1. Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasm (NENs) represents a group of tumors which have their origin in neuroendocrine cells, with a variable biologic behavior and wide heterogeneity [1, 2, 3]. They can develop in any organ, having a predilection for the pancreas, lungs and digestive tract [1] [4]. According to World Health Organization Classification, 2017 and 2019 editions, NENs can be classified into well-differentiated G1,G2 and G3 neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs) or poorly differentiated G3 tumors (pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas-pNECs), with the mention that all pNETs have malignant potential [1] [5] [4].

pNETs were first described in 1869 as a distinct tumor with distinct biological behavior from pancreatic adenocarcinomas [1]. pNETs can secrete different types of hormones, depending on this characteristic they are being classified into functional tumors and non-functional tumors [1, 6]. Patients with functional pNETs are symptomatic in a proportion of up to 90%, the symptomatology being given by the hormonal hypersecretion of the tumor (insulin, serotonin, gastrin, glucagon, vasoactive intestinal peptides, somatostatin) [1, 6] [4].

The surgical resection is the only curative treatment for patients with pNETs (localized tumors), with a 5-years survival more than 90%, while for advanced tumors or metastatic disease, systemic therapy with somatostatin analogs and chemotherapy is recommended. [1, 7, 8, 9]. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 50% of cases have metastatic disease, and 20% with locally advanced tumors [10]. Surgical resections are indicated specially for functioning pNETs,regardless of tumor size, to control hormone hypersecretion, or when there are local compressive symptoms, and for non-functioning pNETs greater than 2 cm [11, 12, 3]. For patients with unresectable tumors, survival at 5 years varies between 15-27% [7].

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are associated with an increased incidence of pancreatic fistulas after pancreatic resections [13, 14]. Pancreatic fistula is the most frequent and severe postoperative complication, after pancreatic resections, with an important impact on the quality of life, and an increased risk of bleeding, abscess, sepsis, and multiple organ failure [11, 12].

2. Material and Methods

Our retrospective study includes a selection of cases over a period of 10 years, with pancreatic resections for neuroendocrine tumors. Initially, patients with pancreatic resections and enucleation were selected, then the histological reports were analyzed and only patients confirmed with neuroendocrine tumors were included in the study. Preoperatively, all patients were evaluated paraclinical and imaging (abdominal ultrasound, computer tomography), thus establishing the diagnosis of pancreatic tumor. No preoperative tumor biopsies were performed. The diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor was established histologically, after performing immunohistochemical staining that were positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin A and the Ki67 mitotic index. In this study we aimed to follow the postoperative complications and the identification of risk factors, but also the prognostic factors for postoperative survival.

The diagnosis of pancreatic fistula was established according to the ISGPF classification (International study group for pancreatic fistula), when there was a persistence of drainage and an increase in amylase values in the liquid on the drain tube.

The database included general information (age, gender), information related to the type of surgical intervention, histology and tumor staging, dynamics of some biological factors (proteins, hemoglobin, liver balance), postoperative evolution, postoperative complications, comorbidities, survival.

The SPSS program was used for statistical analysis, and the statistical association was considered at a p-value lower than 0.05. Continuous variables were reported as mean with standard deviation. Comparisons between the analyzed groups were performed using the t-Student test, ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis, or Mann–Whitney U Test for continuous variables. The homogeneity of the series was verified regarding the statistical differences between the variances of the series by the Levene test (Levene Test of Homogeneity of Variances). The correlations between certain parameters were tested using the Pearson test, by evaluating the correlation coefficient r. Qualitative variables were presented as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies, and comparisons between groups were made based on the results of non-parametric M-L, Yates, or Pearson Chi-square tests. The power of univariate prediction of risk factors was assessed using the ROC curve based on the value of the area under the curve (Area Under the Curve: AUC).

3. Results

The study performed is a retrospective study, which included a group of 26 patients, consisting of 16 women and 10 men, aged between 31 and 81 years, with a median of 55 years.

The size of the tumor varied between 9 mm and 65 mm, with a median of 20 mm, and peak in the range of 10-15 mm, according to the histogram in

Figure 1.

From the point of view of hormonal secretion, 7 patients were with functional pNETs and 19 with non-functional ones. Among the patients with functional pNETs, 5 were with insulinomas, and 2 patients with gastrinomas, all patients presenting symptoms specific to hormonal hypersecretion. Both patients diagnosed with gastrinomas also had associated MEN1 syndrome. The association of MEN1 syndrome was also identified in a case with non-functional pNET.

In our study group, the incidence of pNEC was 26.92% (7 cases). In 2 cases, pNEC was identified in patients with functional pNETs (one case with insulinoma-like neuroendocrine carcinoma, and one case with gastrinoma associated with MEN1, that developed postoperative distant metastases), the rest being in the group of patients with nonfunctional pNETs. One case was with MANEC tumor type (mixed adeno-neuroendocrine carcinoma).

Also, there were cases of pNETs that were associated with other primary malignant tumors. One of the patients, 7 years after the enucleation of an insulinoma, was diagnosed with locally advanced ovarian tumor with invasion of the rectosigmoid, ureter and bladder, with peritoneal carcinomatosis, and the tumor biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma with a hight mitotic index. Another case was a tumor collision between a gastrinoma and pancreatic acinar carcinoma. A case was with multicentric pNEC for which total duodenopancreatectomy was performed, developed an invasive ductal breast carcinoma one year after pancreatic surgery and a bronchopulmonary cancer after 3 years.

As the type of surgical intervention, distal pancreatectomies (with or without preservation of the spleen) prevailed in 12 cases (46.15%), followed by cephalic duodenopancreatectomies in 8 cases (30.77%). Enucleations were also performed in 5 cases, and total duodenopancreatectomy in one case.

In one case, it was performed in the same operative time the duodenopancreatectomy and the resection of liver metastasis, for a young patient of 31 years old.

The incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula was 28%, after the case of total duodenopancreatectomy was excluded from the statistical analysis. The highest incidence of POPF was observed in the group of patients with duodenopancreatectomy (50%), respectively enucleation (40%), and the lowest, in the group of patients with distal pancreatectomy (8.3%). (

Table 1)

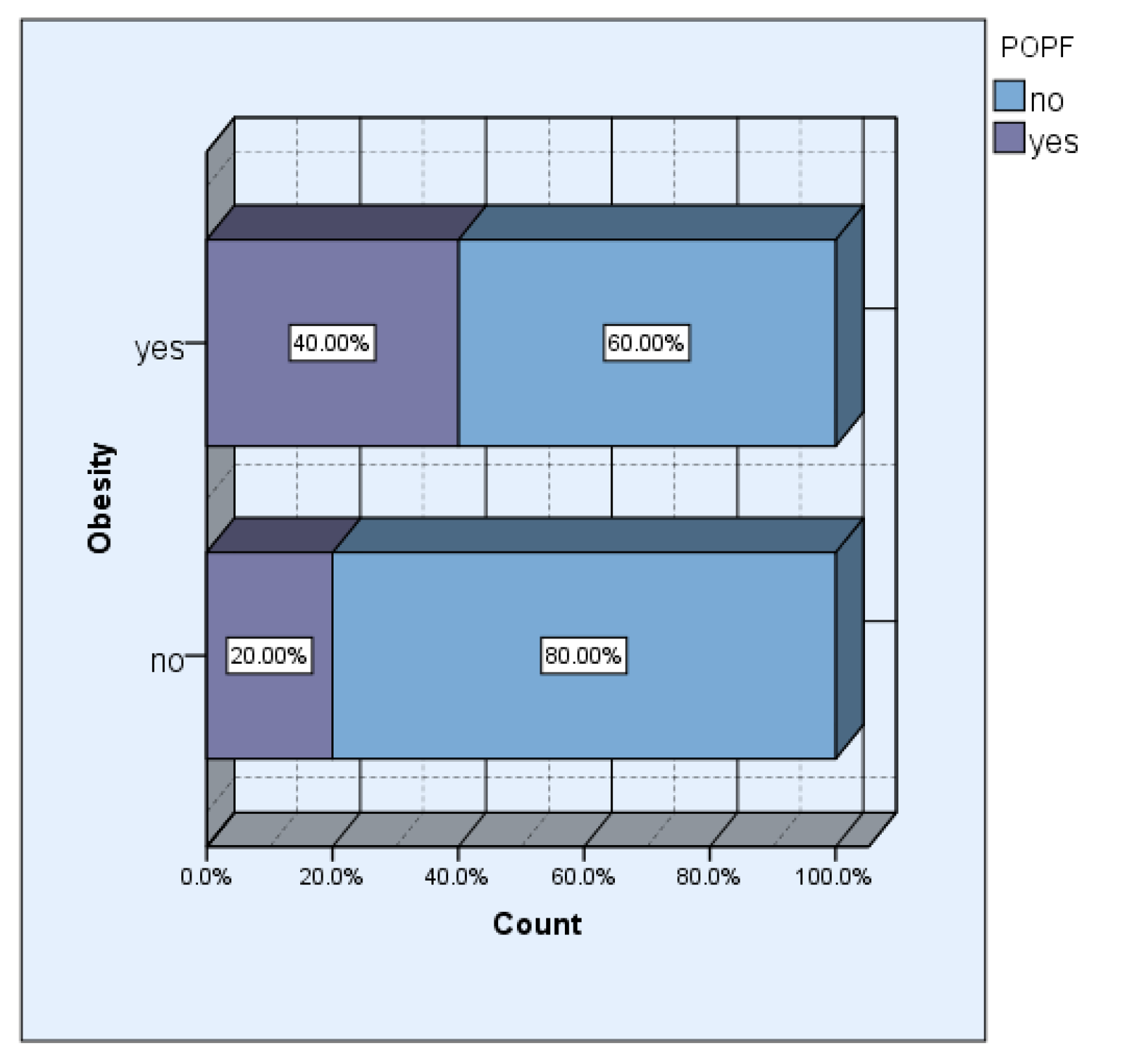

The incidence of obesity in our study group was 42.31% (11 cases). Although we did not obtain a significant statistical association, 57.1% of the patients who developed pancreatic fistula postoperatively had different degrees of obesity.

In the group of obese patients, the incidence of pancreatic fistula was double, respectively 40% versus 20% in the group of non-obese patients.

Figure 2.

Obesity vs POPF.

Figure 2.

Obesity vs POPF.

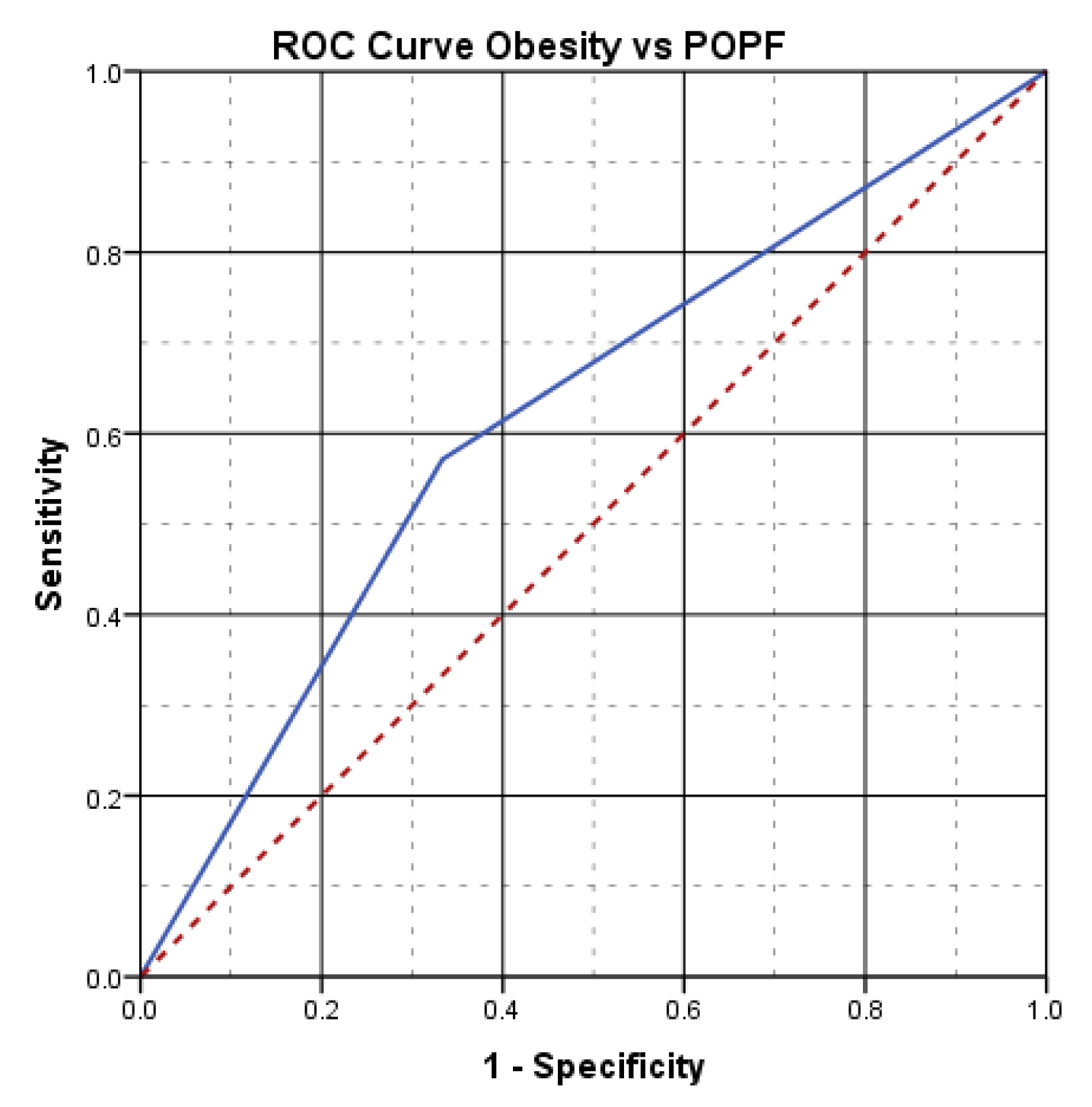

The aspect of the ROC curve (

Figure 3) and the calculated value under the curve of AUC=.619, reveal the fact that the presence of obesity has a good power of prediction on the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula.

In our study group, we found no statistically significant association between tumor size and the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula (p=.384), with a median of 20mm in the group with pancreatic fistula vs 22mm in the group without pancreatic fistula. However, 57.1% of patients who developed postoperative pancreatic fistula were in the group of patients with tumors smaller than 2 cm. The association between the development of POPF and tumors under 2 cm can be correlated with the fact that enucleation was chosen for small tumors, if the conditions for this technique were met.

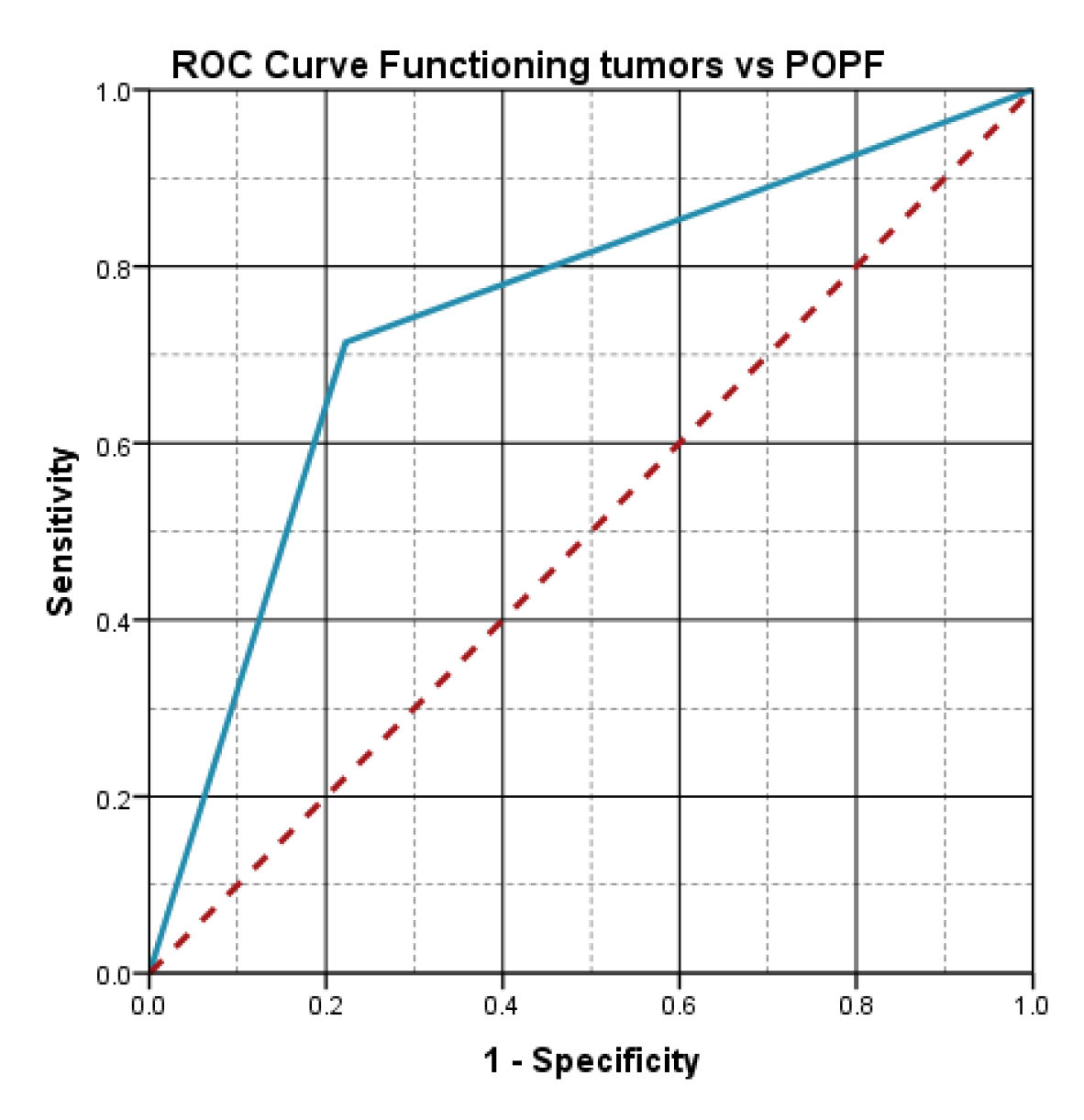

The statistical analysis showed an important statistical association between the functioning character of the tumor and the risk of pancreatic fistula (p=.032), the incidence of pancreatic fistula being 71.4% in the group of functioning tumors.

The aspect of the ROC curve (

Figure 4) and the calculated value of AUC=.746, reveal the fact that the functioning character of the tumor has a high predictive power on the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula.

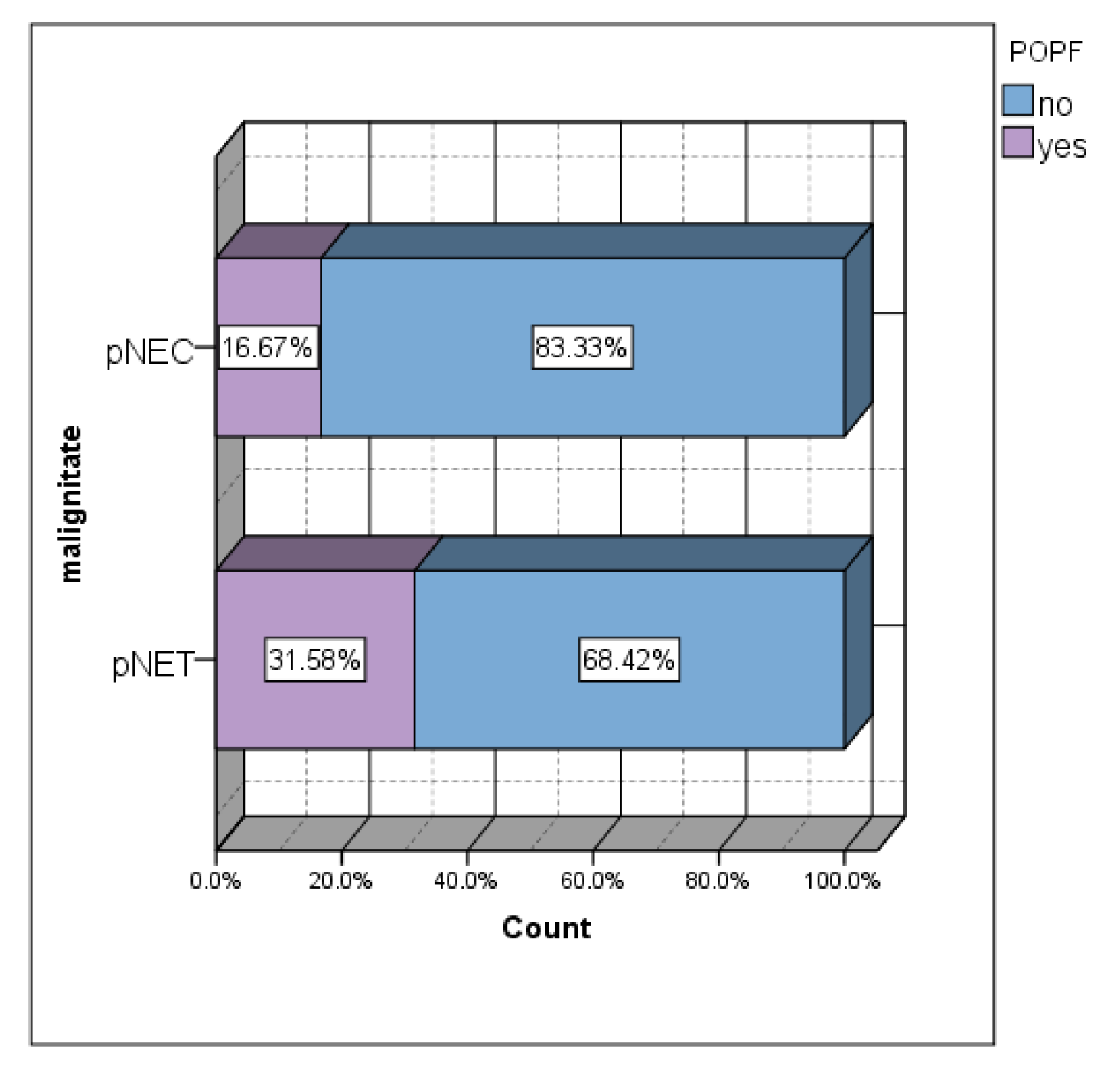

Although a statistically significant association was not obtained, the lowest incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistulas was in the group of patients with malignant tumors (14.3%) (

Figure 5). Approximately 1/3 of pNET patients developed POPF (

Figure 5). The incidence of POPF in the group of patients with pNETs was almost double that in the group of patients with pNEC.

Of all pNEC patients, 1/3 presented tumors with a diameter smaller than 2 cm, this aspect calling into question the "watch and wait" recommendation for small tumors.

71% of the cases of tumors with malignant behavior presented positive lymph nodes, and of these, 66% had tumors smaller than 2.2 cm in size.

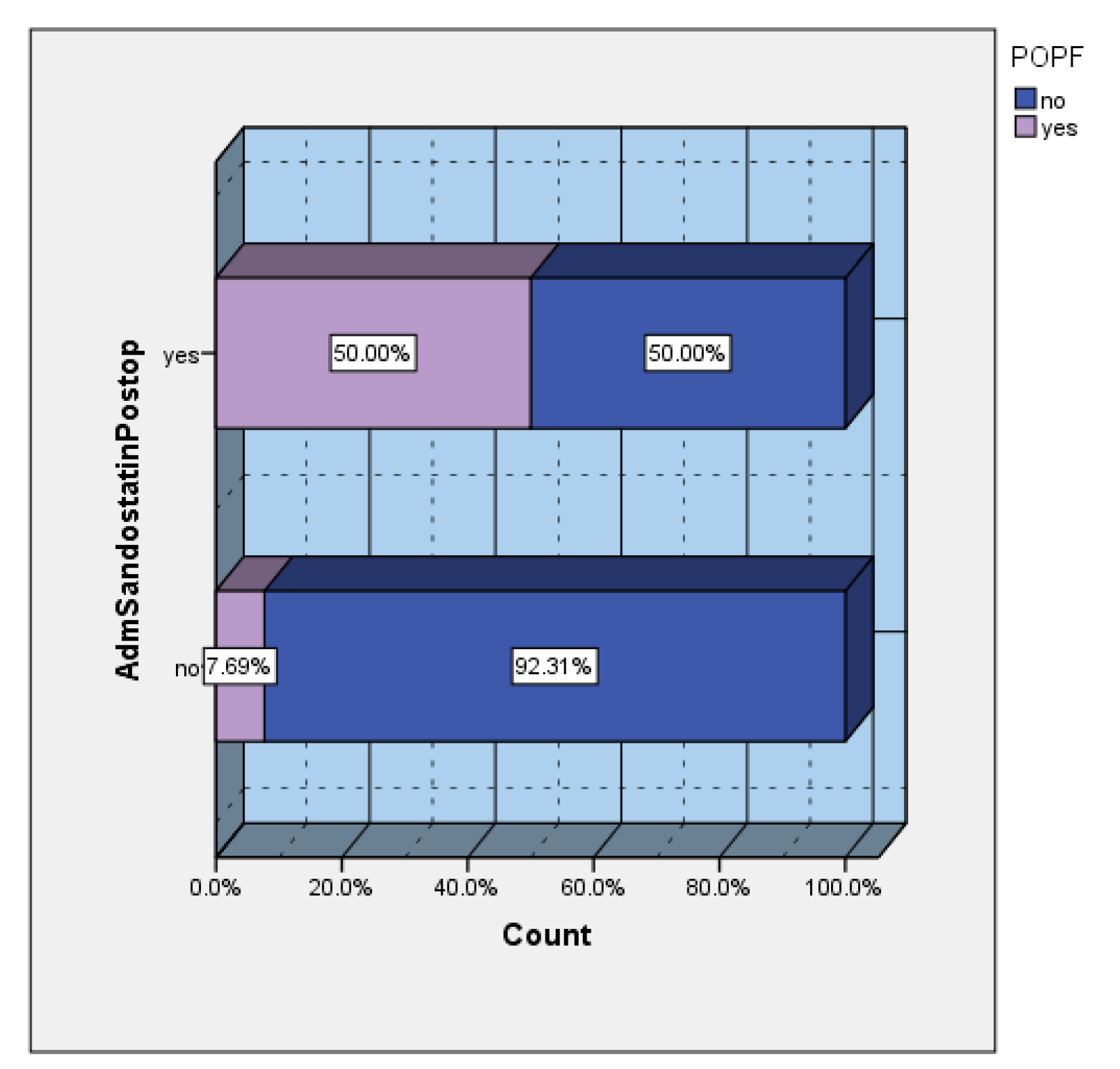

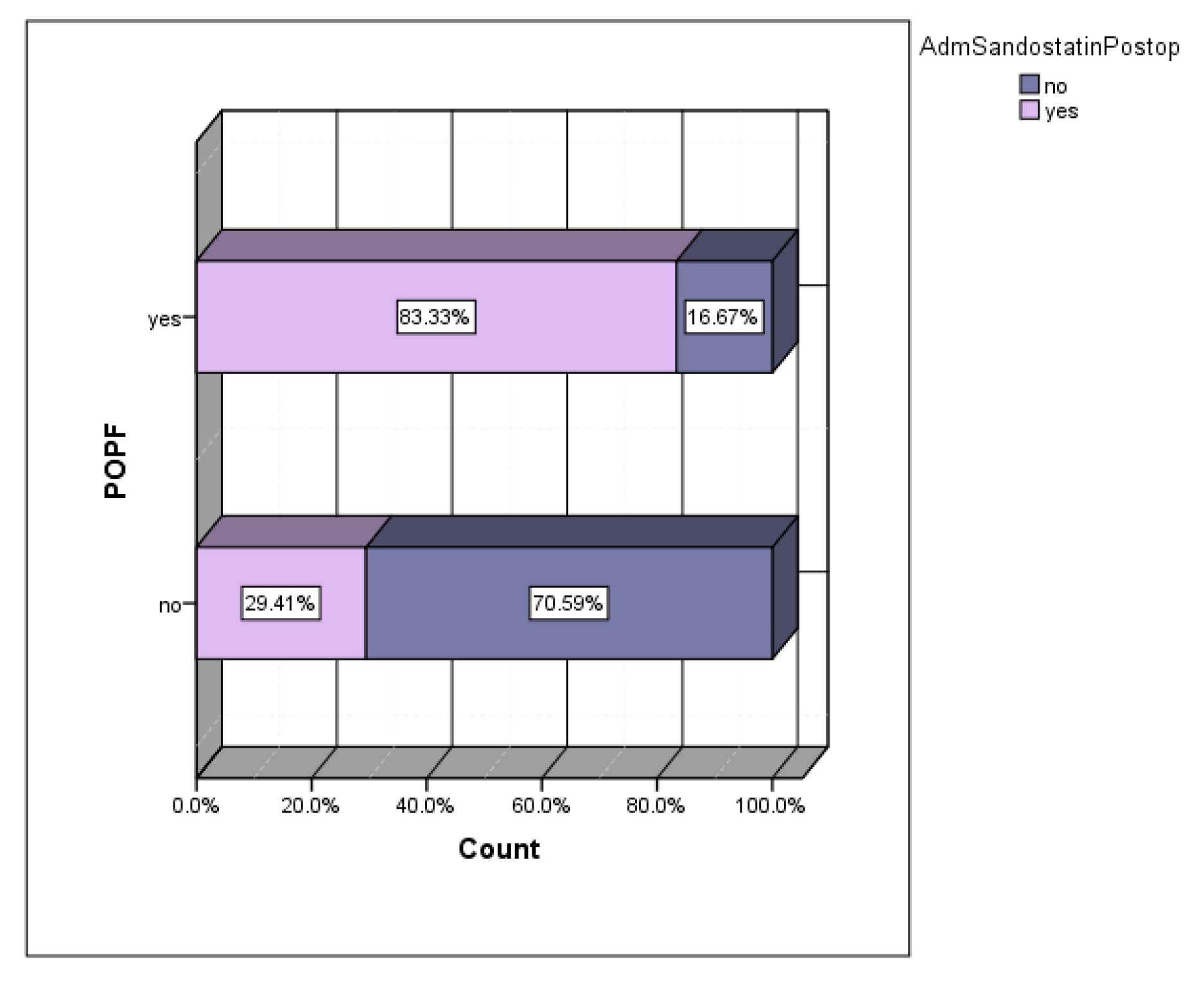

Depending on the preferences of the main operator, a series of patients received prophylactic somatostatin in the postoperative period. The incidence of POPF in the group of patients who received prophylactic sandostatin was 50%, versus 7.69% in the group of patients without prophylactic sandostatin (

Figure 6). Of the total number of patients who developed postoperative POPF, 83.33% were cases that received prophylactic sandostatin (

Figure 7).

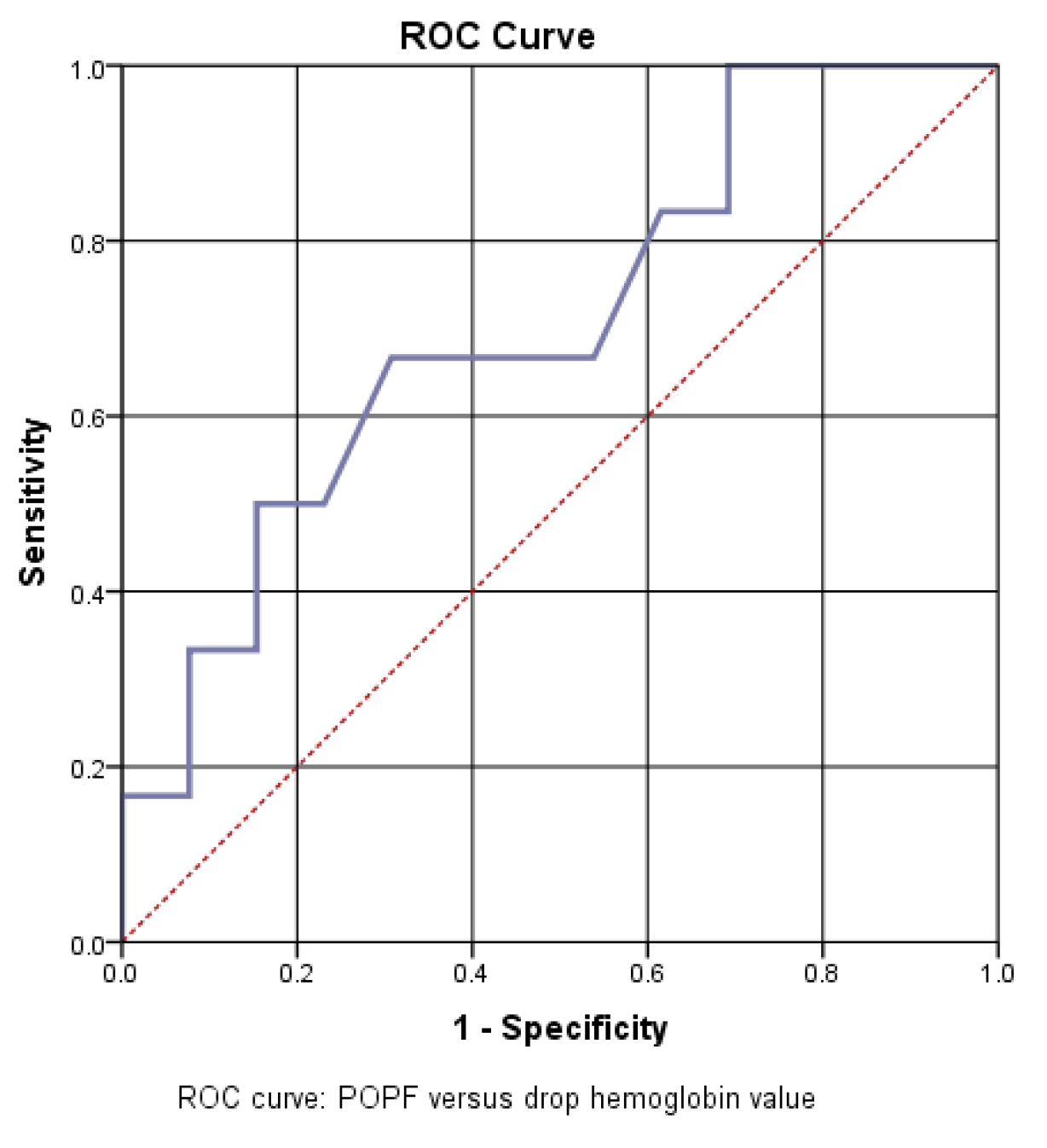

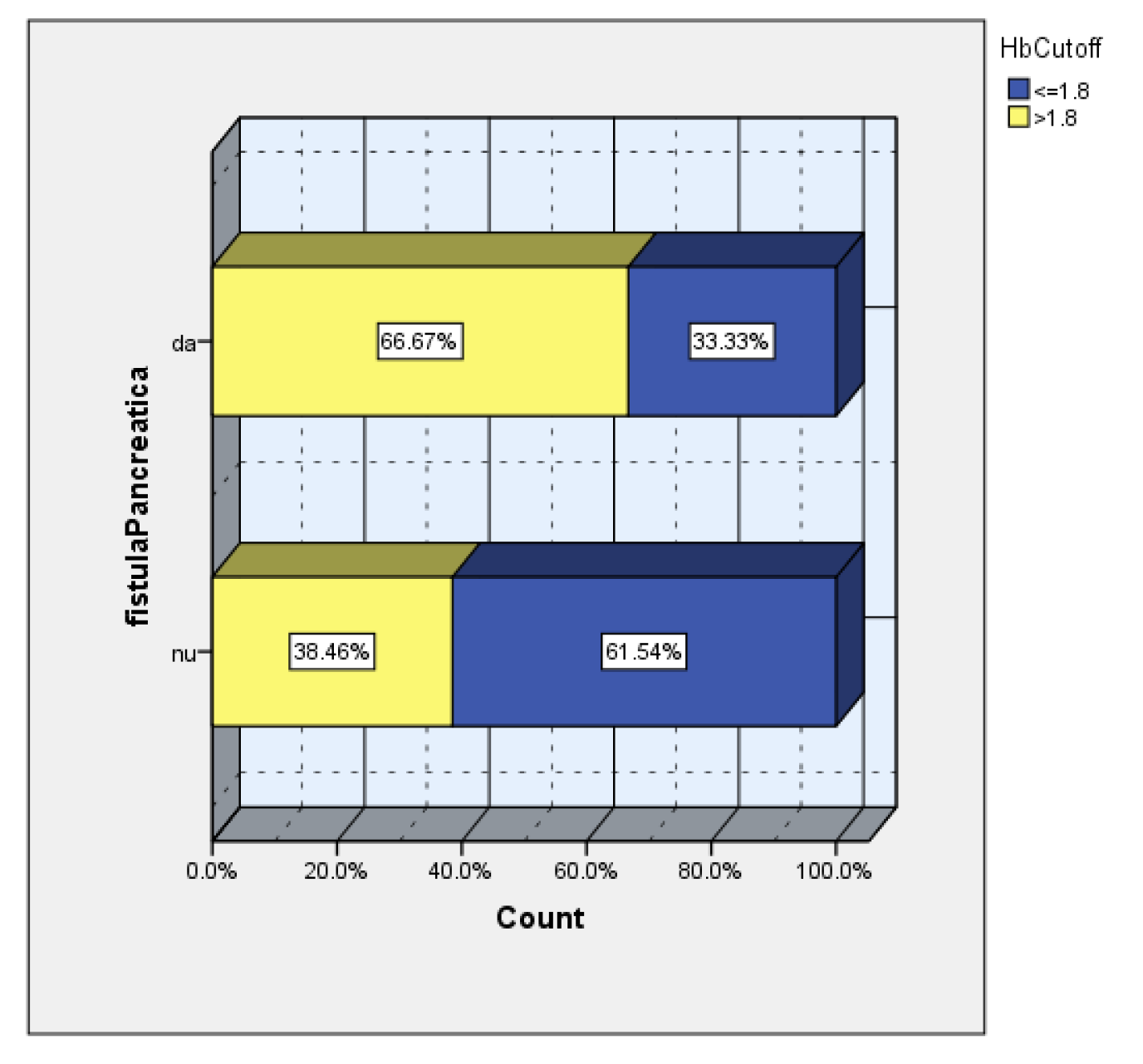

Another analyzed factor was the dynamic value of hemoglobin. In our study group, neither the preoperative hemoglobin value nor the hemoglobin value on the first postoperative day were correlated with an increase in the risk of pancreatic fistula. But the dynamic analysis of hemoglobin was identified as an important predictive factor, so a good statistical correlation was obtained between the decrease in hemoglobin from the first operative day compared to the initial value and the increase in the incidence of pancreatic fistula.

The AUC=705 value confirms a good predictive power of drop hemoglobin value on the risk of pancreatic fistula. Thus, a cut off value of 1.8 was calculated, with a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 37% (

Figure 8).

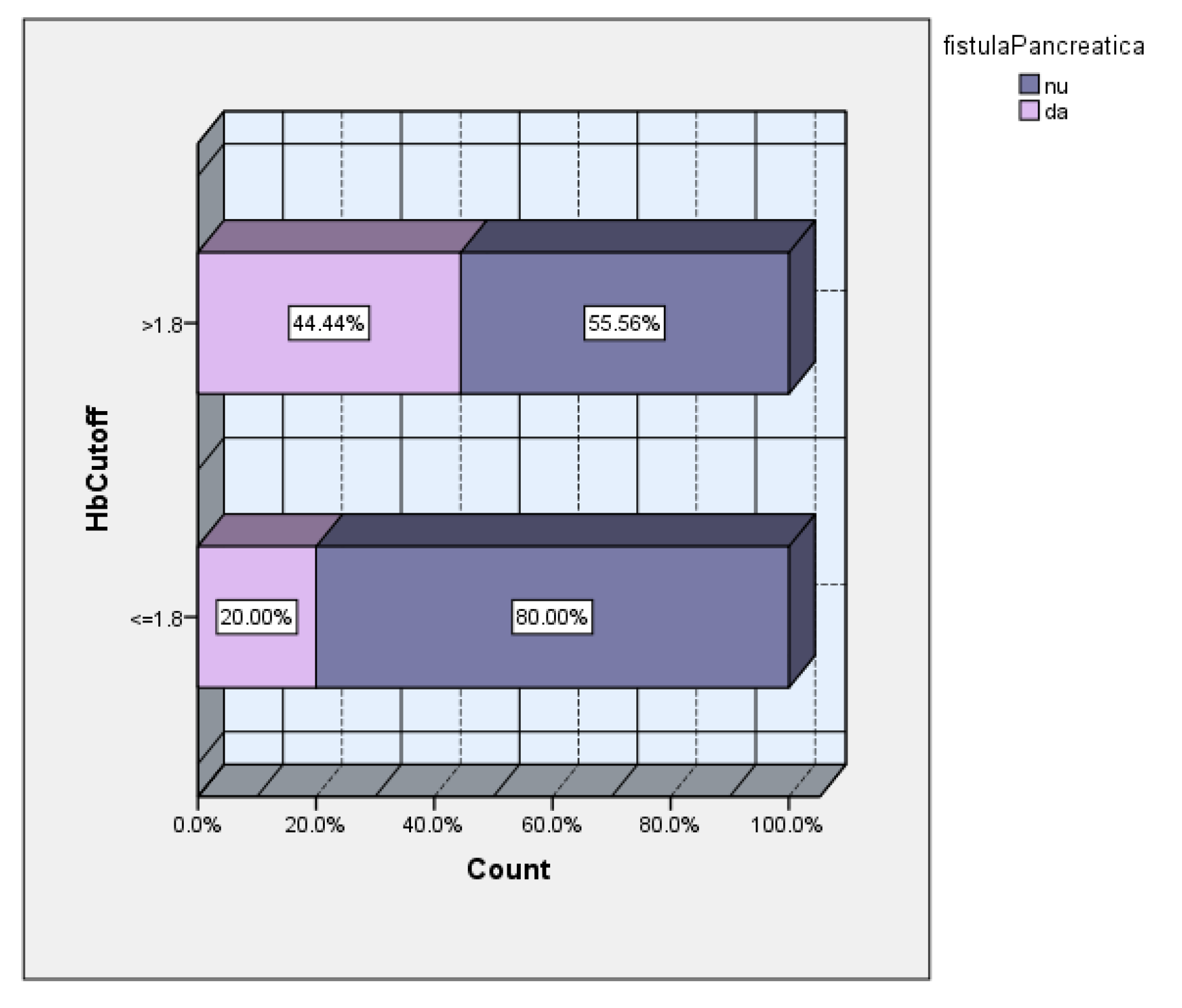

The subsequent analysis according to the cutoff value of the hemoglobin drop showed a 2.2 times higher incidence of POPF in the group of patients with hemoglobin drop>1.8 (

Figure 9).

Also, 2/3 of the patients with POPF had a hemoglobin drop greater than the calculated cutoff value (

Figure 10).

The 2-year survival rate of the group was 80.77%, with only one case of in-hospital death. Postoperative survival varied between 13 months and 102 months, with a median of 47.24 months.

4. Discussions

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are rare tumors, derived from pancreatic neuroendocrine cells, representing about 3-5% of all pancreatic tumors [2, 15, 16]. They are the second most common epithelial malignancy of the pancreas [17].

The immunohistochemical profile is essential for establishing the diagnosis of pNETs, this being confirmed by the presence of synaptophysin, chromogranin A (CgA) and Ki67 expressions [4]. Chromogranin A is a glycoprotein secreted by neurons and neuroendocrine cells, therefore it represents a diagnostic marker, but at the same time serum CgA is an important marker in postoperative monitoring for non-functional pNETs, being secreted by 60-100% of non-functioning pNETs [1, 7] . CgA is considered an independent prognostic factor for survival and recurrent pNETs [1, 7]. The disadvantage of CgA is that it can be false positive in chronic gastritis, inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis, renal or liver failure, other malignancies ( thyroid and prostate cancer) or different therapies (proton pomps inhibitors, somatostatin analogues or steroids) [1, 7, 17]. All patients included in our study were monitored postoperatively by the endocrinomolgy service, dynamic dosages of chromogranin were performed (elevated values were suggestive of postoperative distant metastases). .

The Ki67 mitotic index is an important marker both for prognosis and for establishing the therapeutic strategy [4]. The pNETs G3 with Ki67>20% have a poorly median survival (54.1 months) than pNETs G1 (Ki67<2%) and G2 (Ki67<20%) with a median survival of 67.8 months [16].

To differentiate a G3 pNETs from a pNEC, staining for p53 and RB1 is required [4].

A new concept was introduced that defines a mixed neoplasm that includes both a neuroendocrine component and a non-neuroendocrine component - MANEC (mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas) [1].

Insulinomas are the most frecquent functioning pNETs and generally the tumor size is under 2 cm and have a benign behavior, unlike the other functional pNETs that have a malignant behavior. [4]. In our study there was a case with insulinoma-like neuroendocrine carcinoma, which had a remission of hypoglycemia episodes in the postoperative period, was monitored and 6 years postoperatively developed distant metastases. Malignant insulinomas are rare tumors accounting for approximately 20% of all insulinomas. In most cases, the patient becomes symptomatic after the development of liver metastases, when there are enough insulin-secreting cells to trigger the hypoglycemic syndrome [4].

Approximately 30% of pNETs are gastrinomas, which due to the excess of secreted gastrin, cause peptic ulcers (sdr Zollinger-Ellison) [17]. Gastrinomas can have multiple locations, often pancreatic ones being associated with duodenal gastrinomas [17]. When gastrinoma is associated with MEN1, there is extremely rarely a single lesion, generally there are multiple pancreatic or gastrointestinal locations [7]. One of our patients included in the study had also, gastrinomas with multiple locations: pancreas, duodenum and stomach.

Up to 10% of pNETs can be associated with other genetic syndromes (most frequently with MEN1) or other multiple primary malignancies (MPM) [4, 2, 17] [9]. Surgical treatment is recommended for patients with MEN1 associated with functional pNETs, but contraindicated when MEN1 is associated with non-functional pNETs [17]. pNEC are rare, solitary tumors and are not associated with genetic syndromes [4]. Over 80% of patients with MEN1 are associated with pNETs, and surgical treatment is required to prevent malignant progression, when the endocrine syndrome is refractory to treatment, for tumors larger than 2 cm or showing fast growth. [18]

Gastrinomas are malignant in proportion of 60-90%, and the presence of metastases represents the most reliable predictive factor on long-term survival [7]. Considering the high rate of nodal metastases, the recommended surgical treatment in the case of gastrinomas is represented by pancreatic resections associated with regional lymphodissection [7]. Intraoperatively, it is mandatory to carefully explore the adjacent organs, so that other extrapancreatic gastrinomas can be identified [7]. For this purpose, digital palpation, intraoperative ultrasound, duodenotomy or endoscopy with transillumination can be performed [7].

Generally, non-functional pNETs are diagnosed when they reach large sizes [9, 17]. This aspect can be debatable between the hypothesis that non-functional tumors have a fast growth rate or the lack of symptoms leads to a late diagnosis.

While Wang et col. showed that lymph node status alone was not a significant predictor of survival in univariate and multivariate analysis [5], other studies concluded that lymph node metastasis is an important prognosis factor [2]. In addition, NCCN guidelines recommend lymph node dissection for all functional pNTEts, regardless of tumor size [2].

The occurence of postoperative complications is also a prognostic factor, the most common complication being pancreatic fistulas, which are associated with multiple comorbidities and have an important impact on postoperative evolution and survival [11, 14]. Despite the high rate of postoperative complications, surgical treatment remains the only treatment with curative potential both for tumors with malignant behavior and for the control of hormonal hypersecretion [11].

There are studies that show that in neuroendocrine tumors there is no desmoplastic stroma (which is well represented in pancreatic adenocarcinomas) or fibrosis, this desmoplastic stroma being a protective factor for the appearance of pancreatic fistulas [14, 6]. Also, Hedges et col. observed in their study, an increased incidence of POPF in the group of patients with pNETs, compared to the non-pNETs group, thus supporting the importance of the histological type as a risk factor for the development of POPF [12].

For the entire study group, the incidence of pancreatic fistula was 28%, but an increased incidence was observed especially after pancreaticoduodenectomy and enucleation (50% respectively 40%). Inchauste et all, in a study that included 122 patients with pNETs, observed an increase in the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula in patients with enucleation versus pancreatic resections [11]. The same study identifies obesity as an important risk factor for postoperative pancreatic fistulas, especially for cases with pancreatic resections, not for enucleation [11].

In our study, an incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula was also identified double in the group of obese patients compared to the group of non-obese patients

The presence of obesity predisposes to complications postoperative such as hemorrhages, wall infections abdominal, anastomotic fistulas, with direct effects on the increase in hospitalization days and costs hospital. The association of obesity with pancreatic steatosis and large intraoperative blood losses represent an important risk of the occurence of pancreatic fistulas, in especially of those of type C, which can be responsible for up to to 41% of all postoperative deaths [19, 13, 6].

There are studies which determined that visceral fat is a more accurate predictor of postoperative pancreatic fistula than body mass index, for cases of pancreatic resections [13, 6]. For enucleation cases, the most important risk factor for the occurrence of POPF is the location of the tumor in the proximity of the pancreatic duct (at a distance of less than 2 mm), in these cases the anatomical conditions do not allow limiting the occurrence of pancreatic fistula [13].

Generally, enucleation is indicated for tumors smaller than 2 cm or for peripherally located insulinomas [7]. The criteria that guide the enucleation option refer to the size of the tumor, non-malignant lesion and proximity to the pancreatic ducts [20]. The advantages of enucleation are reduced intraoperative blood loss, shorter operating times and better preservation of pancreatic tissue [20, 6]. Even if a higher incidence of pancreatic fistula was observed after enucleation, these were less severe than after pancreatic resections [20]. In our study, the incidence of pancreatic fistula was much higher (by 40%) in the group of patients with enucleation, according to other studies. Atema et col, in their study obtained a strong correlation between the type of surgical intervention and the risk of POPF, with an increased incidence especially after enucleation or central pancreatectomy [6].

For small tumors with low malignancy potential, enucleation remains a viable and safe option, studies showing long-term survival comparable to pancreatic resections [20].

Another important factor in the occurrence of POPF is the intraoperative blood loss, considering that a loss more than 1000ml is associated with a very high risk [14]. In our study group, we observed a strong statistical association between the decrease of hemoglobin in dynamics, on the first postoperative day compared to the preoperative value of hemoglobin. Statistical analysis showed that a drop in hemoglobin greater than 1.8 mg/dl was associated with a doubling of the incidence of POPF. This aspect leads to the conclusion that the body compensates less for a rapid decrease in hemoglobin. The factors that can lead to a decrease in hemoglobin can be: intraoperative blood loss, administration of large amounts of fluids intraoperatively or in the preoperatively period. In this study, we observed that patients tolerated well a progressive decrease in hemoglobin (low hemoglobin values at admission did not represent a risk factor for POPF), in contrast to the decrease in hemoglobin immediately postoperatively, with which a strong association was obtained statistics. Molasy et al, observed in their study, a 5 times higher incidence of POPF in the group of patients who had an intraoperative blood loss greater than 700ml [14].

For tumors larger than 2 cm, surgical treatment is unanimously accepted, regardless of the tumor stage and grade, due to the risk of distant metastases [21]. But a topic that still incites debate is the indicated treatment in non-secreting tumors smaller than 2 cm. Pitt et al draw attention to the fact that the risk of malignancy is also present in the case of small tumors, in their study, 4% of patients with tumors smaller than 3 cm, without metastases and negative nodes, presented recurrence in the postoperative period [20]. Also, in our study, one third of the patients with pNEC had tumor size smaller than 2 cm, which supports the indication of surgical treatment even for small tumors, at the detriment of surveillance and monitoring. Studies performed on cases of small pNETs, obtained significantly higher 5-year survival in cases with pancreatic resections versus non-surgical ones [2].

Opting for surgical treatment must also consider the rate of postoperative complications, so that ENETs Guidelines ( European Neuroendocrine Tumors Society) recommend surgical treatment for small lesions, when they show a growth rate greater than 0.5 cm over a period of 6-12 months [7]. However, Partelli et al, in their study highlighted the fact that half of the patients with nodal metastases could not be imagistic visualized preoperatively [10].

There are studies that have shown that up to 26% of non-functional pNETs between 1-2 cm in size have positive lymph nodes, and those under 1 cm have positive lymph nodes in proportion to 12% [7, 2]. in our study, 66% of the patients with lymph node metastases were cases with tumors smaller than 2.2 cm. In this context, the question arises whether enucleation is an option for non-functional, small pNETS, in conditions where lymph dissection cannot be performed. Lymph node metastasis is an important factor, both for staging (their positivity classifying pNETs in stage III), but they are also used as a postoperative prognostic factor [2].

For patients with liver metastases at the time of diagnosis, surgical treatment is indicated if two conditions can be met: the affected liver tissue is below 50% of the total volume and it is possible to resect at least 90% of the tumoral tissue [9, 1]. Even if the recurrence rate for these patients is high, it has been observed that in the long term an increase in survival is obtained [9, 1]. In one of the cases of our study, with liver metastasis at the time of diagnosis, a duodenopancreatectomy operation associated with the resection of the liver metastasis was performed at the same time, in a 31-year-old patient, with a good postoperative survival (he is still being monitored , after 43 months postoperatively).

Contrary to these results, the guidelines of the NANETS (North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society) do not mention surgical treatment as an option for metastatic pNEC [15]. On the other hand, the resection of the primary tumor can improve the prognosis in metastatic pNETs , and a longer survival [15, 2].

5. Conclusions

Neuroendocrine tumors are a group of heterogeneous tumors, with a varied histological and immunohistochemical profile. These tumors show a predisposition for the occurence of postoperative complications, especially postoperative pancreatic fistulas. Several additional factors, such as the type of surgical intervention, obesity, administered medication and dynamic variation of hemoglobin are factors that increase the risk of postoperative complications.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

The study is retrospective and patients agreed to be included inclinical trials and research.

Data Availability Statement

The data published in this research are available on request from thefirst and last author and corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not declare any conflict of interest. The authors state that they are not in conflict of financial or non-financial interests with the data and information presented in the article.

References

- Ma ZY, Gong YF, Zhuang HK, Zhou ZX, Huang SZ, Zou YP, Huang BW, Sun ZH, Zhang CZ, Tang YQ, Hou BH. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A review of serum biomarkers, staging, and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2020 May 21;26(19):2305-2322. PMID: 32476795; PMCID: PMC7243647. [CrossRef]

- Mei W, Cao F, Lu J, Qu C, Fang Z, Li J, Li F. Characteristics of small pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and risk factors for invasion and metastasis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 20;14:1140873. PMID: 37020595; PMCID: PMC10067566. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Chin W, Pan C, Zhang W, Yu J, Zheng S, Liu Y. Risk of malignancy and prognosis of sporadic resected small (≤2 cm) nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gland Surg. 2021 Jan;10(1):219-232. PMID: 33633978; PMCID: PMC7882341. [CrossRef]

- Konukiewitz B, Jesinghaus M, Kasajima A, Klöppel G. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the pancreas: diagnosis and pitfalls. Virchows Arch. 2022 Feb;480(2):247-257. Epub 2021 Oct 13. PMID: 34647171; PMCID: PMC8986719. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Lin Z, Li G, Zhang D, Yu D, Lin Q, Wang J, Zhao Y, Pi G, Zhang T. Validation and modification of staging Systems for Poorly Differentiated Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020 Mar 6;20(1):188. PMID: 32138704; PMCID: PMC7059325. [CrossRef]

- Atema JJ, Jilesen AP, Busch OR, van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ, Nieveen van Dijkum EJ. Pancreatic fistulae after pancreatic resections for neuroendocrine tumours compared with resections for other lesions. HPB (Oxford). 2015 Jan;17(1):38-45. Epub 2014 Jul 18. PMID: 25041879; PMCID: PMC4266439. [CrossRef]

- Johnston ME 2nd, Carter MM, Wilson GC, Ahmad SA, Patel SH. Surgical management of primary pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020 Jun;11(3):578-589. PMID: 32655937; PMCID: PMC7340810. [CrossRef]

- Kaur J, Vijayvergia N. Narrative Review of Immunotherapy in Gastroentero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Curr Oncol. 2023 Sep 21;30(9):8653-8664. PMID: 37754542; PMCID: PMC10527684. [CrossRef]

- Dumlu EG, Karakoç D, Özdemir A. Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Advances in Diagnosis, Management, and Controversies. Int Surg. 2015 Jun;100(6):1089-97. Epub 2015 Jan 15. PMID: 25590518; PMCID: PMC4587512. [CrossRef]

- Marx M, Caillol F, Godat S, Poizat F, Oumrani S, Ratone JP, Hoibian S, Dahel Y, Oziel-Taieb S, Niccoli P, Ewald J, Mitry E, Giovannini M. Outcome of nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors after initial surveillance or surgical resection: a single-center observational study. Ann Gastroenterol. 2023 Nov-Dec;36(6):686-693. Epub 2023 Oct 30. PMID: 38023974; PMCID: PMC10662066. [CrossRef]

- Inchauste SM, Lanier BJ, Libutti SK, Phan GQ, Nilubol N, Steinberg SM, Kebebew E, Hughes MS. Rate of clinically significant postoperative pancreatic fistula in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. World J Surg. 2012 Jul;36(7):1517-26. PMID: 22526042; PMCID: PMC3521612. [CrossRef]

- Hedges EA, Khan TM, Babic B, Nilubol N. Predictors of post-operative pancreatic fistula formation in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A national surgical quality improvement program analysis. Am J Surg. 2022 Nov;224(5):1256-1261. Epub 2022 Aug 10. PMID: 35999087; PMCID: PMC9700260. [CrossRef]

- Assadipour Y, Azoury SC, Schaub NN, Hong Y, Eil R, Inchauste SM, Steinberg SM, Venkatesan AM, Libutti SK, Hughes MS. Significance of preoperative radiographic pancreatic density in predicting pancreatic fistula after surgery for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Surg. 2016 Jul;212(1):40-6. Epub 2015 Dec 12. PMID: 26782807; PMCID: PMC7480190. [CrossRef]

- Molasy B, Zemła P, Mrowiec S, Kusnierz K. Utility of fistula risk score in assessing the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula occurrence and other significant complications after different types of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor resections. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2022 Dec;103(6):340-349. Epub 2022 Dec 8. PMID: 36601342; PMCID: PMC9763781. [CrossRef]

- Feng T, Lv W, Yuan M, Shi Z, Zhong H, Ling S. Surgical resection of the primary tumor leads to prolonged survival in metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2019 Mar 21;17(1):54. PMID: 30898132; PMCID: PMC6429809. [CrossRef]

- Yan J, Yu S, Jia C, Li M, Chen J. Molecular subtyping in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: New insights into clinical, pathological unmet needs and challenges. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020 Aug;1874(1):188367. Epub 2020 Apr 25. PMID: 32339609. [CrossRef]

- Mpilla GB, Philip PA, El-Rayes B, Azmi AS. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Therapeutic challenges and research limitations. World J Gastroenterol. 2020 Jul 28;26(28):4036-4054. PMID: 32821069; PMCID: PMC7403797. [CrossRef]

- Tonelli F, Marini F, Giusti F, Iantomasi T, Giudici F, Brandi ML. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors in MEN1 Patients: Difference in Post-Operative Complications and Tumor Progression between Major and Minimal Pancreatic Surgeries. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Oct 10;15(20):4919. PMID: 37894286; PMCID: PMC10605506. [CrossRef]

- Denbo JW, Orr WS, Zarzaur BL, Behrman SW. Toward defining grade C pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, risk factors, management and outcome. HPB (Oxford). 2012 Sep;14(9):589-93. Epub 2012 May 28. PMID: 22882195; PMCID: PMC3461384. [CrossRef]

- Pitt SC, Pitt HA, Baker MS, Christians K, Touzios JG, Kiely JM, Weber SM, Wilson SD, Howard TJ, Talamonti MS, Rikkers LF. Small pancreatic and periampullary neuroendocrine tumors: resect or enucleate? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009 Sep;13(9):1692-8. Epub 2009 Jun 23. PMID: 19548038; PMCID: PMC3354713. [CrossRef]

- Møller S, Langer SW, Slott C, Krogh J, Hansen CP, Kjaer A, Holmager P, Klose M, Garbyal RS, Knigge U, Andreassen M. Recurrence-Free Survival and Disease-Specific Survival in Patients with Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Single-Center Retrospective Study of 413 Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Dec 24;16(1):100. PMID: 38201527; PMCID: PMC10777990. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).