1. Introduction

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by recurrent partial (hypopnea) and complete (apnea) narrowing episodes of the upper airway flow. These respiratory disorders cause intermittent hypoxemia, alterations of the intrathoracic pressure, and sleep fragmentation harming the quality-of-life and negatively impacting physical and mental health [

1,

2]. It is the most common respiratory sleep-related disorder affecting nearly 425 million middle-aged adults; the incidence between 20% and 60% was much bigger in older than 65 years of age, with significant difference in the Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) [

3].

The severity of OSA can be classified according to the number of respiratory events observed per hour called Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI): mild OSA (AHI – 14.9 events/h), moderate OSA (15 – 29.9 events/h) and severe OSA (> 30 events∕h) [

2]. Studies showed that patients with OSA do not feel motivated to practice physical exercise due to daytime somnolence and fatigue, reducing substantially the motivation and time for physical activity (PA), however, low levels of PA are associated with higher odds of developing OSA and are associated with risk factors as obesity and metabolic syndrome related to the increase of the disease severity [

4].

Due to the interruptions of air flow in OSA, intermittent hypoxia and reoxygenation events occur releasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) which are related to oxidative stress (OS), an imbalance between free oxidant radicals and ineffective antioxidant capacity of degradation as mechanism of internal defense [

5,

6]. The role of OS in obstructive sleep apnea is related to an increase of the levels of reactive oxygen species in patients with OSA. ROS are chemically produced molecules in the normal metabolism of oxygen, which if elevated cause disturbance between its production and antioxidant defense mechanism, characterizing the status of oxidative stress. These highly reactive molecules can cause modifications in the DNA, cellular death,21 apoptosis, and inflammation, contributing for the onset of several diseases [

7].

Serum malondialdehyde (MDA) is an important biomarker of OS, being produced from the degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids through enzymatic or non-enzymatic reactions [

8]. Its concentrations are associated with nocturnal oxygen desaturation below 85%. The monitoring of this biomarker in patients with OSA is important to follow up their oxidative balance [

9]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis study [

8], the levels of MDA circulating levels of patients with OSA were higher in OSAG versus control group. Obese men are at greater risk of developing obstructive sleep apnea due to fat deposition around the neck and abdominal region, as opposed to women, showing a positive correlation between AHI severity and all measures of obesity, regardless of age. The severity of AHI is reduced by weight loss through physical activity [

10]. The relationship of physical activity in OSA are still being investigated, however, studies showed that regular aerobic physical exercise can increase antioxidative mechanisms, reducing considerably the levels of OS in healthy women [

11]. Significant reductions of AHI and daytime somnolence were found in OSA, further to better sleep and peak of oxygen consumption (VO

2peak) [

12].

Studies relating the level of PA in individuals with OSA and the adjacent aspects of the disease as obesity, cardiovascular disorders and severity are well described in the literature [

13,

14], contrary to associations between the level of PA with oxidative stress in patients with OSA. This may suggest new recommendations and interventions based in regular practice of physical activity to treat obstructive sleep apnea to improve the sleeping quality and reduction of oxidative stress. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the level of physical activity through IPAQ, the levels of oxidative stress by the determination of serum MDA, and quality of sleep of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and compare with control group.

2. Results

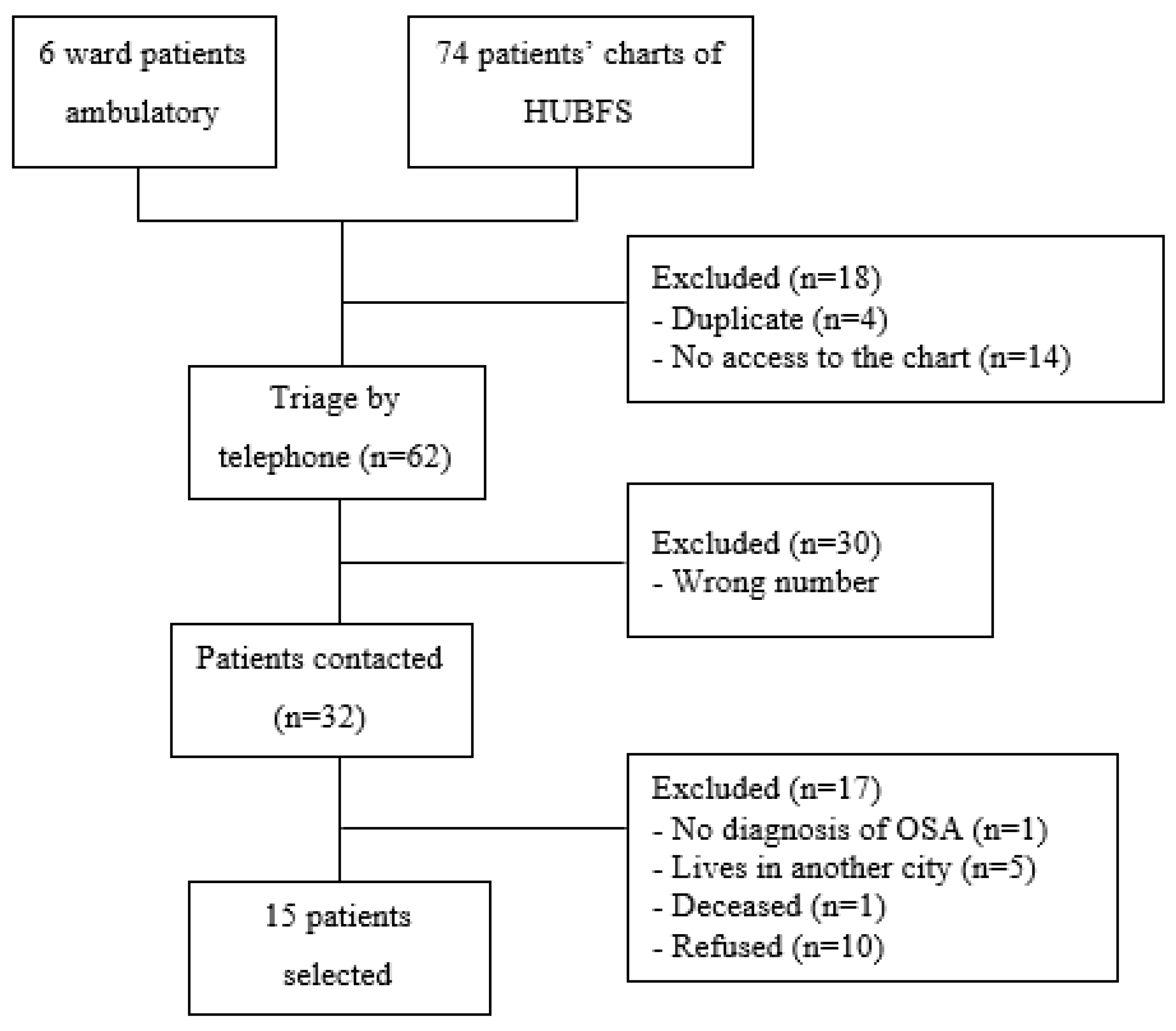

The enrollment of the OSAG participants was based in the list of 74 patients who underwent the Polysomnography test at “Hospital Universitário Bettina Ferro de Souza (HUBFS)” and in the six patients registered at the physiotherapy ward of HUJBB. Of these, only 60 charts were accessed to collect personal data, and four were already registered at the ward. In all, 15 patients of both sexes accepted to join the study.

Figure 2 shows a summary of the flowchart of the OSAG group. The CG was formed by spontaneous demand paired by age-range (±2 years) versus OSAG. A total of 22 individuals were eligible to participate in the control group.

The sample was formed by middle-aged adults of both sexes, non-smokers and with other non-communicable chronic diseases (diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension). The OSAG had low education level, high BMI, abdominal and neck circumference (

Table 1) and apnea hypopnea index= 20±4 events∕h. The calculation of the power of the sample considered the difference among MDA concentrations between the groups with confidence interval of 95% and sampling error of 10%, with power of 100% by test t for independent samples.

Figure 1.

Summary of the flowchart of the enrollment of patients with OSA.

Figure 1.

Summary of the flowchart of the enrollment of patients with OSA.

A significant difference in the concentration of serum MDA between the groups was found. OSAG presented significantly more elevated levels of lipid peroxidation versus CG. No significant difference between the groups for the antioxidant marker GSH was found. IPAQ score was lower in CG with no significant statistical difference. (

Table 2). In addition, both groups showed to be physically active per the IPAQ classification (

Table 3).

For the PSQI no statistically significant difference was found between the groups but for both, poor sleep quality was detected (

Table 4).

Linear Regression Model is described in

Table 5.

3. Discussion

The sample consisted in middle-aged individuals of both sexes, non-smokers and with non-communicable diseases, OSAG had higher BMI, larger cervical and abdominal measures, low education levels and higher circulating serum MDA levels when compared with CG. Both groups were classified as physically active by IPAQ but categorized with poor sleep quality when evaluated by PSQI but without statistically significant difference.

The relation between weight change and onset of obstructive sleep apnea is being investigated as noticed in a 4-year follow-up study of a Wisconsin sleep cohort, concluding that 10% of weight gain increases the severity of OSA in 32% and 6-fold the odds of developing moderate to severe OSA [

24]. The present study showed values statistically significantly higher for BMI, cervical and abdominal circumference in the OSAG

versus CG. Adipose deposition in pharyngeal area increases surrounding tissue pressure leading to narrowing of the upper airways. Therefore, adults with deposition of fat around the neck, thorax and abdominal area have more risks of developing OSA [

25].

It is known that physical exercise is an important asset to produce physiologic adaptations such as reduction of body weight, lowering of OSA severity and daytime somnolence, in addition to increasing sleep efficiency [

26]. However, the clinical characteristics of obstructive sleep apnea as fatigue and mood changes can favor the physical inactivity of these patients and with this, contribute to augment the disease’s severity [

27]. Low cost and easily applicable tools evaluating physical activity and sedentary behavior of the adult population are being utilized by investigators all over the world since methods adopting physiological markers or pedometers can be expensive [

28].

The results showed that both groups are physically active but no significant difference between OSAG and CG when evaluated by IPAQ (

p = 0.579) was found. A cross-sectional study compared the level of physical activity of four groups: (a) non-OSA, (b) mild OSA, (c) moderate OSA and (d) severe OSA. The analyzes showed statistical difference for IPAQ among the groups (

p < 0.001). Comparing with group (a), the scores were, on average, lower in the groups mild, moderate, and severe OSA (47.7%; 57.8% and 69.7%, respectively) [

29]. Although associations among levels of PA and OSA have been described, there are limitations to be considered in relation to the results as most of the studies evaluate the level of physical activity subjectively through questionnaires. Given this, more information about the type, frequency, duration, and intensity of the exercise practiced by the population investigated is necessary to reach more accurate results [

4].

Studies have been demonstrating the association of oxidative stress with the onset and severity of OSA. The excessive accumulation of free radicals due to imbalance between the antioxidant defenses and oxidant production system is related to several damages in fundamental cellular components as lipids, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids that if modified can lead to the appearance of several pathologies as obstructive sleep apnea [

30]. Therefore, to measure the oxidative stress to determine the severity and progression of the disease is critical. OS-related molecules reacting to TBARS and MDA are being investigated in this population. In prolonged conditions of OS, MDA levels reach elevated levels in the organism [

31].

The results showed that serum MDA concentrations were positively higher in OSAG (5.62 ± 1.98) when compared with CG (0.94 ± 0.76), showing statistic relevance (

p < 0.000). Ekin et al [

32] conducted a study with 90 participants in an OSAG classified with mild, moderate, and severe AHI and 30 healthy individuals in CG and concluded that MDA levels in the OSAG were significantly higher than in the CG (

p < 0.001). In addition, MDA levels are directly connected to the severity of the disease, meaning that individuals with severe OSA have higher levels of MDA in the organism (20.15± 5.56) while in the mild classification, lower levels of serum MDA (7.63 ± 1.19) were detected.

The antioxidant defense system is activated as physiological mechanism of the organism to reverse the oxidative stress and with it, biomarkers, and glutathione attempt to rebalance and reduce the damages the oxidation process has caused. Glutathione in its reduced form plays an important role in controlling the process of detoxication, antiviral defense and immune response [

33]. The lower the content of glutathione in a cell, smaller is the likelihood of its survival [

34]. Both groups of this study present similar levels of GSH without significant statistical difference. Zhang et al [

35] showed that glutathione and dismutase superoxide levels were significantly diminished in the OSAG while MDA concentrations were remarkably greater (

p < 0.01) compared with control, showing poor antioxidant response in these patients.

Both groups presented poor sleep quality according to PSQI evaluation, however, with no statistical significance (

p = 0.408). In a randomized, controlled study with 139 older adults with sleep disorders divided in two groups (intervention 67 and control, 72), it was applied an exercise protocol to evaluate the influence on the sleep quality and quality of life of the patients. Both groups had PSQI scores similar to the beginning of the study (9.8 ± 3.6

vs. 9.2 ± 3.4,

p = 0.30). At the end of 24 weeks of intervention, the case group had significant reduction of PSQI scores compared to control (6.6 ± 3.9

vs. 9.3 ± 47, respectively), reporting relevant improvement of the sleep quality [

36].

Another study investigating the inspiratory muscle training (IMT) and oropharyngeal exercise training (OET) in patients with OSA compared with CG concluded that in the end of the intervention there was significant reduction of the cervical and abdominal circumferences of the IMT group

versus control. In addition, both groups improved the total score of PSQI treatment (

p < 0.05), and in the snoring frequency evaluated by the Berlin Questionnaire (

p < 0.001) [

37]. These results highlight the importance of practicing exercises to ameliorate the sleep-related variables and patients’ capacity of performing exercises.

The limitations of the study include the COVID-19 pandemic scenario which influenced the determination of the sample size. In addition, only one oxidative stress marker, serum MDA by the TBARS method was utilized involving spectrophotometry. Most likely, more expressive results would be obtained if other oxidant and antioxidant markers were utilized to compare more accurately the REDOX (reduction-oxidation) balance. Another limitation was the use of IPAQ alone to evaluate the level of physical activity as the subjective evaluation of the instrument could be complemented by physiologic markers or pedometers to measure the movement.

4. Materials and Methods

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and Ordinance 466/12 of the National Health Council for studies with human beings [

15] and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Complexo Hospitalar” of “Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA)” report number 4.483.804. All the volunteers agreed to join the study by signing the Informed Consent Form (ICF).

Cross-sectional, descriptive, analytical, and quantitative study based in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [

16]. Patients diagnosed with Obstructive Sleep Apnea registered at the physiotherapy ward of “Hospital Universitário João de Barros Barreto (HUJBB), and in “Hospital Universitário Bettina Ferro de Souza (HUBFS)” or who were referred for evaluation and individuals with no sleep disorders were enrolled. The sample was divided in two groups: Obstructive Sleep Apnea Group (OSAG) and control group (CG) with individuals with no sleep disorders.

The inclusion criteria for the OSAG were: (a) individuals of both sexes, older than 18 years of age, regardless of marital status or education, diagnosis of mild, moderate, and severe OSA according to the number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep (Apnea Hypopnea Index – AHI), clinically stable who received physiotherapeutic treatment or referred for respiratory physiotherapy evaluation of sleep disorders. For the CG, the inclusion criteria were (b) individuals of both sexes, older than 18 years of age, regardless of marital status or education who agreed to participate in all the study phases. Smokers, individuals with blood coagulation disorders or metabolic diseases as dyslipidemia and anemia in use of antioxidant and iron supplementation in the last two months were excluded further to those who had no sleep disorders evaluated by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), who spontaneously withdrew during the study or refused to sign the Informed Consent Form (ICF). [

17]

Enrollment, data collection, demographical data and information about the physical activity occurred from July to October 2021 at the “Ambulatório de Fisioterapia Respiratória do Complexo Hospitalar” of “Universidade Federal do Pará” – “Hospital Universitário João de Barros Barreto (HUJBB)”. Biological specimens were collected, and oxidative stress was analyzed at the “Laboratório de Estresse Oxidativo” of “Núcleo de Medicina Tropical (NMT)” of “Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA)”.

Demographic, anthropometric, and clinical data were collected at the respiratory physiotherapy ward, based on the physiotherapeutic evaluation forms for Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

Translated and validated by Bertolazi [

18], Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) evaluates the sleep habits during the previous month only through seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications and daytime dysfunction. The sum of these components results in a general score from 0 to 21 points, the higher the score, the worse is the sleep quality. It still categorizes the participants in good sleep quality (score ≤ 5 points) and poor sleep quality (score > 5 points). The instrument presents high values of specificity and sensitivity for evaluation of sleep quality (86.5% and 89.6%, respectively) [

19]. The PSQI is a questionnaire offering a valid, standardized, and effective measure of sleep quality and separates good and poor sleepers". It is easy-to-understand, takes 5 to 10 minutes to respond [

20], and is being utilized in a wide range of clinical and populational studies.

The participants responded to the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) for young and middle-aged adults validated for Brazilian Portuguese [

21]. The questionnaire contains eight questions estimating the time spent during a week while walking, carrying out daily activities involving moderate or intense effort and time spent in sedentary activities [

22]. The responses were keyed in a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet and the participants were classified as active, moderately active, or sedentary.

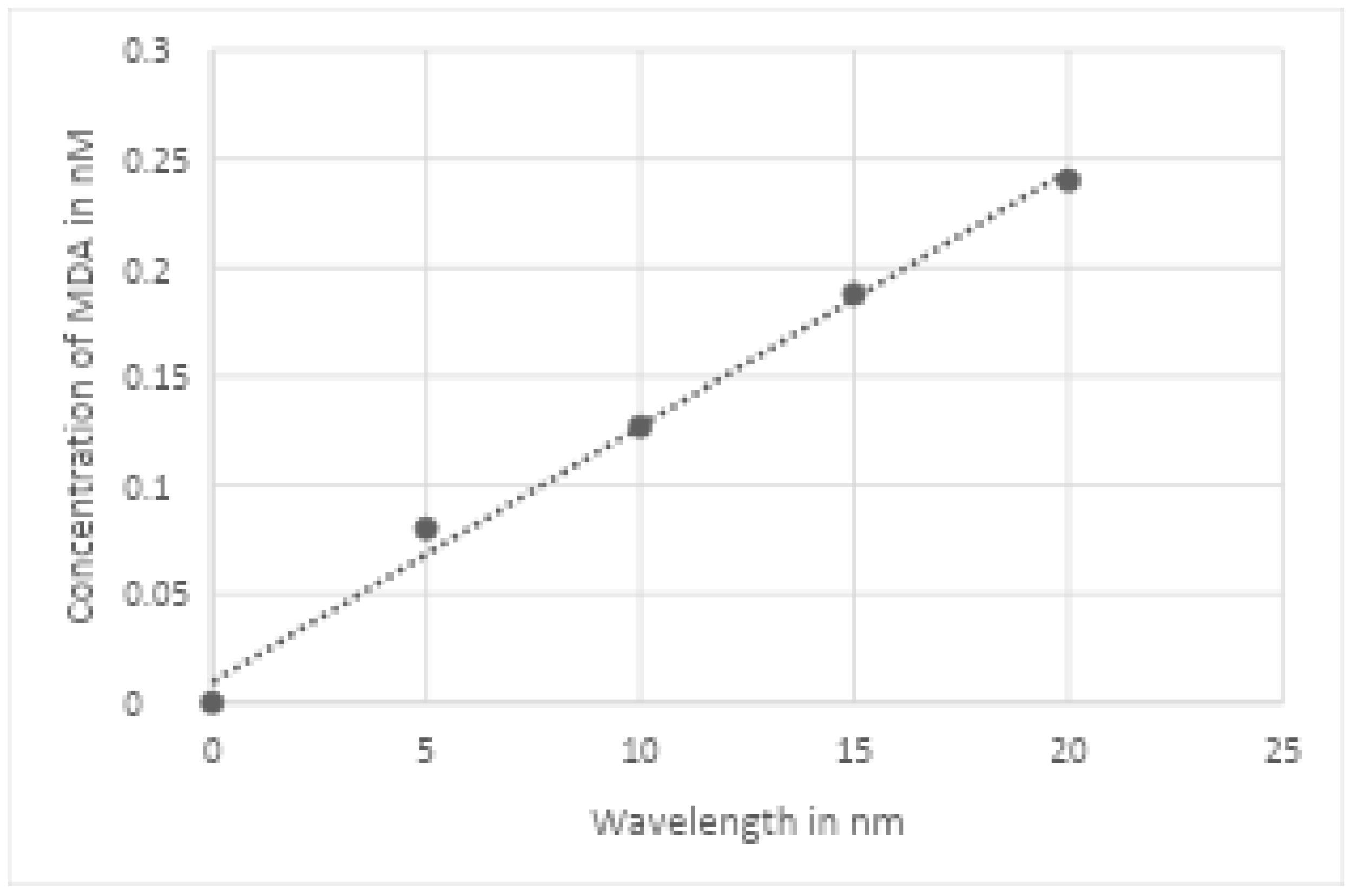

Approximately 4 mL of venous blood were collected with vacutainer and stored in blood collection tubes containing EDTA and anticoagulant. Immediately after collection, the blood was centrifuged at 2500rpm for 10 minutes to separate plasma for biochemical analysis. Serum MDA was analyzed by the reaction between MDA and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) at high temperature and low pH forming the complex MDA-TBA, pink-like color and maximum absorption at 535 nm. Measurement of lipid peroxidation was estimated by thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS). The method consisted of the precipitation of lipoproteins of the samples by adding 1% of trichloroacetic acid, 1% TBA and sodium hydroxide. The union of lipid peroxide and TBA was warmed in double-bath for 60 minutes. The chromogens formed were extracted in n-butanol and read at 535 nm in a spectrophotometer. Lipid peroxidation was expressed as nmol/ml of MDA. The calculation was made with a five-points calibration curve (0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 nM) established from an MDA solution (tetra-hydroxyprocaine) of 20 nM [

23] (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Curve of MDA standard linear regression (0, 5, 10, 25 and 20 nM) with correlation coefficient of 0.992 and regression equation of y = 0.0118x + 0.0094.

Figure 2.

Curve of MDA standard linear regression (0, 5, 10, 25 and 20 nM) with correlation coefficient of 0.992 and regression equation of y = 0.0118x + 0.0094.

After the centrifugation of the venous blood sample, erythrocytes of the plasma and other components were separated. The accurate volume of erythrocytes was obtained, utilizing a precision manual dispenser coupled to a syringe tip cautiously to avoid air bubbles. The upper erythrocytes layer was removed with pipette. 4 ml of the buffer sodium, 20μl of distilled H20 and 20 μl of the sample were added to an essay tube. Next, the entire content of the assay tube was transferred to the cuvette of the spectrophotometer and the first reading was made, registering the absorbance (T0). Soon after the reading of T0, 100 μl of the solution containing 5.5’-dithio-bis -(2-nytrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) was added to the sample, waiting three minutes for a second reading (T3).

The investigators extracted a pilot sample of seven patients for each group and calculated the mean and standard deviation of both. The paired z test was applied to estimate the sample size for a two-sample paired-meansusing standard power of 0.8 and significance level = 0.05. The same statistics were calculated for MDA and GSH and the largest sample size was chosen with 34 patients, using the GSH sample. The calculation of the power of the sample considered the difference among GSH and MDA concentrations between the groups with confidence interval of 95% and sampling error of 10%, reaching power of 100% by test t for independent samples. At the end of the study, the data were organized in Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheets. The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized to determine the distribution (normal or non- normal) of the data. Contingent upon the result, Student t test or Mann-Whitney test was adopted to compare continuous variables between the groups. Data were represented in charts and tables and analyzed through descriptive statistics (absolute and percent frequency, mean and standard deviation). Fisher’s exact test was adopted to compare nominal and categorical variables. Version 2.0 of SPSS was utilized to run the statistical tests with level of significance of 5% (p < 0.05).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study is one of the few evaluating the association between level of physical activity and oxidative stress in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Although significant results were not obtained for the evaluation of the level of physical activity by IPAQ among the groups, both were classified as physically active but with poor sleep quality by PSQI. Nevertheless, the findings reveal that only the OSAG participants presented higher levels of serum MDA, higher BMI, cervical and abdominal circumference measures versus CG. These results reaffirm the clinical profile of the patients with obstructive sleep apnea by clinical variables and the more elevated levels of MDA define it as a potential clinical marker of oxidative stress in this physically active population. More studies addressing the influence of different levels of physical activity in this population are necessary, highlighting the importance of the investigation of these variables in the promotion of health for patients with OSA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SRC. and LMTN.; methodology, SRC. and LMTN.; formal analysis, SRC.; investigation, SMC., IPF., WRAM. and GFSR; data curation, SRC. and LMTN.; writing—original draft preparation, SMC., IPF. and WRAM.; writing—review and editing, MCNP., AGOO., SRC. and LMTN; supervision SRC. and LMTN; project administration, SRC. and LMTN.; funding acquisition, SRC. and LMTN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Ordinance 466/12 of the National Health Council for studies with human beings and approved by the Institutional Review Board of “Complexo Hospitalar” of “Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA)” (4.483.804./2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author LMTN.

Acknowledgments

Not apply.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- West, S.D.; Turnbull, C. Obstructive sleep apnoea. Eye 2018, 32, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Sundar, K.M. Evaluation and Management of Adults with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Lung 2021, 199, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, B.U.; Allen, A.H.; Shah, A.; Fox, N.; Laher, I.; Almeida, F.; Jen, R.; Ayas, N. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Circulating Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress: A Cross-Sectional Study. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Offenwert, E.; Vrijsen, B.; Belge, C.; Troosters, T.; Buyse, B.; Testelmans, D. Physical activity and exercise in obstructive sleep apnea. Acta Clin. Belg. 2019, 74, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daenen, K.; Andries, A.; Mekahli, D.; Van Schepdael, A.; Jouret, F.; Bammens, B. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2018, 34, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, Q. Effects of early mobilization on the prognosis of critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 110, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniaci, A.; Iannella, G.; Cocuzza, S.; Vicini, C.; Magliulo, G.; Ferlito, S.; Cammaroto, G.; Meccariello, G.; De Vito, A.; Nicolai, A.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Biomarker Expression in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaei, R.; Safari-Faramani, R.; Hosseini, H.; Koushki, M.; Ahmadi, R.; Rostampour, M.; Khazaie, H. Increased the circulating levels of malondialdehyde in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2021, 25, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.G.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, S.T. The Effect of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on DNA Damage and Oxidative Stress. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 6, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, B.; Cunningham, R.L. Sex differences in sleep apnea and comorbid neurodegenerative diseases. Steroids 2018, 133, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, Y.G.; Cipriano, L.H.C.; Aires, R.; Zovico, P.V.C.; Campos, F.V.; de Araújo, M.T.M.; Gouvea, S.A. Oxidative stress and inflammatory profiles in obstructive sleep apnea: are short-term CPAP or aerobic exercise therapies effective? Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade, F.M.D.; Pedrosa, R.P.; Figueira, B.I.d.M.I.P.F. The role of physical exercise in obstructive sleep apnea. J. Bras. de Pneumol. 2016, 42, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasens, E.R.; Sereika, S.M.; Houze, M.P.; Strollo, P.J. Subjective and Objective Appraisal of Activity in Adults with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J. Aging Res. 2011, 2011, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelson, M.; Bailly, S.; Marillier, M.; Flore, P.; Borel, J.C.; Vivodtzev, I.; Doutreleau, S.; Verges, S.; Tamisier, R.; Pépin, J.-L. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome, Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Exercise Training Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. RESOLUÇÃO No 466, DE 12 DE DEZEMBRO DE 2012. Published online 2012. https://www.ip.usp.br/site/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/9_CNS_466_12.

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-Y.; Chen, P.-Y.; Chuang, L.-P.; Chen, N.-H.; Tu, Y.-K.; Hsieh, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Guilleminault, C. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: A bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 36, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolazi, A.N.; Fagondes, S.C.; Hoff, L.S.; Dartora, E.G.; Miozzo, I.C.d.S.; de Barba, M.E.F.; Barreto, S.S.M. Validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, P.; Spira, A.P.; Hall, B.J. Psychometric and Structural Validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index among Filipino Domestic Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João, K.A.D.R.; Becker, N.B.; Jesus, S.d.N.; Martins, R.I.S. Validation of the Portuguese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-PT). Psychiatry Res. 2017, 247, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MATSUDO, S; et al. Questionário Internacional De Atividade Física (Ipaq): Estupo De Validade E Reprodutibilidade No Brasil. Rev Bras Atividade Física Saúde. 2001;6(2):5-18. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.P.; Martinez, D.; Pedroso, M.M.; Righi, C.G.; Martins, E.F.; Silva, L.M.; Lenz, M.D.C.S.; Fiori, C.Z. Exercise, Occupational Activity, and Risk of Sleep Apnea: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precário, S. Dosagem do dialdeído malônico. Newslab. 2004;6:46-50.

- Gaines, J.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Fernandez-Mendoza, J.; Bixler, E.O. Obstructive sleep apnea and the metabolic syndrome: The road to clinically-meaningful phenotyping, improved prognosis, and personalized treatment. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 42, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrosielski, D.A.; Papandreou, C.; Patil, S.P.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Diet and exercise in the management of obstructive sleep apnoea and cardiovascular disease risk. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2017, 26, 160110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollens, B.; Reychler, G. Efficacy of exercise as a treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 41, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Maislin, D.; Keenan, B.T.; Gislason, T.; Arnardottir, E.S.; Benediktsdottir, B.; Chirinos, J.A.; Townsend, R.R.; Staley, B.; Pack, F.M.; et al. Physical Activity Following Positive Airway Pressure Treatment in Adults With and Without Obesity and With Moderate-Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, C.; Ferguson, S.; Ellis, G.; Hunter, R.F. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) for assessing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and sedentary behaviour of older adults in the United Kingdom. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mônico-Neto, M.; Antunes, H.K.M.; dos Santos, R.V.T.; D'Almeida, V.; de Souza, A.A.L.; Bittencourt, L.R.A.; Tufik, S. Physical activity as a moderator for obstructive sleep apnoea and cardiometabolic risk in the EPISONO study. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1701972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orru, G.; Storari, M.; Scano, A.; Piras, V.; Taibi, R.; Viscuso, D. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, oxidative stress, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction-An overview of predictive laboratory biomarkers. 2020, 24, 6939–6948.

- Savaş. ; Süslü, A.E.; Lay, I.; Özer, S. Assessment of the relationship between polysomnography parameters and plasma malondialdehyde levels in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 2019, 276, 3533–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekin, S.; Yildiz, H.; Alp, H.H. NOX4, MDA, IMA and oxidative DNA damage: can these parameters be used to estimate the presence and severity of OSA? Sleep Breath. 2021, 25, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvagno, F.; Vernone, A.; Pescarmona, G.P. The Role of Glutathione in Protecting against the Severe Inflammatory Response Triggered by COVID-19. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A. Glutationa: Envolvimento em defesa antioxidante, regulação de morte celular programada e destoxificação de drogas. Published online 2010. http://hdl.handle. 1028. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Rui, L.; Lv, B.; Chen, F.; Cai, L. Adiponectin Relieves Human Adult Cardiac Myocytes Injury Induced by Intermittent Hypoxia. Med Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Song, W.; Zhang, J.; Er, Y.; Xie, B.; Zhang, H.; Liao, Y.; Wang, C.; Hu, X.; Mcintyre, R.; et al. The efficacy of mind-body (Baduanjin) exercise on self-reported sleep quality and quality of life in elderly subjects with sleep disturbances: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erturk, N.; Calik-Kutukcu, E.; Arikan, H.; Savci, S.; Inal-Ince, D.; Caliskan, H.; Saglam, M.; Vardar-Yagli, N.; Firat, H.; Celik, A.; et al. The effectiveness of oropharyngeal exercises compared to inspiratory muscle training in obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. Heart Lung 2020, 49, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Characterization of the groups.

Table 1.

Characterization of the groups.

| Variable |

OSAG (n=15) |

CG (n=22) |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

| Female |

8 (53.3) |

16 (72.7) |

| Male |

7 (46.7) |

6 (27.3) |

| Age, mean ± SD |

54.87 ± 12.70 |

47.32 ± 12.61 |

| BMI (Kg∕m²), n (%) * |

(n=13) |

(n=20) |

| Normal |

1 (7.69) |

6 (30) |

| Overweight |

4 (30.77) |

10 (50) |

| Obese |

7 (53.85) |

1 (5) |

| Extreme Obese |

1 (7.69) |

1 (5) |

| Education, n (%) |

|

|

| ≤8 years |

7 (46.7) |

0 |

| >8 years |

8 (53.3) |

22 (100) |

| Marital status, n (%) |

|

|

| With spouse |

7 (46.7) |

8 (36.4) |

| No spouse |

8 (53.3) |

14 (63.6) |

| Non-communicable chronic disease, n (%)** |

|

|

| Yes |

11 (73.3) |

12 (54.5) |

| No |

4 (26.7) |

10 (45.5) |

| Alcohol use, n (%) |

|

|

| Yes |

5 (33.33) |

11 (50) |

| No |

10 (66.7) |

11 (20) |

| Measures of circumference (cm), mean ± SD |

|

|

| Cervical |

39.67±3.52 |

36.27 ± 3.74 |

| Abdominal |

105.4 ± 11.09 |

94.45 ± 11.96 |

Table 2.

Results of the levels of serum MDA, GSH and IPAQ score.

Table 2.

Results of the levels of serum MDA, GSH and IPAQ score.

| Groups |

N |

OSAG

(mean ± DP) |

N |

CG

(mean ± DP) |

| MDA (nmol∕mL) |

14 |

5.18 ± 1.33 |

20 |

1.18 ± 0.92 |

| GSH (μmol/g Hb) |

15 |

125.99 ± 28.18 |

22 |

118.44 ± 16.52 |

| IPAQ (MET-min∕week) |

12 |

3170 ± 1936 |

21 |

2907 ± 2411 |

Table 3.

Classification of the level of physical activity according to IPAQ criteria. OSA Group (n=12), Control Group (n=17).

Table 3.

Classification of the level of physical activity according to IPAQ criteria. OSA Group (n=12), Control Group (n=17).

| |

Classification IPAQ, n (%) |

|

| |

OSA Group (n=15) |

Control Group (n=22) |

| Active |

9 (60%) |

9 (40.9%) |

| Moderately active |

3 (20%) |

10 (45.4%) |

Table 4.

Quality of sleep evaluated by the PSQI.

Table 4.

Quality of sleep evaluated by the PSQI.

| Variable |

OSA Group (n=15) n (%) |

CG (n=22) n (%) |

| PSQI Categories |

|

|

| Good quality of sleep (<5 points) |

2 (13.4) |

9 (41) |

| Poor quality of sleep (<5 points) |

13 (86.6) |

13 (59) |

Table 5.

Variables associated with Obstructive Sleep Apnea related to MDA.

Table 5.

Variables associated with Obstructive Sleep Apnea related to MDA.

| |

|

|

IC 95% |

| MDA |

Coefficient |

Value of p

|

LL |

UL |

| Pittsburgh |

0.0748 |

0.463 |

-0.1311 |

0.2808 |

| Circunference Cervical |

0.0905 |

0.271 |

-0.0745 |

0.2556 |

| Bedtime |

0.0423 |

0.172 |

-0.0195 |

0.1042 |

| Sleep quality |

-1.7436 |

0.014 |

-3.1007 |

-0.3865 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).