1. Introduction

Greenhouse gases and global warming are a critical issue around the world. According to the IPCC (Intergovenmental Panel on Climate Change) report, the temperature of the earth has risen about 1°C compared to the pre-industrial period and recommends strongly that it should not rise more than 1.5°C [

1]. Carbon dioxide, a main cause of global warming, has risen substantially since the pre-industrial period, from 285 to 419 ppm between 1850 and 2022 [

2,

3]. By 2050, carbon emission is projected to increase by approximately 50% [

4], which will accelerate global warming by raising the temperatures of both the global surface and oceans [

5]. The IPCC report employs a carbon budget approach to correlate cumulative CO

2 emissions with global temperature increase, suggesting that a remaining budget of approximately 420 GtCO

2 is necessary to have a two-thirds chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C, while around 580 GtCO

2 is required for an equal probability. If the remaining carbon budget is set at 580 GtCO

2, it indicates that CO

2 emissions must achieve carbon neutrality within roughly 30 years, which is reduced to 20 years with a budget of 420 GtCO

2. This underscores the necessity of achieving carbon neutrality within a maximum timeframe of 30 years, regardless of the circumstances [

6]. Achieving carbon neutrality means that an entity—such as an individual, organization, or country—balances its greenhouse gas emissions by reducing or eliminating them and compensating for any remaining emissions through the purchase of carbon credits associated with projects that mitigate or temporarily capture these emissions [

7].

The concentration of greenhouse gases has also been a critical issue in South Korea, with net emissions reaching 656.2 CO

2eq in 2020, which is more than twice the emissions recorded in 1990 [

8]. With the increase in greenhouse gas emission, the average annual temperature of South Korea has also risen from 12.6°C in 1990s to 13.0°C in 2011~2017 [

7]. Since the mid-2010s, the frequency and intensity of high temperature in spring in Korea have increased significantly [

9]. Gyeonggi Province, South Korea is known as the most carbon-emitting local government according to the 2018 national statistics. Calculations of final energy consumption in 2018 indicate that Gyeonggi Province has the highest carbon emission rate in the nation, accounting for 17.9% of South Korea’s total greenhouse gas emissions [

10]. This has raised a critical necessity of more aggressive measures in urban planning and policies in order to achieve national carbon neutrality.

The study seeks to evaluate the carbon-neutral strategies embedded within the comprehensive urban plans of twelve cities in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. To achieve this, assessment indicators have been developed based on an extensive literature review and an expert survey. These indicators are utilized to evaluate the quality of plans concerning carbon neutrality. It is anticipated that this study will contribute to the development of robust methodological frameworks for assessing carbon-neutral strategies in urban planning processes. This study is meaningful as it not only evaluates the effectiveness of existing plans by establishing a framework for assessing the development of practical strategies to reach carbon neutrality goals but also serves as a guideline for formulating future comprehensive urban plans.

2. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. Urban Planning for Carbon Neutrality

Cities consume over two-thirds of the world’s energy and produce 70% of global CO2 emission, most of which come from industrial and motorized transport systems that use huge amount of fossil fuel [

11]. According to the World Bank, in order to meet the 1.5°C goal set by the IPCC, massive decarbonization in cities must be achieved, necessitating investment in low-carbon energy for transport systems, programs to reduce urban sprawl, and nature-based solutions for urban cooling and disaster risk management [

12]. Cities are significant entities in responding to climate change for several reasons: 1) they consume a substantial amount of energy and produce waste; 2) they are directly engaged with local issues and attempt to translate the global rhetoric of sustainable development into local practice; 3) they possess considerable experience in energy management, transport, and planning; and 4) they strive to develop innovative measures and strategies to better address climate change [

13].

Therefore, planning a city is regarded as a critical measure to effectively reduce carbon emissions. Among others, key areas in planning to achieve a carbon-neutral city are suggested as follows [

14]: greenery planning, land use and spatial structure planning, transportation planning, energy planning, water circulation planning, and waste treatment planning. All these areas are associated closely with carbon emission and absorption, and conservation of natural resources and sustainable energy usage [

14]. Kim et al. developed a set of evaluation indicators for carbon-neutral green city by reviewing a wide range of studies, government guidelines, and green building certification systems [

15]. Kang et al. analyzed comprehensively the studies in low-carbon green city planning, and derived the key five planning elements for achieving low-carbon city: environmental-friendly land use, green transportation system, energy efficiency, resource circulation, and conservation of ecological system [

16]. For the applications of the planning elements, the study suggested the following strategies: high-density and mixed-use development, enhancement of access to public transits, bicycle and pedestrian-friendly route systems, increase of renewable energy, plan for high-efficiency building and facilities, waste reduction and recycling system, low-carbon water supply and decentralized rainwater management, creation of neighborhood parks and green spaces, creation of wind paths along with tree plantings [

16].

2.2. Urban Planning for Carbon Neutrality in South Korea

A comprehensive urban plan is legally required for the local governments in South Korea. Each local government with a population exceeding 200,000 is required to establish a comprehensive urban plan covering a 20-year period and update it every 5 years. Central government of South Korea provided a revised guideline for the local governments in 2021 to establish comprehensive urban plan, in which greenhouse gas emissions and absorption status need to be added to the basic survey items, and greenhouse gas reduction goals and implementation strategies need to be reflected in a various phases and elements of the planning. The key revisions of the guideline in 2021 include a requirement that the principles of a plan must reflect the goals and directions toward carbon neutrality, including greenhouse gas emissions and absorption status in the basic survey items. The revision also mandates incorporating greenhouse gas reduction goals into planning objectives every five years. Furthermore, the revised guideline requires the integration of carbon neutrality planning elements into sector-specific plans such as urban spatial structure, land use plans, infrastructure, residential environments, and parks and green areas [

17].

Meanwhile, in the ’Republic of Korea’s 2050 Carbon Neutrality Strategy’ announced by the central government, sector-specific strategies have been presented for energy supply, industry, transportation, buildings, waste management, agriculture, forestry, and carbon sinks, all aimed at achieving carbon neutrality. The majority of greenhouse gas emissions in the industrial sector stem from energy consumption, emphasizing the government’s recognition of the crucial importance of transitioning innovatively from energy-intensive industries heavily reliant on fossil fuels to a low-carbon regime. Consequently, the government has put forth a range of measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including the adoption of cutting-edge technologies, enhancement of energy efficiency, expansion of the use of low-carbon fuels, and reduction of emissions of greenhouse gases from industrial sectors [

18].

2.3. Indicators of carbon neutrality in urban plans

Despite the significance of cities in achieving carbon neutrality, cities face numerous barriers in accelerating carbon reduction efforts. The crucial matter at hand is the lack of well-defined carbon neutrality indicators that align with the circumstances of nations and municipalities, coupled with a deficiency in the execution and systematic monitoring [

19].

Ting and Zhenghong developed indicators to assess how well carbon reduction principles are reflected in local comprehensive land-use plans for the fastest-growing cities in the United States [

20]. Based on the five milestones presented by International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives to mitigate climate crisis, the study developed 35 indicators categorized by 5 plan components to assess carbon neutrality of the comprehensive land-use plans (

Table 1) [

20].

The indicators that Ting and Zhenghong suggested encompass various areas, including carbon absorption sources, land use, low-carbon transportation infrastructure, energy consumption, citizen participation, and a monitoring plan for operational stage. Oh et al. categorized the urban planning components for carbon reduction into land use, mobility, energy, and resource circulation. However, Oh et al. did not develop specific indicators related to carbon neutrality, such as carbon absorption sources and green infrastructure, and Ting and Zhenghong did not consider weights for stages and components of plans for cities in different contexts.

Based on a critical review of the previous studies (

Table 2), the study derived 6 planning components and 27 indicators for evaluating plan qualities in carbon-neutrality. The planning components are: 1) factual basis, 2) goals and objectives, 3) governance, 4) spatial and transportation plans, 5) energy management strategies, and 6) implementation and monitoring. Factual basis includes 5 indicators: 1) population change and impact, 2) land development and impact, 3) an inventory of existing resources and energy usage, 4) impacts and vulnerability of climate change, 5) recognition of greenhouse gas emission. Goals and objective include 4 indicators: 1) carbon emission reduction target, 2) promotion of compact or multicenter urban forms, 3) energy conservation and efficiency, and 4) support of climate change vulnerable group. Governance consists of 3 indicators: 1) citizen participation initiatives, 2) coordination with other institutions, and 3) policy measures for climate change disasters. Spatial and transportation plans include 6 indicators: 1) expansion of parks and green areas, 2) improvement of park and green networks, 3) protection and restoration of urban and forest ecosystems, 4) green infrastructure system and low impact development, 5) mixed-use development, and 6) green transportation system. Energy management strategies include 7 indicators: 1) improvement of industrial technology and production system for carbon reduction, 2) facilitation of local renewable sources, 3) funding and incentives for energy efficiency and conservation, 4) establishment of cap and trade system / carbon tax / carbon point system, 5) zero-waste / high recycling strategies, and 6) building codes for energy efficiency. Finally, implementation and monitoring include 3 indicators: 1) Continuous monitoring, evaluation and update, 2) financial/budget plan based on investment priority, and 3) public participation programs.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Urban Planning for Carbon Neutrality

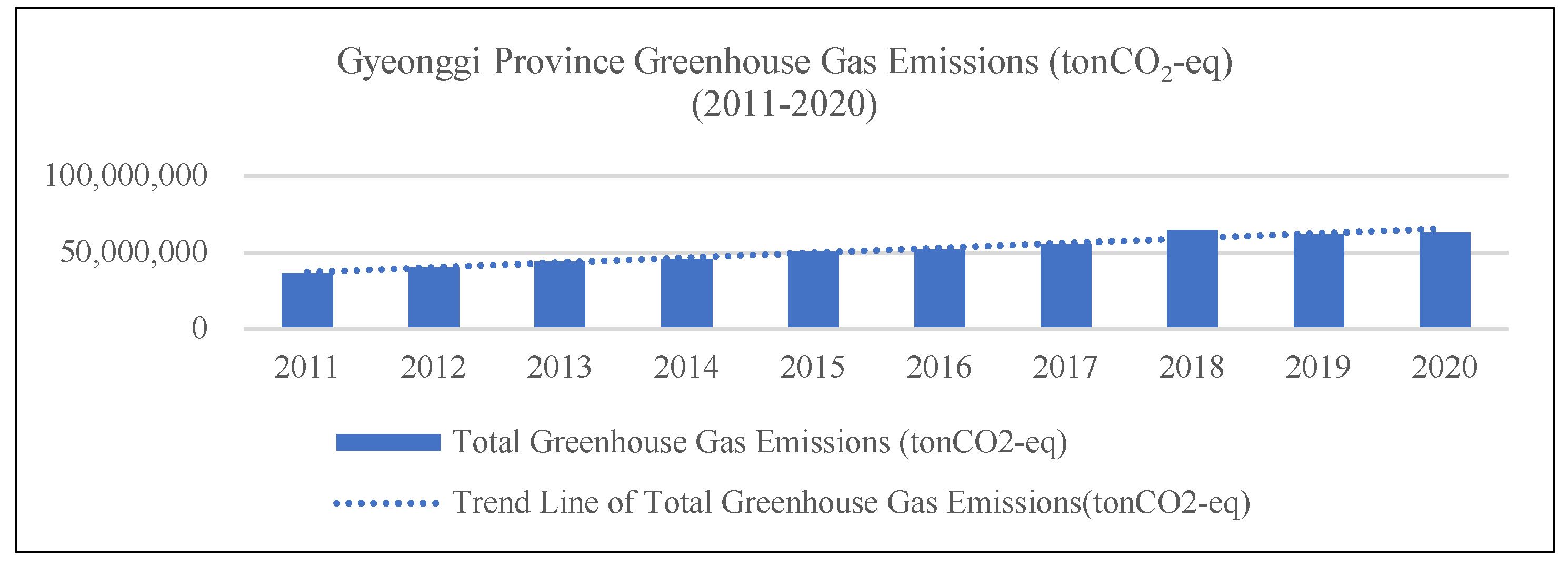

At the 17th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP17), South Korea was designated as a country with obligations for greenhouse gas reduction. In response, the South Korean government declared its commitment to carbon neutrality in 2020. By 2021, all 243 local governments in South Korea had made similar carbon neutrality declarations. Among these, 31 local governments are situated in Gyeonggi Province, which, as of 2024, accounts for approximately 26% of the national population. Also, Gyeonggi Province stands out among South Korea’s local governments for its high greenhouse gas emissions and significant rate of increase. According to data published on the public data portal operated by Gyeonggi Province, while the average annual increase rate of greenhouse gas emissions for 17 provinces across the country was 1% from 2011 to 2020, Gyeonggi Province showed a much higher rate of approximately 6% (

Figure 1) [

21]. Also, the greenhouse gas emissions in Gyeonggi Province are significantly high across various sectors, with industry contributing 38%, transportation (road) 19.5%, and residential, commercial, and public sectors 36.2%. Thus, it is determined that achieving carbon neutrality cannot be accomplished by reducing emissions in just one sector alone [

22].

Gyeonggi Province, which has high greenhouse gas emissions, faces significant development pressure and has a substantial proportion of manufacturing. Therefore, transitioning urban infrastructure and industry to low-carbon alternatives is crucial. It is essential to approach greenhouse gas reduction not only from an environmental perspective but also from an integrated viewpoint that considers the overall industry, employment, and quality of life in the region. For this reason, it is essential that carbon neutrality objectives be incorporated from the initial stages of comprehensive urban plan. In response, the South Korean government enacted a partial revision of the “2011 Guidelines for the Establishment of Comprehensive Urban Plan” to ensure the integration of carbon neutrality considerations into comprehensive urban plan. Consequently, local governments have formulated their comprehensive urban plans in accordance with these revised guidelines.

However, without a thorough understanding of the regional context of carbon neutrality and its social, economic, and environmental impacts and implications, there is a risk that planning efforts will be limited to declarative goals and formalized plans. This concern highlights the need for a well-prepared approach to planning to avoid superficial efforts [

10].

Therefore, this study selected cities within Gyeonggi Province based on the criteria of having published or revised their comprehensive urban plans within the past five years, with January 2022 as the evaluation point. The evaluation focused on municipalities that had announced or revised their plans between June 2017 and January 2022, which are Anyang city, Guri city, Gwangmyeong city, Hwaseong city, Icheon city, Osan city, Paju city, Seongnam city, Uijeongbu city, Uiwang city, Yangju city, Yongin city.

3.2. Expert Survey

Plan components and indicators for the assessment of carbon neutrality depend on the socio-cultural contexts in which urban plans are established and implemented. Thus an AHP survey was conducted among experts to determine the weights of indicators for assessing the carbon neutrality of comprehensive urban plans. The experts in the fields of urban and environmental planning were sampled through snowball sampling. The survey, administered via email to 20 experts, included questions designed to evaluate the relative importance of plan components and indicators through pairwise comparisons. This process utilized Saaty’s discrete 9-value scale method to assess the relative importance among components at Level 1 and the relative importance among indicators at Level 2 [

23]. The AHP was composed of two levels. Level 1 consists of six plan components: basic information, goal establishment, governance, spatial and transport plan, energy management plan, and implementation and monitoring. Level 2 consists of 27 indicators under the six plan components.

3.3. Evaluation of Plans

Using the plan components and indicators of carbon neutrality, the comprehensive urban plans of the twelve cities in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea, were evaluated. The evaluation for each indicator was conducted using a 0-2 scale, with a total possible score of 2 points. A score of 0 was assigned if no information regarding the indicator was presented in the plan, a score of 1 was given if a brief description was provided without detailed information, and a score of 2 was provided if the indicator was presented with detailed information, such as tables, graphs, maps, or policies. For instance, a plan that provides information only on the current carbon emission status receives 1 point, while a plan that includes information on the causes and predictions of carbon emissions, in addition to the emission status, receives 2 points.

Although the overall assessment framework applies generally, specific criteria vary for each component due to unique characteristics that must be considered. As relevant content that is absent is uniformly assigned a score of zero, this discussion will describe the distinctions between scores of one and two.

The "Factual Basis" component evaluates how well the plans understand factors that may influence carbon emissions and absorption for plan development. Accordingly, the score is categorized as follows: a score of 1 is given if the plan provides data regarding the region’s status from the past up to the present, whereas a score of 2 is awarded when the plan not only presents current data but also forecasts future changes based on this information.

The "Goals and Objectives" component concerns the specificity with which a region sets its targets to achieve carbon neutrality. A score of 1 is assigned if goals are presented in a numerical or general manner. Conversely, a score of 2 is given when goals are articulated in detailed phases or coupled with specific strategies.

The "Governance" component focuses on establishment of networks by various stakeholders to address issues related to carbon neutrality or climate change in plan formulation and execution. A score of 1 is given for general strategy proposals, while a score of 2 is awarded if strategies are developed reflecting the local context.

The "Spatial and Transportation Plans" component assesses whether urban space and transportation plans are strategically formulated to achieve regional carbon neutrality objectives. General and broad proposals, such as increasing green space or establishing networks, receive a score of 1, whereas specific implementation plans with particular target areas or numerical details receive a score of 2.

"Energy Management Strategies" evaluate the effectiveness of strategies for energy efficiency improvement. A general description of plans, for instance, increasing the share of renewable energy, receives a score of 1. A score of 2 is assigned when plans provide a detailed execution strategy that reflects the regional analysis and characteristics.

The "Implementation and Monitoring" component assesses the thoroughness of plans concerning the elements required for the implementation of previously established plans. A score of 1 is given if the plans provide general direction at a theoretical level, while a score of 2 is attributed when detailed execution plans are presented.

3.4. AHP Analysis and Weight Standardization

Based on the results obtained from the expert survey, the geometric mean is utilized to calculate the relative importance, or weights, of the hierarchical elements. It is essential to assess the consistency of the evaluators, which involves identifying any logical contradictions in their judgments. This is done by calculating the Consistency Ratio (CR) by dividing the Consistency Index (CI) by the Random Index (RI). A consistency ratio of 0.1 or lower is considered acceptable, a ratio between 0.1 and 0.2 may be acknowledged, while a ratio exceeding 0.2 indicates inadequate consistency [

24]. Finally, to derive the overall importance ranking of the items, the weights obtained from each hierarchy are aggregated.

In the process of calculating the weights of indicators, a hierarchical approach was employed to prevent evaluator confusion [

23]. Within each layer, no more than 10 evaluation criteria were established, and a bidirectional scale from 1 to 9 with 17 points in total was applied for evaluation [

23]. In the use of AHP, when the number of indicators in the upper hierarchy differs, a group with a larger number of indicators tends to receive relatively lower weights compared to a group with fewer indicators [

22]. To address this issue, we applied a modified weighting model to the results of the weights derived from expert surveys in our study, as suggested by previous research that proposed a method for standardizing weights [

25].

HN

i: The number of indicators belonging to plan component i

HWi: The weight of plan component i

LWij: The weight of indicator j belonging to plan component i

HNi: The number of indicators belonging to plan component i

Due to the varying number of indicators within each hierarchy, the study applied model 1 and model 2 to provide relative weights for each indicator.

4. Results

4.1. Relative Importance of the Indicators

After AHP analysis, we found the relative weight of the 27 indicators under the 6 plan components (

Table 3). Among the 6 plan components, energy management strategies received the highest weight followed by factual basis, goals and objectives, implementation and monitoring, governance, spatial and transportation plans. This means that experts consider energy management as the most important component in comprehensive urban plan for achieving carbon neutrality. Establishment of a factual basis, and setting goals and objectives are considered also important because they involve collecting information about the city’s current energy consumption and carbon emissions status, and thus formulating realizable objectives for achieving carbon neutrality.

Among the 27 indicators, the top three highly weighted ones are: 1) plan for industrial technology and production system for carbon reduction, 2) carbon emission reduction target, and 3) facilitation of local renewable sources. Mixed-use development, however, received the lowest score, followed by population change and impact, citizen participation initiatives, and coordination with other institutions. These to be influenced by the significant role of the industrial sector in carbon emissions, with various countries prioritizing the development of policies that foster environmentally friendly innovations, such as improvements in industrial technology and production systems. As a result, experts have demonstrated increased interest in strategic planning for the industrial sector to effectively address carbon neutrality.

4.2. Assessment of Carbon Neutrality of the Plans

In this study, the comprehensive urban plans of each city were assessed based on a 0-2 point scale across 27 indicators. After evaluating each indicator, the assessed values were weighted, leading to the following results. From the assessment of carbon neutrality of 12 comprehensive urban plans, it was found that Uijeongbu city (1.672) scored the highest, followed by Osan city (1.605), Yangju city (1.591), Icheon city (1.547), Yongin city (1.515), Gwangmyeong city (1.507), Seongnam city (1.484), Uiwang city (1.413), Anyang city (1.388), Hwaseong city (1.324), Guri city (1.300), and Paju city (1.236). The top three cities – Uijeongbu city, Osan city, and Yangju city received the highest scores commonly in the 3 indicators: 1) carbon emission reduction target, 2) improvement of industrial technology and production system for carbon reduction, and 3) recognition of greenhouse gas emission. All three cities established multi-step carbon reduction goals with specific ratios or figures for each step. For the indicator, improvement of industrial technology and production systems for carbon reduction, Osan city provided specific strategies for transition to a low-carbon industrial structure, and Yangju city established detailed plans to transform seven old industrial complexes to eco-industrial ones through collaboration with business sectors, landowners, residents, and research institutes. The three cities have also the highest scores in the indicator, recognition of greenhouse gas emission, because they provided detailed descriptions regarding emission sources, quantities of pollutants emitted by the sources, and current air pollution conditions. The three cities, however, have relatively lower scores in the indicators: 1) continuous monitoring, evaluation, and update, 2) mixed-use development, and 3) coordination with other institutions, with either the lack of detailed plans or superficial statements.

Among the 12 cities evaluated, the three cities with the lowest scores in carbon neutrality of the plans are Hwaseong city, Guri city, and Paju city. Although they have scored high in the indicators "Recognition of greenhouse gas emission", "Green transportation system plan" and "Protection and restoration of urban and forest ecosystems," they scored lowest in the indicators, "Seeking energy conservation and energy efficiency", "Supporting climate change vulnerable group" and "Coordination with other institutions". These cities neither present sufficient data nor provide detailed descriptions for the indicators.

Considering the results evaluated for each indicator (

Table 4), the indicator with the highest score across the twelve cities is "recognition of greenhouse gas emission". This indicator ranked fourth in terms of weight among the twenty-seven indicators and received the highest score. All the twelve cities provided comprehensive data. This is partly due to the governmental guidelines for comprehensive urban plans that emphasize data collection for greenhouse gas emissions and absorption. Based on the guidelines, most cities provided the data on greenhouse gas emission across various sectors. The indicator with the second-highest score is "city carbon emission reduction target". In accordance with the guidelines, most cities present carbon reduction goals in five-year intervals up to the plan’s target year, based on the most recent data available. The next indicator that got a high score is the “green transportation system plan" which received 2 points across all cities. This aspect was not only aligned with the urban and municipal basic plan guidelines but also integrated with other relevant plans, resulting in comprehensive and detailed plans for promoting public transportation and eco-friendly transport modes.

On the other hand, the indicator "coordination with other institutions" received the lowest scores. The emissions caused by cross-boundary urban activities contributed much more (47%) than in-boundary greenhouse gas emissions [

26], which means that not a single city can control the emission itself. Despite the necessity for collaboration with neighboring municipalities or other organizations due to the cross-boundary nature of carbon emissions, most cities did not provide plans for collaboration in this regard. The indicator "mixed-use development" focusing on multi-purpose land use, received low scores as well. The compact city concept has been recognized as an effective approach to sustainable development. It achieves this by reducing the amount of travel, shortening commute times, decreasing car dependency, lowering per capita energy use, limiting the consumption of building and infrastructure materials, and minimizing the loss of green and natural areas [

26], which contributes to the reduction of carbon emissions and an increase in carbon absorption. While it is crucial for planning compact cities, many cities provided superficial plans for executing multi-nuclear urban spatial structures. The indicator “supporting climate change vulnerable group" also received low scores, because most cities do not have specific plans, and even when plans are presented, they are mostly declarative. This indicates the lack of consideration for vulnerable groups in climate change adaptation and highlights the need for stronger support and plans for these communities.

Regarding the indicators “supporting climate change vulnerable groups” and “coordination with other institutions”, in most cases, twelve cities either presented abstract strategies or did not provide strategies at all for the related content. The indicator ’Seeking energy conservation and energy efficiency’ saw half of the cities not presenting relevant plans. However, to achieve the carbon neutrality goal, it is crucial to establish specific targets related to the conservation and efficiency of energy use, as energy usage is a primary driver of carbon emissions. By setting specific numerical targets, cities can formulate detailed sector-specific plans to achieve their goals.

5. Results

5.1. Strength of twelve cities comprehensive urban plan

All twelve comprehensive urban plans were found to be well-prepared with regard to the factual basis, including not only the current status of greenhouse gas emissions but also information on population changes, land development, and areas of influence. Based on this data, future greenhouse gas reduction targets were proposed, with most plans setting sector-specific reduction targets relative to the planned population. This thorough preparation is attributed to the detailed guidelines provided in the "Guidelines for the Establishment of Comprehensive Urban Plans" and the "Guidelines for Urban and County Planning for the Creation of Low-Carbon Green Cities," which explicitly specify the basic survey items required for understanding greenhouse gas emissions. However, while the guidelines stipulate that both emission and absorption amounts should be collected by sector during the basic survey, the investigation of absorption rates was not conducted, indicating a need for improvement. In terms of developing public transportation and eco-friendly transportation modes, specific plans were presented, including the expansion of bicycle lanes and the development of subway lines, accompanied by detailed information on planned routes and locations. This is seen as a faithful adherence to the basic principles of transportation planning outlined in the guidelines for the establishment of comprehensive urban plans, which emphasize the expansion of eco-friendly green transportation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption.

5.2. Weakness of twelve cities comprehensive urban plan

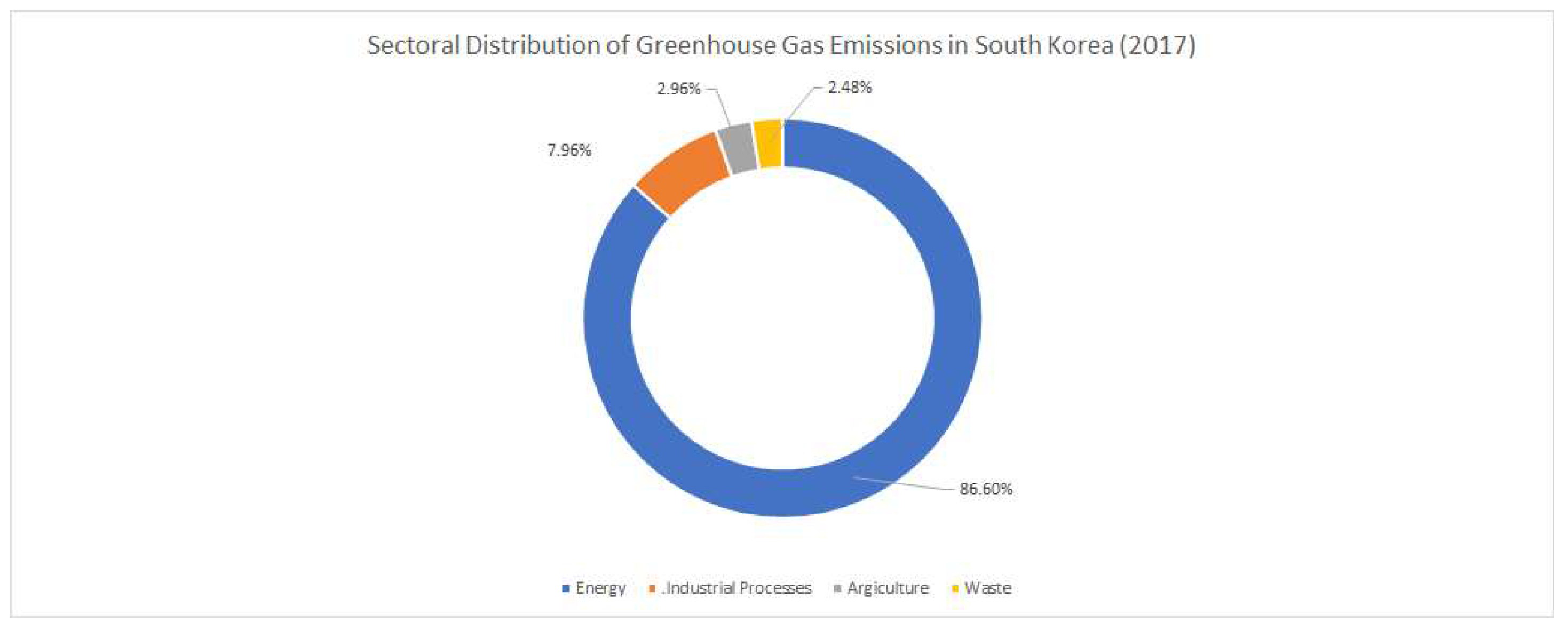

The comprehensive urban plans for the twelve cities were generally found to be most vulnerable in the following areas. First, while there was a strong focus on greenhouse gas reduction, the importance of setting goals for energy conservation and energy efficiency, which are crucial for effective greenhouse gas reduction, was overlooked. Given that a significant portion of greenhouse gas emissions in South Korea comes from the energy sector (

Figure 2), practical efforts in this sector are essential. However, most plans either lack specific targets or have inadequately addressed this sector. Second, there was a lack of continuous monitoring and evaluation mechanisms and plans for updating in most of the comprehensive urban plans. While the formulation of plans is important, it is equally crucial to assess their implementation and provide ongoing feedback. This aspect of planning was found to be insufficiently addressed. Lastly, while some plans include strategies for supporting vulnerable groups and implementing environmental justice, six cities did not present any such plans. This omission may be attributed to the fact that the guidelines for the establishment of comprehensive urban plans address vulnerability to climate change primarily from an infrastructure perspective. Vulnerable groups affected by climate change include not only residents of flood-prone areas and those living in deteriorating housing but also biologically vulnerable groups such as the elderly, infants, children, and disabled individuals, as well as socioeconomically vulnerable groups such as basic livelihood recipients, outdoor workers, and elderly individuals living alone [

28]. Therefore, it is necessary to establish plans that encompass a broader range of vulnerable populations.

5.3. Suggestions for Improving Comprehensive Urban Plans to Achieve Carbon Neutrality

To achieve carbon neutrality for each local government, the following improvements are necessary in the development of comprehensive urban plans: Firstly, the "guidelines for the establishment of comprehensive urban plans" need to be more concretely detailed. These guidelines primarily serve as a guide, emphasizing direction rather than specific details. However, since local governments base their comprehensive urban plans on these guidelines, it is essential to provide more precise specifications to ensure effective achievement of carbon neutrality. For example, while the guidelines accurately specify the sectors and units for greenhouse gas status assessment and reduction target setting, other aspects such as support for vulnerable groups to climate change or goals for energy conservation and efficiency are either absent or remain at a theoretical level. Therefore, for local governments to develop comprehensive urban plans that effectively achieve carbon neutrality, it is necessary to provide more detailed guidance across a wider range of areas.

Furthermore, specific carbon reduction pathways should be presented. Although goals for greenhouse gas reduction have been established, detailed pathways for achieving these goals and plans for carbon sinks have not been provided. Current references to such pathways are abstract, such as "providing green spaces as carbon sinks" and "establishing green networks." Despite being a foundational plan for the city’s development over the next two decades, while details such as road lengths and locations for public transportation and infrastructure expansion are specifically outlined, greenhouse gas reduction and absorption are addressed only in abstract and theoretical terms. This lack of specificity may hinder the development of concrete projects during the urban planning stage. The guidelines for the establishment of comprehensive urban plans recommend the autonomous development and use of maps detailing greenhouse gas emissions and absorption, building energy demand, wind corridors, fuel use related to transportation, microclimate, and distribution of carbon sinks, to enhance the city’s resilience to climate change [

29]. In line with this recommendation, it is suggested that local governments establish and utilize such data to develop specific carbon reduction pathways that reflect local characteristics.

6. Conclusions

The study aimed to assess the carbon neutrality of comprehensive urban plans that play a pivotal role in envisioning the future of local governments. The study derived assessment indicators from an extensive review of literature and an expert survey to determine the relative weights of the indicators, using AHP and Weight Modified Model. Plan qualities in terms of carbon neutrality were assessed for 12 cities in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. The conclusions of the study are as follows:

• The cities that scored highest in carbon neutrality of the plans have clear and detailed goals of carbon reduction and energy conservation, while the cities with lowest scores have unclear goals and strategies for carbon reduction and for supporting vulnerable groups to climate change. Uijeongbu city, Osan city, and Yangju city, the top three cities with the highest scores in carbon neutrality of the plans, established clear goals of carbon reduction and energy conservation based on detailed inventories of carbon emission and energy consumption patterns, and presented specific implementation strategies. On the other hand, Hwaseong city, Guri city, and Paju city, the cities with the lowest scores, have unclear goals in energy conservation and efficiency goals, and have no specific goals and strategies for supporting vulnerable groups to climate change.

• The cities presented relevant content specifically in inventories of local carbon emissions and causes, carbon reduction target setting, and development goals focusing on public transportation and eco-friendly modes which are based on the guideline for the establishment of comprehensive urban plan. However, we observed a lack of collaboration for carbon neutrality between the local cities and regional and national governments. Since carbon emission is not limited to geographic boundaries, collaboration with neighboring cities and regional governments is essential.

• South Korea’s comprehensive urban plan guideline provides a regulatory framework for carbon reduction strategies within the urban development process by incorporating carbon neutrality-related content in planning components. Additionally, it emphasizes carbon reduction strategies to include regulations and recommendations for the industrial sector. However, there are certain weaknesses in the plans. They lack sufficient details regarding interagency and interregional cooperation for the formulation and execution of carbon reduction strategies. Furthermore, specific strategies for supporting and monitoring vulnerable populations to climate change are also lacking.

• To enhance the effectiveness of carbon reduction strategies and support vulnerable populations affected by climate change, it is essential to establish formal agreements between neighboring cities to coordinate initiatives and share resources effectively. Implementing a multi-level governance framework that includes representatives from local, regional, and national levels can facilitate aligned priorities and the sharing of best practices. Additionally, a comprehensive carbon management system is critical for monitoring emissions and tracking progress, supported by a shared database that consolidates relevant data. Specific policies and programs must be developed to empower vulnerable communities, including targeted disaster preparedness education and housing improvement initiatives focusing on energy-efficient upgrades in climate-vulnerable areas. Furthermore, strengthening social safety nets through employment support and retraining opportunities will help mitigate the socioeconomic impacts of climate change. Promoting joint projects, such as community awareness campaigns and green infrastructure initiatives, can foster community engagement and collective action towards carbon neutrality. Finally, providing financial incentives, such as grants or subsidies for carbon-neutral projects, will encourage local governments to actively pursue these initiatives and promote environmental justice, thereby enhancing the resilience of vulnerable communities in the face of climate change. To enable the establishment of these institutional mechanisms, it is crucial to clearly outline these directions within the guidelines for formulating comprehensive urban plans.

This study distinguishes itself by deriving comprehensive indicators through a literature review of previous research on urban planning elements and evaluation indicators for carbon neutrality and carbon reduction. Additionally, it differentiates itself by determining the relative weight of indicators through expert surveys and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) analysis. This study provides valuable insights for formulating strategies to achieve carbon neutrality in establishing comprehensive urban plans. However, in order to better capture a variety of direct and indirect impacts on carbon neutrality, a more sophisticated set of indicators that reflect local context and assessment measures need to be developed. The study suggests that further research is necessary for expanding the range of indicators to assess carbon neutrality and enhanced methods to minimize subjectivity in the assessment process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. and G.L.; methodology, G.L.; software, G.L.; validation, J.K. and G.L.; formal analysis, G.L.; investigation, G.L.; resources, J.K. and G.L.; data curation, G.L.; writ-ing—original draft preparation, G.L.; writing—review and editing, J.K. and G.L.; visualization, G.L.; supervision, J.K.; project administration, J.K.; funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea, grant number ‘NRF-2019S1A5A2A03049104’.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2013.

- Chen, J.M. Carbon neutrality: Toward a sustainable future. The Innov. 2021, 2, 100127. [CrossRef]

- Daily CO2. Available online: https://www.co2.earth/daily-co2 (accessed on 2 Sep 2023).

- Rabaey, K.; Ragauskas, AJ. Editorial overview: energy biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.2014, 27, 5–6. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Msigwa, G.; Yang, M.; Osman, A. I.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D. W. Strategies to achieve a carbon neutral society: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2277–2310. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 ºC. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- UNFCCC. Climate Neutral Now Guidelines for Participation. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/CNN%20Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Greenhouse Gas Inventory & Research Center of Korea. 2023 National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Summary (1990-2021), 2023.

- Korea Meterological Administration. Korean Climate Change Assessment Report 2020; Korea Meterological Administration: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2020.

- Koh, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.; Kang, S.; Hwang, J.; Im, J.; Jung, S.; Jang, H.; Ye, M.; Hwang, J. Net Zero Carbon Strategy and Policy Challenges of Gyeonggi-Do. Gyeonggi Research Institute, 2021, 67.

- World Bank, World Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan 2021–2025: Supporting Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development; The World Bank: Washington, D.C., United States, 2021.

- Cutting global carbon emissions: where do cities stand? Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/sustainablecities/cutting-global-carbon-emissions-where-do-cities-stand (accessed on 3 Sep 2023).

- Betsill, M.; Harriet, B., Cities and climate change, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, United Kingdom, 2003.

- Oh, D.; Sung, J.; Lee, S., The application and development of the Evaluation Indicators in accordance with the Planning Stages of Low-Carbon City: in relevance with the stage of urban planning establishment, Design operation of urban structure, management and maintenance 2013, 14, 4560-4571. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J., A Study on the Planning Indicator for Carbon Neutral Green City. J. Korea Institute of Ecological Architecture and Environment 2013. 13, 131-139. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Jung, J.; Kwon, T, Assessment of Low-Carbon City Planning Elements Relative to Urban Types. Journal of environmental policy and administration 2010, 18, 27-52.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and transport, Ordinance No. 1470: Urban Basic Plan Establishment Guideline, 2023.

- The Government of the Republic of Korea, The Republic of Korea’s 2050 Carbon Neutrality Strategy for Achieving a Sustainable Green Society; The Government of the Republic of Korea, Republic of Korea, 2020.

- Seth, S.; Srivastava, R.; Harper, S.; Osho, Z., From Planning to Action: Rethinking the Role of Cities in Accelerating Net-Zero Transitions. T20 Policy Brief, India, 2023.

- Ting, W.; Zhenghong, T., Building low carbon cities: Assessing the fast-growing U.S. cities’ land use comprehensive plans, J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2014, 16, 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Gyeonggi Data Base. Available online: https://data.gg.go.kr/portal/data/service/selectServicePage.do?infId=OYUMJUDK201TN8I8CM9Y31515663&infSeq=1 (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Achieving Local Carbon Neutrality: Moving Beyond Goals to Implementation, Available online: https://www.ecotiger.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=32951(23 November 2023).

- Wind, Y.; T. L. Saaty., Marketing applications of the analytic hierarchy process. J. Manag. Sci. 1980, 26, 641-658. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Choi, Y.; Con, J., Analysis of Importance in Available Space for Creating Urban Forests to Reduce Particulate Matter: Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 47(6):103-114. [CrossRef]

- Choi M., Evaluation of Analytic Hierarchy Process Method and Development of a Weight Modified Model. Manag. Inf. Syst. Review 2020, 39, 145-162. [CrossRef]

- Hillman, T.; Ramaswami, A., Green house gas emission footprints and energy use benchmarks for eight U.S.cities Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1902–1910. [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J.; Kärrholm, M., Compact city planning and development: Emerging practices and strategies for achieving the goals of sustainability. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 4, 100021. [CrossRef]

- Lee D., Improvement Measures for Protecting Vulnerable Groups Against the Climate Crisis. National Assembly Research Service NARS Current Issues and Analysis. 2022, No. 278.

- Ministry of Land, Section 2: Basic Principles of Plan Establishment, Ordinance No. 1470: Urban Basic Plan Establishment Guideline, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).