Submitted:

11 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Aim and Contribution

- By using a simple dynamic model of the power system, we demonstrate the potential for increasing the maximum allowable power of a TL connecting two PSs.

- Via an abridged dynamic model and the parameters of the power systems of the Baltic Sea region, we show the possibility of maintaining stability during sudden outages of large energy sources.

- By utilising data from the Nordic Power Exchange (Nord Pool) market [43], we conduct an example of assessing the economic efficiency of the proposed approach.

1.3. The Structure of the Paper

2. Materials and Methods

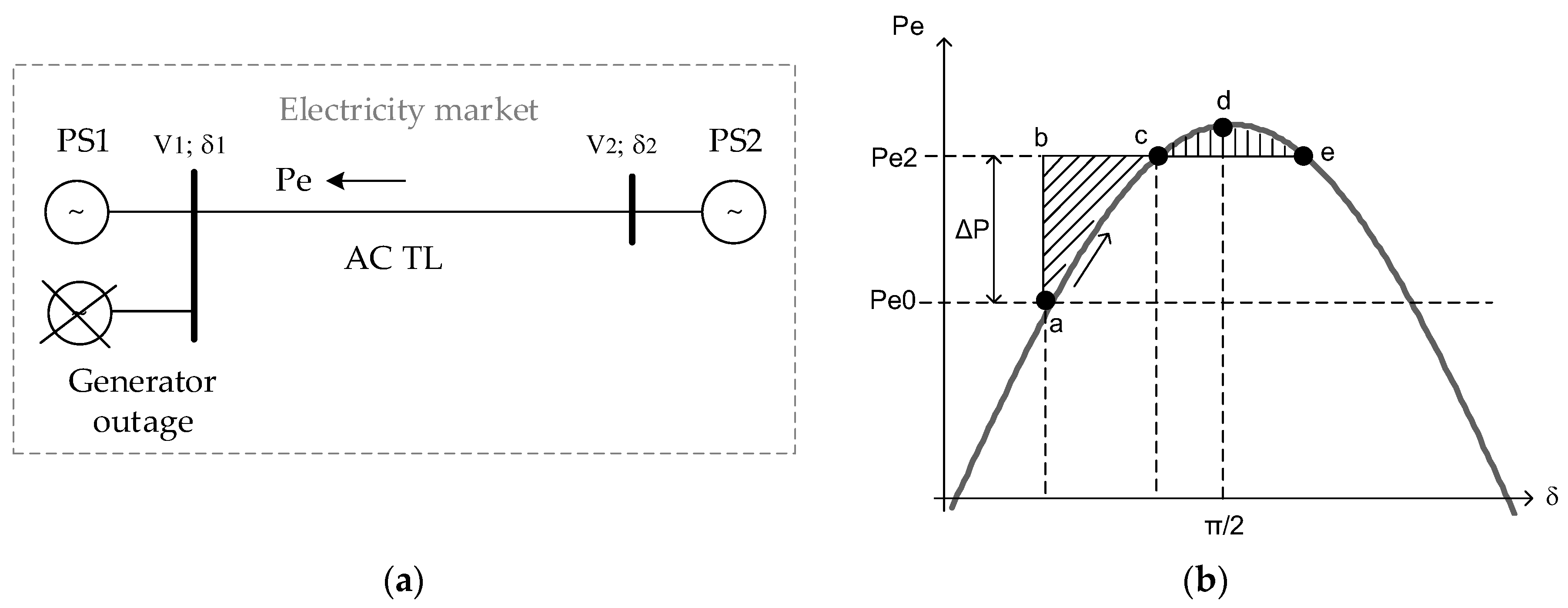

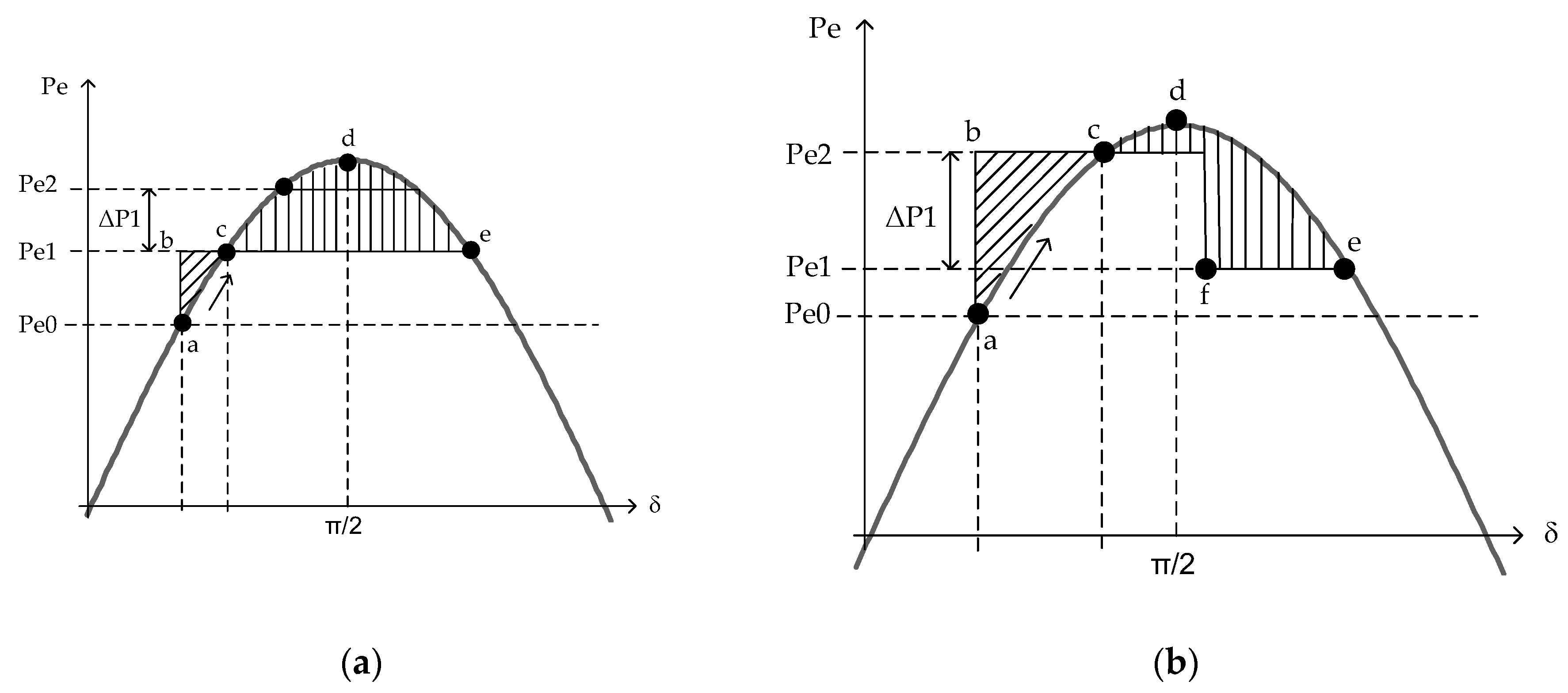

2.1. Instability Arising from Generation Surges

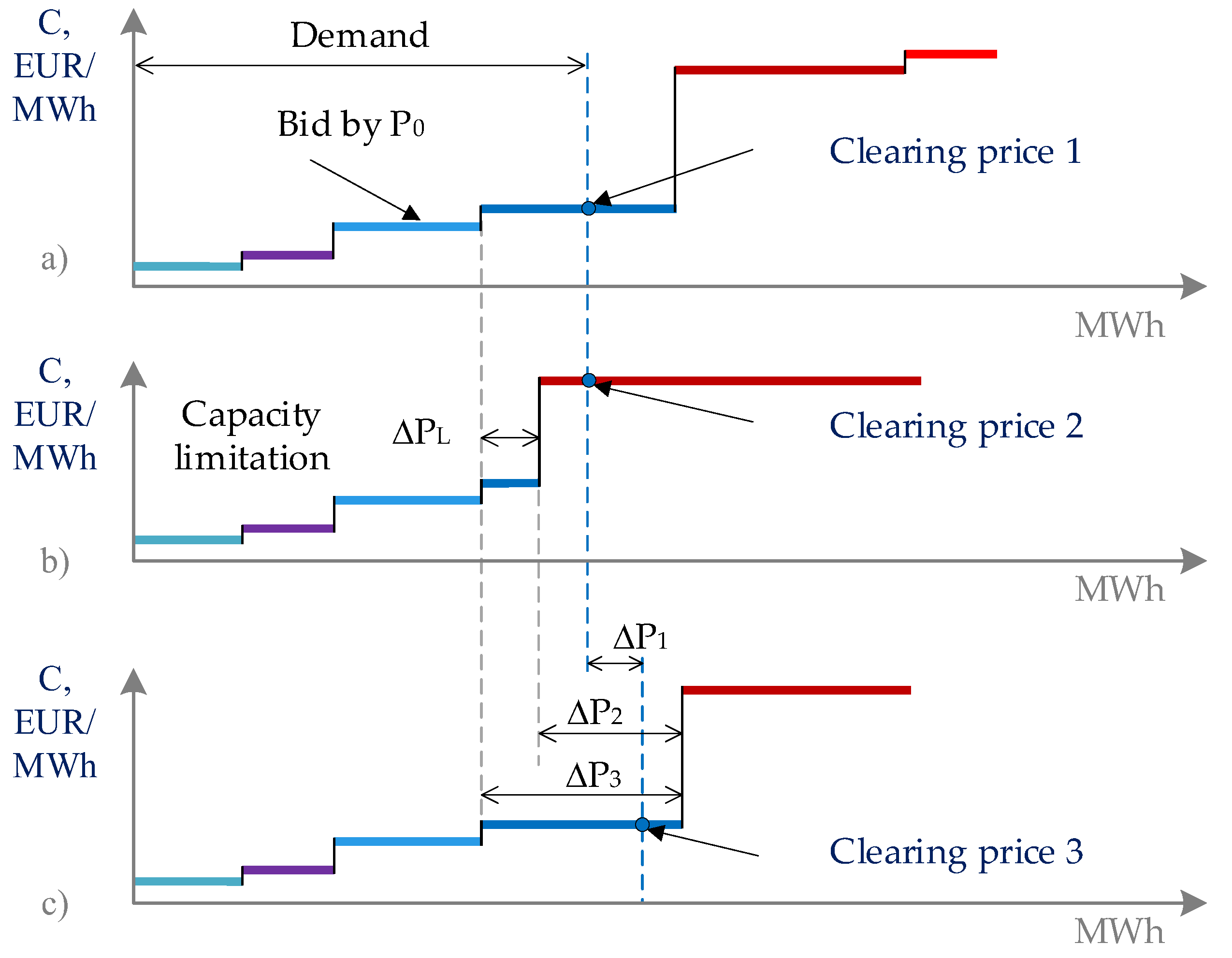

- Minimising energy generation costs while adhering to specified constraints, some of which relate to stability conditions.

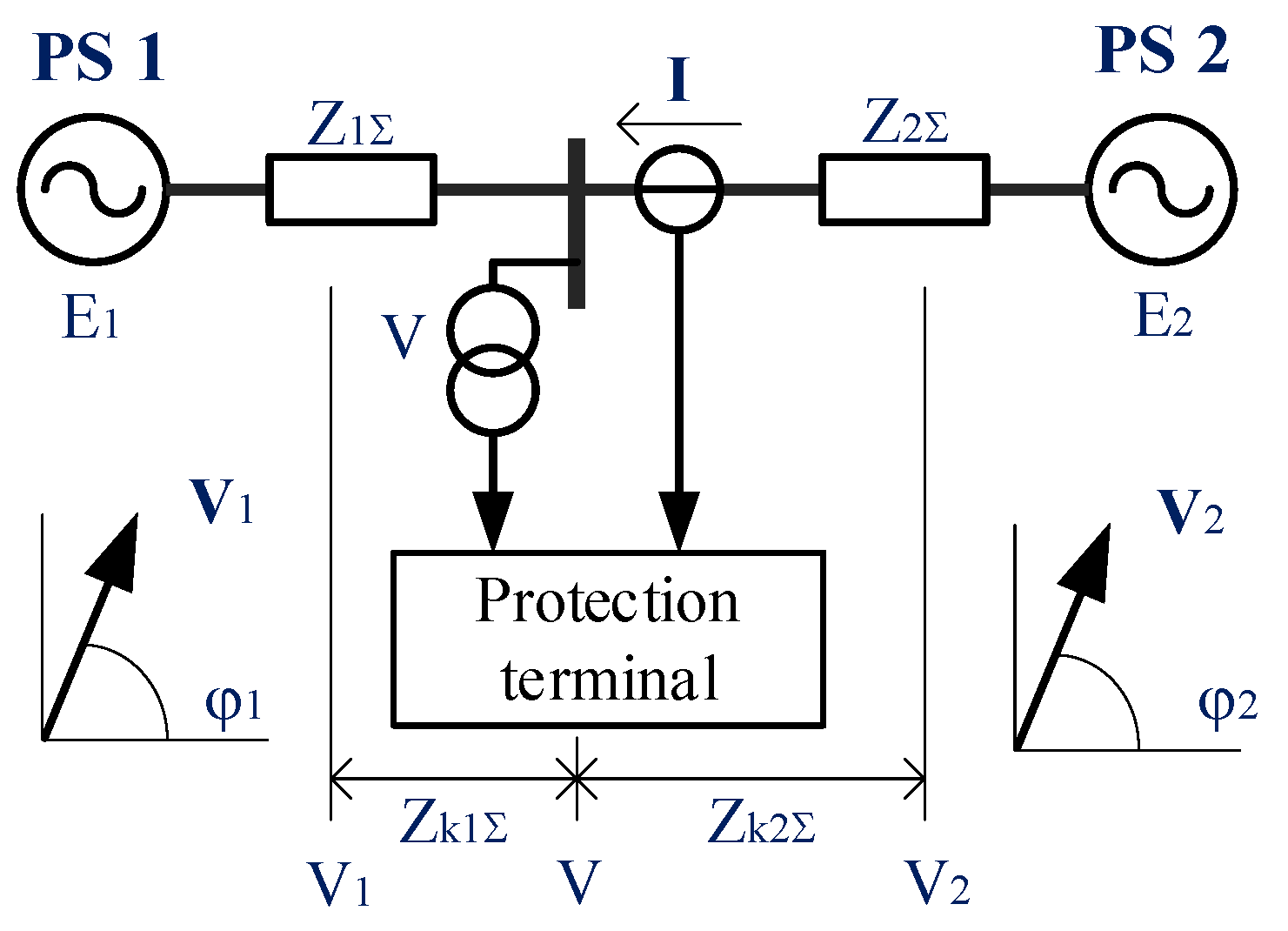

2.2. Fixing a Large-Scale Imbalance. Out-of-Step Protection

- An event-based special protection scheme is typically activated by changes in the position of switches, promptly disconnecting loads or generators immediately after a predetermined outage occurs [42]. In contrast, a response-driven special protection scheme incorporates measurement elements that introduce time delays.

- An event-based SPS typically necessitates a communication system for transmitting control signals, whereas a response-driven scheme, such as a UFLS, conducts local parameter measurements and initiates local shedding actions. Both schemes involve shedding of loads or generators and can be implemented either together or separately.

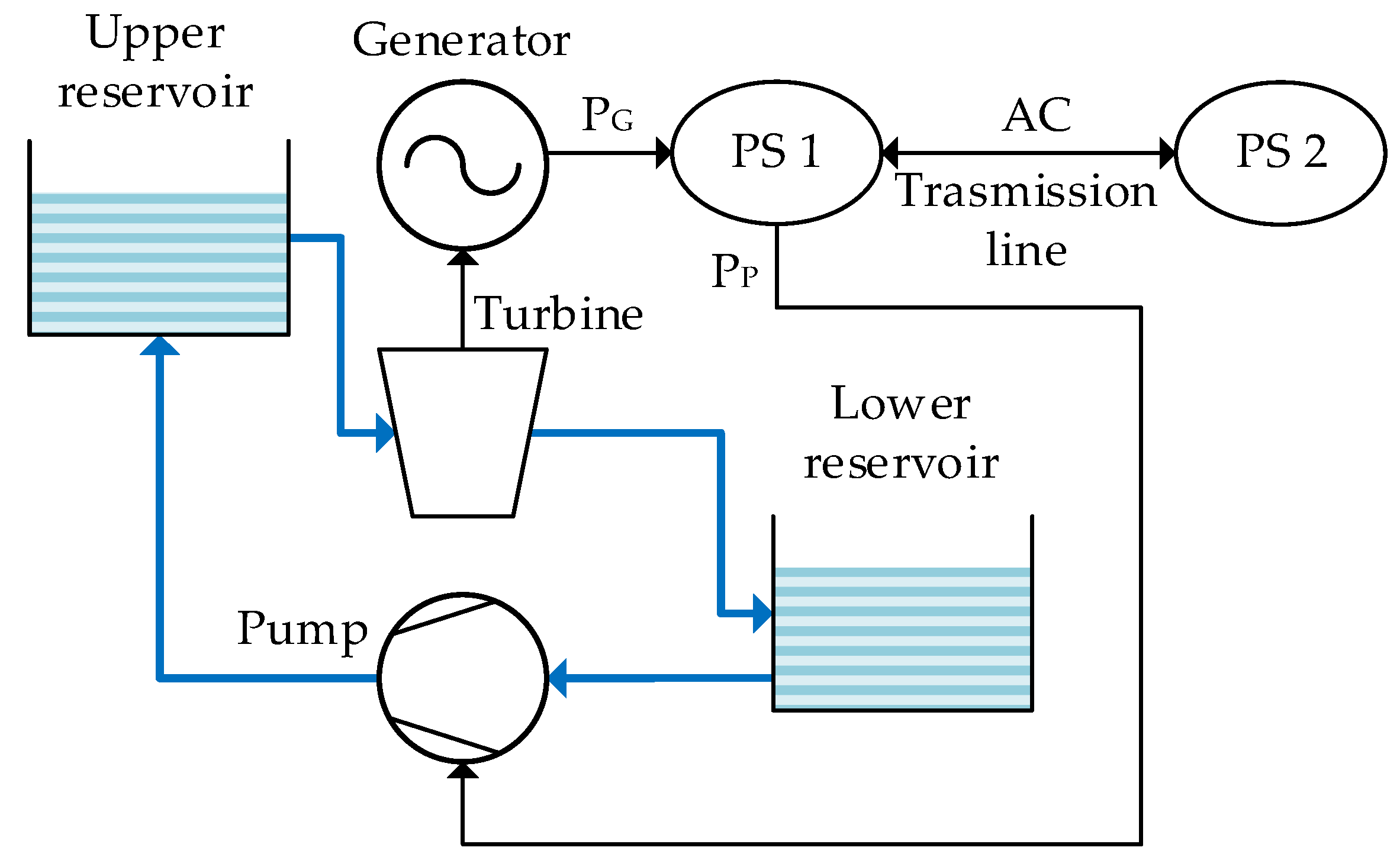

2.3. A pumped Hydroelectric Storage Plant as a Rapid Power Injection System

2.4. Modelling Methodology and Tools

- Determination of commitments for generator units.

- Verification of compliance with technical and environmental restrictions.

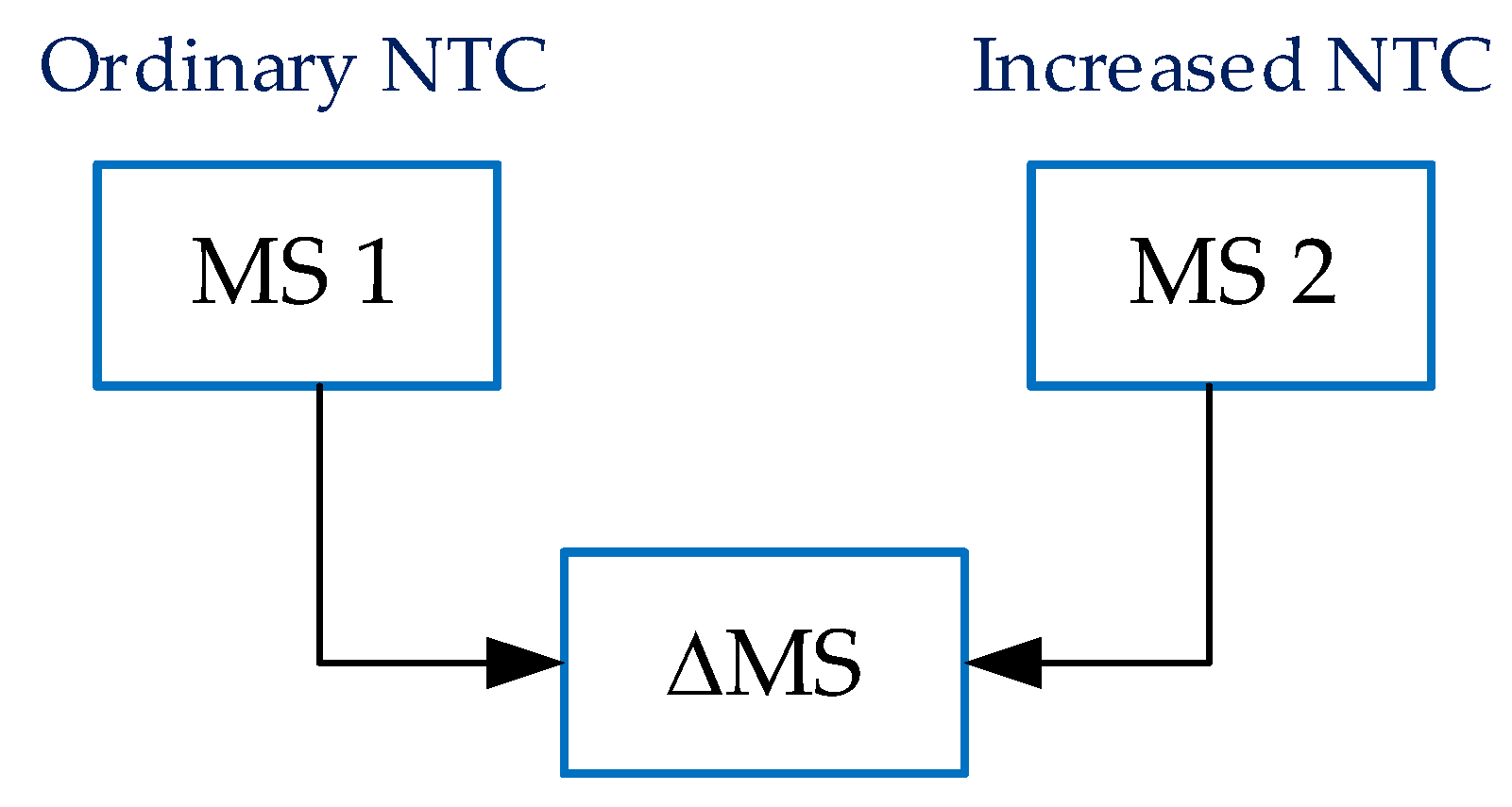

- A simulation of the system without the simultaneous operation of the generator and pump of the PHSPP (ordinary network transfer capacity (NTC)).

- A system with simultaneous operation of the generator and pump of the PHSPP (increased NTC).

3. Results: Case Studies

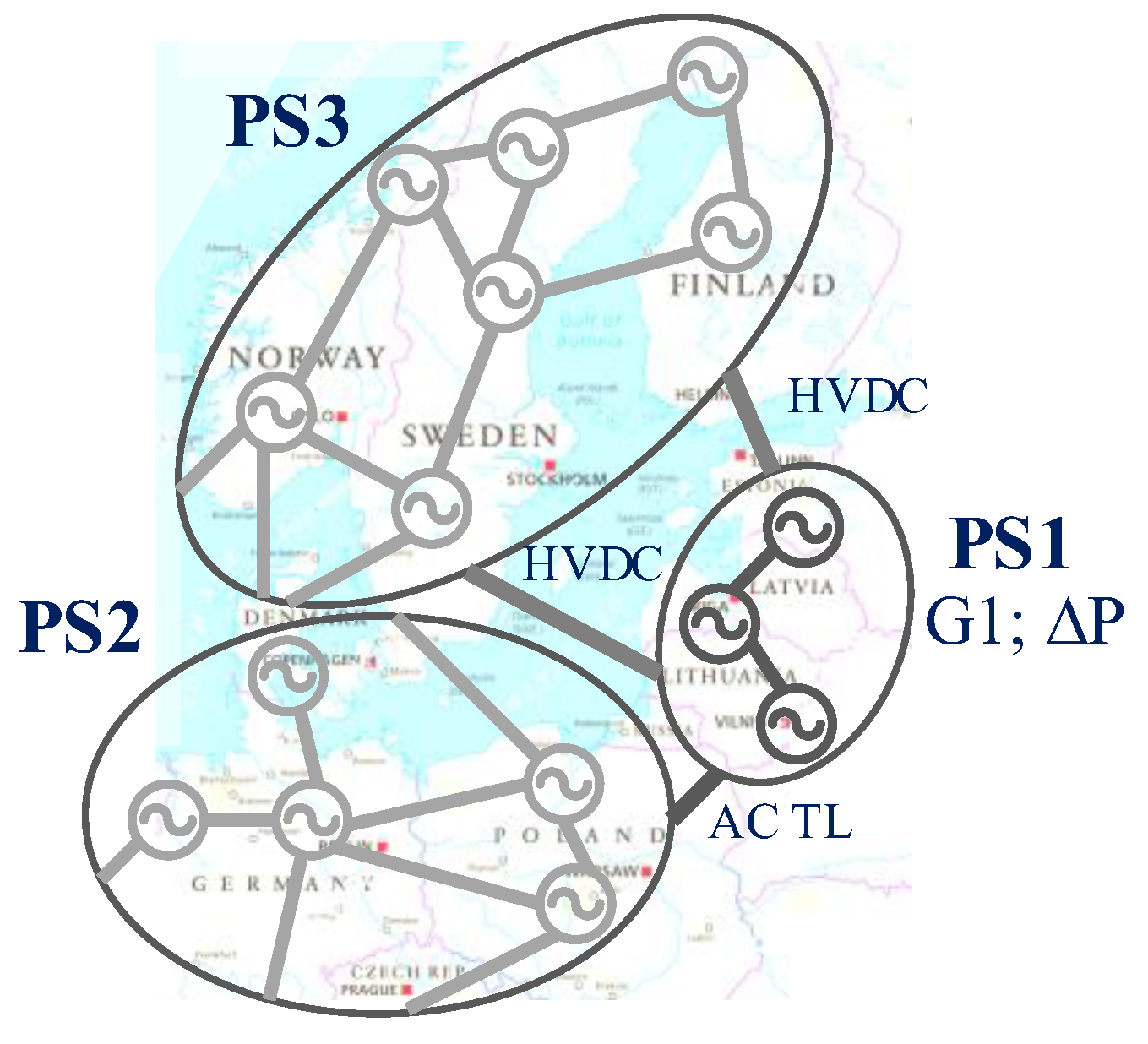

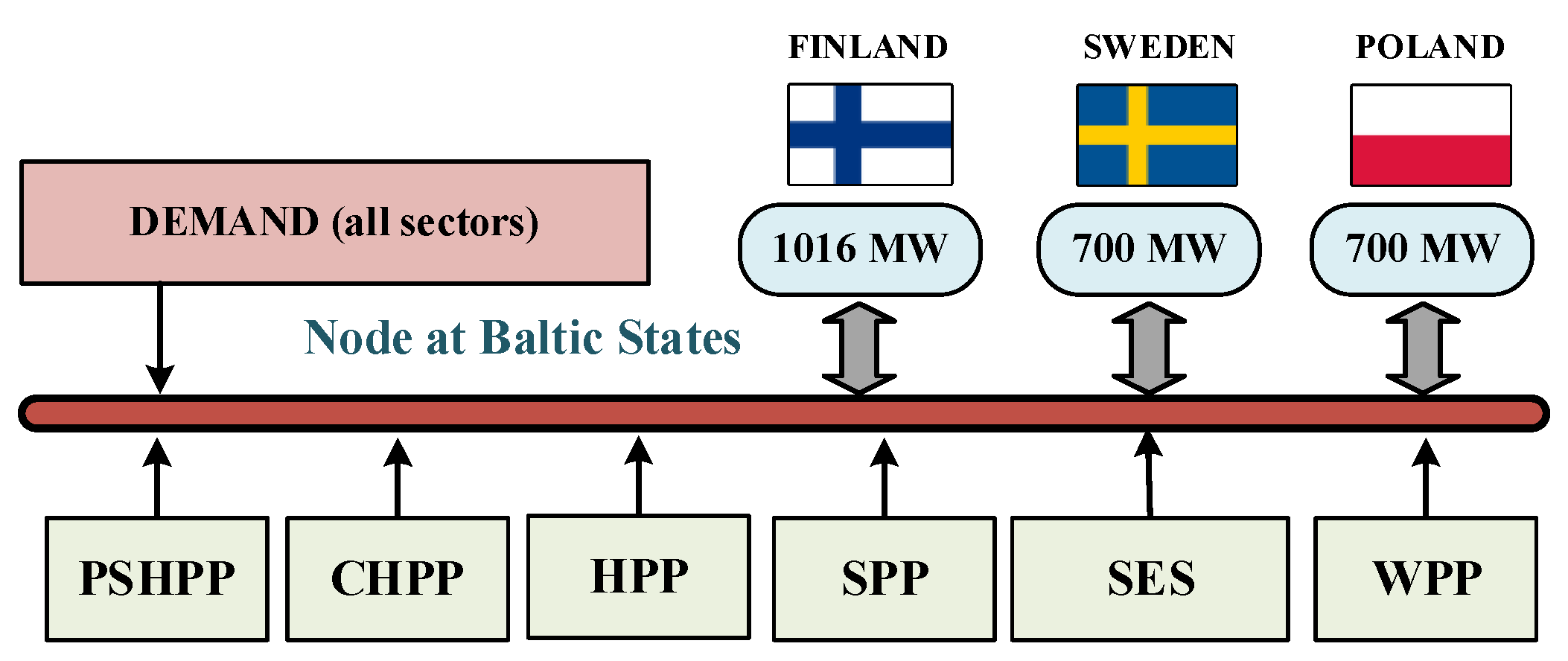

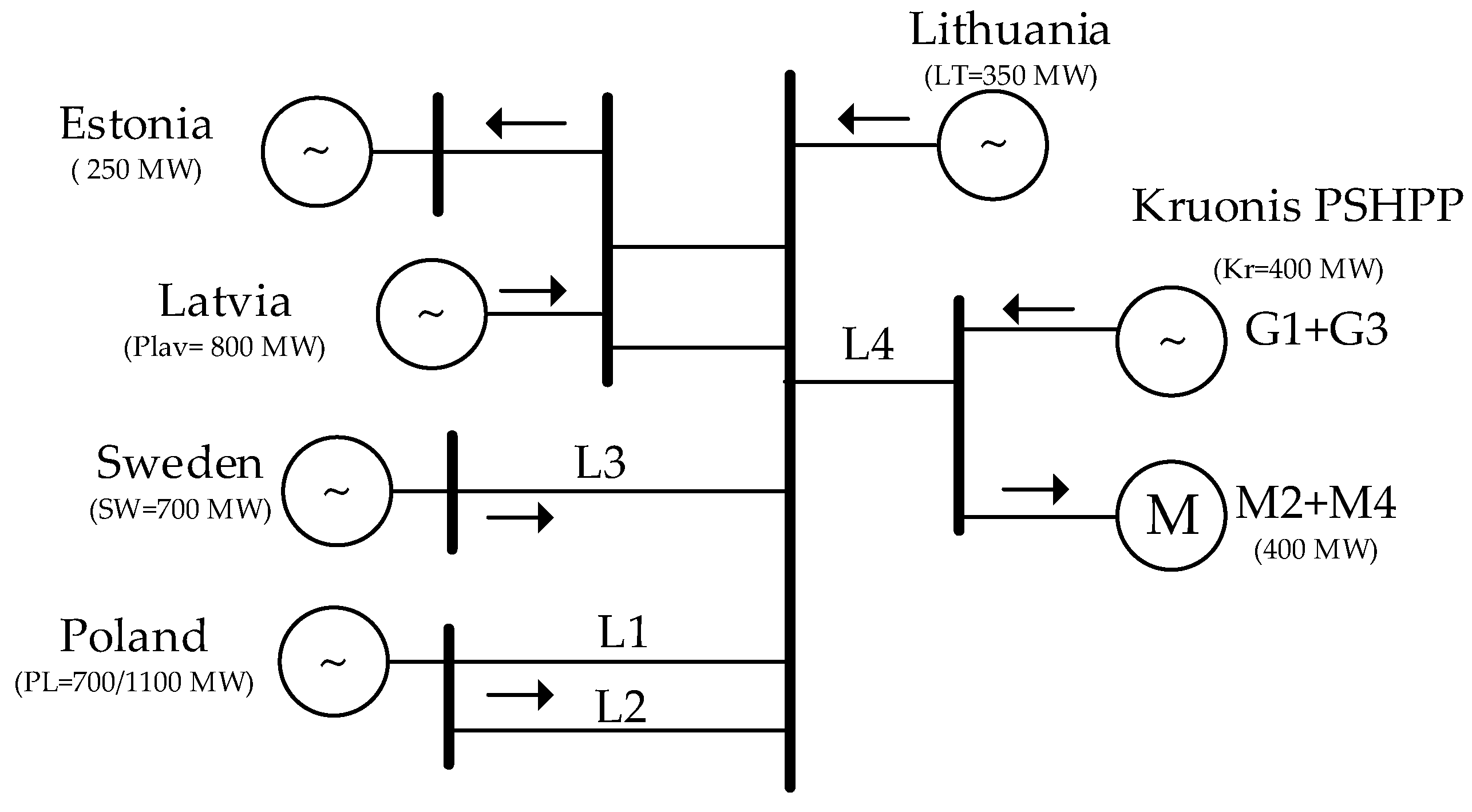

3.1. The Baltic Power System

3.2. Modelling of the Baltic Power Grid

3.3. Simulation Results

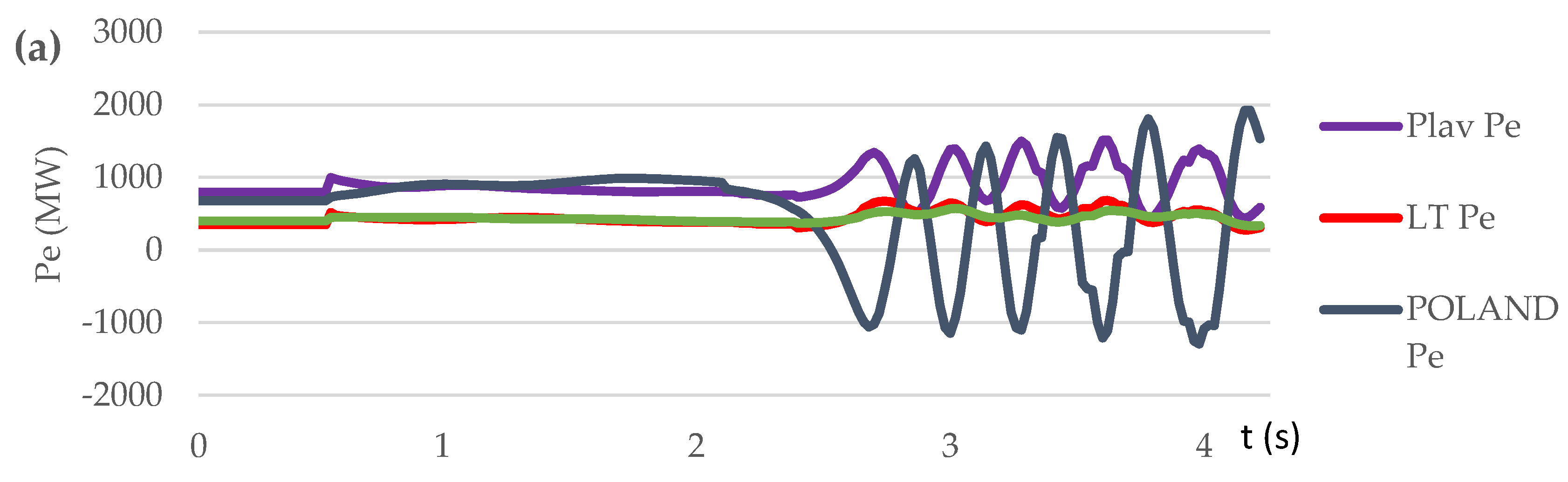

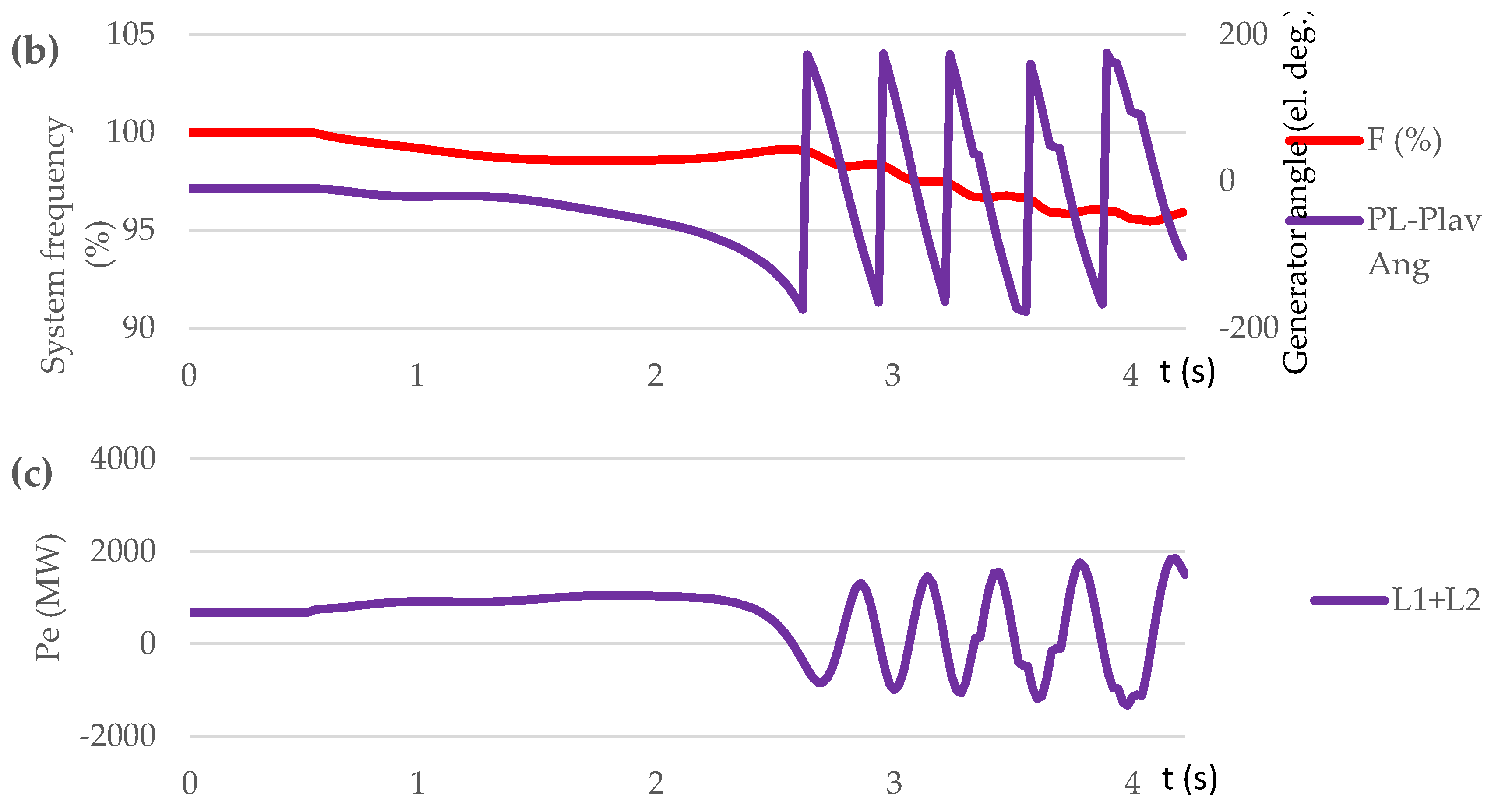

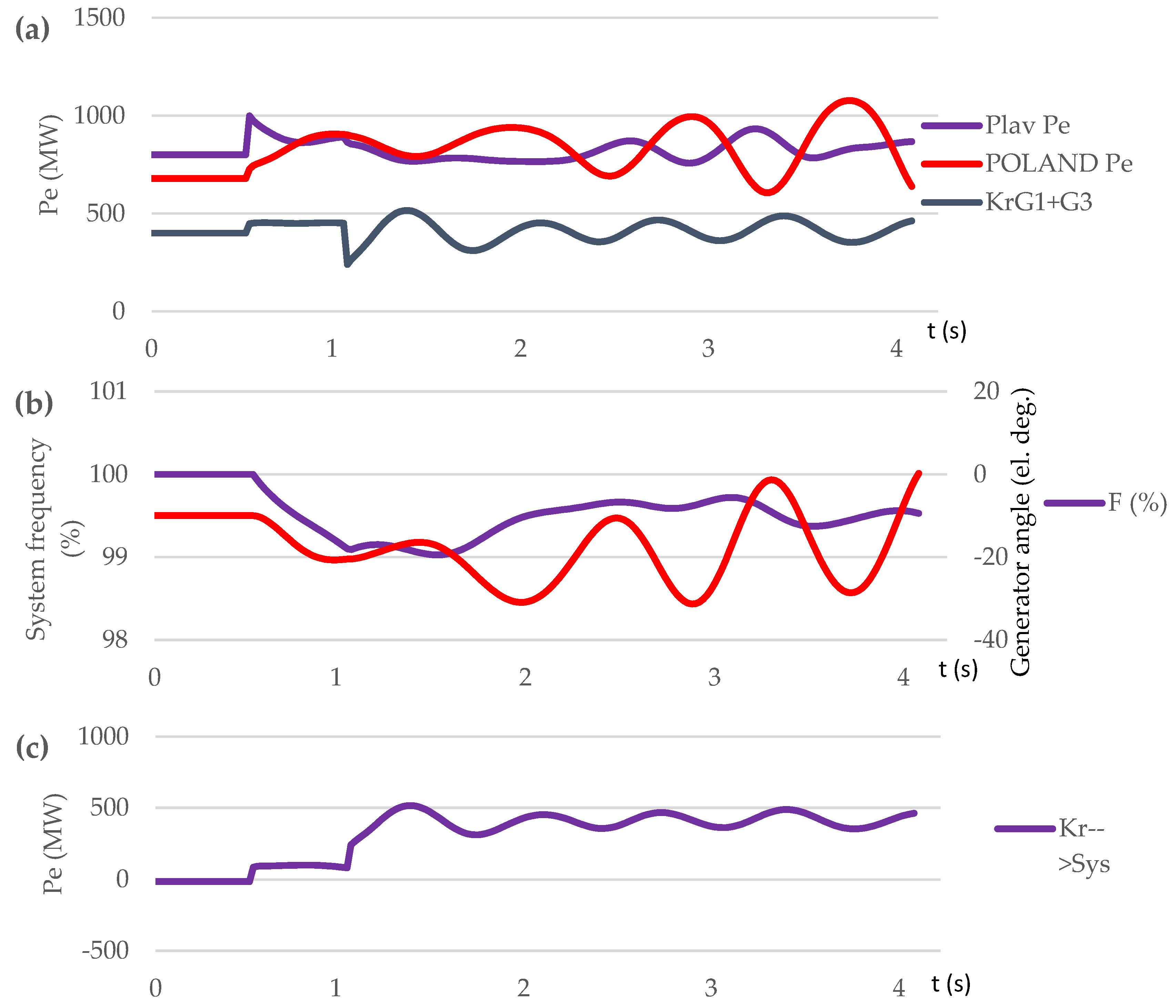

3.3.1. Test Case Set: Loss of Generation (Scenario S1, S2, S3)

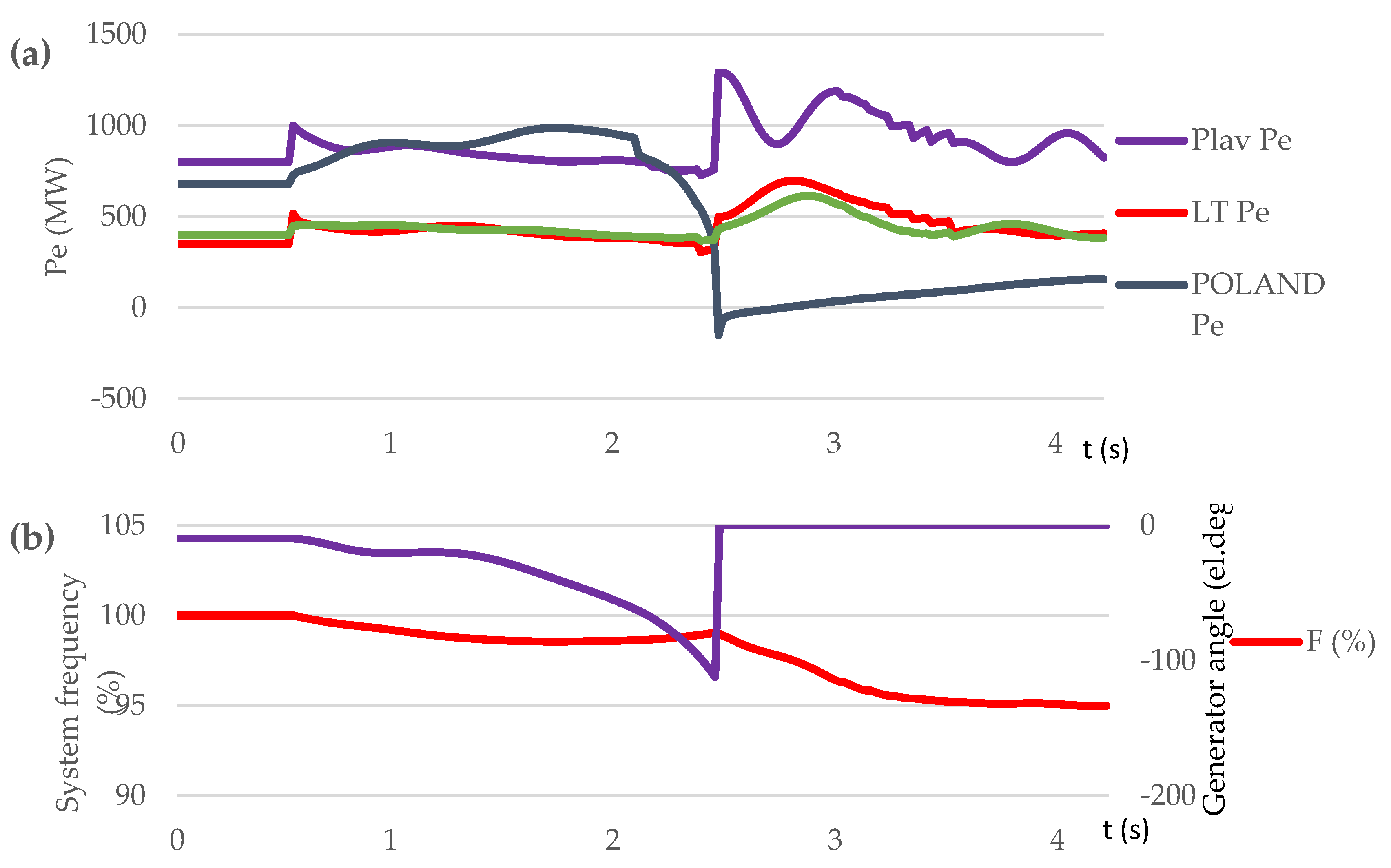

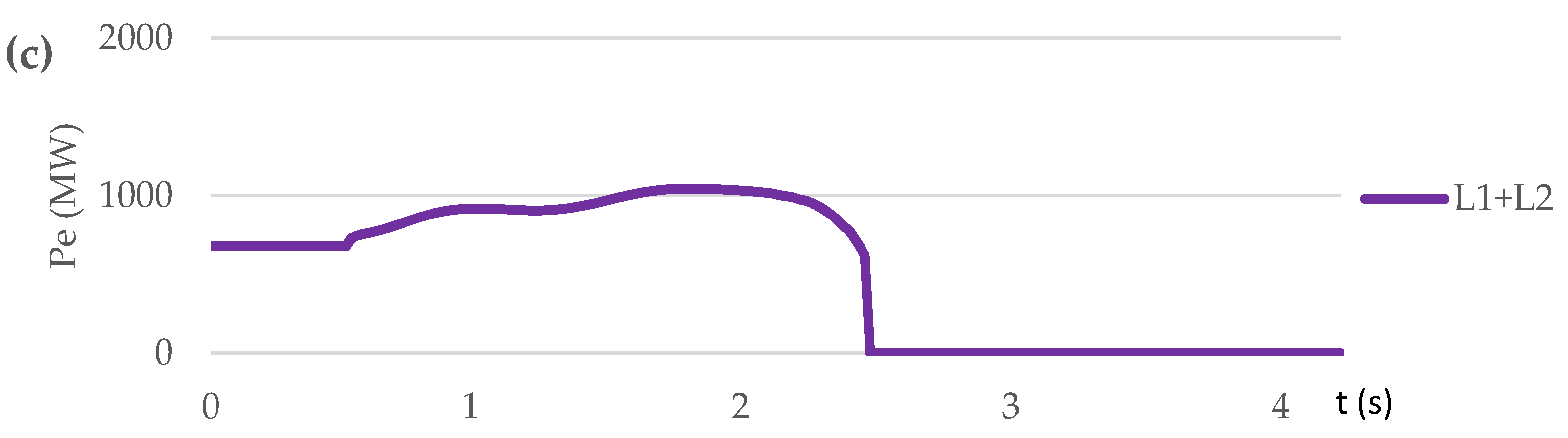

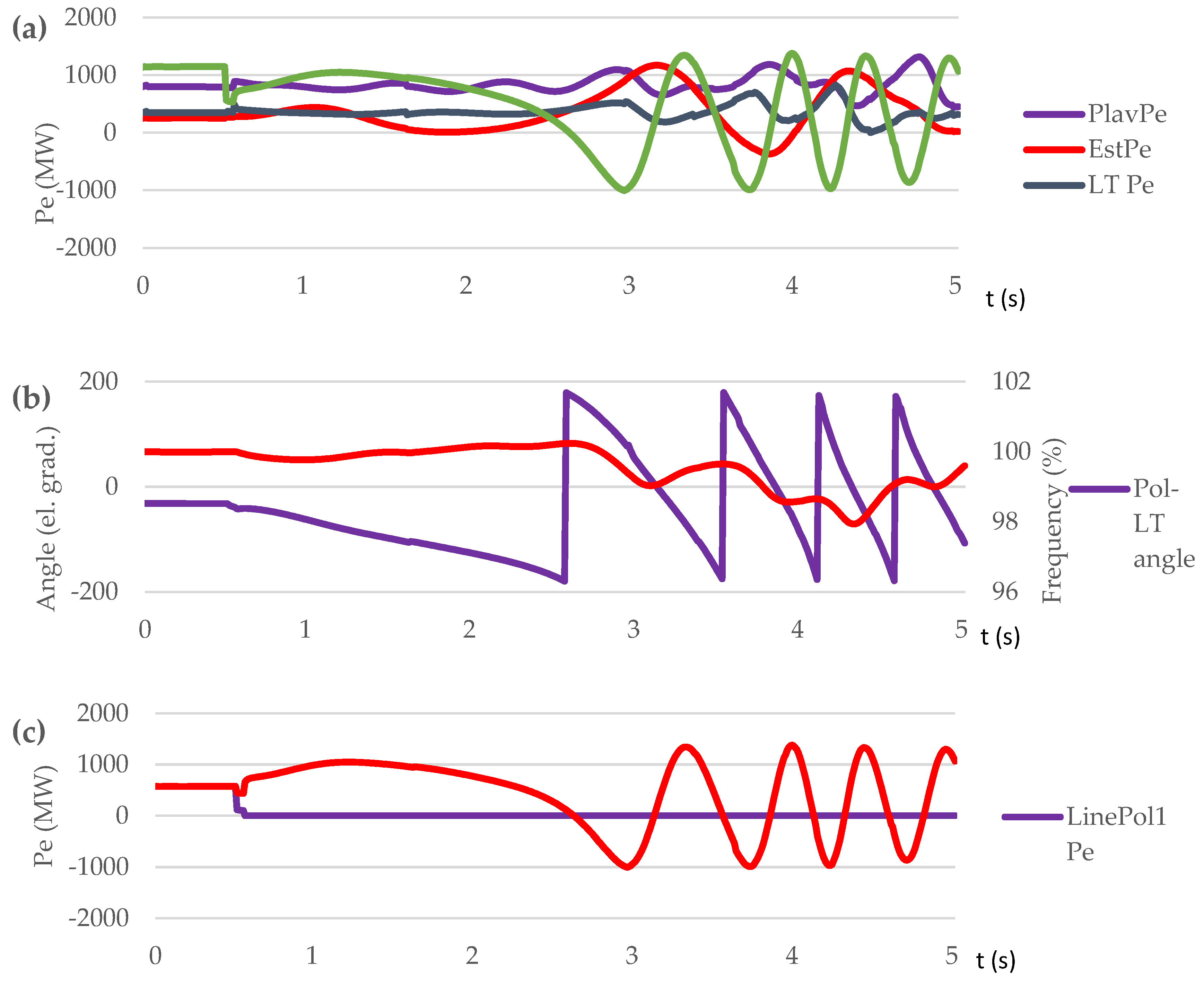

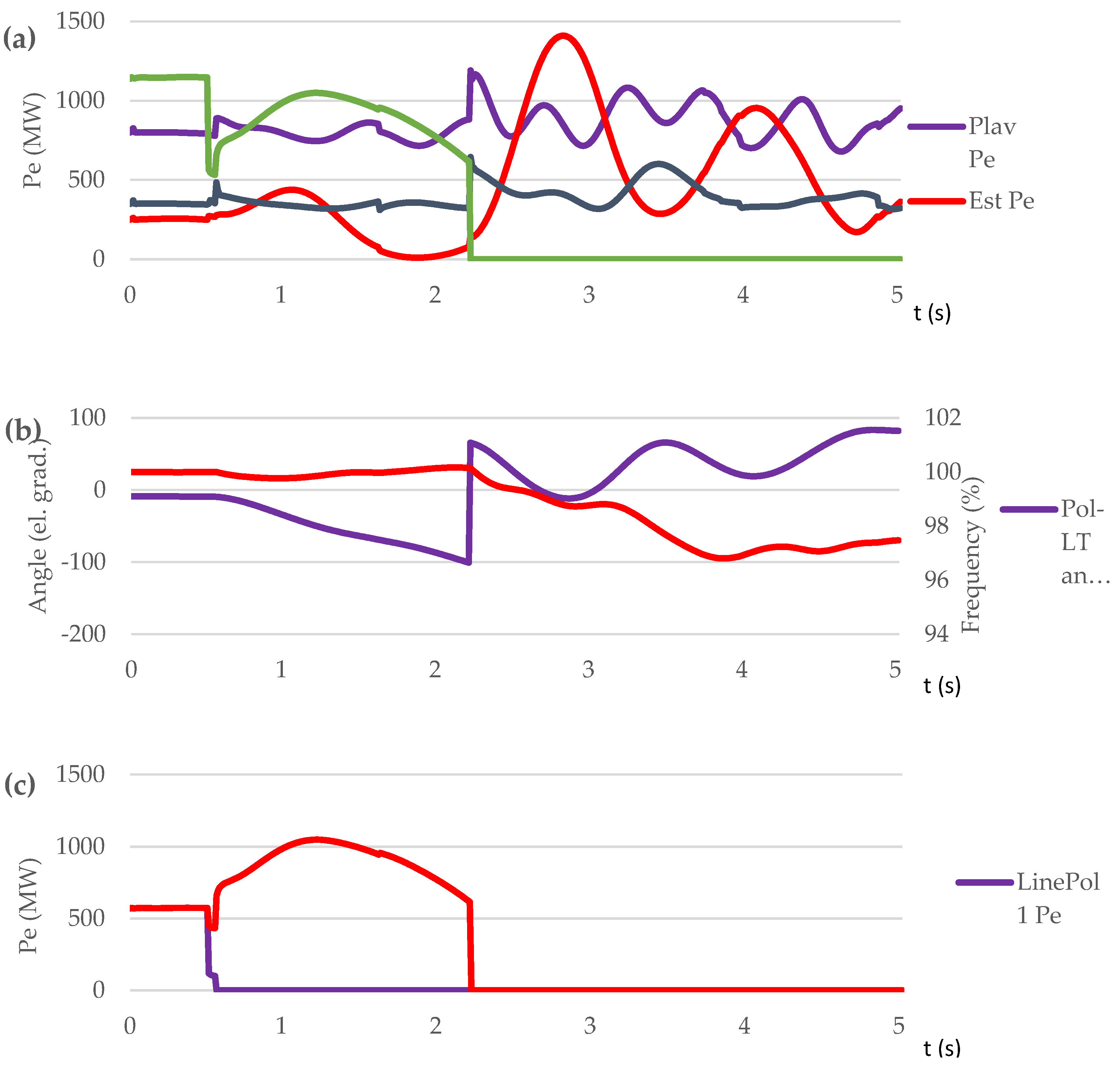

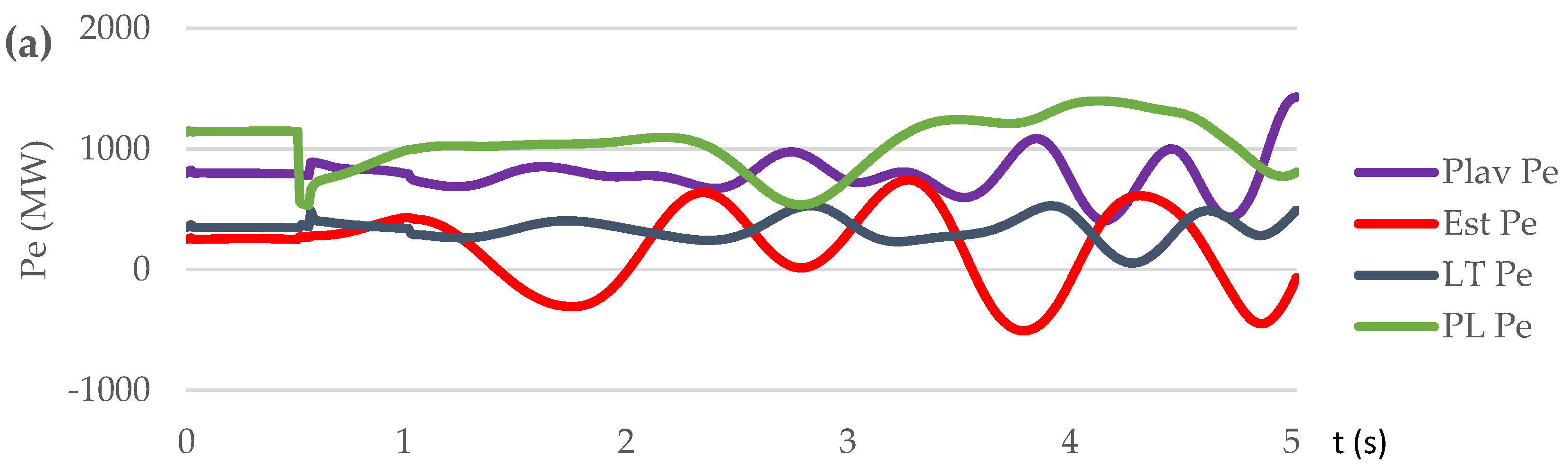

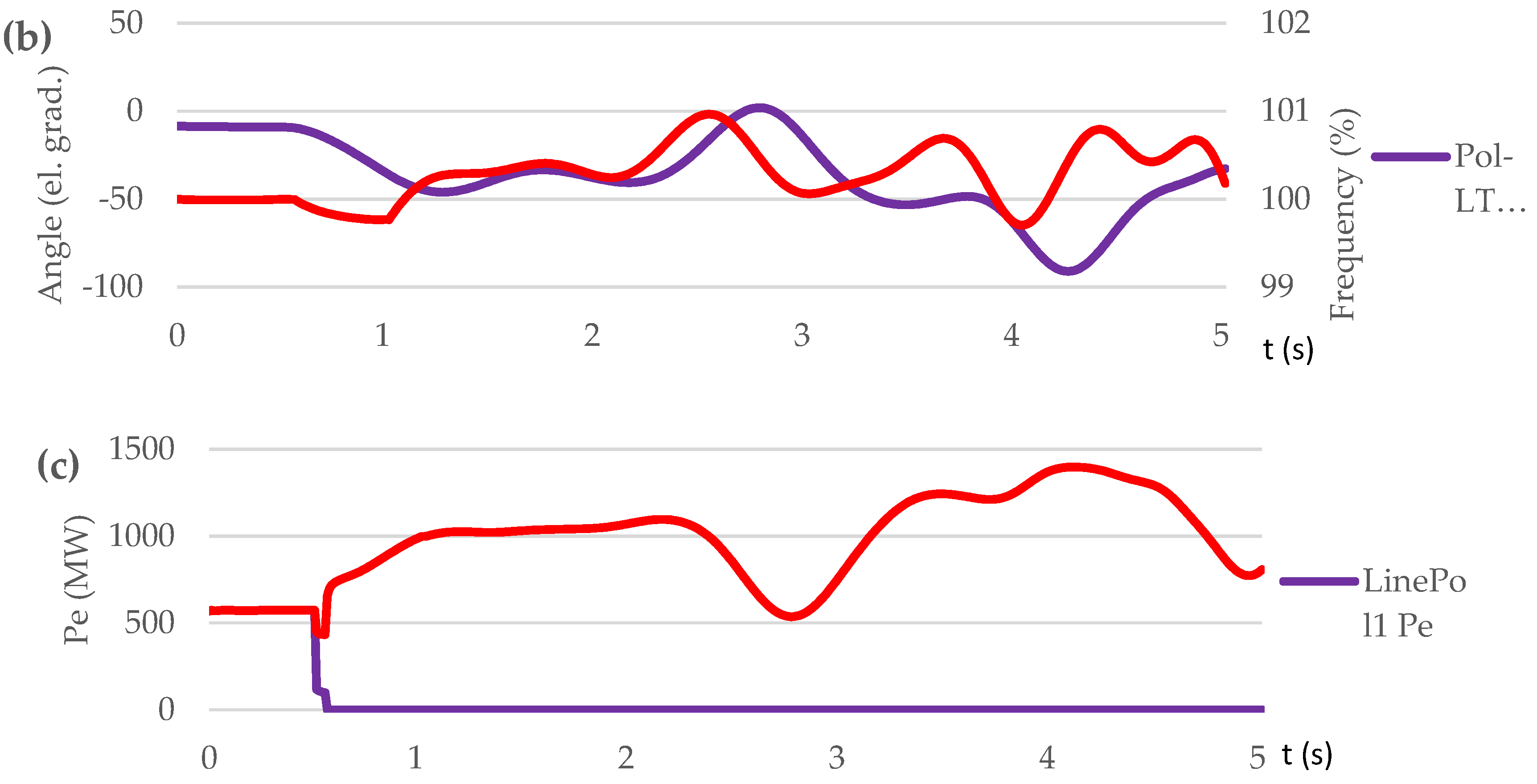

3.3.2. Test Case Set: Short Circuit on Transmission Line (Scenario S4, S5, S6)

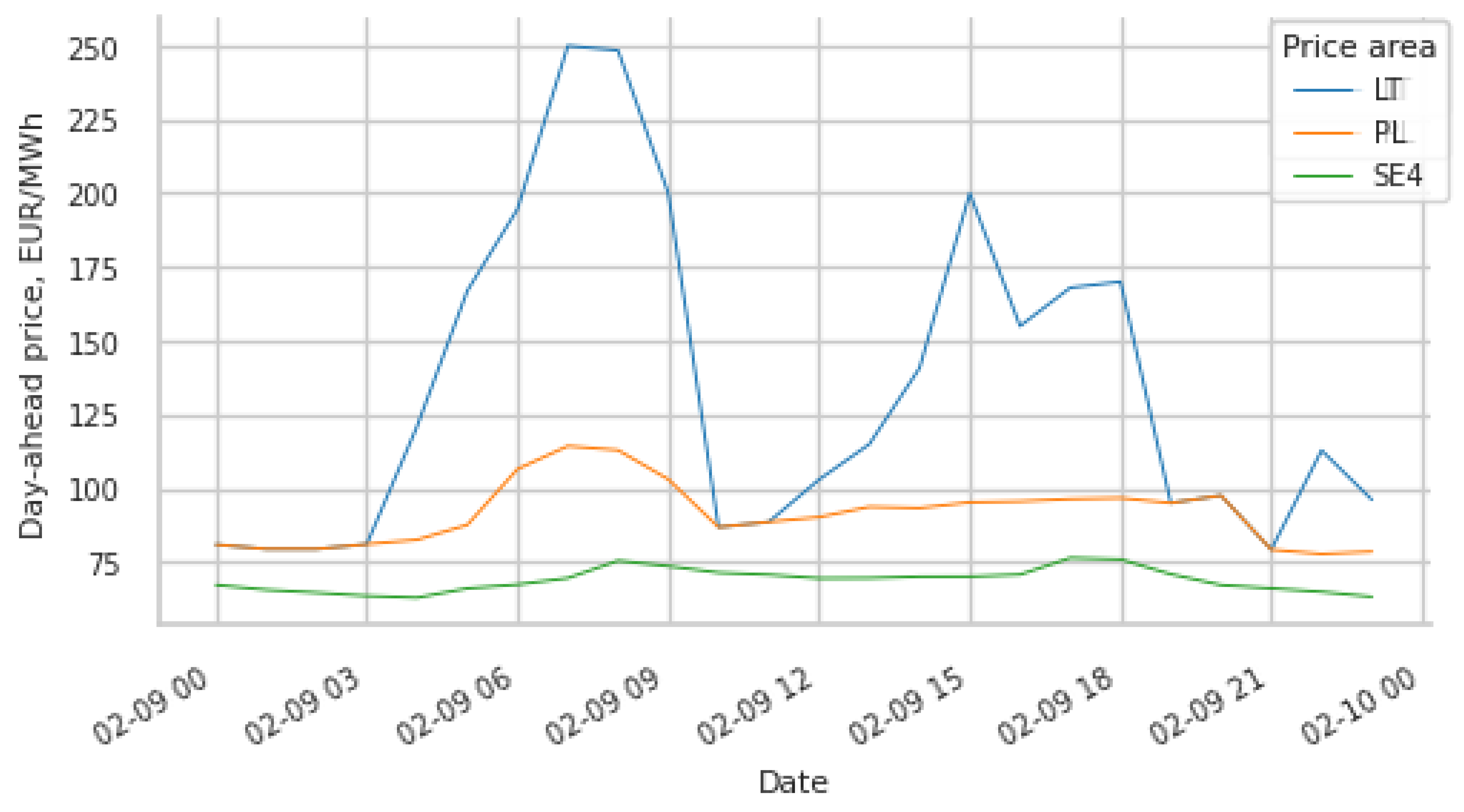

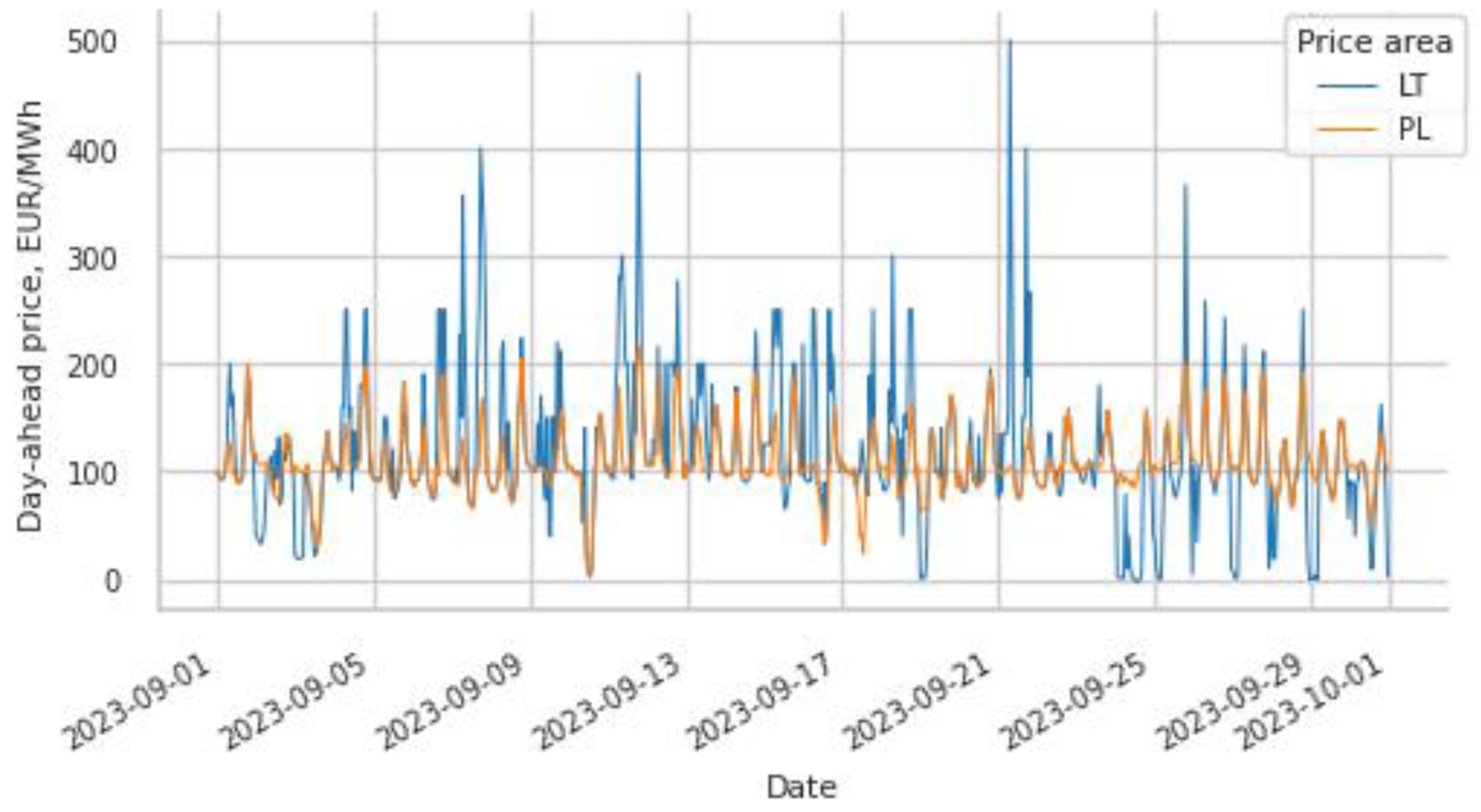

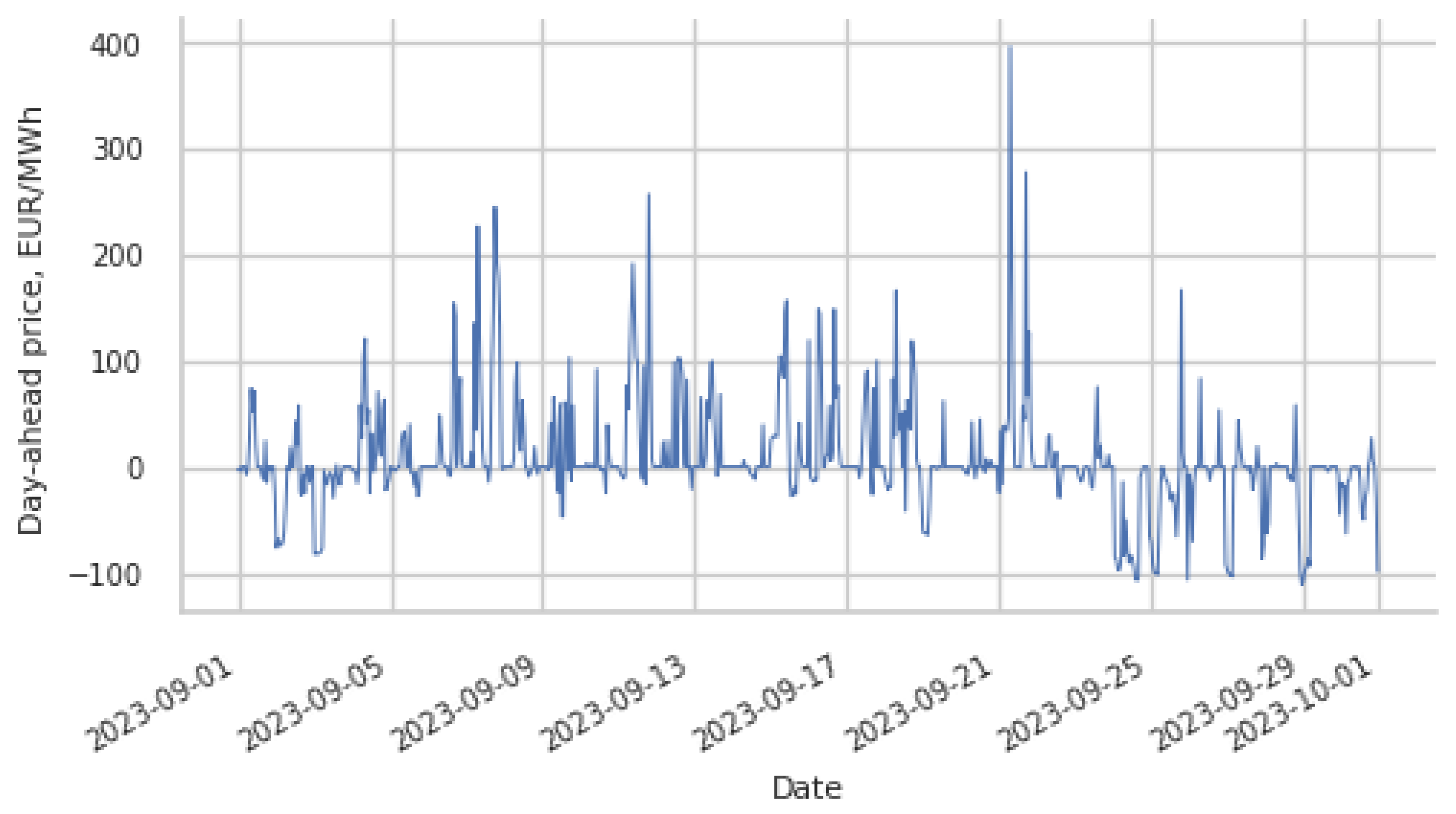

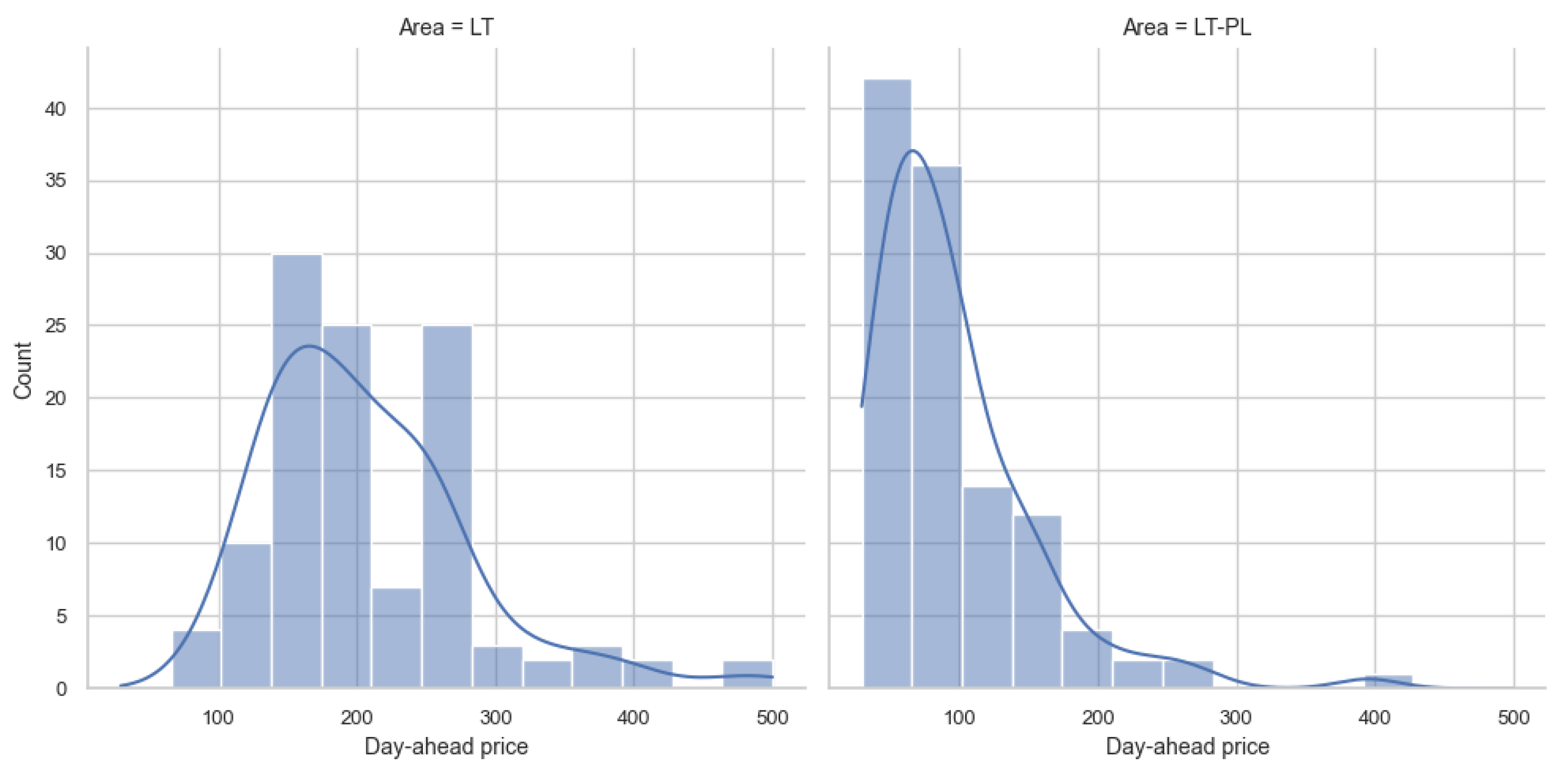

3.4. The Impact of the Line Capacity on the Market Price

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The European Council The 2030 Climate and Energy Framework. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/climate-change/2030-climate-and-energy-framework (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Milano, F.; Dorfler, F.; Hug, G.; Hill, D.J.; Verbic, G. Foundations and Challenges of Low-Inertia Systems (Invited Paper). In Proceedings of the 2018 Power Systems Computation Conference (PSCC); IEEE, June 2018; pp. 1–25.

- L., L.; Swarup, K.S. Inertia Monitoring in Power Systems: Critical Features, Challenges, and Framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 190, 114076. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.C.; Rhodes, J.D.; Webber, M.E. Understanding the Impact of Non-Synchronous Wind and Solar Generation on Grid Stability and Identifying Mitigation Pathways. Appl. Energy 2020, 262, 114492. [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, K.; Jain, S.K.; Padhy, P.K. Inertia Estimation in Modern Power System: A Comprehensive Review. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 211, 108–222. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency Available online: https://www.iea.org/.

- Alhelou, H.H.; Hamedani-Golshan, M.E.; Njenda, T.C.; Siano, P. A Survey on Power System Blackout and Cascading Events: Research Motivations and Challenges. Energies 2019, 12, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Zalostiba, D. Power System Blackout Prevention by Dangerous Overload Elimination and Fast Self-Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES ISGT Europe 2013; IEEE, October 2013; pp. 1–5.

- Ørum, E.; Kuivaniemi, M.; Laasonen, M.; Bruseth, A.I.; Jansson, E.A.; Danell, A.; Elkington, K.; Modig, N. ENTSO Report - Future System Inertia; 2015.

- Hatziargyriou, N.; Milanovic, J.; Rahmann, C.; Ajjarapu, V.; Canizares, C.; Erlich, I.; Hill, D.; Hiskens, I.; Kamwa, I.; Pal, B.; et al. Definition and Classification of Power System Stability - Revisited & Extended. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3271–3281. [CrossRef]

- Guzs, D.; Utans, A.; Sauhats, A.; Junghans, G.; Silinevics, J. Resilience of the Baltic Power System When Operating in Island Mode. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 61th International Scientific Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering of Riga Technical University (RTUCON); IEEE, November 5 2020; pp. 1–6.

- Markovic, U.; Stanojev, O.; Aristidou, P.; Vrettos, E.; Callaway, D.; Hug, G. Understanding Small-Signal Stability of Low-Inertia Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3997–4017. [CrossRef]

- Scherer, M.; Andersson, G. How Future-Proof Is the Continental European Frequency Control Structure? 2015 IEEE Eindhoven PowerTech, PowerTech 2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zbunjak, Z.; Bašić, H.; Pandžić, H.; Kuzle, I. Phase Shifting Autotransformer, Transmission Switching and Battery Energy Storage Systems to Ensure n-1 Criterion of Stability. J. Energy - Energ. 2015, 64, 285–298. [CrossRef]

- Machowski, J.; Bialek, J.W.; Bumby, J.R. Power System Dynamics. Stability and Control; 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2012; ISBN 978-0-470-72558-0.

- Sauhats, A.; Chuvychin, V.; Bockarjova, G.; Zalostiba, D.; Antonovs, D.; Petrichenko, R. Detection and Management of Large Scale Disturbances in Power System. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); 2016; Vol. 8985, pp. 147–152 ISBN 9783319316635.

- Ratnam, K.S.; Palanisamy, K.; Yang, G. Future Low-Inertia Power Systems: Requirements, Issues, and Solutions - A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 124, 109773. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Yang, G.; Nielsen, A.H.; Jensen, P.H. Combination of Synchronous Condenser and Synthetic Inertia for Frequency Stability Enhancement in Low-Inertia Systems. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2019, 10, 997–1005. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Murata, T.; Tamura, J. Effect of Coordination of Optimal Reclosing and Fuzzy Controlled Braking Resistor on Transient Stability during Unsuccessful Reclosing. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2006, 21, 1321–1330. [CrossRef]

- Sauhats, A.; Utans, A.; Silinevics, J.; Junghans, G.; Guzs, D. Enhancing Power System Frequency with a Novel Load Shedding Method Including Monitoring of Synchronous Condensers’ Power Injections. Energies 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.T.; Choi, H.; Trudnowski, D.J.; Nguyen, T. Real Power Modulation Strategies for Transient Stability Control. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 37215–37245. [CrossRef]

- Saluja, R.; Ali, M.H. Novel Braking Resistor Models for Transient Stability Enhancement in Power Grid System. 2013 IEEE PES Innov. Smart Grid Technol. Conf. ISGT 2013 2013, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- L; 23. Power Systems Engineering Research Center System Protection Schemes : Limitations , Risks , and Management; 2010.

- Tower, N. Special Protection Systems ( SPS ) and Remedial Action Schemes ( RAS ): Assessment of Definition , Regional Practices , and Application of Related Standards. 2013, 1–48.

- Beevers, D.; Branchini, L.; Orlandini, V.; De Pascale, A.; Perez-Blanco, H. Pumped Hydro Storage Plants with Improved Operational Flexibility Using Constant Speed Francis Runners. Appl. Energy 2015, 137, 629–637. [CrossRef]

- Koritarov, V.; Ploussard, Q.; Kwon, J.; Balducci, P. A Review of Technology Innovations for Pumped Storage Hydropower. 2022.

- Mahmoudi, M.M.; Kincic, S.; Zhang, H.; Tomsovic, K. Implementation and Testing of Remedial Action Schemes for Real-Time Transient Stability Studies. IEEE Power Energy Soc. Gen. Meet. 2018, 2018-Janua, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Ojetola, S.; Wold, J.; Trudnowski, D.; Wilches-Bernal, F.; Elliott, R. A Real Power Injection Control Strategy for Improving Transient Stability. IEEE Power Energy Soc. Gen. Meet. 2020, 2020-Augus. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Longatt, F.; Adiyabazar, C.; Martinez, E.V. Setting and Testing of the Out-of-Step Protection at Mongolian Transmission System. Energies 2021, 14, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Ojetola, S.; Wold, J.; Trudnowski, D. Multi-Loop Transient Stability Control via Power Modulation from Energy Storage Devices. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 5153–5163. [CrossRef]

- Sauhats, A.S.; Utans, A. Out-of-Step Relaying Principles and Advances. Scientific Monograph; RTU Press, 2022.

- Rudez, U.; Mihalic, R. Trends in WAMS-Based under-Frequency Load Shedding Protection. In Proceedings of the IEEE EUROCON 2017 -17th International Conference on Smart Technologies; IEEE, July 2017; pp. 782–787.

- What Is Green Hydrogen and Why Do We Need It? An Expert Explains Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/12/what-is-green-hydrogen-expert-explains-benefits/.

- Nikolaidis, P.; Poullikkas, A. A Comparative Review of Electrical Energy Storage Systems for Better Sustainability. J. Power Technol. 2017, 97, 220–245.

- Šćekić, L.; Mujović, S.; Radulović, V. Pumped Hydroelectric Energy Storage as a Facilitator of Renewable Energy in Liberalized Electricity Market. Energies 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Koltermann, L.; Drenker, K.K.; Celi Cortés, M.E.; Jacqué, K.; Figgener, J.; Zurmühlen, S.; Sauer, D.U. Potential Analysis of Current Battery Storage Systems for Providing Fast Grid Services like Synthetic Inertia – Case Study on a 6 MW System. J. Energy Storage 2023, 57, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Angenendt, G.; Zurmühlen, S.; Figgener, J.; Kairies, K.P.; Sauer, D.U. Providing Frequency Control Reserve with Photovoltaic Battery Energy Storage Systems and Power-to-Heat Coupling. Energy 2020, 194, 116923. [CrossRef]

- Ojetola, S.T.; Wold, J.; Trudnowski, D. Feedback Control Strategy for Transient Stability Application. Energies 2022, 15, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Ebadian, M.; Alizadeh, M. Improvement of Power System Transient Stability Using Fault Current Limiter and Thyristor Controlled Braking Resistor. 2009 Int. Conf. Electr. Power Energy Convers. Syst. EPECS 2009 2009, 1–6.

- Guzmán, A.; Tziouvaras, D.A.; Schweitzer, E.O.; Martin, K. Local- and Wide-Area Network Protection Systems Improve Power System Reliability. Power Syst. Conf. 2006 Adv. Metering, Prot. Control. Commun. Distrib. Resour. PSC 2006, 174–181. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Preece, R.; Panteli, M. Risk Assessment of Cascading Failures in Power Systems with Increasing Wind Penetration. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 211. [CrossRef]

- ENTSO-E ENTSO-E Guideline for Cost Benefit Analysis of Grid Development Projects. Final - Approved by the European Commission. 27. September 2018. Entso-E 2018, 71.

- Nord Pool Available online: https://www.nordpoolgroup.com.

- Hess, D.; Wetzel, M.; Cao, K.K. Representing Node-Internal Transmission and Distribution Grids in Energy System Models. Renew. Energy 2018, 119, 874–890. [CrossRef]

- Kimbark, E.W. Power System Stability, Volume I; IEEE Press Classic Reissue, 1995; ISBN 978-0-780-31135-0.

- Hong, Y.Y.; Hsiao, C.Y. Event-based Under-frequency Load Shedding Scheme in a Standalone Power System. Energies 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Stanković, S.; Hillberg, E.; Ackeby, S. System Integrity Protection Schemes: Naming Conventions and the Need for Standardization. Energies 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Antonovs, D.; Sauhats, A.; Utans, A.; Svalovs, A.; Bochkarjova, G. Protection Scheme against Out-of-Step Condition Based on Synchronized Measurements. Proc. - 2014 Power Syst. Comput. Conf. PSCC 2014 2014, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Sauhats, A.; Svalova, I.; Svalovs, A.; Antonovs, D.; Utans, A.; Bochkarjova, G. Two-Terminal out-of-Step Protection for Multi-Machine Grids Using Synchronised Measurements. 2015 IEEE Eindhoven PowerTech, PowerTech 2015 2015, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Sauhats, A.; Utans, A.; Biela-Dailidovicha, E. Wide-Area Measurements-Based out-of-Step Protection System. 2015 56th Int. Sci. Conf. Power Electr. Eng. Riga Tech. Univ. RTUCON 2015 2015, 5–9. [CrossRef]

- Sauhats, A.; Utans, A.; Antonovs, D.; Svalovs, A. Angle Control-Based Multi-Terminal out-of-Step Protection System. Energies 2017, 10. [CrossRef]

- Naval, N.; Yusta, J.M.; Sánchez, R.; Sebastián, F. Optimal Scheduling and Management of Pumped Hydro Storage Integrated with Grid-Connected Renewable Power Plants. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73. [CrossRef]

- Kougias, I.; Aggidis, G.; Avellan, F.; Deniz, S.; Lundin, U.; Moro, A.; Muntean, S.; Novara, D.; Pérez-Díaz, J.I.; Quaranta, E.; et al. Analysis of Emerging Technologies in the Hydropower Sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109257. [CrossRef]

- Carrieann Stocks Largest Pumped Storage Plants in Operation and Development Available online: https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/features/largest-pumped-storage-plants/.

- Harby, A.; Sauterleute, J.; Korpås, M.; Killingtveit, Å.; Solvang, E.; Nielsen, T. Pumped Storage Hydropower. In Transition to Renewable Energy Systems; Wiley Blackwell, 2013; pp. 597–618 ISBN 9783527673872.

- Chiodi, A.; Deane, J.P.; Gargiulo, M.; Ó’Gallachóir, B.P. Modelling Electricity Generation - Comparing Results: From a Power Systems Model and an Energy Systems Model. Environ. Res. Inst. 2011, 1–25.

- Ottesen, S.Ø.; Tomasgard, A.; Fleten, S.E. Multi Market Bidding Strategies for Demand Side Flexibility Aggregators in Electricity Markets. Energy 2018, 149. [CrossRef]

- Iria, J.; Soares, F.; Matos, M. Optimal Supply and Demand Bidding Strategy for an Aggregator of Small Prosumers. Appl. Energy 2018, 213, 658–669. [CrossRef]

- European Commission Energy Security: The Synchronisation of the Baltic States’ Electricity Networks - European Solidarity in Action Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_3337.

- AST Synchronisation with Europe Available online: https://www.ast.lv/en/projects/synchronisation-europe.

- Press Release: Estonia’s First Pumped Hydro Energy Storage Facility Has Issued an Invitation to Tender Available online: https://zeroterrain.com/press-release-estonias-first-pumped-hydro-energy-storage-facility-invitation-to-tender/.

- ignitis gamyba Kruonis Pumped Storage Hydroelectric Power Plant (KPSHP) Available online: https://ignitisgamyba.lt/en/our-activities/electricity-generation/kruonis-pumped-storage-hydroelectric-power-plant-kpshp/4188.

- etap software Etap Software. Available online: https://etap.com/ (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Cai, T.; Dong, M.; Chen, K.; Gong, T. Methods of Participating Power Spot Market Bidding and Settlement for Renewable Energy Systems. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 7764–7772. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Capacity | 900 MW |

| Reversible pump-turbine units | 4 units |

| Rated capacity in generation mode (per unit) Rated capacity in pumping mode (per unit) |

225 MWh/h 220 MWh/h |

| Efficiency in generation/ pumping mode | 90.0 / 80.0 % |

| Cycle efficient use rate | 0.74 |

| Upper reservoir area | 3.05 km2 |

| Maximum water head | 113.5 m |

| Minimum water head | 105.5 m |

| Total pool capacity | 48,000,000 m3 |

| Parameter |

Value (scenarios S1…S3 / S4…S6) |

| Total generation before disruption | 1550 / 1850 MW |

| Total import | 1400 / 1100 MW |

| Total export | 250 MW |

| Total inertia | 8.64 s |

| Contingency type | Scenario | Proposed control method implementation | OOS protection operation | The consequence of transient process / frequency nadir (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden-Lithuania off. 700 MW lost | S1 | NO | NO | Out-of-step condition. 5 steps UFLS triggered / 95.45 % |

| S2 | NO | YES | Out-of-step condition. OSP operation. 6 steps UFLS triggered. / 94.9 % | |

| S3 | YES | YES | No out-of-step condition. No UFLS triggered. / 99 % | |

| Short circuit on L1 at t=0,5 s | S4 | NO | NO | Out-of-step condition. No UFLS triggered. / 97.97 % |

| S5 | NO | YES | Out-of-step condition. OSP operation. 3 steps UFLS triggered. / 96.8 % | |

| S6 | YES | YES | No out-of-step condition. No UFLS triggered. / 99.7÷100.8 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).