1. Introduction

A stable energy future is the main goal of the research that is being carried out in the field of energy conversion. Decarbonization of power systems is becoming a global effort that requires large-scale implementation of zero-carbon technologies [

1], particularly for the generation of renewable energy. Photovoltaic (PV) and wind power plants are now cost competitive with power generation from fossil fuel sources. Interest in low-carbon technologies is gaining momentum and is expanding into larger and larger operating areas. One such area is facilities with autonomous power grids, designed and customized to meet specific energy requirements. Examples include space vehicles or shipboard systems.

In the case of facilities containing autonomous power supply systems, an essential component of power generation is a system of generators, often powered by engines fueled by fossil fuels. Synchronized generator operation is the basis for the stability of the internal grid and the key to preventing unwanted power outages. In the situation of using renewable energy sources, the problem is complicated by the voltage inverters connected to the on-board grid, which are an essential element to integrate it with renewable energy resources. The complication arises from the need for perfect synchronization of power control algorithms with the voltages in the grid, without which maintaining acceptable reliability and efficiency of on-board power systems becomes a difficult, and in some situations impossible, task [

2].

The use of power electronic systems, especially grid-connected converters, requires proper synchronization with the frequency and phase of the grid voltage. This is a critical task for the correct operation of synchronous-based controllers, due to their dependence on the accuracy of variable transformation procedures. [

3,

4,

5]. Extensive research into methods of synchronizing grid converters reduces to procedures for minimizing deviations in voltage, phase angle, and frequency between the output of a renewable energy source generator and the grid. [

6].

The most popular synchronization schemes for grid-connected inverters are based on phase locked loop (PLL) and extended PLL (EPLL) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Among the techniques described in the literature, solutions based on Kalman filtering [

13,

14,

15,

16] and discrete or recursive Fourier transforms can be found [

17,

18,

19]. These methods are able to provide control algorithms not only with the information necessary for synchronization but also with information regarding harmonics. Thanks to them, it is possible to activate procedures to improve the quality of electricity in the power system. One of the more commonly used methods of synchronization in single-phase systems is also a method based on the use of a generalized second-order integrator (SOGI), which performs harmonic detection and generates the necessary synchronization signals [

20,

21,

22]. With SOGI, synchronization systems characterized by low complexity in relation to methods using Fourier transform or Kalman filters are obtained.

The synchronization methods described in the literature refer to power grids with a fixed voltage frequency. In the case of autonomous on-board grids, the voltages have a wide frequency range reaching up to 800 Hz. In such a situation, the estimation of synchronization signals is a more difficult problem [

23] than in the case of typical power grids. This is caused by problems in the accuracy of the calculations that cause a reduction in the dynamic response of the synchronization system in the estimation of voltage parameters. All described synchronization methods are characterized by good performance in estimating voltage parameters only around the equilibrium point [

24]. The work [

18,

25] attempted to estimate the change frequency in a system designed for aircraft, but its main weakness is the high computational load.

Many on-board grids are characterized by the presence of power buses with different voltage parameters. Typical AC subgrids are characterized by different voltage parameters, in particular different voltage frequencies in relation to the objects fed from it. In most cases, the voltage parameters of these buses are fixed and the connection of grid converters that integrate them with renewable energy sources requires the use of known synchronization methods, effectively estimating the voltage parameters around static equilibrium points. A special group is represented by power buses, to which are connected devices that require dynamic changes in the value of voltage amplitude or frequency. An example of such a device can be an ozone generator, which is necessary in water treatment processes. In such a situation, the use of classical synchronizers becomes impossible, because of the wide divergence of the device's operating frequency from the synchronizer's equilibrium point. The main challenge of the work was to develop a new synchronization system which, by modifying to an adaptive form of a generalized second-order integrator, allows efficient synchronization of a grid converter with a widely varying grid frequency. Consequently, this allows precise control of the active and reactive components of the current of the grid without causing emergency shutdowns of the device.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the synchronization problem resulting from linear changes in the frequency and amplitude of the supply voltage. The problem resulting from a voltage having the shape of a chirped signal is analytically demonstrated, and the numerically determined error causing disturbance of the control system's reference signals is presented. A new algorithm for adaptive synchronization and a proportional-resonant control system is described.

Section 3 presents test results that confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Section 4 concludes the paper by formulating the final conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

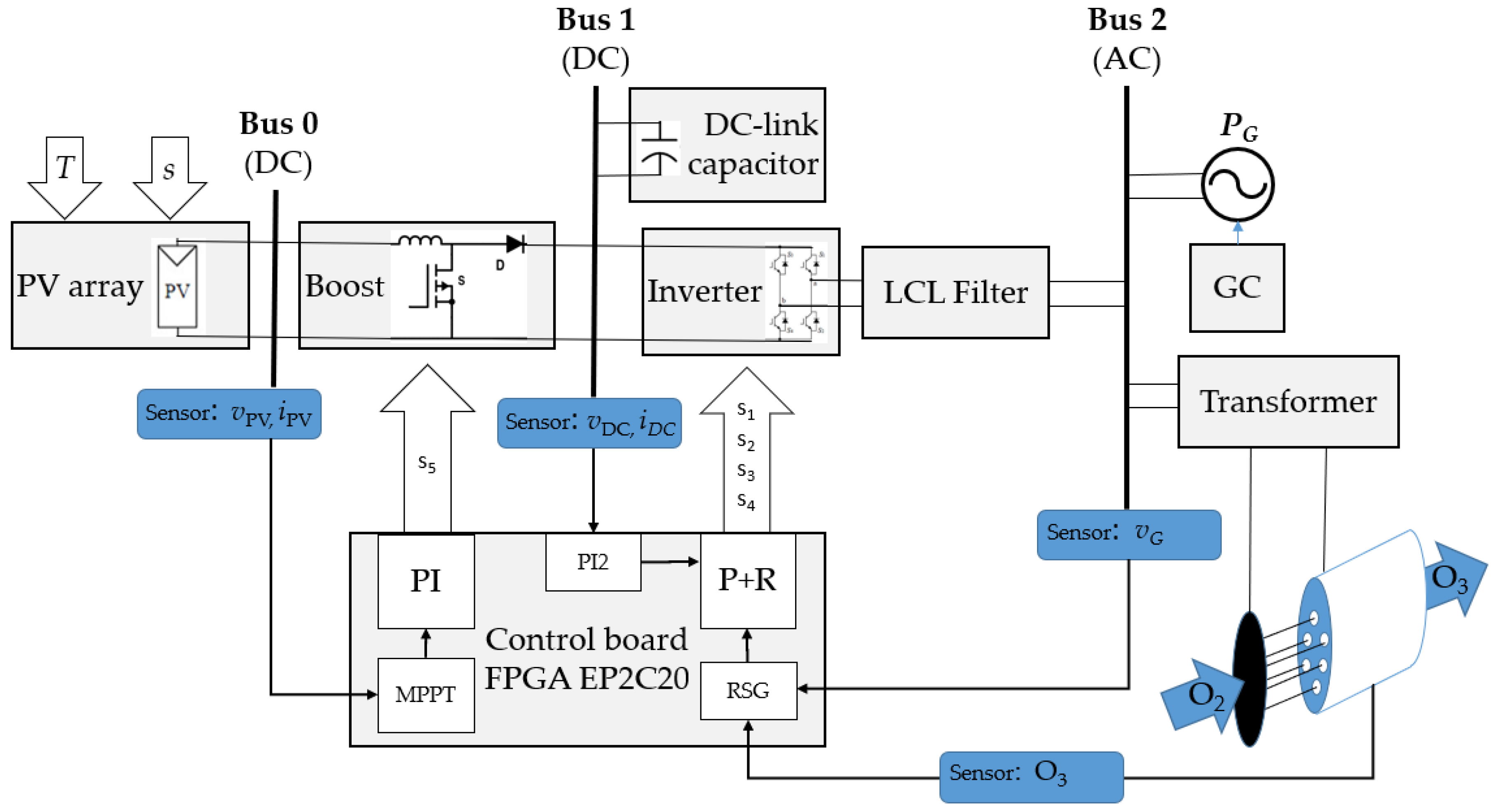

The vast majority of systems in which energy is converted operate at constant operating parameters. If these parameters change over time, these changes usually have time constants that are many times larger than the characteristic time constants of the converter devices. However, there are situations in which the given trajectories of changes in operating parameters are characterized by high dynamics, which cause disturbances in the operation of the converter. One of such devices is an ozone generator, used in the water treatment process. The processes of optimizing energy distribution and consumption on flying platforms, ships, and space vehicles additionally require the use of renewable energy. The study refers to the analysis of the use of solar energy in the ozone production process in the context of the changes in the high dynamics of voltage frequency forcing internal electrical discharges. The system which block diagram is shown in

Figure 1 was tested.

The tested system is part of an on-board system developed and reported in publications [

26], in which the solar energy conversion subsystem is connected to Bus 2. Bus 2 supplies power to a facility characterized by a high-steep voltage frequency trajectory during the start-up phase. It was assumed that the trajectory of changes in the voltage generator's operating parameters is made independently through the system (GC) controlling the operation of the power generator (PG). In the research conducted, the device start process was assumed by implementing a reference voltage trajectory according to the curves shown in

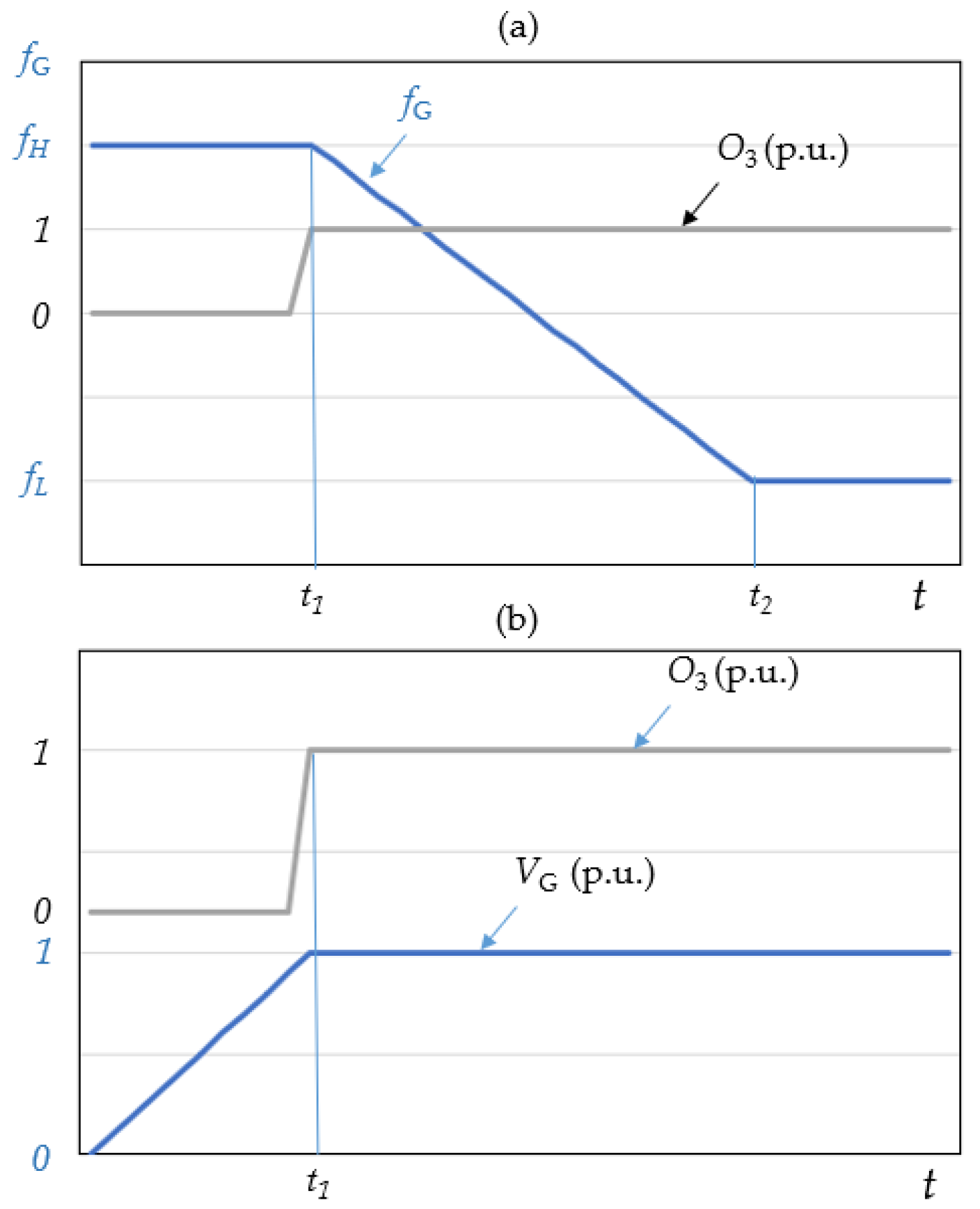

Figure 2.

At the time of starting the device, the generator begins operating with voltage at the maximum frequency

fH and amplitude close to zero. By linearly increasing the voltage at a constant frequency, the start-up control process waits for the signal of the beginning of electrical discharges in the device and the production of ozone. When the initiated ozone producing process is detected (

t1), the generator starts to reduce the voltage frequency from

fH to

fL. This reduction occurs linearly and lasts until the moment (

t2), defined in the technological process as the stable phase. An example of the Bus 2 voltage waveform of a generator implementing the assumed trajectory of amplitude and frequency changes is shown in

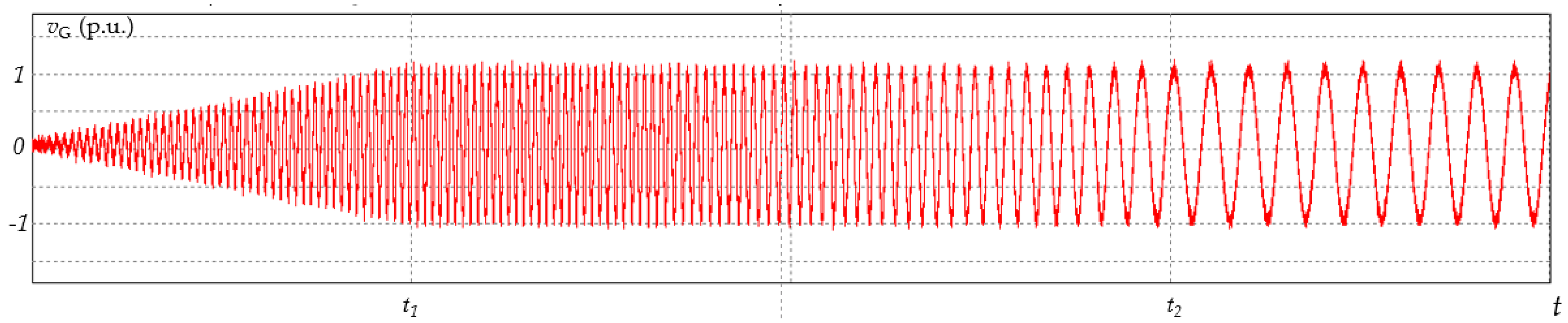

Figure 3.

Taking into account the voltage frequency trajectory from

Figure 2 (a) and the voltage amplitude trajectory from

Figure 2b, the voltage waveform

vG on Bus 2 can be described as follows:

where

V is the amplitude of the voltage at which sliding discharges take place.

Assuming that the energy needed to generate ozone comes not only from the generator (PG) but also from the photovoltaic panels, a photovoltaic converter is connected to Bus 2 to transmit the converted solar energy. The amount of energy available depends on environmental parameters such as the outdoor temperature

T and solar irradiance

s, and is a function of the installed power of the PV array. The operating point of photovoltaic panels is determined by the Maximum Power Point Tracker (MPPT) implementing the incremental conductance algorithm [

27] based on the current values of the photovoltaic voltage

vPV and photovoltaic current

iPV. In the proportional integral control algorithm (PI), the fill factor for the switch s in the boost converter is determined. This converter controls the capacitor charge current in the DC link in a way that allows the maximum power point of the PV to be obtained. Increasing or decreasing the current feed into the DC link causes the voltage across Bus 1 to rise or fall, respectively. To counteract this, based on the measured voltage value in Bus 1, another proportional integral regulator (PI2) controls the reference current of the grid converter (Inverter), leading to voltage stabilization in Bus 1.

The value of the current fed by the grid converter into Bus 2 depends on the current energy production of the PV array. Most of the time, the grid inverter is not loaded with nominal power, so it was used to compensate for reactive power in Bus 2. The parameters of the current fed into Bus 2 are determined by the proportional-resonant regulator (P+R), which controls the active and reactive components of the current. This is possible only if the current control algorithm has current information on the orthogonal components of the voltage vG occurring on Bus 2. The function of the orthogonal signal generator is performed by the reference shape signal generator (RSG).

The proportional-resonant control system that controls the current fed Bus 2 is designed to directly control the active and reactive components. The reference value of the active component

iar is set to obtain a stable voltage on Bus1 according to formula (2).

where Δ

vDC is the voltage deviation on Bus 1,

kP is the gain and

TC is the integration constant. The reference value of the reactive component

irr is arbitrarily determined based on the given level of reactive power compensation on Bus 2. The calculated active and reactive components of the current are used to define the reference waveform for the proportional-resonant algorithm according to formula (3).

where

and

estimate the cosine and sine components of the voltage on Bus 2, respectively. In the case of ac systems characterized by a constant voltage frequency, the waveforms of the sinusoidal and cosine components of the voltage can be easily calculated using the known structures of quadrature generators based on the integration of the fundamental component obtained from the phase lock loop (PLL) system. In the case of the voltages described by Equation 1, there is a problem related to the calculation of the combination of the trigonometric function and the linear function.

Assuming that in the linear stage of the voltage frequency change, the fundamental component estimation algorithm (implemented in RSG) reconstructs it by directly implementing the trajectory in the form of Equation (4):

where

af is the is a directional coefficient that determines the dynamics of frequency changes, the reference signal curve can be written in the form (5):

Formula (5) describes a typical chirp signal in which the frequency increases (for

af > 0) or decreases (for

af < 0) over time. It is commonly used in spread spectrum systems. In order to analyze the influence of the voltage estimation given by Equation (5) on the control process, its transform should be analyzed. The Fourier transform of the function (5) has the form:

The function (5) can be written as:

then

Due to the fact that the exponents in equation (8) are quadratic functions, the resulting oscillating integrals can be simplified by substituting:

Assuming a stationary point where the phase differential takes a value of zero, the results are obtained:

and

The Fourier transform of a quadratic phase function leads to a result proportional to the Gaussian function in the frequency domain. Based on the symbolic calculations performed in Maple, approximate results were obtained:

and

By substituting (13) and (14) into (8), it can be written:

Assuming a constant value for the steepness of the frequency ramp

af, Fourier transform (15) can be simplified to the form:

Formula (16) is in the form of a Gaussian function with a distribution that depends on the rate of change of frequency. Therefore, it can be concluded that a function of the steepness of frequency changes in the interval from t1 to t2, the amplitude of the signal estimate described by equation (5) will change. In this case, the use of a standard PLL will cause the reference waveforms obtained in it to be no longer unit waveforms.

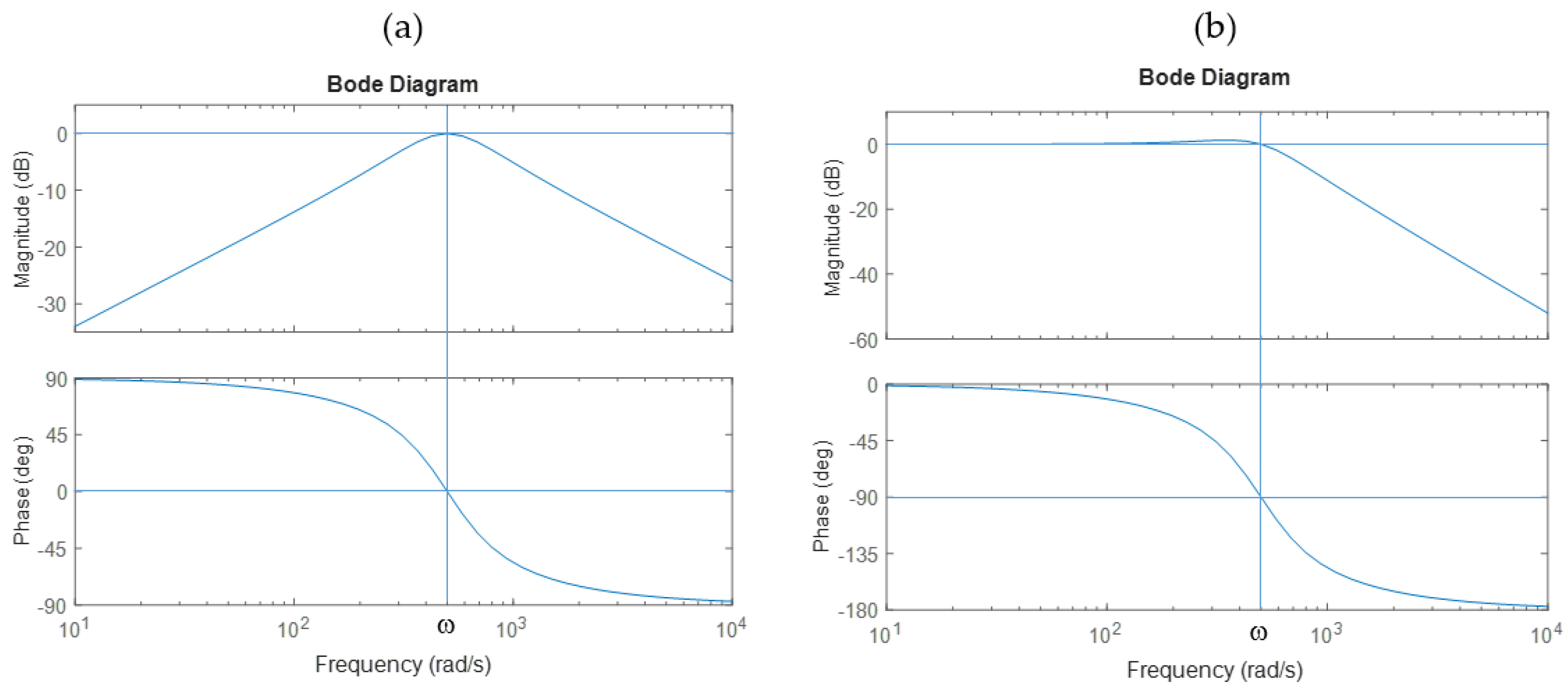

In a further stage of research, the problem arising from equation (16) was analysed in the structure of a generalized second-order integrator, which acts as a quadrature generator for phase synchronization. The equations of the quadrature generator are described by the following equations:

where

and

are orthogonal signals,

v is the input signal and ω=2π

f. The Bode plots corresponding to equations (17) and (18) are shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4a shows the Bode plot of the sine function, and

Figure 4b the cosine function determined for a fixed frequency ω = 500 Hz. Analyzing the plots, it can be concluded that for a variable frequency, the sinusoidal signal should be disturbed to a small degree relative to the cosine signal. In the case of the chirp signal, occurring in the interval from

t1 to

t2 of the signal presented in

Figure 3, equations (17) and (18) can be written in the form:

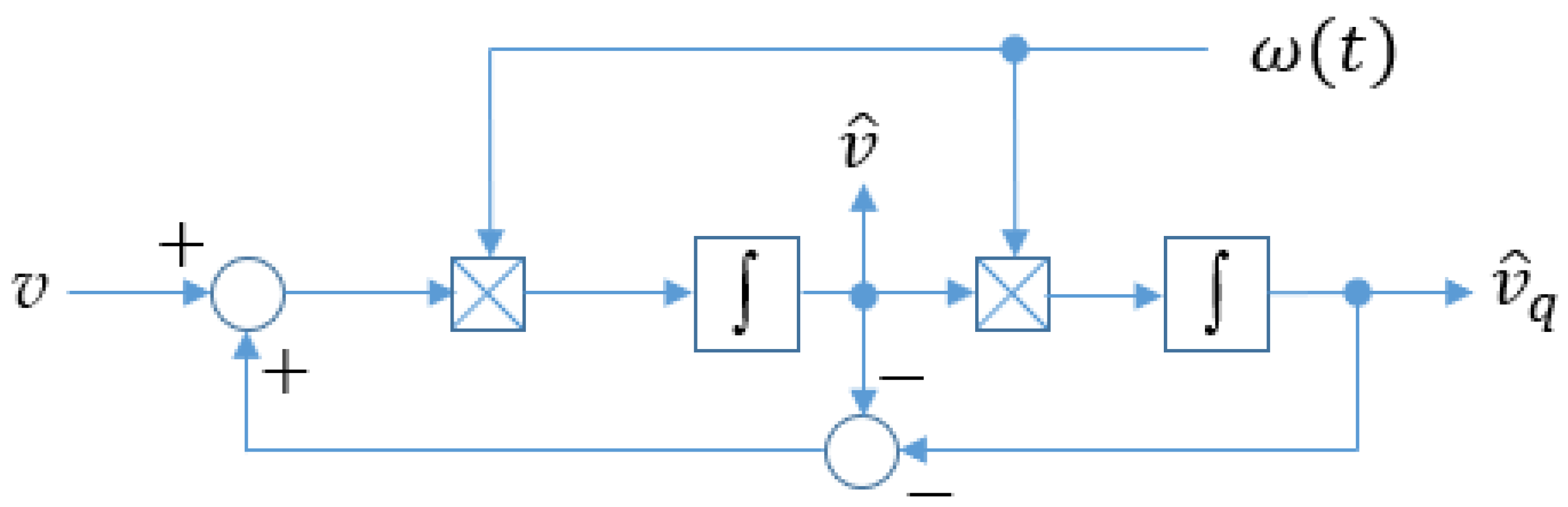

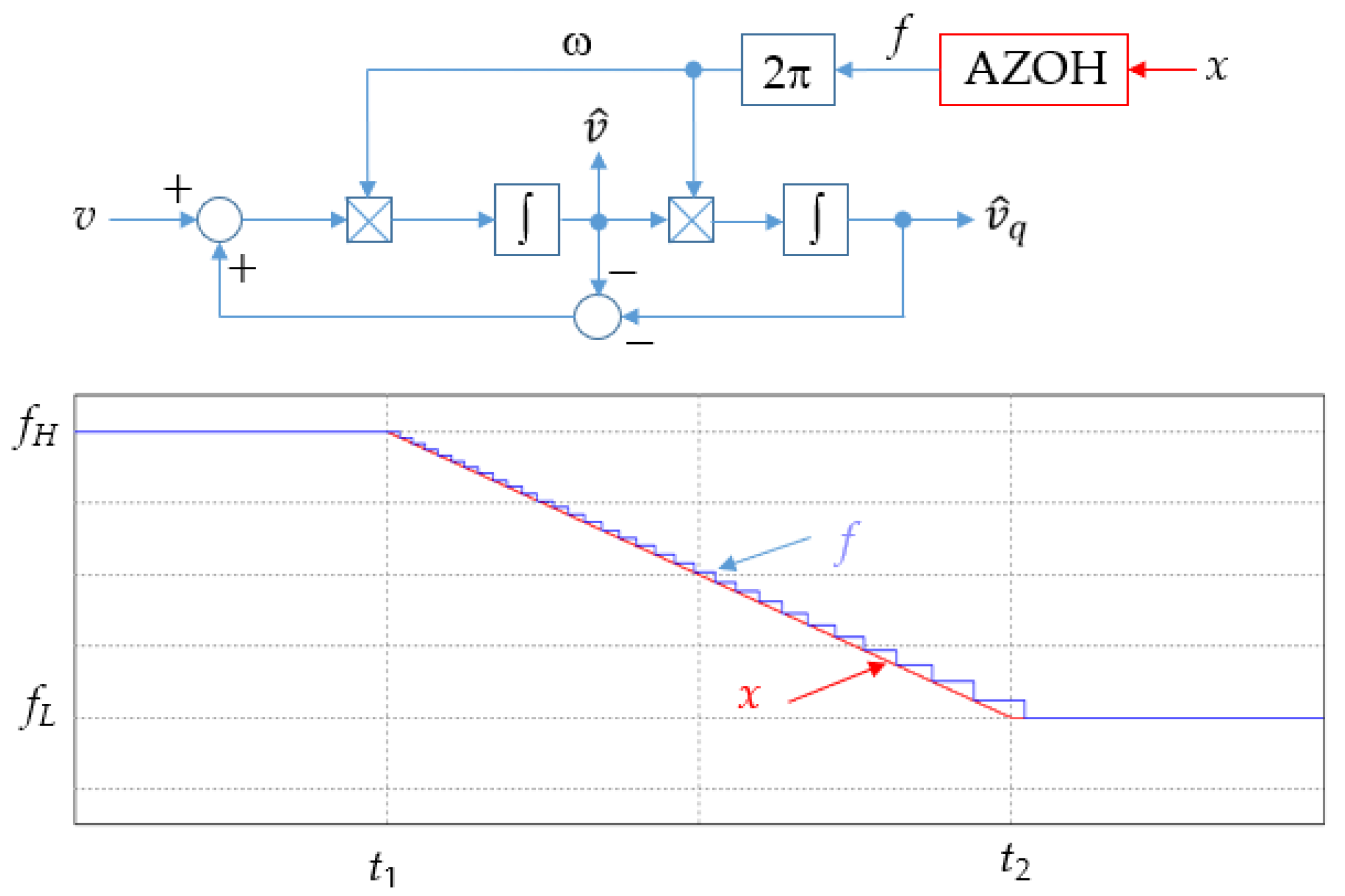

The analytical solution of differential equations (19) and (20) is a complex problem, so their numerical simulation was performed. The block structure of the equations that describe the quadrature signal generator based on the second-order generalized integrator with linearly variable frequency is shown in

Figure 5.

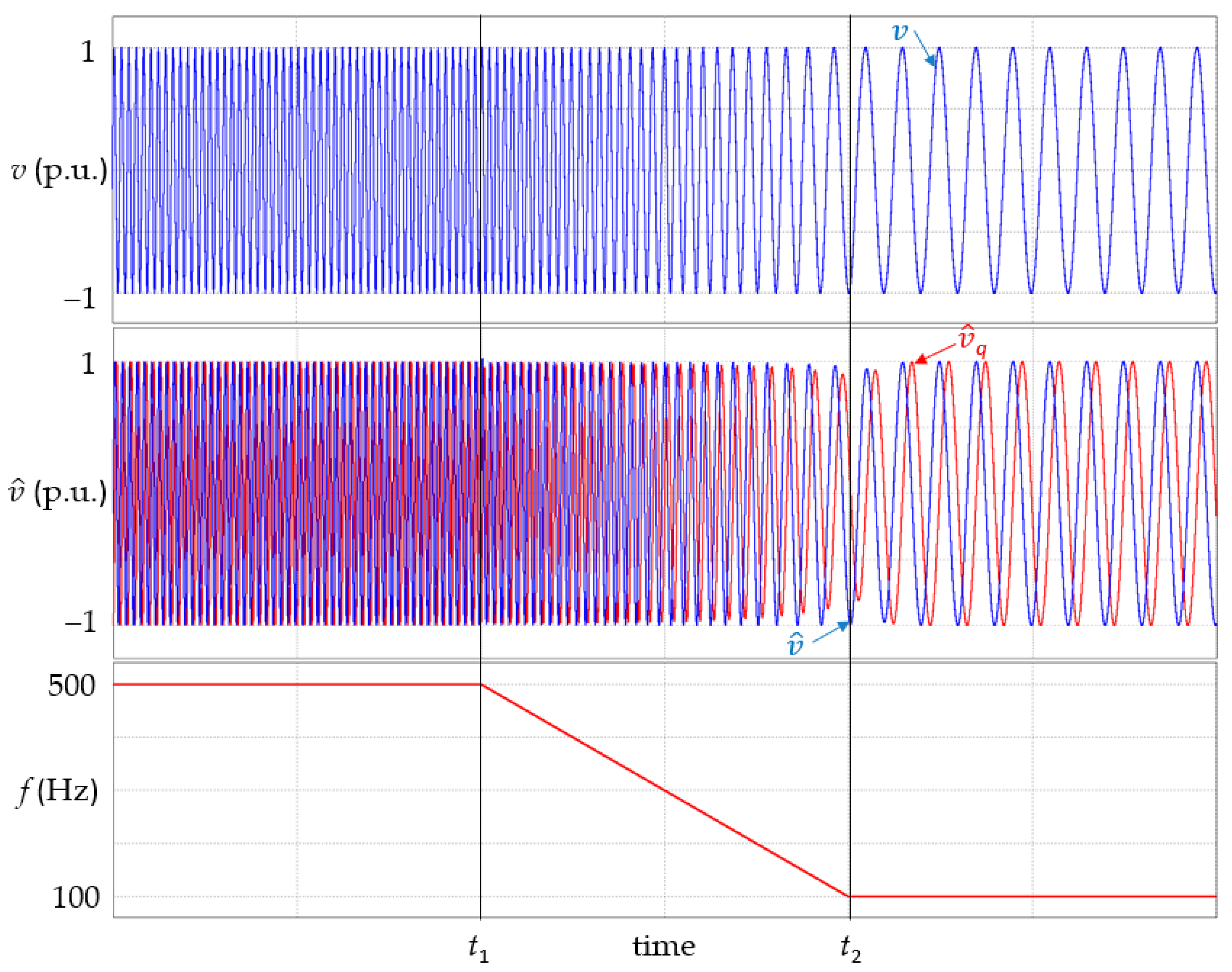

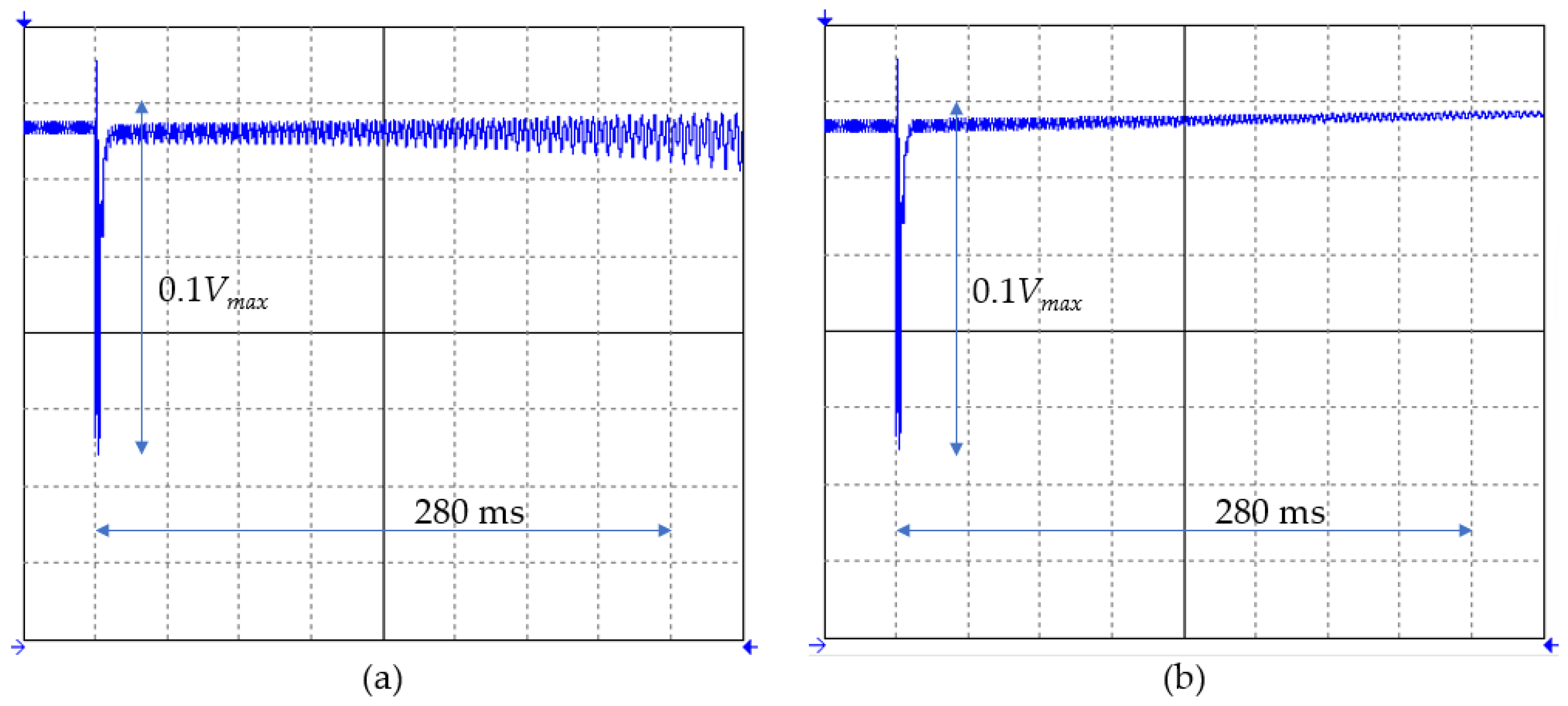

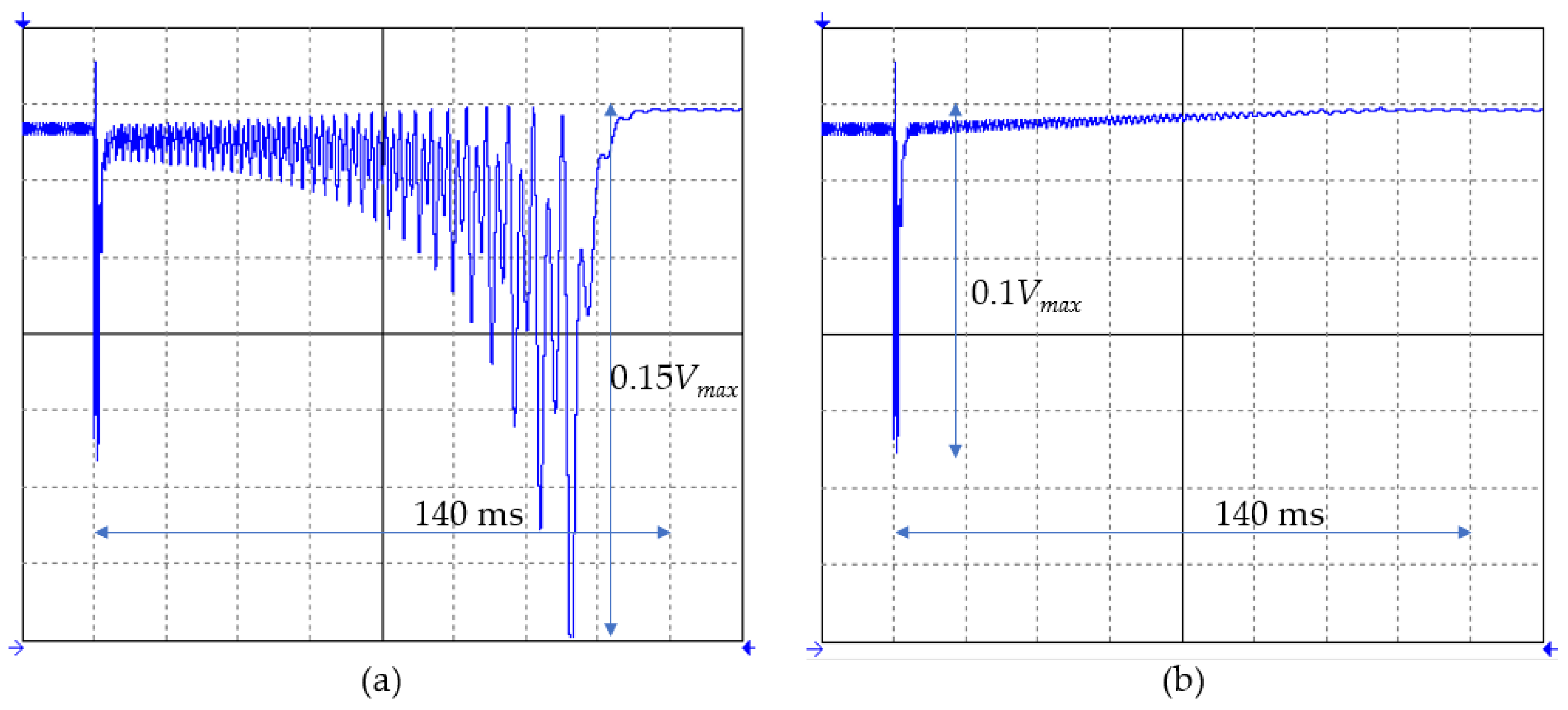

During the test, it was assumed that the input signal

v is in the form of a fixed frequency signal

fH = 500 Hz, which at time

t1 changes into a chirped signal with a linearly modulated frequency. The linear frequency modulation ends at time

t2, when the frequency of the chirped signal reaches

fL = 100 Hz. The waveforms of the input signal applied to the generalized second-order integrator and the profile of frequency changes are shown in

Figure 6.

To obtain quadrature signals based on the generalized second-order integrator shown in

Figure 5 it is necessary to include the frequency value in the signal processing. If the frequency changes, the Bode plots cannot be analyzed due to the fact that frequency is a fixed transmittance parameter. These signals can only be calculated from equations (19) and (20). In the case of a frequency change according to a known profile ω(

t), the profile can be inserted into the calculation instead of the fixed parameter. If a frequency variation profile is substituted for a fixed parameter, calculations will be performed to continuously update of its value. Intuitively, it may seem that, as a consequence of this update of frequency values, orthogonal signals should be correctly estimated. In

Figure 6, it can be observed that the calculated quadrature signals correctly track the frequency changes, but their amplitudes change as the input signal is reduced. This observation confirms the conclusions formulated for Equations (19) and (20).

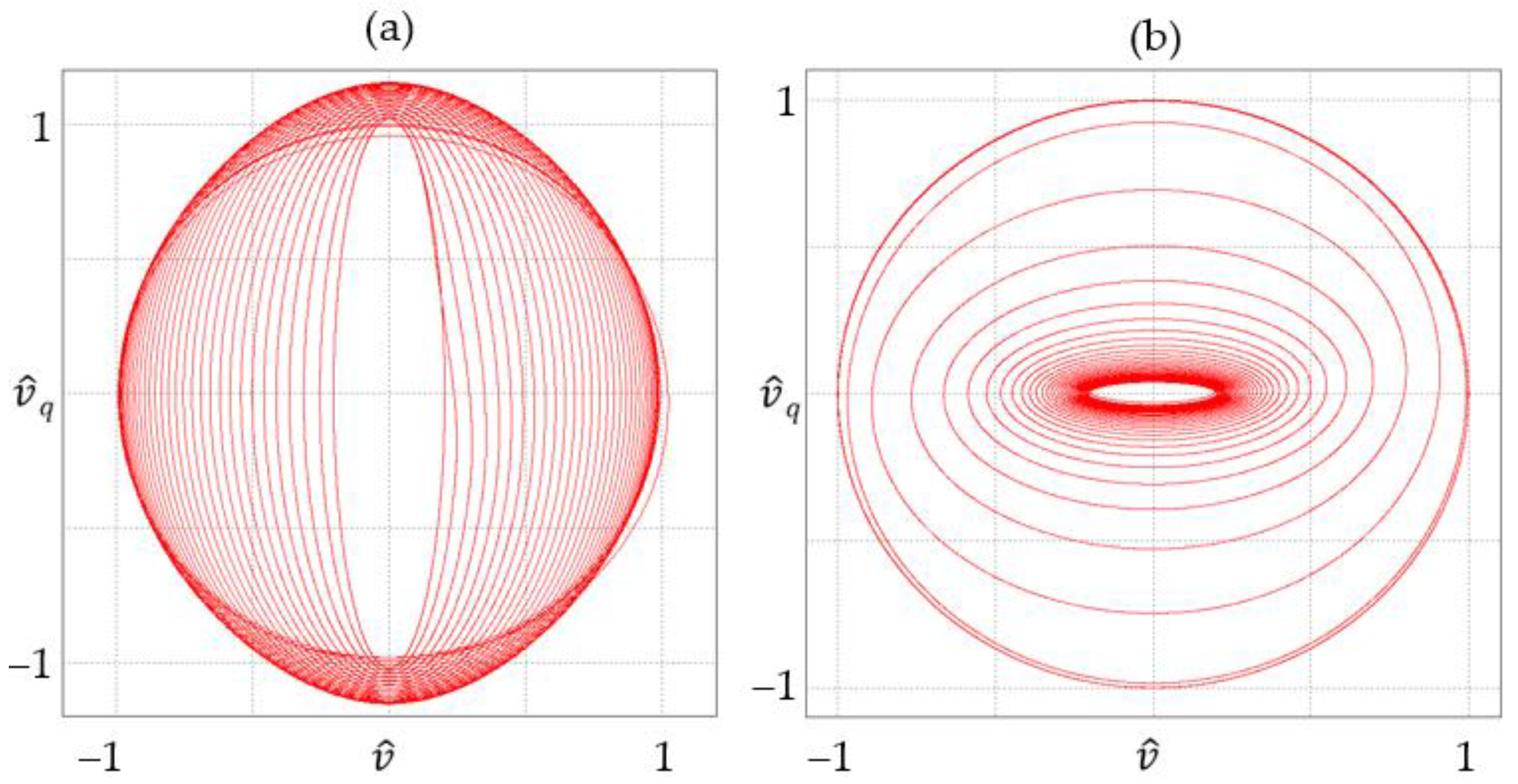

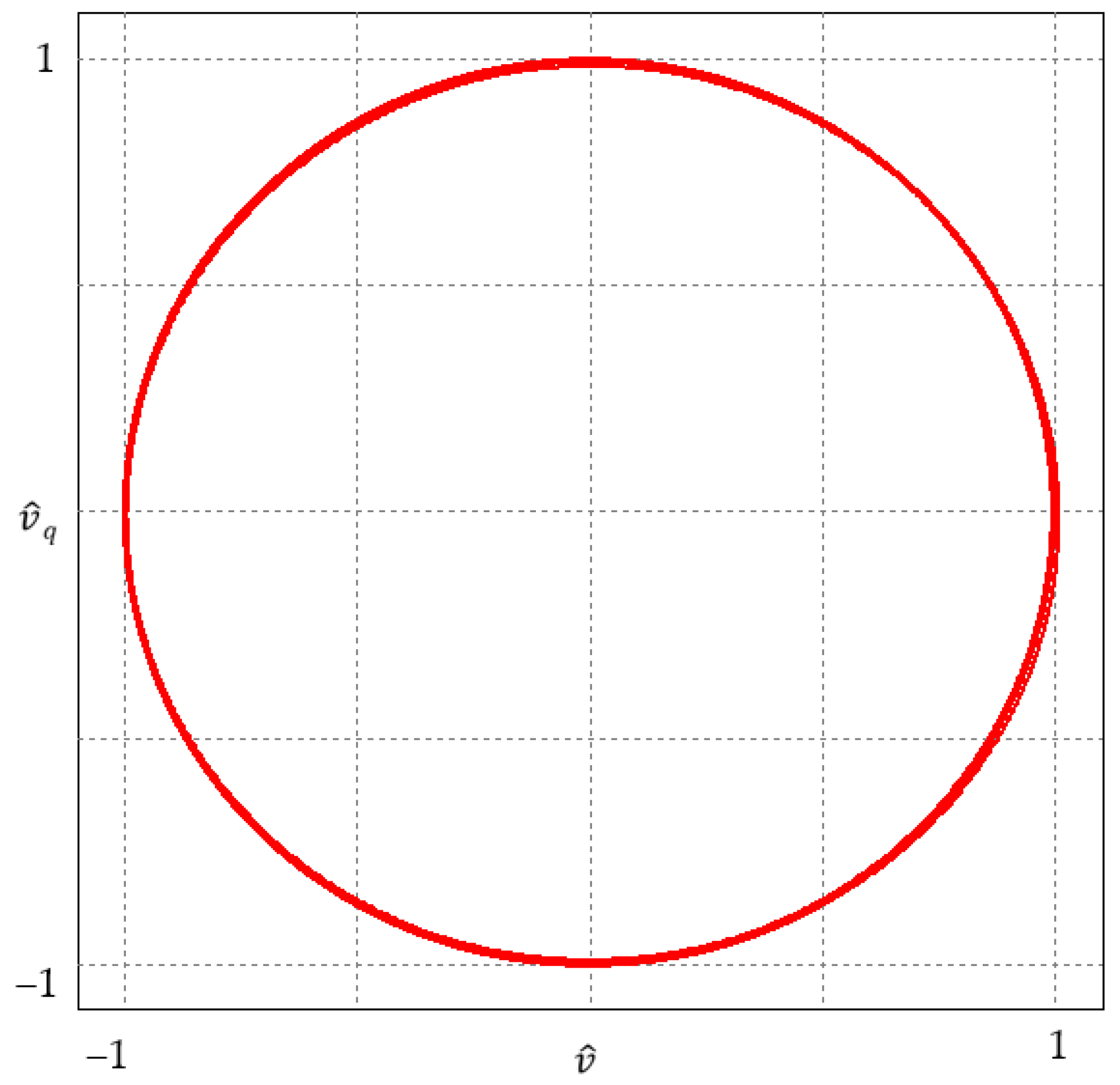

Properly estimated quadrature signals should be sinusoidal and have unit amplitude. In the case of the analyzed frequency variation profile, the trajectory resulting from the quadrature signals should always be a circle with a unit radius.

Figure 7 shows the trajectories resulting from the calculations of the generalized second-order integrator for a fixed frequency, corresponding to the initial frequency

fH and the final frequency

fL. Analysis of the obtained trajectories shows the change from circular to elliptical form or vice versa, remaining circular only for the frequency interval consistent with the set parameter. The densities of the paths of the elliptical envelope trajectory indicate at the same time the achievement of a steady state characterized by a non-unit amplitude value and non-orthogonality of the waveforms.

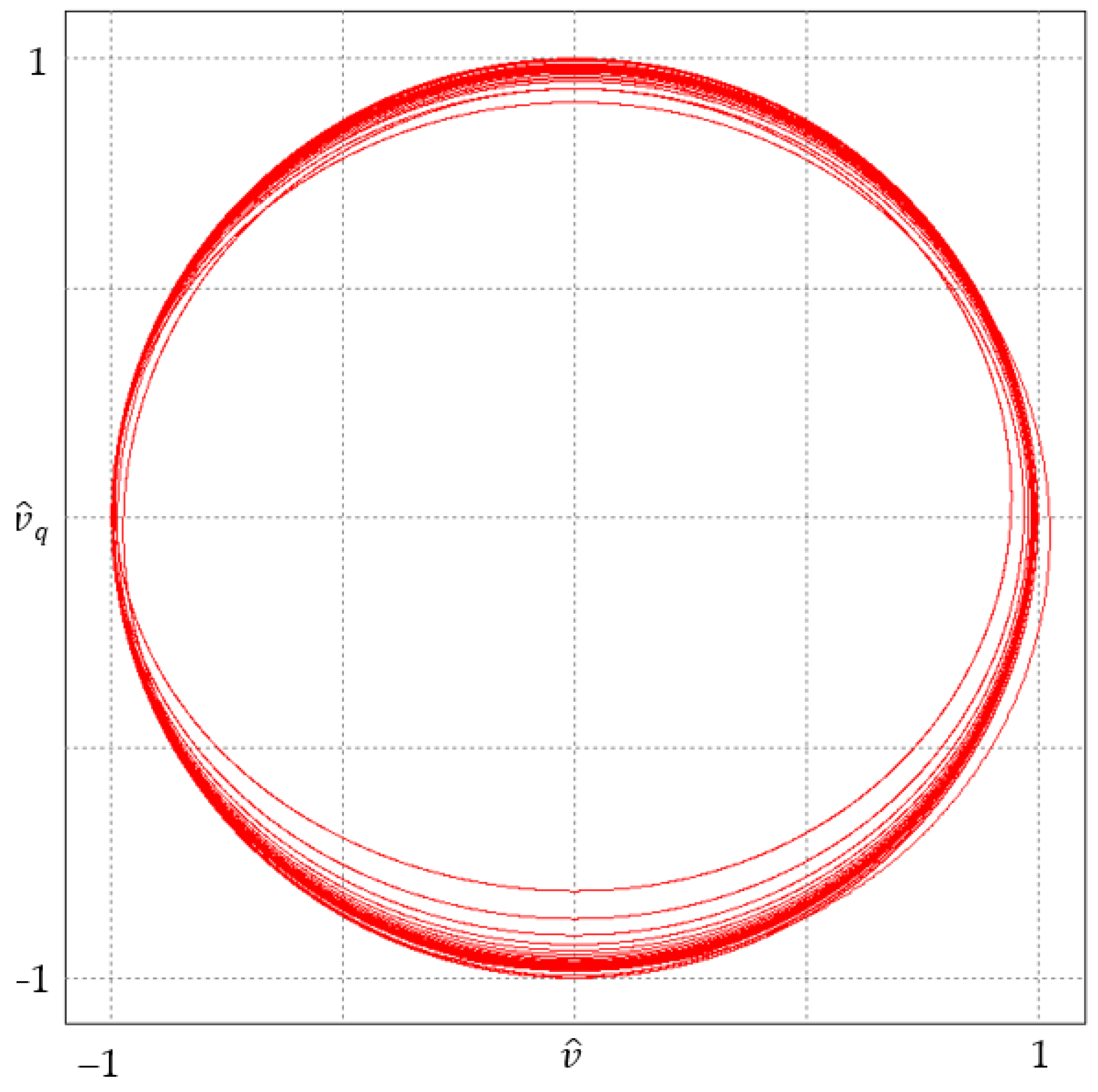

If a known frequency-change profile is substituted in place of a fixed parameter, the resulting trajectories are similar to circular trajectories. Path densities occur in the boundary of a single circle. As a consequence, it can be confirmed that the obtained quadrature waveforms will be correct during the analysed time interval, and the amplitude and phase changes will be transient. This case such the trajectory is shown in

Figure 8.

Due to the requirement of unit amplitude for quadrature signals, the approach presented to the implementation of the PLL system will result in errors in the calculation of the active and reactive components of the reference current.

This paper proposes a new quadrature signal generation method based on a generalized second-order integrator. The use of a known frequency variation profile does not give the desired effect of a circular trajectory, so the traditionally used PLL system was replaced by a reference shape signal generation (RSG) system. If the sinusoidal input signal is frequency modulated, then during the period of the signal, a change in the value of the characteristic frequency in the second-order integrator will always result in a deformation of the signal from the desired shape. In order to achieve the condition of unit amplitude with the correct phase shift, a method of synchronous latching of the current frequency value was used. Using this approach, where the current frequency value is latched for a time corresponding to the period of the input signal, will make the calculation of quadrature signals take place with a quasi-stationary parameter corresponding to the characteristic frequency of the second-order integrator.

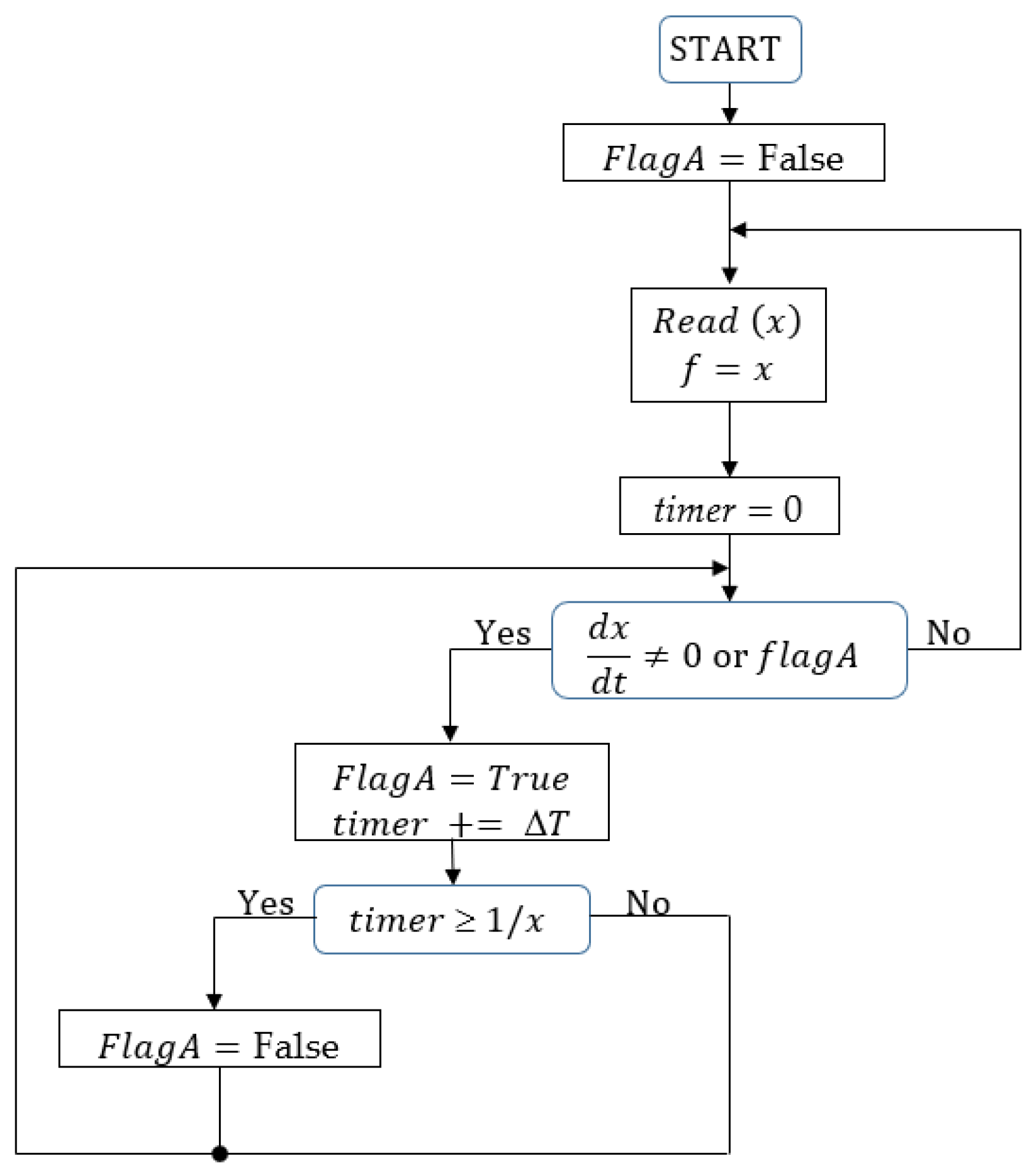

A flow chart of the proposed characteristic-frequency referencing system is shown in

Figure 9.

The proposed solution to the problem of changing the fixed transmittance parameter of the reference signal was based on a single-flag system. Systems based on flags are classic synchronization mechanisms used in concurrent programming. Their primary goal is to manage access to shared resources among multiple threads to prevent conflicts and ensure correct cooperation. The assumed binary flag (

FlagA) is set when the frequency change trajectory (

x) is changed. At this point, the timer is reset; after that the interval is measured, which is derived from the latched period value resulting from the set trajectory of frequency changes. The timer used measures time with a resolution resulting from the set interval Δ

T. After measuring the current value of the reference waveform, the frequency value is updated, and the new value is read from the set trajectory (

x). For the algorithm shown in

Figure 9 to work properly, the time relations associated with the calculations performed must be met. These relations are shown in

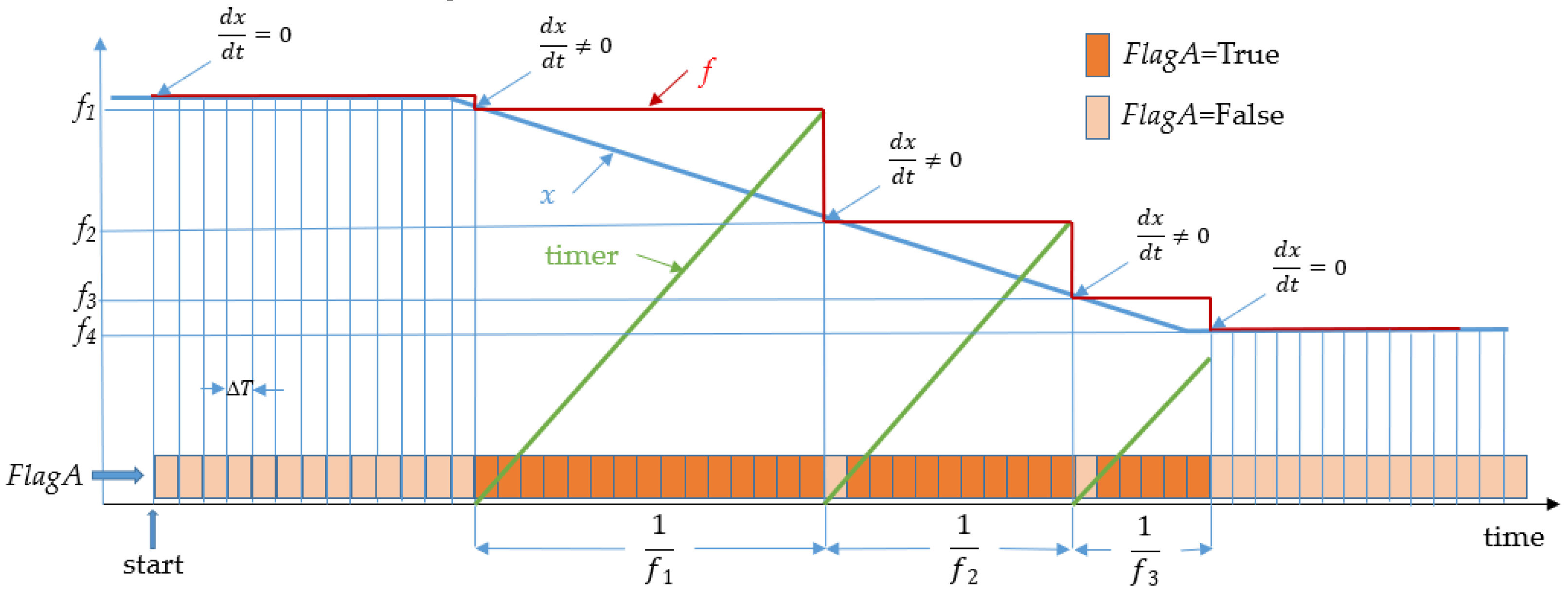

Figure 10.

Taking into account the proposed frequency change adaptation system explained in

Figure 10, the RSG system can be depicted as in

Figure 11. In the shown system, a pre-set frequency change trajectory is input to the quadrature signal generator via an adaptive zero-order hold block (AZOH). AZOH samples the input trajectory

x with varying frequency and holds the sampled value until the next synchronization cycle. The set frequency trajectory is marked in

Figure 11 as the red

x waveform and the resulting frequency is marked blue as the

f waveform.

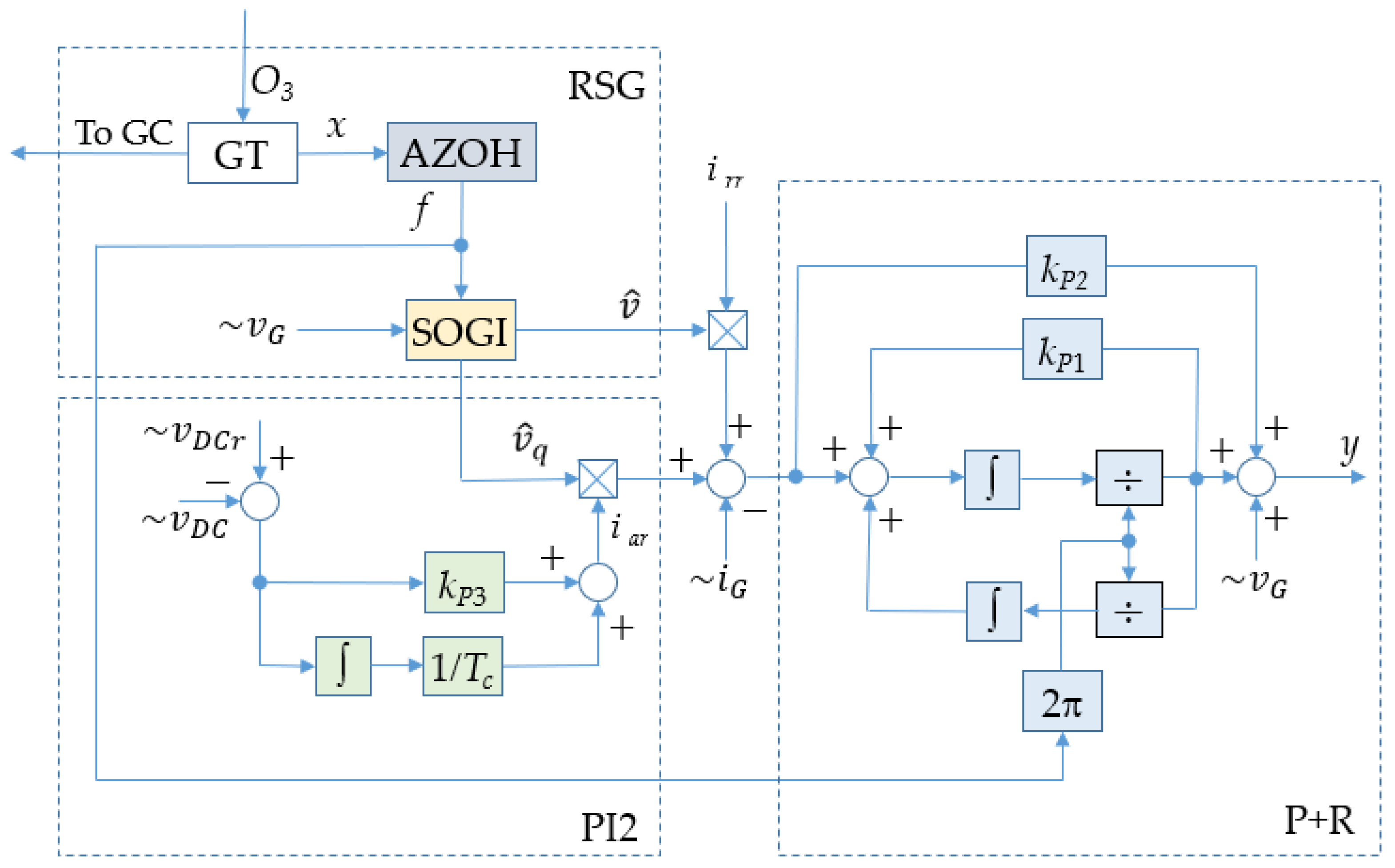

Taking into account the quadrature signals obtained from the proposed system, the waveform of the signal modulating the operation of the inverter switches was calculated using the proportional-resonant control algorithm. A diagram of the complete control system is shown in

Figure 12.

The control system of the grid inverter consists of three main structures to control the current with respect to a linearly varying frequency. A proportional-integral controller (PI2), which calculates the reference value of the ac component of the inverter current (

iar), is directly responsible for maintaining a constant voltage on Bus 1 (

vDC). According to Equation (3), the reference current of the inverter is determined, taking into account its reactive component (

irr). The reactive component is set by the higher-level system. The reference waveform of the inverter current is controlled in the proposed controller (P+R), with its output (

y) fed to the inverter modulator. In typical applications of proportional-resonant controllers, its settings depend on the resonant frequency, which corresponds to the frequency of the generated waveforms in the inverter. When the frequency changes, the proposed controller automatically adjusts as a function of f. This function is calculated in the RSG structure. The RSG consists of a generalized second-order integrator (SOGI), which is described by equations (16) and (17); an adaptive block (AZOH), which operates according to the diagram shown in

Figure 9; and a frequency trajectory generator (GT). GT is a structure to generate trajectories based on the status of the

O3 signal, as shown in

Figure 2. This trajectory is used in the adaptive tuning process of the controller and SOGI system and is involved in the control of the main generator through the control system (GC). The operation of the GC system is a separate issue and will not be discussed in this article.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of a photovoltaic converter system connected to an alternating-current voltage bus with varying frequency.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of a photovoltaic converter system connected to an alternating-current voltage bus with varying frequency.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of changes in frequency (a) and amplitude (b) of voltage at the point of connection of the grid converter.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of changes in frequency (a) and amplitude (b) of voltage at the point of connection of the grid converter.

Figure 3.

Generator voltage waveform at the connection point of the grid converter.

Figure 3.

Generator voltage waveform at the connection point of the grid converter.

Figure 4.

Bode plots of the generalized second-order integrator for frequency f = 500 Hz.

Figure 4.

Bode plots of the generalized second-order integrator for frequency f = 500 Hz.

Figure 5.

Block structure of the generalized second-order integrator.

Figure 5.

Block structure of the generalized second-order integrator.

Figure 6.

Voltage waveform v and quadrature signal estimates and q obtained by direct implementation of the frequency variation profile f in the generalized second-order integrator.

Figure 6.

Voltage waveform v and quadrature signal estimates and q obtained by direct implementation of the frequency variation profile f in the generalized second-order integrator.

Figure 7.

Trajectory of quadrature signals formed in the generalized second-order integrator for (a) ω = 500 Hz, (b) ω = 100 Hz.

Figure 7.

Trajectory of quadrature signals formed in the generalized second-order integrator for (a) ω = 500 Hz, (b) ω = 100 Hz.

Figure 8.

Trajectory of quadrature signals formed in a generalized second-order integrator for a given frequency variation profile.

Figure 8.

Trajectory of quadrature signals formed in a generalized second-order integrator for a given frequency variation profile.

Figure 9.

Flow chart of the proposed characteristic frequency reference system.

Figure 9.

Flow chart of the proposed characteristic frequency reference system.

Figure 10.

Graphic illustration describing the adaptive zero-order hold block process.

Figure 10.

Graphic illustration describing the adaptive zero-order hold block process.

Figure 11.

Structure of the RSG system and waveforms describing the operation of AZOH.

Figure 11.

Structure of the RSG system and waveforms describing the operation of AZOH.

Figure 12.

The proposed system of adaptive regulation of the grid converter.

Figure 12.

The proposed system of adaptive regulation of the grid converter.

Figure 13.

Test stand designed for testing grid-tied inverters.

Figure 13.

Test stand designed for testing grid-tied inverters.

Figure 14.

Trajectory of quadrature signals formed in a generalized second-order integrator for a proposed RSG with AZOH.

Figure 14.

Trajectory of quadrature signals formed in a generalized second-order integrator for a proposed RSG with AZOH.

Figure 15.

The trajectory modulus of quadrature signals with a frequency drop of 1.42 Hz per millisecond.

Figure 15.

The trajectory modulus of quadrature signals with a frequency drop of 1.42 Hz per millisecond.

Figure 16.

The trajectory modulus of quadrature signals with a frequency drop of 2.84 Hz per millisecond.

Figure 16.

The trajectory modulus of quadrature signals with a frequency drop of 2.84 Hz per millisecond.

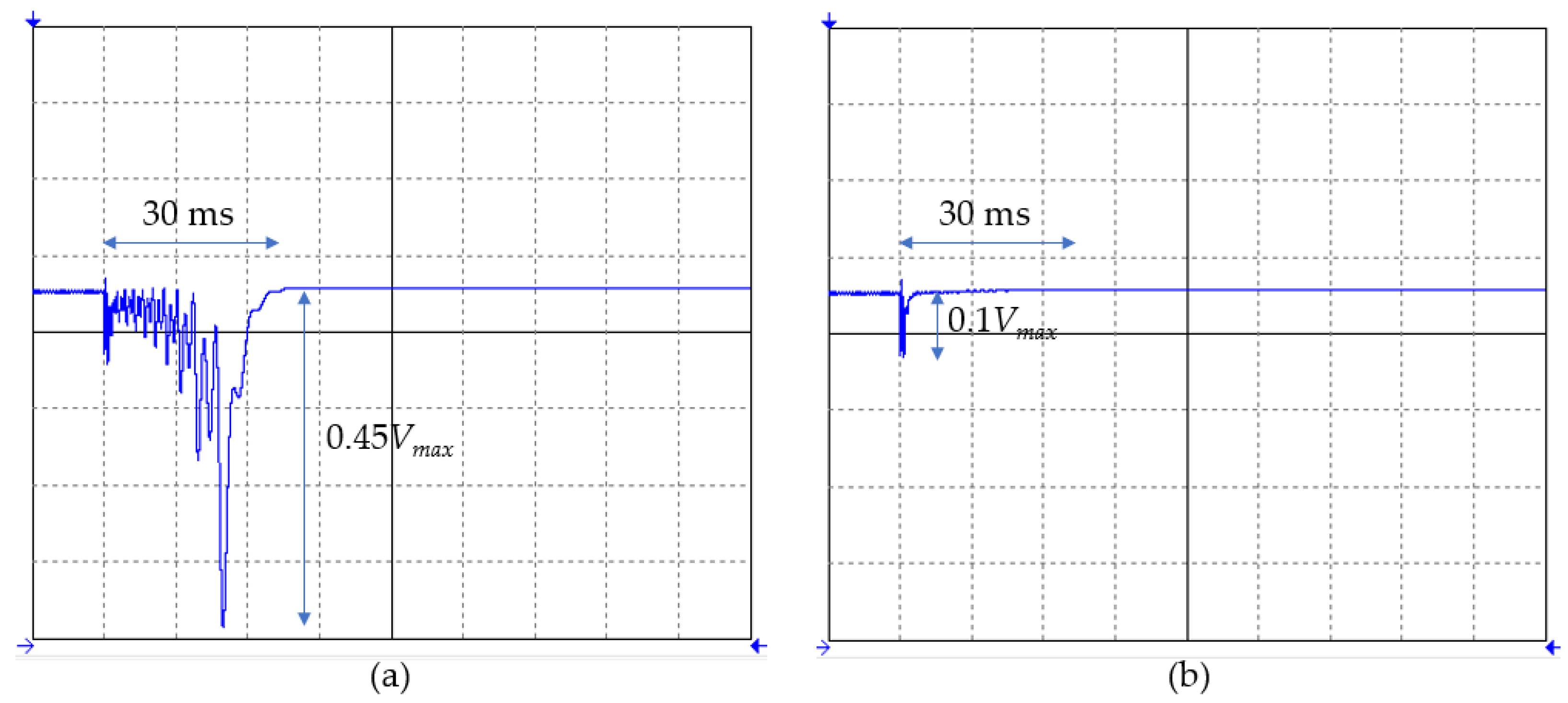

Figure 17.

The trajectory modulus of quadrature signals with a frequency drop of 13.3 Hz per millisecond.

Figure 17.

The trajectory modulus of quadrature signals with a frequency drop of 13.3 Hz per millisecond.

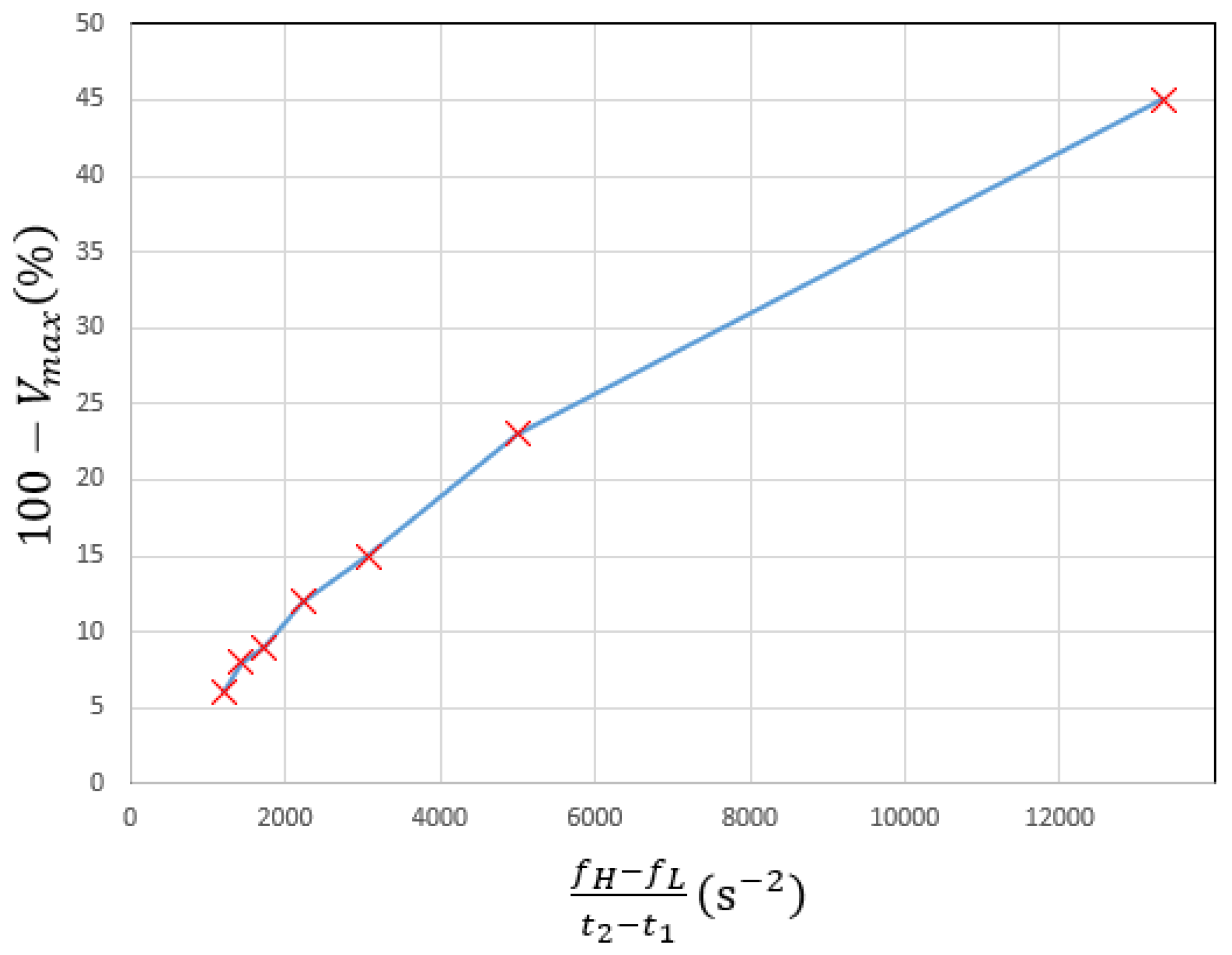

Figure 18.

Percentage change in amplitude of the quadrature signal versus steepness of frequency change.

Figure 18.

Percentage change in amplitude of the quadrature signal versus steepness of frequency change.

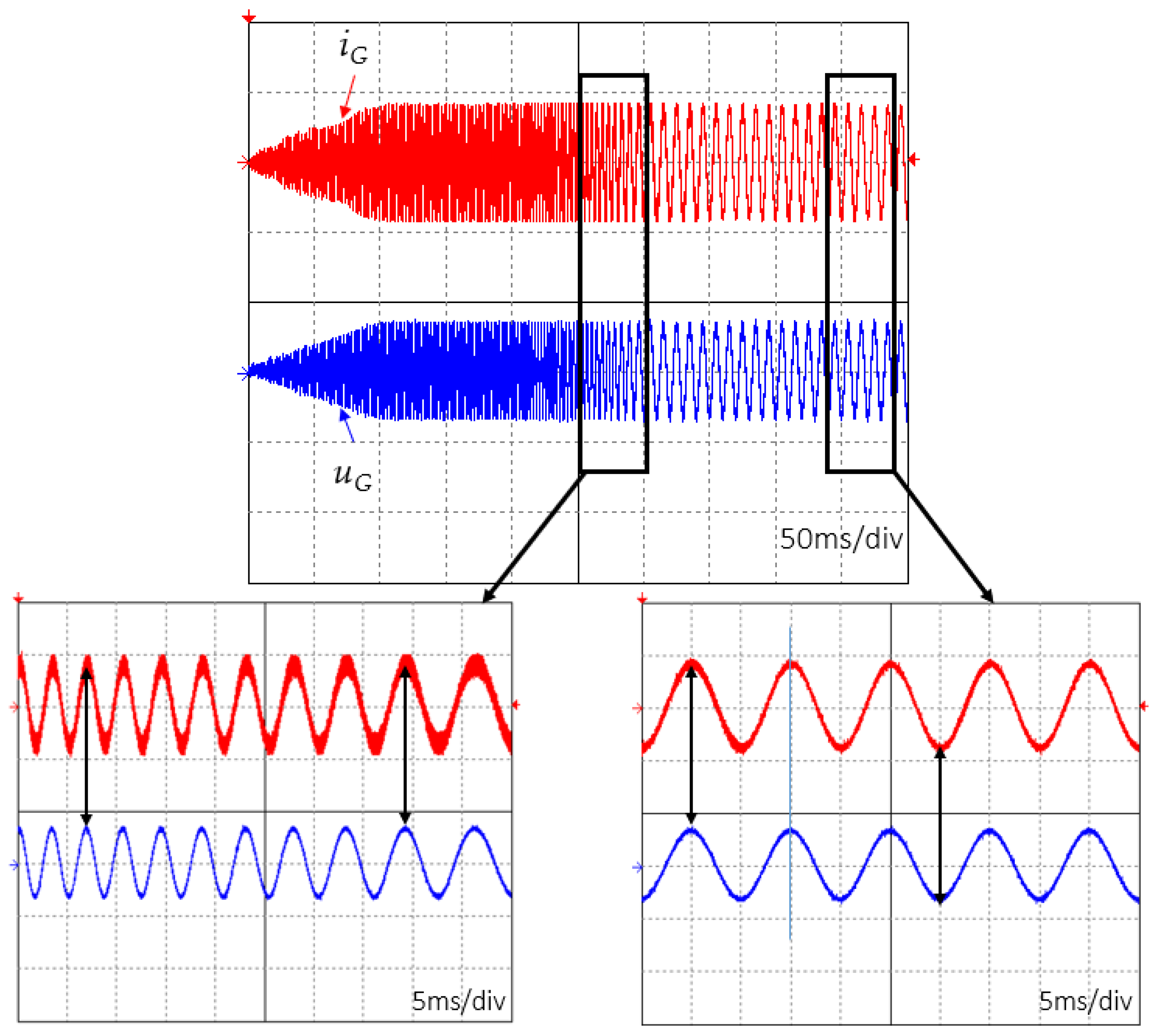

Figure 19.

Current and voltage waveforms of the mains inverter measured on bus 2 with nonzero active component and zero reactive component.

Figure 19.

Current and voltage waveforms of the mains inverter measured on bus 2 with nonzero active component and zero reactive component.

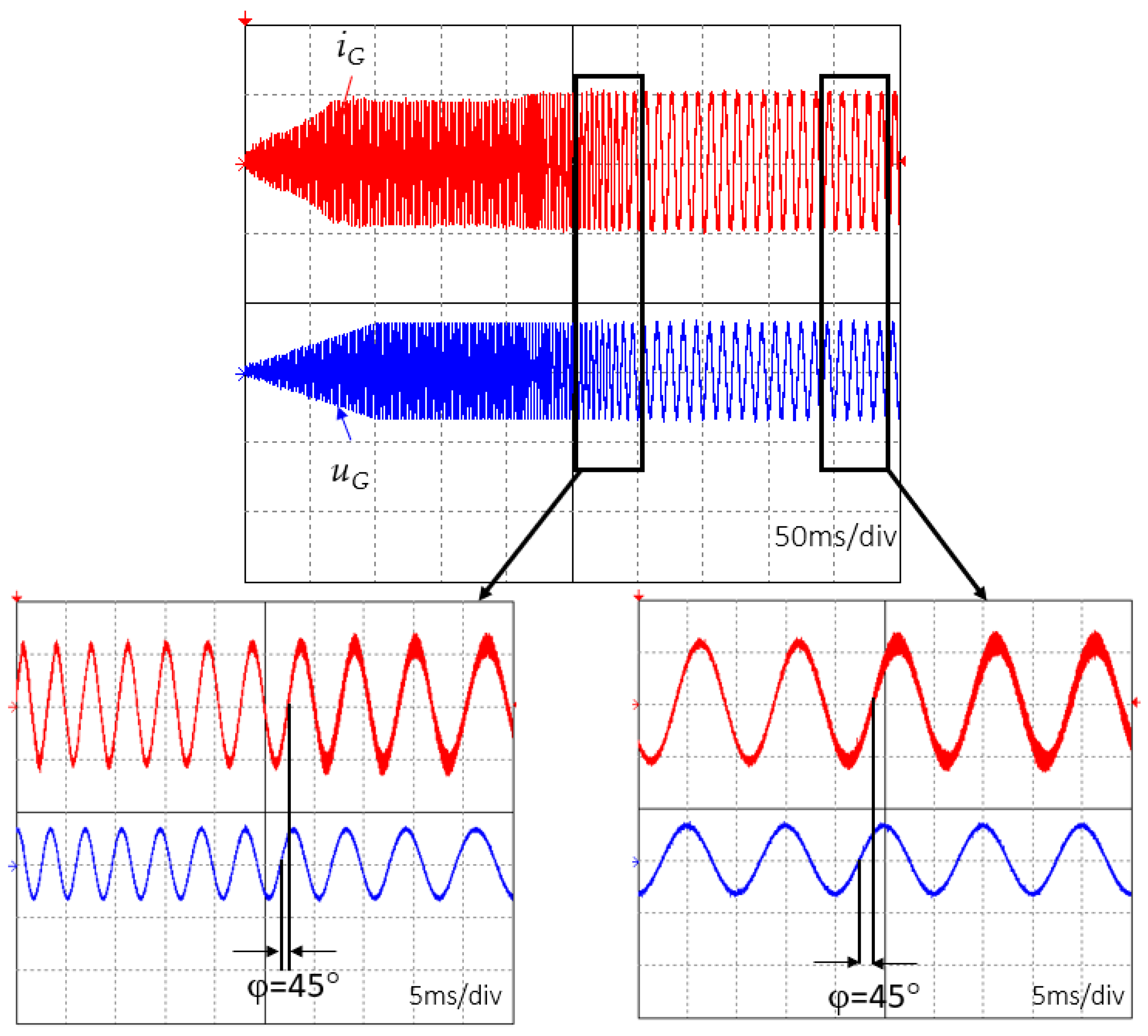

Figure 20.

Current and voltage waveforms of the mains inverter measured on bus 2 with the same active and reactive component.

Figure 20.

Current and voltage waveforms of the mains inverter measured on bus 2 with the same active and reactive component.

Table 1.

Control system parameters.

Table 1.

Control system parameters.

| PI |

PI2 |

P+R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|