Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

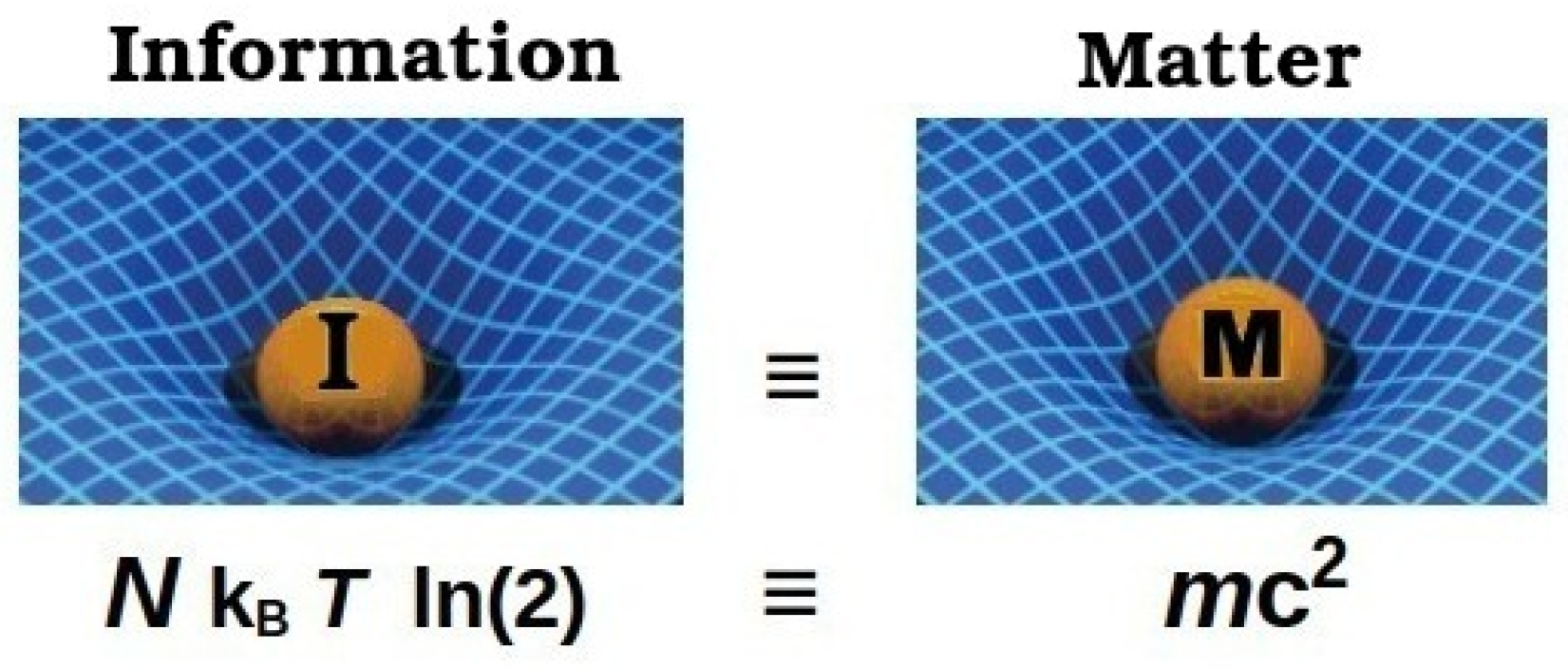

2. Information Dark Energy, IDE

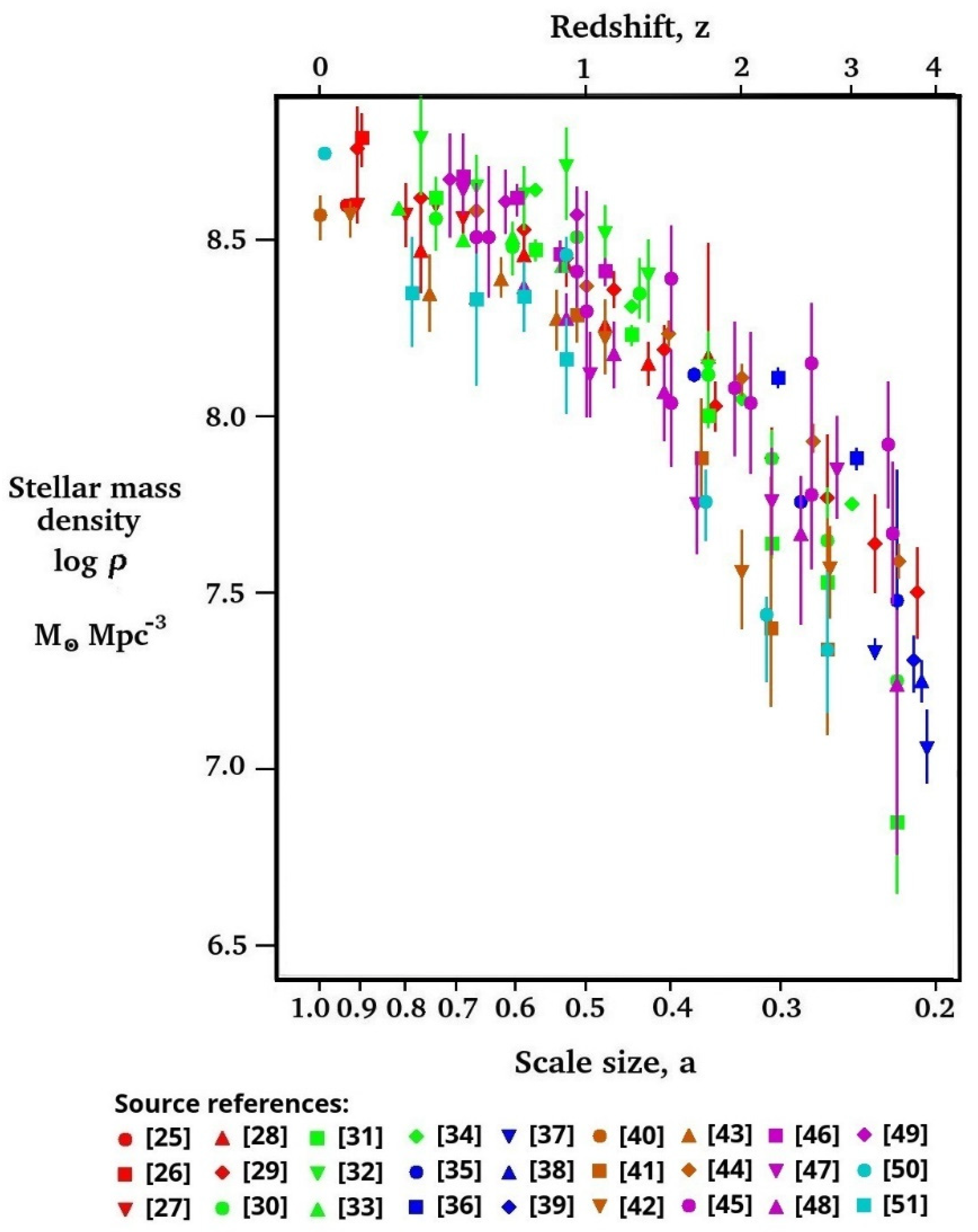

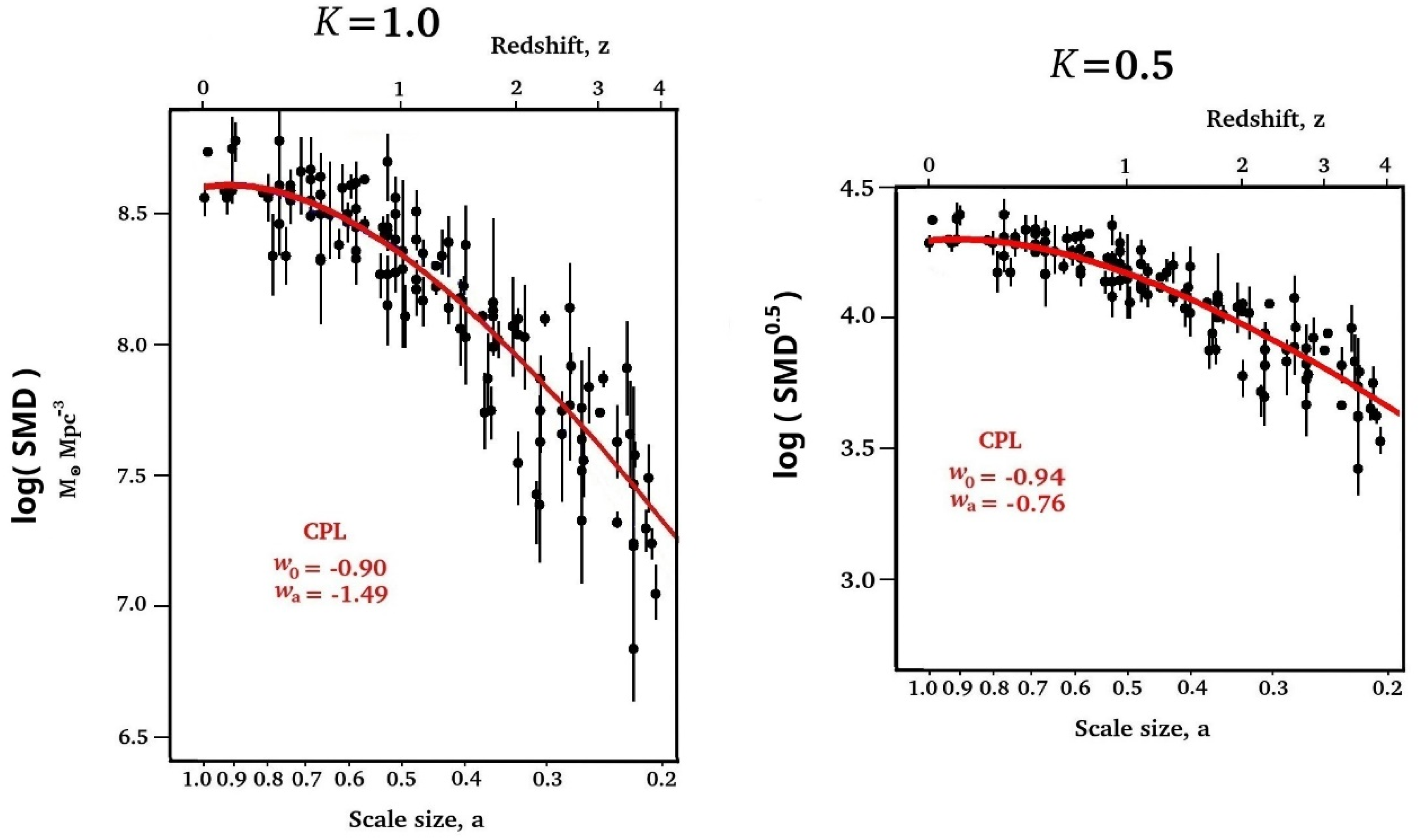

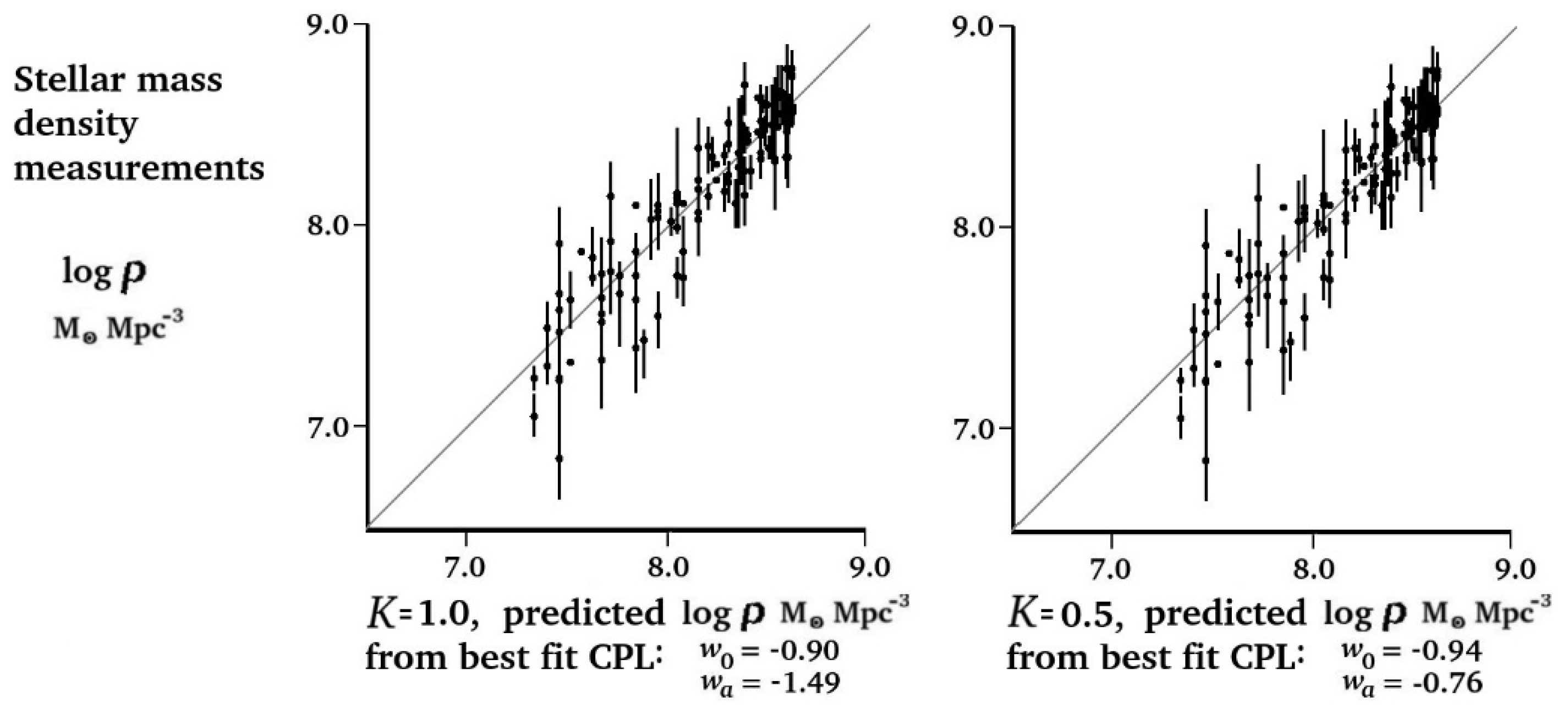

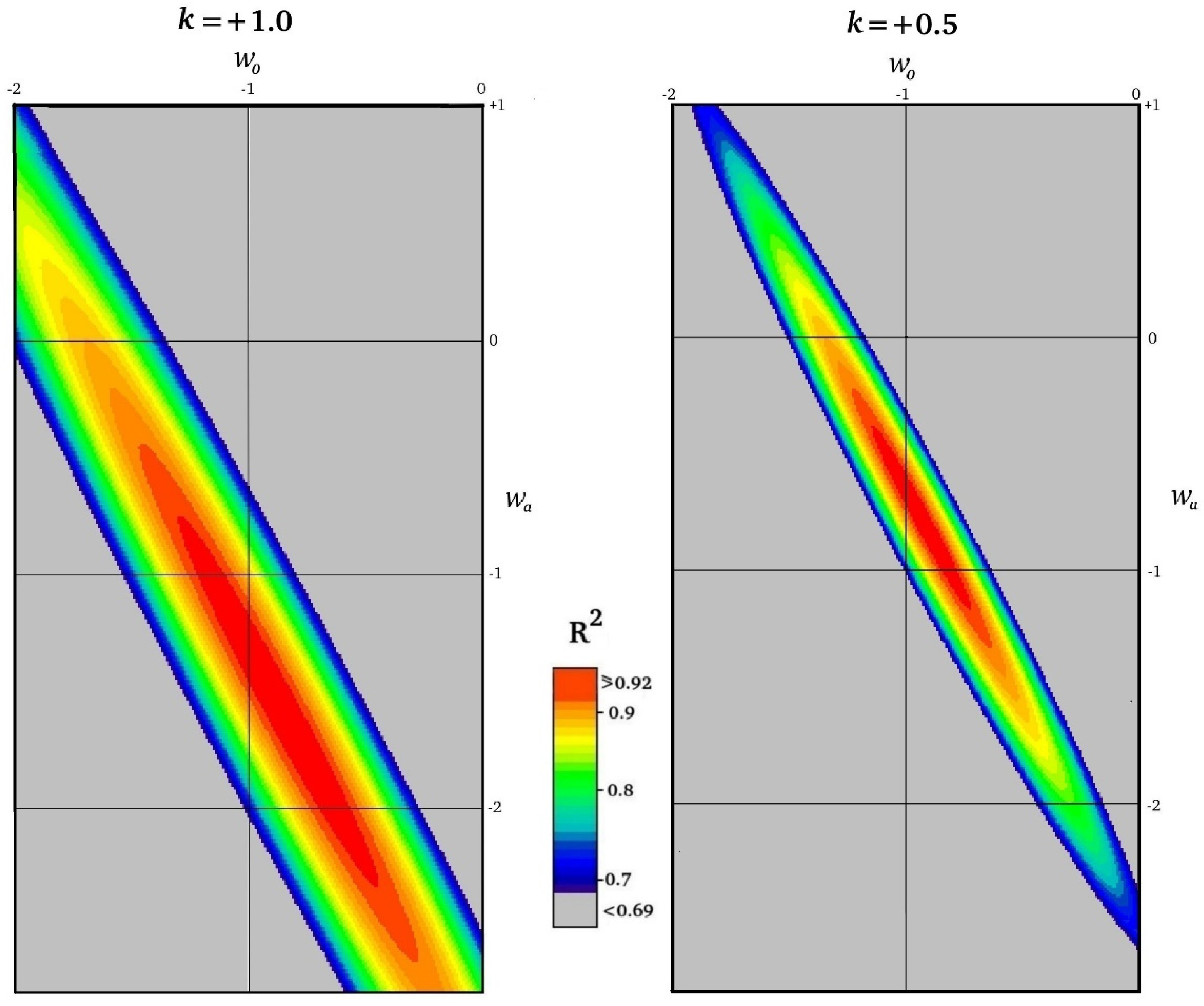

3. Comparison of IDE Prediction with Experimental Measurements

4. Discussion

4.1. IDE Can Account for the Observed Dark Energy

4.2. Cause and Effect

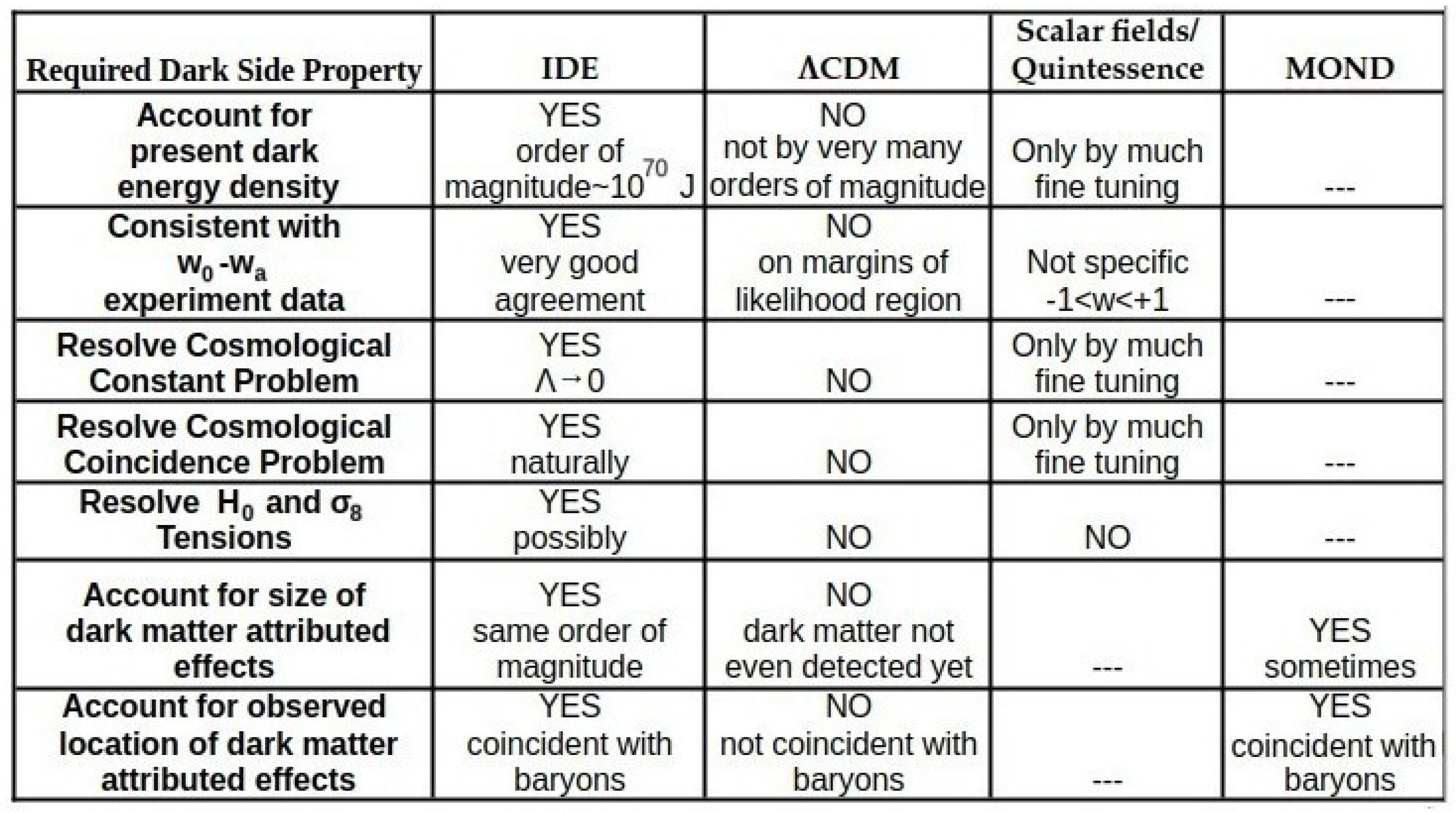

4.3. IDE Should Resolve Some Problems and Tensions of ɅCDM

4.4. IDE Can Also Account for Dark Matter Attributed Effects

5. Summary

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landauer,R., Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process, IBM J. Research and Development 1961, 3, 183-191. [CrossRef]

- Landauer, R., Information is physical, Physics Today, 1991, 44 , 23-29. [CrossRef]

- Toyabe, S., Sagawa, T., Ueda,M., Muneyuki,E., Sano,M., Experimental demonstration of information-to-energy conversion and validation of the generalized Jarzynski equality, Nature Physics, 2010, 6, 988-992. [CrossRef]

- Berut, A., Arakelyan,A., Petrosyan, A., Ciliberto,A., Dillenschneider, R., Lutz,E., Experimental verification of Landauer's principle linking information and thermodynamics, Nature , 2012, 483, 187-189. [CrossRef]

- Jun,Y., Gavrilov,M., Bechhoefer, J.,High-PrecisionTest of Landauer's Principle in a Feedback Trap, Phys.Rev. Let. 2014, 113, 190601-1 to -5. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.I.,et al., Single Atom Demonstration of the Quantum Landauer Principle, Phys.Rev. Let. 2018, 120, 210601. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A., Ford,K., It from bit in Geons, Black Holes and quantum foam: A life in Physics, New York, Norton. ISBN-13 : 978-0393046427.

- Zeilinger,A., A Foundational Principle of Quantum Mechanics, Foundations of Physics, 1999, 29, 631-643. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018820410908.

- Gough,M.P., Carozzi, T., Buckley,A.M., On the similarity of Information Energy to Dark Energy, Physics Essays, 2006, 19, 446-450. [CrossRef]

- Peebles,P.J.E., Principles of Physical Cosmology, 1993, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, USA. ISBN 978-0691209814.

- Gough,M.P., Information Equation of State, Entropy, 2008,10, 150-159. [CrossRef]

- Gough,M.P., Holographic Dark Information Energy, Entropy, 2011, 13 , 924-035. [CrossRef]

- Gough,M.P., Holographic Dark Information Energy: Predicted Dark Energy Measurement, Entropy, 2013, 15, 1133-1149. [CrossRef]

- Gough,M.P., A Dynamic Dark Information Energy Consistent with Planck Data, Entropy, 2014, 16, 1902-1916. [CrossRef]

- Gough,M.P., Information Dark Energy can Resolve the Hubble Tension and is Falsifiable by Experiment, Entropy, 2022, 24, 385-399. [CrossRef]

- Frampton, P.H., Hsu,S.D.H., Kephart, T.W., Reeb,D., What is the entropy of the universe? Classical Quantum Gravity, 2009, 26, 145005. 7pp. [CrossRef]

- Egan,C.A., Lineweaver, C.H., A larger estimate of the entropy of the universe, Astrophys. J., 2010, 710, 1825-1834. [CrossRef]

- T'Hooft, G., Obstacles on the way towards the quantization of space, time and matter- and possible solutions, Stud. Hist. Philosophy of Mod. Phys.,2001, 32, 157-180. [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L.,The world as a hologram, J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377-6396. [CrossRef]

- Buosso, R., The holographic principle, Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 825-874. [CrossRef]

- Chevallier,M., Polarski, D., Accelerating universes with scaling dark matter, Int. J. Mod. Phys. 2001, D. 10 , 213-224. [CrossRef]

- Brout,D., et al., The Pantheon+ Analysis: Cosmological Constraints, Astrophysical Journal, 2022, 938:110. [CrossRef]

- DES Collaboration, The Dark Energy Survey: Cosmology Results with ~1500 new High-redshift Type 1a Supernovae using the full 5-year Dataset, Astrophys.J. Lett, 2024, 973, L14. [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration, DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations, 2024, Arxiv 2404.03002, submitted to JCAP. [CrossRef]

- Li,C., White, S.D.M., The distribution of stellar mass in the low-redshift universe, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. , 2009, 398 , 2177-2187. [CrossRef]

- Gallazzi,A., Brinchmann, J., Charlot, S., White, S.D.M., A census of metals and baryons in stars in the local universe, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2008, 383, 1439-1458. [CrossRef]

- Moustakas,J., et al., PRIMUS: constraints on star formation quenching and Galaxy merging and the evolution of the stellar mass function from z=0-1, Astrophys. J. , 2013, 767, 50. 34pp. [CrossRef]

- Bielby,R., et al., The WIRCam Deep Survey. I. Counts, colours, and mass functions derived from near-infrared imaging in the CFHTLS deep fields, Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 545, A23. 20pp. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Gonzalez,P.G., et al., The stellar mass assembly of galaxies from z=0-4: analysis of a sample selected in the rest-frame near infrared with Spitzer, Astrophys. J.,2008, 675, 234-261. [CrossRef]

- Ilbert,O., et al., Mass assembly in quiescent and star-forming Galaxies since z >4 from UltraVISTA, Astron.Astrophys. 2013, 556, A55. 19pp. [CrossRef]

- Muzzin,A., et al., The evolution of the stellar mass functions of star-forming and quiescent galaxies to z=4 from the COSMOS/UltraVISTA survey, Astrophys. J. , 2013, 777 , 18. 30pp. [CrossRef]

- Arnouts,S., et al., The SWIRE-VVDS-CFHTLS surveys: Stellar Assembly over the last 10Gyr Astron.Astrophys. 2007, 476, 137-150. [CrossRef]

- Pozzetti,L., et al., zCOSMOS -10k bright spectroscopic sample. The bimodality in the galaxy stellar mass function, Astron. Astrophys. 2010, 523, A13. 23pp. [CrossRef]

- Kajisawa,M., et al., MOIRCS deep survey IV evolution of galaxy stellar mass function back to z 3, Astrophys. J. 2009, 702, 1393-1412. [CrossRef]

- Marchesini,D., van Dokkum, P.G., Forster Schreiber,N.M., Franx, M., Labbe, I., Wuyts, S., The evolution of the stellar mass function of galaxies from z=4 and the first comprehensive analysis of its uncertainties, Astrophys. J. 2009, 701, 1765-1769. [CrossRef]

- Reddy,N.A., et al., GOODS-HERSCHEL measurements of the dust attenuation of typical star forming galaxies at high redshift, Astrophys. J. 2012, 744 , 154. 17pp. [CrossRef]

- Caputi, K.J., Cirasuolo, M., Jdunlop,J.S., McLure, R.J., Farrah,D., Almaini, O.,The stellar mass function of the most massive Galaxies at 3<z<5 in the UKIDSS Ultra Deep Survey, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 413 , 162-176. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V., Labbe,I., Bouwens, R.J., Illingworth,G., Frank,M., Kriek M., Evolution of galaxy stellar mass functions, mass densities, and mass-to light ratios from z 7 to z 4, Astrophys. J. 2011, 735, L34. 6pp. [CrossRef]

- Lee ,K.S., et al., How do star-forming galaxies at z>3 assemble their masses?, Astrophys. J. 2012, 752, 66, 21pp. [CrossRef]

- Cole,S., al., The 2dF galaxy redshift survey, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2001, 326, 255-273. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson,M., Papovich,C., Ferguson, H.C., Budavari,T., The evolution of the global stellar mass density a 0 < z < 3, Astrophys. J. 2003, 587, 25-40. [CrossRef]

- Rudnick,G., et al., The rest-frame optical luminosity density, colour, and stellar mass density of the universe from z = 0 to z = 3., Astrophys. J. 2003, 599, 847-864. [CrossRef]

- Brinchmann,J., Ellis, R.S.,The ma.ss assembly and star formation characteristics of field galaxies of known morphology, Astrophys. J. 2000, 536 , L77-L80. [CrossRef]

- Elsner,F., Feulner,G., Hopp, U.,The impact of Spitzer infrared data on stellar mass estimates, Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 477, 503-512. [CrossRef]

- Drory,N., Salvato,M., Gabasch,A., Bender, R., Hopp, U., Feuler,G., Pannella, M.,The stellar mass function of galxies to z 5, Astrophys. J. 2005, 619, L131-L134. [CrossRef]

- Drory, N., Alvarez,M., The contribution of star formation and merging to stellar mass buildup in galaxies, Astrophys.J. 2008, 680, 41-53. [CrossRef]

- Fontana,A., et al., The assembly of massive galaxies from near Infrared observations of Hubble deep-field south, Astrophys. J. 2003, 594, L9-L12. [CrossRef]

- Fontana,A., et al., The galaxy mass function up to z=4 in the GOODS-MUSIC sample, Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 459, 745-757. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.G., CALTECH faint galaxy redshift survey, Astrophys. J. 2002, 567, 672-701. [CrossRef]

- Conselice, C.J., Blackburne,J.A., Papovich,C., The luminosity, stellar mass, and number density evolution of field galaxies, Astrophys. J. 2005, 620, 564-583. [CrossRef]

- Borch,A., et al., The stellar masses of 25000 galaxies at 0.2<z < 1.0 estimated by COMBO-17 survey, Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 453 , 869-881. [CrossRef]

- Madau, P., Dickinson, M., Cosmic Star Formation History, Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2014, 52, 415-486. [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, A. On the Curvature of Space, Gen. Relativ. Gravit ,1999, 31,1991.

- Ade P. et al., Plank Collaboration. Planck 2013 results. XVI. Cosmological parameters, Astron. Astrophys. 2014, 571, A16, 66pp. [CrossRef]

- Ade P. et al., Plank Collaboration. Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters, Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 594, A13, 63pp. [CrossRef]

- Plank Consortium, Aghanim.N. et al., Planck 2018 results. VI, Cosmological Parameters, Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6, 67pp. [CrossRef]

- Voit, G.M., Tracing cosmic evolution with clusters of galaxies, Reviews of Modern Physics, 2005, 77, 207-258. [CrossRef]

- Basu,B., and Lynden-Bell,D., A survey of entropy in the universe, Q. Jl., R. Astr. Soc., 1990, 31, 359-369. ISSN 0035-8738.

- Babyk,I.V., McNamara,B.R., The Halo Mass-Temperature Relation for Clusters, Groups, and Galaxies, Astrophysical Journal, 2023, 946, 54. [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, L.; Pierleoni, M.; Meneux, B.; Branchini, E.; LeFevre, O.; Marinoni, C.; Garilli, B.; Blaizot, J.; DeLucia, G.; Pollo, A.; et al. A test of the nature of cosmic acceleration using galaxy redshift distortions. Nature 2008, 451, 541. [CrossRef]

- Frieman,J.A.,Turner, M.S., Huterer,D., Dark energy and the accelerating universe. Ann.Rev.Astron.Astrophys. 2008,46,385. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S.,The cosmological constant problem, Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Benevento,G., Hu,W., Raven,M., Can late dark energy raise the Hubble constant?, Phys. Rev. D, 2020, 101, 103517-1-7. [CrossRef]

- Keeley,R., Joudaki,S., Kaplinghat, M., Kirkby,D., Implications of a transition in the dark energy equation of state for the H0 and σ8 tensions, J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2019, 12, 035. [CrossRef]

- Peracaula,J.S., Gomez-Valent,A., De Cruz Perez,J., Moreno-Pulido,C., Running vacuum against the H0 and σ8 tensions, Exploring the Frontiers of Physics, 2021, 134, 19001. p1-p7. [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, J., et al, First constraints on WIMP-nucleon effective field theory couplings in an extended energy region from LUX-ZEPLIN, Phys. Rev. D, 2024, 109, 092003-1 to -17. [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, S.S., Lelli,F., Schombert, J.M.,The Radial Acceleration Relation in Rotationally Supported Galaxies, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 201101-1 to -6. [CrossRef]

- Lelli,F., McGaugh,S.S., Schombert, J.M., Pawlowski, M.S.,One Law to Rule them all: the Radial Acceleration relation of Galaxies, Astrophys. J. 2017, 836, 152. 23pp. [CrossRef]

- Viola,M., et al.,Dark matter halo properties of GAMA galaxy groups from 100 square degrees of KiDS weak lensing data, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 452, 3529-3550. [CrossRef]

- Markevich,M., Gonzalez,A.H., Clowe,D., Vikhlinin,A., Forman, W., Jones, C., Murray, S., Tucker,W., Direct constraints on the dark matter self-interaction cross-section from the merging galaxy cluster, Astrophys. J. 2004, 606, 819-824. [CrossRef]

- Harvey,D., Massey,R., Kitching, T., Taylor, A., Tittley,E., The non gravitational interactions of dark matter in colliding galaxy clusters, Science 2015, 347, 1462-1465. [CrossRef]

- Massey,R., et al. The behaviour of dark matter associated with four bright Cluster galaxies in the 10kpc core of Abell 3827, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 449, 3393-3406. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).