Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

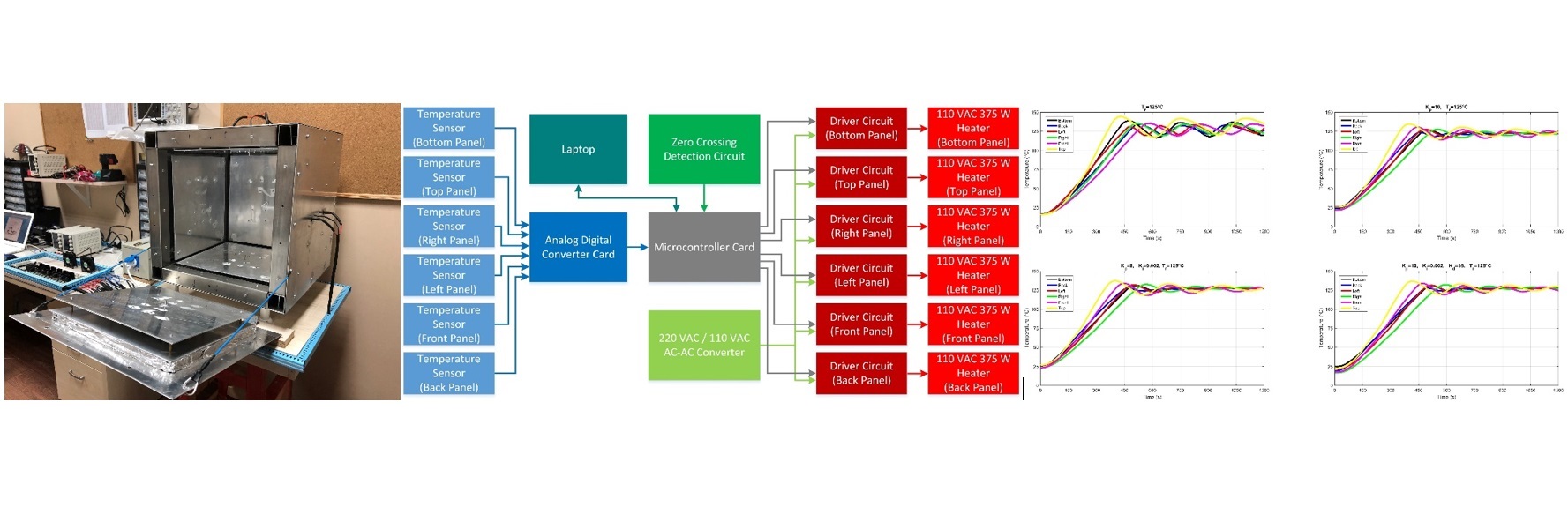

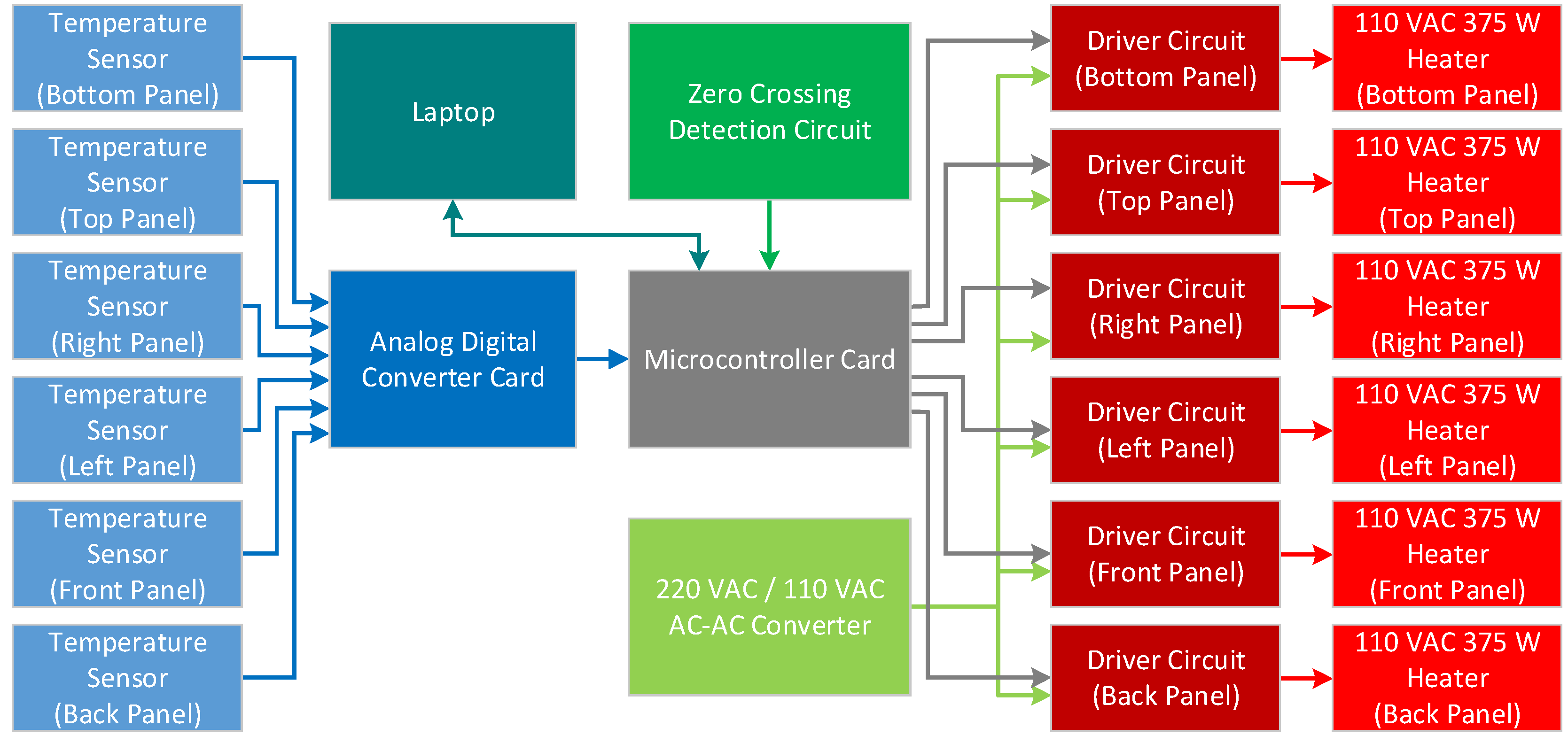

- An original oven with heaters and temperature sensors on six surfaces was designed, modeled, and temperature controlled.

- Temperature measurements were taken at six different points inside the oven, and each heater on the six surfaces of the oven was controlled separately.

- It was demonstrated that homogeneous heating is not possible in electric ovens unless there are heaters on all six surfaces and the temperature of each heater is controlled.

- The heaters were switched at zero crossings of the main voltage to prevent sudden current draws and noise generation on the mains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The On-Off Control

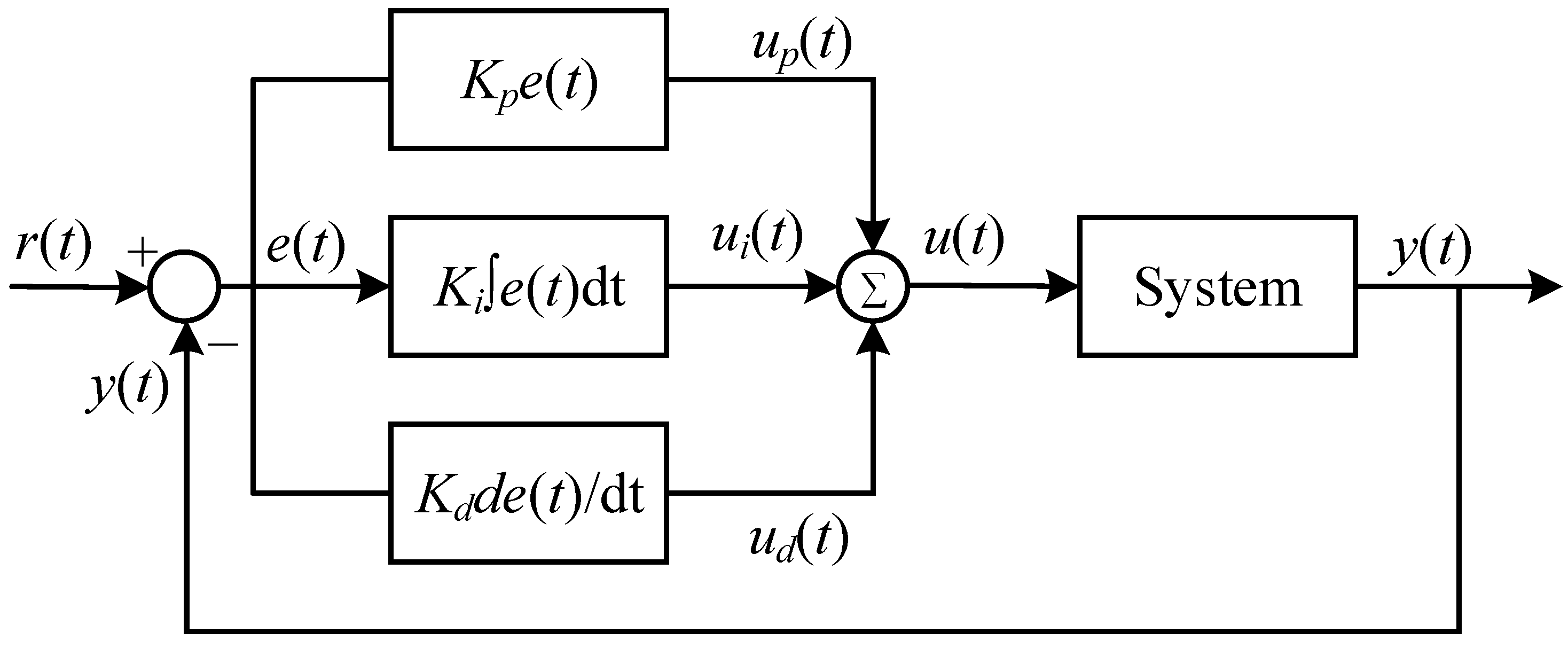

2.2. PID Control

2.3. Error Area Based Performance Criteria

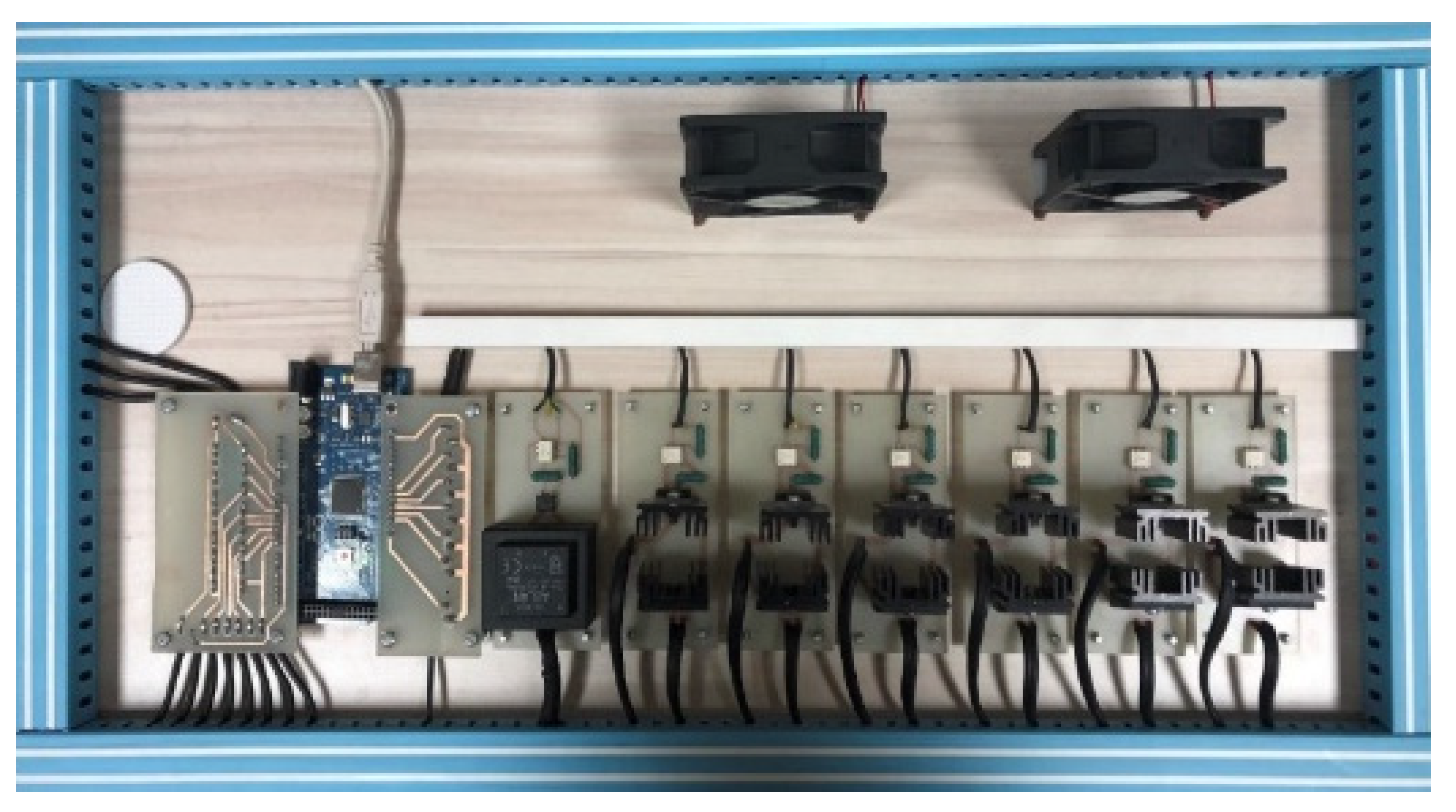

2.4. General Description of the System

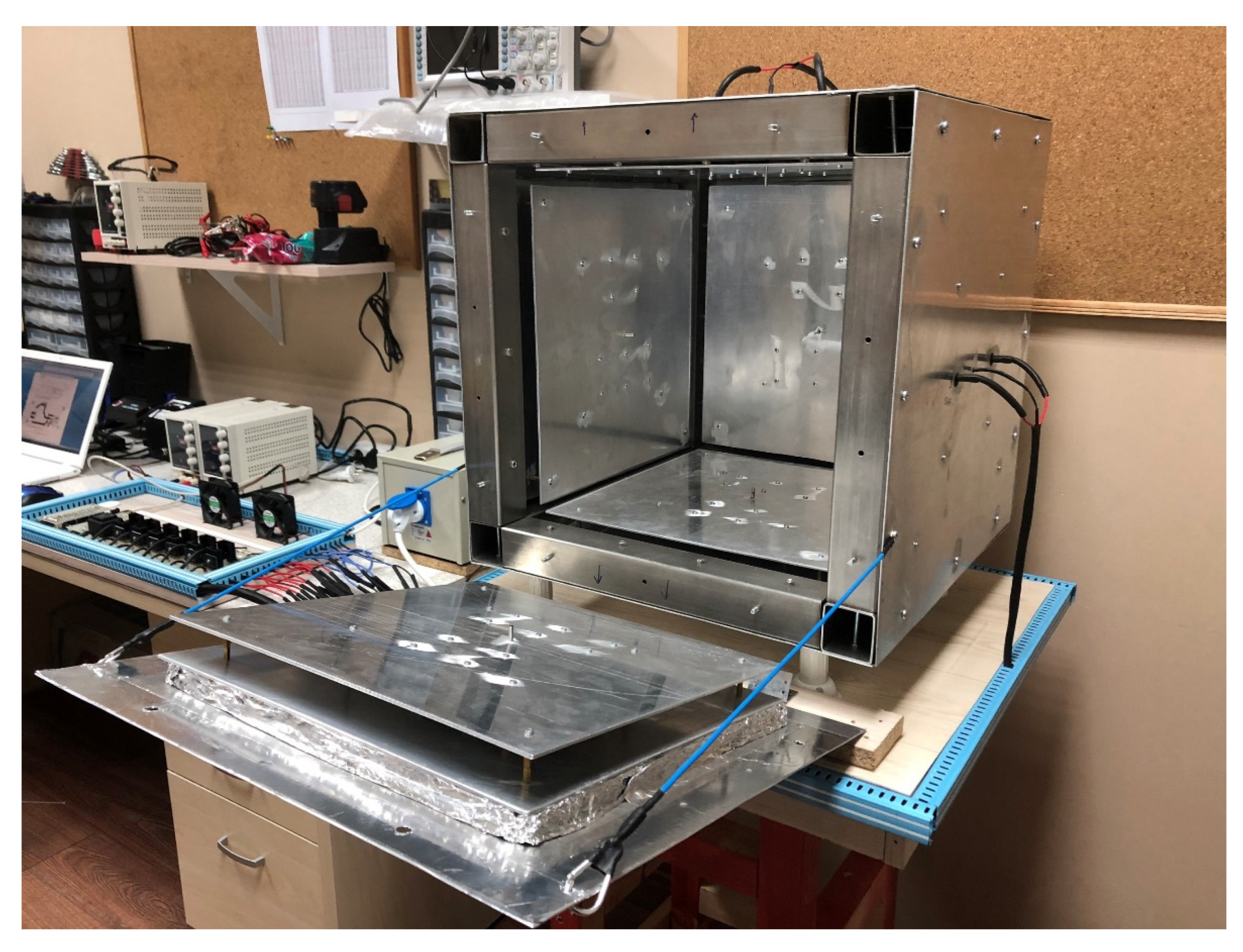

2.5. Mechanical Part

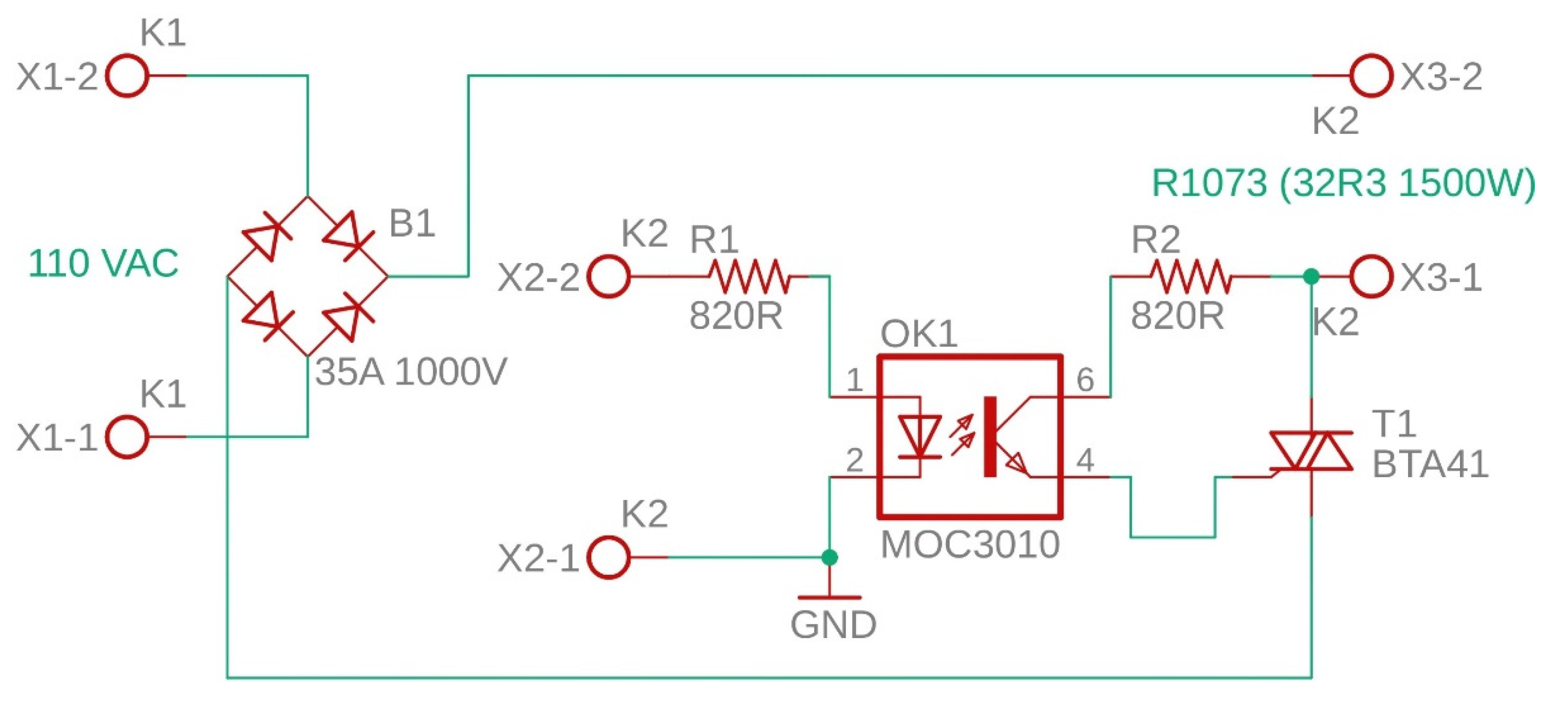

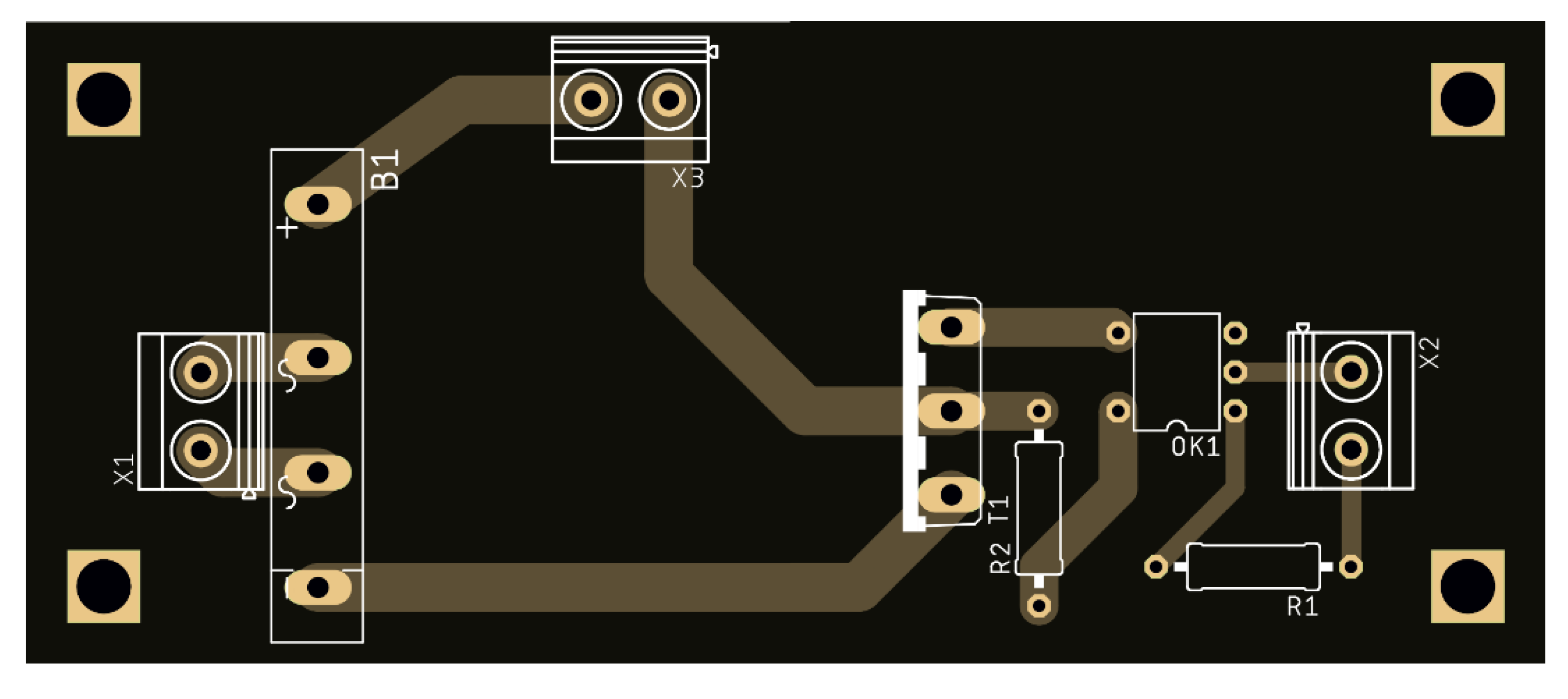

2.6. Electrical Part

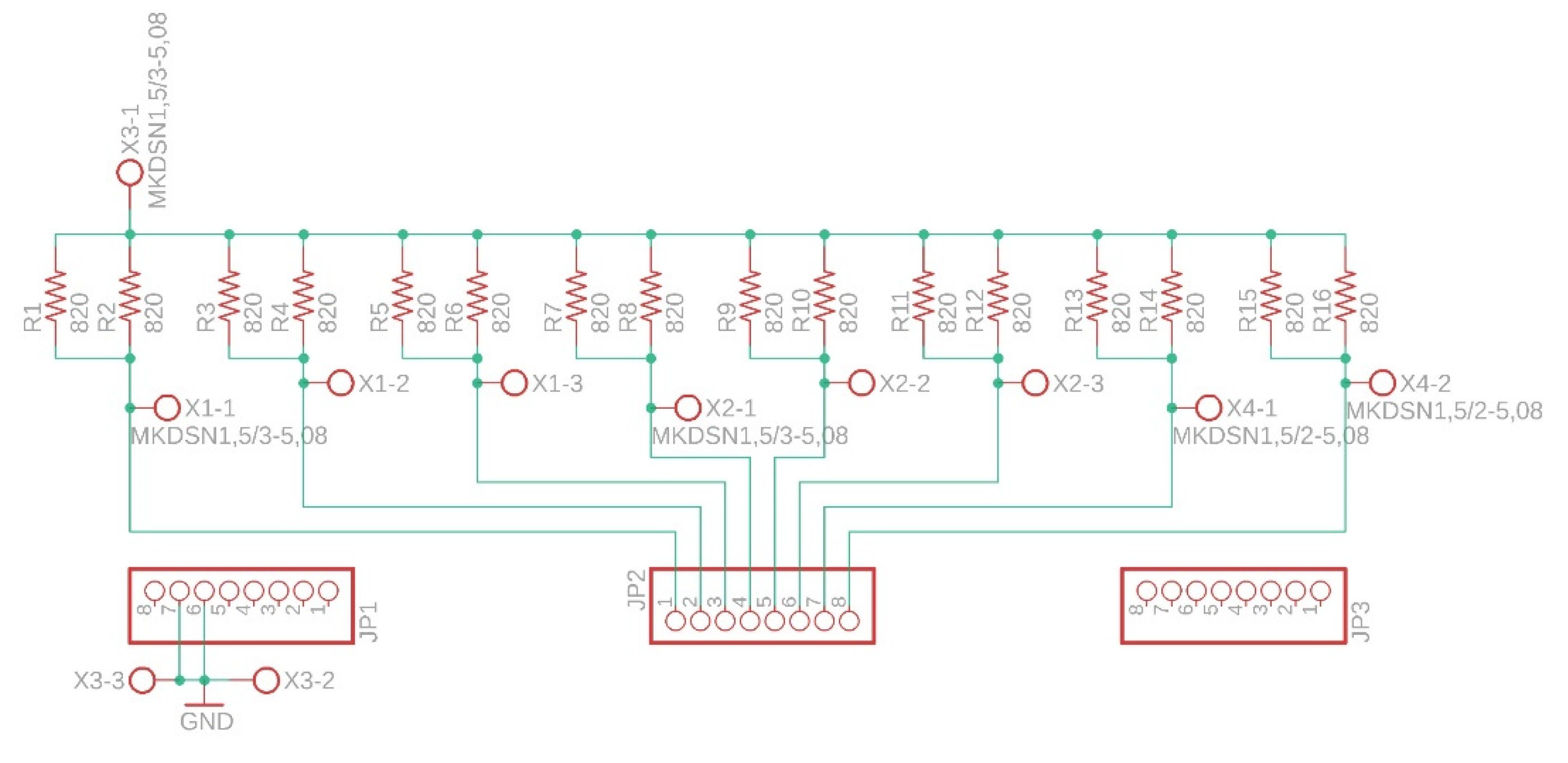

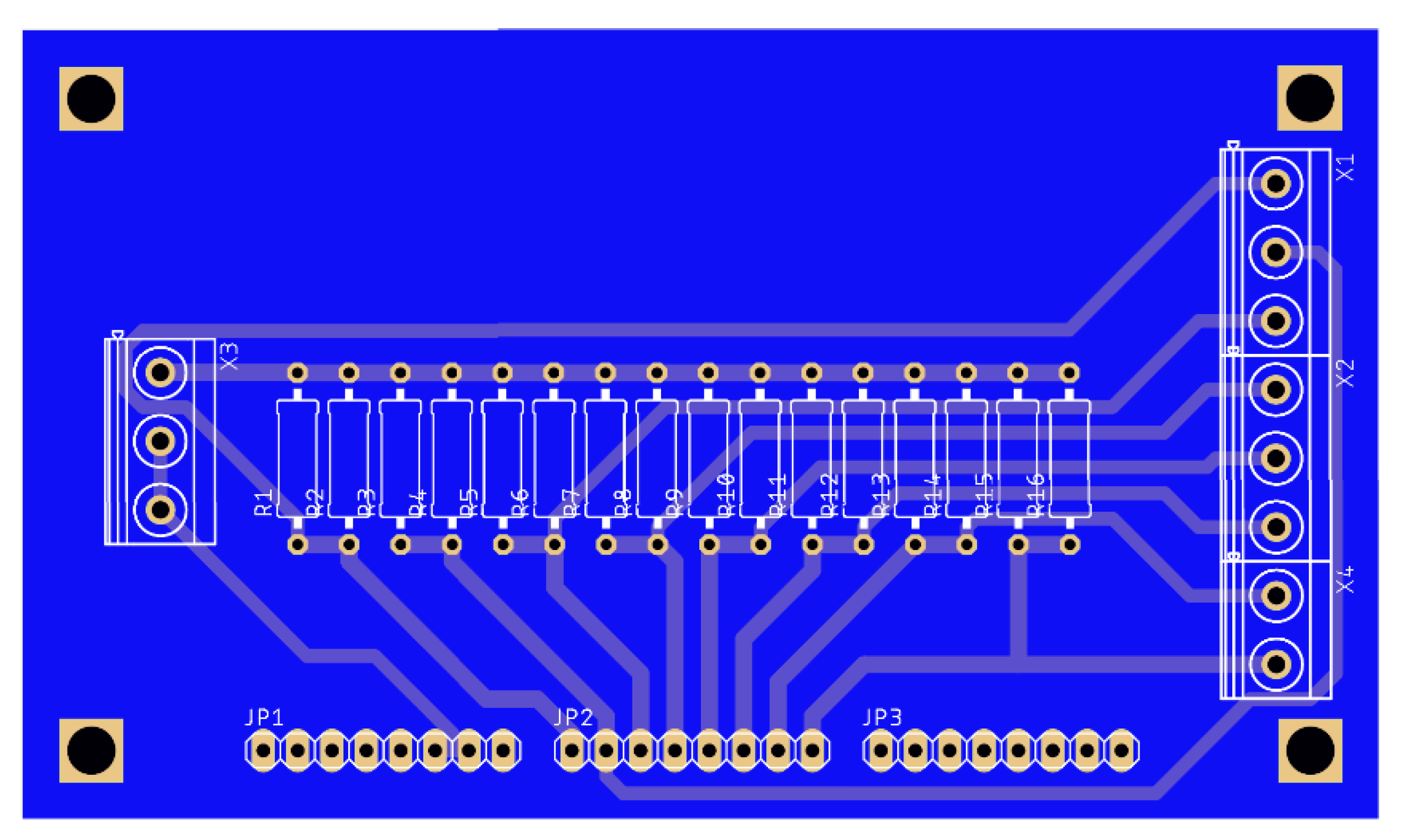

2.6.1. Analog Digital Converter Card

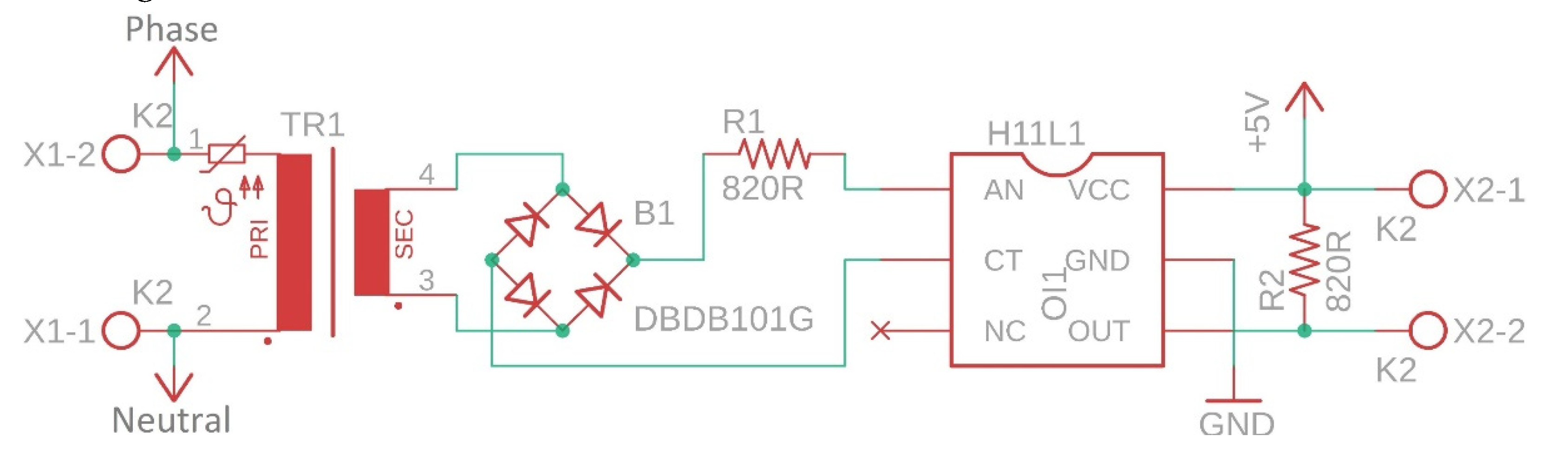

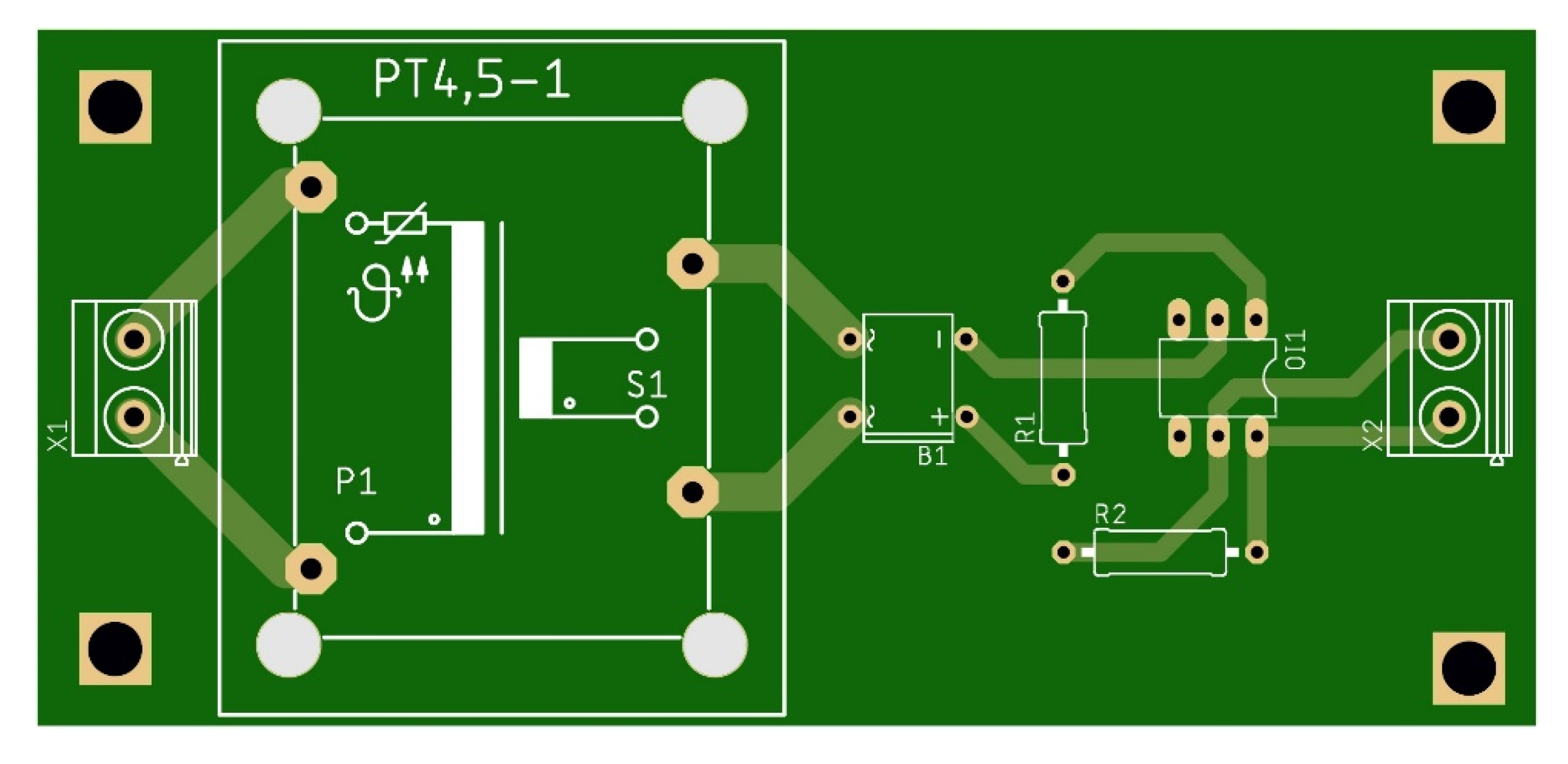

2.6.2. Zero-crossing detection circuit

2.7. Software Part

2.7.1. Control software:

2.7.2. Controller software:

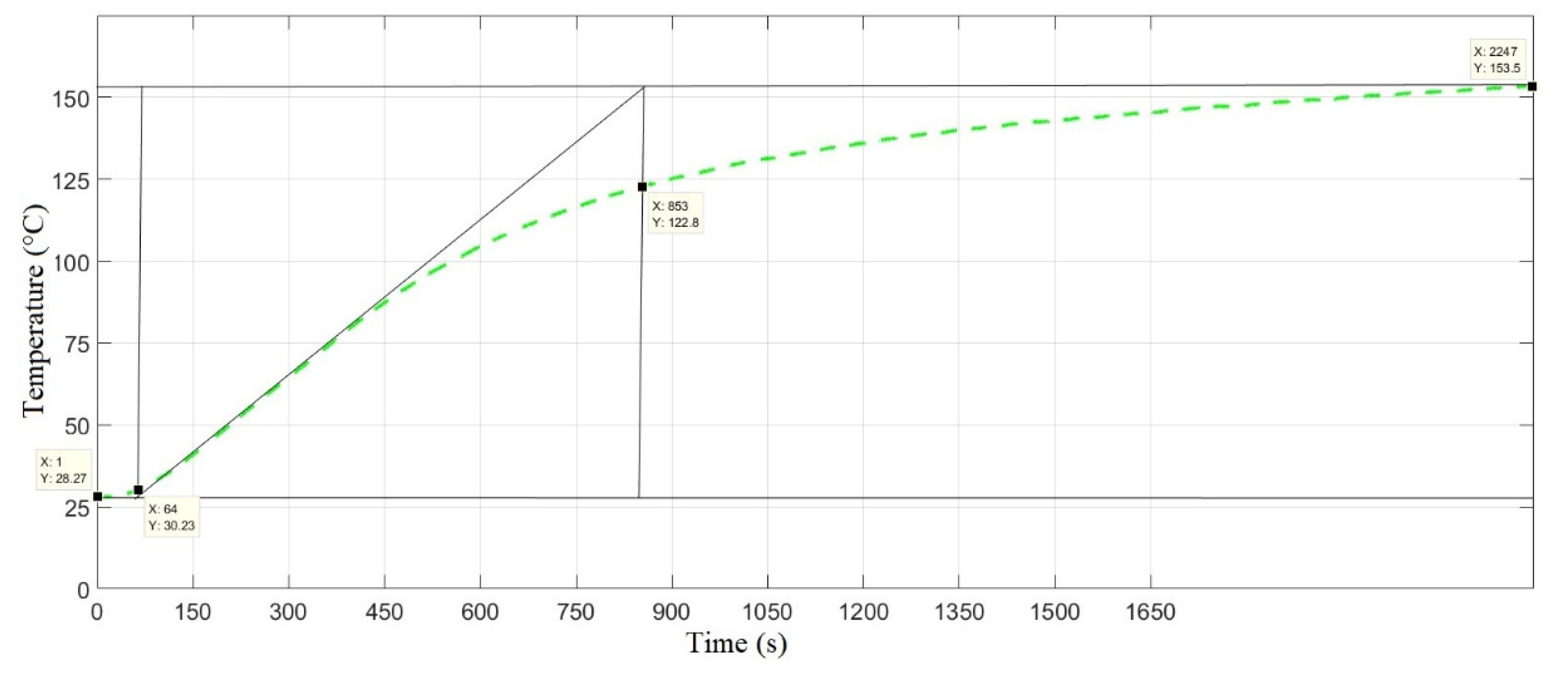

2.8. System Modeling and Determination of PID Parameters

3. Results

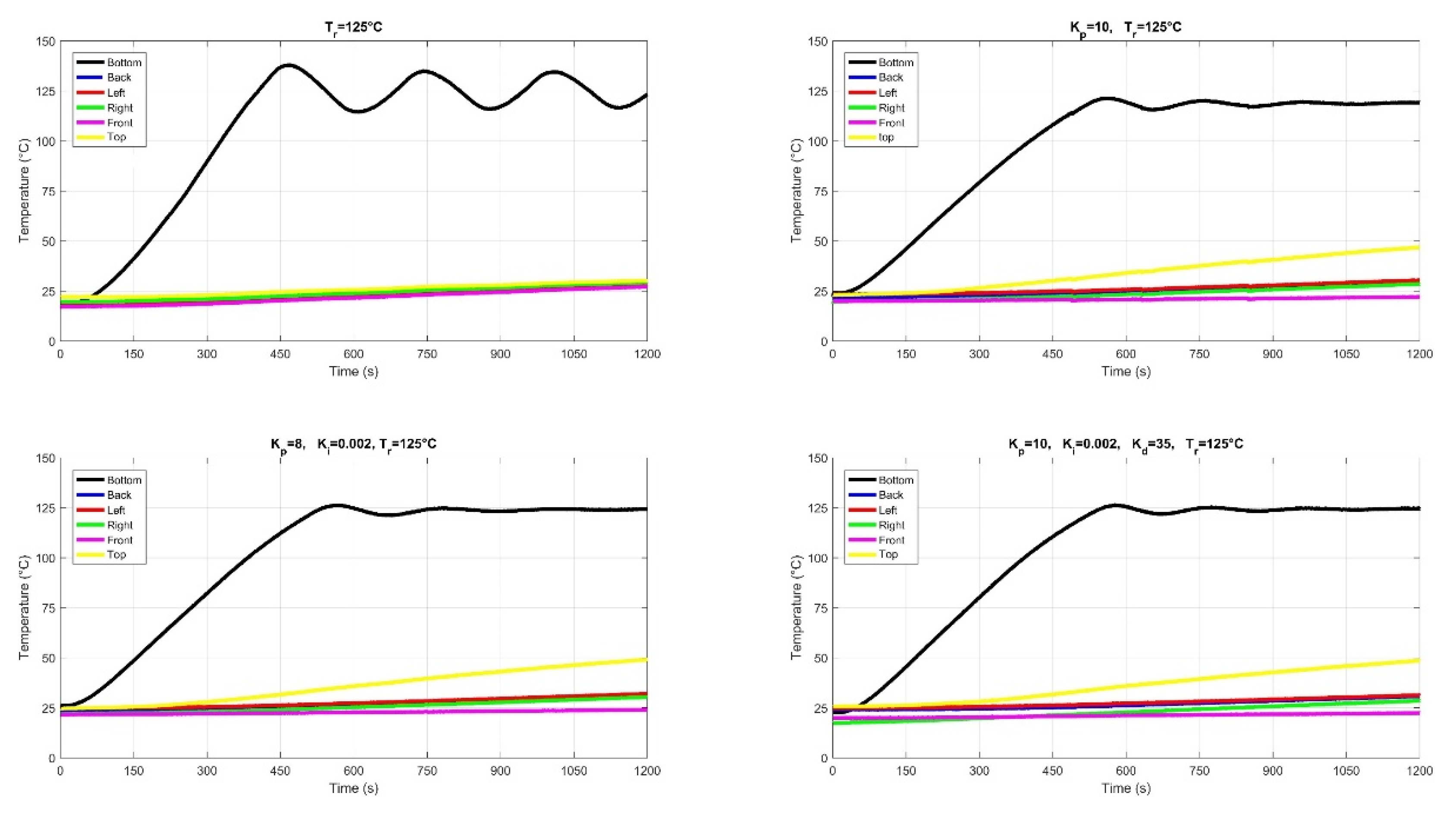

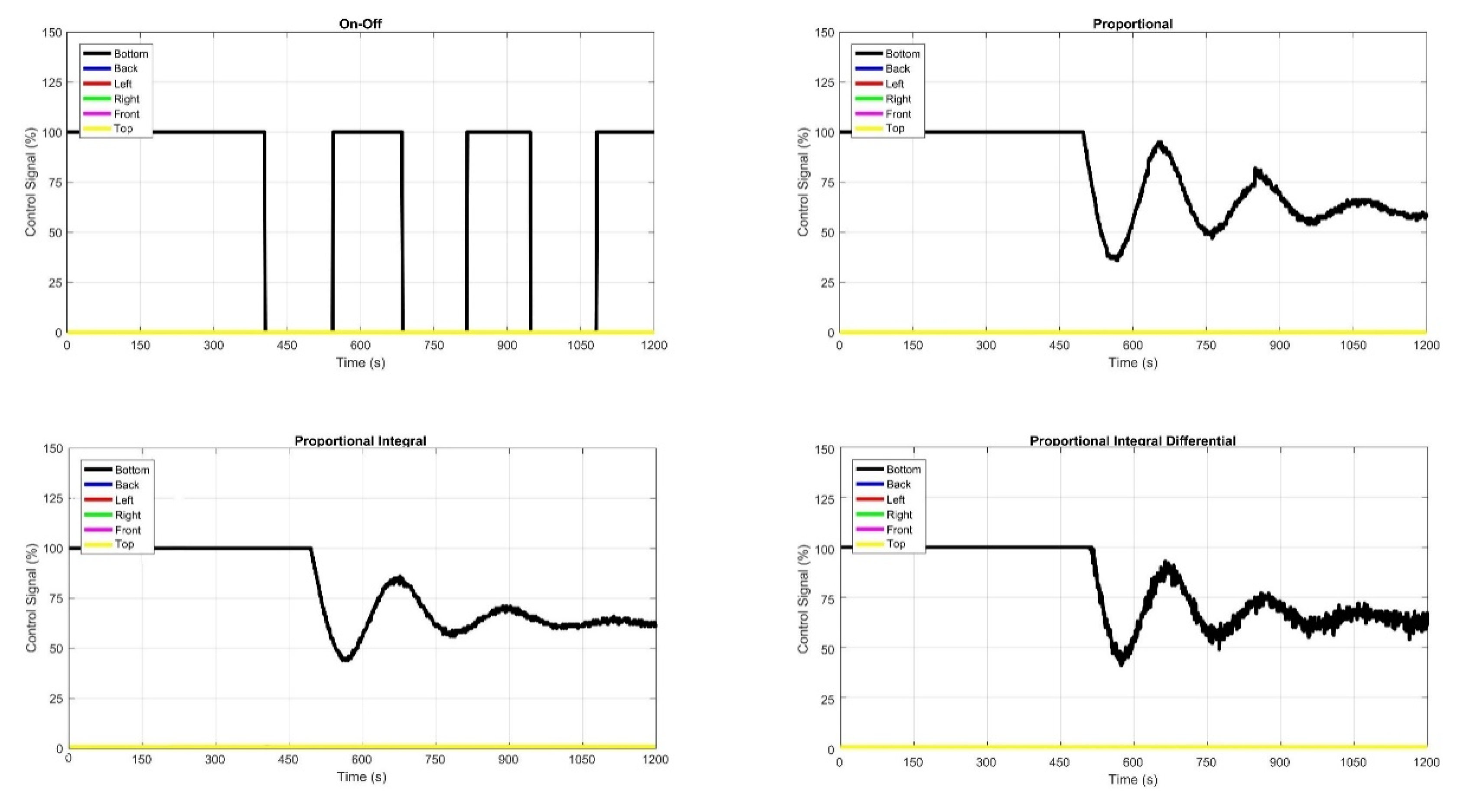

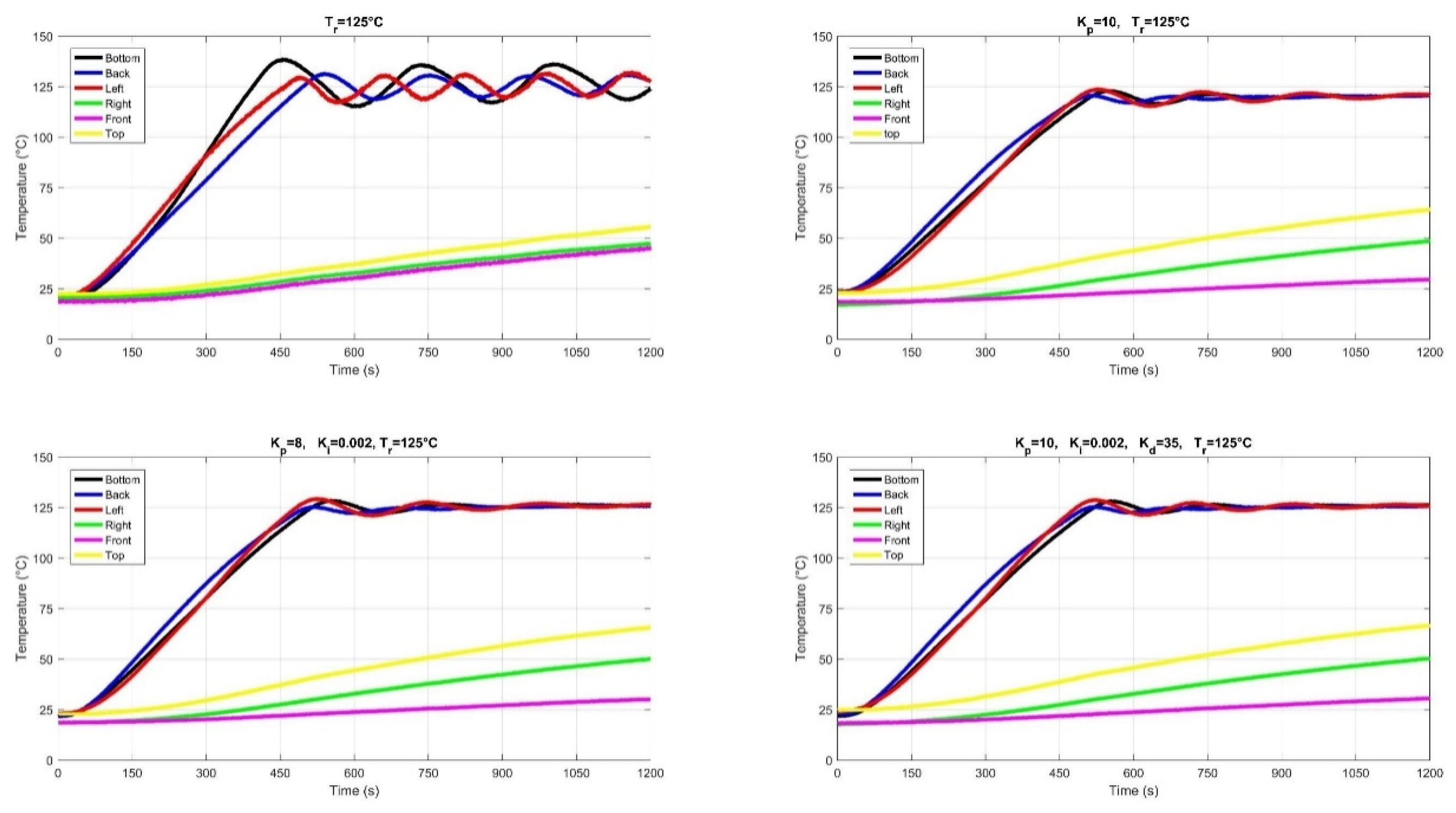

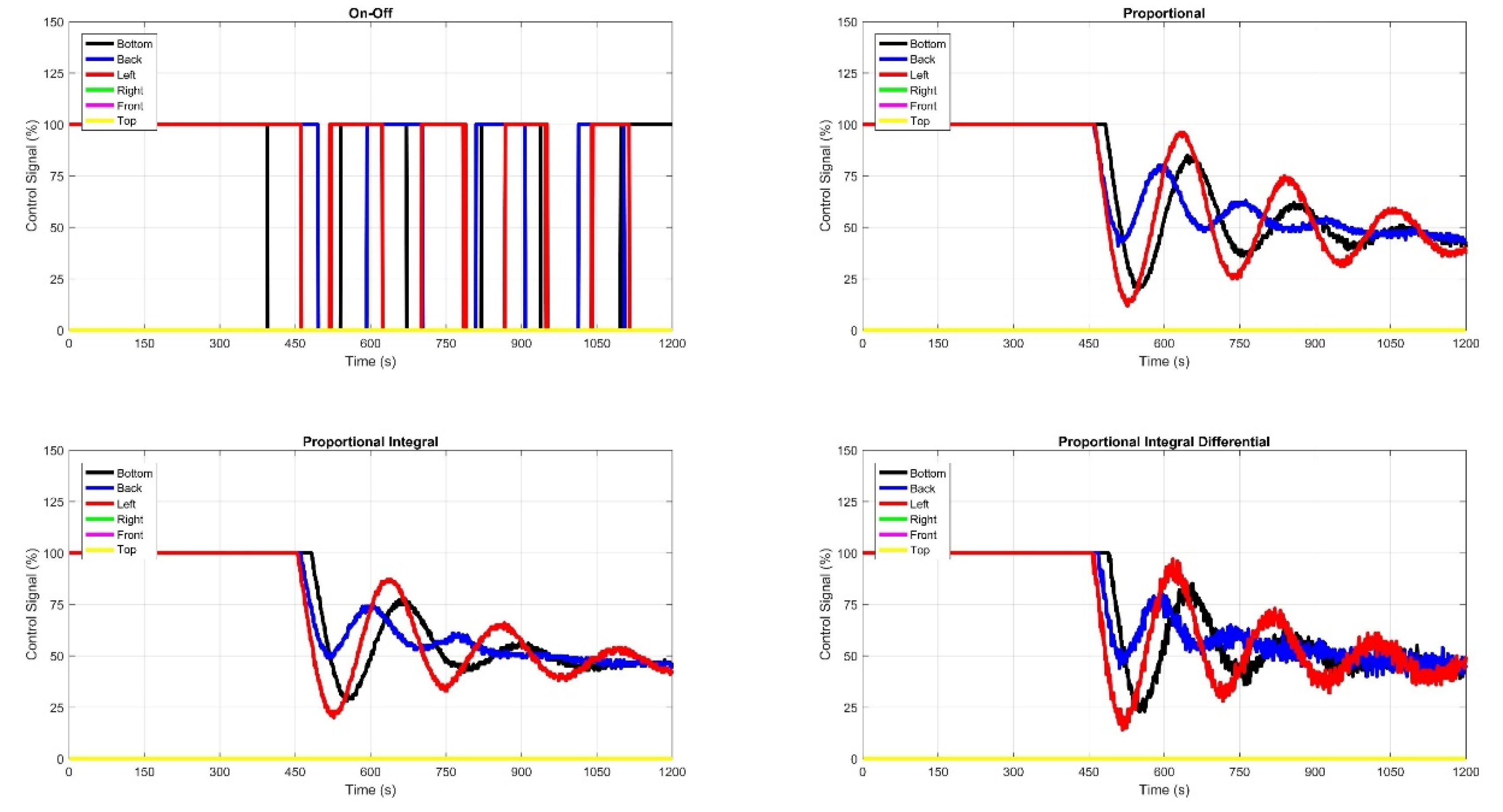

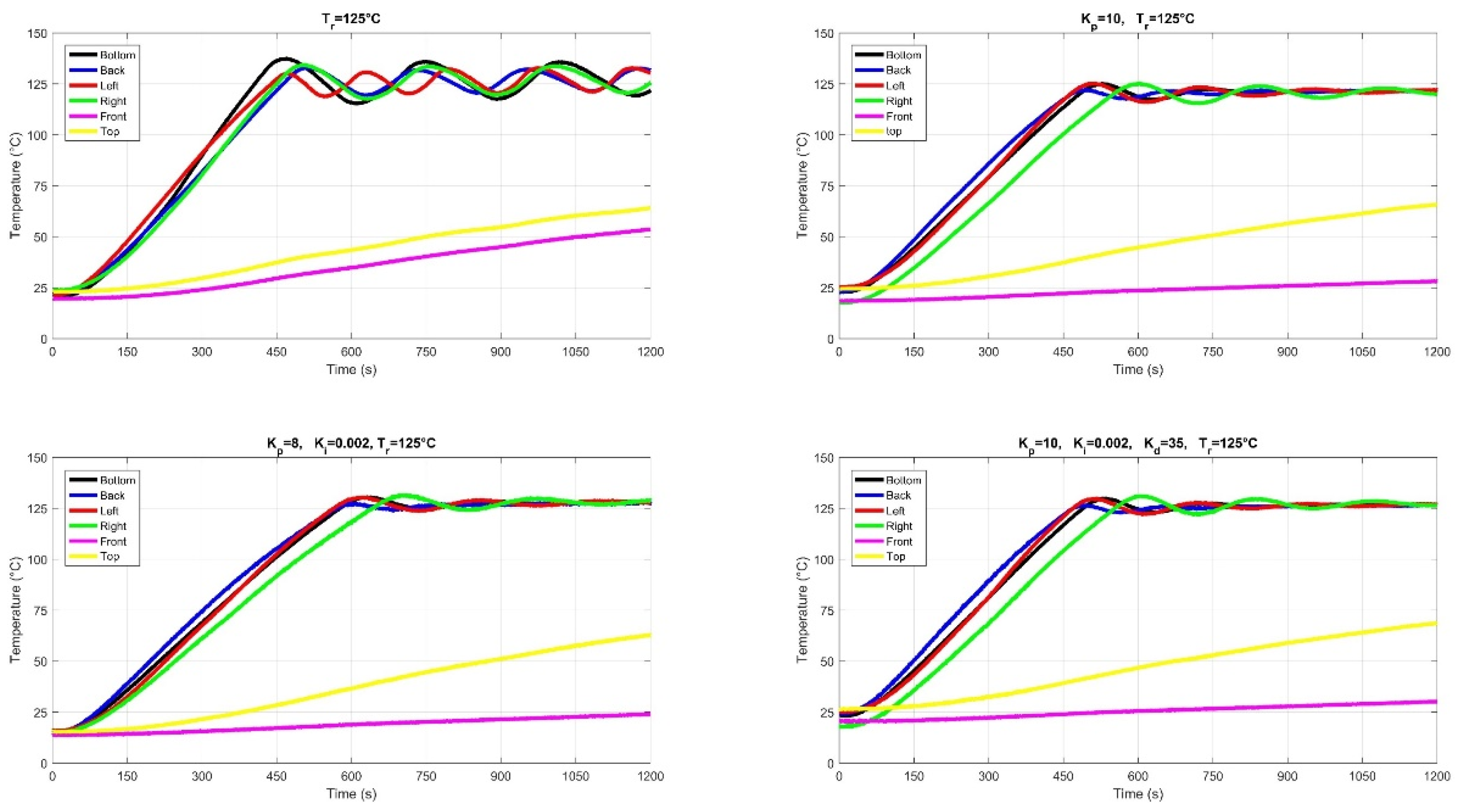

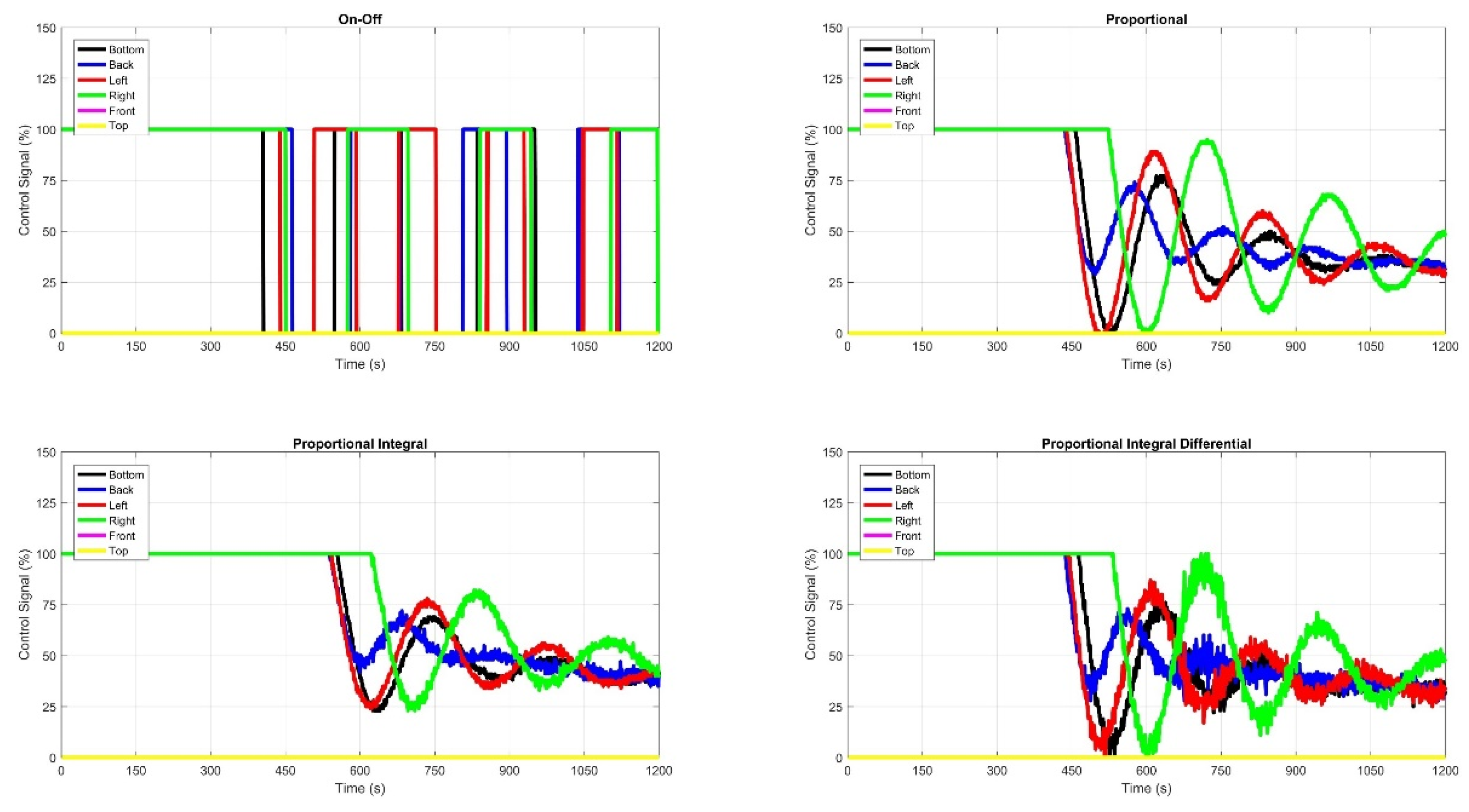

3.1. Temperature Control of a Single Panel

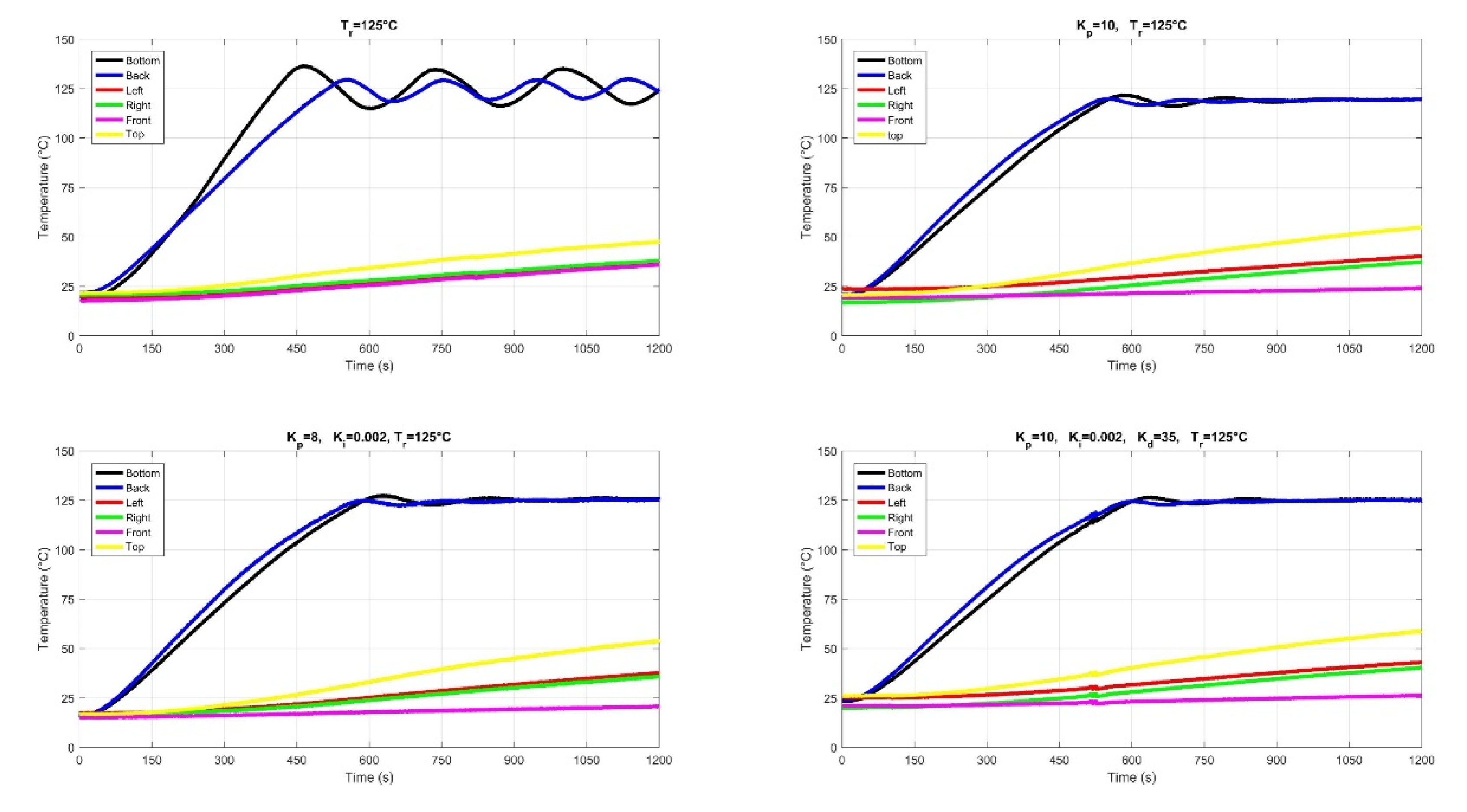

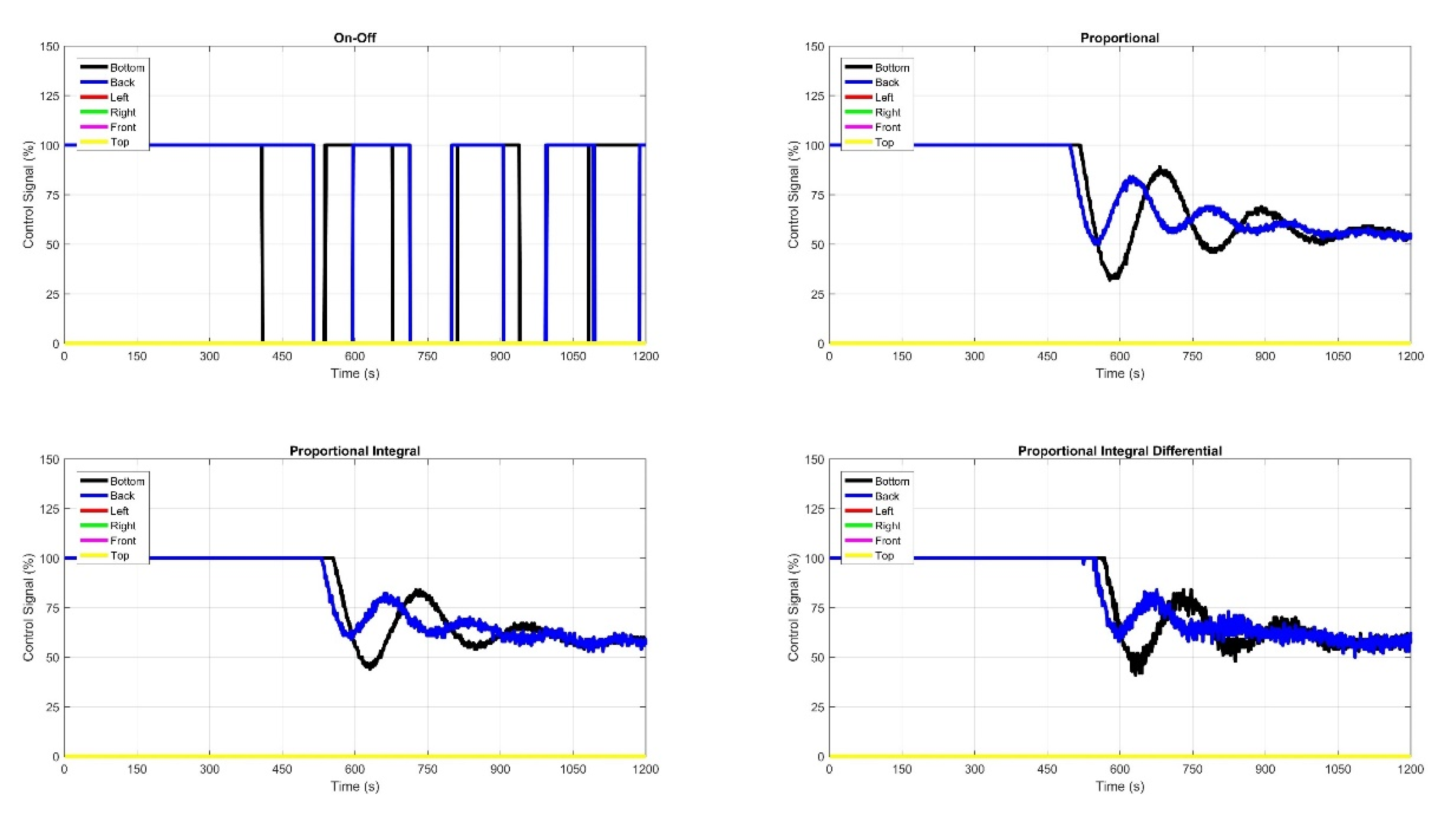

3.2. Temperature Control of Two Panels

3.3. Temperature Control of Three Panels

3.4. Temperature Control of Four Panels

3.5. Temperature Control of Five Panels

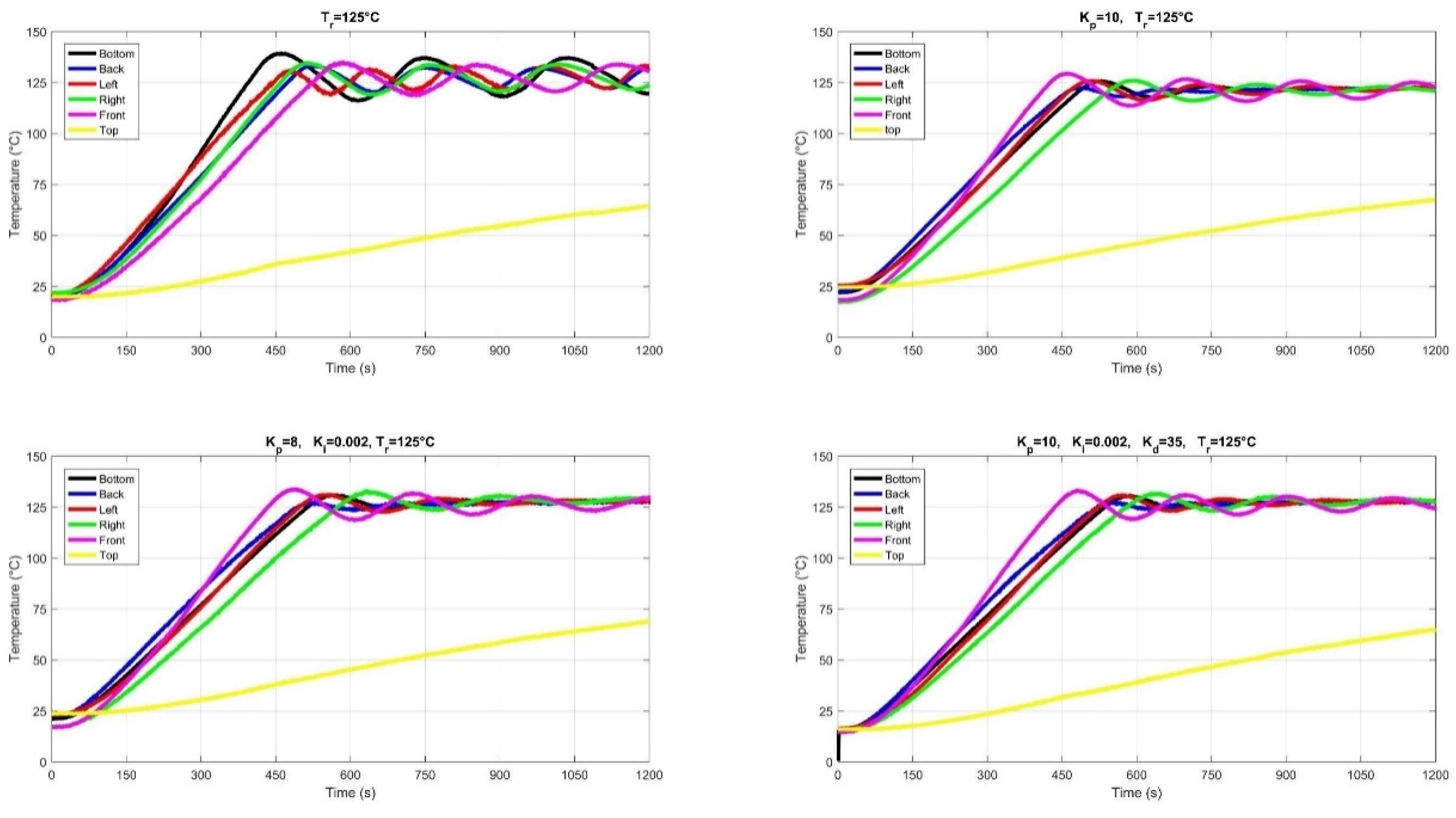

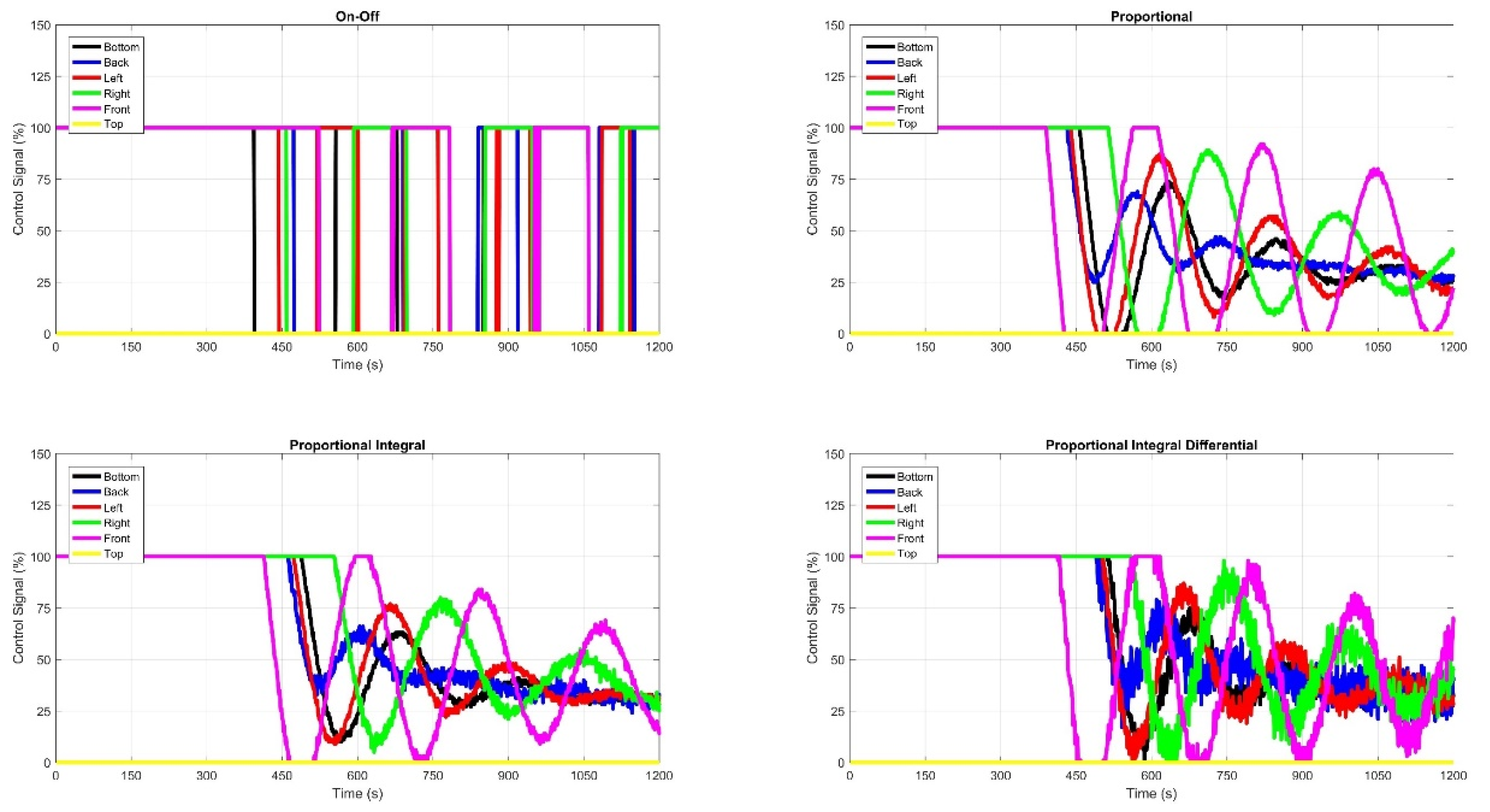

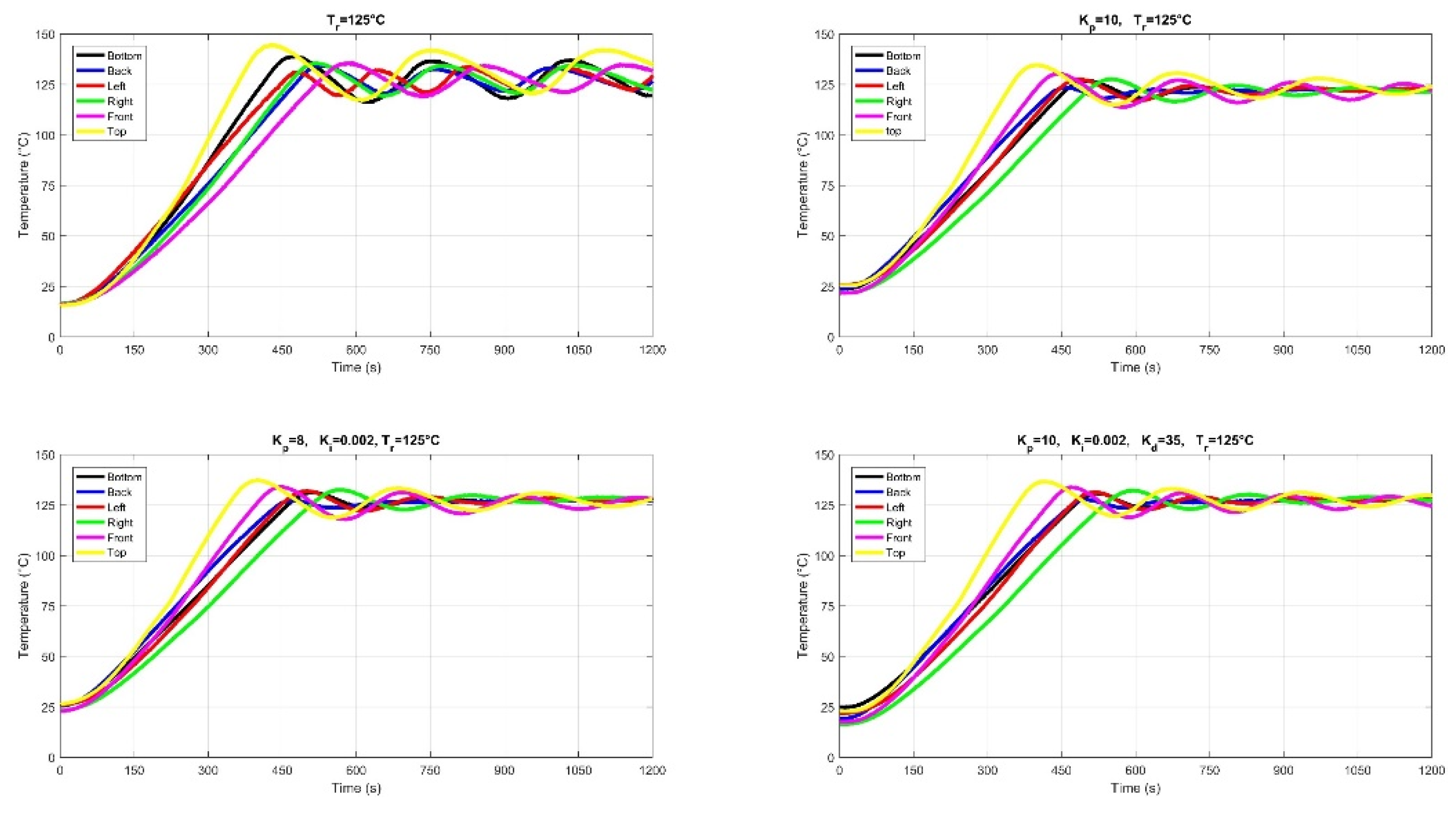

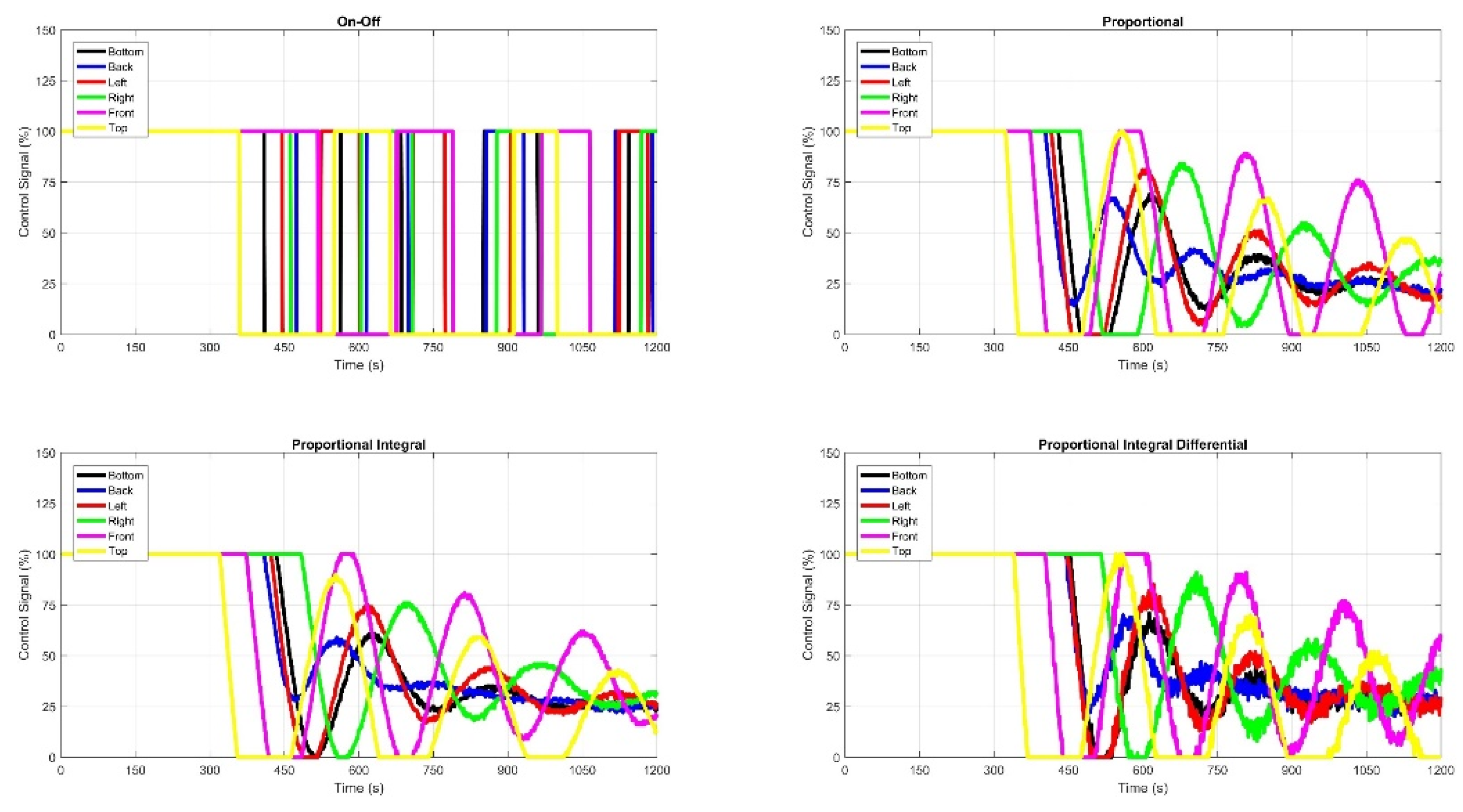

2.6. Temperature Control of Six Panels

4. Conclusion

References

- Hu, X.; Zou, Q.; Zou, H. Design and apllication of fractional order predictive functional control for industirial heating furnace. IEEE Access. 2018, 6, 66565-66575. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Xue, A.; Gao, F. Temperature control of industrial coke furnace using novel state space model predictive control. IEEE Trans. on Ind. Inf. 2017, 10, 2084 – 2092.

- Moon, U. A practical multiloop controller design for temperature control of a tv glass furnace. IEEE Trans. on Control Syst. Technol. 2007 15, 1137 – 1142,.

- Grassi, E.; Tsakalis, K. PID controller tuning by frequency loop-shaping application to diffusion furnace temperature control. IEEE Trans. on Control Syst. Technol. 2000, 8, 842 – 847.

- Hambali, N.; Ang, R.; Ishak, A.; Janin, Z. Various PID controller tuning for air temperature oven system. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Smart Instrumentation, Measurement and Applications (ICSIMA), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 25-25 November 2014, pp. 1-5.

- Kumar, Y.V.P.; Rajesh, A.; Yugandhar, S.; Srikanth, V. Cascaded PID controller design for heating furnace temperature control. IOSR J., vol. 8, pp. 76-83, 2013.

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Ma, K.; Xue, L.; Han, B.; Dong, Y.; Tan, Y.; Gu, C. Design of PID temperature control system based on stm32. Materials Science and Engineering, 2018, 322, pp. 1-10.

- Junming, X.; Haiming, Z.; Lingyun, J.; Rui, Z. Based on Fuzzy - PID Self-Tuning Temperature Control System of the Furnace, International Conference on Electric Information and Control Engineering, Wuhan, China, 15-17 April 2011, pp. 1203-1206.

- Yanmei, W.; Yanzhu, Z.; Baoyu, W. The Control Research of PID in Heating-Furnace System, International Conference on Business Management and Electronic Information, Guangzhou, China, 13-15 May 2011, pp. 260-263.

- Hambali, N.; Janin, Z.; Samsudin, N.; Ishak, A. Process Controllability for air Temperature Oven System Using Open-Loop Reformulated Tangent Method, IEEE International Conference on Smart Instrumentation Measurement and Applications, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 25-27 November 2013, pp. 1-6.

- Aktas, M.; Ceylan, İ.; Dogan, H.; Aktekeli, Z. Designing, Manufacturing and Performance Experiments of Heat Pumb Red Pepper Dryer Assisted Solar Energy. J. of Thermal Scien. and Technol., 2010, 30, 111-120.

- Zheng, F.; Lu, Y.; Fu, S.; Research on Temperature Control of Heating Furnace with Intelligent Proportional Integral Derivative Control Algorithm. Thermal Science, 2020, 24, 3069-3077.

- Teng, F.; Li, H. Adaptive Fuzzy Control for the Electric Furnace. 2009 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Intelligent Systems, Shanghai, China, 20-22 November 2009, pp. 439-443.

- Gözde, H., Toplamacıoglu, M. C.; Kocaarslan, İ.; Şenol, M. A. Particle Swarm Optimization Based PI- Controller Design to Load-Frequency Control of a Two Area Reheat Thermal Power System. J. of Thermal Science and Technology, 2010, 30, 13-21.

- Han, Y.; Jinling, J.; Guangjian, C.; Xizhen, C. Temperature Control of Electric Furnace Based on Fuzzy PID. 2011 International Coriference on Electronics and Optoelectronics (ICEOE 2011), Dalian, China, 29-31 July 2011, pp. 41-44.

- Seo, M.; Ban, J.; Cho, M.; Cho, B.; Koo, Y.; Kim, S. W. Low-Order Model Identification and Adaptive Observer Based Predictive Control for Strip Temperature of Heating Section in Annealin Furnace. IEEE Access. 2021, 9, 53720-53734. [CrossRef]

- Budianto, A.; Pambudi, W. S.; Sumari, S.; Yulianto, A. PID Control Design for Biofuel Furnace using Arduino. Telecommunication, Computing, Electronics and Control (TELKOMNIKA), 2018, 16, 3016-3023.

- Cao, J.; Ye, Q.; Li, P. Resistance Furnace Temperature Control System Based on OPC and MATLAB, Measurement and Control. 2015, 48, 60-64.

- Gürel, A.; E.; Ceylan, İ.; Yılmaz, S. Experimantal Analyses of Heat Pump and Parabolic Trough Solar Fluidized Bed Dryer. J. of Thermal Science and Technology, 2015 35, 107-115,.

- Moon, U.; Lee, K. Y. Hybrid Algorithm with Fuzzy System and Conventional PI Control for the Temperature Control of TV Glass Furnace. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, 2003, 11, 548–554. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Shao, S. Simultaneous Measurement of Three-Dimensional Temperature Distributions and Radiative Properties Based on Radiation Image Processing Technology in a Gas-Fired Pilot Tubular Furnace, Heat Transfer Engineering, 2014, 35, 770-779.

- Zhou, H. Z. S.; Han, D.; Sheng, F.; Zehng, G. G. Visualization of three-dimensional temperature distributions in a large-scale furnace via regularized reconstruction from radiative energy images: numerical studies. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfer, vol. 2002, 72, 361–383.

- Mancuhan, E.; Küçükada, K.; Alpman, E. Mathematical Modeling and Simulation of The Preheating Zone of a Tunnel Kiln. J. of Thermal Science and Technology, 2010, 31, 79-86.

- Correia, D. P.; Ferra, P.; Caldeira-Pıres, A. Flame Three-Dimensional Tomography Sensor for In-Furnace Diagnostics, Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 2000, 28, 431-438.

- Langner, S. M.; Stonis, M.; Semrau, H.; Sauke, O.; Harchegani, L. H.; Behrens, A. Monitoring of an Aluminum Melting Furnace by Means of a 3D Light-Field Camera. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 10-13 December 2017, pp. 784-788.

- Wei, Z.; Ge, H.; Wang, L.; Li, Z. 3-D Temperature Reconstruction of the Flame Field in a Tangentially Fired Furnace. IEEE Transactions on Instrumnetation and Measurment, 2018, 67, 1929-1939.

- Illes, B.; Krammer, O.; Harsanyi, G.; Illyefavi-Vitez, Z.; Szabo, A. 3D Investigations of the Internal Convection Coefficient and Homogeneity in Reflow Ovens. 2007 30th International Spring Seminar on Electronics Technology (ISSE), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 09-13 May 2007, pp. 320-325.

- Chesof, A.; Panaudomsup, S.; Cheypoca, T. Evaluation of Explicit Model Predictive Temperature Control for On-Off Air Conditioner. 17th International Conference on Control Automation and Systems. Jeju, Korea (South), 18-21 October 2017, pp. 621-624.

- Sutcliffe, H. The Principle of Reversed Lag Applied to On-Off Temperature Control. Proceedings of the IEE Part B Electronic and Communication Engineering, 1960, 107, 209-215.

- Roots, W.; Woods, J.; On-Off Control of Thermal Processes. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics and Control Instrumentation, vol. 1969, 16, 136-146. [CrossRef]

- Jie, S.; Zhengwei, L.; Xiaojiang, M. The Application of Fuzzy-PID Control in Heating Furnace Control. International Conference on E-Learning E-Business Enterprise Information Systems and E-Government. Hong Kong, China, 05-06 December 2009, pp. 237-240.

- Bolat, E.; Erkan, K.; Postalcioglu, S. Experimental Autotuning PID Control of Temperature Using Microcontroller. The International Conference on Computer as a Tool, Belgrade, Serbia, 21-24 November 2005, pp. 266-269.

- Lin, H.; Wei, L.; Zikun, N. Development of PID Neural Network Control System for Temperature of Resistance Furnace. International Forum on Information Technology and Applications. Chengdu, China, 15-17 May 2009, pp. 205- 208.

- Miao, X.; Hu, C.; Qiao, Y. A Novel Two Variables PID Control Algorithm in Precision Clock Disciplining System. Electronics 2024,13, 3820. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Xiang, H.; Leng, C.; Dai, T.; He, G. Intelligent Regulation of Temperature and Humidity in Vegetable Greenhouses Based on Single Neuron PID Algorithm.

- Aeenmehr, A.; Yazdizadeh, A.; Ghazizadeh, M. Neuro-PID Control of an Industrial Furnace Temperature. Symposium on Industrial Electronics & Applications. Kuala Lumpur, 04-06 October 2009, pp. 768-772.

- Wang, C.; Zhu, B.; Ma, F.; Sun, J. Design of a PID Controller for Microbial Fuel Cells Using Improved Particle Swarm Optimization. Electronics 2024, 13, 3381. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Huang, B.; Basher, M.K.; Rob, M.A.; Jiang, Y. Fuzzy PID Control Design of Mining Electric Locomotive Based on Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Electronics 2024, 13, 1855. [CrossRef]

- Cabuker, A.C.; Almalı, M.N. Metaheuristic Algorithm-Based Proportional–Integrative–Derivative Control of a Twin Rotor Multi Input Multi Output System. Electronics 2024, 13, 3291. [CrossRef]

- Alyoussef, F.; Kaya, I.; Akrad, A. Robust PI-PD Controller Design: Industrial Simulation Case Studies and a Real-Time Application. Electronics 2024, 13, 3362. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yang, L.; Ye, A.; Zhao, Z.; Shen, B. Grouping Neural Network-Based Smith PID Temperature Controller for Multi-Channel Interaction System. Electronics 2024, 13, 697. [CrossRef]

- Silaa, M.Y.; Barambones, O.; Bencherif, A. A Novel Adaptive PID Controller Design for a PEM Fuel Cell Using Stochastic Gradient Descent with Momentum Enhanced by Whale Optimizer. Electronics 2022, 11, 2610. [CrossRef]

| Controller | Kp | Ki | Kd |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | 12.320 | - | - |

| PI | 11.088 | 0.0047 | - |

| PID | 14.780 | 0.0079 | 35 |

| Controller | Kp | Ki | Kd |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | 10 | - | - |

| PI | 8 | 0.002 | - |

| PID | 10 | 0.002 | 35 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 10.34 | - | 0.88 | 1.05 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1180.00 | 1161.00 | 1140.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 466.00 | 58.00 | 561.00 | 577.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 5.90 | 0.80 | 0.50 |

| IAE | 3.07×104 | 3.30×104 | 2.80×104 | 2.91×104 |

| ISE | 2.13×106 | 2.09×106 | 1.92×106 | 2.07×106 |

| ITAE | 7.52×106 | 8.82×106 | 5.37×106 | 5.48×106 |

| ITSE | 2.66×108 | 2.98×108 | 2.46×108 | 2.69×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 4.03 | - | 0.98 | 1.00 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1109.00 | 1144.00 | 1040.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 555.00 | 556.00 | 585.00 | 601.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 4.90 | 0.40 | 0.30 |

| IAE | 3.05×104 | 3.28×104 | 3.02×104 | 2.88×104 |

| ISE | 2.13×106 | 2.11×106 | 2.25×106 | 2.00×106 |

| ITAE | 6.63×106 | 8.56×106 | 5.55×106 | 5.44×106 |

| ITSE | 2.80×108 | 2.91×108 | 2.88×108 | 2.63×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 9.28 | - | 2.00 | 1.31 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1100.00 | 1127.00 | 1099.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 464.00 | 574.00 | 627.00 | 640.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 5.70 | 0.30 | 0.20 |

| IAE | 4.04×104 | 3.48×104 | 3.27×104 | 3.12×104 |

| ISE | 5.12×106 | 2.31×106 | 2.46×106 | 2.22×106 |

| ITAE | 7.38×106 | 9.11×106 | 6.45×106 | 6.18×106 |

| ITSE | 4.63×108 | 3.40×108 | 3.42×108 | 3.16×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 10.83 | - | 2.81 | 2.52 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1083.00 | 1150.00 | 1081.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 454.00 | 550.00 | 553.00 | 555.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 4.00 | 0.70 | 0.40 |

| IAE | 3.03×104 | 3.25×104 | 2.92×104 | 2.89×104 |

| ISE | 2.09×106 | 2.15×106 | 2.12×106 | 2.09×106 |

| ITAE | 7.35×106 | 8.05×106 | 5.43×106 | 5.40×106 |

| ITSE | 3.59×108 | 3.01×108 | 2.74×108 | 2.68×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 4.70 | - | 1.31 | 1.30 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1067.00 | 1102.00 | 1063.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 541.00 | 517.00 | 514.00 | 511.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 5.15 | 0.90 | 0.40 |

| IAE | 3.09×104 | 3.05×104 | 2.65×104 | 2.64×104 |

| ISE | 2.18×106 | 1.94×106 | 1.91×106 | 1.90×106 |

| ITAE | 6.82×106 | 7.56×106 | 4.50×106 | 4.47×106 |

| ITSE | 2.87×108 | 2.53×108 | 2.25×108 | 2.24×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 5.68 | - | 3.46 | 3.09 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1128.00 | 1097.00 | 1088.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 488.00 | 526.00 | 522.00 | 516.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 4.40 | 0.95 | 0.80 |

| IAE | 3.19×104 | 3.27×104 | 2.89×104 | 2.87×104 |

| ISE | 2.22×106 | 2.23×106 | 2.13×106 | 2.10×106 |

| ITAE | 6.93×106 | 7.99×106 | 5.35×106 | 5.26×106 |

| ITSE | 5.68 | - | 3.46 | 3.09 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 9.99 | 0.09 | 4.44 | 3.92 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1048.00 | 1116.00 | 1040.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 455.00 | 528.00 | 632.00 | 534.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.20 | 3.60 | 3.10 |

| IAE | 3.03×104 | 3.09×104 | 3.53×104 | 2.86×104 |

| ISE | 2.08×106 | 2.11×106 | 2.67×106 | 2.03×106 |

| ITAE | 7.37×106 | 7.02×106 | 7.87×106 | 5.50×106 |

| ITSE | 2.60×108 | 2.81×108 | 3.88×108 | 2.58×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 6.45 | - | 2,90 | 1.57 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1077,00 | 1082,00 | 1030.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 524.00 | 497,00 | 606,00 | 488.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3,95 | 2,20 | 1.90 |

| IAE | 3.01×104 | 2.91×104 | 3.28×104 | 2.54×104 |

| ISE | 2.10×106 | 1.91×106 | 2.46×106 | 1.79×106 |

| ITAE | 6.72×106 | 6.62×106 | 6.82×106 | 4.37×106 |

| ITSE | 2. 69×106 | 2.38×106 | 3.34×106 | 2.06×106 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 6.29 | 0.18 | 4.33 | 3.85 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1026.00 | 1041.00 | 1021.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 477.00 | 505.00 | 612.00 | 510.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.80 | 2.60 | 2.30 |

| IAE | 3.76×104 | 3.07×104 | 3.57×104 | 2.82×104 |

| ISE | 2.89×106 | 2.10×106 | 2.75×106 | 2.04×106 |

| ITAE | 7.06×106 | 6.99×106 | 7.86×106 | 5.30×106 |

| ITSE | 3.60×108 | 2.81×108 | 4.03×108 | 2.58×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 7.49 | 0.20 | 5.22 | 4.85 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1128.00 | 1164.00 | 1092.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 583.00 | 599.00 | 700.00 | 605.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.10 | 3.40 | 3.05 |

| IAE | 4.10×104 | 3.68×104 | 3.95×104 | 3.45×104 |

| ISE | 3.16×106 | 2.71×106 | 3.03×106 | 2.60×106 |

| ITAE | 7.12×106 | 5.30×106 | 9.52×106 | 7.44×106 |

| ITSE | 3.86×108 | 4.14×108 | 4.93×108 | 3.78×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 11.49 | 0.58 | 4.52 | 4.54 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1044.00 | 1032.00 | 1037.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 461.00 | 527.00 | 566.00 | 582.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.00 | 2.30 | 1.90 |

| IAE | 3.10×104 | 3.09×104 | 3.05×104 | 3.37×104 |

| ISE | 3.08×106 | 2.19×106 | 2.16×106 | 2.55×106 |

| ITAE | 7.61×106 | 6.79×106 | 6.61×106 | 7.21×106 |

| ITSE | 3.63×108 | 2.92×108 | 2.90×108 | 3.54×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 6.68 | - | 2.86 | 2.76 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1055.00 | 1052.00 | 1093.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 523.00 | 484.00 | 514.00 | 550.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.10 | 2.00 | 1.90 |

| IAE | 3.10×104 | 2.89×104 | 2.79×104 | 3.10×104 |

| ISE | 2.21×106 | 1.97×106 | 1.94×106 | 2.34×106 |

| ITAE | 6.86×106 | 6.32×106 | 5.43×106 | 6.15×106 |

| ITSE | 2.89×108 | 2.42×108 | 2.40×108 | 3.01×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 6.62 | 0.62 | 4.82 | 4.07 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1117.00 | 1099.00 | 1064.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 475.00 | 591.00 | 633.00 | 637.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 2.90 | 2.90 | 2.85 |

| IAE | 4.83×104 | 3.10×104 | 3.05×104 | 3.41×104 |

| ISE | 4.97×106 | 2.18×106 | 2.16×106 | 2.65×106 |

| ITAE | 6.16×106 | 6.76×106 | 6.52×106 | 7.24×106 |

| ITSE | 4.63×108 | 2.95×108 | 2.90×108 | 3.72×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 7.69 | 0.79 | 6.34 | 5.34 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1100.00 | 1080.00 | 1038.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 483.00 | 507.00 | 546.00 | 569.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.60 | 2.70 | 2.60 |

| IAE | 3.19×104 | 3.63×104 | 3.65×104 | 3.74×104 |

| ISE | 3.28×106 | 2.74×106 | 2.72×106 | 2.90×106 |

| ITAE | 7.32×106 | 7.24×106 | 8.47×106 | 8.58×106 |

| ITSE | 5.07×108 | 4.12×108 | 4.08×108 | 4.45×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 8.02 | 3.54 | 7.05 | 6.54 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1114.00 | 1135.00 | 1094.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 414.00 | 459.00 | 486.00 | 485.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.60 | 2.95 | 2.90 |

| IAE | 3.58×104 | 3.01×104 | 3.00×104 | 3.04×104 |

| ISE | 2.63×106 | 2.24×106 | 2.22×106 | 2.36×106 |

| ITAE | 8.77×106 | 6.51×106 | 6.06×106 | 6.00×106 |

| ITSE | 3.91×108 | 2.74×108 | 2.72×108 | 2.85×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 11.13 | 1.59 | 9.82 | 4.60 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1020.00 | 1004.00 | 919.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 473.00 | 498.00 | 506.00 | 522.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 2.70 | 3.30 | 2.65 |

| IAE | 3.20×104 | 2.90×104 | 2.72×104 | 2.85×104 |

| ISE | 2.28×106 | 2.06×106 | 1.83×106 | 1.99×106 |

| ITAE | 7.88×106 | 6.02×106 | 5.52×106 | 5.75×106 |

| ITSE | 2.92×108 | 2.57×108 | 2.26×108 | 2.54×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 7.62 | - | 2.34 | 2.42 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1009.00 | 1070.00 | 933.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 430.00 | 461.00 | 468.00 | 500.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 2.80 | 2.50 | 2.30 |

| IAE | 3.27×104 | 2.71×104 | 2.47×104 | 2.82×104 |

| ISE | 2.42×106 | 1.83×106 | 1.68×106 | 2.06×106 |

| ITAE | 7.23×106 | 5.55×106 | 4.58×106 | 5.39×106 |

| ITSE | 3.22×108 | 2.15×108 | 1.89×108 | 2.48×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 6.89 | 2.12 | 5.57 | 5.12 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1013.00 | 1110.00 | 981.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 481.00 | 551.00 | 563.00 | 595.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.05 | 3.80 | 3.00 |

| IAE | 2.98×104 | 2.92×104 | 2.78×104 | 3.05×104 |

| ISE | 2.17×106 | 2.05×106 | 1.93×106 | 2.25×106 |

| ITAE | 6.37×106 | 6.12×106 | 5.58×106 | 6.19×106 |

| ITSE | 2.92×108 | 2.64×108 | 2.40×108 | 2.96×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 8.48 | 2.19 | 6.00 | 5.78 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1099.00 | 1072.00 | 1011.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 480.00 | 490.00 | 496.00 | 515.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.00 | 2.50 | 2.10 |

| IAE | 3.40×104 | 3.33×104 | 3.15×104 | 3.53×104 |

| ISE | 2.55×106 | 2.41×106 | 2.22×106 | 2.71×106 |

| ITAE | 7.95×106 | 6.19×106 | 6.89×106 | 7.83×106 |

| ITSE | 3.50×108 | 3.45×108 | 3.09×108 | 3.95×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 8.59 | 4.33 | 7.28 | 7.02 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1127.00 | 1059.00 | 1035.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 319.00 | 398.00 | 400.00 | 414.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.70 | 2.90 | 2.40 |

| IAE | 3.69×104 | 2.83×104 | 2.63×104 | 2.93×104 |

| ISE | 2.76×106 | 2.00×106 | 1.82×106 | 2.21×106 |

| ITAE | 9.09×106 | 6.02×106 | 5.20×106 | 5.78×106 |

| ITSE | 4.15×108 | 2.39×108 | 2.05×108 | 2.64×108 |

| Metric | On/Off | P | PI | PID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overshoot (%) | 15.71 | 7.70 | 9.84 | 9.33 |

| Settling Time (s) | - | 1137.00 | 1180.00 | 1135.00 |

| Rise Time (s) | 426.00 | 440.00 | 451.00 | 472.00 |

| Offset Error (°C) | - | 3.20 | 2.80 | 2.75 |

| IAE | 3.31×104 | 2.54×104 | 2.40×104 | 2.61×104 |

| ISE | 2.26×106 | 1.73×106 | 1.58×106 | 1.84×106 |

| ITAE | 9.61×106 | 5.23×106 | 4.78×106 | 5.25×106 |

| ITSE | 3.13×108 | 2.64×108 | 1.65×108 | 2.01×108 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).