Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

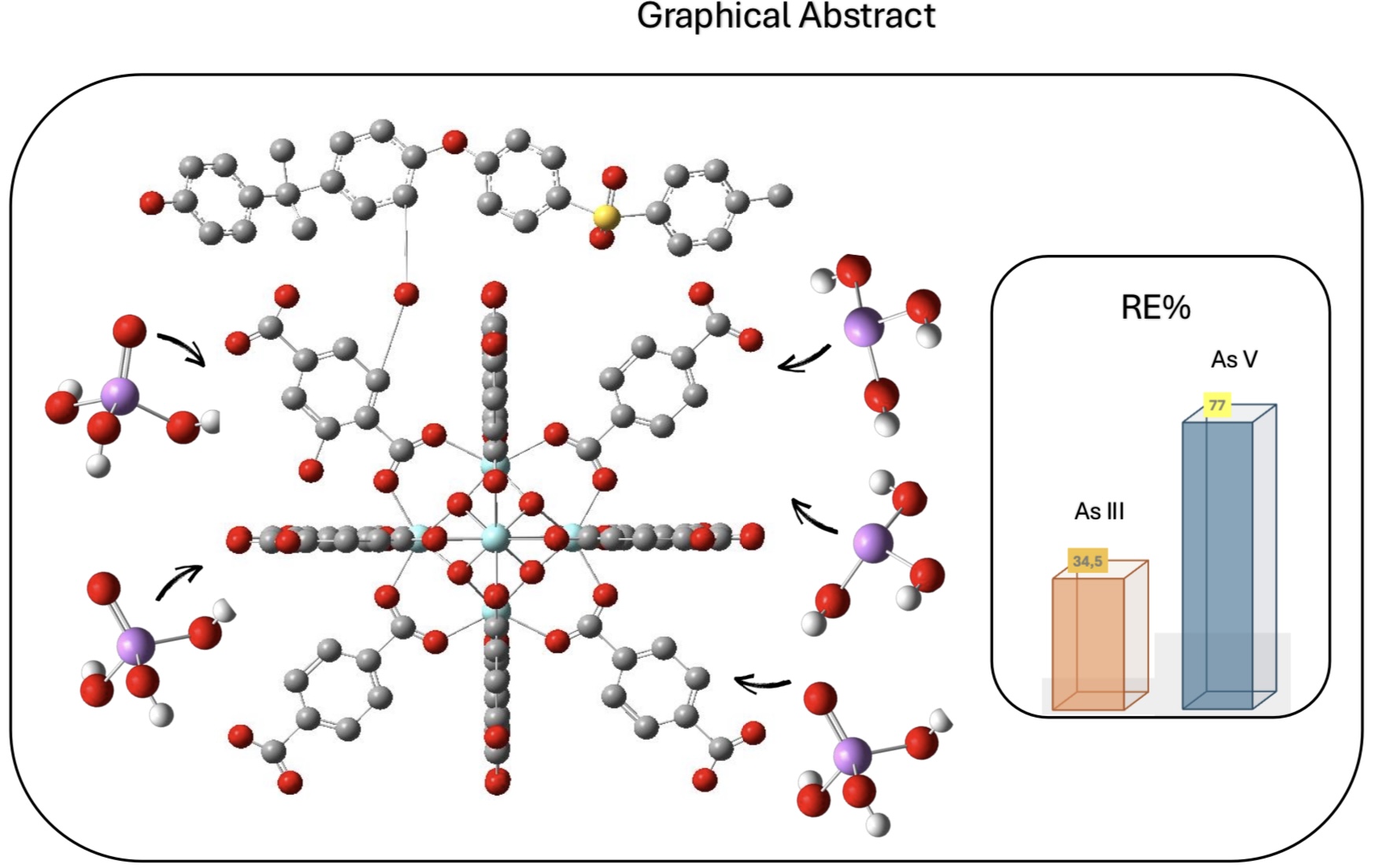

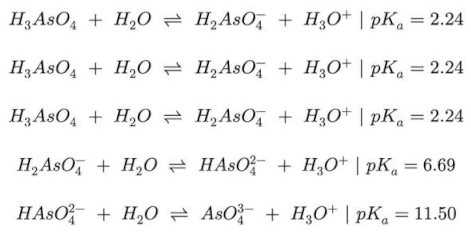

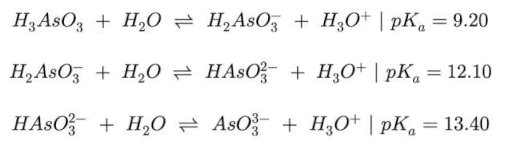

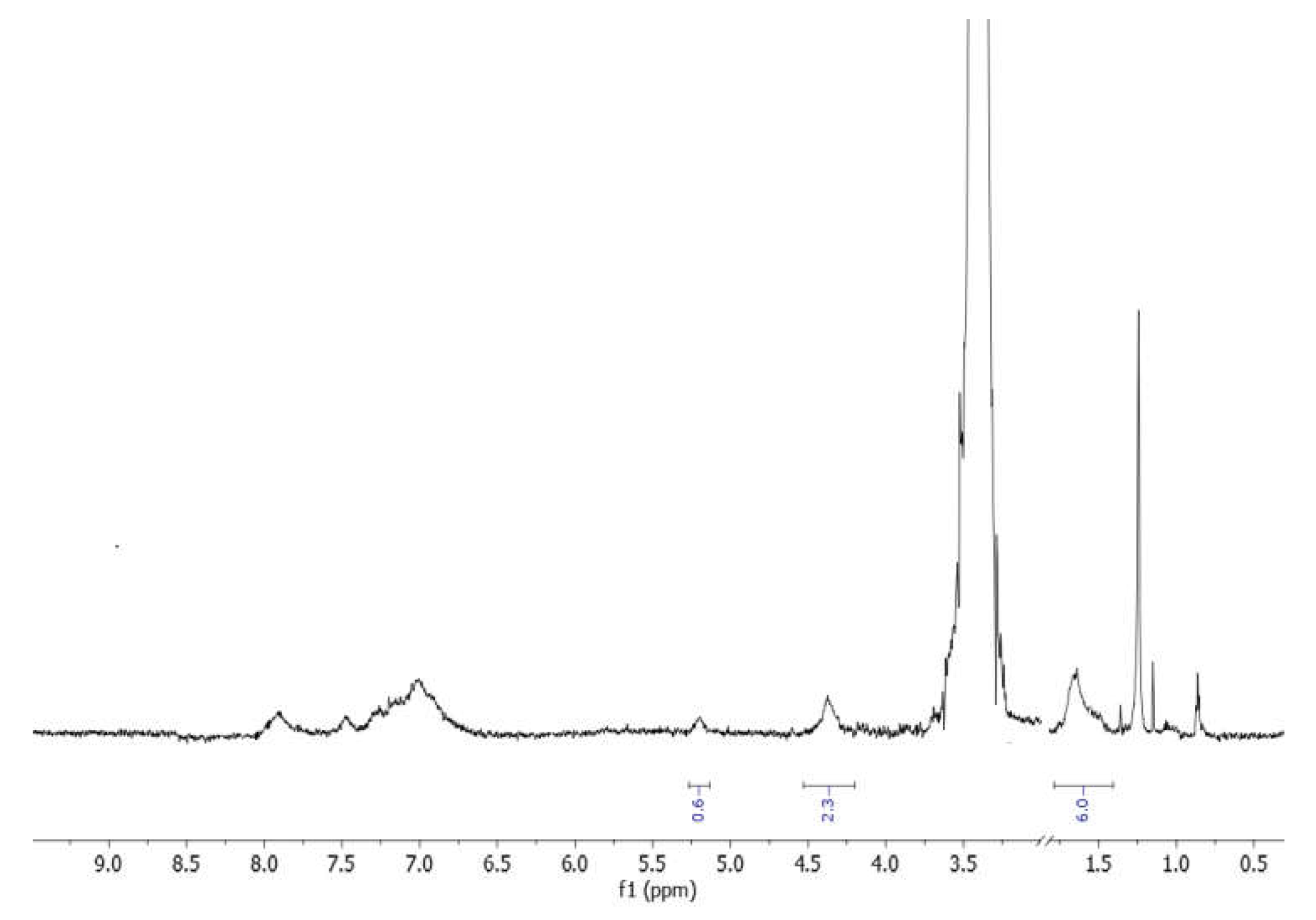

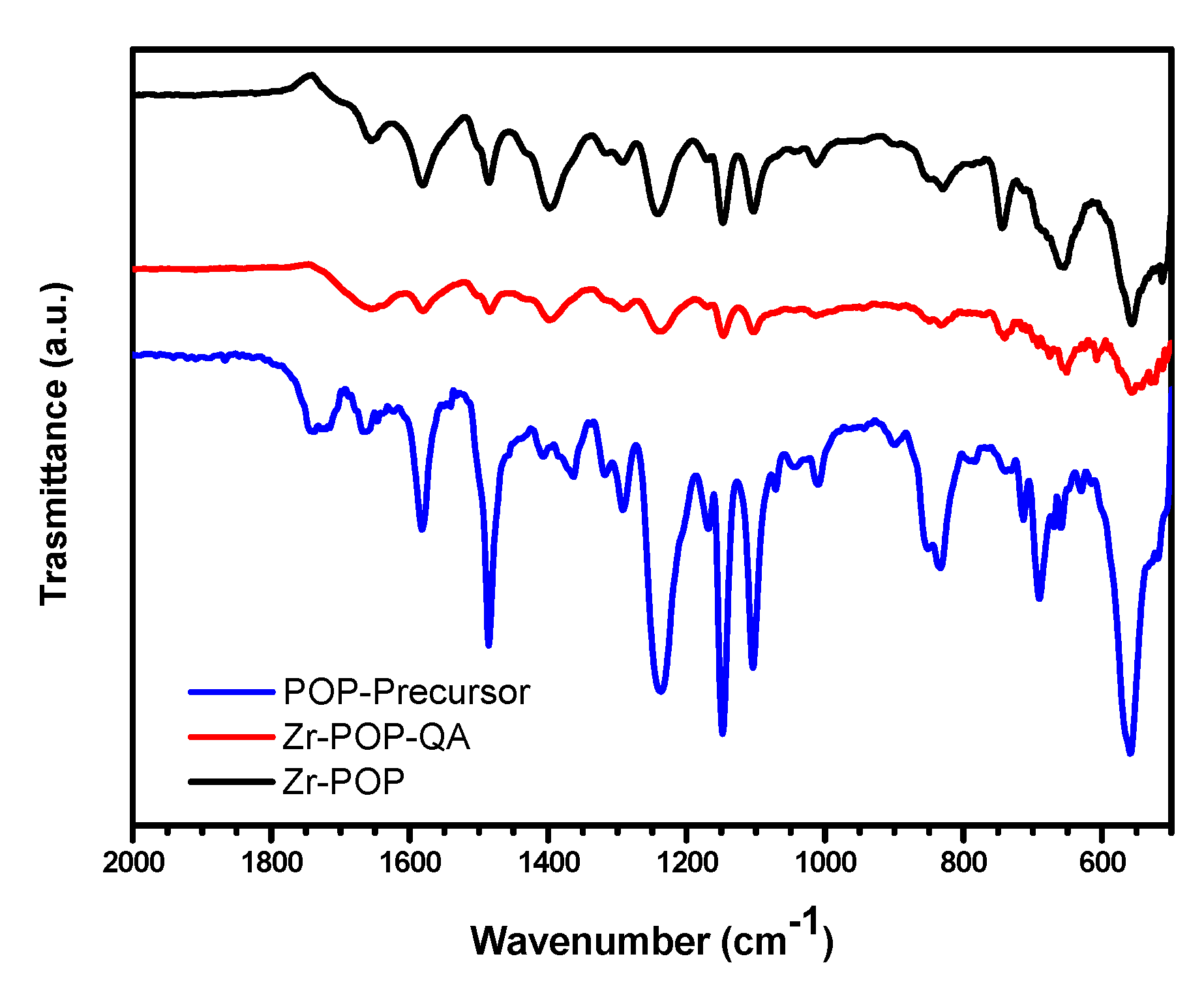

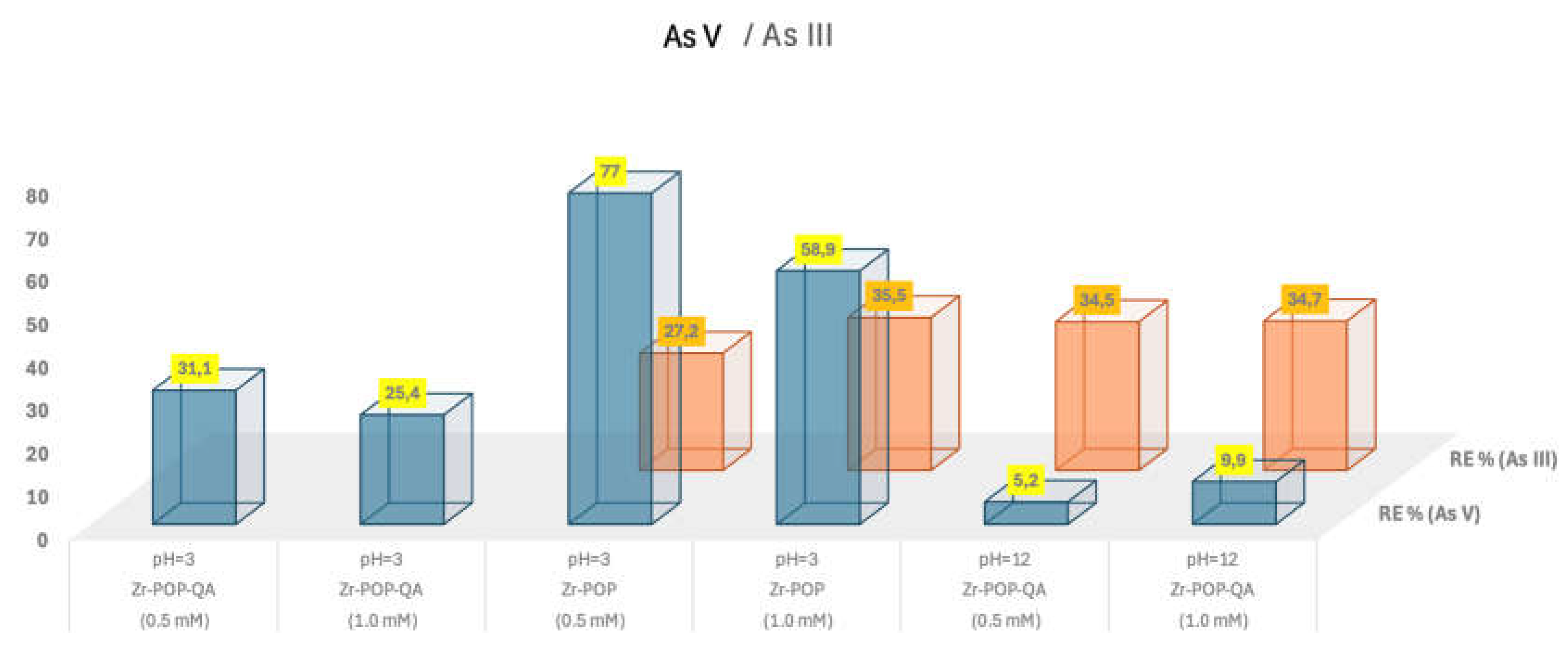

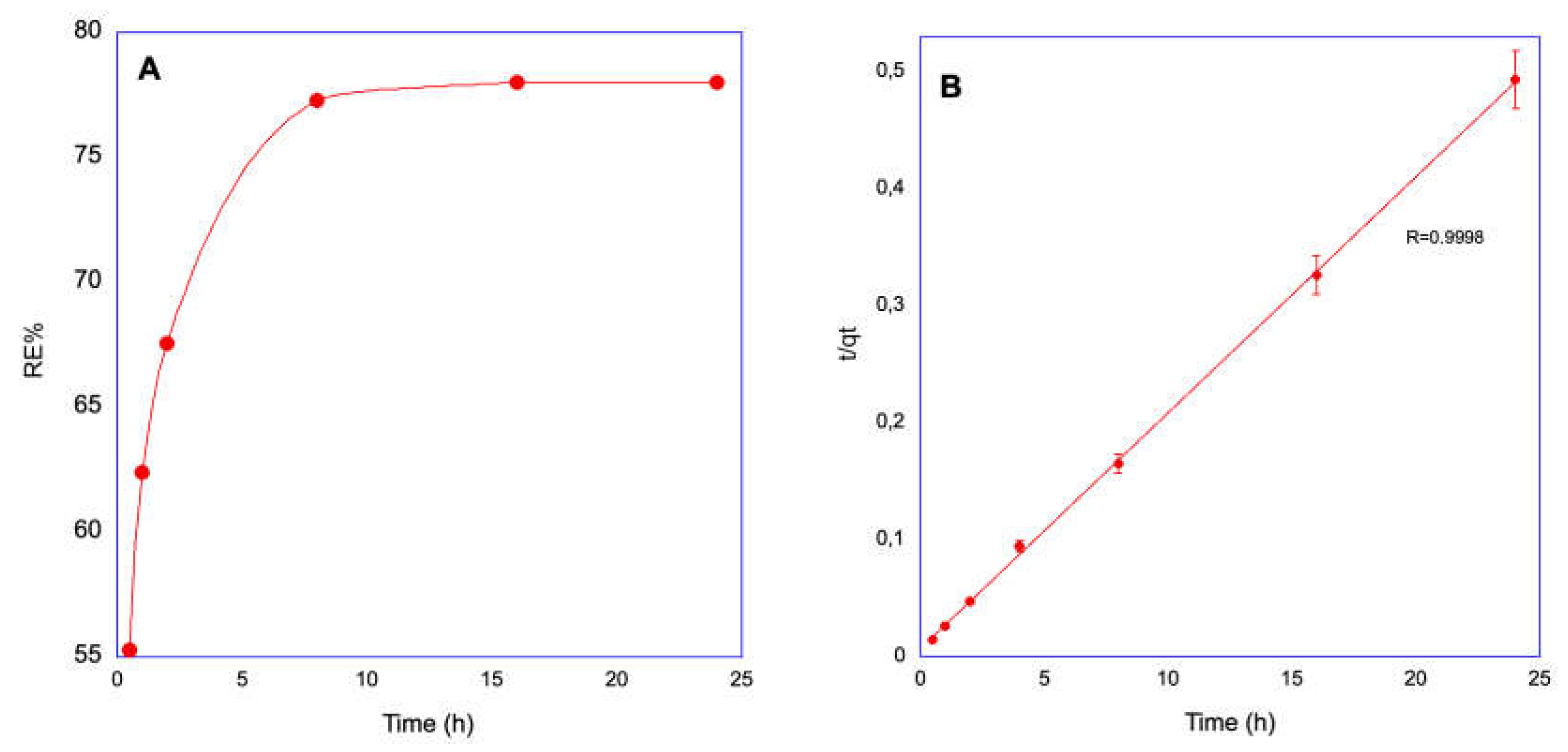

Porous organic polymers (POPs), based on polysulfone (PSU) and covalently linked zirconium-organic moieties have been applied for the first time to Arsenic removal in wastewater. The synthesis involved anchoring a synthon molecule onto PSU, followed by MOF assembly and subsequent quaternization (QA) with trimethylamine (TMA). Two samples Zr-POP and Zr-POP-QA are characterized by NMR, FTIR, and titration. The efficiency of As uptake is revealed by ICP. The study is carried out at different pH (3, 7, and 12) to vary the charge of Zr-organic moieties and the charge of arsenite and arsenate species. Two concentrations (0.5 and 1 mM) of As (III) and As (V) are used. The results show that Zr-POP at pH 3 has a removal efficiency (RE%) of 77% for As (V), in agreement with the positive charge present in the Zr-framework at this pH. At neutral pH the As (III) sorption is also relevant. Zr-POP-QA at pH 12 shows, thanks to the positive charge on the ammonium moieties, a RE% of As (III) equal to 35%. The kinetic of processes, performed on the most promising system, i.e. Zr-POP at pH 3 for As(V), shows a plateau already after 8 hours with a second-order law. The regeneration of the material is also evaluated. According to the results, these materials are serious candidates in the removal of heavy metals in wastewater.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis

2.2.1. POP-Precursor

2.2.2. Zr-POP

2.2.3. Zr-POP-QA

2.3. Batch Adsorption Studies

2.3.1. Kinetic measurements

2.3.2. Regeneration

2.4. Characterization Techniques

2.4.1. Ion Exchange Capacity

2.4.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

2.4.4. Inductively Coupled Plasma–Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES)

2.4.5. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) Aanalysis

3. Results and Discussion

| System | RE% | mg/g | Initial Concentration | As species | pH | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSU | 20% | - | - | As(V) | 2.6 | [46] |

| PPO/UiO-66 | 85% | 68.2 | - | As(V) | 7-10 | [47] |

| PAN/UiO-66 | 92% | - | - | As (III) As(V) |

4-9 | [48] |

| PMMA/UiO-66 | 89% | 110 | - | As(V) | 7-11 | [49] |

| Magnetite | - | 17.2 18.7 |

1.0 mM | As (V) As (III) |

5-9 | [50] |

| Organic Biochar | - | 16.2 | 50 ppm | As (V) | 2-19 | [51] |

| MIO-CNTs | - | 24.1 | - | As (V) | 2-10 | [52] |

| MIL-53(Fe) | - | 21.3 | - | As (V) | 5 | [53] |

| Fe3O4@UiO-66 | - | 73.2 | 150 ppm | As (V) | 7 | [54] |

| Fe–BTC | - | 12.3 | unknown | As (V) | 4 | [55] |

| Fe3O4@TA@UiO-66 | 80% | 97.8 | - | As (III) | 3-11 | [56] |

| Zr-POP | 77±5% | 50 | 60 ppm | As (V) | 3 | Our work |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bolan, N., et al., Remediation of heavy metal(loid)s contaminated soils – To mobilize or to immobilize? Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2014. 266: p. 141-166.

- Fu, F. and Q. Wang, Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 2011. 92(3): p. 407-418.

- Ibrahim, Y., et al., Numerical modeling of an integrated OMBR-NF hybrid system for simultaneous wastewater reclamation and brine management. Euro-Mediterranean Journal for Environmental Integration, 2019. 4(1): p. 23.

- Bastianini, M., et al., Composite membranes based on polyvinyl alcohol and lamellar solids for water decontamination. New Journal of Chemistry, 2024. 48(5): p. 2128-2139.

- Bastianini, M., et al., Polyvinyl Alcohol Coatings Containing Lamellar Solids with Antimicrobial Activity, in Preprints. 2024, Preprints.

- Maqbool, Z., et al., Perspectives of using fungi as bioresource for bioremediation of pesticides in the environment: a critical review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2016. 23(17): p. 16904-25.

- Pelati, M., Acqua all’arsenico in 51 comuni del viterbese: il caso in Parlamento, Corriere, Editor. 2021.

- Siddique, T.A., N.K. Dutta, and N. Roy Choudhury, Nanofiltration for Arsenic Removal: Challenges, Recent Developments, and Perspectives. Nanomaterials (Basel), 2020. 10(7).

- Wang, X., Y. Liu, and J. Zheng, Removal of As(III) and As(V) from water by chitosan and chitosan derivatives: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016. 23(14): p. 13789-13801.

- Yang, L., et al., A metal-organic framework as an electrocatalyst for ethanol oxidation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2010. 49(31): p. 5348-51.

- Song, G., et al., Preparation of MOF(Fe) and its catalytic activity for oxygen reduction reaction in an alkaline electrolyte. Chinese Journal of Catalysis, 2014. 35(2): p. 185-195.

- Mao, J., et al., Electrocatalytic four-electron reduction of oxygen with Copper (II)-based metal-organic frameworks. Electrochemistry Communications, 2012. 19: p. 29-31.

- Konnerth, H., et al., Metal-organic framework (MOF)-derived catalysts for fine chemical production. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2020. 416: p. 213319.

- Escorihuela, J., et al., Proton Conductivity of Composite Polyelectrolyte Membranes with Metal-Organic Frameworks for Fuel Cell Applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces, 2019. 6(2): p. 1801146.

- Kim, H.J., K. Talukdar, and S.-J. Choi, Tuning of Nafion® by HKUST-1 as coordination network to enhance proton conductivity for fuel cell applications. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, 2016. 18(2): p. 47.

- Patel, H.A., et al., Superacidity in Nafion/MOF Hybrid Membranes Retains Water at Low Humidity to Enhance Proton Conduction for Fuel Cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2016. 8(45): p. 30687-30691.

- Donnadio, A., et al., Mixed Membrane Matrices Based on Nafion/UiO-66/SO3H-UiO-66 Nano-MOFs: Revealing the Effect of Crystal Size, Sulfonation, and Filler Loading on the Mechanical and Conductivity Properties. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2017. 9(48): p. 42239-42246.

- Narducci, R., et al., Anion Exchange Membranes with 1D, 2D and 3D Fillers: A Review. polymers, 2021. 13(22): p. 3887.

- Kaur, H., et al., Metal–Organic Framework-Based Materials for Wastewater Treatment: Superior Adsorbent Materials for the Removal of Hazardous Pollutants. ACS Omega, 2023. 8(10): p. 9004-9030.

- Liu, X., et al., Application of metal organic framework in wastewater treatment. Green Energy & Environment, 2023. 8(3): p. 698-721.

- Feng, L., et al., Destruction of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Positive and Negative Aspects of Stability and Lability. Chemical Reviews, 2020. 120(23): p. 13087-13133.

- Lee, J., et al., Covalent connections between metal–organic frameworks and polymers including covalent organic frameworks. Chemical Society Reviews, 2023. 52(18): p. 6379-6416.

- Zhang, Z., et al., polyMOFs: A Class of Interconvertible Polymer-Metal-Organic-Framework Hybrid Materials. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2015. 54(21): p. 6152-7.

- Ayala, S., Z. Zhang, and S.M. Cohen, Hierarchical structure and porosity in UiO-66 polyMOFs. Chemical Communications, 2017. 53(21): p. 3058-3061.

- R. Narducci, et al., Ion-conducting porous organic polymers for single-component catalytic electrodes. 2024.

- Lin, R., et al., Mixed Matrix Membranes with Strengthened MOFs/Polymer Interfacial Interaction and Improved Membrane Performance. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2014. 6(8): p. 5609-5618.

- Tien-Binh, N., D. Rodrigue, and S. Kaliaguine, In-situ cross interface linking of PIM-1 polymer and UiO-66-NH2 for outstanding gas separation and physical aging control. Journal of Membrane Science, 2018. 548: p. 429-438.

- Xie, K., et al., Synthesis of well dispersed polymer grafted metal–organic framework nanoparticles. Chemical Communications, 2015. 51(85): p. 15566-15569.

- Zhou, W., et al., Construction of a Sandwiched MOF@COF Composite as a Size-Selective Catalyst. Cell Reports Physical Science, 2020. 1(12): p. 100272.

- Ahmad, K., et al., Engineering of Zirconium based metal-organic frameworks (Zr-MOFs) as efficient adsorbents. Materials Science and Engineering: B, 2020. 262: p. 114766.

- Li, Y.-H., et al., UiO-66(Zr)-based functional materials for water purification: An updated review. Environmental Functional Materials, 2023. 2(2): p. 93-132.

- Wang, C., et al., Superior removal of arsenic from water with zirconium metal-organic framework UiO-66. Scientific Reports, 2015. 5(1): p. 16613.

- Di Vona, M.L., et al., Anion-conducting ionomers: Study of type of functionalizing amine and macromolecular cross-linking. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2014. 39(26): p. 14039-14049.

- Di Vona, M.L., et al., Anionic conducting composite membranes based on aromatic polymer and layered double hydroxides. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2017. 42(5): p. 3197-3205.

- Smith, B.C., The Carbonyl Group, Part V: Carboxylates—Coming Clean. Spectroscopy, 2018. 33(5): p. 20–23.

- Pascual-Colino, J., et al., The Chemistry of Zirconium/Carboxylate Clustering Process: Acidic Conditions to Promote Carboxylate-Unsaturated Octahedral Hexamers and Pentanuclear Species. Inorganic Chemistry, 2022. 61(12): p. 4842-4851.

- Zhou, J., et al., Anionic polysulfone ionomers and membranes containing fluorenyl groups for anionic fuel cells. Journal of Power Sources, 2009. 190(2): p. 285-292.

- Yu, Y., et al., Yttrium-doped iron oxide magnetic adsorbent for enhancement in arsenic removal and ease in separation after applications. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2018. 521: p. 252-260.

- Pham, T.T., et al., Removal of As (V) from the aqueous solution by a modified granular ferric hydroxide adsorbent. Science of The Total Environment, 2020. 706: p. 135947.

- Chiban, M., et al. Application of low-cost adsorbents for arsenic removal: A review. 2012.

- Azhar, M.R., et al., Adsorptive removal of antibiotic sulfonamide by UiO-66 and ZIF-67 for wastewater treatment. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2017. 500: p. 88-95.

- Kebede Gurmessa, B., A.M. Taddesse, and E. Teju, UiO-66 (Zr-MOF): Synthesis, Characterization, and Application for the Removal of Malathion and 2, 4-D from Aqueous Solution. Environmental Pollutants and Bioavailability, 2023. 35(1): p. 2222910.

- Rodriguez-Narvaez, O.M., et al., Treatment technologies for emerging contaminants in water: A review. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2017. 323: p. 361-380.

- Zhang, X., et al., Water-stable metal–organic framework (UiO-66) supported on zirconia nanofibers membrane for the dynamic removal of tetracycline and arsenic from water. Applied Surface Science, 2022. 596: p. 153559.

- Samimi, M., et al., A Brief Review of Recent Results in Arsenic Adsorption Process from Aquatic Environments by Metal-Organic Frameworks: Classification Based on Kinetics, Isotherms and Thermodynamics Behaviors. Nanomaterials, 2023. 13(1): p. 60.

- Gupta, S., D. Bhatiya, and C.N. Murthy, Metal Removal Studies by Composite Membrane of Polysulfone and Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Separation Science and Technology, 2015. 50(3): p. 421-429.

- He, X., et al., Exceptional adsorption of arsenic by zirconium metal-organic frameworks: Engineering exploration and mechanism insight. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2019. 539: p. 223-234.

- Xie, Z., et al., Enhanced removal of As(iii) by manganese-doped defective UiO-66 coupled peroxymonosulfate: multiple reactive oxygen species and system stability. Environmental Science: Nano, 2024. 11(8): p. 3585-3598.

- Mahanta, N. and J.P. Chen, A novel route to the engineering of zirconium immobilized nano-scale carbon for arsenate removal from water. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2013. 1(30): p. 8636-8644.

- Liu, C.-H., et al., Mechanism of Arsenic Adsorption on Magnetite Nanoparticles from Water: Thermodynamic and Spectroscopic Studies. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015. 49(13): p. 7726-7734.

- . Zhu, N., et al., Adsorption of arsenic, phosphorus and chromium by bismuth impregnated biochar: Adsorption mechanism and depleted adsorbent utilization. Chemosphere, 2016. 164: p. 32-40.

- Chen, B., et al., One-pot, solid-phase synthesis of magnetic multiwalled carbon nanotube/iron oxide composites and their application in arsenic removal. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2014. 434: p. 9-17.

- Vu, T.A., et al., Arsenic removal from aqueous solutions by adsorption using novel MIL-53(Fe) as a highly efficient adsorbent. RSC Advances, 2015. 5(7): p. 5261-5268.

- Huo, J.-B., et al., Direct epitaxial synthesis of magnetic Fe3O4@UiO-66 composite for efficient removal of arsenate from water. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 2019. 276: p. 68-75.

- Zhu, B.-J., et al., Iron and 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic Metal–Organic Coordination Polymers Prepared by Solvothermal Method and Their Application in Efficient As(V) Removal from Aqueous Solutions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2012. 116(15): p. 8601-8607.

- Qi, P., et al., Development of a magnetic core-shell Fe3O4@TA@UiO-66 microsphere for removal of arsenic(III) and antimony(III) from aqueous solution. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2019. 378: p. 120721.

| System | Metal | Sample | pH/Initial concentrations As [mM] | RE % (±5%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | As V | Zr-POP-QA | pH=3/[0.5] | 31.1 |

| b | As V | Zr-POP-QA | pH=3/[1.0] | 25.4 |

| c | As V | Zr-POP | pH=3/[0.5] | 77.0 |

| d | As V | Zr-POP | pH=3/[1.0] | 58.9 |

| e | As V | Zr-POP-QA | pH=12/[0.5] | 5.2 |

| f | As V | Zr-POP-QA | pH=12/[1.0] | 9.9 |

| g | As III | Zr-POP | pH=7/[0.5] | 27.2 |

| h | As III | Zr-POP | pH=7/[1.0] | 35.5 |

| i | As III | Zr-POP-QA | pH=12/[0.5] | 34.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).