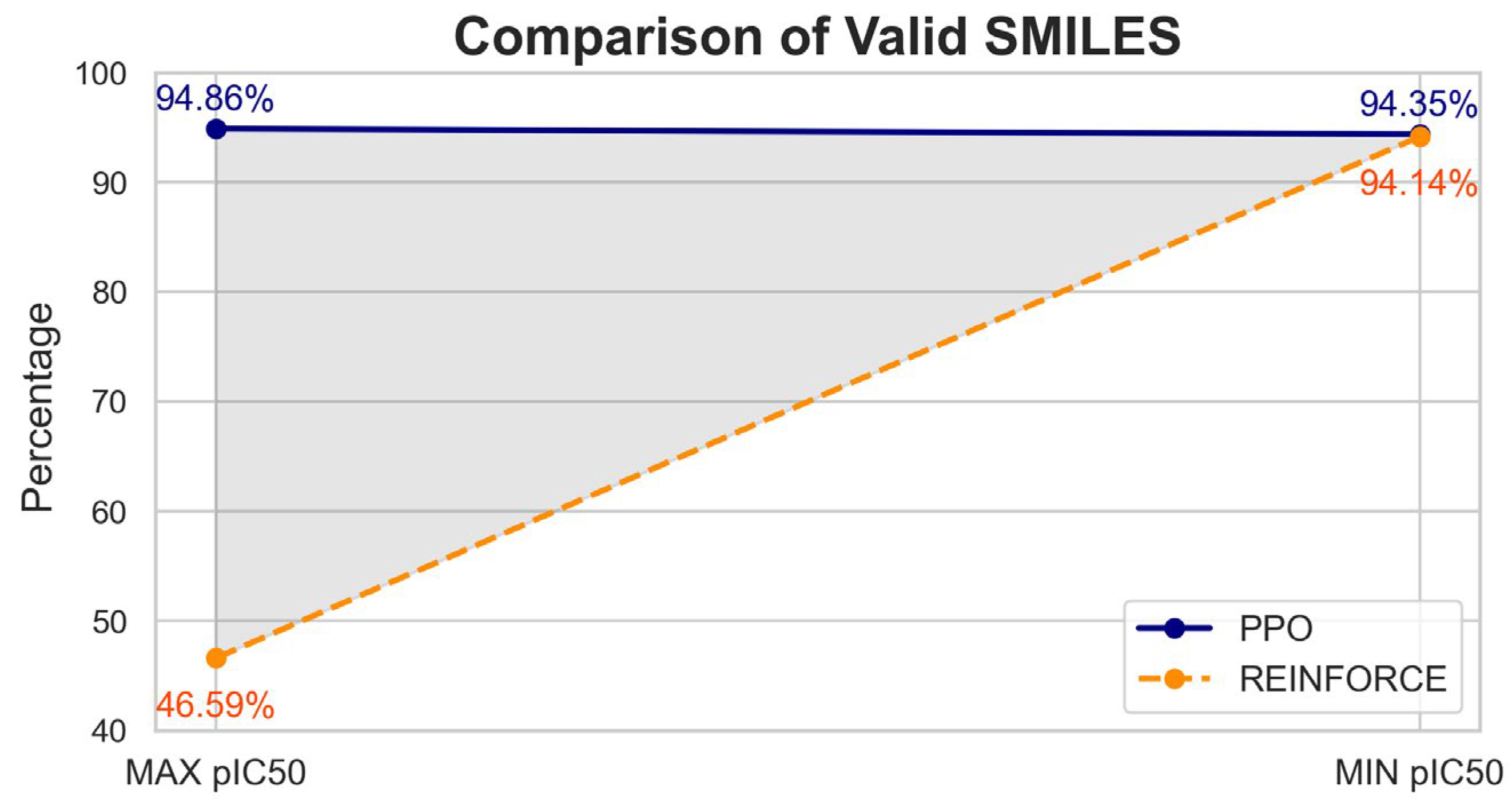

To assess the molecular validity of the generated molecules, we employed the RDKit library [

28], focusing on several critical aspects: structural parsing, chemical standardization, atom type checks, valence checks, and charge checks. This evaluation allowed us to compare the effectiveness of the PPO and REINFORCE algorithms in producing valid molecules.

The molecular validity analysis of compounds generated by PPO and REINFORCE algorithms shows significant differences (

Figure 3). For the dataset with the maximum pIC50 value, PPO achieved a validity rate of 94.86% (5551 valid out of 5852), whereas REINFORCE had a much lower validity rate of 46.59% (3902 valid out of 8376). Similarly, for the dataset with the minimum pIC50 value, PPO maintained a high validity rate of 94.35% (5565 valid out of 5898), while REINFORCE improved but still lagged with a validity rate of 93.14% (4224 valid out of 4535). Overall, PPO demonstrates superior performance in generating chemically valid compounds.

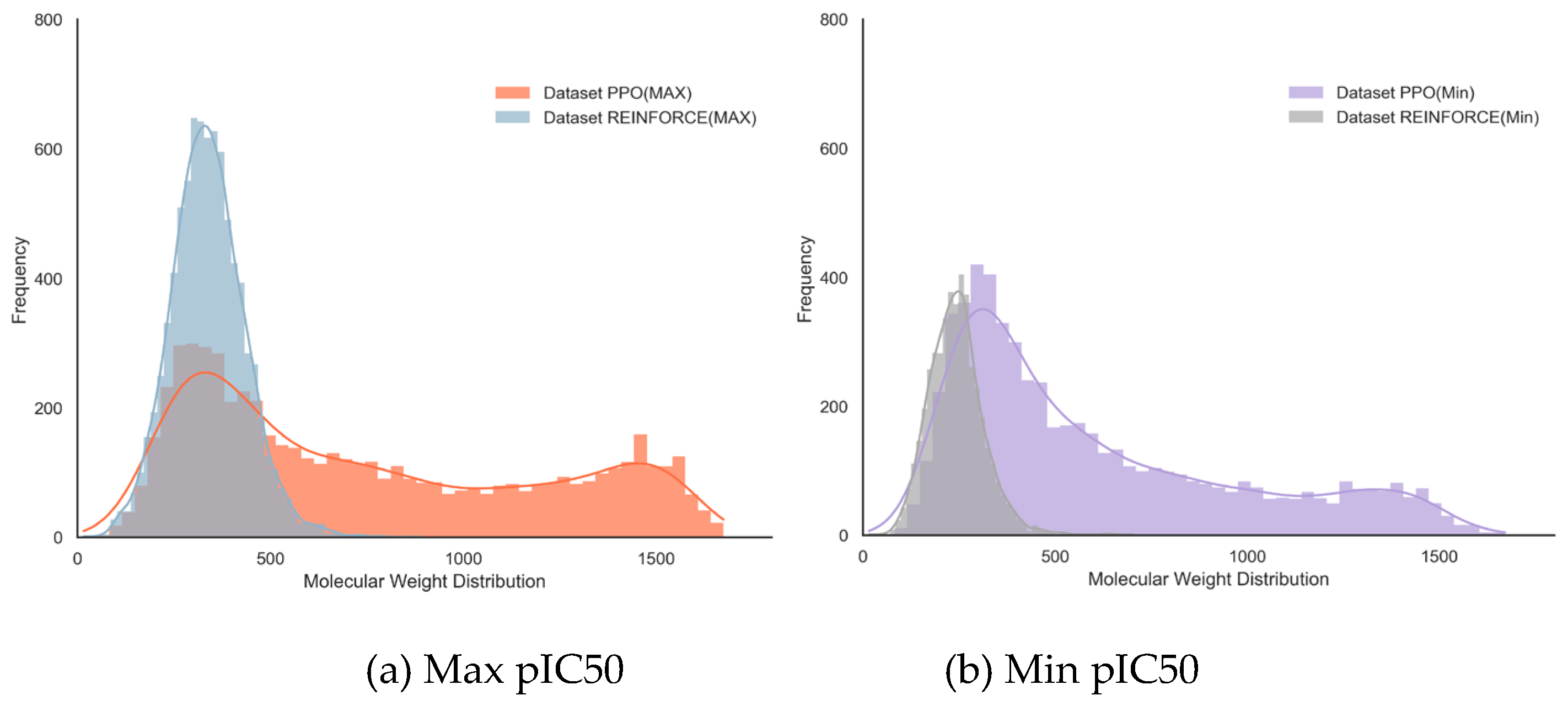

Comparing the molecules generated by the PPO and REINFORCE algorithms without controlling for molecular weight allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the overall molecular weight distribution produced by each algorithm. This approach highlights the differences in performance across various molecular weight ranges, from small to large molecules, providing a complete view of each algorithm's capabilities.

In the dataset with maximum pIC50 values (

Figure 4a), the PPO dataset has a mean molecular weight of 745.75 with a standard deviation of 446.77, indicating greater diversity and higher molecular weight; while the REINFORCE dataset has a mean molecular weight of 338.82 with a standard deviation of 95.91, showing a more concentrated distribution. In the dataset with minimum pIC50 values (

Figure 4b), the PPO dataset has a mean molecular weight of 604.49 with a standard deviation of 376.81, again indicating greater diversity; the REINFORCE dataset has a mean molecular weight of 243.90 with a standard deviation of 72.19, showing a more concentrated low molecular weight distribution. Overall, the PPO algorithm excels in generating high molecular weight and diverse compounds, while the REINFORCE algorithm is better at generating low molecular weight compounds with a concentrated distribution (

Table 1).

3.2. Diversity and Activity

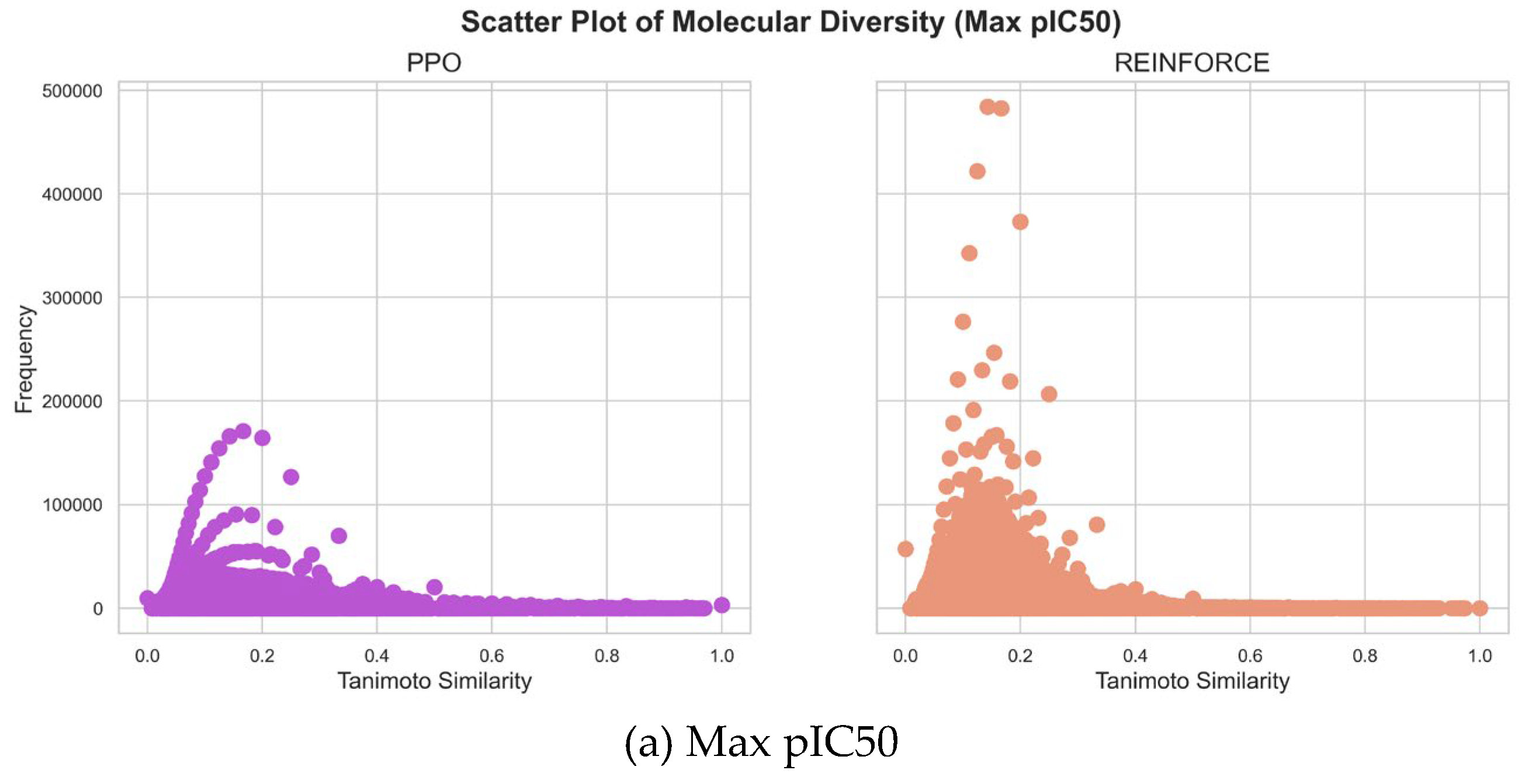

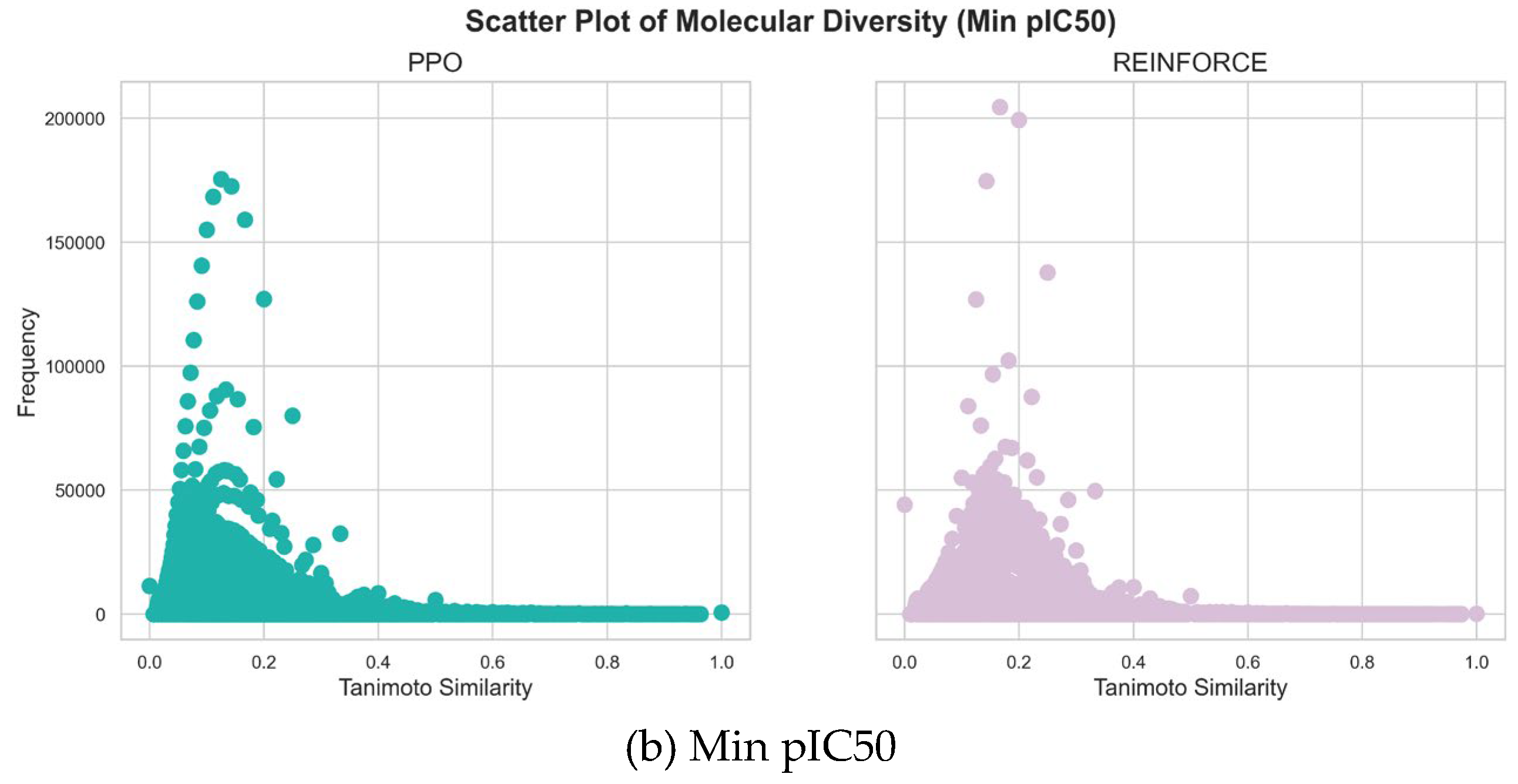

Comparing the molecular diversity generated by PPO and REINFORCE algorithms is crucial for evaluating their ability to explore chemical space and produce novel, biologically relevant structures. This comparison helps identify which algorithm generates a more diverse set of molecules, thereby enhancing the chances of discovering new drug candidates.

As shown in

Figure 5,the maximum pIC50 value datasets generated by PPO and REINFORCE algorithms show significant differences in similarity distribution. The PPO dataset has a mean similarity of 0.1572 and a standard deviation of 0.0931, indicating greater structural diversity. In contrast, the REINFORCE dataset has a mean similarity of 0.1558 and a standard deviation of 0.0717, indicating more structural similarity. The frequency of the REINFORCE dataset is higher than that of the PPO dataset in the 0.1 to 0.2 similarity range, showing that REINFORCE generates compounds more concentrated in this range. In the minimum pIC50 value datasets, the similarity distribution of the PPO dataset is mainly between 0.0 and 0.2 with a flatter spread, while the REINFORCE dataset is between 0.0 and 0.3 with higher peak frequencies. The PPO dataset's mean similarity is 0.1344, lower than REINFORCE's 0.1805, indicating greater structural diversity. PPO's standard deviation is 0.0740, slightly lower than REINFORCE's 0.0803, showing less fluctuation and a more even distribution. The PPO dataset has higher frequency in the 0.1 to 0.2 similarity range, whereas REINFORCE shows higher frequencies at higher similarity values, indicating more structural similarity. In summary, the PPO algorithm generates compounds with a wider range of structural diversity, whereas the REINFORCE algorithm tends to produce compounds concentrated within specific similarity ranges.

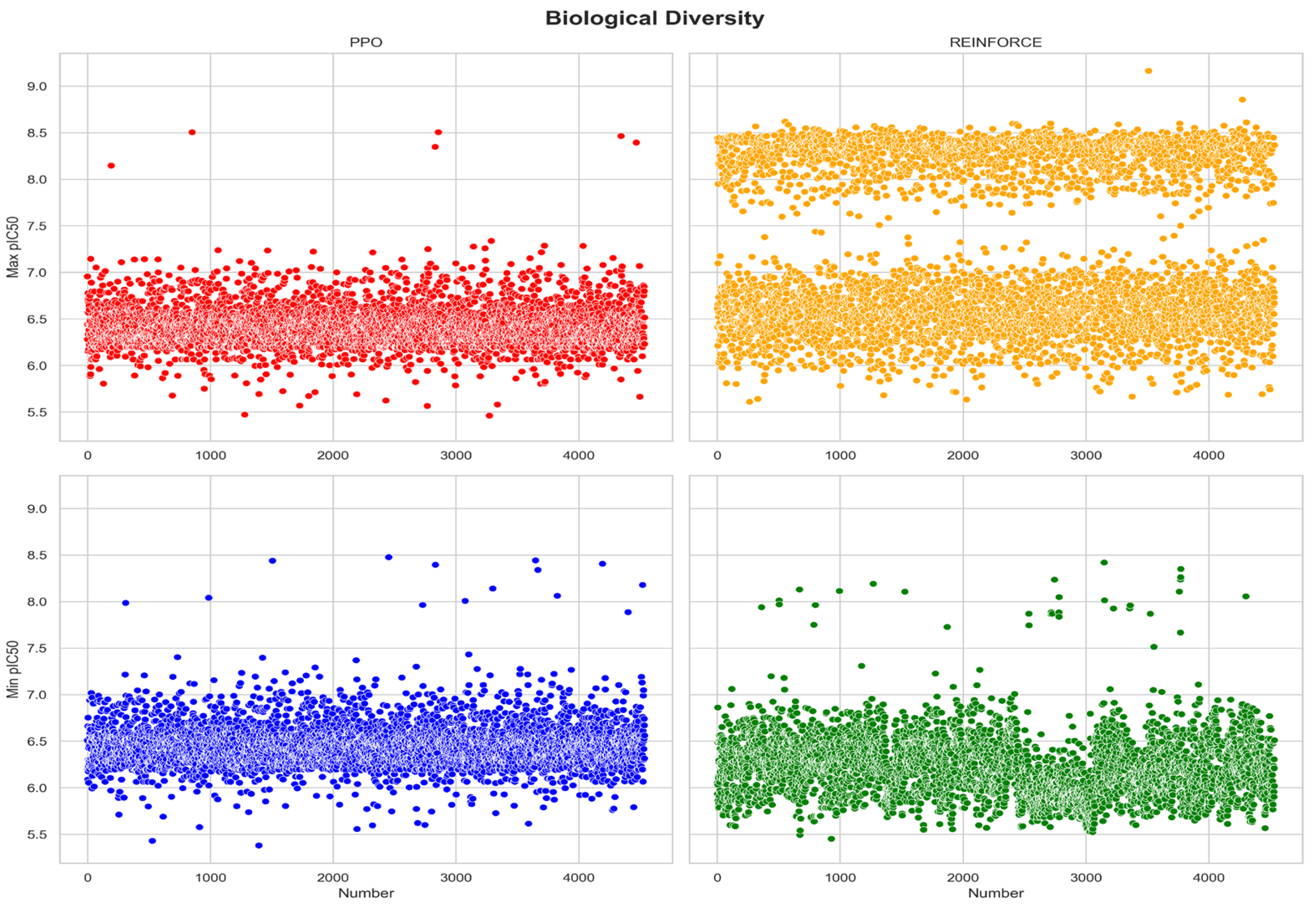

Evaluating the biological activity distribution of compounds generated by PPO and REINFORCE algorithms is essential for understanding their effectiveness in producing bioactive molecules. Compounds generated by PPO and REINFORCE algorithms show significant differences in biological activity distribution (

Figure 6). In the dataset with maximum pIC50 values, the PPO dataset has a mean pIC50 of 6.42 with a standard deviation of 0.23, indicating more consistent biological activity; whereas the REINFORCE dataset has a mean pIC50 of 7.17 with a standard deviation of 0.86, showing greater diversity in biological activity. In the dataset with minimum pIC50 values, the PPO dataset has a mean pIC50 of 6.46 with a standard deviation of 0.24, indicating high consistency; while the REINFORCE dataset has a mean pIC50 of 6.23 with a standard deviation of 0.33, indicating some diversity. Overall, compounds generated by the PPO algorithm exhibit more consistent biological activity, it is advantageous in generating compounds with more consistent biological activity (

Table 2).

3.3. Functional Analysis

Assessing the functional group in molecules generated by PPO and REINFORCE algorithms is vital for evaluating their chemical diversity and synthetic applicability. This comparison elucidates each algorithm's proficiency in generating a broad spectrum of chemically and biologically relevant structures (

Figure 7). In the dataset with maximum pIC50, the REINFORCE dataset has a significantly higher number of Phenyl groups compared to the PPO dataset, while the PPO dataset has an advantage in the number of Ether and Ketone groups. For the minimum pIC50 dataset, the REINFORCE dataset also dominates in the number of Phenyl groups, whereas the PPO dataset performs better in generating compounds with Ether and Ketone groups. Overall, the REINFORCE algorithm excels in generating compounds with Phenyl groups and greater diversity, while the PPO algorithm is better at generating compounds with Ether and Ketone groups.

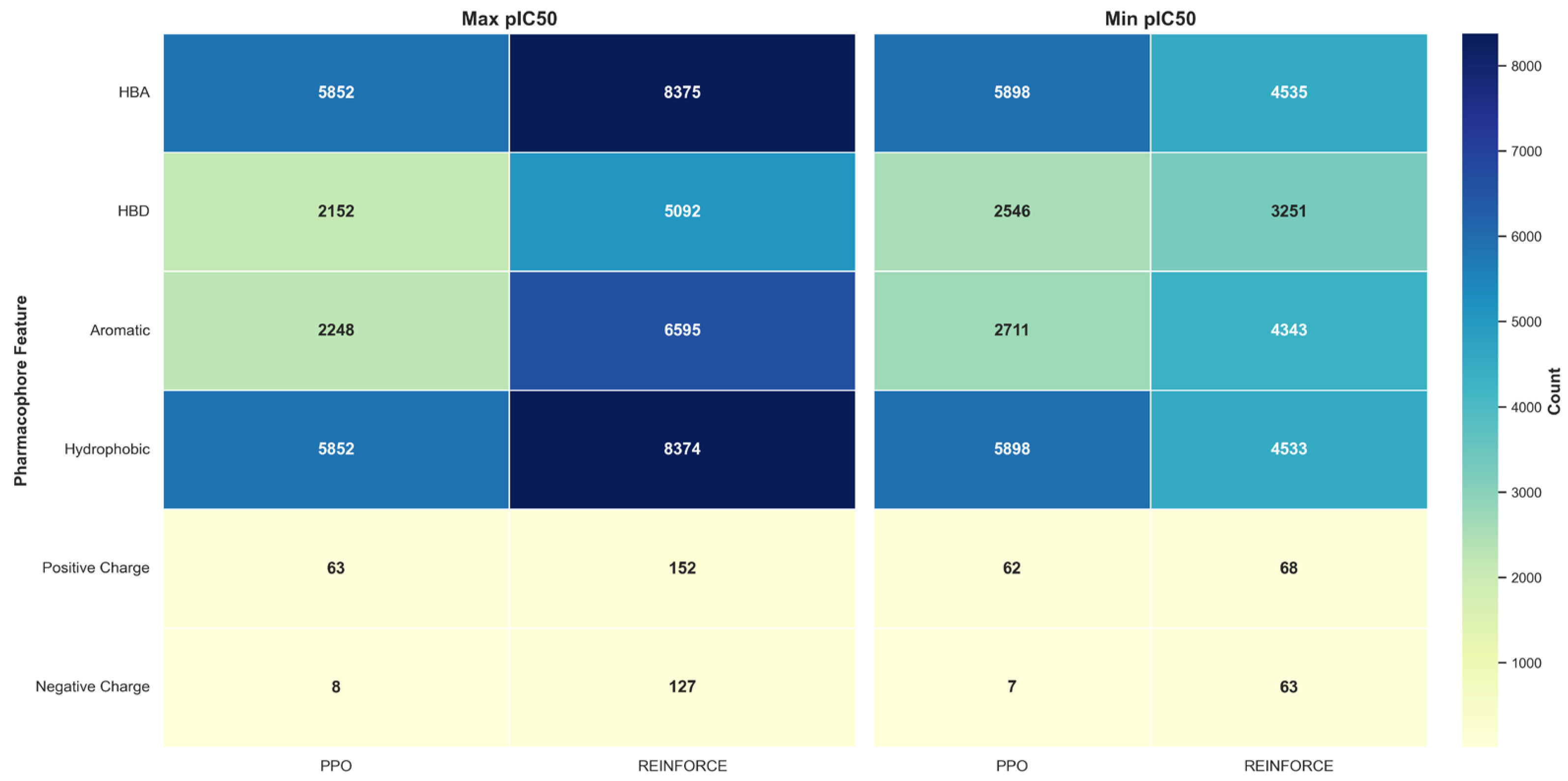

In the pharmacophore feature distribution analysis of the maximum and minimum pIC50 values, the PPO and REINFORCE datasets show significant differences. For the maximum pIC50 values, the PPO dataset has a higher proportion of HBA and Hydrophobic features, each at 36.18%. In contrast, the REINFORCE dataset excels in HBA and Hydrophobic, at 29.17% and 29.16% respectively. For the minimum pIC50 values, the PPO dataset also dominates in HBA and Hydrophobic features, each at 34.45%, while the REINFORCE dataset has a higher proportion of HBA and Hydrophobic, at 27.01% and 26.99% respectively. These differences indicate that the PPO algorithm performs better in generating compounds with HBA and Hydrophobic features.

Figure 8.

Pharmacophore feature distribution in PPO and REINFORCE generated molecules.

Figure 8.

Pharmacophore feature distribution in PPO and REINFORCE generated molecules.

4. Conclusions and Future Works

We proposed a new method by utilizing PPO algorithm within the DRL framework, termed PSQ, to enable the generation of new chemical compounds with desired properties. This methodology has demonstrated significant potential in exploring and generating specific molecules by optimizing for targeted characteristics.

The PPO algorithm's superior performance in exploring the chemical space and generating compounds with diverse pharmacophore features, functional groups, and biological activities underscores its potential in drug discovery and chemical synthesis. By systematically comparing the outputs of PPO and REINFORCE, we highlighted the robustness and efficiency of PPO in optimizing molecular properties for targeted therapeutic applications.

After creating this PSQ framework using PPO, the future work will aim to focus on optimizing the PSQ model by integrating other advanced molecular generation and predictive models to further explore the potential of the PPO algorithm in molecular design. By combining the PPO algorithm with cutting-edge techniques in molecular generation and prediction, we aim to refine these approaches, thereby making significant contributions to the field of computational drug design. This strategy will ultimately accelerate the discovery of new therapeutic agents with optimized properties, transforming drug discovery processes to be more efficient, cost-effective, and capable of addressing complex medicinal challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.Z; methodology, Y.X.; software, J.M.Z., H.T., G.E.S., D.K., and Y.X.; validation, J.M.Z. and Y.X.; formal analysis, Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.Z., H.T., G.E.S., D.K., Y.X., and M.H.J.; writing—review and editing, J.M.Z., H.T., G.E.S., D.K., Y.X., and M.H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Keputusan Rektor UB Nomor 6859 Tahun 2024 Tentang Penerima Pendanaan Adjunct Professor Tahun 2024 Batch 3.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Institute for Big Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence (IBDAAI), Universiti Teknologi MARA, the School of Computer and Information, Qiannan Normal University for Nationalities, and the Faculty of Computer Science, Universitas Brawijaya for their continuous support in this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest to this work.

References

- S. Harrer, P. Shah, B. Antony, and J. Hu, “Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Trial Design.,” Trends in pharmacological sciences, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Mullard, “The drug-maker’s guide to the galaxy,” Nature, vol. 549, no. 7673, pp. 445–447, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Sousa, J. Correia, V. Pereira, and M. Rocha, “Generative Deep Learning for Targeted Compound Design,” Journal of chemical information and modeling, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Mijwil, D. S. Mutar, E. S. Mahmood, M. Gök, S. Uzun, and R. Doshi, “Deep Learning Applications and Their Worth: A Short Review,” Asian Journal of Applied Sciences, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Pereira, M. Abbasi, B. Ribeiro, and J. P. Arrais, “Diversity oriented Deep Reinforcement Learning for targeted molecule generation,” J Cheminform, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 21, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Agyemang, W.-P. Wu, D. Addo, M. Y. Kpiebaareh, E. Nanor, and C. R. Haruna, “Deep Inverse Reinforcement Learning for Structural Evolution of Small Molecules,” Briefings in bioinformatics, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Sridharan, M. Goel, and U. Priyakumar, “Modern machine learning for tackling inverse problems in chemistry: molecular design to realization.,” Chemical communications, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Popova, O. Isayev, and A. Tropsha, “Deep reinforcement learning for de novo drug design,” Sci. Adv., vol. 4, no. 7, p. eaap7885, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Olivecrona, T. Blaschke, O. Engkvist, and H. Chen, “Molecular de-novo design through deep reinforcement learning,” J Cheminform, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 48, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhou, S. Kearnes, L. Li, R. N. Zare, and P. Riley, “Optimization of molecules via deep reinforcement learning,” Scientific reports, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 10752, 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. Hu, “Reinforcement Learning of Molecule Optimization with Bayesian Neural Networks,” Computational Molecular Bioscience, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Schulman, F. Wolski, P. Dhariwal, A. Radford, and O. Klimov, “Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms,” ArXiv, vol. abs/1707.06347, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhu and A. Rosendo, “A Functional Clipping Approach for Policy Optimization Algorithms,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 96056–96063, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhu and A. Rosendo, “Proximal Policy Optimization Smoothed Algorithm,” ArXiv, vol. abs/2012.02439, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Markowitz and E. W. Staley, “Clipped-Objective Policy Gradients for Pessimistic Policy Optimization,” ArXiv, vol. abs/2311.05846, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Joulin and T. Mikolov, “Inferring algorithmic patterns with stack-augmented recurrent nets,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 28, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Bento et al., “The ChEMBL bioactivity database: an update,” Nucleic acids research, vol. 42, no. D1, pp. D1083–D1090, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Chung, C. Gulcehre, K. Cho, and Y. Bengio, “Empirical Evaluation of Gated Recurrent Neural Networks on Sequence Modeling.” arXiv, Dec. 11, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Kwon, H. Bae, J. Jo, and S. Yoon, “Comprehensive ensemble in QSAR prediction for drug discovery,” BMC Bioinformatics, vol. 20, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Cazzola and R. Kralovics, “From Janus kinase 2 to calreticulin: the clinically relevant genomic landscape of myeloproliferative neoplasms.,” Blood, vol. 123 24, pp. 3714–9, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Tefferi, A. Pardanani, and N. Gangat, “Momelotinib (JAK1/JAK2/ACVR1 inhibitor): mechanism of action, clinical trial reports, and therapeutic prospects beyond myelofibrosis,” Haematologica, vol. 108, pp. 2919–2932, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. G. Polishchuk, T. I. Madzhidov, and A. Varnek, “Estimation of the size of drug-like chemical space based on GDB-17 data,” J Comput Aided Mol Des, vol. 27, no. 8, pp. 675–679, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Gómez-Bombarelli et al., “Automatic Chemical Design Using a Data-Driven Continuous Representation of Molecules,” ACS Cent. Sci., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 268–276, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. H. O. Donovan, C. D. Fusco, L. Kuhnke, and A. Reichel, “Trends in Molecular Properties, Bioavailability, and Permeability across the Bayer Compound Collection.,” Journal of medicinal chemistry, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Huang et al., “Biological activity-based modeling identifies antiviral leads against SARS-CoV-2,” Nature Biotechnology, vol. 39, pp. 747–753, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Ertl and T. Schuhmann, “A Systematic Cheminformatics Analysis of Functional Groups Occurring in Natural Products.,” Journal of natural products, vol. 82 5, pp. 1258–1263, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Kohlbacher, M. Schmid, T. Seidel, and T. Langer, “Applications of the Novel Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship Method QPhAR in Virtual Screening and Lead-Optimisation,” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Landrum, “Rdkit documentation,” Release, vol. 1, no. 1–79, p. 4, 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).